Abstract

Sharpin-deficient (Sharpincpdm) mutant mice develop a chronic eosinophilic dermatitis. To determine the efficacy of eosinophil-depletion in chronic inflammation, Sharpincpdm mice were treated with anti-IL5 antibodies. Mice treated with anti-IL5 had a 90% reduction of circulating eosinophils and a 50% decrease in cutaneous eosinophils after ten days compared to sham-treated littermates. Reducing the number of eosinophils resulted in increased severity of alopecia and erythema and a significant increase in epidermal thickness. Skin homogenates from mice treated with anti-IL5 had decreased mRNA expression of arylsulfatase B (Arsb), diamine oxidase (amiloride binding protein 1, also called histaminase) (Abp1), and Il10, which are mediators that eosinophils may release to quench inflammation. Skin homogenates from mice treated with anti-IL5 also had decreased mRNA expression of Il4, Il5, Ccl11, kit ligand (Kitl), and Tgfa; and increased mRNA expression of Tgfb1, Mmp12, and tenascin C (Tnc). In order to further decrease the accumulation of eosinophils, Sharpincpdm mice were crossed with IL5null mice. IL5−/−, Sharpincpdm/Sharpincpdm mice had a 98% reduction of circulating eosinophils and a 95% decrease in cutaneous eosinophils compared to IL5-sufficient Sharpincpdm mice. The severity of the lesions was similar between IL5-sufficient and IL5-deficient mice. Double mutant mice had a significant decrease in Abp1, and a significant increase in Tgfb1, Mmp12, and Tnc mRNA compared to controls. These data indicate that eosinophils are not essential for the development of dermatitis in Sharpincpdm mice and suggest that eosinophils have both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory roles in the skin of these mice.

Keywords: mice, eosinophils, atopic dermatitis, antibodies, interleukin-5

Introduction

Eosinophils have long been associated with allergic disease and are considered key effector cells in tissue damage and inflammation (1,2). Agents that decrease eosinophil production or prevent eosinophil accumulation at sites of inflammation have been proposed as potential therapeutic strategies. While some studies seemed to confirm the benefit of eliminating eosinophils from the allergic response (3–6), other experiments had disappointing or conflicting results (7–10). Experiments with Il5-transgenic mice suggested that an increased number of eosinophils may actually reduce signs of allergic airway disease, implicating therapies focused on their elimination as potentially causing more harm than benefit (11). Taken together, these and other experiments demonstrate that the effector functions of eosinophils are poorly understood, and much work remains to determine their role in the pathophysiology of allergic disease (12,13).

Atopic eczema is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by intense pruritus, erythematous papules, scaling, and thickening of the skin with lichenification and fibrosis (14). Eosinophils are present in both acute and chronic lesions, and the degree of eosinophilia correlates with the severity of spongiosis and epidermal hyperplasia (15). Laboratory mice are valuable models for dissecting the role of eosinophils in allergic inflammation, and several spontaneous and experimentally induced models of atopic eczema have been described (16,17). These animal models are often superior to in vitro models, in part due to confounding factors introduced with isolation of cells for evaluation (18). The Sharpin-deficient mouse (C57BL/KaLawRij-Sharpincpdm/RijSunJ; Sharpincpdm/Sharpincpdm homozygous mutant mice hereafter referred to as Sharpincpdm) develops a chronic dermatitis with accumulation of eosinophils in the dermis and epidermis, providing a naturally occurring model to study the role of eosinophils in the skin (19–21). The epidermis of Sharpincpdm mice is markedly thickened by orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and acanthosis. While eosinophils are the predominant inflammatory cell type, increased numbers of mast cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells are also present throughout the dermis, which is thickened by edema and fibrosis. The eosinophilic dermatitis of Sharpincpdm mice is suggestive of the accentuated TH2 response characteristic of allergic inflammation, and skin homogenates of Sharpincpdm mice were found to contain an increased concentration of TH2 cytokines IL5, IL13, and GM-CSF (22). Systemic treatment of the mice with recombinant IL12 abrogated the increased expression of IL5 in the skin, and resolved the dermatitis (22). Systemic treatment with IL12 reduced the degree of eosinophilia in mice with parasitic infection and the number of eosinophils in blood and sputum of asthma patients (23,24).

