Abstract

Central cholinergic overstimulation results in prolonged seizures of status epilepticus in humans and experimental animals. Cellular mechanisms of underlying seizures caused by cholinergic stimulation remain uncertain, but enhanced glutamatergic transmission is a potential mechanism. Paraoxon, an organophosphate cholinesterase inhibitor, enhanced glutamatergic transmission on hippocampal granule cells synapses by increasing the frequency and amplitude of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) in a concentration-dependent fashion. The amplitude of mEPSCs was not increased, which suggested the possibility of enhanced action potential-dependent release. Analysis of EPSCs evoked by minimal stimulation revealed reduced failures and increased amplitude of evoked responses. The ratio of amplitudes of EPSCs evoked by paired stimuli was also altered. The effect of paraoxon on glutamatergic transmission was blocked by the muscarinic antagonist atropine and partially mimicked by carbachol. The nicotinic receptor antagonist α -bungarotoxin did not block the effects of paraoxon; however, nicotine enhanced glutamatergic transmission. These studies suggested that cholinergic overstimulation enhances glutamatergic transmission by enhancing neurotransmitter release from presynaptic terminals.

INTRODUCTION

Cholinergic over-stimulation of the CNS causes prolonged seizures in humans and in experimental animals. Inhibition of cholinesterase, the acetylcholine degrading enzyme, by organophosphate insecticides such as parathion and malathion, and more potent nerve agents such as sarin and soman, causes elevation of central acetylcholine levels (McDonough and Shih 1997). Seizures were observed in humans exposed to nerve-agent poisoning during the Iran-Iraq war and in the Tokyo subway attacks where sarin and VX were used (Nozaki et al. 1995; Okumura et al. 1996).

Stimulation of central muscarinic receptors is a well-established method for inducing prolonged seizures in experimental animals. Peripheral injection of high doses of pilocarpine lead to prolonged seizures commonly referred to as status epilepticus (Turski et al. 1989; Turski 1983). Pretreatment with lithium followed by pilocarpine injection also leads to prolonged seizures and neuropathology (Honchar et al. 1983). The cellular mechanisms underlying seizures induced by cholinergic stimulation remain unclear. Functional imaging studies in experimental animals suggest that during these seizures, limbic structures such as the amygdala, piriform cortex, entorhinal cortex, and hippocampus are activated (Clifford et al. 1987). Extensive cell damage and loss is activated in these limbic regions during seizures induced by cholinergic stimulation (Fujikawa 1996; Honchar et al. 1983).

It has been suggested that cholinergic overstimulation leads to increased glutamatergic transmission. The pattern of neuronal activation associated with seizures caused by cholinergic stimulation is similar to that observed with kainic-acid-induced seizures (Lothman and Collins 1981; Lothman et al. 1985). NMDA receptor antagonists protect against neuronal loss caused by cholinergic seizures (Fujikawa et al. 1994). Neurochemical measurements of tissue glutamate levels and extracellular glutamate levels during seizures induced by cholinergic stimulation have yielded mixed results. Tissue glutamate levels appear to be diminished, whereas extracellular glutamate levels are increased during these seizures (McDonough and Shih 1997). Some electrophysiological studies have suggested that muscarinic agonists suppress glutamate release from presynaptic terminals (de Sevilla et al. 2002). Stimulation of nicotinic receptors in the hippocampus enhances glutamate release from presynaptic terminals and enhances synaptic transmission (Alkondon and Albuquerque 2004; Gray et al. 1996; Radcliffe and Dani 1998; Sharma and Vijayaraghavan 2003). However, the effect of muscarinic stimulation or that of organophosphates and nerve agents on glutamatergic transmission in the hippocampus has not been investigated in detail.

Anticholinesterase nerve agents are restricted-use chemicals and surrogates are needed for studies in civilian laboratories. Paraoxon and its derivative parathion are commonly used as organophosphate pesticides; accidental and intentional human poisoning with these agents lead to symptoms identical to nerve agent exposure: sweating, dizziness, vomiting, diarrhea, seizures, cardiac arrest, respiratory arrest, and, in extreme cases, death (Garcia et al. 2003). In guinea pig hippocampal slices, paraoxon causes seizures similar to those caused by the nerve gas soman (Harrison et al. 2004). In this study, we studied the effects and mechanism of action of paraoxon on glutamatergic transmission in the hippocampus.

METHODS

Slice preparation

All studies were performed according to protocols approved by the University of Virginia Animal Use and Care committee. Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane before decapitation and followed by quick removal of the brain, which was sectioned to 350 μm using a Vibratome at 4°C in an oxygenated slicing solution. The solution contained the following (in mM): 120 sucrose, 65.5 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.1 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 10 d-glucose, 1 CaCl2, and 5 MgSO4. The slices were stored in oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing the following (in mM): 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 10 d-glucose, 2.5 CaCl2, and 1.3 MgSO4; osmolarity was 290–300 in the chamber. Slices were held in this chamber at room temperature (24°C) for 60 min before transfer to the recording chamber on the stage of a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). All chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless stated otherwise.

Whole cell recording

Whole cell patch-clamp recordings were performed using infrared differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) microscopy and a ×40 water-immersion objective to visually identify dentate granule cells. Slices were continuously superfused with ACSF solution saturated with 95% O2– 5% CO2 at room temperature.

Patch electrodes (final resistances, 3–6 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate glass (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) on a horizontal Flaming-Brown microelectrode puller (Model P-97, Sutter Instruments), using a three-stage pull protocol. Electrode tips were filled with a filtered internal recording solution consisting of (in mM) 117.5 CsMeSO4, 10 2-hydroxyethyl] piperazine-N-[2-ethansulfonic acid] (HEPES), 0.3 N-[and glycol-bis (a-aminoethyl ether) N,N,N,N-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 15.5 CsCl, 1.0 MgCl2, pH 7.3 (with CsOH); osmolarity was 290–300 mosM. The electrode shank contained (in mM) 4 ATP Mg2+ salt, 0.3 GTP Na+ salt, and 5 QX-314.

Neurons were voltage clamped to −60 mV for the duration of the recording, which was between 20 and 30 min. Whole cell capacitance and series resistance were compensated by 80% at 10-ms lag. Recording was performed when series resistance after compensation was ≤20 MΩ. Access resistance was monitored with a 10-ms, 10-mV test pulse once every 2 min, and if the series resistance increased by 25% at any time during the experiment, then the recording was terminated. Currents were filtered at 5 kHz, digitized using a Digidata 1322 digitizer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), and acquired using Clampex 8.2 software (Molecular Devices).

Spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) were recorded from granule cells after blocking the GABAA receptor with the antagonist picrotoxin (50 μM). In preliminary experiments, a combination of 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxalene-2,3-dione (CNQX) and 2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV) blocked all EPSCs. Miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) were recorded by blocking action potentials with 1 μM tetrodotoxin (TTX, Alomone labs, Jerusalem, Israel). Evoked EPSCs (eEPSCs) were evoked by minimally stimulating the perforant pathway by means of a glass electrode filled with ACSF. Extracellular stimulus pulses of 2- to 8-V, 10-μs duration, and 0.07-Hz frequency were delivered using a stimulus isolation unit driven by a TTL timer and synchronized by Clampex 8.2 software (Molecular Devices). eEPSCs were caught with a trigger signal and analyzed if they were not contaminated by spontaneous events. The amplitude of eEPSCs was measured in cells before and after drug application. The stimulation was reduced until 20–25% of stimulations failed to produce a response. Paraoxon (90%) solution in DMSO was diluted in ACSF 1:30 to make 10 mM stock solution. It was further diluted with ACSF prior to each experiment. Carbachol and nicotine were diluted in ACSF. All drugs were bath-applied by a peristaltic pump.

Data analysis

The digitized current traces were analyzed with MiniAnalysis (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA). To detect sEPSCs and mEPSCs, a detection threshold three times root mean square (RMS) of baseline noise was used. After detection, frequency and peak amplitude of EPSCs were analyzed for individual neurons. Each detected event in the 10- to 30-min recording was visually inspected to remove false detections.

The dose response curve for paraoxon was generated using a biphasic sigmoidal function in Graphpad Prism software

| (1) |

where the Bottom (100); Top (300) and Frac (10) are constants.

The EPSC amplitudes were fit using Origin software (Northampton, MA) to the following equation for Gaussian distributions

| (2) |

where y0 is the baseline offset, A is the total area under the curve from the baseline, x0 is the center of the peak, w is 2 “σ,” ∼0.849 the width of the peak at half height. Recordings selected for Gaussian fitting consisted of ≥1,500 ± 200 individual EPSC events without any evidence of rundown of amplitudes or change in access resistance.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test was used to compare amplitudes and interevent intervals for continuously recorded EPSCs. This test is based on the empirical distribution function (ECDF). Given N ordered data points Y1, Y2, YN, the ECDF is defined as

| (3) |

where n(i) is the number of points less than Yi and the Yi are ordered from smallest to largest. This is a step function that increases by 1/N at the value of each ordered data point.

Event frequency and amplitudes were compared using a Student's t-test (GraphPad Prizm, Mountain View, CA). Data values were expressed as the means ± SE unless noted otherwise. The P values represent the results of Student's t-test analysis, with P < 0.05 indicating the level of significance. Drug application data were analyzed using a paired t-test.

RESULTS

Paraoxon increased frequency and amplitudes of sEPSCs

We investigated whether paraoxon could alter glutamatergic synaptic transmission by studying sEPSCs, mEPSCs, and eEPSCs recorded from dentate granule cells in sagittal hippocampal slices. Granule cells had a resting membrane potential of −65 ± 2 mV (n = 161). At baseline, sEPSCs occurred at a frequency 1.15 ± 0.22 Hz with mean amplitude of 15.22 ± 1.09 pA. We expected to collect 300–500 events in each 5-min epoch.

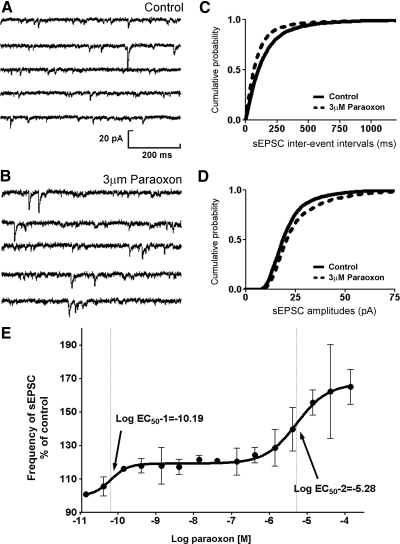

After recording sEPSCs for 10 min, 3 μM paraoxon was bath-applied to a slice. A typical recording of sEPSCs before and after application of paraoxon is shown in Fig. 1, A and B. Paraoxon (3 μM) increased the mean frequency of sEPSCs in the slice by 47.6 ± 22% (n = 8; Table 1; Fig. 1, A–C). We pooled sEPSC interevent interval data from eight cells and generated cumulative frequency plots, which were analyzed by the K-S test. Paraoxon caused a significant left shift in interevent intervals (Fig. 2C). Also paraoxon enhanced the mean amplitudes of sEPSCs by 53.4 ± 8.62% (Table 1) and caused a right shift of the cumulative frequency plot of sEPSC amplitudes (Fig. 1D). Paraoxon did not significantly alter the rise time and decay time of sEPSCs (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Paraoxon enhanced the frequency and amplitude of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs). A and B: representative sEPSC recordings obtained from dentate granule cells before (control) and after application of 3 μM paraoxon (PXN). C and D: cumulative probability plots of sEPSC frequency (C) and amplitude (D) obtained by pooling data from 8 neurons before (—) and after (- - -) application of paraoxon. E: relationship of paraoxon concentration to sEPSC frequency. The ordinate depicts frequency of sEPSCs in the presence of paraoxon expressed as the percent fraction of that before paraoxon application. •, mean frequency; 3–8 neurons were tested at each concentration. The solid line, the best fit of the concentration response relationship to a biphasic sigmoidal function.

Table 1.

