Abstract

Since relevant biochemical changes are known to begin at the choriodecidual interface some weeks before actual clinical onset of labor, we hypothesized that the preterm choriodecidua may display gene and protein expression patterns specific to preterm labor. Transcriptomic (microarray) and proteomic (two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2DGE)) profiling methodologies were utilized to compare changes in choriodecidual tissue collected from women who delivered before 35 weeks of gestation following spontaneous preterm labor (n=12) and gestation-matched non-laboring controls (n=7). Additionally, 2DGE was used to compare differences in protein expression during term and preterm labor and to construct a choriodecidual proteome map. Overall, expressed transcripts and proteins indicated active tissue remodelling independent of labor status and an association with inflammatory processes during labor. Spontaneous, infection-induced and abruption-associated preterm deliveries were each defined by distinct transcriptional profiles. Proteins osteoglycin and PGRMC2 were upregulated during term and preterm labor while galectin 1, annexin 3, annexin 5 and PDI were upregulated only during preterm labor suggesting a probable association with the underlying pathology. Together, these results represent novel data that warrant further investigations to elucidate plausible causal relationships of these molecules with spontaneous preterm delivery.

Keywords: Choriodecidua, preterm labor, proteomics, microarray

With an estimated fourteen million babies worldwide born preterm every year, the medical and financial implications of preterm delivery continue to have a significant global societal impact. However, treatment and/or management options are hampered by the inefficacy of predictive markers as well as an incomplete understanding of the pathophysiologies underlying the condition. The causes of spontaneous preterm delivery are multifactorial and several pathogenic pathways are believed to be associated with activation of preterm labor [1]. One of the key gestational sites where pathogenic triggers can evoke a maternal response is at the choriodecidual interface. Extensive extracellular matrix remodelling takes place in this region well before the clinical onset of labor, contributing greatly to the gradual weakening of the maternal-fetal attachment [2]. This has been evidenced by the detection of several proteins of choriodecidual origin in the cervicovaginal fluid weeks before labor [3]. Given that the choriodecidua contains a complex mixture of infiltrating cells (decidual leucocytes and endothelial cells) and resident cells (trophoblasts, fibroblasts, myofibroblasts and macrophages) anchored to extracellular matrix proteins and proteoglycans [2], it is a potential source of several biological factors closely linked to the processes of remodelling and labor. There is a strong possibility that when labor is triggered early, gestational and/or labor-related differences may result in the tissue displaying a pattern of gene and protein expression specific to preterm labor. An evaluation of their expression in the choriodecidua could, therefore, lead to improved understanding of the molecular biology of preterm pregnancies.

In this study, we have applied contemporary profiling methodologies to identify differential expression at the protein and transcript level during preterm labor. Genome-wide transcriptome profiling of choriodecidual tissue was utilized to examine pathways activated during preterm labor as well as to detect changes that can differentiate subclasses of preterm labor. Global analysis of transcriptional changes that eliminates the bias introduced by targeted assays was recently exploited by Haddad and colleagues to investigate the mechanism of spontaneous term labor in the absence of histological chorioamnionitis [4]. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study profiling the preterm choriodecidua. In addition, to identify potential protein markers and to facilitate a comparison of the choriodecidual transcriptome and proteome during preterm labor, proteomic profiling was carried out on the same tissues using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2DGE). Our results demonstrate an inflammatory response with significant upregulation of diverse signalling pathways during preterm delivery. Overall, there was little linearity between the transcripts and the proteins that displayed differential expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample Population and Tissue Collection

Choriodecidual tissue samples were collected with the mother’s informed consent and approval from the research and ethics committees (Project No 05/16) of the Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia. All participants were carrying singleton pregnancies. Spontaneous preterm labor was diagnosed as palpable, painful, regular uterine contractions and a cervical dilatation of ≥2cm or full effacement resulting in preterm delivery prior to 35 completed weeks of gestation (preterm in-labor or PTIL group, n=12). The gestational age-matched control group comprised women who underwent a Caesarean section in the absence of labor prior to 35 completed weeks of gestation (preterm not-in-labor or PTNIL group, n=7). Tissue samples were also collected from women who delivered spontaneously at term/after 37 completed weeks of gestation (term in-labor or TIL samples, n=11) and from women who had an elective Caesarean section at term in the absence of labor (term not-in-labor or TNIL samples, n=13). Gestational age was determined by ultrasound measurements.

Placentas with attached fetal membranes were collected under aseptic conditions were transported to the laboratory within 10min of delivery. The chorion with adherent decidua (5cm × 5cm) was manually separated from the amnion, rinsed briefly in normal saline, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analyzed. Relative consistency was maintained during collection by selecting a region away from the site of membrane rupture as well as the placental bed. Based on clinical and histological evidence, it was possible to divide the PTIL tissue samples into three subgroups: those collected from women who had either a lower genital microbial infection and/or histological chorioamnionitis (infection PTIL subgroup, n=6), those obtained from women who had a placental abruption but no infection (abruption PTIL subgroup, n=2) and those that displayed no signs of infection or abruption (pure PTIL subgroup, n=4). Clinical signs of infection were defined as maternal tachycardia, maternal pyrexia, abdominal pain and tenderness and/or change in the color of amniotic fluid (clear to green/brown) or a fetal tachycardia. Samples from two women only had a vaginal infection (with GBS and Mycoplasma species respectively) and no documented histological infection but were included in the infection subgroup since ascending microbial infection may also elicit an inflammatory response at the choriodecidual interface. Although abruption was an exclusion criterion, histological examination of the placenta subsequent to tissue collection revealed five women (two preterm not-in-labor and three preterm labor samples) to have had evidence of subclinical abruption, and it was decided to retain these two samples as a distinct subset. The possibility of potential confounding by these pathologies (placenta previa, placental abruption and microbial infection in the absence of histological chorioamnionitis) was addressed by assessing differential expression with and without these samples. The PTNIL samples were from women who had opted for a Caesarean section for reasons other than obstetric complications, namely brain tumour, intractable pain related to spinal fusion, and poor past obstetric history (n=4), as well as those who presented with placenta previa (n=2), who had a placental abruption (n=2) and who had a growth restricted infant (n=1). To address the variation in the PTNIL cohort, comparative analyses were also carried out using only samples with no obstetric complications (n=4) and excluding those with placenta previa, placental abruption and fetal growth restriction. Clinical characteristics of the women from whom preterm choriodecidual samples utilized in this study were collected are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the women from whom the preterm choriodecidua samples were collected.

