Abstract

Background

Prior studies suggest that the causes of calcific aortic valve (AV) disease involve chronic inflammation, lipoprotein levels, and calcium metabolism, all of which may differ among race-ethnic groups. We sought to determine whether AV thickness differs by race-ethnicity in a large multi-ethnic population-based cohort.

Methods

The Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS) includes stroke-free community-based Hispanic (57%), non-Hispanic black (22%), and non-Hispanic white (21%) participants. The relation between AV thickness on transthoracic echocardiography and clinical risk factors for atherosclerosis was evaluated among 2085 participants using polytomous logistic regression models. AV thickness was graded in three categories (normal, mild, and moderate/severe) based on leaflet thickening and calcification.

Results

Mild AV thickness was present in 44.4% and moderate/severe thickness in 5.7% of the cohort, with the lowest frequency of moderate/severe thickness seen particularly among Hispanic females. In multivariate models adjusting for age, sex, race-ethnicity, body mass index, hypertension, coronary artery disease, blood glucose, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Hispanics had significantly less moderate/severe AV thickness (odds ratio (OR) 0.43, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 0.25 to 0.73) than non-Hispanic whites. Men were almost 2-fold as likely to have moderate/severe AV thickness compared to women (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.24 to 3.10).

Conclusions

In this large multi-ethnic population-based cohort, there were ethnic differences in the degree of AV thickness. Hispanic ethnicity was strongly protective against AV thickness. This effect was not related to traditional risk factors, suggesting that unmeasured factors related to Hispanic ethnicity and AV thickness may be responsible.

Introduction

With the current shift toward an elderly population, calcific aortic valve (AV) disease is an important and growing public health problem. The prevalence of AV calcification in the general population is estimated at 25% in patients 65 years and older, increasing to 48% in those above 84 years of age 1-3. Calcific AV disease is identified by thickening and calcification of the AV leaflets in the absence of rheumatic heart disease. For many years, calcific AV disease was regarded as a degenerative and therefore unmodifiable process. However, more recent studies have demonstrated that calcific lesions have many features characteristic of an active pathobiological process, including chronic inflammation, lipoprotein deposition, and active leaflet calcification, as well as a manifestation of the atherosclerotic process 4-6, all of which may differ among race-ethnic groups. Some studies showed disparities among race-ethnic groups in prevalence of atherosclerotic risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and inflammatory status 7-9. In particular, Hispanics have been shown to have less mitral annular calcification and coronary artery calcification than non-Hispanic whites 10-12. Thus, we sought to determine whether AV thickness based on leaflet thickening and calcification differs by race-ethnicity in a large multi-ethnic population-based cohort.

Methods

Study population

The Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS) is a population-based prospective cohort study of stroke-free individuals that was designed to investigate cardiovascular and stroke incidences, risk factors, and prognosis in a multi-ethnic urban population of the northern Manhattan (New York) area. The methods of subject recruitment and enrollment into NOMAS have been described previously 13. Briefly, community participants from northern Manhattan were eligible if they (1) had never been diagnosed with a stroke, (2) were ≥ 40 years of age, and (3) resided in northern Manhattan for at least 3 months in a household with a telephone. Stroke-free participants were identified by random digit dialing. Ninety percent of those called participated in a telephone interview, and 75% of those who were eligible and invited to participate came to Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) for an in-person evaluation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at CUMC, and all participants gave written informed consent. A total of 3298 subjects underwent in-person evaluation between 1993 and 2001, including transthoracic echocardiograms in a majority of participants. Echocardiograms were technically adequate for analysis in 2085 subjects and these form the basis for this analysis.

Clinical and biochemical data

The variables chosen for this analysis were based on previous studies that showed risk factors associated with AV sclerosis and stenosis are similar to those of atherosclerosis 2, 14, 15. Continuous variables included age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, average of systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP), blood sugar, total cholesterol, high- and low-density lipoprotein (HDL, LDL) cholesterol, total homocysteine, white blood count (WBC), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP). Categorical variables included sex, race-ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, and non-Hispanic black), smoking (history and current), hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease (CAD), socio-economic status (SES), depression, and physical activity. Information about risk factors was collected through interviews by trained research assistants, and physical examinations were performed by study physicians. BP was measured with mercury sphygmomanometers and cuffs of appropriate size. Hypertension was defined as a BP recording ≥140/90 mmHg (based on an average of 2 BP measurements during 1 sitting by a trained research assistant), the patient’s self-report of a history of hypertension, or antihypertensive medication use. Diabetes mellitus was defined by the patient’s self-report of such a history, use of insulin or hypoglycemic agent, or fasting glucose ≥ 126mg/dL. CAD was defined as having a history of bypass surgery, angioplasty, or myocardial infarction. Education level was used as the indicator of SES and classified in four categories; less than high school, completed high school, some collage, and college graduate or more. Assessments were conducted in English or Spanish, depending on the primary language of the participant. Race-ethnicity was based on self-identification through a series of interview questions modeled after the 2000 US census, and they conformed to the standard definitions outlined by Directive 15. Current smoking was defined by smoking within the past year.

