Abstract

Myocardial hypertrophy is frequently associated with poor clinical outcomes including the development of cardiac systolic and diastolic dysfunction and ultimately heart failure. To prevent cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure, it is necessary to identify and characterize molecules that may regulate the hypertrophic program. Our present study reveals that nuclear factor of activated T cells c3 (NFATc3) and myocardin constitute a hypertrophic pathway that can be targeted by miR-9. Our results show that myocardin expression is elevated in response to hypertrophic stimulation with isoproterenol and aldosterone. In exploring the molecular mechanism by which myocardin expression is elevated, we identified that NFATc3 can bind to the promoter region of myocardin and transcriptionally activate its expression. Knockdown of myocardin can attenuate hypertrophic responses triggered by NFATc3, suggesting that myocardin can be a downstream mediator of NFATc3 in the hypertrophic cascades. MicroRNAs are a class of small noncoding RNAs that mediate post-transcriptional gene silencing. Our data reveal that miR-9 can suppress myocardin expression. However, the hypertrophic stimulation with isoproterenol and aldosterone leads to a decrease in the expression levels of miR-9. Administration of miR-9 could attenuate cardiac hypertrophy and ameliorate cardiac function. Taken together, our data demonstrate that NFATc3 can promote myocardin expression, whereas miR-9 is able to suppress myocardin expression, thereby regulating cardiac hypertrophy.

Keywords: Cardiac Hypertrophy, Heart, Metabolism, MicroRNA, Signal Transduction

Introduction

Myocardial hypertrophy is a physiological and compensatory response that is frequently associated with poor clinical outcomes, including the development of cardiac systolic and diastolic dysfunction and ultimately heart failure as well as sudden death (1–6). To prevent cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure, it is necessary to identify and characterize molecules that may regulate the hypertrophic program.

Calcineurin is a serine/threonine protein phosphatase. It is able to induce cardiac hypertrophy (7, 8). For example, overexpression of the constitutively active calcineurin A results in cardiac hypertrophy (9). It has been shown that cyclosporin A and FK506 prevent cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting calcineurin activation (10–13). Calcineurin elicits the hypertrophic effect by targeting the nuclear factor of activated T cells c3 (NFATc3).2 Upon phosphorylation in serine residues in the N terminus, NFATc3 is located in the cytoplasm. Calcineurin can dephosphorylate NFATc3, resulting in its nuclear localization (14, 15). It has been demonstrated that calcineurin and NFATc3 constitute an important pathway in the cardiac hypertrophic machinery (16, 17). Nevertheless, the downstream targets of NFATc3 in the hypertrophic machinery still remain to be elucidated.

Myocardin is a transcriptional cofactor expressed at a relatively low level in cardiomyocytes under physiological conditions. However, it can be up-regulated by hypertrophic stimulation and consequently mediate hypertrophic signals. For example, overexpression of myocardin can induce cardiac hypertrophy (18). Myocardin can mediate the hypertrophic signal of a variety of stimuli such as phenylephrine, endothelin-1, and serum (18). Given the important role of myocardin in hypertrophy, the upstream signals that control its expression remain largely unknown. In particular, it is not yet clear whether myocardin is a target of NFATc3 in the hypertrophic pathway.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small noncoding RNAs that mediate post-transcriptional gene silencing (19, 20). Growing evidence has shown that miRNAs are involved in the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy. For example, inhibition of miR-133 causes significant cardiac hypertrophy (21). In contrast, miR-208 is required for cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, fibrosis, and expression of myosin heavy chain in response to stress and hypothyroidism (22). The specific overexpression of miR-195 in mouse heart results in severe cardiac hypertrophy (23). Overexpression of miR-214 in the cardiomyocytes also causes significant hypertrophy (23). Thus, it appears that miRNAs play multiple and essential roles in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. Hitherto, it is not yet clear which miRNAs can regulate myocardin and whether targeting myocardin by miRNAs can alter cardiac hypertrophic processes.

Our present study reveals that myocardin is a transcriptional target of NFATc3, and it can meditate the hypertrophic signal of NFATc3. We further identified that miR-9 is able to regulate myocardin expression. However, miR-9 expression is down-regulated upon hypertrophic stimulation with isoproterenol and aldosterone. Administration of miR-9 can attenuate the expression levels of myocardin and cardiac hypertrophy. Our data provide critical information for future studies to establish therapeutic approaches for cardiac hypertrophy by employing miRNAs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cardiomyocyte Culture and Treatment

Cardiomyocytes were isolated from 1–2-day-old Wistar rats as we described (24). Briefly, after dissection hearts were washed and minced in HEPES-buffered saline solution. The tissues were then dispersed in a series of incubations at 37 °C in HEPES-buffered saline solution containing 1.2 mg/ml pancreatin and 0.14 mg/ml collagenase (Worthington). After centrifugation the cells were resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 (Invitrogen) containing 5% heat-inactivated horse serum, 0.1 mm ascorbate, insulin-transferring-sodium selenite medium supplement (Sigma), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.1 mm bromodeoxyuridine. The dissociated cells were preplated at 37 °C for 1 h. The cells were then diluted to 1 × 106 cells/ml and plated in 10 μg/ml laminin-coated different culture dishes according to the specific experimental requirements. The cells were treated with isoproterenol (Iso) at 10 μm or aldosterone (Aldo) at 1 μm, except as otherwise indicated elsewhere.

Adenoviral Constructions and Infection

Adenoviral vector encoding the constitutively active form of NFATc3 (ΔNFATc3) was kindly provided by Dr. Michael C. Naski (25). The adenovirus containing β-galactosidase (β-gal) is as we described elsewhere (26). The rat NFATc3 RNA interference (RNAi)-A target sequence is 5′-AAATGTCAAGGGGGTCATA-3′. A scramble form without any other match in the rat genomic sequence was used as a control (5′-ACTGATGTGACGAGAGATA-3′). NFATc3 RNAi-B target sequence is 5′-GCTGCTGCACGATTTACTC-3′. The scramble NFATc3 RNAi-B target sequence is 5′-TCAGTCATGTACGTCTCGC-3′. The rat myocardin RNAi-A target sequence is 5′-GGTCAGAAACAGATCGGAC-3′. The scramble myocardin RNAi-A target sequence is 5′-AGCCTAAGTCAAGGCAGAG-3′. The myocardin RNAi-B target sequence is 5′-AGATCCATTCCAACTGCTC-3′. The scramble myocardin RNAi-B target sequence is 5′-TCAGTCACTACTCACTGAC-3′. The adenoviruses harboring NFATc3 RNAi or myocardin RNAi were constructed using the pSilencerTM adeno 1.0 cytomegalovirus system (Ambion) according to the instructions. All of the constructs were amplified in HEK293 cells. Adenoviral infection of cardiomyocytes was performed as we described previously (27).