| Group | # | GA | Mode of Delivery | Reason For Delivery | Subgroup | Previous History of PTD | Placental Histology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTNIL | 1 | 34w | CSNIL | Spinal Fusion | Pure | 1 elective PTD for spinal fusion | Not done |

| 2 | 34 w | CSNIL | Previous History | Pure | 6 miscarriages with IVF | Not done | |

| 3 | 32 w | CSNIL | Brain Tumour | Pure | - | Recent intervillous thrombus formation | |

| 4 | 34 w | CSNIL | Placenta Previa | Placenta Previa | - | Not done | |

| 5 | 34 w | CSNIL | Placenta Previa | Placenta Previa | 2 terminations | Focal chronic deciduitis | |

| 6 | 33 w | CSNIL | Placental Abruption, Suspected Fetal Compromise | Abruption | - | Recent infarcts & evidence of old abruption | |

| 7 | 34w | CSNIL | FGR | FGR | 2 miscarriages | Not done | |

| PTNIL | 8 | 30 w | NVD | Spontaneous | Pure | - | No abnormalities |

| 9 | 34 w | NVD | Spontaneous | Pure | - | Immature placenta | |

| 10 | 27 w | NVD | Spontaneous | Pure | - | Not done | |

| 11 | 31 w | NVD | Spontaneous | Pure | - | Not done | |

| 12 | 31 w | NVD | Spontaneous | Infection | 1 miscarriage | Mild focal acute chorioamnionitis | |

| 13 | 30 w | CSIL | Breech | Infection | 1 at 32 w | Moderate acute chorioamnionitis | |

| 14 | 32w | CSIL | Breech | Infection | - | Probable early chorioamnionitis | |

| 15 | 28w | CSIL | Breech | Infection | 1 spontaneous abortion | Early chorionitis and acute deciduitis | |

| 16 | 32w | NVD | Spontaneous | Infection | - | No villitis or chorioamnionitis | |

| 17 | 35 w | CSIL | On patient’s request during labor | Infection | 2 at <27 w | Not done | |

| 18 | 29 w | NVD | Spontaneous | Abruption | - | No infection, hemorrhage on maternal surface | |

| 19 | 33 w | CSIL | Breech | Abruption | - | No infection, reflects varying degree of ischaemic damage, diffiult to interpret at this gestation | |

Abbreviations: PTNIL = Preterm not-in-labor, # = Sample number, GA = Gestational Age at delivery, PTD = Preterm Delivery, CSNIL = Caesarean Section not-in-labor, CSIL = Caesarean Section in-labor, NVD = Normal Vaginal Delivery, w = weeks, FGR = Fetal Growth Restriction, PTIL = Preterm in-labor

RNA Extraction & Hybridization

Five hundred nanograms of total RNA was extracted from each of the preterm choriodecidual tissue samples using the QIAGEN RNeasy® Midi Kit (Qiagen) and amplified using the Illumina®TotalPrep RNA Amplification Kit (Ambion). Hybridization of the biotin labelled antisense RNA to Illumina® Sentrix® Human Whole Genome (WG-6) Series 2 BeadChips (Illumina Inc) and subsequent washing, blocking and detecting were performed using Illumina’s BeadChip 6×2 protocol. Signal detection was developed with the addition of streptavidin-Cy3 conjugate (Roche, Germany) and subsequent wash steps. All samples were processed in parallel to reduce variation. The BeadChips were scanned on the Illumina® BeadArray™ 500GX Reader using Illumina® BeadScan image data acquisition software version 3.5.11.29034 (Illumina Inc).

Data Analysis

The Gene Expression module of the Illumina® BeadStudio software version 2.3.41.16318 (Illumina Inc) was utilized to analyse the arrays. The degree of similarity between the expressed genes was identified using hierarchical clustering analysis. The overall changes in gene expression in the PTIL group and its three subgroups were evaluated by comparison to the PTNIL group. Differential expression was assessed using ‘Illumina Custom’ error model algorithm with PTNIL as the reference group and PTIL or PTIL subgroups as the condition group. Background subtraction was carried out using the average value of non-specific signals generated by the negative controls on the chip. A detection p value of <0.01 (99% confidence interval) was used to ensure that the average signal intensities of the target probes were discernible from the negative controls. The average signal intensities generated were log transformed for statistical analyses and array results normalized with the rank-invariant method using a subset of genes from the reference group. The statistical confidence that expression of a gene in the labor group had changed with respect to the non-labor group was assessed with a differential score (the log transformed p-value derived from the differential expression algorithm, Illumina custom error model). For a p value of 0.01, the differential score equates to 20 resulting in 99% confidence that a gene expression has changed with respect to the reference group. The biological functions and signalling pathways most significantly associated with differentially expressed transcripts were generated using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (www.ingenuity.com). Array datasets were mapped to the corresponding gene entities in Ingenuity Pathways Analysis Base (IPAB) using GenBank IDs.

Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis

Approximately 100–200mg of frozen preterm and term choriodecidual tissues were homogenized (Jeneke and Kunkel GMBH and Co) on ice in a lysis buffer (5M urea, 2M thiourea, 2mM TBP, 2% CHAPS, 2% SB 3–10, 65mM DTT, 0.2% BioLyte 3/10, 40mM Tris and 0.002% bromophenol blue) containing nuclease inhibitors (Amersham Biosciences) and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Homogenates were then centrifuged and the supernatants desalted using Zeba™ desalting spin columns (Pierce). Total protein was quantified using a modified Bradford assay [5], and 11cm, pH 3–10 non-linear IPG strips (BioRad) passively rehydrated overnight in duplicate with 150μg of protein. Strips were focused using the PROTEAN IEF cell (BioRad) at 100V for 4 hours, 300V for 4 hours, 600V for 2 hours, 1000V for 1hour, 2000V for 1hour and then held at 3500V to a total of 35000VH. Subsequently, a two-step equilibration was carried out, first with 1% DTT and then with 1.25% IAA in a buffer containing 6M urea, 50mM Tris/HCl pH 8.8, 30% (v/v) glycerol, 2% (w/v) SDS and a trace of bromophenol blue. SDS PAGE was carried out on 4–20% precast gels (BioRad) and at a constant current of 15 mA for 1 hour followed by 30 mA for the remainder of the run. Gels were stained with Deep Purple Total Protein stain (Amersham Biosciences), quantitative analysis performed with PDQuest version 7.1.0 (BioRad) and gels post-stained with Coomassie Blue (BioRad). Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r2) and coefficient of variation (CV) values generated by the software were used as measures of variation. Gel-to-gel variation was assessed by running triplicate gels from three different samples and the reproducibility of the technique assessed by comparing variation among the duplicate gels. The signalling pathways most significantly associated with the differentially expressed proteins were generated using IPA.

