ABSTRACT

We present our experience with sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma at the University of Michigan over 13 years and review prior published data. We conducted a retrospective review of 19 patients who presented to a tertiary care academic center multidisciplinary skull base clinic with sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma between 1995 and 2008. Overall survival was 22% at 5 years, and the estimated 5-year distant metastasis-free survival was 35%. At 2 years, local control was 83%, regional control was 50%, and distant control was 83%. Local control was best in those patients treated nonsurgically, as was median survival, though this was not statistically significant. Nodal disease in the neck, either at presentation or at recurrence, was noted in 26% of patients. Survival for sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma remains poor. It is possible that up-front radiation or chemoradiation will lead to better local control rates, though surgery remains a mainstay of treatment. In all cases, the cervical nodes should be addressed with primary treatment.

Keywords: SNUC, sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma, anterior skull base, subcranial

Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma (SNUC) is a rare tumor of the paranasal sinuses of unknown cause, most often arising in the nasal cavity and presenting at an advanced stage. It was described less than 25 years ago,1 being previously diagnosed as esthesioneuroblastoma or neuroendocrine carcinoma. Because of the rarity of this disease, prior publications on SNUC represent small case series. These have routinely shown aggressive behavior of the tumor with poor prognosis for survival. Multimodality treatment has been recommended by most authors. Our purpose is to present our experience at the University of Michigan over 13 years and to review prior published data.

METHODS

The University of Michigan skull base tumor database includes over 1100 patients with skull base tumors who have been treated or seen in consultation at the University of Michigan. This registry is maintained by the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery at the University of Michigan. Multiple pathologies are represented in the database, including esthesioneuroblastoma, meningioma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, SNUC, and several rarely seen tumor types. Of these, 19 patients with SNUC were identified in the skull base registry from 1995 to October 2008. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, and the medical records were retrospectively reviewed. The Kaplan-Meier technique and life tables (SPSS) were used to statistically analyze the data. The data were censored for statistical analysis, and the raw data, when provided below, are accurate to October 27, 2008.

RESULTS

Demographics and staging information are given in Table 1. Men outnumbered women in our population ~2:1 (13/19 men, 6/19 women). Seventeen patients were Caucasian, one was black, and one was Asian. Staging used clinical and radiographic findings. Sixteen of 19 patients (84%) had T4 disease by American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) criteria. Fourteen were T4b (74% of patients), and two were T4a (10%). The three remaining patients (16%) had T3 disease. Three patients (16%) had nodal disease in the neck at the time of diagnosis, and one patient had metastases to the lung at the time of initial diagnosis. Using the Kadish system for staging, 17 of 19 were stage C and 2 of 19 were stage B.

Table 1.

Demographics, Treatment, Staging, and Survival Raw Data

| Age dx (y) | Sex | Date dx | Op | Marg | Age at Death | AJCC When First Seen at UM | Tob | Chemo | XRT (with dose in Gy if known) | Time to Death after dx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Op, received operative treatment; Marg, margin status; Tob, tobacco use; AWD, alive with disease; ASU, alive, status unknown; ADF, alive, disease-free; AID, alive, intercurrent disease; DWD, dead with disease; DSU, dead, status unknown; dx, diagnosis; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; UM, University of Michigan; XRT, radiation therapy; carbo, carboplatin; MTX, methotrexate; CAV, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine; VP-16, etoposide; 5FU, flourouracil; ipsi, ipsilateral; contra, contralateral. | ||||||||||

| 34 | F | 7/24/1995 | Y | + | 34 | T4bN0M0 | N | VP-16, cisplatin | Y | 5.7 mo (DWD) |

| 51 | M | 12/7/1995 | Y | − | 53 | T4bN0M0 | Y | Carbo, taxol, MTX, CAV, VP-16 | Y | 24.6 mo (DWD) |

| 19 | M | 5/10/1996 | Y | + | 20 | T4aN0M0 | N | Cisplatin, 5FU, VP-16 | Y | 15.1 mo (DWD) |

| 39 | M | 8/21/1997 | Y | − | n/a | T4bN0M0 | N | Cisplatin, carbo, taxol | Y (48.6 initial; 18, 16, 54 to primary site for later adenocarcinoma) | Alive (ADF) |

