Abstract

The nature of protease-activated receptors (PARs) capable of activating respiratory vagal C-fibres in the mouse was investigated. Infusing thrombin or trypsin via the trachea strongly activated vagal lung C-fibres with action potential discharge, recorded with the extracellular electrode positioned in the vagal sensory ganglion. The intensity of activation was similar to that observed with the TRPV1 agonist, capsaicin. This was mimicked by the PAR1-activating peptide TFLLR-NH2, whereas the PAR2-activating peptide SLIGRL-NH2 was without effect. Patch clamp recording on cell bodies of capsaicin-sensitive neurons retrogradely labelled from the lungs revealed that TFLLR-NH2 consistently evokes a large inward current. RT-PCR revealed all four PARs were expressed in the vagal ganglia. However, when RT-PCR was carried out on individual neurons retrogradely labelled from the lungs it was noted that TRPV1-positive neurons (presumed C-fibre neurons) expressed PAR1 and PAR3, whereas PAR2 and PAR4 were rarely expressed. The C-fibres in mouse lungs isolated from PAR1−/− animals responded normally to capsaicin, but failed to respond to trypsin, thrombin, or TFLLR-NH2. These data show that the PAR most relevant for evoking action potential discharge in vagal C-fibres in mouse lungs is PAR1, and that this is a direct neuronal effect.

Introduction

Sensory nociceptors provide an organ with a sense of its own potential damage. As such they play an important protective role in initiating sensations and reflexes aimed at limiting a damaging stimulus. Impulses in vagal nociceptive bronchopulmonary C-fibres are transmitted to the CNS where they are integrated, processed, and may lead to coughing, dyspnoea, reflex mucus secretion and reflex bronchospasm. Inappropriate activation of nociceptors, however, can lead to sensations and reflexes that are out of balance with their protective function. A substantial body of evidence is accumulating that indicates that exaggerated or inappropriate activity in bronchopulmonary vagal nociceptive C-fibres contributes to many of the signs and symptoms of inflammatory airway diseases (Undem & Carr, 2002; Undem & Kollarik, 2005). Circumstantial evidence supports the hypothesis that vagal C-fibre activity in the inflamed airways is enhanced due to the presence of certain neuroactive inflammatory mediators (Lee et al. 2002). The nature of these mediators, however, remains ill defined. Regrettably, there have been relatively few studies of any type on the regulation of bronchopulmonary C-fibres in the mouse; a species commonly used in the study of inflammatory airway diseases. In this study we address the hypothesis that proteases associated with airway inflammation that stimulate protease-activated receptors (PARs) can lead directly to bronchopulmonary C-fibre activation and action potential discharge in the mouse.

There are at least four subtypes of PARs (Barry et al. 2006). These G-protein-coupled receptors are characterized by the paradoxical fact that the activating ‘agonist’ is part of the receptor. To activate these receptors, a protease cleaves the extracellular N-terminus, thereby exposing the activating ligand (commonly referred to as the ‘tethered ligand’). Thrombin enzymatically activates PAR1, PAR3 and PAR4. Trypsin non-selectively activates all PARs. Mast cell tryptase selectively activates PAR2. Once activated, the PARs modulate cell function through G-protein-directed signal transduction pathways (Barry et al. 2006). Among the PARs, PAR2 has received the most attention with respect to nociceptive nerves (Steinhoff et al. 2000; Amadesi et al. 2004, 2006; Gu & Lee, 2006, 2009). PAR1 activation, however, has also been shown to increase calcium in cultured dorsal root ganglion neurons, and cause plasma extravasation in visceral tissues via a neurogenic mechanism (de Garavilla et al. 2001). In the respiratory system, selective PAR2 agonists have been found to increase the excitability of bronchopulmonary C-fibres in the rat (Gu & Lee, 2006), and lead to an increase in cough sensitivity in guinea pigs (Gatti et al. 2006). Selective PAR2 agonists were found ineffective, however, at overtly evoking action potential discharge in guinea pig bronchopulmonary vagal fibres (Carr et al. 2000). PAR2 stimulation may indirectly increase excitability of these nerves via the release of neuroactive prostanoids from the airway epithelium (Cocks et al. 1999). Indeed, the PAR2-mediated increase in cough sensitivity is blocked by cyclooxygenase inhibitors (Gatti et al. 2006).

