Abstract

Motivation: Similarities in core residue packing provide evidence for divergence or convergence not reported using other methods.

Results: We apply a new method for rapid structure comparison based on Simplicial Neighborhood Analysis of Protein Packing (SNAPP) to the diverse structural classification of proteins (SCOP) α/β-class of protein folds. The procedure identifies inter-residue packing motifs shared by protein pairs from different folds. A threshold of 0.67 Å RMSD for all atoms of corresponding residues ensures inclusion of only highly significant similarities comparable with those observed for identical catalytic residues in homologues. Many tertiary packing motifs are shared among the three classical Rossmannoid folds, as well as thousands of other motifs that occur in at least two distinct folds. Merging of neighboring packing motifs facilitated recognition of larger, recurrent substructures or cores. The anti-codon-binding domain of an archeal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS) was discovered to possess a packed core in which eight identical amino acid residues are within 0.55 Å RMSD of the comparable structure in the FixJ receiver, a member of the Rossmannoid family that also includes the CheY signaling protein and flavodoxin-like proteins. Further investigation identified close variants of this core in five other Rossmannoid folds, including a functionally relevant core in Class Ia aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Although it is possible that the two essentially identical cores in the ProRS anti-codon-binding domain and the FixJ receiver converged to the same structure, the consensus core obtained from the structural and sequence alignments suggests that all the implicated protein folds descended from a simpler ancestral protein in which this core provided nucleotide binding and proto-allosteric functions.

Availability: Programs are available at http://staff.vbi.vt.edu/cammer/snapp/download/

Implementation: Programs were written in Perl and c and run under Linux.

Contact: cammer@vbi.vt.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

Demonstrating structural similarities between proteins has long provided the initial evidence for common structural motifs representing evolutionary divergence or convergence. Most approaches rely on comparing the arrangement of secondary structures or other local substructures in 3D (Dror et al., 2003; Holm and Sander, 1993; Madej et al., 1995; Orengo and Taylor, 1990; Shindyalov and Bourne, 1998). Considerably less development has been devoted to identifying more precise structural details.

Comparison methods that focus on precise arrangements of amino acid residues are usually used to identify catalytic, ion binding and small molecule binding sites (Barker and Thornton, 2003; Fetrow and Skolnik, 1998; Fischer et al., 1994; Jambon et al., 2003). Often, the aim is to recognize similarities across distinct protein folds for function prediction or active-site comparisons among homologous protein structures (Fetrow et al., 1999). Such atomic level comparisons have generally not been extended to features outside active sites. Yet, as distantly related proteins with different folds usually have substantial active-site differences, comparing structural features outside the active sites may yield more definitive evidence for divergence from a common ancestor for proteins with specific sub-structural motifs. Central to the present work is identification of tertiary contact motifs found in pairs of proteins from at least two different folds.

The method identifies recurrent tertiary contacts between protein secondary structure elements. Similarities are observed at the atomic level of detail where conformations of individual amino acid residues are repeated in similarly packed arrangements of side chains on the secondary structure faces. In conventional analyses, the most regularly repeated features of tertiary contacts observed are residue pairs separated as (i, i + 2) in β-strands, and as (i, i + 3) and (i, i + 4) on the surface of α-helices (Chothia and Janin, 1982; Chothia et al., 1977, 1981; Janin and Chothia, 1980). In this work, these residue pairs will be referred to as secondary structure-coupled residues (SCRs). SCRs yield ‘knobs-and-holes’ (Crick, 1953) that form the close-packed interfaces between secondary structure elements. The regular spacing in sequence and in 3D of SCRs leads to preferred orientations for the secondary structures in 3D that have been observed in similar protein structures. Results presented here demonstrate that tertiary, i.e. non-sequence local arrangements of residues interacting at the interfaces of secondary structure elements yield evolutionary clues that cannot be obtained by comparing one-dimensional motifs.

We analyze the structural classification of protein (SCOP) α/β-class of proteins, in which β−α−β motifs are repeated to form layered sandwich structures with helices on both sides of a central, parallel β-sheet. The largest related superfamily of proteins in this class is the Rossmannoids, which comprises 12 different folds presumed to be present in the last common ancestor (LCA) of all organisms (Aravind et al., 2002; Shakhnovich et al., 2003). Many motifs have been identified here that connect the three classical Rossmannoid folds, as well as the others, and many more motifs have been discovered that are shared by at least two different folds in the α/β-class.

