Abstract

The reaction of 2-aminoaryl ketones and arynes generated by the treatment of various o-(trimethylsilyl)aryl triflates with CsF results in [4 + 2] annulation to afford substituted acridines in good yields.

Introduction

The use of arynes as building blocks in the construction of heteroaromatic structures has become increasingly popular in recent years.1 The electrophilic coupling of arynes, in particular, as opposed to transition metal-catalyzed or pericyclic reactions, has produced a number of very useful syntheses of biologically active heteroaromatics, including indoles,2 benzofurans,3 quinoxalines,4 thiazines,3 oxazines,3 benzotriazoles,5 benzoxazines,6 clavilactones,7 indoloquinones,8 carbazoles,9 dibenzofurans,9 dibenzothiophenes,9 and phenanthridines.10

Recently, our group reported the reaction of arynes and ortho-heteroatom-substituted benzoates, which affords medicinally relevant acridones, xanthones, and thioxanthones in good overall yields under very mild reaction conditions (eq. 1).11 The success of this novel methodology led us to examine the corresponding ortho-substituted ketones and aldehydes. Using similar mild conditions, it was initially found that 2-aminoacetophenone and o-(trimethylsilyl)phenyl triflate react to produce 9-methylacridine in a 68% yield (eq. 2).

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

Acridines have demonstrated important biological activity,12 including activity against cancer13 due to their ability to intercalate into DNA and disrupt unwanted cellular processes.14 This unique property of acridines has been exploited in many areas of medicine. As a result, significant biological activity towards viruses,15 bacteria,16 parasites,17 fungus,18 Alzheimer’s disease,19 and HIV/AIDS20 have also been reported. 9-Methylacridines have also been used recently in the construction of new fluorescent probes that emit light at longer wave lengths in order to inhibit unwanted absorption, autofluorescence, and scattering by neighboring biological tissue.21 Acridines complexed with iridium have also been used as triplet state, light emitting materials for applications in OLED’s.22

Most of the current methods to synthesize acridines require rather harsh conditions. For example, intramolecular versions of the original acridine synthesis, the Bernthsen reaction,23 continue to employ high temperatures and strongly acidic media.24 Another commonly used method for preparing acridines involves the reduction of acridones.25 However, until our recent report (eq. 1), the syntheses of acridones have also required high temperatures and strongly acidic conditions to affect intramolecular electrophilic aromatic substitution of N-phenylanthranilic acids.25a,26 Also published recently were the annulations of 2-oxo aryl azides and 2-azidobenzenecarbonitrile by benzene, giving rise to a variety of acridines, including 9-aminoacridine.27

In 2005, Kim28 et. al. reported the synthesis of acridines using 5-arylthianthrenium perchlorates as benzyne precursors to affect [4 + 2] annulations with ortho-aminoaryl ketones, esters, and aldehydes (eq. 3). Although the scope of this methodology appears fairly broad, and the yields are generally good, some drawbacks to this methodology are evident. Not only is there no commercial source for Kim’s benzyne precursor, but its synthesis requires the use of a highly explosive salt, thianthrene cation radical perchlorate.29 In addition, a strongly activated aryl substrate, such as anisole, is needed in order for the requisite electrophilic aromatic substitution to take place efficiently. Depending on the acridine’s ultimate use, one may or may not want the fluorine and methoxy groups present in the final products. Lastly, in order to generate benzyne from a 5-arylthianthrenium perchlorate, a very strong base, like LDA, is needed. These harsh conditions severely limit the types of functional groups, which can be accommodated. Our approach to acridines, however, utilizes Kobayahi’s30 very mild reaction conditions for generating benzynes in situ through fluorine-induced elimination of o-(trimethylsilyl)aryl triflates to affect annulation with commercially available ortho-aminoaryl ketones and aldehydes.

|

(3) |

The reaction of ortho-aminoaryl carbonyl compounds and alkynes containing electron-withdrawing groups is a process analogous to our aryne methodology.31 First reported in the 1960’s, this chemistry affords good yields of the corresponding 2,3,4-trisubstituted quinolines in one step (eq. 4). As with our acridine synthesis, the initially formed secondary alcohol rapidly dehydrates and forms the more stable aromatic system. Because the acridine core is important in so many areas of chemistry and there are currently very few mild, functionally-tolerant methodologies available for the efficient synthesis of acridines, it was our goal to investigate the scope of the process described in equation 2, first through optimization of the reaction conditions and second by examining its scope and limitations.

