Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) gained considerable interest as a therapeutic target during chronic inflammatory diseases. Remarkably, the pathogenesis of diseases such as multiple sclerosis or Alzheimer is associated with impaired PPARγ expression. Considering that regulation of PPARγ expression during inflammation is largely unknown, we were interested in elucidating underlying mechanisms. To this end, we initiated an inflammatory response by exposing primary human macrophages to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and observed a rapid decline of PPARγ1 expression. Because promoter activities were not affected by LPS, we focused on mRNA stability and noticed a decreased mRNA half-life. As RNA stability is often regulated via 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs), we analyzed the impact of the PPARγ-3′-UTR by reporter assays using specific constructs. LPS significantly reduced luciferase activity of the pGL3-PPARγ-3′-UTR, suggesting that PPARγ1 mRNA is destabilized. Deletion or mutation of a potential microRNA-27a/b (miR-27a/b) binding site within the 3′-UTR restored luciferase activity. Moreover, inhibition of miR-27b, which was induced upon LPS exposure, partially reversed PPARγ1 mRNA decay, whereas miR-27b overexpression decreased PPARγ1 mRNA content. In addition, LPS further reduced this decay. The functional relevance of miR-27b-dependent PPARγ1 decrease was proven by inhibition or overexpression of miR-27b, which affected LPS-induced expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin (IL)-6. We provide evidence that LPS-induced miR-27b contributes to destabilization of PPARγ1 mRNA. Understanding molecular mechanisms decreasing PPARγ might help to better appreciate inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Gene/Regulation, Receptors/Nuclear, RNA/MicroRNA, Inflammation, Macrophage

Introduction

Inflammation is highly regulated. A pro-inflammatory response is rapidly initiated, whereas resolution of inflammation follows the initial challenge. Dampening inflammation is crucial to return to homeostasis, whereas prolonged and unhalted inflammation explains the pathogenesis of many chronic inflammatory diseases (1).

Resolution of inflammation is partly achieved by regulating mRNA stability of pro-inflammatory mediators at the post-transcriptional level thus, guaranteeing a rapid response. Regulated transcripts often contain an AU-rich 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR).2 Sequences within the 3′-UTR are recognized by either AU-rich element (ARE)-binding proteins such as tristetraprolin but also by microRNAs (miRNAs, miRs) (reviewed in Ref. 2), which targets mRNAs for exosomal degradation. miRNAs present a large family of small non-coding RNAs with a length of ∼22 nucleotides. They are transcribed as primary miRNAs, which are processed by Drosha and Dicer to precursor and finally mature miRNAs (reviewed in Ref. 3). The mature miRNA is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). There it associates with Argonaute proteins to target specific mRNAs via base pairing between the 3′-UTR of the mRNA and the 5′-end of the miRNA, the so called seed region. RNA is then degraded upon recruitment of several proteins such as deadenylase complex, decapping enzymes, or activators (reviewed in Ref. 4). Functionally miRNAs play an eminent role in controlling immune responses and have been associated with several inflammatory diseases (5). miR-146 and miR-155 gained special interest and are well described for negatively regulating Toll-like receptor (TLR)-signaling (6). However, TLR activation also triggers induction of miRNAs such as miR-21 or miR-132 (5), underscoring their potential role in regulating immune responses.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) belongs to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors and originally has been characterized to be important for adipogenesis and glucose metabolism. There are two isoforms described (PPARγ1 and -2) (7), which are under the control of different promoters resulting in three established transcript variants. Transcript variants 1 and 3 code for PPARγ1 whereas transcript variant 2 codes for PPARγ2, which is mainly expressed in adipocytes (8, 9). During differentiation of macrophages primarily the promoter 3 and to a certain extent promoter 1 is activated. Consequently macrophages mainly express PPARγ1 (10). In macrophages PPARγ represses inducible nitric-oxide (NO) synthase induction as well as concomitant NO production (11) and attenuates the oxidative burst (13, 14). Moreover, inhibiting nuclear factor κB (NFκB) decreases expression of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) or IL-6 (12). Thus, PPARγ is important to shape an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype and appears crucial for dampening inflammation (15).

Insufficient resolution of an immune response often provokes chronic inflammatory diseases. Interestingly, these disease conditions often revealed impaired PPARγ abundance (16, 17). Because mechanisms attenuating PPARγ expression remained obscure, we investigated regulation of PPARγ during inflammation. Here we provide evidence that PPARγ1 mRNA is destabilized by miR-27b, which is induced in macrophages upon lipopolysaccharide (LPS) exposure.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Bay11–7082, 5–6 dichloro-1-β-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole (DRB), LPS (from Escherichia coli, serotype 0127:B8), and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany). Rosiglitazone was bought from Biomol GmbH (Hamburg, Germany), human recombinant TNFα came from PeproTech GmbH (Hamburg, Germany) and human recombinant interferon γ (IFNγ) was obtained from Roche Diagnostics GmbH (Mannheim, Germany). Oligonucleotides were bought from Biomers (Ulm, Germany).

Cell Culture

THP-1 monocytes were cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 5 mm glutamine. THP-1 monocytes were differentiated into macrophages by treatment with 50 nm PMA overnight and cultured for another 24 h in fresh medium prior to experiments.