A large, interesting and widely shared motif is a core of eight residues linking an α-helix to three parallel β-strands in flavodoxin-like (Rossmannoid) fold members, FixJ and CheY, and in the anti-codon-binding domain of Class II prolyl- and glycyl-tRNA synthetases and the accessory β-subunit of mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ. These two fold families have not been previously identified as possessing such detailed similarity. Interestingly, this core is partially represented in five other Rossmannoid folds, including Class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, where it appears also to serve an allosteric function (Kapustina et al., 2007; Weinreb et al., 2009). The prevalence of this motif in proteins that bind to nucleotides, and the presumptive functional importance in Class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, suggest that a single ancestral protein may have diverged to form the Rossmannoids and the anti-codon-binding domain. As the Rossmannoids diverged before the LCA of all organisms, the detected core similarity would represent one of the most ancient protein structural modules yet identified.

2 METHODS

2.1 Database

Five classes from the SCOP 1.73 database guided assembly of a near-exhaustive collection of representative protein structures from the Protein Data Bank (Murzin et al., 1995). One protein structure was selected for each species represented and for every domain in the SCOP α, β, α/β, α + β and multi-domain proteins classes. In all, 11 610 fold representatives were compiled from 9197 structures in SCOP.

2.2 Structure representation and packing decomposition

All structures were represented by a single-point per residue based on side-chain centroids. Tetrahedral packing simplices were identified using SNAPP (Cammer et al., 2002; Tropsha et al., 2003), which uses Delaunay tessellation to decompose the set of side-chain centroids into non-overlapping tetrahedra where four residues form nearest neighbors.

Each four-body contact was represented by combining the single-letter codes in sequence order with the three distances of sequence separation of the residues along the chain. Distances used were 2, 3 and 4 for SCRs, and L for distances greater than four residues of separation. For example, IILV_2_L_L refers to a Delaunay simplex composed of residues 151I, 153I, 165L and 176V. A four-body pattern that includes at least one SCR is referred to here as Secondary structure-Coupled Residues And Packing Environment (SCRAPE). SCRAPEs constitute elemental links between secondary structures and are therefore elementary tertiary packing motifs. SCRAPEs common to at least two different folds were screened to identify packing arrangements within 0.67 Å RMSD for all atoms. This degree of similarity is comparable with similarities in ser–asp–his catalytic triads among homologous trypsin-like serine proteases (Stark et al., 2003).

2.3 Motif finding

SCRAPEs repeated in protein structures from two different folds initially were compared geometrically using tetrahedra defined by connecting side-chain centroids. Motifs were identified and analyzed using the following workflow:

SCRAPEs, i.e. residue side chain centroid tetrahedra, are identified in all protein structures in the database using SNAPP based on Delaunay tetrahedralization.

Tetrahedra with identical residue types and sequence spacing found in pairs of structures from different folds are superimposed and compared.

When all-atom RMSD for the four residues in a tetrahedron is <0.67 Å, the tetrahedron is considered to be a motif shared by both structures.

When neighboring motifs are identified in the same structure pair, these motifs are combined to form a composite motif linking the two structures.

All motifs linking structures in different fold pairs are tabulated and used for generating similarity networks that graph motif distribution of among different folds in the database.

Network edges were drawn based on various cut-offs for number of residues shared. Many of these structure similarity networks were generated and visualized for subsets of the data. Superimpositions of hundreds of structure pairs were visualized directly.

3 RESULTS

Protein structures from the SCOP α/β-class were analyzed for SCRAPEs in recurring packing motifs that might help discriminate between evolutionary divergence and convergence. There were 32 180 instances of protein structure pairs from different folds possessing SCRAPE pairs that were within 0.67 Å RMSD for all atoms. SCRAPES were combined to form composite motifs, revealing a total of 18 107 similarities between protein pairs from distinct folds in the α/β-class.

