Abstract

The ventral intraparietal area (VIP) of the macaque monkey is thought to be involved in judging heading direction based on optic flow. We recorded neuronal discharges in VIP while monkeys were performing a two-alternative, forced-choice heading discrimination task to relate quantitatively the activity of VIP neurons to monkeys' perceptual choices. Most VIP neurons were responsive to simulated heading stimuli and were tuned such that their responses changed across a range of forward trajectories. Using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, we found that most VIP neurons were less sensitive to small heading changes than was the monkey, although a minority of neurons were equally sensitive. Pursuit eye movements modestly yet significantly increased both neuronal and behavioral thresholds by approximately the same amount. Our results support the view that VIP activity is involved in self-motion judgments.

INTRODUCTION

Primates are very good at recovering heading from the optic flow pattern created by relative movement between the eyes and the surrounding environment during self-motion (Banks et al. 1996; Britten and Van Wezel 2002; Royden et al. 1992; Warren and Hannon 1990). However, the neural mechanisms involved in this process remain poorly understood. The medial superior temporal area (MST) is known to be involved in such behavior (Britten and Van Wezel 2002; Duffy and Wurtz 1991; Graziano et al. 1994; Gu et al. 2008; Tanaka and Saito 1989), and other structures are also likely to participate. The ventral intraparietal area (VIP) is a multimodal area (Bremmer et al. 2002a; Duhamel et al. 1998; Schlack et al. 2005), where neuronal responses are selective for the direction of linear motion (Colby et al. 1993) and complex optic flow patterns (Colby et al. 1993; Schaafsma and Duysens 1996). The results of physiological experiments using a variety of stimuli suggest that VIP might be involved in motion perception (Bremmer et al. 2002a; Cook and Maunsell 2002; Schaafsma and Duysens 1996; Zhang et al. 2004). Both MST and VIP receive their predominant visual input from the middle temporal area (MT) (Lewis and Van Essen 2000; Maunsell and Van Essen 1983) and project to parietal and frontal areas (Jones and Powell 1970; Jones et al. 1978) thought to be involved in the planning and guidance of behavior.

In this study, we recorded from single VIP neurons during a two-alternative heading discrimination task to explore the link between neuronal discharge and perceptual decisions. We established that the information encoded in VIP neuronal discharges is sufficient to support heading judgments by measuring neuronal sensitivity to near-threshold stimuli. We found that the sensitivity of single VIP neurons was on average somewhat poorer than the monkey's behavioral performance, but the best neurons' performance equaled that of the monkey. Our observations support a close relationship between VIP activity and heading perception.

METHODS

Subjects, surgery, and training

Two female rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were involved in this study. Each was chronically implanted with a titanium post (Crist Instruments) for head restraint and a scleral search coil for eye movement tracking (Judge et al. 1980). Monkeys were fully trained on fixation, memory saccade, and heading discrimination tasks, using operant conditioning techniques with juice rewards. After the monkeys' psychophysical performance had stabilized, a lightweight plastic recording cylinder (Crist Instruments) was implanted over the intraparietal sulcus (IPS) in a parasaggital plane and angled 45° posterior to the coronal plane, allowing dorsal-posterior access to VIP. During the experiments, the monkeys were seated in a specialized primate chair (Crist Instruments) with their heads restrained. Liquid reward was delivered by the experimental computer and received through a lick tube. Eye movements were tracked with a scleral search coil system (David Northmore) and passed to the experimental control computer. During the mapping experiments, arm movements were monitored when necessary using small CCD camera (LED lights were used for local illumination) placed in front of the primate chair and under the CRT monitor. All animal procedures were approved by UC Davis Animal Care and Use Committee and fully conformed to ILAR and USDA guidelines for the care and treatment of experimental animals.

