Abstract

The 90 kDa heat shock protein (Hsp90) has become a validated target for the development of anti-cancer agents. Several Hsp90 inhibitors are currently under clinical trial investigation for the treatment of cancer. All of these agents inhibit Hsp90’s protein folding activity by binding to the N-terminal ATP binding site of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone. Administration of these investigational drugs elicits induction of the heat shock response, or the overexpression of several Hsps, which exhibit antiapoptotic and pro-survival effects that may complicate the application of these inhibitors. To circumvent this issue, alternate mechanisms for Hsp90 inhibition that do not elicit the heat shock response have been identified and pursued. After providing background on the structure, function, and mechanism of the Hsp90 protein folding machinery, this review describes several mechanisms of Hsp90 modulation via small molecules that do not induce the heat shock response.

Keywords: Hsp90, heat shock response, cancer, novobiocin, gedunin, celastrol, gamendazole

INTRODUCTION

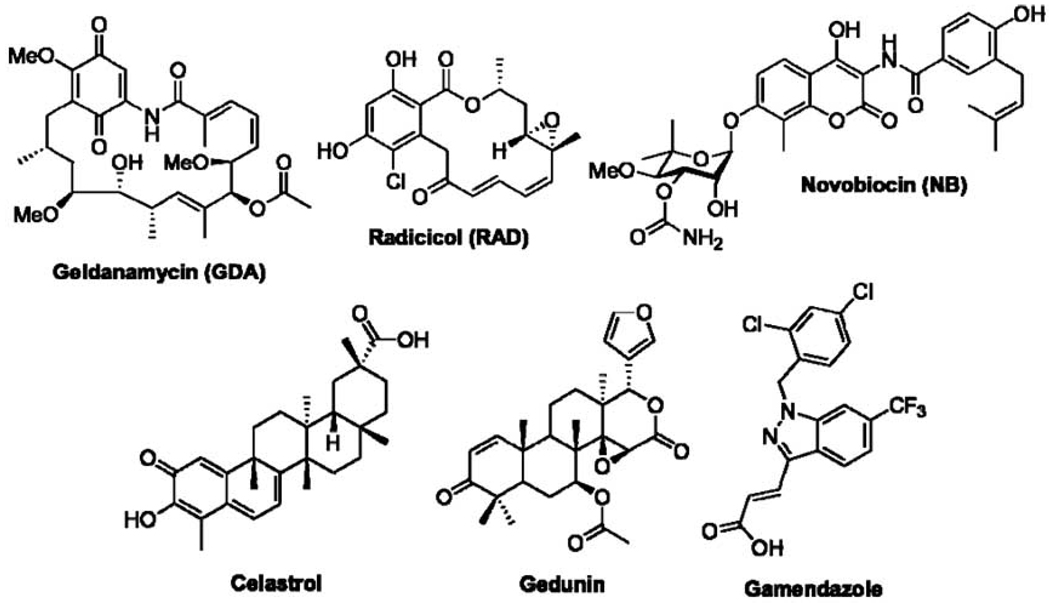

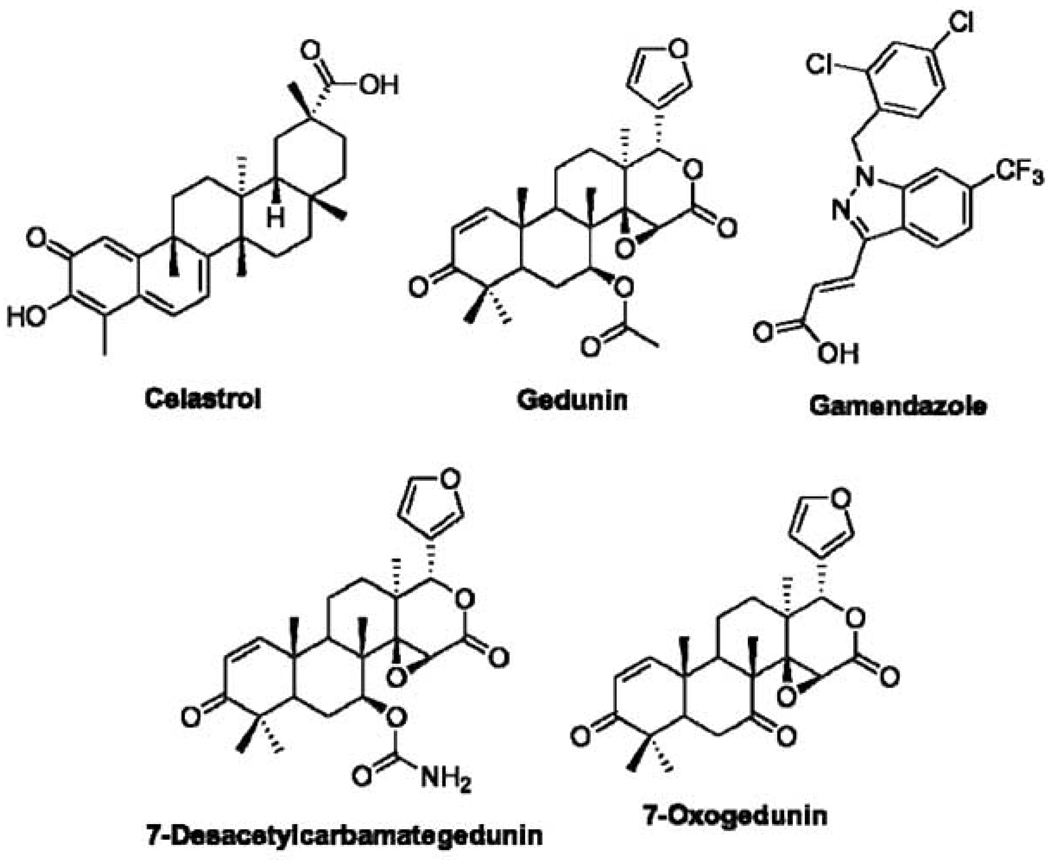

Protein dysfunction occurs frequently within cells, however, the accumulation of dysfunctional proteins can be a hallmark of various pathological states [1–6]. As a means to promote both cell survival and the maintenance of genetic information, living cells have evolved mechanisms capable of maturing, denaturing, or degrading misfolded proteins [7–9]. Molecular chaperones comprise a class of bio-machinery that provides quality control over protein structure [10–13]. One of the most studied molecular chaperones is the 90 kDa heat shock protein, Hsp90 [14–20]. Significant investigation of Hsp90 has been pursued due to its therapeutic potential as a target for the development of cancer chemotherapeutics [21–25]. Toward this objective, several natural product and synthetic entities, including geldanamycin (GDA), radicicol (RAD), novobiocin (NB), celastrol, gedunin, and gamendazole (Fig. 1) have been identified as Hsp90 modulators that function by different mechanisms [26–28]. Thus far, inhibitors have been discovered that bind Hsp90’s N-terminal ATP binding pocket [29–38], C-terminal nucleotide-binding domain [39–42], or disrupt co-chaperone interactions [43–46]. These mechanisms of modulation provide various opportunities for the development of Hsp90 inhibitors with clinical applications toward multiple disease states.

Fig. 1.

Representative examples of natural product and synthetic inhibitors of the Hsp90 protein folding machinery.

Currently, the primary focus of Hsp90 modulation is based on competitive displacement of ATP from the N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain, which is not only sought after in the laboratory, but also in clinical trials for cancer [47–50]. Efficacious and tolerable drugs have been developed and the target validated [51], however, limitations resulting from this approach include induction of the heat shock response, which is pro-survival and thus undesired in cancer treatment [52, 53]. Additional therapeutic avenues are being explored with Hsp90 as the molecular target, which include pathogenic infection [54–56], cystic fibrosis [57] and male contraception [28] wherein this pro-survival response is also detrimental to disease treatment. An ideal drug candidate for these therapeutic areas would include a selective Hsp90 inhibitor that induces no heat shock response. In this review, Hsp90 function, structure, and mechanism will be outlined along with a summary of alternate methods for Hsp90 modulation and the potential impact such compounds may illicit on various diseases ranging from cancer to cystic fibrosis.

HSP90 FUNCTION, STRUCTURE, AND PROTEIN FOLDING MECHANISM

Hsp90 is a molecular chaperone dependent on its inherent ATPase activity for chaperone function [58]. As a member of the GHKL family of ATPases, (Gyrase, Hsp90, Histidine Kinase, and MutL Kinase) Hsp90 exhibits a unique N-terminal nucleotide-binding pocket [59]. Hsp90 is responsible for the refolding of denatured proteins as well as the three-dimensional maturation and transport of more than 200 client proteins, i.e. proteins that require Hsp90 in either limited or extensive capacity for proper function (a complete listing of Hsp90 clients can be found at http://www.picard.ch/downloads/Hsp90interactors.pdf) [60]. The protein folding process includes the involvement of several partners (co-chaperones and/or partner proteins) through the assembly of protein-protein interactions that, when assembled, comprise the Hsp90 protein folding machinery (Table 1) [10, 16, 56, 61]. Through a series of conformational switching events, this heteroprotein complex conducts both protein folding and conformational maturation by the energy garnered through ATP hydrolysis [62–65].

Table 1.

Examples of Hsp90 Co-Chaperones and Partner Proteins, Interactive Domain, and Function

| Co-Chaperone/Partner Protein | Interactive Domain | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Hsp70 | C-terminus via HOP | Facilitates protein client loading |

| HOP | C-terminal MEEVD domain | ATPase inhibitor, allows client loading |

| Aha1 | Middle domain | ATPase activator, facilitates chaperoning |

| Cdc37 | N-terminal domain | ATPase inhibitor, required for protein kinase client loading |

| FKBP52 | Binds both C- and N-termini | Facilitates steroid hormone receptor client folding, peptidyl prolyl isomerase |

| PP5 | C-terminal MEEVD domain | Regulates Hsp90 activity, dephosphorylates other co-chaperones, negatively regulates HSF1 |

| p23 | N-terminal domain | Facilitates ATPase activity |

| GCUNC45 | Binds both C- and N-termini | Facilitates steroid hormone receptor client folding upstream of FKBP52, peptidyl prolyl isomerase |

| CK2 | Highly charged region near N- terminus |

Phosphorylates and activates Cdc37 and Hsp90, phosphorylates and depresses FKBP52 activity |

