Abstract

This research investigated the role of children’s implicit theories of peer relationships in their psychological, emotional, and behavioral adjustment. Participants included 206 children (110 girls; 96 boys; M age = 10.13 years, SD = 1.16) who reported on their implicit theories of peer relationships, social goal orientation, need for approval, depressive and aggressive symptoms, and exposure to peer victimization. Parents also provided reports on aggressive symptoms. Results confirmed that holding an entity theory of peer relationships was associated with a greater tendency to endorse performance-oriented social goals and to evaluate oneself negatively in the face of peer disapproval. Moreover, entity theorists were more likely than incremental theorists to demonstrate depressive and aggressive symptoms when victimized. These findings contribute to social-cognitive theories of motivation and personality, and have practical implications for children exposed to peer victimization and associated difficulties.

Keywords: implicit theories, peers, emotional and behavioral adjustment

From early in life, children are required to navigate the complex world of peer relationships. Along the way, they make decisions about with whom they wish to develop and maintain relationships. They also make judgments about their competence and their likelihood of success in these relationships. Whereas some children may believe that maximizing their social competence and building relationships with peers require sustained effort and persistence, others may believe that relationships are destined to either succeed or fail. These perspectives on relationships are likely to play a critical role in children’s adjustment. The goal of the present research was to examine the implications of variability in children’s implicit theories of peer relationships for psychological, emotional, and behavioral well-being.

Implicit Theories of Relationships

According to Dweck and colleagues, people assign meaning and structure to social interactions through the development of lay or implicit theories about themselves and the world (Dweck, 1999; Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Molden & Dweck, 2006). These theories reflect fundamental differences in the extent to which people believe that personal attributes are fixed and unchangeable (entity theories) versus malleable and increasable (incremental theories). Research supports the presence of distinct individual differences in the extent to which people hold entity versus incremental theories of personal attributes (for reviews, see Dweck, 1991; Dweck, 1999; Dweck, Hong, & Chiu, 1993; Dweck & Leggett, 1988), including intelligence (Blackwell, Trzesniewski, & Dweck, 2007; Henderson & Dweck, 1990) and personality (Erdley, Cain, Loomis, Duman-Hines, & Dweck, 1997), as well as of romantic relationships (Franiuk, Cohen, & Pomerantz, 2002; Knee, 1998; Knee, Patrick, & Lonsbary, 2003).

This variability in implicit theories contributes to a constellation of psychological processes (for reviews, see Dweck, 1999; Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Molden & Dweck, 2006). Importantly, theory and research link implicit theories of intelligence and personality to specific patterns of goal orientation and self-evaluative processes. Entity theorists tend to pursue performance-oriented goals that focus on obtaining positive judgments of their competence and avoiding negative judgments of their competence, whereas incremental theorists tend to pursue mastery-oriented goals that focus on learning and developing their competence (Blackwell et al., 2007; Erdley et al., 1997; for reviews, see Dweck, 1999; Dweck & Leggett, 1988). Because entity theorists view attributes as fixed and unchangeable, it is critical for them to prove that they possess desirable attributes. Moreover, evidence that threatens their sense of competence would have particularly negative implications for their self-evaluation. In contrast, because incremental theorists view attributes as malleable, they are more likely to focus on developing desirable attributes and should feel less threatened by others’ evaluations of their competence.

Extending prior theory and research, this study explored variability in children’s implicit theories of peer relationships. It was expected that children would differ in the extent to which they viewed social competence and the quality of peer relationships as static characteristics or as dynamic characteristics that can develop over time. Specifically, entity theorists may hold the belief that children are endowed with either desirable or undesirable social attributes, causing them to be either accepted or disliked by their peers, and that children are destined to have either positive or negative relationships, with little opportunity for change. In contrast, incremental theorists may hold the belief that children can become more accepted by peers and that, through effort, children can improve their peer relationships over time.

More specifically, this study examined the idea that these differing perspectives on peer relationships have implications for children’s social goal orientation and self-appraisals in the context of peer relationships. With regard to social goal orientation, it was hypothesized that entity relative to incremental theories would be associated with a greater tendency to endorse performance-oriented social goals, which focus on demonstrating social competence, and a lesser tendency to endorse mastery-oriented social goals, which focus on developing social competence. Consistent with work by Dweck and colleagues (Erdley et al., 1997), a distinction was made between high-risk and low-risk performance goals. High-risk performance goals involve obtaining social approval but are difficult to achieve; if achieved, a child gains status in the peer group (e.g., impressing peers, proving one’s popularity). Low-risk performance goals involve minimizing the risk for social failure (e.g., interacting with someone with whom one is sure to succeed). Children with entity theories may place high priority on both high- and low-risk performance goals. Pursuing high-risk performance goals maximizes children’s likelihood of proving their social competence, which is critical for children who believe that social competence is a fixed quality. Pursuing low-risk performance goals minimizes children’s likelihood of receiving negative feedback that would provide evidence of one’s lack of competence. However, children with entity theories are unlikely to pursue mastery goals as they believe that social competence and the quality of peer relationships are fixed characteristics with little room for development.