In the present study we combine extracellular recording techniques with patch clamp electrophysiology and single-cell gene expression analysis to characterize the most relevant PARs with respect to direct activation of bronchopulmonary C-fibres in mouse vagal bronchopulmonary C-fibres. The data support the hypothesis that PAR1 activation by trypsin, thrombin and selective PAR1 activators directly activates the C-fibres, whereas PAR2 activators are without effect.

Methods

Animal experiments

Experiments were performed on C57BL6 mice (wild-type and PAR1−/− and TRPV1−/−; males 6–8 weeks old) with approval from the Johns Hopkins Animal Use and Care Committee. The animals were purchased from Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME, USA. The PAR1−/− mice were developed and obtained from Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development, L.L.C.

Extracellular recording

The animals were killed by CO2 inhalation followed by exsanguination. The innervated isolated trachea/lung preparation was prepared as previously described (Kollarik et al. 2003). Briefly, the airways and lungs with their intact right-side extrinsic innervation (vagus nerve including jugular/nodose ganglia) were taken and placed in a dissecting dish with Krebs bicarbonate buffer solution composed of (mm): 118 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.9 CaCl2, 25.0 NaHCO3 and 11.1 dextrose, and equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (pH 7.2–7.4). Connective tissue was trimmed away leaving the larynx, trachea and lungs with their intact nerves. The airways were then pinned to the larger compartment of a custom-built two-compartment recording chamber which was lined with silicone elastomer (Sylgard). The tissue was perfused via the trachea (∼1 ml min−1) with the Krebs solution (37°C). The right jugular/nodose ganglion was gently pulled into the adjacent compartment of the chamber through a small hole and pinned. The ganglion compartment was separately superfused with the buffer with a flow rate which was warmed by a warming jacket to keep airway tissues and ganglia at 37°C. A sharp glass electrode was pulled by a Flaming/Brown micropipette puller (P-87; Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA) and filled with 3 m NaCl solution. The electrode was gently inserted into the jugular/nodose ganglion so as to be placed near the cell bodies. The recorded action potentials were amplified (Microelectrode AC amplifier 1800; A-M Systems, Everett, WA, USA), filtered (0.3 kHz of low cut-off and 1 kHz of high cut-off), and monitored on an oscilloscope (TDS340; Tektronix, Beaverton, OR, USA) and a chart recorder (TA240; Gould, Valley View, OH, USA). The scaled output from the amplifier was captured and analysed by a Macintosh computer using NerveOfIt software (Phocis, Baltimore, MD, USA). For measuring conduction velocity, an electrical stimulation (S44; Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA, USA) was applied on the core of the receptive field. The conduction velocity was calculated by dividing the distance along the nerve pathway by the time delay between the shock artifact and the action potential evoked by electrical stimulation. If a C-fibre (<1 m s−1) was found, the recording was started. Drugs or vehicle were introduced into the perfusion solution entering the trachea at a volume of 1 ml delivered over a period of 15 s. The action potential discharge was quantified in 1 s bins. The response was considered to have terminated when the discharge returned back to <0.5 action potentials over the baseline. Baseline was typically very low (0–1 Hz). The data are reported as peak frequency (peak number of action potentials in any 1 s bin), and total number of action potentials evoked.

Whole-cell patch clamp recording

The jugular/nodose neurons labelled from the airways were identified by fluorescence microscopy using 560 nm of excitation filter and 480 nm of emission filter as previously described (Kwong et al. 2008). To maintain intracellular signal pathways and a native intracellular Cl− concentration, a gramicidin-perforated whole-cell patch-clamp technique was employed using a Multiclamp 700A amplifier and Axograph 4.9 software (Axon Instruments). A pipette (1.5–3 MΩ) was filled with a pipette solution composed of (mm): 140 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 2MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 11 EGTA and 10 dextrose; titrated to pH 7.3 with KOH; 304 mosmol l−1. Gramicidin was dissolved in DMSO and mixed with the pipette solution for a final concentration of 1 μg ml−1 just prior to each recording. Cell membrane potential was held at −60 mV. During the experiments, the cells were continuously superfused (6 ml min−1) by gravity with Locke solution; composition (mm): 136 NaCl, 5.6 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.2 CaCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 14.3 NaHCO3 and 10 dextrose (pH 7.3–7.4). In order to stimulate the cells, vehicle (0.1% ethanol), TFLLR-NH2 (10 μm) and capsaicin (1 μm) were added to the buffer. All recordings were performed at 35°C.

