Abstract

Five new steroidal imidazoles, amaranzoles B–F, were isolated from extracts of the marine sponge Phorbas amaranthus along with the known amaranzole A. The C24-N-(4-p-hydroxyphenyl) imidazol-5-yl constitution found in amaranzoles A, C and D is replaced by a C24-O-(4-p-hydroxyphenyl)imidazole-2-carboxylate motif in amaranzoles B, E and F. The structures were elucidated by interpretation of spectroscopic data. The C24 side chain configuration was assigned by synthesis of a model ester followed by chiroptical comparisons of its CD spectrum with that of an amaranzole B derivative.

Introduction

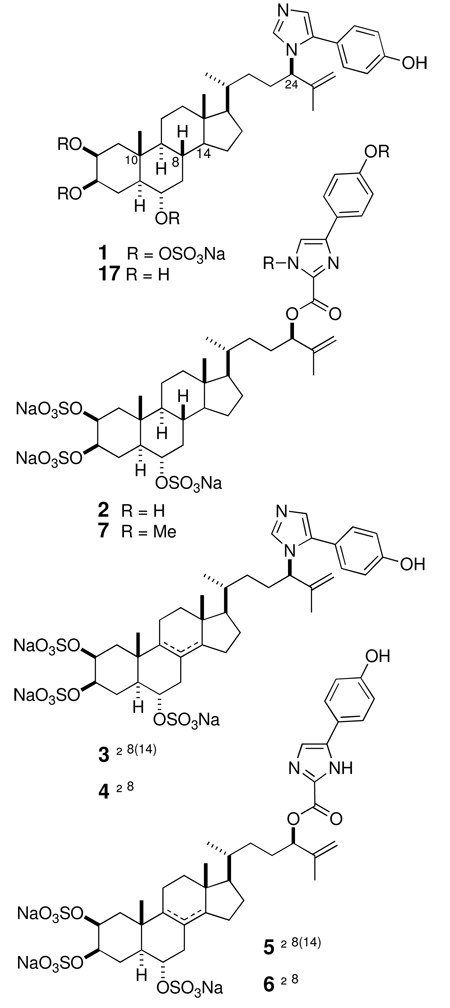

Extracts of the marine sponge Phorbas amaranthus were highly deterrent in feeding assays using the bluehead wrasse, Thalassoma bifasciatum.i In the course of investigations to identify the antifeedant constituents from P. amaranthus, we previously reported the ring-A contracted steroids, phorbasterones A–Dii and an unusual N-imidazolyl sterol, amaranzole A (1).iii Partial fractionation of extracts of P. amaranthus and interpretation of results of bioassay-guided separations, using laboratory and field fish feeding assays, pointed to the aqueous MeOH extracts of P. amaranthus as the location of the feeding deterrent components. Scarcity of material necessitated recollection of larger amounts of the sponge that, after more extensive fractionation of the polar extracts, lead to pure compounds and characterization of five minor steroidal alkaloids, amaranzoles B–F (2–6) in addition to 1. Amaranzoles C (3) and D (4) were simple double bond isomers of dehydro-1, but to our surprise, amaranzoles B (2), E (5) and F (6), differed from 1 by replacement of the unique C24-N imidazolyl structure with 24-O-steroidal 2-carboxy-imidazolecarboxylate esters. Because non-fused imidazole rings, excluding simple histamines, are less common among natural products,iv the discovery of the latter two constitutional variants in the same organism is intriguing from the perspective of biogenesis. A biosynthetic hypothesis is proposed that sheds light on a possible origin of the two families of amaranzoles that unifies their C24-N and C24-O constitutional differences through a common intermediate.

Results and Discussion

Two specimens of Phorbas amaranthus were collected in November 2006 from the Florida Keys. The first specimen (06-04-004a) was extracted sequentially with water, MeOH, and CH2Cl2. The aqueous MeOH partition was filtered through C18 reversed phase column followed by repeated reversed phase HPLC to give 1 (6.8 × 10−4 % dry wt) and a new analog, amaranzole B (2, 2.0 × 10−4 % dry wt). Similar treatment of the second sponge specimen (06-04-004b) gave amaranzoles C (3, 1.4 × 10−4 % dry wt), D (4, 2.3 × 10−4 %), E (5, 6.3 × 10−5 %) and F (6, 3.3 × 10−5 %) in addition to 1 and 2. Characterization of the new compounds on sub-milligram samples was carried out by FTIR, MS and 600 MHz NMR facilitated by a state-of-the-art 1.7 mm microcryoprobe with exceptionally high mass sensitivity. v Amaranzole B (2) was assigned the molecular formula C37H49N2Na3O15S3 (m/z 903.2108, [M–Na]−, Δ = +1.8 ppm) based on negative ion HRESIMS that corresponded the addition of the elements of CO2 to 1, consistent with a carboxy derivative of amaranzole A. 1H NMR, COSY and HSQC data of 2 revealed 1H and 13C chemical shifts for the sterol core that were essentially identical with those of 1, however, significant differences were observed for the side-chain in the vicinity of the C24 substituent compared to 1. The H24 methine signal (δ 5.39, dd, J = 8.0, 5.6 Hz) of 2 was significantly deshielded from that of 1 (δ 4.48, m) indicating a change in the electronic environment in the vicinity of the proton.