Interleukin 5 is a relatively eosinophil-specific cytokine that promotes the maturation of eosinophils in the bone marrow, sensitizes eosinophils to chemokines, and enhances the survival of eosinophils in tissues (25–27). Treatment of mice, guinea pigs, and nonhuman primates with experimentally-induced pulmonary allergic inflammation with IL5-neutralizing antibodies reduced the number of peripheral blood eosinophils and prevented the accumulation of eosinophils in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (28–32). Similar effects were achieved in asthma patients treated with humanized anti-IL5 antibodies (7,10,33,34). However, while the antibody treatments greatly reduced the eosinophilia in the blood and bronochoalveolar lavage fluid, only a partial reduction was achieved in the pulmonary tissues of mice and human patients (7,31). This may explain the limited clinical efficacy of anti-IL5 treatment in asthma (7). The effect of anti-IL5 therapy has also been assessed in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis (35). It caused a significant reduction of the number of eosinophils in the peripheral blood and the esophagus, and this was associated with improvement of the clinical symptoms. In contrast, treatment of atopic eczema patients with anti-IL5 antibodies had no clinical effect, in spite of a significant reduction of the number of circulating eosinophils (36). The antibody treatment also failed to affect the atopic patch test and accumulation of eosinophils in the skin. However, another study reported that prior administration of anti-IL5 antibodies reduced the accumulation of eosinophils in the skin following induction of a late phase allergic skin reaction (37). The antibody treatment did not affect the severity of the reaction, but the reduced number of eosinophils correlated with a reduced number of tenascin-positive fibroblasts. This suggested a role of eosinophils in tissue remodeling consistent with observations made in the lung (5,38).

The objectives of the experiments presented here were to determine if treatment with IL5-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies could deplete eosinophils from the chronic skin lesions of Sharpincpdm mice, and if such depletion of eosinophils would affect the clinical course of the dermatitis in these mice and parameters associated with remodeling. The mice were treated systemically with IL5-neutralizing antibodies and the effect on blood and tissue eosinophilia, clinical score and expression of markers of inflammation and tissue remodeling were determined. As an alternative approach, Sharpincpdm mice were crossed with IL5-deficient mice to produce double mutant mice.

Material and methods

Monoclonal rat anti-mouse IL5

Monoclonal rat anti-mouse IL5 (TRFK5) was generated from hybridoma cells in Gibco™ Hybridoma Serum-Free media (Invitrogen Co., Carlsbad, CA) with 10 μl/ml 100X Antibiotic Antimycotic Solution (Sigma-Aldrich Co, St. Louis, Mo) and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Antibody was isolated using an Immunopure® IgG Purification Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL), dialyzed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), concentrated by lyophilization, and re-dialyzed in PBS. The antibody solution was checked for endotoxin by an E-Toxate® Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Sigma-Aldrich). Endotoxin was removed using a Detoxi-Gel™ Endotoxin Removing column (Pierce). The final antibody solution was diluted to 1.5 mg/ml. Lyophilized rat IgG (ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora, OH) was reconstituted in PBS, checked for endotoxin, and diluted to 1.5 mg/ml in PBS for use as a control. The final concentration of endotoxin in both antibody solutions was less than 25 EU/ml.

Mice

All experiments involving mice were conducted in accordance with NIH guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals and were approved by the Purdue University Animal Care and Use Committee. A colony of C57BL/KaLawRij-Sharpincpdm/RijSunJ (Sharpincpdm) mice was maintained at Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN. Mice were housed in a conventional barrier facility at 21 ± 2 °C and 50 ± 20% relative humidity, in 86.25 in2 opaque conventional cages (Ancare Co., Bellmore, NY) with CareFRESH bedding (Absorption Co, Bellingham, WA), exposed to a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle, and allowed free access to water and LabDiet 5015 (Purina Mills Inc., Richmond, IN). Five pairs of 5-week-old gender-matched littermates were injected intraperitoneally three times with 0.2 ml (0.3mg) of anti-IL5 or non-specific rat IgG with 3 day intervals. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine with 10% xylazine at 3 days after the last antibody injection (10 days from the first injection) for blood collection and euthanized by cervical dislocation. The severity of alopecia and erythema was evaluated by a board-certified veterinary pathologist. Tissues were collected and processed as described below.

To create Sharpincpdm mice with genetic deletion of both Il5-alleles, Sharpincpdm mice were crossed with C57BL/6-Il5tm1Kopf mice (39), hereafter referred to as Il5−/− mice. Five female C57BL/6-Il5−/− Sharpincpdm (double mutant) and five female C57BL/6-Il5+/− Sharpincpdm mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were acclimated to the housing conditions at Purdue University for at least one week. Pairs of one female double mutant mouse and one female Sharpincpdm mouse at 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 weeks of age were anesthetized with ketamine with 10% xylazine for blood collection and euthanized by cervical dislocation. Tissues were collected and processed as described below.