Human monocytes were isolated from buffy coats (DRK-Blutspendedienst Baden-Württemberg-Hessen, Institut für Transfusionsmedizin und Immunhämatologie, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) using Ficoll-Hypaque gradients as described (14). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were washed twice with PBS and were allowed to adhere to culture dishes for 1 h at 37 °C. Non-adherent cells were removed and monocytes were then differentiated into macrophages by culturing them in RPMI 1640 containing 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 units/ml penicillin, 5 mm glutamine, and 10% AB positive human serum for 7 days.

Western Analysis

Western analysis was performed as described previously (18). Anti-PPARγ antibody (1:2000, H100-X from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Heidelberg, Germany) and anti-tubulin (1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich) were used. Detection and densitometric analysis were performed using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-COR Biosciences GmbH, Bad Homburg, Germany).

Vector Construction

To analyze the role of the 3′-UTR of PPARγ mRNA, the 3′-UTR was inserted downstream of the luciferase encoding region of the pGL3-control vector (Promega GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) using the In-Fusion™ Dry-Down PCR cloning kit (Clontech-Takara, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France). To this end, pGL3-control was cut with XbaI and the PPARγ-3′UTR (Acc. No. [NM_138711.3]) was amplified from cDNA of differentiated THP-1 macrophages using the following primer pair, which generates 15-bp overlaps complementary to pGL3-control (underlined). Forward: 5′-GCCGTGTAATTCTAGCAGAGAGTCCTGAGCC-3′, reverse: 5′-CCGCCCCGACTCTAGTTCATAATATGGTAATTTTTA-3′. To delete or mutate the miR-27b binding site within the 3′-UTR respectively, we used the QuikChange XL II site directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA) using pGL3-PPARγ-3′UTR as a template and the following oligonucleotides: ΔmiR-27: 5′-GGGAAAATCTGACACCTAAAAAGCATTTTAAAAAGAAAAGG-3′, C83A/U84G: 5′-CTGACACCTAAGAAATTTAAGGTGAAAAAGCATTTTAAAAAGAAAAGG-3′.

Reporter Assay

For reporter analysis 1 × 105/well THP-1 monocytes were seeded in 24-well plates and differentiated into macrophages. After 24 h culturing in fresh medium, cells were transfected with 0.75 μg of the different plasmids using JetPEI™ transfection reagent (Polyplus transfection, Illkirch, France) as described by the manufacturer. After transfection, cells were cultured in fresh medium for another 24 h prior to treatments. All reporter assays were performed in duplicate. Cell extracts were prepared after treatment with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 3 or 6 h. Luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity or protein concentration of each sample.

PPARγ promoter 1 and 3 activity was determined by using the constructs pGL3-γ1p3000 (8) and pGL3-γ3p800 (9) (kindly provided by J. Auwerx, Institut de Génétique et de Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire, Illkirch, France). To investigate PPARγ activity we performed reporter assays using the previously described peroxisome proliferator response element (PPRE) reporter construct pAOX-TKL (19). To analyze the impact of the PPARγ-3′-UTR, cells were transfected with the pGL3-control vector, pGL3-PPARγ-3′-UTR, pGL3-PPARγ-3′-UTR-ΔmiR-27, and pGL3-PPARγ-3′-UTR-C83A/U84G, respectively.

Transient Transfection with miRNA Mimic and Anti-miRNA Inhibitors

miRNA mimic and anti-miRNA inhibitors were transfected into primary human macrophages using Amaxa® Nucleofector® technology from Lonza Cologne AG (Cologne, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. In brief, 1.5 × 106 cells were transfected with 100–300 pmol of anti-miR-27a/b inhibitor or the anti-miR inhibitor negative control (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX) and 0.1, 1, or 10 pmol miR-27b mimic (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) or 0.5–2 μg Allstars negative control siRNA (Qiagen). Following transfection cells were seeded on 3-cm Primaria dishes and cultured for another 48 h prior to experiments.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated using PeqGold RNAPure Kit (PeqLab Biotechnologie GmbH, Erlangen, Germany) as described by the manufacturer. Reverse transcription was done with 1 μg of RNA using iScript™ cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad GmbH, Munich, Germany) or the miScript Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) for transcription of miRNAs. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with Absolute QPCR SYBRGreen Fluorescein Mix (Abgene, Hamburg, Germany) or miScript SYBR® Green PCR kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Amplification and data analysis were done using the MyiQ iCycler system from Bio-Rad. The following primer pairs were selected: 18 S forward: 5′-GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT-3′, 18 S reverse: 5′-CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG-3′, actin forward: 5′-TGACGGGGTCACCCACACTGTGCCCATCTA-3′, actin reverse: 5′-CTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGGACGATGGAGGG-3′, PPARγ-transcript variant 1 forward: 5′-GGCCCAGCGCACTCGGA-3′, PPARγ-transcript variant 3 forward: 5′-GCTGGTGACCAGAAGCCTGCAT-3′, PPARγ-exon1 reverse: 5′-GGCCAGAATGGCATCTCTGTGT-3′, TNFα forward: 5′-TCTCGAACCCCGAGTGACA-3′, TNFα reverse: 5′-GAGGAGCACATGGGTGGAG-3′. For determination of PPARγ1 and IL-6 mRNA as well as miR-27a/b and Rnu6B expression we used QuantiTect® Primer Assays (Qiagen). Values were normalized to 18 S ribosomal RNA, actin, or Rnu6B expression, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was performed at least three times and statistical analysis was done with paired or unpaired Student's t test. In the case of Western analysis representative data of at least three independently performed experiments are shown. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