Echocardiographic evaluation of aortic valve thickness

Transthoracic 2-dimensional echocardiography (TTE) was performed in all study subjects according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography 16. Interpretation of echocardiographic studies was performed blinded to clinical and demographic characteristics. Interobserver reliability was periodically assessed by use of intraclass correlation coefficients for the variables measured, which ranged between 0.59 and 0.74. Intraobserver reliability was measured by the Kappa statistic based on two repeated reading of AV thickness for 23 subjects. The Kappa statistic was 0.94 with 95% confidence interval 0.82-1.00. Assessment of the AV was performed on the basis of the parasternal long-axis, apical 5- or 3-chamber, or parasternal short-axis views. AV thickness was defined as focal areas of increased echogenicity and thickening of the AV leaflets without restriction of leaflet motion. AV thickness was qualitatively classified into four categories, accounting for thickening and calcification of each valve leaflet, by a single reader: normal, mild, moderate, and severe. Due to there being only few participants with severe AV thickness, moderate and severe categories were combined for the purposes of this analysis.

For validation of the three categories of AV thickness, a separate blinded reader measured the maximum dimension of the AV leaflet in sample images in 20 subjects for each category on the basis of the parasternal short-axis view. There were clear differences in measurement of valve thickness among the three categories using ANOVA (F=83.7, p<0.0001). In Wilcoxon’s rank sum test for pairwise comparison, p-values were all <0.0001 among the three categories.

Statistical analyses

The distribution of demographics and vascular risk factors was evaluated in the total cohort and among the three categories of AV thickness. Means were calculated for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. Comparisons were made using t tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Univariate and multivariate polytomous logistic regression models were used to analyze the association between clinical risk factors for atherosclerosis and AV thickness. The reference group for the presented analyses is normal valves, and odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (OR, 95% CI) are presented for mild and moderate/severe categories. Significant univariate predictors (p <0.05) were selected as covariates for multivariate analyses. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The cohort was predominantly elderly (mean age 68.2 ± 9.7 years), female (60%), and hypertensive (68%). The majority of the subjects were Hispanic (57%), followed by non-Hispanic blacks (22%) and non-Hispanic whites (21%). Other characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table 1. Of 2085 subjects, 1047(50.1%) had any grade of AV thickness. Mild AV thickness was present in 44.4% and moderate/severe thickness in only 5.7% of the cohort. Subjects with any AV thickness were significantly older than subjects with normal aortic valves (p<0.0001), and there was a higher prevalence of hypertension and CAD with increasing AV thickness (p<0.0001). Demographic characteristics were compared between those present our study population to those excluded from our study. Smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and CAD which were important risk factors of atherosclerosis did not differ between present population and excluded population (all p>0.07). Levels of HDL were of borderline statistical significance lower in our study population compared to those excluded (p=0.05).

Table 1.

Demographics and risk factors by AV thickness

| All (n=2085) |

Normal (n=1038) |

Mild (n=927) |

Moderate/Severe (n=120) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 68.2 ± 9.7 | 66.0 ± 9.1 | 69.5 ± 9.4 | 76.9 ± 8.9 | <0.0001 |

| Male sex | 824 (40) | 389 (37) | 378 (40) | 57 (47) | 0.06 |

| Race ethnicity | <0.0001 | ||||

| White* | 441 | 182 | 210 | 49 | |

| Hispanic | 1179 | 621 | 522 | 36 | |

| Black* | 465 | 235 | 195 | 35 | |

| Current smoke | 346 (17) | 165 (16) | 167 (18) | 14 (12) | 0.14 |

| Hypertension | 1425 (68) | 661 (64) | 668 (72) | 96 (80) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 461 (22) | 222 (21) | 205 (22) | 34 (28) | 0.22 |

| Coronary artery disease | 174 (8) | 59 (6) | 96 (10) | 19 (16) | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 203.7 ± 40.5 | 201.7 ± 39.3 | 205.1 ± 41.7 | 209.3 ± 40.8 | 0.06 |