Tissue collection and processing

Blood was collected from anesthetized mice in an EDTA coated tube and used to determine absolute leukocyte counts with a hemacytometer and differential leukocyte counts from microscopic examination of a modified Wright’s stained blood smear. Sections of skin at the junction of lesional and non-lesional skin from the dorsal and ventral midline were collected in 10% buffered formalin for routine processing and staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and toluidine blue. Sections were examined microscopically and the epidermal thickness and number of eosinophils and mast cells per mm2 of dermis determined with digital images and Adobe Photoshop® software (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA). The remaining skin was removed from the carcass, divided into left and right halves, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

RNA isolation and analysis

Skin samples collected from the left side of mice were homogenized in TRI-reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). Total RNA was isolated by standard TRI-reagent methods according to the manufacturer’s protocols and quantitated at 260 nm. RNA was analyzed by quantitative real time RT-PCR (qPCR) and custom eTags™ multiplex assays (ACLARA Biosciences, Mountain View, CA).

For qPCR, RNA was reverse transcribed for 1 hour at 42°C in 30 μL volumes containing 0.5 μg RNA, 2.8 U Recombinant RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitor, 400 U M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase, 6.0 μL M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase 5X buffer, 0.25 μg Oligo(dT) 15 Primer, and 0.5 mM of each nucleotide (Promega, Madison, WI) in a Peltier Thermal Cycler 200 (MJ Research/Bio-Rad Laboratories, Waltham, MA). The cDNA was analyzed with Assays on Demand Taqman® primer and probe sets following the manufacturer’s instructions using the 7300 Real Time PCR System and Sequence Detection Software v1.2.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Assays on Demand primers and probes included sets for Ccr3 (ID Mm00515543_s1), Mmp9 (ID Mm00442991_m1), Mmp12 (ID Mm00500554_m1), Mmp13 (ID Mm00439491_m1), and Tnc (ID Mm00495662_m1) (Applied Biosystems). The Ct values for each chemokine were normalized by subtracting the Ct values for the housekeeping gene β-actin (ID Mm00607939_s1). The difference in mRNA expression between mice was calculated with the difference in normalized Ct values (fold change = 2−ΔΔCt) (40)

IL5 protein analysis

Skin samples collected from the right side of the mice were homogenized in 2–4 ml PBS with 1 mM PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.2 trypsin-inhibitor units/ml of aprotinin (Sigma-Aldrich). The homogenized samples were centrifuged and the supernatant collected and stored at −80°C until analysis for cytokine concentration. Skin homogenates were analyzed for the presence IL5 with an ELISA kit (PharMingen, San Diego, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocols with an additional step before incubation with the secondary antibody to block endogenous avidin binding sites. Briefly, 100 μl of 1.7 μM avidin (Pierce) in PBS were added to each well and the plate incubated for 15 min at room temperature. The plate was washed 3 times with PBS, and 100 μl of 2 mM biotin (Pierce) in PBS was added to each well and the plate incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. The plate was washed 3 times with PBS and the manufacture’s directions for the ELISA kit continued with the addition of the secondary antibody. Total protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce). The concentration of IL5 in pg/ml was divided by the total protein concentration in mg/ml, and expressed as pg IL5/mg total protein.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences between means of experimental groups for numbers of eosinophils, epidermal thickness, expression of mRNA and protein concentration was determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test using Microsoft® Excel.

