Abstract

Random integration is one of the more straightforward methods to introduce a transgene into human embryonic stem (ES) cells. However, random integration may result in transgene silencing and altered cell phenotype due to insertional mutagenesis in undefined gene regions. Moreover, reliability of data may be compromised by differences in transgene integration sites when comparing multiple transgenic cell lines. To address these issues, we developed a genetic manipulation strategy based on homologous recombination and Cre recombinase-mediated site-specific integration. First, we performed gene targeting of the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT) locus of the human ES cell line KhES-1. Next, a gene-replacement system was created so that a circular vector specifically integrates into the targeted HPRT locus via Cre recombinase activity. We demonstrate the application of this strategy through the creation of a tetracycline-inducible reporter system at the HPRT locus. We show that reporter gene expression was responsive to doxycycline and that the resulting transgenic human ES cells retain their self-renewal capacity and pluripotency.

INTRODUCTION

The capacity for long-term self-renewal and differentiation into virtually all cells and tissues of the adult body make ES cells powerful tools in regenerative medicine and the creation of disease models. In theory, genetic manipulation of human ES cells (hESCs) can give rise to cell lines that that allow lineage tracking or the expression of disease genes for use in drug screening applications. A number of delivery methods have been used to introduce genetic material into hESCs. These approaches include DNA delivery by electroporation, nucleofection, chemical-based reagents, or viruses (1,2). Once delivered into the cell, genetic material can integrate randomly or in a site-specific manner. It is thought that non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) DNA-repair pathways mediate random integration and site-specific integration, respectively. NHEJ is believed to occur at a higher frequency than HR(3), making it relatively easier to obtain hESCs clones that carry a randomly integrated transgene. However, random integration may take place in heterochromatin, leading to silencing (4) or in coding regions, causing disruption of an endogeneous gene or interference in the transcription of neighboring sequences (5,6). Hence in certain applications, it is of benefit to use HR-based approaches. To date, only a few groups have reported gene targeting in hESCs (7–14) and efficiencies from non-viral based methods have yet to approach those observed in mouse ES cells. This can partly be attributed to the relative sensitivity of hESCs to physical disruption and perhaps, yet to be identified differences between mouse and hESCs.

In this study, we developed an efficient method to introduce transgenes into a defined locus in hESCs. Specifically, we performed gene targeting to introduce a LoxP-docking site, into the HPRT locus in the female hESC line, KhES-1. The resultant clones can then be used in a second round of recombination using the Cre-Lox system to introduce any desired transgene. In the presence of hygromycin, survival is highly skewed towards clones that underwent the correct recombination event. This is because our method requires reconstitution of the hygromycin resistance gene by Cre-mediated recombination between (i) the EF1α promoter-ATG sequence in a plasmid vector carrying the transgene of interest, and (ii) a promoterless hygromycin resistance gene lacking a start codon in the targeted HPRT locus. This method enables integration of any gene of interest into the HPRT locus with high efficiency and low background. Using this approach, we integrated a tetracycline (Tet)-inducible reporter and successfully introduced all components of the Tet-On system (15) into a defined site at the HPRT locus. The hESC clones generated from this process exhibit faithful transgene expression and retain both self-renewal capacity and pluripotency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture of hESCs

The hESC line KhES-1 was maintained in Primate ES medium (ReproCELL, Japan) supplemented with 5 ng/ml recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, WAKO, Japan). Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were mitotically arrested with mitomycin C and used as feeder cells. hESCs were passaged every 3–5 days by partial dissociation with CTK solution composed of 1 mg/ml collagenase, 0.25% trypsin, 20% knockout serum replacement (KSR, Invitrogen) and 1 mM CaCl2 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Homologous recombination