Impact of Cholinergic agonists on sEPSC parameters

| Frequency, Hz | Peak Amplitude, pA | Rise Time (10–90%), ms | Decay Time (90–10%), ms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (8) | 1.15 ± 0.22 | 15.22 ± 1.09 | 4.92 ± 0.48 | 25.89 ± 4.1 |

| Paraoxon (3 μM) | 1.70 ± 0.40* | 23.35 ± 0.21* | 4.74 ± 0.72 | 29.44 ± 5.86 |

| Baseline (7) | 0.75 ± 0.19 | 16.16 ± 0.19 | 2.90 ± 0.40 | 10.6 ± 1.30 |

| Carbachol (50 μM) | 1.14 ± 0.26** | 15.30 ± 0.14** | 3.03 ± 0.34 | 10.72 ± 1.28 |

| Baseline (5) | 1.49 ± 0.37 | 14.5 ± 2.74 | 3.38 ± 0.6 | 17.96 ± 5.90 |

| Nicotine (1 μM) | 1.84 ± 0.36* | 15.55 ± 2.76* | 3.43 ± 0.46 | 20.36 ± 7.71 |

| Baseline (4) | 0.58 ± 0.11 | 15.43 ± 1.89 | 2.31 ± 0.27 | 10.97 ± 1.01 |

| Ambenonium (250 μM) | 1.08 ± 0.31* | 15.93 ± 2.02 | 2.26 ± 0.39 | 11.14 ± 1.63 |

| Baseline (5) | 0.69 ± 0.10 | 14.23 ± 1.73 | 3.54 ± 0.75 | 11.70 ± 0.43 |

| Ambenonium (500 μM) | 1.61 ± 0.70*** | 17.50 ± 1.80 | 2.49 ± 0.44 | 11.82 ± 2.10 |

Values are means ± SD. n are in parentheses. sEPSC, spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic potential.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.005;

P < 0.001.

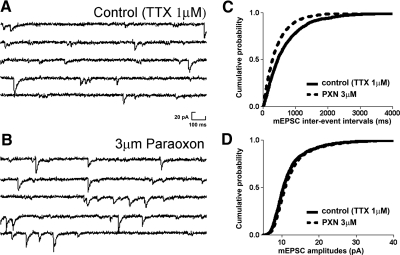

Fig. 2.

Paraoxon enhances the frequency of action-potential-independent miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs). A and B: representative mEPSC recordings obtained from dentate granule cells before (control) and after application of paraoxon. C and D: cumulative probability plots of mEPSC frequency (C) and amplitude (D) obtained by pooling data from neurons before (—) and after (- - -) application of paraoxon.

To fully characterize the dependence of sEPSC frequency on paraoxon concentration, we tested 15 different concentrations of paraoxon (n = 44) ranging from 0.01 nM to 30 μM. Paraoxon was found to increase sEPSC frequency in a concentration-dependent manner. This effect can be described by means of a biphasic sigmoidal curve (Fig. 1E). The EC50 and Hill slope values were derived from the Eq. 1 that best fit the observed data by the least-square fit method. The EC50 (1) of the first phase of best fit was 0.3 nM and the Hill coefficient (1) was 1.76. The EC50 (2) of the second phase was near 3 μM with a Hill coefficient (2) of 1.21.

The effects of paraoxon could not be reversed by washing out the drug. Therefore we tested whether ambenonium, a reversible high-affinity cholinesterase inhibitor, could mimic the effects of paraoxon on increasing the frequency of sEPSCs. Application of ambenonium (500 nM) significantly increased (133% increase, P < 0.001, n = 5) the sEPSC frequency (from 0.69 ± 0.1 to 1.61 ± 0.7 Hz), which returned to baseline levels (0.60 ± 0.1 Hz) on washout of the drug from the bath (Table 1). A lower concentration of ambenonium (250 nM) also reversibly enhanced the frequency of sEPSCs by 86% (from 0.58 ± 0.11 to 1.08 ± 0.31 Hz, P < 0.05, n = 4; Table 1).

Paraoxon effect on mEPSCs

Because sEPSCs consist of action potential-dependent and action potential-independent events (mEPSCs), we tested whether paraoxon enhanced the amplitude of mEPSCs. To test whether paraoxon increased the action potential-independent release of glutamate, 1 μM tetrodotoxin was added to the external solution to record mEPSCs. After recording mEPSCs from granule cells for 5 min, 3 μM paraoxon was applied (Fig. 2, A and B). The frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs both before and after application of paraoxon were then compared. Paraoxon increased the frequency of mEPSCs in five cells from 1.08 ± 0.08 to 1.32 ± 0.34 Hz (P < 0.05; n = 5; Fig. 2, B and C). In contrast, application of paraoxon did not significantly change the mean amplitudes of mEPSCs (11.56 ± 1.19 vs. 12.00 ± 1.16 pA; P > 0.05; n = 5; Fig. 2, B and D). Paraoxon did not alter the rise time of mEPSCs (2.80 ± 0.11 vs. 2.78 ± 0.11 ms) and decay time (13.70 ± 0.56 vs. 12.91 ± 0.39 ms).

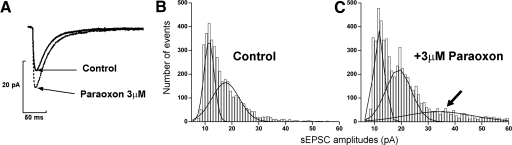

Paraoxon altered glutamate release

One interpretation of the finding that paraoxon increased sEPSC amplitude (Fig. 3A) but not mEPSC amplitude is that the total amount of neurotransmitter released in response to a single action potential was increased or the number of release sites activated per action potential was increased. Amplitude distribution histograms have been used to analyze changes in presynaptic release mechanisms (Edwards et al. 1990). We therefore investigated whether the distributions of sEPSC amplitudes were different before and after application of paraoxon by resolving the distribution of sEPSCs into multiple peaks. The amplitudes of sEPSCs recorded from control neurons (n = 8) were pooled and fitted to an equation for multiple Gaussians using Origin software. The amplitude distribution histogram could be best fit to a sum of 2 Gaussians. The peaks of the Gaussians were centered at 11.48 and 17.6 pA (Fig. 3B). These Gaussians comprised 43.59 and 56.41% of the overall population of sEPSCs. The amplitude distribution histogram of sEPSCs recorded after application of paraoxon was best fit to 3 Gaussians (Fig. 3C), centered at 11.68, 18.96, and at 34.02 pA, and corresponding overall populations were 32.63, 44.58, and 22.79%, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Presynaptic changes underlie paraoxon-induced increase in sEPSC amplitude. A: representative trace of averaged sEPSCs before (—) and after (- - -) application of paraoxon. B and C: amplitude distribution histograms obtained from sEPSCs recorded before (B) and after (C) application of paraoxon. Note the appearance of an additional peak of larger sEPSC after paraoxon application.

This analysis suggested that paraoxon caused the appearance of a new, larger peak in the amplitude distribution histogram. Paraoxon did not cause a shift in the location of the first peak of the amplitude distribution histogram, and it did not cause separation between subsequent peaks to change. Combination of these findings was consistent with increased neurotransmitter release and argued against changes in postsynaptic receptors resulting in increased sEPSC amplitude. These studies on sEPSCs were carried out in combined entorhinal cortex-hippocampal slices; therefore cell bodies of both input neurons were intact. Increased frequency of action potentials in presynaptic neurons could explain some observed changes in sEPSCs. To control the contribution of presynaptic neurons, we stimulated the perforant path, the afferent fibers from entorhinal cortex, to test whether eEPSCs were affected by paraoxon.

