Abstract

Parkinson's disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) frequently overlap with Alzheimer's disease, which is linked to brain impairments in insulin, insulin-like growth factor (IGF), and neurotrophin signaling. We explored whether similar abnormalities occur in PD or DLB, and examined the role of manganese toxicity in PD/DLB pathogenesis. Quantitative RT-PCR demonstrated reduced expression of insulin, IGF-II, and insulin, IGF-I, and IGF-II receptors (R) in PD and/or DLB frontal white matter and amygdala, and reduced IGF-IR and IGF-IIR mRNA in DLB frontal cortex. IGF-I and IGF-II resistance was present in DLB but not PD frontal cortex, and associated with reduced expression of Hu, nerve growth factor, and Trk neurotrophin receptors, and increased levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein, α-synuclein, dopamine-β-hydroxylase, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE), and ubiquitin immunoreactivity. MnCl2 treatment reduced survival, ATP, and insulin, IGF-I and IGF-II receptor expression, and increased α-synuclein, HNE, and ubiquitin immunoreactivity in cultured neurons. The results suggest that: 1) IGF-I, IGF-II, and neurotrophin signaling are more impaired in DLB than PD, corresponding with DLB's more pronounced neurodegeneration, oxidative stress, and α-synuclein accumulation; 2) MnCl2 exposure causes PD/DLB associated abnormalities in central nervous system neurons, and therefore may contribute to their molecular pathogenesis; and 3) molecular abnormalities in PD/DLB overlap with but are distinguishable from Alzheimer's disease.

Keywords: Central nervous system, dementia with Lewy bodies, human, insulin-like growth factor resistance, neurotrophin, Parkinson's disease, receptor-ligand binding

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson's disease (PD) is the second most common form of neurodegeneration in the Western hemisphere, exceeded in prevalence only by Alzheimer's disease (AD). PD is associated with a resting tremor, reduced voluntary movements, increased rigidity and stiffness, bradykinesia, and postural instability. Afflicted individuals exhibit a shuffling gait with “en bloc” turning, stooped posture, and dystonia. Motor impairments result in hypophonia, non-intelligible or monotonous speech, and dysphagia with eventual death from aspiration pneumonia. In addition, PD is frequently accompanied by neuropsychiatric and cognitive dysfunction including depression, abulia, hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, memory deficits, decline in executive function, and dementia. Finally, PD can be associated with sleep disorders such as insomnia, orthostatic hypotension, impaired proprioception, anosmia, increased musculoskeletal and neuropathic pain, and autonomic dysfunction resulting in urinary incontinence, nocturia, gastrointestinal dysmotility, altered sexual function, and weight loss [1,2]. Together, this constellation of central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities points toward a neurodegenerative process that targets many brain structures, beyond those integrally related to local nigrostriatal circuitry. When PD is associated with prominent and progressive neuropsychiatric symptoms and dementia, it is termed dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Alternatively, if the postmortem histopathological features show extensive overlap with AD, the entity may be termed, Lewy body variant of AD. Moreover, PD can be a component of other major neurodegenerative diseases including multiple systems atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal ganglionic degeneration.

Motor symptoms of PD are caused by degeneration of large pyramidal pigmented,dopaminergic neurons in the pars compacta zone of the substantia nigra, together with projection fibers to the striatum. Interruption of these pathways results in increased inhibition of neurons in the ventrolateral nucleus of the thalamus, and consequently, loss of excitatory input to the motor cortex, and attendant hypokinesia. In addition, PD/DLB exhibit degeneration of adrenergic neurons in the locus ceruleus with loss of projections to the thalamus. PD/DLB is characteristically associated with Lewy body formation in degenerating pigmented brainstem neurons. Lewy bodies are intraneuronal eosinophilic inclusions that contain aggregated and ubiquitinated α-synuclein protein [3-6]. Fundamental to the PD/DLB neurodegeneration cascade is impaired transport of α-synuclein-ubiquitin complexes from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the Golgi [7], resulting in their accumulation in neurons, along with iron and copper, which enhance oxidative stress [8]. Iron accumulation and oxidative stress cause α-synuclein-ubiquitin complexes to aggregate and further accumulate, thereby exacerbating neuronal oxidative stress.

Like AD, the vast majority of PD represents sporadic occurrences of unknown etiology, whereas less than 10% of the cases are familial. Familial PD has been linked to mutations or polymorphisms in PARK genes that have been mapped to chromosomes 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, or X [9-14]. Of note is that PARK1 encodes the α-synuclein, and PD arising from PARK1 mutations has autosomal dominant inheritance [9,11,13]. The PARK2 gene encodes Parkin protein, and mutations in PARK2 account for a large percentage of familial PD [12,14,15]. PARK5 encodes ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydroxylase L1 [16,17], which is of particular interest because of its role in ubiquitination and accumulation of α-synuclein-containing insoluble protein aggregates in PD/DLB CNS neurons. Despite these striking and somewhat informative familial linkages to PD, germline PARK gene mutations each account for relatively small percentages of the overall number of PD/DLB cases. Moreover, genetic factors alone are not likely to be sufficient to confer a PD/DLB phenotype since their effects are generally not manifested until individuals reach middle or old age. In essence, aside from aging, specific factors, i.e., “second hits” responsible for initiating critical events in the PD/DLB neurodegeneration cascade have not yet been determined [10,18,19].

Epidemiological and experimental data suggest that PD-type neurodegeneration may be mediated by environmental exposures to toxins, e.g., polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), paraquat, rotenone, and 1-methyl 4-phenyl 1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP); pesticides, e.g., dieldrin and lindane; or transition metals, e.g., manganese and iron [20-22]. In addition, PD and α-synuclein pathology can be produced by head trauma [23,24] or chronic treatment with antipsychotic drugs that inhibit dopamine and promote dopamine receptor resistance [25,26]. More recently, interest in the role of exposures leading to altered metabolic states has grown due to emerging evidence that the risks for developing AD and PD have increased with the epidemic rise in prevalence of obesity and type II diabetes [27]. In this regard, epidemiological studies demonstrated a significantly increased risk for developing PD in individuals with central obesity [28,29], whereas caloric restriction was found to ameliorate neurotrophin deficiency in an experimental model of PD [30]. Given the frequent clinical, pathological, and biochemical overlap between AD and PD/DLB, and evidence that AD is mediated by brain insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) resistance and deficiency in humans and experimental animal models [31-34], it was of interest to determine if molecular abnormalities in brain insulin/IGF signaling mechanisms are also impaired in PD/DLB. Moreover, we extended our studies to examine expression of neurotrophin genes because of their prominent levels of expression in subcortical nuclei, which are commonly damaged by PD and/or DLB [35-38]. Finally, in light of the potential role of environmental factors, particularly manganese exposure, in the pathogenesis of PD/DLB [39-45], we investigated the extent to which molecular and biochemical abnormalities related to insulin/IGF signaling in PD/DLB could be reproduced experimentally in neurons exposed to MnCl2.

METHODS

Human subjects

We obtained human postmortem brain tissue from eight controls, seven cases of PD, and eight cases of DLB from the Massachusetts General Hospital ADRC brain bank. Brains were harvested and stored as previously described [32]. All diagnoses were confirmed by standardized histopathological examination using guidelines established by the DLB Consortium [46]. The mean ages and sex ratios were similar for the three groups (Table 1). Fresh, snap-frozen samples of anterior frontal cortex and white matter (Brodmann Area 9-separately analyzed), amygdala, and lenticular nuclei (putamen + globus pallidus) were used to measure mRNA and protein expression. In addition, frontal cortex was used in competitive equilibrium receptor binding assays to detect insulin, IGF-I, or IGF-II resistance. Adjacent paraffin-embedded histological sections were used for immunohistochemical staining to detect α-synuclein, dopamine β-hydroxylase (DβH), 4-hydroxy-2-nonenol (HNE), or ubiquitin using previously described methods [32]. The brain regions selected for study represent targets of PD and/or DLB neurodegeneration [17,47].

Table 1.

