Abstract

Anion secretion by colonic epithelium is dependent on apical CFTR-mediated anion conductance and basolateral ion transport. In many tissues, the NKCC1 Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter mediates basolateral Cl− uptake. However, additional evidence suggests that the AE2 Cl−/HCO3− exchanger, when coupled with the NHE1 Na+/H+ exchanger or a Na+-HCO3− cotransporter (NBC), contributes to HCO3− and/or Cl− uptake. To analyze the secretory functions of AE2 in proximal colon, short-circuit current (Isc) responses to cAMP and inhibitors of basolateral anion transporters were measured in muscle-stripped wild-type (WT) and AE2-null (AE2−/−) proximal colon. In physiological Ringer, the magnitude of cAMP-stimulated Isc was the same in WT and AE2−/− colon. However, the Isc response in AE2−/− colon exhibited increased sensitivity to the NKCC1 inhibitor bumetanide and decreased sensitivity to the distilbene derivative SITS (which inhibits AE2 and some NBCs), indicating that loss of AE2 results in a switch to increased NKCC1-supported anion secretion. Removal of HCO3− resulted in robust cAMP-stimulated Isc in both AE2−/− and WT colon that was largely mediated by NKCC1, whereas removal of Cl− resulted in sharply decreased cAMP-stimulated Isc in AE2−/− colon relative to WT controls. Inhibition of NHE1 had no effect on cAMP-stimulated Isc in AE2−/− colon but caused a switch to NKCC1-supported secretion in WT colon. Thus, in AE2−/− colon, Cl− secretion supported by basolateral NKCC1 is enhanced, whereas HCO3− secretion is diminished. These results show that AE2 is a component of the basolateral ion transport mechanisms that support anion secretion in the proximal colon.

Keywords: anion exchanger, bicarbonate, ion transport

anion secretion by intestinal epithelial cells is required for maintenance of the appropriate fluidity and pH of the luminal contents. Electrogenic secretion of Cl− and HCO3− in response to cyclic nucleotides depends largely on the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (9); however, net CFTR-mediated anion secretion across the apical membrane requires a supply of Cl− and HCO3− and sensitive mechanisms to maintain cell volume, intracellular pH, and membrane potential. Unlike transport processes in the apical membrane, where CFTR is the dominant mechanism for anion secretion, the basolateral ion transport processes that support anion secretion appear to involve a number of different transporters.

During HCO3− secretion by intestinal epithelia, HCO3− is taken up across the basolateral membrane by one or more Na+/HCO3− cotransporter (NBC) isoforms (5, 30) and additional HCO3− is generated via spontaneous and catalyzed hydration of CO2 (13, 37). Studies using NBCe1 Na+/HCO3− cotransporter (Slc4a4)-null mutant mice showed that NBCe1 can contribute to HCO3− secretion in the proximal colon when carbonic anhydrase activity is inhibited and provided evidence for additional HCO3− uptake by both 4-acetoamido-4′-isothiocyanato-2–2′-stilbene disulfonic acid (SITS)-sensitive and SITS-insensitive mechanisms (20). For electrogenic Cl− secretion, basolateral uptake of Cl− is supported in large part by the NKCC1 Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter (Slc12a2) (18, 27). An additional source of Cl− for secretion, involving a SITS-sensitive Cl− uptake mechanism, has been identified in adult mouse duodenum following either gene-targeted deletion or acute inhibition of NKCC1 (50). The SITS sensitivity and other characteristics of the alternative basolateral Cl− uptake mechanism in duodenum suggest that it involves the AE2 Cl−/HCO3− exchanger (Slc4a2), possibly operating in concert with a Na+/HCO3− cotransporter (50).

Observations from other epithelial tissues indicate that AE2 also functions in concert with basolateral Na+/H+ exchange to support anion secretion. For example, defective gastric HCl secretion occurs in mice lacking either AE2 (23) or the NHE4 Na+/H+ exchanger (22), suggesting that coupling of these transporters may contribute to Cl− secretion in gastric parietal cells (22). Also, Cl− loading of parotid acinar cells during stimulated anion secretion is mediated by both Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport and Cl−/HCO3− exchange (48). Cl− secretion is reduced in parotid acinar cells of mice lacking either NKCC1 or the NHE1 Na+/H+ exchanger, indicating that both transporters contribute to Cl− secretion (17, 41). AE2 activity and expression is increased in parotid glands of NKCC1-null mice (17), suggesting that the coupled activities of AE2 and NHE1 contribute to Cl− uptake for secretion across the apical membrane (41).

Despite high levels of AE2 in proximal and distal colon (2, 51), where it is expressed in basolateral membranes (2), and suggestive evidence that it supports anion secretion in some intestinal segments (50), direct evidence that AE2 plays a major role in anion secretion in colon or in any other segment of the intestinal tract is lacking. Thus, to test the hypothesis that AE2 contributes to anion secretion in colon, we measured indexes of anion secretion in proximal colon of a mouse model carrying a targeted disruption of the AE2 gene (23). The results suggest that under physiological conditions anion secretion in the proximal colon is supported by both NKCC1 and, to a lesser degree, the coupled activities of AE2 and NHE1. When AE2 is absent, however, the amount of secretion supported by NKCC1 is elevated and the capacity for HCO3− secretion is reduced.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

The development of mice with targeted disruption of the Slc4a2 gene encoding the AE2 Cl−/HCO3− exchanger has been described previously (23). Heterozygous breeding pairs maintained on a mixed 129SvEv/Black Swiss background were used to generate homozygous wild-type (WT) and AE2−/− animals. AE2−/− pups exhibit multiple severe phenotypes including poor survival and growth retardation. Furthermore, AE2−/− mice are not produced in normal Mendelian ratios (11% of pups observed vs. 25% expected from heterozygous matings), and ∼50% of these pups die in the first 12 days of age (23). Nevertheless, it was possible despite these problems to obtain significant numbers of 14- to 17-day-old animals for study of proximal colon ion transport physiology. All offspring were genotyped by using the following primers: forward, 5′-CAGCACTCCTGCAGATGGTAGAG-3′; reverse, 5′-CCAAAGGTGATGGCAGGAGAC-3′; and Neo 3′, 5′-CTGACTAGGGGAGGAGTAGAAGG-3′. The forward and reverse primers were derived from codons 655–661 and 716–723, respectively, and the Neo 3′ primer is derived from the promoter for the neomycin resistance gene (23). For all studies, age-matched WT littermates were used as controls. All experimental protocols were approved by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Histological analysis and pH measurements of intestinal contents.

Segments of the intestinal tract of mice ∼18 days old (n = 3) were processed and stained with Alcian blue and periodic acid-Schiff as described previously (6). With this procedure, acidic mucins stain blue and neutral mucins stain magenta. Images were taken on a Zeiss Axioskop using an Axiocam MRc5 camera.

To determine relative differences in the pH of intestinal contents, the contents of segments of the intestinal tract (whole small intestine, cecum, and colon divided into proximal and distal halves) were mixed with 1 ml of water, and the pH was measured.

Bioelectric measurements.

Mice (14–17 days old) were euthanized by asphyxiation in 100% CO2 followed by a bilateral thoracotomy to induce pneumothorax. Mice with evidence of morbidity or poor feeding were not used in these experiments. The proximal colon was removed and placed in an oxygenated, ice-cold Ringer solution containing indomethacin (1 μM). The proximal colon was opened along the mesenteric border and the muscle layers underlying the mucosa were removed by sharp dissection prior to being mounted in standard Ussing chambers (0.1-cm2 exposed surface area). The mucosal and serosal surfaces of the colonic sections were independently bathed in 4 ml of Krebs-bicarbonate Ringer solution (in mM: 115 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3−, 0.4 KH2PO4, 2.4 K2HPO4, 1.2 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, pH 7.4) which was gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 in a gas-lift recirculation system and warmed to 37°C by use of water-jacketed reservoirs (10, 24). For anion substitution experiments, gluconate and N-[Tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl]-2-aminoethane-sulfonic acid were substituted for Cl− and HCO3−, respectively, on an equimolar basis. In addition, during HCO3− substitution experiments, the mucosal and serosal surfaces of all tissues were treated with the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor acetazolamide (100 μM) and the HCO3−-free solution gassed with 100% O2. Indomethacin (1 μM) was added to both the mucosal and serosal baths to prevent endogenous generation of prostanoids and the serosal surface was exposed to tetrodotoxin (0.1 μM) to minimize variations in the intrinsic neural tone (7, 10, 44). All tissues were pretreated with 50 μM amiloride (mucosal) to inhibit epithelial Na+ channel activity (45). Stimulation of intracellular cAMP was induced by treatment of the mucosal and serosal surfaces of the colon with 10 μM forskolin and 100 μM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX). Bumetanide (100 μM) was used to inhibit NKCC1 and 1 mM SITS was used to inhibit AE2 and SITS-sensitive NBC activities. Readings for Δ transepithelial short-circuit current (Isc) measurements were taken 15 min (for bumetanide) or 10 min (for SITS) after drug addition. NHE1 was inhibited with 1 μM 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)-amiloride (EIPA) in the serosal bath at the start of the experiment in which it was used. For all experiments, the final concentration of DMSO and ethanol (used as carriers for nonwater soluble drugs) in the bath Ringer was maintained at or below 0.1%.