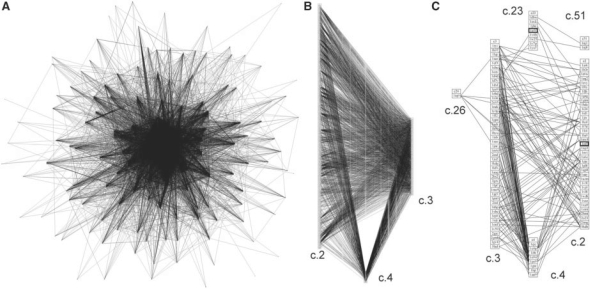

The overall motif distribution can be visualized by drawing a graph where edges represent the highly significant structural similarities shared by two protein structures. Figure 1A illustrates the protein structure similarity network obtained for the SCOP α/β-class. The network reveals many precise similarities between proteins from different folds, suggesting many evolutionary connections between members of the α/β-class.

Fig. 1.

Protein structure similarity networks for α/β proteins, classical Rossmannoids and a subset of motifs. (A) Edges were drawn by connecting representatives of each fold when the two motif structures were within 0.67 Å RMSD of each other. Each edge represents a similarity of at least four residues. (B) The structure similarity network is shown for the three classical Rossmannoid fold subsets; a fold is a column of PDB representatives in boxes: c.2, NAD(P)-binding Rossmann-fold domains; c.3, the FAD/NAD(P)-binding domain; and c.4, the nucleotide-binding domain. These classical Rossmannoids are the most densely connected fold clique of the similarity network in (A). (C) The structure similarity network is shown for the cases when at least seven residues are shared between the two proteins. The classical Rossmannoids are well-connected, and the remaining connections are to two different Rossmannoid folds (c.23 and c.26), as well as the connection between the anti-codon-binding domain of a Class II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (c.51) and c.23, the flavodoxin-like fold (FixJ structure). c.26 is the adenine nucleotide α-hydrolase-like fold, which includes the Class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase catalytic core; the representative in the c.26 box (1iq0) is the Class I argininyl-tRNA synthetase. All structures in 1C except the two highlighted by bold boxes possess at least partial representation of the core identified in the Rossmannoids and described further in this work.

The most prominent feature of the α/β similarity network is a sub-structure formed from edges connecting the three classical Rossmannoid folds defined in SCOP: Class 2—NAD(P)-binding Rossmann; Class 3—FAD/NAD(P)-binding domains; Class 4—nucleotide-binding domains (Fig. 1B). Figure 1B shows 1841 connections between c.2 and c.3, 266 connections between c.2 and c.4 and 285 connections between c.3 and c.4. Each edge represents similarity of at least four residues between fold representatives.

The most significant similarities can be observed in graphs that impose a minimum threshold of similar residues. Figure 1C shows a graph representing the α/β-class connections when at least seven residues are structurally similar. This network reveals that the c.23 flavodoxin-like fold (a Rossmannoid) and the c.26 adenine nucleotide hydrolase-like fold [a Rossmannoid that includes the Class I archeal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS) catalytic core] are connected to the classical Rossmannoids.

The network also shows that the c.51 anti-codon-binding domain of Class II aaRS shares a common motif of eight residues with the FixJ receiver (c.23). This network illustrates how the method of comparison used here can reveal relationships among proteins that have diverged to the point of having distinct folds, as well as possibly identifying cases of convergence to a common motif.

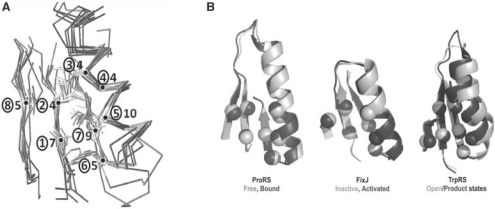

Further analyses identified five additional Rossmannoid folds that possess partial representation of this core. Superimposed representatives are shown in Figure 2, and statistics for core residues for each representative are collected in Table 1, together with crystal structure resolutions and RMSDs. Despite the stringent cut-off, only two structures in Figure 1C failed to exhibit this motif.

Fig. 2.

Structurally similar cores in the ProRS anti-codon-binding domain, the FixJ receiver and other Rossmannoid representatives. (A) Cores from Figure 1C and Table 1 are shown as superimposed Cα traces and stick figures for residue side chains. The sequential β−α−β motif is formed from the central and rightmost strands and the α-helix. The number of consensus amino acids is given for each residue position (circled). (B) Functionally relevant allosteric changes in ProRS, FixJ and TrpRS core motifs. These three motifs exhibit conformational changes in response to ligand binding [ProRS anti-codon-binding domain, 1H4S, 1H4T; TrpRS catalytic domain, 1MAW(F), 1I6L] or phosphorylation [FixJ, 1D5W(A), 1DBW(A)]. Activated conformations are darker. The eight positions indicated in Table 1 are indicated by Cα positions that rearrange similarly in the three proteins. These changes have been implicated experimentally in long-range communication with the active site catalytic Mg2+ ion in TrpRS (Kapustina et al., 2007; Weinreb et al., 2009).