| LDL, mg/dL | 130.7 ± 35.9 | 128.7 ± 35.6 | 132.6 ± 36.6 | 133.9 ± 32.0 | 0.04 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 46.3 ± 14.6 | 47.0 ± 14.6 | 45.4 ± 14.3 | 47.0 ± 15.7 | 0.04 |

| Homocysteine, μmol/L | 9.8 ± 4.2 | 9.6 ± 4.2 | 9.8 ± 4.3 | 11.0 ± 4.6 | 0.02 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.96±0.47 | 0.94 ± 0.35 | 0.97 ± 0.59 | 1.05 ± 0.32 | 0.03 |

| Calcium, mg/dL | 9.1±0.49 | 9.1 ± 0.46 | 9.1 ± 0.53 | 9.1 ± 0.46 | 0.40 |

| Blood glucose, mg/dL | 107.0 ± 50.0 | 105.5 ± 49.4 | 107.6 ± 49.6 | 115.6 ± 57.7 | 0.11 |

| WBC | 6.2 ± 1.9 | 6.1 ± 2.0 | 6.2 ± 1.8 | 6.0 ± 1.6 | 0.44 |

| hsCRP, mg/L | 5.0 ± 7.6 | 4.7 ± 6.3 | 5.1 ± 8.6 | 5.6 ± 8.3 | 0.48 |

| SBP, mmHg | 144.2 ± 21.0 | 142.0 ± 20.7 | 146.6 ± 20.9 | 145.6 ± 21.6 | <0.0001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 83.4 ± 11.3 | 83.3 ± 11.1 | 83.7 ± 11.4 | 81.9 ± 11.5 | 0.24 |

Data are expressed as mean + SD or n (%) of subjects.

White=Non-Hispanic white, Black=Non-Hispanic black

LDL= low-density lipoprotein; HDL= high-density lipoprotein; WBC=white blood count; hsCRP= high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; SBP= systolic blood pressure; DBP= diastolic blood pressure.

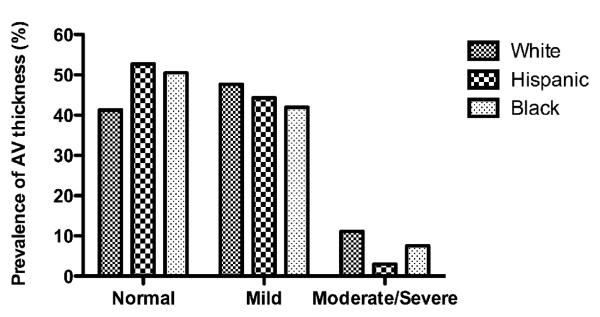

There were significant race-ethnic differences in the degree of AV thickness (p<0.0001). Non-Hispanic whites had the highest prevalence of any AV thickness (58.7%), followed by non-Hispanic blacks (49.5%) and Hispanics (47.3%). Figure 1 shows prevalence of grade of AV thickness among race-ethnic groups. Non-Hispanic whites had the highest prevalence of moderate/severe AV thickness (11.1%), and Hispanics had the lowest (3.1%). Hispanics were younger (p<0.0001) and had lower levels of HDL (p<0.0001) and CAD prevalence but higher prevalences of hypertension and diabetes than non-Hispanic whites. LDL, total cholesterol, hsCRP, homocysteine, and baseline creatinine did not differ between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of grade of AV thickness among race-ethnic groups.

There were significant race-ethnic differences in the degree of AV thickness among three ethnic groups (p<0.0001).

Table 2.

Characteristics according to race-ethnicity

| All (n=2085) |

White (n=441) |

Hispanic (n=1179) |

Black (n=465) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 68.2±9.7 | 72.9±9.8 | 65.6±8.5 | 70.3±10.0 | <0.0001 |

| Male sex | 824 (39.5) | 191 (43.3) | 475 (40.3) | 158 (34.0) | 0.01 |

| Height, cm | 162.5±10.1 | 164.6±10.9 | 160.7±9.3 | 164.8±10.2 | <0.0001 |

| Weight, kg | 73.2±15.6 | 70.6±16.9 | 73.0±13.8 | 76.2±17.9 | <0.0001 |

| BMI | 27.7±5.4 | 25.9±5.2 | 28.2±4.8 | 28.1±6.3 | <0.0001 |

| Ever smoke | 1121 (54) | 261 (59) | 590 (50) | 270 (58) | 0.0004 |

| Current smoke | 346 (17) | 61 (14) | 182 (16) | 103 (22) | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1425 (68) | 257 (58) | 816 (69) | 352 (76) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 461 (22) | 62 (14) | 282 (24) | 117 (25) | <0.0001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 174 (8.4) | 55 (12.5) | 87 (7.4) | 32 (6.9) | 0.002 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 203.7±40.5 | 207.4±38.8 | 202.3±41.2 | 203.6±40.4 | 0.08 |