An automatic voltage clamp (VCC-600, Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA) was used to measure Isc (reported as μA/cm2 tissue surface area) by utilizing calomel electrodes connected to the chamber baths by 3% agar-3 M KCl bridges, as previously described (11). The Isc was applied through 3% agar-Krebs-bicarbonate-Ringer bridges which connected Ag-AgCl electrodes to the chamber baths. A 5-mV pulse was passed across each tissue at 5-min intervals during the experiment to determine the transepithelial conductance (Gt, reported in mS/cm2 tissue surface area). The magnitude of the current deflections to the applied voltage were measured, and Gt was calculated by Ohm's law. All experiments were performed under short-circuited conditions with the serosal bath serving as ground. Data were compared by a two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test assuming equal variances. A probability value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All values are reported as means ± SE.

Microarray and PCR analyses.

RNA samples were isolated from colon of 2-wk-old AE2−/− mice and wild-type controls (n = 5 mice of each genotype). RNA extractions were performed by using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) according to the manufacturer's protocol with one extra extraction and two extra precipitation steps. Microarrays spotted with 70-mer oligonucleotides were hybridized with cDNA samples labeled with Cy3 and Cy5 fluorophores by the University of Cincinnati Genomics and Microarray Laboratory core facility, and statistical analyses of the resulting data were performed exactly as previously described (6). The data and experimental details have been deposited in GEO (#GSE19075). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on cDNA generated by reverse transcription of 4 μg of total RNA using oligo(dT) and Superscript II reverse transcriptase. The cDNA was diluted fourfold in water, and 2 μl was used in a 25-μl final reaction volume with primer concentrations of 500 nM. Primers from the indicated references were used to analyze expression of mRNAs for Slc4a3 (4), Slc4a4 (4), Slc4a5 (4), Slc4a7 (4), Slc13a1 (34), carbonic anhydrase 1 (40), carbonic anhydrase 2 (40), carbonic anhydrase 4 (40), carbonic anhydrase 13 (40), Trpv6 (47), Clca3 (8), and Kcne3 (39). A DNA Engine Opticon II (MJ Research) thermocycler and iQ SYBR Green (Bio-Rad) were used to run the reactions. Samples were run in duplicate and mean values were normalized to the expression of L32 ribosomal subunit mRNA.

Western blot analysis.

Whole tissue homogenates of proximal colons isolated from 2-wk-old WT and AE2−/− mice were used for Western blot analysis. For analysis of NKCC1 and carbonic anhydrase expression, samples were prepared by powdering in liquid nitrogen and homogenizing in 20 mM HEPES, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.2% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), and 10% glycerol containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (NaF, 50 mM; cantharidin, 20 ng/ml; Na3VO4, 0.1 mM). Isolated protein samples were boiled for 10 min to disrupt any homodimers of NKCC1, resolved by electrophoresis on a reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate 8% polyacrylamide gel, and transferred to nitrocellulose. The blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with an anti-NKCC1 antibody (T4, 1:3,000 dilution; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa), an anti-carbonic anhydrase 2 (Car2) antibody (1:500 dilution; Santa Cruz, CA; cat. no. sc-17246), or an anti-carbonic anhydrase 3 (Car3) antibody [1:5,000 dilution; generous gift of Dr. Geumsoo Kim, National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH/NHLBI)] (32). An anti-actin antibody (1:4,000 dilution; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used as a loading control. The primary antibody was followed by an horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:7,500 dilution; Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD). SuperSignal West Pico Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was used to develop chemiluminescence and autoradiography was performed. Densitometric analysis was carried out with an HP scanner and Imagequant Software (version 5.1).

For analysis of AE2 and anion exchanger isoform 3 (AE3) protein expression, proximal colons were excised from 2-wk-old WT and AE2−/− mice and rinsed in ice-cold 1× PBS (pH 7.4). The epithelial layers were separated from the muscle layers by scraping, pulverized in liquid nitrogen, and then homogenized with a glass homogenizer at 4°C in buffer containing 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 0.25% NP-40 plus protease, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (P8340 and P5726, Sigma). Total brain homogenates from WT mice were prepared in the same buffer by using a Polytron homogenizer. Immunoblots were carried out as described above, with 40 μg of colon tissue homogenates or 30 μg of brain homogenates. Membranes were probed with the SA6 antibody against COOH-terminal amino acids 1224–1237 of mouse AE2 (2, 23), the SA8 antibody against the COOH-terminal amino acids 1216–1227 of human AE3 (52), which is conserved in mouse, and anti-actin as a loading control.

RESULTS

Impaired health and survival of AE2-null mice necessitates analysis of secretory function before weaning.

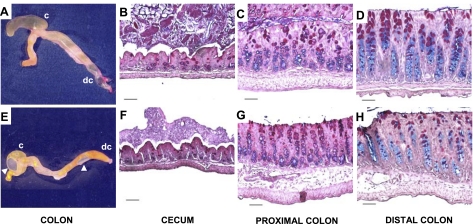

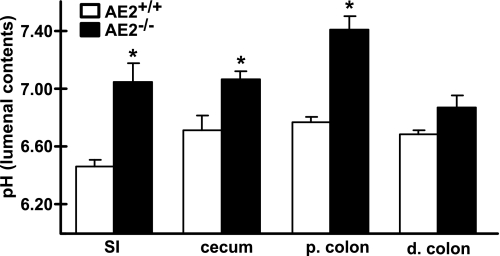

As noted previously (23), AE2-null mice exhibited poor survival, growth retardation, and evidence of dehydration. Although they did not exhibit overt diarrhea (data not shown), the contents of the ceca and colons of AE2−/− mice often appeared to have greater fluid content with numerous gas bubbles than that of WT mice (Fig. 1, A and E). This was not a consistent feature, however, and fecal pellets can form in distal colon of AE2-null mice. Despite their small size and poor health, small intestine (data not shown), cecum, and colon of AE2−/− mice (Fig. 1, F–H) appeared relatively normal histologically compared with WT tissues (Fig. 1, B–D), although there was a possible reduction in the number of mucous cells in distal colon of some AE2 mutants (compare Fig. 2, D and H). pH of the luminal contents of AE2−/− small intestine, cecum, and proximal colon was significantly elevated relative to WT controls (Fig. 2) and was slightly, but not significantly, elevated in distal colon. Because few AE2−/− pups survive to weaning, studies of secretory function in the proximal colon were confined to pups between 14 and 17 days of age. At the time of euthanasia, null mutant mice exhibited variable feeding rates (as evidenced by the intestinal contents); however, all AE2−/− pups used for these studies were active and appeared to be ingesting solid food.

Fig. 1.

Gross anatomy and histology of cecum and colon. Photographs of cecum and colon from wild-type (WT; A) and AE2−/− (E) mice. Note abnormal morphology of AE2−/− cecum (E), which tended to be less elongated and to have greater fluid content. Arrows in E indicate presence of gas bubbles in AE2−/− cecum and colon. Histological analyses of Alcian blue and periodic acid-Schiff-stained sections of cecum, proximal colon, and distal colon of WT (B, C, and D, respectively) and AE2-null (F, G, and H, respectively) mice revealed no significant differences. Goblet cells containing neutral mucins appear magenta whereas goblet cells containing sialomucins appear blue. Scale bars represent 50 μm.

Fig. 2.

pH measurements of intestinal tract contents. The contents of the small intestine (SI), cecum, proximal (p.) colon, and distal (d.) colon from 17- to 18-day-old mice (n = 3 each genotype) were suspended in water and the pH was measured. AE2−/− small intestine, cecum, and proximal colon had significantly more alkaline contents compared with WT controls (*P < 0.05).