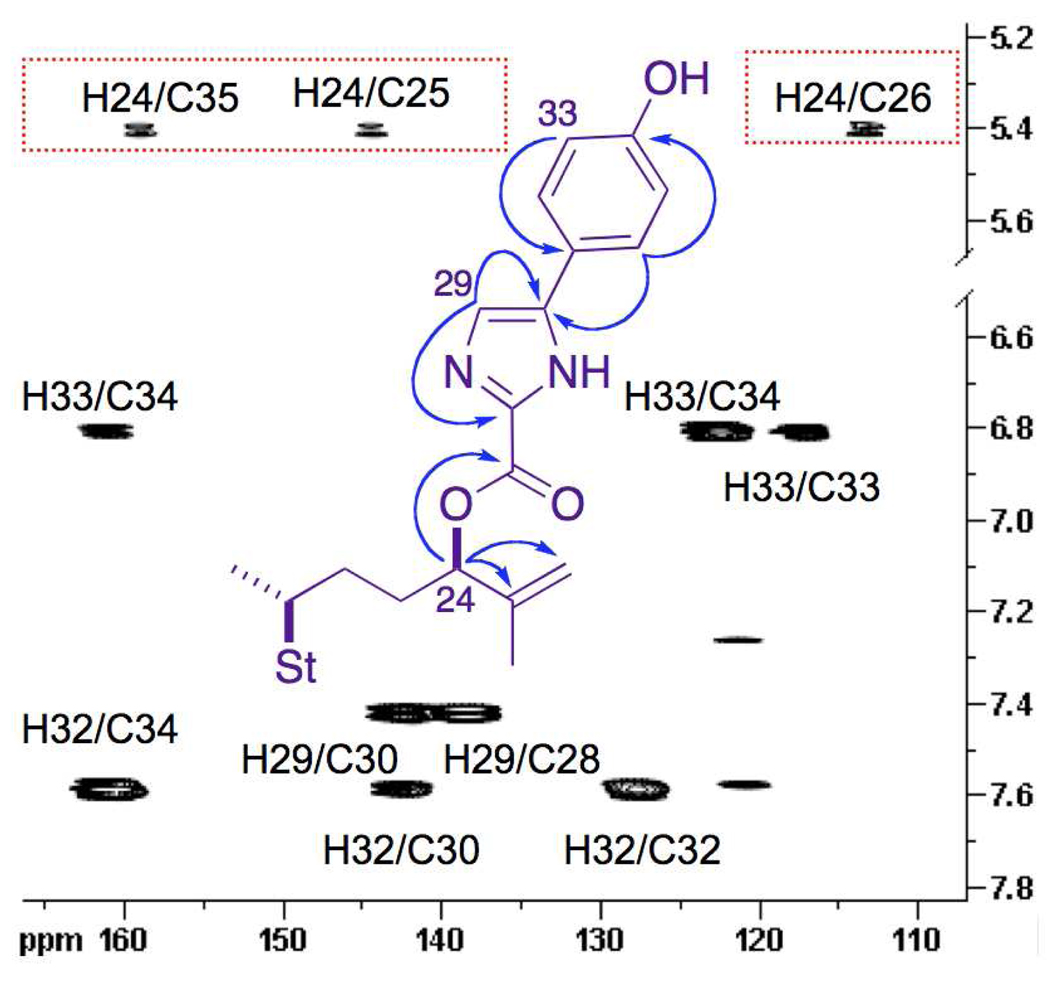

Compound 2 showed only one sp2 heteroaromatic 1H signal (δ 7.41 ppm, Table 1) suggesting substitution or oxidation at C28 or C29 of the imidazole ring. In addition, the H24 methine signal in 2 was shifted downfield compared to that of 1 (δ 4.48, m). Coupled HSQC of 2 showed the 1JCH of the single heteroaromatic 1H-13C couplet (δ 7.41 ppm, 1J = 187.8 Hz), was smaller than that characteristically associated with H2-C2 of five-membered ring azole heteroaromatics (1J ~200 Hz). For example, N-methylimidazole shows coupling constants of 1J = 205.7 Hz and 1J = 187.9 Hz for the H2-C2 and H4-C4 spin pairs respectively.vi Thus, the heteroaromatic singlet (δ 7.41, s) was assigned to C29 and the (C=O)O group was placed at C28 (the depicted imidazole tautomer is arbitrary). Although direct observation of the C=O signal (δ 158.8, s) by 13C NMR was not possible due to insufficient signal-to-noise in the mass-limited sample of 2, the signal was observed in HMBC (Figure 1).

Table 1.

1H NMR data for amaranzoles B–F (2–5) [CD3OD, 600 MHz. δ (mult., J Hz)]

| # | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.17 (m) ax; | 1.36 (m) | 1.32 (dd, 14.6, 3.0) | 1.31 (m) | 1.32 (m) |

| 2.47 (dd, 14.8, 3.2) eq. | 2.54 (dd, 14.6, 3.3) | 2.47 (dd, 14.6, 3.0) | 2.48 (14.6, 3.3) | 2.56 (dd, 14.7, 3.2) | |

| 2 | 4.90 (brq, 2.8) eq. | 4.91 (m)a | 4.92 (brq, 3.0) | 4.93 (brq, 3.1) | 4.92 (brq, 2.9) |

| 3 | 4.26 (dt, 12.3, 4.0) ax. | 4.28 (dt, 12.1, 3.9) | 4.30 (ddd, 12.5, 4.3, 3.6) | 4.30 (ddd, 12.5, 4.5, 3.4) | 4.30 (dt, 12.0, 4.0) |

| 4 | 1.78 (q, 12.3) ax; | 1.83 (q, 12.6) | 1.80 (q, 12.5) | 1.79 (brq, 12.5) | 1.84 (q, 12.7) |

| 2.29 (brd, 13.4) eq. | 2.36 (brd, 13.2) | 2.32 (m) | 2.31 (m) | 2.37 (brd, 12.8) | |

| 5 | 1.31 (m) ax. | 1.63 (m) | 1.45 (ddd, 12.5, 10.9, 3.0) | 1.46 (ddd, 12.5, 10.8, 3.0) | 1.63 (m) |

| 6 | 4.20 (td, 11.0, 4.5) ax. | 4.51 (m) | 4.12 (td, 10.9, 5.4) | 4.12 (td, 10.8, 5.4) | 4.51 (m) |

| 7 | 1.00 (m) ax. | 2.10 (m) | 1.82 (brq, 12.5) | 1.83 (brq, 12.6) | 2.10 (m) |

| 2.34 (dt, 12.4, 4.5) eq. | 2.73 (dd, 17.3, 6.5) | 3.12 (dd, 13.8, 5.4) | 3.13 (dd, 13.6, 5.4) | 2.74 (dd, 17.8, 6.7) | |

| 8 | 1.53 (m) | ||||

| 9 | 0.68 (m) | 1.71 (m) | 1.72 (m) | ||

| 11 | 1.34 (m) ax. | 2.12 (m) | 1.55 (m) | 1.60 (m) | 2.15 (m) |

| 1.53 (m) eq. | 1.59 (m) | ||||

| 12 | 1.13 (m) ax. | 1.36 (m) | 1.11 (m) | 1.15 (m) | 1.41 (m) |

| 2.00 (m) eq. | 1.97 (m) | 1.91 (brd, 12.6) | 1.97 (brd, 12.6) | 2.02 (m) | |

| 14 | 1.30 (m) | 2.07 (m) | 2.12 (m) | ||

| 15 | 1.08 (m) | 1.30 (m) | 2.22 (m) | 1.97 (m) | 1.32 (m) |

| 1.59 (m) | 1.62 (m) | 2.29 (m) | 2.27 (m) | 1.62 (m) | |

| 16 | 1.22 (m) | 1.06 (m) | 1.22 (m) | 1.38 (m) | 1.33 (m) |

| 1.84 (m) | 1.71 (m) | 1.62 (m) | 1.86 (m) | 1.93 (m) | |

| 17 | 1.13 (m) | 1.06 (m) | 1.05 (m) | 1.15 (m) | 1.21 (m) |

| 18 | 0.68 (s) | 0.54 (s) | 0.78 (s) | 0.87 (s) | 0.65 (s) |

| 19 | 1.10 (s) | 1.27 (s) | 0.96 (s) | 0.97 (s) | 1.28 (s) |

| 20 | 1.46 (m) | 1.28 (m) | 1.39 (m) | 1.56 (m) | 1.50 (m) |

| 21 | 0.96 (d, 6.0) | 0.90 (d, 6.2) | 0.91 (d, 6.6) | 1.00 (d, 6.6) | 1.00 (d, 6.5) |

| 22 | 1.15 (m) | 0.86 (m) | 0.90 (m) | 1.24 (m) | 1.16 (m) |

| 1.50 (m) | 1.29 (m) | 1.31 (m) | 1.55 (m) | 1.50 (m) | |

| 23 | 1.70 (m) | 2.00 (m) | 1.94 (m) | 1.71 (m) | 1.71 (m) |

| 1.92 (m) | 2.00 (m) | 1.92 (m) | 1.93 (m) | ||

| 24 | 5.39 (dd, 8.0, 5.6) | 4.51 (m) | 4.50 (m) | 5.41 (dd, 7.8, 5.4) | 5.41 (dd, 7.8, 5.4) |

| 25 | |||||

| 26 | 4.94 (s) | 4.67 (s) | 4.69 (s) | 4.95 (s) | 4.95 (s) |

| 5.07 (s) | 4.97 (s) | 4.96 (s) | 5.09 (s) | 5.08 (s) | |

| 27 | 1.82 (s) | 1.73 (s) | 1.71 (s) | 1.83 (s) | 1.83 (s) |

| 28 | 7.68 (brs) | 7.79 (brs) | |||

| 29 | 7.41 (s) | 6.83 (brs) | 6.92 (brs | 7.43 (brs) | 7.46 (brs) |

| 30 | |||||

| 31 | |||||

| 32 | 7.57 (d, 8.4) | 7.14 (d, 8.4) | 7.08 (d, 8.4) | 7.59 (d, 8.4) | 7.62 (d, 8.4) |

| 33 | 6.80 (d, 8.4) | 6.85 (d, 8.4) | 6.70 (d, 8.4) | 6.81 (d, 8.4) | 6.83 (d, 8.4) |

obscured by solvent peak

Figure 1.

Selected gHMBC correlations and 13C NMR chemical shifts for amaranzole B (2).