| 21 | F | 6/17/1999 | N | n/a | 25 | T4bN0M0 | N | Carbo, 5FU, gemcit, taxol, cisplatin | Y | 43.4 mo (DWD) |

| 83 | M | 5/8/2003 | N | n/a | 84 | T4bN1M1 | Y | None | Y | 4.4 mo (DWD) |

| 72 | F | 8/2002 | Y | ? | 75 | rT4bN2M0 | N | Treated outside | Y | 35 mo (DWD) |

| 77 | M | 8/27/2003 | N | n/a | 77 | T4aN0M0 | Y | Carbo, 5FU | Y (70 to primary and ipsi neck) | 2.9 mo (DWD) |

| 61 | M | 12/4/2003 | N | n/a | 64 | T4bN1M0 | Y | Carbo, taxol | Y (70 to primary, 60 to B necks; 20 at failure) | 39.4 mo (DWD) |

| 76 | F | 11/2003 | N | n/a | 78 | T4bNxMx | ? | Treated outside | ? | 23 mo (DSU) |

| 51 | M | 4/8/2004 | N | n/a | n/a | T4bN0M0 | N | Carbo, VP-16 | Y (70 to primary, 64 to ipsi + neck, 60 to contra neck) | Alive (ASU) |

| 67 | F | 11/18/2004 | Y | + | 68 | T4bN0M0 | N | Treated outside | Y | 9.4 mo (DWD) |

| 37 | M | 12/16/2004 | Y | − | 38 | T4bN0M0 | N | Cisplatin | Y (60 to primary and B necks) | 17.8 mo (DWD) |

| 54 | M | 4/6/2006 | N | n/a | n/a | T4bN0M0 | N | Cisplatin, VP-16 | Y (70 to primary) | 24.8 mo (AWD) |

| 71 | M | 8/2006 | N | n/a | n/a | T3N0M0 | Y | Refused treatment | Y | Alive (ADF) |

| 31 | M | 1/11/2007 | N | n/a | n/a | T4bN1M0 | Y | Cisplatin, VP-16 | Y (70 to primary, 60 to B necks) | Alive (AWD) |

| 58 | F | 1/16/2007 | Y | − | n/a | T3N0M0 | N | Cisplatin | Y (60 to primary, 55.4 to B necks) | Alive (ADF) |

| 35 | M | 2/8/2007 | Y | + | n/a | T3N0M0 | N | Carboplatin | Y (60 to primary) | Alive (ADF) |

| 49 | M | 3/26/2007 | Y | + | n/a | T4aN0M0 | N | Cisplatin, VP-16 | Y (60 to primary) | Alive (ADF) |

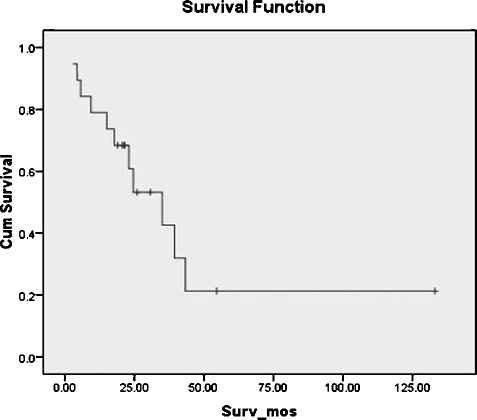

Overall survival in our group was 61% at 2 years, 43% at 3 years, and 22% at 5 years (Fig. 1). Of those living at 2 years, crudely calculated local control was 83%, regional control was 50%, and distant control was 83%. By using Kaplan-Meier product-limit method, the estimated 5-year distant metastasis-free survival was 35%.

Figure 1.

Overall survival.

