Abstract

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs), which are usually short basic peptides, are able to cross cell membranes and convey bioactive cargoes inside cells. CPPs have been widely used to deliver inside cells peptides, proteins, and oligonucleotides; however, their entry mechanisms still remain controversial. A major problem concerning CPPs remains their lack of selectivity to target a specific type of cell and/or an intracellular component. We have previously shown that myristoylation of one of these CPPs affected the intracellular distribution of the cargo. We report here on the synthesis of glycosylated analogs of the cell-penetrating peptide (R6/W3): Ac-RRWWRRWRR-NH2. One, two, or three galactose(s), with or without a spacer, were introduced into the sequence of this nonapeptide via a triazole link, the Huisgen reaction being achieved on a solid support. Four of these glycosylated CPPs were coupled via a disulfide bridge to the proapoptotic KLAK peptide, (KLAKLAKKLAKLAK), which alone does not enter into cells. The effect on cell viability and the uptake efficiency of different glycosylated conjugates were studied on CHO cells and were compared to those of the nonglycosylated conjugates: (R6/W3)S-S-KLAK and penetratinS-S-KLAK. We show that glycosylation significantly increases the cell viability of CHO cells compared to the nonglycosylated conjugates and concomitantly decreases the internalization of the KLAK cargo. These results suggest that glycosylation of CPP may be a key point in targeting specific cells.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12154-009-0031-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cell-penetrating peptide, Glycosylation, Click chemistry, Triazole, Apoptose

Introduction

The possibility for a highly basic peptide to enter into cells was viewed as an artifact for a long time, as this was in total contradiction with the established dogma on the impermeability of the plasma membrane to cationic species [1, 2]. Today, plethora of basic peptides which correspond to segments of natural proteins, synthetic peptides, or platforms have been described and are classified as cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) [3–6]. It has also been demonstrated that CPPs have the capacity to shuttle bioactive cargoes inside eukaryotic cells. The final localization in the cell of the CPP/cargo conjugates or complexes is undoubtedly associated with the mechanism of entry; however, the mechanism is still an ongoing matter of debate [7–17]. The capacity for CPPs to deliver a bioactive molecule inside of cells has opened avenues for intracellular pharmacology, and recently, significant advances have been accomplished for siRNA delivery and also for specific cellular targeting with homing peptides to name a few examples [16, 17].

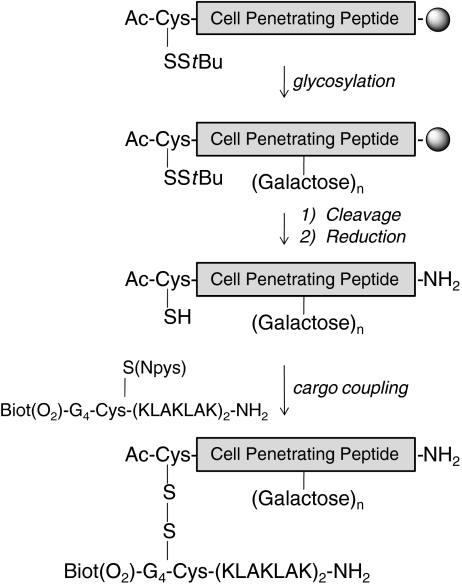

Our pioneering work on penetratin along with Alain Prochiantz’s team was started 15 years ago [7]. We have synthesized minimalist analogs of CPPs, and we have studied the effect of CPP myristoylation on the delivery of a peptide cargo [18]. This work has now led us to explore the influence of glycosylation on the cellular uptake, taking as a starting point our lead (R6/W3) CPP sequence [19–21]. Glycosylation of bioactive compounds has been used mainly for increasing either the hydrophilicity, the enzymatic stability of the compound, and/or its delivery into the brain [22–25]. In the context of CPPs, we have hypothesized that glycosylation may regulate and or affect the internalization of the corresponding glycosylated analogs of (R6/W3) [26–30]. According to the strategy depicted in Scheme 1, we have synthesized glycosylated analogs of (R6/W3), in which galactose unit(s) linked via click chemistry replace(s) one, two, or the three tryptophans. We have subsequently analyzed the viability of CHO cells treated by conjugates with the proapoptotic peptide KLAK, [31–33] and have visualized their localizations in these cells by fluorescence.

Scheme 1.

Schematic view depicting the strategy for the syntheses of CPP conjugates with the proapoptotic KLAK peptide. The CPP, without or with a Pra residue at the desired position, are assembled on a solid support by Fmoc strategy, the N-terminal residue being Ac-CysS-StBu. The galactose(s) moiety is introduced on the peptidyl-resin via click chemistry. Cleavage is performed on the solid support and followed by purification. The cysteine side chain is deprotected to conjugate the KLAK cargo, which contains an electrophilic cysteine (Cys-SNpys, Npys 3-nitropyridinesulfenyl). The CPP cargo conjugate is finally purified by HPLC

Results and discussion

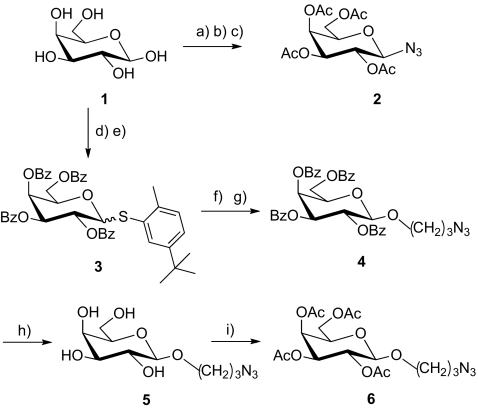

Syntheses of azido galactose analogs 2, 5, and 6

Two series of azido-functionalized galactose derivatives have been prepared: compound 2 with the azido group directly attached on the anomeric position of the tetra-acetylated galactose and analogs with a (O-CH2)3 spacer on the anomeric position, with either OBz 4, free OH 5, or OAc 6. The syntheses of these analogs are summarized in Scheme 2. The analog 1-azido-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-galactopyranoside 2 was prepared from galactose 1, as previously described [22]. The (2-methyl-5-tert-butylphenyl)-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-benzoyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside 3 was prepared, according to a strategy we developed recently in the mannose series, which turned out to be very convenient to modify the anomeric position [34]. Compound 3 was obtained with a good yield and was further reacted with 3-bromopropan-1-ol catalyzed by N-bromosuccinimide in the presence of triflic acid. This reaction was followed by a substitution to afford 3-azidopropyl-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-benzoyl-β-d-galactopyranoside 4. The benzoates were subsequently removed to yield 3-azidopropyl-β-d-galactopyranoside 5, which was then acetylated leading to 3-azidopropyl-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-galactopyranoside 6. It is worth mentioning that compound 6 may also be obtained from galactose 1, as previously described [35, 36].

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions a) Ac2O, dry pyridine, 99%; b) HBr/CH3COOH, CHCl3, 2 h, RT, 64%; c) NaN3, acetone, 60 °C, 94%; d) BzCl, dry pyridine, 0 °C, Argon; e) 2-Methyl-5-tert-butylthiophenol, BF3.Et2O, dry CH2Cl2, Argon, 74%; f) 3-bromo-propan-1-ol, NBS, TfOH, 4 Ǻ molecular sieves, dry CH2Cl2, Argon, 72%; g) NaN3, dry DMF, 60 °C, 81%; h) Na, dry MeOH, 82%; i) Ac2O, dry pyridine, 85%

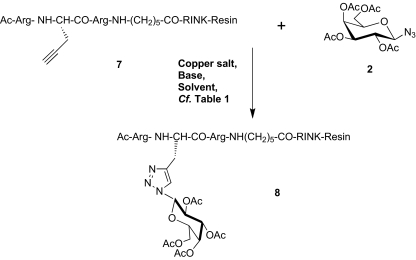

Click reaction on a solid support, general conditions with Ac-Arg-Pra-Arg-Ahx-Rink-amide resin

All of the glycopeptides synthesized are analogs of the CPP (R6/W3). One, two, or the three tryptophans of the (R6/W3) have been substituted by a protected or unprotected galactose-containing residue. Galactose moieties were covalently linked by a triazole linkage via the Huisgen reaction [37, 38]. Using the model tripeptide 7, Ac-Arg-Pra-Arg-Ahx-CONH2 (Pra standing for propargyl amino acid, Fmoc strategy), we first searched for the optimal conditions to couple the azidosugar to the propargyl residue on to the solid support. The glycosylated peptide Ac-Arg-[Pra(Gal(OAc)]-Arg-Ahx-CONH28 was obtained after cleavage from the resin with standard conditions (TFA/H2O/TIS), Scheme 3 (refer to Supplementary files). It is worth noting that these conditions are not detrimental to the carbohydrate and the triazole link [39, 40]. The reproducibility and sensitivity of IR analysis (alkyne signal at 2,200 cm−1) was not sufficient to monitor the reaction by taking aliquots of the resin [41, 42]. Azidorhodamine analog 9 (refer to Supplementary files), prepared from rhodamine B, exhibited fluorescence quenching (approximately ten times) when covalently linked via a triazole to the solid support, as previously reported [43]. This analog, therefore, cannot be used for the quantification of remaining Pra residues on the support. It should be noted that no quenching was observed when azidorhodamine analog 9 was dissolved in the same solvent in the presence of a Rink amide resin. The different glycosylated peptidyl-resin samples were cleaved from the solid support and analyzed by RP-HPLC. Triazole formation was found to be complete within 5 h with 2 eq. of sugar 2. Four eq. of Cu(OAc)2 or 2 eq. of CuI were efficient in the presence of 2 eq. of ascorbic acid and 5 eq. of diisopropylamine, in DMF containing 30% of either pyridine, lutidine, or piperidine. Five hours of coupling reaction time was estimated to be the best compromise for the equivalents of azido-sugar which were required for the reaction (refer to Supplementary files). Only the ß-anomer was detected in solution as demonstrated by NMR analysis (data not shown).

