Abstract

The specific white matter location of all the spinal pathways conveying penile input to the rostral medulla is not known. Our previous studies using rats demonstrated the loss of low but not high threshold penile inputs to medullary reticular formation (MRF) neurons after acute and chronic dorsal column (DC) lesions of the T8 spinal cord and loss of all penile inputs after lesioning the dorsal three-fifths of the cord. In the present study, select T8 lesions were made and terminal electrophysiological recordings were performed 45–60 days later in a limited portion of the nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis (Gi) and Gi pars alpha. Lesions included subtotal dorsal hemisections that spared only the lateral half of the dorsal portion of the lateral funiculus on one side, dorsal and over-dorsal hemisections, and subtotal transections that spared predominantly just the ventromedial white matter. Electrophysiological data for 448 single unit recordings obtained from 32 urethane-anaesthetized rats, when analysed in groups based upon histological lesion reconstructions, revealed (1) ascending bilateral projections in the dorsal, dorsolateral and ventrolateral white matter of the spinal cord conveying information from the male external genitalia to MRF, and (2) ascending bilateral projections in the ventrolateral white matter conveying information from the pelvic visceral organs (bladder, descending colon, urethra) to MRF. Multiple spinal pathways from the penis to the MRF may correspond to different functions, including those processing affective/pleasure/motivational, nociception, and mating-specific (such as for erection and ejaculation) inputs.

Introduction

In the United State alone, an estimated 1,275,000 people are living with paralysis from spinal cord injury (SCI) (Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation, 2009; http://www.christopherreeve.org). The cost in emotional stress and well-being to the individual and family is understandably demanding. SCI results in a number of disabling sequelae, including impairments of locomotor, sensory and autonomic functions. Deficits in ejaculation, micturition and defecation are among the most devastating outcomes of SCI. Sexual, bladder and bowel dysfunction consistently rank among the top disorders affecting quality of life after SCI (Anderson, 2004; Ditunno et al. 2008), yet compared to the voluminous literature on the neural pathways involved in the sensation and motor control of the limbs, there have been relatively few studies on the male urogenital organs. This may partly be due to the complexity of the neural pathways involved in urogenital functions.

In 95% of SCI individuals with lesions cranial to T10, ejaculation is severely impaired or impossible despite the intact spinal reflex arc, suggesting the ejaculatory reflex circuitry is dependent on supraspinal facilitation or disinhibition (Ver Voort, 1987; Sachs & Bitran, 1990; Seftel et al. 1991). Most of these individuals demonstrate reflexogenic erections of varying degrees in response to very slight mechanical stimulation of the penis (Sarkarati et al. 1987; Ver Voort, 1987), although the erections are not easily sustained (Bodner et al. 1987) and have been proposed to be a result of altered penile sensitivity (Goldstein, 1988). Many SCI males who do not respond to normal tactile stimulation of the penis may ejaculate to very intense vibratory stimulation of the ventral penile midline (Sonksen & Ohl, 2002), suggesting that massive recruitment of all low and high threshold penile mechano-receptive afferent neurons can provide enough input to the spinal ejaculatory circuit. In addition to erectile dysfunction and ejaculatory failure, abnormal sperm motility and viability as early as 2 weeks post-SCI contribute to neurogenic reproductive dysfunction post-SCI (Patki et al. 2008).

Many persons with SCI also develop detrusor-urethral sphincter dyssynergia, which results from inappropriate contraction or failure of relaxation of the external urethral sphincter coincident with detrusor muscle contraction (Yalla et al. 1977; Rudy et al. 1988; Gerridzen et al. 1992; de Groat et al. 1997). Conscious control of defecation is also lost, leaving only the ability to defecate reflexively by anorectal stimulation (MacDonagh et al. 1992). These individuals suffer from chronic constipation and fecal incontinence (Glick et al. 1984; Longo et al. 1989; MacDonagh et al. 1992). Both urinary bladder dysfunction and severe constipation are causes of significant morbidity and mortality in this population (Glick et al. 1984), although renal failure is the most common (Hackler, 1977).

The lumbosacral segments (L5–S1 in the rat) contain a centre for erection and the propulsive part of ejaculation mediated by preganglionic parasympathetic motor axons in the pelvic nerve and somatic motor axons in the pudendal nerve supplying the striated perineal muscles of the pelvic floor (Coolen et al. 2004; Giuliano & Rampin, 2004; Pastelin et al. 2008). The peripheral sensory limb of the segmental reflexes for erection and ejaculation is carried primarily by afferents in the dorsal nerve of the penis (DNP) (Nunez et al. 1986). Experiments by Johnson and co-workers have characterized the primary afferent population in the DNP (Kitchell et al. 1982; Johnson, 1988; Johnson & Halata, 1991; Johnson & Murray, 1992). Desensitization of the penis, produced by local anaesthesia or dorsal nerve section, causes an impairment of reflexogenic erection, intromission and ejaculation (Hart & Leedy, 1985). The neural pathways from the gastrointestinal and lower urinary tracts have also been the subject of intense research (see review by Sengupta & Gebhart, 1995). Briefly, afferents innervating these organs (including the bladder, descending colon and rectum) travel to the spinal cord via the pelvic (otherwise primarily parasympathetic) and hypogastric and lumbar colonic (otherwise primarily sympathetic) nerves. Rectal pain in humans, for example, is believed to be the result of noxious information conveyed centrally to the thoracolumbar cord, whereas conscious perception of normal rectal sensations (fullness, urgency) is thought to be mediated by sacral (i.e. pelvic) afferents (see Bernstein et al. 1996 for review).

We have, in recent years, developed and characterized an in vivo brainstem–spinal cord electrophysiological animal model to study the neurological causes of sexual dysfunction following severe mid-thoracic SCI (Hubscher & Johnson, 1996; Johnson & Hubscher, 1998; Hubscher & Johnson, 1999b, 2000; Johnson & Hubscher, 2000). Our previous studies with this model have shown that chronic bilateral lesions of the dorsal three-fifths of T8 spinal cord is correlated with (i) impaired bladder and/or sexual reflexes, (ii) changes in lumbosacral neural circuits mediating perineal muscle function and (iii) loss of ascending and descending connections between the distal urogenital tract and the medullary reticular formation (MRF). The specific white matter location of all the spinal pathways conveying penile input to the rostral medulla is not known. Many individual MRF neurons in the rat respond to bilateral electrical stimulation of the DNP and pelvic nerve (PN). These neurons also receive convergent inputs from multiple somatic and pelvic/visceral territories, including the distal colon, urinary bladder and urethra (Kaddumi & Hubscher, 2006). While most responses result from noxious stimulation levels, 32% of DNP/PN-responsive MRF neurons respond to stroking as well as pinching of the penis. MRF neuronal responses to stroking of the penis are lost following either an acute or a chronic dorsal column (DC) lesion at the T8 spinal level (Hubscher & Johnson, 1999b, 2004). MRF responses, however, still remain for bilateral DNP stimulation post-DC lesions as both Aβ and Aδ DNP afferents are activated by the electrical search stimulus. In addition, responses remain not only for pinching the penis but for distension of the urinary bladder and descending colon as well. The low threshold penile input to MRF that is lost is likely to be conveyed, either directly or indirectly, via the nucleus gracilis in the caudal medulla, which receives primary afferent inputs from the DNP (Cothron et al. 2008).

