Abstract

Aurora kinases are mitotic enzymes involved in centrosome maturation and separation, spindle assembly and stability, and chromosome condensation, segregation, and cytokinesis and represent well known targets for cancer therapy because their deregulation has been linked to tumorigenesis. The availability of suitable markers is of crucial importance to investigate the functions of Auroras and monitor kinase inhibition in in vivo models and in clinical trials. Extending the knowledge on Aurora substrates could help to better understand their biology and could be a source for clinical biomarkers. Using biochemical, mass spectrometric, and cellular approaches, we identified MYBBP1A as a novel Aurora B substrate and serine 1303 as the major phosphorylation site. MYBBP1A is phosphorylated in nocodazole-arrested cells and is dephosphorylated upon Aurora B silencing or by treatment with Danusertib, a small molecule inhibitor of Aurora kinases. Furthermore, we show that MYBBP1A depletion by RNA interference causes mitotic progression delay and spindle assembly defects. MYBBP1A has until now been described as a nucleolar protein, mainly involved in transcriptional regulation. The results presented herein show MYBBP1A as a novel Aurora B kinase substrate and reveal a not yet recognized link of this nucleolar protein to mitosis.

Keywords: Cancer, Cell/Mitosis, Enzymes/Kinase, Phosphorylation/Kinases/Serine-Threonine, Proteomics, Subcellular Organelles/Nucleolus

Introduction

Aurora A, B, and C are the three mammalian members of the Aurora Ser/Thr kinase family. Aurora kinases are involved in multiple functions in mitosis, including centrosome separation and maturation; spindle assembly and stability; chromosome condensation, congression, and segregation; and cytokinesis. They possess a conserved catalytic domain, whereas their N-terminal domain varies, contributing to different localization of the kinase within the cell (1, 2). Although Aurora C is mainly expressed in meiotically dividing cells, both Aurora A and B are widely present in all proliferating tissues, and their expression is cell cycle-regulated, peaking at G2/M phase of the cell cycle. Expression of Aurora kinases has been found to be elevated in a number of diverse human cancers, and their overexpression can cause chromosome number instability and cellular transformation (3, 4). Thus, Aurora kinases represent attractive targets for anti-cancer drug development. Indeed, small molecule inhibitors have been developed and are currently being tested in clinical trials (5, 6). The identification of mechanism of action-related biomarkers and the discovery of new substrates is of crucial importance not only to better characterize the cellular role of the Aurora kinases but also to provide a clear readout of the in vivo activity of compounds. Aurora kinases have already been shown to phosphorylate a number of different substrates. Specifically, Aurora A phosphorylates TPX2, LIM protein, CDC25B, p53, BRCA1, ASAP, and others (7–13), whereas Aurora B phosphorylates histone H3, MCAK, histone H2A, topoisomerase II, INCENP, survivin, and CENP-A (14–20).

Together with INCENP, survivin, and Borealin, Aurora B is a component of the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC)3 (21, 22). In early mitosis, the CPC promotes correct chromosome alignment and is responsible for the displacement of HP-1 from mitotic chromosomes by modifying histone H3, whereas at the end of mitosis, CPC regulates proper completion of cytokinesis (23, 24). The non-enzymatic components of this complex control the targeting, enzymatic activity, and stability of Aurora B kinase (25–28), and although the major role of CPC is in mitosis, its components are already expressed earlier in the cell cycle, when different complexes of chromosomal passenger proteins may exist (29). Recently, for example, Aurora B, INCENP, and Borealin, but not survivin, have been reported to be components of the nucleolar proteome (30). Aurora B may also play a role in the nucleolar cycle because it regulates the RNA-methyltransferase activity of NSUN2, a protein involved in nucleolar architecture and nucleic acid metabolism during mitosis (31).

Here we report the identification of a novel in vivo Aurora B substrate, MYBBP1A (Myb-binding protein 1A) (32). MYBBP1A was originally identified as a protein interacting with the leucine zipper of c-Myb (33). This protein has been reported to bind to a number of transcription factors, including the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor, PGC-1α, NF-κB, and Prep1, and to regulate their activity (34–37).

MYBBP1A is ubiquitously expressed and is a nuclear protein mainly localized to the nucleolus. It shares some homology with a yeast protein called POL5, reported to be an essential DNA polymerase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (38). POL5 localizes to the nucleolus, where it binds near the enhancer region of ribosomal RNA-encoding DNA repeating units; indeed, pol5 mutants indicate that it is involved in ribosomal RNA synthesis in the nucleolus rather than in chromosomal DNA replication (39). Despite the homology with POL5, a role for MYBBP1A in the nucleolus has not yet been described.

Here we show a new role of MYBBP1A in mitosis. It is an in vitro and in vivo substrate for Aurora B, and we have identified the Aurora B-dependent phosphorylation site on MYBBP1A as Ser1303, which falls in a consensus sequence for Aurora kinases. This phosphorylation event is modulated in cells both by RNAi against Aurora B and by treatment with Danusertib (previously known as PHA-739358), a small molecule inhibitor of Aurora kinases presently under clinical development. Furthermore, we have shown that MYBBP1A depletion leads to prolongation of mitosis and mitotic spindle defects, suggesting an essential role of MYBBP1A in the normal progression of mitosis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Sample Preparation

Radioimmune precipitation buffer (150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mm Hepes, pH 7.9) was used to extract proteins from cytoplasmic and nuclear pellets of asynchronous HeLa cells purchased from CILBiotech. The cytoplasmic and nuclear pellets were resuspended in cold radioimmune precipitation buffer, gently agitated at 4 °C for 45 min, and then centrifuged at 15,000 × g to separate cellular debris and aliquoted for use in further experiments. The insoluble nuclear radioimmune precipitation fraction (DNA-bound) was resuspended in buffer containing 50 mm Hepes, pH 7.9, 2% SDS, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 10 units/ml benzonase. After resuspension, the solution was sonicated on ice four times for 10 s each to break DNA and then centrifuged at 25,500 × g for 10 min in a refrigerated centrifuge to remove debris, and the supernatant was aliquoted and frozen in a bath of ethanol and dry ice. In this way, the DNA-bound proteins, such as histones, were extracted.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

To in vitro phosphorylate cytoplasmic or nuclear fractions, 1 μg/μl protein extract was used with 0.2 pmol/μl of Aurora A kinase in a buffer containing 50 mm Hepes, pH 7, 60 mm NaCl, 4% glycerol, 1 mm ATP, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, protease, and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). The reaction took place at 30 °C for 30 min, and the samples were used for electrophoresis and Western blot analysis soon afterward.

To in vitro phosphorylate recombinant MYBBP1A, Aurora A or Aurora B (150 nm) was used in a kinase buffer containing 50 mm Hepes, pH 7, 10 mm MgCl2, 0.2 μg/μl bovine serum albumin, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 25 nm [32P]ATP phosphatase, and protease inhibitors; the reaction took place at 30 °C for 30 min. In order to render the reaction specific, a low concentration of radiolabeled ATP was used, following the Kestrel approach (40).

