Abstract

Terminally differentiated cells have reduced capacity to repair double strand breaks (DSB), but the molecular mechanism behind this down-regulation is unclear. Here we find that miR-24 is consistently up-regulated during post-mitotic differentiation of hematopoietic cell lines and regulates the histone variant H2AX, a key DSB repair protein that activates cell cycle checkpoint proteins and retains DSB repair factors at DSB foci. The H2AX 3’UTR contains conserved miR-24 binding sites regulated by miR-24. Both H2AX mRNA and protein are substantially reduced during hematopoietic cell terminal differentiation by miR-24 up-regulation both in in vitro differentiated cells and primary human blood cells. miR-24 suppression of H2AX renders cells hypersensitive to γ-irradiation and genotoxic drugs. Antagonizing miR-24 in differentiating cells protects them from DNA damage-induced cell death, while transfecting miR-24 mimics in dividing cells increases chromosomal breaks and unrepaired DNA damage and reduces viability in response to DNA damage. This DNA repair phenotype can be fully rescued by over-expressing miR-24-insensitive H2AX. Therefore, miR-24 up-regulation in post-replicative cells reduces H2AX and thereby renders them highly vulnerable to DNA damage.

Once a cell has terminally differentiated and no longer replicates its DNA, its need to repair DNA damage is reduced. Although ongoing DNA damage from oxidative metabolism and exogenous agents may be similar in dividing and nondividing cells, endogenous double stranded breaks (DSB) that occur during DNA replication and compromise genomic integrity are radically reduced or absent and the danger of propagating damaged chromatin in progeny cells is minimized once a cell has stopped dividing. Nonetheless, cells that do not divide need to maintain the integrity of the genes they transcribe. For some long-lived and essentially irreplaceable cells, such as neurons, DNA repair may be more essential than for short-lived cells, such as terminally differentiated blood cells. Dividing cells handle the risk of creating DSB during DNA replication by expressing and activating the homologous recombination (HR) repair machinery in a cell cycle dependent fashion only during S phase. Moreover, during cell division, DNA damage checkpoint proteins survey for unrepaired DNA damage to prevent cell cycle progression at G1/S and G2/M. As a consequence of their reduced needs for DNA repair, nondividing cells have an attenuated DSB response1.

The molecular mechanisms behind the down-regulation of DNA repair in terminally differentiated cells are not well understood. In some cases, specific repair proteins are down regulated. For instance, Chek1, the orchestrator of cell cycle arrest in response to replication mediated DNA damage in proliferating cells, is not detected in terminally differentiated tissues2. Likewise, E2F1 and p53 expression are down-regulated in terminally differentiated myotubes3, 4. mRNA for Ku, the DNA binding proteins of the DNA-dependent protein kinase, which plays a central role in DSB repair by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ), decreases during differentiation of HL-60 cells into monocytes5. However, other repair pathways besides DSB repair, such as base excision repair (BER) and transcription-coupled repair, which repair lesions of equal importance in nondividing and dividing cells, may be undiminished after terminal differentiation.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are abundant small (~20–22 nts) non-coding RNAs that mediate sequence specific post-transcriptional gene expression 6–8. Bioinformatic studies predict that over 30% of all human genes are targeted by miRNAs9 and they impact a diverse array of biological processes, including development, differentiation, apoptosis and proliferation. Here we have investigated a connection between miRNAs and DNA repair. We found that expression of miR-24 and miRNAs that are clustered with it (members of the miR-23 and miR-27 families) is consistently up-regulated during the terminal differentiation of two multipotent hematopoietic cell lines into multiple lineages. The histone variant, H2AX, a key DSB repair protein is a predicted target gene of miR-24. One of the earliest events in the DSB response is phosphorylation of H2AX at Ser139 by members of the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase-like family of kinases10. Phosphorylated H2AX (termed γ-H2AX) participates in DNA repair, replication, and recombination and cell cycle regulation10. The large domains of γ-H2AX generated at each DSB can be visualized by immunostaining as nuclear foci. γ-H2AX foci bind and retain an array of cell cycle and DNA repair factors (cohesins, MDC1, Mre11, BRCA1, 53BP1, etc.) at the break site11, 12. Importantly, loss of a single H2AX allele compromises genomic integrity and enhances cancer susceptibility in mice13, 14. This observation has both clinical and mechanistic implications. The H2AX dosage effect may reflect its structural role in chromatin. H2AX comprises ~15% of cellular H2A, and there are two H2A molecules per nucleosome. Thus, H2AX should be present, on average, in about one of three nucleosomes, and this density is likely reduced in cells with less H2AX, which may interfere with H2AX function. Therefore, a subtle change in cellular H2AX, as might occur with miRNA targeting, may significantly impact DSB repair. Because of the critical role of H2AX in DNA repair and the known consequences of haploinsufficiency, we focused on validating and studying the effect of miR-24 on H2AX.