In the present study, select chronic lesions were made in order to allow us to determine the white matter location of other neural pathways conveying ascending urogenital inputs, via the lumbosacral spinal cord, to the MRF in the rostral medulla. Knowledge of the location of all the circuitries that are able to convey information supraspinally after a chronic SCI will provide therapeutic targets to improve the control and coordination of sexual, bladder and bowel functions following chronic SCI.

Methods

Thirty-two male Wistar rats (Harlan Laboratories, Inc., Indianapolis, IN, USA) approximately 60–70 days old weighing 220–250 g were individually housed in an animal room with a 12 h light and dark cycle. All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee at the University of Louisville, School of Medicine and comply with the policies and regulations for reporting ethical matters in The Journal of Physiology (Drummond, 2009). Select lesions at the T8 spinal level were performed under aseptic conditions. All rats were anaesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (80 mg kg−1 of body weight) and xylazine (10 mg kg−1 of body weight) injected intraperitoneally (Hubscher & Johnson, 1999b). Additional 0.2 ml doses of the mixture (0.12 ml of 100 mg ml−1 ketamine and 0.08 ml of 20 mg ml−1 xylazine) were given as needed. After induction of anaesthesia, animals were given 0.5 ml subcutaneous injection of Ambi-Pen (penicillin G and penicillin G procrain, Butler).

The spinal cord was exposed by laminectomy of the T7 vertebra, which overlies the T8 portion of the spinal cord (Hubscher & Johnson, 1999a). In order to make a select lesion, a custom-made 0.12 mm thick and 1.6 mm wide blade attached to the Vibraknife of a modified Vibratome series 1000 (Zhang et al. 2004) was used, a device which was made at the University of Louisville. The target vertebra of the rat was stabilized on a platform and this platform was elevated until the oscillating blade contacted the dorsal surface of the spinal cord. The spinal cord was cut by gradually elevating the platform. The spinal cord and the Vibraknife blade were immersed in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and dorsal to ventral transverse lesions of varying depths and medial–lateral placements were made (Zhang et al. 2004). Some treatment groups received either partial or complete dorsal hemisection lesions, all of which included the DCs, while other groups had lesions that included portions of the ventrolateral funiculus (VLF). The two separated pieces of spinal cord that had been created by the laceration were placed against each other as if no laceration had been made, and the area was covered between the dura/arachnoid mater and the dorsal surface of the spinal cord 2 mm caudal and 2 mm rostral to the laceration with a thin coat of Fibrin adhesive sealant (Tisseel; Baster Healthcare Corp., Glendale, CA, USA) (Zhang et al. 2004). After the Tisseel placement, the dura was closed using two No. 10-0 sutures (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA) (Zhang et al. 2004). All musculature and subcutaneous tissue was sutured closed (Ethicon 4-0 non-absorbent surgical suture) and Michel clips were used to close the skin (Hubscher & Johnson, 2002).

In the days following surgery, all rats were monitored 3 times per day to express bladders, monitor wounds, note changes in the animals’ general condition, and clean the animals, if necessary. During the two days immediately following surgery, animals were given subcutaneous injections of an analgesic, ketoprofen (2.5 mg (kg body weight)−1), twice daily. In addition, animals were given gentamicin (5 mg (kg body weight)−1) for 4 days following surgery for prevention of possible bladder infections. Approximately 7 days after surgery, Michel clips were removed from the skin.

MRF recordings

At 45–60 days post-lesion, each animal was anaesthetized with 50% urethane (1.2 g kg−1) and the jugular vein, carotid artery and trachea were exposed and intubated for anaesthetic supplement (5% urethane: 0.1 ml of 0.05 g ml−1 urethane, as needed), blood pressure monitoring, and respiratory rate/end expired  level monitoring, respectively. Body temperature was monitored throughout the experiment by an esophageal probe connected to a thermometer and maintained at around 37°C using a circulating water-heating pad. After mounting the animal onto a stereotaxic device, a dorsal incision was made to gain access to the brainstem. The dorsal surface of rostral medulla was exposed by removing part of the occipital bone and suctioning the caudal midline portion of the overlying cerebellum (Hubscher & Johnson, 1996, 1999a).

level monitoring, respectively. Body temperature was monitored throughout the experiment by an esophageal probe connected to a thermometer and maintained at around 37°C using a circulating water-heating pad. After mounting the animal onto a stereotaxic device, a dorsal incision was made to gain access to the brainstem. The dorsal surface of rostral medulla was exposed by removing part of the occipital bone and suctioning the caudal midline portion of the overlying cerebellum (Hubscher & Johnson, 1996, 1999a).

A tungsten microelectrode with ∼7 ± 1 MΩ impedance (FHC Inc., Bowdoinham, ME, USA) was lowered from the dorsal surface of the brainstem with a motorized drive (FHC Inc.) into the MRF. Stereotaxic coordinates were 3400 μm rostral to obex and 400 μm and 800 μm lateral to midline on both sides of the brainstem (4 tracks per animal collectively). The search area for each dorso-ventral track was 2800–3000 μm in length, which covered the rostral part of the nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis (Gi), Gi pars alpha (GiA), and the medial part of the lateral paragigantocellular nucleus (LPGi) (Hubscher & Johnson, 1999a).