Patient population profile

| Control | PD | DLB | P-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 8 | 7 | 8 | |

| Age (yrs)* | 79.9 ± 5.2 | 83.4 ± 2.1 | 81.7 ± 1.7 | NS |

| Male/Female | 5/3 | 6/1 | 5/3 | NS |

| Brain Wt (gm)* | 1293 ± 51 | 1311 ± 94 | 1001 ± 383 | NS |

| PMI (hrs)* | 9.5 ± 2.0 | 8.6 ± 1.4 | 8.4 ± 1.8 | NS |

PD = Parkinson's disease; DLB = dementia with Lewy Bodies; PMI = postmortem interval; NS = not significant.

± S.D.

Quantitative (q) RT-PCR assays

Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), reverse transcribed with random oligodeoxynucleotide primers, and the resulting cDNAs were used to measure mRNA expression by qRTPCR. Ribosomal 18S RNA was measured in parallel reactions to calculate relative abundance of each mRNA transcript [33,34]. PCR amplifications were performed in 20 μl reactions containing cDNA generated from 2.5 ng of original RNA template, 300 nM each of gene specific forward and reverse primer (Tables 2A and 2B), and 10 μl of 2× QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Mix (Qiagen Inc, Valencia, CA). The amplified signals were detected continuously with the Mastercycler ep realplex instrument and software (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) as previously described [48]. Annealing temperatures were optimized using the temperature gradient program provided with the Mastercycler ep realplex software. PCR primer pairs were designed using MacVector 9 (Cary, North Carolina), verified by BLAST Sequence analysis through the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website and commercially synthesized (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO).

Receptor binding assays

Competitive equilibrium binding assays were performed according to previously published methods [31,32]. Briefly, fresh frozen tissue was homogenized in NP-40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA) containing protease (1 mM PMSF, 0.1 mM TPCK, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 0.5 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM Na4P2O7) inhibitors. Protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Duplicate samples containing equivalent amounts of protein were incubated with 100 nCi/ml of [125I] (2000 Ci/mmol; 50 pM) insulin, IGF-I, or IGF-II for 16 hours at 4°C. To measure non-specific binding, additional duplicate samples were identically prepared but with the addition of 0.1 μM unlabeled (cold) ligand. Bound radiolabeled tracer was precipitated with bovine gamma globulin and polyethylene glycol 8000. Radioactivity distributed in the supernatants (containing free ligand) and pellets (containing bound ligand) was measured in an LKB CompuGamma CS Gamma counter. Specific binding was calculated by subtracting fmol of nonspecific binding, i.e., amount bound in the presence of cold ligand, from the total fmol bound (absence of unlabeled competitive ligand). The results were analyzed and plotted using the GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbant Assays (ELISAs)

Immunoreactivity was detected in tissue or cellular homogenates using direct binding ELISAs as previously described [49]. Briefly, homogenates were prepared in radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1% NP-40, 0.25% Na-deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA) containing protease inhibitors as indicated earlier. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA assay. Protein homogenates diluted to in Tris buffered saline (TBS) (40 ng in 100 μl) were adsorbed to the bottoms of the wells at 4°C. Non-specific binding was blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBS. Primary antibody (0.01–0.1 μg/ml) was applied for 1 hour at room temperature, after which immunoreactivity was detected with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10000; Pierce) followed by Amplex Red (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Fluorescence was measured (Ex 530/Em 590) in a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). Negative controls included use of non-relevant monoclonal antibody (mAb) to Hepatitis B Surface antigen as the primary antibody, omission of the primary or secondary antibody, or coating of wells with 3% BSA instead of sample.

Primary rat cerebellar neuron cultures

Primary neuronal cultures were generated with postnatal day 8 rat pup cerebella [51] and maintained with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum, 4 mM glutamine, 10 mM non-essential amino acid mixture (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY), 25 mM KCl, and 9 g/L glucose. Five-day-old cultures were treated with 0, 10, 20 or 40 μM MnCl2 for 48 hours, after which they were harvested for qRT-PCR, ELISA, or cellular ELISA studies. PCR primer pairs used in these experiments were published previously [51].

Cellular ELISA

A cellular ELISA was used to measure immunoreactivity directly in cultured cells (96-well plates) [50]. The only modification of the original protocol was that immunoreactivity was detected with the Amplex Red fluorophore (Ex 530/Em 590) (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and measured in a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Dynamics, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA). Cell density was assessed by measuring fluorescence after staining the cells with Hoechst H33342 (Ex360 nm/Em460 nm; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The calculated ratios of fluorescence immunoreactivity to H33342 were used for inter-group comparisons. At least 8 replicate cultures were analyzed in each experiment.

Sources of reagents

Human recombinant [125I] insulin, IGF-I, and IGFII were purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). Unlabeled recombinant human insulin, IGF-I and IGF-II were purchased from Bachem (King of Prussia, PA). Antibodies to Hu, myelin-associated glycoprotein-1 (MAG-1), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), growth associated protein-43 (GAP-43), α-synuclein, DβH, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanine (8-OHdG), ubiquitin, HNE, and β-actin were purchased from AbCam (Cambridge, MA). ATPLite assay kit was obtained from Perkin-Elmer (Waltham, MA). Amplex Red and Hoechst H33342 dye were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). All other fine chemicals and reagents were purchased from CalBiochem (Carlsbad, CA) or Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Statistical analysis

Data are depicted as means ± S.E.M. in the graphs. Inter-group comparisons were made using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the post-hoc Dunn's multiple comparison test of statistical significance. In addition, trend lines were analyzed using Deming linear regression. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Significant P-values and trends are indicated over the graphs.

RESULTS

Pathologic shifts in cell populations in PD and DLB (Table 3)

Table 3.

Pathological shifts in gene expression corresponding to distinct cell populations in PD and DLB brains

| mRNA | CONTROL | PD | DLB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRONTAL CORTEX | ||||||

| Hu | 0.310 | ±0.018 | 0.162 | ±0.088* | 0.087 | ±0.022* |

| MAG | 0.673 | ±0.124 | 1.083 | ±0.282 | 0.179 | ±0.041**† |

| GFAP | 1.265 | ±0.556 | 26.61 | ±21.34 | 62.85 | ±25.88*** |

| IBA | 0.012 | ±0.009 | 0.117 | ±0.089 | 0.010 | ±0.003* |

| ET1 | 0.375 | ±0.063 | 0.367 | ±0.137 | 0.091 | ±0.036 |

| FRONTAL WHITE MATTER | ||||||

| Hu | 0.214 | ±0.034 | 0.223 | ±0.052 | 0.035 | ±0.006* |

| MAG | 4.66 | ±0.912 | 0.731 | ±0.148* | 0.538 | ±0.155* |

| GFAP | 1.114 | ±0.210 | 29.95 | ±7.689* | 25.18 | ±8.708* |

| IBA | 0.008 | ±0.003 | 0.120 | ±0.038* | 0.094 | ±0.050 |

| ET1 | 0.452 | ±0.017 | 0.312 | ±0.051 | 0.217 | ±0.079* |

| AMYGDALA | ||||||

| Hu | 0.437 | ±0.038 | 0.108 | ±0.055*** | 0.047 | ±0.012*** |

| MAG | 1.999 | ±0.134 | 2.200 | ±0.515 | 1.639 | ±0.399 |

| GFAP | 0.792 | ±0.156 | 49.97 | ±5.327*** | 29.34 | ±3.654*** |

| IBA | 0.052 | ±0.016 | 0.084 | ±0.014 | 0.087 | ±0.013 |

| ET1 | 0.317 | ±0.039 | 0.337 | ±0.055 | 0.373 | ±0.071 |

| BASAL GANGLIA | ||||||

| Hu | 0.035 | ±0.002 | 0.030 | ±0.007 | 0.009 | ±0.002** |

| MAG-1 | 1.350 | ±0.061 | 0.413 | ±0.081 | 0.373 | ±0.092 |

| GFAP | 5.973 | ±0.520 | 10.54 | ±1.773* | 17.79 | ±5.922* |

| IBA | 0.0003 | ±2E-06 | 0.063 | ±0.016*** | 0.033 | ±0.006*** |

| ET1 | 0.434 | ±0.083 | 0.085 | ±0.018* | 0.149 | ±0.012* |

MAG-myelin associated glycoprotein; GFAP-glial fibrillary acidic protein; IBA-allograft inhibitory factor; ET-endothelin. Gene expression was measured by qRT-PCR analysis with values (×10−6) normalized to 18S rRNA measured in parallel reactions. Inter-group comparisons were made using repeated measures ANOVA with the post hoc Dunn's multiple comparison test.