RESULTS

miR-24 is up-regulated in differentiated blood cells

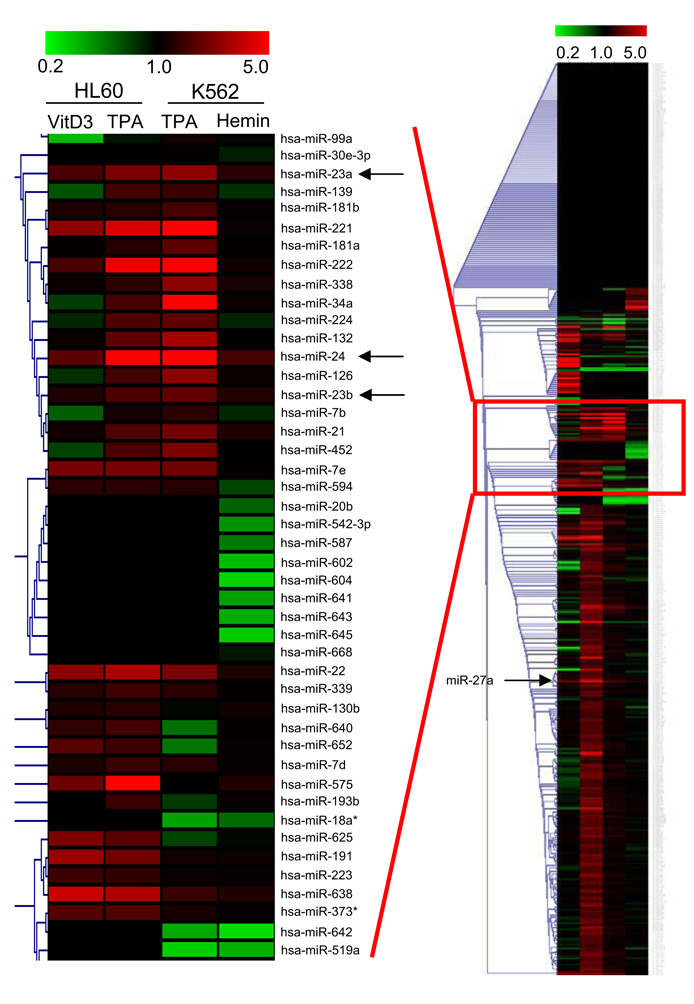

To identify microRNAs (miRNA) regulating DNA repair during terminal hematopoietic cell differentiation, miRNA expression was analyzed by microarray in 2 human leukemia cell lines - K562 cells differentiated to megakaryocytes using 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) or to erythrocytes with hemin, and HL60 cells differentiated to macrophages using TPA or to monocytes using vitamin D3 (Fig. 1). Only a few miRNAs were consistently up-regulated (by at least 40%) in all 4 systems of terminal differentiation – miR-22, miR-125a, and members of the two miR-24 clusters – miR-24, miR-23a, miR-23b and miR-27a. miR-24 stood out as the most up-regulated miRNA. The only member of the 2 miR-24 clusters that was not consistently up-regulated was miR-27b, whose hybridization signal was substantially lower for all conditions than the other cluster members, suggesting that hybridization to that probe was inefficient. We therefore focused our study on miR-24, which we hypothesized might regulate terminal differentiation in nondividing cells across multiple cell lineages.

Fig. 1.

miR-24 is up-regulated during hematopoietic cell differentiation into multiple lineages. Heat map for miRNA expression in HL60 and K562 cells differentiated into 4 different nondividing cell lineages showing single-linkage hierarchical clustering, using Pearson squared as a distance metric. miRNA expression in each lane is analyzed relative to expression in control undifferentiated cells. The highlighted cluster shows miRNAs with similar expression profiles. Range is from ≤5-fold down-regulation (green) to ≤5-fold up-regulation (red). Within the cluster, only miR-22, miR-23a, miR-23b and miR-24 are universally up-regulated across all conditions whereas the remaining miRNA genes in the cluster are down-regulated or unchanged in at least 1 condition. Outside of the cluster, miR-27a and miR-125a are also up-regulated under all conditions. Arrows indicate miR-24 cluster miRNAs.

