Abstract

Low dose metronomic (LDM) chemotherapy has shown promising activity in many preclinical and some phase II clinical trials involving various tumor types. To evaluate the potential therapeutic impact of LDM chemotherapy for ovarian cancer, we developed a preclinical model of advanced disease and tested various LDM chemotherapy regimens alone or in concurrent combination with an antiangiogenic drug, pazopanib. Clones of the SKOV-3 human ovarian carcinoma cell line expressing secretable β-subunit of human choriogonadotropic (β-hCG) protein and firefly luciferase were generated, and evaluated for growth after orthotopic (intraperitoneal) injection into SCID mice; a highly aggressive clone, SKOV-3-13, was selected for further study. Mice were treated beginning 10–14 days after injection of cells when evidence of carcinomatosis-like disease in the peritoneum was established as assessed by imaging analysis. Chemotherapy drugs tested for initial experiments included oral cyclophosphamide, injected irinotecan or paclitaxel alone or in doublet combinations with cyclophosphamide; the results indicated that LDM cyclophosphamide had no anti-tumor activity whereas LDM irinotecan had potent activity. We therefore tested an oral topoisomerase-1 inhibitor, oral topotecan at optimal biologic dose of 1mg/kg/daily. LDM oral topotecan showed excellent anti-tumor activity, the extent of which was significantly enhanced by concurrent pazopanib, which itself had only modest activity, with 100% survival values of the drug combination after six months of continuous therapy. In conclusion, oral topotecan may be an ideal agent to consider for clinical trial assessment of metronomic chemotherapy for ovarian cancer, especially when combined with an antiangiogenic VEGF-pathway targeting drug, such as pazopanib.

Keywords: Tumor xenografts, advanced disease, tumor angiogenesis, endothelial progenitor cells

Introduction

A chemotherapy dosing and scheduling strategy attracting growing interest is low-dose metronomic chemotherapy. It involves the close, regular administration of conventional chemotherapeutic drugs without prolonged drug-free ‘holidays’, over extended periods of time (1–3). In contrast to conventional, pulsatile maximum tolerated dose (MTD) chemotherapy, the main primary target, initially, of metronomic chemotherapy is thought to be the tumor’s neovasculature (1–3) though additional mechanisms are likely involved as well, e.g. stimulation of the immune system through reduction in regulatory T cells (4–6) and possibly direct tumor cell targeting effects (7). The antiangiogenic effects of low-dose continuous metronomic chemotherapy are thought to be mediated through several possible mechanisms including direct targeting of activated endothelial cells of angiogenic blood vessel capillaries (1, 2), and circulating bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells (CEPs) (8, 9). Some of the aforementioned cellular antiangiogenic effects may be mediated by systemic induction of angiogenesis inhibitors, e.g. thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) (10, 11). Another recently proposed mechanism is by targeting HIF-1 in the tumor cell population and hence their ability to induce angiogenesis by upregulating factors such as VEGF (12–14). Concurrent combination of metronomic chemotherapy with targeted biologic antiangiogenic agents such as anti-VEGFR-2 antibodies or small molecule receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (RTKIs) can sometimes cause surprisingly potent and sustained anti-tumor effects in preclinical models, accompanied by an absence of overt host toxicity even after chronic therapy (1, 2, 15).

Given the promising preclinical therapeutic results of a number of metronomic chemotherapy-based treatment studies, and the excellent safety profile of this treatment strategy, in addition to some early phase II clinical studies which have shown promising results (16), many subsequent metronomic chemotherapy trials have been initiated, a large proportion of which involve concurrent therapy with an antiangiogenic drug such as bevacizumab, sunitinib, or sorafenib, or other types of biologic agents, e.g. the hormonal antagonist letrozole (see www.clnicaltrials.gov under the heading of “metronomic chemotherapy”). The results of a limited number of such trials have been completed and published, with the most encouraging results thus far reported in patients with metastatic breast cancer (17, 18) and recurrent, advanced or metastatic ovarian cancer (19–22).

Regarding the various aforementioned ovarian cancer trials reported thus far, all have involved daily low-dose oral cyclophosphamide using a fixed dose of 50mg, combined with bevacizumab, administered at 10mg/kg every two weeks. However, because bevacizumab monotherapy is known to be active in advanced ovarian cancer (23–28), it is not clear whether the addition of the metronomic cyclophosphamide contributed meaningful additional activity to the observed clinical benefits in these trials. Even if it does, there may be better chemotherapy drugs for metronomic chemotherapy-based treatments of ovarian cancer. One obvious candidate to consider in this regard is oral topotecan.

Topotecan, a topoisomerase I inhibitor, is an approved drug used for the second line treatment of ovarian cancer patients whose tumors have become refractory to conventional first line therapy, e.g. paclitaxel plus platinum-based doublet chemotherapy (29–32). An oral version of topotecan has been approved (33) and thus, in theory, would be ideal for metronomic chemotherapy regimens involving prolonged daily therapy, similar to oral cyclophosphamide. Indeed there is some limited preclinical evidence showing superiority of daily oral low-dose topotecan compared with intermittent intravenously injected topotecan using a panel of human tumor xenograft models (34). Furthermore, anti-tumor activity in pediatric xenograft models of topotecan or irinotecan is enhanced by low-dose protracted schedules (see ref. (35)). Furthermore, another topoisomerase 1 inhibitor, irinotecan and gemcitabine, has been reported to be active when administered in a metronomic fashion in a preclinical model of human colorectal carcinoma xenografts (36) and lung carcinoma xenograft (37) and some preliminary clinical data also indicate metronomic irinotecan may be active in human colorectal carcinoma (38). Finally, (as reported in this paper) we recently found in preliminary studies that low-dose metronomic irinotecan administered intraperitoneally twice a week therapy was very active in an orthotopic model of human ovarian cancer, and moreover, this was associated with little toxicity, even after long-term treatment.