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.005 relative to control;

P<0.05 or better relative to PD.

Previous studies demonstrated significant pathological shifts in brain cell populations that correlated with neuronal and oligodendroglial cell loss, gliosis, and neuroinflammation in AD [31]. To determine if PD and DLB were associated with similar abnormalities, we measured relative mRNA levels of Hu neuronal ribosomal RNA binding protein [52,53]; myelin-associated glycoprotein-1 (MAG-1), a marker of oligodendrocytes; GFAP, which is expressed in astrocytes; endothelin-1 (ET-1), a marker of endothelial cells; and ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule-1 (IBA-1), a gene expressed in activated microglia [54,55]. The ng quantities of mRNA were normalized to 18S rRNA in corresponding samples. mRNAs isolated from different brain regions were analyzed simultaneously. The studies demonstrated that Hu expression was significantly reduced relative to control in PD and DLB frontal cortex and amygdala, and in DLB but not PD frontal white matter and basal ganglia. MAG-1 expression was significantly reduced in PD and DLB fontal white matter and basal ganglia, and in DLB frontal cortex. GFAP expression was significantly increased in all brain regions of DLB cases, but only in subcortical nuclei, i.e., amygdala and basal ganglia in PD. ET-1 expression was significantly reduced in DLB cortex, white matter, and basal ganglia, and in PD basal ganglia. Finally, evidence of neuroinflammation was detected in PD frontal cortex, white matter, and basal ganglia, and DLB basal ganglia. Within each brain region, the mean levels of 18S rRNA were similar among the groups.

PD and DLB associated abnormalities in expression of insulin, IGF-I, and IGF-II polypeptide and receptor genes

qRT-PCR studies detected mRNA transcripts corresponding to insulin, IGF-I, and IGF-II polypeptides and receptors in control, PD, and DLB samples (Table 4). Insulin gene was most abundantly expressed in the amygdala followed by frontal cortex and white matter. IGF-I was most abundantly expressed in white matter followed by amygdala, and similarly lower levels were observed in frontal cortex and basal ganglia. IGF-II was the least abundantly expressed of the three growth factors, and the patterns of expression mirrored those of insulin, except that IGF-II transcripts were not detected in basal ganglia. Insulin gene expression was significantly reduced in PD and DLB white matter and amygdala. IGF-I expression was not reduced in PD/DLB, and instead was significantly elevated in PD frontal cortex. IGF-II expression, like insulin, was significantly reduced in PD and DLB frontal white matter. With regard to the receptors (R), IGF-IR was most abundant, followed by IGF-IIR, and then insulin-R. Insulin-R expression was significantly reduced in PD and DLB white matter, and in DLB amygdala. IGF-IR mRNA was significantly reduced in DLB frontal cortex and frontal white matter, and in PD frontal white matter. IGF-IR expression was significantly increased in PD and DLB amygdala. IGF-IIR expression was significantly reduced in DLB frontal cortex, but increased in the amygdala and basal ganglia relative to control.

Table 4.

Altered expression of insulin and IGF polypeptide and receptor genes in PD and DLB

| mRNA | CONTROL | PD | DLB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRONTAL CORTEX | ||||||

| INR | 0.006 | ±0.0003 | 0.003 | ±0.001 | 0.004 | ±0.001 |

| IGF1R | 28.97 | ±2.44 | 12.94 | ±4.925 | 3.31 | ±1.277**† |

| IGF2R | 0.677 | ±0.048 | 0.553 | ±0.162 | 0.168 | ±0.059**† |

| Insulin | 0.001 | ±0.0002 | 0.001 | ±0.0003 | 0.0004 | ±0.0002 |

| IGF1 | 0.0002 | ±1E-05 | 0.001 | ±0.0001 | 0.0001 | ±3E-05 |

| IGF2 | 3.3E-5 | ±2.1E-5 | 5.0E-5 | ±2.2E-5 | 0.00 | ±0.00 |

| FRONTAL WHITE MATTER | ||||||

| INR | 0.006 | ±0.0004 | 0.001 | ±0.0003*** | 0.001 | ±0.0004*** |

| IGF1R | 43.5 | ±8.315 | 2.648 | ±0.291*** | 2.72 | ±0.842*** |

| IGF2R | 0.395 | ±0.009 | 0.324 | ±0.129 | 0.401 | ±0.127 |

| Insulin | 0.001 | ±7E-05 | 3E-05 | ±1E-05*** | 2E-05 | ±9E-06*** |

| IGF1 | 0.001 | ±0.0002 | 0.001 | ±0.0004 | 0.001 | ±0.0002 |

| IGF2 | 0.0002 | ±0.00001 | 3.7E-6 | ±9.6E-7*** | 7.2E-6 | ±5.2E-6*** |

| AMYGDALA | ||||||

| INR | 0.0134 | ±0.002 | 0.005 | ±0.001** | 0.004 | ±0.002** |

| IGF1R | 2.437 | ±0.477 | 30.43 | ±11.87** | 25.94 | ±7.56** |

| IGF2R | 0.527 | ±0.105 | 0.979 | ±0.241*** | 1.839 | ±0.622*** |

| Insulin | 0.017 | ±0.002 | 0.005 | ±0.003** | 0.003 | ±0.001** |

| IGF1 | 0.002 | ±0.0002 | 0.002 | ±0.001 | 0.002 | ±0.001 |

| IGF2 | 0.0002 | ±0.0001 | 0.0002 | ±0.0001 | 0.0004 | ±0.0002 |

| BASAL GANGLIA | ||||||

| INR | 0.0007 | ±0.0001 | 0.0004 | ±0.0002 | 0.001 | ±0.0002 |

| IGF1R | 0.7054 | ±0.0668 | 0.6963 | ±0.095 | 0.959 | ±0.210 |

| IGF2R | 0.0301 | ±0.0035 | 0.0867 | ±0.0301 | 0.229 | ±0.102* |

| Insulin | 8E-06 | ±3E-06 | 3E-06 | ±3E-06 | 4E-06 | ±2E-06 |

| IGF1 | 0.0004 | ±3E-05 | 0.0003 | ±8E-05 | 0.0005 | ±0.0001 |

| IGF2 | 0.000 | ±0.000 | 0.000 | ±0.000 | 0.000 | ±0.000 |

IN-insulin; IGF-insulin-like growth factor; R-receptor. Gene expression was measured by qRT-PCR analysis with values (×10−6) normalized to 18S rRNA measured in parallel reactions. Inter-group comparisons were made using repeated measures ANOVA with the post hoc Dunn's multiple comparison test.

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.005 relative to control;

P<0.05 or better relative to PD.