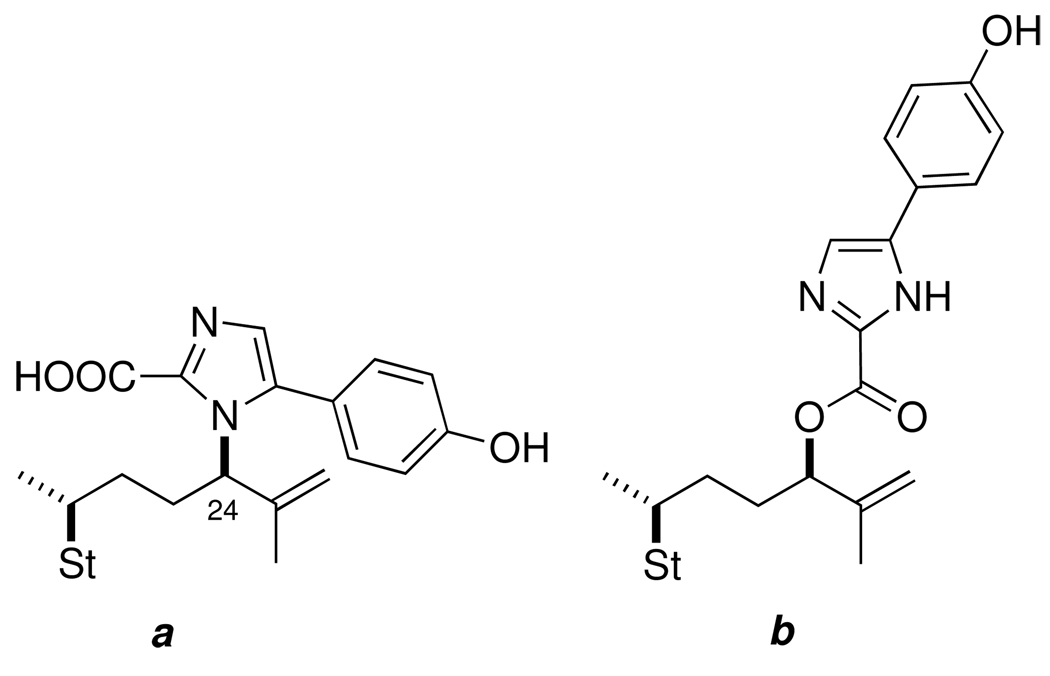

Two isomeric constitutional formulas (Figure 2) are possible for the proposed 4-(p-hydroxyphenyl) imidazole-2-carboxyl substituted sterol: a, a carboxylic acid with a C24-N linkage in which the imidazole is bonded to the side-chain through a nitrogen atom, and carboxylic ester b with a C24-O linkage. Both chemical and spectroscopic evidence pointed to b as follows. The deshielded 1H NMR signal for H24 in 2 (δ 5.39, dd, J = 8.0, 5.6 Hz, 1H) is more consistent with an esterified C24 carbinol than the CH-N bond of H24 in 1 (δ 4.48, m, 1H).iii

Figure 2.

Two constitutional isomers of steroidal imidazole-2-carboxylate, 2.

Imidazole-2-carboxylic acids are prone to spontaneous decarboxylation under neutral or acidic conditions,vii even at room temperature, however, prolonged heating of 2 in pyridine or DMSO (>120° C) failed to expel CO2 and returned only starting material or small amounts of de-sulfated analogs of 2 (1H NMR). This evidence suggested that the structure of amaranzole B could not contain substructure a, but could be an ester including substructure b. Evidence for the latter was provided by a weak HMBC (Figure 2) which showed a cross peak between H24 and the carbonyl signal (δ 159, s, (C=O)O). The latter is consistent with the carboxyl chemical shifts of known 2-carboxyimidazoles (e.g, ethyl 1-methylimidazole-2-carboxylate, δ 159.3 ppm).viii The structure 2 was confirmed in the present work by direct comparisons of the natural product with model compounds of defined constitution and absolute configuration prepared by asymmetric synthesis (vide infra).

The molecular formula of amaranzole C (3), C36H47N2Na3O13S3 – derived from negative ion HRESIMS data (m/z 857.2036 [M–Na]− Δmmu +0.6 amu) – is two hydrogen atoms less than the molecular formula of 1 suggesting a dehydro analog. This was confirmed by analysis of the 1H and 2D NMR of 3 which revealed a tetrasubstituted C8,9 C=C double bond in the sterol core. 1H chemical shifts and coupling constants of 3, showed the substitution as well as relative stereochemistry were identical to 1 at positions H1–H6, however the 1H NMR signals for H7 (δ 2.10 and 2.73), H11 (δ 2.12), and H14 (δ 2.07 ppm) in amaranzole C (3) were shifted downfield with respect to those of 1 (H7; δ 1.01 and 2.36 ppm; H11: δ 1.31 and 1.51 ppm; H14: δ 1.06 ppm). The location of the double bond at C9, C14 in 3 was secured by a gHMBC correlation from Me-19 to C9.ix Comparison of the 1H NMR signals for allylic protons of the Δ8(14) sterol trisulfate ester, hamigerol B x gave a good match with 3. The side-chain linkage of 3 was shown to be of the C24-N type found in 1 by similarity of 1H and 13C NMR signals for H24 and C24.

Amaranzole D (4), C36H47N2N3O13S3, was isomeric with amaranzole C (3). 1H and 2D NMR evidence showed that the C=C double bond in 4 was isomerized to C8,C14. Allylic proton signals H9 (δ 1.71, m, 1H) and H15 (δ 2.22, m; 2.29, m) were cross-correlated (gHMBC) to sp2 carbons C8 (δ 125.0, d), and C14 (δ 146.3, d). Additional gHMBC cross peaks were observed from H7 and H9 to C8, and from C18 methyl group to C14. Amaranzoles E (5) was the 8,14-dehydro derivative of amaranzole B (2) based on HRESITOFMS (m/z 901.1934, [M–Na]− Δmmu = 0) and nearly identical 1H and 13C chemical shifts for the sterols of 4 and 5. Similarly, amaranzole F (6) (m/z 901.1948 [M–Na]− Δmmu = +1.4) was assigned as the 8,9-dehydro derivative of amaranzole B (2) and comparison of 1H, 13C NMR data with amaranzole C (3).

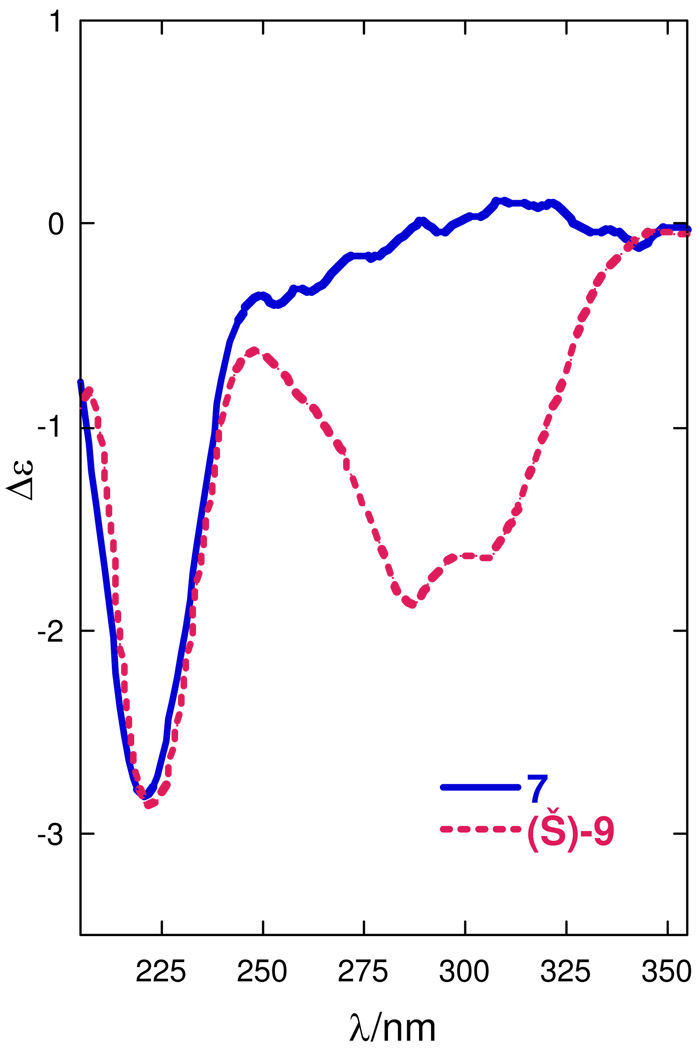

Since there were no precedents for the C24-N and C24-O variants that constitute the two sub-families of amaranzoles, we elected to determine the stereochemistry of 2 and ascertain the relationship to 1. The absolute configuration of stereocenters within the sterol cores in 1–6 are known with certainty from firm principles of sterol biosynthesis, but the C24 stereocenter in 1 was more difficult to assign because it is located three bonds removed from the nearest stereogenic center, C21. To solve the C24 stereocenter in 1,iii we exploited Cotton effects observable in the CD spectrum that arise from exciton coupling of π-π* transitions of the 4-(p-hydroxyphenyl) imidazolyl group and the terminal vinylidene group.xi However, the significant bond reorganizations in the side-chains of 2, 5 and 6 with respect to 1 required an independent solution to the configuration of C24 in the new compounds. We turned to chiroptical comparisons of 2 with a different synthetic analog of defined configuration.