In the experiments below, segments of proximal colon were mounted in Ussing chambers, and both basal and cAMP-stimulated anion secretion was analyzed by using solutions containing Cl− and HCO3−, Cl− alone, or HCO3− alone. To assess the relative contributions of basolateral transport activities that are thought to support cAMP-stimulated anion secretion, bumetanide was used to inhibit the NKCC1 Na-K-2Cl cotransporter, followed by the stilbene disulfonate SITS, which is a relatively nonspecific inhibitor of Cl− and HCO3− transporters such as AE2 and NBCe1 (Slc4a4); in some experiments, EIPA pretreatment was used to inhibit NHE1-mediated Na+/H+ exchange. Transepithelial conductance, a measure of paracellular permeability, did not differ significantly between the AE2−/− and WT colons in any of these experiments.

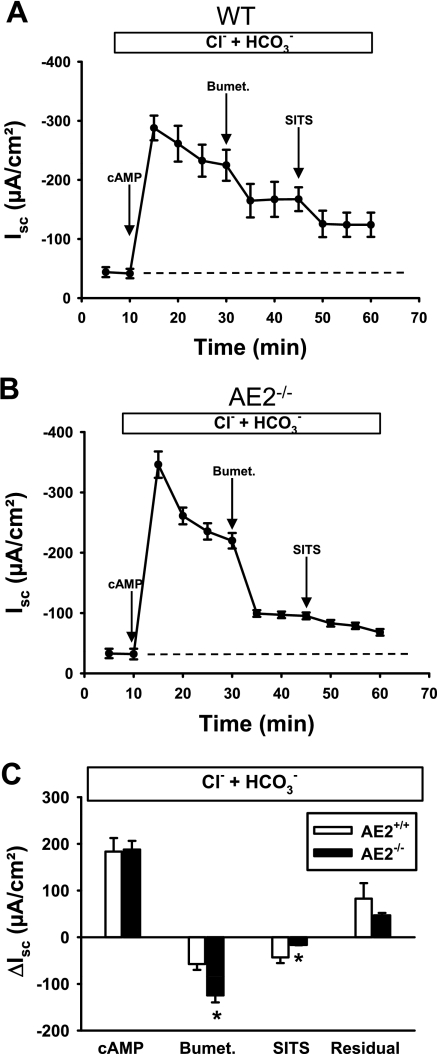

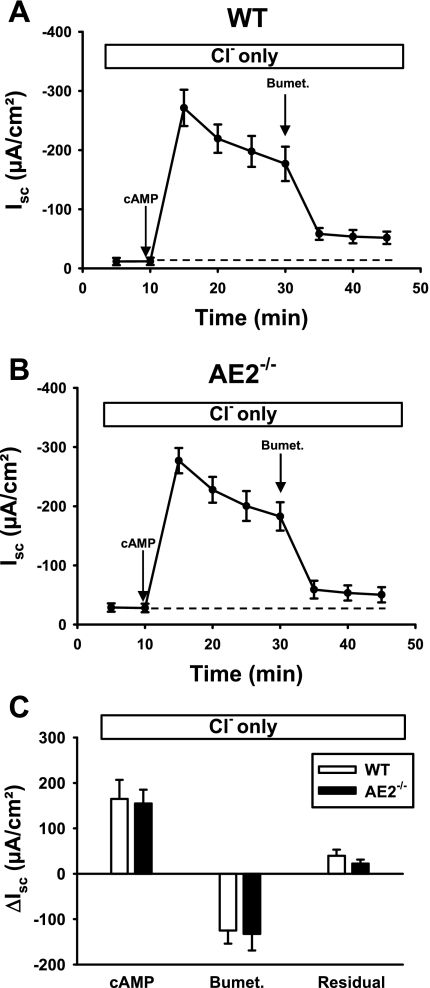

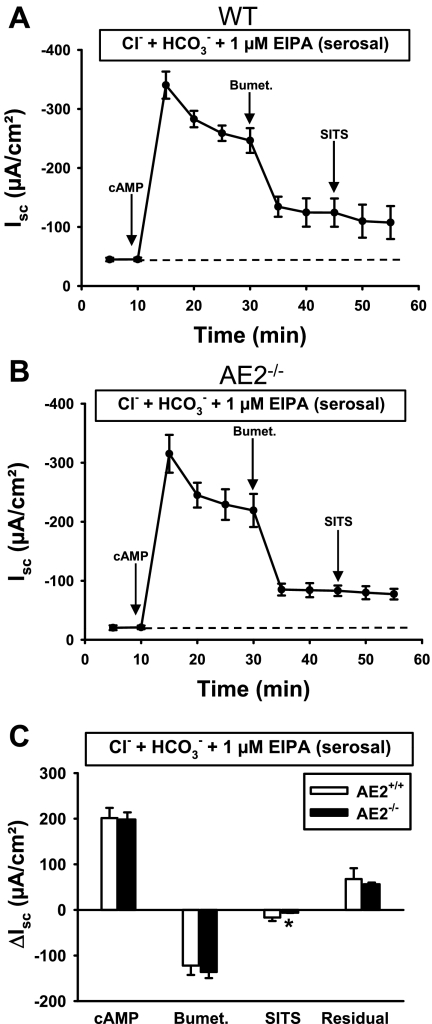

Anion secretion in AE2-null proximal colon exhibits greater dependence on NKCC1.

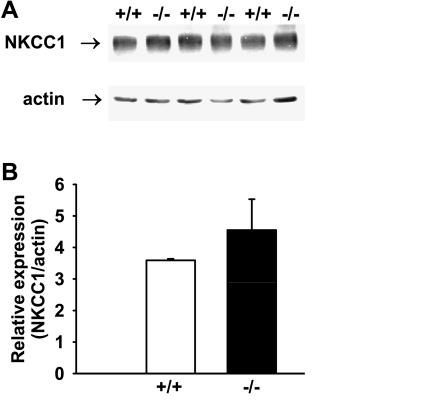

Basal anion secretion in the presence of physiological concentrations of Cl− and HCO3− did not differ significantly between WT (Fig. 3A) and AE2−/− (Fig. 3B) proximal colons. Addition of a cocktail of 10 μM forskolin and 100 μM IBMX to increase intracellular cAMP resulted in rapid stimulation of the Isc in both tissues, followed by a decline to plateau currents (measured 20 min after cAMP stimulation) of similar magnitude in both genotypes. However, AE2−/− proximal colons exhibited a more rapid decline in the Isc after maximal stimulation (compare Fig. 3, A vs. B) and addition of bumetanide to the serosal bath caused a greater decrease in the Isc in AE2−/− proximal colon compared with WT tissue (Fig. 3C), indicating approximately twofold greater dependence on NKCC1-mediated Na-K-2Cl cotransport in AE2-null colon. Immunoblot analysis of NKCC1 revealed a modest, though nonsignificant, increase in NKCC1 protein levels in AE2−/− colon (Fig. 4), suggesting that the increased activity was not dependent on expression changes. Subsequent addition of SITS to the serosal bath reduced Isc in both WT and AE2−/− proximal colon (SITS, Fig. 3C); however, the decrease in Isc in response to addition of SITS was significantly less in AE2−/− colon, consistent with the absence of AE2. The differences in the mean values of residual Isc, i.e., the portion of the cAMP-stimulated Isc remaining after treatment with bumetanide and SITS, were not statistically significant; however, when expressed as a percentage of plateau current (41.1 ± 5.2% in WT, 25.0 ± 1.6% in AE2-null), the reduction in residual current in AE2−/− colon was statistically significant.

Fig. 3.

cAMP-stimulated anion secretion in AE2−/− proximal colon is more dependent on NKCC1 than in WT tissue. Tissues were mounted in Ussing chambers and bathed in Ringer solution containing Cl− and HCO3− (indicated in box above each panel), and changes in short circuit currents (Isc) were measured in WT (A) and AE2−/− (B) proximal colons (n = 4 each genotype) in response to sequential treatment with forskolin/IBMX (cAMP stimulation), bumetanide, and 4-acetoamido-4′-isothiocyanato-2–2′-stilbene disulfonic acid (SITS). Labeled arrows indicate time of drug addition; dashed line indicates baseline Isc. C: summary of data in A and B, showing ΔIsc responses to cAMP (plateau current 20 min after cAMP stimulation), reductions in Isc following treatment with bumetanide and SITS (indicated by negative currents), and residual currents. *Significantly different from WT control for same treatment.

Fig. 4.

Expression of NKCC1 is not significantly changed in AE2−/− proximal colon. A: NKCC1 protein expression was not different between WT (+/+) and AE2−/− (−/−) proximal colon by Western blot analysis using 28 μg of whole protein lysate. B: quantification of NKCC1 expression relative to actin expression for WT and AE2−/− proximal colon (n = 3 each genotype). AE2−/− proximal colon exhibited a nonsignificant increase (29%) in NKCC1 expression.