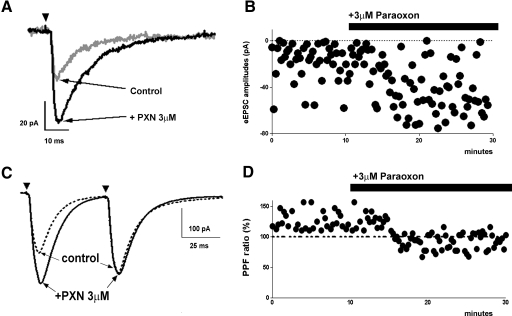

A minimally effective stimulation pulse (0.2 V; 10 μs) was applied to the perforant pathway by means of a glass electrode filled with ASCF, and evoked responses were recorded. During baseline recording from a cell, 44 stimuli were delivered and 10 failed to evoke a response (22.7% failure rate; see Fig. 4A). After application of paraoxon, 60 stimuli were delivered, and there were 11 failures (18.7%). A decrease in failure rate (total number of failures/stimuli of trials; N0 /N) was evident in all those cells that showed an increase in the eEPSC amplitude following paraoxon application. The amplitudes of minimal stimulus eEPSCs were measured in cells before and after application of paraoxon. Application of 3 μM paraoxon increased the mean amplitude of eEPSCs from 23.20 ± 1.43 to 35.93 ± 1.58 pA (P < 0.05; n = 7; Fig. 4B). Paraoxon also increased decay time from 8.07 ± 1.96 to 14.52 ± 2.68 ms; (P < 0.05; n = 7) but did not alter rise time (1.37 ± 0.31 vs. 1.60 ± 0.30 ms; P > 0.05; n = 7). These observations support the hypothesis that paraoxon acts at presynaptic sites and increases action potential-dependent release.

Fig. 4.

Paraoxon enhanced the amplitude of electrically evoked EPSCs (eEPSCs). A: representative averaged trace of eEPSCs recorded before (gray trace) and after (black trace) application of paraoxon. Arrowheads in this and C indicate the application of stimulus. B: amplitude of eEPSCs recorded from a cell before and after paraoxon application; failure of response is represented as amplitude of 0 pA. Note reduced failures and increased amplitude of eEPSCs C and D: paraoxon diminished paired pulse facilitation (PPF). C: representative averaged trace of eEPSCs obtained by paired stimuli before and after application of paraoxon. D: application of paraoxon diminished the rate of PPF. The dotted lines at 100% indicate the normalized amplitude of eEPSCs evoked by the 1st stimuli.

To further confirm that paraoxon enhanced EPSCs by presynaptic mechanisms, paired stimuli were delivered to evoke EPSCs. Figure 4C shows representative averaged pairs of eEPSCs generated at 50-ms intervals using a half-maximal stimulus intensity (the mean of maximal eEPSC was 550 ± 96 pA). For the eight cells, the mean amplitudes of the first peak eEPSC at baseline was 166.8 ± 24.06 pA, and of the second peak it was 203.1 ± 29.17 pA. The paired-pulse facilitation at baseline was 123.1 ± 4.59%, and after application of PXN, it was 90.84 ± 4.63%. Thus paraoxon diminished the degree of paired pulse facilitation by 26.5 ± 5.52% (n = 8; P < 0.001; Fig. 4D).

Nicotinic enhancement of EPSCs

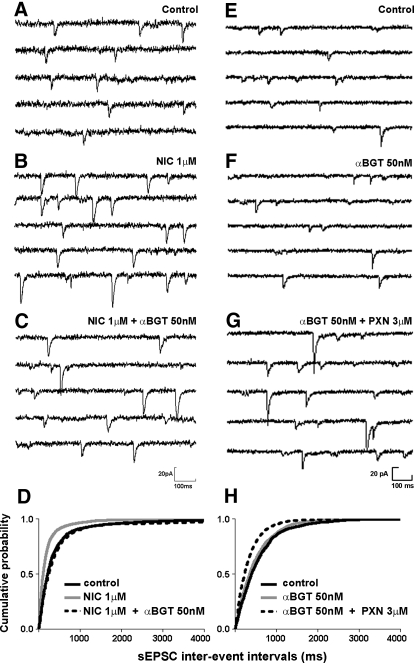

Previous studies demonstrate that paraoxon enhances synaptic transmission and that this enhancement could be mediated by muscarinic receptors, nicotinic receptors, or other mechanisms independent of these receptor subtypes. To determine the type of cholinergic receptor mediating the effect of paraoxon, we examined nicotinic and muscarinic agonists and antagonists. We first tested whether the nicotinic receptor agonist nicotine mimicked the action of paraoxon. Nicotine (1 μM) increased the frequency of sEPSCs (Fig. 5, A, B, and D) and their amplitudes (Table 1). Nicotine did not significantly change the rise and decay time constant of sEPSCs (each comparison P > 0.05; n = 5).

Fig. 5.

Paraoxon-induced increase in sEPSC was not blocked by a nicotinic receptor antagonist. A and B: representative sEPSC recordings obtained from dentate granule cells before (A) and after (B) application of nicotine (NIC 1 μM). C: sEPSCs from the same cell after co-application of nicotine and the nicotinic receptor antagonist, α-bungarotoxin (αBGT 50 nM). D: cumulative probability histogram of sEPSC frequency before (black solid line) and after (gray solid line) application of nicotine followed by co-application of nicotine and α-bungarotoxin (dotted line). E and F: representative sEPSC recordings obtained before (E) and after (F) application of α-bungarotoxin (50 nM). G: sEPSCs from the same cell after co-application of α-bungarotoxin and paraoxon. H: cumulative probability histogram of sEPSC frequency before (black solid line) and after application of α-bungarotoxin (gray solid line) followed by co-application of α-bungarotoxin and paraoxon (dotted line) indicates that α-bungarotoxin did not prevent paraoxon-induced increase in sEPSC frequency.

Increased sEPSC frequency caused by nicotine was completely reversed by 50 nM α-bungarotoxin (αBGT), which binds to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with high affinity (Fig. 5, A–D). Preapplication of αBGT prevented nicotine-induced increase in frequency and amplitudes of sEPSCs (Table 2). However, preapplication of αBGT did not prevent increase in sEPSC frequency caused by the application of paraoxon (Table 2; Fig. 5, E–H). Additionally, when αBGT was applied after application of paraoxon, changes in amplitudes and frequency of sEPSCs caused by paraoxon were not reversed (Table 2). Frequency and amplitudes of mEPSCs did not change after application of nicotine at 1 μM (P > 0.05; n = 4 and P > 0.05; n = 4, respectively).