Retrograde labelling and cell dissociation

Bronchopulmonary afferent neurons of C57BL/6 mice (male, 6–8 weeks) were retrogradely labelled using DiI (DiC18(3); MolecularProbes, Eugene, OR, USA) solution (0.1%, 50 μl; dissolved in 10% DMSO and 90% normal saline) as previously described (Nassenstein et al. 2008). Under anaesthesia (2 mg ketamine and 0.2 mg xylazine per mouse, i.p.), mice were orotracheally intubated, and DiI was instilled into the tracheal lumen 5–9 days before an experiment.

After the animals were killed by CO2 inhalation and exsanguination, the jugular/nodose ganglia were dissected and cleared of adhering connective tissue. Isolated ganglia were incubated in the enzyme buffer (2 mg ml−1 collagenase type 1A and 2 mg ml−1 dispase II in Ca2+-, Mg2+-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution) for 30 min at 37°C. Neurons were dissociated by trituration with three glass Pasteur pipettes of decreasing tip pore size, then washed by centrifugation (three times at 1000 g for 2 min) and suspended in L-15 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cell suspension was transferred onto poly-d-lysine/laminin-coated coverslips. After the suspended neurons had adhered to the coverslips for 2 h, the neuron-attached coverslips were flooded with the L-15 medium (10% FBS) and used within 8 h.

Single-cell RT-PCR

Single-cell PCR was performed as described previously (Nassenstein et al. 2008). First strand cDNA was synthesized from single lung-labelled jugular/nodose cells by using the SuperScript III CellsDirect cDNA Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Cell picking

Coverslips of retrogradely labelled, dissociated neurons were constantly perfused by Locke solution and identified by using fluorescence microscopy. Single cells were harvested into a glass-pipette (tip diameter 50–150 μm) pulled with a micropipette puller (Model P-87, Sutter Instruments Company) by applying negative pressure. The pipette tip was then broken in a PCR tube containing an RNase inhibitor (RNaseOUT, 2 U μl−1), immediately snap frozen and stored on dry ice. From one coverslip, 1–4 cells were collected. A sample of the bath solution from the vicinity of a labelled neuron was collected from each coverslip for no-template experiments (bath control).

RT-PCR

Samples were defrosted, lysed (10 min at 75°C) and treated with DNase I. Then, poly(dT) and random hexamer primers (Roche Applied Bioscience) were added. Half of the volume was reverse transcribed by adding Superscript III RT for cDNA synthesis, whereas water was added to the remaining sample, which was used in the following as –RT control.

PCR

Three microlitres of each sample (cDNA, –RT control or bath control, respectively) were used for PCR amplification of mouse β-actin, TRPV1 and PAR1–4 receptors by the HotStarTaq Polymerase Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations in a final volume of 20 μl. After an initial activation step at 95°C for 15 min, cDNAs were amplified with custom-synthesized primers (Invitrogen) (Table 1) by 45 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 1 min followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Products were then visualized in ethidum bromide-stained 1.5% agarose gels. Primers for β-actin, TRPV1 and PAR1 were intron-spanning and the primers for PAR2 were exon junction-spanning primers. Primers for PAR3 and PAR4 were not intron spanning.

Table 1.

Sequence of primers used for analysis of murine PAR1–4 transcripts

| Gene | Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | GenBank | Product length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | Forward | CTG GTC GTC GAC AAC GGC TCC | NM_007393 | 238 bp |