Determinations of Cell Surface Areas, Sarcomere Organization, and Protein/DNA Ratio

The cell surface area of F-actin-stained cells or unstained cells was measured as we described (27). 100–200 cardiomyocytes in 30–50 fields were examined in each group. For staining of filamentous actin, the cardiomyocytes were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. The cells were dehydrated with acetone for 3 min and treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min. They were then stained with a 50 μg/ml fluorescent Phalloidin-TRITC conjugate (Sigma) for 45 min at room temperature and visualized by a laser confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 510 META). To measure the protein/DNA ratio, the total protein and DNA contents were analyzed as we described (24).

Immunoblot and Immunofluorescence

Immunoblot was performed as we described (28). In brief, the cells were lysed for 1 h at 4 °C in a lysis buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 2 mm EDTA, 3 mm EGTA, 2 mm dithiothreitol, 250 mm sucrose, 0.1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1% Triton X-100, and a protease inhibitor mixture). The samples were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Equal protein loading was controlled by Ponceau red staining of membranes. The blots were probed using antibodies. The anti-myocardin antibody and the anti-NFATc3 antibody were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The anti-phospho-NFATc3 antibody was from Abcam. Immunofluorescence was performed as we described (29). The samples were imaged using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510 META).

Constructions of Rat Myocardin Promoter and Its Mutant

Myocardin promoter was amplified from rat genome using PCR. The forward primer was 5′-CAGCTCAGAGGTAGATGGATA-3′. The reverse primer was 5′-AGGAGTGTCATGGTGAGTCTC-3′. The promoter fragment was finally cloned into the vector pGL4.17 (Promega). The introduction of mutations in the putative NFATc3-binding site was performed with the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) using the wild type vector as a template. The construct was sequenced to check that only the desired mutations had been introduced.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay was performed as we described (24). In brief, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and incubated for 10 min with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature. The cross-linking was quenched with 0.1 m glycine for 5 min. The cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and lysed for 1 h at 4 °C in a lysis buffer. The cell lysates were sonicated into chromatin fragments with an average length of 500–800 bp as assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The samples were precleared with protein A-agarose (Roche Applied Science) for 1 h at 4 °C on a rocking platform, and 5 μg of specific antibodies were added and rocked overnight at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitates were captured with 10% (v/v) protein A-agarose for 4 h. Before use, protein A-agarose was blocked twice at 4 °C with salmon sperm DNA (2 μg/ml) overnight. DNA fragments were purified with a QIAquick spin kit (Qiagen). The purified DNA was used as a template and amplified with the following primer sets: 5′-ATCGGAGAGAGATGCAGAAGG-3′; 5′-GGGAGTCAGAAACAGGTCTC-3′.

Luciferase Assay

Luciferase activity assay was performed using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were seeded in 24-well plates. They were cotransfected with the expression vectors, the luciferase reporter constructs, and the Renilla luciferase plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Each well contained 0.2 μg of luciferase reporter plasmids, 0.2 μg of expression vectors, 2.5 ng of Renilla luciferase plasmids, respectively. The cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity 24 h after transfection. Twenty μl of protein extracts were analyzed in a luminometer. Firefly luciferase activities were normalized to Renilla luciferase activity.

For myocardin 3′-UTR luciferase assay, the cells were cotransfected with the plasmid constructs of 150 ng/well of pGL3-myocardin-3′-UTR, 300 ng/well of miR-9, and 25 pmol of either miR-9 antagomir or antagomir negative control (antagomir-NC) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 48 h after transfection, the cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription (qRT)-PCR

Stem-loop qRT-PCR for mature miR-9 was performed as described (30) on an Applied Biosystems AB 7000 real time PCR system. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent. After DNase I (Takara, Japan) treatment, RNA was reverse transcribed with reverse transcriptase (ReverTra Ace®; Toyobo). qRT-PCR for myocardin was performed as we described (24). In brief, total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen). RNA was reverse transcribed using oligo(dT). Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (ReverTra Ace®) was from Toyobo. The samples were run in triplicate using the Applied Biosystems (ABI) 7000 sequence detector according to the manufacturer's instructions. The results were standardized to control values of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The sequences of myocardin primers were: forward, 5′-GCAGCAGATGCATTTGCCTTTG-3′, and reverse, 5′-GCCTCAGTGGATTTGATGTCTG-3′; β-MHC forward, 5′-AACCTGTCCAAGTTCCGCAAGGTG-3′, and reverse, 5′-GAGCTGGGTAGCACAAGAGCTACT-3′; atrial natriuretic peptide forward, 5′-CTCCGATAGATCTGCCCTCTTGAA-3′, and reverse, 5′-GGTACCGGAAGCTGTTGCAGCCTA-3′; and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase forward, 5′-GCTAACATCAAATGGGGTGATGCTG-3′, and reverse, 5′-GAGATGATGACCCTTTTGGCCCCAC-3′. The specificity of the PCR amplification was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Preparations of the Luciferase Construct of Myocardin 3′-UTR

Myocardin 3′-UTR was amplified by PCR. The forward primer was 5′-GAGCTCAGTGGGAATTCAATG-3′. The reverse primer was 5′-TCCCTCTGCTCACAATAAGAA-3′. To produce mutated 3′-UTR, the mutations (wild type 3′-UTR, 5′-CCAAAGA-3′; mutated 3′-UTR, 5′-CAGGCGA-3′) was generated using QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The constructs were sequence-verified. Wild type and mutated 3′-UTRs were subcloned into the pGL3 vector (Promega) immediately downstream of the stop codon of the luciferase gene.

Preparation of miR-9 Expression Construct

miR-9 was synthesized by PCR using rat genomic DNA as the template. The upstream primer was 5′-TTCTGCACGGAGGTGGAGGGA-3′; the downstream primer was 5′-TTTCTTCCCAGCTGAGCAG-3′. The PCR fragment was finally cloned into the Adeno-XTM expression system (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To generate miR-9 control, a mutated miR-9 was produced as described (31). The mutations were generated using a QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The constructs were sequence-verified.