Mass Spectrometry

Protein spots were manually excised from Coomassie stained gels and washed for 15 min with each of the following in succession: 300μl MilliQ, 300μl 100% acetonitrile and 300μl 100mM ammonium hydrogen carbonate (AHC). Plugs were then destained with 300μl 100mM AHC/acetonitrile (50:50 v/v) and then dehydrated with 100μl acetonitrile before being freeze-dried. Following addition of 12.5 μg/mL of modified trypsin (Sigma) in 200mM AHC to the plugs, digestion was allowed to proceed overnight at 30°C. Tryptic peptides were separated on a Agilent HPLC-Chip using a linear 20 min gradient of 5 to 50% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid, and then analysed on an ion trap mass spectrometer (Agilent 1100 ion trap XCT plus). The MS/MS peak lists were searched against the SwissProt human database using MASCOT version 2.2 (Matrix Science, UK) with peptide mass tolerance of ± 2Da, fragment mass tolerance of ± 0.8Da, allowing up to four missed cleavages and using cysteine carbamidomethylation and methionine oxidation as fixed and variable modifications respectively. Statistically significant (p<0.05) identification included a MOWSE score cut off >37, at least two matched peptide masses and a sequence coverage ≥10%.

RESULTS

Transcriptional Profile of Choriodecidua during Preterm Labor

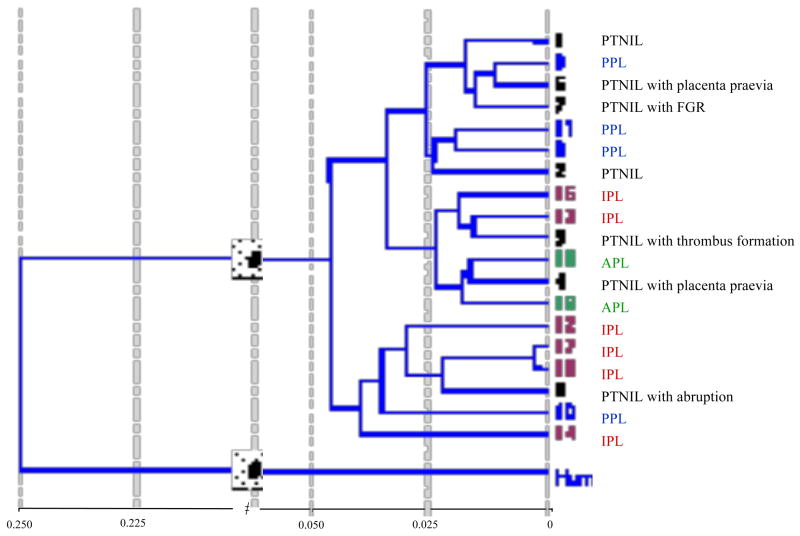

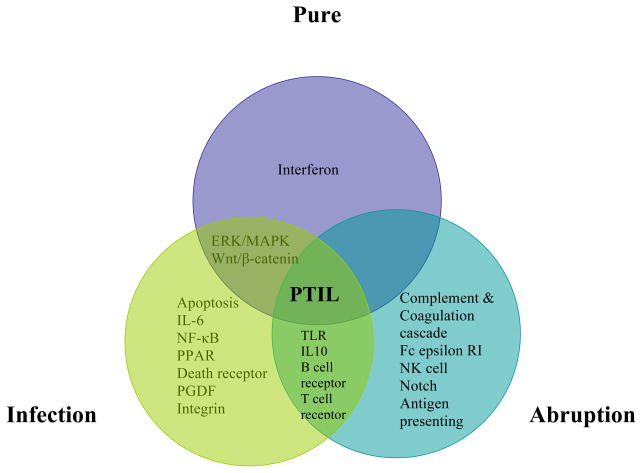

Although clustering analysis revealed considerable heterogeneity among the sample groups (Figure 1), data was analyzed with the predefined groups/subgroups to reflect the clinical setting. An overall comparison between the main groups showed that a total of 100 transcripts were upregulated in the PTIL group inclusive of all subgroups (n=12) compared to the PTNIL group (n=7). However, a comparison of the PTNIL group to the pure, infection and abruption subgroups revealed changes in 181, 765 and 647 transcripts respectively. About 15% of all transcripts were expressed sequence tags or hypothetical proteins that could not be annotated. About 21% of the infection PTIL, 17% of the pure PTIL and 12% of the abruption PTIL transcripts remained unmapped. Exclusion of the PTNIL samples with obstetric complications from the analyses resulted in changes in the number of transcripts noted to be upregulated in each subgroup (223, 1171 and 601 transcripts in pure, infection and abruption subgroups) but did not appear to have a major effect on the overall profile. A vast majority of the array genes displayed no change in expression between the groups compared. Data from all groups appeared to be highly and tightly correlated with little or no deviation from the line of best fit and thus with little or no bias in filtered genes when assessing the fold change. Filtering on the basis of expression value ensured that the observed signal was significantly greater than the background noise and therefore a true signal. Major signalling pathways associated with the annotated genes in all categories are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Cluster analysis of preterm samples.

Clustering based on overall gene expression highlighted the heterogeneous nature of the samples that were grouped according to clinical and histological data. In general, the PTNIL control group displayed the greatest heterogeneity. The pure (PPL), infection (IPL) and abruption (APL) subgroups were relatively more homogeneous. While it seemed that the PTNIL samples with placenta praevia (3&4) and abruption (6) might correlate better to the APL samples, sample 5 correlated better with PPL and sample 6 with IPL samples. Four of the IPL samples clustered together. Samples 16 and 17, collected from women with a vaginal infection but no evidence of histological chorioamnionitis displayed the closest similarity.

Abbreviations: PTNIL = Preterm not-in-labor, PPL = Pure Preterm in-labor, IPL = Infection Preterm in-labor, APL = Abruption Preterm in-labor

Figure 2. Venn diagram depicting significant canonical signalling pathways associated with the mapped transcripts from the laboring preterm subgroups.

PTIL = Preterm in-labor group

Differentially Expressed Transcripts

An overview of the transcripts differentially expressed during preterm labor indicated there was an overall increase in the expression of inflammatory mediators and targets such as TNF-α, IL-6, suppressor of cytokine signalling 3 (SOCS3), leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF), chemokine C-C motif ligands (CCL3, CCL3L3, CCL4, CCL4L1), and chemokine C-X-C motif ligands (CXCL1, CXCL2). Considerable differences were observed between the pure and infection PTIL subgroups. As anticipated, expression of TNF-α, IL-6, SOCS3 and TLR1 was significantly higher in the infection subgroup. NF-κB expression was exclusive to this subgroup and consequently, most of the signalling pathways associated with infection PTIL were those that involved NF-κB mediation. The magnitude of these changes was enhanced when the PTNIL samples with obstetric complications were excluded from the comparison. Other transcripts unique to the infection subgroup were heat shock proteins, platelet derived growth factors, various collagens, ICAM1, annexin 3, TGF-β receptor, caspase 6 and SOD2. In comparison, the pure subgroup was characterized by significant expression of activin and interferon receptors and absence of caspases and cell adhesion molecules. Although transcripts of inflammatory mediators (including IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, SOCS3, MMP1, MMP7 and TLR2) demonstrated >2-fold increases in the pure subgroup compared to the control group, they did not reach the level of statistical significance. However, exclusion of PTNIL samples with obstetric complications from the comparison resulted in significant upregulation of IL6 and no difference in levels of the interferon receptors. The abruption subgroup displayed few similarities with the other subgroups with gene expression centring on an array of TLRs along with members of the coagulation and complement cascade. Anti-apoptotic IL-7 was the predominant interleukin in this subgroup with TNF-α, IL-6, SOCS3 and NF-κB being noticeably absent. However, as in the infection subgroup, BMP2 and calgranulin B were significantly expressed. A simplified table highlighting some of the transcripts expressed in each PTIL subgroup is presented in Table 2. The complete list of mapped transcripts is provided as supplementary data (Supplementary Tables 1–4).