Table 1.

Residues comprising cores shown in Figure 2

| SCOP fold | NCBI/pfam Domains | PDB | C〈 |

Core Pos 1 |

2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD | MSA | ||||||||||

| c51—ClassII aaRS anti-codon-binding domain | ProRS | 1nj1A | V297 | I299 | L318 | R319 | L322 | F327 | V329 | V354 | |

| cd00862: | 2.55Å | ||||||||||

| 1h4sB | |||||||||||

| 2.85Å | 17/22V | 14/22I | 6/22L | 6/22A | 19/22L | 3/22F 9I 3I 6V | 14/22V | 5/22V 6L 8I | |||

| c51—mitochondrial polymerase gamma (β) | 1g5hA | 0.4Å | V357 | L359 | L376 | L377 | L380 | I385 | V387 | V415 | |

| 1.95Å | 5/8V | 4/8L 2I | 7/8L | 1/8L | 8/8L | 4/8L | 6/8V | 4/8V | |||

| c23—flavodoxin-like | 1d5wA | 0.26Å | V6 | I8 | L19 | A20 | L23 | F28 | V30 | V52 | |

| FixJ Receiver | 2.3Å | ||||||||||

| cd00156: | 1dbwA | ||||||||||

| 1.68Å | 97/307I 95V | 144/307L | 41/307A | 237/307L | 58/307F 79Y | 184/307V | 54/307V 80I 120L | ||||

| c2—NAD(P)-binding Rossmann-fold domains | PRK06179: PRK06179 | 1jtvA | 0.44Å | V5 | I7 | L18 | A19 | L22 | F30 | V32 | V88 |

| 1.54Å | 12/24V 12A | 9/24I 15V | 1/24L | 24/24A | 14/24L 10F | 8/24 F 7Y | 24/24V | 24/24V | |||

| c3—FAD/NAD(P)-binding domain | pfam07992: | 1m6i | 0.84Å | I303 | I305 | L315 | A316 | L319 | A323 | V330 | V395 |

| Pyr_redox_2 | 1.80Å | 46/146 V 28I 24L | 53/146I 84V | 28/146L 22F 20V | 109/146A | 62/146L 32F 28A | Gapped | 117/146V | 31/146V 46L 26I | ||

| c66—SAM-dependent methyltransferases | pfam08241: Methyltransf_11 | 1r74A | 0.43Å | V60 | D62 | D70 | S71 | L74 | F79 | V81 | I136 |

| 2.55Å | 113/177D | 26/177L | 30/177A | 85/177L | 4/177F Gapped | 81/177V | 24/177V 22I 29L | ||||

| c26—adenine nucleotide α-hydrolase-like | PRK00509: PRK00509 | 1vl2A | 0.65Å | V5 | L7 | I18 | L19 | L22 | F27 | V29 | A113 |

| 2.10Å | 134/143V | 138/143L | 83/143I 43A | 51/143L 88I | 119/143L | 1/143F 18Y Gapped | 125/143V | 95/143A | |||

| c4—nucleotide-binding domain | pfam00070: Pyr_redox | 1o94A | 0.46Å | V392 | I394 | A404 | A405 | L408 | Y413 | V415 | I484 |

| 2.0Å | 37/131V | 46/131I | 25/131L 21F 7A | 102/131A | 55/131L 33F | 4/131Y 13L Gapped | 111/131V | 25/131I 46L 22V | |||

| c26—arginyl-tRNA synthetase | Class Ia aaRS | 1iq0A | 0.42Å | V105 | V107 | I132 | A133 | L136 | R141 | V143 | I350 |

| Pfam00750 | 2.3Å | 20/43V | 16/43V, 16I | 28/43I | 23/43A | 25/43L | 19/43Y 4F | 37/43V | 31/43I | ||