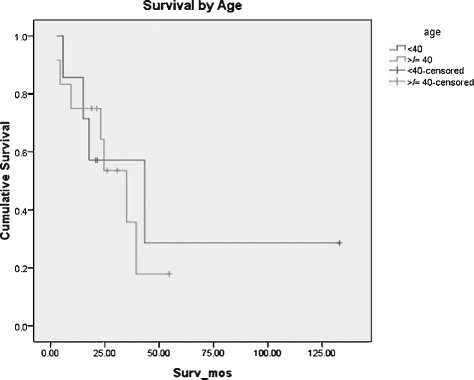

Age at the time of diagnosis ranged from 19 to 83 years. Mean age was 52 years, and median age was 51 years. Incidence increased with increasing age, but there was a seemingly bimodal age distribution with a midlife peak in the fourth decade. The extremes of age fared the worst, but overall survival appeared to be worse for the older age group. Seven of 19 patients (37%) were under the age of 40 years at the time of diagnosis. Using the Kaplan-Meier technique, median survival was 43.3 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.4 to 82.2 months). Three of these seven patients remain alive. For the group diagnosed at 40 years of age or older, median survival was 35 months (95% CI, 20.3 to 49.7 months). Overall estimated median survival was 35 months (95% CI, 17.1 to 52.9 months). Age-related survival curves are shown in Fig. 2. One patient in the group under 40 years of age has survived over 10 years, and therefore median rather the mean survival is most representative of actual cumulative outcomes.

Figure 2.

Survival by age.

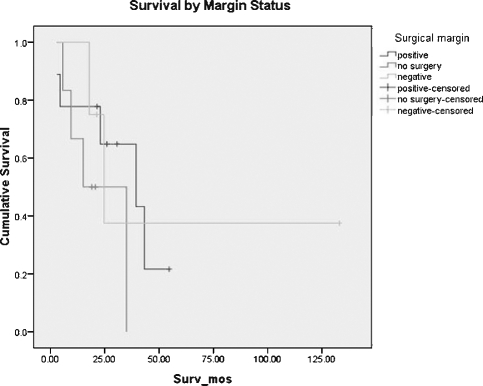

Eleven of 19 tumors (58%) were thought to be resectable at the time of initial diagnosis. We maintained a relatively aggressive posture toward surgical resection. Table 2 shows the criteria for determining tumor resectability. Of these, 9 of 11 patients underwent attempted surgical resection. One additional patient underwent attempted surgical resection at an outside institution prior to referral to the University of Michigan. On reviewing her initial scans, she would have been considered unresectable at the time of diagnosis by our criteria. Of the total 10 patients who underwent surgical resection, five (50%) had known positive surgical margins, one (the patient resected elsewhere) had unknown margin status, and four (40%) had negative margins at the time of initial resection. Survival for these patients is demonstrated in Fig. 3. For patients treated without surgery, median survival was 39.4 months (95% CI, 8.5 to 70.3 months). For patients in whom a negative surgical margin could not be attained, median survival was 15.1 months (95% CI, 0 to 30 months). For those who underwent resection with negative microscopic margins, median survival was 24.6 months (95% CI, 14.4 to 34.8 months). Thus, median survival was best for those who had no surgical resection, but the sample size does not provide adequate power to resolve a potential difference in survival.

Table 2.

Criteria for Unresectability at the University of Michigan

| 1. Obvious brain invasion on imaging |

| 2. Involvement of both optic nerves |

| 3. Involvement of the optic chiasm |

| 4. Invasion of the posterior wall of the sphenoid, including the sella |

| 5. Involvement of Meckel's cave or cavernous sinus |

Figure 3.

Survival by margin status.

Eight of the 19 patients (42%) remain alive. Follow-up time for these patients ranged from 19 months to over 10 years. One of these eight patients were lost to follow-up, but a search of the Social Security Death Index found him to be still living. Of the eight living patients, four underwent attempted surgical resection with postoperative chemotherapy and radiation. Two of these four had negative margins, and they still have no evidence of disease at 133 months and 21.5 months, respectively. The other two had positive margins and have been followed for just over a year. One of the two patients has persistent disease that had minimal radiographic growth in the cavernous sinus at last follow-up. The other has radiographically stable persistent disease.

Recurrence was found in eight patients, five of whom underwent surgical resection (one at an outside institution). There appears to be no preferential pattern for recurrence. Of the eight that recurred, two recurred locally alone, one recurred locally and regionally, one recurred locally and distantly, one recurred regionally alone, one recurred regionally and distantly, and one recurred distantly alone. One patient recurred locally, regionally, and distantly. Times to recurrence after initial diagnosis (local or distant) were 4.2, 4.9, 9.2, 10, 10, 19.8, 30, and 39 months. Mean time to recurrence was 15.9 months. Mean time to death after diagnosis of recurrence was 9.8 months.