Table 2. A condensed list of some of the differentially expressed transcripts in the PTIL subgroups.

GenBank ID has been used to identify transcripts and is listed along with their differential scores (DS). For some categories, transcripts that were upregulated in the absence of statistical significance have been listed (in blue) for the purpose of comparison.

| Category | PPL | DS | IPL | DS | APL | DS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokines | SOCS3 | 17 | IL-6 | 49 | IL-7 | 15 |

| PBEF1 | 13 | SOCS3 | 45 | Il-10 | 10 | |

| TNF-α | 11 | TNF-α | 36 | |||

| IL-6 | 10 | SOCS1 | 20 | |||

| PBEF1 | 20 | |||||

| IL-8 | 17 | |||||

| Cytokine Receptors | TNFAIP3 | 32 | TNFAIP3 | 46 | IL7R | 49 |

| IL6ST | 27 | IL4R | 38 | TNFSF13 | 39 | |

| IL2RB | 21 | IL18RAP | 28 | IL2RA | 30 | |

| IL1RAP | 24 | IL10RA | 25 | |||

| TRAF5 | 25 | |||||

| TNFSF19 | 22 | |||||

| Chemokines | CXCR4 | 29 | CXCL1 | 32 | CXCL2 | 47 |

| CCL3 | 24 | CXCL2 | 28 | CXCR3 | 23 | |

| CXCL14 | 24 | CCL3 | 26 | |||

| CCL4L1 | 23 | CCL5 | 22 | |||

| CCL20 | 20 | |||||

| CCL3L3 | 20 | |||||

| Interferons | IFNAR2 | 24 | IRF6 | 38 | IRF8 | 32 |

| IFNGR2 | 21 | IRF1 | 25 | IFI16 | 22 | |

| IFI44L | 22 | |||||

| Activin A receptors | ACVRL1 | 24 | ACVR1B | 18 | ||

| ACVR1B | 23 | |||||

| Toll-like receptors | TLR2 | 12 | TLR1 | 21 | TLR1 | 60 |

| TLR2 | 34 | TLR5 | 40 | |||

| TLR7 | 39 | |||||

| TLR4 | 30 | |||||

| TLR8 | 25 | |||||

| TLR2 | 22 | |||||

| NF-κB | NFκBIZ | 50 | NFκB2 | 35 | ||

| NFκB1A | 29 | NFκB1 | 31 | |||

| NFκB1E | 57 | |||||

| NFκB1A | 56 | |||||

| Rel | 50 | |||||

| NFκBIZ | 34 | |||||

| RelB | 32 | |||||

| Prostaglandins | PTGS2/COX2 | 13 | PTGER4 | 27 | PTGES | 36 |

| PTGS2/COX2 | 20 | TBXAS1 | 36 | |||

| Phospholipases | PLA2G10 | 46 | IPLA2γ | 23 | PLCG2 | 41 |

| PLA2G2A | 23 | PLCXD1 | 22 | PLA1A | 31 | |

| PLCE1 | 20 | |||||

| Complement | C1QR1 | 47 | ||||

| C5AR1 | 44 | |||||

| C1QC | 40 | |||||

| C1QA | 35 | |||||

| CFH | 29 | |||||

| C1QB | 27 | |||||

| C3AR1 | 23 | |||||

| CFB | 22 | |||||

| Coagulation Factors | F13A1 | 31 | ||||

| VWF | 28 |

Abbreviations: PPL = Pure Preterm in-labor, IPL = Infection Preterm in-labor, APL = Abruption Preterm in-labor, DS = Differential Score

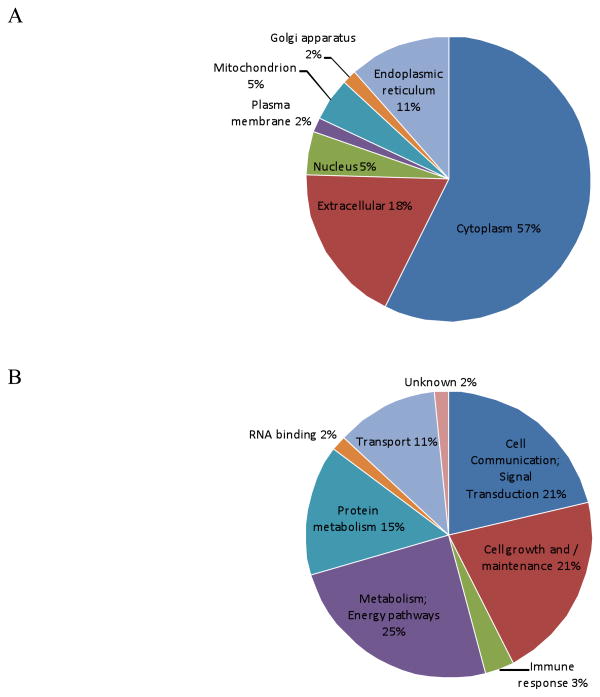

Choriodecidual Proteome

An average of 750 spots was detected on fluorescently stained gels of choriodecidua protein extracts and 450 spots on Coomassie stained gels. Some spots revealed the presence of more than one protein; their statistically significant (p<0.05) probability (Mowse) scores implying migration of multiple proteins to the same coordinates on the gel. Some proteins appeared as spot trains, with the same molecular mass but differing isoelectric points, on the gels suggestive of post-translational modifications or alterations that may have occurred during sample preparation. Of a total of 100 gel spots subjected to MS, unambiguous identities were obtained for 89 spots that corresponded to 61 proteins (Supplementary Table 5 & Supplementary Figure 1). A classification based on their primary location (Figure 3A) revealed predominantly cytosolic proteins (57%) followed by ECM proteins (11%), endoplasmic reticular proteins (7%), nuclear and mitochondrial proteins (3% each) and golgi body and plasma membrane proteins (1% each). Based on their functions, identified proteins could be placed into three main biological categories (Figure 3B): metabolism including protein and energy pathways (40%), cell communication and signal transduction (21%) and cell growth and/or maintenance (21%). Other functions included transport (11%), association with immune response (3%) and RNA binding (2%). When organized into a merged network using IPA, a number of the identified choriodecidual proteins were noted to be associated with TNF-α and IL-6 signaling.