Ion Exchange Fractionation

The asynchronous HeLa nuclear extract was dialyzed against 50 mm MES, pH 6.5. A monoS column was pre-equilibrated in the presence of 50 mm MES, pH 6.5, and the nuclear extract was loaded onto the resin using AKTA Explorer. The unbound fraction was collected. After the loading, four elution steps at different NaCl concentrations (0.1, 0.3, 0.5, and 1 m) were performed, and the eluting proteins were collected. The unbound fraction and the 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, and 1 m fractions were then dialyzed against the same buffer (kinase buffer, excluding ATP and MgCl2) and concentrated for use in further experiments.

Cloning and Expression

The cDNA of MYBBP1A was purchased from Geneservice, and the coding sequence was cloned using the Gateway® system (Invitrogen) into pGEX2Tg. BL21CodonPlus Escherichia coli cells were used to express the protein (induction with 0.2 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, 21 °C overnight). The recombinant protein was then purified on GSH-Sepharose, and on-column cleavage with PreScission protease was performed. For the overexpression in mammalian cells, MYBBP1A coding sequence was cloned into the mammalian expression vector PCMV-Tag2A FLAG vector (Stratagene) in EcoRI-XhoI sites. Mutagenesis was performed with the Stratagene QuikChange mutagenesis kit.

Cellular Lysis and Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in SDS buffer (125 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS) and after sonication and boiling, total extracts of the indicated samples were loaded on SDS-PAGE precast gels (Invitrogen) or on 3–8% Tris-acetate gels and immunoblotted.

The following antibodies have been used: anti-MYBBP1A (Zymed Laboratories Inc.); anti-BAF155 and anti-CDK2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA)); anti-FLAG (Sigma); anti-phosphohistone H3 Ser10 (Millipore); anti-Aurora A, anti-Aurora B, anti-cyclin B1, and anti-MCM2 (BD Biosciences); and anti-histone H3 (Abcam). Anti-phospho-MYBBP1A, here called anti-P-p160, was produced by Zymed Laboratories Inc., immunizing rabbits using the peptide KENRESLVVN. Immunoreactive signals were detected with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce).

Flow Cytometry

For fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis, cells were harvested, resuspended in cold PBS, fixed with cold (−20 °C) 70% ethanol in PBS, and stored at 4 °C for at least 1 h. Cells were then stained with propidium iodide (25 μg/ml) in PBS containing 50 μg/ml RNase A. The DNA content was analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Cell Culture and Treatments

HeLa and U2OS cells (ECACC) were grown in E-MEM medium. Medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mm l-glutamine, and cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator in the presence of 5% CO2. U2OS-YFP-α-tubulin cells were transfected with a YFP-α-tubulin-overexpressing vector (Clontech) and selected in G418 (400 μg/ml). For experiments involving overexpression of MYBBP1A or the Ser1303 mutants, HeLa cells were transiently transfected for 24 h with 5 μg of the different constructs using Lipofectamine-2000 reagent (Invitrogen).

Calyculin A (Sigma) was added 30 min before cellular lysis at 10 nm. For shake-off experiments, nocodazole (75 ng/ml) or taxol (0.5 μm) was added to the cells for 18 h, and then mitotic cells were harvested by shake-off and treated in the presence of the mitotic inhibitors with DMSO or Danusertib (PHA-739358) (1 μm) together with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 μm).

λ-Phosphatase (New England Biolabs) (400 units) was used directly on cellular lysates (40 μg) for 1 h at 30 °C. RNAi experiments were performed with Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) for 72 h. Different oligonucleotides were used: MYBBP1A (DHARMACON smart pool (M-020341-00-0010)), BAF155-oligo1 (ggatgctcctaccaataaa), BAF155-oligo2 (ttacggatgagaagtcaaa), Aurora A (gcacaaaagcttgtcctta), Aurora B (cgcggcacttcacaattga), Aurora C (gatgtgaggtttccactat), MCM2 oligo-A (ctgaccgatgaagatgtga), and MCM2 oligo-B (gggtgctcagatcaacatc). As a negative control, an oligonucleotide targeting the luciferase gene was used: Luc (cgtacgcggaatacttcga). All oligonucleotides were used at 80 nm.

In-gel Tryptic Digestion

Protein digestion was performed with trypsin (Fluka) using the Digest Pro system (Intavis, Koeln, Germany), following the standard protocol. The elution mixture was then dried down in a speed vacuum and redissolved in 50% acetonitrile, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid for matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) MS analysis or in deionized water for nano-LC MS/MS analysis.

MALDI MS

Samples for MALDI-time-of-flight (TOF) analysis were prepared by spotting 0.5 μl of peptide mixture with 0.5 μl of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (10 mg/ml in 50:50 acetonitrile/water containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) and analyzed on a Voyager DE-PRO mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK). All spectra were collected in reflector mode using four peptides of known mass as external calibration standards.

Nano-HPLC-ESI-MS/MS

Nano-LC MS/MS was performed with a low flow rate reverse phase high pressure liquid chromatograph equipped with a nano-flow splitter (Ultimate, Dionex-LC Packings) coupled on-line to a hybrid quadrupole-time of flight instrument (Q-Tof2, Micromass) equipped with a Z-spray source. Samples were injected onto a C18 precolumn (PepMap 0.3 × 5 mm, LC Packings) and preconcentrated and desalted with mobile phase A (95:5 water/acetonitrile (v/v), 0.05% formic acid). The separation of the peptides was then performed on a 75-μm inner diameter × 150-mm PepMap column (LC Packings) with a gradient from 5 to 60% mobile phase B (5:95 water/acetonitrile (v/v), 0.06% formic acid) in 58 min, followed by a washing step at 60% B in 15 min at a flow rate of 0.2 μl/min. The MS acquisition was performed in survey scan mode, where the Q-Tof selected doubly, triply, and quadruply charged ions above an intensity threshold of 10 counts/s for MS/MS analysis from each survey scan (automatic function switching). The instrument performed the MS/MS analysis under user-defined parameters of collision energy.

For the subsequent protein identification, the .raw data files were converted into .pkl files that were matched in MASCOT searches of the NCBInr data base for mammalian sequences. Protein identifications were confirmed by manual MS/MS data analysis for at least one peptide per protein.

Time Lapse

U2OS cells stably overexpressing YFP-α-tubulin were seeded in a 12-well plate. Images of cells were taken every 30 min using a time lapse microscope (Cell Observer Zeiss) with a ×32 objective equipped with a motorized stage (Zeiss). Images were collected using Axio Vision software (Zeiss).

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed 24 h after transfection with 4% formaldehyde. After permeabilization in PBS 1× containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min, staining was performed by incubating cells with an anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) diluted 1:2000 in PBS 1× containing 2% bovine serum albumin. After 1 h, slides were rinsed in PBS 1× and exposed to CY3 secondary antibody 1:500 (Amersham Biosciences). DNA was visualized with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1:1000). Images were acquired with an Axiovert 100 microscope (Zeiss) with a ×60 objective.