Visual stimuli and behavioral task

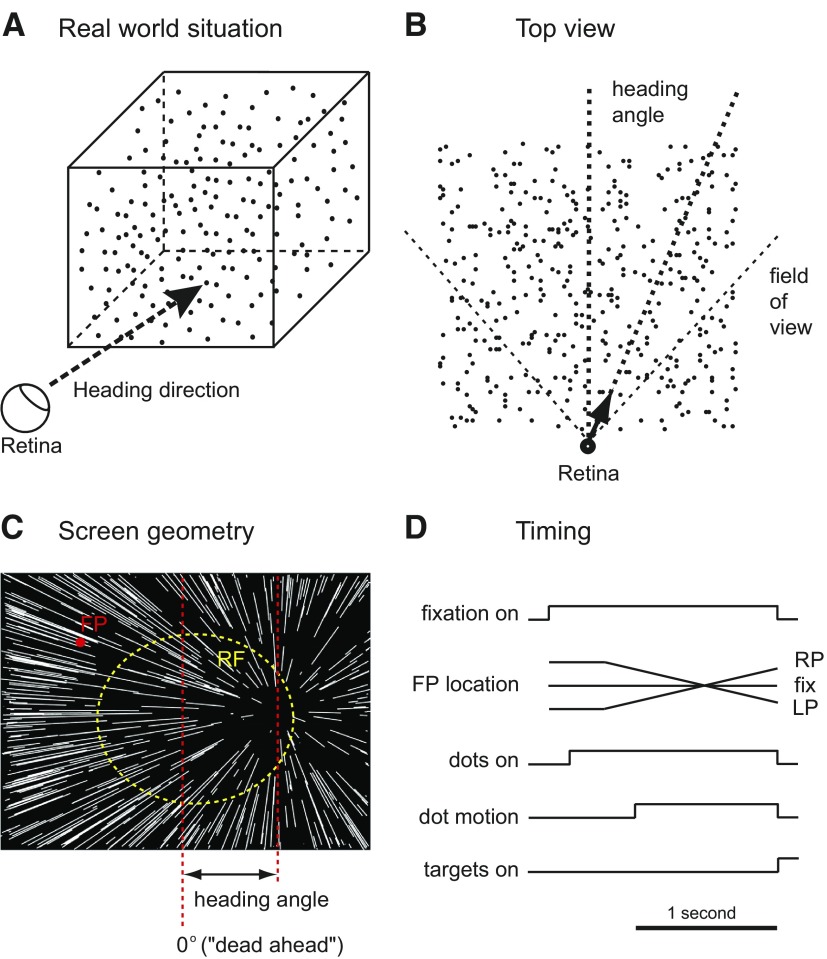

Visual stimuli were generated by custom software on a personal computer and presented on a CRT monitor, which subtended 72° horizontally and 56° vertically at 28 cm viewing distance. The heading stimulus we used simulated the self-motion of the monkey toward a three-dimensional cube of points (schematic diagram in Fig. 1A) 10 m on a side and centered 5.5 m away. Importantly, these stimuli only contained motion cues to depth: no stereo or size cues were used. Heading angle is defined as the angle in the horizontal plane between dead ahead and the simulated self-motion direction (Fig. 1B). The center of expansion on the display (Fig. 1C) corresponds to the heading direction. During the heading discrimination experiment, the heading angle for any given trial was randomly chosen from a range of horizontally varying angles between 0.5 and 16°, spaced by factors of two, in both directions. This sampling method allowed us to capture the most sensitive part of the psychometric function while ensuring that a large fraction of trials were difficult and attentionally demanding. At the end of each trial, the monkey was required to report the perceived heading direction as leftward or rightward by making a saccade toward the saccade target presented on the same side of the screen.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of visual stimuli and behavioral task. A: the heading stimulus, which simulated an observer's movement toward a 3-dimensional cube of dots. The heading angle is defined as the angle between dead ahead and the simulated trajectory. B: top view of the simulated geometry of the task. The arrow shows the trajectory with respect to the simulated 3-dimensional dot field; its length is approximately to scale for the speed of the simulated trajectory. The vertical dashed line depicts dead ahead. C: observer view of heading stimulus showing the pattern of dot movements. If the eyes are stationary, the center of this expanding pattern indicates the heading direction, which was varied horizontally across the center of display from trial to trial. The red dot represents the fixation point, and the dashed yellow circle indicates the receptive field of a ventral intraparietal area (VIP) neuron. D: timing of events in single trials.

To study the interaction of VIP neuronal signals with ongoing eye movements, we included trials where the monkey was pursuing the smoothly moving fixation point (ramps in Fig. 1D). During a pursuit trial, the monkey was required to follow the fixation point, which started offset 7.5° horizontally, at 10°/s for 1.3 s. Pursuit began 250 ms before the simulated trajectory started, so that the monkey would be pursuing steadily during the entire 1-s dot motion period. The monkey had to maintain its gaze within a small window (3° horizontal × 2° vertically) around the target during the pursuit period. Unfortunately, undetected software errors led to analog eye position signals being discarded during recording, so we cannot quantitatively analyze the accuracy of pursuit.

All heading angles were presented under three different pursuit conditions: −10, 0, and 10°/s. Because simulated depth information was embedded in the visual stimulus we used, the resulting retinal image no longer contained a single focus of expansion; dots at different depths would move in a range of offset retinal directions. However, the arithmetic mean shift of the center of the pattern for our pursuit speed is ∼40° in the direction of the pursuit. Previous work from this laboratory has shown that VIP neurons' tuning properties are quite stable despite this large change in the retinal flow pattern (Zhang et al. 2004). Timing of events of the task is shown in Fig. 1D.

