Abstract

To compare the gastroesophageal junction of the human with the pig, M2 and M3 receptor densities and the potencies of M2 and M3 muscarinic receptor subtype selective antagonists were determined in gastric clasp and sling smooth muscle fibers. Total muscarinic and M2 receptors are higher in pig than human clasp and sling fibers. M3 receptors are higher in human compared with pig sling fibers but lower in human compared with pig clasp fibers. Clasp fibers have fewer M3 receptors than sling fibers in both humans and pigs. Similar to human clasp fibers, pig clasp fibers contract significantly less than pig sling fibers. Analysis of the methoctramine Schild plot suggests that M2 receptors are involved in mediating contraction in pig clasp and sling fibers. Darifenacin potency suggests that M3 receptors mediate contraction in pig sling fibers and that M2 and M3 receptors mediate contraction in pig clasp fibers. Taken together, the data suggest that both M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors mediate the contraction in both pig clasp and sling fibers similar to human clasp and sling fibers.

Keywords: gastroesophageal reflux, receptor immunoprecipitation, smooth muscle contractility, animal models

gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common disease with an incidence of ∼5 per every 1,000 person-years, and its prevalence is estimated to be 10–15% in the adult Western population (8). GERD is a major health care burden with regard to the number of doctor visits, the number of work days lost, and the billions of dollars spent on prescription and over-the-counter medications. The pathophysiological events occurring in GERD appear at first to be simple because the underlying pathogenesis is the movement of gastric contents into the esophageal lumen. However, there is an intense debate surrounding the pathogenesis of GERD with respect to how the protective mechanisms at the gastroesophageal junction high-pressure zone (GEJHPZ) function and fail.

Initially, the proposed barrier between the lower esophagus and the stomach was thought to be an anatomical sphincter (16). With the advent of manometry and high-resolution endoscopic ultrasonography, a HPZ was recognized (12). A detailed description of the anatomical arrangement of the smooth muscle fibers around the GEJ was published in 1979 (17). This study reported that the muscle fibers at the lesser curvature of the stomach were clasp muscle fibers and that those at the greater curvature were sling muscle fibers. The suggestion was proposed that these fibers might be responsible for the HPZ at the GEJ (17). Once this assertion was made, further studies were designed to determine the physiological, pathological, and pharmacological attributes of these structures. High-resolution endoscopic ultrasound, esophageal manometry, autopsy, and animal experiments have been utilized over the past three decades to more fully document the role of the gastric sling/clasp muscle fiber complex in the formation and regulation of the HPZ (7, 18). Important results include the differences reported in the sensitivity and maximal responses to acetylcholine, dopamine, phenylephrine, and isoproterenol by clasp stomach fibers vs. sling stomach fibers (22). The clasp and sling fibers were also shown to relax to electric field stimulation, whereas areas caudal to this contracted.

The macroscopic arrangement of lower esophageal (LE) smooth muscle fibers in humans and pigs is similar. There are short transverse muscle clasps on the lesser curvature of the stomach (clasp fibers) and long oblique gastric sling fibers on the greater curvature of the stomach (17, 23). Because of this similarity, the porcine model has been used as a representative model of the human GEJ (15, 21). The size, anatomical transverse asymmetry (clasp and sling fibers), histology (smooth muscle cells), organization of the enteric nervous system, neurotransmitters, and the enteric motor neurons are similar to those of humans (1, 6). In vivo studies in pigs have shown a swallow-induced LE sphincter relaxation followed by contractions similar to that in humans (23).

The arrangement of the clasp/sling muscle fiber complex was first described in 1979 (17). However, until recently, no intrinsic muscarinic receptor-mediated pressure in the distal esophagus has been demonstrated to arise specifically from the gastric sling/clasp fiber muscle complex in vivo. We identified a distinct pressure profile from the gastric sling/clasp muscle fiber complex using simultaneous high-resolution ultrasound and manometry with pharmacological manipulation using atropine in normal control subjects (2). Along with the pressure generated by the clasp/sling muscle fiber complex, a second, more proximal muscarinic pressure profile associated with the LE circular (LEC) muscle was also seen. Thus the importance of muscarinic tone within both the distal clasp/sling muscle fiber complex and the more proximal LEC is established.

Using the same techniques in patients with GERD, we found that the proximal pressure profile attributable to the LEC was present. However, the gastric sling/clasp muscle fiber pressure profile was absent (20). This establishes the importance of the intrinsic muscarinic gastric sling/clasp muscle fiber pressure profile to the antireflux barrier. Considering their importance in the GEJHPZ, detailed investigations of these muscles is important in delineating the pathophysiology of GERD. This includes any anatomical or physiological differences between the muscles that generate the pressure to prevent reflux of gastric contents. It is also important to understand the species differences when using an animal model to represent human physiology.