RESULTS

A Kinase Substrate Search Identifies a 160-kDa Protein as a New Aurora Substrate

In order to identify new substrates of Aurora kinases suitable for biomarker discovery, an in vitro kinase substrate search was performed. Aurora A was tested against a panel of proteins containing the reported Aurora consensus phosphorylation site (41), and it was shown to phosphorylate serine 220 of MCM2 (minichromosome maintenance 2),4 which in fact resides in a consensus motif for Aurora kinases (KENRESLVVN). MCM2 is required for replication origin activation along with other MCM partners and with members of the prereplication complex, including origin recognition complex, Cdc6 (cell division cycle 6), and Cdt1 (chromatin licensing and DNA replication factor 1) (42), and it has not previously been identified as an Aurora substrate either in vitro or in vivo. Therefore, we decided to raise a phospho-specific antibody against MCM2 Ser220 to investigate the existence of this phosphorylation event in vivo. As shown in Fig. 1A, the phospho-Ser220 MCM2 antibody indeed detects a single band specifically in extracts from nocodazole-treated mitotic HeLa cell and not from asynchronous cells. However, in contrast with the expected molecular mass of MCM2 (110–120 kDa), the detected band was at 160 kDa with no other bands visible even after prolonged exposure (data not shown). These results indicate that the anti-phospho-Ser220 MCM2 antibody indeed recognizes a band in cell lysates although at a molecular weight different from the expected one and that this signal peaks upon nocodazole treatment. To explain this difference in molecular mass, we hypothesized that 1) some heavy post-translational modification was increasing the molecular mass of MCM2 or altering its electrophoretic mobility or 2) the antibody raised against the phosphorylation site Ser220 MCM2 was cross-reacting with some other unrecognized protein. To rule out the second hypothesis, we performed RNAi experiments against MCM2, followed by nocodazole treatment and Western blot analysis using total-MCM2 and phospho-MCM2 antibodies. As shown in Fig. 1B, despite the complete silencing of MCM2 obtained with two different small interfering RNA oligonucleotides (oligo-A and oligo-B), the antibody against phospho-Ser220 MCM2 still detected a band at 160 kDa in lysates from nocodazole-arrested cells. This indicates that the phospho-MCM2 antibody is cross-reacting in cellular protein extracts with a protein different from MCM2. Therefore, we tried to determine if this protein (that we denoted p160) was an in vivo substrate for Aurora.

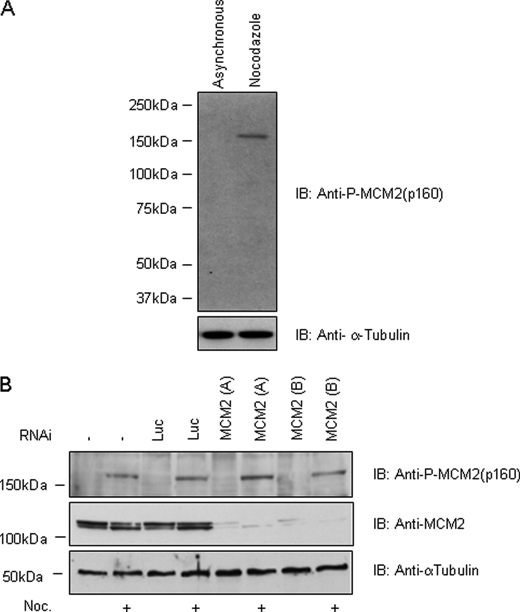

FIGURE 1.

Anti-phospho-MCM2 antibody detects a 160-kDa protein in nocodazole extracts independently of MCM2 presence. A, asynchronous and nocodazole-treated (75 ng/ml) HeLa cell lysates were loaded in a 4–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and then immunoblotted (IB) with anti-phospho-MCM2 antibody. A 160-kDa band was detected only in lysates from nocodazole-treated cells. α-Tubulin antibody was used as a loading control. B, MCM2 RNAi does not abrogate p160 signal. HeLa cells were transfected with two different RNAi oligonucleotides specific for MCM2 (MCM2(A) and MCM2(B)), and, as negative controls, cells were treated with an oligonucleotide specific for the luciferase gene (Luc) or with transfection reagent alone for 66 h. Nocodazole (Noc.; 75 ng/ml) was added for the last 14 h, and total lysates were probed with total MCM2, anti-phospho-MCM2 (p160), and α-tubulin antibodies.

Identification of p160 as MYBBP1A

The first step in the identification process was to check if p160 was also present in asynchronous cell extract and, if so, to verify if this could be phosphorylated in vitro using Aurora kinases, yielding a phospho-p160 signal. This would allow us to work with protein extracts from asynchronous cells, which are more manageable than nocodazole-treated cell extracts and easier to obtain in large amounts. HeLa cytoplasmic, nuclear, and DNA-bound protein extracts were prepared from asynchronous cells, heated at 60 °C for 10 min to inactivate endogenous kinases, and used in an in vitro kinase assay using Aurora A kinase (43). The presence of phospho-p160 was assessed by Western blot analysis. As a positive control, an extract from nocodazole-arrested HeLa cells was included. As shown in Fig. 2A, phospho-p160 was detected only in the nuclear fraction after phosphorylation with Aurora A kinase, indicating that p160 is a predominantly nuclear protein. Both in the cytoplasmic and in the nuclear fraction, a band at 120 kDa was visible after in vitro phosphorylation. This band may correspond to MCM2, suggesting that under these in vitro conditions, the antibody is also able to recognize phospho-Ser220 MCM2. Given that it was possible to follow p160 presence by in vitro phosphorylation of asynchronous cell extracts and Western blot analysis with the phospho-Ser220 MCM2 antibody, hereafter denoted phospho-p160, we decided to fractionate the HeLa nuclear extract using monoS ion exchange chromatography in order to enrich a fraction with p160 and try to isolate it. Binding of the nuclear extract to monoS resin was performed at pH 6.5 in MES buffer in the absence of salt. Elution was performed in a stepwise mode, and five different fractions were collected, corresponding to the unbound, 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, and 1 m NaCl elution steps. All of these fractions were dialyzed against the same final buffer, concentrated as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and then used in an in vitro kinase assay. Following in vitro phosphorylation with Aurora kinase, the phospho-p160 signal was only detected in the 1 m NaCl fraction (Fig. 2B).

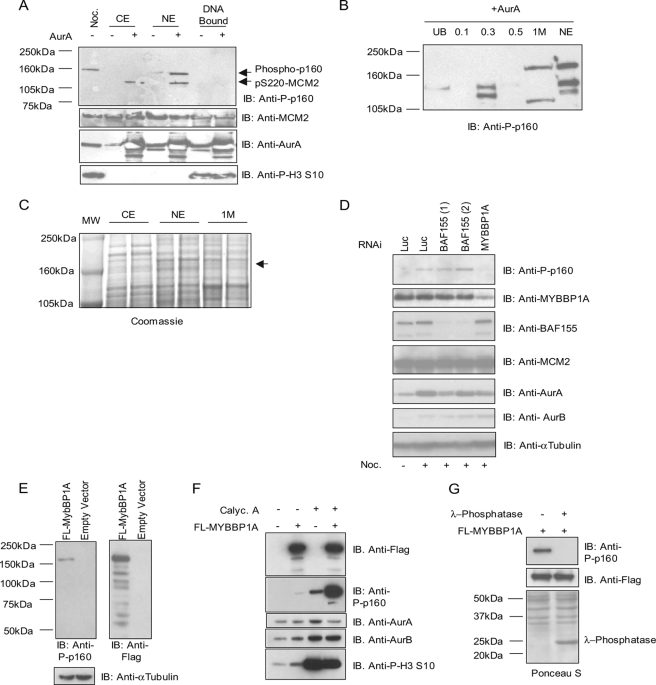

FIGURE 2.

