Abstract

The Opioid Growth Factor (OGF) – OGF receptors (OGFr) axis plays an important role in the homeostasis and re-epithelialization of the mammalian cornea. This tonically active growth regulatory inhibitory pathway is involved in cell replication, and the endogenous neuropeptide OGF targets cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors, p16 and/or p21. Blockade of OGF-OGFr interfacing by systemic or topical administration of opioid antagonists such as naltrexone (NTX) results in accelerated DNA synthesis, cell replication, and tissue repair. Molecular manipulation of OGFr using sense constructs delays corneal re-epithelialization, whereas antisense constructs accelerated repair of the corneal surface. Corneal keratopathy, a significant complication of diabetes mellitus, is manifested by delays in corneal re-epithelialization following surgery, injury, or disease. Tissue culture studies have shown that addition of NTX stimulates DNA synthesis and explant outgrowth of rabbit corneal epithelium, whereas OGF depresses DNA synthesis and explant outgrowth in a receptor-mediated manner. NTX accelerated corneal re-epithelialization in organ cultures of human and rabbit cornea. Systemic application of NTX to the abraded corneas of rats, and topical administration of NTX to the injured rabbit ocular surface, increased re-epithelialization. Systemic injections or topical administration of NTX facilitates re-epithelialization of the cornea in diabetic rats. Given the vital role of the corneal epithelium in maintaining vision, the frequency of corneal complications related to diabetes (diabetic keratopathy), and the problems occurring in diabetic individuals postoperatively (e.g., vitrectomy), and that conventional therapies such as artificial tears and bandage contact lenses have failed, topical application of NTX merits clinical consideration.

Keywords: Cornea, Wound Healing, Diabetes, Naltrexone, Opioids

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus [28] is a chronic disease characterized by hyperglycemia and complications that include retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and keratopathy. With the increased awareness on the prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, the long term complications of this disease pose significant clinical and financial burdens on the United States, as well as the worldwide economies. Clinical [10,61] and laboratory studies [2,27,28] have implicated hyperglycemia in the pathogenesis of long-term complications. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial [24] has concluded that intensive therapy of hyperglycemia by insulin is effective in delaying the onset and slowing the progression of complications in patients with type 1 diabetes. Nonetheless, there are few treatments that directly and specifically target complications in type 1 or 2 diabetes.

1.1. Diabetic Keratopathy

1.1.1 Definition

The intact corneal epithelium serves as a barrier against ocular infection, and contributes to the maintenance of corneal transparency and rigidity [58]. Injury to the epithelium requires prompt resurfacing in order to re-establish visual function [40,58]. Unlike normoglycemic persons who have epithelial defects that rapidly heal, individuals with diabetes present with corneal epithelial defects that may persist and be unresponsive to conventional treatment regimens [8,23,32,34,78]. This complication is known as diabetic keratopathy [19,55,89,82,93]. Abnormalities in corneal re-epithelialization are associated with persistent epithelial defects [32,36], infectious corneal ulcers [50], decreased corneal sensitivity [53,94], increased epithelial fragility, secondary scarring, punctate keratopathy, edema, and loss of vision [19,77,89].

1.1.2. Incidence

Diabetes remains one of the leading causes of vision loss and irreversible blindness [30,76] with much of the research focused on retinal complications and cataract formation. However in the last 3 decades the awareness of corneal complications has increased [30,34,49,92,93,99]. Corneal erosions/abrasions, ranging from superficial erosions to extensive, full thickness, confluent epithelial lesions, have been reported to occur in 47% to 64% of diabetic patients [93]. With 1 million individuals estimated to have type I diabetes, and more than 18 million persons characterized with type 2 diabetes, it can be estimated that hundreds of thousands of patients at some time during the course of their lifetime will experience diabetic keratopathy. Several studies [18,32] report increased incidence in complications following vitrectomy surgery in patients with diabetes compared to non-diabetics. Moreover, diabetes has been implicated as factor compromising the cornea following penetrating keratoplasty [17], pars plana vitrectomy [8], and argon laser iridectomy [53,94]. Finally, the corneal status of diabetic patients may make them poor candidates for refractive surgery [89].

1.1.3. Pathology

Pathological changes in the corneal epithelium that accompany diabetic keratopathy include i) changes in corneal morphology and fragility (e.g., varying number of cell layers, decrease in the number of cells) [33,34,80,84,88], ii) basement membrane thickening [4,48], iii) decreased epithelial adherence and healing rate [38,39,71,97,100], and iv) endothelial fluid pump dysfunction [41,42,77,98]. Metabolic abnormalities include i) decreased oxygen consumption and uptake [43], ii) increased permeability to fluorescein, and iii) increased sorbitol concentrations [112].

Corneal complications in the diabetic cornea, particularly with respect to wound healing have been documented [16,37,47,54,68,74,106,111] in both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetic animal models. At the cellular and molecular level, decreased numbers of epithelial hemidesmosomes, increased expression of glycosyltransferases, and advanced glycation end (AGE) products, and altered epithelial basement membrane (BM) have been described in human and animal diabetic corneas [1,4,35,56,66,69,71,87,89,91,109]. Changes in matrix metalloproteinases have also been implicated in the integrity and rate of repair for full thickness corneal wounds [22,60,70]. Human diabetic corneas have decreased expression of major corneal epithelial BM components, laminin-10, nidogen-1, and the laminin-binding integrin α3β1 [66–68,85,86]. Under high glucose conditions, Lu and colleagues [69] found the loss of homeostatic levels of laminin-5, and correlated this to weakening of epithelial cell adhesion, resulting in the clinical manifestation of diabetic keratopathy. The expression of respective genes was not reduced in patients with diabetic retinopathy (DR), ruling out a possible decrease of synthesis [86]. Another explanation for the observed changes (i.e., increased degradation) was corroborated by a finding of elevated expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-10 and MMP-3 in DR corneas [86]. These enzymes are able to degrade various laminin isoforms and nidogen-1 [2,65,81], and Takahashi and coworkers [101] have reported an enhancement of MMP activity in healing corneal epithelium, both in vitro and in vivo suggesting involvement in diabetic keratopathy. Changes observed in ex vivo corneas were fully reproduced in a corneal organ culture model [54]. Saghizadeh and colleagues [87] hypothesized that alterations of additional proteases, growth factors/cytokines, and BM components may occur in diabetic and DR corneas and utilized microarray technology to address the question. These workers [87] reported abnormalities in the expression of cathepsin F, laminin α4 chain, MMP inhibitor TIMP-4, and several growth factors and their receptors (HGF receptor, c-met, fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-3, its receptor FGF3), supporting their hypothesis. Using the diabetic Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rat model of type 2 diabetes, Wakuta and coworkers [106] have found that connexin43, K14, and Ki-67 were all restricted to the single layer of basal cells in the corneal epithelium of Wistar rats, but was detected in the two layers of cells closest to the BM in GK rats, and suggest that this is an indication of an immature phenotype.

1.1.4. Current Therapies

Diabetic keratopathy is currently treated with lubricants and antibiotics, bandage contact lens, and tarsorrhaphy, all therapies that try to create a more favorable environment for wound healing. However, these methods frequently are inadequate at accelerating re-epithelialization in type 1 diabetes. The failure of conventional methods in corneal epithelial wound repair are not just related to pain and inconvenience, but provide a window for infection that can lead to devastating and irreparable vision problems. Moreover, none of the present therapies address the fundamental pathobiology of delayed corneal healing secondary to diabetes. Therefore, it is vital that novel methods for the treatment of this complication of type 1, and most likely type 2, diabetes be devised and explored, and brought to clinical trial.

2. Endogenous Opioids and Diabetes

Native opioid peptides, such as endorphins and enkephalins, are derived from 3 major prohormones, and interact with both classical and non-classical opioid receptors. Initially studied for their role as neurotransmitters, endogenous opioids have been shown to be present in neural and non-neural tissues, and to evoke a number of functions other than neuromodulation. One well studied role of enkephalins, specifically methionine enkephalin, is that of growth regulation [51,72,125]. A few studies have suggested that these peptides also play a role in pancreatic endocrine secretion [9,31], and influence glucose metabolism or homeostasis [29]. A number of reports have investigated the relationship of opioids to diabetes [5,6,25,29,44–46,57,59,64,75,103,104,108].