With the aforementioned information in mind, we decided to test the anti-tumor activity of oral topotecan alone in combination with other agents, in a new model of advanced orthotopic human ovarian cancer that we developed. The orthotopic model involves luciferase-tagged SKOV-3 ovarian carcinoma cells injected into the peritoneal cavity; treatment is initiated when the disease has been firmly established, as assessed by photon bioluminescence measurements – a methodology that was also used to assess the efficacy of the therapies tested. In addition to oral topotecan, we tested the oral antiangiogenic drug, pazopanib, which targets VEGF and PDGF receptors (39–41), alone and in combination with oral topotecan which therefore comprises an all oral combination treatment regimen. We also tested a number of other regimens, including an oral metronomic cyclophosphamide protocol administered through the drinking water known to be highly active in preclinical models of advanced metastatic breast and melanoma that we have previously developed (7, 42) as well as lymphomas (8). The rationale for testing anti-cancer treatment strategies, including metronomic chemotherapy, using models of more advanced disease is that the results may have greater relevance (i.e., predictive value) with respect to patients afflicted with the respective malignancies at an advanced stage of disease (7). Some preliminary support exists for this rationale based on a clinical trial study evaluating bevacizumab with daily oral metronomic cyclophosphamide and capecitabine (an oral 5-FU prodrug) in metastatic breast cancer (17); the use of this doublet metronomic chemotherapy regimen was based in part on extremely promising results testing oral metronomic UFT (tegafur plus uracil – another 5-FU prodrug) plus metronomic cyclophosphamide in a model of established high volume visceral metastatic breast cancer (7).

Here we report extremely encouraging anti-tumor results using daily low-dose metronomic oral topotecan, especially when combined with pazopanib. Moreover, the therapy could be maintained for half a year without any obvious toxic side effects.

Materials and Methods

Cells and reagents

The human ovarian cancer cell line SKOV-3 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was grown in RPMI 1640 (Hyclone, S. Logan, Utah) supplemented with 5 % fetal bovine serum in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C in 5 % CO2. SKOV-3 cells with stable expression of the beta subunit of human gonadrotropin (β-hCG) and firefly luciferase were generated sequentially, first by transfection of pIRES-hCG plasmid using lipofectamine (Life Technologies, Inc.) and selection in medium containing puromycin, and subsequently by pcDNA3.l-luciferase transfection also using lipofectamine and selection of positive clones in medium containing G418. The β-hCG protein is secreted and can be measured in the urine as a surrogate molecular marker of changes in systemic tumor burden (43, 44). Selected β-hCG and luciferase positive clones were injected i.p. into SCID mice and one of the clones (SKOV-3-13) was subsequently chosen for use in all of the experiments. The rationale for selecting the SKOV-3-13 clone is that it gave rise to greater levels of peritoneal carcinomatosis than the other clones we analyzed. We also evaluated other human ovarian cancer cell lines, e.g. Caov-3 and OVCAR-3, but almost none of the clones isolated from these cell lines developed a peritoneal carcinomatosis; furthermore, some clones that gave rise to peritoneal tumors were very slow growing making analysis of therapeutic outcomes impractical.

Experimental animals

Six-week old female CB-17 SCID mice (Charles River Canada) were housed in microisolator cages and vented racks and were manipulated using aseptic techniques. Procedures involving animals and their care were conducted in strict conformity with the animal care guidelines of Sunnybrook Health Science Centre and Canadian Council of Animal Care. For the advanced orthotopic tumor model, 3 million (5 million for preliminary experiment) β-hCG and luciferase tagged SKOV-3-13 cells were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) into CB-17 SCID mice. Two weeks later (10 days later for preliminary experiment) mice were separated into various groups equalized by assessment of urine β-hCG levels and treatment was initiated. For the subcutaneous transplant model, 3 million SKOV-3-13 cells were injected into right flank of CB17 SCID mice. Correlation between tumor size and urinary β-hCG level were evaluated when the tumor volumes reached approximately 100mm3. Tumor growth was monitored weekly by total body bioluminescence in the advanced orthotopic tumor model and by caliper measurement (volume=L÷2xw2) in the subcutaneous ectopic transplant model. Measurement of body weight weekly was used to evaluate toxicity. Toxicity was also evaluated by assessing peripheral blood white blood cell (WBC) counts at 7 days and 28 days after initiation of treatment. Mice were euthanized when showing 20% body weight loss or when moribund.

β-hCG measurements

Mouse urine was collected by placing mice in empty aerated tip boxes for 2 h as described previously (43, 44). Collected urine samples were stored at −70 °C until analyzed. Urine β-hCG levels were measured using a free-βhCG ELISA kit (Omega Diagnostics Ltd., Scotland, UK), and normalized by concomitant measurement of urine creatinine levels using QuantiChrom TM Creatinine assay kit (BioAssay System, CA, US), as follow the manufacture’s instructions.

Total body bioluminescence imaging

Mice were administered luciferin (150mg/kg), and fifteen minutes later they were imaged in an IVIS200 Xenogen under isofluorane anesthesia, as previously described (45). Luciferin stock solution (15mg/ml) was made up in PBS and keep frozen at −70 °C until use.

Analysis of circulating endothelial progenitor cells (CEPs)

Assessment of circulating endothelial progenitor cells (CEPs) used to determine the optimal biological dose (OBD) for metronomic chemotherapy was done as previously described (8, 9). Briefly, using four-color flow cytometry, CEPs were defined as CD45−, VEGFR-2+, CD117+, and CD13+. The absolute number of CEPs was calculated as the percentage of events collected in CEP enumeration gates multiplied by the total white blood cell (WBC) count.

Drugs and schedule

Cyclophosphamide (CTX) (Baxter Oncology GmbH, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), irinotecan (CPT-11) (Mayne Pharma Canada Inc., Montreal, Quebec, Canada), paclitaxel (PTX) (Bristol Mayer Squibb, Canada), cisplatin (CDDP) (Faulding Canada Inc., Montreal, Quebec, Canada) and topotecan (GlaxoSmithKline Inc., Montreal, Quebec, Canada) were purchased from the institutional pharmacy. Oral topotecan, pazopanib and the pazopanib vehicle, hydroxypropylmethyl cellulose (HPMC) were supplied by GlaxoSmithKline (Collegeville, PA, USA). These drugs were reconstituted as per manufacturer’s instructions.