| Reverse | GCC AGA TCT TCT CCA TG | |||

| TRPV1 | Forward | TCA CCG TCA GCT CTG TTG TC | NM_001001445 | 229 bp |

| Reverse | GGG TCT TTG AAC TCG CTG TC | |||

| PAR1 | Forward | AGC CAG CCA GAA TCA GAG AG | NM_010169 | 206 bp |

| Reverse | TCG GAG ATG AAG GGA GGA G | |||

| PAR2 | Forward | GGA CGC AAC AAC AGT AAA GGA | NM_007974 | 289 bp |

| Reverse | CAG AGA GGA GGT CAG CCA AG | |||

| PAR3 | Forward | AGA CAA CTC AGC AAA GCC AAC | NM_010170 | 243 bp |

| Reverse | TAG CCC TCT GCC TTT TCT TCT | |||

| PAR4 | Forward | AGC CGA AGT CCT CAG ACA AG | NM_007975 | 303 bp |

| Reverse | GCA AGT GGT AAG CCA GTC GT |

Drugs and solutions

Capsaicin, bovine trypsin (12,700 units ml−1) and bovine thrombin (50% protein) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company. SLIGRL-NH2 (70.3%) and TFLLR-NH2 (74%) were obtained from Tocris Bioscience. Capsaicin was made up as a 10 mm stock solution in ethanol. SLIGRL-NH2 and TFLLR-NH2 were made up as 1 mm stock solution in distilled water. Trypsin was made up as a 10 mg ml−1 solution and thrombin as a 10 mm solution in distilled water.

Results

Extracellular recordings

Wild-type mice

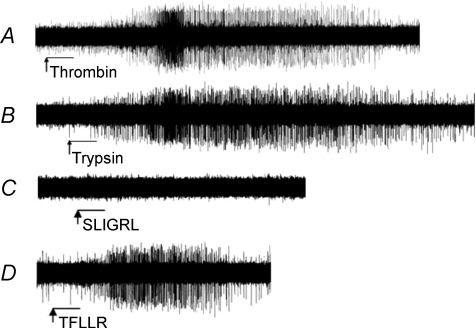

The data with extracellular recordings are illustrated in Fig. 1 and summarized in Table 2. We first evaluated the effect of the non-selective PAR agonist trypsin on intrapulmonary vagal C-fibres in the mouse. Trypsin (10 μg ml−1) was a strong stimulator of capsaicin-sensitive C-fibres activating 28 of 29 C-fibres with a peak frequency of discharge averaging 8.5 ± 1.5 Hz and a total discharge of 279 ± 55 action potentials. Trypsin was less consistent in activating capsaicin-insensitive fibres stimulating action potential discharge in only 3 of 6 nerves with a total number of action potentials in these three fibres averaging 101 ± 39.

Figure 1. Activation of PAR1-evoked action potential discharge in mouse nodose/jugular ganglion C-fibres.

Single-fibre recordings in the isolated perfused lung preparation illustrating that thrombin (A; 10 μg ml−1) and trypsin (B; 10 μg ml−1) delivered to the mouse lung elicit action potential discharge in C-fibres of the vagal ganglia. The PAR2-activating peptide SLIGRL-NH2 (10 μm, n= 9; 100 μm, n= 6) did not elicit action potential discharge in these fibres (C); however, activation of the PAR1 receptor with its activating peptide TFLLR-NH2 (D; 10 μm) did. Arrow and bar indicate start and duration (0.5 min), respectively, of the perfusion of drugs into the trachea. The action potential discharge is quantified in Table 2.

Table 2.

Action potential discharge evoked by PAR activation in mouse capsaicin-sensitive bronchopulmonary C-fibres

| Action potentials |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak frequency | Total number | n | |

| Wild-type | |||

| Trypsin | 8.5 ± 1.5 Hz | 279 ± 55 | 28/29 |

| Thrombin | 7.9 ± 1.6 Hz | 256 ± 71 | 15/17 |

| SLIGRL-NH2 | 0 Hz | 0 | 0/15 |

| TFLLR-NH2 | 8 ± 2 Hz | 85 ± 30 | 11/14 |

| PAR1 knockout | |||

| Trypsin | 0 Hz | 0 | 0/4 |

| Thrombin | 0 Hz | 0 | 0/4 |

| TFLLR-NH2 | 0 Hz | 0 | 0/4 |

| I-RTX treated | |||

| Trypsin | 5 ± 1 Hz | 170 ± 63 | 6/6 |

| Thrombin | 6 ± 1 Hz | 230 ± 63 | 5/5 |

| TFLLR-NH2 | 4 ± 0.6 Hz | 96 ± 31 | 5/7 |

| TRPV1 knockout | |||

| TFLLR-NH2 | 13 ± 4 Hz | 254 ± 68 | 6/6 |

The data were obtained from C-fibres that responded to capsaicin after the end of the experiment. In the I-RTX-treated fibres and fibres from TRPV1−/− animals there was no response to capsaicin; in these studies only fibres with conduction velocities of <0.6 m s−1 were included as we have previously found that these nerves are virtually uniformly responsive to capsaicin. Trypsin (10 μg ml−1), thrombin (10 μg ml−1), TFLLR-NH2 (10 μm) and SLIGRL-NH2 (10 μm, n= 9; and 100 μm, n= 6) were administered via tracheal perfusion in 1 ml volume. The ‘n’ value shows number of C-fibres that responded/total number studied. Only one lung C-fibre was studied per mouse.