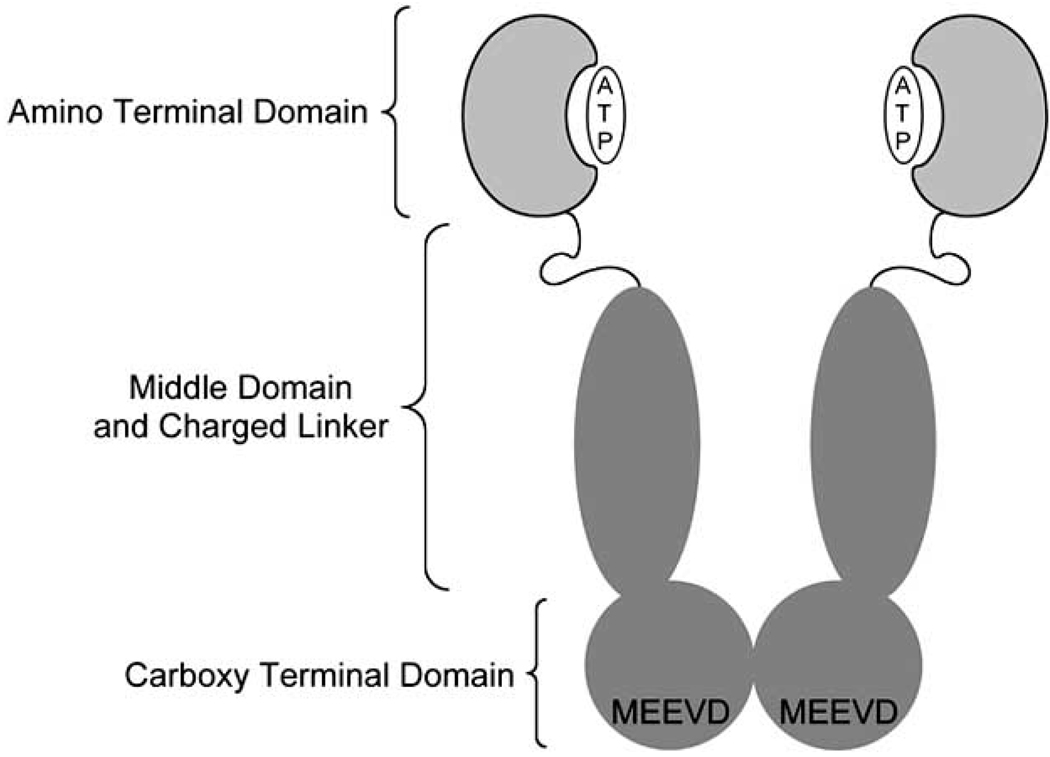

Hsp90 exists as a homodimer in solution and contains three structural domains, the C-terminus, the middle domain, and the N-terminus (Fig. 2) [58]. The Hsp90 C-terminus is important for both stabilizing Hsp90’s homodimeric nature and exhibiting allosteric control over Hsp90’s N-terminal domain [18, 66]. Intermonomeric interactions create a dimer interface consisting of a stable four-helix bundle with two-helices contributed from each monomer to form an aromatic rich dimerization interface [14, 58] While this region does not house Hsp90’s ATPase activity, it is associated with the allosteric regulation of N-terminal ATPase activity [67, 68]. The C-terminal domain contains a putative nucleotide binding site that when occupied displaces ligands bound to the N-terminus through nucleotide switching [41, 42, 69–73]. This nucleotide-binding site is believed to be the location for binding the known C-terminal inhibitors, which includes NB and its analogues.

Fig. 2.

Pictorial representation of the 3 structural domains of Hsp90.

This region includes an MEEVD domain, which is responsible for interacting with co-chaperones and immuno-philins such as HOP (Hsp organizing protein), FKBP52 (FK506 binding protein 52) that contain a a tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR, a conserved 34 amino acid sequence) [68, 74]. HOP binds the C-terminus, halts ATPase activity, and facilitates the loading of client proteins onto Hsp90 via simultaneous interactions with Hsp70 [75, 76]. Upon steroid hormone receptor loading, FKBP52 is recruited and initiates the ATPase cycle [77]. These and other co-chaperones, partner proteins, and immunophillins also influence Hsp90’s interactions with client proteins [78].

The middle domain of Hsp90, connected to the N-terminal domain by a charged linker of unconserved length that varies amongst different species, creates several important interfaces [79]. A majority of the interactions between Hsp90 and its protein clients takes place via the middle domain [80, 81]. The mechanism associated with this domain’s ability to stabilize client proteins is not well understood. In fact, only one crystal structure of Hsp90 bound to a client protein has been solved (Hsp90 bound to Cdk4) [82]. While this crystal structure provides insights into important intra-protein interactions required for client binding, the overall maturation process remains unclear. Other processes mediated by the middle domain include ATP binding and hydrolysis, due to interactions with the gamma-phosphate of ATP bound to the N-terminus, and coordination of several partner proteins including Aha1 (activator of Hsp90 ATPase homologue 1), appropriately named for its ATPase stimulating effects [58, 81, 83].

The N-terminus of Hsp90 contains an ATP-binding domain reminiscent of other members of the GHKL family of proteins [81] and is capable of ATPase activity [64, 65], which is unlike the nucleotide-binding domain located at the C-terminus. The Bergerat-fold-containing ATPase domains of GHKL family proteins like Hsp90 bind ATP in a unique, bent conformation [59]. ATP binding leads to formation of the “lid” segment of the Hsp90 molecular clamp by promoting an N-terminal dimerization event, thereby “locking” client proteins into the protein folding machine [84, 85]. The N-terminus of Hsp90 also participates in protein-protein interactions, e.g. its interaction with the ATPase-inhibiting co-chaperone Cdc37 [86].

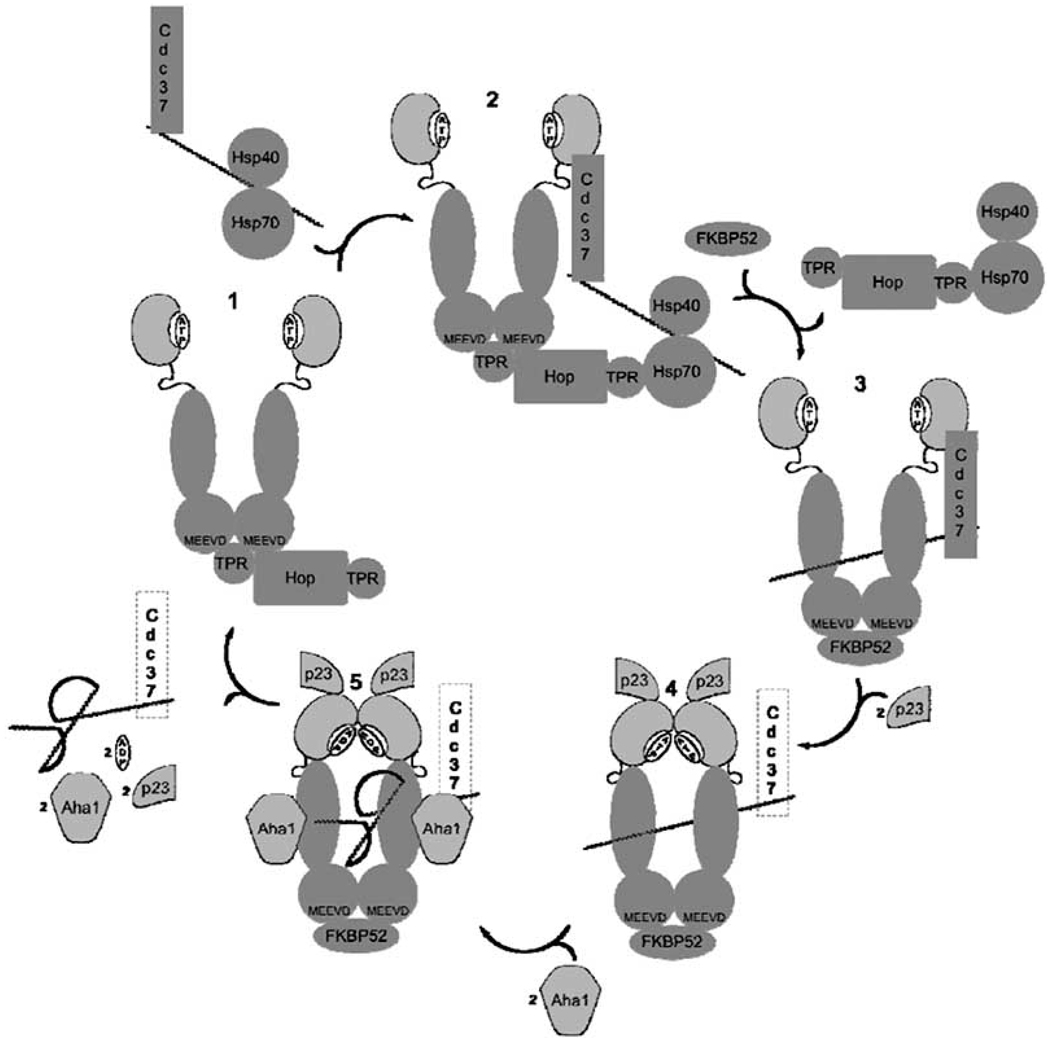

In concert, both intra- and intermolecular interactions between Hsp90’s three domains and various co-chaperones/partner proteins serve to organize the Hsp90 heteroprotein complex into a protein folding machine that serves as a modulator of protein conformation [87]. The mechanism by which the Hsp90 protein folding machinery manifests its protein folding activity has been extensively reviewed (Fig. 3) [10, 16, 18, 24, 56, 58, 86, 88]. Succinctly, nascent polypeptides corresponding to mature steroid hormone receptors, associated with the Hsp70/Hsp40 complex, interact with HOP, which then simultaneously binds the EEVD domains of both Hsp70 and Hsp90 via HOP’s two TPR domains. This interaction prohibits N-terminal dimerization, Hsp90’s ATPase activity and facilitates client transfer to Hsp90. In the case of protein kinase clients, the Hsp70/ Hsp40/client heteroprotein complex recruits Cdc37 to bind the kinase client before HOP association. The C-terminal domain of Cdc37 then interacts with the N-terminal domain of Hsp90 simultaneously while HOP bridges both Hsp70 and Hsp90 in order to facilitate substrate transfer to Hsp90. Once the client is loaded, co-chaperones and immunophillins bind Hsp90 in order to form a heteroprotein complex, which binds ATP at the N-terminus. Subsequent N-terminal dimerization occurs, resulting in formation of a molecular clamp around the client, which is further stabilized by recruitment of p23. Aha1 is recruited to the middle domain of each Hsp90 monomer and stimulates the hydrolysis of ATP, proper folding of the client, and eventually, client release. The exact mechanism of folding and stabilization of client proteins is not well defined [81].

Fig. 3.

Hsp90 protein folding process for protein kinase clients. 1–2) After first associating with Hsp70, Hsp40, and then Cdc37, nascent polypeptide is recruited to Hsp90 by HOP and Cdc37, both of which inhibit ATPase activity. 2–3) Peptide is loaded onto Hsp90 and HOP/Hsp70/Hsp40 protein complex is replaced by FKBP52 (or other immunophilin) 3–4) p23 is recruited to the heteroprotein complex, and N-terminal dimerization ocurrs. 4–5) Aha1 binds Hsp90 middle domain, whereupon client folding process takes place and ATP is hydrolysed to ADP. 5–1) After ATP hydrolysis, the molecular clamp is forced open, mature kinase client is released, and ADP is replaced by ATP so that the catalytic cycle may repeat.

THE STATUS QUO

Clinical Agents

Several classes of compounds have been and are being developed to modulate the Hsp90 protein folding machinery for therapeutic benefit. Currently, all Hsp90 modulators in clinical development are being investigated for their efficacy as anti-cancer agents [20, 31, 89–91]. This anti-cancer activity is related to the diverse nature of Hsp90 client proteins. Clients of the Hsp90 protein folding machinery highlight the potential for this chemotherapeutic target because these substrates are represented in all six hallmarks of cancer as defined by Weinberg and Hanahan (Table 2) [22–24, 92]. Consequently, inhibition of Hsp90 results in simultaneous disruption of all six hallmarks of cancer through modulation of a single target.