RESULTS

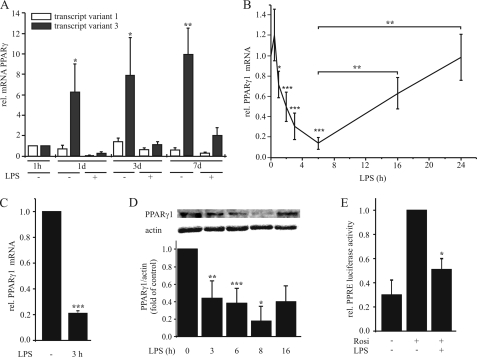

LPS Reduces PPARγ1 mRNA and Protein

Because mechanisms regulating PPARγ expression during inflammation are poorly understood, we investigated PPARγ1 regulation in macrophages. First we analyzed the mRNA level of transcript variants 1 and 3 both coding for the protein PPARγ1 during macrophage differentiation. To this end monocytes/macrophages were stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for 3 h at 1 h, 1 day, 3 days, and 7 days after isolation from buffy coats, and RNA was extracted. Expression of transcript variants 1 and 3 was determined by qPCR using specific oligonucleotides. Monocytes showed very low but similar abundance of transcript variants 1 and 3, while we predominantly observed induction of the PPARγ transcript variant 3 during differentiation (10-fold at day 7, see Fig. 1A). A minor induction of transcript variant 1 was observed after 3 days (1.3-fold), and a reduction in fully differentiated macrophages (0.58-fold at day 7) in comparison to monocytes (1 h). Upon LPS exposure, both variants were down-regulated (Fig. 1A). Next, we analyzed temporal pattern of total PPARγ1 mRNA expression (transcript variants 1 and 3) in response to 1 μg/ml LPS. There was a slight increase of PPARγ1 mRNA after 30 min followed by a rapid decrease of PPARγ1 with the lowest mRNA amounts after 6 h. Extended incubation periods allowed to recover PPARγ1 mRNA content nearly reaching control levels after 24 h of LPS treatment (Fig. 1B). The same pattern was observed in differentiated THP-1 macrophages. As seen in Fig. 1C, 3 h of LPS exposure significantly decreased PPARγ1 mRNA to ∼20% in comparison to unstimulated cells. To investigate whether a decrease of mRNA is reflected at protein level, we analyzed protein expression and PPARγ transactivation by reporter assay. Western analysis showed a time-dependent reduction of protein expression with a minimum at 8 h, again increasing afterward (Fig. 1D). To determine PPARγ transactivation, we transfected differentiated THP-1 macrophages with the PPRE reporter plasmid pAOX-TKL and pretreated cells the next day with 1 μg/ml LPS for 4 h followed by stimulation with 5 μm rosiglitazone for 4 h. Rosiglitazone, a well established synthetic PPARγ agonist (20), induced luciferase expression in control cells, whereas prestimulation with LPS prevented transactivation by rosiglitazone (Fig. 1E). LPS alone did not alter basal luciferase expression (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

LPS down-regulates PPARγ in primary macrophages. A, primary monocytes were isolated and cultured for 1 h up to 7 days and then stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for 3 h. RNA levels of the PPARγ transcript variants 1 and 3 were determined by qPCR. B, primary macrophages, differentiated for 7 days and C, differentiated THP-1 macrophages were stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS and total PPARγ1 mRNA was determined by qPCR. D, PPARγ protein was determined by Western analysis after treating primary macrophages with 1 μg/ml LPS up to 16 h. E, PPRE reporter activity was measured in differentiated THP-1 macrophages after pretreatment with 1 μg/ml LPS for 6 h, followed by 5 μm rosiglitazone for 4 h. Data present mean values ± S.E. n ≥ 4. Statistics were analyzed with the unpaired Student's t test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