Table 2.

Impact of paraoxon, carbachol, and nicotine

| Frequency, Hz | Peak Amplitude, pA | |

|---|---|---|

| A. Muscarinic Receptors | ||

| Baseline (4) | 1.27 ± 0.17 | 14.61 ± 2.62 |

| Atropine | 1.072 ± 0.23 | 14.74 ± 2.47 |

| Atropine + carbachol | 1.19 ± 0.33 | 14.51 ± 0.85 |

| Baseline (5) | 0.54 ± 0.14 | 13.85 ± 1.22 |

| Atropine | 0.46 ± 0.17 | 13.62 ± 1.62 |

| Atropine + paraoxon | 0.55 ± 0.20 | 14.79 ± 1.44 |

| Baseline (4) | 0.91 ± 0.14 | 13.70 ± 2.21 |

| Carbachol | 1.49 ± 0.43* | 17.76 ± 1.69 |

| Carbachol + atropine | 1.15 ± 0.48 | 15.45 ± 1.08 |

| Baseline (4) | 1.18 ± 0.32 | 13.77 ± 1.60 |

| Paraoxon | 1.84 ± 0.60* | 15.01 ± 2.03* |

| Paraoxon + atropine | 1.21 ± 0.36 | 14.69 ± 1.57 |

| B. Nicotinic receptors | ||

| Baseline (5) | 1.01 ± 0.34 | 18.63 ± 1.93 |

| α-bungarotoxin | 1.17 ± 0.22 | 15.65 ± 3.08 |

| α-bungarotoxin + nicotine | 1.28 ± 0.32 | 15.68 ± 2.84 |

| Baseline (4) | 1.21 ± 0.16 | 12.049 ± 0.09 |

| α-bungarotoxin | 1.31 ± 0.18 | 12.04 ± 0.10 |

| α-bungarotoxin + paraoxon | 1.69 ± 0.15* | 11.88 ± 0.10 |

| Baseline (n = 5) | 1.49 ± 0.38 | 14.59 ± 2.74 |

| Nicotine | 1.73 ± 0.42* | 15.55 ± 2.76* |

| Nicotine + α-bungarotoxin | 1.51 ± 0.45 | 14.75 ± 1.74 |

| Baseline (4) | 1.59 ± 0.19 | 11.31 ± 0.09 |

| Paraoxon | 2.36 ± 0.33** | 12.08 ± 0.27* |

| Paraoxon + α-bungarotoxin | 2.28 ± 0.30* | 12.24 ± 0.42* |

The impact of the cholinergic agonists paraoxon, carbachol, and nicotine coapplied with antagonists before and after application of antagonists of muscarinic or nicotinic receptors on sEPSXC frequency and amplitude.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.005 using repeated measures ANOVA test.

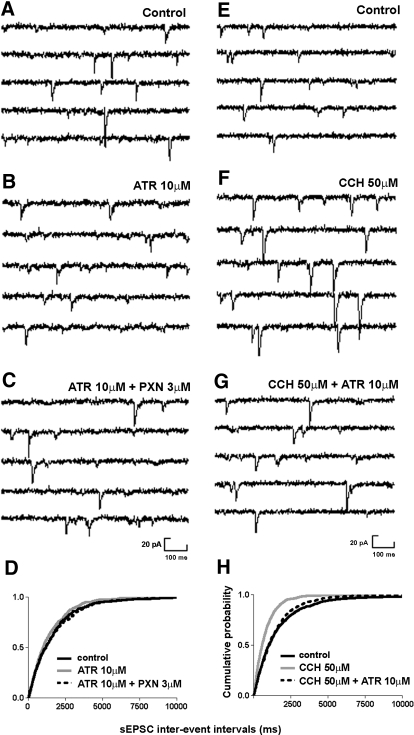

Muscarinic enhancement of EPSCs

We tested whether blocking muscarinic receptors selectively would prevent the action of the paraoxon. Atropine, a muscarinic antagonist, was applied after a 5-min recording of sEPSCs. Paraoxon was then applied in the presence of atropine. Atropine did not alter sEPSC frequency or amplitude (Fig. 6, A and B, and Table 2). When paraoxon was applied in the presence of atropine, it did not enhance sEPSC frequency or amplitude (Fig. 6, A–D, and Table 2). Therefore the muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine prevented paraoxon-induced increase in sEPSC frequency and amplitude.

Fig. 6.

The muscarinic antagonist atropine blocked the action of paraoxon on sEPSC frequency. A–C: representative traces of sEPSC recordings obtained before (A) and after (B) application of atropine (10 μM) followed by co-application of atropine and paraoxon (C). D: cumulative probability histogram of sEPSC frequency before (black solid line), after application of atropine (gray solid line), and after (dotted line) co-application of atropine and paraoxon reveals that atropine prevented paraoxon-induced increase in sEPSC frequency. D–F: representative sEPSC recordings obtained before (E) and after (F) application of carbachol (50 μM) followed by co-application of carbachol and atropine (10 μM, G). H: cumulative probability histogram of sEPSC frequency before (solid line), after application of carbachol (gray solid line), and after (dotted line) co-application of carbachol and atropine reveals that atropine reversed carbachol-induced increase in sEPSC frequency.

Although atropine blocked the action of paraoxon on sEPSCs, carbachol only partially mimicked the effects of paraoxon. Carbachol (50 μM) also significantly increased sEPSC frequency, which was reversed by atropine (Table 1; Fig. 6, E–G). Carbachol decreased interevent intervals as demonstrated by a cumulative probability plot of data from eight neurons (Fig. 6H). Unlike paraoxon, carbachol caused a reduction of sEPSC amplitude (Table 1). Carbachol did not change frequency (P > 0.05; n = 5) or amplitudes (P > 0.05; n = 5) of mEPSCs. Carbachol did not significantly change the rise time and decay time constant of sEPSCs (Table 1).