To generate the HPRT-targeting vector, the 5′- and 3′- homologous arms (7.0 and 2.0 kb, respectively) were amplified from KhES-1 genomic DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Primers used to generate the 5′homology arm were as follows: AAAGCGGCCGCGATCCTCCCACCTCAACCTCCCAAGCAG (linked to a NotI site) and AAAGTCGACTGCTCAGGAGGAGGAAGCCGGTGGCGG (linked to a SalI site). The 3′ homology arm was generated using the following primers: TTTCACCGGCGCCCTGGCGTCGTGGTGAGCAGCTCGGCCTG (linked to a SgrAI site) and TTTGGCGCGCCTTGCACTGAGCCGAGATCATGCCACTGTAC (linked to a AscI site). The PCR products were then introduced into the cloning vector, pGEM T-Easy (Promega) and the fragments were subsequently cloned into pBluescriptII SK(−). The DNase I-hypersensitive site 4 (HS4) of the chicken β-globin locus was isolated from pJC5-4 (16) and used as an insulator. The hygromycin resistance gene lacking an initiation codon was PCR amplified from pcDNA/FRT (Invitrogen) and introduced into a cloning vector. The targeting vector was linearized by NotI. For electroporation, two confluent 100-mm dishes of KhES-1 (2–4 × 106 cells) were completely dissociated using 0.05% trypsin and 0.2 mM EDTA. Cells were mixed with 10 µg of linearized-targeting vector, electroporated in GenePulser Xcell (BioRad) using the following settings: square mode, 250 V, 4 ms × 2, 5 s interval, and then dispensed into a 60 mm dish plated with neomycin-resistant feeders. Two days after electroporation, cells were treated with 50 µg/ml G418. The next day, G418 concentration was increased to 100 µg/ml. Selection was performed for 10–14 days post-electroporation.

Karyotype analysis

ESCs were treated with 0.06 µg/ml colcemid (Invitrogen) for 2 h, trypsinized, incubated in 0.075 M KCl for 10 min, and fixed in Carnoy’s fixative. At least 50 spreads were counted for chromosome number and 10 spreads were analyzed for banding patterns at 300–500 band resolution.

Alkaline phosphatase staining and immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS and alkaline phosphatase activity was detected using Vector Blue Alkaline Phosphatase Substrate Kit III (Vector Laboratories). The following primary antibodies were used for immunostaining experiments: anti-Oct4 (Santa Cruz, sc-5279), anti-stage specific embryonic antigen (SSEA)-4 (Chemicon, MAB4304), anti-Tra-1-60 (Chemicon, MAB4360), anti-nestin (Chemicon, MAB5326), anti-pax6 (Chemicon, MAB5552), anti-desmin (Lab Vision, RB-9014) and anti-α-fetoprotein (SIGMA, A-8452). Secondary antibodies were as follows: Alexa488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, A11029), Alexa555-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, A21424) and Alexa488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, A11034).

Gene replacement

The EF1α promoter of the pInsert vector series was generated by PCR using pEF1/Myc-His C (Invitrogen) as template. The insulator in pInsert vector is the tandem core element of the chicken HS4 beta globin insulator (17). The pEF1α-Cre construct was derived from pBS185 (Addgene) with the CMV promoter replaced by the EF1α promoter. TRE and rtTA were obtained from pTRE-Tight (Clontech) and pTet-On (Clontech) respectively by restriction enzyme digestion. Five micrograms of pEF1α-Cre and 20 µg of pInsert-Tif-CAG-EGFP or 50 µg of pInsert-CTOR-EGFP were used for one electroporation. The electroporation settings were the same as for gene-targeting experiments. The ESCs were then plated onto hygromycin-resistant MEFs (Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Japan). Hygromycin selection (40 µg/ml, Invitrogen) was started 2 days after electroporation.