Table 2.

Representative Examples of Hsp90 Client Proteins and Physiological Role in Cancer Development

| Client Protein | Stage of Cancer Development |

|---|---|

| Raf-1, Akt, Her-2, Mek, Bcr-Abl, EGFR, FGFR | 1. Self-sufficiency in growth signals |

| Wee1, Myt1, Cdk4 | 2. Insensitivity to anti-growth signals |

| Rip, Akt, mutant p53, survivin | 3. Evasion of apoptosis |

| Telomerase | 4. Unlimited replicative potential |

| Fak, Akt, Hif-1α | 5. Sustained angiogenesis |

| c-Met, MMP | 6. Metastasis and tissue invasion |

Justification for Hsp90 as a target for the development of cancer chemotherapeutics has been extensively reviewed [12, 17, 25, 27, 30, 47, 49, 51, 53, 89, 93]. Briefly, Hsp90 has been implicated in oncogenic transformation, serving to stabilize otherwise highly unstable oncoproteins and promoting oncogenic propogation. Furthermore, oncogene addiction and stressed cellular environments present in cancer cells make these proteins more dependent on Hsp90 function than normal cells. As an indication of this, Hsp90 comprises 4–6% of total protein in cancer cells, which is about 4 times higher than levels found in normal cells. Also, in cancer cells Hsp90 primarily exists as the heteroprotein complex, which exhibits higher affinity for both ATP and ligands than the homodimeric form present in normal cells. These attributes result in an unusually high differential selectivity, which has been observed for Hsp90 inhibitors in transformed versus non-transformed cells.

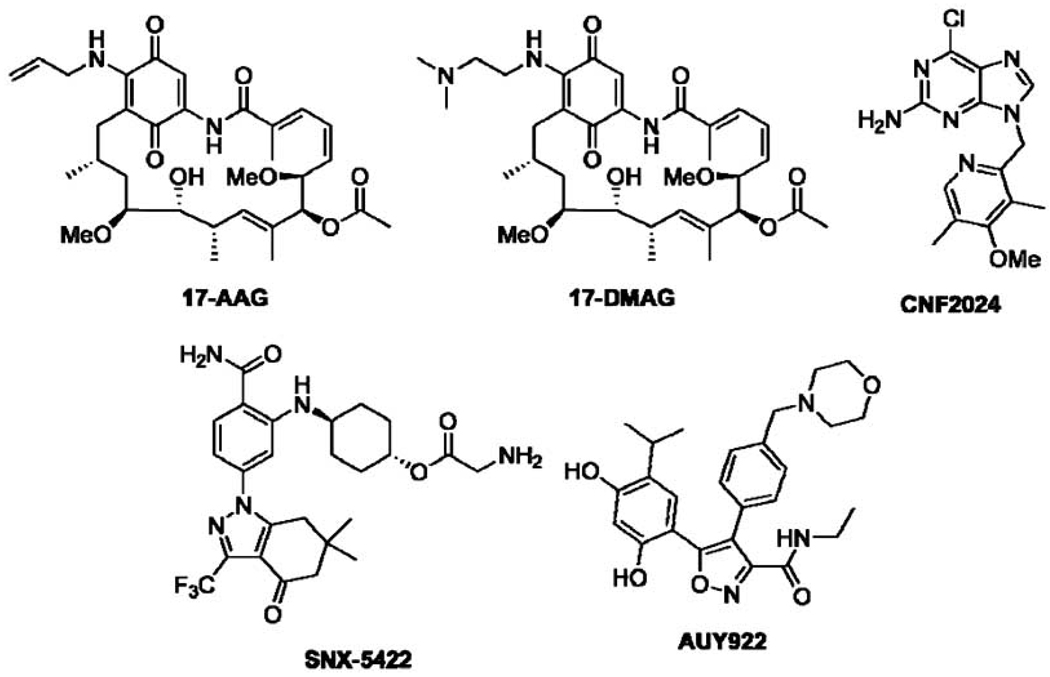

So far, all Hsp90 inhibitors in the clinic rely on a common mechanism of action that involves competitive binding of a drug to the N-terminal ATP-binding site of Hsp90 [94]. While efficacy is achieved, therapeutic limitations have manifested. Hepatotoxicity and the development of multidrug resistance via the expression of Pgp efflux pumps were the first limitations observed for the GDA-based inhibitors, 17-AAG and 17-DMAG (Fig. 4), that entered clinical trials [32]. These limitations are believed to result from reactive structural motifs present in these inhibitors, namely the redox active benzoquinone. Structural drawbacks of GDA-based inhibitors have led to the investigation and development of several synthetically-derived Hsp90 inhibitors, which are currently the focus of several clinical trials including CNF2024, SNX-5422, and AUY922 (Fig. 4) [90, 94]. While these compounds have overcome many of the toxicity issues associated with the GDA-derived inhibitors, a compromising hallmark of N-terminal Hsp90 inhibition remains, induction of the heat shock response.

Fig. 4.

Examples of Hsp90 N-terminal inhibitors in clinical trials.

All Hsp90 modulators that bind to the N-terminal ATP binding site induce the over-expression of Hsps including Hsp27, Hsp40, Hsp70, and Hsp90 [95]. This phenomenon, known as the heat shock response, also occurs in the presence of cellular stressors such as extreme temperatures or oxidative stress [96]. The transcription factor responsible for Hsp induction is heat shock factor 1 (HSF1), which is normally bound to Hsp90 [97]. N-terminal inhibitors disassemble the Hsp90-HSF1 complex whereupon, HSF1 trimerizes, becomes phosphorylated, and translocates to the nucleus [98]. Subsequently, HSF1 binds the heat shock binding elements and initiates transcription of the heat shock genes. Due to the anti-apoptotic and pro-survival effects manifested by Hsps, their overexpression in cancer cells may limit the potential of N-terminal inhibitors as anti-cancer agents [95, 99].

While heat shock response is likely to be detrimental for the treatment of cancer, it is beginning to show promising activity for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Several diseases associated with the central and peripheral nervous system result from the accumulation of misfolded proteins, and several agents that induce the heat shock response are now considered as potential therapeutic leads (Fig. 5). The upregulation and overexpression of Hsps not only prevents protein aggregation, but also refolds denatured proteins and resolubilizes protein aggregates [100, 101]. Therefore, Hsp’s may exhibit promising activities for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, polyglutamine disease, spinal bulbar muscular atrophy, and Huntington’s disease [102].

Fig. 5.

A4, induces heat shock response at concentrations as low as 1 nM, however exhibits no anti-proliferative activity at 100 µM.

In contrast to both cancer and neurodegenerative disorders, it is not clear whether the heat shock response stimu-lated by N-terminal inhibitors is beneficial or detrimental in regulating the effects of inflammatory and immune responses from a therapeutic perspective. Several diseases including chronic and rheumatoid arthritis [103], systemic lupus erythematosus [104], atherosclerosis [105], and diabetes [11] result from aberrant inflammatory processes and/ or auto-immune responses regulated by Hsp90. Therefore, completely delineating Hsp90’s role in these stimulatory processes could lead to additional therapeutic potential for Hsp90 inhibotors.

The overexpression of Hsp70 and other Hsps due to the heat shock response has been shown to inhibit inflammatory processes [106]. Heat shock has been demonstrated to negatively affect the transcriptional activity of nF-kB, and thereby inhibit pro-inflammatory responses. Similarly, Hsp90 function is required for the proper functioning of Monarch-1, a negative regulator of NIK, the nF-kB inducing kinase [107]. In contrast, however, Hsp90 is also associated with several proteins necessary for pro-inflammatory signaling. For instance, Hsp90 is required for the stabilization of the IKK complex, a pro-inflammatory mediator. Other examples include NOD1, NOD2, IPAF/NLRC4, and cryopyrin/NALP3/NLRP3. Together, inhibition of Hsp90 appears to illicit a multifaceted approach toward the regulation of inflammation [108].

Of Growing interest in the field of Hsp90 modulation is the development of strategies for chaperone inhibition through mechanisms that do not induce the heat shock response. Such strategies may not only provide an effective means of targeting Hsp90 for therapeutic use in cancer, but also for safely attenuating the effects incurred in other diseases.

STRATEGIES OF HSP90 INHIBITION AND AN EVALUATION OF NEW MODULATORY DOMAINS

C-Terminal Inhibition

The ATP binding site located at the Hsp90 C-terminus has been shown to allosterically modulate Hsp90’s N-terminal ATPase activity [18, 66]. Thus, the C-terminal binding domain presents a novel molecular strategy towards controlling Hsp90 chaperone activity. As a strategy for cancer chemotherapy, C-terminal inhibition possesses a major advantage over N-terminal inhibition; there is no heat shock response induced upon ligand binding by NB-derived compounds that contain an aryl-substituted amide side chain [40–42, 109]. Several compounds have been shown to manifest Hsp90 inhibition by binding to this C-terminal region, including epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) [110], cis-platin [111, 112], molybdate [71], and taxol [113, 114] NB and the related coumarin compounds, however, are the only C-terminal inhibitors undergoing development as potential therapeutic agents at present.

The coumarin antibiotics, NB, chlorobiocin, and coumarmycin A1, represent the originally identified Hsp90 C-terminal inhibitors [41, 42]. Among them, NB is the most extensively investigated molecule undergoing studies for pre-clinical application. NB was formerly investigated for clinical applications in Europe for its antimicrobial properties resulting from DNA gyrase B inhibitory activity [115]. It was this DNA gyrase B inhibitory activity that spurned researchers to investigate whether this molecule also exhibits Hsp90 inhibitory activity.

Marcu et al. hypothesized that due to structural similarities between the ATP-binding sites of the GHKL family of proteins, of which both Hsp90 and DNA gyrase B are members, the coumarin containing compounds may also bind Hsp90’s N-terminal ATP binding domain. Through affinity chromatography, the researchers determined that NB immobilized on sepharose beads retained Hsp90, however, treatment of the beads with either soluble GDA or RAD did not lead to the elution of Hsp90, suggesting an allosteric mechanism for controlling Hsp90 function [41, 42].

The biological effects of NB were subsequently investigated. SKBr3 breast cancer cells and v-src-transformed NIH 3T3 fibroblasts treated with NB resulted in the depletion of Raf-1, erbB2, mutant p53, and v-src, at concentrations between 300 µM and 800 µM. NB did not deplete the levels of scinderin, an actin associating protein and not an Hsp90 client, and also did not effect the levels of Grp78, a protein related to Hsp70. This latter result was in contrast to GDA and RAD, which commonly induce the expression of Grp78, and provided the first indication that NB treatment did not induce a heat shock response [41, 42].

Since it was observed that GDA and RAD do not compete for NB binding, it was proposed that NB may interact with Hsp90 via a novel mechanism. Previous studies suggested that Hsp90 contained more than one ATP binding domain as reported by Csermly et al. [18], and consequently, this potential was investigated. Exploration of the NB-Hsp90 interaction involving affinity chromatography of Hsp90 fragments was conducted to determine the region of NB binding. Again, sepharose beads containing immobilized NB were exposed to solutions of various C-terminal Hsp90 fragments. In the end, it was determined that the C-terminal fragment containing residues 538 through 728 was retained on the beads, and that the peptide fragment consisting of residues 657 through 677 was essential to NB binding, shedding light on a previously undiscovered C-terminal ATP binding domain proximal to the dimer interface [41, 42].