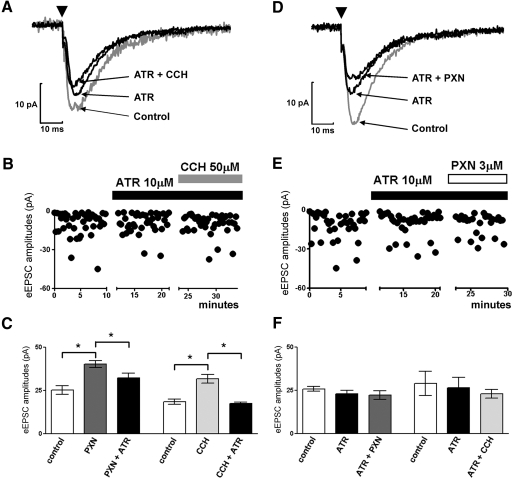

The effect of muscarinic receptor blockade on EPSCs evoked by minimal stimulation was then studied. The application of the muscarinic antagonist atropine reduced eEPSC amplitudes from 27.44 ± 3.37 to 24.80 ± 2.98 pA (Fig. 7, A–C) and increased the failure rate from 7.2 to 12.2%. Carbachol application could not overcome the effect of atropine (Fig. 7, A–C). Similarly, application of paraoxon in the presence of atropine did not change eEPSC amplitudes (Fig. 7, D–F) and did not increase the failure rate (15.9%). Moreover, when atropine was applied after paraoxon, it reversed paraoxon action on eEPSC amplitudes from 40.28 ± 2.07 to 32.40 ± 2.54 pA (ANOVA test P < 0.01*; n = 4; Fig. 7F).

Fig. 7.

Atropine blocked both carbachol- and paraoxon-induced increase in eEPSC amplitudes. A: representative average trace of eEPSC at baseline (gray) followed by application of atropine and co-application of atropine and carbachol. Arrowheads in this and D indicate the application of stimulus. B: representative time-scaled amplitude of peak eEPSCs recorded from a cell before and after application of atropine followed by co-application with carbachol. C: quantification of eEPSC amplitudes demonstrated that carbachol- or paraoxon-induced increase in eEPSC amplitudes was reversed by co-application of atropine. D: the averaged eEPSC trace at baseline (gray) followed by application of atropine and co-application of atropine and paraoxon. E: representative time scaled amplitude of peak eEPSCs recorded from a cell before and after application of atropine and then followed by co-application with carbachol or paraoxon. F: quantification of eEPSC amplitudes demonstrated that preapplication of atropine occluded the effect of carbachol and paraoxon on eEPSC amplitudes.

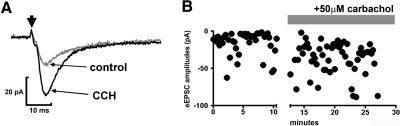

We then tested whether, like paraoxon, muscarinic agonists acted on EPSCs evoked with minimal stimulation. Carbachol increased mean amplitudes of eEPSCs from 18.43 ± 1.50 to 31.81 ± 2.60 pA (P < 0.001*; n = 7; Fig. 8, A and B) and reduced the failure rate of evoked responses from 13.3 to 8% (B).

Fig. 8.

Carbachol enhanced the amplitude of eEPSCs. A: representative averaged eEPSC trace before (gray trace) and after (black trace) application of carbachol (CCH). Arrow indicates the application of stimulus. B: amplitude of eEPSCs recorded from a cell before and after carbachol application; failure of response is represented as amplitude of 0 pA. Note reduced failures and increased amplitude of eEPSCs after application of carbachol.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated that the cholinesterase inhibitor paraoxon enhanced glutamatergic transmission on hippocampal granule cells synapses by increasing the frequency and amplitudes of sEPSCs, principally through presynaptic mechanisms. Furthermore the effect of paraoxon on glutamatergic transmission was mediated in part by muscarinic receptors. Similarly, muscarinic receptor agonists were found to enhance excitatory neurotransmission.

Paraoxon increased EPSC amplitude by altered presynaptic mechanisms

The results of this study suggest that cholinergic stimulation by paraoxon increased both action-potential-dependent and-independent neurotransmitter release from presynaptic terminals. However, neither paraoxon nor carbachol altered the amplitude of mEPSCs. Further evidence for a presynaptic locus of action is from our observation that neither paraoxon nor carbachol altered the location of the first peak or separation between peaks of the amplitude distribution histograms (Edwards et al. 1990). The amplitude and frequency of sEPSCs was increased by paraoxon. An obvious explanation for increased frequency of sEPSCs recorded from dentate granule cells would be increased action potentials in the presynaptic neurons in the entorhinal cortex and dentate hilus, especially because we had studied combined entorhinal cortex-hippocampus slices. Major excitatory input to dentate granule cells is provided by layer II and III of the entorhinal cortex (Steward and Scoville 1976). Muscarinic stimulation causes depolarization and oscillatory activity in layer II and V neurons in the entorhinal cortex (Klink and Alonso 1997a,b). It is therefore likely that the increased sEPSC frequency observed was in part due to an increased number of action potentials from the entorhinal cortex neurons. The muscarinic antagonist atropine is also known to reduce action potential bursting evoked by organophosphates in the CA1 region of hippocampal slices (Harrison et al. 2004). Indeed, examination of the effect on paraoxon on the firing rate of neurons indicated that the drug enhanced neuronal firing rate. Alternately, increased amplitude of sEPSC could also be a result of the unmasking of previously undetected synapses. However, additional mechanism might be operational. Presynaptic mechanisms such as an increased probability of release (per action potential) maybe an alternate explanation for the increase in sEPSC amplitude. Three lines of evidence further suggested that paraoxon acted on these presynaptic mechanisms: it enhanced the amplitude of evoked EPSCs, reduced their failure rate, and changed the response to paired-pulse stimulation. Increased amplitude of sEPSCs could be due to postsynaptic mechanisms such as an increased number of postsynaptic receptors as reported recently. However, mEPSC amplitude and other measures of action-potential-independent release were not affected in our studies.