Genotyping

PCR was performed using KOD FX (TOYOBO) following manufacturer’s recommendations. Primers used for genotyping are as follows: P1: 5′-GACCGTAGAATTGGAGATCTCCATGAATCTGAAGC-3′, P2: 5′-AATCGGGAGCGGCGATACCGTAAAGCACGAGGAAG-3′, P3: 5′-ATGGCGATGCCTGCTTGCCGAATATCATGGTGG-3′, P4: 5′-TAATCTTGGGCAAGTTACTTAACCTCTCTGATTTG-3′, P5: 5′-TGCGACGAGCCCTCAGGCGAACCTCTCGGCTTTCC-3′, P6: 5′-AGGATCTTACCGCTGTTGAGATCCAGTTCG-3′, P7: 5′-ATTGGCTCCGGTGCCCGTCAGTGGGCAG-3′, P8: 5′-AGAAACTTCTCGACAGACGTCGCGGTGAGTTCAGG-3′, and P9 5′-AAAATCGATTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCC-3′. The expected sizes of PCR fragments are as follows: P1 × P2: 10.0 kb, P3 × P4: 5.8 kb, P5 × P6: 2.5 kb, P5 × P9: 2.6 kb, P7 × P8: 1.3 kb. Southern blotting was outsourced to PhoenixBio (Japan). The probe used to identify the correct HR event was generated by PCR amplification using KhES-1 genome as template. Primer sequences are as follows: 5′-AATGTGTCTGATACAACCCATGCTGCTTGTAAC-3′ and 5′-AGGGAGTAAAATGACATGGCCTAGTTACTATC-3′. EGFP cDNA was used as a probe to assess gene replacement.

Induction of gene expression

Induction of gene expression was carried out by addition of doxycycline (Dox) (Invitrogen) to a concentration of 2 µg/ml for 2 or 3 days. In the assays for Dox dose-dependence, cells were treated with 2 µg/ml, 500, or 100 ng/ml of Dox for 3 days.

Flow cytometry

ESCs were dissociated by 0.25% trypsin-1 mM EDTA and then analyzed by FACS Aria (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tomy Digital Biology, Japan).

In vitro differentiation

For embryoid body (EB) formation, hESC colonies were detached with CTK solution, collected by sedimentation, and seeded onto a Petri dish (BD Biosciences, 351029). EBs were cultured in Primate ES medium (ReproCELL, Japan) for 7 days and then plated onto gelatin-coated dishes. Adherent cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Sigma) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, JRH Biosciences) for an additional 7 days. Dox was added three days to the end of cell culture. Cells were then harvested and analyzed by FACS. For immunostaining with anti-nestin, 4-day-old EBs were plated onto a poly-l-lysine/laminin-coated dish and cultured in N2B27 neural induction medium for 12 days. For immunostaining with anti-pax6, ESCs were plated onto a poly-l-lysine/laminin-coated dish and cultured in N2B27 neural induction medium supplemented with 100 ng/ml mouse recombinant noggin (R&D) and 1 µM SB431542 (Sigma) for 10 days. For immunostaining with anti-desmin, 14-day old EBs were plated onto a gelatin-coated dish and cultured in DMEM/F12 (Sigma) containing 10% FBS for 8 days. For immunostaining with anti-α-fetoprotein (AFP), ESCs were plated onto M15 feeder cells and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% KSR, 100 µM non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen), 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen), 50 units/ml penicillin and 50 µg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 100 µM β-mercaptoethanol for 14 days (18). Supplementation with activin A (10 ng/ml, R&D) was performed from Day 1 to 12. Neural differentiation of hESCs was carried out as described (19) with some modifications. Briefly, undifferentiated hESCs were cultured in N2B27 neural induction medium supplemented with both 100 ng/ml mouse recombinant noggin (R&D) and 1 µM SB431542 (Sigma), an inhibitor of TGFβ signaling. After 10 days, cell colonies were dissociated into smaller clumps and cultured in N2B27 medium with noggin alone for the following 10 days. Neural progenitors were plated on poly-l-lysine, laminin and fibronectin-coated dishes, and cultured in N2B27 supplemented with 10 ng/ml brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF, R&D), 10 ng/ml neurotrophinneurotrophin-3 (NT-3, R&D) and 100 ng/ml nerve growth factor (NGF, R&D) for 16 days.