Figure 3. Cellular location & functional categorization of identified proteins.

(A) Cellular Location: The majority of the identified proteins were revealed to be cytosolic and with subcellular proteins limited to about 20%. (B) Functional Classification: Based on the biological process associated with their function, the proteins could be grouped into six main classes. Those associated with protein and energy metabolism predominate while other major classes included cell communication/signal transduction, cell growth/maintenance and transport. The location and molecular function of each protein is listed in Supplementary Table 5.

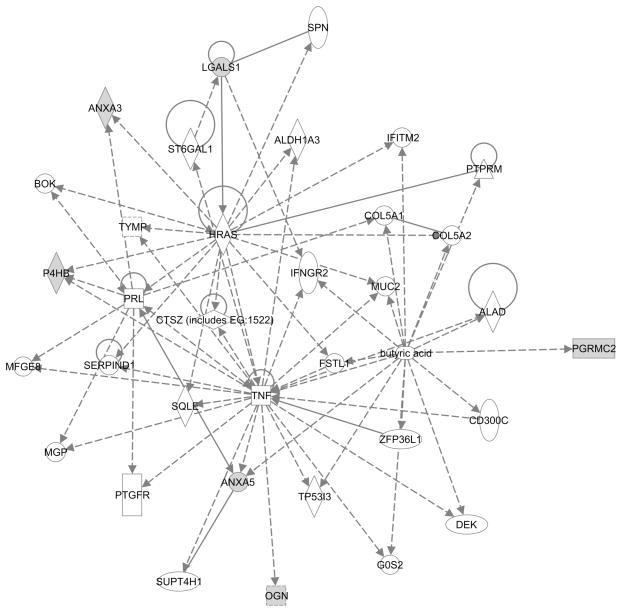

Proteins Differentially Expressed during Preterm Labor

An overall comparison of the preterm labor group, inclusive of all subgroups, to the non-laboring preterm control group resulted in the detection of 19 spots with expression altered in a statistically significant manner during preterm labor. Of these, six were identified by mass spectrometry as membrane-associated progesterone receptor component 2 (PGRMC2), annexin 5, galectin-1, osteoglycin, annexin 3 and protein disulfide isomerase (PDI). IPA analysis of these differentially expressed proteins indicated an indirect association with TNF-α (Figure 4). To compare whether these changes were replicated at term gestation, expression of these proteins was assessed in spontaneous term labour samples relative to their gestation matched not-in-labor controls. For two proteins, the 24kDa PGRMC2 and the 31kDa osteoglycin, significant upregulation in expression was observed during both term and preterm labor. In contrast, upregulation of the proteins, galectin 1, PDI and annexin 5 and annexin 3, was observed only during preterm labor (Table 3A). While most of these proteins displayed significant expression in the pure subgroup (Table 3B), expression changes in the other subgroups displayed larger inter-sample variation and thus remained outside the limits of statistical significance (Table 4B). Sample group variability, which was comparable between the duplicates, was highest in the PTNIL group (CV of 70%) compared to the other groups, subgroups (CV of 50% to 60%). Exclusion of PTNIL samples with obstetric complications did not have a significant impact on the groups’ CV. Gel-to-gel variation (r2) ranged from 0.85 to 0.89.

Figure 4.

Molecular relationships of the differentially expressed proteins indicate an association with TNF-α signaling. In grey are proteins that were significantly overexpressed during preterm labor. Broken lines represent indirect relationships while unbroken lines indicate direct relationships between two proteins.

Table 3.

Table showing p values for the differentially expressed proteins in pairwise comparisons between the laboring and non-laboring control groups. Table (A) displays expression of the proteins during preterm and term labor compared to the gestation-matched not-in-labor controls and Table (B) their expression in the preterm subgroups compared to the preterm not-in-labor control group. Statistical significance (p<0.05) was determined by 2DGE analysis software.

| A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | PTIL vs PTNIL (p value) | TIL vs TNIL (p value) | ||

| Membrane-associated progesterone receptor component 2 (PGRMC2) | 0.01 | 0.05 | ||

| Galectin-1 | 0.01 | |||

| Annexin 5 | 0.03 | |||

| Osteoglycin | 0.01 | 0.03 | ||

| Annexin 3 | 0.01 | |||

| Protein Disulfide Isomerase (PDI) | 0.04 | |||

| B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | PPL vs PTNIL (p value) | IPL vs PTNIL (p value) | APL vs PTNIL (p value) | |

| Membrane-associated progesterone receptor component 2 (PGRMC2) | 0.01 | |||

| Galectin-1 | 0.01 | 0.001 | ||

| Annexin 5 | 0.01 | |||

| Osteoglycin | 0.03 | |||

| Annexin 3 | 0.003 | 0.05 | 0.03 | |

| Protein Disulfide Isomerase (PDI) | 0.03 | |||

Abbreviations: PTIL = Preterm in-labor, PTNIL = Preterm not-in-labor, TIL = Term in-labor, TNIL = Term not-in-labor, PPL = Pure Preterm in-labor, IPL = Infection Preterm in-labor, APL = Abruption Preterm in-labor,

Table 4. Comparison of protein and transcript expression.

Since both profiling techniques utilized different comparison criteria, the fold changes represented below have been calculated using the mean value of the normalized expression intensities. Table (A) shows overall expression during preterm labor inclusive of all subgroups. Table (B) shows expression in each subgroup.

| A | Protein/Gene Name | 2 DE Fold Change | Microarray Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| PGRMC2/PGRMC2 | 1.6* | 1.1 | |

| PDI/PDIA2 | 1.5* | 1.3 | |

| Annexin 3/ANXA3 | 3* | 1.3 | |

| Annexin 5/ANXA5 | 2.6* | 2 | |

| Osteoglycin/OGN | 2.3* | 1.2 | |

| Galectin 1/LGALS1 | 2.4* | 0.9 |

| B | Protein/Gene Name | PPL | IPL | APL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGRMC2/PGRMC2 | Protein | 1.8* | 1.5 | 1.4 | |

| mRNA | 1 | 1 | 1.1 | ||

| PDI/PDIA2 | Protein | 1.6* | 1.3 | 1.7 | |

| mRNA | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.2 | ||

| Annexin 3/ANXA3 | Protein | 2.9* | 2.7* | 3.7* | |

| mRNA | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.3 | ||

| Annexin 5/ANXA5 | Protein | 2.2 | 3* | 2.5 | |

| mRNA | 1.2 | 2.9* | 1 | ||

| Osteoglycin/ | Protein | 2* | 2.3 | 2.8 | |

| mRNA | 0.7 | 0.9 | 2.1 | ||

| Galectin 1/ | Protein | 2.3* | 2 | 3.4* | |

| mRNA | 1 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

Abbreviations: PPL = Pure Preterm-in-labor, IPL = Infection Preterm-in-labor, APL = Abruption Preterm-in-labor.