Of the four total patients who failed distantly, metastases to the liver were found in one, metastases to the lung were seen in two, and distant bony metastases were seen in two. Three of these four were initially treated nonsurgically with radiation to the primary site and neck and/or chemotherapy. The other was treated with surgical resection followed by concurrent radiation and chemotherapy. Details of their initial treatments prior to distant relapse, as well as time of survival after diagnosis of recurrence, can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Details of Initial Treatment and Time to Death after Diagnosis of Recurrence for Patients with Disease That Failed Distantly

| Patient | Site of Distant Failure | Initial tx | Time to Recurrence (mo) | Time to Death after Rec (no) | Postrecurrence tx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tx, treatment; rec, recurrence; R, right; mediast, mediastinum; reg, regional; XRT, radiation therapy; VP-16, etoposide; CBDCA, carboplatin; 5-FU, flourouracil; CTX, cytoxan; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy. | |||||

| 19 y M T4aN0M0 | Lung, liver | Trans/subcranial resection, XRT, postop cisplatinum and VP-16 | 9.2 | 5.1 | CTX, vincristine, VP-16; CBDCA, VP-16, ifosfamide, mesna |

| 21 y F T4bN0M0 | Sternum, R 5th rib, T5 vertebra, L femur (also local rec) | Carboplatin and 5-flourouracil (at outside facility) | 39 | 4.3 | Concurrent gemcitabine and XRT; cisplatinum, 5-FU, taxol |

| 61 y M T4bN1M0 | Lung, mediast, (also regional rec) | Carboplatin, taxol, IMRT | 30 | 9.4 | XRT, rapamycin, CTX; sunitinib |

| 31 y M T4bN1M0 | C5 vertebra (also local + reg rec) | Cisplatin, VP-16, XRT | 10 | Alive at 5.6 mo, getting chemo | CTX, doxorubicin, vincristine, XRT |

Orbital exenteration was part of the surgical procedure in two patients. Both of these had orbital apex involvement on preoperative imaging studies. Overall, nine patients (47%) presented with orbital involvement. More specifically, four of those nine (44%) had orbital apex involvement. Dural involvement was seen in 10 patients (53%), and intraparenchymal brain involvement was seen in four (21%). The clivus and cavernous sinus were involved in three (16%) and two (11%) patients, respectively.

Two patients had concomitant second primary tumors at the time of initial diagnosis. Interestingly, both of these patients are alive. The first had SNUC with a segment of intestinal-type adenocarcinoma at the olfactory bulb diagnosed at resection. The second had a concomitant floor of mouth squamous cell carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

An initial report from our institution published in 2000 described four patients with SNUC treated with a combined transcranial and subcranial resection, followed by concurrent chemoradiation.2 Outcomes were poor. One patient survived with disease at 27 months, and the other three patients succumbed to their disease within 5 months to just over 2 years. Little has changed in our management since that time, though the advent of intensity-modulated radiation therapy and the effort to tailor chemotherapeutic regimens based on molecular profiles provide promise for improvement.

We are also hopeful that ongoing research will identify tumor markers that better predict prognosis. Another recent study at our institution has evaluated biomarkers in six patients with SNUC.3 NCAM, PCNA, and Bcl-2 showed no clinical relevance. Urokinase plasminogen receptor, a marker for tumor invasion and metastases, was expressed in all cases. This was associated with especially poor prognosis, particularly in patients with positive microscopic margins after resection.

Survival in this study was very low (22% 5-year overall survival). Compared with recent case series, this is the lowest survival rate published (Table 4). Although there is an apparent discrepancy at first glance, survival is not recorded for the same time period, and the patient stages and ability to be surgically resected may differ significantly. Overall survival is variably given for 2, 3, or 5 years. Our population perhaps is most similar to the population at the University of Virginia.4 Their group was comprised of 20 patients, 16 Kadish stage C and four Kadish stage B, in contrast to our group of 17 Kadish stage C and two Kadish stage B. Fifty-five percent of the patients at the University of Virginia were treated surgically, and 53% of our patients underwent surgical resection. Follow-up time was from 4 to 164 months. Their reported 2-year survival was 47%; ours is 61% at 2 years.

Table 4.