We next evaluated the effect of the PAR1 and PAR3 agonist thrombin on intrapulmonary capsaicin-sensitive C-fibres in the mouse. Thrombin (10 μg ml−1) mimicked the effect of trypsin stimulating 15 of 17 capsaicin-sensitive C-fibres with a peak frequency of 7.9 ± 1.6 Hz and a total number of action potentials averaging 256 ± 71. Thrombin weakly stimulated only 1 of 4 capsaicin-insensitive fibres.

The data with the proteases indicated that PAR1 (or PAR3) is more likely to account for the C-fibre activation than PAR2. To further address this hypothesis we evaluated selective PAR2- and PAR1-activating peptides. In nine experiments, the PAR2-selective activating peptide SLIGRL-NH2 (10 μm) failed to evoke action potential discharge in capsaicin-sensitive C-fibres. Subsequent addition of trypsin led to strong activation of all nine of these fibres with a peak frequency of 5 ± 0.5 Hz. By contrast, the PAR1-selective activating peptide TFLLR-NH2 (10 μm) consistently activated C-fibres, stimulating action potentials in 11 of 14 fibres with a peak frequency of 8 ± 2 Hz. We next addressed the concern of whether 10 μm was an insufficient concentration of SLIGRL-NH2 to evoke a PAR2-mediated response. In five experiments the concentration of SLIGRL-NH2 was increased to 100 μm. None of the five fibres under study responded to SLIGRL-NH2 (100 μm), but each responded to TFLLR-NH2 (9 ± 5 Hz).

PAR1−/− mice

A capsaicin-sensitive intrapulmonary C-fibre was studied in each of four PAR1−/− mice. None of these four fibres responded to TFLLR-NH2 (10 μm). These fibres also failed to respond to trypsin (10 μg ml−1), or thrombin (10 μg ml−1). At the end of each experiment capsaicin stimulated all four fibres with an average peak frequency of 23 ± 4 Hz.

Lack of a role for TRPV1

PAR activators have been shown to increase TRPV1 responses in sensory C-fibre nerves. We therefore addressed the hypothesis that the PAR1-mediated activation of capsaicin-sensitive nerves involved TRPV1. Blocking TRPV1 with 5′-iodoresiniferatoxin (I-RTX; 1 μm) abolished the response to capsaicin, but did not inhibit the response of the nerve to trypsin, thrombin, or TFLLR (Table 2). Likewise, the bronchopulmonary C-fibres studied from TRPV1−/− mice also responded strongly to TFLLR (Table 2). In these studies we studied only C-fibres that conducted action potentials slower than 0.6 m s−1 as we have previously found these to be uniformly capsaicin sensitive (Kollarik et al. 2003).

Patch clamp recordings

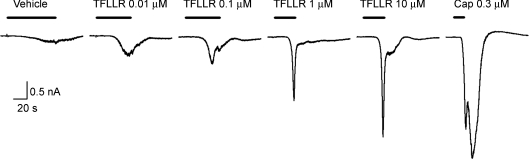

Neurons in the vagal sensory ganglia retrogradely labelled from the lungs were selected and studied using conventional perforated patch clamp techniques. Consistent with the ex vivo lung preparation, TFLLR-NH2 (10 μm) consistently elicited a robust inward current of –29.8 ± 13.2 pA pF−1 (n= 6; Fig. 2). The threshold for activation was approximately 0.01 μm (data not shown). For comparison, capsaicin (1 μm) evoked a larger inward current in these neurons that averaged −150 ± 60 pA pF−1.

Figure 2. Inward currents elicited by activation of PAR1 in a capsaicin-sensitive mouse lung-specific jugular/nodose ganglion neuron.