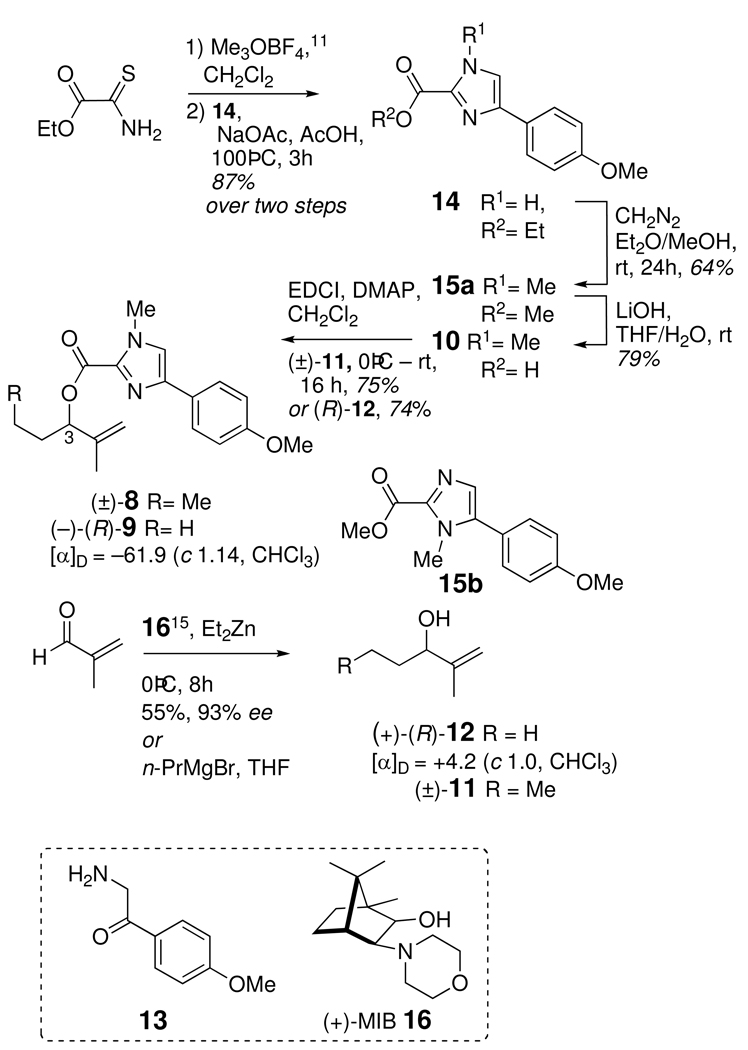

In order to simplify comparative CD analyses, 2 was converted to the N,O-dimethyl compound 7 with excess CH2N2. Synthetic N,O-dimethyl analogs (±)-8 and (−)-R-9 were prepared by coupling (EDCI, DMAP) of the acid-sensitive imidazole-2-carboxylic acid 10 with the corresponding allylic alcohols (±)-11 and (+)-12 which were made available as follows. Methylation of ethyl thiooxamatexii,xiii with Meerwein's saltxiv (Scheme 1) followed by condensation with 2-amino-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethanone (13)xv gave imidazolecarboxylate ester 14. Methylation of 14 (CH2N2, Et2O-MeOH) proceeded with concomitant transesterification, to afford a mixture of methyl esters. The major product 15a (64%) was separated from the minor regioisomer 15b (32%) by silica chromatography. Base hydrolysis of 15a provided imidazolecarboxylic acid 10. The latter compound was prone to spontaneous decarboxylation at acidic pHs, even at room temperature, and required careful handling.

Scheme 1.

Addition of n-propylmagnesium bromide to methacrolein gave racemic allylic alcohol (±)-11, while the optically-enriched homolog, (+)-R-12, was obtained by asymmetric addition of diethylzinc to methacrolein in the presence of (2R)-(+)-3-exo-N-morpholinoisoborneol (16, (+)-MIB).xvi The optical purity and assignment of configuration of (+)-R-12 (93 %ee) were secured by the modified Mosher's methodxvii after conversion of (+)-R-12 to the corresponding (R)-and (S)-MTPA esters.

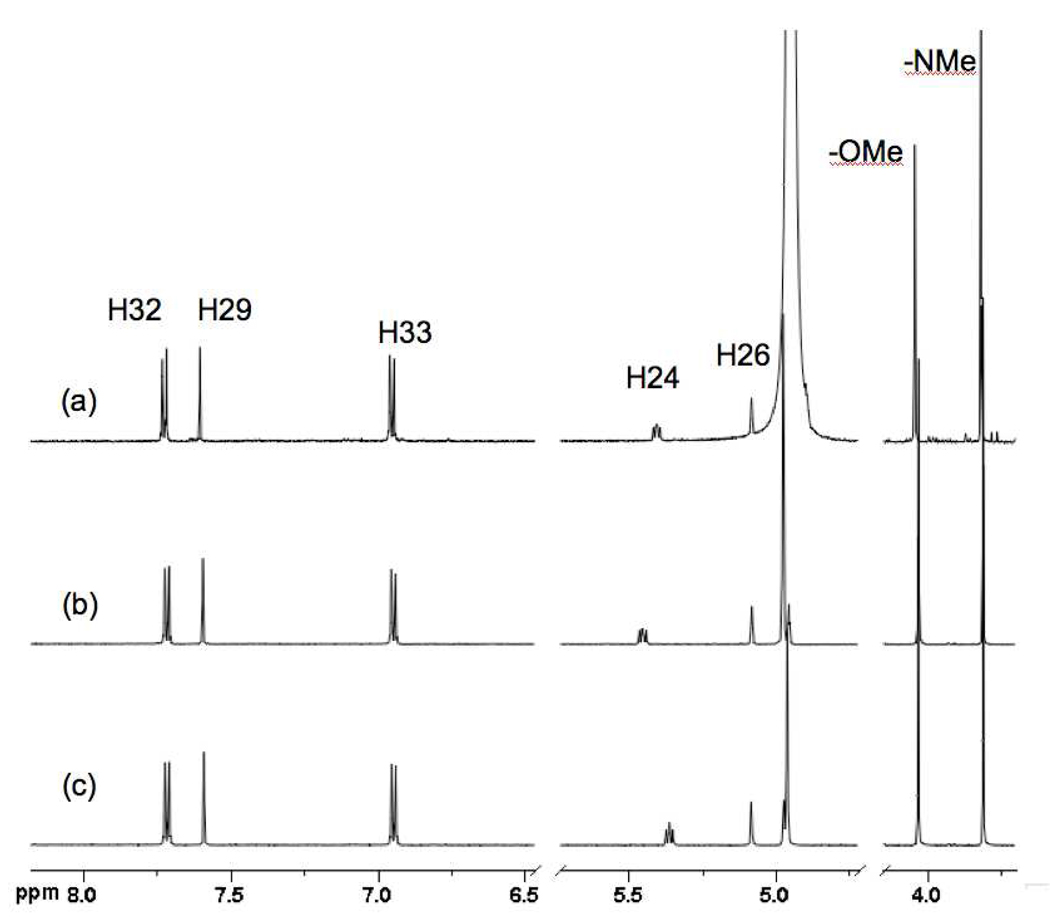

Racemic (±)-8 and (−)-R-9 displayed NMR chemical shifts (Figure 3), close to those of 2 and 7, particularly H3 (H24 steroid numbering, δ 5.45, dd, J = 8.0, 5.6 Hz, 1H and 5.36, t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, respectively), but significantly different from those of 1 (δ 4.48, m).iii

Figure 3.