Metronomic dosing and administration of cyclophosphamide (20 mg/kg/d) was given as described previously (46), i.e., daily through the drinking water, with an initial (upfront) and every 6 weeks bolus dose (100 mg/kg) i.p. administration of the drug. Low-dose metronomic (LDM) CPT-11 (10 mg/kg), LDM CDDP (1 mg/kg) were given twice a week by i.p. injection. LDM PTX (1 mg/kg) was given 3 times a week by i.p. injection. These doses were based on CEP analysis, as reported previously (7, 46). In other words the dose causing the nadir in CEP suppression, and showing no toxicity after one week of treatment, was used (9). Maximum tolerated dose (MTD) topotecan was given at 1.5 mg/kg 5 consecutive days every 3 weeks through i.p. injection. This MTD was based on the literature (47). For both oral topotecan and pazopanib, we evaluated the putative optimal biologic dose (OBD) by CEP analysis (as shown in figure 5). Oral topotecan was given at 1 mg/kg daily gavage and we used two doses for pazopanib, either 25 mg/kg given twice a day by gavage or 150 mg/kg once a day, by gavage.

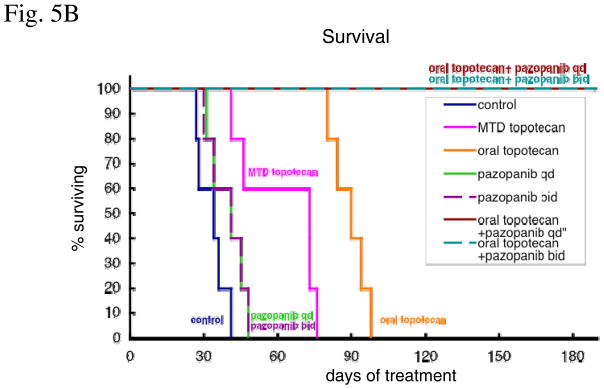

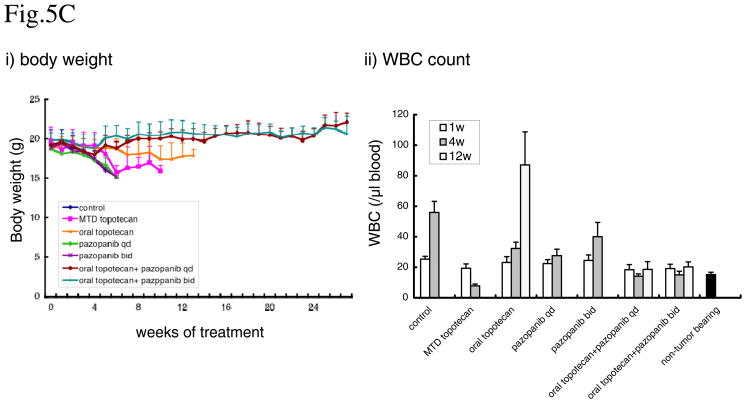

Figure 5. Effect of metronomic oral topotecan alone or in combination with pazopanib.

SKOV-3-13 human ovarian cancer cells were injected i.p. into CB-17 SCID mice. Treatments were initiated 14 days after tumor injection. The drug treatments and doses tested were: vehicle control, MTD topotecan (1.5mg/kg i.p. 5 consecutive days every 3 weeks), low-dose metronomic oral topotecan (1mg/kg by gavage, daily), once a day pazopanib (150mg/kg by gavage daily), twice a day pazopanib (25mg/kg by gavage), pazopanib once a day + oral topotecan and pazopanib twice a day + oral topotecan. Mice were euthanized when more than 20% body weight loss occurred or when moribund. (A) Mice were imaged every week and tumor growth bioluminescence. i) tumor growth curve,. ii) total body luminescence change over time. (B) Effect on survival. (C) Evaluate the toxicity. i) body weight, ii) WBC count. n=5, bars; +SD

Statistical analysis

Tumor therapy results are reported as the mean + SD. Survival curves were plotted by the method of Kaplan and Meier and tested for survival differences with the log-rank test. Statistical significance was assessed by the Student’s t test. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05 (in figures, ** < 0.01, and * < 0.05).

Results

Development of an orthotopic ovarian cancer xenograft model in mice for therapy testing