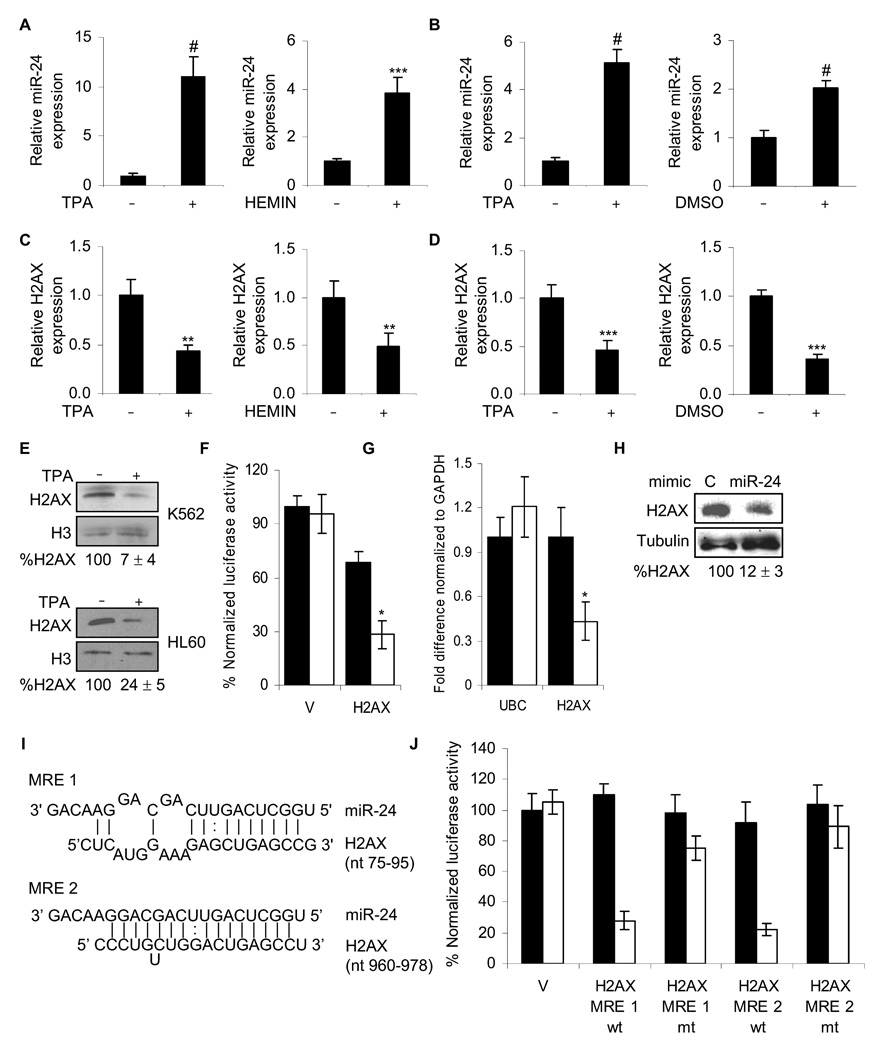

We verified the microarray results by qRT-PCR. miR-24 is consistently up-regulated during terminal differentiation of HL60 and K562, (Fig. 2A, B) and in differentiation of CD8 T cells, muscle cells and embryonic stem cells15–17. One of the biggest challenges in studying miRNAs is to identify target genes and correlate their down-regulation with cellular properties. Computational algorithms have been developed to predict putative miRNA targets based on complementarity to the 3’UTR of the target message, particularly of miRNA nucleotides 2–8 (the “seed” region)18. These tools (TargetScan, PicTar, rna22, miRanda) predict overlapping, but distinct, miR-24 target gene sets18. One strategy to counter this problem is to pursue targets predicted by multiple algorithms, and with high prediction score. The DSB repair gene predicted by all algorithms with a high recognition score was H2AX.

Fig. 2.

miR-24 down-regulates H2AX expression during terminal differentiation. miR-24, analyzed by qRT-PCR relative to U6, increases during differentiation of K562 cells (A) with TPA to megakaryocytes or hemin to erythrocytes (#, p< 0.001, ***, p<0.005) and during differentiation of HL60 cells (B) with TPA to macrophages or DMSO to granulocytes (#, p< 0.001). HL60 cells were treated with TPA for 2 days (left panel) or DMSO for 5 days (right panel) and miR-24 levels analyzed as described above. Under the same differentiating conditions for K562 (C) and HL60 (D) cells, H2AX mRNA, normalized to GAPDH mRNA, is down-regulated (**, p< 0.01, K562; ***, p< 0.005, HL60). (E) H2AX protein decreases after 2 d of TPA differentiation. Relative H2AX expression was quantified by densitometry using H3 as control. Lanes marked by “-” represent cells treated with vehicle alone. (F) miR-24 targets the 3’UTR of H2AX mRNA in a luciferase reporter assay. HepG2 cells were transfected with control miRNA (black) or synthetic miR-24 (white) for 48 hr and then with H2AX 3’UTR-luciferase reporter (H2AX) or vector (V) for 24 hr. Mean ± SD, normalized to vector control, of 3 independent experiments are shown (*, p< 0.001). miR-24 over-expression in HepG2 cells decreases H2AX mRNA, analyzed by qRT-PCR normalized to GAPDH (G; white, miR-24; black, cel-miR-67) and protein (H) 48 hr later. miR-24 over-expression does not alter UBC mRNA levels. (I) Schematic showing the predicted miR-24 binding sites (MRE) in the 3’UTR of H2AX mRNA. (J) Suppression of luciferase activity of a reporter gene containing in its 3’UTR the two predicted miR-24 MRE, either wild-type (wt) or with mutated seed regions (mt). HepG2 cells were transfected with control miRNA (black) or miR-24 mimic (white) for 48 hr and then with the indicated H2AX 3’UTR-luciferase reporters or vector (V). Luciferase activity was assayed 24 hr later. Mean ± SD, normalized to vector control, of 3 independent experiments are shown. In all panels, mean ± SD are shown.

H2AX expression is down-regulated during differentiation

H2AX mRNA and protein declined during K562 and HL60 cell differentiation (Fig. 2C–E). The H2AX transcript can be alternatively processed to a ~1.6 kb replication-independent transcript that has a polyA tail and a ~0.6 kb transcript found only in dividing cells with a short 3’UTR lacking a polyA tail19. The shorter transcript, whose sequence is not annotated, might lack miR-24 recognition sites since the H2AX transcript without the 3’UTR is 505 bases long, leaving only about 100 bp for the 3’UTR. This example of an H2AX transcript containing a shorter 3’UTR expressed only in dividing cells could be an example of a recently described principle of preferential miRNA regulation of longer transcripts expressed in nondividing cells20. By qRT-PCR using primers from the H2AX coding region that measure both transcripts, we found a 4-fold reduction in H2AX mRNA in TPA-treated K562 cells (Suppl. Fig. 1A). Using primers specific for the longer transcript, H2AX mRNA declined by ~2-fold when K562 cells were differentiated using TPA to megakaryocytes or by hemin to erythrocytes and when HL60 cells were differentiated by TPA to macrophages or by DMSO to granulocytes (Fig. 2C, D). H2AX protein, measured after TPA induction, dropped by 14-fold in K562 cells and 4-fold in HL60 cells (Fig. 2E). Relative to the modest decrease in H2AX mRNA, the dramatic decrease in H2AX proteins levels during differentiation, may be attributed to miR-24-mediated translational inhibition of the residual H2AX transcripts. Increased miR-24 and reduced H2AX mRNA were first detected in TPA-differentiated K562 and HL60 cells 12 hr after adding TPA, at which time the cells had stopped dividing (Suppl. Fig. 1B–D). Relatively high miR-24 and low H2AX mRNA and proteins levels in in vitro differentiated cells are comparable to levels in primary human peripheral blood monocytes and granulocytes (Suppl. Fig. 2). The reduction in H2AX mRNA coincident with increased miR-24 in differentiated cell lines and primary blood cells could be due to miR-24 inhibition of H2AX mRNA expression and/or stability.

H2AX transcripts are targeted by miR-24

To verify that H2AX expression is regulated by miR-24, we tested the effect of miR-24 on luciferase expression from control or full length H2AX 3’UTR-containing reporter genes in HepG2 cells. Luciferase activity was reduced more than 2-fold by miR-24 expression (Fig. 2F). miR-24 over-expression in HepG2 cells also decreased H2AX mRNA by 2-fold, while protein expression was reduced even more (~8-fold) (Fig. 2G, H).