Teratoma formation

ES cells carrying pInsert-CTOR-EGFP were injected into a testis of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice (CLEA Japan). Teratomas were recovered 2 months after injection. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Board on Animal Care. Tumors were fixed in Bouin’s fixative, embedded in paraffin, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

RESULTS

HR in hESCs

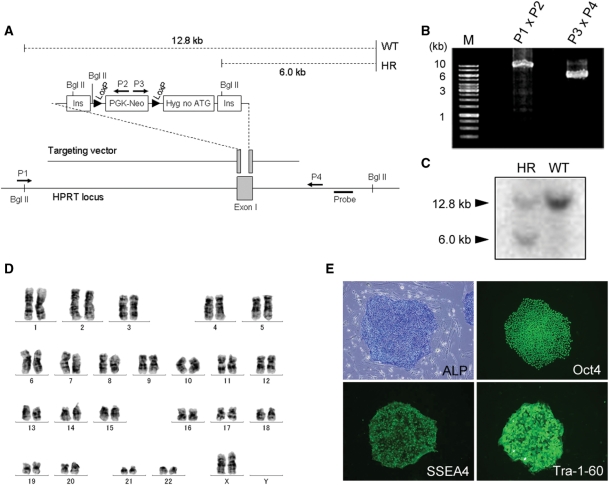

We first carried out HR in the HPRT locus of the hESC line KhES-1. The targeting vector contained a loxP site flanked by a neomycin expression cassette (Figure 1A). Another loxP site was located 5′ to a promoterless hygromycin resistance gene lacking the ATG codon, with the whole construct flanked by two HS4 insulators (17). The targeting vector was delivered to KhES-1 cells by electroporation. Out of 424 neomycin-resistant clones screened, six (1.4%) underwent the desired HR event as confirmed by PCR genotyping (Figure 1B) and Southern blotting (Figure 1C). One targeted clone was randomly selected and used for subsequent gene replacement. This clone had a normal karyotype (Figure 1D). Moreover, it exhibited alkaline phosphatase activity (Figure 1E) and expressed Oct4, SSEA4 and Tra-1-60, indicating maintenance of an undifferentiated state (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

HPRT gene-targeting experiments in KhES-1 cells. (A) Scheme for HR. Ins: insulator, Hyg no ATG: hygromycin resistant gene lacking ATG initiation codon. Arrows (P1–P4) indicate primers used for PCR genotyping. For Southern blotting experiment, the dashed lines show the expected DNA fragment size for the WT (12.8 kb) and the recombined locus (6.0 kb) after Bgl II digestion. (B) Genotyping analysis to identify the desired HR event by PCR. 5′-products are 10.0 kb and 3′-products are 5.8 kb. (C) Genotyping analysis to identify the desired HR event by Southern blotting. (D) G-band karyotype of a KhES-1 clone that carried the targeted HPRT locus. (E) Expression of hESC markers in one of the targeted clones. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity is seen as a blue signal. Immunostaining showed expression of Oct 4, SSEA 4 and Tra-1-60.