Results

Effect of IL5-depletion on blood and tissue eosinophilia

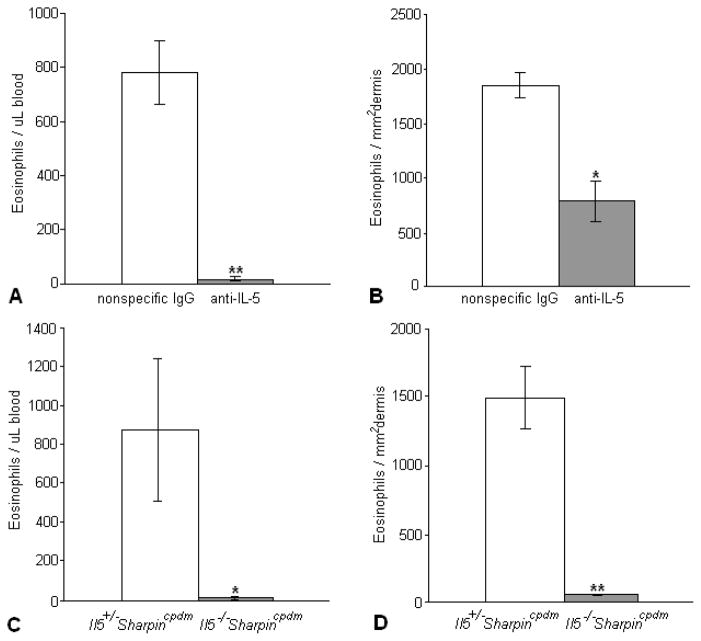

Treatment of 5-week-old Sharpincpdm mice with established dermatitis for 10 days with 3 injections of anti-IL5 antibodies reduced the percentage of eosinophils in peripheral blood by > 90% (Fig. 1A) and in the skin by about 50% (Fig. 1B). Monoclonal antibody treatment may not completely inhibit the biological activity of IL5. Therefore, Sharpincpdm mice were crossed with C57BL/6-Il5tm1Kopf mice to produce C57BL/6-Il5−/− Sharpincpdm mice completely lacking IL5 as confirmed by ELISA (not shown). The double mutant mice had a markedly reduced number of eosinophils in the peripheral blood (Fig. 1C) and skin (Fig. 1D) compared to the IL5-sufficient Sharpincpdm mice.

Figure 1.

The number of eosinophils in the blood (A) and skin (B) of Sharpincpdm mice treated with anti-IL-5 was significantly decreased compared to Sharpincpdm mice treated with a nonspecific rat IgG. Similar results were seen in the blood (C) and skin (D) of Il5−/−Sharpincpdm mice compared to Il5+/− Sharpincpdm mice. Data expressed as mean ± SEM for 5 mouse pairs. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005

Effect of IL5-depletion on the dermatitis in Sharpincpdm mice

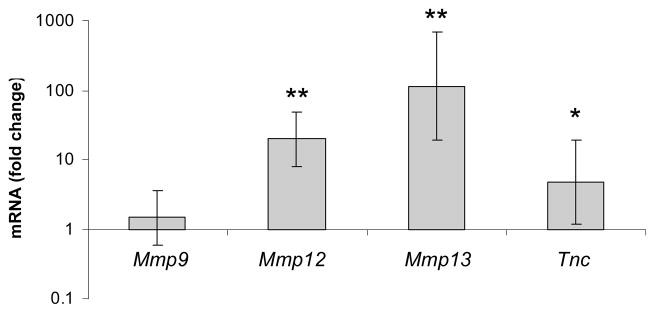

Anti-IL5 antibody treatment mildly enhanced the severity and distribution of erythema and alopecia observed grossly and significantly increased the thickness of the epidermis from 40.4 ± 2.5 μm to 46.8 ± 1.2 μm (P < 0.05) (Fig 2). There were no significant differences in the number of dermal mast cells or the overall severity of the inflammation.

Figure 2.

The epidermis was increased in thickness in Sharpincpdm mice treated with anti-IL-5 compared to Sharpincpdm littermates given non-specific IgG. Data expressed as mean ± SEM for 5 mouse pairs. *P < 0.05

Both IL5-sufficient and IL5-deficient Sharpincpdm mice developed dermatitis, but there was great variation in the severity of dermatitis within each group that was not age dependent. No consistent differences in severity were observed between the two groups, and no significant differences in epidermal thickness or number of mast cells were observed.

Effect of IL5 depletion on the expression of mediators of inflammation and remodeling

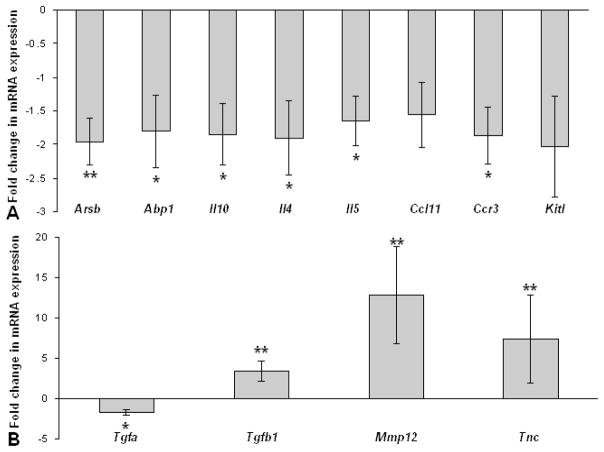

Metalloproteinases (MMPs) play an important role in remodeling of tissues during development and inflammation. The expression of Mmp9, Mmp12, and Mmp13 mRNA was analyzed in the affected skin of Sharpincpdm mice and compared with normal skin of control littermates. The expression of Mmp12, and Mmp13 mRNA, but not Mmp9 mRNA was markedly increased in the skin of Sharpincpdm mice (Fig. 3). Tenascin C is an extracellular matrix protein and changes in its expression are an indication of tissue remodeling. The expression of Tnc mRNA was modestly increased in the skin of Sharpincpdm mice (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Fold change in mRNA expression of Mmp9, Mmp12, Mmp13, and Tnc in the skin of Sharpincpdm mice (n=8) compared to control littermates (n=7). The bars represent the mean ± SD. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.001.