Transfection of miR-9 Mimic and Antagomir

miR-9 mimic, the mimic negative control (mimic-NC), miR-9 antagomir, and the antagomir negative control (antagomir-NC) were purchased from GenePharma Co. Ltd. miR-9 mimics are double-stranded RNA oligonucleotides. The cells were transfected with the mimic or the mimic-NC at 50 nm or with antagomir or antagomir-NC at 50 nm. The transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Animal Experiments

Adult male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old) were purchased from the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing, China). Food and water were freely available throughout the experiments. The experiments were conducted according to a protocol approved by the Institute Animal Care Committee. The mice were infused with Iso (30 mg/kg dissolved in 0.9% NaCl) or Aldo (10 μg/kg dissolved in 0.5% ethanol, 0.9% NaCl). Saline-infused mice served as controls. To induce hypertrophy, mice were infused with Iso for 1 week. For in vivo transfer of miR-9 mimic, the mice were infused with Iso and miR-9 mimic (30 mg/kg) at the same time. Mimic-NC served as a negative control and was subjected to the same procedures as mimic. The infusions were executed with implanted osmotic minipumps (Alzet model 2001; Alza Corp.).

Histological Analysis

Histological analysis of the hearts was carried out as we described (26). Briefly, the hearts were excised, fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned into 7-μm slices, and stained with hematoxyline-eosin. To measure the cross-sectional area of the cardiomyocytes, the sections were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (Sigma) according to the method described previously (32).

Echocardiographic Assessment of Cardiac Dimensions and Function

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed on lightly anesthetized mice using a Vevo 770 high resolution system (Visualsonics, Toronto, Canada) equipped with a 40-MHz RMV 704 scanhead. Two-dimensional guided M-mode tracings were recorded in both parasternal long and short axis views at the level of papillary muscles. Ventricular parameters including diastolic interventricular septal thickness, diastolic posterior wall thickness, and systolic left ventricular internal diameters were measured. Fractional shortening was calculated with the established standard equation. All of the measurements were made from more than three beats and averaged.

Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as the means ± S.E. The statistical comparison among different groups was performed by one-way analysis of variance. Paired data were evaluated by Student's t test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Iso and Aldo Induce an Increase in the Levels of Myocardin Expression and a Decrease in the Levels of Phosphorylated NFATc3 in Vitro and in Vivo

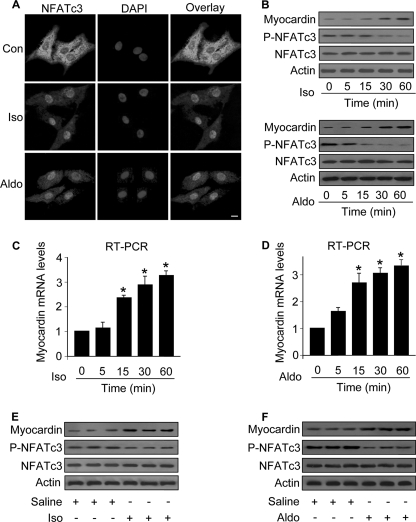

NFATc3 is able to mediate the hypertrophic signals, but its downstream targets remain to be further elucidated. Myocardin has been shown to be a pro-hypertrophic protein (18). We detected the expression as well as the phosphorylation levels of NFATc3 in cells treated with Iso or Aldo. NFATc3 is predominantly distributed in the cytoplasm in the control cells without treatment. Iso and Aldo led to NFATc3 translocation to the nuclei (Fig. 1A). Immunoblotting results showed that the levels of phosphorylated NFATc3 were reduced. Concomitantly, myocardin levels were elevated (Fig. 1B). We analyzed the mRNA levels of myocardin and observed that its levels were increased in response to the treatment with Iso (Fig. 1C) and Aldo (Fig. 1D). To know the levels of NFATc3 and myocardin in the animal model, we treated the mice with Iso and Aldo. The phosphorylated levels of NFATc3 were reduced, whereas the expression levels of myocardin were elevated in the hearts exposed to Iso (Fig. 1E) or Aldo (Fig. 1F). Thus, it appears that both NFATc3 and myocardin are altered upon treatment with Iso and Aldo.

FIGURE 1.

Iso and Aldo induce an increase in myocardin expression levels and a decrease in the levels of phosphorylated NFATc3 in vitro and in vivo. A, Iso and Aldo induce NFATc3 redistributions from the cytoplasm to nuclei. The neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were treated with 10 μm Iso or 1 μm Aldo. 1 h after treatment the cells were collected for the analysis of NFATc3 by immunofluorescent staining. The cell nuclei were stained by 4′,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Bar, 10 μm. B–D, the treatment with Iso and Aldo leads to an increase in myocardin expression levels and a decrease in the levels of phosphorylated NFATc3 (P-NFATc3). Cardiomyocytes were treated with 10 μm Iso or 1 μm Aldo. The cells were harvested at the indicated time for the analysis of myocardin protein levels, phosphorylated, and total NFATc3 levels by immunoblot (B) or myocardin mRNA levels by real time PCR (C and D). *, p < 0.05 versus control. E and F, Iso and Aldo treatment induces an elevation in myocardin levels and a reduction in the phosphorylated NFATc3 (P-NFATc3) in the animal model. C57BL/6 mice were infused with Iso or Aldo as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The levels of myocardin, P-NFATc3, and total NFATc3 in the hearts were analyzed by immunoblotting. A representative blot is shown. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. Con, control.

Myocardin Participates in Conveying the Hypertrophic Signal of Iso and Aldo

The elevation of myocardin levels in response to the treatment with Iso and Aldo led us to consider whether it plays a functional role in hypertrophy induced by Iso and Aldo. The RNAi construct could significantly reduce the expression levels of myocardin (Fig. 2A). Knockdown of myocardin led to a reduction in cell surface areas, protein/DNA ratio, and β-MHC levels upon treatment with Iso (Fig. 2B). A similar result was obtained in cells treated with Aldo (Fig. 2C). Sarcomere organization is a dominant marker of hypertrophy. As shown in Fig. 2D, knockdown of myocardin could inhibit sarcomere organization induced by Iso and Aldo. To further confirm the role of myocardin in Iso-induced hypertrophy, we employed another RNAi construct of myocardin, and this construct could reduce myocardin expression levels (Fig. 2E) and the cell surface areas (Fig. 2F). These data indicate that myocardin is necessary for Iso and Aldo to initiate hypertrophy.

FIGURE 2.