|

(4)29b |

Results and Discussion

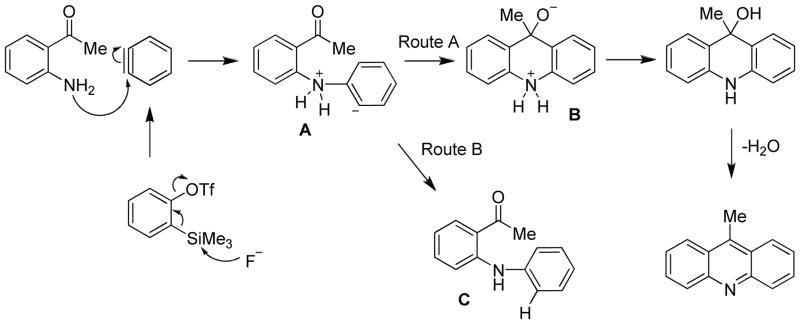

Initial studies on optimization of the reaction between 2-aminoacetophenone and o-(trimethylsilyl)phenyl triflate focused on determining the appropriate solvent. The major by-product in this annulation reaction, which can also be isolated by column chromatography, is the N-arylated product C (Scheme 1). The by-product is formed when the aryl carbanion of intermediate A is protonated, therefore preventing it from attacking the neighboring carbonyl group (Route B).

Scheme 1.

Proposed Mechanism

Formation of the desired annulated product over the arylated by-product can sometimes be sensitive to solvents containing acidic protons, such as acetonitrile (MeCN).11 In our reaction, however, MeCN proved to be a superior solvent over tetrahydrofuran (THF) (another commonly used solvent in benzyne chemistry), when CsF is used as the benzyne initiator (Table 1, entries 1–5). It’s worth mentioning that even though one equiv of water [a proton source that can promote Route B (Scheme 1)] is formed for every equiv of acridine produced, the addition of drying agents, such as molecular sieves, MgSO4, CaO, or MgO, failed to improve the overall yield. However, this observation is not entirely surprising, since at least 4 other sources of protons are expected to be present in the reaction mixture at any given time; the ammionium cation and the methyl ketone (both sources can provide protons intra- or intermolecularly), unreated amine, and the solvent (MeCN). DME is the best solvent when employing 3 equiv of tetrabutylammonium triphenyldifluorosilacate (TBAT) as the fluoride source (Table 1, entry 13). The remaining key reaction parameters, time, temperature, etc. have been examined and it has been found that 1.2 equiv of the benzyne precursor and 3.6 equiv of CsF in MeCN (10 mL) at 65 °C affords the highest yield of acridine (entry 1 = conditions A). As an alternative set of reaction conditions, 1.4 equiv of benzyne precursor and 4.2 equiv of TBAT in THF (10 mL) at ambient temperature can be used (entry 13 = conditions B).

Table 1.

Optimization Studiesa

| entry | aryne precursor (equiv) | fluoride (equiv)b | solvent (mL) | temp (°C) | % yieldc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.2 | CsF (3) | MeCN (10) | 65 | 70 |

| 2 | 1.4 | CsF (3) | MeCN (10) | 65 | 66 |

| 3 | 1.6 | CsF (3) | MeCN (10) | 65 | 52 |

| 4 | 1.2 | CsF (2) | MeCN (10) | 65 | 65 |

| 5 | 1.2 | CsF (4) | MeCN (10) | 65 | 62 |

| 7 | 1.2 | CsF (3) | THF (10) | 65 | 15 |

| 8 | 1.2 | TBAT (3) | THF (10) | RT | 52 |

| 9 | 1.4 | TBAT (3) | THF (10) | RT | 67 |

| 10 | 1.4 | TBAT (2) | THF (10) | RT | 63 |

| 11 | 1.4 | TBAT (4) | THF (10) | RT | 69 |

| 12 | 1.4 | TBAT (3) | THF (10) | RT | 64 |

| 13 | 1.4 | TBAT (3) | DME (10) | RT | 70 |

| 14 | 1.2 | TBAT (3) | DME (5) | RT | 64 |

To a sealed 6 dram vial containing 2-aminoacetophenone, the benzyne precursor, a stir bar, and half the total volume of solvent, was added CsF, followed by the remainder of the solvent. The reaction was sealed and allowed to stir for a given time before brine (10 mL) was added. The organic layer was removed and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 15–25 mL). The combined organic layers were dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated in vacuo before anisole (~50 mg) was added for quantitative 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis.