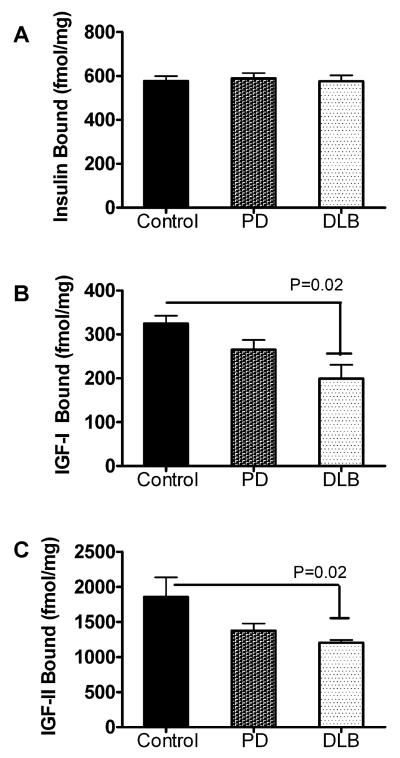

DLB is associated with impaired IGF-IR and IGF-IIR binding

Effective ligand binding is critical to insulin and IGF signaling cascades, such that many downstream effects of impaired insulin and IGF signaling have been reported in relation to human CNS diseases [31,32], and experimental in vivo and in vitro models [34,51,56]. Importantly, impairments in insulin/IGF receptor binding have been linked to reduced neuronal survival, energy production, glucose utilization, and acetylcholine homeostasis [56]. We performed equilibrium binding assays to determine if the alterations in IGF-I and IGFII receptor expression in the frontal cortex were associated with reduced ligand binding to those receptors. Competitive equilibrium binding studies demonstrated similar levels of specific insulin-R binding in control, PD, and DLB, but significantly reduced levels of IGF-IR and IGF-IIR binding in DLB relative to control frontal cortex (Fig. 1). The modest reductions in IGFIR, and IGF-IIR binding in PD did not reach statistical significance.

Fig. 1.

Impaired brain IGF receptor binding in DLB. Competitive equilibrium binding to insulin, IGF-I, and IGF-II receptors was measured in anterior frontal cortex of brains with normal aging (control), PD, or DLB. Membrane protein extracts were incubated with 50 pM [125I]-labeled insulin, IGF-I, or IGF-II as tracer, in the presence or absence of 100 nM cold ligand. Membrane bound tracer was precipitated and radioactivity associated with the pellets (bound ligand) or remaining in the supernatants (free ligand) was measured in a gamma counter. Specific binding (fmol/mg) was calculated using the GraphPad Prism 5 software. Graphs depict the mean ± S.E.M. of results obtained for (A) insulin, (B) IGF-I, and (C) IGF-II specific binding. Data were analyzed statistically using ANOVA with post hoc significance tests. Significant P-values are indicated over the bar graphs.

Altered neurotrophin and neurotrophin receptor gene expression in PD and DLB (Table 5)

Table 5.

Altered neurotrophin and neurotrophin receptor expression in PD and DLB frontal cortex

| mRNA | CONTROL | PD | DLB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TrkA | 0.372 | ±0.041 | 0.185 | ±0.055 | 0.058 | ±0.017*** |

| TrkB | 97.05 | ±15.36 | 108.3 | ±87.55 | 15.88 | ±5.794** |

| p75NGF | 3.749 | ±0.945 | 3.056 | ±0.785 | 3.15 | ±0.979 |

| BDNF | 32.28 | ±3.203 | 10.48 | ±3.094* | 22.79 | ±4.254 |

| NGF | 25.3 | ±5.394 | 2.47 | ±0.436*** | 6.63 | ±2.761** |

Trk-tyrosine kinase receptor; p75NGF-low affinity NGF receptor; BDNF-brain derived neurotrophic factor; NGF-nerve growth factor. Gene expression was measured by qRT-PCR analysis with values (×10−9) normalized to 18S rRNA measured in parallel reactions. Inter-group comparisons were made using repeated measures ANOVA with the post hoc Dunn's multiple comparison test.

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.005 relative to control;

P<0.05 or better relative to PD.

Altered expression of neurotrophins, including brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF), and their receptors, including TrkA and p75, has been reported in PD and DLB [57-59]. However, the potential relationship between altered neurotrophin or neurotrophin receptor expression and impairments in insulin/IGF signaling in neurodegenerative diseases has not yet been explored. To focus our investigations, we measured mRNA levels of the TrkA, TrkB, and p75 neurotrophin receptors, and NGF and BDNF neurotrophins in frontal cortex by qRT-PCR. Other neurotrophins and receptors, including TrkC, NT3, and NT4-5, were excluded because exploratory studies revealed minimal levels of these genes in control brains (data not shown). We detected reduced expression of TrkA (NGF receptor), TrkB (BDNF receptor), and NGF, but not p75 (low affinity NGF receptor) in DLB, significantly reduced expression of NGF and BDNF in PD.

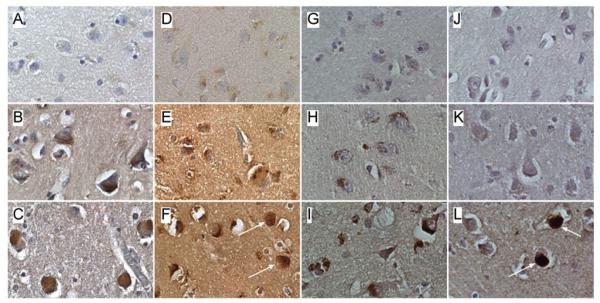

Protein studies of PD and DLB neurodegeneration

Levels of immunoreactivity corresponding to Hu, MAG-1, GAP-43, β-actin, HNE, ubiquitin, α-synuclein, and DβH were measured in frontal cortex by ELISA with Amplex Red fluorescence (Table 6). Corresponding with the qRT-PCR results, Hu and MAG-1 expression were significantly reduced in DLB relative to control. HNE, a marker of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress was significantly increased in DLB. In addition, the mean levels of α-synuclein and DβH were increased in both PD and DLB relative to control. No significant alterations in GAP-43, a marker of neuritic growth, ubiquitin, or β-actin, were observed in PD or DLB. Immunohistochemical staining studies confirmed the increased levels of DβH (Fig. 2A–2C), α-synuclein (Fig. 2D–2F), and HNE (Fig. 2G–2I) in DLB and PD relative to control frontal cortex. In addition, α-synuclein- and ubiquitin-positive Lewy body inclusions (Fig. 2F, 2L) were detected in DLB cortical neurons. Increased ubiquitin immunoreactivity was not detected in DLB samples by ELISA because the extraction methods employed would not have solubilized proteins integral to Lewy bodies.

Table 6.

Increased indices of neurodegeneration and oxidative stress in PD and DLB frontal cortex

| PROTEIN | CONTROL | PD | DLB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hu | 77164 | ±1974 | 76146 | ±3065 | 60308 | ±4672*** |

| MAG | 60823 | ±4366 | 46577 | ±4959 | 28859 | ±3793*** |

| β–actin | 75449 | ±1188 | 79048 | ±1282 | 76205 | ±1677 |

| GAP-43 | 43049 | ±3186 | 33536 | ±1795 | 35941 | ±3238 |

| α–synuclein | 11508 | ±1646 | 29642 | ±3501*** | 22384 | ±1657*** |

| DβH | 23254 | ±1122 | 32649 | ±2583* | 31563 | ±2031* |

| UBQ | 64742 | ±1871 | 65516 | ±2169 | 68132 | ±1229 |

| HNE | 46470 | ±3519 | 57480 | ±4809 | 60555 | ±1480* |

MAG-myelin-associated glycoprotein; GAP-43-growth associated protein-43; DβH-dopamine beta hydroxylase; UBQ-ubiquitin; HNE-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Immunoreactivity was measured in direct binding ELISAs using HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and Amplex Red soluble fluorophore. Values reflect arbitrary fluorescence light units (Ex 530 nm/Em 590 nm). Statistical comparisons were made using repeated measures ANOVA with the post hoc Dunn's multiple comparison test.

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.005 relative to control.

Fig. 2.

Patterns of DβH, α-synuclein, HNE, and ubiquitin immunoreactivity in control, PD, and DLB frontal cortex. Paraffin-embedded histological sections were immunostained to detect (A-C) DβH, (D-F) α-synuclein, (G-I) HNE, or (J-L) ubiquitin in (A,D,G,J) control, (B,E,H,K) PD, or (C,F,I,L) DLB frontal cortex. Immunoreactivity was detected with biotinylated secondary antibody, avidin-biotin horseradish peroxidase complex reagents, and diaminobenzidine as the chromagen (brown precipitate). Sections were lightly counter-stained with hematoxylin and preserved under coverglass. Globular (F) α-synuclein or (L) ubiquitin positive neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (arrows) distinguish DLB from PD and control. Increased DβH, α-synuclein, and HNE immunoreactivity distinguish DLB and PD from control.