H2AX is a predicted miR-24 target by both TargetScan 4.2 and PicTar. Its 3’UTR, which is 1086 nucleotides long, encodes 2 evolutionarily conserved 7-mer exact matches to the miR-24 seed at positions 88–94 and 971–977 and each site has additional pairings to the 3’-region of miR-24 (Fig. 2I). PicTar predicts another conserved miRNA interaction (miR-328) with the H2AX 3’UTR. To identify the miR-24 miRNA recognition elements (MRE) in the H2AX 3’UTR, we inserted each of the predicted miR-24 MRE, as well as the corresponding MRE in which the seed region had been mutated, into the 3’UTR of luciferase reporter genes. Luciferase activity was reduced ~4-fold when either of the wild-type miR-24 MREs was inserted, but was largely restored for vectors containing the mutated MREs (Fig. 2J). Therefore, miR-24 regulates H2AX expression by binding to the 2 sites predicted by TargetScan and Pictar. Although MRE2 would only be found in the longer H2AX transcript, MRE1 could potentially be in both transcripts. The shorter transcript will need to be cloned to determine if this is the case. Overexpressing miR-328 predicted (by PicTar) to target the 3’UTR of H2AX had no effect on luciferase activity or H2AX mRNA or protein levels, further underlining the specificity of the miR-24/H2AX interaction (Suppl. Fig. 3A,B). Collectively, these results strongly suggest that miR-24 binds to the 3’UTR of H2AX mRNA and down-regulates its expression, likely by promoting both mRNA decay and inhibiting translation.

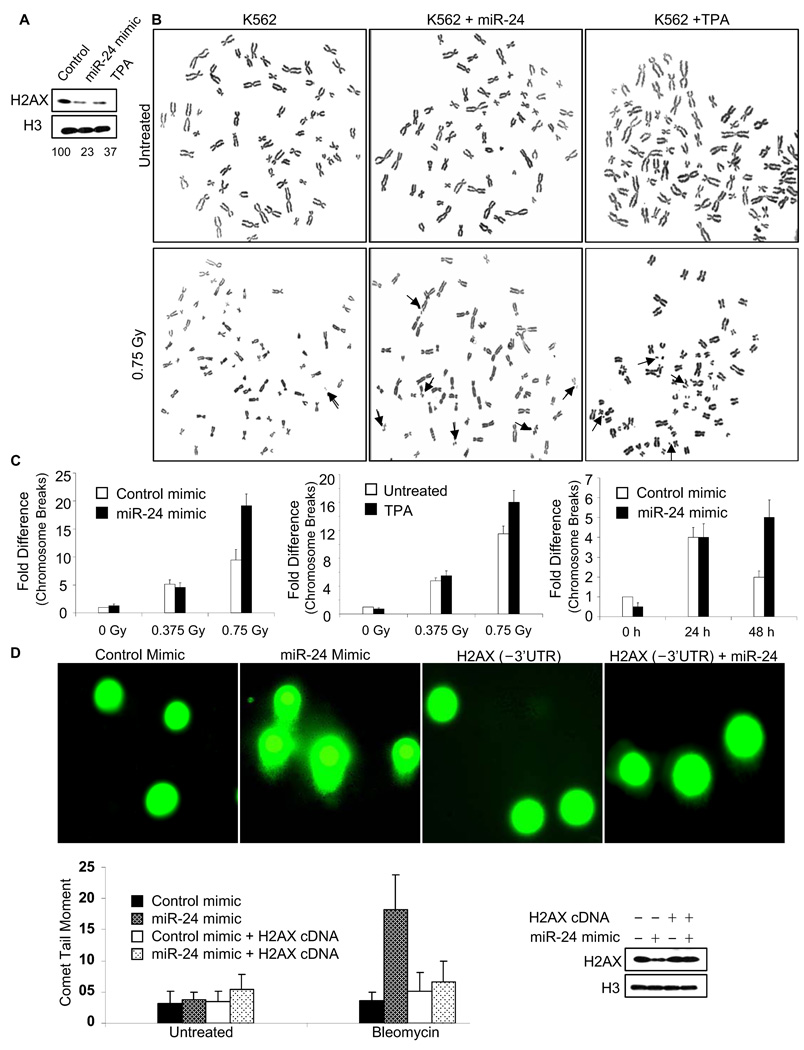

miR-24 reduces genomic stability and DNA repair after DNA damage by regulating H2AX expression

To determine whether miR-24-mediated H2AX down-regulation affects DSB repair, we first evaluated the most serious consequence of unrepaired DSB, chromosomal instability, in K562 cells that were transfected with miR-24 or mock transfected. The transfection conditions were chosen to achieve a level of H2AX knockdown similar to what is observed during TPA differentiation (Fig. 3A). Metaphase spreads were prepared 24 hr after low dose γ-irradiation (Fig. 3B). K562 cells over-expressing miR-24 had twice as many chromosome breaks and fragments as control cells after exposure to 0.75 Gy (p<0.001; Fig. 3C, left). Similarly TPA-differentiated K562 cells were significantly more sensitive to 0.75 Gy radiation than undifferentiated cells (p<0.003; Fig. 3C, middle). Although there were not significantly more breaks 24 hr after exposure to a lower dose of radiation (0.38 Gy), more chromosomal instability was seen at this dose the next day in miR-24 transfected cells (Fig. 3C, right). Undifferentiated and untransfected K562 cells, which have significantly higher endogenous expression of miR-24 and 4-fold less relative H2AX mRNA than HepG2 cells, also show more chromosomal aberrations after irradiation than HepG2 cells (Suppl. Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

