Abstract

Antagonists of myostatin, a blood-borne negative regulator of muscle growth produced in muscle cells, have shown considerable promise for enhancing muscle mass and strength in rodent studies and could serve as potential therapeutic agents for human muscle diseases. One of the most potent of these agents, follistatin, is both safe and effective in mice, but similar tests have not been performed in nonhuman primates. To assess this important criterion for clinical translation, we tested an alternatively spliced form of human follistatin that affects skeletal muscle but that has only minimal effects on nonmuscle cells. When injected into the quadriceps of cynomolgus macaque monkeys, a follistatin isoform expressed from an adeno-associated virus serotype 1 vector, AAV1-FS344, induced pronounced and durable increases in muscle size and strength. Long-term expression of the transgene did not produce any abnormal changes in the morphology or function of key organs, indicating the safety of gene delivery by intramuscular injection of an AAV1 vector. Our results, together with the findings in mice, suggest that therapy with AAV1-FS344 may improve muscle mass and function in patients with certain degenerative muscle disorders.

INTRODUCTION

Severe weakness of the quadriceps is a defining feature of several neuromuscular disorders, including sporadic inclusion body myositis, Becker muscular dystrophy, and myotonic dystrophies. Despite progress in understanding the pathophysiological basis of these conditions, few treatment strategies have produced satisfactory results. Androgen steroids, popular among athletes, offer a means to enhance strength but pose long-term risks (1). Glucocorticosteroids, used in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) (2, 3), improve muscle strength and function in the short term, but their long-term benefits remain unclear (4). Gene manipulations to treat genetic muscle disease, including gene replacement (5–8), exon skipping (9), and mutation suppression (10, 11), are being assessed in early clinical trials, but lasting benefits have yet to be established. Moreover, these approaches are not applicable to muscle disorders that lack a defined gene defect, such as facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, characterized by weakness and degeneration of voluntary muscles (12).

An alternative strategy, inhibition of the myostatin pathway, has shown substantial promise in preclinical studies, in which significant enlargement of muscle mass and increased muscle strength have been noted (13–17). Myostatin is a member of the transforming growth factor–β (TGF-β) superfamily of signal peptides that is expressed specifically in developing and adult skeletal muscle (18). In myogenic cells, myostatin induces down-regulation of Myo-D, an early marker of muscle differentiation, and decreases the expression of Pax-3 and Myf-5, which encode transcriptional regulators of myogenic cell proliferation (19).

Myostatin signaling acts through the activin receptor type IIB (ActRIIB) on skeletal muscle, triggering a cascade of intracellular events (20). After recruitment of a co-receptor, followed by sequential phosphorylation of TGF-β–specific Smads, the protein complex translocates to the nucleus, where it controls the expression of specific myogenic regulatory genes (19–21). Inhibition of this pathway results in muscle hypertrophy and increased strength. Indeed, injection of a neutralizing monoclonal antibody to myostatin led to increased skeletal muscle mass in mice without undue side effects (22). This method was found to be safe in a subsequent clinical trial, although dose escalation was limited by cutaneous hypersensitivity restricting potential efficacy (23).

Several myostatin-binding proteins capable of regulating myostatin activity have been discovered. Follistatin is an especially robust antagonist of myostatin and has even shown muscle-enhancing effects beyond those predicted by myostatin inhibition alone (24). This naturally occurring glycoprotein, which prevents myostatin from binding to ActRIIB receptors on muscle cells (14), occurs in two distinct isoforms (FS288 and FS315), a result of alternative splicing of the precursor messenger RNA (25, 26). FS288, but not FS315, functions in reproductive physiology collaboratively with activin and inhibins of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (27, 28), which suggests that FS315 would be the more reliable isoform for exclusively targeting muscle. In a previous study, we tested the effects of follistatin in a small animal model by injecting normal and dystrophic mice intramuscularly with an adeno-associated virus serotype 1 (AAV1) expressing the human FS344 transgene, which encodes the FS315 protein isoform. This treatment led to significant increases in muscle mass and strength even when given to older mice showing repeated cycles of muscle degeneration and regeneration (29). Thus, using a relatively noninvasive strategy in mice, we were able to achieve long-term gene expression with positive effects on degenerating muscle.

Despite the safety and potent myostatin-inhibitory effects of AAV1-FS344 in mice, such results are not necessarily applicable to humans. We therefore extended our FS344 gene transfer technology to a non-human primate, the cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis), to establish a paradigm for strengthening the quadriceps muscle that could serve as the basis for testing in patients. We report here that injection of AAV1-FS344 was well tolerated by all macaques and led to increased muscle mass and strength.

RESULTS

Gene delivery to muscle

We injected the vector AAV1-FS344 under the control of the ubiquitously strong cytomegalovirus promoter (CMV-FS) or the muscle creatine kinase promoter (MCK-FS), which provides muscle-specific gene expression, into the right quadriceps muscle of six normal cynomolgus macaques. Briefly, each animal received three 500-μl doses of the vector injected at 3-cm intervals in a diagonal line extending from a proximal site (7 cm below the inguinal ligament) to the midpoint of the quadriceps muscle. This pattern was intended to provide vector to adjacent bellies of the vastus medialis, rectus femoris, and vastus lateralis muscles (Fig. 1A). A total dose of 1 × 1013 vector genomes was administered per treatment. The product of the human FS344 transgene used in these studies has 98% homology with follistatin in nonhuman primates. In all comparisons, the contralateral quadriceps served as a noninjected control. To control for any remote effects of naturally occurring follistatin, we conducted parallel studies in age-matched, untreated macaques. Because gene transfer can be compromised by the immune system, as demonstrated in both preclinical studies (30–32) and human gene therapy trials (33), we maintained the animals with the immunosuppressants tacrolimus (2.0 mg/kg) and mycophenylate mofetil (50 mg/kg) beginning 2 weeks before vector administration.