With regard to self-evaluation implicit theories were expected to predict children’s tendency to base their self-appraisals on the judgments of peers. Prior research documents individual differences in children’s need for approval from peers (Rudolph, Caldwell, & Conley, 2005). This need for approval is reflected in two dimensions: positive approval-based self-appraisals (a tendency toward enhanced self-worth, such as feeling proud of oneself or feeling like a good person, in the face of social approval) and negative approval-based self-appraisals (a tendency toward diminished self-worth, such as feeling ashamed of oneself or feeling like a bad person, in the face of social disapproval). It was predicted that children with entity relative to incremental theories of peer relationships would show a greater need for approval. Because these children view social competence and peer relationships as fixed qualities, positive feedback should bolster their sense of worth but negative feedback should threaten their sense of worth. In contrast, children with incremental relative to entity theories of peer relationships should view feedback—either positive or negative—as less reflective of their core self-worth; rather, this feedback merely provides an opportunity for growth in social skills or relationship-building.

Role of Implicit Theories of Relationships in Responses to Social Challenge

Dweck and colleagues (Erdley et al. 1997; Molden & Dweck, 2006) further suggest that implicit theories are likely to influence how people interpret and respond to challenges or setbacks in their lives. Accordingly, implicit theories of peer relationships may determine whether social challenges (e.g., peer rejection, conflict) are debilitating and undermine children’s well-being or whether children are able to maintain optimal functioning despite social challenges. Children with entity theories likely feel more threatened by social challenges than those with incremental theories. If children believe that social competence and the quality of peer relationships are static and unchangeable, peer problems would signify that they permanently lack desirable social attributes and that they are destined to experience poor relationships with peers. Thus, it was expected that these children would be susceptible to adjustment difficulties in the face of social challenge. In contrast, if children believe that social competence and the quality of peer relationships can be cultivated over time, peer problems would merely signify the need for increased effort toward improvement. Thus, these children would cope more effectively with challenge, thereby protecting them from adjustment difficulties.

Indeed, research supports the idea that implicit theories guide emotional and behavioral responses to setbacks and social challenges. Adults with entity theories of romantic relationships show more avoidant, passive, or hostile responses to conflict whereas those with incremental theories of romantic relationships show improvement-oriented strategies in the face of disagreements (Franiuk et al., 2002; Knee et al., 2003). Entity theorists also are more likely than incremental theorists to end a dissatisfying relationship (Franiuk et al., 2002; Knee, 1998). Moreover, college students with entity theories show greater vulnerability to dysphoria, and less effective coping once they experience dysphoria, than those with incremental theories (Baer, Grant, & Dweck, 2005). In children, entity theorists (particularly those with low levels of confidence) make more negative self-attributions and show more helpless responses to social failure than do incremental theorists (Erdley et al., 1997). Holding an entity theory of personality also increases children’s tendency to make global negative judgments about others and to recommend punishment for others who commit transgressions (Erdley & Dweck, 1993). Thus, entity theorists are more inclined toward both negative self-inferences and dysphoria, as well as negative inferences about others and hostility, in the face of challenge.

Building on this research, the present study investigated whether holding an entity relative to incremental theory of peer relationships amplified emotional difficulties (depressive symptoms) and behavioral difficulties (aggressive symptoms) in the context of social challenge. Specifically, this study examined whether implicit theories moderated the link between peer victimization and adjustment difficulties. Research suggests that the majority of children experience some degree of victimization by peers, making it a common and salient social stressor during childhood (Frey et al., 2005; Hoover, Oliver, & Hazler, 1992; Olweus, 1992). Based on general findings regarding the role of implicit theories in guiding responses to challenge (for a review, see Molden & Dweck, 2006), as well as specific findings linking entity theories with both negative self-inferences and dysphoria (Baer et al., 2005; Erdley et al., 1997) and negative other-inferences and hostility (Erdley & Dweck, 1993; Knee et al., 2003), it was anticipated that children with entity relative to incremental theories of relationships would show heightened depressive and aggressive symptoms in the context of peer victimization.

In sum, the present study examined two sets of hypotheses: (a) implicit theories of peer relationships would be linked to children’s social goal orientation and self-appraisals in the context of peer relationships, and (b) implicit theories of peer relationships would moderate the association between exposure to peer victimization and adjustment difficulties (i.e., depressive and aggressive symptoms). These hypotheses were examined during middle to late childhood, a stage during which individual differences in children’s implicit theories have been documented (e.g., Erdley & Dweck, 1993; Erdley et al., 1997), and children’s beliefs about peer relationships have important implications for their adjustment (e.g., Troop-Gordon & Ladd, 2005). Understanding individual differences in children’s orientation toward peer relationships during this developmental stage has critical implications for identifying children at risk for a declining trajectory in relationship functioning across the challenging transition to adolescence. Because girls and boys show differing orientations toward peer relationships (for a review, see Rose & Rudolph, 2006), sex differences in the proposed network of associations were examined.