Statistically significant expression (p<0.05) as determined by 2DGE analysis software.

Comparison of Proteomic and Transcriptomic Data

Since both platforms used different methods of quantification and normalization, comparison of the two datasets could only confirm if the differential expression of the protein was reflected at the level of the transcript. Cross-referencing was carried out using GenBank identities. As expected, relative to the transcriptome, the protein coverage obtained with 2DE was very small with the 750 fluorescently stained gel spots representing 0.002% of the array transcripts. In general, changes in the order of 2- to 10-fold were detected for mRNA expression and differences of 1.5- to 3-fold for protein expression. Because of the methodological biases associated with 2DGE, cytokines and transcription factors (that are usually low abundance and/or basic proteins) that were identified in the transcriptome were difficult to detect on gels. Of the 61 identified proteins, 53 could be aligned to the corresponding mRNA in the array. For those proteins that displayed no labor-associated expression change, the corresponding transcript showed the same trend. Although the correlation between the differentially expressed proteins and the corresponding transcripts was poor (Table 4), no negative trend was noted between an upregulated protein and its transcript. The difference appeared to be due to a smaller fold change of expression, no change or a large intra-group variation for these transcripts relative to protein expression. Both datasets were significantly associated with common molecular and cellular functions such as pathways associated with cell death, glycolysis and oxidative stress, as well as the presence of a low-grade inflammatory response.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to identify expression patterns unique to preterm labor using profiling methodologies and we demonstrate, for the first time, molecular differences between clinical phenotypes of preterm delivery. As demonstrated by previous studies, activation of a localized inflammatory response was obvious in all preterm deliveries but appeared to be effected by different mechanisms in each subgroup. Of the two techniques, transcriptional profiling was more successful than the proteomic analyses in delineating pathways that might be associated with each subclass of preterm labor. While a cytokine-mediated response was detected in spontaneous and infection-induced preterm deliveries, the mechanism of abruption-associated preterm labor was markedly different indicating a complement-mediated response. Furthermore, there was disparity in the degree of inflammation in spontaneous and infection-induced preterm deliveries with a less robust cytokine expression noted in the former compared to the latter. There was no clear indication of apoptosis during preterm delivery in either the proteome or the transcriptome although some evidence of apoptotic activity was detected in the infection subgroup.

Transcriptome reveals diverse signalling pathways

Infection-induced preterm deliveries displayed a heightened inflammatory response that was unmistakably associated with NFκB activation. Consistent with an acute inflammatory response, expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines (IL-6, TNF-α, CCL3 and CCL5) was observed to be upregulated in this subgroup [6]. Although the increase in SOCS3 indicated negative regulation of IL-6 signalling [7], the increase in PBEF1 expression is in concordance with the upregulation of IL-6 [8]. However, SOCS3 can also augment LPS induced production of TNF-α [9] and thus may account for the simultaneous increase in TNF-α expression. The upregulated transcripts also correlated with the presence of infection in this subgroup with no distinct differences noted between samples with histological chorioamnionitis and samples with only a genital tract infection. While increased IL-6 expression during preterm labour in the presence or absence of infection has been previously documented [8, 10], mechanisms associated with spontaneous preterm deliveries were less obvious. The pure subgroup displayed less robust cytokine expression relative to the control group despite the upregulation in cytokine/chemokine receptors implying an association with an inflammatory stimulus. Preterm delivery complicated by placental abruption was characterized by an overactivation of the complement cascade via the classic and the alternate pathways, indicating the triggering of an inflammatory response and thrombosis [11]. Suppression of a pro-inflammatory response was also suggested with IL10 receptor (IL10RA) upregulation in the absence of any pro-inflammatory cytokine expression changes. Furthermore, the observed upregulation of HLA receptors, along with an inappropriate activation of the complement, implied fetal involvement. In all categories, activation of an immune response appeared to be mediated by toll-like receptor (TLR) signalling. TLR1 and TLR2 were present in significant amounts in the infection subgroup while the pure subgroup was associated only with TLR2 upregulation. In concordance with previous studies that have shown co-expression of TLR1 and TLR2 to enhance NFκB activation and TLR1 deficient macrophages to exhibit reduced proinflammatory cytokine production [12], NFκB signalling was predominant in the infection subgroup and a subdued cytokine expression in the pure subgroup. In contrast, the role of TLRs in the abruption subgroup in the absence of a proinflammatory cytokine response appears less clear, but may be linked to decidual thrombin-induced neutrophil infiltration [13] since neutrophils express most of the TLRs [14].

Our study did not identify genes directly associated with apoptosis to be upregulated in the choriodecidua duting preterm labor and maybe partially because fetal membrane apoptosis is predominantly a feature of PPROM rather than preterm delivery with intact membranes [15], as well as due to the choriodecidual region sampled. However, some evidence of increased apoptosis during infection-induced preterm labor was indicated by the upregulation of the phospholipid scrambalase and CD44 transcripts in this subgroup. Phospholipid scrambalase contributes to phospholipid externalization, which is an early feature of apoptosis, and modulates expression of apoptosis-related genes in some cell lines [16]), while CD44 increases the phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils [17]. Consistent with this is the upregulation of annexin 5 protein that is primarily triggered by direct apoptotic activity [18] in this subgroup. A probable regulation of apoptosis was indicated by NF-κB and ERK/MAPK signalling. While TNF-α can mediate apoptosis [19], it can also exert an anti-apoptotic effect via NF-κB, ERK/MAPK and other mediators [20]. NF-κB pathway activation prevents TNF-α mediated apoptosis; however, if inhibited early, it can facilitate apoptosis [21] and this may be the case during spontaneous (pure) preterm delivery where NF-κB inhibitors were upregulated in the absence of NF-κB subunits. Increased expression of activin receptor ACVR1B may also support an apoptotic pathway in the choriodecidua during spontaneous preterm labor [22, 23].

Differences in prostaglandin biosynthesis were also evident among the different subclasses of preterm delivery. In all groups, upregulation of phospholipases A and/or C transcripts indicated mobilization of arachidonic acid from different phospholipids; PLA2G2A and PLA2G10 in the pure subgroup, iPLA2γ and PLCXD1 in the infection subgroup and PLCG2, PLA1A and PLCE1 in the abruption subgroup. However, upregulation of COX2 expression was confined to the infection subgroup suggesting involvement of NFκB. Not surprisingly, the abruption group was clearly different with upregulation of thromboxane A synthase (that catalyzes synthesis of thromboxane A2, a potent vasoconstrictor and inducer of platelet aggregation) as well as peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) that negatively regulate or destabilize COX2 expression [24] [25]. Furthermore, decidual (and myometrial) PGE2 activity was indicated by the upregulation of oxytocin receptor transcript and phospholipase C isoforms.