Equiv of CsF per one equiv of aryne precursor.

1H NMR spectroscopic yield.

With two sets of optimized reaction conditions in hand, a series of ortho-aminoaryl carbonyl compounds has been examined in this process, including ortho-aminoacetophenones, ortho-aminobenzophenones, and ortho-aminoanthraquinones (Table 2). The parent system gave a respectable 70% yield under both sets of reaction conditions. When inductively electron-withdrawing groups, such as 4,5-dimethoxy (2a) and 4,5-methylenedioxy (3a) groups, were introduced onto the aromatic ring, conditions A gave increased yields, while conditions B gave the opposite results (entries 3–6). A similar result was obtained with 2-amino-3,5-dibromoacetophenone (entries 7 and 8). It is hypothesized that the favorable performance of this substrate may be attributed to the steric bulkiness of the 3-bromo substituent, in that its large size can push the nitrogen lone pair out of conjugation, thus increasing the nucleophilicity of the nitrogen. In general, it is observed that substrates containing both electron-donating groups and halogens are tolerated well under our optimized reaction conditions. In addition, conditions A proved to be more effective for all acetophenones examined. This trend is not observed for the benzophenones (entries 9–18). In fact, conditions B proved to give better results overall with these substrates, although the reason is not yet completely understood. Consistent with the acetophenones is the fact that benzophenones containing electron-donating groups or halogens are well tolerated and give good yields of the corresponding acridines when reacted with benzyne (entries 11–18). As demonstrated in entries 13–16, a chlorine substituent can be placed on either ring of the benzophenone system and the overall yield is not affected. In general, all of the benzyne reactions with the benzophenones afford clean thin layer chromatograms, except the reaction of 2-amino-5-nitrobenzophenone, which gave a complicated, inseparable mixture. We were pleased to see that 2-aminoanthraquinone (11a) reacted with benzyne efficiently using conditions A to produce the corresponding fused 6-membered ring system 11b (entries 20–21). Although, only moderate yields were obtained, 2-aminofluorenone (13a) reacted with benzyne to form another fused 5-membered ring system (entry 23–24). The central 5-membered ring of the fluorenone substrate increases the intramolecular distance between the nucleophile and the electrophile and this may explain the decrease in yield when compared with the corresponding benzophenone and anthraquinone systems (entries 9–10 and 20–21).

Table 2.

Reactions of Benzyne with Amine-containing Acetophenones, Benzophenones, and Anthraquinones

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate | product | conditions a | % yield | |

|

R= |  |

|||

| 1 2 |

1a | H | 1b | A B |

70 70 |

| 3 4 |

2a | 4,5-(OMe)2 | 2b | A B |

78 55 |

| 5 6 |

3a | 4,5-(OCH2)2 | 3b | A B |

78 68 |

| 7 8 |

4a | 3,5-Br2 | 4b | A B |

77 71 |

|

R= |  |

|||

| 9 10 |

5a | H | 5b | A B |

68 72 |

| 11 12 |

6a | 4-Me | 6b | A B |

71 72 |

| 13 14 |

7a | 5-Cl | 7b | A B |

71 80 |

| 15 16 |

8a | 4′-Cl | 8b | A B |

72 77 |

| 17 18 |

9a | 5-Cl,2′-F | 9b | A B |

51 72 |

| 19 | 10a | 5-NO2 | Complicated mixture | A | - |

|

R= |  |

|||

| 20 21 |

11a | H | 11b | A B |

70 <10 |

| 22 | 12a | 6-Cl | 12b | A | 40 |

| 23 24 |

13a 13a |

13b 13b |

A B |

53 <10 |

|

|

R= |  |

|||

| 25 26 |

14a | H | 14b | A B |

38b, 30 38b |

| 27 | 15a | 5-Cl | 15b | A | 30 |

The experimental details for conditions A and conditions B can be found in the Experimental Section.

This reaction was performed at 0 °C.

Lastly, a couple of 2-aminobenzaldehydes were examined. However, yields were drastically reduced (entries 25–27). For example, the parent aldehyde substrate, 2-aminobenzaldehyde (14a), gave only a 38% yield of the desired product, even though the crude mixture produced a thin layer chromatogram indicating only one spot and the starting material was entirely gone (entry 25). Concern that the substrate might self polymerize, as warned by the manufacturer, forced us to run the reaction at 0 °C. Our hesitation in heating the reaction mixture was supported by the results reported in entry 25 where an even lower yield was obtained. Aminobenzaldehyde 15a gave a low yield similar to 14a, when reacted with benzyne.