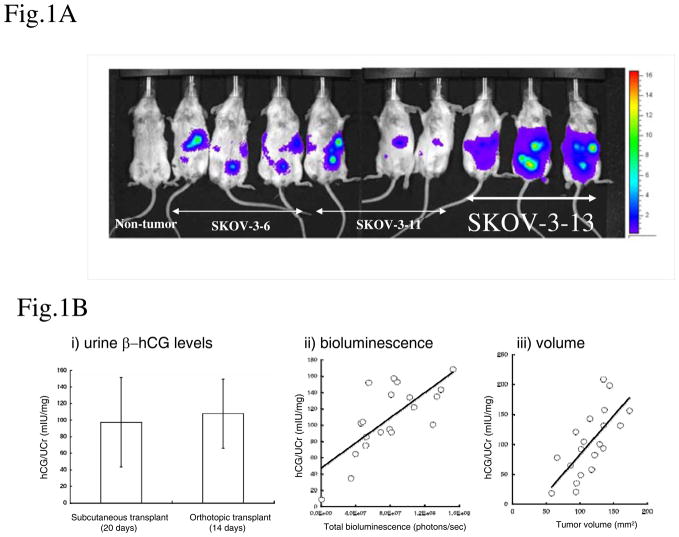

We established an ‘advanced’ orthotopic metastatic model of ovarian cancer with which to test various therapeutic regimens. To develop a model comprising a version of more advanced ovarian cancer, we orthotopically implanted SKOV-3 human ovarian cancer cells by i.p. injection, since direct intraperitoneal seeding is a common avenue of ovarian cancer metastasis (48–50). Cancer cells detach from primary tumor and spread throughout the peritoneal cavity, thus generating metastatic tumor deposits at the surfaces of peritoneal associated organs and the peritoneum. We used β-hCG and luciferase to monitor tumor burden by serial measurements of β-hCG in the urine, and by total body bioluminescence respectively. Selected β-hCG and luciferase positive clones were injected i.p. into SCID mice and one of the clones (SKOV-3-13) was subsequently chosen for use in all of the experiments, as it generated more peritoneal carcinomatosis than the other clones, and also grew more rapidly, with mice becoming moribund far earlier than observed with the other clones tested. Figure 1A illustrates the extent of tumor involvement of the peritoneal cavity/peritoneum by whole body bioluminescence, indicative of the more advanced nature of the disease at around the time treatments were to be initiated (10–14 days after i.p. injection). In addition, to confirm the correlation between tumor size and bioluminescence/urinary β-hCG we analyzed a conventional subcutaneous transplant model. SKOV-3-13 was implanted subcutaneously in the right flank and subsequent tumor growth was monitored by caliper measurements or by urinary β-hCG levels. When the tumor sizes reached about 100 mm3, we evaluated urinary β-hCG levels by ELISA. The level of urinary β-hCG (97.3±54.2 mIU/mg) at this point was similar to orthotopic model (107.8±41.9 mIU/mg) at the time of treatment initiation (Fig. 1B-i). To confirm the relationship between urinary β-hCG levels and tumor volumes, we plotted tumor volumes and urine β-hCG levels; a linear relationship was found between the two parameters (Fig. 1 B-iii). Urinary β-hCG and total body bioluminescence also showed a linear relationship (Fig. 1 B-ii).

Figure 1. Development of an advanced orthotopic model of ovarian cancer in mice.

(A) Clones of the SKOV-3 cell with stable expression of luciferase and β-hCG were injected intraperitoneally into CB-17 SCID mice as advanced orthotopic ovarian cancer model. Tumor growth was monitored by total bioluminescence image after luciferin administration. The most aggressive of these clones, SKOV-3-13, develops more peritoneal carcinomatosis and was subsequently chosen for use in all of the therapy experiments. (B) Correlation between the tumor measurement methods. i) urine β-hCG levels. Urine β-hCG levels were measured by ELISA and corrected by urine creatinine levels. When the subcutaneous tumor reached approximately 100mm3 urinary β-hCG levels (93±50 mIU/mg) were almost same as the orthotopic model the time of treatment initiation (104±43 mIU/mg). ii) Relationship between urinary β-hCG levels and bioluminescence (photons/sec) in the orthotopic transplant model, or iii) urinary β-hCG levels and tumor volume (mm3) in the subcutaneous transplant model. The solid line represents a simple linear regression between the two methods. Each dot represents an individual mouse.

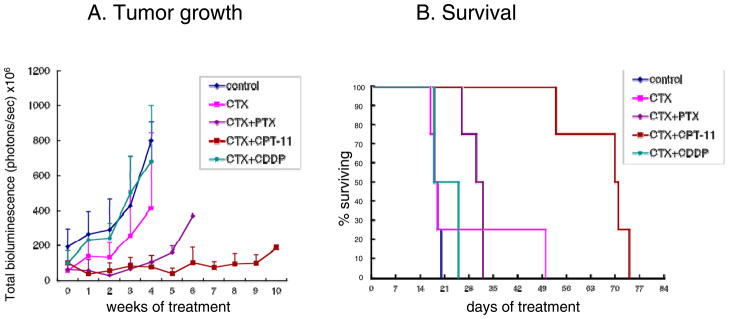

Preliminary assessment of combination metronomic chemotherapy regimens

We tested several monotherapy or combination metronomic chemotherapy regimens in the advanced orthotopic ovarian cancer model. We chose metronomic CTX as the primary ‘base’ treatment and combined it with other chemotherapy drugs (PTX, CDDP and CPT-11), all administered in a metronomic dosing fashion. CTX was chosen as the primary partner because of its frequent use in metronomic chemotherapy clinical trials, including ovarian cancer (see Introduction). The other chemotherapy drugs selected, PTX, CDDP, CPT-11 (and oral topotecan) are all used to treat ovarian cancer patients. SKOV-3-13 cells (5 million cells/mouse) were injected into the peritoneal cavity (n=4) and 10 days after injection the various treatments were initiated. Treatment with metronomic CTX alone and CTX+CDDP had no obvious antitumor effect. CTX+PTX caused a tumor growth delay which lasted approximately 4 weeks after initiation of treatment; at this point tumor growth resumed, resulting in a small survival benefit (Fig. 2a). The most effective combination tested was the CTX+CPT-11 doublet. Metronomic CTX+CPT-11 appears to cause significant tumor growth delays compared with the other drugs tested. Median survival values and p values of survival benefit were control (18 days), single agent CTX (18days, p=0.87), CTX+CDDP (18days, p=0.42), CTX+PTX (30 days, p<0.05=0.04) and CTX+CPT-11 (70 days, p<0.05=0.04) (Fig. 2b)

Figure 2. Preliminary assessment of combination metronomic chemotherapy regimens using cyclophosphamide (CTX).