Method

Participants

Participants were 206 children (110 girls; 96 boys; M age = 10.13 years, SD = 1.16) with informed consent who were recruited from several elementary schools in the Midwestern region of the United States and participant pools of two developmental research projects. The children were primarily White (87.4%), with a few other ethnic groups represented (4.9% African American, 2.4% Asian American, 1.5% Latino/a, .5% Native American, and 3.4% multi-ethnic or other). Families were from diverse economic backgrounds representing a range of income levels: under $30,000 (7.8%), $30-44,999 (20.3%), $45-59,999 (17.7%), $60,000-74,999 (20.8%), $75,000-89,999 (15.1%), and over $90,000 (18.2%).

Procedure

Families who had previously participated in research projects either in the schools or at the University of Illinois were contacted by telephone to assess their interest in participating in the study. If families indicated interest, they were scheduled for a laboratory session. Upon arrival at the session, the study was described in detail to families; parents provided written consent and children provided written assent. Several measures were then administered to the children. Researchers read each question and response option aloud, and children circled their responses. Parents independently completed a measure of aggressive symptoms.

Measures

Table 1 presents descriptive information and intercorrelations among the measures.

Table 1.

Descriptive Data and Intercorrelations Among the Variables

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Implicit Theories of Relationships | 2.56 | .81 | --- | ||||||||

| 2. | High-risk Performance Goals | 3.27 | .98 | .31*** | --- | |||||||

| 3. | Low-risk Performance Goals | 3.66 | .81 | .20** | .47*** | --- | ||||||

| 4. | Mastery Goals | 4.84 | .86 | -.14* | .00 | .01 | --- | |||||

| 5. | Positive Self-Appraisals | 3.72 | .97 | .00 | .14 | -.05 | .30** | --- | ||||

| 6. | Negative Self-Appraisals | 2.02 | 1.01 | .29** | .17 | .04 | -.19+ | .17+ | --- | |||

| 7. | Peer Victimization | 1.98 | .75 | .22** | .14+ | .07 | -.16* | .00 | .48*** | --- | ||

| 8. | Depressive Symptoms | 6.62 | 7.23 | .32*** | .11 | .03 | -.40*** | -.36*** | .46*** | .53*** | --- | |

| 9. | Aggressive Symptoms | .00 | .82 | .10 | .14* | .04 | -.12+ | -.05 | .30** | .38*** | .42*** | --- |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Implicit theories of peer relationships

Children completed the twelve-item Implicit Theories of Peer Relationships Questionnaire, developed for this study to assess children’s beliefs about the nature of peer relationships. This measure was modeled after measures of implicit theories of intelligence and personality (Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Erdley & Dweck, 1993; Erdley et al., 1997; Henderson & Dweck, 1990). Using a similar format and wording, items from prior measures of implicit theories were adapted to assess entity versus incremental theories of peer relationships (e.g., “Kids like you a certain amount and you really cannot do much to change it.” “Either kids get along or they don’t, and nothing they do will change things.”). Children rated how true each item was on a scale of 1 (Not at All) to 5 (Very Much). Consistent with a large body of prior research (e.g., Erdley & Dweck, 1993; Erdley et al., 1997; Henderson & Dweck, 1990), statements were worded as entity theories. Research has shown that most children tend to endorse incremental statements when presented in the context of entity statements because they are socially desirable. When only entity beliefs are presented, children with entity theories will agree with the statements, whereas those with incremental theories indicate their disagreement. Indeed, there is evidence that individuals who disagree with entity statements describe attributes in a manner that is consistent with an incremental theory (see Erdley & Dweck, 1993; Erdley et al., 1997). Scores were calculated as the mean of the 12 items (α = .85).

Consistent with prior research, these scores were used in two ways. Some research measures implicit theories as continuous variables (e.g., Blackwell et al., 2007; Franiuk et al., 2002); thus, one set of analyses was conducted using the mean scores, with higher scores reflecting greater endorsement of an entity theory. Other research measures implicit theories in terms of dichotomous groups (e.g., Erdley & Dweck, 1993; Erdley et al., 1997); thus, a second set of analyses was conducted using a grouping variable. Categorical scores for implicit theories have been calculated in different ways across studies. Some research uses an extreme-group approach. For example, Erdley and Dweck (1993) created one group of children who scored in the top one-third of their sample and a second group of children who scored in the bottom one-third of their sample; children in the middle one-third were omitted from analyses. Other research has grouped individuals into those scoring above and below the mean of the sample (Erdley et al., 1997). Both grouping approaches have advantages: The former yields more distinct groups of entity versus incremental theorists; the latter yields greater power due to inclusion of the entire sample. Thus, categorical analyses were conducted using both approaches. An extreme-group approach resulted in 76 entity theorists and 67 incremental theorists. A mean-split approach resulted in 99 entity theorists and 107 incremental theorists. Entity and incremental theorists did not differ in sex based on either the extreme-group approach, χ2(N = 143, df = 1) = 1.74, ns, or the mean-split approach, χ2(N = 206, df = 1) = 1.17, ns.