Other phenotypic effects derived from NB inhibition of Hsp90 have been investigated. Proteolytic fingerprinting, involving trypsinolysis of Hsp90 and characterization of the fragments, indicated that NB binding to Hsp90 induced a conformation of the protein distinct from that observed upon binding GDA. The influence of NB binding on the interactions of Hsp90 with co-chaperones and partner proteins has also been investigated. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that NB reduces the amount of co-adsorbed Hsc70, p23, HOP, PP5, and FKBP52, however, NB did not alter the co-adsorption of Cdc37 as determined by Western blot analyses [69]. Subsequent studies demonstrated disruption of Cdc37-Hsp90 interactions by NB [116]. Additional investigation into the effects manifested by NB on Cdc37-Hsp90 interactions is currently underway.

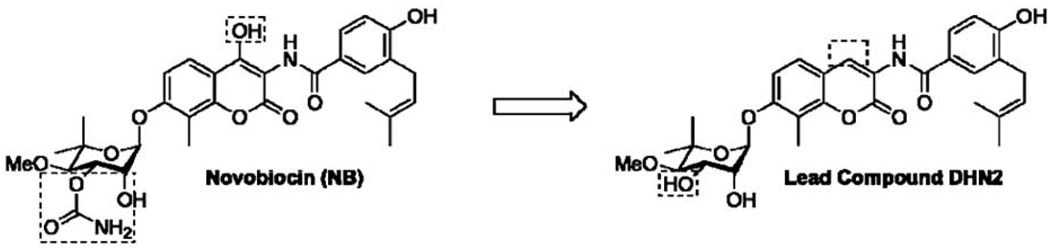

NB is under investigation by two research groups as a lead compound for the development of Hsp90 C-terminal inhibitors [39, 40, 117]. While no co-crystal structure of a C-terminal inhibitor such as NB bound to Hsp90 exists, significant advances have been made toward elucidation of structure-activity relationships for NB. For instance, Burlison et al. demonstrated that few structural changes were required to convert the potent DNA gyrase B inhibitor into a potent Hsp90 inhibitor [109]. This transformation was accomplished by removal of the 4-hydroxy group on the coumarin scaffold as well as the carbamate moiety on the noviose sugar (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The transformation of NB, a DNA gyrase B inhibitor (DNA gyrase IC50 of 1 µM, Hsp90 IC50 of ∼700 µM), into lead compound DHN2 (DNA gyrase IC50 of >500 µM, Hsp90 IC50 of 1 µM) for the development of novel C-terminal inhibitors. Dashed boxes highlight regions where removal of functionality lead to increased potency.

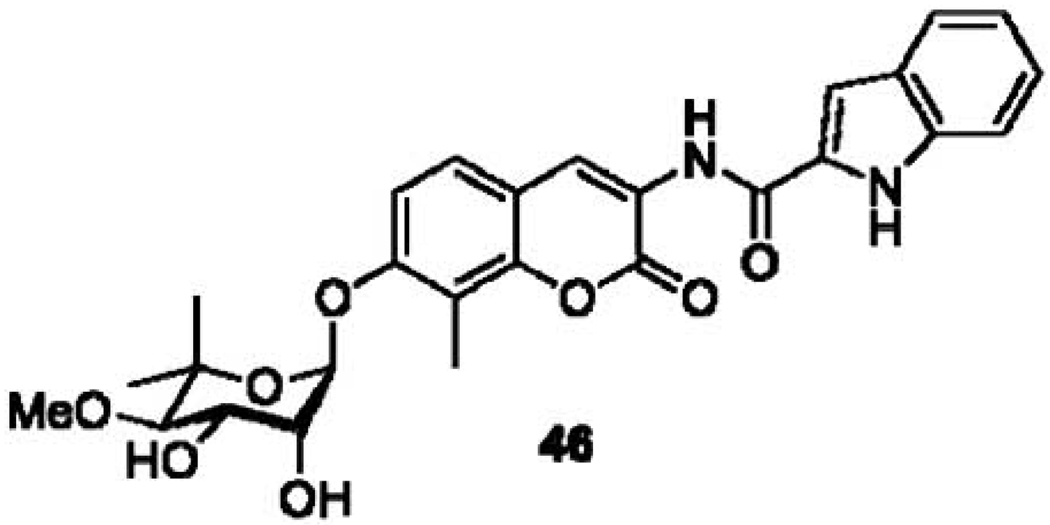

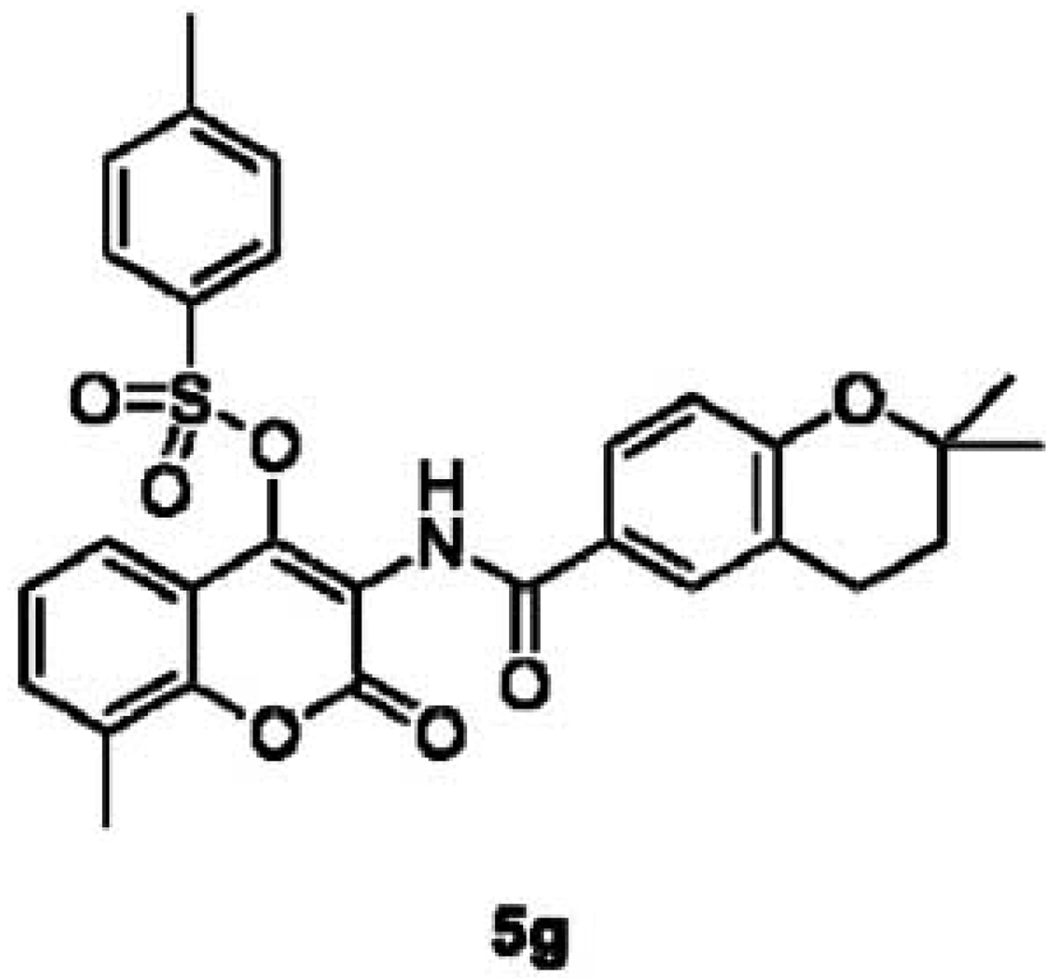

The lead compound generated from initial exploration of SAR for NB has undergone subsequent optimization. After determining molecular characteristics necessary for Hsp90 inhibition, Burlison et al. sought to optimize the benzamide side chain on the lead compound DHN2 (Fig. 6), as well as to investigate the role of the noviose sugar. The researchers found an optimized side chain to contain a rigid two-carbon linker, as indicated by indole derivative 46 (Fig. 7), the most active analogue in the series [118]. Radanyi and coworkers later demonstrated that denoviosylated coumarin analogues also manifested Hsp90 inhibitory activity, however with a concomitant reduction in potency (Fig. 8). They also demonstrated that, while the 4-hydroxy moiety was detrimental to anti-proliferative activity, the 4-tosylphenol retained activity [119, 120]. This result reaffirmed the hypothesis by Burlison et al. that the benzamide side chain occupied a large, hydrophobic pocket.

Fig. 7.

Compound 46, incorporating the indole moiety as a substitute for the prenylated benzamide increased potency of DHN2 lead from 1 µM to compound 46 with an IC50 of 170 nM in HCT-116 colon cancer cell line.

Fig. 8.

Compound 5g, a simplified denoviosylated NB analog that inhibits Hsp90 and manifests antiproliferative activity with an IC50 of 35 µM.

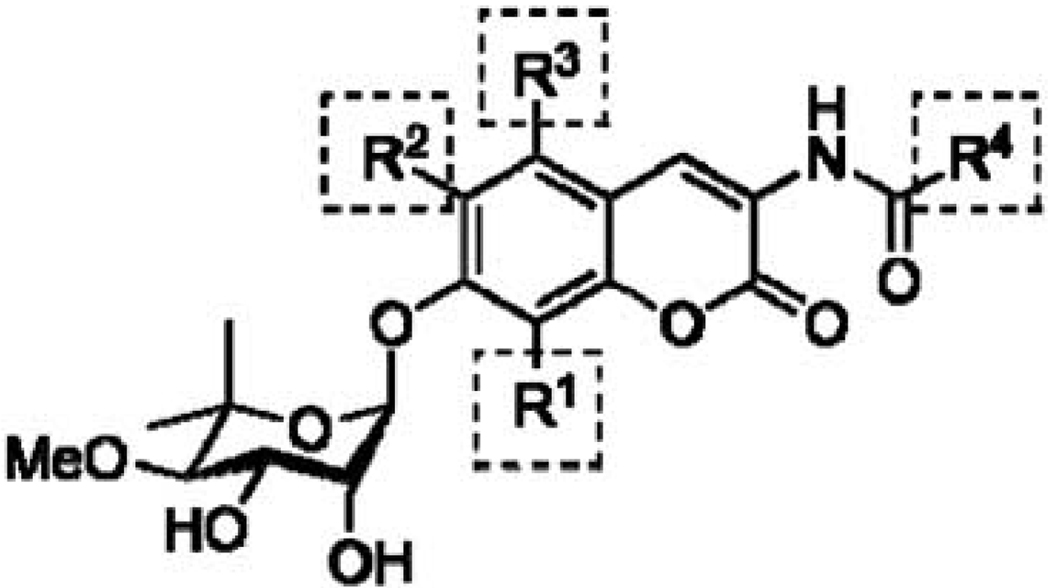

Donnelly and coworkers further elaborated SAR for the NB-derived compounds by investigating the effects of incorporating various alkyl and alkoxy substitutuents in the 5-, 6-, and 8-positions of the coumarin scaffold (Fig. 9). The researchers determined that substitution at the 5-position of the coumarin scaffold was detrimental to anti-proliferative activity, but bulky, alkoxy substituents at the 6-position along with an 8-methoxy group provided more active compounds. Also of significance, these researchers demonstrated that the lactone moiety was not necessary for retention of Hsp90 inhibitory activity [121]. The most potent NB analogue published to date remains the indole derivative, 46. Investigation of the noviose appendage and its SAR remain under study.