To insure, as in our previous studies, that the same populations of somatovisceral convergent neurons were being sampled in our current experiments, pinching the ear was used as our search stimulus in addition to bilateral PN (bPN) stimulation (30–50 μA, 0.1 ms duration, with trains of 14 pulses at 70 pulses s−1, 100 ms train duration, 1 train s−1; Hubscher & Johnson, 1996). Note that many of the somatovisceral convergent neurons respond to stimulation of the entire body surface and 100% respond to ear pinch, as previously described (Hubscher & Johnson, 1999a, 2006). Recording of a single neuron was established by monitoring the action potential on an oscilloscope with a spike-triggered analog delay module for discrimination of somato-dendritic neuron profiles from nerve fibre spikes as described previously (Hubscher & Johnson, 1996, 1999a, 2006). Once a single neuron responsive to ear pinching and/or bPN was found, responses to mechanical (stroke and pinch) stimuli of the dorsal trunk and to other above level somatic areas (eyelids and face) were tested. In addition, as in our previous studies, we tested multiple somatic and visceral territories below level, including bilateral DNP (bDNP)/penis, descending colon and bladder distension (MRF responses in noxious range based upon previous studies, e.g. Kaddumi & Hubscher, 2006), urethral stimulation, and stroke/pinch of the hind limbs (Hubscher et al. 2004; Kaddumi & Hubscher, 2006, 2007). Urinary bladder and urethral catheters, comprising PE 60 tubing attached to a syringe, were implanted through the proximal urethra with one catheter directed toward the bladder for distension and other directed toward the distal urethra (see Fig. 1 in Kaddumi & Hubscher, 2006). Bladder and colon (10 mm balloon inserted intra-anally for distension –Kaddumi & Hubscher, 2006) catheters were connected to a pressure monitor (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA). MRF neuronal responses and bladder/colon pressures were recorded to videotape and analysed offline using Data Wave software (SciWorks, Winston Salem, CO, USA; http://www.dwavetech.com). Onset and offset of the mechanical stimuli were recorded to tape on a second channel with an external manual trigger device which generated an electrical timing pulse.

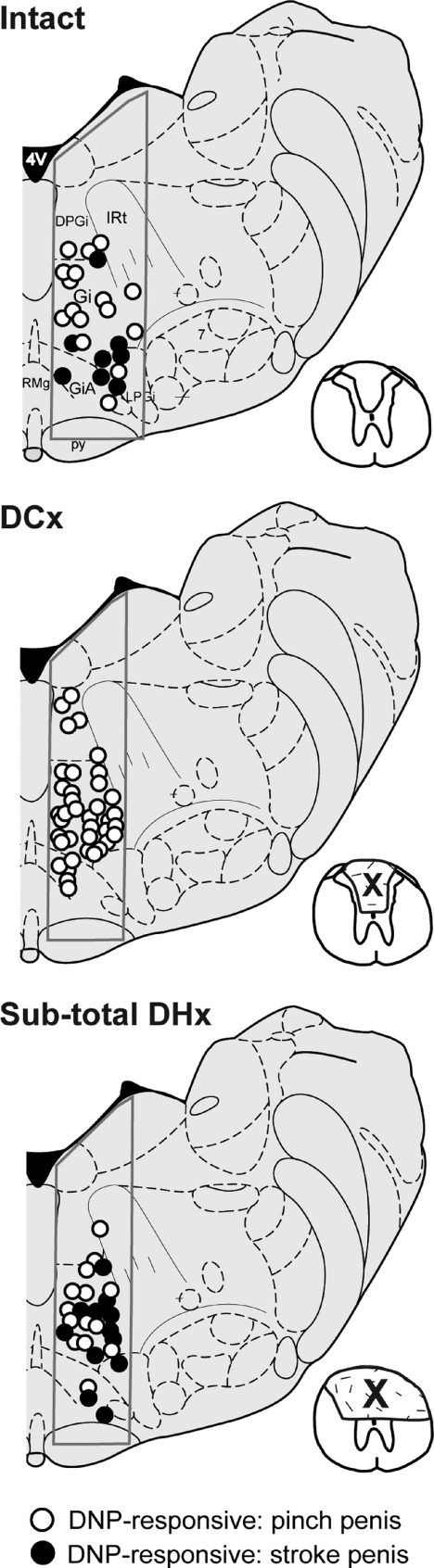

Figure 1. Effect of sub-total dorsal hemisection (DHx).

Example showing the location of pelvic nerve (PN)-responsive MRF neurons in 3 rats with a chronic sub-total dorsal hemisection lesion (DHx) at T8 (bottom panel) compared to the location of neurons described in Hubscher & Johnson (2004) for spinally intact animals (top panel, n= 3) and animals with a bilateral dorsal column lesion (DCx) at T8 (middle panel, n= 3). All of these neurons also responded to bilateral electrical stimulation of the dorsal nerve of the penis (DNP). Responses to low (stroke) and high (pinch) threshold levels of mechanical stimulation of the penis are listed for each group. Note a lack of responses to stroke following DCx but a re-emergence following extension of the lesion to the medial portions of the DLF bilaterally and sparing the lateral DLF on one side. Inserts illustrate the extent of the lesion (X). Cross section is adapted from Fig. 65 of Paxinos & Watson (1998).

Histology

Tissue processing

After completion of the terminal electrophysiology experiment, each animal was killed with an anaesthetic overdose of urethane. Perfusions were performed transcardially with 0.9% saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The animal's spinal cord was removed and placed in a 30% sucrose–phosphate buffer solution with 1% sodium azide for at least 24 h and until the tissue was cut on the cryostat (Leica CM1850). A small piece of spinal cord tissue, which contained the lesion site, was mounted onto a metal chuck and frozen using Tris-buffered saline (TBS) tissue freezing medium (Triangle Biomedical Sciences, Durham, NC, USA). The tissue was cut into 18 μm thick dorsal to ventral transverse sections and mounted onto charged glass microscope slides (Fisher Scientific premium frosted microscope slides). Following the cutting and mounting of tissue, the slides were placed onto a slide warmer to dry.

The Klüver–Barrera method (as adapted from the protocol presented by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology) was used to stain the tissue (Luna, 1968). This protocol combines the luxol fast blue stain, which is used to indicate the presence of myelin, with the cresyl echt violet stain, which is used to stain Nissl substance in nervous tissue (Carson, 1990).

Slide staining

In order to dissolve freezing medium and hydrate the tissue, slides were briefly rinsed with distilled water. Slides were placed in a Coplin jar with luxol fast blue and left in the oven overnight at a temperature of 55°C. The following day, luxol fast blue stain was drained and slides were rinsed briefly with 95% ethanol. Next, slides were rinsed again with distilled water and placed in a 0.05% lithium carbonate solution for 10 min. Then, slides were rinsed with 70% ethanol for 2 min and afterward rinsed briefly with distilled water. Slides were again immersed in lithium carbonate for 10 min followed by a 2 min 70% ethanol rinse. After rinsing with distilled water, slides were placed into a cresyl violet solution for 2 min 15 s. The cresyl violet stain was drained, and slides were rinsed again with distilled water before being placed in two rinses of 95% ethanol for 2 min followed by two rinses of 100% ethanol for 1 min. To finalize the procedure, slides were soaked in xylene and coverslipped with a 50:50 Gurr mounting adhesive–xylene mixture.