Cell recording

Recording experiments were performed using standard extracellular techniques in the left hemisphere of monkey F and the right hemisphere of monkey K. Neuronal discharges were collected using tungsten microelectrodes (FHC), which were introduced through stainless steel guide tubes held in place by a plastic grid attached to the inside of the recording cylinder. Before beginning single unit recording experiments, we mapped each cylinder extensively. Area VIP was localized using both physiological and anatomical landmarks. The IPS was identified by its appropriate depth and by the presence of adjacent areas with the properties of the lateral intraparietal area (LIP) and VIP, with the putative LIP located dorsal and lateral to VIP. LIP was identified by presaccadic responses during the delayed memory-saccade task (Barash et al. 1991). By monitoring the spontaneous arm movements of the monkeys using a small CCD video camera, we could identify the other adjacent area, the medial intraparietal area (MIP), which is characterized by reach-related activity (Eskandar and Assad 2002). Area VIP, between these two areas, was identified based on a high percentage of direction-selective units and its position close to the bottom of IPS. Cylinder locations were guided by MRI scans, and in one monkey, recording locations were confirmed by MRI. The signal from the microelectrode was amplified, and action potentials from single neurons were isolated using a dual time-amplitude window discriminator (Bak Electronics). Only cells with visual motion responses were recorded. To avoid sampling biases, we never recorded from the same location within the following five experiments. Once a neuron was successfully isolated, we determined the receptive field (RF) location and size using handheld moving bar stimuli or computer-generated moving dot patches. Neurons in VIP have large RFs (most of them around 30° and some almost 70°). Our stimulus was always full screen, and we tried to bring the center of RF as close as possible to the center of display (and thus the center of the range of headings) by adjusting the monkey's fixation point. Previous reports (Duhamel et al. 1997) suggested that some VIP neurons' RFs are in head-centered coordinates and would thus never become properly centered using this approach. In our experiments, such compensation for fixation location was rarely observed. This might be in part because of the relatively narrow range of fixation eccentricities we used. The coordinate system of a neuron would be difficult to estimate with large RFs and small changes in fixation. In any case, because we did not systematically vary fixation, nor quantitatively map the RFs, we were unable to estimate how our neurons mapped onto the range of coordinate systems described in the literature. Qualitative mapping, however, allows us to state without reservation that, for all our cells, at least one half of the RF of the neuron was covered by the heading stimulus; cells that did not meet this criterion were not studied. In practice, this strategy, which was based on hardware limitations, biased our sampling to the central representation in VIP; exploring the consequences of this bias would require alternate display hardware.

The time of stimulus events and action potentials was recorded using the public domain software package REX (Hays et al. 1982) with 1-ms resolution. Typically, a block of trials included 12 heading conditions (±0.5, ±1, ±2, ±4, ±8, and ±16°) and 3 eye movement conditions (fixation and left and right pursuit at 10°/s) randomly interleaved. Forty-two percent of the data (n = 21) were collected from monkey F, and the others (58%, n = 29) were collected from monkey K.

Data analysis

We measured the behavioral and neuronal responses to the heading discrimination task during both fixation and smooth pursuit eye movement. Each specific stimulus condition was repeated ≥10 times (20∼30 repetitions for 88% of the cells; 10∼20 repetitions for the remaining). Behavioral performance was measured as the proportion of rightward choices. A set of those data, including average performance of all 12 heading angles at a particular pursuit condition, was fit with a probit function

| (1) |

where R(h) is the behavioral response (proportion right choices), h is the heading angle, μ is the mean, and σ is the width or SD. Threshold was defined as the width (σ). The maximum likelihood fit was established iteratively (after Stepit; http://ftp.ccl.net/cca/software/SOURCES/FORTRAN/simplex/stepit.f), under the assumption of binomially distributed choices.

Neuronal responses consisted of the total spike count during the 1-s simulated self-movement period. The arithmetic mean firing rate at each heading direction was used to describe neuronal tuning. Each data set, which contains averaged neuronal responses of all 12 heading angles for each pursuit condition, was fit with both a modified probit function

| (2) |

and a gaussian function

| (3) |

where B is the baseline, A is the amplitude, and other terms are the same as in Eq. 1. From previous work, we know that VIP neurons can either be sigmoidally or band-pass tuned across the range of frontal headings we use (Zhang et al. 2004). In this study, we classified them in the same way, according to which function gave the better fit. However, this classification did not influence our threshold analysis. To be included in the threshold analysis, we required the fit to one or the other of these functions to capture significantly more variance than the best constant rate (likelihood ratio test, P < 0.05). All the visually responsive neurons we encountered passed this test. All of the band-pass cells in this sample had tuning peaks offset from 0 and thus exhibited a clear preference for one heading over the other. This allowed the threshold analysis to proceed in the same manner as for sigmoidally tuned cells. For threshold analysis, the neuronal performance was derived using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis (Green and Swets 1966) based on a opponent, two-neuron decision assumption (Britten et al. 1992). This analysis produces, for each heading direction, a performance estimate bounded between 0 and 1, with 0.5 being chance performance. It corresponds to the performance of an ideal observer making the heading discrimination solely on the basis of the two response distributions being compared and is quantitatively comparable to the simultaneously measured psychometric performance. The resulting performance values were then fit with the same form of probit function (Eq. 1) as for behavioral data (see Fig. 3). We also examined a nonopponent decision assumption, in which each firing rate was compared against the firing rate at near-zero headings. This analysis produced the expected modest increase in threshold for each cell (data not shown).

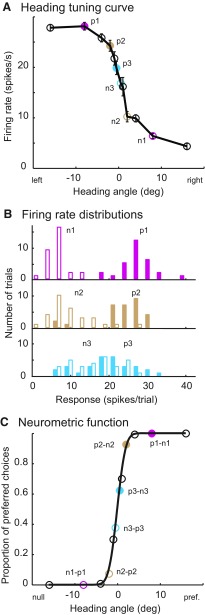

Fig. 3.

Neurometric function analysis. A: neuronal responses of 1 VIP neuron during fixation while we varied the heading direction from −16 to 16°. Each pair of circles in the same color indicates the average responses from this neuron and from its hypothetical antineuron. B: examples of firing rate distributions from the neuron against its antineuron. Filled bars correspond to filled circles in A. For each pair of distributions, a single ROC value was calculated. This ROC value represents the observed odds that the neuron fires more strongly than the antineuron. C: each circle represents a ROC value calculated at that heading direction. Solid black curve represents the maximum likelihood probit fit.