Fig. 9.

SAR developments garnered from coumarin substituent effects investigated by Donnely et al. Methoxy substituent at R1 increases activity, Bulky alkoxy substituents tolerable at R2, substitution at R3 decreases Hsp90 inhibitory activity, most active side chain is indole at R4.

Disruption of Co-Chaperone/Hsp90 Interactions

As described above, Hsp90 is the central component of a large cohort of proteins that make up the Hsp90 protein folding machinery. Each protein-protein interaction presents the opportunity for disruption of the protein folding process, and therefore, a potential therapeutic application. To date, only two Hsp90 protein-protein interactions have been targeted for drug development: 1) interactions between Hsp90 and the co-chaperone Cdc37; and 2) interactions between Hsp90 and the partner protein HOP.

Disruption of the Cdc37/Hsp90 interaction

Cdc37 is required for the maturation of Hsp90-dependent protein kinases, and is critical for the stabilization of several otherwise unstable oncoprotein kinases, e.g. BRAF and EGFRvIII, in cancer cells [122–125]. Cdc37 overexpression has been linked to oncogenic transformation, and interruption of its interaction with Hsp90 has been explored as a therapeutic target [126–128]. siRNA experiments have been conducted that demonstrate Cdc37 knockdown is associated with the depletion of several Hsp90 protein kinase clients including Her-2, Raf-1, Cdk4, and Akt. Also of significance, siRNA-mediated knockdown of Cdc37 does not result in induction of the heat shock response, therefore providing a unique mechanism for Hsp90 modulation [129, 130].

Only one small molecule, celastrol, has been reported to affect disruption of Cdc37/Hsp90 protein-protein interactions [43]. Celastrol is a quinone methide triterpene isolated from Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F. (the Chinese Thunder of God vine) [131]. It has been hypothesized that celastrol binds the Hsp90 N-terminus at the interface between the C-terminus of Cdc37 and Hsp90, thereby disrupting this protein-protein interaction [43]. However, a recent report suggests that celastrol forms a Michael adduct with cysteine residues of Cdc37, and therefore acts as an irreversible inhibitor [132]. Celastrol has also been reported to induce of the heat shock response, in concert with its Cdc37-Hsp90 disupting activity [133, 134]. It appears as though celastrol may manifest anti-proliferative effects through several mechanisms, and therefore, further studies into the exact mechanism of celastrol’s inhibitory effects on Hsp90 remain under investigation.

The identification and subsequent validation of celastrol as a small molecule disruptor of Hsp90/Cdc37 interactions could lead to the elucidation of additional small molecules that exhibit similar activities. For instance, celastrol was recognized as a novel Hsp90 inhibitor from evaluation of its biological effects through the novel Connectivity Map technology. Gedunin, a tetranortriterpenoid from Azadirachta indica (Indian Neem Tree) was simultaneously identified during these studies [135, 136]. The structural similarity between celastrol and gedunin (Fig. 10), along with similar traditional medicinal applications for the species from which they were isolated [137–139], may be indicative of a common mechanism of action, although these studies have not yet been reported.

Fig. 10.

Celastrol, a known Hsp90 inhibitor that disrupts the Cdc37/Hsp90 interaction, and other potential inhibitors gedunin, gamendazole, and the gedunin derivatives 7-desacetylcarbamategedunin and 7-oxogedunin.

The Connectivity Map technology represents a systematic tool for identifying connections between diseases, genetic perturbations, and drug action. This technology provides potential for the discovery of novel protein targets and lead compounds for the development of directed therapeutic strategies against various disease states. Briefly, a “connectivity map” is generated by evaluating the positive or negative expression levels of mRNA that result upon incubation of small molecules with cellular models of various disease states. It was hypothesized that similar profiles of mRNA expression levels after evaluation would be indicative of small molecules that manifest similar mechanisms of action or related protein dysfunctions, respectively. In a demonstration of connectivity mapping, Lamb et al. evaluated several small molecules and disease states and determined “connections” in their initial report. Of significance, the natural products gedunin and celastrol were identified as inhibitors of the Hsp90 protein folding machinery through this technology [135].

Through connectivity map screening, both celastrol and gedunin induced expression levels of varying mRNA molecules analogous to 17-AAG. Hsp90 inhibition was then validated through Western blot analyses to demonstrate the induced degradation of Hsp90-dependent client proteins. While celastrol has not undergone optimization, several semi-synthetic derivatives of gedunin have been synthesized and validated as Hsp90 inhibitors. No derivative manifested anti-proliferative activity greater than the parent compound, however, non-electrophilic derivatives were identified (Fig. 10) [140].

Both the Thunder of God vine and the Neem Tree are used in traditional medicine practices to treat a variety of inflammatory and auto-immune diseases including cancer, and both natural products manifest anti-spermatogenic properties [141, 142]. This anti-spermatogenic capacity is shared with another Hsp90 inhibitor, gamendazole, a synthetic small molecule [28]. The mode by which gamendazole (Fig. 10) exhibits Hsp90 inhibition is currently unknown, however, all three compounds contain an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl system.

Gamendazole was recently identified as an Hsp90 inhibitor while probing its mechanism of anti-spermatogenic activity. Gamendazole demonstrated both Hsp90 and EEF1A1 binding activity via affinity purification, competition experiments, the in vitro rabbit reticulocyte assay and by western blot analyses, which demonstrated a dose-dependent down regulation of Hsp90 client proteins AKT and erbB2 [28].

Disruption of the HOP/Hsp90 Interaction

HOP is essential for facilitating client protein loading onto the foldosome, and is therefore an essential component of the protein folding process [76]. Small molecule inhibitors of this protein-protein interaction would be capable of preventing Hsp90 client proteins from receiving chaperone activity. No natural product inhibitors have been described that manifest this biological activity. However, Yi and Regan have reported the identification of a class of synthetic small molecules capable of disrupting this interaction by binding to the TPR domain of HOP [44, 45]. The researchers developed an AlphaScreen-based high-throughput assay capable of identifying this desired phenotype. Succinctly, Hsp90 is N-terminally linked to a donor bead while an N-terminal TPR expressing protein fragment is C-terminally linked with an acceptor bead. The TPR domain is free to interact with the MEEVD domain of Hsp90. Excitation of the donor bead at 680 nm leads to the production of singlet oxygen, which is capable of traveling the 200 nm distance between the donor and acceptor. If the MEEVD and TPR domains are interacting, the acceptor bead undergoes chemiluminescence at 520 nm to 620 nm. In the presence of a disrupter of HOP/Hsp90 interactions, the MEEVD and TPR domains are kept separate, and no chemiluminescence is observed. Several small molecules were identified during initial screening with this assay (Fig. 11). However, optimization of the hit compounds identified has not been reported, but the results obtained thus far are encouraging. Of note, these small molecule disrupters do not appear to manifest the heat shock response, suggesting that disruption of the HOP/Hsp90 complex could eventually lead to efficacious alternatives to N-terminal inhibition.

Fig. 11.

Compounds identified through AlphaScreen HTS to inhibit Hsp90/Hop interaction by binding to the TPR domain of Hop.

Disruption of Hsp90’s Interaction with Client Proteins

While all Hsp90 inhibitors disrupt Hsp90’s interaction with client proteins, little investigation into small molecules that specifically target the protein-protein interface between Hsp90 and a client has been undertaken. An inhibitor with the ability to specifically interrupt a single client from interacting with Hsp90 may be significant to the development of therapies for disease states other than cancer, where often only one client protein manifests aberrant activity. The delay in this area of Hsp90 research is likely due to the lack of an understanding of exactly how these protein-protein interactions occur. While a crystal structure of the Hsp90-Cdc37-Cdk4 complex has been solved [82], no inhibitor has been developed to specifically target this motif. However, the client/chaperone complex between survivin and Hsp90 has been pursued. Shepherdin, a synthetic small molecule, was developed in order to disrupt the survivin/Hsp90 interaction. Survivin is a member of the Inhibitors of Apoptosis family, and manifests its anti-apoptotic effects by inhibiting various caspases. Specific disruption of survivin maturation by Hsp90 represents a highly selective strategy for cancer chemotherapy since survivin expression is present in tumors, but is absent in normal cells. Efficacy has been demonstrated for shepherdin in models of leukemia, although it is not clear whether this is due to specific disruption of survivin/Hsp90 interactions. Cells treated with shepherdin also demonstrated that other client protein levels are adversely affected. Interestingly, shepherdin treatment does not lead to induction of a heat shock response [143].

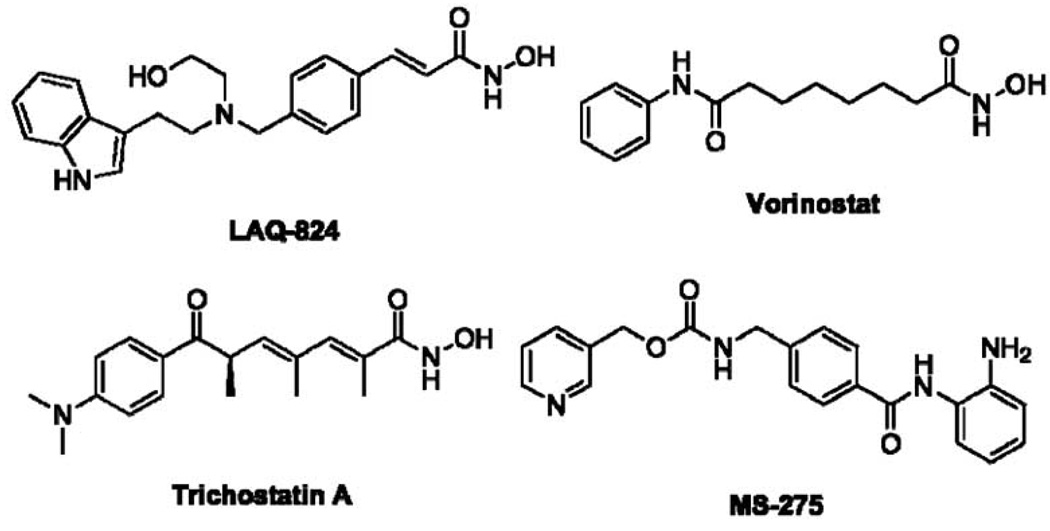

Hsp90 Hyperacetylation by the Inhibition of HDACs

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) have been found not only to deacetylate lysine residues on histones, but also lysines on Hsp90 and other proteins [144, 145]. Specifically, HDAC6 has been shown to deacetylate Hsp90, and a role for HDAC1 in this process has also been proposed [146]. Inhibitors of this target present a novel opportunity for indirect Hsp90 inhibition. Prior studies have demonstrated that the foldosome is inactivated by hyperacetylation of Hsp90 in experiments involving HDAC knockdown [147]. siRNA induced HDAC6 specific or global HDAC knockdown as well as treatment with HDAC6 specific or pan-HDAC inhibitors was demonstrated to dissolve Hsp90/client protein association. Several selective and pan-HDAC inhibitors have been investigated for their effects on Hsp90, including trichostatin A [148], LAQ-824 [149], vorinostat [150], and MS-275 (Fig. 12) [151], all of which led to degradation of Hsp90-dependent client proteins and manifestation of anti-proliferative activity. Specific inhibition of HDAC6 using siRNA has manifested induction of the heat shock response, however, the non-specific HDAC inhibitors FK228 and vorinostat lead to hyperacetylation of both Hsp90 and Hsp70, and demonstrate no heat shock response [150].