After drying, the slides were viewed under a light microscope at 40× magnification to locate the epicenter of the lesion. Using a Spot Insight colour camera mounted on a Nikon E400 microscope, pictures were taken of a section from a more intact portion of spinal cord (located 1–1.5 mm away from the epicenter) and the epicenter at 40× magnification. A comparison was then done between the intact spinal cord pictures and their respective epicenters for each animal to assess degree of damage. Landmarks used for the regional divisions of the transverse cord sections were the central canal, the medial edges of the dorsal horn, and the tips of the ventral horn.

Results

Prior to the analysis of the electrophysiological data, histological reconstruction of the lesion epicenters was done to confirm the accuracy of the four different lesion types that were attempted. Based upon the extent of damage/sparing at the lesion epicenter, the assigned group was changed for three animals (one extended more lateral than intended and two did not reach the targeted depth). Specifically, instead of four lesion groups with eight rats per group, the four groups with lesions in common have n values of 7, 9, 10 and 6. In the present study, 448 neurons responded to pinching the ear and 269 of those responded to both of the search stimuli (pinching of the ear and bPN stimulation), the difference being the loss of PN inputs in the rats where the lesions were much larger (see below). A summary of the MRF electrophysiological recording data for the four groups of rats is presented in Table 1 which includes data from Hubscher & Johnson (2004) for comparison.

Table 1.

Select chronic lesion effects on urogenital and colon inputs to MRF

| Dorsal cord lesions |

+ Ventral cord lesions |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter* (search criteria – responds to bPN and/or ear pinch) | Intact (n= 14) | bDC (n= 7) | bDC + uni-DLF (n= 7) | 3/4 DHx (n= 9) | DHx/over DHx (n= 10) | DHx + most of VLF (n= 6) |

| No. bPN | 150 | 80 | 65 | 106 | 96 | 2 |

| (no. bPN+ear) | (166) | (86) | (89) | (127) | (144) | (88) |

| % DNP/penis | 100% | 100% | 94.6 ± 3.7% | 100% | 78.3 ± 8.7% | 2.9% |

| Touch only (penis) | 32% | 0% | 1.8 ± 1.8% | 38.1 ± 3.9% | 3.0 ± 2.1% | 0% |

| % colon distension | 26% | 30% | 44.6 ± 8.4% | 49.4 ± 10% | 47.7 ± 10% | 0% |

| % bladder distension | NA | NA | 80.6 ± 8.6% | 86.6 ± 3.6% | 61.9 ± 13% | 0% |

| % urethral stimulation | NA | NA | 80.6 ± 8.6% | 84.0 ± 2.2% | 63.8 ± 3.8% | 0% |

| % hind paw pinch | 99% | 99% | 92.6 ± 5.4% | 90.3 ± 5.8% | 94.6 ± 2.8% | 40.3%± 11% |

Intact and bDC – from Hubscher & Johnson, 2004; Hubscher et al. 2004. *Percentage values in table based on total no. of neurons responding just to bPN stimulation, except for the DHx + most of VLF group (since all but 2 bPN responses were lost). bDC, bilateral dorsal column; DHx, dorsal hemisection; DLF, dorsolateral funiculus; DNP, dorsal nerve of the penis; bPN, bilateral pelvic nerve; NA, not applicable. Data are standard error of the mean.

For 106 single neurons obtained from nine urethane-anaesthetized rats with sub-total dorsal hemisections that spared only the lateral half of the dorsal portion of the lateral funiculus (DLF) on one side (3/4 DHx group), MRF responses to stroking/gentle pressure of the penis (38.1%) were found. The MRF location of these PN-responsive neurons relative to those we described previously (Hubscher & Johnson, 2004) for intact control rats and those with DC-only lesions is provided in Fig. 1 (adapted from Paxinos & Watson, 1998). Responses to stimulation of other somatovisceral territories, however, remained unchanged (see Table 1). An example of the responses for a typical single MRF neuron from a rat with a sub-total dorsal hemisection that spared only the lateral half of the DLF on one side is provided in Fig. 2. Thus, the present finding contrasts with our previous study (Hubscher & Johnson, 2004) in which no responses to stroking/gentle pressure of the penis were found with a lesion restricted to DCs (see bDC column of data in Table 1). In the present study, data from seven rats with slightly smaller lesions, sub-total dorsal hemisections that spared the entire DLF on one side, were consistent with our previously reported DC-only lesion data (Table 1). Thus, there is a re-emergence of low threshold penile responses following an asymmetric chronic lesion that includes the dorsal columns and the medial portion of the DLF bilaterally, but spares the lateral portion on one DLF.

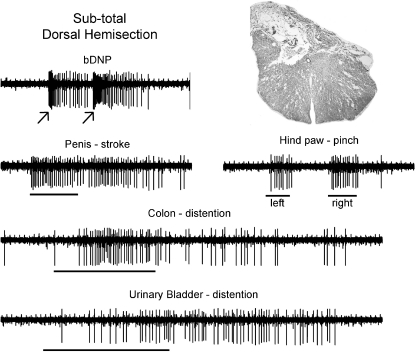

Figure 2. MRF single unit recording.

Example of convergent inputs to a PN-responsive single neuron located in left nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis at 60 days post-injury. Epochs are 6 and 12 s. An image taken from the chronic lesion epicentre for this rat is provided. The central canal, which can be seen in the middle of the section, orients both the dorsal/ventral and medial/lateral extents of the lesion. Note the presence of the responses to stroking the penis. The horizontal bar symbols on the raw records indicate the onset and duration of the hand-held stimulus application. The arrows (and the stimulus artifacts) indicate the onset of an electrical stimulus train to the respective nerve (stimulus train duration 100 ms, 70 pulses at 0.2 ms pulse duration).