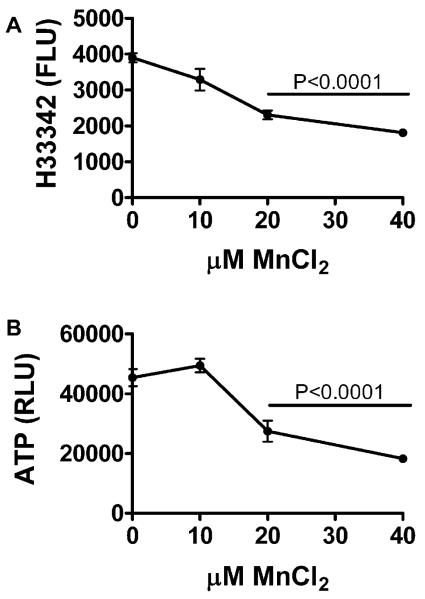

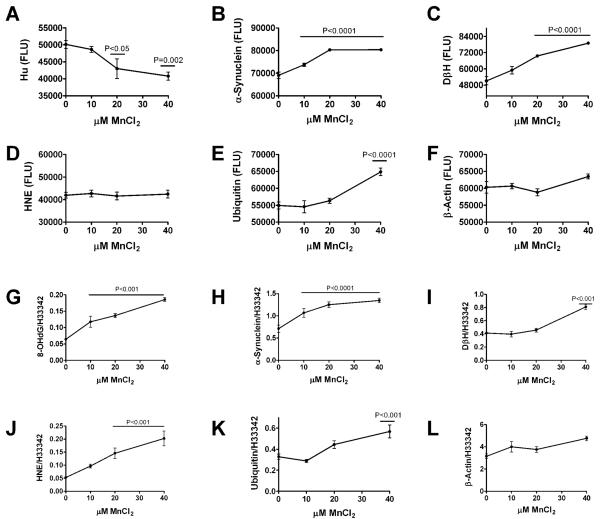

Manganese exposure produces molecular indices of PD/DLB neurodegeneration in vitro

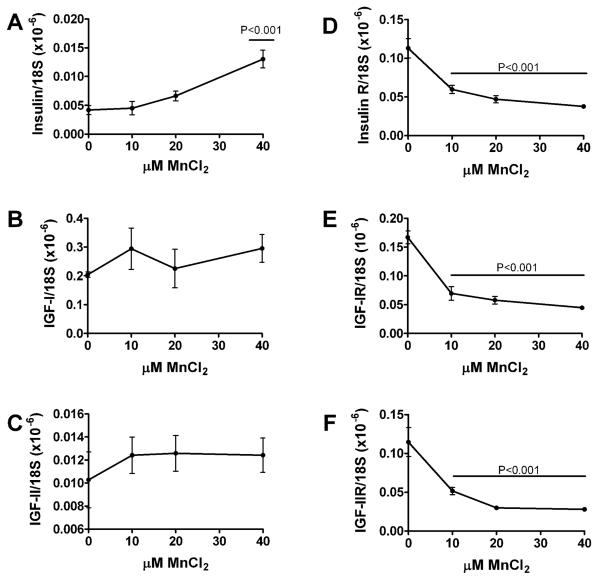

Primary cerebellar neuron cultures generated from rat pups were treated with 0–40 μM MnCl2 for 48 hours, and then analyzed for cell density, energy metabolism (ATP production), immunoreactivity, and insulin/IGF polypeptide and receptor expression. MnCl2 exposure caused dose-dependent reductions in cell density and ATP production such that at the highest dose used, both indices were approximately 50% lower than control (Fig. 3). Direct binding and cellular ELISAs were used respectively to measure immunore-activity in protein homogenates and directly in cultured neurons. MnCl2 treatment significantly reduced Hu neuronal expression, and increased α-synuclein, DβH, and ubiquitin immunoreactivity (Fig. 4). MnCl2 treatment also caused dose-dependent increases in 8-OHdG, an index of DNA damage that is increased in PD [60] (Fig. 4). β-actin was not significantly modulated by MnCl2 exposure. Finally, qRT-PCR studies demonstrated that increasing doses of MnCl2 treatment resulted in increased levels of insulin gene expression, but decreased levels of insulin receptor, IGF-I receptor, and IGF-II receptor expression (Fig. 5), reflecting insulin and IGF resistance.

Fig. 3.

Manganese exposure impairs neuronal viability, energy metabolism, and Hu neuronal gene expression in CNS neurons. Rat primary cerebellar neuron 96-well cultures were treated with 0, 10, 20, or 40 μM MnCl2 for 48 hours. (A) To measure cell density, cells were fixed, stained with Hoechst H33342, and fluorescence intensity (Ex340 nm/Em360 nm) was measured in a SpectraMax-5 microplate reader. (B) To measure energy metabolism, live cultures were analyzed using the ATPLite assay, and luminescence was quantified in a TopCount machine. (C) Hu immunoreactivity was measured by cellular ELISA using the Amplex Red soluble fluorophore. Graphs depict the mean ± S.E.M. fluorescent light units (FLU) or relative light units (RLU) measured in 12 replicate assays per MnCl2 dose. Results were analyzed using the Deming linear regression analysis. Significant trends are indicated within the panels.

Fig. 4.

Manganese exposure causes neurodegeneration and oxidative stress. Rat primary cerebellar neuron cultures were treated with 0, 10, 20, or 40 μM MnCl2 for 48 hours. Protein homogenates were used to measure (A) α-synuclein, (B) DβH, (C) HNE, (D) ubiquitin, or (E) β-actin by ELISA (see Methods). Immunoreactivity was also measured by cellular ELISA in 96-well cultures. Cells were fixed in situ, permeabilized, treated to prevent non-specific binding, and incubated with primary antibodies to detect (F) 8-OHdG, (G) α-synuclein, (H) DβH, (I) HNE, (J) ubiquitin, or (K) β-actin. Immunoreactivity was detected with horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody and Amplex Red fluorophore. Fluorescence light units (FLU) were measured in a SpectraMax-5 microplate reader (Ex 561 nm/EM 584 nm). For cellular ELISAs, immunoreactivity was normalized to Hoechst H33342 fluorescence. Graphs depict the mean ± S.E.M. levels of immunoreactivity as a function of MnCl2 dose. Trend lines were analyzed using the Deming linear regression model. P-values corresponding to trends significantly different from zero are shown in each panel.

Fig. 5.

Manganese exposure inhibits IGF-I and IGF-II receptor expression in primary CNS neuron cultures. Rat primary cerebellar neuron cultures were treated with 0, 10, 20, or 40 μM MnCl2 for 48 hours. RNA extracted from the cultured cells was reverse transcribed and used to measure (A) insulin, (C) IGF-II, (B) insulin receptor (R), (C) IGF-I, (D) IGF-IR, and (F) IGF-IIR by qRT-PCR analysis. The mRNA levels were normalized to 18S rRNA measured in the same samples. Graphs depict the mean ± S.E.M. relative levels of gene expression as a function of MnCl2 dose. Trend lines were analyzed using Deming linear regression. Significant P values are indicated in the panels.

DISCUSSION

Pathological shifts in gene expression corresponding to different brain cell populations in PD and DLB

The frontal lobe, amygdala, and basal ganglia are targets of neurodegeneration in PD and/or DLB. The studies herein provide evidence that PD and DLB are associated with significant neuronal loss in all three structures, based upon decreased levels of Hu mRNA, a neuronal-specific gene. The lower levels of Hu in DLB compared with PD correspond with the greater severity of neurodegeneration in DLB. Reduced levels of MAG-1 mRNA in DLB and PD frontal white matter reflect oligodendroglial loss, corresponding with an earlier finding of white matter atrophy in both diseases [61]. Loss of frontal white matter projecting fibers would interrupt circuitry between subcortical or brainstem nuclei and the frontal cortex. In addition to oligodendroglia degeneration, another potential cause of frontal white matter fiber degeneration in PD/DLB is neuronal loss in the amygdala, since fibers emanating from the basolateral nucleus project to the frontal cortex [62,63].