| LDL, mg/dL | 130.7±35.9 | 132.9±35.2 | 130.5±35.9 | 129.2±36.7 | 0.3 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 46.3±14.6 | 48.3±14.9 | 43.3±12.8 | 52.1±16.3 | <0.0001 |

| Homocysteine, μmol/L | 9.8±4.2 | 9.5±2.8 | 9.5±4.3 | 10.7±5.1 | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.96±0.47 | 0.96±0.26 | 0.93±0.53 | 1.06±0.43 | <0.0001 |

| Calcium, mg/dL | 9.1±0.49 | 9.0±0.4 | 9.0±0.5 | 9.1±0.5 | 0.4 |

| Blood glucose, mg/dL | 107.0±50.0 | 100.4±39.3 | 109.9±54.5 | 105.9±46.6 | 0.003 |

| WBC | 6.2±1.9 | 6.3±1.9 | 6.3±1.8 | 5.7±2.0 | <0.0001 |

| hsCRP, mg/L | 5.0±7.6 | 4.6±9.7 | 4.8±6.5 | 5.7±8.1 | 0.15 |

| SBP, mmHg | 144.2±21.0 | 140.9±20.7 | 144.1±20.9 | 147.5±21.1 | <0.0001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 83.4±11.3 | 79.3±10.9 | 84.7±10.8 | 84.0±11.9 | <0.0001 |

Data are expressed as mean + SD or n (%) of subjects.

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

The results of univariate and multivariate polytomous logistic regression models are shown Table 3. In our univariate logistic analysis, age, hypertension, and CAD were positively associated with both mild and moderate/severe AV thickness, whereas Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks had significantly less mild and moderate/severe AV thickness than non-Hispanic whites. HDL was related to mild thickness but not moderate/severe AV thickness. In contrast, blood glucose was not related to mild thickness but was significantly associated with moderate/severe AV thickness.

Table 3.

Predictors of AV thickness in polytomous model

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age (mild)† | 1.04 | 1.03-1.05 | <0.0001 | 1.04 | 1.03-1.06 | <0.0001 |

| (moderate/severe)† | 1.13 | 1.10-1.15 | <0.0001 | 1.13 | 1.10-1.16 | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| Male | 0.87 | 0.72-1.04 | 0.13 | 1.17 | 0.95-1.44 | 0.13 |

| 0.66 | 0.45-0.96 | 0.03 | 1.96 | 1.24-3.10 | 0.003 | |

|

| ||||||

| Hispanic‡ | 0.73 | 0.58-0.92 | 0.007 | 0.90 | 0.70-1.16 | 0.41 |

| 0.22 | 0.14-0.34 | <0.0001 | 0.43 | 0.25-0.72 | 0.001 | |

|

| ||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black‡ | 0.72 | 0.55-0.95 | 0.01 | 0.79 | 0.59-1.07 | 0.12 |

| 0.55 | 0.34-0.89 | 0.01 | 0.75 | 0.44-1.28 | 0.28 | |

|

| ||||||

| BMI | 0.99 | 0.97-1.00 | 0.15 | 0.99 | 0.97-1.01 | 0.39 |

| 0.95 | 0.91-0.98 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.96-1.04 | 0.93 | |

|

| ||||||

| Waist | 0.99 | 0.97-1.00 | 0.34 | |||

| 0.96 | 0.93-1.00 | 0.07 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Current smoke | 1.17 | 0.93-1.49 | 0.18 | |||

| 0.71 | 0.40-1.27 | 0.24 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Hypertension | 1.47 | 1.21-1.78 | <0.0001 | 1.37 | 1.12-1.69 | 0.002 |

| 2.28 | 1.43-3.63 | 0.0005 | 2.14 | 1.28-3.61 | 0.004 | |

|

| ||||||

| Diabetes | 1.04 | 0.84-1.29 | 0.69 | |||

| 1.45 | 0.95-2.22 | 0.08 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 1.92 | 1.37-2.69 | 0.0002 | 1.50 | 1.05-2.16 | 0.02 |

| 3.12 | 1.79-5.44 | <0.0001 | 1.77 | 0.95-3.33 | 0.07 | |

|

| ||||||

| SBP | 1.01 | 1.00-1.01 | <0.0001 | |||

| 1.01 | 0.99-1.01 | 0.06 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| DBP | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | 0.42 | |||

| 0.99 | 0.97-1.00 | 0.20 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Blood glucose | 1.00 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.34 | 1.001 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.42 |