Goal orientation

Children completed a questionnaire designed to assess their social goal orientation (Erdley et al., 1997). This measure presents children with five hypothetical, challenging social situations (e.g., talking with a new classmate; deciding whom to invite to a party; finding someone to play with at recess). Five of the original six scenarios were used due to time constraints. Children rated on a scale of 1 (Really Disagree) to 6 (Really Agree) the extent to which they would pursue each of three goals within each situation: (a) mastery goals (α = .80), which involve learning and developing relationships (e.g., talking honestly about what you are like and finding out what the other child is like; inviting the children you would like to get to know better to the party; asking someone to play whom you would like to get to know better), (b) high-risk performance goals (α = .75), which involve proving one’s status in the peer group (e.g., talking about your friends, especially the popular children, to impress the child; inviting the most popular children to the party; asking someone to play with whom everyone wants to play so people know how popular you are), and (c) low-risk performance goals (α = .62), which involve minimizing the risk for social failure or negative social judgment (e.g., talking about anything the new child wants so that the child will be sure to like you; inviting the children to the party whom you are sure will say yes; asking someone to play with whom you have played before, because you know they will say yes). Three scores were calculated as the mean of the ratings for each type of goal across scenarios. Validity of this measure has been established through associations with children’s social confidence and implicit theories of personality; moreover, sex differences in social goals endorsed on this measure are consistent with prior research (Erdley et al., 1997).

Need for approval

Children completed the Need for Approval Questionnaire (Rudolph et al., 2005), which assesses the extent to which children base positive views of the self on peer approval (α = .76; e.g., “When other kids like me, I feel happier about myself.” “Being liked by other kids makes me feel better about myself.”), and the extent to which children base negative views of the self on peer disapproval (α = .83; e.g., “I feel like I am a bad person when other kids don’t like me.” “When other kids don’t like me, I feel embarrassed about myself.”). Each subscale is composed of four items rated on a scale of 1 (Not at All) to 5 (Very Much). Two scores were calculated by computing the mean of the four items for each subscale. Confirmatory factor analyses have revealed that need for approval is a two-dimensional construct (Rudolph et al., 2005). Moreover, both concurrent and discriminant validity of this measure have been established. Specifically, need for approval is associated in the anticipated direction with social-evaluative concerns, and is distinct from global self-worth (Rudolph et al., 2005).1

Peer victimization

Children completed a revised version of the Social Experience Questionnaire (SEQ), a well-validated measure of peer victimization (Crick & Grotpeter, 1996). The original measure includes five items assessing exposure to overt victimization (e.g., “How often do you get hit by another kid?”) and five items assessing exposure to relational victimization (e.g., “How often do other kids leave you out on purpose when it’s time to play or do an activity?”). The measure was extended by adding two items tapping other aspects of overt victimization (e.g., “How often do you get teased by another kid?”) and five items tapping relational victimization specifically in the context of friendships (e.g., “How often does a friend get even with you by spending time with new friends instead of you?” “How often does a friend who is mad at you ignore you or stop talking to you?”), yielding a total of 17 items. Children reported the extent to which they had experienced each type of victimization on a scale of 1 (Never) to 5 (All the Time). Research suggests that self-reports of victimization provide valid information that corresponds to reports by peers (Graham & Juvonen, 1998), teachers (Ladd & Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2002), and parents (Bollmer, Harris, & Milich, 2006) in middle childhood; self-reports of victimization correspond with behavioral observations as early as kindergarten (Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1997). Preliminary analyses included separate indices of overt and relational victimization. Because these types of victimization were strongly correlated (r = .69, p < .001), and analyses revealed highly similar patterns for the two subscales, a single index of peer victimization (α = .93) was computed by calculating the mean of the 17 items, with higher scores reflecting more victimization.

Depressive symptoms

Children completed the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1980/81), one of the most widely used self-report measures of depressive symptoms in youth. The CDI includes 27 items that yield a total score ranging from 0 to 54. For each item, youth endorsed one of three statements that describe no, mild, or severe depressive symptoms. Adequate internal consistency and test-retest reliability have been established (Kovacs, 1980; Smucker, Craighead, Craighead, & Green, 1986). High internal consistency (α = .90) was found in the present sample.

Aggressive symptoms

Children completed the aggression subscale of the Youth Self-Report (Achenbach, 1991b), and parents completed the aggression subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991a). These subscales include 19 and 20 items, respectively, assessing aggressive behaviors (e.g., “I am mean to others.” “I get in many fights.” “I threaten to hurt people.” “I tease others a lot.”). Children and parents rated on a scale of 0 (Not True) to 2 (Very True or Often True) how much each item described their (self-report) or their child’s (parent report) behavior. A total score was calculated as the sum of the ratings across items. Adequate reliability and validity of these measures have been established (Achenbach, 1991a, 1991b). High internal consistency (αs = .84 and .87, respectively) was found in the present sample. A composite score of aggressive symptoms was calculated by standardizing and averaging child and parent reports.

Results

Overview of Analyses

The first set of analyses examined hypotheses concerning the associations among implicit theories of peer relationships, psychological functioning (social goal orientation and need for approval), and emotional and behavioral adjustment (depressive and aggressive symptoms). These associations were examined with correlations for the continuous implicit theories index, and with t-tests for the categorical implicit theories indexes. The second set of analyses examined hypotheses regarding the extent to which implicit theories of peer relationships moderated the link between peer victimization and adjustment difficulties. Each set of analyses initially examined possible sex differences in the correlates of implicit theories of relationships.