Statistics

Most statistical testing was performed using log-transformed thresholds or threshold ratios as dependent variables in a repeated-measures ANOVA design. In this design, independent variables were monkey identity, type of tuning (probit or gaussian), and cell. Pursuit condition was included as a within-subject (nested within cell) variable. Testing was performed using the on-line statistics site, Rice Virtual Lab in Statistics (http://onlinestatbook.com/stat_analysis/index.html).

RESULTS

After mapping the intraparietal sulcus and identifying area VIP (see methods), we measured neuronal discharges in VIP while the monkey was performing the heading discrimination task shown in Fig. 1. The heading stimulus simulated the visual effects of observer motion toward a three-dimensional cube of points (Fig. 1A).

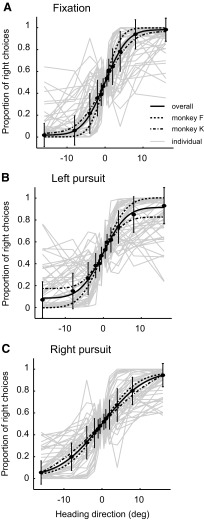

We trained two monkeys on the heading discrimination task. Both were trained for many months until their thresholds were asymptotically low and stable across the range of conditions they were likely to encounter in the physiological experiments. Figure 2 shows our behavioral results. Each data set was fitted to a probit function using maximum-likelihood fitting. Threshold was defined as the width (σ) of the best-fit function, which corresponds to the heading angle where performance was 84% correct. There was no significant difference between animals (repeated-measures ANOVA, df = 1, F = 0.50, P = 0.48). Pursuit eye movements induced modest yet significant increases in psychophysical threshold (median thresholds of 1.90, 2.47, and 2.47° for fixation and left and right pursuit; repeated-measures ANOVA, df = 2, F = 24.98, P < 0.01), but there was no significant difference between the two pursuit conditions (paired t-test, P = 0.35, t = 0.95, df = 49).

Fig. 2.

Psychophysical performance. Solid curves represent the average performance (median, n = 50) of both monkeys for different pursuit conditions. Dashed curves represent the average performance of each monkey; the error bars show SE. Each light gray curve represents the outcome of an individual experiment.

While these behavioral data were being recorded, we measured neuronal responses to the same stimuli. Consistent with previous observations, we found that most VIP neurons are very sensitive to small heading changes (Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2).1 The heading tuning curve in Fig. 3A shows how a typical VIP neuron responded to different heading directions. To analyze these data in a manner that allows direct comparison with the psychophysics, we used neurometric function analysis (Bradley et al. 1987; Britten et al. 1992; Tolhurst et al. 1983). Our specific formulation uses an opponent downstream step; this is sometimes referred to as the neuron–antineuron model. The antineuron is identical with the neuron being recorded in all respects except it prefers the opposite heading direction. Each pair of solid circles in same color (Fig. 3A) represents one pair of averaged responses of neuron and antineuron. The frequency histogram in Fig. 3B shows the corresponding firing rate distributions. For any given direction, the two distributions are used to calculate a ROC area. For example, to calculate the +0.5° point of the curve in Fig. 3C, the −0.5° distribution would represent the neuron (preferring left in this case), and the +0.5° distribution would represent the firing rate distribution of the hypothetical antineuron. Because the firing rate of the neuron is slightly higher, this ROC area is slightly >0.5. To derive the points on the left side of the neurometric function, the nonpreferred distributions (from the right side of the curve in Fig. 3A) are used for the neuron and the preferred-direction distributions are used for the antineuron. This process of generating a single ROC performance estimate is repeated for each heading direction, and the resulting curve is fitted with the same form of probit function as used for the psychophysics This allows direct and quantitative comparison of the two kinds of data. Because the symmetry of the functions is guaranteed by our analysis, we will focus on the slope of the neurometric functions, captured by the σ parameter of the probit function.