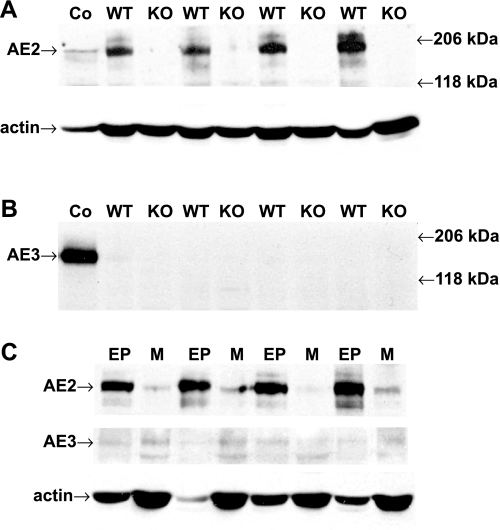

Upregulation of an alternative basolateral Cl−/HCO3− exchanger has the potential to provide an additional Cl− uptake mechanism that might partially compensate for the loss of AE2. To assess this possibility, proximal colon samples were analyzed to confirm the loss of AE2 protein expression and to determine whether expression of AE3 (Slc4a3), which is expressed at significant levels in basolateral membranes in human colon (3), but at only low levels in rodent colon (33), was upregulated in AE2−/− colon. As expected, AE2 protein expression was absent in colon epithelial samples from AE2−/− mice (Fig. 5A). In contrast to the high levels of AE3 expression in brain of WT mice, AE3 was not expressed at detectable levels in colonic epithelium of either WT or AE2−/− mice (Fig. 5B). Analysis of isolated epithelial and muscle layers from WT colon revealed AE2 expression primarily in the epithelium, with possible low levels of AE3 in the muscle layer (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

AE3 protein expression is not altered in AE2−/− colonic epithelium. Homogenates of epithelial and muscle layers from proximal colons of juvenile WT and AE2−/− (KO) mice were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-AE2 and anti-AE3 antibodies. A: AE2 protein expression was lost in colonic epithelium of AE2−/− mice whereas robust expression was observed in WT samples [40 μg/lane, n = 4 mice of each genotype; the control (Co) is WT brain homogenate (30 μg/lane)]. B: AE3 protein expression was below the limits of detection in WT colonic epithelium and was not increased in AE2−/− colonic epithelium; control total brain homogenates showed robust expression of full-length AE3. C: immunoblot analysis of epithelial (EP) and muscle (M) layers from proximal colons of juvenile WT mice revealed that AE2 protein expression was largely restricted to the colonic epithelium (n = 4). In contrast, AE3 protein expression was barely detectable in epithelial and muscle samples, even after relatively long exposure times.

Anion secretion in wild-type colon can switch rapidly to dependence on NKCC1.

Differences in inhibitor sensitivity of the cAMP-stimulated Isc indicated that anion secretion in the AE2−/− proximal colon is dominated by NKCC1-dependent Cl− secretion and that this activity can largely compensate for the loss of AE2. This could result from either long-term adaptation in AE2-null colon, with greater reliance on NKCC1, or flexibility in the use of these basolateral Cl−-uptake mechanisms. To distinguish between these possibilities, experiments were performed in the absence of HCO3− (Cl− alone). To minimize the contribution of endogenously generated HCO3−, these experiments were performed in the presence of the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor acetazolamide and solutions were gassed with 100% O2. Under these conditions, AE2 activity is eliminated (because of its dependence on HCO3−) and anion secretion is largely dependent on serosal Cl−. As shown in Fig. 6, removal of HCO3− (and CO2) from the bathing solutions, leaving Cl− as the only CFTR-permeant anion, led to virtually identical Isc responses in AE2−/− and WT proximal colons following stimulation with cAMP. Peak currents, plateau currents, and bumetanide-sensitive currents were similar in both genotypes, and there were no significant differences in the residual cAMP-stimulated Isc. Compared with the physiological Ringer solution results (see Fig. 3, where the bumetanide-sensitive component was 34.6 ± 8.2% of the plateau current in WT and 65.9 ± 2.0% in AE2-null), WT colon analyzed in solutions containing only Cl− exhibited increased sensitivity to bumetanide, with inhibition of the Isc similar to that in AE2−/− colon (see Fig. 6, where the bumetanide-sensitive component was 77.5 ± 3.5% of the plateau current in WT and 81.9 ± 10.3% in AE2-null).

Fig. 6.

Cl−-dependent Isc responses to cAMP-stimulation and bumetanide are the same in WT and AE2−/− proximal colon. Tissues were mounted in Ussing chambers, bathed in HCO3−-free Ringer solution containing only Cl− as a transported anion (indicated in box above each panel), and changes in Isc were measured in WT (A) and AE2−/− (B) proximal colons (n = 4 each genotype) in response to cAMP-stimulation and bumetanide. Labeled arrows indicate time of drug addition; dashed line indicates the baseline Isc. C: summary of data in A and B, showing ΔIsc responses to cAMP (plateau current 20 min after cAMP-stimulation), reductions in Isc following treatment with bumetanide, and residual currents.

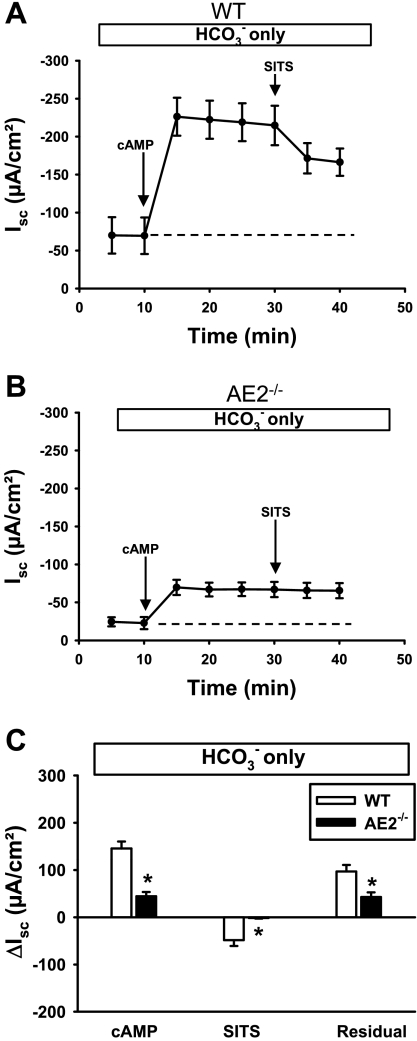

Loss of AE2 leads to a reduction in HCO3−-dependent anion secretion.

The above experiments showed that secretory function was essentially the same in AE2−/− and WT proximal colons when analyzed in Ringer solution containing only Cl−. In contrast, AE2−/− proximal colon exhibited a marked reduction in cAMP-stimulated Isc when HCO3− was the only CFTR-permeant anion (Fig. 7, B and C). Consistent with the apparent decrease in HCO3− secretory capacity in AE2−/− proximal colon, application of SITS to the serosal bath decreased cAMP-stimulated Isc in WT but had no effect on Isc in AE2−/− colon. An impaired ability of AE2−/− colon to secrete HCO3− under these conditions was further indicated by a significant decrease in the residual Isc in AE2−/− colon analyzed in HCO3−-only Ringer solution (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

HCO3−-dependent Isc responses to cAMP-stimulation and SITS are reduced in AE2−/− proximal colon relative to WT controls. Tissues were mounted in Ussing chambers and bathed in Cl−-free Ringer solution containing only HCO3− as a transported anion (indicated in box above each panel), and changes in Isc were measured in WT (A) and AE2−/− (B) proximal colons (n = 4 each genotype) in response to cAMP stimulation and SITS. Labeled arrows indicate time of drug addition; dashed line indicates the baseline Isc. C: summary of data in A and B, showing ΔIsc responses to cAMP (plateau current 20 min after cAMP stimulation), reductions in Isc following treatment with SITS, and residual currents. *Significantly different from WT control for same treatment.

To further examine the apparent defect in HCO3− secretion, WT and AE2−/− proximal colons in HCO3−-only Ringer solution were pretreated with acetazolamide (Fig. 8) to inhibit the contribution of carbonic anhydrase activity to the cAMP-induced Isc. In WT colon, acetazolamide pretreatment caused a modest reduction in both maximal and residual cAMP-stimulated Isc when compared with tissues analyzed in the absence of acetazolamide (compare Figs. 7A and 8A), and the SITS-sensitive current increased from ∼33% to ∼50% of the plateau current. In contrast, pretreatment of AE2−/− colon tissue with acetazolamide had little effect on cAMP-induced Isc and there was no response to SITS (compare Figs. 7B and 8B).