In 10 rats with complete dorsal or over-dorsal hemisection, PN-responsive neurons in the MRF remain responsive to pinching the penis but the responses to stroking/gentle pressure are lost, indicating that all pathways conveying touch/pressure information from the penis to MRF are located in the dorsal half of the spinal cord. In addition, MRF neuronal responses remain for descending colon and bladder distension, as well as stimulation of the urethra (Table 1), suggesting that the pathways receiving input from these pelvic viscera also include the ventral white matter of the cord. An example illustrating a typical lesion epicenter from one of the rats in this group of 10 is shown on the far left side of Fig. 3. In one of the 10 rats with an equivalent proportion of PN-responsive MRF neurons (epicenter is the middle section in Fig. 3), fewer responses were found for pinching the penis. The lesion for this one rat was slightly deeper bilaterally, indicating a possible separation in the location of ascending projections that originate from pelvic and pudendal (contains DNP –‘sensory branch’) territories (see hatch marks in Fig. 3).

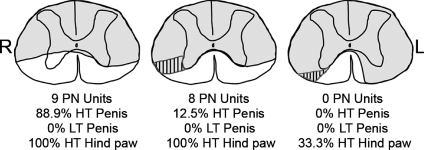

Figure 3. VLF lesion effects.

Examples of lesion epicenter reconstructions from three male rats illustrating the location of ascending pathways in the ventral half of the spinal cord to MRF from the glans penis, pelvic nerve (PN) and other input territories (bladder, urethra, descending colon). The presence of a few responses to penile stimulation in the rat whose lesion is shown in the centre panel is likely to be due to some lateral sparing on the left side of the spinal cord. Likewise, the presence of some responses to pinching the hind paw (left foot only) in the rat whose lesion is shown in the right panel is likely to be due to some medial ventrolateral funiculus sparing on the right side of the spinal cord. Hatch marks indicate overlap of white matter areas (illustrated on just one side) whose damage results in the loss of penile (middle panel) and pelvic nerve (right panel) ascending projections. Note that to completely eliminate all responses to these somatovisceral convergent neurons in the MRF, the lesion must be bilateral. HT – high threshold, L – left, LT – low threshold, R – right.

To address the location of the ascending circuitries to MRF for those territories that still respond to stimulation, chronic dorsal hemisection lesions were extended to include select portions of the ventral half of the spinal cord. Upon comparing lesion extent and electrophysiological data of somatovisceral convergent neurons in the MRF across individual rats, a relationship was evident between lesion depth in the ventrolateral funiculus (VLF) and the presence/absence of responses to stimulation of specific regions of the body. In the group of six rats in which only the ventromedial funiculus was spared bilaterally at the T8 spinal level, all responses to stimulation of the penis and pelvic visceral territories were lost. There were some responses remaining for pinching the hind paw, but in those animals there was at least some sparing of the most ventromedial portions of the VLF and the laterality matched the loss of only the responses to stimulation of the contralateral hind paw. An example from one rat is illustrated in Fig. 3 (far right lesion epicenter).

Thus, with increasing depth of lesion within the VLF, penile responses (pudendal n.) were lost first, followed by bladder/urethra/colon (pelvic n.) followed by hind paw (sciatic n.). It should be noted that the loss of responses was not all or none. In some cases, the percentage of MRF neurons responding was significantly decreased (χ2, P < 0.05) for more than one territory at a time relative to intact controls (such as for both pinching the penis as well as distension of the descending colon relative to the hind paw), indicating the likelihood of some degree of overlap between the mid-thoracic location of ascending projection pathways.

Discussion

Deficits in ejaculation, micturition and defecation are among the most devastating outcomes of SCI, severely affecting quality of life (Anderson, 2004; Anderson et al. 2007). Normal ejaculation, micturition and defecation require sequential contraction of perineal muscles that depend upon an intact segmental reflex arc and brainstem integration (Holmes & Sachs, 1991; Johnson 2006). The present study examined mid-thoracic spinal cord injury-induced changes to the urogenital ascending projection pathways to the medullary reticular formation (MRF) in order to allow us to more specifically ascertain the spinal cord regions and the specific neural circuitry which should be targeted for therapeutic interventions designed to improve the control and coordination of sexual, bladder and bowel functions following chronic SCI. The results indicate that the gigantocellular region of the MRF receives ascending spinal input at the level of T8 from the male genitalia via multiple pathways and from the pelvic viscera via projection pathways that include the VLF. In addition, the results suggest that an asymmetrical chronic lesion of the dorsal white matter leads to injury-induced changes in the responsiveness of MRF neurons receiving penile input via the spared spinal pathways.

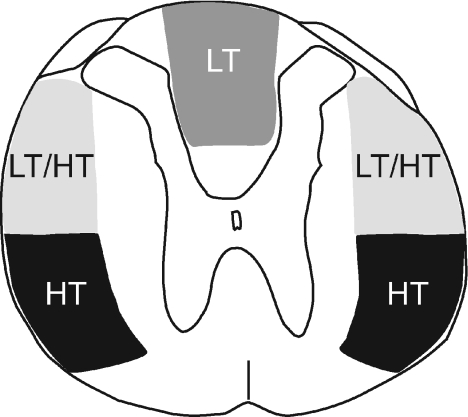

A summary illustrating the locations of the various ascending pathways conveying penile sensory information to the MRF is presented in Fig. 4. Previously, we have shown the loss of MRF responses to penile low threshold (tactile) stimuli following acute and chronic DC lesions (Hubscher & Johnson, 2004). In addition, we have shown that bilateral MRF neuronal responses remain for low threshold tactile stimulation of the penis following lateral hemisection lesions at T8 which spare a portion of the dorsal columns (Hubscher & Johnson, 1999b). The present results, however, indicate that MRF neurons respond to penile tactile stimuli after extending the chronic lesion beyond the DC to include the central portion of the lateral funiculus bilaterally and sparing the lateral portion of the DLF on one side. A possible explanation for the re-emergence of MRF responses to penile tactile stimuli following asymmetrical T8 lesions is that the bilateral partial loss of a previously identified bilateral descending modulatory pathway results in the sensitization or lowered threshold of lumbosacral projection neurons that ascend within the DLF. Bilateral electrical microstimulation of a discrete subregion of the MRF of male rats, the lateral paragigantocellularis nucleus (LPGi), produces a short-latency depression of the DNP-elicited reflex discharge of pudendal motoneurons innervating the perineal striated muscles involved in male sexual function (Johnson & Hubscher, 1998) and probably involves the presynaptic inhibition of DNP afferent terminals or inhibition of lumbosacral interneurons but not inhibition of pudendal motoneurons. This bilateral bulbospinal inhibitory pathway, in the central portion of the lateral funiculus (Hubscher & Johnson, 2000), has been implicated in the coordination of segmentally organized ejaculatory bursts of the bulbospongiosus muscle (Johnson, 2006; Coolen et al. 2004; Allard et al. 2005) as well as the regulation of intromissive-related stimuli associated with copulation, including mount frequency, intromission frequency and ejaculation latency (Yells et al. 1992). Thus, a hypothesis that increased responsiveness of MRF neurons to penile tactile stimulation after combined removal of the dorsal columns and asymmetrical removal of the DLF is produced by the disinhibition of lumbosacral neurons that ascend in the DLF is consistent with the idea proposed in mating behaviour studies that rats having bilateral lesions of the LPGi require less stimulation (intromissions) to achieve ejaculation (Yells et al. 1992). Note that in a study on the pudendal nerve evoked activity in lumbar axial muscle nerves of female rats (muscles implicated in the lordosis mating behaviour) (Cohen et al. 1987), bilateral symmetrical lesions of the lateral funiculi (including the ventrolateral columns) were necessary to eliminate supraspinal influences on the pudendal nerve evoked responses.