Fig. 12.

Examples of HDAC inhibitors that manifest Hsp90-dependent client protein degradation.

Inhibitors of Hsp90 for the Treatment of Several Pathogenic States

Hsp90’s clientele represent a broad spectrum of activities from protein kinases to steroid hormone receptors to telomerase, and represent numerous physiological processes. This diversity makes Hsp90 unique among other chaperones and presents the opportunity for affecting a variety of signaling pathways through the modulation of a single target. Hsp90, therefore, offers the potential to affect several therapeutic areas including pathogenic infection, cystic fibrosis, and male contraception. The induction of heat shock response appears to be contraindicated in these disease states, and therefore, the use of Hsp90 inhibitors that do not cause such a response are desired.

Hsp90’s Role in Pathogenic Infection

Molecular chaperones play a key role in the infection process for a variety of invasive organisms including fungi, bacteria, and viruses. Upon entering a host cell, a pathogen is presented to a stressed environment and relies upon the expression of molecular chaperones for the maintenance of protein function [152]. Several species of pathogenic fungi, including Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans, Aspergillus spp., Histoplasma capsulatum, and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, rely on the expression of molecular chaperones, with fungal Hsp90 (also called Hsp82) of particular importance. Hsp82 is not known to be as intimately involved with de novo protein folding as its human counterpart. Rather, it is commonly associated with difficult to fold proteins such as Wee1, Mik1, and Swe1. The over-expression of Hsp82 in fungal infections in mice is directly proportional to increased virulence. Hsp82 is also extensively expressed on the cell surface of several fungal species, and acts as an immune response signal to the host. GDA, RAD, novobiocin, and cisplatin all manifest antifungal activity. Targeting cytosolic fungal Hsps with selective inhibitors and membrane bound Hsps with anti-body fragments represent a potential approach for antifungal therapy and overcoming drug resistance [54, 55, 153–156].

Similar to pathogenic fungal species, several pathogenic bacterial and protozoan species also rely on molecular chaperones for successful invasion and virulence. Bacterial and protozoan species also express membrane bound Hsps. In bacterial species, the homologue of Hsp90 is HtpG [157]. Strategies for targeting bacterial and protozoan infections such as Escherichia coli or Leishmania, respectively, would largely be the same as those that target fungal infections and would include selective pathogen Hsp inhibition and pathogen membrane bound recognizing antibodies [158–161].

Similarly, viral infection also requires molecular chaperones, however, in contrast to fungal, bacterial, and protozoan infection, several viruses including the Denge virus, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, the influenza virus and the vesicular stomatitis virus, are capable of hijacking the host cell’s protein folding machinery for the maturation of viral encoded proteins associated with virus entry and multiplication. For example, host Hsp90 has been demonstrated to be required for the maturation of hepatitis B (HBV) reverse transcriptase, hepatitis C NSP2/3 protein, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of Influenza A. Also, certain client proteins have been implicated to play a critical role in viral infection such as Akt. In some cases, it has even been demonstrated that the virus incorporates host chaperones within its capsid prior to leaving the host cell so that they are readily available upon infection of other cells. Less commonly, viral genomes can encode for chaperone-like molecules [152, 162–165].

Treatment of cells with Hsp90 inhibitors has demonstrated efficacy in models of viral infection. Also of significance, targeting host Hsp90 in viral infected cells may prove an important strategy for circumventing resistance. Since, in most cases, the viral genetic information does not encode for a chaperone, mutation of the virus could not lead to resistance to Hsp90 inhibition.

Cystic Fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis is a disease characterized by protein dysfunction. Generally, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) suffers a mutation, most commonly ΔF508, that prevents proper folding and trafficking to the cell membrane. Wild type CFTR undergoes an extensive, complicated, and inefficient biological synthesis and requires several chaperones, including the Hsc70/Hsp70-Hdj-1/2 cohort, calnexin, CHIP, Hsp90, Bag-2, and HspBP1. Only about 25 to 60% of wt-CFTR synthesized ever completely matures depending on the cell line. The biogenesis of mutated CFTR is even more inefficient. Hsp90 chaperoning is involved in promoting the degradation of mutant CFTR by the proteasome. Both Hsp90 inhibitors and siRNA knockdown of Aha1, an activator of Hsp90 ATPase activity, have been demonstrated to revert levels of mutant CFTR degradation by the proteasome to levels similar to that of wild type CFTR, suggesting that association of the Hsp90 heteroprotein complex with mutant CFTR may play a role in facilitating the aberrant protein function underlying cystic fibrosis. This has therapeutic effects since mutant CFTR retains its intended activity, and, therefore the disassociation of CFTR from the Hsp90 protein folding machinery manifests efficacious activity [14, 166–168].

Male Contraception

Several Hsp90 inhibitors show male contraceptive activity, including celastrol, gedunin, and gamendazole. The investigation of gamendazole’s mechanism of action for affecting male contraception suggests a role for Hsp90 inhibition in concert with inhibition of EEF1A1 in this process [28].

Sertoli cells are responsible for spermatogenesis. Both Hsp90 and EEF1A1 demonstrated affinity for binding gamendazole in affinity chromatography experiments suggesting that these proteins represent targets for this small molecule. Both of these protein targets are known to promote the integrity of AKT1, which is important for maintaining Sertoli cell-spermatid junctions. The modest inhibitory activity of both Hsp90 and EEF1A1 simultaneously may be responsible for gamendazole’s selective effect on Sertoli cells. Several other effects resulting from gamendazole administration to Sertoli cells were also observed including NFKB down regulation and the disruption of actin bundles [28].

CONCLUSIONS

Hsp90 has emerged as a therapeutic target to treat a variety of disease states including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, inflammation, pathogenic infection, cystic fibrosis, and may represent a novel based strategy to ameliorate male contraception. At present, clinical applications for Hsp90 modulation have focused only on the treatment of cancer, and all clinically administered agents are competitive inhibitors of the N-terminal ATP binding site. While efficacy is achieved, induction of the heat shock response occurs, leading to potential drawbacks for N-terminal inhibitory use. Results from ongoing clinical trials will be integral in determining whether induction of the heat shock response will lead to clinical limitations for N-terminal Hsp90 inhibitors as anti-cancer agents.

Induction of a heat shock response is desirable in some therapeutic areas where a deficiency of Hsp chaperoning activity is observed. Examples include various neurodege-nerative disorders, aberrant inflammatory and immuno-response diseases, and cardio-protection. Non-toxic N-terminal inhibitors could find application in these areas, however, none currently exist.

In contrast, a subset of disorders would benefit from the clinical development of Hsp90 inhibitors that do not induce the heat shock response. This review has delineated several strategies for Hsp90 inhibition that do not inducte the heat shock response, including Hsp90 C-terminal inhibition, Hsp90/co-chaperone interaction disruption, specific Hsp90/ client protein disruption, and Hsp90 hyperacetylation.

The past twenty-five years have witnessed an exponential growth in Hsp90 research. From defining Hsp90s role in numerous biological processes to validating Hsp90 as target for cancer chemotherapy, and at present, establishing Hsp90 as a potential target for other therapeutic areas.