| 1.00 | 1.00-1.01 | 0.03 | 1.005 | 1.00-1.01 | 0.006 | |

|

| ||||||

| Total cholesterol | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 0.06 | |||

| 1.00 | 1.00-1.01 | 0.05 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| LDL | 1.00 | 1.00-1.01 | 0.01 | |||

| 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | 0.13 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| HDL | 0.99 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.98-0.99 | 0.007 |

| 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98-1.01 | 0.34 | |

|

| ||||||

| Homocysteine | 1.01 | 0.99-1.04 | 0.30 | |||

| 1.05 | 1.02-1.09 | 0.004 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| WBC | 1.02 | 0.97-1.07 | 0.46 | |||

| 0.95 | 0.86-1.06 | 0.38 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| hsCRP | 1.01 | 0.99-1.02 | 0.29 | |||

| 1.01 | 0.99-1.04 | 0.36 | ||||

The first row of each set is mild compared normal, and the second is moderate/severe compared normal.

In the sets of race-ethnicity, reference group is non-Hispanic whites.

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

In multivariable logistic regression models adjusting for age, sex, race-ethnicity, BMI, hypertension, CAD, blood glucose, and HDL, only age, Hispanic race-ethnicity, sex, and hypertension status remained independently associated with severity of AV thickness. Compared with non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics were 57% less likely to have moderate/severe AV thickness; non-Hispanic blacks showed no significant association with AV thickness. Men, meanwhile, tended to have almost 2-fold greater odds of moderate/severe AV thickness than women. In separate models including adjustments for SES, depression and physical activity, Hispanic still had less moderate/severe AV thickness (Table 4).

Table 4.

multivariate polytomous models including SES, depression and physical activity

| model 1 | model 2 | model 3 | model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age vs. mild§ | 1.04 | 1.03-1.05 | <0.0001 | 1.04 | 1.03-1.05 | <0.0001 | 1.04 | 1.03-1.06 | <0.0001 | 1.04 | 1.03-1.06 | <0.0001 |

| vs. moderate/severe§ | 1.13 | 1.10-1.16 | <0.0001 | 1.13 | 1.10-1.16 | <0.0001 | 1.13 | 1.10-1.16 | <0.0001 | 1.13 | 1.10-1.16 | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Male | 1.15 | 0.93-1.42 | 0.19 | 1.19 | 0.96-1.46 | 0.11 | 1.13 | 0.92-1.39 | 0.25 | 1.18 | 0.96-1.45 | 0.12 |

| 1.90 | 1.20-3.03 | 0.007 | 1.96 | 1.24-3.11 | 0.004 | 1.93 | 1.22-3.06 | 0.005 | 1.94 | 1.22-3.07 | 0.005 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Hispanic Π | 0.85 | 0.63-1.16 | 0.31 | 0.83 | 0.61-1.12 | 0.21 | 0.92 | 0.72-1.19 | 0.54 | 0.90 | 0.69-1.16 | 0.41 |

| 0.45 | 0.24-0.85 | 0.01 | 0.42 | 0.23-0.78 | 0.006 | 0.44 | 0.26-0.75 | 0.002 | 0.45 | 0.27-0.77 | 0.004 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Black Π | 0.75 | 0.55-1.02 | 0.06 | 0.75 | 0.55-1.02 | 0.06 | 0.79 | 0.59-1.06 | 0.11 | 0.80 | 0.60-1.08 | 0.14 |

| 0.75 | 0.43-1.29 | 0.30 | 0.73 | 0.42-1.26 | 0.26 | 0.76 | 0.45-1.30 | 0.31 | 0.76 | 0.44-1.29 | 0.30 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| BMI | 0.99 | 0.97-1.01 | 0.47 | 0.99 | 0.97-1.01 | 0.40 | 0.99 | 0.97-1.01 | 0.44 | 0.99 | 0.97-1.01 | 0.40 |

| 1.00 | 0.96-1.05 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.96-1.04 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.95-1.04 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.96-1.05 | 0.99 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Hypertension | 1.36 | 1.11-1.68 | 0.004 | 1.37 | 1.11-1.68 | 0.003 | 1.38 | 1.12-1.70 | 0.003 | 1.37 | 1.11-1.69 | 0.003 |

| 2.22 | 1.31-3.77 | 0.003 | 2.13 | 1.27-3.59 | 0.004 | 2.23 | 1.32-3.79 | 0.003 | 2.15 | 1.28-3.62 | 0.004 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 1.50 | 1.05-2.15 | 0.03 | 1.51 | 1.06-2.16 | 0.02 | 1.51 | 1.06-2.17 | 0.02 | 1.49 | 1.04-2.14 | 0.03 |