Scheme 3.

Optimization of the coupling reaction on to a solid support with a model peptidyl-resin. The model tripeptide, Ac-Arg-Pra-Arg-aminohexanoyl-resin, assembled on a Rink-amide resin, was used to optimize the conditions for coupling the azido galactose 2. The various parameters (copper salt, base, solvent, and coupling time) were analyzed; see Table 1 in Supplementary materials. The evolution of the coupling reaction (ratio of starting peptide vs peptide 8) was monitored after the cleavage from the resin and HPLC analysis. Triazole formation was complete within 5 h with 2 eq. of sugar 2. Four eq. of Cu(OAc)2 or 2 eq. of CuI were both efficient in the presence of 2 eq. of ascorbic acid and 5 eq. of diisopropylethylamine, in DMF containing 30% of pyridine, lutidine, or piperidine

Syntheses of the glycopeptide analogs of the cell-penetrating peptide (R6/W3)

Using these optimal conditions, all of the glycopeptides listed in Table 1 were synthesized, as described for the model glycopeptide 8, starting from the propargyl peptides 12, 13, or 14. Glycopeptides 15 and 16 contain one galactose unit, with acetylated or free OH, respectively, while 17 and 18 have two and three acetylated galactose units, respectively. Glycopeptide 19 possesses three galactose units, all OH being free. Glycopeptides 20–22 all have a single galactose unit with a propyl spacer between the sugar and the triazole, with either acetylated (20), benzoylated (21), or free OH (22). After cleavage from the Rink amide resin, all of the peptides were purified by RP-HPLC (for yields and characterization by MALDI–TOF mass spectrometry, refer to Supplementary files). It should be noted that the StBu-protecting group of the cysteine residue does not interfere with the Huisgen reaction, which required the presence of ascorbic acid to reduce Cu2+ to Cu+1 species. Galactose unit(s) in 15 and 18 was(were) de-O-acetylated using ammonia in methanol to give 16 and 19, respectively. During this deacetylation step, the S–StBu bond was partially cleaved, leading to a mixture of S–StBu peptides and the free thiol analogs, which were isolated and identified by MALDI–TOF mass spectrometry. Reduction by DTT was required for complete removal of StBu. The SH glycopeptides were then used in the coupling reaction with the cargo (see below).

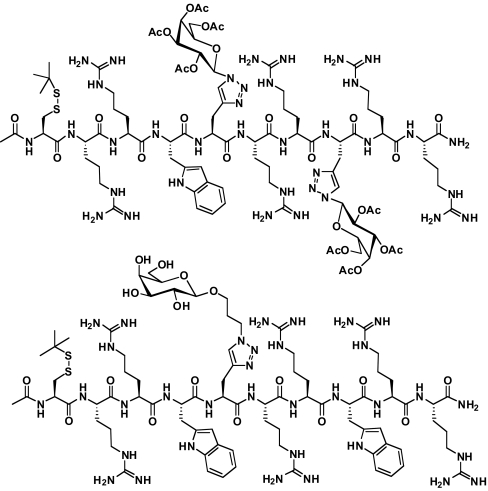

Fig. 1.

Two peptides from Table 2 are illustrated as examples. Top Ac-Cys(SStBu)-RRW-[Pra-Gal(OAc)]-RR-[Pra-Gal(OAc)]-RR-NH2, abbreviated in the text as (R6/W1)-[Pra-Gal(OAc)]2S-StBu, 17, and bottom Ac-Cys(SStBu)-RRW-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH)]-RRWRR-NH2, abbreviated in the text as (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH)]S-StBu, 22

Table 1.

Peptides sequences and abbreviations

| Peptides and primary sequences | Abbreviations |

|---|---|

| 10 Ac-C(SStBu)-RRWWRRWRR-NH2 | (R6/W3)S-StBu |

| 11 Ac-C-RRWWRRWRR-NH2 | (R6/W3)-SH |

| 12 Ac-C(SStBu)-RRW-Pra-RRWRR-NH2 | (R6/W2)-Pra-S-StBu |

| 13 Ac-C(SStBu)-RRW-Pra-RR-Pra-RR-NH2 | (R6/W1)-Pra2-S-StBu |

| 14 Ac-C(SStBu)-RR-Pra-Pra-RR-Pra-RR-NH2 | (R6/W0)-Pra3-S-StBu |

| 15 Ac-C(SStBu)-RRW-[Pra-Gal(OAc)]-RRWRR-NH2 (from click reaction of 12 with 2) | (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(OAc)]S-StBu |

| 16 Ac-C-RRW-[Pra(Gal-OH)]-RRWRR-NH2 (from de-O-acylation/reduction of 15) | (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]-SH |

| 17 Ac-C(SStBu)-RRW-[Pra-Gal(OAc)]-RR-[Pra-Gal(OAc)]-RR-NHa2 (from click reaction of 13 with 2) | (R6/W1)-[Pra-Gal(OAc)]2S-StBu |

| 18 Ac-C(SStBu)-RR-[Pra-Gal(OAc)]2-RR-[Pra-Gal(OAc)]-RR-NH2 (from click reaction of 14 with 2) | (R6/W0)-[Pra-Gal(OAc)]3S-StBu |

| 19 Ac-C-RR-[Pra(Gal-OH)]2-RR-[Pra-Gal(OH)]-RR-NH2 (from de-O-acylation/reduction of 18) | (R6/W0)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]3-SH |

| 20 Ac-C(SStBu)-RRW-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OAc)]-RRWRR-NH2 (from click reaction of 12 with 5) | (R6/W2)- [Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OAc)]S-StBu |

| 21 Ac-C(SStBu)-RRW-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OBz)]-RRWRR-NH2 (from click reaction of 12 with 4) | (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OBz)]S-StBu |

| 22 Ac-C(SStBu)-RRW-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH)]-RRWRR-NHa2 (from click reaction of 12 with 6) | (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH)]S-StBu |

| 23 Ac-C-RRW-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH)]-RRWRR-NH2 (from reduction of 22) | (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH)]-SH |

| 24 Ac-C-RRW-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OAc)]-RRWRR-NH2 (from reduction of 20) | (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OAc)]-SH |

Pra propargylglycine, Pra-Gal(OH) β-d-galactopyranoside triazole, Pra-Gal(OAc) 2,3,4,6-tetra-acetyl-Pra-Gal(OH), Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH) 3-(β-d-galactopyranosyloxy)propyl triazole, Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OAc) 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH), Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OBz) 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-benzyl-Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH)

aFig. 1

Syntheses of conjugates with the proapoptotic peptide KLAK

The proapoptotic peptide KLAK (KLAKLAKKLAKLAK) does not enter into cells and does not affect cell viability, but KLAK induces cell death when delivered to the mitochondria by a cell-penetrating peptide [31–33]. Four of the glycopeptides, 16, 19, 23, and 24, were conjugated through a labile disulfide linker to a biotinylated analog of KLAK: Biotin(O2)-(Gly)4-C(Npys)-KLAKLAKKLAKLAK-NH2, 25. The KLAK peptide was modified in the N-terminal region for further characterization of its cellular delivery either by fluorescence (biotin revealed with fluorescent streptavidin) and/or by mass spectrometry (1H-Gly or 2H-Gly) [46]. The activated protecting group of cysteine (Npys) allows for a rapid and efficient coupling to a thiol-containing peptide [18, 20, 44, 45]. Conjugates with (R6/W3) and penetratin (Ac-CRQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK-NH2) were also synthesized as references, molecules 26 and 32, respectively. The structures and characterizations of the different conjugates 26–29 are reported in Table 2 and in Supplementary files. It is interesting to note that in contrast to previous studies [45], the deprotection of the S–StBu glycopeptides was never complete with TCEP as indicated by HPLC even with higher amounts of TCEP and prolonged reaction times. However, reduction was quantitative using 20 equivalents of DTT in Tris–HCl buffer.

Table 2.

Glycopeptides conjugated to the KLAK peptides

| Number—peptides |

|---|

| 26—(R6/W3)S-S-KLAK |

| 27—(R/6W2)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]S-S-KLAK |

| 28—(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH)]S-S-KLAK |

| 29—(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OAc)]S-S-KLAK |

| 30—(R6/W0)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]3S-S-KLAK |

Cell viability studies

In this study, we have focused our analysis on the activity of the various KLAK conjugates, inferring that cell death should be related to the uptake efficiency of the conjugates. The CCK8 cell counting kit was used to quantify the extent of dead cells at the end of 2 h incubation with CHO-K1 cells. The viability of the cells incubated with the glycosylated conjugates were compared to those of the KLAK conjugates with penetratin, 32, and (R6/W3), 26, and of the free cargo Biotin(O2)-(Gly)4-Cys(Acm)-KLAKLAKKLAKLAK-NH231. The thiol function of this KLAK analog was masked with an acetamidomethyl group. We have recently demonstrated that the activated SH protecting group may contribute to the internalization of peptides by cell surface thiol/disulfide exchange [45].