(A) Tumor growth monitored by total bioluminescence: SKOV-3-13 human ovarian cancer cells were injected i.p. into CB17 SCID mice; 10 days after tumor injection, the various treatments were initiated, including vehicle control, 100 mg/kg bolus CTX i.p. followed by 20 mg/kg cyclophosphamide daily administered through the drinking water, and combinations of metronomic CTX+ PTX 1mg/kg three times a week i.p., CTX+CPT-11 10 mg/kg twice a week i.p. and CTX+CDDP 1 mg/kg twice a week i.p. Mice were imaging every week and tumor growth was monitored by total body bioluminescence. (B) Survival curve: mice were euthanized when body weight loss exceeded 15% or mice became moribund, and assessed; n=4, bars; +SD

Effect of metronomic cyclophosphamide alone or in combination with irinotecan for the treatment using the orthotopic advanced ovarian cancer xenograft model

Based on our preliminary results, we chose metronomic CTX plus metronomic CPT-11 chemotherapy to assess treatment efficacy in a comparative manner. We assessed tumor growth and survival in four different therapy groups: vehicle control, low dose metronomic (LDM) CTX, LDM CPT-11 and the doublet combination of LDM CTX and CPT-11. In this experiment we modified orthotopic ovarian cancer xenograft model to create more time before the mice reached the end point, and also to ensure firmly established peritoneal tumor was present at the time therapy was initiated. Thus we injected 3 million cells, and treatment was initiated two weeks after tumor cell inoculation. As shown in Figure 3a, single agent metronomic CTX did not have any obvious anti-tumor effect. Thus, the impact on survival was not significant when comparing the control group versus single agent metronomic CTX. In contrast, single agent metronomic CPT-11 caused a significant tumor growth delay and prolongation of survival. However, there was no difference between single agent CPT-11 and CPT-11+CTX, not only with respect to tumor growth but also survival. Moreover, the combination treatment group was notable for increase in toxicity. After a second injection of MTD cyclophosphamide, combination treatment mice showed body weight loss and some had to be sacrificed because of excessive body weight loss. Median survivals and the p values were as follows: control (36 days), CTX (45 days, p=0.34), CPT-11 (79 days, p<0.01=0.0026), CTX+CPT-11 (83 days, p<0.01=0.0026). Thus metronomic CTX did not appear to have any additive effect on the CPT-11-induced benefit in the orthotopic model (Fig 3b). In summary, metronomic CTX did not have activity when tested in the advanced stage ovarian cancer model we developed.

Figure 3. Effect of metronomic cyclophosphamide alone or in combination with irinotecan.

SKOV-3-13 human ovarian cancer cells were injected i.p. into CB17 SCID mice. 14 days after tumor injection, treatment was initiated and tumor growth was monitored by total body bioluminescence. The groups were: vehicle control, 100 mg/kg initial CTX treatment, and every 6 weeks bolus CTX i.p. followed by 20 mg/kg/d CTX through the drinking water, CPT-11 10 mg/kg twice a week i.p. and combination CTX+CPT-11. (A) Tumor growth. (B) Effect on survival. Mice were euthanized when more than 20% body weight loss occurred or when moribund and then assessed. n=8, bars; +SD

Impact of metronomic oral topotecan alone or in combination with the oral antiangiogenic agent, pazopanib

Given the encouraging results of the low dose metronomic CPT-11 protocol, we decided to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of an oral topoisomerase inhibitor, oral topotecan, for its efficacy in the advanced ovarian cancer xenograft model we developed. We also tested metronomic oral topotecan in combination with the oral small molecule antiangiogenic agent, pazopanib, as a possible all oral combination treatment. Before the various therapies were tested, we first estimated the optimal biological dose (OBD) for both drugs. In this regard, we have previously reported that levels of bone marrow-derived circulating endothelial cells (CEPs) can be used as a biomarker to monitor various targeted antiangiogenic drug activity as well as for estimating the OBD; this approach can be used for metronomic chemotherapy as well (7, 9). Using this approach we determined the OBD for oral topotecan administered by gavage on a daily basis. As shown in figure 4a, oral topotecan significantly decreased CEP levels at 1 mg/kg to 2mg/kg daily dose after both 7 days and 28 days of continuous treatment. We also evaluated the OBD for pazopanib using twice a day or once a day daily gavage schedules, because of its very short half-life. Based on our observations (Fig. 4B) which showed only a trend in reduction of CEP levels we chose the 25 mg/kg dose administered twice a day and 150 mg/kg dose once a day schedules. Interestingly, these doses and schedules are not inconsistent with previously published information regarding optimal anti-tumor xenograft activity in several models based on empirical drug testing in vivo (41). Mice did not show any side effects with either drug at any dose we used, at least for the 28 day schedule we used. Based on these results we estimated the OBD of oral topotecan is in the 1 mg/kg range and pazopanib is in the 25mg/kg range (for the twice a day schedule, or bid) and 150 mg/kg (for the once a day schedule, or qd).

Figure 4. CEP analysis to determine the optimal biologic dose of oral topotecan and pazopanib.

Normal Balb/c mice were treated with oral topotecan or pazopanib. Doses used were 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 mg/kg/d daily gavage for oral topotecan, 0,10, 25,50,100 mg/kg twice a day, by gavage, and 0, 50, 100, 120, 150 mg/kg once a day, by gavage for pazopanib. CEP analysis was performed after 7 or 28 days of treatment.

The treatments groups were as follows: vehicle control, MTD topotecan, 25 mg/kg bid pazopanib, 150 mg/kg qd pazopanib, oral topotecan, oral topotecan plus 25mg/kg bid pazopanib and oral topotecan plus 150 mg/kg qd pazopanib. As shown in figure 5A and B, single agent oral topotecan showed significant tumor growth delay and survival benefit whereas the other single agent therapies tested did not. The median survival value of mice in the control group was 34 days after start of treatment compared with 73 days (p<0.05=0.014) for the MTD topotecan group, 41 days (p=0.19) for 25mg/kg pazopanib group, 41 days (p=0.19) for 150 mg/kg pazopanib group, 90 days (p<0.01=0.0075) for oral topotecan group, and all of the mice in the oral topotecan/pazopanib combination treatment groups were still alive 180 days (p<0.01=0.0025) after initiation of treatment. Pazopanib provided a significant added beneficial effect with oral metronomic topotecan at both 25mg/kg twice a day and 150 mg/kg once a day schedule (Fig. 5B), although we noted the gradual, slow emergence of relapsing tumors in the 25mg/kg twice a day pazopanib plus oral topotecan group after a little over 5 months of therapy (Fig. 5B). We also evaluated the toxicity of these treatments by body weight loss and WBC counts. Mice showed body weight loss when they became moribund by tumor growth, but decreases in the body weight were not observed as a result of the treatments (Fig. 5C-i). Peripheral blood WBC counts were increased by tumor growth, but decreases in the WBC counts lower than non-tumor bearing mice level were observed in only the MTD topotecan group, after 4 weeks of treatment. (Fig. 5C-ii)