Gene replacement for HPRT locus

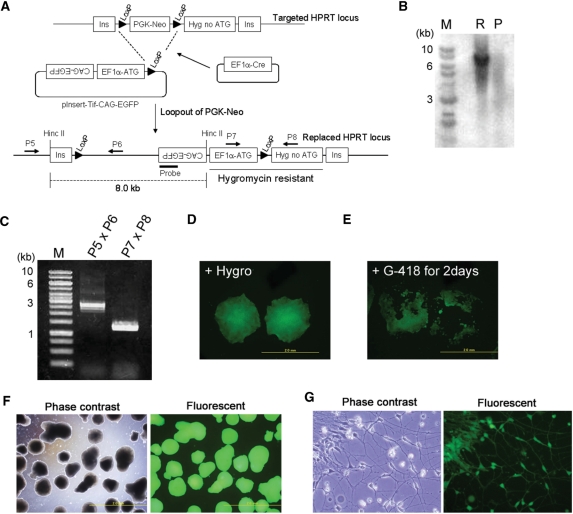

To perform gene replacement, we constructed a vector containing the EF1α promoter, a Kozak sequence, an ATG codon and a LoxP site in this order (Figure 2A). We called this vector pInsert. Co-electroporation of pInsert with a plasmid expressing Cre recombinase and subsequent hygromycin treatment should result in selective survival of cells that carried the pInsert vector at a specific site in the targeted HPRT locus. Gene replacement was performed using a pInsert vector carrying an EGFP transgene under the control of the CAG promoter (pInsert-Tif-CAG-EGFP) (Figure 2A). One hundred percent of the 186 hygromycin-resistant colonies we screened were EGFP-positive (Figure 2D). Eighty colonies were randomly chosen from the initial 186 and were all shown to be neomycin sensitive, indicating excision of the neomycin cassette (Figure 2E). One clone was randomly selected from this subset and used for succeeding experiments. Southern blotting (Figure 2B) and PCR (Figure 2C) confirmed the correct integration of pInsert-Tif-CAG-EGFP. This clone exhibited stable EGFP expression for at least 2 months (data not shown), can form EGFP-positive embryoid bodies (EBs) (Figure 2F) and can differentiate into neurons (Figure 2G). All eight clones that were randomly selected from the hygromycin-resistant clones expressed similar levels of EGFP and were confirmed to have undergone gene replacement (Supplementary Figure S1). We also performed gene replacement using another targeted clone and obtained similar results (Supplementary Figure S2A).

Figure 2.

Gene-replacement strategy. (A) Scheme for gene replacement. Cre recombinase-mediated integration regenerates a functional hygromycin resistance gene while also resulting in loss of neomycin resistance. The dashed line indicates the expected fragment size after HincII digestion in the Southern blotting. Arrows (P5–P8) are PCR primers used below. (B) Southern blotting results for one hygromycin-resistant clone using an EGFP probe. M: Size marker, R: Clone that underwent gene replacement, P: Parental clone. (C) PCR genotyping of the hygromycin-resistant clone. (D) EGFP expression of the hygromycin-resistant clones. (E) Neomycin sensitivity of hygromycin-resistant and EGFP-expressing clones. (F) EB formation of the hygromycin-resistant clones. (G) Neural differentiation of a hygromycin-resistant clone.