Studies concerned with circulating opioid levels in diabetes mellitus have shown that patients with type 1 diabetes do not demonstrate any significant change in β-endorphin plasma levels [105], whereas very high plasma [Met5]-enkephalin levels have been recorded [29,75]. Elevated levels of [Met5]-enkephalin also have been reported in genetically obese diabetic (db/db) mice [44,104]. Finally, the diabetic condition has been reported to be accompanied by diminished nociception and an exaggerated antinociceptive effect from exogenously administered opioids [21,45,64,79].

3. OGF-OGFr Axis, Cellular Renewal, and Re-epithelialization

Endogenous opioid peptides serve to regulate the growth of developing, neoplastic, renewing, and healing tissues, and function in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes [137]. One native opioid peptide, [Met5]-enkephalin, has emerged as a receptor-mediated growth factor; this peptide is encoded by the preproenkephalin A (PPE) gene. To distinguish the role of [Met5]-enkephalin as a growth factor in neural/nonneural cells and tissues from its function as a neurotransmitter/ neuromodulator, this peptide has been termed opioid growth factor (OGF). OGF is a potent, reversible, species and tissue nonspecific peptide that is a negative growth regulator. This peptide is autocrine and possibly paracrine produced, secreted, and effective at concentrations consistent with growth effects and the binding affinity of its receptor - OGFr. OGF action is targeted to DNA synthesis, and in particular, the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle; excess OGF elongates the G0/G1 phase, indicating the negative regulation of this peptide [11–13]. Studies on corneal epithelial outgrowths have shown that OGF also has an inhibitory influence on cell proliferation, migration, and tissue organization [125]. Blockade of OGF-OGFr interaction using NTX increases the rate of growth, decreases the length of DNA synthesis and mitotic phases of the cell cycle, decreases doubling time [72,117,127–129,134], and stimulates restoration of homeostasis and wound repair [123]. The receptor for OGF has been cloned and sequenced in humans, rats, and mice, and bears no resemblance to classical opioid receptors in nucleotide or protein sequences [137]. Blockade of OGF-OGFr interaction with the use of opioid antagonists such as NTX, neutralization with antibodies to OGF, and antisense experiments with OGFr result in accelerated growth and cell division [73,118,124,126,136,137].

4. Endogenous Opioids, Opioid Receptors, and the Eye

4.1. Presence and Location in the Eye

The presence in the eye of endogenous opioids having a role in neurotransmission was initially detected in amacrine cells and cellular processes within the retinal inner plexiform layer [7,96,102,110]. Enkephalins serving as growth factors were identified in the retina by Isayama and coworkers [51], and the precursor for OGF, preproenkephalin A mRNA, were detected in neonatal rat retina [52] and developing brain [114], with the peptide OGF present and functioning as early as the first week of life in rats. OGF mRNA was detected in both the basal and suprabasal cells of the central and peripheral cornea, limbus, and conjunctiva by in situ hybridization suggesting that OGF is derived in an autocrine manner, thereby permitting local control of homeostatic cellular replication [135].

Immunocytochemical examination of vertebrate corneas from a wide variety of classes of the phylum Chordata, including mammalia, aves, reptilia, amphibia, and osteichthyes, showed that the OGF-OGFr axis may have originated at least as early as 300 million years ago, and that the function of this system in cellular renewal and homeostasis is a requirement of the vertebrate corneal epithelium [90,122]. Robertson and Andrew [82] have extended these reports on this endogenous opioid system in the corneal epithelium of the dog and the horse, and have suggested that this peptide-receptor system may be of importance in homeostasis and re-epithelialization of all mammalian corneas.

Laser scanning confocal microscopy and ultrastructural studies confirmed the presence of peptide and receptor in both the cytoplasm and nucleus using immunoelectron microscopy staining [121]. Immunogold labeling of OGFr was detected on the outer nuclear envelope, in the paranuclear cytoplasm proximal to the nuclear envelope, perpendicular to the nuclear envelope in a putative nuclear pore complex, and within the nucleus adjacent to heterochromatin. Immunogold labeling for OGF was noted in locations similar to that for OGFr, as well as throughout the cytoplasm, and subjacent to the plasma membrane. These results suggest that OGFr resides on the outer nuclear envelope where it interacts with OGF, and that the colocalized peptide and receptor translocate at the nuclear pore into the nucleus. Many of these observations have been confirmed in cell culture studies of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck using fluorescently tagged OGFr (i.e., OGFr-eGFP) [14].

4.2. Opioid Antagonists and Re-epithelialization

Two of the most widely used opioid antagonists in clinical practice are naloxone (Narcan) and naltrexone (NTX) (Trexan, Revia). These compounds are FDA approved for reversal of opioid drug overdose and treatment of alcoholism. Naloxone is a short-acting, antagonist whereas NTX is longer acting and more potent than naloxone; neither compound has any direct biological activity. Both antagonists are active at the classical opioid receptors (µ, δ, κ) as well as OGFr. A large body of scientific work has focused on the function and mechanisms of action of NTX in normal and abnormal (cancer) cell and tissue systems [11–13,72,73,117–120,137]. In particular, NTX can correct the abnormal pattern of corneal wound repair in normal and diabetic animals.

4.3. Organ Culture Models of Corneal Re-epithelialization in Rat, Rabbit, and Human

Using corneal explants in a tissue culture model, the presence and location of the endogenous opioid peptide - OGF - and its receptor - OGFr – were established in mammalian corneal epithelium as modulators of cell proliferation, migration, and organization [125]. Homeostatic renewal of the ocular surface epithelium (cornea, limbus, and conjunctiva) of the mammal was studied using 3H-thymidine incorporation and autoradiography as a measure of DNA synthesis. The results revealed that cellular renewal processes (DNA synthesis) in ocular surface epithelium are governed by OGF, with peptide action being opioid receptor mediated, suggesting that OGF was a tonically active peptide because NTX increased the number of proliferating cells [123].

4.4. Corneal Re-epithelialization, Naltrexone, and Non-Diabetic Models

The role of endogenous opioids, particularly OGF, and their receptors on corneal epithelial wound closure was investigated in a variety of normal mammals. Using rat, rabbit, and human corneas in vitro, and in rat and rabbit in vivo models, the efficacy of NTX in blocking the interaction of endogenous opioids with receptors was studied [123,125–127,129]. Whether applied topically [126,127] or systemically [127], NTX has been demonstrated to markedly accelerate epithelial DNA synthesis and corneal re-epithelialization. The mechanism of action of NTX, as a general opioid receptor antagonist, is to block the interaction of opioids and their receptors whether they are classical opioid receptors such as µ, δ, or κ receptors or OGFr [137]. Studies using HNEK epithelial cells further define the OGF-OGFr pathway and highlight that this axis serves as a tonically repressive pathway for cell proliferation requiring upregulation of cyclin-dependent inhibitory kinases and nucleocytoplasmic transport [12]. The repercussions of NTX treatment of the homeostatic cornea include decreased epithelial transit time from the basal layer to the suprabasal layers, and increased in linear thickness of the epithelium, basal cell proliferation, and packing density of suprabasal cells secondary to a decrease in cell diameter [132]. Ultrastructural examination of corneal epithelium treated with NTX at a dosage that enhances corneal re-epithelialization revealed that the appearance and number of hemidesmosomes in corneas of diabetic, normoglycemic, and normal rats were comparable. Examination of the fine structure of the basal and suprabasal layers were comparable suggesting that topical application of NTX for 7 days which accelerates diabetic corneal epithelial healing within causing morphologic abnormalities in the reassembly of adhesion structures [133].

To address the question of whether opioids are restricted to rabbit wound healing, or are a fundamental part of mammalian re-epithelialization, the effects of opioid receptor blockade by NTX were examined after abrasion of the rat corneal epithelial surface. A 4 mm diameter epithelial defect was made in the center of the rat cornea. NTX injected i.p. twice daily or applied as eye drops 4 times daily significantly accelerated re-epithelialization compared to controls. Beginning as early as 8 hr after wounding, both the systemic and topical NTX treatment groups had epithelial defects that were approximately 10% to 67% smaller than abrasions in control animals at the time points examined. Similarly, the rate of healing for the NTX groups was 4.7- and 2.8-fold greater than controls for systemic and topical paradigms, respectively. The incidence of complete re-epithelialization in animals given systemic administration of NTX was markedly accelerated in comparison to control rats; however, differences in the rate of repair between NTX and control groups receiving topical application were not observed. These results show that native opioid peptides function in wound healing of the mammalian corneal surface, and exert a tonic inhibitory influence at the receptor level on repair of corneal epithelial injuries [126].