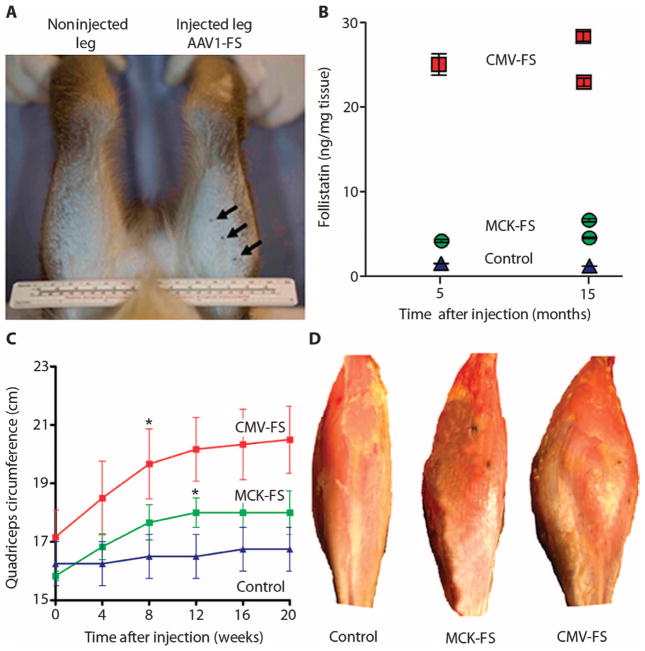

Fig. 1.

Injection of AAV1-FS344 into the quadriceps increases muscle mass in cynomolgus macaques. (A) AAV1-FS344 was administered by three direct unilateral injections into the right quadriceps muscle (total dose of 1 × 1013 vector genomes in 1.5 ml). Indian ink tattoos, drawn immediately after the injections, allowed the vector to be localized at necropsy. (B) Concentrations of human follistatin in muscle, as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay at 5 and 15 months after injection. The values represent individual macaques with four muscle samples analyzed per macaque. (C) Increases in quadriceps size after injection of AAV1-FS344, driven by either the CMV-FS or the MCK-FS promoter. Mean ± SEM values for three macaques per treatment are shown. Asterisks indicate a 15% increase over baseline at 8 weeks in the CMV-FS group (P = 0.01) and a 10% increase in the MCK-FS group (P = 0.02). (D) Quadriceps enlargement seen at necropsy of MCK-FS and CMV-FS macaques.

Bioactivity of AAV1-FS344

In both the CMV-FS (n = 3) and the MCK-FS (n = 3) cohorts, we necropsied one macaque at 5 months and two at 15 months after vector administration and then measured concentrations of human follistatin in the quadriceps muscle of each animal. The three CMV-FS–treated primates had marked increases of follistatin (>20 ng per milligram tissue) at both 5 and 15 months after gene transfer, in contrast to the minimally elevated concentrations in the MCK-FS–treated group (Fig. 1B).

We also measured the external circumference of the thigh muscles at the midpoint of the quadriceps muscle every 4 weeks after gene transfer through week 20 (before any animals were necropsied). Macaques in the CMV-FS group showed a 15% increase in quadriceps circumference over baseline (P = 0.01) at 8 weeks after treatment, followed by growth stabilization through week 20 (Fig. 1C). Although quadriceps size increased by 10% (P = 0.02) in the MCK-FS group, this beneficial effect was delayed relative to the CMV-FS group (12 weeks versus 8 weeks), and by week 16, there was an overlap between quadriceps measurements in the MCK-FS group and the untreated controls. The gains in quadriceps circumference achieved with AAV1-FS344 were maintained from week 20 to week 60 after treatment for CMV-FS [20.5 ± 1.15 cm (SEM) at 20 weeks (n = 3) versus 21.75 cm at 60 weeks (n = 2)] and MCK-FS [18.17 ± 0.46 cm (SEM) at 20 weeks (n = 3) versus 19.75 cm at 60 weeks (n = 2)] without any appreciable loss. Enlargement of the quadriceps muscle in these animals was sufficient to be appreciated by gross inspection of the excised quadriceps at the time of necropsy (5 months after injection) (Fig. 1D). Together, the results show that expression of the FS344 transgene under control of the CMV promoter results in more muscle follistatin than does the MCK promoter, leading to more robust increases in quadriceps size.