Identification of p160 as MYBBP1A. A, Aurora A phosphorylates p160 in nuclear extracts. Asynchronous HeLa cytoplasmic (CE), nuclear (NE), and DNA-bound cellular extracts were incubated with Aurora A in a kinase assay. As a control, a sample from nocodazole (Noc.)-treated HeLa cells was loaded. To verify the presence of Aurora A and MCM2, immunoblotting (IB) with anti-Aurora A and MCM2 antibodies was performed and also with anti-phosphohistone H3 Ser10 antibody to verify the quality of the DNA-bound extract. B, p160 signal appears only in the 1 m NaCl elution fraction of HeLa nuclear extracts. After fractionation and elution with different salt concentrations, unbound (UB) or 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, or 1 m NaCl elution fractions were incubated with Aurora A kinase, and the p160 signal was followed with anti-phospho-p160 antibody. As a control, unfractionated nuclear extract phosphorylated with Aurora A kinase was included. C, Coomassie Blue staining of cytoplasmic, nuclear, and 1 m NaCl (1 m) fraction. p160 protein is indicated. D, HeLa cells were transfected with two different RNAi oligonucleotides for BAF155 (1 and 2) or a pool of four different oligonucleotides for MYBBP1A. The luciferase gene RNAi-oligo (Luc) was used as a negative control. Cells were lysed after 72 h. Nocodazole treatment was performed for the last 18 h, and then cells were harvested and subjected to mitotic shake-off before total lysis. Immunoblots (IB) with anti-MYBBP1A, BAF155, MCM2, Aurora A, Aurora B, α-tubulin (loading control), and anti-phospho-p160 antibodies are shown. E, anti-phospho-p160 detects overexpressed MYBBP1A protein. HeLa cells were transfected with a FLAG-tagged version of MYBBP1A or the empty vector, and lysates were loaded and analyzed with anti-phospho-p160, anti-FLAG, or anti-α-tubulin (loading control) antibodies. F and G, the anti-phospho-p160 specifically detects phosphorylated MYBBP1A. Empty vector or FLAG-MYBBP1A-transfected HeLa cells were treated with 10 nm calyculin A for 1 h before lysis, and samples were probed against anti-phospho-p160, FLAG, Aurora A, Aurora B, or phosphohistone H3 Ser10 antibodies. F, FLAG-MYBBP1A-transfected HeLa cell lysates were treated with 400 units of λ-phosphatase for 1 h at 30 °C and, following SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, were probed with anti-phospho-p160 or anti-FLAG antibodies. Ponceau S staining shows the presence of λ-phosphatase.

The HeLa nuclear extract, cytoplasmic extract, and 1 m fraction were then submitted to electrophoresis in a 3–8% Tris-acetate gel in order to enhance resolution and achieve a clearer detection in the high molecular weight range. Looking at the differential bands, we could detect a faintly Coomassie-stained band at the expected molecular weight present only in the nuclear extract (NE) and in 1 m fractions (Fig. 2C). We excised this band and subjected it to trypsin digestion for MS identification. MALDI-TOF analysis of tryptic digests from the 1 m and nuclear extract fractions revealed the presence of a high score candidate named MYBBP1A (supplemental Table S1). The tryptic digest was also analyzed by LC MS/MS, which allowed us to confirm MYBBP1A identification and also revealed the presence in both samples of a second putative p160 candidate, the SNF complex 155-kDa component BAF155 (supplemental Table S2).

To discriminate between the candidates and confirm the identity of p160, RNAi experiments were performed against MYBBP1A or BAF155 (Fig. 2D). HeLa cells were transfected separately with two different RNAi oligonucleotides specific for BAF155 or with a pool of 4 oligonucleotides against MYBBP1A. Cells were then treated with nocodazole, and only mitotic cells were harvested and analyzed to enrich the p160 mitosis-specific signal. As reported in Fig. 2D, MYBBP1A depletion abrogates the phospho-p160 signal, whereas depletion of BAF155, similarly to control cells (Luc), does not affect p160 phosphorylation, suggesting that indeed the p160 phosphorylation signal is related to MYBBP1A expression. No modulation was observed for MCM2, Aurora A, or Aurora B levels upon MYBBP1A or BAF155 RNAi.

To rule out the possibility that p160 reduction could be simply due to a secondary event caused by MYBBP1A knock-down, MYBBP1A was cloned and overexpressed in HeLa cells as a FLAG-tagged protein. As reported in Fig. 2E, Western blot analysis on asynchronous cells using the phospho-p160 antibody detected a p160 band only in cells transfected with MYBBP1A, confirming that MYBBP1A is recognized by this antibody. Furthermore, the MYBBP1A band was more intense when HeLa cells were treated with the phosphatase inhibitor calyculin A (Fig. 2F), and conversely, treatment of cellular lysates with λ-phosphatase completely abrogates the signal (Fig. 2G). This indicates that anti-phospho-p160 specifically recognizes phosphorylated MYBBP1A.

Identification of the Aurora-dependent Phosphorylation Site on MYBBP1A

To verify if Aurora kinase can actually phosphorylate MYBBP1A, generating a phospho-p160 signal in cellular lysates, MYBBP1A-depleted HeLa cell extracts were used in an in vitro Aurora kinase assay in comparison with control cell lysates. As shown in Fig. 3A, although phospho-p160 was clearly visible in luciferase (Luc)- or BAF155-depleted extracts, it could hardly be detected in MYBBP1A-depleted samples, confirming in cells that p160 is MYBBP1A and that this protein can be phosphorylated by Aurora when present in cell extracts.

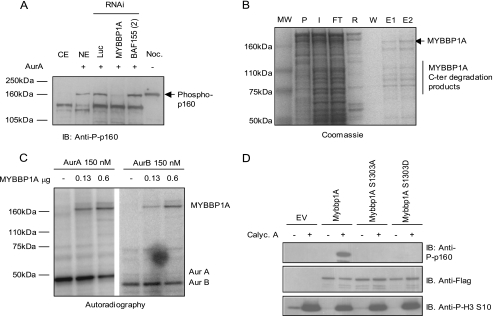

FIGURE 3.