Although OGF and the OGF receptor are present in the ocular surface of the human cornea [122], the function of OGF interaction with OGFr required verification. Using donor human corneas in an organ culture model, 8 mm central corneal abrasions were performed, and the corneas treated by adding NTX (10−6 M) every 24 hr to the media. Re-epithelialization was monitored using fluorescein and morphometric analyses as described earlier. Data from these studies [130] showed that NTX treated corneas had 21% smaller defects than controls after 24 hr, 38% less at 48 hr, 51% less at 72 hr, and 89% less at 96 hr; all of the corneas were healed by 120 hr. In regard to incidence of complete re-epithelialization, at 72 hr 62% of the corneas were completely repaired in the NTX group in contrast to 19% of the corneas in the control group (p = 0.002, Chi Square); at 96 hr 81% of the NTX treated corneas were re-epithelialized whereas only 32% control corneas were completely closed (p = 0.0006, Chi Square); and at 120 hr all of the NTX corneas were healed in contrast to 42% of the controls.

4.5. Corneal Re-epithelialization, Naltrexone, and Diabetic Models

OGF and OGFr have been detected immunohistochemically in the corneal epithelium of several animal models of diabetes [113]. OGF and OGFr immunoreactivity have been localized to cells of the basal and suprabasal layers of the corneal epithelium and in a distribution pattern similar to that in normal human corneal epithelium [122].

4.6. Corneal Wound Healing – Uncontrolled Diabetic, Systemic Naltrexone – Rat Model

Hyperglycemia was induced in 6-week old rats (≈ 100 g) by a single injection of streptozotocin (STZ, 65 mg/kg, i.v.), pH 4.5, dissolved in 0.01 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5). This model mimicked uncontrolled type 1 diabetes with blood glucose levels of at least 4 fold higher (≥ 350 mg/dl) than controls established within one week of injection of STZ. Hyperglycemic animals displayed had urine glucose levels above 2,000 mg/dl, and consumed twice as much food and 6 times as much water as controls. The body weights of the hyperglycemic animals were more than 18% less than controls, and upon histological analysis revealed complete degranulation of pancreatic β-cells in the diabetic group [113,131].

The corneas of diabetic rats and non-diabetic animals of the same age were abraded with a 5 mm trephine, and animals divided into groups receiving either 0.5 ml of sterile saline (CS, DS) or 30 mg/kg NTX (CN, DN) twice daily at 0800 and 1600. Corneal wounds were surgically created in animals 1-, 4-, and 8-weeks following STZ induction.

4.6.1. Corneal Wound Healing in 1 and 4 Week Diabetic Rats

No differences in corneal re-epithelialization were seen between diabetic and control animals at 1 week after confirmation of diabetes [113]. However, at 4 weeks after induction of diabetes, significant delays in wound healing were noted in the DS group as compared to the CS group at 16, 24, 32, 40, and 48 h. The DS group had demonstrated a 14–23% delay in re-epithelialization within the first day after abrasion. Diabetic rats receiving NTX (DN) had 47% smaller wounds (p<0.05) than those of the DS group at 40 hr [113].

4.6.2. Corneal Wound Healing in the 8-Week Diabetic Rat

Eight weeks after induction of diabetes, diabetic rats receiving saline had significantly larger residual wound areas than recorded for non-diabetic animals (Figs. 1, 2), with wound sizes ranging 11- 183% larger in DS rats over the 40 hr period of time relative to CS animals [113]. Diabetic rats receiving NTX had a marked increase in re-epithelialization compared to diabetic animals receiving saline at all timepoints. In fact, corneal re-epithelialization of DN and CN rats was similar at all timepoints with exception to 40 and 48 h. Non-diabetic rats receiving NTX also showed an increase in wound healing compared to control animals ranging from 12% (16 h) to 78% (40 h). At 48 h after wounding 67% of the CS were completely healed compared to 0% of the DS rats. Rates of re-epithelialization recorded for the first 24 hr following surgery were faster than control animals given saline.

Figure 1.

Photographs of rat eyes stained with fluorescein immediately after (initial wound) or 24, 40, and 48 hr after creation of a 5-mm central corneal abrasion. Rats were either nondiabetic (control, C) or type 1 diabetic (D) for 8 weeks before wounding and receiving an i.p. injection twice daily of either 30 mg/kg NTX (N) or an equivalent volume of saline (S). Magnification × 1.5 Reprinted from Diabetes 51:3055–3062, 2002 [113].

Figure 2.

Histogram of percent residual epithelial defect in rat corneas after formation of a 5-mm central corneal wound. Rats were either non-diabetic (Co) or diabetic for 8 weeks (D) and receiving an i.p. injection twice daily of either 30 mg/kg NTX (N) or an equivalent volume of saline (S). Photomicrographs of the fluorescein-stained corneas were captured with a Sony CCD camera, and areas were analyzed by Optimas software. Residual epithelial defects are presented as percentage of the original wound. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Significantly different from CS at p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**) and p<0.001 (***). Significantly different from DS group at p<0.05 (+), p<0.01 (++), and p<0.001 (+++). Reprinted from Diabetes 51:3055–3062, 2002 [113].

4.6.3. Mechanism of Naltrexone Acceleration of Corneal Re-epithelialization

To begin to assess the mechanism associated with re-epithelialization, DNA synthesis was monitored by systemic (i.p.) injection of 2 µCi/g body weight [3H]-thymidine (20 Ci/mmol) 1 hr prior to euthanasia into non-wounded CS, DS, and DN animals; DN rats received an i.p. injection of 30 mg/kg NTX 4 hr prior to euthanasia. Sections of the eye including the entire corneal surface, limbus, and conjunctiva were counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin and the number of cells with 3 or more grains in the basal epithelial layer of the central cornea, peripheral cornea, limbus, and conjunctiva were counted (Fig. 3). No DNA synthesis was noted in the central cornea. A subnormal number of cells were undergoing DNA synthesis in the peripheral cornea, limbus, and conjunctiva of DS rats relative to CS rats, and in the peripheral cornea and limbus of DN rats relative to CS animals with reductions in labeled cells being 81 to 90% of control levels. Administration of NTX for the 4 hr period increased DNA synthesis in the diabetic rats by 4-fold, 3.5-fold, and 8-fold relative to DS rats in the number of radiolabeled basal epithelial cells in the peripheral cornea, limbus, and conjunctiva, respectively.

Figure 3.

Histogram of the labeling indexes of basal epithelial cells in the peripheral cornea, limbus, and conjunctiva of control (Co) or diabetic (D) rats receiving saline (S) or a single i.p. injection of 30 mg/kg NTX (N) 4 hr prior to euthanasia. [3H]-thymidine was administered 1 hr prior to euthanasia. Data represent means ± SEM. Significantly different from CS at p<0.01 (**) and p<0.001 (***). Reprinted from Diabetes 51:3055–3062, 2002 [113].

5. Corneal Wound Healing – Insulin-Controlled and Uncontrolled Diabetic, Topical Naltrexone

Studies conducted earlier [113] focused on rats that had uncontrolled diabetes and were treated systemically. To facilitate comparisons to the general human condition, most type 1 diabetic patients attempt to control their hyperglycemia by administration of insulin. Thus, we established an animal model of STZ induced type 1 diabetes with insulin minipumps implanted so that the blood glucose levels were relatively normal [107]. Studies showed that insulin supplementation of STZ-induced diabetes enhanced hemodynamic responses to enkephalins [95]. Moreover, topical administration of NTX, if non-toxic and feasible, would lead to more compliance with easier and less invasive therapy. This non-invasive treatment regimen was based on earlier work [126,127,130,131] using non-diabetic rat and rabbit, as well as human donor corneas examining the role of NTX in organ culture.

5.1. Corneal Safety of Topically Applied Naltrexone

Six week old male Sprague-Dawley rats were induced with STZ and confirmed to be hyperglycemic (blood glucose >350 mg/dl). Within 7 days of STZ injections, rats were implanted with insulin pellets (LinShin) and blood glucose levels dropped to ~150 mg/dl (normoglycemic). In addition, the body weights of insulin-controlled rats were significantly heavier than those of uncontrolled hyperglycemic rats, and approached the body weight levels of normal rats throughout the 11-week experiment.