Inducible gene expression based on gene-replacement system

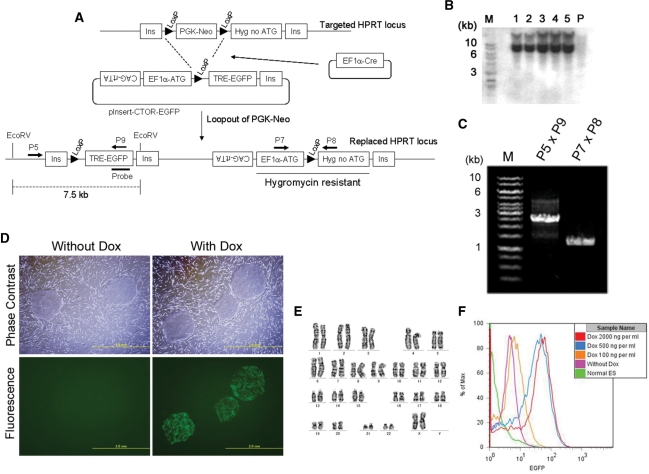

We next attempted to introduce all components of the Tet-inducible gene expression system into the transgene-docking site at the HPRT locus. Gene replacement was performed by co-transfection of a pInsert vector carrying CAG-rtTA and TREtight-EGFP (pInsert-CTOR-EGFP), with a Cre recombinase expression plasmid (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Tet-On system on the HPRT locus. (A) Scheme for generating Tet-On system on a single HPRT locus using a gene-replacement technology. pInsert-CTOR-EGFP vector contains CAG-rtTA and TRE-EGFP cassettes. After gene replacement, TRE-EGFP integrates between two insulators. The dashed line indicates the expected band size after EcoRV digestion in the Southern blotting. Arrows (P5 and P7 to P9) are primers used in PCR genotyping. (B) Southern blotting using an EGFP probe. M: Size marker, 1–5: Replaced clones, P: Parental clone. (C) Representative results from PCR genotyping of surviving clones at post-selection. (D) EGFP expression of hygromycin-resistant clone #1 in the absence or presence of Dox (2 µg/ml for 2 days). (E) Flow cytometric analysis of EGFP expression indicates dose-dependent response to doxycycline. Cells were treated with 100, 500 or 2000 ng/ml Dox for 3 days. (F) Karyotype analysis of representative clone that underwent the desired integration.

Treatment with Dox for 2 days post-transfection resulted in EGFP expression (Figure 3D and Supplementary Figure S2B). Five hygromycin-resistant clones were randomly selected and further analyzed by Southern blotting and were confirmed to have undergone the correct integration event (Figure 3B). All five clones were responsive to doxycycline induction and clone #1 was further characterized. PCR analysis confirmed the integration of pInsert-CTOR-EGFP into the HPRT locus (Figure 3C) while G-banding revealed a normal karyotype (Figure 3E). Moreover, this clone and another clone that was selected randomly exhibited dose-dependent induction of EGFP expression by doxycycline, as determined by FACS analysis (Figure 3F and Supplementary Figure S3). Although we used a second generation Tet system (TRE-tight from Clontech), faint EGFP signals were still detected in the absence of Dox, indicating leakiness even in this improved Tet system. Nevertheless, treatment with 2 µg/ml of Dox increased the fluorescence intensity by 15-fold compared with the untreated control (Figure 3F and Supplementary Figure S3).

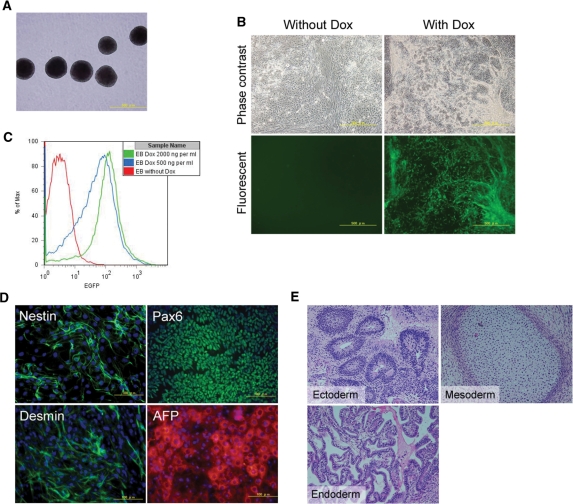

When grown in suspension cultures, these genetically modified hESCs formed EBs (Figure 4A), that were then made to adhere to gelatin-coated plates. Treatment with Dox resulted in induction of EGFP expression (Figure 4B) in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4C). Moreover, these ESCs retained the ability to differentiate into representatives of the three germ layers as shown by positive immunostaining results for Nestin and Pax6 (ectoderm), Desmin (mesoderm) and AFP (endoderm) (Figure 4D) and can form teratomas (Figure 4E). Taken together, these results indicate that these ESCs maintain pluripotency after a second round of genetic modification and clonal selection and upon differentiation, remain responsive to Dox.

Figure 4.