MYBBP1A is phosphorylated on Ser1303 by Aurora kinase. A, Aurora A specifically phosphorylates MYBBP1A. HeLa cytoplasmic (CE) or nuclear extracts (NE) together with luciferase (Luc), MYBBP1A, or BAF155 (oligo2) RNAi oligonucleotide-transfected samples, were incubated with Aurora A kinase in a kinase assay. Nocodazole (Noc.)-treated HeLa cell lysates were loaded as a control for the phospho-p160 signal detected by immunoblot (IB). B, MYBBP1A recombinant protein was expressed and purified from E. coli. Pellet (P), input (I), flow-through (FT), resin before elution (R), wash (W), and two different elution steps after PreScission protease cleavage (E1 and E2 fractions) are shown by Coomassie Blue staining. In E1 and E2 eluates, full-length MYBBP1A at 160 kDa (MW) and C-terminal degradation products are indicated. C, recombinant Aurora A and Aurora B kinases phosphorylate MYBBP1A full-length protein. Different amounts of MYBBP1A were added in a kinase assay experiment in the presence of 150 nm Aurora A or Aurora B kinases. MYBBP1A Aurora-dependent phosphorylation or Aurora kinase autophosphorylation was detected by autoradiography. D, Ser1303 phosphorylation was detected using the anti-phospho-p160 antibody. HeLa cells were transfected with an empty vector (EV) or FLAG-tagged versions of full-length wild type MYBBP1A or the two mutants S1303A or S1303D. 10 nm calyculin A treatment was performed 1 h before cellular lysis in the indicated samples. Lysates were loaded on a SDS-PAGE gel and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-p160, FLAG, or phosphohistone H3 Ser10 antibodies to verify the phospho-p160 signal, transfection, and calyculin A treatment efficiency, respectively.

We then decided to map the Aurora-dependent phosphorylation site(s) of MYBBP1A. MYBBP1A recombinant protein was expressed and purified as a glutathione S-transferase fusion protein from E. coli, followed by on column tag removal with PreScission protease (Fig. 3B). The purified protein showed a number of degradation products below 160 kDa (eluted fractions E1 and E2), and the majority of these bands could be assigned by MALDI-TOF analysis to MYBBP1A fragments, deriving mainly from C-terminal processing (data not shown). Recombinant MYBBP1A was then used in an in vitro kinase assay with Aurora A or Aurora B kinases in the presence of [32P]ATP (Fig. 3C). The main labeled band corresponded to the full-length MYBBP1A protein, indicating that the main phosphorylation site resides in the very C-terminal portion of the protein and that both Aurora A and B kinases are capable of phosphorylating full-length MYBBP1A in vitro (Fig. 3C). The bands visible in the lower part of the gel correspond to Aurora A and Aurora B autophosphorylated proteins, indicating that both kinases were active in these conditions. Sequence analysis of MYBBP1A showed the presence of an Aurora kinase phosphorylation consensus sequence in the C-terminal portion containing a single phosphorylatable residue, Ser1303. Furthermore, Ser1303 in MYBBP1A resides in a sequence (KARLSLVIRS) that resembles the MCM2 sequence used to raise the phospho-p160 antibody, explaining the observed cross-reactivity.

To confirm that Ser1303 is phosphorylated in vivo, two different MYBBP1A mutants were generated at this site (MYBBP1A S1303D and MYBBP1A S1303A) and expressed in HeLa cells. Anti-phospho-p160 was not able to detect any band when the overexpressed protein harbored a mutation on Ser1303 to alanine or aspartic acid (Fig. 3D), even in the presence of calyculin A treatment, thus confirming that MYBBP1A Ser1303 is an in vivo phosphorylation site.

MYBBP1A Is Phosphorylated in Vivo by Aurora B

MYBBP1A is phosphorylated by Aurora kinases in vitro and is highly phosphorylated in nocodazole-arrested mitotic cells. Because Aurora kinases are known to be key mitotic regulators, we wanted to ascertain whether MYBBP1A was also regulated by Aurora kinases in vivo. To do this, we utilized a pan-Aurora inhibitor, Danusertib, which has shown preclinical and clinical efficacy (5, 6). Nocodazole- or taxol-arrested mitotic HeLa cells were treated with Danusertib (1 μm) for 4 h, and MYBBP1A phosphorylation status was then investigated. Both nocodazole- and taxol-arrested cells show up-regulation of MYBBP1A phosphorylation, which is completely abolished upon Danusertib treatment (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 6). This was shown to be a specific effect because it was maintained in the presence of MG132, which keeps cells arrested in M phase, even upon Aurora inhibition, by blocking the proteasome-mediated degradation of securin, cyclin B1, Aurora A, and Aurora B (44, 45) (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 2 and 6 with lanes 3 and 7). Thus, the enzymatic activity of the Aurora kinases is required to maintain MYBBP1A phosphorylation.

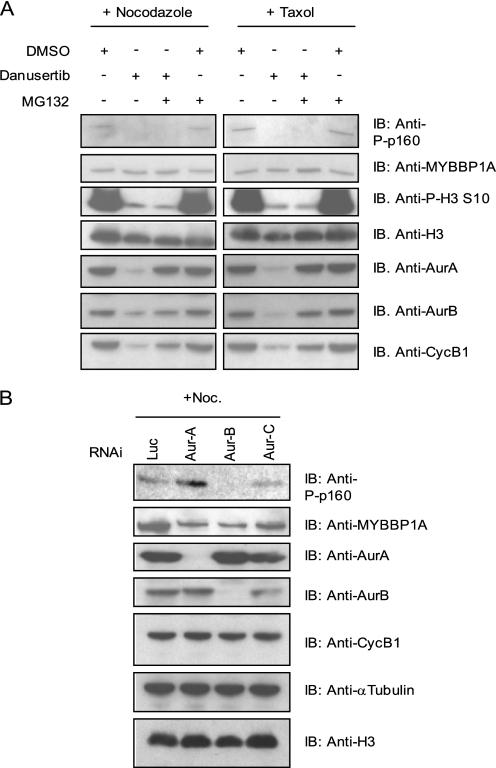

FIGURE 4.

MYBBP1A is phosphorylated in vivo by Aurora B. A, inhibition of Aurora kinases upon Danusertib treatment inhibits MYBBP1A Ser1303 phosphorylation. HeLa cells were treated with nocodazole (75 ng/ml) or taxol (0.5 μm) for 16 h. Mitotic shake-off was performed, and mitotic cells were replated in the presence of nocodazole or taxol together with Danusertib (1 μm) alone or in combination with MG132 (10 μm) for 4 h before cellular lysis. Lysates were immunoblotted (IB) with anti-phospho-p160, total MYBBP1A, phosphohistone H3 Ser10, Aurora A, Aurora B, histone H3, and cyclin B1 antibodies, as indicated. B, aurora B regulates MYBBP1A phosphorylation. RNAi experiments with luciferase (Luc)-, Aurora A-, Aurora B-, or Aurora C-specific oligonucleotides in HeLa cells was performed. After 24 h, nocodazole (Noc.; 75 ng/ml) was added for 15 h. Mitotic cells were then harvested by mitotic shake-off and lysed. Anti-phospho-p160, total MYBBP1A, Aurora A, Aurora B, cyclin B1, α-tubulin, and histone H3 were analyzed by immunoblot, as indicated. Aurora C mRNA knockdown efficiency was over 75% (data not shown).

To understand which Aurora kinase regulates MYBBP1A phosphorylation in vivo, we separately depleted the three Aurora kinases (A, B, or C) in HeLa cells and measured MYBBP1A phosphorylation in mitotic cells following nocodazole treatment. As reported in Fig. 4B, only Aurora B depletion decreased MYBBP1A phosphorylation, whereas Aurora A or Aurora C RNAi had no effect. In addition, under these experimental conditions, no effects were observed on the expression of total MYBBP1A or on the mitotic marker cyclin B1 following Aurora kinase RNAi, excluding RNAi-related cell cycle effects. These results indicate that Aurora B is the main regulator of MYBBP1A Ser1303 phosphorylation in vivo.