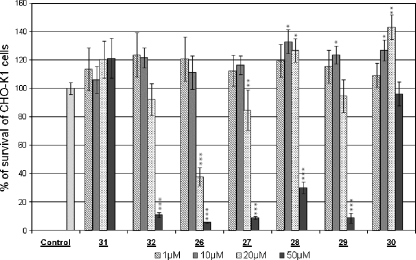

Penetratin, (R6/W3), and the glycosylated CPPs (at 50 μM; data not shown) and the KLAK cargo 31 did not decrease the number of viable cells even at 50 μM, the highest concentration which was used. It has been previously demonstrated with other KLAK analogs or with other cell lines that KLAK peptides are unable to cross the bilayer of eukaryotic cells unless they are coupled to a CPP [31] or a scaffold [32], which shuttle KLAK inside cells. The extent of cell death induced by all of the CPP-KLAK conjugates tested herein is reported in Fig. 2. The conjugates penetratin-S-S-KLAK, 32, and (R6/W3)S-S-KLAK, 26, induced cell death of CHO-K1 cells, the latter being significantly more potent. The free CPPs penetratin and (R6/W3) were found previously to be internalized in CHO cells with the same efficiency when quantified by mass spectrometry and penetratin was slightly more efficient to deliver a peptide inhibitor of protein kinase C [18, 45]. All of the glycoconjugates, 27–30 were found to be less active than the nonglycosylated reference conjugate (R6/W3)S-S-KLAK 26. (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]S-S-KLAK 27 which was already significantly active at 20 μM. This glycoconjugate was more potent in inducing cell death than the three other glycosylated conjugates. The introduction of a propyl spacer between the CPP and the galactose unit decreased the conjugate activity. The glycoconjugate (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH)]S-S-KLAK 28 was found to induce cell death only at the higher concentration used (50 μM). The difference in the efficacies of conjugates 27 and 28 is significant at 20 μM (P = 0.04) and extremely significant at 50 μM (P = 0.0004). Interestingly, acetylation of galactose is associated with a decrease in cell viability, as shown with analog 29, (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OAc)]S-S-KLAK. The difference between the efficiencies of conjugates 28 and 29 is very significant at 50 μM (P = 0.008). It is interesting to note that the conjugate with the three galactoses, (R6/W0)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]3S-S-KLAK, 30, does not affect cell viability even at 50 μM.

Fig. 2.

Cell viability experiments were expressed as a percentage of living CHO-K1 cells. Adherent CHO cells (10,000 cells per well) were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C with various concentrations of CPP-KLAK conjugates, from left to right: 1, 10, 20, and 50 μM of conjugate (compounds 31, Biotin(O2)-(Gly)4-Cys(Acm)-KLAKLAKKLAKLAK-NH2; 32, penetratinS-S-KLAK; 26, (R6/W3)S-S-KLAK; 27, (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]S-S-KLAK; 28, (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH)]S-S-KLAK; 29, (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OAc)]S-S-KLAK; and 30, (R6/W0)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]3S-S-KLAK). After incubation, the supernatant was removed; a solution of CCK8 cell counting kit was added, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm after 2 h. Results are expressed as the average of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate; differences (Student’s test) being * significant, ** very significant, and *** extremely significant from control value (100%). Only the free KLAK peptide and the conjugate with three galactose units 30 (R6/W0)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]3S-S-KLAK did not affect the cell viability, even at 50 μM

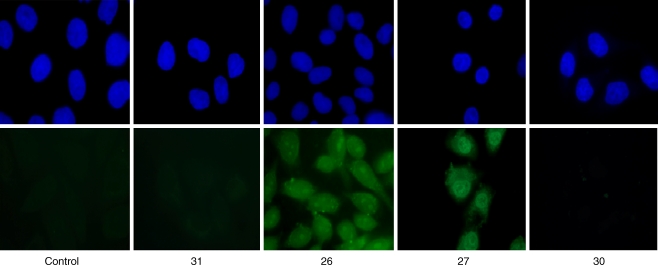

Fluorescence labeling of CHO-K1 cells incubated with KLAK, 31, or KLAK conjugates, 26, 27, 30

The delivery and intracellular localization of the KLAK cargo into cells were studied by fluorescence. The alternative for such studies is to use either fluorescent peptides and live cells or biotinylated peptides and fixed cells. The biotinylated peptide is revealed by fluorescent streptavidin. Both of these strategies require modifications of the peptide and have inherent drawbacks. On the one hand, it has been suggested that CPPs tend to diffuse during cell fixation [47, 48]. On the other hand, functionalization with large hydrophobic fluoroprobes may affect the peptide uptake mechanism and its final localization, more than biotin, a smaller size tag (data to be published, S. Aubry et al.). A procedure with fixed cells was set up to discriminate the internalized peptide from the membrane-bound peptide [49]. This procedure minimized the artifact due to an eventual diffusion of the peptide, as the membrane-bound cargo was first quenched with unlabeled avidin to visualize only the internalized species. The cells were subsequently fixed with paraformaldehyde and permeabilized. The intracellular biotinylated cargo was revealed with fluorescent Alexa-488-streptavidin. It is worth mentioning that the fluorescent streptavidin will label the conjugated with KLAK as well as the free KLAK peptide that is released after reduction with glutathione in the cytosol. The free KLAK cargo 31 and glycoconjugates (R6/W3)S-S-KLAK 26, (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]S-S-KLAK 27 and (R6/W0)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]3S-S-KLAK 30 were analyzed with this procedure. These compounds were incubated at a concentration (10 or 20 μM; Fig. 3) where their respective activity killed only part of the CHO cells. No fluorescence was detected when CHO-K1 cells were incubated with the free KLAK cargo 31, showing that KLAK was not internalized alone and corroborating its lack of effect on cell viability. The fluorescent labelings observed with the conjugates 26, 27, and 30 have also corroborated their activities on cell viability. Conjugate 30 did not label any cell and did not lead to cell death (Fig. 2).

Fig. 3.

The biotinylated internalized cargo was visualized by confocal microscopy. The CPP-KLAK conjugates were incubated for 2 h at a single concentration: 10 μM (conjugate 26) or 20 μM (KLAK, conjugates 27 and 30). No peptide was incubated in the control experiment. After incubation, the membrane-bound cargo was quenched with avidin. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton ×100. The intracellular cargo was then visualized with fluorescent streptavidin (streptavidin-Alexa488, in green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (in blue). These experiments were duplicated which lead to comparable images in all cases. Cargo delivery inside cells was observed only when using (R6/W3) and (R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(OH)] carriers. No intracellular KLAK was detected with the carrier bearing three galactose units

Rothbard et al. have proposed (Arg)n (with n as being up to 16 residues) as a powerful CPP, showing that the short analogs (n = 6–8) were still potent [50, 51]. In a subsequent study, they modified the decapeptide (Arg)10 by systematically replacing with other amino acids the three arginines which project on the same side of a 310 helical structure (i.e., the second, fifth, and eighth positions). Only the introduction of either an aspartic acid or a glutamic acid (seven arginines and three acidic residues in the sequence) induced a drastic decrease in the internalization efficiency of the corresponding peptides. In contrast, decamers with seven arginines and three serines or threonines (residues with hydroxylated side chains) were as potent as (Arg)10 [52]. The data produced herein show that the viability of the cells incubated with KLAK conjugates is closely related to conjugate internalization. The conjugate with three galactoses did not affect cell viability, and no internalized KLAK peptide was observed by fluorescence with this glycoconjugate. It is worth mentioning that this conjugate should not be metabolized faster than its corresponding unglycosylated conjugate, as it has been proposed that glycosylation generally increases peptide stability [53, 54]. Thus, the presence of carbohydrate(s) decrease the capacity of the glycosylated CPP cargo conjugate to enter cells, in contrast to serine or threonine residues. This conclusion applies even though (Arg)6 is still efficiently taken up into cells [50, 51], and the glycosylated CPPs reported here have six arginines in their sequences.

Noticeably, CPPs have been designed either starting from carbohydrate synthons [55] or with both carbohydrates on one part of a construct and basic side-chains on the other part [56]. All of these glycosylated analogs were efficiently taken up into cells [55, 56]. The glycosylated CPP designed herein with three carbohydrate moieties is not internalized. Thus, depending on the “place/spatial organization” of the carbohydrates and basic chains on the final synthon, the uptake efficiency is or is not affected. It is difficult to correlate the uptake efficiency of the glycosylated conjugate described in this study to a significant variation in the hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity balance of the starting CPP (R6/W3). If the HPLC retention time of the glycosylated conjugates is taken into consideration as an overall index of the relative hydrophilicity, monogalactosylation shows a slight increase in hydrophilicity, whereas trigalactosylation led to a slight increase in hydrophobicity, when compared to the (R6/W3) conjugate. One might be tempted to propose that the glycoconjugates with galactoses (especially the one with three galactoses) may bind to some extracellular component competing/impairing the interactions of guanidiniums with either heparan sulfates or lipids, which are necessary for cellular uptake independent of the entry mechanism. This extracellular binding does not lead to a rapid intracellular delivery during the 2 h of incubation time. The absence of intracellular labeling also proves that the glycoconjugate was not subjected to significant disulfide exchange with thiolated proteins present on the cell membrane. As recently shown by Aubry et al., these thiol functions are involved in the extracellular transfer of some disulfide-bridged peptides. [45].