As expected, degeneration in cortex and white matter were accompanied by increased GFAP expression, i.e., gliosis. In DLB, the reduced levels of the vascular endothelial gene, ET-1, suggest that loss of vascular elements may contribute to neurodegeneration and dementia by compromising perfusion, nutrient supply, and energy metabolism. Finally, increased IBA-1 expression in PD and DLB is consistent with the concept that neuroinflammation mediates the PD/DLB neurode-generation cascade, similar to the findings in AD [31]. Altogether, these studies demonstrate that neurodegeneration in both PD and DLB results in loss of multiple cell types, including neurons, oligodendroglia, and endothelial cells, similar to the findings in AD [31]. Therefore, additional research is needed to understand the increased vulnerability of non-neuronal cell types in major neurodegenerative diseases. The relevance of this point is reinforced by the previous finding of white matter atrophy in the early stages of AD and DLB [64,65].

Altered expression of genes mediating insulin and IGF signaling in brain

The abnormalities gene expression that are directly pertinent to the integrity of insulin and IGF signaling in brain, overlapped with those observed in AD, but most importantly, were distinct. In contrast to AD [31,32], impairments in insulin and insulin receptor expression were confined to frontal white matter and amygdala and did not involve the frontal cortex in DLB or PD. On the other hand, DLB overlapped with AD with respect to the significant reductions in IGF-I and IGF-II receptor expression and receptor binding in frontal cortex. The absence of such abnormalities in PD is consistent with the minimal or absent cortical neurodegeneration, and further suggests that dementia in AD and DLB are mediated in part by impairments in cortical IGF signaling mechanisms. In PD and DLB white matter, both insulin and IGF-II mRNAs were reduced, while the IGFI and IGF-II receptor mRNAs were increased. Since insulin, IGF-1, and IGF-II signaling mechanisms overlap and cross-talk, the relative preservation of IGF-I mRNA vis-à-vis increased IGF-I and IGF-II receptor expression may have sufficed to sustain some aspects of neuro-cognitive function in DLB.

Further evidence of brain IGF resistance in DLB

The selective impairment of IGF-I and IGF-II receptor binding with preservation of insulin receptor binding distinguishes DLB from AD in which binding to all three receptors is reduced, but the abnormalities in insulin receptor binding dominate [31,32]. In PD, IGF-I and IGF-II receptor binding were intermediate between control and DLB, corresponding with the extent of neurodegeneration. IGF-I has a key role in neuronal survival, while IGF-II sustains mesenchymal elements, including astrocytes and vascular cells [66]. Therefore, in DLB, impaired IGF-I signaling caused by reduced ligand binding, could account for the significant losses in neurons and oligodendroglia, whereas impaired IGF-II signaling may reflect degeneration of vascular elements. Although IGF-II can stimulate neuronal survival and function by activating insulin or IGF-I signaling pathways [66], the finding of IGF-II resistance indicates that this potential secondary support measure deteriorates in DLB.

Role of neurotrophin resistance and deficiency

Neurotrophin and neurotrophin receptor abnormalities have been implicated in PD, DLB, and other neurodegenerative diseases [67,68]. For example, neurotrophin withdrawal may contribute to olfactory and neuropsychiatric dysfunction in PD and DLB [62]. The present study demonstrated significant reductions in TrkA and TrkB in DLB frontal cortex, and significant reductions in NGF in both DLB and PD. Since TrkA is the receptor for NGF and TrkB is the receptor for BDNF, the results suggest that DLB is associated with BDNF and NGF resistance and NGF deficiency in the frontal lobe. The absence of cortical neurotrophin receptor resistance in PD helps distinguish PD from DLB using molecular methods. On the other hand, the reduced NGF expression in both PD and DLB suggest that NGF withdrawal may be pivotal in the pathogenesis of both diseases. These results also suggest that from a molecular diagnostics approach, DLB and AD overlap with respect to neurotrophin receptor loss and resistance [67-69], but differ in that AD is not associated with cortical neurotrophin deficiency [70,71].

Correlates of neurodegeneration

We used ELISAs to measure HNE, ubiquitin, α-synuclein, and DβH immunoreactivity, with the expectation that this approach will aid in the eventual establishment of quantitative biochemical assays for distinguishing DLB from PD, and possibly AD. HNE immunoreactivity reflects lipid peroxidation with formation of cytotoxic aldehydes, and its levels are increased in various neurodegenerative diseases [72-74]. HNE covalently modifies and cross-links neuronal cytoskeletal proteins, forms pyrrole adducts with proteins, disrupts of neuronal calcium homeostasis, perturbs mitochondrial function, and promotes caspase-activated cell death [75]. The finding of increased HNE immunore-activity in the frontal cortex distinguishes DLB from PD, and links DLB-associated impairments in cognition and memory to chronic CNS oxidative stress. The finding of increased α-synuclein immunoreactivity in both PD and DLB frontal cortex, despite the absence of cortical Lewy bodies in PD, was unexpected. Since the protein extracts would not have dissolved Lewy bodies, which are composed of aggregated and ubiquitinated α-synuclein complexes, the increased levels of cortical α-synuclein immunoreactivity measured in PD and DLB most likely reflect increased levels of the soluble protein, consistent with the findings by immunohistochemical staining. Although DβH activity was previously shown to be reduced in PD cerebrospinal fluid [76], our finding of significantly increased cortical levels of DβH in both PD and DLB, as shown by ELISA and immunohistochemical staining, suggests a possible compensatory response to declining ability to convert dopamine to noradrenaline [77].

Potential role of neurotoxicants in the pathogenesis of PD/DLB

In vitro experiments showed that MnCl2 exposure impairs survival, energy metabolism, insulin, IGF-I and IGF-II receptor expression, reflecting insulin/IGF resistance, and it also increases α-synuclein, HNE, and DβH immunoreactivity in CNS neurons. These results overlap extensively with our findings with respect to PD/DLB, and strongly support the hypothesis that environmental neurotoxicants contribute to the pathogenesis of these diseases. Another point of novelty in this study was the direct comparison between the molecular and biochemical abnormalities associated with trophic factor deficiency, trophic factor receptor resistance, neurotransmitter dysfunction, and oxidative stress in PD and DLB, as well as in relation to an agent that is thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of sporadic PD/DLB. Further studies are needed to extend our understanding of the mechanisms by which transitional metals such as manganese and iron promote or exacerbate PD/DLB neurodegeneration.

Table 2.

Human primer pairs for quantitative RT-PCR

| mRNA | Sequence (5′→3′) | Position | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin | TTC TAC ACA CCC AAG TCC CGT C | 189 | 134 |