MYBBP1A Has a Role in the Mitotic Phase of the Cell Cycle

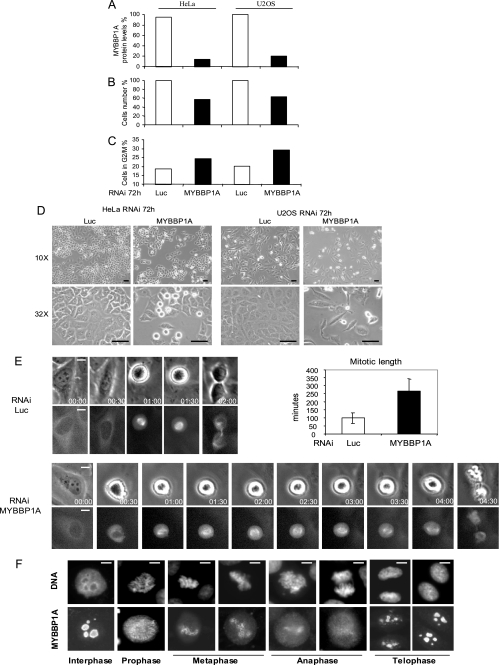

MYBBP1A was shown to be phosphorylated by Aurora B, one of the main mitotic kinases required for proper mitotic progression (46), and MYBBP1A is phosphorylated in mitotic cells after nocodazole or taxol treatment. For these reasons, we decided to investigate the role of MYBBP1A in the mitotic phase of the cell cycle. MYBBP1A RNAi experiments were conducted in both HeLa and U2OS cells. As shown in Fig. 5, MYBBP1A is required for proper cellular proliferation; 72 h after transfection, 75% MYBBP1A depletion (Fig. 5A) causes a 40% reduction of total cell number in both treated cell lines (Fig. 5, B and D). Moreover, fluorescence-activated cell sorting profiles and phase-contrast images indicate an enrichment in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 5, C and D), and a detailed analysis by time lapse videomicroscopy of U2OS cells overexpressing YFP-α-tubulin shows that the absence of MYBBP1A causes a mitotic phase prolongation and defects in mitotic spindle assembly and stability (Fig. 5E), which ultimately leads to cell death.

FIGURE 5.

MYBBP1A is required for correct mitotic progression and cellular proliferation. A–D, HeLa and U2OS cells were transfected with MYBBP1A- or luciferase (Luc)-specific RNAi oligonucleotides. After 72 h, MYBBP1A protein levels (A), cellular count (B), and fluorescence-activated cell sorting profile analysis of the G2/M population (C) were analyzed. In D, representative images of HeLa and U2OS cells are shown 72 h after oligonucleotide transfection at ×10 or ×32 magnification. Scale bars, 50 μm. E, asynchronous U2OS cells overexpressing a YFP-tagged version of α-tubulin were followed by time lapse videomicroscopy 24 h after MYBBP1A or luciferase RNAi experiments. Both bright field and YFP-dependent fluorescent signals of a representative mitotic cell are shown. Images were taken every 30 min, as indicated. Scale bars, 10 μm. The graph shows the average duration of mitosis on 25 luciferase and 20 MYBBP1A-depleted cells. F, MYBBP1A has a perichromosomal localization in mitotic cells. FLAG-MYBBP1A-transfected HeLa cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence 24 h after transfection. Representative images of cells in the different mitotic phases are shown. DNA was visualized by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and MYBBP1A by anti-FLAG antibody staining. Scale bars, 5 μm.

Finally, immunofluorescence experiments performed in HeLa cells transfected with a FLAG-tagged version of wild-type MYBBP1A confirmed its nucleolar localization in interphase cells and also showed a perichromosomal localization in mitotic cells from prophase to anaphase (Fig. 5F). This confirms a novel role of MYBBP1A in mitosis, which could be dependent on Aurora B-mediated phosphorylation.

DISCUSSION

Here we have identified and characterized human MYBBP1A (UniProt entry Q9BQG0) as a novel in vivo substrate of the Aurora B kinase. Orthologous genes for MYBBP1A sharing a high degree of similarity (∼80%) are present in rats and mice (UniProt entries Q7TPV4 and O35821, respectively). Protein homologues have also been recognized in dogs, bovines, and chickens, and a MYBBP1A-like protein spanning 1269 residues and showing a 60% similarity to the human protein has been identified in zebrafish, suggesting that MYBBP1A is significantly conserved across vertebrate species (data not shown) (47). In addition, Ser1303, the residue that we have identified as an Aurora B-dependent phosphorylation site, is conserved together with the surrounding Aurora consensus sequence, in rodents, dogs, and bovines (data not shown).

MYBBP1A was originally identified as a protein able to interact with the negative regulatory domain of c-Myb; however, it was later shown to lack any significant effect in a Myb-dependent transcription reporter assay (32, 33). MYBBP1A was shown to localize mainly in the nucleolus (32), where Myb is not detected (48). In addition, whereas c-Myb expression is tissue-specific, being essential for hematopoietic cell proliferation and differentiation (49, 50), MYBBP1A appears to be ubiquitously expressed (32). Taken together, these observations suggest that MYBBP1A has other functions independent from Myb. In fact, in studies from a number of different groups, MYBBP1A has been found to interact with and regulate several transcription factors; it binds and represses both Prep1-Pbx1, involved in development and organogenesis, and PGC-1a, a key regulator of metabolic processes such as mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration and gluconeogenesis in liver (34, 35). MYBBP1A acts as a co-repressor for RelA/p65, a member of the NF-κB family, by competing with the co-activator p300 histone acetyltransferase for interaction with the transcription activation domain of RelA/p65. It is also a co-repressor on the period2 promoter, repressing the expression of per2, an essential gene in the regulation of the circadian clock (37, 51). Conversely, MYBBP1A is a positive regulator of the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor, which mediates transcriptional responses to certain hydrophobic ligands, such as dioxin, by enhancing the ability of the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor to activate transcription (36).

MYBBP1A has been confirmed as a resident protein of the nucleolus by three large scale proteomic studies that have established a protein inventory of this subnuclear compartment (30, 52, 53). The nucleolus is a specialized nuclear domain and the site of ribosome biogenesis. It is a dynamic structure that disassembles at the beginning of mitosis when transcription shuts down and reassembles at the end of mitosis/beginning of G1 around the ribosomal DNA genes, where the transcription and processing machineries responsible for ribosome biogenesis concentrate (54).

Although long dubbed “an organelle formed by the act of building a ribosome” (55), the nucleolus has now been shown to contain many proteins unrelated to ribosome biogenesis, including proteins involved in DNA replication and repair, telomere maintenance, protein degradation, and cell cycle regulation, supporting the hypothesis that this organelle fulfills several additional functions (54).