Myocardin participates in mediating the hypertrophic signals of Iso and Aldo. A, knockdown of myocardin expression. Cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviral myocardin-RNAi-A (myo-RNAi-A) or its scramble form (myo-S-RNAi-A) at a moi of 80. 48 h after infection the cells were harvested for the analysis of myocardin levels by immunoblot. B, knockdown of myocardin reduces hypertrophic responses induced by Iso. Cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviral myocardin-RNAi-A or its scramble form (myocardin-S-RNAi-A) at a moi of 80. 24 h after infection the cells were treated with Iso. Analysis of myocardin levels by immunoblot was performed 1 h after Iso treatment (top panels). Hypertrophy was assessed by cell surface area measurement, protein/DNA ratio and β-MHC levels analyzed by qRT-PCR. *, p < 0.05 versus control; #, p < 0.05 versus Iso alone. C, myocardin is necessary for Aldo to induce hypertrophy. Cardiomyocytes were treated as described for B, except that Aldo was employed. *, p < 0.05 versus control; #, p < 0.05 versus Aldo alone. D, representative photos show sarcomere organization. Cardiomyocytes were treated as described for B or C. Bar, 20 μm. E, knockdown of myocardin expression. Cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviral myocardin-RNAi-B (myo-RNAi-B) or its scramble form (myo-S-RNAi-B) at a moi of 100. 48 h after infection the cells were harvested for the analysis of myocardin levels by immunoblot. F, knockdown of myocardin reduces cell surface area induced by Iso. Cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviral myocardin-RNAi-B or its scramble form (myocardin-S-RNAi-B) at a moi of 100. 24 h after infection cells were treated with Iso. Analysis of myocardin levels by immunoblot was performed 1 h after Iso treatment (top panels). Hypertrophy was assessed by cell surface area measurement (bottom panel). *, p < 0.05 versus control; #, p < 0.05 versus Iso alone. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

NFATc3 Can Transcriptionally Target Myocardin

The simultaneous alterations in the levels of NFATc3 phosphorylation and myocardin expression encouraged us to test whether these two events are related. Enforced expression of the constitutively active form of NFATc3 (ΔNFATc3) could induce an increase in the levels of myocardin protein (Fig. 3A) and mRNA (Fig. 3B). We analyzed the promoter region of myocardin and observed that it contains one NFATc3 consensus binding site from −1734 to −1717 (Fig. 3C). Subsequently, we tested whether there is an association between NFATc3 and the promoter of myocardin. Iso and Aldo treatment resulted in a time-dependent increase in the association levels between NFATc3 and myocardin promoter (Fig. 3D). We analyzed the promoter activity of myocardin in the presence and absence of ΔNFATc3 and observed an elevated myocardin promoter activity upon stimulation with ΔNFATc3. Mutations in the binding site of myocardin promoter led to a reduction of promoter activity in response to ΔNFATc3 stimulation (Fig. 3E). We tested whether myocardin promoter can be stimulated by the endogenous NFATc3. Iso (Fig. 3F) or Aldo (Fig. 3G) could induce an increase in myocardin promoter activity that was attenuated by knockdown of NFATc3. Taken together, it appears that NFATc3 can transcriptionally up-regulate myocardin expression.

FIGURE 3.

NFATc3 transcriptionally targets myocardin. A and B, the constitutively active form of NFATc3 (ΔNFATc3) stimulates myocardin expression at protein and mRNA levels. Cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviral β-gal orΔNFATc3 at a moi of 50. The cells were harvested at the indicated time for the analysis of myocardin protein levels by immunoblot (A) or myocardin mRNA levels by real time PCR (B). *, p < 0.05 versus control. C, myocardin promoter contains a potential NFATc3-binding site. The NFATc3 site is shown between −1734 and −1717 bp. The promoter of myocardin was synthesized and linked to luciferase (Luc) reporter gene. The mutations were introduced to the binding site (BS). D, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis of in vivo NFATc3 binding to the promoter. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay was performed using cardiomyocytes treated with or without 10 μm Iso and 1 μm Aldo. The anti-myocardin antibody was used as a negative control. E, NFATc3 activates myocardin promoter activity. Cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviruses harboring β-gal or ΔNFATc3. 24 h after infection cells were transfected with the constructs of the empty vector (pGL-4.17), the wild type promoter (wt) or the promoter with mutations in the binding site (mBS), respectively. Firefly luciferase activities were normalized to Renilla luciferase activities. F and G, knockdown of endogenous NFATc3 inhibits the elevation of myocardin promoter activity induced by Iso or Aldo. Cardiomyocytes were infected with adenovirus harboring NFATc3 RNAi or its scramble form (NFATc3-S-RNAi) at a moi of 100. 24 h after infection cells were transfected with the construct of wild type promoter. Cardiomyocytes were treated with 10 μm Iso (F) or 1 μm Aldo (G). Firefly luciferase activities were normalized to Renilla luciferase activities. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

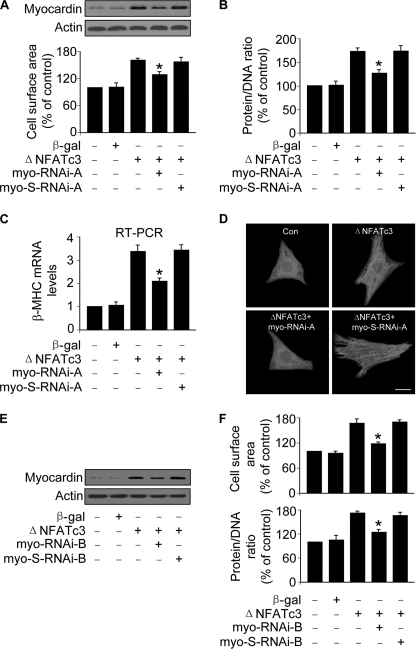

Myocardin Conveys the Hypertrophic Signal of NFATc3

To understand whether the stimulation of myocardin by NFATc3 plays a functional role, we tested whether NFATc3 is able to induce hypertrophic responses upon knockdown of myocardin. The constitutively active form of NFATc3 induced an increase in cell surface areas attenuated by knockdown of myocardin (Fig. 4A). Knockdown of myocardin led to a reduction in the protein/DNA ratio (Fig. 4B) and β-MHC expression levels (Fig. 4C) upon stimulation with the constitutively active form of NFATc3. Sarcomere organization was inhibited by knockdown of myocardin (Fig. 4D). We employed another myocardin RNAi construct, and a similar result was obtained (Fig. 4, E and F). Thus, it appears that NFATc3 and myocardin constitute an axis in the hypertrophic machinery.

FIGURE 4.