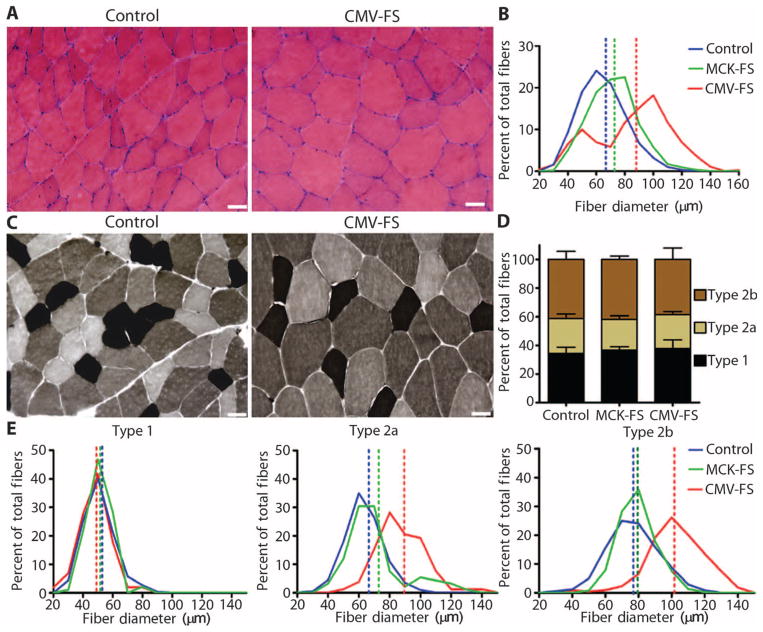

Histologic sections comparing control and follistatin-treated quadriceps muscles showed an increase in mean fiber size diameter at 20 weeks in both the CMV-FS [87.7 ± 1.30 μm (SEM), P = 0.001)] and the MCK-FS (73.0 ± 0.74 μm, P = 0.04) groups (n = 3 each) relative to untreated controls (65.5 ± 0.62 μm) (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S1A). Follistatin treatment primarily affected fast-twitch oxidative glycolytic type 2a and fast-twitch glycolytic type 2b fibers. Myofibrillar adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) staining (pH 4.6) revealed increases in the mean diameters of both type 2a [CMV-FS: 85.4 ± 2.13 μm (SEM), P < 0.001; MCK-FS: 71.4 ± 2.53 μm, P = not significant (n.s.), versus controls, 66.3 ± 1.15 μm] and type 2b [CMV-FS: 102.3 ± 1.13 μm (SEM), P < 0.001; MCK-FS: 79.3 ± 0.56 μm, P = n.s., versus controls, 77.0 ± 0.95 μm] fibers without alterations in the ratio of muscle fiber types (types 1, 2a, and 2b each represented about one-third of total fibers) (Fig. 2, C to E, and fig. S1B). Therefore, the enhancement of type 2 fibers by CMV-FS treatment is likely to augment high force–generating fibers, used for getting to a standing position or compensating for knee weakness.

Fig. 2.

AAV1-FS344 treatment causes myofiber hypertrophy and affects fast-twitch type 2 myofibers in the quadriceps muscle. (A) H&E staining of quadriceps muscle reveals myofiber hypertrophy in CMV-FS macaque (right) compared to untreated control (left). Scale bars, 20 μm. (B) Morphometric analysis of quadriceps muscle at 5 months after AAV1-FS344 injection demonstrates a significant increase in mean fiber diameter (dotted lines) of both MCK-FS (P < 0.04, n = 3 muscle samples) and CMV-FS (P < 0.001, n = 3 muscle samples) animals relative to untreated controls (n = 3 muscle samples). (C) Representative fiber types determined by ATPase staining (pH 4.6) of quadriceps muscle from CMV-FS macaques (right) and untreated controls (left). Scale bars, 20 μm. (D) Fiber type ratios in control, CMV-FS, and MCK-FS muscles. Mean ± SEM values for three animals are shown. (E) Mean ± SEM fiber diameters (dotted lines) of fast-twitch oxidative glycolytic type 2a and fast-twitch glycolytic 2b fibers show significant increases in three CMV-FS animals relative to untreated controls (P < 0.001); slow-twitch oxidative type 1 fibers are not affected. Similar but not statistically significant trends are apparent in the MCK-FS group (n = 3).

Correlation with muscle strength

In principle, the muscle enlargement we observed would be expected to correlate with increases in muscle strength. This prediction can be technically challenging to test in macaques, requiring in situ quadriceps muscle measurements in anesthetized animals. Nonetheless, we assessed muscle strength in two CMV-FS and two MCK-FS macaques by comparing measurements for the treated leg with those for the contralateral untreated side (technical problems prevented data interpretation for the second CMV-FS macaque). Twitch force measurements in treated muscles of the two MCK-FS macaques showed an 11.8% and a 35.7% increase, respectively, relative to findings in the opposite untreated side (Table 1). These same animals had 12.3% and 77.9% increases in tetanic force over measurements of the untreated side. In the single CMV-FS macaque, the twitch force was increased by 26.3% and the tetanic force by 12.5%. The greatest percent increases in twitch and tetanic forces were found in the quadriceps muscle of an MCK-FS macaque (MCK-FS #2, Table 1) whose untreated leg showed the lowest force generation among all of the legs tested. This result may indicate that increased muscle size after follistatin treatment does not necessarily result in a proportional stronger force generation, as has been seen with other approaches to myostatin inhibition (34). Additional study will be required to resolve this issue, yet the enhancement of force generation after treatment with both CMV-FS and MCK-FS supports the clinical effort to improve muscle mass and strength.

Table 1.

Strength measurements of AAV1-FS344–treated quadriceps in macaques measured in newtons (N).

| Treatment group | Twitch force (N) |

Tetanic force (N) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control leg | Treated leg | % Increase | Control leg | Treated leg | % Increase | |