From this study, one must conclude that the introduction of galactose(s) per se in the sequence of a CPP affects the intracellular delivery. We have shown that glycosylation with three galactoses of a cationic peptide (with six arginines) yielded peptides unable to enter into cells. The exact reason for this decreased efficiency remains to be unveiled at the molecular level. This apparent “negative result” (inactive CPPs) must in fact be considered as an opportunity to regulate the internalization of bioactive molecules and provides an insight into addressing CPPs, which still remains a crucial problem. We can theorize that glycosylation via an immolative linker between a CPP and a carbohydrate may yield a more specific addressing to cells. In this framework, a specific linker between the peptide and the carbohydrate residues, which is designed to be cleaved in the environment of tumor cells, must allow a selective internalization inside of these cells for the CPP and the shuttled drug.

Experimental section

1-Azido-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-galactopyranoside, 2

Prepared in two steps from galactose 1, as previously described [22].

(2-Methyl-5-tert-butylphenyl) 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-benzoyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, 3

To a solution of 1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-benzoyl-d-galactopyrannose (4.0 g, 5.71 mmol) prepared from galactose 1 [34] in anhydrous dichloromethane (10 mL) were added, under argon, 2-methyl-5-tert-butylthiophenol (1.35 mL, 6.85 mmol, 1.2 eq.) and BF3.Et2O (3.62 mL, 28.54 mmol, 5 eq.). An orange solution is obtained in a few minutes after the addition of BF3.Et2O. The reaction was monitored by TLC (cylohexane-ethyl acetate 7:3). After 16 h, the reaction was complete. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C then precautiously neutralized with a saturated NaHCO3 solution. The product was extracted with CH2Cl2; the combined organic layers were dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (cyclohexane/EtOAc, 9:1 then 8:2) to afford 3 (3.22 g, 74%) as a white foam containing two anomers (α, β 25:75). α anomer: Rf = 0.48 (cyclohexane/EtOAc, 8:2). [α]25D 151.7 (c 1.0, CHCl3); 1H NMR (250 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.12–8.03 (m, 4H, HAr ortho), 7.94–7.91 (m, 2H, HAr ortho), 7.85–7.82 (m, 2H, HAr ortho), 7.63–7.32 (m, 13H, HAr), 7.16 (dd, 1H, HAr, J = 1.9 Hz, J’ = 8.0 Hz), 7.06 (d, 1H, HAr, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.25 (d, 1H, H1, JH1–H2 = 4.9 Hz), 6.17–6.16 (m, 1H, H4), 6.06–5.94 (m, 2H, H3+H2), 5.22–5.17 (m, 1H, H5), 4.59 (dd, 1H, H6a, JH6a–H5 = 6.5 Hz, JH6a–H6b = 11.4 Hz), 4.44 (dd, 1H, H6b, JH6b–H5 = 6.5 Hz), 2.32 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.21 (s, 9H, tBu); 13C NMR (62.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 165.7, 165.5, 165.4 (4 C=O), 149.8–124.9 (30 CAr), 86.5 (C1), 69.1, 68.9 (C4+C3+C2), 68.1 (C5), 62.2 (C6), 34.3 (C(CH3)3), 31.1 (C(CH3)3), 20.2 (CH3); MS ESI+-HRMS (m/z) calculated for C45H42NaO19S: 781.24417, found 781.24353. β anomer: Rf = 0.44 (cyclohexane/EtOAc, 8:2). [α]25D 101.0 (c 1.0, CHCl3); 1H NMR (250 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.02–7.97 (m, 6H, HAr ortho), 7.78 (dd, 2H, HAr ortho, JHortho-Hméta = 7.1 Hz, JHortho–Hpara = 1.4 Hz), 7.63–7.36 (m, 12H, HAr), 7.30–7.21 (m, 2H, HAr), 7.14 (d, 1H, HAr, J = 7.9 Hz), 6.02 (d, 1H, H4, JH4–H3 = 3.1 Hz), 5.86 (t, 1H, H2, JH2–H1 = JH2–H3 = 9.9 Hz), 5.61 (dd, 1H, H3), 4.98 (d, 1H, H1), 4.65 (dd, 1H, H5, JH5–H6a = 5.9 Hz, JH5–H6b = 10.8 Hz, 4.44–4.30 (m, 2H), 2.33 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.23 (s, 9H, tBu); 13C NMR (62.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 166.3, 165.8, 165.5 (4 C=O), 149.8–126.2 (30 CAr), 88.1 (C1), 75.1 (C5), 73.2 (C3), 68.7, 68.6 (C4+C2), 62.5 (C6), 34.5 (C(CH3)3), 31.4 (C(CH3)3), 20.9 (CH3); MS ESI+-HRMS (m/z) [MNa]+ calculated for C45H42NaO19S: 781.24417, found 781.24352.

3-Azidopropyl-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-benzoyl-β-d-galactopyranoside, 4

3-Azidopropyl-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-benzoyl-β-d-galactopyranoside, 4 was prepared in two steps from compound 3via 3-bromopropyl-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-benzoyl-β-d-galactopyranoside. To a solution of (2-methyl-5-tert-butylphenyl)-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-benzoyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside 3 (3.14 g, 4.13 mmol) in dry dichloromethane (10 mL), under argon, were added 4 Å molecular sieve (3.10 g), 3-bromopropanol (540 µL, 6.20 mmol, 1.5 eq.), N-bromosuccinimide (1.47 g, 8.26 mmol, 2 eq.), and trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (44 µL, 0.41 mmol, 0.1 eq.). The reaction mixture was stirred under an argon atmosphere for 15 min at room temperature and was then filtered over celite. The filtrate was washed first with a saturated solution of Na2S2O3 (10 mL) and then with a saturated solution of NaHCO3 (10 mL). The product was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 15 mL). The combined organic layers were dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated in vacuo to give a yellow syrup, which was purified by flash column chromatography (cyclohexane/EtOAc, 9:1 then → 8:2) to yield 2.14 g (72% yield) of product as a white foam. Rf = 0.28 (cyclohexane/EtOAc, 8:2); [α]25D 87.8 (c 1.0, CHCl3); 1H NMR (250 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.01 (d, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.94 (d, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.89 (d, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.71 (d, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.55–7.12 (m, 12H, HAr), 5.93 (d, 1H, JH4–H3 = 3.1 Hz, H4) 5.72 (dd, 1H, JH2–H3 = 10.3 Hz, JH2–H1 = 7.9 Hz, H2), 5.55 (dd, 1H), 4.78 (d, 1H, H1), 4.62 (dd, 1H, JH6a–H6b = 10.7 Hz, JH6a–H5 = 6.1 Hz, H6a), 4.38–4.25 (m, 2H, H6b+H5), 4.04–3.98 (m, 1H, OCHaHb), 3.71–3.66 (m, 1H, OCHaHb), 3.30–3.24 (m, 2H, CH2Br), 2.08–1.92 (m, 2H, OCH2CH2CH2Br); 13C NMR (62.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 166.1, 165.6, 165.4 (C=O), 133.6–128.3 (24 CAr), 102.0 (C1), 71.7 (C3), 71.4 (C5), 69.8 (C2), 68.2 (C4), 67.7 (OCH2CH2CH2Br), 62.1 (C6), 32.4 (OCH2CH2CH2Br), 30.1 (OCH2CH2CH2Br). MS FAB+-HRMS (m/z) [MNa]+ calculated for C37H33O10BrNa: 739.1155, found 739.1182.

To a solution of 3-bromopropyl-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-benzoyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (2.04 g, 2.85 mmol) in dry DMF (30 mL), under argon, sodium azide (1.11 g, 17.10 mmol, 6 eq.) was added. The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 3 h, and the solvent was evaporated. The residue was diluted in CH2Cl2 (20 mL), washed with water (3x15mL), dried (MgSO4), filtered, and evaporated in vacuo. The crude material was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (cyclohexane/EtOAc 8:2) to give 1.57 g of 4 (81% yield), isolated as a white foam. Rf = 0.23 (cyclohexane/EtOAc, 8:2); [α]25D 89.0 (c 1.0, CHCl3); 1H NMR (250 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.01–7.68 (m, 8H, HAr ortho), 7.59–7.13 (m, 12H, HAr), 5.93 (d, 1H, JH4–H3 = 3.1 Hz, H4), 5.72 (dd, 1H, JH2–H3 = 10.4 Hz, JH2–H1 = 7.9 Hz, H2), 5.54 (dd, 1H), 4.75 (d, 1H, H1), 4.62 (dd, 1H, JH6a–H6b = 10.9 Hz, JH6a–H5 = 6.3 Hz), 4.38–4.26 (m, 2H, H6b+H5), 4.01–3.97 (m, 1H, OCHaHb), 3.67–3.52 (m, 1H, OCHaHb), 3.21–3.16 (m, 2H, CH2N3), 1.77–1.73 (m, 2H, OCH2CH2CH2N3); 13C NMR (62.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 166.1, 165.6, 165.3 (C=O), 133.6–128.3 (24 CAr), 101.8 (C1), 71.7 (C3), 71.4 (C5), 69.8 (C2), 68.1 (C4), 66.8 (OCH2CH2CH2N3), 62.0 (C6), 47.9 (OCH2CH2CH2N3), 29.0 (OCH2CH2CH2N3); MS FAB+-HRMS (m/z) [MNa]+ calculated for C37H33O10N3Na: 702.2064, found 702.2059.