Comparison of Outcomes

| Institution | UM | UCLA8 | UCSF5 | UF7 | PMCC9 | UVa4 | UCinci10 | MDACC6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UM, University of Michigan; UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles; UCSF, University of California, San Francisco; UF, University of Florida; PMCC, Peter McCallum Cancer Center (Australia); UVa, University of Virginia; UCinci, University of Cincinatti; MDACC, MD Anderson Cancer Center; chemoXRT, chemotherapy with radiation; Reg, regional; met-free, metastasis-free. | ||||||||

| No. patients | 19 | 8 | 21 | 15 | 10 | 20 | 14 | 16 |

| % treated surgically +/− chemoXRT | 53 | 75 | 90 | 67 | 20 | 55 | 64 | 63 |

| Local control (%) | 83 (2 y) | — | 56 (5 y) | 78 (3 y) | — | — | — | 79 (5 y) |

| Reg control (%) | 50 (2 y) | — | — | 78 (3 y) | — | — | — | 84 (5 y) |

| Distant met-free survival (%) | 35 (5 y) | — | 64 (5 y) | 82 (3 y) | — | — | — | 75 (5 y) |

| Alive, disease-free | 26 (3–133 mo) | 25 (4–37 mo) | — | 40 (12–128 mo) | 50 (8–62 mo) | 20 (4–164 mo) | 36 (3–195 mo) | — |

| Alive with disease (%) | 11 | 50 | — | 7 | 10 | 15 | 0 | — |

| Alive, status unknown (%) | 5 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Dead with disease (%) | 47 | 25 | — | 46 | 40 | 65 | 50 | — |

| Dead, intercurrent disease (%) | 0 | 0 | — | 7 | 0 | 0 | 14 | — |

| Dead, status unknown (%) | 5 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Overall survival | 22% (5 y) | — | 43% (5 y) | 67% (3 y) | 50% (5 y) | 47% (2 y) | 36% (5 y) | 63% (5 y) |

Our results are markedly different from that reported by the University of California, San Francisco study5 largely because on cohort differences. The AJCC staging distribution for their population was 19% T3, 43% T4a, and 38% T4b. We found more patients presenting with T4b disease (74%), thus making resection more difficult or impossible. Ninety percent of the patients at USCF were able to undergo surgical resection, and only 53% of ours were treated surgically. Given these factors, it is not surprising that our 5-year survival is essentially half of the reported UCSF survival. Furthermore, the series from UCSF found that gross total resection predicted local control. We show an 83% local control rate at just 2 years for all patients, but local control for those who underwent surgery as a part of treatment was lower (70% over 2 years). Those with gross total resection actually seemed to have worse local control. At UCSF, 7 of 19 patients who underwent resection had a combined transcranial and transfacial approach. Twelve of 19 (63%) had gross total resection, and surgical margins were microscopically positive in 7 of these 12 (58%). At least 9 of our 10 surgically treated patients had gross total resection (90%). We were unable to assess gross total resection for the patient treated surgically at an outside institution. Of our nine patients who had known gross total resection, five had positive surgical margins (56%). Three of the nine recurred locally, and two of these three had negative microscopic margins. Though we lack power to provide significance for this finding, certainly our local control rate was worse for surgically treated patients at 2 years compared with other studies. In our series, surgical treatment was performed prior to chemoradiation. Perhaps up-front surgical treatment delays the true critical treatment for SNUC (e.g., radiation or chemoradiation). This remains to be proven. It certainly does not support the conclusion that surgery is contraindicated, as we know that our only long-term survivors had resection with negative margins. In addition, overall survival in multiple series is best with complete surgical resection. It does, however, call into question the timing of up-front surgery.

In addition to low survival and questionable local control, we found a high rate of distant failure with a distant metastasis-free survival of only 32% at 5 years. Series from the MD Anderson Cancer Center6 and the University of Florida7 report distant metastasis-free survivals of 75% at 5 years and 82% at 3 years, respectively. The series from MD Anderson was evaluated with a group of esthesioneuroblastomas, and data on staging or clinical details are not given. At the University of Florida, all patients had T4 lesions, with 47% having T4b tumors. Two patients presented initially with neck metastases, and no patient initially had distantly metastatic disease. Much like our population, the patients were treated with a variety of treatments, including surgery alone, radiation alone, or a combination of surgery with chemoradiation. Two patients developed distant metastases. One patient was initially staged as T4bN0 and was treated with preoperative concomitant chemoradiation therapy and craniofacial resection with orbital exenteration. The other was initially staged as T4bN1 and also underwent preoperative concurrent chemoradiation followed by craniofacial resection with orbital exenteration. Although our rate of distant metastases was higher, no statistically significant factor was found to contribute to this end.