miR-24 expression impedes DSB repair and induces chromosomal instability of γ-irradiated K562 cells. (A) Transfection of miR-24 mimic into K562 cells reduces H2AX comparably to TPA differentiation. H2AX was quantified relative to H3 protein by densitometry. (B) Representative images of metaphase chromosome spreads were prepared from treated cells 24 h after γ-irradiation. Arrows mark chromosome breaks or fragments. (C) Chromosome breaks were quantified 24 hr after irradiation of K562 cells that were either undifferentiated or had been differentiated with TPA (middle panel) or transfected with miR-24 (left panel). In the right panel, differences in chromosome breaks that were not present 24 hr following 0.375 Gy were significantly different 48 hr after irradiation in miR-24 vs mock-transfected cells. The mean ± SD number of chromosome breaks and fragments per cell, of 3 independent experiments normalized to control is plotted. (D) Overexpressing miR-24 increases unrepaired DSB by comet assay. K562 cells, transfected with miR-24 mimic and/or miR-24-insensitive H2AX expression plasmid, were treated or not with bleomycin (0.5 µg/ml) for 12 h and analyzed by single cell gel electrophoresis (comet assay) 12 h later. H2AX protein is compared to H3 level in the immunoblot. H2AX levels, reduced by the miR-24 mimic, are rescued by the H2AX expression plasmid. Representative images from bleomycin-treated cells are shown in the upper panel and the mean ± SD comet tail moment of 3 independent experiments for each condition below. Manipulating miR-24 or H2AX levels does not affect baseline DNA damage, but DNA damage after irradiation is significantly increased (p < 0.001) in miR-24 mimic-transfected cells, but only in the absence of H2AX rescue.

As another indicator of unrepaired DNA damage, the persistence of DSB was measured by single cell gel electrophoresis (comet assay) after low dose bleomycin treatment (Fig. 3D). The comet moment quantifies the extent of unrepaired DNA damage. Although the basal comet moment was not significantly changed by miR-24 transfection, the comet tails were 5-fold higher (p<0.001) in miR-24 transfected cells, compared to control miRNA-transfected cells, after bleomycin treatment. To determine whether the effect of miR-24 on DSB repair was mediated via its effect on H2AX, K562 cells were co-transfected with miR-24 and a miR-24-insensitive H2AX expression plasmid without the H2AX 3’UTR. The expression plasmid fully rescued the cells; cells over-expressing miR-24 and H2AX lacking the 3’UTR had no significant increase in comet moment after bleomycin compared to cells transfected with the miRNA control and expression vector. This result strongly suggests that miR-24 regulates DSB repair by controlling H2AX.

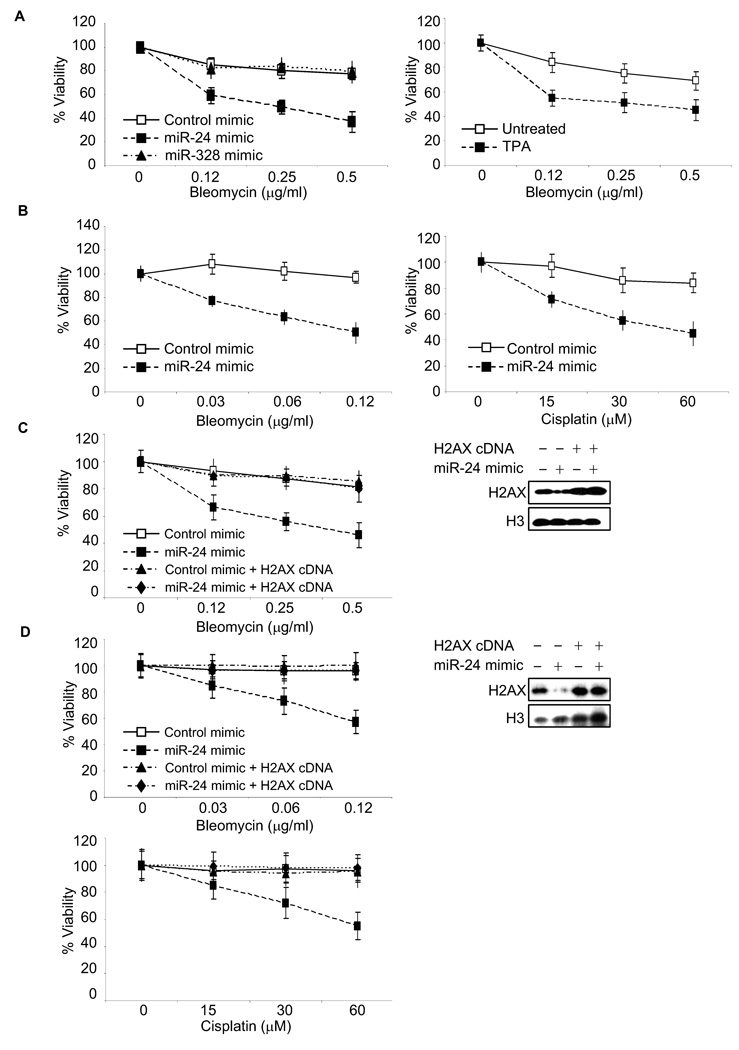

miR-24-mediated down-regulation of H2AX increases cell death after DNA damage

Because of impaired DNA damage repair, H2AX deficiency also leads to increased cell death after exposure to genotoxic drugs. We compared cell viability of K562 cells over-expressing miR-24, miR-328 or mock-transfected after treatment with bleomycin (Fig. 4A, left). Consistent with the chromosomal breakage and comet assay analysis, cells over-expressing miR-24 were significantly hypersensitive to DNA damage, as were TPA-differentiated cells relative to undifferentiated cells (Fig. 4A, right). miR-328 over-expression, which did not alter H2AX mRNA or protein levels (Suppl. Fig. 2), had no effect on bleomycin sensitivity. The effect of miR-24 on DNA damage sensitivity was further confirmed by treating miR-24 mimic-transfected HepG2 cells with bleomycin (Fig. 4B, left) and cisplatin (Fig. 4B, right). miR-24 significantly enhanced cytotoxicity caused by both drugs. The effect of miR-24 on survival was fully rescued by over-expressing miR-24-insensitive H2AX in both K562 (Fig. 4C) and HepG2 (Fig. 4D) cells. By contrast, over-expressing CHEK1, another miR-24 target gene involved in the response to DSBs (predicted by rna22), without its 3’UTR did not rescue K562 cells (Suppl. Fig. 5). Together these results suggest that H2AX is the key miR-24-regulated gene whose down-modulation inhibits the DNA damage response in these terminally differentiated cells.