Proteomic Analyses

As hypothesized, the differentially expressed proteins displayed gestational and labor related differences. Upregulation of osteoglycin and PGRMC2 were suggestive of a generalized labor associated increase since it was noted during both term and preterm labor. In contrast, galectin 1, annexin 3, annexin 5 and PDI were upregulated only during preterm labor implying a possible association with the underlying pathology that precipitated labor. While the increased osteoglycin expression may be linked to labor-associated tissue remodelling [26], increased PGRMC2 and PDI expression, particularly in the pure subgroup, is suggestive of hormonal regulation during spontaneous preterm deliveries. PDI is a molecular chaperone for estrogen receptor-alpha [27], a protein that is upregulated during labor and linked to the functional progesterone withdrawal and estrogen activation at the time of delivery [28]. The increased expression noted in this study is also in agreement with the increased PDI mRNA expression in chorion from preterm deliveries [29]. Little is known about PGRMC2 except that it may have a role in suppressing nodal metastasis [30] and that it exhibits a 50% homology with PGRMC1, the overexpression of which is associated with progesterone’s anti-apoptotic effect in rats [31]. That it was identified by its ectodomain fragments may be of interest given the biomarker potential of choriodecidual proteins detected in the cervicovaginal fluid. A recent study demonstrated the upregulation of annexins 3 and 5 in the cervicovaginal fluid during spontaneous preterm birth prior to 37 weeks’ gestation using the 2D-LC MS/MS technique [32]. Although annexin 3 was noted to be elevated in all subgroups, not much is known about its biological function or its role in human pathologies. Two of the other proteins upregulated during preterm labor are known to exhibit immunomodulatory functions. An increase in annexin 5 expression is primarily triggered by direct apoptotic activity [33] and can then aggravate an inflammatory response in a feedback loop mechanism [34]. Galectin 1, on the other hand, promotes a Th2 immune response by inducing Th1 cell apoptosis [35] [35], suggesting a protective immunomodulation. It is possible that the inclusion of deliveries at >32 weeks of gestation (when myometrial activation in response to uterine stretch or fetal maturity and HPA activation may already have been initiated in preparation for term labor) resulted in proteins exclusive to preterm labor not being detected. This was evident from the identified choriodecidual proteome that showed several common denominators between laboring and non-laboring tissues at term and preterm gestations, suggesting that these proteins may be representative of overall cellular homeostasis during pregnancy and/or labor.

Comments

The overall findings of this investigation are consistent with some of the acknowledged theories regarding the physiology and pathophysiologies of labor. The protein and mRNA concentrations of some of the cytokines, prostaglandins and NFκB genes upregulated in this study have previously been examined in fetal membranes [36–38] from women in preterm labor. Likewise, comparison of results of the present study with microarray data from preterm [39] and term fetal membranes [4] revealed some common mediators as well as a role for some proteins and transcripts previously not described in the context of preterm labor. From the identified pathways it appears that the inflammatory response activated during preterm labor may be the consequence of diverse stimuli. While an exacerbation of the response may be an outcome of gestational tissue infection during infection-induced preterm deliveries, a sustained response may be the driving force in spontaneous preterm deliveries occurring in the absence of an overt infection. In contrast, the resultant pathways during abruption induced preterm delivery indicate combined vascular and inflammatory stresses. Given the effect of sample size and heterogeneity on outcome, it is reasonable to comment that the generalisability of the results obtained in this study is limited and caution must be exercised in their interpretation. However, as is the case with investigations that measure multiple variables, validation with larger cohorts or further analyses on select candidates using a new set of samples will allow for assessment of reproducibility and biological heterogeneity. Two proteins, PDI and PGRMC2, are of interest for further characterization given their association with the key parturition hormones, estrogen and progesterone. More informative data may help correlate these results with the biology and progression of preterm labor and/or their biomarker potential given that differentially expressed proteins released from the choriodecidua may be present in the cervicovaginal fluid.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by scholarships and research funding from the University of Melbourne as well the Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne to Renu Shankar and Fiona Cullinane. Transcriptional profiling was supported by the National Institutes of Health (HD049847 to Eric K Moses.) and conducted in facilities constructed with support from a Research Facilities Improvement Program grant C06 RR017515 from the National Center for Research Resources. The Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software licence is supported by National Institutes of Health grants MH059490, HL045522 and HL028972. Matthew P Johnson is the recipient of a Cowles Postdoctoral Fellowship. We thank Clinical Research Assistant Dr Alfia Al-Ghafra and Clinical Research Midwives Ms Sue Nisbet and Ms Sue Duggan for assistance with collecting the samples used in this study.

Contributor Information

Renu Shankar, Email: rshankar@unimelb.edu.au, Research Fellow, Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, The University of Melbourne, Australia & Pregnancy Research Centre, Department of Perinatal Medicine, The Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne. Australia.

Matthew P. Johnson, Email: mjohnson@sfbrgenetics.org, Postdoctoral Scientist, Department of Genetics, Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research, San Antonio, Texas, U.S.A.

Nicholas A. Williamson, Email: nawill@unimelb.edu.au, Senior Research Fellow, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, The Bio21 Molecular Science and Biotechnology Institute, The University of Melbourne, Australia.

Fiona Cullinane, Email: Fiona.Cullinane@mailn.hse.ie, Clinical Research Fellow, Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, The University of Melbourne, Australia & Pregnancy Research Centre, Department of Perinatal Medicine, The Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia.

Anthony W. Purcell, Email: apurcell@unimelb.edu.au, Associate Professor, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, The Bio21 Molecular Science and Biotechnology Institute, The University of Melbourne, Australia.

Eric K. Moses, Email: moses@sfbrgenetics.org, Associate Scientist, Department of Genetics, Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research, San Antonio, Texas, U.S.A.

Shaun P. Brennecke, Email: s.brennecke@unimelb.edu.au, Professor, Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, The University of Melbourne, Australia & Director, Pregnancy Research Centre, Department of Perinatal Medicine, The Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia.