Lines of evidence for this hypothesis come from specific nucleolar proteins that make a connection between the nucleolus and the chromosomal periphery, such as nucleolin and Rrs1. Human nucleolin is one of the most extensively studied nucleolar proteins and has been shown to play essential roles in ribosomal DNA transcription and maturation, ribosome assembly, and nucleocytoplasmic transport (56, 57). During mitosis, nucleolin is localized to the chromosome periphery, including the vicinity of the outer kinetochore of chromosomes, and nucleolin-depleted cells show disorganization of nucleoli in interphase and delayed cell cycle progression, mainly due to a delay at prometaphase with misaligned or non-aligned chromosomes and defects in chromosome biorientation (58). Rrs1 is a protein required for ribosome biogenesis in yeast (59). Its human orthologue localizes to nucleoli in interphase and at the chromosomal periphery from prometaphase to anaphase (60). Rrs1 depletion by RNAi results in defects in chromosome congression, with mitotic cells showing aberrant chromosome alignment at the metaphase plate (60). The chromosome periphery might then act as a means of transport for various proteins, including nucleolar proteins (61). Alternatively, co-localization and storage at the nucleolus might provide a regulatory mechanism for the assembly of specific nucleo-protein complexes and their timely release during mitosis, as suggested by Wong et al. (62). The kinetochore proteins CENPC1 and INCENP have indeed been shown to accumulate at the nucleolus in interphase in a centromeric α-satellite RNA-dependent manner. Aurora B has also been detected in purified nucleoli, together with its CPC partners INCENP and borealin (30). Of additional relevance is the observation that Aurora B has been shown to regulate the nucleolar RNA methyltransferase NSUN2 in mitosis, through the inactivating phosphorylation of Ser139 (31). This phosphorylation event drives the dissociation of NSUN2 from its nucleolar partner NPM1, suggesting that Aurora B is a mitotic kinase that participates in regulating the assembly cycle of nucleolar RNA-processing machinery. Indeed, recent literature data show that NSUN2 is required for proper spindle assembly and chromosome segregation by regulating the localization of NuSAP, an essential spindle assembly factor; NSUN2 has been furthermore shown to be overexpressed in breast cancer (63, 64).

Here we have shown that another nucleolar protein, MYBBP1A, is phosphorylated by the mitotic kinase Aurora B on a site that has been mapped to serine 1303. We have found that this phosphorylation event peaks in G2/M, upon treatment with mitotic poisons, and is completely abolished when cells are exposed to the Aurora inhibitor Danusertib. Moreover, only Aurora B silencing is effective in suppressing MYBBP1A Ser1303 phosphorylation, indicating that Aurora B, and not A or C, is responsible for this phosphorylation event in vivo.

MYBBP1A is reported to be a heavily phosphorylated protein in cells, according to several recent large scale mass spectrometry-based phosphoproteomic studies (65–72). The majority of the phosphorylation sites mapped in MYBBP1A in these studies (18 of a total of 21) reside within the ∼200-amino acid-long C-terminal portion of the protein, which has been shown to be relevant for its nuclear and nucleolar localization (73). Notably, MYBBP1A was also found to be a component of the proteome as well as the phospho-proteome of the human mitotic spindle (71, 74), pointing to an additional co-localization where Aurora B kinase may encounter and phosphorylate MYBBP1A. Indeed, the levels of phosphorylation of a number of sites in MYBBP1A appear to increase massively in mitotic cells (66, 69), including phosphorylation at Ser1303 (69), which is the site that we have shown to be Aurora B-dependent in cell lines, further confirming Ser1303 as an in vivo phosphorylation site for MYBBP1A. However, we have been unable to detect any difference in MYBBP1A cellular localization or transcriptional activity using GAL4-dependent or NF-κB reporter assays in the presence of Danusertib or upon testing Ser1303 mutants (data not shown). Instead, MYBBP1A depletion by RNAi causes a delay in progression through mitosis and defects in mitotic spindle assembly and stability, indicating that, like other nucleolar proteins, MYBBP1A may have a role in insuring correct mitotic progression. This theory is supported by our immunofluorescence studies, which have shown a perichromosomal localization of MYBBP1A from prophase to metaphase. Taken together, our results indicate that MYBBP1A may be part of a nucleolar pool of proteins playing a role in mitotic progression. Further studies are needed to clarify the interplay between nucleolar and mitotic functions of MYBBP1A and also to understand the contribution of Aurora B to the regulation of MYBBP1A in mitosis and the relevance of Ser1303 phosphorylation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Vanessa Marchesi, Francesco Sola, Rosario Baldi, and Mauro Uggeri.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