Myocardin is able to convey the hypertrophic signal of NFATc3. A–D, cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviral myocardin-RNAi-A (myo-RNAi-A) or its scramble form (myo-S-RNAi-A) at a moi of 80. 24 h after infection cells were infected with adenoviruses harboring β-gal or ΔNFATc3 at a moi of 50. Myocardin expression levels analyzed by immunoblot (top panels) and cell surface areas (bottom panel) are shown in A. Protein/DNA ratio analysis is shown in B. The expression levels of β-MHC analyzed by qRT-PCR were shown in C. *, p < 0.05 versus ΔNFATc3 alone. Representative photos show sarcomere organization (D). Bar, 20 μm. E and F, cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviral myocardin-RNAi-B (myo-RNAi-B) or its scramble form (myo-S-RNAi-B) at a moi of 100. 24 h after infection cells were infected with adenoviruses harboring β-gal or ΔNFATc3 at a moi of 100. Myocardin expression levels analyzed by immunoblot are shown in E. Cell surface area measurement and protein/DNA ratio analysis are shown in F. *, p < 0.05 versus ΔNFATc3 alone. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. Con, control.

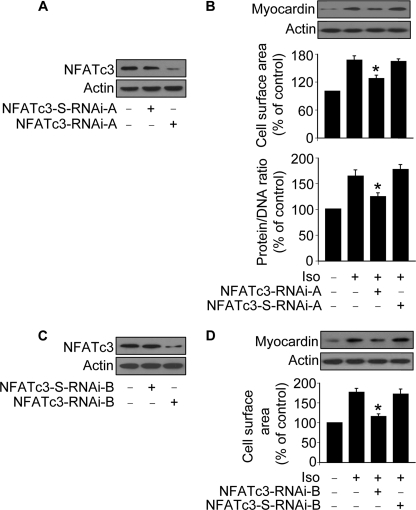

NFATc3 Regulates Myocardin in the Hypertrophic Pathways of Iso and Aldo

We asked whether NFATc3 and myocardin have a link in the hypertrophic pathway of Iso and Aldo. To address this question, we produced two RNAi constructs of NFATc3. NFATc3-RNAi-A could significantly reduce NFATc3 expression levels (Fig. 5A). Iso treatment induced an elevated protein level of myocardin attenuated by knockdown of NFATc3. Concomitantly, the hypertrophic responses induced by Iso could be attenuated by knockdown of NFATc3 (Fig. 5B). Aldo-induced myocardin elevation and hypertrophic responses also could be reduced by knockdown of NFATc3 (data not shown). NFATc3 RNAi-B construct was able to reduce NFATc3 expression levels (Fig. 5C), myocardin expression levels, and cell surface areas (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that NFATc3-myocardin axis is activated in the hypertrophic pathways of Iso and Aldo.

FIGURE 5.

NFATc3 regulates myocardin expression in the hypertrophic pathway of Iso. A, knockdown of NFATc3 by RNAi-A. Cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviral NFATc3 RNAi-A or its scramble form (NFATc3-S-RNAi-A). NFATc3 protein levels were analyzed by immunoblot 48 h after infection. B, knockdown of NFATc3 attenuates hypertrophic responses induced by Iso. Cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviruses as described for A. 24 h after infection cells were exposed to 10 μm Iso. Myocardin protein levels were analyzed by immunoblot. Hypertrophy was assessed by measuring cell surface area and protein/DNA ratio 48 h after treatment. *, p < 0.05 versus Iso alone. C, knockdown of NFATc3 by RNAi-B. Cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviral NFATc3 RNAi-B or its scramble form (NFATc3-S-RNAi-B). NFATc3 protein levels were analyzed by immunoblot 48 h after infection. D, knockdown of NFATc3 attenuates hypertrophic responses induced by Iso. Cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviruses as described for C. 24 h after infection cells were exposed to 10 μm Iso. Myocardin protein levels were analyzed by immunoblot. Hypertrophy was assessed by measuring cell surface area 48 h after treatment. *, p < 0.05 versus Iso alone. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

miR-9 Can Suppress Myocardin Expression

Recently, growing evidence has shown that miRNAs are able to regulate cardiac hypertrophy. miRNAs can suppress gene expression (19, 20). Although NFATc3 can stimulate myocardin expression in the hypertrophic pathway of Iso and Aldo, can introduction of miRNAs reduce myocardin expression, thereby antagonizing cardiac hypertrophy induced by Iso and Aldo? To answer this question, we analyzed the potential miRNAs that may target myocardin using the program PicTar. miR-9 is a conserved miRNA of myocardin (Fig. 6A). We detected the expression levels of miR-9 and observed that it was down-regulated by Iso (Fig. 6B) and Aldo (Fig. 6C). Subsequently, we tested whether miR-9 is able to influence myocardin expression. The luciferase assay revealed that miR-9 could suppress the translational activity of myocardin. The administration of miR-9 antagomir but not the antagomir negative control (antagomir-NC) could block the effect of miR-9. Furthermore, the introduction of mutations in the 3′-UTR region of myocardin led to the failure of miR-9 to repress myocardin translational activity (Fig. 6D). These data suggest that the inhibitory effect of miR-9 on myocardin translation is specific. Enforced expression of miR-9 reduced the expression levels of myocardin in the cellular model (Fig. 6E). Administration of miR-9 mimic led to a decrease in myocardin levels in the animal model (Fig. 6F). Taken together, it appears that myocardin is a direct target of miR-9.

FIGURE 6.

miR-9 inhibits myocardin expression. A, the miR-9 targeting sites in myocardin 3′-UTR are evolutionarily conserved in human, rat, and mouse. B, Iso induces a reduction of miR-9 levels. Cardiomyocytes were treated with 10 μm Iso. The cells were harvested at the indicated time for the analysis of miR-9 levels. *, p < 0.05 versus control. C, Aldo induces a reduction of miR-9 levels. Cardiomyocytes were treated with 1 μm Aldo. The cells were harvested at the indicated time for the analysis of miR-9 levels. *, p < 0.05 versus control. D, miR-9 suppresses myocardin translation. HEK293 cells were transfected with the luciferase constructs of the wild type myocardin-3′-UTR (Myocardin-3′-UTR-wt) or the mutated myocardin-3′-UTR (Myocardin-3′-UTR-mut), along with the expression plasmid for miR-9, miR-9 antagomir, or the antagomir negative control (Antagomir-NC). *, p < 0.05 versus myocardin-3′-UTR-wt; #, p < 0.05 versus myocardin-3′-UTR-wt plus miR-9. E, miR-9 suppresses the expression of myocardin in the cellular model. Cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviral miR-9 or the mutated miR-9 (miR-9-mut) at the indicated moi. Myocardin expression was analyzed by immunoblot 48 h after infection. F, miR-9 suppresses the expression of myocardin in the animal model. Adult male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old) were infused with miR-9 mimic or the mimic negative control (mimic-NC) (30 mg/kg) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Myocardin expression levels were analyzed by immunoblot 3 days after infusion. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