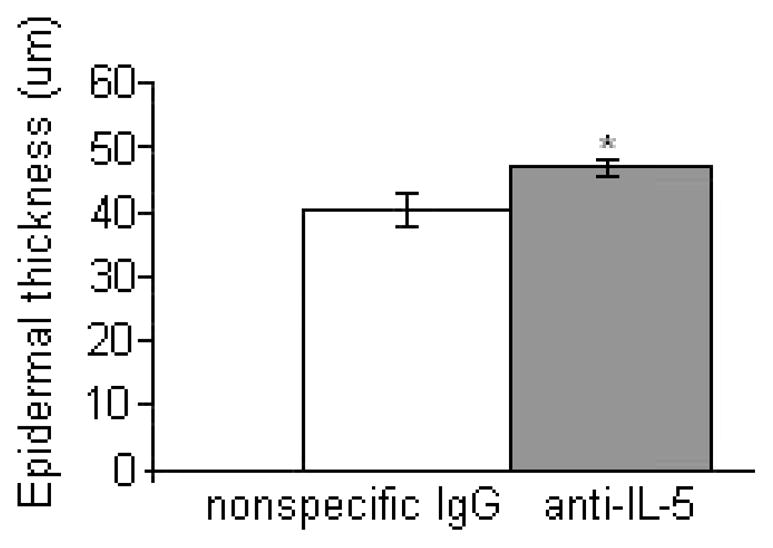

Consistent with the 50% reduction of eosinophils in the skin, there was approximately a 2-fold decrease of expression of mRNA encoding for CCR3 and the eosinophil-derived mediators arylsulfatase B and histaminase in the skin of mice treated with anti-IL5 antibodies (Fig. 4A). The expression of the cytokines Il10, Il4, and Il5 was also modestly decreased in the skin of mice injected with anti-IL5 antibodies (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the anti-IL5-treated mice had a significantly increased expression of Tgfb1, Mmp12 and Tnc mRNA (Fig. 4B). In spite of the marked variation in the severity of the dermatitis in the double mutant mice, decreased expression of Abp1 (P = 0.009) and increased expression of Tgfb1 (P = 0.005) and Mmp12 (P = 0.011) was also observed in the skin of IL5-deficient Sharpincpdm in comparison with IL5-sufficient mice (data not displayed graphically).

Figure 4.

Fold change in mRNA expression for Sharpincpdm mice treated with anti-IL5 compared to Sharpincpdm mice treated with non-specific rat IgG for mediators of inflammation (A) and remodeling (B). Data expressed as mean ± standard deviation for 5 mouse pairs. Data expressed as mean ± SD for 5 mouse pairs. * P < 0.05; **P < 0.005. (Abbreviations: Arsb=arylsufataseB, Apb1=histaminase,Ccl11=eotaxin, Kitl=kit ligand, Tgfa=transforming growth factor alpha, Tgfb1=transforming growth factor beta1, Mmp12=matrix metalloproteinase 12, Tnc=tenascin C).

Discussion

Treatment of Sharpincpdm mutant mice with anti-IL5 antibodies for 10 days significantly reduced the number of circulating and cutaneous eosinophils as compared to those treated with anti-rat IgG. The modest effect on eosinophils in the skin as compared to peripheral blood is similar to data of human lung tissue reported for treatment of patients with asthma (7,41). The decreased number of eosinophils was consistent with the diminished mRNA expression of Ccr3, as CCR3 is expressed primarily on eosinophils in mice (8,42). The regimen of monoclonal antibodies used in these experiments was 3 doses of 0.3 mg/mouse with 3 day intervals (total of 50 mg/kg). This dose is in the same range as used in humans (3–10 mg/kg), when calculated based on body surface area rather than body weight (43,44). This requires a factor of about 12 to obtain the equivalent dose in mice, i.e. 36 – 120 mg/kg (44).