After a number of carbonyl substrates were examined, we turned our focus to other arynes (Table 3). Initially, symmetrical benzynes were investigated, thus regioisomeric product mixtures were avoided. The parent substrate 1a and benzyne precursor 16b reacted to afford acridine 16c (entry 1) in a lower yield compared to that of entry 1 of Table 1. This trend was also observed when substrate 2a was allowed to react with the same benzyne precursor (entry 2). On the other hand, substrate 4a gave an improved yield when compared with entry 7 of Table 1. Substrate 4a performed well in all cases. For example, nearly quantitative yields of the desired acridines were obtained in the reactions reported in entries 5 and 7. Again, this may best be explained by the steric bulkiness of the 3-bromo substituent next to the amino group, as it can push the nitrogen lone pair out of conjugation, thus making it more nucleophilic towards the aryne. To our delight, the anthraquinone 11a afforded a good yield, even when reacted with the more electron-rich benzyne precursor 17b (entry 6).

Table 3.

Reactions of ortho-Aminoaryl Ketones with Various Aryne Precursors.a

| entry | substrate | aryne | product | % yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

1a 1a

|

16b 16b

|

16c 16c

|

51 |

| 2 |

2a 2a

|

16b 16b

|

17c 17c

|

36 |

| 3 |

4a 4a

|

16b 16b

|

18c 18c

|

82 |

| 4 |

2a 2a

|

17b 17b

|

19c 19c

|

52 |

| 5 |

4a 4a

|

17b 17b

|

20c 20c

|

96 |

| 6 |

11a 11a

|

17b 17b

|

21c 21c

|

70 |

| 7 |

4a 4a

|

18b 18b

|

22c 22c

|

95 |

| 8 |

6a 6a

|

18b 18b

|

23c 23c

|

88 |

| 9 |

6a 6a

|

19b 19b

|

24c 24c

|

82 |

| 10 |

9a 9a

|

19b 19b

|

25c 25c

|

55 |

All reactions were carried out using reaction conditions A (see the Experimental Section).

Isolated yields.

We next explored some unsymmetrical benzyne precursors in order to establish the regioselectivity of our methodology. First, benzyne precursor 18b was examined and, as expected, based on previous related literature,32 the reaction with substrate 4a led to only one regioisomer in an excellent yield (entry 7). The structure of this compound was confirmed by 2D-NOE experiments (see the Supporting Information). Substrate 6a efficiently reacted with 18b to produce a single regioisomer as well (entry 8). In addition, the naphthalyne precursor 19b demonstrated impressive regioselectivity, where the amino group attacks the least hindered carbon of the aryne. Thus, the reactions of 19b with substrates 6a and 9a produced the single regioisomers 24c and 25c, respectively. The structure of 24c was established through X-ray crystallography (see the Supporting Information).

This acridine synthesis is thought to proceed through the mechanism proposed in Scheme 1. After the benzyne is generated through fluorine induced 1,2-elimination of TMS-OTf, the nucleophilic amino group of the ortho-aminoaryl carbonyl compound attacks one end of the benzyne unsaturation generating aryl carbanion A, which can follow one of two paths, Route A or Route B. Route A produces the desired product through attack on the carbonyl group by intermediate A to form a zwitterion B, which then undergoes a proton transfer, followed by subsequent dehydration. As previously mentioned, the major by-product observed in these reactions is arylation of the nitrogen, which presumably proceeds via Route B. It is believed that the proton transfer occurs intramolecularly from the ammonium intermediate, rather than the water produced in the reaction, since the addition of drying agents did not beneficially affect the overall yield.

Conclusions

Acridines have proven to be important in many areas of chemistry, including medicine and materials. So far, however, only methodologies requiring harsh, functionality-intolerant conditions have been reported. As a result, there exists a need for a methodology that is mild enough to tolerate a diverse array of functionality, while remaining practical in terms of the length of the synthesis. We have developed a convenient and mild methodology for the construction of acridines in one step starting from commercially available ortho-aminoacetophenones, ortho-aminobenzophenones, and ortho-aminoanthraquinones, and appropriate aryne precursors. Ortho-aminobenzaldehydes, on the other hand, give poor yields when subjected to our optimized reaction conditions. Although it’s hypothesized that these aldehydes may be self-polymerizing, this has not been proven and currently we are exploring alternative conditions. Some unsymmetrical aryne precursors, when reacted with our amino carbonyl substrates, led to single regioisomers in good yields.