3-Azidopropyl-β-d-galactopyranoside, 5

To a suspension of 3-azidopropyl-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-benzoyl-β-d-galactopyranoside 4 (1.0 g, 1.47 mmol) in anhydrous methanol (15 mL), under argon, was added sodium (23 mg, 1.0 mmol). The suspension slowly disappeared; the reaction was complete after 15-h stirring (TLC: cyclohexane/EtOAc, 7:3). The clear solution was neutralized by adding a cation exchange resin (IR 120-H+ form) previously treated by successive washings with H2O (3 × 20 mL) and MeOH (3x20mL). After filtration, the filtrate was concentrated to give an oil, which was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1) to give 315.6 mg of 5 (82% yield), isolated as a pale yellow syrup. Rf = 0.2 (EtOAc/MeOH, 9:1); [α]25D -5.3 (c 1.0, DMSO); 1H NMR (250 MHz, MeOD) δ: 4.24 (d, 1H, JH1–H2 = 6.8 Hz, H1), 4.04–3.95 (m, 1H, OCHaHb), 3.86 (d, 1H, JH3–H2 = 2.2 Hz, H3), 3.77 (d, 1H, J = 2.0 Hz, H6b), 3.75 (s, 1H, H6a), 3.71–3.62 (m, 1H, OCHaHb), 3.58–3.45 (m, 5H, CH2N3+H2+H4+H5), 1.94–1.84 (m, 2H, OCH2CH2CH2N3); 13C NMR (62.5 MHz, MeOD) δ: 105.1 (C1), 76.6, 74.9, 72.5, 70.3 (C3), 67.6 (OCH2CH2CH2N3), 62.5 (C6), 49.4 (OCH2CH2CH2N3), 30.3 (OCH2CH2CH2N3), Lit. [57]; MS FAB+-HRMS (m/z) [MNa]+ calculated for C9H17O6N3Na: 286.10096, found 286.10078.

3-Azidopropyl-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-galactopyranoside, 6

To a solution of 3-azidopropyl-β-d-galactopyranoside 5 (157.8 mg, 0.60 mmol) in anhydrous pyridine (2.5 mL) was added acetic anhydride (395 µL, 4.20 mmol, 7 eq.) under argon. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. Pyridine was then evaporated, and the residue was diluted in dichloromethane, washed with diluted H2SO4 (1 M; 2 × 5 mL) and then with a saturated solution of NaHCO3. The combined organic layers were dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude material was purified by flash column chromatography (cyclohexane/EtOAc, 7:3) to give 220.6 mg of 6 (85% yield), isolated as an oil. Rf = 0.25 (cyclohexane/EtOAc, 7:3); [α]25D 0.28 (c 1.0, CHCl3); 1H NMR (250 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 5.33 (d, 1H, JH4–H3 = 3.1 Hz, H4), 5.13 (dd, 1H, JH2–H3 = 10.4 Hz, JH2–H1 = 7.9 Hz, H2), 4.96 (dd, 1H, H3), 4.42 (d, 1H, H1), 4.13–4.03 (m, 2H, H6a+H6b), 3.95–3.87 (m, 2H, H5+OCHaHb), 3.59–3.50 (m, 1H, OCHaHb), 3.32 (t, 2H, J = 6.3 Hz, CH2N3), 2.09 (s, 3H, CH3 Ac), 2.01 (s, 3H, CH3 Ac), 1.99 (s, 3H, CH3 Ac), 1.92 (s, 3H, CH3 Ac), 1.86–1.73 (m, 2H, OCH2CH2CH2N3); 13C NMR (62.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 101.2 (C1), 70.8 (C3), 70.6 (C5), 68.7 (C2), 66.9 (C4), 66.4 (OCH2CH2CH2N3), 61.2 (C6), 47.8 (OCH2CH2CH2N3), 29.6 (OCH2CH2CH2N3), 20.6 (4CH3 Ac), Lit. [35]; MS FAB+-HRMS (m/z) [MNa]+ calculated for C17H25N3NaO10: 454.14322, found 454.14252.

Azido-propyl-rhodamine, 9

To a CH2Cl2 solution of rhodamine B (75.0 mg, 0.157 mmol) was added EDC.HCl (90.0 mg, 0.471 mmol, 3 eq.) followed by N-hydroxysuccinimide (54.2 mg, 0.471 mmol, 3 eq.) [58]. The reaction mixture was stirred for 0.5 h at room temperature, before dropwise addition of 3-azido-1-propanol [58] (79.0 mg, 0.783 mmol, 5 eq.), and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (1.95 mg, 0.016 mmol, 0.1 eq.) in CH2Cl2. The reaction was stirred at room temperature overnight, after dilution in CH2Cl2 the solution was washed with H2O (3×). The organic layer was dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated under vacuum. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH: 9/1) to give 58.0 mg of rhodamine-N39 as an oil (66%). 1H NMR (250 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.25 (m, 1H, HAr), 7.79 (m, 2H, HAr), 7.31 (s, 1H, HAr), 7.05 (m, 2H, HAr), 6.85 (m, 2H, HAr), 6.75 (m, 2H, HAr), 4.10 (t, 2H, J = 6.0 Hz, CH2), 3.65 (q, 8H, J = 8.0 Hz, CH2CH3), 3.20 (t, 2H, J = 6.1 Hz, OCH2CH2CH2N3), 1.69 (t, 2H, J = 6.0 Hz, CH2), 1.47 (t, 12H, J = 8.0 Hz, CH2CH3); 13C NMR (62.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 166.0 (C=O), 158.9–155,4 (6 CAr), 133.3–129.5 (8 CAr), 114.2 (2 CAr), 113.3 (CAr), 96.2 (CAr), 62.4 (OCH2CH2CH2N3), 47.8 (OCH2CH2CH2N3), 46.0 (2*N(CH2CH3)2), 27.7 (OCH2CH2CH2N3), 12.5 (2*N(CH2CH3)2). MS MALDI–TOF (m/z) [M]+ calculated for C31H36N5O3: 526.28, found 526.28.

Peptides syntheses

MBHA resin LL (100–200 mesh)-HCl, (4-methylbenzhydrylamine-hydrochloride polystyrene resin, 0.59 mmol/g), Rink amide MBHA resin (100–200 mesh) (4-(2′-4′-diméthoxyphenyl-Fmoc-aminomethyl)-phenoxyacetamido-norleucyl-MBHA polystyrene resin, 0.64 mmol/g), O-(benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU), Fmoc-Cys(tBuS)-OH, Fmoc-Arg(Pbf)-OH, Fmoc-Trp(Boc)-OH, Boc-Ala-OH, Boc-Leu-OH, and Boc-Lys(2-Cl-Z)-OH were purchased from Novabiochem. Boc-Gly-OH was purchased from Senn Chemicals, Boc-Cys(Npys)-OH from Bachem, and Fmoc-Pra-OH from IRIS Biotech. Other reagents for amino acid couplings were obtained from Applied Biosystems. Biotin(O2) was prepared from biotin as previously described in the literature [59]. Peptides were characterized by MALDI–TOF MS (DE-Pro, PerSeptive Biosystems) in positive ion reflector mode using the matrix CHCA. The m/z of the protonated molecule (first isotope) are given as experimental (calculated) and theoretical (found).

Model peptide: Ac-Arg-Pra-Arg-Ahx-NH2, 7 The tripeptide was synthesized manually by solid-phase methodology on a Rink amide resin (0.64 mmol/g) by Fmoc strategy. Fmoc protection was removed with a solution of piperidine in NMP (20%, 3 × 5 min). Stepwise coupling reactions were performed with Fmoc-protected amino acids, HBTU, and DIPEA (3/2.85/3 eq.) at RT. After removal of the last Fmoc protecting group, the peptide was N-acetylated with a solution of acetic anhydride in NMP (20%, 45 min). The resin was washed with NMP, CH2Cl2, MeOH and dried under vacuum. For analysis, approximately 5 mg of the resin were treated with TFA/H2O/TIS: 95/2.5/2.5 (15 mL/g resin, 2 h, RT), precipitated in diethyl ether, lyophilized and purified by RP-HPLC on a C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA). Retention time of the product was 8 min (0–95% acetonitrile over 30 min). The peptide was characterized by MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated 580.37, found 580.38.