Modulation of transmitter release by muscarinic activation

Application of selective agonists and antagonists of nicotinic or muscarinic receptors suggest that muscarinic receptors are involved in the process of modulation of glutamatergic transmission by paraoxon. The action of paraoxon on sEPSCs was in part mediated by muscarinic receptor activation because carbachol had a similar action and atropine blocked this effect. Interestingly, carbachol partially mimicked the effects of paraoxon on sEPSC properties because carbachol diminished sEPSC amplitude in contrast to that of paraoxon, perhaps due to the rapid desensitization of nicotinic receptors following carbachol application. Nevertheless, the occlusion of paraoxon actions by atropine confirms muscarinic involvement in the actions of paraoxon. We also observed that carbachol application did not alter sEPSC amplitude but increased the amplitude of eEPSCs. We believe that rapid desensitization of nicotinic receptors by carbachol could have masked the drugs actions on muscarinic receptor-mediated EPSC components; more so because sEPSC comprises both action-potential-dependent and -independent events. In contrast, evoked responses generated by electrical stimulation of presynaptic afferents are comprised solely of summated action-potential-dependent EPSCs, thereby more accurately demonstrating the effects of carbachol. Activation of muscarinic receptors can modulate neurotransmitter release by inhibition of calcium or potassium channels. Activation of muscarinic receptors modulates both calcium and M-type potassium currents in sympathetic ganglia (Brown and Adams 1980; Selyanko et al. 2000). Increased neurotransmitter release in response to paraoxon and muscarinic stimulation is unlikely to be due to inhibition of N- or L-type Ca2+ channels because this action would diminish neurotransmitter release. In contrast, inhibition of M-current is likely to enhance neurotransmitter release by broadening action potentials. The molecular pathways involved in the inhibition of L- and N-type Ca2+ channels and M-type potassium channels are distinct, and independent modulation of these channels is possible (Liu et al. 2006).

Molecular cloning of various genes for K+ channels, identification of channel gene mutations that lead to human benign familial neonatal convulsions, and reconstitution studies suggest that M current is mediated by KCNQ2/KCNQ3 channels (Cooper and Jan 2003; Shapiro et al. 2000). These channels activate and deactivate at sub threshold membrane potentials and modulate burst generation and after-hyperpolarization in pyramidal neurons (Yue and Yaari 2004). These channels appear to be present on the initial segment of the axon and on the presynaptic terminals of hippocampal neurons. It was recently proposed that these channels could modulate neuronal excitability and transmitter release (Vervaeke et al. 2006). Future studies with M current channel openers and antagonists could test whether muscarinic actions on glutamate release are mediated in part by these channels.

Some previous studies have suggested that muscarinic receptor stimulation inhibits glutamate release from presynaptic terminals. In one study of the Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapse, the cholinergic agonist carbamylcholine increased the failure rate without changes in the EPSC amplitude (de Sevilla et al. 2002). The suppression of evoked responses was insensitive to manipulations increasing the probability of release, such as paired-pulse facilitation, increases in temperature, and increases in the extracellular Ca2+:Mg2+ ratio. The authors suggested that muscarinic receptors diminished the release probability at the Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses. The differences in conclusions of this study and ours may be due to the difference in synapses studied (Schaffer collateral-CA1 vs. perforant path-granule cell) or varied methods used to stimulate afferent inputs and to record EPSCs.

In addition to actions via muscarinic receptors, paraoxon appears to have a direct action on glutamate release from the presynaptic terminal. Paraoxon increased the frequency of action potential-independent mEPSCs recorded from dentate granule cells. However, carbachol did not increase the frequency of mEPSCs. Furthermore, though paraoxon increased the amplitude of sEPSCs, whereas neither carbachol nor ambinomium increased sEPSC amplitudes. Further, the muscarinic antagonist atropine only partially blocked the effect of paraoxon on evoked and spontaneous EPSCs. This action of paraoxon could represent direct, cholinesterase-independent action. Indeed, cholinesterase inhibition-independent stimulation of neurotransmitter release has been described previously (Rocha et al. 1996).

Paraoxon-induced seizures

Cholinesterase inhibitors and muscarinic agonists such as pilocarpine have been long known to cause prolonged, persistent seizures, but there are few studies exploring the mechanisms of seizure induction by these agents. There is basal release of acetylcholine in the hippocampus. Cholinesterase inhibitors increase ambient acetylcholine levels in the brain rapidly by inhibiting its breakdown (Shi and McDonoug 1997). These studies report a threefold increase in ambient acetylcholine levels in the cortex after administration of cholinesterase inhibitors. Microdialysis probes placed in the dorsal hippocampus near the dentate gyrus collect ∼0.2–0.4 pmol of acetylcholine in 20 min. These levels are increased during exploration and learning and subject to modulation under physiological and pathological conditions (Jope and Morrisett 1986; Jope et al. 1987; Mitsushima et al. 2009). Increased levels of acetylcholine acting via muscarinic receptors could in turn strengthen postsynaptic excitatory transmission by increased the surface expression of AMPA receptors on dendritic spines (de Sevilla et al. 2008).

The current study suggests increased glutamate release from presynaptic terminals as a mechanism for inducing prolonged seizures and status epilepticus. Seizures consist of recurrent synchronized bursting of neurons. Conditions for generating these bursts have been studied extensively in vitro with hippocampal slice preparations and in cultures. Results of these experiments have been simulated in computer models of neuronal networks, which suggested that seizure-like events arise from two basic mechanisms: sustained dendritic depolarization and increased axonal and presynaptic terminal excitability (Traub et al. 1984, 1996). The present study provides evidence that cholinergic and muscarinic stimulation cause increased presynaptic activity.

The increased glutamate release demonstrated in the current study is similar to that reported in the in vitro low magnesium-induced recurrent bursting model (Mangan and Kapur 2004; Mody et al. 1987). Other chemicals that cause focal seizures in experimental animals and humans appear to act via other mechanisms: GABAA receptor antagonism by drugs such as penicillin, pentylenetetrazol, and bicuculline, and glutamate receptor activators by drugs such as kainic acid, homocysteine, and NMDA (Velisek 2006).

In summary, these studies demonstrate that the organophosphate paraoxon causes increased excitatory neurotransmitter release by a combination of increased presynaptic firing and increased vesicular release at presynaptic terminals via the activation of muscarinic receptors, and a direct action that may contribute to generating seizures.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grants RO1 NS-040337 and UO1 NS-58204.