1H NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) of (a) 7, (b) (±)-8, and (c) (−)-9

As reported earlier,iii,xi the dominant feature in the CD spectrum of 1, and by extension, 2 and its dimethyl homolog 7, is associated with a π-π* transition of imidazole chromophore; the sign and magnitude of this Cotton effect is dependent upon the configuration at C24. The CD spectra of 7 and (−)-R-9 (Figure 4) showed the same weak Cotton effect at λ 221 nm (Δε−2.8 and Δε−2.9, respectively); therefore 2 and 7 have 24R configuration.

Figure 4.

CD spectra of N,O-dimethylamaranzole B (7) and model compound (−)-R-9 (MeOH, 23°C).

The new compounds, together with 1, derive from a polar fraction that exhibits significant feeding deterrence in assays using the blue head wrasse, Thalasoma bifasciatum, a common predatory reef fish. We chose to test whether amaranzoles were responsible for this activity. Two mixtures of amaranzoles – one containing 1, 3 and 4, and the other containing 2, 5, and 6 – were tested in fish feeding assays using a protocol we reported earlier.i The mixture containing 1, 3, and 4 elicited the deterrent activity when tested at 16x natural concentration. We conclude that the amaranzoles are minor contributors to the chemical defense of Phorbas amaranthus against T. bifasciatum.xviii

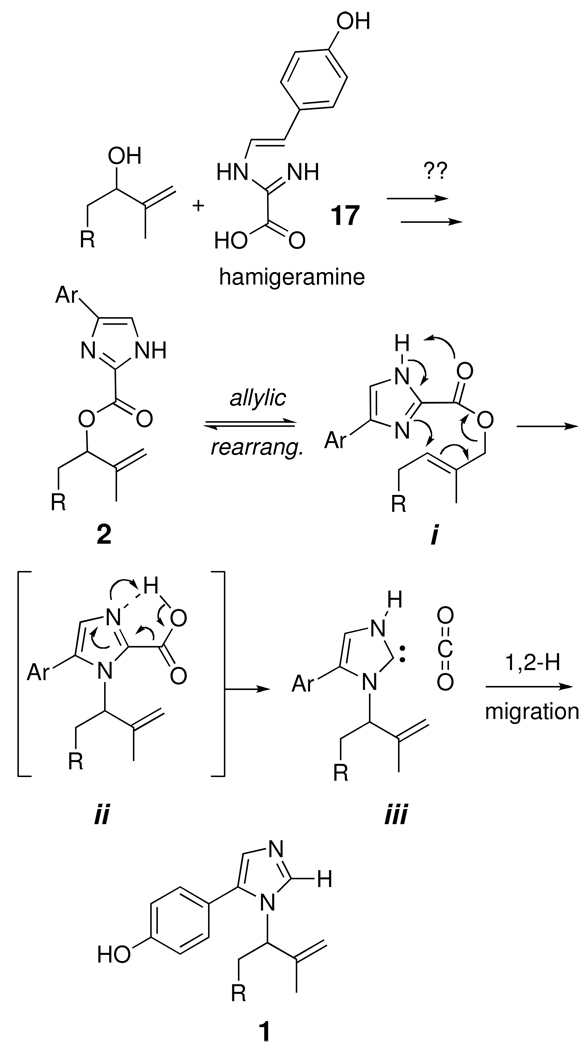

The structures of 1–6 suggest the involvement of a common intermediate in their biosynthesis. Formation of the p-hydroxyphenyl-imidazole side chain may commence by coupling of an allylic alcohol (steroid side chain) and a suitable imidazole precursor, for example, hamigeramine (17) isolated from the marine sponge Hamigera hamigera.xix Oxidative modification at C24 of the side chain is evident in the two structural subfamilies represented by amaranzoles A–F, however, the biosynthesis of 1, 3 and 4 clearly diverges from that of 2, 5 and 6. Because all six natural products occur together in the sponge consistently, it is most likely their biosynthesis links the C24-N and C24-O subfamilies through a common pathway. One possibility (Figure 5) invokes two allylic rearrangements of imidazole 2; first to give the primary allylic ester i that further rearranges to the transient imidazolinium-2-carboxylic acid ii with formation of a C–N bond. Facile loss of CO2 from ii would give a relatively stable carbene iii (4-substituted imidazole-2-ylidene) which undergoes 1,2-hydride migrationxx to restore the aromatic imidazole ring of 1.xxi The enthalpic cost of replacing the stronger C–O bond with a C–N bond would be paid in part by the energetically favorable loss of CO2.

Figure 5.

A possible biosynthetic pathway linking amaranzoles C (3) and E (5).

Finally, it is noteworthy that the 24R configuration is retained in all amaranzoles. If the allylic alcohol precursor to 5 (Figure 5) is formed with high stereochemical fidelity, the subsequent interconversion of the two sub-families of amaranzoles must proceed through a tightly orchestrated, enantiospecific mechanism with retention of configuration.

Although insufficient amounts of amaranzoles B–F (2–6) were available for assay of biological activity, brief a evaluation cytotoxicity of amaranzole A (1) and the less-polar analog, 17 (obtained by acid hydrolysis of 1; 3M HCl-MeOH, 75 °C) towards human colon tumor cells (HCT-116) was carried out. Compound 17 exhibited significant cytotoxicity (IC50 = 4.4 µM), however, the natural product 1 was essentially inactive (IC50 > 32 µM). Presumably, cell-permeability of 1 is restricted by the highly charged sulfate groups, which is relaxed in the more lipophilic parent molecule 17.

Conclusions

We have isolated and structurally characterized five new amaranzoles B–F (2–6) that belong to two related families with different side-chain bond constitutions incorporating p-hydroxyphenylimidazole. Structure elucidation of 2, 5 and 6 revealed an unexpected C–O bond at C24 instead of the C–N imidazole found in the other amaranzoles A (1), C (3) and D (4). The two amaranzole families may be linked through allylic rearrangements that interchange C24-N and C24-O bonds with concomitant loss of CO2. The polar sulfated 1 showed no activity against HCT-116 tumor cells, however, the more liphophilic derivative 17 was cytotoxic (IC50 = 4.4 µM).

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

1H and 2D NMR spectra were acquired using a 600 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a {13C}1H 1.7 mm microcryoprobe, or 500 MHz spectrometers {13C}1H and {1H}13C probes. All 1H spectra were acquired in MeOH-d4 and referenced to δ 3.31 ppm. UV spectra were recorded on a double-beam spectrophotometer. Optical rotations were measured using a digital polarimeter. Circular dichroism (CD) measurements were acquired on a grating spectropolarimeter using dilute solutions in spectroscopic grade solvent and quartz cells (1 mm pathlength). IR spectra were obtained using an FTIR spectrometer equipped with a ZnSe ATR plate. HPLC was carried out using a dual-pump preparative instrument equipped with a high-dynamic range UV-vis detector set to λ 260 nm. For semi-preparative HPLC, RP column (5μ C18-bonded silica, 10 × 250 mm) was used. Preparative HPLC was carried on radial compression cartridges (6 μ C18-bonded silica 25×100mm) and commercial HPLC grade solvents were used for liquid chromatography. THF and CH2Cl2 and DMF were dried by passage through dual-alumina cartridges under an atmosphere of Ar, and reagent-grade chemicals were used as purchased.