| c26—Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase | Class Ic aaRS | 1i6l | 1.83Å | I4 | F37 | (Missing) | F26 | L29 | Y33 | C35 | I140 |

| Pfam00579 | 1.72Å | (0.91Å) | (Out of order) | ||||||||

| 1mawF | |||||||||||

| 3.0Å | 19/99I 50V | 42/99F | 16/99F 47W | 46/99L | 45/99Y | 47/99C 11V | 16/99I 35L | ||||

| Structure Consensus | V | I | L | A | L | F | V | V | |||

| MSA's | V/I | I/V | I/L | A | L | F/Y | V | I/L/V |

Core residues are listed with MSA results for each domain. Structure resolutions (Å) and Cα RMSDs (Å) for core residues compared with the ProRS anti-codon-binding domain also are shown. In boldface are consensus homologs from the Class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase family. ArgRS is identified in Figure 1C. TrpRS has a larger RMSD, as its C-terminal β-strand is displaced to form the tryptophan-binding site. The double line separates the variant TrpRS core from those identified in Figure 1C.

Pre-computed multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) were obtained from the conserved domain representatives at NCBI using the structure sequences as queries to determine the consensus core positions. Consensus sequences are shown in Table 1. Most positions followed the structures in Figure 1C closely, although some positions were represented by nearly equal numbers of similar amino acid types in the MSAs.

4 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

(i) Four-body simplices afford a valuable extension of graph--theoretic applications from active site configurations to a far broader class of evolutionary problems: SNAPP detects precisely repeated structural details in many proteins from a nearly exhaustive representation of protein structures in the SCOP α/β class. The similarities indicate either evolutionary divergence or convergence. Although convergence cannot be ruled out, the N-terminal location and the coincidence of primary, secondary and tertiary structural similarities (Table 1; Fig. 2A) highlighted here—between classical Rossmannoids in the protein structure similarity network—are most naturally interpreted in terms of an early adaptive radiation and hence of divergent evolution. This interpretation is reinforced (Shakhnovich et al., 2003) by the fact that divergence could have been driven by the adaptive radiation of the same primordial functions of the core motif—nucleotide (phosphate) binding and conformational switching (Fig. 2B) shared by descendant Rossmannoid folds.

(ii) Construction of composite packing motifs involving elemental links between secondary structures affords a new metric for ancient protein phylogeny: any core motif identified by our procedure implicitly comprises many bona fide examples of divergent evolution represented in the MSAs belonging to each fold family. Importantly, there is less variation between the motifs in different fold families in Figure 1C than is evident within single fold families (i.e. the ArgRS and TrpRS core motifs in Table 1). Comparison of the core motif in ArgRS and TrpRS illustrates that using a strict threshold for RMSD and residue identity for identification helps assure significance of the motifs identified, especially in the face of considerable variation evident in motif instances within consensus superfamilies.

(iii)One eight-residue motif, in particular, links the N-terminal β–α–β cross-over to a downstream β-strand especially frequently in the Rossmannoid family: common amino acids in all seven topologies are consistently reinforced by the associated MSAs, raising the possibility that at some time before the LCA, a small ancestral protein with this N-terminal β–α–β cross-over connection of 30–40 amino acids, tied to a downstream β-strand, diverged to eventually form all Rossmannoids including the Class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, as well as the anti-codon-binding domain of Class II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases for proline and glycine, and the accessory β-subunit of the mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ (Kaguni, 2004). This example, therefore, shows that examining precisely repeated inter-residue packing arrangements using an SNAPP-based bioinformatics approach can lead to consistent and novel inferences about evolutionarily divergent and/or convergent motifs shared by proteins with similar but distinct folds.

(iv) The motif at the N-terminus of the Rossmann fold has independently emerged as having important nucleotide-binding and proto-allosteric functionality. The widespread occurrence of this motif is especially interesting in light of its consensus association with nucleotide-binding functions and its likely allosteric behavior (Fig. 2B). Anti-codon binding by the ProRS domain leads to structural rearrangement that is likely communicated to the active site (Yaremchuk et al., 2000). Structural changes in the FixJ motif upon phosphorylation of D54 complement the rearrangement of F106 associated with its activation for transcriptional regulation (Birck et al., 1999), and a similar change occurs in the bacterial chemotaxis response regulator, CheY (Schuster et al., 2001). The homologous motif in Class I tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase functions in molecular switching that accompanies both induced fit and catalysis (Kapustina et al., 2007). Mutation (i.e. of F37I) exerts long-range effects on the relative stability of different TrpRS conformational states and reduces the catalytic contribution of the Mg2+ ion (Weinreb et al., 2009).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge discussions with A. Lee (School of Pharmacy, UNC) who coined the descriptive term ‘proto-allosteric’.