The cervical nodal basin must be addressed, even if neck disease is not clinically apparent. Tanzler et al found 2 of 15 patients with neck disease at the time of presentation and an additional two with neck recurrence after treatment.7 Their finding of 27% of patients with nodal disease is consistent with our finding of 26%. Although our treatment algorithm previously recommended elective neck irradiation on a case-by-case basis, we now recommend elective treatment of the neck to every patient with SNUC.

Disease recurrence not surprisingly portends a dismal prognosis. Death within a year of recurrence appears to be standard. One patient treated at the University of Michigan is alive with recurrence. He is receiving palliative chemotherapy, and his functional status is declining. His most recent imaging shows stable appearance of disease.

CONCLUSION

As expected, our results are consistent with findings of previous studies, though we have made several new observations. SNUC routinely has a poor prognosis, even in patients treated aggressively with multiple modalities. Our current approach continues to be complete resection with negative margins if possible, followed by concurrent chemoradiation. We recently have begun testing patients for HER2/neu and epidermal growth factor receptor status to assess for possible response to trastuzumab and cetuximab. This is not yet accepted practice, but we believe that the next step in improving outcomes for SNUC is biologically tailored therapy with complete surgical resection. Additional studies will be required to determine the appropriate order of treatment, though we note that patients treated initially with surgery actually have a poorer local control rate. Also, we are persuaded that treatment of the neck, whether surgically or with radiation, is necessary to improve regional control.

The surgical approach most often employed for these tumors involves a combined frontal craniotomy and transglabellar subcranial technique with additional approaches for craniofacial resection and/or orbital exenteration as needed. This approach allows wide exposure of the anterior skull base while minimizing frontal lobe retraction. There are no facial incisions, and a transzygomatic approach to the infratemporal fossa or a midface degloving for partial maxillectomy can be easily performed in concert with this approach. Even with the advantages of the combined transcranial and subcranial approach, these aggressive tumors tend to be microscopically extensive, making the attainment of negative margins elusive. Despite this, if true negative margins can be attained, hope remains for improved survival with adjunctive chemoradiation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Janet Urban, PA-C for maintenance of the University of Michigan skull base database.

REFERENCES

- Frierson H F, Jr, Mills S E, Fechner R E, Taxy J B, Levine P A. Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma. An aggressive neoplasm derived from schneiderian epithelium and distinct from olfactory neuroblastoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986;10:771–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick J, Ross D, Marentette L, Blaivas M. Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma: case series and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:750–754. discussion 754–755. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200009000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L R, Guffey P, Cordell K G, et al. Determination of tumor markers that can be used as prognostic indicators of sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma, esthesioneuroblastoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skull base. Data not yet published.

- Musy P Y, Reibel J F, Levine P A. Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma: the search for a better outcome. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(8 Pt 1):1450–1455. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200208000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A M, Daly M E, El-Sayed I, et al. Patterns of failure after combined-modality approaches incorporating radiotherapy for sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal D I, Barker J L, Jr, El-Naggar A K, et al. Sinonasal malignancies with neuroendocrine differentiation: patterns of failure according to histologic phenotype. Cancer. 2004;101:2567–2573. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzler E D, Morris C G, Orlando C A, Werning J W, Mendenhall W M. Management of sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma. Head Neck. 2008;30:595–599. doi: 10.1002/hed.20748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B S, Vongtama R, Juillard G. Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma: case series and literature review. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25:162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rischin D, Porceddu S, Peters L, Martin J, Corry J, Weih L. Promising results with chemoradiation in patients with sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma. Head Neck. 2004;26:435–441. doi: 10.1002/hed.10396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto R C, Gleich L L, Biddinger P W, Gluckman J L. Esthesioneuroblastoma and sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma: impact of histological grading and clinical staging on survival and prognosis. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1262–1265. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200008000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]