| MCK-FS #1 | 17.0 | 19.0 | 11.8 | 65.0 | 73.0 | 12.3 |

| MCK-FS #2 | 4.2 | 5.7 | 35.7 | 24.0 | 42.0 | 77.9 |

| CMV-FS | 19.0 | 24.0 | 26.3 | 64.0 | 72.0 | 12.5 |

Absence of immune response to gene transfer

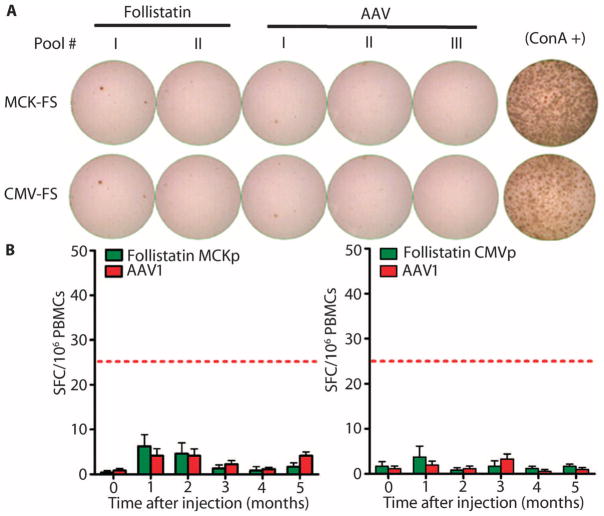

Despite administering immunosuppressive drugs to both the MCK-FS–treated and the CMV-FS–treated macaques, we could not be certain that we had avoided immune responses to the AAV capsid and human follistatin. Thus, we used the enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) assay to detect antigen-induced secretion of cytokines by T cells isolated monthly from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). At no time during the study did we observe antigen-specific interferon-γ (IFN-γ) responses to either follistatin or the AAV1 capsid (Fig. 3) in either the MCK-FS or the CMV-FS group; this finding suggests that, under the condition of this experiment, therapy with the FS344 gene expressed by an adeno-associated viral vector did not elicit an immune response.

Fig. 3.

The FS344 transgene and the AAV1 capsid do not produce cellular immune responses. (A) PBMCs were isolated before injection and at monthly intervals thereafter and then were stimulated with human follistatin peptide pools (I and II) and AAV1 capsid peptide pools (I, II, and III) or with concanavalin A (ConA; positive control). IFN-γ release was measured with an ELISpot assay; representative data obtained at 5 months after injection are shown. (B) Mean ± SEM SFCs for each antigen per 1 × 106 PBMCs are shown over 5 months for each treatment group (n = 3). Increases in SFC did not exceed 25, the threshold (red dashed line) for significance with this assay in our laboratory.

Lack of toxicity from transgene expression

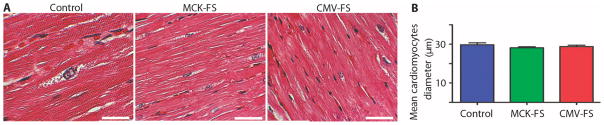

To assess the long-term safety of this treatment, we performed a panel of hematologic and biochemical tests every 4 weeks for the duration of the 15-month study. Neither the MCK-FS nor the CMV-FS group (n = 3 each) showed abnormal changes from baseline in liver, kidney, or muscle function or in hematopoiesis (Table 2). Normal serum concentrations of creatine kinase confirmed histologic studies of skeletal and cardiac muscle, demonstrating that gene transfer does not cause muscle fiber breakdown (Fig. 4). Female macaques in the CMV-FS or MCK-FS group (n = 1 each) maintained normal menstrual cycles throughout the study, and sperm isolated from a CMV-FS male macaque showed normal motility and counts (tables S1 and S2 and fig. S2). Additionally, concentrations of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), estradiol, and testosterone remained within normal physiological concentrations compared to the baseline values. We did find a slight increase in estradiol and LH concentrations in one macaque (MCK-FS #2); however, these were within normal ranges and within the normal fluctuations seen in vivarium-housed nonhuman primates (Table 3). A complete necropsy was performed on all macaques at either 5 or 15 months after treatment. To further evaluate the effects of gene transfer on key organs, we collected heart, liver, lung, spleen, kidney, testis, ovary, and uterus and processed the tissue sections by staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for a blinded histopathologic analysis by a board-certified veterinary pathologist (S.E.W.). Examination of the heart showed that this organ was of normal size in both treated and untreated macaques. Moreover, in stained sections of cardiac tissue, cardiomyocytes did not show evidence of hypertrophy (Fig. 4A). Morphometric analysis revealed no differences in cardiomyocyte diameter among CMV-FS, MCK-FS, and control animals [28.78 ± 0.71 μm (SEM) versus 28.17 ± 0.50 μm versus 29.7 ± 1.03 μm, respectively] (Fig. 4B). Similarly, none of the other organs examined had abnormalities that could be attributed to gene transfer. These findings suggest the long-term safety of AAV1-FS344 therapy controlled by the CMV or MCK promoter in nonhuman primates.

Table 2.

Blood and serum chemistry profiles of the AAV1-FS344–treated macaques. Hematology and serum chemistries were monitored throughout the study monthly after gene transfer with CMV-FS and MCK-FS. Data from 5 and 15 months are shown. The values are means ± SD (n = 3); there were no significant changes at any time. CK, creatine kinase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; GGT, γ-glutamyltranspeptidase.

| MCK-FS |

CMV-FS |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 5 Months after injection | 15 Months after injection | Baseline | 5 Months after injection | 15 Months after injection | |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dl) | 11.7 ± 1.2 | 12.3 ± 0.7 | 13.5 | 12.9 ± 0.9 | 12.9 ± 0.3 | 12.6 |

| Leukocytes (103/mm3) | 9.4 ± 3.6 | 11.0 ± 1.8 | 7.5 | 13.2 ± 1.7 | 10.8 ± 2.8 | 15.5 |

| Platelets (103/mm3) | 444.7 ± 78.6 | 473.7 ± 101.5 | 448.5 | 475.3 ± 21.2 | 470.0 ± 10.8 | 432.0 |

| CK (U/liter) | 282.3 ± 123.3 | 103.3 ± 34.0 | 261.0 | 315.1 ± 436.8 | — | 141.0 |

| ALT (U/liter) | 29.7 ± 12.9 | 19.7 ± 2.1 | 31.5 | 28.7 ± 10.3 | 21.7 ± 4.6 | 29.5 |

| AST (U/liter) | 35.3 ± 3.51 | 34.7 ± 9.9 | 37.5 | 44.3 ± 11.4 | 31.7 ± 6.0 | 35.5 |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 19.0 ± 1.0 | 12.3 ± 1.5 | 16.0 | 16.3 ± 4.9 | 16.0 ± 4.4 | 18.0 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 |

| GGT (U/liter) | 72.0 ± 28.8 | 92.0 ± 38.7 | 77.5 | 77.0 ± 20.7 | 71.3 ± 18.2 | 75.0 |

Fig. 4.