Whole-cell patch clamp recording in a perforated patch configuration showing that TFLLR-NH2 (PAR1-activating peptide) elicited an inward current. Holding potential was −60 mV. Membrane capacitance was 15.8 pF. Drugs were delivered at the noted concentration via superfusion solution (bar). The response to 10 μm TFLLR-NH2 is represented by 6 additional experiments with capsaicin (1 μm)-sensitive neurons in which the current density averaged −29.8 ± 13.2 pA pF−1. TFLLR-NH2 (10 μm) did not evoke an inward current in capsaicin-insensitive neurons (0/7 neurons studied).

Single-cell RT-PCR

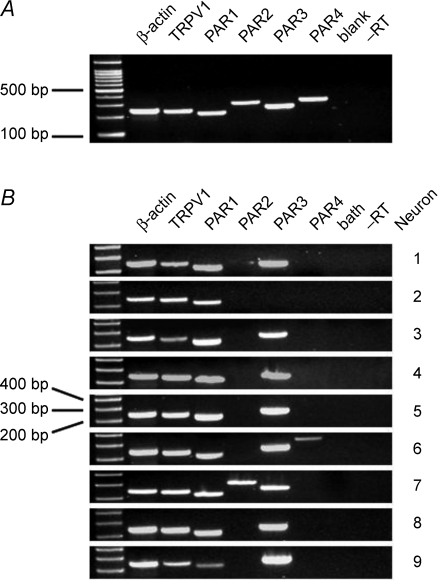

We evaluated gene expression in nine neurons retrogradely labelled from the lungs of three animals (Fig. 3). We pre-selected the neurons first based on a screen for TRPV1 expression so we could focus our testing on presumed capsaicin-sensitive bronchopulmonary C-fibre neurons. The retrogradely labelled neurons were individually isolated and, after reverse transcription, PCR was performed using β-actin-, TRPV1- and PAR1–4-specific primers. PAR1 and PAR3 mRNA expression could be observed in all investigated TRPV1+ cells (9 of 9 neurons). PAR2 and PAR4 mRNA expression was detected in only 1 out of 9 cells. No specific PCR products were seen in –RT controls of each individual cell and bath controls, whereas β-actin-, TRPV1- and PAR1–4-mRNA could be consistently amplified from the cDNA of a whole vagal ganglion which was used as positive control. An additional five TRPV1-expressing neurons were evaluated only for PAR2 expression, all five neurons were negative (not shown), thus PAR2 expression was observed in only 1 of 14 TRPV1-expressing neurons.

Figure 3. Lung-specific, TRPV1+ mouse jugular/nodose ganglion neurons express PAR1 and PAR3 mRNA.

A, conventional RT-PCR showing that PAR1–4 mRNA are expressed in a mouse jugular nodose ganglion complex. ‘blank’ indicates lane was not loaded with PCR product. –RT indicates RNA control of β-actin. B, single-cell RT-PCR showing the distribution of PAR1, PAR2, PAR3 and PAR4 mRNA in individual TRPV1+ lung-specific cells isolated from the mouse jugular/nodose ganglion complex. ‘bath’ indicates RT-PCR processed with the solution in which cells were perfused during cell picking. –RT indicates RNA control of β-actin.

Discussion

The data presented in this study show that the major PAR involved in mouse bronchopulmonary C-fibre activation is PAR1. PAR1 is both necessary and sufficient for trypsin- and thrombin-induced action potential discharge in these fibres. The data also support the hypothesis that this is a direct effect of interacting with PAR1 receptors in the C-fibre membranes.

Trypsin, a non-selective PAR agonist (Steinhoff et al. 2000), evoked relatively high frequency action potential discharge in the mouse bronchopulmonary capsaicin-sensitive C-fibres. This was mimicked by thrombin, an agonist at PAR1 and PAR3 receptors. The PAR1-activating peptide also mimicked the effect of trypsin in evoking action potential discharge in capsaicin-sensitive C-fibres, but the PAR2-selective activating peptide had no effect. Taken together these data support the hypothesis that PAR1 is involved in the trypsin- and thrombin-induced response. That PAR1 is necessary for the protease activation of bronchopulmonary C-fibres is supported by the findings that C-fibres in PAR1−/− mice responded normally to capsaicin, but failed to respond to trypsin, thrombin or the selective activating peptides.