Figure 4. Ascending penile projections to MRF.

A summary diagram illustrating the approximate locations of multiple bilateral ascending pathways at the mid-thoracic spinal level conveying sensory information from the glans penis to the medullary reticular formation (MRF). The different stimulus thresholds to trigger a neuronal response in MRF are indicated. HT – high threshold; LT – low threshold.

The loss of responses to urogenital and descending colon stimulation with deeper ventrolateral lesions up to but not including the ventromedial spinal cord white matter at T8 implicates this area as a region conveying ascending pelvic visceral inputs to the brainstem. This finding is consistent with our previous study (Hubscher & Johnson, 2004) where the percentage of MRF neurons responding to distension of the descending colon did not change following a chronic DC lesion. These results in the MRF do contrast with those of Al-Chaer et al. (1996) who have found a significant decrease in the number of thalamic ventroposterolateral nuclear responses to colorectal distension following an acute lesion of DC but not following an acute VLF lesion. Differences with our findings could relate to the effects of acute versus chronic lesions, the stimulus used (ours did not distend the rectum), and/or the different subset of neurons studied.

As the lesion extends ventrally, the loss of penile then pelvic-visceral inputs as well as the complete loss of both of these regions prior to the hind paw (see hatch marks in Fig. 3) suggests that ascending information in the mid-thoracic VLF that includes input from both somatic and pelvic-visceral territories to MRF may be topographically organized. The solitary nucleus in the caudal medulla is known to receive widespread pelvic and visceral organ inputs (Norgren, 1978; Novin et al. 1981; Cechetto, 1987; Jean, 1991; Hubscher & Berkley, 1994) that are organized along the rostrocaudal and mediolateral axis (Altschuler et al. 1989; Altschuler et al. 1991). The somatotopic organization of the dorsal column nuclei, also in the caudal medulla, is also well established (Maslany et al. 1991). The general organization scheme suggested by our electrophysiological data is consistent with neuroanatomical tracing demonstrating the distribution of axons in the VLF projecting to lateral thalamus (Giesler et al. 1981). Note that although the spinal projections may ascend in an organized way, this organization is not maintained for the inputs to MRF neurons of the rostral medulla, which receives a high degree of somato-visceral and viscero-visceral convergent input (Kaddumi & Hubscher, 2006).

The presence of multiple pathways from the male genitalia ascending bilaterally to the MRF could provide redundancy to safeguard reproductive function. For example, in rats with complete chronic lateral hemisections, bladder and sexual reflex measures were near normal (Hubscher & Johnson, 2000) and the penile responsiveness of MRF neurons was not different from uninjured controls (Hubscher & Johnson, 1999b, 2002). It is more likely, however, that each of the pathways serves a different functional role. For example, tactile information from the penis ascending in the DCs to MRF (either directly or indirectly) may be part of the rostral transmission of information for the sexual arousal response to genital stimulation, which can lead to ejaculation. Projection neurons from the lumbosacral cord to MRF that ascend in the dorsolateral quadrant but are under descending inhibitory control with the capacity to respond to low and high threshold levels of stimulation (wide dynamic type neurons) may be part of a spino-bulbo-spinal control mechanism for ejaculation, as discussed above. Many MRF neurons (Hubscher & Johnson, 1996) require wind-up (repetitive stimulation of the DNP/penis) to respond, which could be the trigger for the disinhibition of the lumbosacral projection neurons in the intact spinal cord. Thus, the MRF neurons may under normal conditions be firing at the ejaculatory threshold, dependent on a gradual build-up of activity by multiple intromissions (Sachs & Meisel, 1988), or stimulation as in the present study.

The pathway in the VLF conveying more high threshold levels of stimuli from the penis to MRF may contribute to the ejaculatory reflex circuitry as well. Inhibition of ejaculation in humans is produced by squeezing the glans penis (Semens, 1956) and neurons in LPGi have been shown to inhibit ejaculatory reflexes (Marson & McKenna, 1990). The MRF is also involved in nociceptive processing (Satoh et al. 1979; Azami et al. 1981; Peschanski & Besson, 1984; Zhuo & Gebhart, 1990), so a projection in the VLF may be part of the circuitry associated with antinociception (Villanueva & Le Bars, 1995) that has been shown in female rats to occur in response to stimuli that occur during sexual behaviour (Watkins et al. 1984). In female rats, lesions of the dorsolateral funiculus reduce vaginal stimulation-produced analgesia, findings consistent with the locations of ascending/descending circuitries mediating ejaculatory reflexes in males.

Following spinal cord injury, the loss of multiple ascending and descending spinal pathways is likely to contribute to sexual dysfunction. The consequences of this loss include diminished genital sensation, loss of voluntary control, and the loss of the spino-bulbo-spinal control of lumbosacral reflex circuitries mediating ejaculation. Although the anatomy of the ascending sensory tract(s) from the penis in humans, as distinct from rats, is not known, the presence of multiple spinal projections mediating sexual function in our animal model provides multiple targets for future experiments that will be geared toward developing therapeutic interventions to promote improvements in sexual function following spinal cord injury.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jason Fell and Victoria Dugan for excellent technical assistance and Yi Ping Zhang and Dr Christopher Shields for use of and assistance with their customized Vibraknife device.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- b

bilateral

- DC

dorsal column

- DHx

dorsal hemisection

- DLF

dorsolateral funiculus

- DNP

dorsal nerve of the penis

- Gi

nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis

- HT

high threshold

- LPGi

lateral paragigantocellular nucleus

- LT

low threshold

- MRF

medullary reticular formation

- PN

pelvic nerve

- SCI

spinal cord injury

- VLF

ventrolateral funiculus

Author contributions

Conception and design of the experiments: C.H.H., R.D.J.; collection, analysis and interpretation of data: C.H.H., W.R.R., E.G.K., J.E.A., R.D.J.; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: C.H.H., W.R.R., E.G.K., R.D.J. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. This study was carried out at the University of Louisville.