| 1.79 | 0.95-3.38 | 0.07 | 1.77 | 0.94-3.32 | 0.08 | 1.78 | 0.95-3.33 | 0.07 | 1.80 | 0.96-3.39 | 0.07 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Blood sugar | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 0.51 | 1.00 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.45 | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | 0.46 | 1.00 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.46 |

| 1.01 | 1.00-1.01 | 0.007 | 1.01 | 1.00-1.01 | 0.006 | 1.01 | 1.00-1.01 | 0.007 | 1.01 | 1.00-1.01 | 0.007 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| HDL | 0.99 | 0.98-1.00 | 0.009 | 0.99 | 0.98-0.99 | 0.008 | 0.99 | 0.98-1.00 | 0.007 | 0.99 | 0.98-1.00 | 0.008 |

| 0.99 | 0.98-1.01 | 0.30 | 0.99 | 0.98-1.00 | 0.35 | 0.99 | 0.98-1.01 | 0.31 | 0.99 | 0.98-1.01 | 0.33 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| socio-economic status¶ | ||||||||||||

| completed high school | 1.07 | 0.81-1.40 | 0.65 | 1.06 | 0.81-1.39 | 0.69 | ||||||

| 1.00 | 0.55-1.80 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.57-1.83 | 0.95 | |||||||

| some college | 0.97 | 0.70-1.34 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.68-1.31 | 0.73 | ||||||

| 1.14 | 0.59-2.20 | 0.69 | 1.13 | 0.59-2.17 | 0.71 | |||||||

| ≥college graduate | 0.81 | 0.59-1.11 | 0.19 | 0.81 | 0.59-1.10 | 0.18 | ||||||

| 0.90 | 0.47-1.73 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.46-1.72 | 0.73 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| depression | 0.79 | 0.65-0.97 | 0.02 | 0.80 | 0.66-0.98 | 0.03 | ||||||

| 0.89 | 0.57-1.42 | 0.64 | 0.90 | 0.57-1.43 | 0.66 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| physical activity | 0.95 | 0.78-1.16 | 0.62 | 0.94 | 0.78-1.14 | 0.55 | ||||||

| 1.30 | 0.83-2.05 | 0.25 | 1.31 | 0.84-2.06 | 0.24 | |||||||

The first row of each set is mild compared normal, and the second is moderate/severe compared normal.

In the sets of race-ethnicity, reference group is non-Hispanic whites.

In the sets of SES, reference group is less than high school.

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Discussion

In this elderly multi-ethnic population-based cohort, we found that the prevalence of AV thickness differed among race-ethnic groups. In particular, Hispanics had less moderate/severe AV thickness after adjustment for atherosclerotic risk factors. The present study is the first to demonstrate race-ethnic differences in the prevalence and grade of AV thickness in a multi-ethnic cohort inclusive of Hispanics. The influence of ethnicity has not been adequately examined in patients with calcific AV disease. While previous studies have identified clinical factors associated with aortic sclerosis and stenosis, few studies have explored ethnic differences 14. The Cardiovascular Health Study, a biracial cohort (n=5621) not inclusive of Hispanics, examined risk factors for incident calcific AV disease and progression from AV sclerosis to stenosis and found non-Hispanic blacks had a lower risk of AV disease progression compared with non-Hispanic whites.

Some studies have shown that Hispanics have less mitral annular calcification (MAC) and coronary artery calcification (CAC) than non-Hispanic whites even though Hispanics had a worse atherosclerotic profile 10-12, 17, 18. The finding that Hispanics generally have a worse cardiovascular profile but less cardiovascular risk is called the ‘Hispanic paradox’ 19, 20. The Hispanic paradox remains controversial 21, 22 but seems to be supported by our results. Analogous to our results with AV thickness, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis recently found Hispanics had lower prevalence of CAC than non-Hispanic whites, and the relative risk for having CAC was the lowest in Hispanics after adjustment for clinical factors 10. Another study showed significantly lower percentage of severe CAC scores among Hispanics than non-Hispanic white men although Hispanic subjects had worse cardiovascular risk factor profile than white men17. Although these studies seem consistent with the Hispanic paradox, it is important to note that cardiovascular events were not assessed in any of these analyses, including ours, so it is unknown if the described lower risk of MAC, CAC, and AV calcification/thickness among Hispanics actually translates to less cardiovascular events and less cardiovascular risk. The clinical relevance of these findings remains unknown and needs to be further studied. Ethnic differences have also been found in carotid artery wall thickness, another subclinical cardiovascular disease marker. In one study, Hispanic participants had less common carotid artery intima-media thickness, which together with our data, suggests a common mechanism of less systemic atherosclerosis among Hispanics 23.