Click chemistry with the model tripeptide Ac-Arg-Pra-Arg-Ahx-Rink-amide resin

To the dry resin-bound Ac-R-Pra-R-Ahx-Rink (Ahx: aminohexanoic acid) in a fritted syringe were added Cu(OAc)2 or CuI, ascorbic acid (in a 1:2 ratio with Cu(OAc)2 and a 1:1 ratio with CuI salt) and a solution containing 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-galactopyranosyl azide 2 (0.06 M), DIEA in a solution of 30% lutidine, pyridine or piperidine in DMF, (Refer to supplementary materials for the equivalents of Cu salt, and DIEA used). The solution was sonicated for 5 min and shaken at RT. The resin was then washed with DMF, DMF/pyridine (6/5) containing ascorbic acid (0.02 g/mL), CH2Cl2 and MeOH. The resin was dried and then cleaved by TFA/H2O/TIS: 95/2.5/2.5 (15 mL/g resin, 2 h, RT), precipitated in diethyl ether, lyophilized and purified by RP-HPLC on a C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA). Retention time of the product was 10 min (0–95% acetonitrile over 30 min). Conversion of the reaction was determined by RP-HPLC. The final glycopeptide 8 was characterized by MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated 953.48, found 953.48.

Coupling of azido-propyl rhodamine to Ac-Arg-Pra-Arg-Ahx-Rink-amide resin

To the dry resin-bound model peptide in a fritted syringe were added Cu(OAc)2 (40 eq.), ascorbic acid (40 eq.) and a solution containing Rhodamine-N39 (20 eq.), DIEA (50 eq.) in a solution of 30% pyridine in DMF. The solution was sonicated for 5 min and shaken at RT. The resin was then washed with DMF, DMF/Pyridine (6/5) containing ascorbic acid (0.02 g/mL), CH2Cl2 and MeOH. The resin was dried and then cleaved by treatment with TFA/H2O/TIS: 95/2.5/2.5 (15 mL/g resin, 2 h, RT), precipitated in diethyl ether, lyophilized and purified by RP-HPLC on a C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA). The peptide was characterized by MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [M]+ calculated 1,105.64, found 1,105.64.

(R6/W3)-S-StBu, 10 The peptide was synthesized manually by solid-phase methodology on a Rink amide resin (0.64 mmol/g) by Fmoc strategy in a fritted syringe. Fmoc protection was removed with a solution of piperidine in NMP (20%, 3x5 min). Stepwise coupling reactions were performed with Fmoc-protected aminoacids, HBTU and DIPEA (3/2.85/3 eq.) at RT. After removal of the last Fmoc protecting group, the peptide was N-acetylated with a solution of acetic anhydride in NMP (20%, 45 min). The resin was washed with NMP, CH2Cl2, and MeOH and dried under vacuum. The resin was then treated with TFA/H2O/TIS: 95/2.5/2.5 (15 mL/g resin, 2 h, RT), precipitated in diethyl ether, lyophilized, and purified by RP-HPLC on a preparative C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA) to yield the product as a white powder after lyophilisation (14% yield). The purity of the peptide was determined by analytical RP-HPLC on a C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA). Retention time of the product was 17 min (15–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). The peptide was characterized by MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated 1,744.93, found 1,744.94.

Syntheses of Pra-containing R/W peptides

The peptides were synthesized manually by solid-phase methodology on a Rink amide resin (0.64 mmol/g) by Fmoc strategy in a fritted syringe, as described for the model tripeptide Ac-R-Pra-R-Ahx-NH2. For analysis, approximately 5 mg of the resin were treated with TFA/H2O/TIS: 95/2.5/2.5 (15 mL/g resin, 2 h, RT), precipitated in diethyl ether, lyophilized, and purified by RP-HPLC on a C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA; 0–95% acetonitrile over 30 min). Pure peptides were characterized by MALDI–TOF MS.

(R6/W2)-Pra-S-StBu, 12 RP-HPLC retention time is 12.5 min (15–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [M,H]+ calculated is 1,654.89, and found 1,654.82.

(R6/W1)-Pra2-S-StBu, 13 RP-HPLC retention time is 12.9 min (15–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 1,563.85, found 1,563.56; [M2H]2+ calculated is 782.43, found 782.26.

(R6/W0)-Pra3-S-StBu, 14 RP-HPLC retention time is 9.9 min (15–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 1,472.81, found 1,472.80.

Syntheses of the glycosylated peptides

In a fritted syringe were added, to the corresponding dried Pra containing-peptidyl-resin, Cu(OAc)2 (4 eq.), ascorbic acid (2 eq.), and a solution of DMF/pyridine (7/3) containing the azido-sugar (two equivalents relative to Pra aminoacid, 0.06 M) and DIPEA (5 eq.). The solution was sonicated for 5 min and shaken for 15 h at RT. The resin was then washed with DMF, DMF/Pyridine (6/5) containing ascorbic acid (0.02 g/mL), CH2Cl2, and MeOH. The resin was dried under vacuum and then cleaved by TFA/H2O/TIS: 95/2.5/2.5 (15 mL/g resin, 2 h, RT). Analytical RP-HPLC showed complete conversion of the peptide into the glycopeptide. The crude glycopeptide was precipitated in diethyl ether, lyophilized, and purified by RP-HPLC on a preparative C8 column using a linear gradient of acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA). Peptide purity was analyzed by analytical RP-HPLC with a C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA) and characterized by MALDI–TOF MS.

(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(OAc)]-S-StBu, 15 RP-HPLC retention time is 14.5 min (15–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 2,028.00, found 2,027.96. Overall yield (peptide synthesis, click chemistry, and purification) is 3.0% with a purity >95%.

(R6/W1)-[Pra-Gal(OAc)]2-S-StBu, 17 RP-HPLC retention time is 18 min (10–60% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 2,310.07, found 2,309.83; [M2H]2+ calculated is 1,155.54, found 1,155.88. Overall yield (peptide synthesis, click chemistry, and purification) is 4.5% with a purity >95%.

(R6/W0)-[Pra-Gal(OAc)]3-S-StBu, 18 RP-HPLC retention time is 18.2 min (10–60% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 2,592.14, found 2,591.87; [M2H]2+ calculated is 1,296.57, found 1,296.90. Overall yield (peptide synthesis, click chemistry, and purification) is 7.5% with a purity >95%.

(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OAc)]-S-StBu, 20 RP-HPLC retention time is 14.5 min (15–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated 2,086.04, found 2,085.92. Overall yield (peptide synthesis, click chemistry, and purification) is 4.8% with a purity >95%.

(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OBz)]-S-StBu, 21 RP-HPLC retention time is 24.0 min (15–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 2,334.11, found 2,334.38. Overall yield (peptide synthesis, click chemistry, and purification) is 2.3% with a purity >95%.

(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH)]-S-StBu, 22 RP-HPLC retention time is 9.7 min (15–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 1,918.00, found 1,917.59. [M2H]2+ calculated is 959.51, found 959.79. Overall yield (peptide synthesis, click chemistry, and purification) is 3.4% with a purity >95%.

Reduction of the t-buthio disulfide

To the disulfide peptide dissolved in a degassed solution of Tris–HCl 50 mM (∼2 mM), DTT (20 eq.) was added, and the reaction was stirred at RT for 2 h. Crude thiol peptides were then purified by RP-HPLC on a preparative C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA). Peptide purity was analyzed by analytical RP-HPLC on a C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA) and characterized by MALDI–TOF MS.

(R6/W3)-SH, 11 RP-HPLC retention time is 11.7 min (15–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 1,657.90, found 1,658.00. Yield is 87% with a purity >95%.

(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH)]-SH, 23 RP-HPLC retention time is 7.0 min (15–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 1,829.97, found 1,829.71. Yield is 46% with a purity >95%.

(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OAc)]-SH, 24 RP-HPLC retention time is 10.5 min (20–60% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 1,998.00, found 1,997.60. Yield is 80% with a purity >95%.

Deacetylation of acetylated galactose [60] and reduction of the t-buthio disulfide

Peptides containing acetylated galactose were dissolved in THF/MeOH/(28%)NH4OH (2/2/1, concentration ∼5 mM). The reaction was followed until its completion by RP-HPLC using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA). RP-HPLC showed two main products corresponding to the deacetylated peptides with different amounts of the tBuS-SCys and the deprotected cysteine. After evaporation of THF and MeOH and lyophilization of the residual aqueous solution, the mixture of peptides (corresponding to the CysS-StBu and the deprotected cysteine) were dissolved in a degassed solution of Tris–HCl 50 mM (∼2 mM). DTT (20 eq.) was added, and the reaction was stirred at RT for 2 h. The final deacetylated free thiol peptides were purified by RP-HPLC on a preparative C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA). Peptide purity was analyzed by analytical RP-HPLC with a C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA) and characterized by MALDI–TOF MS.

(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]-SH, 16 RP-HPLC retention time is 8.2 min (15–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 1,771.93, found 1,771.95. Yield is 70% with a purity >95%.

(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]3-SH, 19 RP-HPLC retention time is 8.0 min (0–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 1,999.98, found 2,000.15. Yield is 38% with a purity >95%.