Experimental Section

Representative Procedure for the Annulation of Arynes and 2-Aminoaryl Carbonyl Compounds

Conditions A: to a dry 5 dram vial containing a solution of amino substrate (0.5 mmol) and the aryne precursor (0.6 mmol) in MeCN (10 mL, anhydrous) was added CsF (1.8 mmol). The vial was sealed and placed in an oil bath, where it was allowed to stir for 24 h at 65 °C. The reaction mixture was then poured into brine (5 mL) and the organic layer was separated. The water layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 15 mL) and the organic layers were combined, dried (Na2SO4), and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was then subjected to flash chromatography using gradient solvent combinations of ethyl acetate and hexane or dichloromethane and hexanes to yield a 71% yield of 6b as a yellow solid; mp = 149–151 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) d 8.26 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 8.05 (s, 1 H), 7.75 (ddd, J = 1.2, 6.4, 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.55–7.62 (m, 4 H), 7.37–7.44 (m, 3 H), 7.25 (dd, J = 1.6, 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 2.60 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) d 149.3, 149.0, 147.0, 140.5, 136.2, 130.6, 129.9, 129.6, 128.59, 128.55 128.0, 127.0, 126.6, 125.3, 125.0, 123.7, 115.5, 22.3; HRMS (EI): calcd for C20H15N 269.1205, found 269.1209. Conditions B: to a dry 5 dram vial containing a solution of the amino substrate (0.5 mmol) and aryne precursor (0.7 mmol) in DME (10 mL, anhydrous), was added TBAT (2.1 equiv). The vial was sealed and the mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for 24 h. The work-up and purification procedures for conditions A were then employed to yield a 72% yield of compound 6b (see Conditions A for characterization data).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM070620 and GM079593) and the National Institutes of Health Kansas University Center of Excellence in Chemical Methodology and Library Development (P50 GM069663) for their generous financial support, as well as Dr. Feng Shi for his help in the preparation of some of the aryne precursors. We also thank Dr. Arkady Ellern and the Molecular Structure Laboratory of Iowa State University for their help with the x-ray crystallography.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and characterization of previously unreported products. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Chen Y, Larock RC. In: Modern Arylation Methods. Ackerman J, editor. Wiley/VCH; New York: 2009. p. 401. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beller MA, Breindl C, Riermeier TH, Tillack A. J Org Chem. 2001;66:1403. doi: 10.1021/jo001544m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang XC, Liu YL, Liang Y, Pi SF, Wang F, Li JH. Org Lett. 2008;10:1525. doi: 10.1021/ol800051k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon S, Wang X, Lam KS, Kurth MJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:7443. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi F, Waldo JP, Chen Y, Larock RC. Org Lett. 2008;10:2409. doi: 10.1021/ol800675u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida H, Fukushima H, Oshita J, Kunai A. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11040. doi: 10.1021/ja064157o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larrosa I, Da Silva MI, Gomez PM, Hannen P, Ko E, Lenger SR, Linke SR, White AJP, Wilton D, Barret AGM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14042. doi: 10.1021/ja0662671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mal D, Senapati BK, Pahari P. Synlett. 2005:994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanz R, Fernández Y, Castroviejo MP, Pérez A, Fañanás FJ. J Org Chem. 2006;71:6291. doi: 10.1021/jo060911c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pawlas J, Begtrup M. Org Lett. 2002;4:2687. doi: 10.1021/ol026197c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Zhao J, Larock RC. J Org Chem. 2007;72:583. doi: 10.1021/jo0620718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhao J, Larock RC. Org Lett. 2005;7:4273. doi: 10.1021/ol0517731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denny WA. Med Chem Rev Online. 2004;1:257. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Oppegard LM, Ougolkov AV, Luchini DN, Schoon RA, Goodell JR, Kaur H, Billadeau DD, Ferguson DM, Hiasa H. Eur J Pharm. 2009;602:223. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Goodell JR, Ougolkov AV, Hiasa H, Kaur H, Remmel R, Billadeau DD, Ferguson DM. J Med Chem. 2008;51:179. doi: 10.1021/jm701228e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kapuriya N, Kapuriya K, Zhang X, Chou TC, Kakadiya R, Wu YT, Tsai TH, Chen YT, Lee TC, Shah A, Naliapara Y, Su TL. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:5413. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Martins C, Gunaratnam M, Stuart J, Makwana V, Greciano O, Reszka AP, Kelland LR, Neidle S. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;17:2293. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Nelson EM, Tewey KM, Liu LF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:1361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belmont P, Dorange I. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2008;18:1211. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taraporewala IB. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:39. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Wainwright M. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;47:1. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kavitha HP. Asian J Chem. 2004;16:1191. [Google Scholar]; (c) Patel CL, Parekh H. Ind Chem Soc. 1988;65:282. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Fattorusso C, Campiani G, Kukreja G, Persico M, Butini S, Romano MP, Altarelli M, Ros S, Brindisi M, Savini L, Novellino E, Nacci V, Fattorusso E, Parapini S, Basilico N, Taramelli D, Yardley V, Croft S, Borriello M, Gemma S. J Med Chem. 2008;51:1333. doi: 10.1021/jm7012375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Giorgio CD, Shimi K, Boyer G, Delmas F, Galy JP. Eur J Med Chem. 2007;42:1277. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Stocks PA, Bray PG, Barton VE, Helal MA, Jones M, Araujo NC, Gibbons P, Ward SA, Hughes RH, Biagini GA, Davies J, Amewu R, Mercer AE, Ellis G, O’Neill PM. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:6278. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chauhan PMS, Srivastava SK. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:1535. doi: 10.2174/0929867013371851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel NA, Sruthi SC, Patel RD, Patel MP. Phosphorus, Sulfur, Silicon Relat Elem. 2008;183:2191. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolphin GT, Chierici S, Ouberai M, Dumy P, Garcia J. Chembiochem. 2008;9:952. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee Y, Hyun S, Kim HJ, Yu J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;47:134. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan P, Xie A, Wei M, Loew LM. J Org Chem. 2008;73:657. doi: 10.1021/jo800852h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C, Sun P, Yan L, Pan Yi, Cheng CH. Thin Solid Films. 2008;516:6186. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Bernthsen A. Ann. 1878;192:1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bernthsen A. Ann. 1884;224:1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popp FD. J Org Chem. 1962;27:2658.For recent synthetic routes to 9-methylacridine, see: Crawford LA, McNab H, Mount AR, Wharton SI. J Org Chem. 2008;73:6642. doi: 10.1021/jo800637u.Joseph J, Kuruvilla E, Achuthan AT, Ramaiah D, Schuster GB. Bioconjugate Chem. 2004;15:1230. doi: 10.1021/bc0498222.