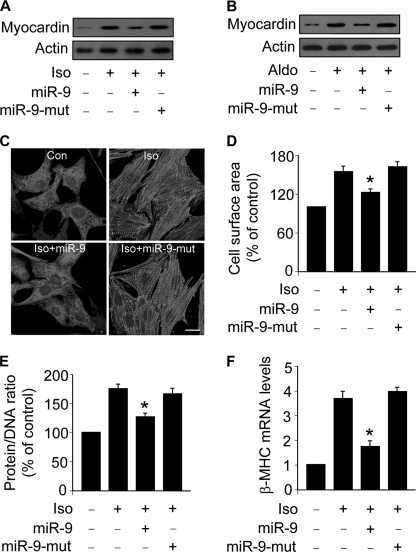

miR-9 Can Inhibit Hypertrophic Responses in the Cellular Model

To understand whether the regulation of miR-9 on myocardin expression plays a function role in hypertrophy, we tested whether miR-9 can influence hypertrophic responses upon treatment with Iso and Aldo. Enforced expression of miR-9 could reduce myocardin levels upon treatment with Iso (Fig. 7A) or Aldo (Fig. 7B). Sarcomere organization was inhibited by miR-9 (Fig. 7C). Concomitantly, miR-9 could attenuate Iso-induced increase in cell surface areas (Fig. 7D), protein/DNA ratio (Fig. 7E), and β-MHC levels (Fig. 7F). miR-9 also could reduce hypertrophic responses induced by Aldo (data not shown). These data indicate that miR-9 is able to influence hypertrophic responses.

FIGURE 7.

miR-9 inhibits hypertrophic responses in the cellular model. A, miR-9 inhibits myocardin expression in cells treated with Iso. Cardiomyocytes were infected with the adenoviral miR-9 or the mutated miR-9 (miR-9-mut) at a moi of 100. 24 h after infection, the cells were treated with 10 μm Iso. Myocardin expression was analyzed by immunoblot. B, miR-9 inhibits myocardin expression in cells treated with Aldo. Cardiomyocytes were treated as described for A, except that 1 μm Aldo was used. Myocardin expression was analyzed by immunoblot. C–F, miR-9 attenuates hypertrophic responses induced by Iso. Cardiomyocytes were treated as described for A. C, sarcomere organization. Bar, 20 μm. D, cell surface area measurement. E, protein/DNA ratio. F, β-MHC expression levels. *, p < 0.05 versus Iso alone. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

miR-9 Attenuates Cardiac Hypertrophy in the Animal Model

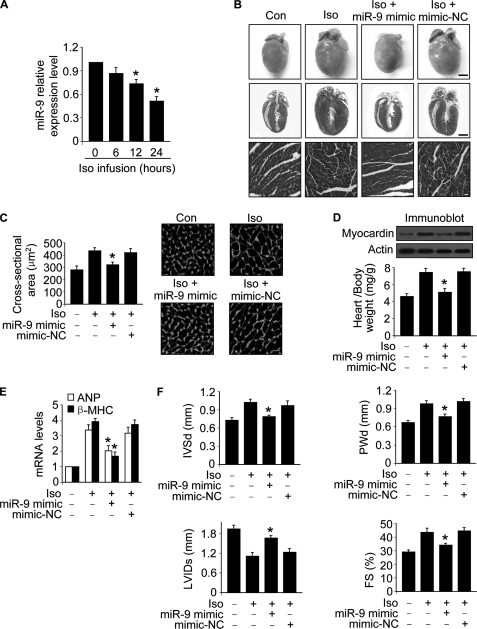

We explored the role of miR-9 in hypertrophy in animal model. The expression levels of miR-9 were down-regulated in hearts upon Iso treatment (Fig. 8A). We tested whether the supplement of miR-9 can influence the effect of Iso on cardiac hypertrophy. Administration of miR-9 mimic could inhibit Iso-induced hypertrophy revealed by hypertrophic phenotype (Fig. 8B), cross-sectional areas (Fig. 8C), heart weight/body weight ratio (Fig. 8D), and the expression levels of hypertrophic markers including atrial natriuretic peptide and β-MHC (Fig. 8E). We further tested whether miR-9 mimic can influence cardiac structure and function. Administration of miR-9 mimic could ameliorate cardiac structure and function assessed by echocardiography (Fig. 8F). These data suggest that miR-9 mimic can inhibit cardiac hypertrophy in the animal model.

FIGURE 8.

miR-9 inhibits cardiac hypertrophy in the animal model. A, Iso induces a reduction of miR-9 levels in the hearts. Adult male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old) were infused with Iso (30 mg/kg). The expression levels of miR-9 were determined with qRT-PCR. *, p < 0.05 versus control. B–E, miR-9 mimic inhibits cardiac hypertrophy. Adult male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old) were infused with Iso (30 mg/kg/day), along with miR-9 mimic or the mimic negative control (mimic-NC) (30 mg/kg) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, histological sections of hearts, gross hearts (top row; bar, 2 mm), heart sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin in the middle row (bar, 2 mm) and bottom row (bar, 20 μm). C, cross-sectional areas analyzed by staining with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin. *, p < 0.05 versus Iso alone. D, the protein levels of myocardin in the hearts (top panels) and the ratio of heart/body weight (bottom panel). *, p < 0.05 versus Iso alone. E, the expression levels of atrial natriuretic peptide and β-MHC. *, p < 0.05 versus Iso alone. F, echocardiographic assessment of cardiac dimensions and function. Echocardiography was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The mice were treated as described for B. Diastolic interventricular septal thickness (IVSd), diastolic posterior wall thickness (PWd), systolic left ventricular internal diameters (LVIDs), and fractional shortening of left ventricular diameter (FS). *, p < 0.05 versus Iso alone. The values represent means ± S.E. (n = 5–6). Con, control.

DISCUSSION

Cardiac hypertrophy is regulated by a complex molecular interaction (33–38). Our present work reveals that NFATc3 and myocardin constitute an axis that is able to mediate the hypertrophic signal of Iso and Aldo. Strikingly, miR-9 is able to target myocardin, but its expression is down-regulated by Iso and Aldo. Administration of miR-9 mimic can attenuate cardiac hypertrophy initiated by Iso or Aldo (Fig. 9). Our data provide important information for the understanding of cardiac hypertrophic machinery.

FIGURE 9.