Discussion

This study represents the latest in a series of investigations in which models of advanced disease involving human tumor xenografts grown in immune deficient mice are developed for use in testing of particular anti-cancer treatment strategies. The cancer treatments we have been studying mainly consist of low-dose metronomic chemotherapy generally in ‘doublet’ combinations of two different chemotherapy drugs (7, 42) or a single chemotherapy drug combined with a targeted biologic agent, usually an antiangiogenic drug (2) or other types of targeted agents such as trastuzumab (44). In this case the focus of our studies has been ovarian cancer. Whereas the other advanced disease models we have developed involve establishment of visceral metastases in multiple organ sites such as the lungs or liver after surgical resection of primary orthotopic transplanted variant tumors previously selected for aggressive spontaneous metastasis, e.g. breast cancer or melanoma (7, 42), here we employed intraperitoneal injection of an established line of human ovarian carcinoma cells (SKOV-3) ‘tagged’ with markers to serially monitor disease burden over time. The rationale for this orthotopic approach was based on ovarian cancer often spreading within the peritoneal cavity, but not necessarily outside this location. Our reasoning is that if a particular therapy induces potent anti-tumor effect in this more therapeutically demanding and clinically relevant situation, it will likely have a greater probability of showing some kind of meaningful clinical benefit when used to treat patients with advanced disease of the same type of cancer (7, 17), and is similar in approach to that adopted by Landen et al (51) and Thaker et al (52) in previous studies.

With the aforementioned rationale in mind, the most compelling results we observed was with daily low-dose metronomic oral topotecan, especially when administered concurrently with daily oral pazopanib, the VEGF and PDGF receptor targeting oral antiangiogenic RTKI. Topotecan is already approved for the second line treatment of ovarian cancer, but is usually given intravenously at maximum tolerated doses on an intermittent basis, and thus is associated with several toxic side effects such as myelosuppression, fatigue and diarrhea (29–33). An oral formulation of the drug taken in an out-patient basis at low non or minimally toxic doses would therefore be a considerable advantage if associated with significant anti-tumor efficacy. It is important to note that while we only studied one cell line/model, similar therapeutic results utilizing metronomic oral topotecan plus pazopanib in other models of human ovarian cancer xenografts using different cell lines have been obtained concurrently and independently, e.g. as reported in the accompanying paper by Merritt et al. (53). This increases the prospect that this treatment regimen may indeed have promising activity for treating advanced ovarian cancer. In this regard, given the known clinical activity reported for bevacizumab monotherapy in ovarian cancer (24–28), it will be of interest to evaluate low-dose oral metronomic topotecan in combination with this antiangiogenic agent. We would note that bevacizumab has shown anti-tumor activity in our ovarian cancer model as a single agent, comparable to pazopanib, but combining the oral metronomic CTX protocol we used with bevacizumab did not improve the extent of this benefit (data not shown).

An interesting aspect of topotecan as an anti-cancer drug, especially when administered in a low-dose metronomic manner, is its suppressive effect on expression of tumor cell HIF-1, as first described by Melillo and his colleagues (12). A similar effect has been described by Semenza and colleagues using low-dose doxorubicin (13). There is considerable interest in HIF-1 as a therapeutic target in oncology because of its central role in regulating a broad spectrum of genes involved in tumor angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis (54). Thus exposure of tumor cells to topotecan can result in suppressed expression of VEGF likely as a result of HIF-1 downregulation (12). From this perspective metronomic topotecan therapy may be ideal to combine with an effective and chronic antiangiogenic drug (14) therapy which would normally be expected to increase tumor hypoxia and thus possibly act as a potential driving force for both HIF-1 mediated acquired resistance to the antiangiogenic drug by inducing alternate pathways of angiogenesis (55) and/or promoting increased invasion or metastasis (56). The ability of low-dose metronomic oral topotecan to suppress proangiogenic bone marrow derived cells, as reported here, is another way in which it may suppress tumor angiogenesis, and this could conceivably be related to an effect on HIF-1 (13), though this has yet to be determined.

Another interesting aspect of our results is the gradual appearance of tumors in the 25mg/kg twice/day pazopanib plus oral topotecan treated mice after over 5 months of continuous therapy. These relapsing tumors are now being analyzed for resistance to one or both of the drugs to which they were exposed.

Finally we would note that we failed to detect anti-tumor effects of low-dose metronomic cyclophosphamide in our model of advanced ovarian cancer whether as a monotherapy or when combined with other various agents. Bearing in mind that this is only one model, the results reinforce the possibility that the anti-tumor efficacy results of phase II trials of bevacizumab plus metronomic cyclophosphamide may have been mainly or entirely due to the bevacizumab treatment. Only an appropriate randomized trial would provide a definite answer to this question.

In summary, based on our results and independently those of Merritt et al (53), low-dose metronomic oral topotecan chemotherapy may be a promising clinical treatment to consider for testing in advanced ovarian cancer patients, especially when combined with a VEGF-pathway inhibiting drug such as pazopanib or bevacizumab. It will be of interest to evaluate such treatment combinations in preclinical models of recurrent drug resistant (e.g. paclitaxel/platinum resistant) and advanced ovarian cancer xenografts.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the excellent secretarial assistance of Ms. Cassandra Cheng, and colleagues in the Kerbel laboratory and at GSK, as well as Dr. Giovanni Mellilo and Dr. Gordon Rustin for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants to RSK from the National Institutes of Health, (NIH), USA (CA-41233), the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (CCSRI), and a sponsored research agreement with GlaxoSmithKline, Collegeville, PA. RSK is a Canada Research Chair in Tumor Biology, Angiogenesis and Antiangiogenic Therapy.