- 25.(a) Sourdon V, Mazoyer S, Pique V, Galy JP. Molecules. 2001;6:673. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lartia R, Bertrand H, Teulade-Fichou MP. Synlett. 2006:610. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ferencz L, Farcasan V, Silberg IA. Rev Roum Chim. 2003;48:801. [Google Scholar]; (d) Kamal A, Srinivas O, Ramulu P, Ramesh G, Kumar PP. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:4107. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.04.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Antonini I, Polucci P, Magnano A, Gatto B, Palumbo M, Menta E, Pescalli N, Martelli S. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3109. doi: 10.1021/jm030820x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Wu M, Wu W, Gao X, Lin X, Xie Z. Talanta. 2008;75:995. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2007.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gopinath VS, Thimmaiah P, Thimmaiah KN. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:474. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Scarpellini-Charras K, Boyer G, Filloux N, Galy JP. J Heterocyl Chem. 2008;45:67. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraleoni-Morgera A, Zanirato P. Arkivoc. 2006;(xii):111. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoon K, Ha SM, Kim K. J Org Chem. 2005;70:5741. doi: 10.1021/jo050420c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silber J, Shine H. J Org Chem. 1971;36:2923. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Himeshima Y, Sonoda T, Kobayashi H. Chem Lett. 1983:1211. [Google Scholar]

- 31.(a) Hendrickson JB, Rees R. J Am Chem Soc. 1961;83:1250. [Google Scholar]; (b) Taylor EC, Heindel ND. J Org Chem. 1967;32:1666. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sinsky MS, Bass RG. J Heterocycl Chem. 1984;21:759. [Google Scholar]

- 32.(a) Liu Z, Shi F, Martinez PDG, Raminelli C, Larock RC. J Org Chem. 2008;73:219. doi: 10.1021/jo702062n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Blackburn T, Romtohul YK. Synlett. 2008:1159. [Google Scholar]; (c) Jayanth TT, Cheng CH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:5921. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.