References

- 1.Romero R, Espinoza J, Kusanovic J, et al. The preterm parturition syndrome. Bjog. 2006;113(Suppl 3):17–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell SC, Malak TM. Preterm Labour. Churchill Livingstone; New York: 1997. Structural and Cellular Biology of the Fetal Membranes; pp. 401–428. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldenberg RL, Iams JD, Mercer BM, et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: toward a multiple-marker test for spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(3):643–651. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.116752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haddad R, Tromp G, Kuivaniemi H, et al. Human spontaneous labor without histologic chorioamnionitis is characterized by an acute inflammation gene expression signature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(2):394, e391–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.08.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramagli LS. Quantifying protein in 2D PAGE Solubilization Buffers. From: Methods in Molecular Biology Vol 112: 2D Proteome Analysis Protocols. 1999:99–103. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-584-7:99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaplanski G, Marin V, Montero-Julian F, Mantovani A, Farnarier C. IL-6: a regulator of the transition from neutrophil to monocyte recruitment during inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2003;24(1):25–29. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Croker BA, Krebs DL, Zhang JG, et al. SOCS3 negatively regulates IL-6 signaling in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(6):540–545. doi: 10.1038/ni931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ognjanovic S, Bryant-Greenwood GD. Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor, a novel cytokine of human fetal membranes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;187(4):1051–1058. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.126295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasukawa H, Ohishi M, Mori H, et al. IL-6 induces an anti-inflammatory response in the absence of SOCS3 in macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(6):551–556. doi: 10.1038/ni938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laham N, Brennecke SP, Bendtzen K, Rice GE. Differential release of interleukin-6 from human gestational tissues in association with labour and in vitro endotoxin treatment. Journal of Endocrinology. 1996;149(3):431–439. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1490431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salmon JE, Girardi G, Holers VM. Complement activation as a mediator of antiphospholipid antibody induced pregnancy loss and thrombosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(Suppl 2):ii46–50. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.suppl_2.ii46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeuchi O, Sato S, Horiuchi T, et al. Cutting edge: role of Toll-like receptor 1 in mediating immune response to microbial lipoproteins. J Immunol. 2002;169(1):10–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lockwood CJ, Toti P, Arcuri F, et al. Mechanisms of abruption-induced premature rupture of the fetal membranes: thrombin-enhanced interleukin-8 expression in term decidua. Am J Pathol. 2005;167(5):1443–1449. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61230-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi F, Means TK, Luster AD. Toll-like receptors stimulate human neutrophil function. Blood. 2003;102(7):2660–2669. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortunato SJ, Menon R. Distinct molecular events suggest different pathways for preterm labor and premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(7):1399–1405. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.115122. discussion 1405–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang Y, Zhao Q, Chen GQ. Phospholipid scramblase 1. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 2006;58(6):501–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hart SP, Dougherty GJ, Haslett C, Dransfield I. CD44 regulates phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophil granulocytes, but not apoptotic lymphocytes, by human macrophages. J Immunol. 1997;159(2):919–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottlieb RA, Kitsis RN. Seeing death in the living. Nat Med. 2001;7(12):1277–1278. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leroy MJ, Dallot E, Czerkiewicz I, Schmitz T, Breuiller-Fouche M. Inflammation of choriodecidua induces tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated apoptosis of human myometrial cells. Biol Reprod. 2007;76(5):769–776. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.058057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaur U, Aggarwal BB. Regulation of proliferation, survival and apoptosis by members of the TNF superfamily. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66(8):1403–1408. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00490-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu H, Ma Y, Pagliari LJ, et al. TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis of macrophages following inhibition of NF-kappa B: a central role for disruption of mitochondria. J Immunol. 2004;172(3):1907–1915. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alexander JM, Bikkal HA, Zervas NT, Laws ER, Jr, Klibanski A. Tumor-specific expression and alternate splicing of messenger ribonucleic acid encoding activin/transforming growth factor-beta receptors in human pituitary adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(2):783–790. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.2.8636304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krause CD, He W, Kotenko S, Pestka S. Modulation of the activation of Stat1 by the interferon-gamma receptor complex. Cell Res. 2006;16(1):113–123. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lappas M, Permezel M, Georgiou HM, Rice GE. Regulation of proinflammatory cytokines in human gestational tissues by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma: effect of 15-deoxy-Delta(12,14)-PGJ(2) and troglitazone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(10):4667–4672. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monick MM, Robeff PK, Butler NS, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity negatively regulates stability of cyclooxygenase 2 mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(36):32992–33000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shanahan CM, Cary NR, Osbourn JK, Weissberg PL. Identification of osteoglycin as a component of the vascular matrix. Differential expression by vascular smooth muscle cells during neointima formation and in atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17(11):2437–2447. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schultz-Norton JR, McDonald WH, Yates JR, Nardulli AM. Protein disulfide isomerase serves as a molecular chaperone to maintain estrogen receptor alpha structure and function. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(9):1982–1995. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winkler M, Kemp B, Classen-Linke I, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha and progesterone receptor A and B concentration and localization in the lower uterine segment in term parturition. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2002;9(4):226–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrison JJ, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith SK. Messenger RNA encoding thiol protein disulphide isomerase in amnion, chorion and placenta in human term and preterm labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103(9):873–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirai Y, Utsugi K, Takeshima N, et al. Putative gene loci associated with carcinogenesis and metastasis of endocervical adenocarcinomas of uterus determined by conventional and array-based CGH. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(4):1173–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peluso JJ, Pappalardo A, Losel R, Wehling M. Progesterone membrane receptor component 1 expression in the immature rat ovary and its role in mediating progesterone’s antiapoptotic action. Endocrinology. 2006;147(6):3133–3140. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereira L, Reddy AP, Jacob T, et al. Identification of novel protein biomarkers of preterm birth in human cervical-vaginal fluid. J Proteome Res. 2007;6(4):1269–1276. doi: 10.1021/pr0605421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gottlieb RA. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Biol Signals Recept. 2001;10(3–4):147–161. doi: 10.1159/000046884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bondanza A, V, Zimmermann S, Rovere-Querini P, et al. Inhibition of phosphatidylserine recognition heightens the immunogenicity of irradiated lymphoma cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2004;200(9):1157–1165. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rabinovich GA, Daly G, Dreja H, et al. Recombinant galectin-1 and its genetic delivery suppress collagen-induced arthritis via T cell apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1999;190(3):385–398. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.3.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fortunato SJ, Menon RP, Swan KF, Menon R. Inflammatory cytokine (interleukins 1, 6 and 8 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha) release from cultured human fetal membranes in response to endotoxic lipopolysaccharide mirrors amniotic fluid concentrations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(6):1855–1861. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70221-1. discussion 1861–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Challis JRG, Matthews SG, Gibb W, Lye SJ. Endocrine and paracrine regulation of birth at term and preterm. Endocrine Reviews. 2000;21(5):514–550. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.5.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lappas M, Permezel M, Georgiou HM, Rice GE. Nuclear factor kappa B regulation of proinflammatory cytokines in human gestational tissues in vitro. Biol Reprod. 2002;67(2):668–673. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod67.2.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marvin KW, Keelan JA, Eykholt RL, Sato TA, Mitchell MD. Use of cDNA arrays to generate differential expression profiles for inflammatory genes in human gestational membranes delivered at term and preterm. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8(4):399–408. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.4.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.