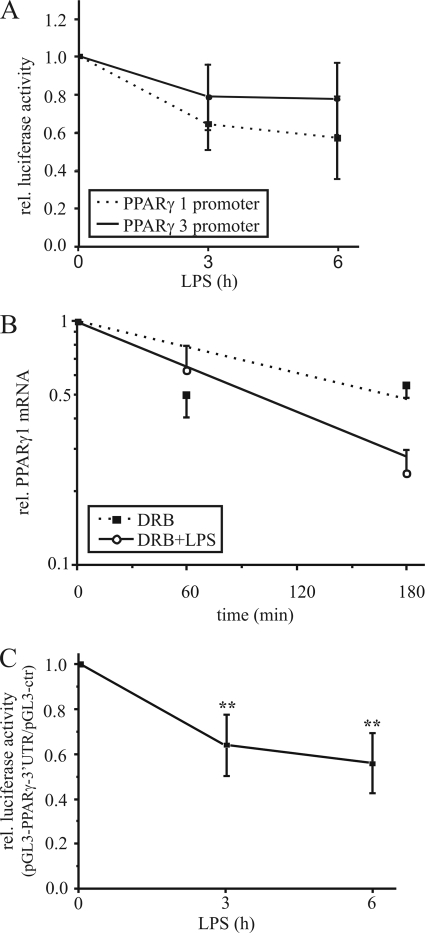

Destabilization of PPARγ1 mRNA

To determine whether down-regulation of PPARγ1 mRNA results from transcriptional regulation, we performed luciferase reporter assays using the PPARγ promoter 1 (pGL3-γ1p3000) and 3 (pGL3-γ3p800) constructs, containing the individual promoters upstream of the luciferase encoding region. Therefore, we transfected THP-1 macrophages with pGL3-γ1p3000 or pGL3-γ3p800 and stimulated them the next day with 1 μg/ml LPS for 3 and 6 h. LPS exposure attenuated PPARγ promoter 1 luciferase activity to ∼60% after 6 h, whereas luciferase activity of the PPARγ promoter 3 construct was only slightly reduced (Fig. 2A). Taking into consideration that fully differentiated macrophages express transcript variant 1 (resulting from activation of promoter 1) at low level only, we assumed that reduction of the promoter 1 activity to 60% is negligible for the LPS-induced PPARγ1 mRNA decrease. Thus, we next analyzed post-transcriptional events.

FIGURE 2.

Destabilization of PPARγ1 mRNA. A, PPARγ promoter 1 and 3 activities were determined by reporter assay in THP-1 macrophages, transfected with the promoter constructs and stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for 3 and 6 h. B, primary human macrophages were exposed to 100 μm DRB (filled squares) or 1 μg/ml LPS plus DRB (open circles) up to 3 h and total PPARγ1 mRNA (including transcripts 1 and 3) was determined by qPCR. C, differentiated THP-1 cells were transfected with the pGL3-control or pGL3-PPARγ-3′-UTR vector, and reporter activity was analyzed in response to 1 μg/ml LPS. Luciferase activity was normalized to protein and the ratio of pGL3-PPARγ-3′-UTR activity/pGL3-control is displayed. Data present mean values ± S.E., n ≥ 4. Statistics were analyzed with the unpaired Student's t test.*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Because regulation of mRNA stability is primarily mediated via the 3′-UTR, we analyzed the PPARγ mRNA sequences and noticed an AU-rich 3′-UTR, which is a typical feature of regulated mRNA transcripts. Therefore, we determined mRNA stability by exposing cells to the transcription inhibitor DRB (21) and 1 μg/ml LPS. DRB alone reduced PPARγ1 mRNA expression to ∼60% after 3 h, whereas DRB plus LPS decreased mRNA to 26% relative to untreated cells (Fig. 2B). Calculating the half-life of PPARγ1 revealed a reduction from 173 to 99 min, indicating that the mRNA decrease is caused by destabilization.

To strengthen our hypothesis we investigated the role of the PPARγ-3′-UTR on mRNA stability by reporter assay. Therefore, we cloned the 3′-UTR downstream of the luciferase encoding region within the pGL3-control vector. Differentiated THP-1 cells were transfected with pGL3-control and pGL3-PPARγ-3′-UTR respectively, and stimulated the next day with LPS for 3 and 6 h. LPS significantly reduced luciferase activity of the PPARγ-3′-UTR containing vector to ∼65% after 3 h and to 50% after 6 h relative to pGL3-control (Fig. 2C), underlining the importance of the 3′-UTR for PPARγ1 mRNA stability.

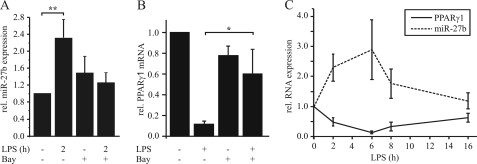

miR-27b Decreases PPARγ1 mRNA

The in-depth analysis of the PPARγ-3′-UTR (TargetScanHuman 5.1) revealed distinct AREs and a potential binding site for miR-27a/b (Fig. 3A). To elucidate the impact of miR-27a/b, we deleted or mutated the miR-27 sequence within the pGL3-PPARγ-3′UTR vector (Fig. 3B) and measured luciferase activity in transiently transfected THP-1 macrophages. Deletion as well as mutation of the miR-27 site completely abolished the LPS-mediated reduction of luciferase activity (Fig. 3C), suggesting a miR-27-dependent mechanism. To see whether miR-27a and b are induced by LPS in macrophages, cells were stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for 2 h. We observed a 2.3-fold induction of miR-27b (Fig. 4A) and a 1.6-fold induction of miR-27a (supplemental Fig. S1A). Because inhibition of NFκB with several inhibitors prevented a LPS-mediated PPARγ decrease (22), we pretreated macrophages with 10 μm of the NFκB inhibitor Bay11–7082 for 1 h followed by LPS exposure. Inhibition of NFκB prevented LPS-induced miR-27b up-regulation (Fig. 4A) and the PPARγ1 mRNA decrease (Fig. 4B). Moreover analyzing expression of miR-27b and PPARγ1 in response to the time of LPS treatment revealed an inverse correlation between PPARγ1 mRNA and miR-27b expression (Fig. 4C). To finally prove that miR-27 mediates LPS-induced PPARγ1 mRNA decay, we transfected primary macrophages with different concentrations of anti-miR-27 and stimulated cells with 1 μg/ml LPS for 3 h.

FIGURE 3.