Schematic model of cardiac hypertrophy regulated by miR-9. Iso or Aldo can induce a decrease in the levels of phosphorylated form of NFATc3 and miR-9, thereby leading to the elevation of myocardin that initiates the hypertrophic program. Administration of miR-9 mimic is able to attenuate cardiac hypertrophy.

NFATc3 subcellular distributions are controlled by its phosphorylation status. The phosphorylated NFATc3 is predominantly distributed in the cytoplasm. Calcineurin can dephosphorylate NFATc3, thereby leading to its translocation to the nucleus where it associates with GATA4 that is a zinc finger transcription factor and directly regulates cardiac hypertrophy-related genes (39). Although NFATc3 plays an important role in mediating the hypertrophic signal, few downstream targets of NFATc3 in hypertrophic cascades have been identified. Electrically stimulated pacing of cultured cardiomyocytes can serve as an experimentally convenient and physiologically relevant in vitro model of cardiac hypertrophy. Electrical pacing triggers the activation of NFATc3 that can regulate adenylosuccinate synthetase 1 gene expression (40). Our present work for the first time demonstrated that myocardin is a transcriptional target of NFATc3 and functions as a downstream mediator to convey the hypertrophic signal of NFATc3.

Myocardin is a transcriptional coactivator that is able to promote cardiac hypertrophic responses. Forced expression of myocardin in cardiomyocytes is sufficient to induce the fetal cardiac gene expression and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (18). Glycogen synthase kinase 3β is able to regulate cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (3, 41, 42). It has been reported that glycogen synthase kinase 3β can phosphorylate myocardin, thereby controlling the hypertrophic program (44). STARS (striated muscle activator of Rho signaling) is a muscle-specific actin-binding protein localized to the I band and the M line of the sarcomere, and it can activate myocardin during cardiac remodeling (45). Our recent work has shown that myocardin can be stimulated by reactive oxygen species in the hypertrophic pathway (24). The present study demonstrates that myocardin is necessary for Iso and Aldo to initiate hypertrophy. It would be interesting to find out the role of myocardin in hypertrophy induced by other stimuli.

Growing evidence has shown that miRNAs are able to regulate cardiac hypertrophy. Overexpression of the muscle specific miR-1 with a myosin heavy chain promoter in a transgenic mouse model inhibits myocyte proliferation and cardiac development (46), and the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated potassium 2 and 4 (HCN2 and HCN4) genes have been identified as its targets (47). Inhibition of another muscle-specific miRNA, miR-133, which belongs to the same transcriptional unit with miR-1 by an antagomir, causes significant cardiac hypertrophy (21). Several targets of miR-133 have been found, including HCN4 and RhoA that is a GDP-GTP exchange protein. Furthermore, Cdc42, a kinase regulating cardiac hypertrophy, and Nelf-A/WHSC2, a nuclear factor implicated in cardiogenesis, also are found to be targets of miR-133 (21, 47). Besides miR-1 and miR133, miR-208 has been characterized as an essential component regulated to cardiac hypertrophy, and thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein 1 is demonstrated to be a target of miR-208 (22). Recently, miR-21 and miR-29 have been characterized as important regulators of fibrosis. In the mice infused with miR-21 antagomir, interstitial fibrosis is inhibited because of the reduced activity of ERK-MAP kinase. miR-21 can activate the ERK-MAP kinase activity by repressing the expression of sprouty homologue 1 (48). It has been showed that miR-29 functions in fibrosis by suppressing the expression of collagen genes (49). Our present work has identified miR-9 to be an anti-hypertrophic miRNA, and it inhibits cardiac hypertrophy by targeting myocardin. Our data shed new light on the understanding of hypertrophic machinery regulated by miRNAs.

According to the functions of miRNAs, they can be classified as pro-hypertrophic and anti-hypertrophic miRNAs. To silence the endogenous miRNAs that are able to convey hypertrophic signals, the engineered oligonucleotides termed “antagomirs” that form complementary base pairs with miRNA and effectively inactivate miRNA function have been used to antagonize cardiac hypertrophy (43, 50, 51). In contrast to using antagomirs that are to target the pro-hypertrophic miRNAs, our present work has employed miR-9 mimic and found that it can attenuate cardiac hypertrophy. Thus, it appears that the mimic of a miRNA also can be used to regulate hypertrophy.

In summary, our results for the first time demonstrate that NFATc3 can regulate myocardin expression through a transcriptional manner, and such regulation contributes to causing the elevation of myocardin in hypertrophy induced by Iso and Aldo. Most importantly, miR-9 is identified to be able to suppress myocardin expression, and its mimic can attenuate cardiac hypertrophy. Our findings provide novel evidence for future studies to explore the therapeutic approaches for cardiac hypertrophy as well as heart failure by employing miRNAs.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 30730045 and 30871243 and by National Basic Research Program of China Program 973 Grant 2007CB512000.