Animal Material. Extraction and Isolation

Phorbas amaranthus Duchassaing & Michelotti 1864 was collected in November 2006 using scuba from Dry Rocks Reef, Key Largo, Florida (25°7.850’ N, 80°17.521’ W), at a depth of 20–25’. Specimens were identified by J.R.P and stored at −20 °C until required. Vouchers samples are archived at UCSD. Two specimens (06-04-004a and 06-04-004b) of Phorbas amaranthus collected at the same site were analyzed separately. The first sample (06-04-004a, 88.3g) was lyophilized, extracted with water (1L), followed by MeOH (1L), and finally CH2Cl2 (1L). The organic extracts were combined, dried, and partitioned between hexane and H2O/MeOH 1:9. The hexane layer (‘A’) was separated, and the MeOH layer was adjusted to 1:1 by addition of water, then partitioned against CH2Cl2. The CH2Cl2 layer (‘B’) was separated from the aqueous MeOH layer (‘C’) and the solvents were removed under reduced pressure. The crude MeOH extract C (33.5 g) was subjected to filtration through reversed phase silica (C18 cartridge, conditioned with H2O/MeOH 19:1) eluting with water, then MeOH/CH3CN 1:1 to give two fractions. The second fraction (7.03g, 1.46g further purified) was then subject to reversed phase chromatography (C18 cartridge) using a stepwise gradient (H2O/MeOH 4:1, 7:3, 3:2, 1:1, 2:3, 3:7, 1:4, 1:9, then MeOH) to attain nine fractions. A portion (42.5 mg) of the fraction (127.3 mg) eluting with H2O/MeOH (3:2) was subject to gradient semi-preparative reversed phase HPLC (flow rate: 2.5 mL/min; mobile phase: H2O/CH3CN containing 0.5 M NaClO4; gradient: 7:3 isocratic 15 minutes to 2:3 over 30 minutes; λ=254 nm) to give five fractions. The third fraction contained amaranzole A (4.2 mg, 1). The fourth fraction was subjected to gradient semi-preparative reversed phase HPLC (same conditions as above, except mobile phase: H2O/CH3CN containing 0.75 M NaClO4) to give amaranzole B (1.2 mg, 2).

A second lyophilized sample of Phorbas amaranthus (06-04-004b, 131.2 g) was extracted with 1L of H2O/MeOH 1:1 (23°C, overnight). The aqueous-MeOH phase was removed and extraction was repeated twice; first with 1L H2O/MeOH 1:1, then 1L MeOH. The sponge tissue was then blended at high speed and extracted once more with 1L MeOH (23°C, overnight) and the combined extracts concentrated under reduced pressure. The remaining sponge tissue was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 × 1L). The CH2Cl2 extract was dried and partitioned between hexane and H2O/MeOH 1:9. The aqueous MeOH layer was dried and combined with the previous MeOH extracts to give a crude aqueous MeOH extract (48.6 g). A portion (33.9 g) of the aqueous MeOH crude extract was filtered through a reversed phase cartridge (C18, conditioned with H2O/MeOH 19:1) eluting with H2O/MeOH 9:1, H2O/MeOH 1:9, and i-PrOH to give three fractions. A portion (1.16 g) of the second eluting fraction (5.82 g) was subjected to gradient preparative reversed phase HPLC (flow rate: 25 mL/min; mobile phase: H2O/CH3CN containing 1.5M NaClO4; gradient: 73:27 isocratic 10 minutes to 23:77 over 30 minutes; λ=240nm) to give seven fractions. A portion (4.6 mg) of the third fraction (61.6 mg) was subjected to a repeated gradient reversed phase HPLC (flow rate: 2.5 mL/min; mobile phase: H2O/CH3CN containing 0.5 M NaClO4; gradient: 7:3 isocratic 15 minutes to 2:3 over 30 minutes; λ = 254 nm) to give amaranzole C (0.19 mg, 3), amaranzole D (0.32 mg, 4), and amaranzole A (0.35 mg, 1). A portion (1.4 mg) of the fourth fraction (8.4 mg) was subjected to repeated gradient reversed phase C18 HPLC (H2O/CH3CN containing 1.5 M NaClO4, flow rate: 2.5 mL/min; gradient: 61:39 isocratic 15 minutes to 31:69 over 30 minutes; λ = 260 nm) to give amaranzole F (0.10 mg, 6), amaranzole E (0.19 mg, 5), and amaranzole B (0.15 mg, 2).

Amaranzole B (2)

colorless glass; [α]21 D +21.8 (c 0.52, MeOH); FTIR (ATR, ZnSe) νmax 3487, 2945, 1652, 1449, 1232, 1065, 1001, 915, 839 cm−1; UV (H2O-CH3CN 7:3) λmax 256 nm (7800), 289 (9300), 310 (8000); CD (H2O-CH3CN 7:3) 218nm (Δε −1.0); 1H NMR, see Table 1; 13C NMR (from 600 MHz, HSQC/gHMBC data, CD3OD) δ 160.2 (C34), 158.8 (C35), 144.3 (C25), 142.2 (C30), 138.4 (C28), 127.5 (C32), 122.5 (C31), 120.6 (C29), 116.9 (C33), 113.3 (C26), 79.6 (C24), 78.5 (C3), 77.9 (C6), 76.2 (C2), 56.9 (C17), 55.2 (C9), 51.6 (C5), 43.4 (C13), 42.2 (C1), 40.6 (C12), 39.6 (C7), 37.8 (C10), 36.1 (C20), 34.8 (C8), 32.3 (C22), 29.9 (C14), 29.9 (C23), 28.5 (C16), 25.4 (C4), 24.3 (C15), 21.8 (C11), 18.6 (C21), 17.9 (C27), 15.6 (C19), 11.8 (C18). HRESITOFMS m/z 903.2108 [M–Na]− calcd for C37H49N2Na2O15S3, 903.2090.

Amaranzole C (3)

colorless glass; FTIR (ATR, ZnSe) νmax 3454, 2947, 1631, 1230, 1110, 1002, 949 cm−1; UV (H2O/CH3CN 7:3) λmax 250nm (ε 8300); CD (H2O-CH3CN 7:3) 201nm (Δε +3.5), 217 (Δε −8.0); 1H NMR, see Table 1; HRESITOFMS m/z 857.2036 [M–Na]− calcd for C36H47N2Na2O13S3, 857.2030.

Amaranzole D (4)

colorless glass; FTIR (ATR, ZnSe) νmax 3487, 2951, 1651, 1450, 1327, 1230, 1072, 1001, 964, 916, 840 cm−1; UV (H2O-CH3CN 7:3) λmax 250 nm (ε 8300); CD (H2O-CH3CN 7:3) λ 201 nm (Δε +4.7), 215 (Δε −1.9); 1H NMR, see Table 1; HRESITOFMS m/z 857.2051 [M–Na]− calcd for C36H47N2Na2O13S3, 857.2030.

Amaranzole E (5)

colorless glass; FTIR (ATR, ZnSe) νmax 3559, 2952, 1651, 1453, 1386, 1232, 1113, 1001, 918, 843 cm−1; 1H NMR, see Table 1; HRESITOFMS m/z 901.1941 [M–Na]− calcd for C37H47N2Na2O15S3, 901.1934.

Amaranzole F (6)

colorless glass; FTIR (ATR, ZnSe) νmax 3523, 2948, 1651, 1451, 1233, 1069, 1002, 915, 841 cm−1; HRESITOFMS m/z 901.1948 [M–Na]− calcd for C37H47N2Na2O15S3, 901.1934).

N,O-Dimethyl-amaranzole B (7)

Excess ethereal diazomethane was added dropwise to a mixture of amaranzoles B, E, and F (~1:1:1, 1.5 mg) in 0.5 mL MeOH. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1.5 h. The solvent was evaporated under a stream of N2. The mixture was subject to three rounds of reversed phase HPLC; firstly with a gradient of 10–100% (CH3CN/H20 + 1M NaClO4, over 40 min) followed by two passages with 50–100% (CH3CN/H20 + 1M NaClO4 over 40 min) to give 7 (ca. 30 µg, based on comparison of UV to (−)-9): UV (MeOH) λmax 261 nm (ε 16200), 286 nm (ε 15400), 309 nm (ε 8600); CD (MeOH) 221 nm (Δε −2.8); 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts for the steroidal ABCD ring system are nearly identical to those of amaranzole B (1). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.73 (d, 2H, 8.8 Hz), 7.61 (s, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 5.41 (dd, J = 8.0, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 5.08 (m, 1H), 4.90 (m, 1H), 4.05 (s, 3H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 1.84 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD, partial data) δ 160.2 (C34), 144.2 (C25), 142.6 (C30), 137.2 (C28), 127.4 (C32), 126.6 (C31), 123.4 (C29), 114.7 (C33), 113.6 (C26), 79.9 (C24), 55.4 (OMe), 36.5 (NMe).