5.2. Noninvasive Measurements of Corneal Integrity

Studies to determine the toxicity of NTX applied topically were conducted on Normal and type 1 diabetic rats using intact corneas [115], as well as rats that had abraded corneas [62]. Using intact corneas, concentrations of 10−3 M to 10−7 M NTX as well as vehicle (Vigamox, Alcon) were applied 4 times daily for 7 days. Diabetic (DB) rats were insulin-controlled (DB-IN) or uncontrolled (DB), or non-diabetic (Normal). In addition to examining the surface morphology of the eye, noninvasive measurements included ocular pressure, corneal thickness, and corneal sensitivity. These measurements of corneal integrity were assessed on both eyes of all rats 3–4 days prior to NTX administration and at 7 and 14 days following NTX. Thus comparisons for toxicity of NTX treatment to one eye could be assessed within an animal (treated and untreated eye), cross time (immediately before surgery and after), and immediately after NTX application as well as 7 days later. Overall corneal topography was assessed with a hand held slit-lamp, and the presence of cataracts noted. Corneal thickness was determined by a pachymeter; both of these parameters were measured on anesthetized animals. Intraocular pressure was measured on unanesthetized rats using a tonopen, whereas corneal sensitivity was recorded with a Cochet and Bonnet aesthesiometer. No changes in corneal thickness or intraocular pressure were noted between any groups. Uncontrolled DB rats presented with bilateral cataracts in 88% of the animals 10 weeks after induction of STZ; 13% of insulin controlled rats had cataracts and Normal rats had no cataracts.

Toxicity was also measured by examination of apoptosis, necrosis, and assessment of endothelial cell counts. No changes were noted.

Similar evaluations were conducted on animals receiving the corneal surgery (Fig. 4), and no significant changes were noted between groups of rats receiving NTX or SV. Observations of the retina and surround blood vessels were made using a fundoscope (Fig. 5). No pathology was associated with any group of rats or with any topical NTX treatment. Formation of exudates and hemorrhages were not apparent and the optic disc and cup appeared normal. Diabetic rats observed with the fundoscope did not have cataracts.

Figure 4.

Corneal thickness (A) and intraocular pressure (B) of rats rendered diabetic (DB) with streptozotocin, diabetic animals receiving insulin and maintained as normoglycemic (DB-IN), and non-diabetic rats receiving vehicle (Normal) at 8 weeks following streptozotocin injection. Values represent measurements taken 7 days after receiving 4 times daily topical application of either sterile vehicle (SV; n=8) or 10−5 M NTX (NTX; n= 16). Values represent means ± SEM. Reprinted from J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 23:89–102 [62].

Figure 5.

Fundoscope images of eyes from rats in the diabetic (DB), diabetic-insulin (DB-IN), and Normal groups at 10 weeks following induction of diabetes with Streptozotocin and 2 weeks following wounding. Rats received naltrexone or sterile vehicle 4 times/day for 7 days. No differences in the retina, optic nerve, and surrounding blood vessels were observed. Magnification 5.8×. Reprinted from J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 23:89–102 [62].

6. Efficacy of Naltrexone to Re-epithelialize Central Corneal Abrasions

The 5 mm diameter trephine demarcated nearly the entire corneal region without encroaching on the limbus or conjunctiva. Only those corneal wounds that had initial sizes of 17.3 to 25.1 mm2 were included in evaluations, and the mean diameter for corneal wounds did not differ among any group. Corneal wounds in DB SV rats healed significantly slower than those in non diabetic Normal animals (Fig. 6). However, DB rats receiving NTX demonstrated significant enhancement in re-epithelialization with 25 – 83% smaller wounds than corresponding DB animals. At 16, 24, and 40 hr, all dosages of NTX had significantly smaller residual epithelial defects than DB SV rats, and at 32 hr, only 10−4 M and 10−5 M NTX was significantly smaller. At 16 and 24 hr, the residual epithelial defects in DB rats treated with NTX were significantly smaller than wound sizes in Normal animals.

Figure 6.

(A) Photographs of diabetic (DB) rat eyes stained with fluorescein after wounding and receiving naltrexone (NTX) or sterile vehicle (SV) 4 times/day. Normal SV rats are included for comparison. (B) Residual epithelial defects (means ± SEM) are calculated as percentage of the original wound. Significantly different from DB SV rats at p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**) and p<0.001 (***), and from Normal SV rats at p<0.05 (#), p<0.01 (##), and p<0.001 (###). Significantly different from the DB 10−6 M NTX group at p<0.05 (+) and p<0.01 (++). Reprinted from J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 23:89–102 [62].

DB-IN rats receiving any of the 3 dosages of NTX had corneal wounds that re-epithelialized faster than DB-IN animals receiving SV (Fig. 7). Residual defects were up to 93% smaller (p<0.001) in those rats in the group treated with topical NTX relative to DB-IN rats receiving SV. No dose dependent effect was noted for NTX, with all groups demonstrating smaller wound sizes relative to DB-IN SV rats. Analyses of the mean time of closure of corneal epithelial wounds in the DB SV group and the DB-IN SV group revealed a markedly longer period of time required for the uncontrolled DB animals to completely close in comparison to those animals receiving insulin (DB-IN SV).

Figure 7.

(A) Photographs of diabetic-insulin (DB-IN) rat eyes stained with fluorescein after wounding and receiving naltrexone (NTX) or sterile vehicle (SV) 4 times/day. Normal SV rats are included for comparison. (B) Residual epithelial defects (means ± SEM) are calculated as percentage of the original wound. Significantly different from DB-IN rats receiving SV at p<0.01 (**) and p<0.001 (***), and from Normal SV rats at p<0.05 (#), p<0.01 (##), and p<0.001 (###). At 24 hr, the 10−4 M NTX DB-IN group differed from the 10−5 M NTX DB-IN group at p<0.05 (^) and from the 10−6 M NTX DB-IN group at p<0.001 (+++). Reprinted from J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 23:89–102 [62]

7. Efficacy of Insulin and Naltrexone to Re-epithelialize Corneal Wounds

As mentioned previously, hyperglycemic rats rendered normoglycemic through the use of insulin minipumps demonstrated that corneal wounds healed faster than those in uncontrolled hyperglycemic animals [131]. Moreover, if NTX was administered topically to diabetic rats receiving insulin by minipump, wounds healed more rapidly than in those normoglycemic rats receiving vehicle. Subsequent experiments examining the efficacy of direct topical application of insulin (1 U/drop) to corneas of type 1 diabetic rats, uncontrolled for hyperglycemia, 4 times daily for 7 days revealed that insulin was efficacious in healing abraded corneas relative to vehicle alone [116]. Moreover, topical insulin did not alter corneal thickness, intraocular pressure or serum glucose. Concomitant administration of topical NTX (10−5 M) and insulin (1 U/0.05 ml) provided no additive effects at corneal restoration [63].