The increase in distribution of alopecia and erythema observed in mice treated with anti-IL5 suggests that eosinophils have a role in limiting the inflammatory response. Potential mechanisms by which eosinophils exert their anti-inflammatory effect were suggested by the decrease in mRNA expression of the genes encoding arylsulfatase B and histaminase that occurred concurrently with the decrease in eosinophils. Arylsulfatase B and histaminase may inactivate leukotrienes and histamine released by mast cells (45,46), and thus a loss in their production could exacerbate clinical disease in allergy. Other studies have suggested that secretion of TGFb1 by eosinophils may dampen inflammation (11,47), but the depletion of eosinophils in the skin by anti-IL5 antibodies was associated with increased expression of TGFb1 in our experiments. IL10 is another immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory cytokine, and we did observe decreased expression of Il10 mRNA in anti-IL5-treated mice. Eosinophils can secrete IL10 which may dampen the allergic inflammatory response (48). A role of IL10 in the control of allergic immune responses is further supported by decreased IL10 secretion by peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with atopic dermatitis (49,50)

Studies have suggested that eosinophils are a source of fibrogenic factors and control downstream repair and remodeling processes (51). Indeed, the expression of Mmp12, Mmp13 and Tnc was increased in Sharpincpdm mice. MMP12 (metalloelastase) and MMP13 (collagenase-3) are proteolytic enzymes with a broad spectrum of extracellular matrix molecules as substrates. MMP12 is primarily associated with macrophages, and its expression is increased by exposure to GM-CSF, a cytokine that is overexpressed in the skin of Sharpincpdm mice (52). MMP13 is expressed by keratinocytes, and its expression is enhanced by TGFb1 and TNF and inhibited by IFNg (53). The markedly increased expression of Mmp13 seems consistent with the TH2-biased environment in the skin of the Sharpincpdm mice. The gelatinase MMP9 is expressed in mouse and human mast cells stimulated with TNFa (54). The expression of MMP9 was not increased in spite of the increased number of mast cells in the skin of Sharpincpdm mice, but consistent with the lack of increased TNFa in the skin (19,22). Tenascin C is a large extracellular matrix glycoprotein, and its expression is induced in patch tests in the skin of atopic individuals (37). The tenascin C-positive cells were identified morphologically as fibroblasts (37).A modest increase of Tnc was observed in the skin of Sharpincpdm mice. The mRNA expression of Mmp12 and Tnc was further increased in the skin of Sharpincpdm mice with reduced numbers of eosinophils. This is in contrast to a decreased number of tenascin C-positive cells in the airways and skin of patients treated with anti-IL5 (37,38) and suggests that eosinophils inhibit the remodeling process in the Sharpincpdm skin. While inhibiting the remodeling process, the decreased mRNA expression of Tgfa in the skin of Sharpincpdm mice with reduced numbers of eosinophils suggests that eosinophils do promote cellular proliferation to contribute to wound healing.

Although eosinophils were nearly completely absent from the skin of IL5-deficient Sharpincpdm mice, these mice did develop skin lesions indicating that the dermatitis in Sharpincpdm mice is not dependent on eosinophils. The variability in the severity and distribution of the skin lesions in the IL5-deficient Sharpincpdm mice was most likely caused by heterogeneity of the genetic background of the F2 crosses and may have masked changes that would support a role of eosinophils in controlling inflammation as suggested by the antibody treatment. An alternative explanation is that the lack of IL5 in the double mutant mice since the first stages of development may have caused other changes that are not induced by the short term deficiency following the monoclonal antibody treatment. Although the effects of IL5 on the development, maturation, priming and survival are fairly specific for eosinophils, other immunogical abnormalities, in particular a deficiency of B1 lymphocytes, have been observed in IL5-deficient mice (39). These changes may affect the inflammation in the Sharpincpdm mice.

In conclusion, treatment of mice with IL5-neutralizing antibodies resulted in a greatly reduced number of eosinophils in the peripheral blood, but a modest decrease (50%) in the skin of mice with chronic dermatitis. The pathogenesis of dermatitis in Sharpincpdmmice is not completely understood, but this study demonstrates that eosinophils are not necessary for the development of dermatitis in Sharpincpdmmice, and may have a role in reducing the severity and extent of the skin lesions. This study adds to the evidence that a key to therapy in allergic disease may not be in the elimination of eosinophils but instead in the modulation of eosinophil function to promote their anti-inflammatory effects (10,11).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the NIH (AR49288-01) and a Pfizer Graduate Research Assistantship. We thank B. Shirley and K. Silva, The Jackson Laboratory, ME, for generating and genotyping the C57BL/6-Il5−/− Sharpincpdm double mutant mice. We thank T. Hodam and L. Kraus, Pfizer Inc., St. Louis, MO, for their assistance in RNA collection and analysis with the eTags™ probe set.