References

- Al-Chaer ED, Lawand NB, Westlund KN, Willis WD. Visceral nociceptive input into the ventral posterolateral nucleus of the thalamus: a new function for the dorsal column pathway. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:2661–2674. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.4.2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard J, Truitt WA, McKenna KE, Coolen LM. Spinal cord control of ejaculation. World J Urol. 2005;23:119–126. doi: 10.1007/s00345-004-0494-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschuler SM, Bao XM, Bieger D, Hopkins DA, Miselis RR. Viscerotopic representation of the upper alimentary tract in the rat: sensory ganglia and nuclei of the solitary and spinal trigeminal tracts. J Comp Neurol. 1989;283:248–268. doi: 10.1002/cne.902830207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschuler SM, Ferenci DA, Lynn RB, Miselis RR. Representation of the cecum in the lateral dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve and commissural subnucleus of the nucleus tractus solitarii in rat. J Comp Neurol. 1991;304:261–274. doi: 10.1002/cne.903040209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KD. Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:1371–1383. doi: 10.1089/neu.2004.21.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KD, Borisoff JF, Johnson RD, Stiens SA, Elliott SL. Long-term effects of spinal cord injury on sexual function in men: implications for neuroplasticity. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:338–348. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azami J, Wright DM, Roberts MH. Effects of morphine and naloxone on the responses to noxious stimulation of neurones in the nucleus reticularis paragigantocellularis. Neuropharmacology. 1981;20:869–876. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(81)90080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein CN, Niazi N, Robert M, Mertz H, Kodner A, Munakata J, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. Rectal afferent function in patients with inflammatory and functional intestinal disorders. Pain. 1996;66:151–161. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodner DR, Lindan R, Leffler E, Kursh ED, Resnick MI. The application of intracavernous injection of vasoactive medications for erection in men with spinal cord injury. J Urol. 1987;138:310–311. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)43130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson F. Histotechnology: A Self-Instructional Text. Chicago: American Society of Clinical Pathologists; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cechetto DF. Central representation of visceral function. Fed Proc. 1987;46:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Schwartz-Giblin S, Pfaff DW. Effects of total and partial spinal transections on the pudendal nerve- evoked response in rat lumbar axial muscle. Brain Res. 1987;401:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coolen LM, Allard J, Truitt WA, McKenna KE. Central regulation of ejaculation. Physiol Behav. 2004;83:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cothron KJ, Massey JM, Onifer SM, Hubscher CH. Identification of penile inputs to the rat gracile nucleus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1015–1023. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00656.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groat WC, Kruse MN, Vizzard MA, Cheng CL, Araki I, Yoshimura N. Modification of urinary bladder function after spinal cord injury. Adv Neurol. 1997;72:347–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditunno PL, Patrick M, Stineman M, Ditunno JF. Who wants to walk? Preferences for recovery after SCI: a longitudinal and cross-sectional study. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:500–506. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond GB. Reporting ethical matters in The Journal of Physiology: standards and advice. J Physiol. 2009;587:713–719. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerridzen RG, Thijssen AM, Dehoux E. Risk factors for upper tract deterioration in chronic spinal cord injury patients. J Urol. 1992;147:416–418. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesler GJ, Jr, Spiel HR, Willis WD. Organization of spinothalamic tract axons within the rat spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1981;195:243–252. doi: 10.1002/cne.901950205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano F, Rampin O. Neural control of erection. Physiol Behav. 2004;83:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick ME, Meshkinpour H, Haldeman S, Hoehler F, Downey N, Bradley WE. Colonic dysfunction in patients with thoracic spinal cord injury. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:287–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein I. Evaluation of penile nerves. In: Tanagho TF, Lue TF, McClure RD, editors. Contemporary Management of Impotence and Infertility. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1988. pp. 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hackler RH. A 25-year prospective mortality study in the spinal cord injured patient: comparison with the long-term living paraplegic. J Urol. 1977;117:486–488. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)58506-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart BL, Leedy MG. Neurological bases of male sexual behaviour: a comparative analysis. In: Adler N, Pfaff D, Goy RW, editors. Handbook of Behavioural Neurobiology. New York: Plenum Press; 1985. pp. 373–422. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes GM, Sachs BD. The ejaculatory reflex in copulating rats: normal bulbospongiosus activity without apparent urethral stimulation. Neurosci Lett. 1991;125:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90026-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubscher CH, Berkley KJ. Responses of neurons in caudal solitary nucleus of female rats to stimulation of vagina, cervix, uterine horn and colon. Brain Res. 1994;664:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91946-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubscher CH, Johnson RD. Responses of medullary reticular formation neurons to input from the male genitalia. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:2474–2482. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.4.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubscher CH, Johnson RD. Changes in neuronal receptive field characteristics in caudal brain stem following chronic spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 1999a;16:533–541. doi: 10.1089/neu.1999.16.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubscher CH, Johnson RD. Effects of acute and chronic midthoracic spinal cord injury on neural circuits for male sexual function. I. Ascending pathways. J Neurophysiol. 1999b;82:1381–1389. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.3.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubscher CH, Johnson RD. Effects of acute and chronic midthoracic spinal cord injury on neural circuits for male sexual function. II. Descending pathways. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:2508–2518. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubscher CH, Johnson RD. Differential effects of chronic spinal hemisection on somatic and visceral inputs to caudal brainstem. Brain Res. 2002;947:234–242. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02930-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubscher CH, Johnson RD. Effects of chronic dorsal column lesions on pelvic viscerosomatic convergent medullary reticular formation neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:3596–3600. doi: 10.1152/jn.00310.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubscher CH, Johnson RD. Chronic spinal cord injury induced changes in the responses of thalamic neurons. Exp Neurol. 2006;197:177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubscher CH, Kaddumi EG, Johnson RD. Brain stem convergence of pelvic viscerosomatic inputs via spinal and vagal afferents. Neuroreport. 2004;15:1299–1302. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000128428.74337.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean A. The nucleus tractus solitarius: neuroanatomic, neurochemical and functional aspects. Arch Int Physiol Biochim Biophys. 1991;99:A3–52. doi: 10.3109/13813459109145916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RD. Efferent modulation of penile mechanoreceptor activity. In: Iggo A, Hamann W, editors. Progress in Brain Research Transduction and Cellular Mechanisms in Sensory Receptors. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1988. pp. 319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RD. Descending pathways modulating the spinal circuitry for ejaculation: effects of chronic spinal cord injury. In: Weaver LC, Polosa C, editors. Autonomic Dysfunction After Spinal Cord Injury. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 401–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RD, Halata Z. Topography and ultrastructure of sensory nerve endings in the glans penis of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1991;312:299–310. doi: 10.1002/cne.903120212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RD, Hubscher CH. Brainstem microstimulation differentially inhibits pudendal motoneuron reflex inputs. Neuroreport. 1998;9:341–345. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199801260-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RD, Hubscher CH. Brainstem microstimulation activates sympathetic fibres in pudendal nerve motor branch. Neuroreport. 2000;11:379–382. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200002070-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RD, Murray FT. Reduced sensitivity of penile mechanoreceptors in aging rats with sexual dysfunction. Brain Res Bull. 1992;28:61–64. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90231-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaddumi EG, Hubscher CH. Convergence of multiple pelvic organ inputs in the rat rostral medulla. J Physiol. 2006;572:393–405. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.102574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaddumi EG, Hubscher CH. Urinary bladder irritation alters efficacy of vagal stimulation on rostral medullary neurons in chronic T8 spinalized rats. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1219–1228. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchell RL, Gilanpour H, Johnson RD. Electrophysiologic studies of penile mechanoreceptors in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1982;75:229–244. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(82)90021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo WE, Ballantyne GH, Modlin IM. The colon, anorectum, and spinal cord patient. A review of the functional alterations of the denervated hindgut. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:261–267. doi: 10.1007/BF02554543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna L. Manual of Histologic Staining Methods of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. New York: McGraw Hill; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonagh R, Sun WM, Thomas DG, Smallwood R, Read NW. Anorectal function in patients with complete supraconal spinal cord lesions. Gut. 1992;33:1532–1538. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.11.1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marson L, McKenna KE. The identification of a brainstem site controlling spinal sexual reflexes in male rats. Brain Res. 1990;515:303–308. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90611-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslany S, Crockett DP, Egger MD. Somatotopic organization of the dorsal column nuclei in the rat: transganglionic labelling with B-HRP and WGA-HRP. Brain Res. 1991;564:56–65. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91351-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren R. Projections from the nucleus of the solitary tract in the rat. Neuroscience. 1978;3:207–218. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(78)90102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novin D, Rogers RC, Hermann G. Visceral afferent and efferent connections in the brain. Diabetologia. 1981;20(Suppl):331–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez R, Gross GH, Sachs BD. Origin and central projections of rat dorsal penile nerve: possible direct projection to autonomic and somatic neurons by primary afferents of nonmuscle origin. J Comp Neurol. 1986;247:417–429. doi: 10.1002/cne.902470402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastelin CF, Zempoalteca R, Pacheco P, Downie JW, Cruz Y. Sensory and somatomotor components of the ‘sensory branch’ of the pudendal nerve in the male rat. Brain Res. 2008;1222:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patki P, Woodhouse J, Hamid R, Craggs M, Shah J. Effects of spinal cord injury on semen parameters. J Spinal Cord Med. 2008;31:27–32. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2008.11753977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschanski M, Besson JM. A spino-reticulo-thalamic pathway in the rat: an anatomical study with reference to pain transmission. Neuroscience. 1984;12:165–178. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy DC, Awad SA, Downie JW. External sphincter dyssynergia: an abnormal continence reflex. J Urol. 1988;140:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)41499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs BD, Bitran D. Spinal block reveals roles for brain and spinal cord in the mediation of reflexive penile erections in rats. Brain Res. 1990;528:99–108. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90200-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs BD, Meisel RL. The physiology of male sexual behaviour. In: Knobil E, Neill JD, editors. The Physiology of Reproduction. New York: Raven; 1988. pp. 1393–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkarati M, Rossier AB, Fam BA. Experience in vibratory and electro-ejaculation techniques in spinal cord injury patients: a preliminary report. J Urol. 1987;138:59–62. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)42988-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh M, Akaike A, Takagi H. Excitation by morphine and enkephalin of single neurons of nucleus reticularis paragigantocellularis in the rat: a probable mechanism of analgesic action of opioids. Brain Res. 1979;169:406–410. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)91043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seftel AD, Oates RD, Krane RJ. Disturbed sexual function in patients with spinal cord disease. Neurol Clin. 1991;9:757–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semens JH. Premature ejaculation: a new approach. South Med J. 1956;49:353–357. doi: 10.1097/00007611-195604000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta JN, Gebhart GF. Mechanosensitive afferent fibres in the gastrointestinal and lower urinary tracts. In: Gebhart GF, editor. Visceral Pain. Seattle: IASP Press; 1995. pp. 75–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sonksen J, Ohl DA. Penile vibratory stimulation and electroejaculation in the treatment of ejaculatory dysfunction. Int J Androl. 2002;25:324–332. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2002.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ver Voort SM. Infertility in spinal-cord injured male. Urology. 1987;29:157–165. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(87)90145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva L, Le Bars D. The activation of bulbo-spinal controls by peripheral nociceptive inputs: diffuse noxious inhibitory controls. Biol Res. 1995;28:113–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins LR, Faris PL, Komisaruk BR, Mayer DJ. Dorsolateral funiculus and intraspinal pathways mediate vaginal stimulation-induced suppression of nociceptive responding in rats. Brain Res. 1984;294:59–65. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)91309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalla SV, Blunt KJ, Fam BA, Constantinople NL, Gittes RF. Detrusor-urethral sphincter dyssynergia. J Urol. 1977;118:1026–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)58286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yells DP, Hendricks SE, Prendergast MA. Lesions of the nucleus paragigantocellularis: effects on mating behaviour in male rats. Brain Res. 1992;596:73–79. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91534-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YP, Iannotti C, Shields LB, Han Y, Burke DA, Xu XM, Shields CB. Dural closure, cord approximation, and clot removal: enhancement of tissue sparing in a novel laceration spinal cord injury model. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:343–352. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.100.4.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo M, Gebhart GF. Characterization of descending inhibition and facilitation from the nuclei reticularis gigantocellularis and gigantocellularis pars alpha in the rat. Pain. 1990;42:337–350. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)91147-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]