Deletion and mutation of the miR-27b binding site reverses PPARγ1 mRNA decay. A, sequence of the AU-rich PPARγ-3′-UTR. The miR-27 binding site is underlined, whereas ARE 1 sites (AUUUA) are shaded, and ARE 4 (12-mer A/U with maximum one mismatch) sites are marked with boxes. B, alignment of the PPARγ-3′-UTR with the miR-27b sequence and the sequences of the construct pGL3-PPARγ-3′UTR-ΔmiR-27 and pGL3-PPARγ-3′UTR-C83A/U84G. Mutated nucleotides are underlined. C, differentiated THP-1 cells were transfected with pGL3-control, pGL3-PPARγ-3′UTR, pGL3-PPARγ-3′UTR-ΔmiR-27, or pGL3-PPARγ-3′UTR-C83A/U84G and luciferase expression was measured after stimulation with 1 μg/ml LPS for 3 h. Basal activity was set to 1, ratios of 3′-UTR constructs/pGL3-control are displayed. Data present mean values ± S.E., n ≥ 3. Statistics were analyzed with the unpaired Student's t test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

FIGURE 4.

NFκB-dependent miR-27b expression. A, miR-27b expression was measured in primary human macrophages in response to LPS (1 μg/ml, 2 h) by qPCR. To investigate a role of NFκB, cells were prestimulated for 1 h with 10 μm Bay11–7082. Basal expression was set to 1. B, primary human macrophages were pretreated with Bay as in A followed by 3 h of LPS exposure. PPARγ1 mRNA was determined by qPCR. C, temporal pattern of PPARγ1 mRNA and miR-27b expression was measured by qPCR after stimulation with 1 μg/ml LPS. Data represent mean values ± S.E., n ≥ 4. Statistics were analyzed with the paired Student's t test. *, p < 0.05.

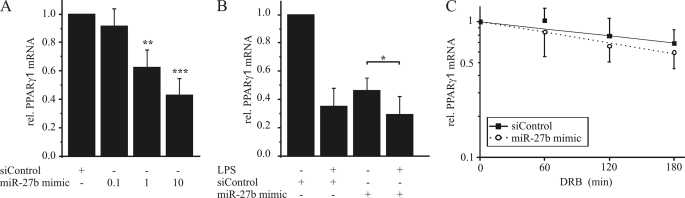

Anti-miR-27b prevented LPS-dependent PPARγ1 mRNA reduction in a concentration-dependent manner compared with a negative control (Fig. 5A). Inhibition of miR-27a showed no effect on PPARγ1 reduction upon LPS exposure (supplemental Fig. S1B). To analyze if inhibiting miR-27b also affects PPARγ1 mRNA half-life, we transfected human macrophages with the anti-miR-27b, stimulated cells with DRB and LPS as before and measured PPARγ1 mRNA expression. Inhibition of miR-27b impaired the ability of LPS to reduce the mRNA half-life (Fig. 5B), verifying the impact of miR-27b on PPARγ1 destabilization. In line, transfection with the miR-27b mimic reduced PPARγ1 mRNA in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6A). However, LPS treatment further reduced PPARγ1 mRNA expression (Fig. 6B). Moreover, a 2-fold induction of miR-27b by transfecting cells with miR-27b mimic decreased PPARγ1 mRNA to ∼70% (supplemental Fig. S2). To determine the impact of miR-27b overexpression on PPARγ1 mRNA half-life, we transfected primary human macrophages with siControl or miR-27b mimic and added 100 μm DRB for 1 to 3 h. Interestingly miR-27b overexpression did not significantly reduce PPARγ mRNA half-life in comparison to siControl-transfected cells in the absence of LPS (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of miR-27b reverses PPARγ1 mRNA destabilization. A, primary human macrophages were transfected with different concentrations (50, 100, 150 pmol) of anti-miR-27b or a negative control. After transfection, cells were stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for 3 h, and PPARγ1 mRNA level was determined by qPCR. B, primary human macrophages were transfected with 150 pmol of anti-miR-27b or negative control and PPARγ1 mRNA half-life was determined by stimulating cells with 100 μm DRB and 1 μg/ml LPS for 1 to 3 h. Data represent mean values ± S.E., n ≥ 4. Statistics were analyzed with the paired Student's t test. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

FIGURE 6.

Overexpression of miR-27b reduces PPARγ1 mRNA expression. A, primary human macrophages were transfected with different concentrations of miR-27b mimic (0.1, 1, or 10 pmol) or siControl, respectively. B, primary human macrophages were transfected with 10 pmol of miR-27b mimic or siControl and stimulated the next day with 1 μg/ml LPS for 3 h. C, primary human macrophages were transfected with 10 pmol of miR-27b mimic or siControl and treated for 1–3 h with 100 μm DRB 2 h after transfection. PPARγ1 mRNA content was determined by qPCR. Data represent mean values ± S.E., n ≥ 4. Statistics were analyzed with the paired Student's t test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Impact of Other Pro-inflammatory Stimuli on PPARγ1 Expression

To elucidate if other pro-inflammatory stimuli besides LPS also decrease PPARγ1 expression, we stimulated primary human macrophages with 15 ng/ml TNFα, 10 units/ml IFNγ, or IFNγ plus LPS for 3 h. TNFα also decreased PPARγ1 mRNA expression albeit to a lesser extent than LPS, whereas IFNγ increased PPARγ1 mRNA. Interestingly, stimulation with IFNγ plus LPS also reduced PPARγ1 mRNA, suggesting that TLR4 activation overrules IFNγ signaling (supplemental Fig. S2A).