Implicit Theories as a Predictor of Psychological and Emotional Functioning

Preliminary analyses revealed no significant Implicit Theories × Sex interactions in the prediction of psychological functioning, emotional adjustment, or behavioral adjustment. Thus, correlations and t-tests were conducted across sex.

Consistent with predictions, entity theories were significantly positively associated with performance-oriented social goals (both high- and low- risk) and were significantly negatively associated with mastery-oriented social goals (see Table 1). Thus, children who viewed their peer relationships as nonmalleable were more likely to focus on impressing their peers and on avoiding negative judgments, and were less likely to focus on developing positive peer relationships. T-test analyses revealed a similar pattern for performance goals, with entity theorists endorsing significantly higher levels than incremental theorists for both the extreme-group approach, |ts|(141) ≥ 2.48, ps < .05, and the mean-split approach, |ts|(204) ≥ 2.19, ps < .05; entity and incremental theorists did not significantly differ in their endorsement of mastery goals for the extreme-group approach, t(141) = 1.24, ns, or for the mean-split approach, t(204) = 1.33, ns.

Also as anticipated, entity theories were significantly positively associated with more negative approval-based self-appraisals; entity theories were not significantly associated with positive approval-based self-appraisals (see Table 1). Thus, children who viewed their peer relationships as nonmalleable were more likely to feel poorly about themselves when they received disapproval from their peers. This association was replicated in the t-test analyses for the extreme-group approach, t(67) = -2.33, p < .05, and for the mean-split approach, t(92) = -2.90, p < .01.

Finally, entity theories were significantly positively associated with depressive but not aggressive symptoms (see Table 1). T-test analyses revealed a similar pattern for depressive symptoms, with entity theorists endorsing significantly higher levels than incremental theorists for both the extreme-group approach, t(141) = -4.17, p < .001, and the mean-split approach, t(204) = -4.21, p < .001. T-test analyses revealed marginal differences for aggressive symptoms, with entity theorists endorsing somewhat higher levels than incremental theorists for both the extreme-group approach, t(141) = -1.67, p < .10, and the mean-split approach, t(204) = -1.96, p = .05.

Implicit Theories as a Predictor of Responses to Victimization

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine the hypothesis that entity theories would amplify emotional and behavioral difficulties in the context of peer victimization. Three sets of analyses were conducted for each outcome (depressive symptoms and aggressive symptoms). The first set used the continuous index of implicit theories, and the second and third sets used the two categorical indexes of implicit theories. For each analysis, the main effects of peer victimization and implicit theories were entered in the first step, and the Peer Victimization × Implicit Theories interaction was entered in the second step. The continuous predictors were mean-centered. Preliminary analyses examined whether sex moderated the Peer Victimization × Implicit Theories interactions. The three-way interaction term was nonsignificant for all three sets of analyses. Table 2 displays the results of the analyses collapsed across sex.

Table 2.

Predicting Depressive and Aggressive Symptoms From Peer Victimization, Implicit Theories of Relationships, and Peer Victimization × Implicit Theories of Relationships Interactions

| Depressive Symptoms | Aggressive Symptoms | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | β | t | ΔR2 | β | t | ΔR2 | |

| Continuous Index | |||||||

| Step 1: Main Effects | .33 | .14 | |||||

| Peer Victimization | .49 | 8.19*** | .37 | 5.54*** | |||

| Implicit Theories | .21 | 3.58*** | .02 | .32 | |||

| Step 2: Interaction | .05 | .01 | |||||

| Peer Victimization × Implicit Theories |

.24 | 4.18*** | .08 | 1.22 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Categorical Index Extreme-Group |

|||||||

| Step 1: Main Effects | .36 | .17 | |||||

| Peer Victimization | .51 | 7.34*** | .40 | 5.10*** | |||

| Implicit Theories | .24 | 3.55*** | .07 | .91 | |||

| Step 2: Interaction | .09 | .03 | |||||

| Peer Victimization × Implicit Theories |

.49 | 4.79*** | .28 | 2.22* | |||

|

| |||||||

| Categorical Index: Mean-Split |

|||||||

| Step 1: Main Effects | .34 | .15 | |||||

| Peer Victimization | .51 | 8.76*** | .36 | 5.57*** | |||

| Implicit Theories | .23 | 3.96*** | .10 | 1.49 | |||

| Step 2: Interaction | .06 | .02 | |||||

| Peer Victimization × Implicit Theories |

.37 | 4.61*** | .20 | 2.18* | |||

Note. Values in the table are statistics from the step of entry in hierarchical multiple regression analyses.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Depressive symptoms