| ATC CAC AAT GCC ACG CTT CTG C | 322 | ||

| Insulin R | GGT AGA AAC CAT TAC TGG CTT CCT C | 1037 | 125 |

| CGT AGA GAG TGT AGT TCC CAT CCA C | 1161 | ||

| IGF-I | CAC TTC TTT CTA CAC AAC TCG GGC | 1032 | 147 |

| CGA CTT GCT GCT GCT TTT GAG | 1178 | ||

| IGF-I R | TAC TTG CTG CTG TTC CGA GTG G | 295 | 101 |

| AGG GCG TAG TTG TAG AAG AGT TTC C | 395 | ||

| IGF-II | CTG ATT GCT CTA CCC ACC CAA G | 996 | 76 |

| TTG CTC ACT TCC GAT TGC TGG C | 1071 | ||

| IGF-II R | CAC GAC TTG AAG ACA CGC ACT TAT C | 403 | 132 |

| GCT GCT CTG GAC TCT GTG ATT TG | 534 | ||

| IBA-1 | GCT GAG CTA TGA GCC AAA CC | 2 | 199 |

| TCG CCA TTT CCA TTA AGG TC | 200 | ||

| ET-1 | AGA GTG TGT CTA CTT CTG CCA CCT G | 517 | 144 |

| CAT CTA TTC TCA CGG TCT GTT GCC | 660 | ||

| MAG-1 | TGG AAG CCA ACA GTG AAC GG | 1128 | 104 |

| TTG AAG ATG GTG AGA ATA GGG TCC | 1231 | ||

| Hu | ATG GAG CCT CAG GTG TCA AAT G | 246 | 113 |

| TTG CTG TCA TCT GTG GTT GCC | 358 | ||

| GFAP | TAT GAG GCA ATG GCG TCC AG | 738 | 130 |

| AGT CGT TGG CTT CGT GCT TG | 867 | ||

| Trk1 | TCA TCT TCA CTG AGT TCC TGG AGC | 980 | 103 |

| AGC GTG TAG TTG CCG TTG TTG | 1082 | ||

| Trk2 | CGG GAA CAT CTC TCG GTC TAT G | 1282 | 185 |

| TTG CTG ATA ACG GAG GCT GG | 1466 | ||

| P75 | ACC TCA TCC CTG TCT ATT GCT CC | 862 | 78 |

| TCC ACC TCT TGA AGG CTA TGT AGG | 939 | ||

| NGF | ATA CAG GCG GAA CCA CAC TCA G | 46 | 174 |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by AA-11431, AA-12908 and K24 AA-15926, the Neuropathology Core of the Massachusetts ADRC, P50 AG005134, and the Bryan ADRC P50AG05128 from the National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health