We found that although traditional atherosclerotic risk factors were associated with AV thickness, these variables did not explain the ethnic variability in the presence or degree of AV thickness. This suggests that differences in AV thickness based on leaflet thickening and calcification do not purely reflect differences in atherosclerosis. First, calcified plaque represents only a small proportion of total plaque burden 24. Second, it has been suggested that vitamin D metabolism explains some but not all of the difference in coronary artery calcification between non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks 25. Many factors have been proposed to explain calcific AV disease, and there is accumulating evidence that other aspects of calcium metabolism or bone regulatory factors, inflammatory markers, endothelial function, or genetic factors are related to calcific AV disease. Some genes have been reported to be associated with calcific AV disease, and gene-environment interaction may play a role 26. Metabolic and signaling pathways in the endothelium and the subendothelial space, such as nitric oxide and the renin-angiotensin system, and cellular processes like calcification, inflammation, remodeling, lipid deposition, and osteoblast differentiation, lead to the final manifestations of atherosclerotic disease 4, 26, 27. Lastly, non-traditional factors important in ethnic populations may influence calcific AV disease, as a recent study showed an independent association between acculturation and socioeconomic factors with CAC 28.

Unexpectedly hsCRP, a sensitive marker of systemic inflammation, was not associated with AV thickness in our study. A recent large cohort study also showed hsCRP was not associated with either the presence or progression of calcific AV disease 14 although hsCRP levels are elevated in aortic stenosis patients with severe disease awaiting surgery 29. Thus, hsCRP may not be strongly predictor of subclinical calcific AV disease.

Tissue calcification and differences in bone mineral density may play a role in race-ethnic differences of calcific AV disease. Bone density tends to be greater and osteoporosis less common in non-Hispanic blacks than in non-Hispanic whites 30, and bone density is inversely related to vascular calcification 31. Further study will serve as a basis for exploration of other factors, including environmental, behavioral, and genetic factors, to determine causes of calcific AV disease and to explain the observed group difference in calcific AV disease.

Important strengths of this study are its large sample size, population-based design, systemic review of echocardiographic studies and the presence of a tri-ethnic sample. Several limitations also exist. First, Hispanics in NOMAS are mostly Caribbean-Hispanics and represent one sub-fraction of all Hispanics. Even though all Hispanics have a common language, they have different ancestral origins, cultures, diets, and SES all of which may contribute to differences in cardiovascular risk. Second, AV thickness defined by TTE may be overestimated. The prevalence of AV thickness in our study is higher (50%) than previously reported for AV sclerosis and stenosis (31% to 36%) 2, 14, 15. We graded AV thickness in three categories accounting for thickening and calcification, and we did not require the presence of aortic sclerosis; AV thickness in our study may thus include earlier stages of aortic sclerosis which in other studies would be categorized into normal. However, this potential for measurement bias would be non-differential misclassification among all race-ethnic groups and would result in underestimation of the race-ethnic differences described. Third, we did not collect continuous wave Doppler velocity data. Peak and mean AV velocity is necessary to determine aortic stenosis severity so we are unable to provide this assessment. We did not collect data documenting valve morphology (tricuspid versus bicuspid). While we realize that bicuspid AV is a genetic condition and could potentially vary in different race-ethnic groups, our cohort was predominantly elderly and it may be particularly difficult to distinguish the presence or absence of bicuspid aortic valve in cases of advanced AV calcific disease. Lastly, this is a cross-sectional study; therefore, the causal inference of these findings cannot be established.