References

- 1.Browder T, Butterfield CE, Kraling BM, Marshall B, O’Reilly MS, Folkman J. Antiangiogenic scheduling of chemotherapy improves efficacy against experimental drug-resistant cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1878–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klement G, Baruchel S, Rak J, Man S, Clark K, Hicklin D, et al. Continuous low-dose therapy with vinblastine and VEGF receptor-2 antibody induces sustained tumor regression without overt toxicity. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:R15–R24. doi: 10.1172/JCI8829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerbel RS, Kamen BA. Antiangiogenic basis of low-dose metronomic chemotherapy. Nature Rev Cancer. 2004;4:423–36. doi: 10.1038/nrc1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wada S, Yoshimura K, Hipkiss EL, Harris TJ, Yen HR, Goldberg MV, et al. Cyclophosphamide augments antitumor immunity: studies in an autochthonous prostate cancer model. Cancer Res. 2009;69 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4102. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghiringhelli F, Larmonier N, Schmitt E, Parcellier A, Cathelin D, Garrido C, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress tumor immunity but are sensitive to cyclophosphamide which allows immunotherapy of established tumors to be curative. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:336–44. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghiringhelli F, Menard C, Puig PE, Ladoire S, Roux S, Martin F, et al. Metronomic cyclophosphamide regimen selectively depletes CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells and restores T and NK effector functions in end stage cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:641–8. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0225-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munoz R, Man S, Shaked Y, Lee C, Wong J, Francia G, et al. Highly efficacious non-toxic treatment for advanced metastatic breast cancer using combination UFT-cyclophosphamide metronomic chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3386–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertolini F, Paul S, Mancuso P, Monestiroli S, Gobbi A, Shaked Y, et al. Maximum tolerable dose and low-dose metronomic chemotherapy have opposite effects on the mobilization and viability of circulating endothelial progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4342–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaked Y, Emmengger U, Man S, Cervi D, Bertolini F, Ben-David Y, et al. The optimal biological dose of metronomic chemotherapy regimens is associated with maximum antiangiogenic activity. Blood. 2005;106:3058–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bocci G, Francia G, Man S, Lawler J, Kerbel RS. Thrombospondin-1, a mediator of the antiangiogenic effects of low-dose metronomic chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12917–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135406100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamano Y, Sugimoto H, Soubasakos MA, Kieran M, Olsen BR, Lawler J, et al. Thrombospondin-1 associated with tumor microenvironment contributes to low-dose cyclophosphamide-mediated endothelial cell apoptosis and tumor growth suppression. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1570–4. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rapisarda A, Zalek J, Hollingshead M, Braunschweig T, Uranchimeg B, Bonomi CA, et al. Schedule-dependent inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha protein accumulation, angiogenesis, and tumor growth by topotecan in U251-HRE glioblastoma xenografts. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6845–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee K, Qian DZ, Rey S, Wei H, Liu JO, Semenza GL. Anthracycline chemotherapy inhibits HIF-1 transcriptional activity and tumor-induced mobilization of circulating angiogenic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2353–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812801106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 14.Rapisarda A, Hollingshead M, Uranchimeg B, Bonomi CA, Borgel SD, Carter JP, et al. Increased antitumor activity of bevacizumab in combination with hypoxia inducible factor-1 inhibition. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1867–77. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pietras K, Hanahan D. A multitargeted, metronomic, and maximum-tolerated dose “chemo-switch” regimen is antiangiogenic, producing objective responses and survival benefit in a mouse model of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:939–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colleoni M, Rocca A, Sandri MT, Zorzino L, Masci G, Nole F, et al. Low dose oral methotrexate and cyclophosphamide in metastatic breast cancer: antitumor activity and correlation with vascular endothelial growth factor levels. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:73–80. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dellapasqua S, Bertolini F, Bagnardi V, Campagnoli E, Scarano E, Torrisi R, et al. Metronomic cyclophosphamide and capecitabine combined with bevacizumab in advanced breast cancer: clinical and biological activity. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4899–905. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.4789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bottini A, Generali D, Brizzi MP, Fox SB, Bersiga A, Bonardi S, et al. Randomized phase II trial of letrozole and letrozole plus low-dose metronomic oral cyclophosphamide as primary systemic treatment in elderly breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3623–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia AA, Hirte H, Fleming G, Yang D, Tsao-Wei DD, Roman L, et al. Phase II clinical trial of bevacizumab and low dose metronomic oral cyclophosphamide in recurrent ovarian cancer. A trial of the California, Chicago and Princess Margaret Hospital Phase II Consortia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;26:76–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chura JC, Van IK, Downs LS, Jr, Carson LF, Judson PL. Bevacizumab plus cyclophosphamide in heavily pretreated patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107:326–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jurado JM, Sanchez A, Pajares B, Perez E, Alonso L, Alba E. Combined oral cyclophosphamide and bevacizumab in heavily pre-treated ovarian cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2008;10:583–6. doi: 10.1007/s12094-008-0254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schultheis AM, Lurje G, Rhodes KE, Zhang W, Yang D, Garcia AA, et al. Polymorphisms and clinical outcome in recurrent ovarian cancer treated with cyclophosphamide and bevacizumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7554–63. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burger RA, Sill MW, Monk BJ, Greer BE, Sorosky JI. Phase II trial of bevacizumab in persistent or recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer or primary peritoneal cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5165–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaye SB. Bevacizumab for the treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer: will this be its finest hour? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5150–2. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.6150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burger RA. Experience with bevacizumab in the management of epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2902–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cannistra SA, Matulonis UA, Penson RT, Hambleton J, Dupont J, Mackey H, et al. Phase II study of bevacizumab in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer or peritoneal serous cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5180–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monk BJ, Choi DC, Pugmire G, Burger RA. Activity of bevacizumab (rhuMAB VEGF) in advanced refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:902–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Numnum TM, Rocconi RP, Whitworth J, Barnes MN. The use of bevacizumab to palliate symptomatic ascites in patients with refractory ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:425–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gore M, Oza A, Rustin G, Malfetano J, Calvert H, Clarke-Pearson D, et al. A randomised trial of oral versus intravenous topotecan in patients with relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armstrong DK. Topotecan dosing guidelines in ovarian cancer: reduction and management of hematologic toxicity. Oncologist. 