PARs are expressed on numerous cell types (Vergnolle, 2009), so it is possible that the effect of PAR activators on sensory nerves may be an indirect effect of mediators released from other cell types. For example PAR2 has been shown to enhance the guinea pig cough response to citric acid, a reflex caused by vagal C-fibre activation. This PAR2-mediated effect, however, is abolished by cyclooxygenase blockade indicating that the response is secondary to prostaglandin production (Gatti et al. 2006). This may be due to PAR2-mediated PGE2 release from airway epithelial cells surrounding the C-fibre terminals (Cocks et al. 1999). The data presented here support the hypothesis that the PAR1-mediated activation of mouse bronchopulmonary C-fibres is due to a direct effect on the nerve terminals. This is supported by the findings that the capsaicin-sensitive neurons retrogradely labelled from the lungs and studied in isolation, responded to the PAR1-activating peptide with an inward (depolarizing current). In addition, when the retrogradely labelled neurons were evaluated for gene expression on a single identified neuron level, it was noted that all of the TRPV1-expressing bronchopulmonary neurons expressed PAR1 (and PAR3).

The role of PAR3 is not clear from these studies. That the PAR1−/− mice failed to respond to trypsin or thrombin indicates that PAR3, if indeed it is expressed at the terminal, is not sufficient to evoke action potential discharge. It remains possible that PAR3 activation may lead to signals that modulate the excitability of the C-fibres, short of overt activation.

In rats PAR2 activation has been shown to amplify the response of DRG neurons and respiratory vagal afferent nerves to TRPV1 activation by capsaicin (Amadesi et al. 2004, 2006; Gu & Lee, 2006, 2009); such an event could go unnoticed in the experimental design used in the present study, as we were evaluating overt action potential discharge and inward currents. The observation that the vast majority of these neurons failed to express PAR2 mRNA nevertheless argues against direct effects of PAR2 in the modulation of mouse bronchopulmonary C-fibres. This may represent a species difference between the mouse and rat. It is unlikely that the PAR1-induced action potential discharge in vagal C-fibres observed in the present study was due to a potentiation of baseline TRPV1 activity, as the action potential discharge was similar in wild-type vs. TRPV1−/− animals and in tissues treated with a TRPV1 antagonist.

The observation that thrombin and trypsin strongly activate mouse vagal bronchopulmonary C-fibres via PAR1 may have implications in inflammatory airway diseases. Trypsin is formed by airway epithelium (Takahashi et al. 2001), and thrombin may be elevated in the airways of asthmatic subjects and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Gabazza et al. 1999; Ashitani et al. 2002). Thrombin activity has also been shown to be elevated 2 days following allergen provocation in atopic asthmatic subjects (Terada et al. 2004). In addition to thrombin and trypsin, there may be other proteases associated with airway inflammation that could lead to PAR1 activation. For example T-lymphocyte-derived granzyme A and neutrophil-derived cathepsin G can activate PAR1. The topic of proteases associated with airway inflammation is nicely reviewed in Lan et al. (2002). Activation of PAR1 by proteases leading to high frequency action potential discharge in airway vagal C-fibres may therefore account for some of the nocifensive reflexes (parasympathetic bronchoconstriction and secretions) and sensations (dyspnoea, urge to cough) that are associated with inflammatory airway diseases.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work is provided by National Institutes of Health (B.J.U.) and American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (K.K.).