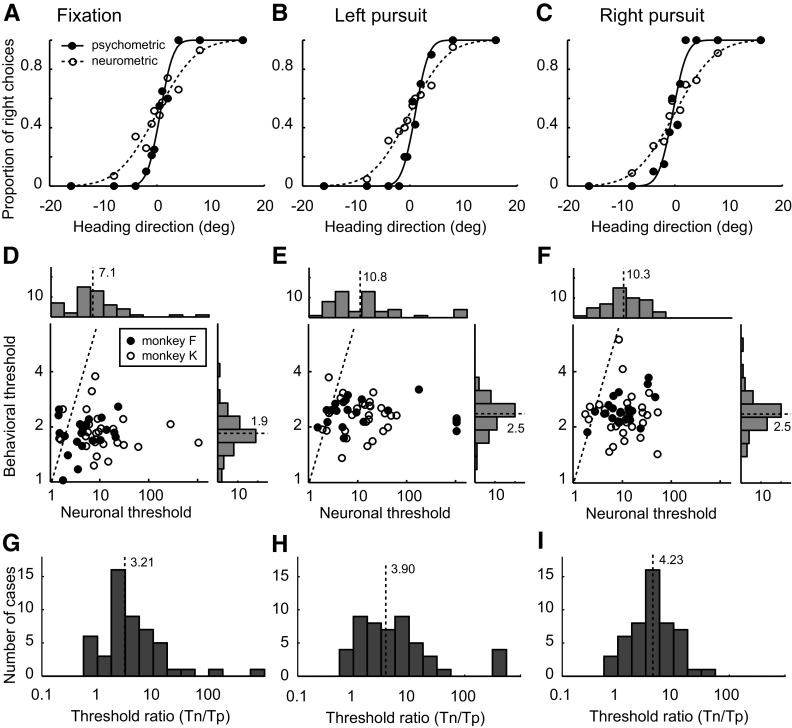

The neurons were very sensitive to small changes in heading, with the best neurons' performance equaling that of the monkey. In Fig. 4, we show both the individual neurons' performance, as well as averages of specific subsets of our sample. Neuronal thresholds did not differ between monkeys (repeated-measures ANOVA, df = 1, F = 1.08 P = 0.30), so we pooled across monkeys for subsequent analyses. The presence of smooth pursuit, however, significantly influenced neuronal sensitivity, with average thresholds being higher for either direction of pursuit (7.07, 10.83, and 10.28° corresponding to fixation and left and right pursuit; repeated-measures ANOVA, df = 2, F = 5.46, P < 0.01). In a previous study (Zhang et al. 2004), we observed that there are two groups of VIP neurons, differing by whether they show peaked or monotonic tuning across frontal headings. Those with sigmoid tunings presumably prefer more extreme headings than we sampled. We hypothesized that those with peaked tuning, indicating tuning near dead ahead, would show lower sensitivity. Oddly, however, we found no significant difference between these two groups (repeated-measures ANOVA, df = 1, F = 1.19, P = 0.28). This was because the tuning peaks in the band-pass cells were mostly offset from dead ahead, giving them dynamic range through the near-zero headings that were important to our measure of sensitivity Additionally, many of the most insensitive neurons (presumably tuned for very eccentric headings) were better fit with probit functions. The tunings of all our neurons are shown in Supplemental Fig. S3.

Fig. 4.

Physiological results. Each light gray curve, which is comparable to the light gray curve in Fig. 2, represents a set of ROC values derived as shown in Fig. 3. Filled symbols depict median neuronal performance (n = 50) from both monkeys for the different pursuit conditions, and the smooth curves are probit functions fit to these points. The dashed curves show the results from each monkey individually. Error bars depict SE across cells.

The principal goal of this experiment was a quantitative comparison of neuronal and behavioral sensitivity. In our example (Fig. 5, A–C), the neuronal threshold is 2.89 times higher than psychophysical threshold on average, which is typical of our data set. However, there was a range of relative sensitivity. The best neurons equaled or were slightly superior to psychophysical performance; a few were much worse. Whereas Fig. 5, D and E, gives the summary of both behavioral and neuronal thresholds, Fig. 5, G–I, shows the results of direct comparison on their performances: the distributions of the threshold ratio (neuronal threshold divided by psychophysical threshold) for different pursuit conditions. The median threshold ratios were 3.21, 3.90, and 4.23, respectively. These modest differences were statistically significant (repeated-measures ANOVA, df = 1, F = 5.53, P = 0.02). Additionally, pursuit significantly decreased relative neuronal performance (repeated-measures ANOVA, P < 0.01, df = 2, F = 24.99). There was no significant correlation between neuronal and behavioral threshold under any pursuit condition (fixation: r = −0.01, P = 0.97; left pursuit: r = −0.07, P = 0.65; right pursuit: r = 0.08, P = 0.59).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of physiology and psychophysics. A–C: single-cell example of psychometric functions (solid curves) and neurometric functions (dashed curves). The filled circles indicate the psychophysical data, whereas the blank circles represent the neuronal data. The thresholds of the psychometric and neurometric functions are 1.92 and 5.75 (A), 1.96 and 5.52 (B), and 2.07 and 5.90° (C), respectively. D–F: summaries of the behavioral thresholds and neuronal thresholds. The dashed black line in each scatter plot represents unity. The histograms along top and right of each panel depict the frequency of occurrence of thresholds on the corresponding axis. The dashed line and number nearby in each histogram indicate the median of that distribution. G–I: distributions of threshold ratios.

To find out what caused the decrease of neuronal sensitivity during pursuit, we analyzed the influence of pursuit on the firing rate distributions of neuron and antineuron. We found that the changes of sensitivity were significantly correlated with changes of mean firing rates (left pursuit: r = 0.20, P < 0.001; right pursuit: r = 0.36, P < 0.001). There was no relationship between the sensitivity and the variance of firing rate distributions (left pursuit: r < 0.01, P = 0.99; right pursuit: r = 0.09, P = 0.14). This result is consistent with a previous observation (Zhang et al. 2004) where pursuit decreased the amplitude of heading tuning function and increased the width.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we compared the heading discrimination performance of monkeys with that of single VIP neurons in response to visual displays simulating self-motion. Although neurons in VIP exhibited a wide range of sensitivities, the most sensitive equaled perceptual performance. Furthermore, neuronal and perceptual performance was modestly and similarly degraded by smooth pursuit eye movements. These observations suggest a close relationship between activity in VIP and the perception of heading.