L. Rusconi and P. Carpinelli, unpublished observations.

- CPC

- chromosomal passenger complex

- RNAi

- RNA interference

- MES

- 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- YFP

- yellow fluorescent protein

- MALDI

- matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

- tandem MS

- LC

- liquid chromatography

- HPLC

- high pressure liquid chromatography.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kollareddy M., Dzubak P., Zheleva D., Hajduch M. (2008) Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky Olomouc Czech. Repub. 152, 27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vader G., Lens S. M. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1786, 60–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katayama H., Brinkley W. R., Sen S. (2003) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 22, 451–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou H., Kuang J., Zhong L., Kuo W. L., Gray J. W., Sahin A., Brinkley B. R., Sen S. (1998) Nat. Genet. 20, 189–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpinelli P., Moll J. (2009) Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 12, 533–542 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollard J. R., Mortimore M. (2009) J. Med. Chem. 52, 2629–2651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutertre S., Cazales M., Quaranta M., Froment C., Trabut V., Dozier C., Mirey G., Bouché J. P., Theis-Febvre N., Schmitt E., Monsarrat B., Prigent C., Ducommun B. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117, 2523–2531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eyers P. A., Erikson E., Chen L. G., Maller J. L. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 691–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giet R., Uzbekov R., Cubizolles F., Le Guellec K., Prigent C. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 15005–15013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirota T., Kunitoku N., Sasayama T., Marumoto T., Zhang D., Nitta M., Hatakeyama K., Saya H. (2003) Cell 114, 585–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Q., Kaneko S., Yang L., Feldman R. I., Nicosia S. V., Chen J., Cheng J. Q. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 52175–52182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ouchi M., Fujiuchi N., Sasai K., Katayama H., Minamishima Y. A., Ongusaha P. P., Deng C., Sen S., Lee S. W., Ouchi T. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19643–19648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venoux M., Basbous J., Berthenet C., Prigent C., Fernandez A., Lamb N. J., Rouquier S. (2008) Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 215–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bishop J. D., Schumacher J. M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 27577–27580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brittle A. L., Nanba Y., Ito T., Ohkura H. (2007) Exp. Cell Res. 313, 2780–2785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crosio C., Fimia G. M., Loury R., Kimura M., Okano Y., Zhou H., Sen S., Allis C. D., Sassone-Corsi P. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 874–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knowlton A. L., Lan W., Stukenberg P. T. (2006) Curr. Biol. 16, 1705–1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison C., Henzing A. J., Jensen O. N., Osheroff N., Dodson H., Kandels-Lewis S. E., Adams R. R., Earnshaw W. C. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 5318–5327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speliotes E. K., Uren A., Vaux D., Horvitz H. R. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 211–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeitlin S. G., Shelby R. D., Sullivan K. F. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 155, 1147–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams R. R., Wheatley S. P., Gouldsworthy A. M., Kandels-Lewis S. E., Carmena M., Smythe C., Gerloff D. L., Earnshaw W. C. (2000) Curr. Biol. 10, 1075–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruchaud S., Carmena M., Earnshaw W. C. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 798–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vader G., Medema R. H., Lens S. M. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 173, 833–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirota T., Lipp J. J., Toh B. H., Peters J. M. (2005) Nature 438, 1176–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vader G., Kauw J. J., Medema R. H., Lens S. M. (2006) EMBO Rep. 7, 85–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaitna S., Mendoza M., Jantsch-Plunger V., Glotzer M. (2000) Curr. Biol. 10, 1172–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delacour-Larose M., Thi M. N., Dimitrov S., Molla A. (2007) Cell Cycle 6, 1878–1885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gassmann R., Carvalho A., Henzing A. J., Ruchaud S., Hudson D. F., Honda R., Nigg E. A., Gerloff D. L., Earnshaw W. C. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 166, 179–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez J. A., Lens S. M., Span S. W., Vader G., Medema R. H., Kruyt F. A., Giaccone G. (2006) Oncogene 25, 4867–4879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andersen J. S., Lam Y. W., Leung A. K., Ong S. E., Lyon C. E., Lamond A. I., Mann M. (2005) Nature 433, 77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakita-Suto S., Kanda A., Suzuki F., Sato S., Takata T., Tatsuka M. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 1107–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tavner F. J., Simpson R., Tashiro S., Favier D., Jenkins N. A., Gilbert D. J., Copeland N. G., Macmillan E. M., Lutwyche J., Keough R. A., Ishii S., Gonda T. J. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 989–1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Favier D., Gonda T. J. (1994) Oncogene 9, 305–311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Díaz V. M., Mori S., Longobardi E., Menendez G., Ferrai C., Keough R. A., Bachi A., Blasi F. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 7981–7990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan M., Rhee J., St-Pierre J., Handschin C., Puigserver P., Lin J., Jäeger S., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Spiegelman B. M. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 278–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones L. C., Okino S. T., Gonda T. J., Whitlock J. P., Jr. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 22515–22519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Owen H. R., Elser M., Cheung E., Gersbach M., Kraus W. L., Hottiger M. O. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 366, 725–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang W., Rogozin I. B., Koonin E. V. (2003) Cell Cycle 2, 120–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimizu K., Kawasaki Y., Hiraga S., Tawaramoto M., Nakashima N., Sugino A. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 9133–9138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knebel A., Morrice N., Cohen P. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 4360–4369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheeseman I. M., Anderson S., Jwa M., Green E. M., Kang J., Yates J. R., 3rd, Chan C. S., Drubin D. G., Barnes G. (2002) Cell 111, 163–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costa A., Onesti S. (2008) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36, 136–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Troiani S., Uggeri M., Moll J., Isacchi A., Kalisz H. M., Rusconi L., Valsasina B. (2005) J. Proteome Res. 4, 1296–1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee D. H., Goldberg A. L. (1998) Trends Cell Biol. 8, 397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peters J. M. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 644–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelly A. E., Funabiki H. (2009) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 51–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amsterdam A., Nissen R. M., Sun Z., Swindell E. C., Farrington S., Hopkins N. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12792–12797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bading H., Rauterberg E. W., Moelling K. (1989) Exp. Cell Res. 185, 50–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anfossi G., Gewirtz A. M., Calabretta B. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 3379–3383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mucenski M. L., McLain K., Kier A. B., Swerdlow S. H., Schreiner C. M., Miller T. A., Pietryga D. W., Scott W. J., Jr., Potter S. S. (1991) Cell 65, 677–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hara Y., Onishi Y., Oishi K., Miyazaki K., Fukamizu A., Ishida N. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 1115–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andersen J. S., Lyon C. E., Fox A. H., Leung A. K., Lam Y. W., Steen H., Mann M., Lamond A. I. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scherl A., Couté Y., Déon C., Callé A., Kindbeiter K., Sanchez J. C., Greco A., Hochstrasser D., Diaz J. J. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 4100–4109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boisvert F. M., van Koningsbruggen S., Navascués J., Lamond A. I. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 574–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mélèse T., Xue Z. (1995) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 7, 319–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mongelard F., Bouvet P. (2007) Trends Cell Biol. 17, 80–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Storck S., Shukla M., Dimitrov S., Bouvet P. (2007) Subcell. Biochem. 41, 125–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ma N., Matsunaga S., Takata H., Ono-Maniwa R., Uchiyama S., Fukui K. (2007) J. Cell Sci. 120, 2091–2105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsuno A., Miyoshi K., Tsujii R., Miyakawa T., Mizuta K. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 2066–2074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gambe A. E., Matsunaga S., Takata H., Ono-Maniwa R., Baba A., Uchiyama S., Fukui K. (2009) FEBS Lett. 583, 1951–1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Hooser A. A., Yuh P., Heald R. (2005) Chromosoma 114, 377–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wong L. H., Brettingham-Moore K. H., Chan L., Quach J. M., Anderson M. A., Northrop E. L., Hannan R., Saffery R., Shaw M. L., Williams E., Choo K. H. (2007) Genome Res. 17, 1146–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frye M., Dragoni I., Chin S. F., Spiteri I., Kurowski A., Provenzano E., Green A., Ellis I. O., Grimmer D., Teschendorff A., Zouboulis C. C., Caldas C., Watt F. M. (2010) Cancer Lett. 289, 71–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hussain S., Benavente S. B., Nascimento E., Dragoni I., Kurowski A., Gillich A., Humphreys P., Frye M. (2009) J. Cell Biol. 186, 27–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beausoleil S. A., Jedrychowski M., Schwartz D., Elias J. E., Villén J., Li J., Cohn M. A., Cantley L. C., Gygi S. P. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12130–12135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beausoleil S. A., Villén J., Gerber S. A., Rush J., Gygi S. P. (2006) Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 1285–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cantin G. T., Yi W., Lu B., Park S. K., Xu T., Lee J. D., Yates J. R., 3rd (2008) J. Proteome Res. 7, 1346–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Daub H., Olsen J. V., Bairlein M., Gnad F., Oppermann F. S., Körner R., Greff Z., Kéri G., Stemmann O., Mann M. (2008) Mol. Cell 31, 438–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dephoure N., Zhou C., Villén J., Beausoleil S. A., Bakalarski C. E., Elledge S. J., Gygi S. P. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10762–10767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Imami K., Sugiyama N., Kyono Y., Tomita M., Ishihama Y. (2008) Anal. Sci. 24, 161–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nousiainen M., Silljé H. H., Sauer G., Nigg E. A., Körner R. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 5391–5396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Olsen J. V., Blagoev B., Gnad F., Macek B., Kumar C., Mortensen P., Mann M. (2006) Cell 127, 635–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Keough R. A., Macmillan E. M., Lutwyche J. K., Gardner J. M., Tavner F. J., Jans D. A., Henderson B. R., Gonda T. J. (2003) Exp. Cell Res. 289, 108–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sauer G., Körner R., Hanisch A., Ries A., Nigg E. A., Silljé H. H. (2005) Mol. Cell Proteomics 4, 35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.