References

- 1.Wardlaw AJ, Moqbel R, Kay AB. Eosinophils: Biology and role in disease. Adv Immunol. 1995;60:151–266. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60586-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothenberg ME, Hogan SP. The eosinophil. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:147–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foster PS, Hogan SP, Ramsay AJ, Matthaei KI, Young IG. Interleukin 5 deficiency abolishes eosinophilia, airway hyperreactivity, and lung damage in a mouse asthma model. J Exp Med. 1996;183:195–201. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Justice JP, Borchers MT, Crosby JR, et al. Ablation of eosinophils leads to a reduction of allergen-induced pulmonary pathology. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L169–L178. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00260.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humbles AA, Lloyd CM, McMillan SJ, et al. A critical role for eosinophils in allergic airways remodeling. Science. 2004;305:1776–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1100283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JJ, Dimina D, Macias MP, et al. Defining a link with asthma in mice congenitally deficient in eosinophils. Science. 2004;305:1773–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1099472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flood-Page PT, Menzies-Gow AN, Kay AB, Robinson DS. Eosinophil’s role remains uncertain as anti-interleukin-5 only partially depletes numbers in asthmatic airway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:199–204. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-789OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humbles AA, Lu B, Friend DS, et al. The murine CCR3 receptor regulates both the role of eosinophils and mast cells in allergen-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1479–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261462598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma W, Bryce PJ, Humbles AA, et al. CCR3 is essential for skin eosinophilia and airway hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of allergic skin inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:621–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI14097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leckie MJ, ten Brinke A, Khan J, et al. Effects of an interleukin-5 blocking monoclonal antibody on eosinophils, airway hyper-responsiveness, and the late asthmatic response. Lancet. 2000;356:2144–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi T, Iijima K, Kita H. Marked Airway Eosinophilia Prevents Development of Airway Hyper-responsiveness During an Allergic Response in IL-5 Transgenic Mice. J Immunol. 2003;170:5756–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bochner BS. Verdict in the case of therapies versus eosinophils: the jury is still out. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams TJ. The eosinophil enigma. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:507–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI21073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung DY. Atopic dermatitis: new insights and opportunities for therapeutic intervention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:860–76. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.106484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiehl P, Falkenberg K, Vogelbruch M, Kapp A. Tissue eosinophilia in acute and chronic atopic dermatitis: a morphometric approach using quantitative image analysis of immunostaining. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:720–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutermuth J, Ollert M, Ring J, Behrendt H, Jakob T. Mouse models of atopic eczema critically evaluated. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2004;135:262–76. doi: 10.1159/000082099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiohara T, Hayakawa J, Mizukawa Y. Animal models for atopic dermatitis: are they relevant to human disease? J Dermatol Sci. 2004;36:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schefzyk M, Bruder M, Schmiedl A, et al. Eosinophil granulocytes: functional differences of a new isolation kit compared to the isolation with anti-CD16-conjugated MicroBeads. Exp Dermatol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.HogenEsch H, Gijbels MJJ, Offerman E, Van Hooft J, Van Bekkum DW, Zurcher C. A spontaneous mutation characterized by chronic proliferative dermatitis in C57BL mice. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:972–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gijbels MJJ, Zurcher C, Kraal G, et al. Pathogenesis of skin lesions in mice with chronic proliferative dermatitis (cpdm/cpdm) Am J Pathol. 1996;148:941–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seymour RE, Hasham MG, Cox GA, et al. Spontaneous mutations in the mouse Sharpin gene result in multiorgan inflammation, immune system dysregulation and dermatitis. Genes Immun. 2007;8:416–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.HogenEsch H, Torregrosa SE, Boggess D, Sundberg BA, Carroll J, Sundberg JP. Increased expression of type 2 cytokines in chronic proliferative dermatitis (cpdm) mutant mice and resolution of inflammation following treatment with IL-12. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:734–42. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200103)31:3<734::aid-immu734>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finkelman FD, Madden KB, Cheever AW, et al. Effect of interleukin 12 on immune responses and host protection in mice infected with intestinal nematode parasites. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1563–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryan SA, O’Connor BJ, Matti S, et al. Effects of recombinant human interleukin-12 on eosinophils, airway hyper-responsiveness, and the late asthmatic response. Lancet. 2000;356:2149–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03497-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaguchi Y, Suda T, Suda J, et al. Purified interleukin 5 supports the terminal differentiation and proliferation of murine eosinophilic precursors. J Exp Med. 1988;167:43–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rothenberg ME, Petersen J, Stevens RL, et al. IL-5-dependent conversion of normodense human eosinophils to the hypodense phenotype uses 3T3 fibroblasts for enhanced viability, accelerated hypodensity, and sustained antibody-dependent cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 1989;143:2311–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stern M, Meagher L, Savill J, Haslett C. Apoptosis in human eosinophils. Programmed cell death in the eosinophil leads to phagocytosis by macrophages and is modulated by IL-5. J Immunol. 1992;148:3543–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gulbenkian AR, Egan RW, Fernandez X, et al. Interleukin-5 modulates eosinophil accumulation in allergic guinea pig lung. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:263–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.1.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mauser PJ, Pitman A, Witt A, et al. Inhibitory effect of the TRFK-5 anti-IL-5 antibody in a guinea pig model of asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1623–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.6_Pt_1.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Oosterhout AJ, Ladenius AR, Savelkoul HF, Van Ark I, Delsman KC, Nijkamp FP. Effect of anti-IL-5 and IL-5 on airway hyperreactivity and eosinophils in guinea pigs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:548–52. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.3.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kung TT, Stelts DM, Zurcher JA, et al. Involvement of IL-5 in a murine model of allergic pulmonary inflammation: prophylactic and therapeutic effect of an anti-IL-5 antibody. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:360–5. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.3.7654390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mauser PJ, Pitman AM, Fernandez X, et al. Effects of an antibody to interleukin-5 in a monkey model of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:467–72. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7633694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buttner C, Lun A, Splettstoesser T, Kunkel G, Renz H. Monoclonal anti-interleukin-5 treatment suppresses eosinophil but not T-cell functions. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:799–803. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00027302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flood-Page P, Swenson C, Faiferman I, et al. A study to evaluate safety and efficacy of mepolizumab in patients with moderate persistent asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1062–71. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-085OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stein ML, Collins MH, Villanueva JM, et al. Anti-IL-5 (mepolizumab) therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:1312–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oldhoff JM, Darsow U, Werfel T, et al. Anti-IL-5 recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody (mepolizumab) for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2005;60:693–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phipps S, Flood-Page P, Menzies-Gow A, Ong YE, Kay AB. Intravenous anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody reduces eosinophils and tenascin deposition in allergen-challenged human atopic skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:1406–12. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flood-Page P, Menzies-Gow A, Phipps S, et al. Anti-IL-5 treatment reduces deposition of ECM proteins in the bronchial subepithelial basement membrane of mild atopic asthmatics. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1029–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI17974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kopf M, Brombacher F, Hodgkin PD, et al. IL-5-deficient mice have a developmental defect in CD5+ B-1 cells and lack eosinophilia but have normal antibody and cytotoxic T cell responses. Immunity. 1996;4:15–24. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simon D, Braathen LR, Simon HU. Anti-interleukin-5 antibody therapy in eosinophilic diseases. Pathobiology. 2005;72:287–92. doi: 10.1159/000091326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grimaldi JC, Yu NX, Grunig G, et al. Depletion of eosinophils in mice through the use of antibodies specific for C-C chemokine receptor 3 (CCR3) J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:846–53. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.6.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pinkel D. The use of body surface area as a criterion of drug dosage in cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 1958;18:853–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reagan-Shaw S, Nihal M, Ahmad N. Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. FASEB J. 2008;22:659–61. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9574LSF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wasserman SI, Austen KF. Arylsulfatase B of human lung. Isolation, characterization, and interaction with slow-reacting substance of anaphylaxis. J Clin Invest. 1976;57:738–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI108332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herman JJ. Eosinophil diamine oxidase activity in acute inflammation in humans. Agents Actions. 1982;12:46–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01965105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cho JY, Miller M, Baek KJ, et al. Inhibition of airway remodeling in IL-5-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:551–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI19133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pretolani M. IL-10:A potential therapy for allergic inflammation? Imm Today. 1997;18:277–80. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)80023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunstan JA, Hale J, Breckler L, et al. Atopic dermatitis in young children is associated with impaired interleukin-10 and interferon-gamma responses to allergens, vaccines and colonizing skin and gut bacteria. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:1309–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seneviratne SL, Jones L, Bailey AS, Black AP, Ogg GS. Severe atopic dermatitis is associated with a reduced frequency of IL-10 producing allergen-specific CD4+ T cells. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:689–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kay AB, Phipps S, Robinson DS. A role for eosinophils in airway remodelling in asthma. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:477–82. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu L, Fan J, Matsumoto S, Watanabe T. Induction and regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-12 by cytokines and CD40 signaling in monocyte/macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;269:808–15. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ala-Aho R, Johansson N, Grenman R, Fusenig NE, Lopez-Otin C, Kahari VM. Inhibition of collagenase-3 (MMP-13) expression in transformed human keratinocytes by interferon-gamma is associated with activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1,2 and STAT1. Oncogene. 2000;19:248–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di GN, Indoh I, Jackson N, et al. Human mast cell-derived gelatinase B (matrix metalloproteinase-9) is regulated by inflammatory cytokines: role in cell migration. J Immunol. 2006;177:2638–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]