Technical issues

We term our stimulus “simulated self-motion,” but the monkey is not actually moving. This places some cues in conflict that are concordant during actual self-motion. The most significant other cues would be vestibular and proprioceptive. Although no one has to our knowledge studied proprioceptive influences on VIP, vestibular responses are conspicuous (Bremmer et al. 2002b; Klam and Graf 2006; Schlack et al. 2002). Where visual and vestibular stimuli are in conflict, either modality can dominate (Schlack et al. 2002). However, the stationary subject in our experiments is more like the visual-only condition in those experiments, and this condition clearly represents a lesser form of conflict. Visual responses are usually still brisk and directional under these conditions, as we also observe.

Another cue that is in conflict in our experiments is purely visual: stereoscopic depth information. Our stimuli are placed quite close to the animal to increase the size of the display, and this causes significant, approximately constant, vergence. Although all the stimuli reported in this paper were presented binocularly, pilot experiments on both human and monkey subjects using monocular stimulation showed no noticeable differences. In human psychophysics, binocular stimulation improved heading thresholds when the visual stimulation was noisy, which profoundly degrades the monocular depth information from motion parallax (van den Berg and Brenner 1994). In our experiments, motion was fully coherent, and thus monocular cues to simulated depth were robust.

Subjective impressions also help to suggest that our displays were within a normal physiological range. All naïve or experienced human subjects who viewed our displays reported a sense of self-motion, as opposed to a sense of an object on the screen moving toward them.

Another category of concern about our experimental design arises from the decision to adjust the heading display (by moving the fixation point) to optimize for each neuron. We chose this design to be able to compare these results with previous work from the laboratory and because this would efficiently estimate an upper bound on sensitivity. Horizontal direction selectivity predicts heading tuning in these conditions (Zhang et al. 2004), and placing the center of the display over the RF of the neuron maximizes the change in the horizontal component of optic flow vectors over the RF. However, many neurons with more eccentric RFs could not be centered in this way, and many of these also showed high sensitivity. The mechanism for this would likely be through the speed selectivity of the neuron: higher velocities are present in the RF as the center of expansion is moved away from the RF. The question of the contribution of speed tuning to heading selectivity has not been well explored, either in VIP or in MST.

Relationship with previous work

We found perceptual thresholds near 2°, close to those reported for humans (Royden et al. 1992) and monkeys (Gu et al. 2008) on similar tasks. Furthermore, the modest effects of smooth pursuit on performance are also in the range of what has been reported for humans (Royden et al. 1992) and monkeys (Britten and Van Wezel 2002). The literature has made a very strong case for the involvement of area MST in heading discrimination, and we have the opportunity to compare our results against those from MST. MST neurons show similar neurometric thresholds as do those in VIP (Gu et al. 2007, 2008), although precise comparison would be difficult because of subtle difference in the stimuli. In the experiments of Gu et al., the stimuli included both stereo and size cues to depth (which might improve performance) but were also presented at lower coherence (which would reduce performance). Nonetheless, the performance of both areas appears similar, and both representations are sufficient to support behavioral performance.

Several laboratories have studied the stability of MST neuronal tuning under pursuit. In the most closely related work, the Andersen laboratory (Shenoy et al. 1999) measured tuning to both real and simulated pursuit. In these experiments, which also differed from ours in several important respects (direction of pursuit, area of visual stimulation, lack of simulated depth), MST neurons systematically undercompensated for pursuit. Importantly, their compensation was vastly reduced in the retinally equivalent simulated pursuit condition. This suggests that extraretinal signals of pursuit influence the tuning of MST neurons. Because VIP also contains explicit extraretinal signals of pursuit and compensates well for pursuit, we speculate that this compensation will also be largely extraretinally based.

The Duffy group (Upadhyay et al. 2000) have measured the tuning of MST neurons to simulated headings with and without the presence of simulated depth. They find that adding multiple depth planes to the stimulus, as we have done in these experiments, helps to maintain a stable representation under pursuit. Their stimuli contained no more than three depth planes, unlike the continuously varying depth in our stimuli. Other differences in the stimuli and the analysis preclude more quantitative comparison, so many interesting questions remain about the contributions of multiple depths (and therefore speeds) to pursuit tolerance, both in MST and VIP.

One interesting and unusual aspect of VIP neuronal responses is the presence of compensation for the direction of gaze. The result of this compensation is that each neuron can encode the location of stimuli in retinotopic coordinates, head-centered coordinates, or anything in between (Avillac et al. 2005; Duhamel et al. 1997; Schlack et al. 2005). This observation has both practical and theoretical consequences for this study. Although we did not quantitatively map the RFs of our neurons, we were vigilant that all neurons we studied (presumably including the more head-centered ones) would always overlap our stimulus substantially. Because of the limited range of eye movements in our experiments, we are reasonably certain that the coordinate system in which individual neurons represent spatial location would have little impact on our measurements. The only bias that we could not avoid was an undersampling of neurons with far peripheral RFs, which could not be arranged to overlap our display. In previous work, we have reported that many VIP neurons are in head-centered coordinates with respect to eye velocity (Zhang et al. 2004). One evident outstanding question is of the relationship between the compensation for eye velocity and that for eye position.