Next, we investigated the role of miR-27b in TNFα-mediated PPARγ1 mRNA decay. TNFα also induced miR-27b expression (supplemental Fig. S2B). Moreover, inhibiting miR-27b by transfecting cells with anti-miR-27b not only prevented the reduction but even allowed induction of PPARγ1 mRNA (supplemental Fig. S2C), suggesting that besides miR-27b-dependent down-regulation, other regulatory mechanisms are operating.

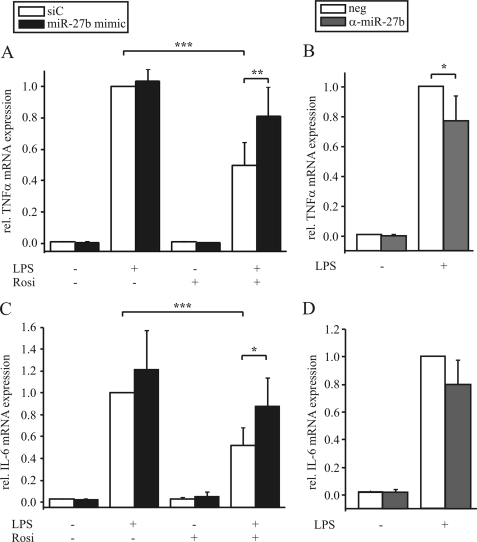

Physiological Relevance of the miR-27b-mediated PPARγ1 Decrease

As PPARγ is well described for its anti-inflammatory effects by reducing the expression of different cytokines (12), we analyzed the effect of miR-27b on LPS-induced expression of TNFα and IL-6. Therefore we modulated miR-27b expression by either transfecting macrophages with the miR-27b mimic or anti-miR-27b. Whereas pretreating macrophages with rosiglitazone for 1 h reduced LPS-induced expression of TNFα and IL-6, overexpression of miR-27b relieved rosiglitazone-mediated inhibition (Fig. 7, A and C). Inhibiting miR-27b by transfecting cells with anti-miR-27b lowered TNFα and IL-6 induction upon LPS exposure in comparison to the controls (Fig. 7, B and D).

FIGURE 7.

Modulating miR-27b expression affects TNFα and IL-6 expression. Primary human macrophages were transfected with (A, C) 10 pmol miR-27b mimic or (B, D) 150 pmol anti-miR-27b or negative controls (siC or neg.), respectively and prestimulated with 1 μm rosiglitazone (Rosi, (A, C)) for 1 h followed by treatment with 1 μg/ml LPS for 3 h. TNFα and IL-6 mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. Data represent mean values ± S.E., n ≥ 5. Statistics were analyzed with the paired Student's t test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Considering the anti-inflammatory potential of PPARγ, its activation emerged as a strategy to attenuate acute and chronic inflammatory diseases (17, 23–25). Synthetic PPARγ agonists, known as thiazolidinediones (20), already entered phase III clinical trials for the treatment of Alzheimer disease and phase II trials for ulcerative colitis (24, 26). Remarkably, disease progression is often accompanied by decreased PPARγ expression, with molecular mechanisms being ill-defined. For this reason we analyzed pathways decreasing PPARγ expression during the onset of inflammation.

LPS, a classical pro-inflammatory stimulus time-dependently reduced PPARγ1 mRNA and protein amounts in macrophages, which is in line with the work of Necela et al. (22) showing a reduction of PPARγ mRNA in murine RAW264.7 macrophages. Prolonged LPS exposure allowed to recover PPARγ mRNA to almost basal levels after 24 h. Accordingly, treating macrophages with LPS for 24 h (27) or LPS and interferon γ for 15 h even provoked PPARγ transactivation (13).

Investigating PPARγ promoter activity, we ruled out transcriptional regulation. In fact, reduced promoter 1 activity appears to be negligible because this transcript variant was only minimally expressed in fully differentiated macrophages. Moreover, a minor reduction of promoter 3 activity after 6 h of LPS exposure unlikely accounts for a 90% decrease of mRNA. Therefore, we determined PPARγ1 mRNA stability. Experiments with the transcription inhibitor DRB implied PPARγ1 mRNA destabilization upon LPS exposure. This contrasts the work of Necela et al. (22) who observed no effect of LPS on mRNA stability using actinomycin D to block transcription. Using actinomycin D we observed similar results. This could result from effects of actinomycin D on mRNA stability by inducing translocalization of ARE-binding proteins (28), which is a major regulatory event for activation of several ARE-binding proteins such as HuR, AUF-1 or tristetraprolin (29–31). Moreover, previous studies revealed that actinomycin D and DRB can differently affect estimation of mRNA half-lives (32).