Fig. 8.

Acetazolamide has no effect on HCO3−-dependent Isc responses to cAMP-stimulation and SITS treatment in AE2−/− proximal colon. Tissues were mounted in Ussing chambers, bathed in Cl−-free Ringer solution containing only HCO3− as a transported anion (indicated in box above each panel), and treated with acetazolamide to inhibit carbonic anhydrase. Changes in Isc were measured in WT (A) and AE2−/− (B) proximal colons (n = 4 each genotype) in response to cAMP stimulation and SITS. Labeled arrows indicate time of drug addition; dashed line indicates the baseline Isc. C: summary of data in A and B, showing ΔIsc responses to cAMP (plateau current 20 min after cAMP stimulation), reductions in Isc following treatment with SITS, and residual currents. *Significantly different from WT control for same treatment.

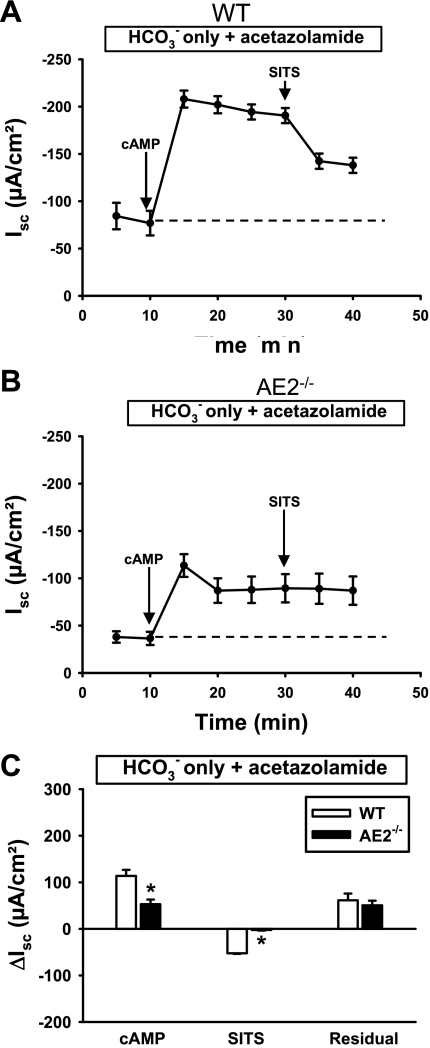

Inhibition of NHE1 causes a switch to NKCC1-supported secretion.

Previous studies are consistent with the hypothesis that coupling of AE2 and NHE1 at the basolateral membrane may contribute to anion secretion in epithelial tissues (17, 41). Therefore, we tested whether the pharmacological properties of the cAMP-stimulated Isc response in physiological Ringer differed between WT and AE2−/− proximal colon during inhibition of NHE1 with 1 μM EIPA. Similar to findings in the absence of HCO3− (Cl− only, see Fig. 6), no significant differences in cAMP-induced Isc responses were observed between WT and AE2−/− proximal colon (Fig. 9). Importantly, there was no difference in the bumetanide-sensitive Isc between WT and AE2−/− proximal colon during inhibition of NHE1, although AE2−/− proximal colon exhibited a significant decrease in SITS-sensitive current (Fig. 9C). These changes resulted from a greater inhibition of the Isc with bumetanide in the WT rather than a decrease in the response of AE2−/− proximal colon (compare with results in Fig. 3 with physiological Ringer solution). Finally, during inhibition of NHE1, there was no significant difference in the residual Isc between WT and AE2−/− proximal colons.

Fig. 9.

Inhibition of the NHE1 Na+/H+ exchanger results in similar Isc responses to cAMP, bumetanide, and SITS in WT and AE2−/− proximal colon. Tissues were mounted in Ussing chambers and bathed in Ringer solution containing Cl− and HCO3−, with EIPA in the serosal solution to inhibit NHE1 (indicated in box above each panel). Changes in Isc were measured in WT (A) and AE2−/− (B) proximal colons (n = 4 each genotype) in response to cAMP stimulation, bumetanide, and SITS. Labeled arrows indicate time of drug addition; dashed line indicates baseline Isc. C: summary of data in A and B, showing ΔIsc responses to cAMP (plateau current 20 min after cAMP-stimulation), reductions in Isc following treatment with bumetanide and SITS, and residual currents. *Significantly different from WT control for same treatment.

Impaired HCO3− secretion is not due to reduced expression of HCO3− transporter or carbonic anhydrase mRNAs.

On the basis of our findings of sharply reduced HCO3−-supported secretion in AE2-null proximal colons, we performed microarray analyses of colon RNA from AE2−/− and WT mice to determine whether there was evidence of transcriptional remodeling of ion transport processes. We were particularly interested in whether the expression of Na+/HCO3− cotransporters or other proteins that contribute to HCO3− secretion was altered. The data indicated that mRNA expression was not altered for any of the possible basolateral Na+/HCO3− cotransporters represented on the microarray, although expression of AE2 (as expected), carbonic anhydrase 3, and several ion channels or transporters appeared to be significantly changed (Table 1). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of RNA from AE2−/− and WT colons confirmed the increased expression of mRNA encoding the Trpv6 cation channel and reductions in expression of the Slc13a1 sodium-sulfate cotransporter, the Kcne3 potassium channel accessory subunit, and the Clca3 putative calcium activated Cl− channel (Table 2). However, the sharp reduction in carbonic anhydrase 3 expression was not confirmed. The mean values for NBCe1 and NBCn1 Na+/HCO3− cotransporter mRNA expression, measured by PCR analysis, were modestly reduced, but the differences were not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Microarray analysis of carbonic anhydrase and ion transporter mRNA expression in colons of wild-type and AE2-null mice

| Symbol | Name | Fold Change | P < |

|---|---|---|---|

| Car1 | carbonic anhydrase 1 | −1.33 | NS |

| Car2 | carbonic anhydrase 2 | −1.24 | NS |

| Car3 | carbonic anhydrase 3 | −8.53 | 0.001 |

| Car4 | carbonic anhydrase 4 | −1.04 | NS |

| Car13 | carbonic anhydrase 13 | −1.08 | NS |

| Clca3 | chloride channel, calcium activated 3 | −2.92 | 0.001 |

| Cftr | cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator | 1.16 | NS |

| Slc4a1 | AE1 anion exchanger | −1.22 | NS |

| Slc4a2 | AE2 anion exchanger | −7.20 | 0.00001 |

| Slc4a4 | NBCe1 Na-HCO3 cotransporter | −1.08 | NS |

| Slc4a5 | NBCe2 Na-HCO3 cotransporter | 1.02 | NS |

| Slc4a7 | NBCn1 Na-HCO3 cotransporter | 1.10 | NS |

| Slc4a10 | NBCn2 Na-HCO3 cotransporter | 1.15 | NS |

| Slc12a2 | NKCC1, Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransporter | 1.08 | NS |

| Slc13a1 | sodium sulfate symporter 1 | −1.70 | 0.001 |

| Kcne3 | KCNE3 voltage-gated potassium channel | −1.83 | 0.01 |

| Trpv6 | transient receptor potential cation channel 6 | 2.83 | 0.03 |

Microarray analyses were performed to compare gene expression profiles in whole colon of wild-type and AE2−/− mice (n = 5 mice of each genotype; see materials and methods). As shown, most of the genes associated with HCO3− secretion were unaffected in mice lacking AE2, although a few ion transporter genes were affected. Changes in other genes were also observed and are included in the complete data set submitted to GEO. Expression data are presented as fold changes, with negative values indicating downregulation in AE2−/− samples. NS, nonsignificant.