Ethyl 4-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1H-imidazole-2-carboxylate (14)

Trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate (3.31 g, 22.4 mmol) was added to a stirred solution of ethyl thiooxamatexii (2.59 g, 19.4 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (60 mL) in three portions over 1 hour at room temperature. After stirring an additional 30 minutes, the solvent was evaporated and the crude product used immediately in the next step. Sodium acetate (3.18 g, 38.8 mmol), 2-amino-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethanone (13, 6.5 g, 19.3 mmol), and acetic acid (60 mL) were added and the mixture was stirred for 3 hours at 100 °C. The mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Water (400 mL) was added, and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 100 mL). The combined organic extracts were dried (MgSO4), and the solvent evaporated. The crude product was recrystallized from MeOH/H2O to give pure 14 (4.18 g, 87% yield). mp 132–134 °C. FTIR (ATR, ZnSe) νmax 2981, 2938, 2837, 1715, 1615, 1479, 1458, 1441, 1379, 1288, 1248, 1178, 1150, 1131, 1027, 795 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3+0.1% TFA-d) δ 7.67 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.42 (s, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.42 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.38 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3+0.1% TFA-d) δ 159.6 (C), 158.6 (C), 139.5 (C), 136.8 (C), 126.9 (CH), 122.9 (C), 120.4 (CH), 114.2 (CH), 62.2 (CH2), 55.2 (CH3), 14.0 (CH3); HRESITOFMS m/z 247.1079 [M+H]+ (calcd for C13H15N2O3, 247.1077)

Methyl 4-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1-methyl-1H-imidazole-2-carboxylate (15a)

A solution of ethereal diazomethane (~0.2 M) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of 5 (100 mg, 0.406 mmol) in MeOH/Et2O (8:3, 5.5 mL) at room temperature. When a yellow color persisted, excess diazomethane (~10 equiv) was added and the reaction was stirred for 24 hours. The solvent was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen, and the mixture was subject to silica flash chromatography (1:4 EtOAc/hexanes) to give 15a (64 mg, 64% yield) and 15b (34 mg, 34% yield).

Methyl 4-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1-methyl-1H-imidazole-2-carboxylate (15a)

FTIR (ATR, ZnSe) νmax 2952, 2838, 1709, 1613, 1443, 1419, 1248, 1179, 1151, 1116, 1047, 1024, 930, 832 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.72 (d, 2H, 8.8 Hz), 7.23 (s, 1H), 6.91 (d, 2H, 8.8 Hz), 4.04 (s, 3H), 3.96 (s, 3H), 3.82 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.6 (C), 161.2 (C), 143.9 (C), 138.0 (C), 128.5 (CH), 127.7 (C), 123.4 (CH), 115.9 (CH), 57.2 (CH3), 54.3 (CH3), 38.0 (CH3); HRESITOFMS m/z 247.1080 [M+H]+ (calcd for C13H15N2O3, 247.1077).

Methyl 5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1-methyl-1H-imidazole-2-carboxylate 15b

FTIR (ATR, ZnSe) νmax 2952, 1711, 1453, 1290, 1252, 1201, 1129, 1029, 949, 839, 789 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.30 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.14 (s, 1H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 3.94 (s, 3H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 3.85 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.1 (C), 159.9 (C), 138.5 (C), 136.7 (C), 130.6 (CH), 128.5 (CH), 120.8 (C), 114.3 (CH), 55.3 (CH3), 52.1 (CH3), 33.7 (CH3); HRESITOFMS m/z 247.1076 [M+H]+ (calcd for C13H15N2O3, 247.1077).

4-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-1-methyl-1H-imidazole-2-carboxylic acid (10)

A solution of LiOH (10.4 mg, 0.248 mmol) in THF/H2O (8:3, 3.2 mL) was added to ester 15a (43 mg, 0.165 mmol), and the mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The THF was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the solution was cooled to 0 °C. Aqueous HCl (0.1 M) was added dropwise until pH ~4, at which point the free acid precipitated as a white solid. The mixture was centrifuged, the supernatant removed and the solid washed with H2O (2 mL), and dried under high vacuum to give the free acid 10 (30.3 mg, 79%) as a colorless solid. 10: FTIR (ATR, ZnSe) νmax 2909, 2834, 1659, 1327, 1270, 1254, 1023, 910, 811, 796 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.81 (s), 7.72 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.97 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 3.95 (s, 3H), 3.77 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 159.3 (C), 158.7 (C), 138.3 (C), 137.5 (C), 126.0 (CH), 125.1 (C), 121.8 (CH), 114.1 (CH), 55.1 (CH3), 35.7 (CH3); HRESITOFMS m/z 233.0923 [M+H]+ (calcd for C12H13N2O3, 233.0921).

2-Methylhex-1-en-3-yl 4-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1-methyl-1H-imidazole-2-carboxylate (9)

A solution of EDCI (30.0 mg, 0.156 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (3 mL) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of the 10 (21.1 mg, 0.091 mmol), (±)-2-methylhex-1-en-3-olxxii (26 mg, 0.228 mmol) and DMAP (2.4 mg, 0.020 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (2 mL) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred for an additional two hours then at room temperature for 18 hours, before removal of solvent under reduced pressure and purification of the residue by silica flash chromatography (15:85 EtOAc/hexanes) to give the ester (±)-8 (22.1 mg, 74% yield). FTIR (ATR, ZnSe) νmax 2958, 1707, 1450, 1281, 1262, 1123, 1105, 836, 786 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.73 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.20 (s, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 5.43 (t, 1H, 6.8 Hz), 5.09 (m, 1H), 4.95 (m, 1H), 4.00 (s, 3H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 1.93-1.85 (m, 1H), 1.83 (s, 3H), 1.79-1.70 (m, 1H), 1.50-1.34 (m, 2H), 0.96 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.70 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.55 (s, 1H), 6.93 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 5.45 (dd, J = 8.0, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 5.08 (m, 1H), 4.95 (m, 1H), 4.00 (s, 3H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 1.93-1.85 (m, 1H), 1.83 (s, 3H), 1.80-1.71 (m, 1H), 1.50-1.32 (m, 2H), 0.98 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ 160.8 (C), 159.4 (C), 144.7 (C), 143.0 (C), 137.7 (C), 127.7 (CH), 127.0 (C), 123.7 (CH), 115.0 (CH), 113.8 (CH2), 79.8 (CH), 55.7 (CH3), 36.7 (CH3), 35.9 (CH2), 19.9 (CH2), 18.4 (CH3), 14.1 (CH3); HRESITOFMS m/z 329.1866 [M+H]+ (calcd for C19H25N2O3, 329.1860).

(R)-2-Methylpent-1-en-3-yl 4-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1-methyl-1H-imidazole-2-carboxylate (−)-9

A solution of EDCI (32.0 mg, 0.166 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (4 mL) was added dropwise to a mixture of 7 (32.0 mg, 0.138 mmol), (R)-2-methylpent-1-en-3-ol (27.6 mg, 0.276 mmol) and DMAP (1.7 mg, 0.014 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL) at 0 °C with stirring. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 2 hours then at room temperature for 18 hours. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue subjected to silica flash chromatography (15:85 EtOAc/hexanes) then reversed phase HPLC (C18, 3:1 CH3CN/H2O) to give the ester (−)-9 (32.5 mg, 75% yield). [α]24 −61.9° (c 1.14, CHCl3); FTIR (ATR, ZnSe) νmax 2966, 1705, 1505, 1448, 1400, 1246, 1120, 1089, 1030, 949, 903, 835, 794 cm−1; UV (MeOH) λmax 261 nm (ε 16200), 286 nm (ε 15200), 309 nm (ε 8600); CD (MeOH) λ 222 nm (Δε −2.9), 287 (Δε −1.9), 306 (Δε −1.6); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.71 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (s, 1H), 6.94 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 5.36 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 5.09 (m, 1H), 4.97 (m, 1H), 4.03 (s, 3H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 1.95-1.80 (m, 2H), 1.83 (s, 3H), 0.98 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ 160.8 (C), 159.4 (C), 144.3 (C), 143.0 (C), 137.7 (C), 127.7 (CH), 127.0 (C), 123.7 (CH), 115.0 (CH), 114.0 (CH2), 81.5 (CH), 55.7 (CH3), 36.7 (CH3), 26.7 (CH2), 18.4 (CH3), 10.4 (CH3); HRESITOFMS m/z 315.1703 [M+H]+ (calcd for C18H23N2O3, 315.1703)