References

- Amadesi S, Cottrell GS, Divino L, Chapman K, Grady EF, Bautista F, Karanjia R, Barajas-Lopez C, Vanner S, Vergnolle N, Bunnett NW. Protease-activated receptor 2 sensitizes TRPV1 by protein kinase Cɛ- and A-dependent mechanisms in rats and mice. J Physiol. 2006;575:555–571. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.111534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadesi S, Nie J, Vergnolle N, Cottrell GS, Grady EF, Trevisani M, Manni C, Geppetti P, McRoberts JA, Ennes H, Davis JB, Mayer EA, Bunnett NW. Protease-activated receptor 2 sensitizes the capsaicin receptor transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor 1 to induce hyperalgesia. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4300–4312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5679-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashitani J, Mukae H, Arimura Y, Matsukura S. Elevated plasma procoagulant and fibrinolytic markers in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Intern Med. 2002;41:181–185. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.41.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry GD, Le GT, Fairlie DP. Agonists and antagonists of protease activated receptors (PARs) Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:243–265. doi: 10.2174/092986706775476070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr MJ, Schechter NM, Undem BJ. Trypsin-induced, neurokinin-mediated contraction of guinea pig bronchus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1662–1667. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.5.9912099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocks TM, Fong B, Chow JM, Anderson GP, Frauman AG, Goldie RG, Henry PJ, Carr MJ, Hamilton JR, Moffatt JD. A protective role for protease-activated receptors in the airways. Nature. 1999;398:156–160. doi: 10.1038/18223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Garavilla L, Vergnolle N, Young SH, Ennes H, Steinhoff M, Ossovskaya VS, D’Andrea MR, Mayer EA, Wallace JL, Hollenberg MD, Andrade-Gordon P, Bunnett NW. Agonists of proteinase-activated receptor 1 induce plasma extravasation by a neurogenic mechanism. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:975–987. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabazza EC, Taguchi O, Tamaki S, Takeya H, Kobayashi H, Yasui H, Kobayashi T, Hataji O, Urano H, Zhou H, Suzuki K, Adachi Y. Thrombin in the airways of asthmatic patients. Lung. 1999;177:253–262. doi: 10.1007/pl00007645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti R, Andre E, Amadesi S, Dinh TQ, Fischer A, Bunnett NW, Harrison S, Geppetti P, Trevisani M. Protease-activated receptor-2 activation exaggerates TRPV1-mediated cough in guinea pigs. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:506–511. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01558.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q, Lee LY. Hypersensitivity of pulmonary chemosensitive neurons induced by activation of protease-activated receptor-2 in rats. J Physiol. 2006;574:867–876. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.110312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q, Lee LY. Effect of protease-activated receptor 2 activation on single TRPV1 channel activities in rat vagal pulmonary sensory neurons. Exp Physiol. 2009;94:928–936. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.047712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollarik M, Dinh QT, Fischer A, Undem BJ. Capsaicin-sensitive and -insensitive vagal bronchopulmonary C-fibres in the mouse. J Physiol. 2003;551:869–879. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.042028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong K, Kollarik M, Nassenstein C, Ru F, Undem BJ. P2X2 receptors differentiate placodal vs. neural crest C-fiber phenotypes innervating guinea pig lungs and esophagus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L858–L865. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90360.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan RS, Stewart GA, Henry PJ. Role of protease-activated receptors in airway function: a target for therapeutic intervention? Pharmacol Ther. 2002;95:239–257. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LY, Kwong K, Lin YS, Gu Q. Hypersensitivity of bronchopulmonary C-fibers induced by airway mucosal inflammation: cellular mechanisms. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2002;15:199–204. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2002.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassenstein C, Kwong K, Taylor-Clark T, Kollarik M, Macglashan DM, Braun A, Undem BJ. Expression and function of the ion channel TRPA1 in vagal afferent nerves innervating mouse lungs. J Physiol. 2008;586:1595–1604. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.148379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff M, Vergnolle N, Young SH, Tognetto M, Amadesi S, Ennes HS, Trevisani M, Hollenberg MD, Wallace JL, Caughey GH, Mitchell SE, Williams LM, Geppetti P, Mayer EA, Bunnett NW. Agonists of proteinase-activated receptor 2 induce inflammation by a neurogenic mechanism. Nat Med. 2000;6:151–158. doi: 10.1038/72247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Sano T, Yamaoka K, Kamimura T, Umemoto N, Nishitani H, Yasuoka S. Localization of human airway trypsin-like protease in the airway: an immunohistochemical study. Histochem Cell Biol. 2001;115:181–187. doi: 10.1007/s004180000243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada M, Kelly EA, Jarjour NN. Increased thrombin activity after allergen challenge: a potential link to airway remodeling? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:373–377. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1156OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undem BJ, Carr MJ. The role of nerves in asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2002;2:159–165. doi: 10.1007/s11882-002-0011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undem BJ, Kollarik M. The role of vagal afferent nerves in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:355–360. doi: 10.1513/pats.200504-033SR. discussion 371–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnolle N. Protease-activated receptors as drug targets in inflammation and pain. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;123:292–309. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]