REFERENCES

- 1.Paul S. Dysfunction of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in multiple disease conditions: therapeutic approaches. Bioessays. 2008;30:1172–1184. doi: 10.1002/bies.20852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Messaed C, Rouleau GA. Molecular mechanisms underlying polyalanine diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 2009;34:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas SR, Witting PK, Drummond GR. Redox control of endothelial function and dysfunction: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2008;10:1713–1753. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clavaguera F, Bolmont T, Crowther RA, Abramowski D, Frank S, Probst A, Fraser G, Stalder AK, Staufenbiel MBM, Jucker M, Goedert M, Tolnay M. Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:909–914. doi: 10.1038/ncb1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vardiman JW. Chronic myelogenous leukemia, BCR-ABL1+ Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2009;132:250–260. doi: 10.1309/AJCPUN89CXERVOVH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jouret F, Devuyst O. CFTR and defective endocytosis: new insights in the renal phenotype of cystic fibrosis. Pflugers Arch. 2009;457:1227–1236. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naidoo N. The endoplasmic reticulum stress response and aging. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;20:23–37. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2009.20.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alcain FJ, Villalba JM. Sirtuin activators. 19. 2009;4:403–414. doi: 10.1517/13543770902762893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehman NL. The ubiquitin proteasome system in neuropathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:329–347. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0560-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wegele H, Muller L, Buchner J. Hsp70 and Hsp90-a relay team for protein folding. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004;151:1–44. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soti C, Nagy E, Giricz Z, Vigh L, Csermely P, Ferdinandy P. Heat shock proteins as emerging therapeutic targets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005;146:769–780. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soo ETL, Yip GWC, Lwin ZM, Kumar SD, Bay B-H. Heat shock proteins as novel therapeutic targets in cancer. In Vivo. 2008;22:311–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caplan AJ, Mandal AK, Theodoraki MA. Molecular chaperones and protein kinase quality control. Trends Cell. Biol. 2007;17:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearl LH, Prodromou C, Workman P. The Hsp90 molecular chaperone: an open and shut case for treatment. Biochem. J. 2008;410:439–453. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neckers L, Tsutsumi S, Mollapour M. Visualizing the twists and turns of a molecular chaperone. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:235–236. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0309-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wandinger SK, Richter L, Buchner J. The Hsp90 chaperone machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:18473–18477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitesell L, Bagatell R, Falsey R. The stress response: implications for the clinical development of Hsp90 inhibitors. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2003;3:349–358. doi: 10.2174/1568009033481787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Csermely P, Schnaider T, Soti C, Prohaszka Z, Nardai G. The 90-KDa molecular chaperone family: structure, function, and clinical applications. A comprehensive review. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998;79:129–168. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maloney A, Clarke PA, Workman P. Genes and proteins governing the cellular sensitivity to Hsp90 inhibitors: a mechanistic perspective. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2003;3:331–341. doi: 10.2174/1568009033481822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solit DB, Chiosis G. Development and application of Hsp90 inhibitors. Drug Discov. Today. 2008;13:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stravopodis DJ, Margaritis LH, Voutsinas GE. Drugmediated targeted disruption of multiple protein activities through functional inhibition of the Hsp90 chaperone complex. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007;14:3122–3138. doi: 10.2174/092986707782793925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bishop SC, Burlison JA, Blagg BSJ. Hsp90: a novel target for the disruption of multiple signaling cascades. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:369–388. doi: 10.2174/156800907780809778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaudhury S, Welch TR, Blagg BSJ. Hsp90 as a target for drug development. ChemMedChem. 2006;1:1331–1340. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blagg BSJ, Kerr TD. Hsp90 inhibitors: small molecules that transform the Hsp90 protein folding machinery into a catalyst for protein degradation. Med. Res. Rev. 2006;26:310–338. doi: 10.1002/med.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solit DB, Rosen N. Hsp90: a novel target for cancer therapy. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2006;6:1205–1214. doi: 10.2174/156802606777812068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donnelly A, Blagg BSJ. Novobiocin and additional inhibitors of the Hsp90 C-terminal nucleotide-binding pocket. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008;15:2702–2717. doi: 10.2174/092986708786242895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amolins MW, Blagg BSJ. Natural product inhibitors of Hsp90: potential leads for drug discovery. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2009;9:140–152. doi: 10.2174/138955709787316056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tash JS, Chakrasali R, Jakkaraj SR, Hughes J, Smith SK, Hornbaker K, Heckert LL, Ozturk SB, Hadden MK, Kinzy TG, Blagg BSJ, Georg GI. Gamendazole, an orally active indazole carboxylic acid male contraceptive agent, targets Hsp90AB1 (Hsp90BETA) and EEF1A1 (eEf1A), and stimulates Il1a transcription in rat sertoli cells. Biol. Reprod. 2008;78:1139–1152. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.062679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadden MK, Lubbers DJ, Blagg BSJ. Geldanamycin, radicicol, and chimeric inhibitors of the Hsp90 N-terminal ATP binding site. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2006;6:1173–1182. doi: 10.2174/156802606777812031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Workman P. Overview: translating Hsp90 biology into Hsp90 drugs. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2003;3:297–300. doi: 10.2174/1568009033481868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiosis G, Rodina A, Moulick K. Emerging Hsp90 inhibitors: from discovery to clinic. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2006;6:1–8. doi: 10.2174/187152006774755483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breinig M, Caldas-Lopes E, Goeppert B, Malz M, Rieker R, Bergmann F, Schirmacher P, Mayer M, Chiosis G, Kern MA. Targeting heat shock protein 90 with non-quinone inhibitors: a novel chemotherapeutic approach in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2009;50:102–112. doi: 10.1002/hep.22912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X, Shocron E, Song A, Patel N, Sun CL. Discovery of 5-substituted 2-amino-4-chloro-8-((4-methoxy-3,5-dimethylpyridin-2-yl)methyl)-7,8-dihydropteridin-6(5H)-ones as potent and selective Hsp90- inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:2860–2864. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hadden MK, Blagg BSJ. Synthesis and evaluation of radamide analogues, a chimera of radicicol and geldanamycin. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:4697–4704. doi: 10.1021/jo900278g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duerfeldt AS, Brandt GEL, Blagg BSJ. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of conformationally constrained cisamide Hsp90 inhibitors. Org. Lett. 2009;11:2353–2360. doi: 10.1021/ol900783m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang M, Shen G, Blagg BSJ. Radanamycin, a macrocyclic chimera of radicicol and geldanamycin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:2459–2462. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen G, Blagg BSJ. Radester, a novel inhibitor of the Hsp90 protein folding machinery. Org. Lett. 2005;7:2157–2160. doi: 10.1021/ol050580a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clevenger RC, Blagg BSJ. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of a radicicol and geldanamycin chimera, radamide. Org. Lett. 2004;6:4459–4462. doi: 10.1021/ol048266o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen G, Yu XM, Blagg BS. Syntheses of photolabile novobiocin analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004;14:5903–5906. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu XM, Shen G, Neckers L, Blake H, Holzbeierlein J, Cronk B, Blagg BSJ. Hsp90 inhibitors identified from a library of novobiocin analogues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12778–12779. doi: 10.1021/ja0535864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcu MG, Schulte TW, Neckers L. Novobiocin and related coumarins and depletion of heat shock protein 90-dependent signaling proteins. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000;92:242–248. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marcu MG, Chadli A, Bouhouche I, Catelli M, Neckers LM. The heat shock protein 90 antagonist novobiocin interacts with a previously unrecognized ATP-binding domain in the carboxyl terminus of the chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:37181–37186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang T, Hamza A, Cao X, Wang B, Yu S, Zhan C-G, Sun D. A novel Hsp90 inhibitor to disrupt Hsp90/Cdc37 complex against pancreatic cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008;7:162–170. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yi F, Regan L. A novel class of small molecule inhibitors of Hsp90. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008;3:645–654. doi: 10.1021/cb800162x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yi F, Zhu P, Southall N, Inglese J, Austin CP, Zheng W, Regan L. An Alphascreen-based high-throughput screen to identify inhibitors of Hsp90-cochaperone interaction. J. Biomol. Screen. 2009;14:273–281. doi: 10.1177/1087057108330114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cortajarena AL, Yi F, Regan L. Designed TPR modules as novel anticancer agents. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008;3:161–166. doi: 10.1021/cb700260z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Usmani SZ, Bona R, Li Z. 17 AAG for Hsp90 inhibition in cancer--from bench to bedside. Curr. Mol. Med. 2009;9:654–664. doi: 10.2174/156652409788488757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tofilon PJ, Camphausen K. Molecular Targets for Tumor Radiosensitization. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:2974–2988. doi: 10.1021/cr800504x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Banerji U. Heat shock protein 90 as a drug target: some like it hot. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:9–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Solit DB, Osman I, Polsky D, Panageas KS, Daud A, Goydos JS, Teitcher J, Wolchok JD, Germino FJ, Krown SE, Coit D, Rosen N, Chapman PB. Phase II trial of 17-allylamino-17demethoxygeldanamycin in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:8302–8307. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neckers L. Using natural product inhibitors to validate Hsp90 as a molecular target in cancer. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2006;6:1163–1171. doi: 10.2174/156802606777811979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Powers MV, Workman P. Inhibitors of the heat shock response: biology and pharmacology. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3758–3769. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahalingam D, Swords R, Carew JS, Nawrocki ST, Bhalla K, Giles FJ. Targeting Hsp90 for cancer therapy. Br. J. Cancer. 2009;100:1523–1529. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matthews R, Burnie J. The role of Hsp90 in fungal infection. Immunol. Today. 1992;13:345–348. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burnie JP, Carter TL, Hodgetts SJ, Matthews RC. Fungal heat-shock proteins in human disease. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2006;30:53–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2005.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zuehlke A, Johnson JL. Hsp90 and co-chaperones twist the functions of diverse client proteins. Biopolymers. 2009 doi: 10.1002/bip.21292. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang X, Venable J, LaPointe P, Hutt DM, Koulov AV, Coppinger J, Gurkan C, Kellner W, Matteson J, Plutner H, Riordan JR, Kelly JW, Yates JR, 3rd, Balch WE. Hsp90 cochaperone Aha1 downregulation rescues misfolding of CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Cell. 2006;127:803–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pearl LH, Prodromou C. Structure and mechanism of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone machinery. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:271–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dutta R, Inouye M. GHKL, an emergent ATPase/kinase superfamily. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:24–28. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pratt WB, Morishima Y, Osawa Y. The Hsp90 chaperone machinery regulates signaling by modulating ligand binding clefts. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:22885–22889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800023200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Voellmy R, Boellmann F. Chaperone Regulation of the Heat Shock Protein Response. In: Csermely P, Vigh L, editors. Molecular Aspects of the Stress Response: Chaperones, Membranes and Networks. Vol. 594. New York: Landes Bioscience and Springer Science+Business Media; 2007. pp. 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Powers MV, Workman P. Targeting of multiple signalling pathways by heat shock protein 90 molecular chaperone inhibitors. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2006;13:125–135. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nadeau K, Das A, Walsh CT. Hsp90 chaperonins posses ATPase activity and bind heat shock transcription factors and peptidyl prolyl isomerases. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:1479–1487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Obermann WMJ, Sondermann H, Russo AA, Pavletich NP, Hartl FU. In vivo function of Hsp90 is dependent on ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:901–910. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Panaretou B, Prodromou C, Roe SM, O'Brien R, Ladbury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH. ATP binding and hydrolysis are essential to the function of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone in vivo. EMBO J. 1998;17:4829–4836. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Prodromou C, Siligardi G, O'Brien R, Woolfson DN, Regan L, Panaretou B, Ladbury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH. Regulation of Hsp90 ATPase activity by tetracopeptide repeat (TPR)-domain co-chaperones. EMBO J. 1999;18:754–762. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Retzlaff M, Stahl M, Eberl HC, Lagleder S, Beck J, Kessler H, Buchner J. Hsp90 is regulated by a switch point in the C-terminal domain. EMBO Rep. 2009;10(10):1147–1153. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Onuoha SC, Coulstock ET, Grossmann JG, Jackson SE. Structural studies on the co-chaperone Hop and its complexes with Hsp90. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;379:732–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yun BG, Huang W, Leach N, Hartson SD, Matts RL. Novobiocin induces a distinct conformation of Hsp90 and alters Hsp90-cochaperone-client interations. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8217–8229. doi: 10.1021/bi0497998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hartson SD, Thulasiraman V, Huang W, Whitesell L, Matts RL. Molybdate inhibitos Hsp90. induces structural changes in its C-terminal domain, and alters its interactions with substrates. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3837–3849. doi: 10.1021/bi983027s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hartson SD, Thulasiraman V, Huang W, Whitesell L, Matts RL. Molybdate inhibits Hsp90, induces structural changes in its C-terminal domain, and alters its interactions with substrates. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3837–3849. doi: 10.1021/bi983027s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garnier C, Lafitte D, Tsvetkov PO, Barbier P, Leclerc-Devin J, Millot J-M, Briand C, Makarov AA, Catelli MG, Peyrot V. Binding of ATP to heat shock protein 90. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:12208–12214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111874200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Soti C, Vermes A, Haystead TAJ, Csermely P. Comparative analysis of the ATP-binding sites of Hsp90 by nucleotide affinity cleavage: a distinct nucleotide specificity of the C-terminal ATP-binding site. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270:2421–2428. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chadli A, Bruinsma ES, Stensgard B, Toft D. Analysis of Hsp90 cochaperone interactions reveals a novel mechanism for TPR protein recognition. Biochemistry. 2008;47:2850–2857. doi: 10.1021/bi7023332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Odunuga OO, Longshaw VM, Blatch GL. Hop: more than and Hsp70/Hsp90 adaptor protein. Bioessays. 2004;26:1058–1068. doi: 10.1002/bies.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen S, Smith DF. Hop as an adaptor in the heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) and Hsp90 chaperone machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:35194–35200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.35194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Davies TH, Sanchez ER. FKBP52. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005;37:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Caplan AJ. What is a co-chaperone? Cell Stress and Chaperones. 2003;8:105–107. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2003)008<0105:wiac>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hainzl O, Lapina MC, Buchner J, Richter K. The charged linker region is an important regulator of hsp90 function. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:22559–22567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.031658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hawle P, Siepmann M, Harst A, Siderius M, Reusch HP, Obermann WM. The middle domain of Hsp90 acts as a discriminator between different types of client proteins. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:8385–8395. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02188-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meyer P, Prodromou C, Hu B, Vaughan C, Roe SM, Panaretou B, Piper PW, Pearl LH. Structural and functional analysis of the middle sigment of Hsp90: implications for ATP hydrolysis and client protein and cochaperone interactions. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:647–658. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vaughan CK, Gohlke U, Sobott F, Good VM, Ali MMU, Prodromou C, Robinson CV, Saibil HR, Pearl LH. Structure of an Hsp90-Cdc37-Cdk4 complex. Mol. Cell. 2006;23:697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lotz GP, Lin H, Harst A, Obermann WMJ. Aha1 binds to the middle domain of Hsp90, contributes to client protein activation, and stimulates the ATPase activity of the molecular chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:17228–17235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stirling PC, Bakhoum SF, Feigl AB, Leroux MR. Convergent evolution of clamp-like binding sites in diverse chaperones. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:865–870. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Prodromou C, Panaretou B, Chohan S, Siligardi G, O'Brien R, Ladbury JE, Roe SM, Piper PW, Pearl LH. The ATPase cycle of Hsp90 drives a molecular 'clamp' via transient dimerization of the N-terinal domains. EMBO J. 2000;19:4383–4392. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Roe SM, Ali MM, Meyer P, Vaughan CK, Panaretou B, Piper PW. The mechanism of Hsp90 regulation by the protein kinase-specific cochaperone p50cdc37. Cell. 2004;11:87–98. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cunningham CN, Krukenberg KA, Agard DA. Intra- and intermonomer interactions are required to synergistically facilitate ATP hydrolysis in Hsp90. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:21170–21178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800046200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hartson SD, Irwin AD, Shao J, Scroggins BT, Volk L, Huang W, Matts RL. p50cdc37 is a nonexclusive Hsp90 cohort which participates intimately in Hsp90-mediated folding of immature kinase molecules. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7631–7644. doi: 10.1021/bi000315r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li Y, Zhang T, Schwartz SJ, Sun D. New developments in Hsp90 inhibitors as anti-cancer therapeutics: mechanisms, clinical prespective and more potential. Drug Resist. Updat. 2009;12:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Taldone T, Gozman A, Maharaj R, Chiosis G. Targeting Hsp90: small-molecule inhibitors and their clinical development. Curr. Opin. Pharmcol. 2008;8:370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huang KH, Veal JM, Fadden RP, Rice JW, Eaves J, Strachan JP, Barabasz AF, Foley BE, Barta TE, Ma W, Silinski MA, Hu M, Partridge JM, Scott A, DuBois LG, Freed T, Steed PM, Ommen AJ, Smith ED, Hughes PF, Woodward AR, Hanson GJ, McCall WS, Markworth CJ, Hinkley L, Jenks M, Geng L, Lewis M, Otto J, Pronk B, Verleysen K, Hall SE. Discovery of novel 2-aminobenzamide inhibitors of heat shock protein 90 as potent, selective and orally active antitumor agents. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:4288–4305. doi: 10.1021/jm900230j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Koga F, Kihara K, Neckers L. Inhibition of cancer invasion and metastasis by targeting the molecular chaperone heat-shock protein 90. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:797–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chiosis G, Lopes EC, Solit D. Heat shock protein-90 inhibitors: a chronicle from geldanamycin to today's agents. Curr. Opin Investig. Drugs. 2006;7:534–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schmitt E, Gehrmann M, Brunet M, Multhoff G, Garrido C. Intracellular and extracellular functions of heat shock proteins: repercussions in cancer therapy. J. Leukoc. Bio. 2007;81:15–27. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pespeni M, Hodnett M, Pittet JF. In vivo stress preconditioning. Methods. 2005;35:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shamovsky I, Nudler E. New insights into the mechanism of heat shock response activation. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:855–861. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7458-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Guettouche T, Boellmann F, Lane WS, Voellmy R. Analysis of phosphorylation of human heat shock factor 1 in cells experiencing a stress. BMC Biochem. 2005;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bagatell R, Paine-Murrieta GD, Taylor CW, Pulcini EJ, Akinaga S, Benjamin IJ, Whitesell L. Induction of a heat shock factor 1-dependent stress response alters the cytotoxic activity of Hsp90-binding agents. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:3312–3318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lu Y, Ansar S, Michaelis ML, Blagg BSJ. Neuroprotective activity and evaluation of Hsp90 inhibitors in an immortalized neuronal cell line. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:1709–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.12.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ansar S, Burlison JA, Hadden MK, Yu XM, Desino KE, Bean J, Neckers L, Audus KL, Michaelis ML, Blagg BSJ. A non-toxic Hsp90 inhibitor protects neurons from Abeta-inducted toxicity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:1984–1990. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Peterson LB, Blagg BSJ. To fold or not to fold: modulation and consequences of Hsp90 inhibition. Future Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;1:267–283. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rice JW, Veal JM, Fadden RP, Barabasz AF, Partridge JM, Barta TE, Dubois LG, Huang KH, Mabbett SR, Silinski MA, Steed PM, Hall SE. Small molecule inhibitors of Hsp90 potently affect inflammatory disease pathways and exhibit activity in models of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3765–3775. doi: 10.1002/art.24047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stephanou A, Latchman DS, Isenberg DA. The regulation of heat shock proteins and their role in systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;28:155–162. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(98)80032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chatterjee A, Black SM, Catravas JD. Endothelial nitric oxide (NO) and its pathophysiologic regulation. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2008;49:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pittet J-F, Lee H, Pespeni M, O'Mahony A, Roux J, Welch WJ. Stress-induced inhibtion of the NF-kB signaling pathway results from the insolubilization of the IkB kinase complex following its dissociation from heat shock protein 90. J. immunol. 2005;174:384–394. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Arthur JC, Lich JD, Aziz RK, Kotb M, Ting JP. Heat shock protein 90 associates with monarch-1 and regulates its ability to promote degradation of NF-kappaB-inducing kinase. J. Immunol. 2007;179:6291–6296. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Salminen A, Paimela T, Suuronen T, Kaarniranta K. Innate immunity meets with cellular stress at the IKK complex: regulation of the IKK complex by Hsp70 and Hsp90. Immunol. Lett. 2008;117:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Burlison JA, Neckers L, Smith AB, Maxwell A, Blagg BSJ. Novobiocin: redesigning a DNA gyrase inhibitor for selective inhibition of Hsp90. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:15529–15536. doi: 10.1021/ja065793p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Palermo CM, Westlake CA, Gasiewicz TA. Epigallocatechin gallate inhibits aryl hydrocarbon receptor gene transcription through an indirect mechanism involving binding to a 90 KDa heat shock protein. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5041–5052. doi: 10.1021/bi047433p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Itoh H, Ogura M, Komatsuda A, Wakui H, Miura AB, Tashima YA. novel chaperone-activity-reducing mechanism of the 90-kDa molecular chaperone Hsp90. Biochem. J. 1999;343:697–703. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Soti C, Raez A, Csermely PA. nucleotide-dependent molecular switch controls ATP binding at the C-terminal domain of Hsp90. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:7066–7075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Byrd CA, Bornmann W, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pavletich N, Rosen N, Nathan CF, Ding A. Heat shock protein 90 mediates macrophage activation by Taxol and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999;96:5645–5650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Solit DB, Basso AD, Olshen AB, Scher HI, Rosen N. Inhibition of heat shock protein 90 function down-regulates Akt kinase and sensitizes tumors to taxol. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2139–2144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nichols RL, Finland M. Novobiocin; a limited bacteriologic and clinical study of its use in forty-five patients. Antibiotic Med. Clin. Ther. 1956;2:241–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Allan RK, Mok D, Ward BK, Ratajczak T. Modulation of chaperone function and cochaperone interaction by novobiocin in C-terminal domain of Hsp90. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:7161–7171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512406200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bras GL, Radanyi C, Peyrat JF, Brion JD, Alami M, Marsaud V, Stella B, Renoir JM. New novobiocin analogues as antiproliferative agents in breast cancer cells and potential inhibitors of heat shock protein 90. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:6189–6200. doi: 10.1021/jm0707774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Burlison JA, Avila C, Vielhauer G, Lubbers DJ, Holzbeierlein J, Blagg BSJ. Development of novobiocin analogues that manifest anti-proliferative activity against several cancer cell lines. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:2130–2137. doi: 10.1021/jo702191a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Radanyi C, Bras GL, Messaoudi S, Bouclier C, Peyrat JF, Brion JD, marsaud V, Renoir JM, Alami M. Synthesis and biological activity of simplified denoviose-coumarins related to novobiocin as potent inhibitors of heat-shock protein 90 (Hsp90) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:2495–2498. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.01.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Radanyi C, Bras GL, Bouclier C, Messaoudi S, Peyrat JF, Brion JD, Alami M, Renoir JM. Tosylcyclonovobioci acids promote cleavage of the hsp90-associated cochaperone p23. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;379:514–518. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Donnelly AC, Mays JR, Burlison JA, Nelson JT, Vielhauer g, Holzbeierlein J, Blagg BSJ. The design, synthesis, and evaluation of coumarin ring derivatives of the novobiocin scaffold that exhibit antiproliferative activity. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:8901–8920. doi: 10.1021/jo801312r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Caplan AJ, Ayan AM, Wilis IM. Multiple kinases and system robustness: a link between Cdc37 and genome integrity. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:3145–3147. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.24.5147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Vaughn CK, Mollapour M, Smith JR, Truman A, Hu B, Good VM, Panaretou B, Neckers L, Clarke PA, Workman P, Piper PW, Prodromou C, Pearl LH. Hsp90-dependent activation of protein kinases is regulated by chaperone-targeted dephosphorylation of Cdc37. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:886–895. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Grammatikakis N, Lin JH, Grammatikakis A, Tsichlis PN, Cochran BH. p50cdc37 acting in concert with Hsp90 is required for Raf-1 function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:1661–1672. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Karnitz LM, Felts SJ. Regulation of the kinome: when to hold 'em and when to fold 'em. STKE. 2007;pe22:1–3. doi: 10.1126/stke.3852007pe22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Pearl LH. Hsp90 and Cdc37 - a chaperone cancer conspiracy. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2005;15:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gray PJJ, Prince T, Cheng J, Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK. Targeting the oncogene and kinome chaperone Cdc37. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:491–495. doi: 10.1038/nrc2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Smith JR, Workman P. Targeting Cdc37: an alternative, kinase-directed strategy for disruption of oncogenic chaperoning. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:362–372. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.3.7531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gray PJJ, Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK. Targeting Cdc37 inhibits multiple signaling pathways and induces growth arrest in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11942–11950. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Smith JR, Clarke PA, Billy ED, Workman P. Silencing the cochaperone Cdc37 destabilizes kinase clients and sensitizes cancer cells to Hsp90 inhibitors. Oncogene. 2008;28:157–169. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Setty AR, Sigal LH. Herbal medications commonly used in the practice of rheumatology: mechanisms of action, efficacy, and side effects. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:773–784. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sreeramulu S, Gande SL, Gobel M, Schwalbe H. Molecular mechanism of inhibition of the human protein complex Hsp90-Cdc37, a kinome chaperone-cochaperone, by triterpene celastrol. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:5853–5855. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Trott A, West JD, Klaic L, Westerheide SD, Silverman RB, Morimoto RI, Morano KA. Activation of heat shock and antioxidant responses by the natural product celastrol: transcriptional signatures of a thiol-targeted molecule. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:1104–1112. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Westerheide SD, Bosman JD, Mbadugha BN, Kawahara TL, Matsumoto G, Kim S, Gu W, Devlin JP, Silverman RB, Morimoto RI. Celastrols as inducers of the heat shock response and cytoprotection. J. Biol. Chem. 204(279):56053–56060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409267200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]