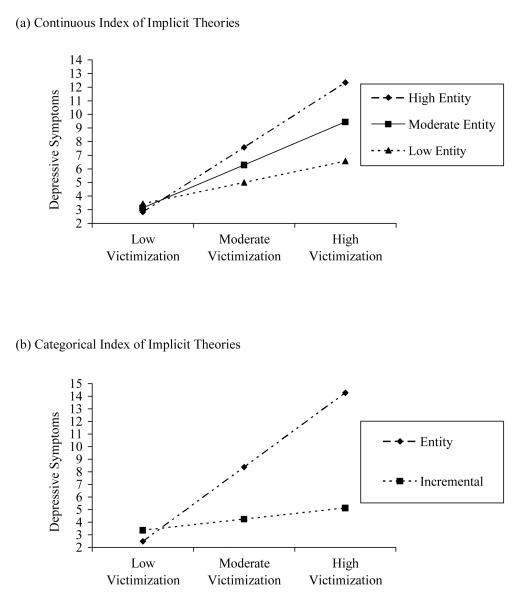

Using the continuous index of implicit theories, the first analysis predicting depressive symptoms revealed significant main effects of peer victimization and implicit theories; these main effects were qualified by a significant Peer Victimization × Implicit Theories interaction. Following Aiken and West (1991), this interaction was interpreted by solving the unstandardized regression equation to predict depressive symptoms from peer victimization at low (-1 SD), moderate (mean), and high (+1 SD) levels of implicit theories. Analysis of the slopes of the lines revealed that victimization was significantly more strongly associated with depressive symptoms in the context of high, β = .66, t(201) = 9.35, p < .001, than low, β = .22, t(201) = 2.51, p < .05, levels of entity theories; victimization was moderately associated with depressive symptoms in the context of moderate levels of entity theories, β = .44, t(201) = 7.51, p < .001 (see Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Victimization × Implicit Theories of Relationships interaction predicting depressive symptoms using (a) a continuous index of implicit theories, and (b) a categorical index of implicit theories.

Using the extreme-group categorical index of implicit theories, the second analysis predicting depressive symptoms revealed significant main effects of peer victimization and implicit theories; these main effects were qualified by a significant Peer Victimization × Implicit Theories interaction. Following Aiken and West (1991), this interaction was interpreted by solving the unstandardized regression equation to predict depressive symptoms from peer victimization for entity theorists and incremental theorists. Analysis of the slopes of the lines revealed that victimization was significantly associated with depressive symptoms for entity theorists, β = .65, t(74) = 7.37, p < .001, but was only marginally associated with depressive symptoms for incremental theorists, β = .21, t(65) = 1.74, p < .10 (see Figure 1b). Using the mean-split categorical index of implicit theories, a very similar pattern of effects was found, although decomposition of the interaction revealed that victimization was significantly associated with depressive symptoms for entity theorists, β = .64, t(96) = 8.11, p < .001, and for incremental theorists, β = .37, t(105) = 4.02, p < .001.

Aggressive symptoms

Using the continuous index of implicit theories, the first analysis predicting aggressive symptoms revealed a significant main effect of peer victimization, a nonsignificant main effect of implicit theories, and a nonsignificant Peer Victimization × Implicit Theories interaction.

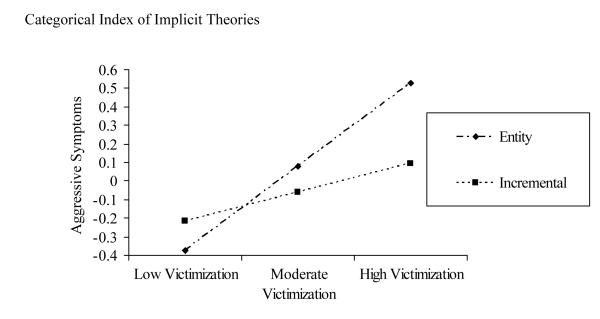

Using the extreme-group categorical index of implicit theories, the second analysis predicting aggressive symptoms revealed a significant main effect of peer victimization, a nonsignificant main effect of implicit theories, and a significant Peer Victimization × Implicit Theories interaction. This interaction was interpreted by solving the unstandardized regression equation to predict aggressive symptoms from peer victimization for entity theorists and incremental theorists. Analysis of the slopes of the lines revealed that victimization was significantly associated with aggressive symptoms for entity theorists, β = .52, t(74) = 5.25, p < .001, but not for incremental theorists, β = .18, t(65) = 1.49, ns (see Figure 2). Using the mean-split categorical index of implicit theories, a very similar pattern of effects was found (see Table 2), although decomposition of the interaction revealed that victimization was significantly associated with aggressive symptoms for entity theorists, β = .47, t(96) = 5.26, p < .001, and for incremental theorists, β = .23, t(105) = 2.47, p < .05.

Figure 2.

Victimization × Implicit Theories of Relationships interaction predicting aggressive symptoms using a categorical index of implicit theories.

Discussion

This study examined the implications of children’s implicit theories of peer relationships for their psychological, emotional, and behavioral adjustment. Consistent with theory and prior research in other domains (Dweck, 1999; Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Molden & Dweck, 2006), the present research suggests that entity theories represent part of a broader orientation toward peer relationships that emphasizes demonstrating one’s competence and being evaluated positively in one’s relationships rather than developing and improving one’s relationships. Moreover, children with entity relative to incremental theories have a greater tendency to demonstrate emotional and behavioral difficulties in the context of social challenge.