Table 2.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of carbonic anhydrase and ion transporter mRNA expression in colons of wild-type and AE2-null mice

| Symbol | Name | WT | KO | P < |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Car1 | Carbonic anhydrase 1 | 1.00 ± 0.11 | 1.33 ± 0.16 | NS |

| Car2 | Carbonic anhydrase 2 | 1.00 ± 0.08 | 0.97 ± 0.07 | NS |

| Car3 | carbonic anhydrase 3 | 1.00 ± 0.45 | 0.57 ± 0.08 | NS |

| Car4 | carbonic anhydrase 4 | 1.00 ± 0.37 | 1.06 ± 0.36 | NS |

| Car13 | carbonic anhydrase 13 | 1.00 ± 0.03 | 1.00 ± 0.16 | NS |

| Clca3 | chloride channel, calcium activated 3 | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 0.72 ± 0.04 | 4×10−3 |

| Slc4a3 | AE3 anion exchanger | 1.00 ± 0.19 | 1.36 ± 0.39 | NS |

| Slc4a4 | NBCe1 Na-HCO3 cotransporter | 1.00 ± 0.21 | 0.69 ± 0.12 | NS |

| Slc4a5 | NBCe2 Na-HCO3 cotransporter | 1.00 ± 0.05 | 1.01 ± 0.13 | NS |

| Slc4a7 | NBCn1 Na-HCO3 cotransporter | 1.00 ± 0.22 | 0.76 ± 0.11 | NS |

| Slc13a1 | sodium sulfate symporter 1 | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 1×10−5 |

| Kcne3 | KCNE3 voltage-gated potassium channel | 1.00 ± 0.09 | 0.55 ± 0.03 | 2×10−3 |

| Trpv6 | transient receptor potential cation channel 6 | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 4.11 ± 0.28 | 7×10−7 |

Real-time PCR analyses were performed (n = 5 mice of each genotype; see materials and methods) to confirm relative expression levels of carbonic anhydrase and ion transporter mRNAs identified by microarray analysis (Table 1) of colon RNA samples from wild-type (WT) and AE2−/− (KO) mice. Note that the sharp downregulation of Car3 mRNA seen in microarray analyses was not confirmed here and that Car3 protein levels (Fig. 10) were unchanged. For each mRNA, expression levels were normalized to the expression of mRNA for the L32 ribosomal subunit, the level of expression in wild-type samples was set to 1.0, and expression levels for AE2−/− mice were normalized to wild-type values. P < 0.05, by a Student's t-test, was considered significant.

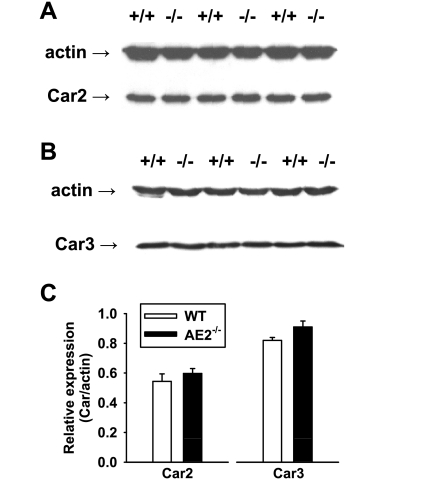

Since AE2−/− colon exhibited a reduced capacity for HCO3− secretion and an apparent reduction/loss of acetazolamide sensitivity, decreased activity of carbonic anhydrases could contribute to the deficit in electrogenic HCO3− secretion. Thus we performed immunoblot analysis to assess protein expression of carbonic anhydrase 3 and carbonic anhydrase 2, which has been shown to interact with AE2 to form a transport metabolon (25, 46). Consistent with the microarray and RT-PCR data, carbonic anhydrase 2 protein levels were not altered in AE2−/− proximal colons (Fig. 10, A and C). Furthermore, there were no changes in carbonic anhydrase 3 expression (Fig. 10, B and C).

Fig. 10.

Expression of carbonic anhydrase isoforms 2 and 3 are not changed in AE2−/− proximal colon. Whole colon homogenates (20 μg/lane) from WT and AE2−/− mice were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-Car2 (A) and anti-Car3 (B) antibodies, with actin as a loading control. C: quantification of Car2 and Car3 expression relative to actin expression for WT and AE2−/− proximal colon (n = 3 for each genotype) revealed no significant differences in expression for either Car2 or Car3.

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to determine whether the basolateral AE2 Cl−/HCO3− exchanger is involved in normal anion secretion in the proximal colon. This issue has been difficult to address directly because specific inhibitors of AE2 are not available and stilbene disulfonate inhibitors that affect AE2 also inhibit other HCO3− transporters (43). Use of the AE2-null mouse model circumvents pharmacological issues; however, because of diminishing health and early death of null mutants (23), the studies were performed using preweaning (juvenile) mice (14–17 days old). This provided a window of time in which the null mutant mice were quite active and the proximal colon exhibited normal histology. Analysis of anion currents in proximal colon, the site of highest AE2 expression in the intestinal tract (33, 36), revealed robust cAMP-stimulated anion secretion in AE2−/− tissue; however, the currents differed in several respects from those of WT controls.

A major finding was that genetic ablation of AE2, or the use of conditions that block AE2 activity, caused a shift to greater NKCC1-supported anion secretion. Relative to WT colon, the magnitude of cAMP-stimulated anion secretion in physiological Ringer solution was not diminished in the AE2−/− proximal colon, indicating that it retains normal driving forces for anion secretion under conditions in which Cl− is present in the perfusion solutions. However, AE2−/− tissue had a much greater bumetanide-sensitive Isc, which corresponds to NKCC1-supported Cl− secretion. Furthermore, the SITS-sensitive current, corresponding to both AE2-supported Cl− secretion (in WT) and NBC-supported HCO3− secretion, was significantly reduced. The finding of altered bumetanide-sensitive currents raised the possibility that NKCC1 expression was upregulated as an adaptive response to the loss of AE2; however, significant changes in NKCC1 mRNA (Table 1) and protein expression were not observed in AE2−/− proximal colons. Rather, two observations showed that a switch to increased NKCC1-supported secretion can occur rapidly and does not require long-term adaptation. First, Isc measurements performed in solutions containing only Cl− as a CFTR-permeant anion revealed increased bumetanide-sensitive anion secretion in WT colon that was virtually identical to the response in AE2−/− colon. In this experiment, the absence of CO2/HCO3− would prevent both AE2 activity and mechanisms of HCO3− secretion dependent either upon uptake of HCO3− from the serosal solution (NBC activities) or upon intracellular generation of HCO3− from CO2 and H2O. Second, inhibition of NHE1 in physiological Ringer, which would inhibit the coupled activities of AE2 and NHE1, increased the magnitude of the bumetanide-sensitive Isc and reduced the SITS-sensitive Isc in WT proximal colon, a response very similar to that in AE2−/− colon. The fact that EIPA inhibition did not appreciably alter anion secretion characteristics in the AE2−/− proximal colon also suggests that NHE1 activity has little effect on cAMP-stimulated anion secretion in the absence of AE2. Thus these studies suggest that NKCC1 activity can be rapidly increased in the WT proximal colon to compensate for a deficiency in anion secretion supported by the coupled activities of AE2 and NHE1.

The mechanism by which NKCC1 activity is increased in cAMP-stimulated AE2-null colon relative to WT colon is unclear but could involve acute changes in phosphorylation and/or surface expression of NKCC1, both of which are known to regulate NKCC1 activity in cultured secretory cells (14, 15). It has been suggested that regulation of NKCC1 activity over time periods of seconds to minutes may be mediated by phosphorylation events and that regulation over longer time periods may occur via changes in surface expression (15). Previous studies have shown that cAMP-stimulation of secretion by treatment with forskolin caused no changes in NKCC1 surface expression in human colonic crypts (42) but did increase phosphorylation of NKCC1 in shark rectal glands (19). This suggests that changes in phosphorylation could be involved in the differential regulation of NKCC1 activity observed in the present study following stimulation with forskolin. It is likely that changes in intracellular ion concentrations also play a role, since loss of AE2-mediated Cl− uptake, particularly during stimulated secretion, would likely lead to a reduction in intracellular Cl−. Reduced Cl− would be expected to increase the ionic driving force for Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport and has also been shown to activate NKCC1 via increased phosphorylation (28).

Coupling of AE2 and NHE1 at the basolateral membrane has been previously proposed as a Cl− uptake mechanism that operates in parallel with NKCC1 in support of Cl− secretion. In Calu-3 cells, the coupling of AE2 and NHE1 activities was deduced from their presence on the basolateral membrane and sensitivity of the observed activities to transport inhibitors (12, 16, 35). Parotid acinar cells have also been shown to utilize basolateral Cl−/HCO3− exchange and Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport for Cl− loading during stimulated secretion (48). Salivary secretion rates were reduced in NKCC1-null mice; however, the acinar cells exhibited upregulation of Cl−/HCO3− exchange and AE2 mRNA expression (17), suggesting that AE2 functions as an alternative Cl− uptake mechanism in that tissue. Salivary secretion rates were also reduced in NHE1-null mice (41), consistent with the suggestion that the coupled activities of NHE1 and AE2 provide a mechanism for basolateral uptake of Cl− (and Na+) during stimulated secretion (17). The results of the present study provide the first direct evidence that coupling of basolateral AE2 and NHE1 activities also contributes to anion secretion in juvenile murine proximal colon. It should be noted, however, that this activity is less than that of NKCC1, which is the predominant basolateral mechanism supporting anion secretion, and that a substantial residual current is supported by additional mechanisms that are insensitive to all of the inhibitors used in these experiments.