Biotin(O2)-G4-C(Npys)-KLAKLAKKLAKLAK-NH2, 25

Boc-KLAKLAKKLAKLAK-NH2 was synthesized in a stepwise manner on a 0.5-mmol scale using a (ABI 433-A, Applied Biosystems) synthesizer with standard protocols of Boc chemistry (amino acid activation with DCC/HOBt in NMP). After removal of the Boc group, the resin was neutralized with a solution of DIPEA (10%) in NMP; Boc-(L)-Cys(Npys) (5 eq.) was coupled manually using DCC (5 eq.) activation. After Boc removal, the glycines (10 eq.) and biotin(O2) (10 eq.) were coupled using HBTU activation and in situ neutralization with DIEA (25 eq.). The resin was washed with NMP, CH2Cl2, MeOH, and dried under vacuum. The peptide was cleaved from the resin with anhydrous HF (1 h 15, 0 °C) in the presence of anisole (1.5 ml/g resin) and dimethylsulfide (0.25 ml/g resin). The peptide was purified by RP-HPLC with a C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA). Its purity was analyzed by analytical RP-HPLC with a C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA) and characterized by MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated 2,266.23, found 2,266.71, [M-NpysH]+ calculated 2,112.24, found 2,112.78. Retention time is 18.25 min (15–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). Yield is 15% with a purity >97%.

Biotin(O2)-G4-C(Acm)-KLAKLAKKLAKLAK-NH2, 31

TCEP (2.5 eq.) and iodoacetamide (100 eq.) were added to a solution of peptide 25 (approximately 5 mM) in degassed Tris–HCl (50 mM). Completion of the reaction was determined by HPLC. The peptide was purified by RP-HPLC with a C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA). Its purity was analyzed by analytical RP-HPLC with a C8 column using a linear acetonitrile gradient; retention time is 20.5 min (10–50% acetonitrile over 30 min). The peptide was characterized by MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated 2,169.26, found 2,169.05.

Syntheses of the carrier-cargo conjugates

The thiol peptides were dissolved in a degassed 10% acetic acid and mixed with a slight excess (1.2 eq.) of peptide Biotin(O2)-G4-C(Npys)-[KLAKLAK]2-NH2. The reaction was followed by RP-HPLC, and the conjugates were purified by RP-HPLC on a preparative C8 column using a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA). Peptides were purified by analytical RP-HPLC using a C8 column with a linear acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) gradient in an aqueous solution (0.1% TFA) and characterized by MALDI–TOF MS.

(R6/W3)S-S-KLAK, 26 (Previously described herein for the analog with four deuterated glycines) RP-HPLC retention time is 20.0 min (15–35% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 3,775.18, found 3,775.28. Yield is 46% with purity >95%.

(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]S-S-KLAK, 27 RP-HPLC retention time is 14.0 min (15–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]SHH]+ calculated is 1,771.93, found 1,771.91; [KLAK-SHNa]+ calculated is 2,134.24, found 2,133.85. Yield is 28% with purity >99%.

(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH)]S-S-KLAK, 28 RP-HPLC retention time is 14.0 min (15–55% acetonitrile over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OH)]SHH]+ calculated is 1,829.96, found 1,829.73; [KLAK-SHNa]+ calculated is 2,134.24, found 2,134.03. Yield is 33% with purity >95%.

(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OAc)]S-S-KLAK, 29 RP-HPLC retention time is 3.5 min (20–60% acetonitrile gradient over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 4,107.22, found 4,107.11; [(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(CH2)3(OAc)]SHH]+ calculated is 1,998.00, found 1,997.51; [KLAK-SHH]+ calculated is 2,112.24, found 2,111.71. Yield is 22% with purity >95%.

(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]3 S-S-KLAK, 30 RP-HPLC retention time is 19.5 min (0–55% acetonitrile gradient over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 4,109.20, found 4,109.92; [(R6/W2)-[Pra-Gal(OH)]3SHH]+ calculated is 1,999.98, found 1,999.78; [KLAK-SHH]+ calculated is 2,112.24, found 2,112.05. Yield is 72% with purity >95%.

PenetratinS-S-KLAK, 32 (Previously described herein for the analog with four deuterated glycines) RP-HPLC retention time 19.7 min (15–35% acetonitrile gradient over 30 min). MALDI–TOF MS (m/z) [MH]+ calculated is 4,507.62, found 4,507.48.

Cell viability assays

A cell suspension (100 µL, 5,000 CHO cells per well) were seeded in DMEM plus 10% FCS in 96-well microtiter plates at 37 °C. After 24 h of cell culture, the supernatant was removed, and the peptide in DMEM (100 µL) at concentrations of 1, 10, 20, or 50 µM was added to the cells. After 2 h of incubation at 37 °C, the supernatant was removed, and a solution of CCK8 cell counting kit in DMEM (10%) was used according to the supplier (Dojindo Laboratories). The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (FLUOstar OPTIMA, BMG LABTECH) with a reference wavelength at 620 nm.

Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy was performed on an inverted Nikon Eclipse TE2000-S (objective ×100 PLANFLUO). All experiments were performed with fixed cells. Cells were plated on glass coverslips (7 × 104 cells, 1 cm2) and cultivated for 24 h. The cells were washed once with serum-free medium. Biotin-labeled peptide or conjugates (10 or 20 µM) were incubated with CHO-K1 cells in 300 µL fresh serum-free DMEM/F12 medium for 90 min at 37 °C. After washing, the extracellular peptide was quenched with avidin (10 µM, 10 min at 4 °C). Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and treated with 0.1% Triton ×100. The intracellular peptide was labeled with Alexa-488-streptavidin (1/2,000 of 1 mg/mL solution) for 30 min. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (1.5 µg/mL; Pierce). For the membrane peptide, avidin washings and Triton permeabilization were omitted. Coverslips were mounted in Vectashield (BioValley) for microscopy observation.

Electronic supplementary materials

Acknowledgment

The authors greatly acknowledge Lynda Millstine’s contribution in editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Laurence Dutot and Pascaline Lécorché contributed equally

References

- 1.Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. Molecular biology of the cell. New York: Garland Publishing Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubertalli A, Sitia R. Entry of exogenous polypeptides into the nucleus of living cells: facts and speculations. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:409–412. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(00)89093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dietz GPH, Bähr M. Delivery of bioactive molecules into the cell: the Trojan horse approach. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27:85–131. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langel U (ed) (2007) In: Handbook of Cell-Penetrating Peptides, 2nd edn. Taylor and Francis, Boca Raton

- 5.Morris MC, Deshayes S, Heitz F, Divita G. Cell-penetrating peptides: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutics. Biol Cell. 2008;100:201–217. doi: 10.1042/BC20070116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen M, Kilk K, Langel U. Predicting cell-penetrating peptides. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:572–579. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derossi D, Joliot AH, Chassaing G, Prochiantz A. The third helix of the Antennapedia homeodomain translocates through biological membranes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10444–11045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vivès E, Brodin P, Lebleu B. A truncated HIV-1 Tat protein basic domain rapidly translocates through the plasma membrane and accumulates in the cell nucleus. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16010–16017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.16010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dom G, Shaw-Kackson C, Matis C, Bouffioux O, Picard JJ, Prochiantz A, Mingeot-Leclercq MP, Brasseur R, Rezsohazy R. Cellular uptake of Antennapedia Penetratin peptides is a two-step process in which phase transfer precedes a tryptophan-dependent translocation. Nucleic Acid Res. 2003;31:556–561. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer R, Fotin-Mleczek M, Hufnagel H, Brock R. Break on through to the other side - biophysics and cell biology shed light on cell-penetrating peptides. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:2126–2142. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundin P, Johansson H, Guterstam P, Holm T, Hansen M, Langel U. Distinct uptake routes of cell-penetrating peptide conjugates. El Andaloussi S. Bioconj Chem. 2008;19:2535–2542. doi: 10.1021/bc800212j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duchardt F, Fotin-Mleczek M, Schwarz H, Fischer R, Brock R. A comprehensive model for the cellular uptake of cationic cell-penetrating peptides. Traffic. 2007;8:848–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vives E, Schmidt J, Pelegrin A. Cell-penetrating and cell-targeting peptides in drug delivery. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1786:126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watkins CL, Schmaljohann D, Futaki S, Jones AT (2009) Low concentration thresholds of plasma membranes for rapid energy-independent translocation of a cell-penetrating peptide. Biochem J 420:179–89 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Jiao CY, Delaroche D, Burlina F, Alves ID, Chassaing G, Sagan S (2009) Translocation and endocytosis for cell-penetrating peptides (CPP) internalization. J Biol Chem (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Crombez L, Aldrian-Herrada G, Konate K, Nguyen QN, McMaster GK, Brasseur R, Heitz F, Divita G. A new potent secondary amphipathic cell–penetrating peptide for siRNA delivery into mammalian cells. Molec Ther. 2008;17:95–103. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enback J, Laakkonen P. Tumour-homing peptides: tools for targeting, imaging and destruction. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:780–783. doi: 10.1042/BST0350780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aussedat B, Dupont E, Sagan S, Joliot AH, Lavielle S, Chassaing G, Burlina F (2008) Modifications in the chemical structure of Trojan carriers: impact on cargo delivery. Chem Commun 1398–1400 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Derossi D, Chassaing G, Prochiantz A. Trojan peptides: the penetratin system for intracellular delivery. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:84–87. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delaroche D, Aussedat B, Aubry S, Chassaing G, Burlina F, Clodic G, Bolbach G, Lavielle S, Sagan S. Tracking a new cell-penetrating (W/R) nonapeptide, through an enzyme-stable mass spectrometry reporter tag. Anal Chem. 2007;79:1932–1938. doi: 10.1021/ac061108l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chassaing G, Prochiantz A (1997) Peptides usable as vectors for the intracellular addressing of bioactive molecules. PCT Int Appl WO 9712912 A1 19970410