VIP neurons, like MST neurons, have explicit responses correlated with the direction and speed of smooth pursuit eye movements (Schlack et al. 2003). These represent all directions approximately evenly and most often (but not always) have a preferred direction opposite to the visual preferred direction of the cell. From these observations, one might predict systematic shifts in the baseline in our experiments, related to the heading preference of the cell (because this is largely determined by horizontal direction selectivity). Although we did not measure pursuit-only responses in these experiments, we recorded such responses in a previous study (Zhang et al. 2004). In those experiments, the sampling of heading was too coarse to provide useful data for neurometric function analysis, but we performed a related analysis on those data. The slope of the middle part of the heading tuning function correlates highly with neuronal sensitivity, so we analyzed the relationship between these slopes and the sign and magnitude of explicit pursuit responses (Supplemental Fig. S4). We found that larger pursuit responses were correlated with greater decreases in tuning function slope. This result is not what one would predict from the superposition of pursuit responses and visual responses. Therefore it seems likely that pursuit signals and visual signals interact in more complex ways, as they do in MST (Chukoskie and Movshon 2009). Quantitative measurements of this interaction are clearly important for our understanding of VIP.

Functional role of VIP

There is considerable evidence for the notion that VIP plays a role in near-field behaviors, especially object or obstacle avoidance (Colby et al. 1993; Cooke et al. 2003; Graziano and Cooke 2006). There is an apparent distinction to be drawn between the representations suitable for object-oriented tasks in the near field and trajectory estimation, which often rests on far-field cues. However, this apparent dichotomy disappears on closer examination. In normal locomotion, distant objects are frequently goals, and near objects are frequently obstacles to be avoided. It therefore makes perfect sense to represent both observer motion and object motion in the same area. Under this view, the multimodal representation in VIP also makes good sense. Many of the same cues (e.g., visual, somatosensory) are potentially informative about both nearby objects in independent motion and observer motion. The challenge for the field in studying such a complex representation will be to disentangle the various signals from each other. Clearly, one of the important next steps will be to move toward more natural self-motion tasks that involve goals, obstacles, and optic flow information. Psychophysical and theoretical studies have made substantial progress in this direction (Elder et al. 2009; Fajen and Warren 2003), but working out the physiological substrates for this behavior is an important unsolved problem.

These results support an intimate role for VIP in visually based heading perception. Although only a minority of neurons are equivalently sensitive in the monkey to small changes in heading, the population clearly contains adequate information to guide behavior. This pattern of results seems to be the most common finding in studies that, like this one, compare neuronal and behavioral sensitivity on difference limen (just noticeable difference) tasks. Similar results have been obtained with respect to fine direction discrimination (Purushothaman and Bradley 2005) and coarse stereo discrimination (Uka and DeAngelis 2003) in area MT and in stereo discrimination tasks in V1 (Prince et al. 2000). It is clear from theory (Jazayeri and Movshon 2006; Ma et al. 2006) that populations of coarsely coding neurons have many advantages for flexibility of readout and that precise estimates of stimulus attributes can be obtained, even if each neuron in the population is both noisy and broadly tuned. The properties we report in VIP might therefore be nearly optimal for accurate and flexible representation of heading.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Eye Institute Grants EY-10562 to K. H. Britten and Vision Core Center Grant EY-12576, PI Chalupa.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. R. Engelhardt for animal care and training; D. J. Sperka for software support and development; and J. Ditterich, C. H. McCool, and S. W. Egger for helpful comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental data.