A major stimulus for compensation via increased NKCC1 activity in AE2-null colon may relate to the functions of NKCC1 and AE2 (coupled with NHE1) in the maintenance of cell volume. Both transport processes mediate regulatory volume increase (1, 31, 38), which is likely initiated by reductions in cell volume during activation of CFTR (21, 49). In the case of coupled Na+/H+ and Cl−/HCO3− exchange, previous studies indicated that decreased cell volume activates Na+/H+ exchange, leading to cellular alkalinization, which in turn activates AE2 (29, 31). Inhibition of NHE1 would prevent cell shrinkage-induced cellular alkalinization and subsequent activation of AE2 for regulatory volume increase, thus leading to a greater reliance on NKCC1 activity to sustain cell volume and support anion secretion. Cell shrinkage, in addition to reduced intracellular Cl− concentrations discussed earlier, has been shown to stimulate basolateral NKCC1 activity via increased phosphorylation of the protein (28).

Besides AE2, the only transporter we are aware of that might provide both Cl−-uptake and HCO3−-extrusion capabilities across basolateral membranes of colonic epithelium is the AE3 Cl−/HCO3− exchanger. AE3 is expressed at only low levels in rat intestine and colon (33); however, in human intestine and colon it was expressed at easily detected levels in basolateral membranes, with highest levels in colon (3). However, AE3 was not detected in protein samples prepared by using whole colon from wild-type or AE2−/− mice. Further analysis using muscle and epithelial layers of wild-type colon and long exposure times during immunoblotting yielded only trace bands of the correct size, with higher levels in muscle, thus negating a major role for AE3 as an epithelial Cl−/HCO3− exchanger in mouse colon.

An unexpected finding was the reduction in the capacity of the isolated AE2−/− proximal colon to utilize HCO3− in support of cAMP-stimulated anion secretion. In HCO3−-only Ringer, pharmacological inhibitor responses indicated a deficit in the contributions of both Na+/HCO3− cotransport and carbonic anhydrase to cAMP-stimulated anion secretion in the AE2−/− colon. Both SITS-sensitive and SITS-insensitive components of the cAMP-induced ΔIsc were significantly reduced in AE2−/− compared with WT colon (Fig. 7), indicating reduced activities of two or more Na+/HCO3− cotransporters. When treated with acetazolamide in HCO3− only Ringer solution (Fig. 8), the Isc response to cAMP stimulation in WT colon was reduced whereas the response by AE2−/− proximal colon was unchanged, indicating a deficit in the ability of the AE2−/− proximal colon to generate HCO3− via carbonic anhydrase activity. Thus processes responsible for HCO3− availability and support of cAMP-stimulated anion secretion are apparently reduced in the AE2−/− colonic epithelium. The mechanistic basis for this observation is unclear. Microarray and quantitative PCR analyses, in combination with immunoblot analysis of carbonic anhydrase isoforms 2 and 3, provided no indication that loss of AE2 leads to changes in Na+/HCO3− cotransporter or carbonic anhydrase expression that would be consistent with the observed deficits. However, in addition to serving as a Cl− uptake mechanism, AE2 is the only known transporter that can extrude significant amounts of HCO3− across the basolateral membrane of mouse colonic epithelium under normal conditions. The increased pH of luminal contents throughout the intestinal tract of AE2-null mice is consistent with a proposed role for AE2 in HCO3− reclamation in WT mice, with H+ extrusion via the apical NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger, subsequent reductions in luminal HCO3−, and extrusion of intracellular HCO3− via basolateral AE2. It is possible, therefore, that changes in cellular HCO3− content and intracellular pH in AE2-null colonocytes lead to reductions in both Na+/HCO3− cotransporter-mediated HCO3− uptake and generation of HCO3− via carbonic anhydrase activity. An additional possibility, which is not mutually exclusive, is that the HCO3−:Na+ stoichiometry of NBCe1 switches from 2:1 to 3:1, which would allow it to mediate HCO3− efflux, as occurs in the renal proximal tubule, rather than HCO3− uptake. It has been shown that the difference in stoichiometry is dependent on the phosphorylation status of a Ser residue near the carboxy terminus, leading to the suggestion that it may provide a mechanism for regulating the direction of HCO3− flux through NBCe1 (26). Although a change in the ion stoichiometry of NBCe1 in the AE2-null proximal colon could explain the apparent loss of Na+/HCO3− cotransport activity in support of secretion, such a switch has not been reported previously.