Implications of Implicit Theories for Social Goal Orientation and Self-Evaluative Processes

Entity theories were associated with a heightened performance goal orientation and a diminished mastery goal orientation, with particularly robust effects for performance goals. Moreover, entity theorists were more inclined than incremental theorists to demonstrate a strong need for approval from peers. In particular, entity theorists showed a tendency toward diminished self-worth in the face of social disapproval, suggesting that they were likely driven by a motivation to avoid negative judgments from others. This network of associations supports hypotheses derived from Dweck’s social-cognitive perspective on motivation and personality (Dweck, 1999; Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Molden & Dweck, 2006), thus providing construct validity for a newly developed measure of implicit theories of peer relationships and suggesting that this perspective can be applied to understand individual differences in children’s approach to peer relationships.

Children who endorse entity theories of peer relationships have a great deal at stake in the context of social interactions. Because they view social competence and the quality of peer relationships as fixed, proving their competence and avoiding negative judgments from peers is essential for protecting their sense of worth. In contrast, children who endorse incremental theories of peer relationships are better able to devote their psychological resources toward improving their competence and developing positive relationships with peers. Because incremental theorists perceive their social competence and relationship status as dynamic and subject to change, evaluative feedback is less relevant to their self-worth. Rather, this feedback may be viewed as useful for self-improvement and the cultivation of relationships. Interestingly, although entity theorists reported diminished self-worth in the face of disapproval, they did not report enhanced self-worth in the face of approval. Thus, entity theorists seem more sensitive to negative than positive evaluative feedback from peers. Perhaps their self-worth is sufficiently fragile that they are unable to incorporate positive feedback into their self-evaluation; even when they receive such feedback they may still feel the need to further prove their social competence. It is also possible that entity theorists actually receive more negative than positive feedback from peers either because they act in ways that elicit such feedback or because their entity theories stem, in part, from poor treatment from peers. Thus, positive feedback may be less relevant to them than negative feedback. Indeed, given evidence that holding an entity theory predicts more helpless responses to social challenge (Erdley et al., 1997), one might expect that children who endorse these theories would experience more difficulties with peers. In the present study, entity theories of relationships were moderately associated with peer victimization, suggesting a possible link between these theories and peer difficulties. Future research needs to further investigate the actual social competence and status of entity versus incremental theorists to determine the feasibility of these alternative explanations.

Implications of Implicit Theories for Emotional and Behavioral Adjustment

A major premise of Dweck’s social-cognitive theory of motivation and personality (Dweck, 1999; Dweck & Leggett, 1988) is that implicit theories guide individuals’ responses to setback and failure. Supporting this premise, this study revealed that the link between peer victimization and adjustment difficulties was amplified in children who endorsed entity theories but tempered in children who endorsed incremental theories. This finding is consistent with the idea that implicit theories contribute to individual variability in the subjective interpretation of social challenge. Entity theorists are likely to interpret peer victimization as evidence that they lack desirable social attributes and that their relationships with peers are doomed to failure. This interpretation both may create substantial emotional distress, resulting in depressive symptoms, and may intensify feelings of animosity toward peers, resulting in aggressive symptoms. Incremental theorists, on the other hand, may try to understand the reasons for negative treatment from peers in an effort to build their skills and improve their relationships. As a result, they are buffered from the negative emotions and behavior associated with peer victimization. In fact, when analyses were conducted using an extreme-group approach, which provided the strongest differentiation between entity and incremental theorists, victimization was not significantly associated with either depressive or aggressive symptoms in incremental theorists.

Notably, stronger and more consistent links were found between implicit theories and depressive than aggressive symptoms, suggesting that these theories may be particularly relevant for understanding negative emotions that involve feelings of low self-worth and incompetence rather than feelings of hostility toward others. It will be important for future research to identify personal characteristics or environmental conditions that determine when entity theorists are more susceptible to depressive versus aggressive symptoms. Moreover, the present research focused on overt types of aggression, such as fighting, destruction of property, and teasing. It is possible that implicit theories of peer relationships play an even larger role in relational aggression, such as social manipulation and exclusion; it would be helpful for future research to consider both types of aggression.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study supports the important role of implicit theories of peer relationships in children’s well-being, some caveats deserve mention. Most importantly, this research examined concurrent links between implicit theories and adjustment, thereby precluding conclusions about the direction of effects. Our interpretation is consistent with research using experimental manipulation of implicit theories (Baer et al., 2005) and social failure (Erdley et al., 1997), as well as with research using longitudinal designs (Blackwell et al., 2007; Franiuk et al., 2002), which suggests that implicit theories predict subsequent self-regulatory processes, responses to failure, and relationship adjustment. However, as noted earlier, it is possible that successive social failures or poor treatment by peers also lead children to adopt entity theories of relationships. Also, because many of the constructs involved subjective beliefs and experiences, the present study relied primarily on children’s self-reports, with the exception of parent reports of aggression. The observed pattern of moderation effects is unlikely due to shared method variance given that some children self-reported quite high levels of victimization but low levels of symptoms when they endorsed incremental theories. However, building on this research will require integrating alternate forms of assessment, such as observations of behavior, as well as experimental manipulation of implicit theories and exposure to positive versus negative evaluative feedback. Finally, the sample was relatively homogeneous in ethnicity, although heterogeneous in socioeconomic class. Research is needed to examine whether implicit theories of relationships have similar implications for adjustment across ethnic groups.