Funding: National Institute of General Medical Sciences 78227 (to C.W.C.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Aravind L, et al. Trends in protein evolution inferred from sequence and structure analysis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:392–399. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00334-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JA, Thornton JW. An algorithm for constraint-based structural template matching: application to 3D templastes with statistical analysis. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1644–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birck C, et al. Conformational changes induced by phosphorylation of the FixJ receiver domain. Struct. Fold. Design. 1999;7:1505–1515. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)88341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammer SA, et al. Identification of sequence-specific tertiary packing motifs in protein structures using Delaunay tessellation. In: Schlick T, Gan HH, editors. Lecture Notes in Computational Science and Engineering. Vol. 24. New York: Springer; 2002. pp. 477–494. [Google Scholar]

- Chothia C, Janin J. Orthogonal packing of b-pleated sheets in proteins. Biochemistry. 1982;21:3955–3965. doi: 10.1021/bi00260a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chothia C, et al. Structure of proteins: packing of a-helices and pleated sheets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1977;74:4130–4134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.10.4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chothia C, et al. Helix to helix packing in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1981;145:215–250. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick F.HC. The packing of a-helices: simple coiled-coils. Acta Cryst. 1953;6:689–697. [Google Scholar]

- Dror O, et al. Multiple structural alignment by secondary structures: algorithm and applications. Prot. Sci. 2003;12:2492–2507. doi: 10.1110/ps.03200603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetrow JS, et al. Structure-based functional motif identifies a potential disulfide oxidoreductase active site in the serine/threonine protein phosphatase-I subfamily. FASEB J. 1999;13:1866–1874. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.13.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetrow JS, Skolnik J. Method for prediction of protein function from sequence using the sequence-to-structure-to-function paradigm with application to glutaredoxins/thioredoxins and t1 ribonucleases. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;281:949–968. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer D, et al. Three-dimensional, sequence order-independent structural comparison of a serine protease against the crystallographic database reveals active site similarities: potential implications to evolution and to protein folding. Prot. Sci. 1994;3:769–778. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Sander C. Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;233:123–138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janin J, Chothia C. Packing of alpha-helices onto beta-pleated sheets and the anatomy of alpha/beta proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1980;143:95–128. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jambon M, et al. A new bioinformatic approach to detect common 3D sites in protein structures. Proteins, Structure, Function and Bioinformatics. 2003;52:137–145. doi: 10.1002/prot.10339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaguni LS. DNA polymerase g, the mitochondrial replicase. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 2004;73:293–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapustina M, et al. A conformational transition state accompanies amino acid activation by B. stearothermphilus tryptophanyl-trna synthetase. Structure. 2007;15:1272–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madej T, et al. Threading a database of protein cores. Proteins, Structure, Function and Genetics. 1995;23:536–540. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murzin AG, et al. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;247:536–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orengo CA, Taylor WR. A rapid method for protein structure alignment. J. Theor. Biol. 1990;147:517–551. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster M, et al. Conformational coupling in the chemotaxis response regulator chey. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:6003–6008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101571298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakhnovich BE, et al. Functional fingerprints of folds: evidence for correlated structure-function evolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;326:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01362-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. Protein structure alignment by incremental combinatorial extension of the optimal path. Prot. Eng. 1998;11:739–747. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.9.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark A, et al. A model for the statistical significance of local similarities in structure. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;326:1307–1316. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropsha A, et al. Simplicial Neighborhood Analysis of Protein Packing (SNAPP): a computational geometry approach to studying proteins. Meth. Enz. 2003;374:509–544. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreb V, et al. Mg2+-assisted catalysis by B. stearothermophilus trprs is promoted by allosteric effects. Structure. 2009;17:952–964. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaremchuk A, et al. Crystal structure of a eukaryote/archaeon-like protyl-tRNA synthetase and its complex with tRNApro(cgg) EMBO J. 2000;19:4745–4758. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]