2004;9:33–42. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-1-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wethington SL, Wright JD, Herzog TJ. Key role of topoisomerase I inhibitors in the treatment of recurrent and refractory epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008;8:819–31. doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.5.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sehouli J, Oskay-Ozcelik G. Current role and future aspects of topotecan in relapsed ovarian cancer. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:639–51. doi: 10.1185/03007990802707139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Brien ME, Ciuleanu TE, Tsekov H, Shparyk Y, Cucevia B, Juhasz G, et al. Phase III trial comparing supportive care alone with supportive care with oral topotecan in patients with relapsed small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5441–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De CM, Zunino F, Pace S, Pisano C, Pratesi G. Efficacy and toxicity profile of oral topotecan in a panel of human tumour xenografts. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1558–64. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Galindo C, Crews KR, Stewart CF, Furman W, Panetta JC, Daw NC, et al. Phase I study of the combination of topotecan and irinotecan in children with refractory solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57:15–24. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bocci G, Falcone A, Fioravanti A, Orlandi P, Di Paolo A, Fanelli G, et al. Antiangiogenic and anticolorectal cancer effects of metronomic irinotecan chemotherapy alone and in combination with semaxinib. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1619–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petrangolini G, Pratesi G, De Cesare M, Supino R, Pisano C, Marcellini M, et al. Antiangiogenic effects of the novel camptothecin ST1481 (gimatecan) in human tumor xenografts. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:863–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allegrini G, Falcone A, Fioravanti A, Barletta MT, Orlandi P, Loupakis F, et al. A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study on metronomic irinotecan in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1312–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sternberg CN, Szczylic C, Lee E, Salman PV, Mardiak J, Davis ID, et al. A randomized, double-blind phase III study of pazopanib in treatment-naive and cytokine-pretreated patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 abstract no. 5021. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sleijfer S, Ray-Coquard I, Papai Z, Le CA, Scurr M, Schoffski P, et al. Pazopanib, a multikinase angiogenesis inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory advanced soft tissue sarcoma: a phase II study from the European organisation for research and treatment of cancer-soft tissue and bone sarcoma group (EORTC study 62043) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3126–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar R, Knick VB, Rudolph SK, Johnson JH, Crosby RM, Crouthamel MC, et al. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic correlation from mouse to human with pazopanib, a multikinase angiogenesis inhibitor with potent antitumor and antiangiogenic activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2012–21. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cruz-Munoz W, Man S, Xu P, Kerbel RS. Development of a preclinical model of spontaneous human melanoma CNS metastasis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4500–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shih IM, Torrance C, Sokoll LJ, Chan DW, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Assessing tumors in living animals through measurement of urinary beta-human chorionic gonadotropin. Nature Medicine. 2000;6:711–4. doi: 10.1038/76299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Francia G, Emmenegger U, Lee CR, Shaked Y, Folkins C, Mossoba M, et al. Long term progression and therapeutic response of visceral metastatic disease non-invasively monitored in mouse urine using beta-hCG choriogonadotropin secreting tumor cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3452–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jenkins DE, Hornig YS, Oei Y, Dusich J, Purchio T. Bioluminescent human breast cancer cell lines that permit rapid and sensitive in vivo detection of mammary tumors and multiple metastases in immune deficient mice. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R444–R454. doi: 10.1186/bcr1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shaked Y, Emmenegger U, Francia G, Chen L, Lee CR, Man S, et al. Low-dose metronomic combined with intermittent bolus-dose cyclophosphamide is an effective long-term chemotherapy treatment strategy. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7045–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hammond LA, Hilsenbeck SG, Eckhardt SG, Marty J, Mangold G, MacDonald JR, et al. Enhanced antitumour activity of 6-hydroxymethylacylfulvene in combination with topotecan or paclitaxel in the MV522 lung carcinoma xenograft model. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:2430–6. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cannistra SA. Cancer of the ovary. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1550–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311183292108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Auersperg N, Wong AS, Choi KC, Kang SK, Leung PC. Ovarian surface epithelium: biology, endocrinology, and pathology. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:255–88. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cannistra SA, Kansas GS, Niloff J, DeFranzo B, Kim Y, Ottensmeier C. Binding of ovarian cancer cells to peritoneal mesothelium in vitro is partly mediated by CD44H. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3830–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Landen CN, Jr, Lu C, Han LY, Coffman KT, Bruckheimer E, Halder J, et al. Efficacy and antivascular effects of EphA2 reduction with an agonistic antibody in ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1558–70. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thaker PH, Han LY, Kamat AA, Arevalo JM, Takahashi R, Lu C, et al. Chronic stress promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a mouse model of ovarian carcinoma. Nature Medicine. 2006;12:939–44. doi: 10.1038/nm1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merritt WM, Nick AM, Carroll AR, Matsuo K, Dumble M, Jennings N, et al. Bridging the gap between cytotoxic and biologic therapy with metronomic topotecan and pazopanib in ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009 doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0967. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–32. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Casanovas O, Hicklin D, Bergers G, Hanahan D. Drug resistance by evasion of antiangiogenic targeting of VEGF signaling in late stage pancreatic islet tumors. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paez-Ribes M, Allen E, Hudock J, Takeda T, Okuyama H, Vinals F, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy elicits malignant progression of tumors to increased local invasion and distant metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:220–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]