AAV1-FS344 treatment does not cause hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes. (A) H&E staining of cardiac muscle from boththe MCK-FSand the CMV-FS groups reveals normal cardiac muscle histology compared with nontreated controls. Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) Morphometric analysis shows similar mean ± SEM diameters of cardiomyocytes from AAV1-FS344–treated macaques (MCK-FS and CMV-FS groups) compared with untreated controls (n = 3 per group).

Table 3.

Hormonal findings in AAV1-FS344–treated cynomolgus macaques. Hormonal concentrations were followed in each cynomolgus macaque after gene transfer. FSH, LH, estradiol, and testosterone showed little change from baseline. Concentrations from each individual animal can be traced by number. Empty slots at 15 months were the result of previous necropsies (PN). The widest variations were seen in the male testosterone concentrations. The baseline values of testosterone were low as seen in some vivarium-housed macaques. Those with low values remained in the same range after gene transfer. Each value represents a single animal, reported in the same order at each test interval. The broad fluctuations of some hormone concentrations are consistent with findings in macaques held in vivariums.

| Time point | Animal no. | FSH (ng/ml) |

LH (ng/ml) |

Estradiol (pg/ml) |

Testosterone (ng/ml) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | Females | Males | ||

| Baseline | 1 | 0.53 | 1.7 | 0.34 | 0.57 | 49.08 | 0.13 |

| 2 | 0.74 | 1.39 | 2.21 | 1.03 | 17.65 | 8.28 | |

| 3 | 0.39 | 0.35 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | 0.34 | 0.18 | 0.12 | ||||

| 5 Months | 1 | 0.52 | 1.65 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 74.22 | 0.27 |

| 2 | 0.42 | 1.39 | 0.78 | 2.35 | 61.3 | 9.02 | |

| 3 | 0.5 | 0.55 | 4.99 | ||||

| 4 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 1.67 | ||||

| 15 Months | 1 | PN | 1.21 | PN | 0.64 | 72.01 | PN |

| 2 | 0.29 | 2.42 | 0.23 | 2.34 | 56.54 | 5.48 | |

| 3 | PN | PN | PN | ||||

| 4 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 7.42 | ||||

DISCUSSION

In this study, therapy with an isoform of human follistatin delivered by an AAV1 vector to quadriceps muscle in cynomolgus macaques resulted in increased muscle size and strength. Expression of the transgene, FS344 complementary DNA (cDNA), which encodes the soluble circulating 315–amino acid follistatin protein isoform (35), affected skeletal muscle exclusively; the likelihood of an effect on non-muscle tissue is low, owing to the poor affinity of the FS344 product for heparan sulfate proteoglycan–binding sites on cell surfaces (36). We did not observe any treatment-related pathologic changes in major organ systems by analysis of serum chemistries or by direct histologic examination. Our results also indicate that AAV1-FS344 treatment does not appear to interfere with reproductive physiology in primates, as serum estradiol, testosterone, LH, and FSH concentrations remained similar to baseline throughout the study.

The FS344 transgene exhibited long-term expression for up to 15 months after gene transfer. Muscle growth was apparent in both the MCK-FS and the CMV-FS groups for the first 12 weeks after treatment, after which the growth rates appeared to stabilize. This result suggests that, after a peak increase in growth, a feedback loop sustains the enlarged muscle fibers while preventing uncontrolled growth. This model is consistent with observations of spontaneous myostatin inhibition seen in cattle or in mice lacking the myostatin gene (18, 37). The CMV-FS had the largest effect on muscle size, which suggests that dosage of follistatin is important and that the CMV promoter is superior to the MCK promoter for high-level expression of transgenes in the muscle.

The potential use of AAV1-FS344 for muscle strengthening has important implications for patients with muscle diseases. In DMD, the most common severe form of childhood muscular dystrophy, experimental and clinical gene replacement strategies use a small dystrophin cDNA designed to fit into an AAV vector (38). Co-delivery of the small dystrophin fragment with a second growth-enhancing agent insulin-like growth factor 1 resulted in full functional recovery in the mdx mouse (39). We suggest that FS344 could fill a similar role when co-delivered with small dystrophins. Other forms of muscular dystrophy might also respond to FS344 gene therapy. In facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, for example, in which gene replacement or other types of gene manipulation are not feasible because of the absence of a specific gene defect, one might achieve a clinically significant result by targeting AAV1-FS344 to the focal muscle groups that are affected by the disease (12). Finally, the gene therapy we describe could be useful against acquired disorders, such as sporadic inclusion body myositis, in which quadriceps muscle weakness is an important cause of disability (40).