- 22.Lavielle S, Ling N, Guillemin R. Solid-phase synthesis of two glycopeptides containing the amino acid sequence 5 to 9 of somatostatin. Carbohydrate Res. 1981;89:221–228. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)85247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polt R, Porreca F, Szabo LZ, Bilsky EJ, Davis P, Abbruscato TJ, Davis TP, Horvath R, Yamamura HI, Hruby VJ. Glycopeptide enkephalin analogues produce analgesia in mice: evidence for penetration of the blood-brain barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7114–7118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michael K, Wittmann V, König W, Sandow J, Kessler HS. S- and C-glycopeptide derivatives of an LH-RH antagonist. Int J Peptide Protein Res. 1996;48:59–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1996.tb01107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egleton RD, Mitchell SA, Huber JD, Janders J, Stropova D, Polt R, Yamamura HI, Hruby VJ, Davis TP. Biousian glycopeptides penetrate the blood–brain barrier. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2005;16:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foerg C, Ziegler U, Fernandez-Carneado J, Giralt E, Rennert R, Beck-Sickinger AG, Merkle HP. Decoding the entry of two novel cell-penetrating peptides in HeLa cells: lipid raft-mediated endocytosis and endosomal escape. Biochemistry. 2005;44:72–81. doi: 10.1021/bi048330+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magzoub M, Pramanik A, Graslund A. Modeling the endosomal escape of cell-penetrating peptides: transmembrane pH gradient driven translocation across phospholipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14890–14897. doi: 10.1021/bi051356w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiraishi T, Nielsen PE. Enhanced delivery of cell-penetrating peptide–peptide nucleic acid conjugates by endosomal disruption. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:633–636. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundberg P, El-Andaloussi S, Sutlu T, Johansson H, Langel U. Delivery of short interfering RNA using endosomolytic cell-penetrating peptides. FASEB J. 2007;21:2664–2671. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6502com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo SL, Wang S. An endosomolytic Tat peptide produced by incorporation of histidine and cysteine residues as a nonviral vector for DNA transfection. Wang S Biomaterials. 2008;29:2408–2414. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Law B, Quinti L, Choi Y, Weissleder R, Tung CH. A mitochodrial targeted fusion peptide exhibits remarkable cytotoxicity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1944–1949. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foillard S, Jin ZH, Garanger E, Boturyn D, Favrot MC, Coll JL, Dumy P. Synthesis and biological characterisation of targeted pro-apoptotic peptide. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:2326–2332. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marks AJ, Cooper MS, Anderson RJ, Orchard KH, Hale G, North JM, Ganeshaguru K, Steele AJ, Mehta AB, Lowdell MW, Wickremasinghe RG. Selective apoptotic killing of malignant hemopoietic cells by antibody-targeted delivery of an amphipathic peptide. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2373–2377. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collot M, Savreux J, Mallet JM. New thioglycoside derivatives for use in odorless synthesis of MUXF3 N-glycan fragments related to food allergens. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:1523–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joosten JAF, Loimaranta V, Appeldoorn CCM, Haataja S, El Maate FA, Liskamp RMJ, Finne J, Pieters RJ. Inhibition of streptococcus suis adhesion by dendritic galabiose compounds at low nanomolar concentration. J Med Chem. 2004;47:6499–6508. doi: 10.1021/jm049476+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu X, Kawatkar S, Rao Y, Boons GJ. Practical approach for the stereoselective introductionof b-arabinofuranosides. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;129:11948–11957. doi: 10.1021/ja0629817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Click chemistry: diverse chemical function from a few good reactions. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:2004–2021. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tornoe CW, Christensen C, Meldal M. Peptidotriazoles on solid phase: [1,2,3]-triazoles by regiospecific copper(I)-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions of terminal alkynes to azides. J Org Chem. 2002;67:3057–3064. doi: 10.1021/jo011148j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Z, Fan E. Solid phase synthesis of peptidotriazoles with multiple cycles of triazole formation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.11.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jang H, Fafarman A, Holub JM, Kirshenbaum K. Click to fit: versatile polyvalent display on a peptidomimetic scaffold. Org Lett. 2005;7:1951–1954. doi: 10.1021/ol050371q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coats SJ, Link JS, Gauthier D, Hlasta DJ. Trimethylsilyl-directed 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions in the solid-phase synthesis of 1,2,3-triazoles. Org Lett. 2005;7:1469–1472. doi: 10.1021/ol047637y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harju K, Vahermo M, Mutikainen I, Yli-Kauhaluoma J. Solid-phase synthesis of 1,2,3-triazoles via 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition. J Comb Chem. 2003;5:826–833. doi: 10.1021/cc030110c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parikh PB, Kim YS, Chang YT. Single resin bead kinetics using real time fluorescence measurements. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2002;23:1509–1510. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ploux O, Chassaing G, Marquet A. Cyclization of peptides on a solid support - Application to cyclic analogs of substance-P. Int J of Peptide and Protein Res. 1987;29:162–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1987.tb02242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aubry S, Burlina F, Dupont E, Delaroche D, Joliot A, Lavielle S, Chassaing G, Sagan S (2009) Cell-surface thiols affect cell entry of disulfide-conjugated peptides. FASEB J (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Burlina F, Sagan S, Bolbach G, Chassaing G. Quantification of the cellular uptake of cell-penetrating peptides by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:4244–4247. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richard JP, Melikov K, Vives E, Ramos C, Verbeure B, Gait MJ, Chernomordik LV, Lebleu B. Cell-penetrating peptides - A reevaluation of the mechanism of cellular uptake. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:585–590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Puckett CA, Barton JK. Fluorescein redirects a ruthenium-octaarginine conjugate to the nucleus. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8738–8739. doi: 10.1021/ja9025165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dupont E, Prochiantz A, Joliot A. Identification of a signal peptide for unconventional secretion. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8994–9000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609246200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wender PA, Mitchell DJ, Pattabiraman K, Pelkey ET, Steinman L, Rothbard JB. The design, synthesis, and evaluation of molecules that enable or enhance cellular uptake: peptoid molecular transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13003–13008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mitchell DJ, Kim DT, Steinman L, Fathman CG, Rothbard JB. Polyarginine enters cells more efficiently than other polycationic homopolymers. J Pept Res. 2000;56:318–325. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2000.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rothbard B, Kreider E, VanDeusen CL, Wright L, Wylie BL, Wender PA. Arginine-rich molecular transporters for drug delivery: role of backbone spacing in cellular uptake. J Med Chem. 2002;45:3612–3618. doi: 10.1021/jm0105676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bilsky EJ, Egleton RD, Mitchell SA, Palian MM, Davis P, Huber JD, Jones H, Yamamura HI, Janders J, Davis TP, Porreca F, Hruby VJ, Polt R. Enkephalin glycopeptide analogues produce analgesia with reduced dependence liability. J Med Chem. 2000;43:2586–2590. doi: 10.1021/jm000077y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buskas T, Ingale S, Boons GJ. Glycopeptides as versatile tools for glycobiology. Glycobiology. 2006;16:113R–136R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maiti KK, Lee WS, Takeuchi T, Watkins C, Fretz M, Kim DC, Futaki S, Jones A, Kim KT, Chung SK. Guanidine-containing molecular transporters: sorbitol-based transporters show high intracellular selectivity toward mitochondria. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:5880–5884. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maiti KK, Jeon OY, Lee WS, Chung SK. Design, synthesis, and delivery properties of novel guanidine-containing molecular transporters built on dimeric inositol scaffolds. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:762–775. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu H, Chokhawala H, Karpel R, Yu H, Wu B, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Jia Q, Chen X. A multifunctional Pasteurella multocida sialyltransferase: a powerful tool for the synthesis of sialoside libraries. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17618–17619. doi: 10.1021/ja0561690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu XM, Thakur A, Wang D. Efficient synthesis of linear multifunctional poly(ethylene glycol) by copper(I)-catalyzed huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition. Biomacromol. 2007;8:2653–2658. doi: 10.1021/bm070430i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sachon E, Tasseau O, Lavielle S, Sagan S, Bolbach G. Isotope and affinity tags in photoreactive substance P analogues to identify the covalent linkage within the NK-1 receptor by MALDI-TOF analysis. Anal Chem. 2003;75:6536–6543. doi: 10.1021/ac034512i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hasegawa T, Numata M, Okumura S, Kimura T, Sakurai K, Shinkai S. Carbohydrateappended curdlans as a new family of glycoclusters with binding properties both for a polynucleotide and lectins. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:2404–2412. doi: 10.1039/b703720a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.