Fig. 4.

Cells over-expressing miR-24 are hypersensitive to DNA damage by cytotoxic drugs. (A) K562 cells over-expressing miR-24 (left) or treated with TPA (right) are hypersensitive to bleomycin, assessed by viability relative to mock-treated cells 2 d later. TPA treatment or transfection with miR-24 mimic, but not miR-328 mimic, significantly sensitizes K562 cells to DNA damage (p<0.005). (B) Similarly HepG2 cells over-expressing miR-24 are hypersensitive, compared to mock-transfected cells to bleomycin (left) and cisplatin (right). miR-24 over-expression significantly reduces viability to both genotoxic agents (p<0.004). miR-24-mediated hypersensitivity of K562 (C) and HepG2 (D) cells is rescued by expression of miR-24-insensitive H2AX. Cells were mock transfected or transfected with miR-24 mimic or H2AX cDNA lacking the 3’UTR or both. Cell viability was assayed 2 d after exposure to DNA damage and depicted relative to that of undamaged cells. Curves were generated from 3 independent experiments. Immunoblots demonstrate miR-24-mediated decrease in H2AX protein and rescue by transfecting the H2AX cDNA (no 3’UTR).

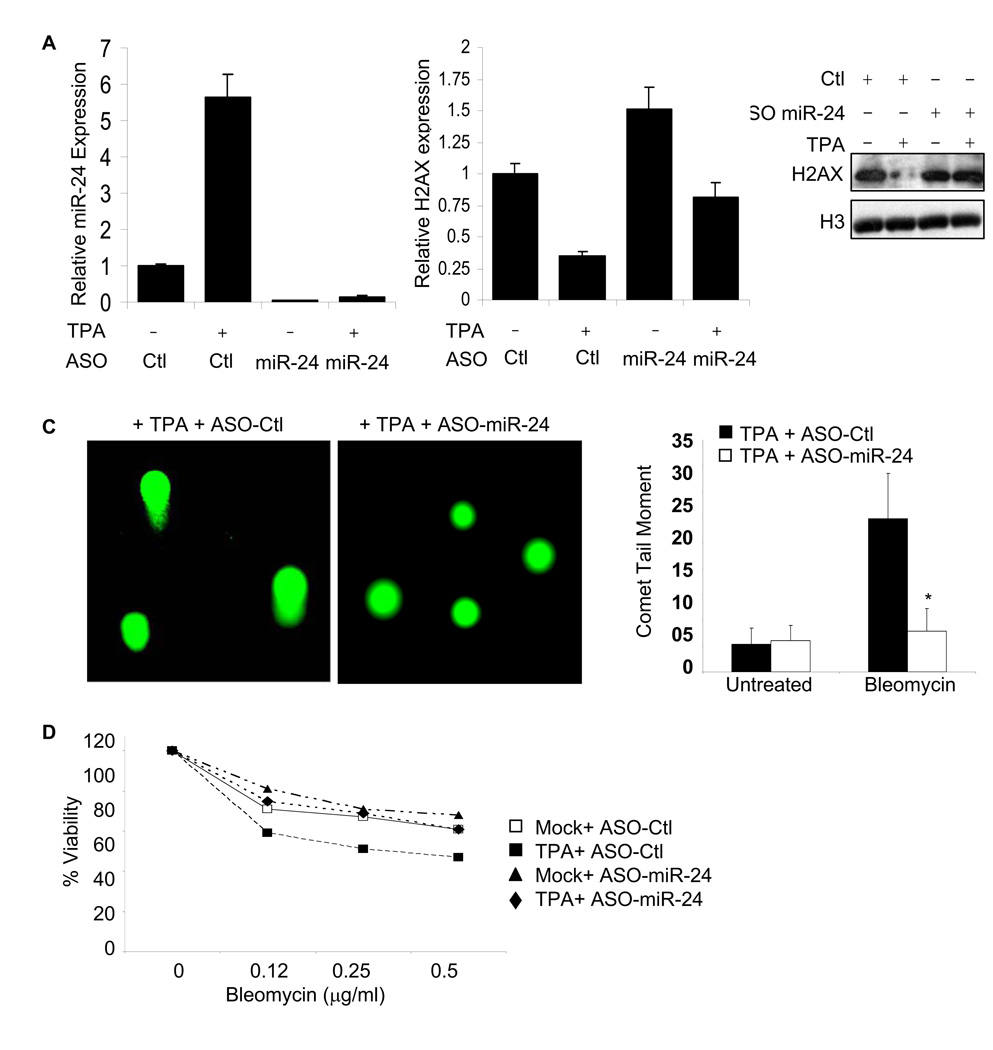

Suppressing miR-24 in differentiated cells boosts DSB repair and diminishes sensitivity to DNA damage