Despite the beneficial effects of follistatin gene therapy that we demonstrated in macaques, these animals did not have a degenerative muscle disease, and so our findings may not translate successfully to clinically effective treatments for such diseases. In particular, genetic disorders of muscle are characterized by cycles of degeneration and regeneration, which could lead to loss of the nonintegrating AAV1 vector, hence diminishing therapeutic efficacy. Nevertheless, there are data suggesting that this may not be a problem and that AAV1-FS344 therapy may in fact be useful in patients. First, myostatin inhibition with AAV1-FS344 leads to increased muscle size and strength and lowers serum creatine kinase in the mdx mouse model of DMD (29) despite the pronounced cycles of muscle degeneration-regeneration in this animal model. The benefits of AAV1-FS344 treatment persist for more than a year in these mice, which suggests that as muscle strength and size increased, a protective shield developed to guard muscle from further degeneration-regeneration (29). In addition, in human DMD, the number of muscle fibers undergoing regeneration at any one time is very limited relative to the mdx mouse (41). Second, in another disease that might be treated with AAV1-FS344 therapy, sporadic inclusion body myositis, the pathologic process is very slow, with ambulation persisting for a mean 13 ± 8 years after onset (42). The primary focus for our gene therapy approach is the quadriceps, as loss of strength in this particular muscle group is minimal over any 6-month period (43), predicting only minor loss of the viral vector. Finally, by establishing that follistatin can inhibit myostatin with an adeno-associated virus, our studies provide the basis for tests of other integrating viruses, such as lentivirus, which transduce muscle and stem cells effectively and may be less affected by rounds of muscle degeneration and regeneration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

The cynomolgus macaques were a gift from Battelle and were housed at the nonhuman primate facility of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. Protocols for all animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the Department of Agriculture Animal Welfare Act and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Cloning and AAV production

The cDNA for the human FS344 gene was obtained from Origene and cloned by Kpn l/Xba l restriction into an AAV inverted terminal repeat vector plasmid containing the MCK promoter or by Xho l/Bam HI restriction into a second AAV vector plasmid containing the CMV promoter. Recombinant AAV1 vectors were produced by a standard triple-transfection calcium phosphate precipitation method using human embryonic kidney 293 cells (44, 45). The production plasmids were (i) pAAV.CMV-FS or pAAV.MCK-FS, (ii) rep2-cap1–modified AAV helper plasmid encoding the cap serotype 1, and (iii) an adeno-virus type 5 helper plasmid (pAdhelper). Viruses were purified from clarified 293 cell lysates by sequential iodixanol gradient purification and ion exchange column chromatography with a linear NaCl salt gradient for particle elution. Vector genome titers were determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QPCR) as described (46). Primer and probe sequences are provided in table S3.

Follistatin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Muscle follistatin was evaluated with a human follistatin immunoassay kit (Quantikine; R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, total soluble protein was isolated from the muscle tissue with CelLytic MT Mammalian Tissue Lysis reagent (Sigma). A total of 100 μg of protein was loaded per well, and muscle follistatin concentrations were determined against a standard curve made with recombinant human follistatin provided by the manufacturer.

Morphometrics

During necropsy, skeletal muscles were dissected and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen–cooled isopentane. Cryosections, 8 to 10 μm thick, were stained with either H&E or myofibrillar ATPase (pH 4.6) for analysis of fiber diameters. For each animal, 12 random 20× images were captured with a Zeiss AxioCam MRC5 camera. For each fiber type, the smallest diameter was measured with a calibrated micrometer using AxioVision 4.2 software (Zeiss). A frequency distribution was used to determine percentage of fibers within 20-μm intervals. Cardiac muscle was collected during necropsy, and formalin-fixed tissues were sectioned at 4 μm and stained with H&E for analysis of cardiomyocyte diameter. About 400 cardiomyocytes were measured for each animal.

Muscle physiology

These experiments were performed immediately before necropsy. Macaques were sedated with Telazol (3 to 6 mg/kg) and maintained on isoflurane and oxygen (4 to 5%). Buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg) was given to minimize pain. The femoral nerve was dissected and affixed with miniature platinum-stimulating electrodes connected to a stimulator (STIM2; Scientific Instruments). Quadriceps muscle was prepared free of skin, fascia, and connective tissue. The hip was immobilized with restraining straps around the lower waist and upper thigh. The distal tendon was disconnected at the patella and secured to a force transducer (Imada, DS-2) for assessment of twitch and tetanic contractions after muscle stimulation.

Immune response studies

PBMCs were collected at baseline and monthly intervals after vector delivery and tested in an IFN-γ ELISpot assay for reactivity to human follistatin and AAV1 capsid antigens. Briefly, 96-well polyvinylidene difluoride microtiter plates (Millipore) were precoated with antibodies to macaque IFN-γ (U-Cytech), and 2 × 105 PBMCs in AIM-V medium containing 2% heat-inactivated human serum were added to each well. Duplicate wells contained pools of overlapping synthetic peptides at a concentration of 1 μg/ml (18 amino acids in length with an 11-residue overlap) prepared for the AAV1 capsid (104 peptides) and human follistatin (48 peptides; Genemed Synthesis). Plates were incubated at 37°C for 36 hours and developed for spot formation by using a second antibody to IFN-γ conjugated to enzyme followed by substrate. Spot-forming colonies (SFCs) in the microtiter wells were quantified with a CTL analyzer. Green fluorescent peptide pool served as the negative control, whereas concanavalin A was used as the positive control for cell viability. The number of spots was calculated by subtracting the number of negative control spots from each well.

Statistical analysis

We used means and SEM or SD to summarize results obtained with more than two macaques; otherwise, individual values are reported, and all statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software and paired t tests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. M. Shontz, Y. Davis, and Z. D. Van Wagoner for expert technical assistance and J. Gilbert for expert editorial assistance.

Funding: The Myositis Association and Jesse’s Journey, and a National Research Service Award fellowship to A.M.H.

Footnotes

Competing interests: J.R.M., B.K.K., and their institution (Nationwide Children’s Hospital) have filed a provisional patent on gene delivery of myostatin inhibitors and follistatin use.