In summary, these studies show that the loss of AE2 leads to a significant increase in the bumetanide-sensitive component of cAMP-induced anion secretion and a reduction in the SITS-sensitive component, with a similar shift occurring in WT proximal colon in response to inhibition of NHE1. These observations support a model for basolateral uptake of Cl− during cAMP-stimulated anion secretion in which a major component consists of NKCC1-mediated Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport and a lesser component consists of the coupled activities of AE2 and NHE1, with the accompanying Na+ contributing to maintenance of the membrane potential. Additional transport mechanisms mediating HCO3− uptake, likely consisting of both SITS-sensitive and SITS-insensitive Na+/HCO3− cotransporter activities, are also involved.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK050594 and HL061974 (G. E. Shull), DK43495 and DK34854 (S. L. Alper), and an American Gastroenterological Association Foundation Research Scholar Award (L. R. Gawenis).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Lane Clarke, University of Missouri-Columbia, for useful suggestions and critical reading of this manuscript, and Dr. Geumsoo Kim (NIH/NHLBI) for generous donation of the anti-Car3 antibody.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander RT, Grinstein S. Na+/H+ exchangers and the regulation of volume. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 187: 159–167, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alper SL, Rossmann H, Wilhelm S, Stuart-Tilley AK, Shmukler BE, Seidler U. Expression of AE2 anion exchanger in mouse intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 277: G321–G332, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alrefai WA, Tyagi S, Nazir TM, Barakat J, Anwar SS, Hadjiagapiou C, Bavishi D, Sahi J, Malik P, Goldstein J, Layden TJ, Ramaswamy K, Dudeja PK. Human intestinal anion exchanger isoforms: expression, distribution, and membrane localization. Biochim Biophys Acta 1511: 17–27, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarez BV, Kieller DM, Quon AL, Robertson M, Casey JR. Cardiac hypertrophy in anion exchanger 1-null mutant mice with severe hemolytic anemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1301–H1312, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachmann O, Reichelt D, Tuo B, Manns MP, Seidler U. Carbachol increases Na+-HCO3− cotransport activity in murine colonic crypts in a M3-, Ca2+/calmodulin-, and PKC-dependent manner. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 291: G650–G657, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford EM, Sartor MA, Gawenis LR, Clarke LL, Shull GE. Reduced NHE3-mediated Na+ absorption increases survival and decreases the incidence of intestinal obstructions in cystic fibrosis mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 296: G886–G898, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bukhave K, Rask-Madsen J, Hogan DL, Koss MA, Isenberg JI. Proximal duodenal prostaglandin E2 release and mucosal bicarbonate secretion are altered in patients with duodenal ulcer. Gastroenterology 99: 951–955, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busse PJ, Zhang TF, Srivastava K, Lin BP, Schofield B, Sealfon SC, Li XM. Chronic exposure to TNF-alpha increases airway mucus gene expression in vivo. J Allergy Clin Immunol 116: 1256–1263, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke LL, Grubb BR, Gabriel SE, Smithies O, Koller BH, Boucher RC. Defective epithelial chloride transport in a gene-targeted mouse model of cystic fibrosis. Science 257: 1125–1128, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke LL, Harline MC. CFTR is required for cAMP inhibition of intestinal Na+ absorption in a cystic fibrosis mouse model. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 270: G259–G267, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke LL, Harline MC. Dual role of CFTR in cAMP-stimulated HCO3− secretion across murine duodenum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 274: G718–G726, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuthbert AW, Supuran CT, MacVinish LJ. Bicarbonate-dependent chloride secretion in Calu-3 epithelia in response to 7,8-benzoquinoline. J Physiol 551: 79–92, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dagher PC, Rho JI, Charney AN. Mechanism of bicarbonate secretion in rat (Rattus rattus) colon. Comp Biochem Physiol 105: 43–48, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darman RB, Forbush B. A regulatory locus of phosphorylation in the N terminus of the Na-K-Cl cotransporter, NKCC1. J Biol Chem 277: 37542–37550, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Castillo IC, Fedor-Chaiken M, Song JC, Starlinger V, Yoo J, Matlin KS, Matthews JB. Dynamic regulation of Na+-K+-2Cl− surface expression by PCK-ε in Cl−-secretory epithelia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 289: C1332–C1342, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devor DC, Singh AK, Lambert LC, DeLuca A, Frizzell RA, Bridges RJ. Bicarbonate and chloride secretion in Calu-3 human airway epithelial cells. J Gen Physiol 113: 743–760, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans RL, Park K, Turner RJ, Watson GE, Nguyen HV, Dennett MR, Hand AR, Flagella M, Shull GE, Melvin JE. Severe impairment of salivation in Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC1)-deficient mice. J Biol Chem 275: 26720–26726, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flagella M, Clarke LL, Miller ML, Erway LC, Giannella RA, Andringa A, Gawenis LR, Kramer J, Duffy JJ, Doetschman T, Lorenz JN, Yamoah EN, Cardell EL, Shull GE. Mice lacking the basolateral Na-K-2Cl cotransporter have impaired epithelial chloride secretion and are profoundly deaf. J Biol Chem 274: 26946–26955, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flemmer AW, Gimenez I, Dowd BF, Darman RB, Forbush B. Activation of the Na-K-Cl cotransporter NKCC1 detected with a phospho-specific antibody. J Biol Chem 277: 37551–37558, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gawenis LR, Bradford EM, Prasad V, Lorenz JN, Simpson JE, Clarke LL, Woo AL, Grisham C, Sanford LP, Doetschman T, Miller ML, Shull GE. Colonic anion secretory defects and metabolic acidosis in mice lacking the NBC1 Na+/HCO3− cotransporter. J Biol Chem 282: 9042–9052, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gawenis LR, Franklin CL, Simpson JE, Palmer BA, Walker NM, Wiggins TM, Clarke LL. cAMP inhibition of murine intestinal Na+/H+ exchange requires CFTR-mediated cell shrinkage of villus epithelium. Gastroenterology 125: 1148–1163, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gawenis LR, Greeb JM, Prasad V, Grisham C, Sanford LP, Doetschman T, Andringa A, Miller ML, Shull GE. Impaired gastric acid secretion in mice with a targeted disruption of the NHE4 Na+/H+ exchanger. J Biol Chem 280: 12781–12789, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gawenis LR, Ledoussal C, Judd LM, Prasad V, Alper SL, Stuart-Tilley A, Woo AL, Grisham C, Sanford LP, Doetschman T, Miller ML, Shull GE. Mice with a targeted disruption of the AE2 Cl−/HCO3− exchanger are achlorhydric. J Biol Chem 279: 30531–30539, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gawenis LR, Stien X, Shull GE, Schultheis PJ, Woo AL, Walker NM, Clarke LL. Intestinal NaCl transport in NHE2 and NHE3 knockout mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 282: G776–G784, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez-Begne M, Nakamoto T, Nguyen HV, Stewart AK, Alper SL, Melvin JE. Enhanced formation of a HCO3− transport metabolon in exocrine cells of NHE1−/− mice. J Biol Chem 282: 35125–35132, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross E, Kurtz I. Structural determinants and significance of regulation of electrogenic Na+-HCO3− cotransporter stoichiometry. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F876–F887, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grubb BR, Lee E, Pace AJ, Koller BH, Boucher RC. Intestinal ion transport in NKCC1-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 279: G707–G718, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haas M, McBrayer D, Lytle C. [Cl−]i-dependent phosphorylation of the Na-K-Cl cotransport protein of dog tracheal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 270: 28955–28961, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Humphreys BD, Jiang L, Chernova MN, Alper SL. Hypertonic activation of AE2 anion exchanger in Xenopus oocytes via NHE-mediated intracellular alkalinization. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 268: C201–C209, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacob P, Christiani S, Rossmann H, Lamprecht G, Vieillard-Baron D, Muller R, Gregor M, Seidler U. Role of Na+HCO3− cotransporter NBC1, Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1, and carbonic anhydrase in rabbit duodenal bicarbonate secretion. Gastroenterology 119: 406–419, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang L, Chernova MN, Alper SL. Secondary regulatory volume increase conferred on Xenopus oocytes by expression of AE2 anion exchanger. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 272: C191–C202, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim G, Selengut J, Levine RL. Carbonic anhydrase III: the phosphatase activity is extrinsic. Arch Biochem Biophys 377: 334–340, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kudrycki KE, Newman PR, Shull GE. cDNA cloning and tissue distribution of mRNAs for two proteins that are related to the band 3 Cl−/HCO3− exchanger. J Biol Chem 265: 462–471, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee H, Hubbert ML, Osborne TF, Woodford K, Zerangue N, Edwards PA. Regulation of the sodium/sulfate co-transporter by farnesoid X receptor alpha. J Biol Chem 282: 21653–21661, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loffing J, Moyer BD, Reynolds D, Shmukler BE, Alper SL, Stanton BA. Functional and molecular characterization of an anion exchanger in airway serous epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C1016–C1023, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melvin JE, Park K, Richardson L, Schultheis PJ, Shull GE. Mouse down-regulated in adenoma (DRA) is an intestinal Cl−/HCO3− exchanger and is up-regulated in colon of mice lacking the NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger. J Biol Chem 274: 22855–22861, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mizumori M, Meyerowitz J, Takeuchi T, Lim S, Lee P, Supuran CT, Guth PH, Engel E, Kaunitz JD, Akiba Y. Epithelial carbonic anhydrases facilitate pCO2 and pH regulation in rat duodenal mucosa. J Physiol 573: 827–842, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Neill WC. Physiological significance of volume-regulatory transporters. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 276: C995–C1011, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohya S, Asakura K, Muraki K, Watanabe M, Imaizumi Y. Molecular and functional characterization of ERG, KCNQ and KCNE subtypes in rat stomach smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 282: G277–G287, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan P, Leppilampi M, Pastorekova S, Pastorek J, Waheed A, Sly WS, Parkkila S. Carbonic anhydrase gene expression in CA II-deficient (Car2−/−) and CA IX-deficient (Car9−/−) mice. J Physiol 571: 319–327, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park K, Evans RL, Watson GE, Nehrke K, Richardson L, Bell SM, Schultheis PJ, Hand AR, Shull GE, Melvin JE. Defective fluid secretion and NaCl absorption in the parotid glands of Na+/H+ exchanger-deficient mice. J Biol Chem 276: 27042–27050, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reynolds A, Parris A, Evans LA, Lindqvist S, Sharp P, Lewis M, Tighe R, Williams MR. Dynamic and differential regulation of NKCC1 by calcium and cAMP in the native human colonic epithelium. J Physiol 582: 507–524, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romero MF, Boron WF. Electrogenic Na+/HCO3− cotransporters: cloning and physiology. Annu Rev Physiol 61: 699–723, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheldon RJ, Malarchik ME, Fox DA, Burks TF, Porreca F. Pharmacological characterization of neural mechanisms regulating mucosal ion transport in mouse jejunum. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 249: 572–582, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spicer Z, Clarke LL, Gawenis LR, Shull GE. Colonic H+-K+-ATPase in K+ conservation and electrogenic Na+ absorption during Na+ restriction. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 281: G1369–G1377, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sterling D, Reithmeier RA, Casey JR. A transport metabolon. Functional interaction of carbonic anhydrase II and chloride/bicarbonate exchangers. J Biol Chem 276: 47886–47894, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suzuki Y, Kovacs CS, Takanaga H, Peng JB, Landowski CP, Hediger MA. Calcium channel TRPV6 is involved in murine maternal-fetal calcium transport. J Bone Miner Res 23: 1249–1256, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turner RJ, George JN. Cl−-HCO3− exchange is present with Na+-K+-Cl− cotransport in rabbit parotid acinar basolateral membranes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 254: C391–C396, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valverde MA, O'Brien JA, Sepulveda FV, Ratcliff RA, Evans MJ, Colledge WH. Impaired cell volume regulation in intestinal crypt epithelia of cystic fibrosis mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 9038–9041, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walker NM, Flagella M, Gawenis LR, Shull GE, Clarke LL. An alternate pathway of cAMP-stimulated Cl secretion across the NKCC1-null murine duodenum. Gastroenterology 123: 531–541, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Z, Schultheis PJ, Shull GE. Three N-terminal variants of the AE2 Cl−/HCO3− exchanger are encoded by mRNAs transcribed from alternative promoters. J Biol Chem 271: 7835–7843, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yannoukakos D, Stuart-Tilley A, Fernandez HA, Fey P, Duyk G, Alper SL. Molecular cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization of two isoforms of the AE3 anion exchanger from human heart. Circ Res 75: 603–614, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]