Conclusion

In this large multi-ethnic population-based cohort, we report on ethnic and sex differences in degree of AV thickness. Hispanic ethnicity was strongly protective against increased AV thickness. This effect was not related to traditional vascular risk factors, suggesting that an unmeasured factor related to Hispanic ethnicity and AV thickness may be responsible. The Hispanic population, despite being the largest minority ethnic group in the US, is grossly understudied in terms of cardiovascular risk. More research is warranted to explore the link between calcific AV disease, atherosclerosis and vascular events among Hispanics.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lindroos M, Kupari M, Heikkila J, et al. Prevalence of aortic valve abnormalities in the elderly: an echocardiographic study of a random population sample. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21(5):1220–5. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90249-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart BF, Siscovick D, Lind BK, et al. Clinical factors associated with calcific aortic valve disease. Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29(3):630–4. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00563-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otto CM, Lind BK, Kitzman DW, et al. Association of aortic-valve sclerosis with cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(3):142–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman RV, Otto CM. Spectrum of calcific aortic valve disease: pathogenesis, disease progression, and treatment strategies. Circulation. 2005;111(24):3316–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.486738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan KL. Is aortic stenosis a preventable disease? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(4):593–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00786-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohler ER., 3rd Mechanisms of aortic valve calcification. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94(11):1396–402. A6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, et al. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111(10):1233–41. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez C, Pablos-Mendez A, Palmas W, et al. Comparison of modifiable determinants of lipids and lipoprotein levels among African-Americans, Hispanics, and Non-Hispanic Caucasians > or =65 years of age living in New York City. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89(2):178–83. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albert MA, Glynn RJ, Buring J, et al. C-reactive protein levels among women of various ethnic groups living in the United States (from the Women’s Health Study) Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(10):1238–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bild DE, Detrano R, Peterson D, et al. Ethnic differences in coronary calcification: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Circulation. 2005;111(10):1313–20. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157730.94423.4B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willens HJ, Chirinos JA, Hennekens CH. Prevalence and clinical correlates of mitral annulus calcification in Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2007;20(2):191–6. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budoff MJ, Yang TP, Shavelle RM, et al. Ethnic differences in coronary atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(3):408–12. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01748-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sacco RL, Anand K, Lee HS, et al. Homocysteine and the risk of ischemic stroke in a triethnic cohort: the NOrthern MAnhattan Study. Stroke. 2004;35(10):2263–9. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000142374.33919.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novaro GM, Katz R, Aviles RJ, et al. Clinical factors, but not C-reactive protein, predict progression of calcific aortic-valve disease: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(20):1992–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agmon Y, Khandheria BK, Meissner I, et al. Aortic valve sclerosis and aortic atherosclerosis: different manifestations of the same disease? Insights from a population-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(3):827–34. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiller NB, Shah PM, Crawford M, et al. Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two-dimensional echocardiography. American Society of Echocardiography Committee on Standards, Subcommittee on Quantitation of Two-Dimensional Echocardiograms. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1989;2(5):358–67. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(89)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reaven PD, Thurmond D, Domb A, et al. Comparison of frequency of coronary artery calcium in healthy Hispanic versus non-Hispanic white men by electron beam computed tomography. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92(10):1198–200. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McClelland RL, Chung H, Detrano R, et al. Distribution of coronary artery calcium by race, gender, and age: results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Circulation. 2006;113(1):30–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.580696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorlie PD, Backlund E, Johnson NJ, et al. Mortality by Hispanic status in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270(20):2464–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liao Y, Cooper RS, Cao G, et al. Mortality from coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease among adult U.S. Hispanics: findings from the National Health Interview Survey (1986 to 1994) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30(5):1200–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stern MP, Wei M. Do Mexican Americans really have low rates of cardiovascular disease? Prev Med. 1999;29(6 Pt 2):S90–5. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunt KJ, Resendez RG, Williams K, et al. All-cause and cardiovascular mortality among Mexican-American and non-Hispanic White older participants in the San Antonio Heart Study- evidence against the “Hispanic paradox”. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(11):1048–57. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D’Agostino RB, Jr., Burke G, O’Leary D, et al. Ethnic differences in carotid wall thickness. The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Stroke. 1996;27(10):1744–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.10.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rumberger JA, Simons DB, Fitzpatrick LA, et al. Coronary artery calcium area by electron-beam computed tomography and coronary atherosclerotic plaque area. A histopathologic correlative study. Circulation. 1995;92(8):2157–62. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.8.2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doherty TM, Tang W, Dascalos S, et al. Ethnic origin and serum levels of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 are independent predictors of coronary calcium mass measured by electron-beam computed tomography. Circulation. 1997;96(5):1477–81. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.5.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bosse Y, Mathieu P, Pibarot P. Genomics: the next step to elucidate the etiology of calcific aortic valve stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(14):1327–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldbarg SH, Elmariah S, Miller MA, et al. Insights into degenerative aortic valve disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(13):1205–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roux AV Diez, Detrano R, Jackson S, et al. Acculturation and socioeconomic position as predictors of coronary calcification in a multiethnic sample. Circulation. 2005;112(11):1557–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.530147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galante A, Pietroiusti A, Vellini M, et al. C-reactive protein is increased in patients with degenerative aortic valvular stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(4):1078–82. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01484-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henry YM, Eastell R. Ethnic and gender differences in bone mineral density and bone turnover in young adults: effect of bone size. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11(6):512–7. doi: 10.1007/s001980070094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiel DP, Kauppila LI, Cupples LA, et al. Bone loss and the progression of abdominal aortic calcification over a 25 year period: the Framingham Heart Study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;68(5):271–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02390833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]