REFERENCES

- Avillac M, Deneve S, Olivier E, Pouget A, Duhamel JR. Reference frames for representing visual and tactile locations in parietal cortex. Nat Neurosci 8: 941–949, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks MS, Erlich SM, Backus BT, Crowell JA. Estimating heading during real and simulated eye movements. Vision Res 36: 431–443, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barash S, Bracewell RM, Fogassi L, Gnadt JW, Andersen RA. Saccade-related activity in the lateral intraparietal area. I. Temporal properties; comparison with area 7a. J Neurophysiol 66: 1095–1108, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley A, Skottun BC, Ohzawa I, Sclar G, Freeman RD. Visual orientation and spatial frequency discrimination: a comparison of single cells and behavior. J Neurophysiol 57: 755–772, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer F, Duhamel JR, Ben Hamed S, Graf W. Heading encoding in the macaque ventral intraparietal area (VIP). Eur J Neurosci 16: 1554–1568, 2002a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer F, Klam F, Duhamel JR, Ben Hamed S, Graf W. Visual-vestibular interactive responses in the macaque ventral intraparietal area (VIP). Eur J Neurosci 16: 1569–1586, 2002b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten KH, Shadlen MN, Newsome WT, Movshon JA. The analysis of visual motion: a comparison of neuronal and psychophysical performance. J Neurosci 12: 4745–4765, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten KH, Van Wezel RJ. Area MST and heading perception in macaque monkeys. Cereb Cortex 12: 692–701, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chukoskie L, Movshon JA. Modulation of visual signals in macaque MT and MST neurons during pursuit eye movement. J Neurophysiol 102: 3225–3233, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby CL, Duhamel JR, Goldberg ME. Ventral intraparietal area of the macaque: anatomic location and visual response properties. J Neurophysiol 69: 902–914, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook EP, Maunsell JH. Dynamics of neuronal responses in macaque MT and VIP during motion detection. Nat Neurosci 5: 985–994, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke DF, Taylor CS, Moore T, Graziano MS. Complex movements evoked by microstimulation of the ventral intraparietal area. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 6163–6168, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy CJ, Wurtz RH. Sensitivity of MST neurons to optic flow stimuli. I. A continuum of response selectivity to large-field stimuli. J Neurophysiol 65: 1329–1345, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhamel JR, Bremmer F, BenHamed S, Graf W. Spatial invariance of visual receptive fields in parietal cortex neurons. Nature 389: 845–848, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhamel JR, Colby CL, Goldberg ME. Ventral intraparietal area of the macaque: congruent visual and somatic response properties. J Neurophysiol 79: 126–136, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder DM, Grossberg S, Mingolla E. A neural model of visually guided steering, obstacle avoidance, and route selection. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 35: 1501–1531, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskandar EN, Assad JA. Distinct nature of directional signals among parietal cortical areas during visual guidance. J Neurophysiol 88: 1777–1790, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajen BR, Warren WH. Behavioral dynamics of steering, obstacle avoidance, and route selection. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 29: 343–362, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano MS, Cooke DF. Parieto-frontal interactions, personal space, and defensive behavior. Neuropsychologia 44: 2621–2635, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano MSA, Andersen RA, Snowden RJ. Tuning of MST neurons to spiral motions. J Neurosci 14: 54–67, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Swets JA. Signal Detection Theory and Psychophysics. New York: John Wiley, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Angelaki DE, Deangelis GC. Neural correlates of multisensory cue integration in macaque MSTd. Nat Neurosci 11: 1201–1210, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. A functional link between area MSTd and heading perception based on vestibular signals. Nat Neurosci 10: 1038–1047, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays AV, Richmond BJ, Optican LM. A UNIX-based multiple process system for real-time data acquisition and control. WESCON Conf Proc 2: 1–10, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Jazayeri M, Movshon JA. Optimal representation of sensory information by neural populations. Nat Neurosci 9: 690–696, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG, Coulter JD, Hendry SH. Intracortical connectivity of architectonic fields in the somatic sensory, motor and parietal cortex of monkeys. J Comp Neurol 181: 291–347, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG, Powell TP. An anatomical study of converging sensory pathways within the cerebral cortex of the monkey. Brain 93: 793–820, 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge SJ, Richmond BJ, Chu FC. Implantation of magnetic search coils for measurement of eye position: an improved method. Vision Res 20: 535–538, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klam F, Graf W. Discrimination between active and passive head movements by macaque ventral and medial intraparietal cortex neurons. J Physiol 574: 367–386, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JW, Van Essen DC. Corticocortical connections of visual, sensorimotor, and multimodal processing areas in the parietal lobe of the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol 428: 112–137, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma WJ, Beck JM, Latham PE, Pouget A. Bayesian inference with probabilistic population codes. Nat Neurosci 9: 1432–1438, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunsell JHR, Van Essen DC. The connections of the middle temporal visual area (MT) and their relationship to a cortical hierarchy in the macaque monkey. J Neurosci 3: 2563–2586, 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince SJ, Pointon AD, Cumming BG, Parker AJ. The precision of single neuron responses in cortical area V1 during stereoscopic depth judgments. J Neurosci 20: 3387–3400, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purushothaman G, Bradley DC. Neural population code for fine perceptual decisions in area MT. Nat Neurosci 8: 99–106, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royden CS, Banks MS, Crowell JA. The perception of heading during eye movements. Nature 360: 583–585, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma SJ, Duysens J. Neurons in the ventral intraparietal area of awake macaque monkey closely resemble neurons in the dorsal part of the medial superior temporal area in their responses to optic flow patterns. J Neurophysiol 76: 4056–4068, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlack A, Hoffmann KP, Bremmer F. Interaction of linear vestibular and visual stimulation in the macaque ventral intraparietal area (VIP). Eur J Neurosci 16: 1877–1886, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlack A, Hoffmann KP, Bremmer F. Selectivity of macaque ventral intraparietal area (area VIP) for smooth pursuit eye movements. J Physiol 551: 551–561, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlack A, Sterbing-D'Angelo SJ, Hartung K, Hoffmann KP, Bremmer F. Multisensory space representations in the macaque ventral intraparietal area. J Neurosci 25: 4616–4625, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy KV, Bradley DC, Andersen RA. Influence of gaze rotation on the visual response of primate MSTd neurons. J Neurophysiol 81: 2764–2786, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Saito H. Analysis of motion of the visual field by direction, expansion/contraction and rotation cells clustered in the dorsal part of the medial superior temporal area of the Macaque monkey. J Neurophysiol 62: 626–641, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolhurst DJ, Movshon JA, Dean AF. The statistical reliability of signals in single neurons in cat and monkey visual cortex. Vision Res 23: 775–785, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uka T, DeAngelis GC. Contribution of middle temporal area to coarse depth discrimination: comparison of neuronal and psychophysical sensitivity. J Neurosci 23: 3515–3530, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay UD, Page WK, Duffy CJ. MST responses to pursuit across optic flow with motion parallax. J Neurophysiol 84: 818–826, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg AV, Brenner E. Why two eyes are better than one for judgements of heading. Nature 371: 700–702, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren WH, Hannon DJ. Eye movements and optical flow. J Opt Soc Am A 7: 160–169, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Heuer HW, Britten KH. Parietal area VIP neuronal responses to heading stimuli are encoded in head-centered coordinates. Neuron 42: 993–1001, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.