The use of 3′-UTR reporter constructs is an established method to verify potential destabilization mechanisms. Luciferase assays with a pGL3-PPARγ-3′-UTR construct demonstrated the importance of the PPARγ-3′-UTR, because LPS significantly reduced luciferase activity. In silico analysis showed several ARE 1 (AUUUA) and ARE 4 (12-mer A/U, max. one mismatch) sites (33) as well as a potential miR-27a/b binding site. Deletion or mutation of the miR-27 site within the PPARγ-3′-UTR reporter construct substantiated a miR-27b-dependent mRNA decay. In line, we observed a 2.3-fold increase of miR-27b in response to LPS, which is comparable to the induction of miR-146a after 2 h of LPS exposure in THP-1 cells (6). In addition, mRNA from mouse lung extracts showed an increased miR-27a and -b expression 3 h after LPS exposure (34). Nevertheless, the role of miR-27a/b during inflammation in macrophages remained obscure.

Several diseases are associated with dysregulated miRNA expression. miR-146a and miR-155 have been implicated in the development of rheumatoid arthritis, likely by regulating components of the inflammatory response (35, 36). These miRNAs are induced upon NFκB transactivation (6, 37, 38). We also observed that induction of miR-27b is at least partially NFκB-dependent. Inhibition of NFκB with Bay11–7082 abrogated LPS-mediated PPARγ1 mRNA decay, which is corroborated by the work of Necela et al. (22). In their studies several NFκB inhibitors prevented the LPS-induced PPARγ decrease, although detailed mechanism remained unclear. We conclude that the NFκB-dependent PPARγ1 mRNA decrease results at least in part from the NFκB-dependent induction of miR-27b upon LPS exposure. Inhibition of miR-27b prevented PPARγ1 mRNA decay and thus, points to mRNA destabilization rather than translational control by miR-27b. The potential of miR-27 to decrease PPARγ mRNA is acknowledged by Lin et al. During adipogenic differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells microarray analysis revealed a reduced expression of miR-27a and -b, which was correlated with an increase of PPARγ. In line with our observations, transfection of these cells with miR-27a and -b reduced PPARγ mRNA (39). Moreover, Karbiener et al. (40) recently demonstrated that miR-27b abundance decreased during adipogenesis of human adipose-derived stem cells, suggesting anti-adipogenic effects of miR-27b because of suppression of PPARγ.

Taking into consideration that LPS further decreased PPARγ1 mRNA despite its reduction by miR-27b overexpression suggests additional regulatory mechanisms likely by an ARE-binding protein. Moreover, as a 2-fold induction of miR-27b reduced PPARγ1 mRNA to a lower extent than LPS but overexpression of miR-27b did not alter mRNA stability, points to additional regulatory mechanisms. Nevertheless, abrogating a luciferase decrease upon LPS by deletion of the miR-27 binding side or mutation of the seed region revealed that miR-27b is a prerequisite for LPS-induced PPARγ mRNA destabilization.

Because PPARγ was also reduced upon TLR1/2 and 5 activation (6), in response to TNFα (41) and phytohemagglutinin (42), we suggest that inflammatory signals in general provoke a mRNA decay. This assumption is supported by the notion that NFκB, a major inflammatory transcription factor, is involved. In line, stimulation with TNFα reduced PPARγ1 levels likely by miR-27b induction, while IFNγ (not activating NFκB) rather induced PPARγ1 expression.

Interestingly, several inflammatory diseases are not only associated with impaired PPARγ expression but also NFκB activation. Patients with multiple sclerosis exhibit enhanced expression of inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and show an impaired PPARγ expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (42). In ulcerative colitis (43), inflammatory skin disorders (44) and Alzheimer disease (45) PPARγ expression is also reduced.

PPARγ is well established for its anti-inflammatory effects in attenuating the production of pro-inflammatory mediators (12). Thus, overexpressing or inhibiting miR-27b affected TNFα and IL-6 mRNA amount. Studies in PPARγ knock-out macrophages supported the importance of PPARγ, because these cells expressed higher amounts of pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 (22). We suggest that decreased PPARγ expression prolongs inflammation and thus, attenuates resolution of inflammation. Therefore, understanding molecular mechanisms of a PPARγ decrease may provide options for new therapeutic approaches during chronic inflammation.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Br 999, FOG 784, Excellence Cluster Cardiopulmonary System), Sander Foundation, and LOEWE (LiFF and OSF).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- UTR