We next tested the effect of inhibiting miR-24 on sensitivity to genotoxic stress. When K562 cells were transfected with miR-24 antisense oligonucleotides (ASO), miR-24 expression was reduced even during TPA differentiation (Fig. 5A). The reduction in miR-24, which correlated with enhanced H2AX mRNA and protein (Fig. 5B), had no effect on undifferentiated K562 cells, but significantly enhanced DNA repair (Fig. 5C) and reduced sensitivity to bleomycin in differentiated cells (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Antagonizing miR-24 enhances cell resistance to bleomycin. (A) miR-24 knockdown in K562 cells, treated or not with TPA, specifically decreases miR-24 levels, assayed by qRT-PCR in cells transfected with miR-24 ASO relative to control ASO (Ctl). miR-24 expression in ASO-treated cells, relative to U6 snRNA, is normalized to that in control ASO-treated cells. (B) miR-24 ASO enhances H2AX transcript (left) and protein levels (right) in K562 cells treated with TPA, but not in untreated, K562 cells. (C) Transfection of miR-24 ASO significantly enhances repair of bleomycin-induced DNA damage, as measured by Comet assay, in TPA-treated K562 cells (*, p<0.001). Representative images from bleomycin-treated cells are shown on the left and the mean ± SD comet tail moments of 3 independent experiments are shown on the right. (D) Relative to untreated cells, TPA treatment sensitizes K562 cells to bleomycin. Transfection of miR-24 ASO significantly blocks bleomycin-induced apoptosis of TPA-treated K562 cells (p<0.003), but does not affect apoptosis of untreated K562 cells. Curves were generated from 3 independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Why is there a mechanism to dampen DSB repair in terminally differentiated cells? One explanation is that most DSBs are generated during DNA replication and this mode of regulation allows differentiated cells to economize and conserve cellular resources under stress-free conditions. Specifically the miRNA-mediated regulation is a rapid and economic strategy to suppress gene expression in differentiated cells. In this case, by up-regulating a single miRNA, miR-24, the terminally differentiated cell ‘switches off’ protein production of a whole set of genes, thereby affecting multiple genes. This could be more efficient than transcriptionally repressing each gene (especially if the locus is open and has recently been transcribed). Another possibility is that suppression of DSB repair in terminally differentiated cells sensitizes these cells to apoptosis. This may be preferred to error prone repair via NHEJ (the primary mode of DSB repair in these cells), which would result in viable, but malfunctioning, cells. Although this solution makes sense for regenerating cells, such as hematopoietic cells and myocytes, it might not be a good solution for long-lived terminally differentiated cells, like neurons, with poor regenerative capacity. It will be worthwhile to determine whether miR-24 is up-regulated during terminal differentiation of all cell types or only in lineages that are continuously renewing. It is noteworthy that at least one miR-24 cluster has been reported to be deleted in some poor prognosis cases of CLL21, a leukemia known to dysregulate key anti-apoptotic genes. Based on our findings here, inappropriate under-expression of miR-24 would be predicted to enhance DNA repair and thereby enhance resistance to cytotoxic cancer therapies.

This study focused on the effect of miR-24 on H2AX and DSB repair. Both H2AX mRNA and protein are reduced by miR-24 expression. miR-24 is likely operating predominantly by inhibiting translation since the effect on protein levels is greater than on mRNA. Mouse genetics has established that 50% decrease in H2AX levels is sufficient to compromise genomic stability and induce tumorigenesis13, 14. However, there are no reports regarding a physiologically equivalent scenario in human cells where inefficient DSB repair occurs due to reduced H2AX protein. This study not only establishes the novel connection between miR-24 and H2AX, but also demonstrates that terminally differentiated cells may represent a physiologically relevant setting in human cells where overexpression of miR-24 decreases H2AX levels resulting in a diminished capacity to repair DSBs. Although current computational methods fail to detect other DSB repair factors targeted by miR-24, other factors in the DSB response might be regulated by miR-24 expression. However, the observation that DSB repair was completely restored by over-expressing H2AX in differentiating cells, or cells over-expressing exogenous miR-24, suggests that the key target of miR-24 in DSB repair is H2AX. Furthermore, we investigated another miR-24 target involved in the cellular DSB response, CHEK1. Over-expressing miR-24-insensitive CHEK1 does not rescue the DNA repair phenotype induced by miR-24 (Suppl. Fig. 5). Future studies should explore whether these and other effects of miR-24 might play a role in sensitivity to DSB and other forms of DNA damage.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Differentiation

HepG2 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS. HL60 and K562 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS. K562 cells (0.5 × 106 cells/ml) were treated with TPA (16 nM, 2 d) or Hemin (100 µM, 4 d) for differentiation into megakaryocytes or erythrocytes, respectively. To induce macrophage or granulocyte differentiation, HL60 cells (0.5 × 106 cells/ml) were treated with TPA (16 nM, 2 d) or DMSO (1.25%, 5 d), respectively. Human polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) were isolated from whole blood after mononuclear cells and platelets were removed by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation. Erythrocytes were lysed by treatment with ice-cold isotonic lysis buffer (0.155 M NH4Cl, pH 7.4). The remaining PMN were washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution and suspended in RPMI medium containing 10% FCS. Human macrophages were isolated from peripheral blood as described (22).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed using random hexamers and superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate samples using the SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems) and the BioRad iCycler. Primers are provided in Supplemental Table 1. Results were normalized to GAPDH. miRNA quantitative PCR was done in triplicate using the TaqMan MicroRNA Assay from Applied Biosystems as per the manufacturer’s instructions and normalized to U6 snRNA.

miRNA microrray

miRNA microarrays were performed as described in 23.

miRNA Mimic and Antisense Oligonucleotide Transfection

HepG2 cells (2.5 × 105/well) were reverse transfected with 30 nM miR-24 or control (cel-miR-67) mimics (Dharmacon) using NeoFx (Ambion) following the manufacturer’s instructions. K562 cells were transfected with miR-24 or control mimics (100 nM) using Amaxa nucleofection following the manufacturer’s protocol. K562 cells were treated with TPA (16 nM, 2 d) and were transfected with 100 nM miR-24 ASO or ASO negative control # 1 (Ambion) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and 36 h later these cells were exposed to indicated concentrations of bleomycin and cell viability was assessed 2 d later.

Luciferase Assay

HepG2 cells (2.5×105/well) were reverse transfected in triplicate with 30 nM miR-24 or miR-328 mimic or control miRNA mimic. Two days later, cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) with psiCHECK2 (Promega) vector (0.5 µg/well) containing the 3’UTR of H2AX cloned in the multiple cloning site of Renilla luciferase or control. After 24 hr luciferase activities were measured using the Dual Luciferase Assay System (Promega) and TopCount NXT microplate reader (Perkin Elmer) per manufacturer’s instructions. Data were normalized to Firefly luciferase. To test whether H2AX mRNA is directly regulated by miR-24, we cloned the 2 predicted MREs in the H2AX 3’UTR into the multiple cloning site of psiCHECK2 and also the mutant versions that disrupted base-pairing between the binding sites and miR-24. HepG2 cells were co-transfected with these plasmids and miR-24 or control mimics for 48 hr using Lipofectamine 2000, before performing luciferase assays as described above.