Author contributions: J.K., C.R.H., A.M.H., L.R.R.-K., P.M.L.J., K.R.C., Z.S., and C.M.W. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; C.L.M., D.T., C.J.S., and W.R.T. performed experiments and analyzed data; S.E.W. performed blinded pathology and analyzed data; J.R.M. and B.K.K. designed experiments, analyzed data, wrote the manuscript, and obtained grant support.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Sjöqvist F, Garle M, Rane A. Use of doping agents, particularly anabolic steroids, in sports and society. Lancet. 2008;371:1872–1882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60801-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendell JR, Moxley RT, Griggs RC, Brooke MH, Fenichel GM, Miller JP, King W, Signore L, Pandya S, Florence J. Randomized, double-blind six-month trial of prednisone in Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1592–1597. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906153202405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moxley RT, III, Ashwal S, Pandya S, Connolly A, Florence J, Mathews K, Baumbach L, McDonald C, Sussman M, Wade C. Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology; Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society, Practice parameter: Corticosteroid treatment of Duchenne dystrophy: Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2005;64:13–20. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000148485.00049.B7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manzur AY, Kuntzer T, Pike M, Swan A. Glucocorticoid corticosteroids for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;23:CD003725. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003725.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendell JR, Rodino-Klapac LR, Rosales-Quintero X, Kota J, Coley BD, Galloway G, Craenen JM, Lewis S, Malik V, Shilling C, Byrne BJ, Conlon T, Campbell KJ, Bremer WG, Viollet L, Walker CM, Sahenk Z, Clark KR. Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2D gene therapy restores a-sarcoglycan and associated proteins. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:290–297. doi: 10.1002/ana.21732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerletti M, Negri T, Cozzi F, Colpo R, Andreetta F, Croci D, Davies KE, Cornelio F, Pozza O, Karpati G, Gilbert R, Mora M. Dystrophic phenotype of canine X-linked muscular dystrophy is mitigated by adenovirus-mediated utrophin gene transfer. Gene Ther. 2003;10:750–757. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregorevic P, Allen JM, Minami E, Blankinship MJ, Haraguchi M, Meuse L, Finn E, Adams ME, Froehner SC, Murry CE, Chamberlain JS. rAAV6-microdystrophin preserves muscle function and extends lifespan in severely dystrophic mice. Nat Med. 2006;12:787–789. doi: 10.1038/nm1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregorevic P, Blankinship MJ, Allen JM, Crawford RW, Meuse L, Miller DG, Russell DW, Chamberlain JS. Systemic delivery of genes to striated muscles using adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat Med. 2004;10:828–834. doi: 10.1038/nm1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aartsma-Rus A, Kaman WE, Weij R, den Dunnen JT, van Ommen GJ, van Deutekom JC. Exploring the frontiers of therapeutic exon skipping for Duchenne muscular dystrophy by double targeting within one or multiple exons. Mol Ther. 2006;14:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Deutekom JC, Janson AA, Ginjaar IB, Frankhuizen WS, Aartsma-Rus A, Bremmer-Bout M, den Dunnen JT, Koop K, van der Kooi AJ, Goemans NM, de Kimpe SJ, Ekhart PF, Venneker EH, Platenburg GJ, Verschuuren JJ, van Ommen GJ. Local dystrophin restoration with antisense oligonucleotide PRO051. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2677–2686. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barton-Davis ER, Cordier L, Shoturma DI, Leland SE, Sweeney HL. Aminoglycoside antibiotics restore dystrophin function to skeletal muscles of mdx mice. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:375–381. doi: 10.1172/JCI7866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tawil R. Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:601–606. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SJ, Reed LA, Davies MV, Girgenrath S, Goad ME, Tomkinson KN, Wright JF, Barker C, Ehrmantraut G, Holmstrom J, Trowell B, Gertz B, Jiang MS, Sebald SM, Matzuk M, Li E, Liang LF, Quattlebaum E, Stotish RL, Wolfman NM. Regulation of muscle growth by multiple ligands signaling through activin type II receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18117–18122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505996102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SJ, McPherron AC. Regulation of myostatin activity and muscle growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9306–9311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151270098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SJ. Regulation of muscle mass by myostatin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:61–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.012103.135836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner KR, McPherron AC, Winik N, Lee SJ. Loss of myostatin attenuates severity of muscular dystrophy in mdx mice. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:832–836. doi: 10.1002/ana.10385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodino-Klapac LR, Haidet AM, Kota J, Handy C, Kaspar BK, Mendell JR. Inhibition of myostatin with emphasis on follistatin as a therapy for muscle disease. Muscle Nerve. 2009;39:283–296. doi: 10.1002/mus.21244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-β superfamily member. Nature. 1997;387:83–90. doi: 10.1038/387083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langley B, Thomas M, Bishop A, Sharma M, Gilmour S, Kambadur R. Myostatin inhibits myoblast differentiation by down-regulating MyoD expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49831–49840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204291200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rebbapragada A, Benchabane H, Wrana JL, Celeste AJ, Attisano L. Myostatin signals through a transforming growth factor β-like signaling pathway to block adipogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7230–7242. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7230-7242.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massagué J, Wotton D. Transcriptional control by the TGF-β/Smad signaling system. EMBO J. 2000;19:1745–1754. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogdanovich S, Krag TO, Barton ER, Morris LD, Whittemore LA, Ahima RS, Khurana TS. Functional improvement of dystrophic muscle by myostatin blockade. Nature. 