In vitro differentiation of a clone carrying pInsert-CTOR-EGFP. (A) Thirteen-day-old EBs (phase contrast). (B) EGFP expression of replated EBs in the absence or presence of Dox (2 µg/ml for 3 days). (C) Attached EBs were treated with Dox (500 or 2000 ng/ml) or without Dox for 3 days. Cells were then harvested and analyzed by FACS. These cells retained Dox dose-dependency in their differentiation stage. (D) Cells were differentiated into representatives of the three germ layers and immunostained with anti-nestin (ectoderm), anti-pax6 (ectoderm), anti-desmin (mesoderm) and anti-α-fetoprotein (AFP, endoderm). Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). (E) Histological analysis of teratomas formed in SCID mice.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we established a gene-replacement system using Cre/LoxP recombination to insert any desired cassette into the HPRT locus. This gene-replacement strategy provides a number of advantages. First, our method eliminates the possibility of obtaining clones that underwent random integration of the transgene while favoring the survival of clones carrying a correctly integrated transgene. This is because hygromycin resistance can be rescued only if the vector carrying the transgene integrates into the targeted HPRT locus. Moreover, the efficiency of Cre-mediated recombination, calculated as the percentage of clones carrying the correct insertion event over the total number of surviving clones, is about 70 times higher than that of HR-based gene targeting in the original KhES-1 line (100% versus 1.4%, respectively). This significantly minimizes the number of colonies to be picked and analyzed for the desired integration. Furthermore, gene targeting is performed only once for a particular cell line to create a docking site at the HPRT locus. Once this genetically modified parental cell line is generated, the desired secondary recombination event is mediated by the relatively more efficient Cre recombination system. This also eliminates the need for long homologous sequences in the expression cassette, hence simplifying the creation of transgenic hESCs. We have also shown that ESCs subjected to two stages of genetic modification and clonal selection maintain their pluripotency and normal karyotype. Another advantage of our method is that site-specific integration at a defined and well-characterized locus provides a uniform chromatin background when comparing transcriptional activity of various promoters or the function of mutant and normal variants of a transgene. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that introduction of lineage reporters into the HPRT locus may not be the ideal approach when studying genes that require complex interactions of cis- and trans- regulatory elements. In this case, placing the transgene under the control the endogenous promoter may provide a more accurate simulation of gene expression during development.

We have demonstrated faithful expression of an EGFP gene under the control of the constitutive EF1α promoter, in both undifferentiated (Figure 2D) and differentiated (Figure 2G) states. However, for yet to be determined reasons, ESCs that carried the EGFP gene under the control of the Tet system exhibited clone to clone variability in their response to doxycycline induction (Supplementary Table S1 and Figure S4). Although the percentage of clones that exhibited satisfactory induction is high enough to allow screening for a manageable number of clones, improvements to this inducible system can further minimize time required to complete the screening. We have also shown that initial targeting of the HPRT locus and a second recombination event that introduces additional transgenes cause no adverse effects on self-renewal and pluripotency of ESCs. Nevertheless, we could not discount the possibility that culture conditions and selection provide a restrictive environment that ultimately favors the survival of clones that are able to self-renew and retain ES cell characteristics.

It should be noted that the HPRT locus is subject to X chromosome inactivation. In the case of the XX hESC line, KhES-1, hygromycin selection favors survival of clones with an active X chromosome that carries the disrupted HPRT locus. Hence it is possible for these ESCs and their derivatives to have a Lesch–Nyhan phenotype. Particularly in drug screening and disease model applications, it should be considered whether such phenotype is of relevance to the cell lineage of interest and the type of assay to be performed. Moreover, not all pInsert-CTOR-EGFP integrated cells expressed EGFP in response to the induction of Dox when they were differentiated in hygromycin-free condition (Supplementary Figure S5). It suggests that the manipulated X chromosome was inactivated and that hygromycin selection is indispensable for the continuous activation of integrated genes.