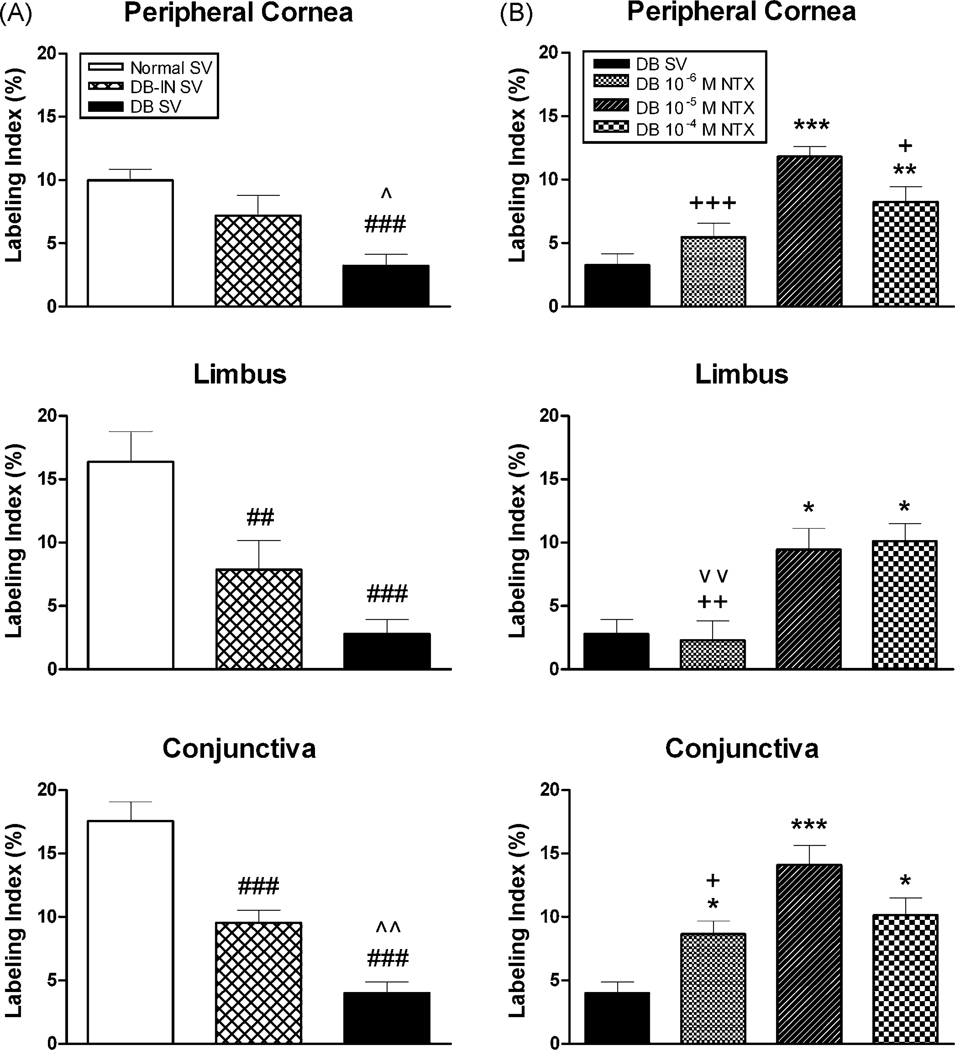

8. Mechanisms of Action: Naltrexone Targets DNA Synthesis

Re-epithelialization can occur through a number of processes including increased cellular proliferation or migration, or reduction in apoptosis/necrosis. Detailed studies in our laboratory on neoplastic cells in culture [72,118–120], as well as examination of corneal explants in culture [125] have demonstrated that NTX influences cell proliferation substantially more than cellular processes of migration, adhesion, or differentiation [119,120]. Moreover, apoptosis as measured by caspase 3 activity detecting early stages of programmed cell death, or TUNEL to detect late stages, or necrosis as evidence by hematoxylin stained sections was not present in NTX treated specimen supporting that neither apoptosis nor necrosis play a role in NTX’s effect on re-epithelialization [118]. However, studies have demonstrated that NTX treatment enhances both DNA synthesis and mitosis [128,129,134]. Furthermore, cell cycle pathways, and particularly cyclin dependent inhibitory kinase pathways are prime targets of the OGF-OGFr axis [12,13]. In the current studies, the number of BrdU labeled cells, a measure of DNA synthesis, were significantly diminished in DB-SV rats relative to Normal rats receiving SV (Fig. 8); decreases of 68 – 83% were noted in the basal cell layer of the peripheral cornea, limbus, and conjunctiva. Insulin-controlled diabetic rats (DB-IN SV) had decreases in DNA synthesis of ~50%. Topical application of NTX (10−4 M and 10−5 M) increased DNA synthesis in the diabetic rats to levels of those observed in Normal SV animals, supporting significant normalization of the re-epithelialization processes with NTX.

Figure 8.

Labeling indexes (means ± SEM) in basal epithelial cells, as measured by BrdU incorporation 2 weeks after abrasion. (A) Comparison of Normal, diabetic-insulin (DB-IN) and DB groups given sterile vehicle (SV). Significantly different from Normal SV within a region at p<0.01 (##) and p<0.001 (###), and from the DB-IN SV group at p<0.05 (^) and p<0.01 (^^). (B) DB rats receiving topical application of naltrexone (NTX) 4 times daily for 7 days; BrdU measurements taken 7 days after cessation of therapy. Significantly different from the DB SV group at p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**), and p<0.001 (***); from the DB 10−5 M NTX group at p<0.05 (+), p<0.01 (++) or p<0.001 (+++), and the DB 10−4 M NTX group at p<0.01 (^^). Data were recorded from 4–6 grids (50 × 290 µm)/section, 2 sections/region (peripheral cornea, limbus, or conjunctiva), and 3 rats/group. Reprinted from J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 23:89–102 [62].

9. Targeted Pathway of the OGF-OGFr Axis

Recent studies have identified the pathway targeted by the OGF-OGFr axis [11–13]. OGF is an endogenous opioid peptide, chemically termed [Met5]-enkephalin that serves as tonically active inhibitory growth factor. OGF inhibits cell proliferation by altering the G1-S phases of the cell cycle. Using human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), human epidermal keratinocytes, human dermal fibroblasts and mesenchymal stem cells, we have documented that OGF action is dependent on induction of the p16INK4a and p21WAF/CIP1 protein expression. In turn, these cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors retard progression through the cell cycle. Attenuation of either p16 or p21 was not sufficient to inhibit cell proliferation; both kinases are required for activity [12]. This requirement for intact p16 and p21 is not in place for the signaling pathway in neoplasia. In head and neck cancer, p21 is often deleted, and only p16 functions [13], whereas in pancreatic cancers, p21 is the point of regulation [11]. Moreover, we have utilized NTX labeled with fluorescein (FNTX) to determine that NTX enters the cells by passive diffusion in a non-saturable manner [14]. FNTX was tracked inside the nucleus within 1 min and remained in the cells for 48 h supporting the rapid response of NTX treatment on DNA synthesis and subsequent cell proliferation.

Although the AKT signaling pathway has been shown to be altered in diabetes [111] and addition of N-acetylcysteine and heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor accelerated corneal epithelial wound closure, the OGF-OGFr axis has not been shown to play a direct role in altering proliferation by way of the AKT pathway.

10. Significance

Current ophthalmic literature reveals that homeostasis and repair of wounds in diabetic patients are compromised, and that treatment modalities are limited. While the literature supports that there may be alterations in levels of endogenous opioids in diabetic individuals, treatment modalities do not target the physiological processes associated with diabetic keratopathy. The OGF-OGFr axis appears to be present in all vertebrate cornea epithelia and functioning to maintain corneal homeostasis and to restore corneal epithelialization. Blockade of this axis by opioid antagonists such as NTX enhanced DNA synthesis and accelerated re-epithelialization in both non-diabetic and uncontrolled or insulin-controlled diabetes. In many cases, NTX restores diabetic keratopathy, bringing the re-epithelialization processes to the level of Normal, consequently exceeding rates of repair for DB or DB-IN rats. Both systemic and topical application of NTX is effective, with a 10,000 fold range of NTX dosages tested topically. In no case was toxicity noted in corneas following at least 7 days of applications (four times daily). In summary, our in vitro and in vivo findings strongly support clinical trials for the use of NTX as a topical therapy for diabetic keratopathy.