(R)-2-methylpent-1-en-3-ol (+)-12

Diethylzinc (8 mmol, 1M in hexanes) was added to a stirred solution of (+)-MIB (48.5 mg, 0.2 mmol) in hexanes (20 mL) at 0 °C. Freshly distilled methacrolein (280 mg, 4 mmol) was added dropwise to the reaction and stirred for 8 h at 0 °C. The reaction was quenched with saturated ammonium chloride (40 mL), and extracted with pentane (3 × 100 mL). The combined organic layers were dried (MgSO4), filtered, the solvent evaporated under reduced pressure at 0 °C. The mixture was subject to silica flash chromatography (1:9 diethyl ether/pentane) to give (+)-12 (220 mg, 55% yield, 93% ee). [α]24 D = +4.2 (c 1.0, CHCl3), lit. +4.1 (CH2Cl2, 90% ee)xxiib; (−)-12, [α]24 D = −5.6 (c 1.0, CHCl3, >98% ee). xxiia The % ee was determined by 1H NMR analysis of the both (+) and (−)-MTPA esters. 1H and 13C NMR data were identical to literature values.xxii

Desulfation of Amaranzole A (1)

A solution of amaranzole A (1, ~ 1 mg) was heated in 3M HCl (MeOH-H2O, 2 mL) at 75 °C for 45 min. The cooled solution was concentrated and passed through a SiO2 cartridge, which was which was eluted with MeOH-CH2Cl2 to give the desulfated compound 17 (quant). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) (selected) δ 3.93 (brq, J = 4.0 Hz, H2), 3.50 (dt, J = 10.9, 4.0 Hz, H3), 3.39 (td, J = 10.9, 4.6 Hz, H6), 1.72 (s, H27), 1.00 (s, H19), 0.92 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, H21), 0.63 (s, H18). The remainder of the 1H NMR signals were essentially identical to those of 1. HRESITOFMS: m/z 577.3996 [M+H]+, calcd. for C36H53N2O4, 577.4005.

Cytotoxicity Assay

Amaranzole A (1) and the des-sulfato derivative 17 were evaluated for in vivo cytotoxicity against cultured human colon tumor cells (HTC-116) using a cell viability assayed based on a colorimetric end point of the soluble formazan dye from co-incubated MTS [(3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2Htetrazolium, inner salt] as described elsewhere.xxiii Amaranzole A (1) was inactive (IC50 >32 µM) and 17 gave an IC50 of 4.4 µM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank T. Hong and M. Masuno for preliminary work on Phorbas amaranthus, E. Rogers and A. Jansma for assistance with NMR experiments, C. Skepper for preparation of (+)-16, J. Cowart, T.-L. Loh and W. Leong for running antifeedant assays, and UC Riverside Mass Spectrometry Facility for HRMS measurements. The 500 MHz NMR spectrometers were purchased with a grant from NSF (CRIF program CHE0741968). This investigation was supported by grants from NIH (CA122256 to T.F.M), a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award NIH/NCI (T32 CA009523 to B. I. M), the National Undersea Research Program at UNCW and the Coral Reef Conservation Program (NOAA NA96RU-0260 to J.R.P.). We are grateful to the captain and crew of the RV Seward Johnson for logistical support during collecting expeditions and in-field assays.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: 1H, 13C NMR and 2D NMR spectra of 2–6, and synthetic compounds 8–10, 14, 15a,b and 17. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- i.Pawlik JR, Chanas B, Toonen RJ, Fenical W. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1995;127:183–194. [Google Scholar]

- ii.Masuno MN, Pawlik JR, Molinski TF. J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:731–733. doi: 10.1021/np034037j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- iii.Morinaka BI, Masuno MN, Pawlik JR, Molinski TF. Org. Lett. 2007;9:5219–5222. doi: 10.1021/ol702325e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- iv.For example, bromotopsentin Murray LM, Lim TK, Hooper JNA, Capon RJ. Aust. J. Chem. 1995;48:2053. For comprehensive reviews of imidazole-containing natural products, see Jin Z. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:382–445. doi: 10.1039/b718045b. earlier reviews in the series, including Lewis JR. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1996;13:435–467. and references cited within.

- v.Molinski TF. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010 doi: 10.1039/b920545b. in press, DOI: 10.1039/b920545b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vi.Pachler KGR, Pachter R, Wessels PL. Org. Magn. Reson. 1981;17:278–284. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krowicki K, Lown JW. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:3493–3501. [Google Scholar]

- viii.Baird EE, Dervan PB. J. Am. Chem Soc. 1996;118:6141–6146. [Google Scholar]

- ix.Me-19 gave a strong gHMBC correlation to a C9 (δ 137.3, s).

- x.Chang J-F, Lee J-S, Sun F, Jares-Erijman EA, Cross S, Rinehart KL. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:1195–1199. doi: 10.1021/np070027x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xi.Morinaka BI, Molinski TF. Chirality. 2008;20:1066–1070. doi: 10.1002/chir.20636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xii.Scheibye S, El-Barbary AA, Lawesson S-O. Tetrahedron. 1982;38:3753–3760. [Google Scholar]

- xiii.(a) Oliver JE, Sonnet PE. J. Org. Chem. 1973;38:1437–1438. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamanaka H, Mizugaki M, Sakamoto T, Sagi M, Nakagawa Y, Takayama H, Ishibashi M, Miyazaki H. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1983;31:4549–4553. [Google Scholar]

- xiv.(a) Meerwein H, Hinz G, Hofmann P, Kroning E, Pfeil E. J. Prakt. Chem. 1937;147:257–285. [Google Scholar]; (b) Meerwein H, Bettenberg E, Gold H, Pfeil E, Willfang G. J. Prakt. Chem. 1940;154:83–156. [Google Scholar]

- xv.Holub JM, O'Toole-Colin K, Getzel A, Argenti A, Evans MA, Smith DC, Dalglish GA, Rifat S, Wilson DL, Taylor BM, Miott U, Glersaye J, Lam KS, McCranor BJ, Berkowitz JD, Miller RB, Lukens JR, Krumpe K, Gupton JT, Burnham BS. Molecules. 2004;9:135–157. doi: 10.3390/90300134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xvi.(a) Nugent W. Chem. Commun. 1999:1369–1370. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kelly AR, Lurain AE, Walsh PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14668–14674. doi: 10.1021/ja051291k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xvii.Kusumi T, Hamada T, Ishitsuka MO, Ohtani I, Kakisawa H. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:1033–1035. [Google Scholar]

- xviii.The deterrent compounds, including amaroxocanes A and B segregated into a different polar extract prepared from P. amaranthus, and are the subjects of an earlier report. Morinaka BI, Pawlik JR, Molinski TF. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:259–264. doi: 10.1021/np800652v.

- xix.Hassan W, Edrada R, Ebel R, Wray V, Proksch P. Mar. Drugs. 2004;2:88–100. [Google Scholar]

- xx.The carbene, 2,3-dihydroimidazole-2-ylidene, is calculated to be 26.3 kcal.mol−1 higher in energy than its isomer, imidazole Maier G, Endres J. Eur. J. Chem. 1998:1571–1520. Freeman F, Lau DJ, Patel AR, Pavia PR, Willey JD. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2008;112:8775–8784. doi: 10.1021/jp8030286.

- xxi.(a) Arduengo AJ., III Acc. Chem. Res. 1999;32:913–921. [Google Scholar]; (b) Boehme C, Frenking G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:2039–2046. [Google Scholar]; (c) Heinemann C, Muller T, Apeloig Y, Schwartz H. ibid. 1996;118:2023–2038. [Google Scholar]

- xxii.(a) Paterson I, Perkins MV. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:1811–1834. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cossy J, Bauer D, Bellosta V. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:5909–5922. [Google Scholar]

- xxiii.Zhou G-X, Molinski TF. Mar. Drugs. 2003;1:46–53. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.