- untranslated region

- ARE

- AU-rich element, DRB, 5–6 dichloro-1-β-ribofuranosyl-benzimidazole

- IFNγ

- interferon γ

- IL

- interleukin

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- miRNA

- microRNA

- NFκB

- nuclear factor κB

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- PPARγ

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- TNF

- tumor necrosis factor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Serhan C. N., Chiang N., Van Dyke T. E. (2008) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 349–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoecklin G., Anderson P. (2006) Adv. Immunol. 89, 1–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winter J., Jung S., Keller S., Gregory R. I., Diederichs S. (2009) Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 228–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eulalio A., Huntzinger E., Izaurralde E. (2008) Cell 132, 9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheedy F. J., O'Neill L. A. (2008) Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67, iii50–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taganov K. D., Boldin M. P., Chang K. J., Baltimore D. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 12481–12486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elbrecht A., Chen Y., Cullinan C. A., Hayes N., Leibowitz M., Moller D. E., Berger J. (1996) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 224, 431–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fajas L., Auboeuf D., Raspé E., Schoonjans K., Lefebvre A. M., Saladin R., Najib J., Laville M., Fruchart J. C., Deeb S., Vidal-Puig A., Flier J., Briggs M. R., Staels B., Vidal H., Auwerx J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 18779–18789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fajas L., Fruchart J. C., Auwerx J. (1998) FEBS Lett. 438, 55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ricote M., Huang J., Fajas L., Li A., Welch J., Najib J., Witztum J. L., Auwerx J., Palinski W., Glass C. K. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7614–7619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li M., Pascual G., Glass C. K. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 4699–4707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ricote M., Li A. C., Willson T. M., Kelly C. J., Glass C. K. (1998) Nature 391, 79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Von Knethen A., Brüne B. (2001) FASEB J. 15, 535–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johann A. M., von Knethen A., Lindemann D., Brüne B. (2006) Cell Death Differ. 13, 1533–1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serhan C. N., Savill J. (2005) Nat. Immunol. 6, 1191–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi M., Thomassen M. J., Rambasek T., Bonfield T. L., Raychaudhuri B., Malur A., Winkler A. R., Barna B. P., Goldman S. J., Kavuru M. S. (2005) Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 95, 468–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubuquoy L., Rousseaux C., Thuru X., Peyrin-Biroulet L., Romano O., Chavatte P., Chamaillard M., Desreumaux P. (2006) Gut 55, 1341–1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Knethen A., Soller M., Tzieply N., Weigert A., Johann A. M., Jennewein C., Köhl R., Brüne B. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 176, 681–694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tugwood J. D., Issemann I., Anderson R. G., Bundell K. R., McPheat W. L., Green S. (1992) EMBO J. 11, 433–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yki-Järvinen H. (2004) N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 1106–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim D. K., Yamaguchi Y., Wada T., Handa H. (2001) Mol. Cells 11, 267–274 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Necela B. M., Su W., Thompson E. A. (2008) Immunology 125, 344–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drew P. D., Xu J., Racke M. K. (2008) PPAR Res. 2008:627463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landreth G. (2007) Curr. Alzheimer Res. 4, 159–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dushkin M. I., Khoshchenko O. M., Chasovsky M. A., Pivovarova E. N. (2009) Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 147, 345–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis J. D., Lichtenstein G. R., Deren J. J., Sands B. E., Hanauer S. B., Katz J. A., Lashner B., Present D. H., Chuai S., Ellenberg J. H., Nessel L., Wu G. D. (2008) Gastroenterology 134, 688–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendes Sdos S., Candi A., Vansteenbrugge M., Pignon M. R., Bult H., Boudjeltia K. Z., Munaut C., Raes M. (2009) Cell Signal. 21, 1109–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sengupta S., Jang B. C., Wu M. T., Paik J. H., Furneaux H., Hla T. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25227–25233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loflin P., Chen C. Y., Shyu A. B. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1884–1897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng S. S., Chen C. Y., Xu N., Shyu A. B. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 3461–3470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor G. A., Thompson M. J., Lai W. S., Blackshear P. J. (1996) Mol. Endocrinol. 10, 140–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrold S., Genovese C., Kobrin B., Morrison S. L., Milcarek C. (1991) Anal. Biochem. 198, 19–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharova L. V., Sharov A. A., Nedorezov T., Piao Y., Shaik N., Ko M. S. (2009) DNA Res. 16, 45–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moschos S. A., Williams A. E., Perry M. M., Birrell M. A., Belvisi M. G., Lindsay M. A. (2007) BMC Genomics 8, 240–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanczyk J., Pedrioli D. M., Brentano F., Sanchez-Pernaute O., Kolling C., Gay R. E., Detmar M., Gay S., Kyburz D. (2008) Arthritis Rheum. 58, 1001–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakasa T., Miyaki S., Okubo A., Hashimoto M., Nishida K., Ochi M., Asahara H. (2008) Arthritis Rheum. 58, 1284–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tili E., Michaille J. J., Cimino A., Costinean S., Dumitru C. D., Adair B., Fabbri M., Alder H., Liu C. G., Calin G. A., Croce C. M. (2007) J. Immunol. 179, 5082–5089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vigorito E., Perks K. L., Abreu-Goodger C., Bunting S., Xiang Z., Kohlhaas S., Das P. P., Miska E. A., Rodriguez A., Bradley A., Smith K. G., Rada C., Enright A. J., Toellner K. M., Maclennan I. C., Turner M. (2007) Immunity 27, 847–859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin Q., Gao Z., Alarcon R. M., Ye J., Yun Z. (2009) FEBS J. 276, 2348–2358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karbiener M., Fischer C., Nowitsch S., Opriessnig P., Papak C., Ailhaud G., Dani C., Amri E. Z., Scheideler M. (2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 390, 247–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou M., Wu R., Dong W., Jacob A., Wang P. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 294, R84–R92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klotz L., Schmidt M., Giese T., Sastre M., Knolle P., Klockgether T., Heneka M. T. (2005) J. Immunol. 175, 4948–4955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dubuquoy L., Jansson E. A., Deeb S., Rakotobe S., Karoui M., Colombel J. F., Auwerx J., Pettersson S., Desreumaux P. (2003) Gastroenterology 124, 1265–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sertznig P., Seifert M., Tilgen W., Reichrath J. (2008) Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 9, 15–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sastre M., Dewachter I., Rossner S., Bogdanovic N., Rosen E., Borghgraef P., Evert B. O., Dumitrescu-Ozimek L., Thal D. R., Landreth G., Walter J., Klockgether T., van Leuven F., Heneka M. T. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 443–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.