In summary, we have performed gene targeting in hESCs to introduce a transgene-docking site into the HPRT locus and have demonstrated high efficiency Cre-mediated integration of any given construct into this docking site. These genetically modified hESC clones faithfully express the integrated transgenes and maintain their self-renewal capacity and pluripotency.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) of Japan. Funding for open access charge: New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) of Japan.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Ms Mari Hamao and Ms Kaori Yamauchi for technical assistance. They also thank other members of the Stem Cell and Drug Discovery Institute for fruitful discussions and valuable suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Giudice A, Trounson A. Genetic modification of human embryonic stem cells for derivation of target cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:422–433. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braam SR, Denning C, van den Brink S, Kats P, Hochstenbach R, Passier R, Mummery CL. Improved genetic manipulation of human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Meth. 2008;5:389–392. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iiizumi S, Kurosawa A, So S, Ishii Y, Chikaraishi Y, Ishii A, Koyama H, Adachi N. Impact of non-homologous end-joining deficiency on random and targeted DNA integration: implications for gene targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:6333–6342. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis J. Silencing and variegation of gammaretrovirus and lentivirus vectors. Human gene therapy. 2005;16:1241–1246. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nienhuis AW, Dunbar CE, Sorrentino BP. Genotoxicity of retroviral integration in hematopoietic cells. Mol. Ther. 2006;13:1031–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, McCormack MP, Wulffraat N, Leboulch P, Lim A, Osborne CS, Pawliuk R, Morillon E, et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science. 2003;302:415–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1088547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zwaka TP, Thomson JA. Homologous recombination in human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotech. 2003;21:319–321. doi: 10.1038/nbt788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urbach A, Schuldiner M, Benvenisty N. Modeling for Lesch-Nyhan disease by gene targeting in human embryonic stem cells. Stem cells. 2004;22:635–641. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-4-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki K, Mitsui K, Aizawa E, Hasegawa K, Kawase E, Yamagishi T, Shimizu Y, Suemori H, Nakatsuji N, Mitani K. Highly efficient transient gene expression and gene targeting in primate embryonic stem cells with helper-dependent adenoviral vectors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:13781–13786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806976105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Domenico AI, Christodoulou I, Pells SC, McWhir J, Thomson AJ. Sequential genetic modification of the hprt locus in human ESCs combining gene targeting and recombinase-mediated cassette exchange. Cloning Stem Cells. 2008;10:217–230. doi: 10.1089/clo.2008.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irion S, Luche H, Gadue P, Fehling HJ, Kennedy M, Keller G. Identification and targeting of the ROSA26 locus in human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:1477–1482. doi: 10.1038/nbt1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis RP, Ng ES, Costa M, Mossman AK, Sourris K, Elefanty AG, Stanley EG. Targeting a GFP reporter gene to the MIXL1 locus of human embryonic stem cells identifies human primitive streak-like cells and enables isolation of primitive hematopoietic precursors. Blood. 2008;111:1876–1884. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruby KM, Zheng B. Gene targeting in a HUES line of human embryonic stem cells via electroporation. Stem cells. 2009;27:1496–1506. doi: 10.1002/stem.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou J, Maeder ML, Mali P, Pruett-Miller SM, Thibodeau-Beganny S, Chou BK, Chen G, Ye Z, Park IH, Daley GQ, et al. Gene targeting of a disease-related gene in human induced pluripotent stem and embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gossen M, Freundlieb S, Bender G, Muller G, Hillen W, Bujard H. Transcriptional activation by tetracyclines in mammalian cells. Science. 1995;268:1766–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.7792603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung JH, Whiteley M, Felsenfeld G. A 5' element of the chicken beta-globin domain serves as an insulator in human erythroid cells and protects against position effect in Drosophila. Cell. 1993;74:505–514. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80052-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otsuki A, Tahimic CG, Tomimatsu N, Katoh M, Chen DJ, Kurimasa A, Oshimura M. Construction of a novel expression system on a human artificial chromosome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;329:1018–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiraki N, Umeda K, Sakashita N, Takeya M, Kume K, Kume S. Differentiation of mouse and human embryonic stem cells into hepatic lineages. Genes Cells. 2008;13:731–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerrard L, Rodgers L, Cui W. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to neural lineages in adherent culture by blocking bone morphogenetic protein signaling. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1234–1241. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.