Conceptually, this research raises questions about the structure of implicit theories of peer relationships. Prior research has been equivocal regarding whether entity versus incremental theories in other domains represent qualitatively distinct constructs or opposite ends of a dimensional continuum. Whereas early research tended to operationalize these theories in categorical terms, more recent research often views these theories along a continuum. In the present study, continuous and categorical approaches to analysis tended to yield similar results, with a few exceptions. Most notably, categorical but not continuous analyses yielded significant associations between implicit theories and aggressive symptoms. Although research demonstrates that children who endorse low levels of entity theories tend to describe attributes in ways that are consistent with incremental theories (see Erdley & Dweck, 1993; Erdley et al., 1997), research using taxometric analyses is needed to specifically address this question.

Conclusions and Practical Implications

The present research suggests that implicit theories of peer relationships provide a useful framework for understanding children’s goal orientation and self-evaluation in social contexts, as well as their emotional and behavioral adjustment and responses to victimization. Given the potential wide-ranging effects of these theories, they may represent a useful target for prevention and intervention efforts with children experiencing peer difficulties. Although a primary aim of many school-based programs is to create climates that foster positive peer relationships and prevent bullying, efforts also need to be directed toward lessening the adverse impact of stressful peer experiences on children. The present findings suggest that orienting children toward a view of social competence as malleable and peer relationships as changeable may increase children’s focus on skill-building and relationship-improvement, and decrease their focus on self-evaluation, self-enhancement, and competition.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the children who contributed their time to participate in this study. I also thank Melissa Caldwell, Alyssa Clark, Alison Dupre, Megan Flynn, and Kathryn Kurlakowsky for their assistance in data collection and management. This research was supported by a James McKeen Cattell Sabbatical Award, a University of Illinois Center for Advanced Studies Award, a University of Illinois Arnold O. Beckman Award, and National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH59711 awarded to Karen D. Rudolph.

Footnotes

Because this measure was added when the study was partially complete, it is available on only 94 children.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Baer AR, Grant H, Dweck CS. Personal goals, dysphoria, and coping strategies. Columbia University; 2005. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell LS, Trzesniewski KH, Dweck CS. Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development. 2007;78:246–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollmer JM, Harris MJ, Milich R. Reactions to bullying and peer victimization: Narratives, physiological arousal, and personality. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:803–828. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Children’s treatment by peers: Victims of relational and overt aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:367–380. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck CS. Self-theories and goals: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. In: Dienstbier R, editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln: 1991. pp. 199–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dweck CS. Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press; New York, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck CS, Hong Y, Chiu C. Implicit theories: Individual differences in the likelihood and meaning of dispositional inference. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1993;19:644–656. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck CS, Leggett EL. A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review. 1988;95:256–273. [Google Scholar]

- Erdley CA, Cain KM, Loomis CC, Dumas-Hines FH, Dweck CS. Relations among children’s social goals, implicit personality theories, and responses to social failure. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:263–272. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdley CA, Dweck CS. Children’s implicit personality theories as predictors of their social judgments. Child Development. 1993;64:863–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franuik R, Cohen D, Pomerantz EM. Implicit theories of relationships: Implications for relationship satisfaction and longevity. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:345–367. [Google Scholar]

- Frey KS, Hirschstein MK, Snell JL, Edstrom LVS, MacKenzie EP, Broderick CJ. Reducing playground bullying and supporting beliefs: An experimental trial of the Steps to Respect program. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:479–491. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Juvonen J. Self-blame and peer victimization in middle school: An attributional analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:538–587. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson VL, Dweck CS. Motivation and achievement. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1990. pp. 308–329. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover JH, Oliver R, Hazler RJ. Bullying: Perceptions of adolescent victims in the Midwestern USA. School Psychology International. 1992;13:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Knee CR. Implicit theories of relationships: Assessment and prediction of romantic relationship initiation, coping, and longevity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:360–370. [Google Scholar]

- Knee CR, Patrick H, Lonsbary C. Implicit theories of relationships: Orientations toward evaluation and cultivation. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2003;7:41–55. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0701_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer BJ, Ladd GW. Victimized children’s responses to peers’ aggression: Behaviors associated with reduced versus continued victimization. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:59–73. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school-aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatry. 1980;46:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Kochenderfer-Ladd B. Identifying victims of peer aggression from early to middle childhood: Analysis of cross-informant data for concordance, estimation of relational adjustment, prevalence of victimization, and characteristics of identified victims. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:74–96. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molden DC, Dweck CS. Finding “meaning” in psychology: A lay theories approach to self-regulation, social perception, and social development. American Psychologist. 2006;61:192–203. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Victimization among school children: Intervention and prevention. In: Albee GW, Bond LA, Monsey TVC, editors. Improving children’s lives: Global perspectives on prevention. Primary prevention of psychopathology. Vol. 14. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1992. pp. 279–295. [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Caldwell MS, Conley CS. Need for approval and children’s well-being. Child Development. 2005;76:309–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00847_a.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smucker MR, Craighead WE, Craighead LW, Green BJ. Normative and reliability data for the Children’s Depression Inventory. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1986;14:25–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00917219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troop-Gordon W, Ladd GW. Trajectories of peer victimization and perceptions of the self and schoolmates: Precursors to internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Development. 2005;76:1072–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]