REFERENCES

- 1.Jellinger KA. Recent developments in the pathology of Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2002:347–376. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6139-5_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKeith IG. Clinical Lewy body syndromes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;920:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurtig HI, Trojanowski JQ, Galvin J, Ewbank D, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Clark CM, Glosser G, Stern MB, Gollomp SM, Arnold SE. Alpha-synuclein cortical Lewy bodies correlate with dementia in Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 2000;54:1916–1921. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.10.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Hasegawa M, Goedert M. alpha-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6469–6473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma N, McLean PJ, Kawamata H, Irizarry MC, Hyman BT. Alpha-synuclein has an altered conformation and shows a tight intermolecular interaction with ubiquitin in Lewy bodies. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;102:329–334. doi: 10.1007/s004010100369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung KK, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. New insights into Parkinson's disease. J Neurol. 2003;250(Suppl 3):III15–24. doi: 10.1007/s00415-003-1304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang HQ, Takahashi R. Expanding insights on the involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress in Parkinson's disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:553–561. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ostrerova-Golts N, Petrucelli L, Hardy J, Lee JM, Farer M, Wolozin B. The A53T alpha-synuclein mutation increases iron-dependent aggregation and toxicity. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6048–6054. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06048.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mori H, Hattori N, Mizuno Y. Genotype-phenotype correlation: familial Parkinson disease. Neuropathology. 2003;23:90–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2003.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warner TT, Schapira AH. Genetic and environmental factors in the cause of Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2003;53(Suppl 3):S16–23. doi: 10.1002/ana.10487. discussion S23-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gasser T. Autosomal-dominantly inherited forms of Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2000:31–40. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6284-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hattori N. Parkin gene: its mutations and function. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2002;42:1077–1081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lansbury PT, Jr., Brice A. Genetics of Parkinson's disease and biochemical studies of implicated gene products. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsumine H. [A Parkin gene (PARK 2) and Parkinson's disease] Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 1999;39:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broussolle E, Thobois S. [Genetics and environmental factors of Parkinson disease] Rev Neurol (Paris) 2002;158(Spec no 1):S11–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hattori N, Mizuno Y. Pathogenetic mechanisms of parkin in Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2004;364:722–724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16901-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H. [Pathology of familial Parkinson's disease] Brain Nerve. 2007;59:851–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh M, Khan AJ, Shah PP, Shukla R, Khanna VK, Parmar D. Polymorphism in environment responsive genes and association with Parkinson disease. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;312:131–138. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9728-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Bohlen und Halbach O, Schober A, Krieglstein K. Genes, proteins, and neurotoxins involved in Parkinson's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;73:151–177. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu B, Gao HM, Hong JS. Parkinson's disease and exposure to infectious agents and pesticides and the occurrence of brain injuries: role of neuroinflammation. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1065–1073. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uversky VN. Neurotoxicant-induced animal models of Parkinson's disease: understanding the role of rotenone, maneb and paraquat in neurodegeneration. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:225–241. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0937-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ben-Shlomo Y. The epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. Baillieres Clin Neurol. 1997;6:55–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bower JH, Maraganore DM, Peterson BJ, McDonnell SK, Ahlskog JE, Rocca WA. Head trauma preceding PD: a case-control study. Neurology. 2003;60:1610–1615. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000068008.78394.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newell KL, Boyer P, Gomez-Tortosa E, Hobbs W, Hedley-Whyte ET, Vonsattel JP, Hyman BT. Alpha-synuclein immunoreactivity is present in axonal swellings in neuroaxonal dystrophy and acute traumatic brain injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:1263–1268. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199912000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butkovic-Soldo S, Tomic S, Stimac D, Knezevic L, Palic R, Juric S, Marijanovic K. Patients review: drug-induced movement disorders. Coll Antropol. 2005;29:579–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shirzadi AA, Ghaemi SN. Side effects of atypical antipsychotics: extrapyramidal symptoms and the metabolic syndrome. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2006;14:152–164. doi: 10.1080/10673220600748486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikeda K, Kashihara H, Tamura M, Kano O, Iwamoto K, Iwasaki Y. Body mass index and the risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2007;68:2156. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000269477.49238.ec. author reply 2156-2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen H, Zhang SM, Schwarzschild MA, Hernan MA, Willett WC, Ascherio A. Obesity and the risk of Parkinson's disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:547–555. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dulloo AG, Montani JP. Obesity in Parkinson's disease patients on electrotherapy: collateral damage, adiposity rebound or secular trends? Br J Nutr. 2005;93:417–419. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maswood N, Young J, Tilmont E, Zhang Z, Gash DM, Gerhardt GA, Grondin R, Roth GS, Mattison J, Lane MA, Carson RE, Cohen RM, Mouton PR, Quigley C, Mattson MP, Ingram DK. Caloric restriction increases neurotrophic factor levels and attenuates neurochemical and behavioral deficits in a primate model of Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U SA. 2004;101:18171–18176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405831102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rivera EJ, Goldin A, Fulmer N, Tavares R, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and function deteriorate with progression of Alzheimer's disease: link to brain reductions in acetylcholine. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;8:247–268. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steen E, Terry BM, Rivera EJ, Cannon JL, Neely TR, Tavares R, Xu XJ, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and signaling mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease-is this type 3 diabetes? J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7:63–80. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de la Monte SM, Tong M, Lester-Coll N, Plater M, Jr., Wands JR. Therapeutic rescue of neurodegeneration in experimental type 3 diabetes: relevance to Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;10:89–109. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lester-Coll N, Rivera EJ, Soscia SJ, Doiron K, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Intracerebral streptozotocin model of type 3 diabetes: relevance to sporadic Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:13–33. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Longo FM, Massa SM. Neurotrophin-based strategies for neuroprotection. J Alzheimers Dis. 2004;6:S13–17. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6s606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olson L, Backman L, Ebendal T, Eriksdotter-Jonhagen M, Hoffer B, Humpel C, Freedman R, Giacobini M, Meyerson B, Nordberg A, et al. Role of growth factors in degeneration and regeneration in the central nervous system; clinical experiences with NGF in Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases. J Neurol. 1994;242:S12–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00939233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unsicker K. Growth factors in Parkinson's disease. Prog Growth Factor Res. 1994;5:73–87. doi: 10.1016/0955-2235(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindsay RM, Altar CA, Cedarbaum JM, Hyman C, Wiegand SJ. The therapeutic potential of neurotrophic factors in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol. 1993;124:103–118. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Betarbet R, Sherer TB, Di Monte DA, Greenamyre JT. Mechanistic approaches to Parkinson's disease pathogenesis. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:499–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McMillan G. Is electric arc welding linked to manganism or Parkinson's disease? Toxicol Rev. 2005;24:237–257. doi: 10.2165/00139709-200524040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antunes MB, Bowler R, Doty RL. San Francisco/Oakland Bay Bridge Welder Study: olfactory function. Neurology. 2007;69:1278–1284. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000276988.50742.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dick FD, De Palma G, Ahmadi A, Osborne A, Scott NW, Prescott GJ, Bennett J, Semple S, Dick S, Mozzoni P, Haites N, Wettinger SB, Mutti A, Otelea M, Seaton A, Soderkvist P, Felice A. Gene-environment interactions in parkinsonism and Parkinson's disease: the Geoparkinson study. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64:673–680. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.032078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finkelstein MM, Jerrett M. A study of the relationships between Parkinson's disease and markers of traffic-derived and environmental manganese air pollution in two Canadian cities. Environ Res. 2007;104:420–432. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bowler RM, Roels HA, Nakagawa S, Drezgic M, Diamond E, Park R, Koller W, Bowler RP, Mergler D, Bouchard M, Smith D, Gwiazda R, Doty RL. Dose-effect relationships between manganese exposure and neurological, neuropsychological and pulmonary function in confined space bridge welders. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64:167–177. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.028761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodriguez-Agudelo Y, Riojas-Rodriguez H, Rios C, Rosas I, Sabido Pedraza E, Miranda J, Siebe C, Texcalac JL, Santos-Burgoa C. Motor alterations associated with exposure to manganese in the environment in Mexico. Sci Total Environ. 2006;368:542–556. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O'Brien JT, Feldman H, Cummings J, Duda JE, Lippa C, Perry EK, Aarsland D, Arai H, Ballard CG, Boeve B, Burn DJ, Costa D, Del Ser T, Dubois B, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Goetz CG, Gomez-Tortosa E, Halliday G, Hansen LA, Hardy J, Iwatsubo T, Kalaria RN, Kaufer D, Kenny RA, Korczyn A, Kosaka K, Lee VM, Lees A, Litvan I, Londos E, Lopez OL, Minoshima S, Mizuno Y, Molina JA, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Pasquier F, Perry RH, Schulz JB, Trojanowski JQ, Yamada M. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jellinger KA. Neuropathological aspects of Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease and frontotemporal dementia. Neurodegener Dis. 2008;5:118–121. doi: 10.1159/000113679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de la Monte SM, Jhaveri A, Maron BA, Wands JR. Nitric oxide synthase 3-mediated neurodegeneration after intracerebral gene delivery. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:272–283. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e318040cfa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen AC, Tong M, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor resistance with neurodegeneration in an adult chronic ethanol exposure model. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1558–1573. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de la Monte SM, Ganju N, Wands JR. Microtiter Immunocytochemical ELISA Assay: A Novel and Highly Sensitive Method of Quantifying Immunoreactivity. Biotecniques. 1999;26:1073–1076. doi: 10.2144/99266bm15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de la Monte SM, Xu XJ, Wands JR. Ethanol inhibits insulin expression and actions in the developing brain. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:1131–1145. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4571-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu JG, Fu SL, Zhang KH, Li Y, Yin L, Lu PH, Xu XM. Differential gene expression in neural stem cells and oligodendrocyte precursor cells: a cDNA microarray analysis. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:637–646. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumagai T, Kitagawa Y, Hirose G, Sakai K. Antibody recognition and RNA binding of a neuronal nuclear autoantigen associated with paraneoplastic neurological syndromes and small cell lung carcinoma. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;93:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Imai Y, Ibata I, Ito D, Ohsawa K, Kohsaka S. A novel gene iba1 in the major histocompatibility complex class III region encoding an EF hand protein expressed in a monocytic lineage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224:855–862. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ito D, Tanaka K, Suzuki S, Dembo T, Fukuuchi Y. Enhanced expression of Iba1, ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1, after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rat brain. Stroke. 2001;32:1208–1215. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.5.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soscia SJ, Tong M, Xu XJ, Cohen AC, Chu J, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Chronic gestational exposure to ethanol causes insulin and IGF resistance and impairs acetylcholine homeostasis in the brain. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2039–2056. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6208-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nagatsu T, Mogi M, Ichinose H, Togari A. Changes in cytokines and neurotrophins in Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2000:277–290. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6301-6_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Benisty S, Boissiere F, Faucheux B, Agid Y, Hirsch EC. trkB messenger RNA expression in normal human brain and in the substantia nigra of parkinsonian patients: an in situ hybridization study. Neuroscience. 1998;86:813–826. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nagatsu T, Sawada M. Inflammatory process in Parkinson's disease: role for cytokines. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:999–1016. doi: 10.2174/1381612053381620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sato S, Mizuno Y, Hattori N. Urinary 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine levels as a biomarker for progression of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2005;64:1081–1083. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000154597.24838.6B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de la Monte SM, Wells SE, Hedley-Whyte T, Growdon JH. Neuropathological distinction between Parkinson's dementia and Parkinson's plus Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1989;26:309–320. doi: 10.1002/ana.410260302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harding AJ, Stimson E, Henderson JM, Halliday GM. Clinical correlates of selective pathology in the amygdala of patients with Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2002;125:2431–2445. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Porrino LJ, Crane AM, Goldman-Rakic PS. Direct and indirect pathways from the amygdala to the frontal lobe in rhesus monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1981;198:121–136. doi: 10.1002/cne.901980111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de la Monte SM. Quantitation of cerebral atrophy in preclinical and end-stage Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1989;25:450–459. doi: 10.1002/ana.410250506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.de la Monte SM, Vonsattel JP, Richardson EP., Jr. Morphometric demonstration of atrophic changes in the cerebral cortex, white matter, and neostriatum in Huntington's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1988;47:516–525. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198809000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de la Monte SM, Wands JR. Review of insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression, signaling, and malfunction in the central nervous system: relevance to Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7:45–61. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dawbarn D, Allen SJ. Neurotrophins and neurodegeneration. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2003;29:211–230. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2003.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hock C, Heese K, Muller-Spahn F, Hulette C, Rosenberg C, Otten U. Decreased trkA neurotrophin receptor expression in the parietal cortex of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 1998;241:151–154. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Higgins GA, Mufson EJ. NGF receptor gene expression is decreased in the nucleus basalis in Alzheimer's disease. Exp Neurol. 1989;106:222–236. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(89)90155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Allen SJ, MacGowan SH, Treanor JJ, Feeney R, Wilcock GK, Dawbarn D. Normal beta-NGF content in Alzheimer's disease cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 1991;131:135–139. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90354-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murase K, Nabeshima T, Robitaille Y, Quirion R, Ogawa M, Hayashi K. NGF level of is not decreased in the serum, brain-spinal fluid, hippocampus, or parietal cortex of individuals with Alzheimer's disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;193:198–203. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Butterfield DA, Reed T, Perluigi M, De Marco C, Coccia R, Cini C, Sultana R. Elevated protein-bound levels of the lipid peroxidation product, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, in brain from persons with mild cognitive impairment. Neurosci Lett. 2006;397:170–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Volkel W, Sicilia T, Pahler A, Gsell W, Tatschner T, Jellinger K, Leblhuber F, Riederer P, Lutz WK, Gotz ME. Increased brain levels of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal glutathione conjugates in severe Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem Int. 2006;48:679–686. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zarkovic K. 4-hydroxynonenal and neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Aspects Med. 2003;24:293–303. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(03)00024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Camandola S, Poli G, Mattson MP. The lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxy-2,3-nonenal increases AP-1- binding activity through caspase activation in neurons. J Neurochem. 2000;74:159–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hurst JH, LeWitt PA, Burns RS, Foster NL, Lovenberg W. CSF dopamine-beta-hydroxylase activity in Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1985;35:565–568. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.4.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tong ZY, Kingsbury AE, Foster OJ. Up-regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA in a sub-population of A10 dopamine neurons in Parkinson's disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;79:45–54. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]