- NFATc3

- nuclear translocation of nuclear factor of activated T cells c3

- Aldo

- aldosterone

- Iso

- isoproterenol

- β-MHC

- β-myosin heavy chain

- miRNA

- microRNA

- RNAi

- RNA interference

- β-gal

- β-galactosidase

- TRITC

- tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate

- UTR

- untranslated region

- qRT

- quantitative reverse transcription

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- MAP

- mitogen-activated protein

- moi

- multiplicity of infection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sugden P. H. (2003) Circ. Res. 93, 1179–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kass D. A., Bronzwaer J. G., Paulus W. J. (2004) Circ. Res. 94, 1533–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardt S. E., Sadoshima J. (2002) Circ. Res. 90, 1055–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang J., Shelton J. M., Richardson J. A., Kamm K. E., Stull J. T. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 19748–19756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willis M. S., Ike C., Li L., Wang D. Z., Glass D. J., Patterson C. (2007) Circ. Res. 100, 456–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vega R. B., Harrison B. C., Meadows E., Roberts C. R., Papst P. J., Olson E. N., McKinsey T. A. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 8374–8385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olson E. N., Molkentin J. D. (1999) Circ. Res. 84, 623–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molkentin J. D. (2000) Circ. Res. 87, 731–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molkentin J. D., Lu J. R., Antos C. L., Markham B., Richardson J., Robbins J., Grant S. R., Olson E. N. (1998) Cell 93, 215–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu W., Zou Y., Shiojima I., Kudoh S., Aikawa R., Hayashi D., Mizukami M., Toko H., Shibasaki F., Yazaki Y., Nagai R., Komuro I. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 15239–15245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeda Y., Yoneda T., Demura M., Usukura M., Mabuchi H. (2002) Circulation 105, 677–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim H. W., De Windt L. J., Steinberg L., Taigen T., Witt S. A., Kimball T. R., Molkentin J. D. (2000) Circulation 101, 2431–2437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill J. A., Karimi M., Kutschke W., Davisson R. L., Zimmerman K., Wang Z., Kerber R. E., Weiss R. M. (2000) Circulation 101, 2863–2869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clipstone N. A., Crabtree G. R. (1992) Nature 357, 695–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okamura H., Aramburu J., García-Rodríguez C., Viola J. P., Raghavan A., Tahiliani M., Zhang X., Qin J., Hogan P. G., Rao A. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 539–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilkins B. J., De Windt L. J., Bueno O. F., Braz J. C., Glascock B. J., Kimball T. F., Molkentin J. D. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7603–7613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkins B. J., Dai Y. S., Bueno O. F., Parsons S. A., Xu J., Plank D. M., Jones F., Kimball T. R., Molkentin J. D. (2004) Circ. Res. 94, 110–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xing W., Zhang T. C., Cao D., Wang Z., Antos C. L., Li S., Wang Y., Olson E. N., Wang D. Z. (2006) Circ. Res. 98, 1089–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sucharov C., Bristow M. R., Port J. D. (2008) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 45, 185–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valencia-Sanchez M. A., Liu J., Hannon G. J., Parker R. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 515–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carè A., Catalucci D., Felicetti F., Bonci D., Addario A., Gallo P., Bang M. L., Segnalini P., Gu Y., Dalton N. D., Elia L., Latronico M. V., Høydal M., Autore C., Russo M. A., Dorn G. W., 2nd, Ellingsen O., Ruiz-Lozano P., Peterson K. L., Croce C. M., Peschle C., Condorelli G. (2007) Nat. Med. 13, 613–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Rooij E., Sutherland L. B., Qi X., Richardson J. A., Hill J., Olson E. N. (2007) Science 316, 575–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Rooij E., Sutherland L. B., Liu N., Williams A. H., McAnally J., Gerard R. D., Richardson J. A., Olson E. N. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 18255–18260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan W. Q., Wang K., Lv D. Y., Li P. F. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29730–29739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reinhold M. I., Abe M., Kapadia R. M., Liao Z., Naski M. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 38209–38219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin Z., Murtaza I., Wang K., Jiao J., Gao J., Li P. F. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12103–12108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murtaza I., Wang H. X., Feng X., Alenina N., Bader M., Prabhakar B. S., Li P. F. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 5996–6004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y. Z., Lu D. Y., Tan W. Q., Wang J. X., Li P. F. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 564–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J. X., Li Q., Li P. F. (2009) Cancer Res. 69, 492–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen C., Ridzon D. A., Broomer A. J., Zhou Z., Lee D. H., Nguyen J. T., Barbisin M., Xu N. L., Mahuvakar V. R., Andersen M. R., Lao K. Q., Livak K. J., Guegler K. J. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, e179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang T. C., Wentzel E. A., Kent O. A., Ramachandran K., Mullendore M., Lee K. H., Feldmann G., Yamakuchi M., Ferlito M., Lowenstein C. J., Arking D. E., Beer M. A., Maitra A., Mendell J. T. (2007) Mol. Cell 26, 745–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dolber P. C., Bauman R. P., Rembert J. C., Greenfield J. C., Jr. (1994) Am. J. Physiol. 267, H1279–H1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skurk C., Izumiya Y., Maatz H., Razeghi P., Shiojima I., Sandri M., Sato K., Zeng L., Schiekofer S., Pimentel D., Lecker S., Taegtmeyer H., Goldberg A. L., Walsh K. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 20814–20823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuster G. M., Pimentel D. R., Adachi T., Ido Y., Brenner D. A., Cohen R. A., Liao R., Siwik D. A., Colucci W. S. (2005) Circulation 111, 1192–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langenickel T. H., Buttgereit J., Pagel-Langenickel I., Lindner M., Monti J., Beuerlein K., Al-Saadi N., Plehm R., Popova E., Tank J., Dietz R., Willenbrock R., Bader M. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 4735–4740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H. H., Willis M. S., Lockyer P., Miller N., McDonough H., Glass D. J., Patterson C. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 3211–3223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wollert K. C., Heineke J., Westermann J., Lüdde M., Fiedler B., Zierhut W., Laurent D., Bauer M. K., Schulze-Osthoff K., Drexler H. (2000) Circulation 101, 1172–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zou Y., Komuro I., Yamazaki T., Kudoh S., Uozumi H., Kadowaki T., Yazaki Y. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9760–9770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vega R. B., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36981–36984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xia Y., McMillin J. B., Lewis A., Moore M., Zhu W. G., Williams R. S., Kellems R. E. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 1855–1863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antos C. L., McKinsey T. A., Frey N., Kutschke W., McAnally J., Shelton J. M., Richardson J. A., Hill J. A., Olson E. N. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 907–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haq S., Choukroun G., Kang Z. B., Ranu H., Matsui T., Rosenzweig A., Molkentin J. D., Alessandrini A., Woodgett J., Hajjar R., Michael A., Force T. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 151, 117–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thum T., Catalucci D., Bauersachs J. (2008) Cardiovasc. Res. 79, 562–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Badorff C., Seeger F. H., Zeiher A. M., Dimmeler S. (2005) Circ. Res. 97, 645–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuwahara K., Teg Pipes G. C., McAnally J., Richardson J. A., Hill J. A., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1324–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao Y., Samal E., Srivastava D. (2005) Nature 436, 214–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luo X., Lin H., Pan Z., Xiao J., Zhang Y., Lu Y., Yang B., Wang Z. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20045–20052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thum T., Gross C., Fiedler J., Fischer T., Kissler S., Bussen M., Galuppo P., Just S., Rottbauer W., Frantz S., Castoldi M., Soutschek J., Koteliansky V., Rosenwald A., Basson M. A., Licht J. D., Pena J. T., Rouhanifard S. H., Muckenthaler M. U., Tuschl T., Martin G. R., Bauersachs J., Engelhardt S. (2008) Nature 456, 980–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Rooij E., Sutherland L. B., Thatcher J. E., DiMaio J. M., Naseem R. H., Marshall W. S., Hill J. A., Olson E. N. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 13027–13032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen J. F., Callis T. E., Wang D. Z. (2009) J. Cell Sci. 122, 13–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Rooij E., Marshall W. S., Olson E. N. (2008) Circ. Res. 103, 919–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]