Immunoblot

K562 cells (1×106) were transfected with miR-24 mimics or control miRNA mimics (cel-miR-67) as above and 48 h later whole cell lysates were prepared using RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0). Protein samples were quantified using Bradford reagent (BioRad) and resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and analyzed by immunoblot probed with antibodies to H2AX (Upstate Biotech), CHEK1 (Cell Signaling), H3 (Cell Signaling), tubulin (Sigma). All antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:1000.

Chromosome Breakage Analysis

K562 and HepG2 cultures were exposed in duplicate wells to indicated doses of γ-irradiation and incubated at 37°C for indicated times in 5% CO2. Cells were harvested and processed for chromosomal analysis following standard methods (24). 50–75 Wright-stained metaphases for each condition were scored for chromosomal aberrations.

Single Cell Gel Electrophoresis (Comet) Assay

Single cell comet assays were performed as per manufacturer’s instructions (Trevigen). Briefly, cells were transfected with siRNAs and 60 h later DSBs induced with CPT (2 µM, 1 h, 37°C). Treated or untreated cells were collected, resuspended in ice cold PBS at 105 cells/ml, mixed with low-melt agarose (1:10 ratio) and spread on frosted glass slides. After the agarose solidified, the slides were successively placed in lysis and alkaline solutions (Trevigen). Slides were then subjected to electrophoresis (1V/cm distance between electrodes) for 10 min in 1×TBE buffer and cells were fixed with 70% ethanol and stained with SYBR Green. Nuclei were visualized using epifluorescent illumination on a Zeiss microscope and images analyzed with the NIH Image program. DNA damage was quantified for 75 cells for each experimental condition by determining the tail moment, a function of both the tail length and intensity of DNA in the tail relative to the total DNA, using the software Comet Score (TriTek). Statistical analysis was by Student’s t-test.

Cell Viability Assay

microRNA-transfected K562 or HepG2 cells were seeded (2×103 cells/100 µl) into octuplicate microtiter wells, incubated overnight, and then treated with indicated reagents or medium for 48 h. Viability was measured by CyQuant Cell Proliferation Assay Kit as per manufacturer’s instructions (Molecular Probes). Results were expressed as OD520 relative to that of untreated cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH AI070302 and a GSK-IDI Alliance grant (JL) and by a Barr Award (DC). We thank members of the Lieberman and Chowdhury laboratory for useful discussions.

References

- 1.Nouspikel T, Hanawalt PC. DNA repair in terminally differentiated cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1:59–75. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(01)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lukas C, et al. DNA damage-activated kinase Chk2 is independent of proliferation or differentiation yet correlates with tissue biology. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4990–4993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puri PL, Sartorelli V. Regulation of muscle regulatory factors by DNA-binding, interacting proteins, and post-transcriptional modifications. J Cell Physiol. 2000;185:155–173. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200011)185:2<155::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belloni L, et al. DNp73alpha protects myogenic cells from apoptosis. Oncogene. 2006;25:3606–3612. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yaneva M, Jhiang S. Expression of the Ku protein during cell proliferation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1090:181–187. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(91)90099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pillai RS, Bhattacharyya SN, Filipowicz W. Repression of protein synthesis by miRNAs: how many mechanisms? Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sevignani C, Calin GA, Siracusa LD, Croce CM. Mammalian microRNAs: a small world for fine-tuning gene expression. Mamm Genome. 2006;17:189–202. doi: 10.1007/s00335-005-0066-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez-Capetillo O, Lee A, Nussenzweig M, Nussenzweig A. H2AX: the histone guardian of the genome. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:959–967. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrini JH, Stracker TH. The cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks: defining the sensors and mediators. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:458–462. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stucki M, Jackson SP. gammaH2AX and MDC1: anchoring the DNA-damage-response machinery to broken chromosomes. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:534–543. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bassing CH, et al. Histone H2AX: a dosage-dependent suppressor of oncogenic translocations and tumors. Cell. 2003;114:359–370. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Celeste A, et al. H2AX haploinsufficiency modifies genomic stability and tumor susceptibility. Cell. 2003;114:371–383. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00567-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tzur G, et al. MicroRNA expression patterns and function in endodermal differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neilson JR, Zheng GX, Burge CB, Sharp PA. Dynamic regulation of miRNA expression in ordered stages of cellular development. Genes Dev. 2007;21:578–589. doi: 10.1101/gad.1522907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun Q, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta-regulated miR-24 promotes skeletal muscle differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2690–2699. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mannironi C, Bonner WM, Hatch CL. H2A.X. a histone isoprotein with a conserved C-terminal sequence, is encoded by a novel mRNA with both DNA replication type and polyA 3' processing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:9113–9126. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.22.9113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandberg R, Neilson JR, Sarma A, Sharp PA, Burge CB. Proliferating cells express mRNAs with shortened 3' untranslated regions and fewer microRNA target sites. Science. 2008;320:1643–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1155390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calin GA, et al. MicroRNA profiling reveals distinct signatures in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemias. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11755–11760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404432101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song E, et al. Sustained small interfering RNA-mediated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 inhibition in primary macrophages. J Virol. 2003;77:7174–7181. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7174-7181.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barad O, et al. MicroRNA expression detected by oligonucleotide microarrays: system establishment and expression profiling in human tissues. Genome Res. 2004;14:2486–2494. doi: 10.1101/gr.2845604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moorhead PS, Nowell PC, Mellman WJ, Battips DM, Hungerford DA. Chromosome preparations of leukocytes cultured from human peripheral blood. Exp Cell Res. 1960;20:613–616. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(60)90138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.