2002;420:418–421. doi: 10.1038/nature01154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner KR, Fleckenstein JL, Amato AA, Barohn RJ, Bushby K, Escolar DM, Flanigan KM, Pestronk A, Tawil R, Wolfe GI, Eagle M, Florence JM, King WM, Pandya S, Straub V, Juneau P, Meyers K, Csimma C, Araujo T, Allen R, Parsons SA, Wozney JM, Lavallie ER, Mendell JR. A phase I/II trial of MYO-029 in adult subjects with muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:561–571. doi: 10.1002/ana.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SJ. Quadrupling muscle mass in mice by targeting TGF-β signaling pathways. PLoS One. 2007;2:e789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimasaki S, Koga M, Esch F, Cooksey K, Mercado M, Koba A, Ueno N, Ying SY, Ling N, Guillemin R. Primary structure of the human follistatin precursor and its genomic organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4218–4222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimasaki S, Koga M, Esch F, Mercado M, Cooksey K, Koba A, Ling N. Porcine follistatin gene structure supports two forms of mature follistatin produced by alternative splicing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;152:717–723. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto O, Nakamura T, Shoji H, Shimasaki S, Hayashi Y, Sugino H. A novel role of follistatin, an activin-binding protein, in the inhibition of activin action in rat pituitary cells. Endocytotic degradation of activin and its acceleration by follistatin associated with cell-surface heparan sulfate. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13835–13842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sumitomo S, Inouye S, Liu XJ, Ling N, Shimasaki S. The heparin binding site of follistatin is involved in its interaction with activin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;208:1–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haidet AM, Rizo L, Handy C, Umapathi P, Eagle A, Shilling C, Boue D, Martin PT, Sahenk Z, Mendell JR, Kaspar BK. Long-term enhancement of skeletal muscle mass and strength by single gene administration of myostatin inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4318–4322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709144105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabatino DE, Mingozzi F, Hui DJ, Chen H, Colosi P, Ertl HC, High KA. Identification of mouse AAV capsid-specific CD8+ T cell epitopes. Mol Ther. 2005;12:1023–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J, Wu Q, Yang P, Hsu HC, Mountz JD. Determination of specific CD4 and CD8 T cell epitopes after AAV2- and AAV8-hF.IX gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2006;13:260–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao G, Lu Y, Calcedo R, Grant RL, Bell P, Wang L, Figueredo J, Lock M, Wilson JM. Biology of AAV serotype vectors in liver-directed gene transfer to nonhuman primates. Mol Ther. 2006;13:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manno CS, Pierce GF, Arruda VR, Glader B, Ragni M, Rasko JJ, Ozelo MC, Hoots K, Blatt P, Konkle B, Dake M, Kaye R, Razavi M, Zajko A, Zehnder J, Rustagi PK, Nakai H, Chew A, Leonard D, Wright JF, Lessard RR, Sommer JM, Tigges M, Sabatino D, Luk A, Jiang H, Mingozzi F, Couto L, Ertl HC, High KA, Kay MA. Successful transduction of liver in hemophilia by AAV-Factor IX and limitations imposed by the host immune response. Nat Med. 2006;12:342–347. doi: 10.1038/nm1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amthor H, Macharia R, Navarrete R, Schuelke M, Brown SC, Otto A, Voit T, Muntoni F, Vrbóva G, Partridge T, Zammit P, Bunger L, Patel K. Lack of myostatin results in excessive muscle growth but impaired force generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1835–1840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604893104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneyer AL, Wang Q, Sidis Y, Sluss PM. Differential distribution of follistatin isoforms: Application of a new FS315-specific immunoassay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5067–5075. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugino K, Kurosawa N, Nakamura T, Takio K, Shimasaki S, Ling N, Titani K, Sugino H. Molecular heterogeneity of follistatin, an activin-binding protein. Higher affinity of the carboxyl-terminal truncated forms for heparan sulfate proteoglycans on the ovarian granulosa cell. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15579–15587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McPherron AC, Lee SJ. Double muscling in cattle due to mutations in the myostatin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12457–12461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harper SQ, Hauser MA, DelloRusso C, Duan D, Crawford RW, Phelps SF, Harper HA, Robinson AS, Engelhardt JF, Brooks SV, Chamberlain JS. Modular flexibility of dystrophin: Implications for gene therapy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Med. 2002;8:253–261. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abmayr S, Gregorevic P, Allen JM, Chamberlain JS. Phenotypic improvement of dystrophic muscles by rAAV/microdystrophin vectors is augmented by Igf1 codelivery. Mol Ther. 2005;12:441–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Griggs RC, Askanas V, DiMauro S, Engel A, Karpati G, Mendell JR, Rowland LP. Inclusion body myositis and myopathies. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:705–713. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bradley WG, Hudgson P, Larson PF, Papapetropoulos TA, Jenkison M. Structural changes in the early stages of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1972;35:451–455. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.35.4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Badrising UA, Maat-Schieman ML, van Houwelingen JC, van Doorn PA, van Duinen SG, van Engelen BG, Faber CG, Hoogendijk JE, de Jager AE, Koehler PJ, de Visser M, Verschuuren JJ, Wintzen AR. Inclusion body myositis. Clinical features and clinical course of the disease in 64 patients. J Neurol. 2005;252:1448–1454. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0884-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rose MR, McDermott MP, Thornton CA, Palenski C, Martens WB, Griggs RC. A prospective natural history study of inclusion body myositis: Implications for clinical trials. Neurology. 2001;57:548–550. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferrari FK, Xiao X, McCarty D, Samulski RJ. New developments in the generation of Ad-free, high-titer rAAV gene therapy vectors. Nat Med. 1997;3:1295–1297. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foust KD, Nurre E, Montgomery CL, Hernandez A, Chan CM, Kaspar BK. Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clark KR, Liu X, McGrath JP, Johnson PR. Highly purified recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors are biologically active and free of detectable helper and wild-type viruses. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:1031–1039. doi: 10.1089/10430349950018427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.