REFERENCES

- Alkondon M, Albuquerque EX. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes and their function in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex. Prog Brain Res 145: 109–120, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Adams PR. Muscarinic suppression of a novel voltage-sensitive K+ current in a vertebrate neurone. Nature 283: 673–676, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford DB, Olney JW, Maniotis A, Collins RC, Zorumski CF. The functional anatomy and pathology of lithium-pilocarpine and high-dose pilocarpine seizures. Neuroscience 23: 953–968, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper EC, Jan LY. M-channels: neurological diseases, neuromodulation, and drug development. Arch Neurol 60: 496–500, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sevilla DF, Cabezas C, de Prada ANO, Sanchez-Jimenez A, Buno W. Selective muscarinic regulation of functional glutamatergic Schaffer collateral synapses in rat CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Physiol 545: 51–63, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sevilla DF, Nunez A, Borde M, Malinow R, Buno W. Cholinergic-mediated IP3-receptor activation induces long-lasting synaptic enhancement in CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 28: 1469–1478, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FA, Konnerth A, Sakmann B. Quantal analysis of inhibitory synaptic transmission in the dentate gyrus of rat hippocampal slices: a patch-clamp study. J Physiol 430: 213–249, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa DG. The temporal evolution of neuronal damage from pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Brain Res 725: 11–22, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa DG, Daniels AH, Kim JS. The competitive NMDA receptor antagonist CGP 40116 protects against status epilepticus-induced neuronal damage. Epilepsy Res 17: 207–219, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia SJ, Abu-Qare AW, Meeker-O'Connell WA, Borton AJ, Abou-Donia MB. Methyl parathion: a review of health effects. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 6: 185–210, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray R, Rajan AS, Radcliffe KA, Yakehiro M, Dani JA. Hippocampal synaptic transmission enhanced by low concentrations of nicotine. Nature 383: 713–716, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PK, Sheridan RD, Green AC, Scott IR, Tattersall JE. A guinea pig hippocampal slice model of organophosphate-induced seizure activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310: 678–686, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honchar MP, Olney JW, Sherman WR. Systemic cholinergic agents induce seizures and brain damage in lithium-treated rats. Science 220: 323–325, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jope RS, Morrisett RA. Neurochemical consequences of status epilepticus induced in rats by coadministration of lithium and pilocarpine. Exp Neurol 93: 404–414, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jope RS, Simonato M, Lally K. Acetylcholine content in rat brain is elevated by status epilepticus induced by lithium and pilocarpine. J Neurochem 49: 944–951, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klink R, Alonso A. Ionic mechanisms of muscarinic depolarization in entorhinal cortex layer II neurons. J Neurophysiol 77: 1829–1843, 1997a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klink R, Alonso A. Muscarinic modulation of the oscillatory and repetitive firing properties of entorhinal cortex layer II neurons. J Neurophysiol 77: 1813–1828, 1997b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Zhao R, Bai Y, Stanish LF, Evans JE, Sanderson MJ, Bonventre JV, Rittenhouse AR. M1 muscarinic receptors inhibit L-type Ca2+ current and M-current by divergent signal transduction cascades. J Neurosci 26: 11588–11598, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lothman EW, Collins RC. Kainic acid induced limbic seizures: metabolic, behavioral, electroencephalographic and neuropathological correlates. Brain Res 218: 299–318, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lothman EW, Hatlelid JM, Zorumski CF. Functional mapping of limbic seizures originating in the hippocampus: a combined 2-deoxyglucose and electrophysiologic study. Brain Res 360: 92–100, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan PS, Kapur J. Factors underlying bursting behavior in a network of cultured hippocampal neurons exposed to zero magnesium. J Neurophysiol 91: 946–957, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough JH, Jr, Shih TM. Neuropharmacological mechanisms of nerve agent-induced seizure and neuropathology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 21: 559–579, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsushima D, Takase K, Funabashi T, Kimura F. Gonadal steroids maintain 24 h acetylcholine release in the hippocampus: organizational and activational effects in behaving rats. J Neurosci 29: 3808–3815, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody I, Lambert JD, Heinemann U. Low extracellular magnesium induces epileptiform activity and spreading depression in rat hippocampal slices. J Neurophysiol 57: 869–888, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki H, Aikawa N, Shinozawa Y, Hori S, Fujishima S, Takuma K, Sagoh M. Sarin poisoning in Tokyo subway. Lancet 345: 980–981, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura T, Takasu N, Ishimatsu S, Miyanoki S, Mitsuhashi A, Kumada K, Tanaka K, Hinohara S. Report on 640 victims of the Tokyo subway sarin attack. Ann Emerg Med 28: 129–135, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe KA, Dani JA. Nicotinic stimulation produces multiple forms of increased glutamatergic synaptic transmission. J Neurosci 18: 7075–7083, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha ES, Swanson KL, Aracava Y, Goolsby JE, Maelicke A, Albuquerque EX. Paraoxon: cholinesterase-independent stimulation of transmitter release and selective block of ligand-gated ion channels in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 278: 1175–1187, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selyanko AA, Hadley JK, Wood IC, Abogadie FC, Jentsch TJ, Brown DA. Inhibition of KCNQ1-4 potassium channels expressed in mammalian cells via M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. J Physiol 522: 349–355, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro MS, Roche JP, Kaftan EJ, Cruzblanca H, Mackie K, Hille B. Reconstitution of muscarinic modulation of the KCNQ2/KCNQ3 K(+) channels that underlie the neuronal M current. J Neurosci 20: 1710–1721, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma G, Vijayaraghavan S. Modulation of presynaptic store calcium induces release of glutamate and postsynaptic firing. Neuron 38: 929–939, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih TM, McDonough JH., Jr Neurochemical mechanisms in soman-induced seizures. J Appl Toxicol 17: 255–264, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O, Scoville SA. Cells of origin of entorhinal cortical afferents to the hippocampus and fascia dentata of the rat. J Comp Neurol 169: 347–370, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Borck C, Colling SB, Jefferys JG. On the structure of ictal events in vitro. Epilepsia 37: 879–891, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Knowles WD, Miles R, Wong RK. Synchronized afterdischarges in the hippocampus: simulation studies of the cellular mechanism. Neuroscience 12: 1191–1200, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turski L, Ikonomidou C, Turski WA, Bortolotto ZA, Cavalheiro EA. Review: cholinergic mechanisms and epileptogenesis. The seizures induced by pilocarpine: a novel experimental model of intractable epilepsy. Synapse 3: 154–171, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turski WA, Cavalheiro EA, Schwarz M, Czuczwar SJ, Kleinrok Z, Turski L. Limbic seizures produced by pilocarpine in rats: behavioral, electroencephalographic and neuropathological study. Behav Brain Res 9: 315–335, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velisek L. Models of chemically-induced acute seizures. In: Models of Seizures and Epilepsy, edited by Pitkanen A, Schwartzkroin PA, Moshe SL. Burlington, MA: Elsevier, 2006, p. 127–152 [Google Scholar]

- Vervaeke K, Gu N, Agdestein C, Hu H, Storm JF. Kv7/KCNQ/M-channels in rat glutamatergic hippocampal axons and their role in regulation of excitability and transmitter release. J Physiol 576: 235–256, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue C, Yaari Y. KCNQ/M channels control spike afterdepolarization and burst generation in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 24: 4614–4624, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]