11. Summary

Given the vital role of the corneal epithelium in maintaining vision, the frequency of corneal complications related to diabetes (diabetic keratopathy), and the problems occurring in diabetic individuals postoperatively (e.g., vitrectomy, cataract extraction) in which the ocular surface epithelium is disturbed, and that conventional therapies such as artificial tears and bandage contact lenses have failed, topical application of NTX merits consideration. NTX offers many advantages, including availability, chemical consistency, easy preparation, limited dosing (4 times daily), cost-effectiveness, and fast rates of absorption. Moreover, patients taking NTX systemically demonstrate that the drug does not induce tolerance, has no toxicity or adverse effects, and exhibits minimal immunological reaction.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was support in part by grants from the National Eye Institute, NIH EY13086, EY13734, and EY016666.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akimoto Y, Kawakami H, Yamamoto K, Munetomo E, Hida T, Hirano H. Elevated expression of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins and O-GlcNAc transferase in corneas of diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:3802–3809. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander CM, Howell EW, Bissell MJ, Werb Z. Rescue of mammary epithelial cell apoptosis and entactin degradation by a tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 transgene. J. Cell Biol. 1996;135:1669–1677. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aschner P. Current concepts of diabetes mellitus. Int. Ophthalmol. Clinics. 1998;38:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azar DT, Spurr-Michaud SJ, Tisdale AS, Gipson IK. Decreased penetration of anchoring fibrils into the diabetic stroma. A morphometric analysis. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1989;107:1520–1523. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020594047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berman Y, Devi L, Carr KD. Effects of streptozotocin-induced diabetes on prodynorphin-derived peptides in rat brain regions. Brain Res. 1995;685:129–134. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00419-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berman Y, Devi L, Spangler R, Kreek MJ, Carr KD. Chronic food restriction and streptozotocin-induced diabetes differentially alter prodynorphin mRNA levels in rat brain regions. Mol. Brain Res. 1997;46:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brecha N, Karten HJ, Laverack C. Enkephalin-containing amacrine cells in the avian retina: Immunohistochemical localization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:3010–3014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.6.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brightbill FS, Myers FL, Bresnick GH. Postvitrectomy keratopathy. Amer. J. Ophthalmol. 1978;85:651–655. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruni JF, Watkins WB, Yen SSC. β-endorphin in the human pancreas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1979;49:649–651. doi: 10.1210/jcem-49-4-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chase HP, Jackson WE, Hoops SL, Cockerham RS, Archer PG, O'Brien D. Glucose control and the renal and retinal complications of insulin-dependent diabetes. JAMA. 1989;261:1155–1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng F, McLaughlin PJ, Verderame MF, Zagon IS. The OGF-OGFr axis utilizes the p21 pathway to restrict progression of human pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2008;7:5–17. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng F, McLaughlin PJ, Verderame MF, Zagon IS. The OGF-OGFr axis utilizes the p16INK4a and p21WAF1/CIP1 pathways to restrict normal cell proliferation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:319–327. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng F, Zagon IS, Verderame MF, McLaughlin PJ. The opioid growth factor (OGF)-OGF receptor axis uses the p16 pathway to inhibit head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10511–10518. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng F, McLaughlin PJ, Banks WA, Zagon IS. Passive diffusion of naltrexone into human and animal cells and upregulation of cell proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2009;297 doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00311.2009. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheung CY, Tang F. The effect of streptozotocin-diabetes on β-endorphin level and proopiomelanocortin gene expression in the rat pituitary. Neurosci. Letters. 1999;261:118–120. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)01008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chikama T, Wakuta M, Liu Y, Nishida T. Deviated mechanism of wound healing in diabetic corneas. Cornea. 2007;26 Suppl. 1:S75–S81. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31812f6d8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou L, Cohen EJ, Laibson PR, Rapuano CJ. Factors associated with epithelial defects after penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmic Surg. 1994;25:700–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung J, Tolentino FI, Cajita VN, Acosta J, Refojo MF. Reevaluation of corneal complications after closed vitrectomy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1988;106:916–919. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060140062025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cisarik-Fredenburg P. Discoveries in research on diabetic keratopathy. Optometry. 2001;72:691–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark CM, Lee DA. Prevention and treatment of the complications of diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332:1210–1217. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Courteix C, Bourget P, Caussade F, Bardi M, Coudore F, Fialip J, Eschalier A. Is the reduced efficacy of morphine in diabetic rats caused by alterations of opiate receptors or of morphine pharmacokinetics? J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therap. 1998;285:63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daniels JT, Geerling G, Alexander RA, Murphy G, Khaw PT, Saarialho-Kere U. Temporal and spatial expression of matrix metalloproteinases during wound healing of human corneal tissue. Exp. Eye Res. 2003:653–664. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Datiles MB, Kador PF, Fukui HN, Hu T-S, Kinoshita JH. Corneal re-epithelialization in galactosemic rats. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1983;24:563–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. New Eng. J. Med. 1993;329:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Salhy M, Spangeus A. Neuropeptide contents in the duodenum of non-obese diabetic mice. Acta Diabetologica. 1998;35:9–12. doi: 10.1007/s005920050094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engerman RL, Bloodworth JM, Nelson S. Relationship of microvascular disease in diabetes to metabolic control. Diabetes. 1977;26:760–769. doi: 10.2337/diab.26.8.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engerman RL, Kern TS. Progression of incipient diabetic retinopathy during good glycemic control. Diabetes. 1987;36:808–812. doi: 10.2337/diab.36.7.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus, The report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183–1197. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fallucca F, Tonnarini G, Di Biase N, D'Alessandro M, Negri M. Plasma met-enkephalin levels in diabetic patients: Influence of autonomic neuropathy. Metabolism. 1996;45:1065–1068. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(96)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feman SS. Diabetes and the eye. In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA, editors. Duane's Clinical Ophthalmology. vol. 5. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feurle GE, Helmstaedter V, Weber U. Met- and leu-enkephalin immuno- and bioreactivity in human stomach and pancreas. Life Sci. 1982;31:2961–2969. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foulks GN, Thoft RA, Perry HD, Tolentino FI. Factors related to corneal epithelial complications after closed vitrectomy in diabetics. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1979;97:1076–1078. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1979.01020010530002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friend J, Ishii Y, Thoft RA. Corneal epithelial changes in diabetic rats. Ophthalmic Res. 1982;14:269–278. doi: 10.1159/000265202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friend J, Thoft RA. The diabetic cornea. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 1984;24:111–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujita H, Morita I, Takase H, Ohno-Matsui K, Mochizuki M. Prolonged exposure to high glucose impaired cellular behavior of normal human corneal epithelial cells. Curr Eye Res. 2003;27:197–203. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.27.4.197.16598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukushi S, Merola LO, Tanaka M, Datiles M, Kinoshita JH. Reepthelialization of denuded corneas in diabetic rats. Exp. Eye Res. 1980;31:611–621. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(80)80020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giancotti FG. Integrin signaling: specificity and control of cell survival and cell cycle progression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:691–700. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gipson IK, Grill SM, Spurr SJ, Brennan SJ. Hemidesmosome formation in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 1983;97:849–857. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.3.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gipson IK, Spurr-Mirchaud SJ, Tisdale AS. Anchoring fibrils form a complex network in human and rabbit cornea. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1987;289:212–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gipson IK, Sugrue SP. Cell biology of the corneal epithelium. In: Albert DM, Jakobiec FA, editors. Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology. Philadelphia: Basic Sciences Saunders; 1994. pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goebbels M, Spitznas M. Endothelial barrier function after pacoemulsification: A comparison between diabetic and non-diabetic patients. I Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1991;229:254–257. doi: 10.1007/BF00167879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goebbels M, Spitznas M, Oldendoerp J. Impairment of corneal epithelial barrier function in diabetics. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1980;90:463–468. doi: 10.1007/BF02169787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graham CR, Richard RD, Varma SD. Oxygen consumption by normal and diabetic rat and human corneas. Ophthalmol. Res. 1981;13:65–71. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenberg J, Ellyin F, Pullen G, Ehrenpreis S, Singh SP, Cheng J. Methionine-enkephalin and β-endorphin levels in brain, pancreas, and adrenals of db/db mice. Endocrinol. 1985;116:328–331. doi: 10.1210/endo-116-1-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grover VS, Sharma A, Singh M. Role of nitric oxide in diabetes-induced attenuation of antinociceptive effect of morphine in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000;399:161–164. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guigliano D, Quatraro A, Consoli G, Ceriello A, Torella R, D'Onofrio F. Inhibitory effect of enkephalin on insulin secretion in healthy subjects and in non insulin-dependent diabetic subjects. Metabolism: Clin. & Exptl. 1987;36:286–289. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(87)90190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hallberg CK, Trocme SD, Ansari NH. Acceleration of corneal wound healing in diabetic rats by the antioxidant trolox. Res. Commun. Mol. Pathol. Pharmacol. 1996;93:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hatchell DL, Magolan JJ, Besson MJ, Goldman AI, Pederson HJ, Schultz KJ. Damage to the epithelial basement membrane in the corneas of diabetic rabbits. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1983;101:469–471. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1983.01040010469029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herse PR. A review of manifestations of diabetes mellitus in the anterior eye and cornea. Amer. J. Optom. Physiol. Opt. 1988;65:224–230. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198803000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hyndiuk RA, Kazarian E, Schultz RO, Seideman SA. Neurotrophic corneal ulcers in diabetes mellitus. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1977;95:2193–2196. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450120099012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Isayama T, McLaughlin PJ, Zagon IS. Endogenous opioids regulate cell proliferation in the retina of developing rat. Brain Res. 1991;544:79–85. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90887-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Isayama T, Zagon IS. Localization of preproenkephalin A mRNA in the neonatal rat retina. Brain Res. Bull. 1991;27:805–808. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(91)90212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeng S, Lee JS, Huang SC. Corneal decompensation after argon laser iradectomy - a delayed complication. Ophthalmic Surg. 1991;22:565–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kabosova A, Kramerov AA, Aoki AM, Murphy G, Zierske JD, Ljubimov AV. Human diabetic corneas preserve wound healing, basement membrane, integrin and MMP-10 differences from normal corneas in organ culture. Exp. Eye Res. 2003;77:211–217. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00111-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaji Y. Prevention of diabetic keratopathy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2005;89:254–255. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.055541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaji Y, Usui T, Oshika T, Matsubara M, Yamashita H, Araie M, Murata T, Ishibashi T, Nagai R, Horiuchi S, Amano S. Advanced glycation end products in diabetic cornea. Invest. Ophthamol.Vis. Sci. 2000;41:362–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kamei J, Kawashima N, Kasuya Y. Paradoxical analgesia produced by naloxone in diabetic mice is attributable to supersensitivity of δ-opioid receptors. Brain Res. 1992;592:101–105. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91663-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaufman HE, Barron BA, McDonald MB, Waltman ST. The Cornea. Livingstone, New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim EM, Grace MK, Welch CC, Billington CJ, Levine AS. STZ-induced diabetes decreases and insulin normalizes POMC mRNA in arcuate nucleus and pituitary in rats. Amer. J. Physiol. 1999;276:R1320–R1326. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.R1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim HS, Shang T, Chen Z, Pflugfelder SC, Li DQ. TGF-β1 stimulates the production of gelatinase (MMP-9), collagenases (MMP-1, -13) and stromelysins (MMP-3, -10, -11) by human corneal epithelial cells. Exp. Eye Res. 2004;79:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, Davis MD, DeMets DL. Glycosylated hemoglobin predicts the incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy. JAMA. 1988;260:2864–2871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klocek MS, Sassani JW, McLaughlin PJ, Zagon IS. Topically applied naltrexone restores corneal reepithelialization in diabetic rats. J. Ocular Pharmacol. Ther. 2007;23:89–102. doi: 10.1089/jop.2006.0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klocek MS, Sassani JW, McLaughlin PJ, Zagon IS. Naltrexone and insulin are independently effective but not additive in accelerating corneal epithelial healing in type 1 diabetic rats. Exp. Eye Res. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.06.010. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kolta MG, Pierzchala K, Houdi AA, Van Loon GR. Effect of diabetes on the levels of two forms of met-enkephalin in plasma and peripheral tissues of the rat. Neuropeptides. 1992;21:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(92)90152-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krampert M, Bloch W, Sasaki T, Bugnon P, Rulicke T, Wolf E, Aumailley M, Parks WC, Werner S. Activities of the matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin-2 (MMP-10) in matrix degradation and keratinocyte organization in wounded skin. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:5242–5254. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ljubimov AV, Alba SA, Burgeson RE, Ninomiay Y, Sado Y, T-T Sun, Nesburn AB, Kenney MC, Maguen E. Extracellular matrix changes in human corneas after radial keratomy. Exp. Eye Res. 1998;67:265–272. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ljubimov AV, Burgeson RE, Butkowski RJ, Couchman JR, Zardi L, Ninomiya Y, Sado Y, Huang ZS, Nesburn AB, Kenney MC. Basement membrane abnormalities in human eyes with diabetic retinopathy. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1996;44:1469–1479. doi: 10.1177/44.12.8985139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ljubimov AV, Z Huang, Huang GH, Burgeson RE, Gullberg D, Miner JH, Ninomiya Y, Sado Y, Kenney MC. Human corneal epithelial basement membrane and integrin alterations in diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1998;46:1033–1041. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lu WN, Ebihara N, Miyazaki K, Murakami A. Reduced expression of laminin-5 in corneal epithelial cells under high glucose condition. Cornea. 2006;25:61–67. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000179932.21104.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maguen E, Rabinowitz YS, Regev L, Saghizadeh M, Sasaki T, Ljubimov AV. Alterations of extracellular matrix components and proteinases in human corneal buttons with INTACS for post-laser in situ keratomileusis keratectasia and keratoconus. Cornea. 2008;27:565–573. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318165b1cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McDermott AM, Xiao TL, Kern TS, Murphy CJ. Non-enzymatic glycation in corneas from normal and diabetic donors and its effects on epithelial cell attachment in vitro. Optometry. 2003;74:443–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McLaughlin PJ, Levin RJ, Zagon IS. Regulation of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma growth in tissue culture by opioid growth factor. Int. J. Oncol. 1999;14:991–998. doi: 10.3892/ijo.14.5.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McLaughlin PJ, Zagon IS. Progression of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is associated with down-regulation of the opioid growth factor receptor (OGFr) Int. J. Oncol. 2006;28:1577–1583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nakamura M, Sato N, Chikama T, Hasegawa Y, Nishida T. Fibronectin facilitates corneal epithelial wound healing in diabetic rats. Exp. Eye Res. 1997;64:355–359. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Negri M, Tonnarini G, D'Alessandro M, Fallucca F. Plasma met-enkephalin in type 1 diabetes. Metabolism. 1992;41:460–461. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(92)90200-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Niffenegger JH, Gong D, Cavallerano J, Aiello LM. In: Diabetes mellitus, in Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology. Albert DM, Jakobiec FA, editors. Vol. 5. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1994. pp. 2925–2936. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Parrish CM. The cornea in diabetes mellitus, in Ocular problems in diabetes mellitus. Boston: S.S. Feman, Blackwell Scientific; 1992. pp. 179–205. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Perry HD, Foulks GN, Thoft RA, Tolentino FI. Corneal complications after closed vitrectomy through the pars plana. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1978;96:1401–1403. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910060155011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pieper GM, Mizoguchi H, Ohsawa M, Kamei J, Nagase H, Tseng LF. Decreased opioid-induced antinociception but unaltered G-protein activation in the genetic-diabetic NOD mouse. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000;401:375–379. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00459-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rao GN, Siva Reddy Oration P. Diabetic keratopathy. Ind. J.Ophthalmol. 1987;35:16–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rechardt O, Elomaa O, Vaalamo M, Pääkkönen K, Jahkola T, Höök-Nikanne J, Hembry RM, Häkkinen L, Kere J, Saarialho-Kere U. Stromelysin-2 is upregulated during normal wound repair and is induced by cytokines. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2000;115:778–787. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Robertson SA, Andrew SE. Presence of opioid growth factor and its receptor in the normal dog, cat and horse cornea. Vet. Ophthalmol. 2003;6:131–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-5224.2003.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rogell GD. Corneal hypesthesia and retinoapthy in diabetes mellitus. Amer. Acad. Ophthalmol. 1980;87:229–233. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(80)35257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rosenburg ME, Tervo TMT, Immonen IJ, Muller LJ, Gronhagen-Riska C, Vesaluoma JH. Corneal structure and sensitivity in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Invest. Ophthalmol. 2000;41:2915–2921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Saghizadeh M, Brown DJ, Castellon R, Chwa M, Huang GH, Ljubimova JY, Rosenberg S, Spirin KS, Stolitenko RB, Adachi W, Kinoshita S, Murphy G, Windsor LJ, Kenney MC, Ljubimov AV. Overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase-10 and matrix metalloproteinase-3 in human diabetic corneas: a possible mechanism of basement membrane and integrin alterations. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;158:723–734. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64015-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Saghizadeh M, Chwa M, Aoki A, Lin B, Pirouzmanesh A, Brown DJ, Ljubimov AV, Kenney MC. Altered expression of growth factors and cytokines in keratoconus, bullous keratopathy and diabetic human corneas. Exp. Eye Res. 2001;73:179–189. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Saghizadeh M, Kramerov AA, Tajbakhsh J, Aoki AM, Wang C, Chai N-N, Ljubimova JY, Sasaki T, Sosne G, Carlson MRJ, Nelson SF, Ljubimov AV. Proteinase and growth factor alterations revealed by gene microarray analysis of human diabetic corneas. Invest. Ophthamol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46:3604–3615. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Saini JS, Khandalavia B. Corneal epithelial fragility in diabetes mellitus. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 1983;30:142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sanchez-Thorin JC. The cornea in diabetes mellitus. Internat. Ophthalmol. Clinics. 1998;38:19–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sassani JW, Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ. Opioid growth factor modulation of corneal epithelium: uppers and downers. Current Eye Res. 2003;26:249–262. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.26.4.249.15427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sato E, Mori F, Igarashi S, Abiko T, Takeda M, Ishiko S, Yoshida A. Corneal advanced glycation end products increase in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:479–482. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schultz RO, Peters MA, Sobocinski K. Diabetic keratopathy as a manifestation of peripheral neuropathy. Amer. J. Ophthalmol. 1983;96:368–371. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77829-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schultz RO, Van Horn DL, Peters MA, Klewin KM, Schutten WH. Diabetic keratopathy. Trans. Amer. Ophthalmol. Soc. 1981;79:180–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schwartz AL, Martin NF, Weber PA. Corneal decompensation after argon laser iridectomy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1988 or 1974;106:1572–1574. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060140740047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Severson K, Tackett RL. Enhanced hemodynamic response to [D-Ala2,D-Met5]-methionine enkephalin (DAME) in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats is reversed by insulin replacement. Life Sci. 1998;62:2219–2229. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Slaughter MM, Mattler JA, Gottlieb DI. Opiate binding sites in the chick, rabbit and goldfish retina. Brain Res. 1985;339:39–47. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90619-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Snip RC, Thoft RA, Tolentino FI. Similar epithelial healing rates of the corneas of diabetic and nondiabetic patients. Amer. J. Ophthalmol. 1980;90:463–468. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stolwijk TR, Van Best JA, Boor JP, Lemkes HH, Oosterhuis JA. Corneal epithelial barrier function after oxybupropane provocation in diabetics. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1990;31:436–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Suzuki K, Saito J, Yanai R, Yamada N, Chikama T, Seki K, Nishida T. Cell-matrix and cell-cell interactions during corneal epithelial wound healing. Prog. Ret. Eye Res. 2003;22:113–133. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(02)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tabatabay CA, Bumbacher M, Baumgartmer B, Leuenberger PM. Reduced number of hemidesmosomes in the corneal epithelium of diabetics with proliferative retinopathy. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1988;226:389–392. doi: 10.1007/BF02172973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Takahashi H, Akiba K, Noguchi T, Ohmura T, Takahashi R, Ezure Y, Ohara K, Zieske JD. Matrix Metalloproteinase activity is enhanced during corneal wound repair in high glucose condition. Curr. Eye Res. 2000;21:608–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tervo T, Tervo K, Eranko L. Ocular neuropeptides. Med. Biol. 1982;60:53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Timmers K, Coleman DL, Voyles NR, Powell AM, Rokaeus A, Recant L. Neuropeptide content in pancreas and pituitary of obese and diabetes mutant mice: Strain and sex difference. Metabolism. 1990;39:378–383. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(90)90252-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Timmers K, Voyles NR, Zalenski C, Wilkins S, Recant L. Altered β-endorphin, met-and leu-enkephalins, and enkephalin-containing peptides in pancreas and pituitary of genetically obese diabetic (db/db) mice during development of diabetic syndrome. Diabetes. 1986;35:1143–1151. doi: 10.2337/diab.35.10.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Vermes I, Steinmetz E, Schoorl J, van der Veen EA, Tilders FJ. Increased plasma levels of immunoreactive beta-endorphin and corticotrophin in non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Lancet. 1985;2:725–726. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92964-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wakuta M, Morishige N, Chikama T, Seki K, Nagano T, Nishida T. Delayed wound closure and phenotypic changes in corneal epithelium of the spontaneously diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rat. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007;48:590–596. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang PY. Control of hyperglycaemia in diabetic rabbits by a combination of implants. J. Biomed. Eng. 1993;13:106–112. doi: 10.1016/0141-5425(93)90038-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wanke T, Auinger M, Formanek D, Merkle M, Lahrmann H, Ogris E, Zwich H, Irsigler K. Defective endogenous opioid response to exercise in type 1 diabetic patients. Metabolism: Clin. & Exp. 1996;45:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(96)90043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Watanabe H, Katakami C, Miyata S, Negi A. Corneal disorders in KKAy mouse: a type 2 diabetes model. Jap. J. Ophthamol. 2002;46:130–139. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(01)00487-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Watt CB, Su YY, Lam DM. Opioid pathways in an avian retina. II. Synaptic organization of enkephalin-immunoreactive amacrine cells. J. Neurosci. 1985;5:857–865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-04-00857.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Xu K-P, Li Y, Ljubimov AV, Yu F-SX. High glucose suppresses epidermal growth factor receptor/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway and attenuates corneal epithelial wound healing. Diabetes. 2009;58:1077–1085. doi: 10.2337/db08-0997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yue DK, Hanwell MA, Satchell PM, Turtle JR. The effect of aldose reductase inhibition in motor nerve conduction velocity in diabetic rats. Diabetes. 1982;31:789–794. doi: 10.2337/diab.31.9.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zagon IS, Jenkins JB, Lang CM, Sassani JW, Wylie JD, Ruth TB, Fry JL, McLaughlin PJ. Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, facilitates re-epithelialization of the cornea in diabetic rat. Diabetes. 2002;51:3055–3062. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zagon IS, Isayama T, McLaughlin PJ. Preproenkephalin mRNA expression in the developing and adult rat brain. Mol. Brain Res. 1984;21:85–98. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zagon IS, Klocek MS, Sassani JW, Mauger DT, McLaughlin PJ. Corneal safety of topically applied naltrexone. J. Ocular Pharmacol. Therap. 2006;22:377–387. doi: 10.1089/jop.2006.22.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zagon IS, Klocek MS, Sassani JW, McLaughlin PJ. Use of topical insulin to normalize corneal epithelial healing in diabetes mellitus. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:1082–1088. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.8.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ. Opioid growth factor receptor is unaltered with the progression of human pancreatic and colon cancers. Int. J. Oncol. 2006;29:489–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ. Opioids and the apoptotic pathway in human cancer cells. Neuropeptides. 2003;37:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(03)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zagon IS, S I, McLaughlin PJ. Opioids and differentiation in human cancer cells. Neuropeptides. 2005;39:495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zagon IS, Rahn KA, McLaughlin PJ. Opioids and migration chemotaxis, invasion, and adhesion of human cancer cells. Neuropeptides. 2007;41:441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zagon IS, Ruth TB, Leure-duPree AE, Sassani JW, McLaughlin PJ. Immunoelectron microscopic localization of the opioid growth factor receptor (OGFr) and OGF in the cornea. Brain Res. 2003;967:37–47. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, Allison G, McLaughlin PJ. Conserved expression of the opioid growth factor, [Met5]-enkephalin, and the zeta (ζ) opioid receptor in vertebrate cornea. Brain Res. 1995;671:105–111. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, Kane ER, McLaughlin PJ. Homeostasis of ocular surface epithelium in the rat is regulated by opioid growth factor. Brain Res. 1997;759:92–102. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00238-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, Malefyt KJ, McLaughlin PJ. Regulation of corneal repair by particle-mediated gene transfer of opioid growth factor receptor complementary DNA. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1620–1624. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.11.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, McLaughlin PJ. Opioid growth factor modulates corneal epithelial growth in tissue culture. Amer. J. Physiol. 1995;268:R942–R950. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.4.R942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, McLaughlin PJ. Re-epithelialization of the rabbit cornea is regulated by opioid growth factor. Brain Res. 1998;803:61–68. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00610-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, McLaughlin PJ. Re-epithelialization of the rat cornea is accelerated by blockade of opioid receptors. Brain Res. 1998;798:254–260. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00427-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, McLaughlin PJ. Cellular dynamics of corneal wound re-epithelialization in the rat. I. Fate of ocular surface epithelial cells synthesizing DNA prior to wounding. Brain Res. 1999;822:149–162. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, McLaughlin PJ. Cellular dynamics of corneal wound re-epithelialization in the rat. II. DNA synthesis in the ocular surface epithelium following wounding. Brain Res. 1999;839:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01722-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, McLaughlin PJ. Reepithelialization of the human cornea is regulated by endogenous opioid. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, McLaughlin PJ. Insulin treatment ameliorates impaired corneal re-epithelialization in diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2006;55:1141–1147. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, McLaughlin PJ. Adaptation of homeostatic ocular surface epithelium to chronic treatment with the opioid antagonist naltrexone. Cornea. 2006;25:821–829. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000224646.66472.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, Myers RL, McLaughlin PJ. Naltrexone accelerates healing without compromise of adhesion complexes in normal and diabetic corneal epithelium. Brain Res. Bull. 2007;72:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, Ruth TB, McLaughlin PJ. Cellular dynamics of corneal wound re-epithelialization in the rat. III. Mitotic activity. Brain Res. 2000;882:169–179. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02864-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, Wu Y, McLaughlin PJ. The autocrine derivation of the opioid growth factor, [Met5]-enkephalin, in ocular surface epithelium. Brain Res. 1998;792:72–78. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, Verderame MF, McLaughlin PJ. Particle-mediated gene transfer of OGFr cDNA regulates cell proliferation of the corneal epithelium. Cornea. 2005;24:614–619. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000153561.89902.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Zagon IS, Verderame MF, McLaughlin PJ. 2002. The biology of the opioid growth factor receptor (OGFr) Brain Res. Rev. 2002;38:351–376. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]