The aim of the present study was to determine which muscarinic receptors mediate contraction of porcine clasp and sling muscle fibers and to quantify the density of the total and of the individual M2 and individual M3 muscarinic receptor subtypes in these tissues. Results are compared with our previously reported findings in human clasp and sling fibers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

All drugs and chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO) except for darifenacin (which was a generous gift from Pfizer Limited, Sandwich, Kent, UK), digitonin (Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan) and pansorbin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA).

Animal specimens.

Pig tissues were obtained from local slaughter houses. The pigs were 6–12 mo of age and weighed ∼125–170 lbs. Slaughter of the pigs followed rules and regulations written by the Food and Safety Inspection Service (FSIS), an agency of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Transport.

Specimens were collected from each pig immediately postslaughter. Each specimen included an entire stomach, part of the esophagus, and part of the crural diaphragm en bloc. The collected unit was temporarily preserved on ice and Tyrode's solution (a modified Locke solution, used in physiological experiments, tissue cultures, and tissue preservation). The ingredients in Tyrode's solution were as follows (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 0.4 NaH2PO4, 1.8 CaCl2, 0.5 MgCl2, 23.8 NaHCO3, and 5.6 glucose. The preserved specimens were transported to the laboratory within 1–2 h of collection.

Dissection.

Peritoneal fat was removed, and dissection began using microscissors to remove the most superficial longitudinal fibers in a circular pattern around the esophagus. The deeper circular fibers were removed next, moving from the greater curvature toward the lesser curvature. The exact location of the sling and clasp fibers were identified at the greater and lesser curvature of GEJ, respectively, once the superficial longitudinal fibers were removed. Sling muscle fibers were removed from a relatively straight section of the greater curvature. Clasp fibers were obtained 1–2 cm distal to GEJ along the lesser curvature. The muscles were further divided into individual strips, each measuring 1–2 mm in width and 8–10 mm in length. Care was taken to ensure that the orientation of the muscle fibers was parallel to the muscle strips and that all strips were of uniform length and diameter. The muscle strips were then suspended with 0.5 g of tension in tissue baths containing 10 ml of modified Tyrode's solution and equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2 at 37°C.

Carbachol concentration response curves.

Following equilibration to the bath solution for at least 30 min, the strips were challenged with 30 μM carbachol and rinsed with buffer (5 exchanges over 60 min). This initial contraction to carbachol was used to separate the strips into groups such that the average contraction of all groups was the same. After washing, the strips were incubated for 30 min in the presence or absence of one of three concentrations of the M2 selective antagonist methoctramine (0.1, 1, or 10 μM) or the M3 selective antagonist darifenacin (30, 100, or 300 nM). Concentration response curves were derived from the peak tension developed following the cumulative addition of carbachol (10-nM to 1-mM final bath concentration). Either vehicle or one concentration of methoctramine or darifenacin was used for each muscle strip. Because of tachyphylaxis in muscarinic receptor-mediated contraction, we could not repeat concentration response curves on the same muscle strip; hence each strip could not be used as its own control for pairing EC50 values. Therefore, dose ratios were determined on the basis of the average of the responses of vehicle (H2O)-treated strips. This average EC50 was used as a universal denominator to determine the dose ratio for each strip in the presence of the antagonist. The data were normalized to the initial contraction induced by 30 μM carbachol. EC values were determined for each strip using a sigmoidal curve fit of the data (Origin; Originlab, Northampton, MA), and Schild plots were constructed. If the 95% confidence interval of the slope of the Schild plot overlapped 1, the slope was constrained to 1 and the estimated pKb ± SE is reported. If the 95% confidence interval of the slope of the Schild plot did not include 1, pA2 ± SE is reported using the unconstrained slope.

Immunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitation of muscarinic receptors from the individual dissections was performed as previously described (3). Briefly, the tissues were homogenized in cold Tris EDTA buffer (TE) with 10 μg/ml of the following protease inhibitors: soybean and lima bean trypsin inhibitors, aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin, and α2-macroglobulin. A sample (20 μl) of [3H]quinuclidinyl benzilate (QNB) (49 Ci/mM, ∼4,000 cpm/μl) per milliliter assay homogenate was added and incubated at room temperature for 30 min with inversion every 5 min. Samples were pelleted via centrifugation at 20,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, and the pellet was solubilized in TE buffer containing 1% digitonin and 0.2% cholic acid (1% TEDC) with the above protease inhibitors at 100 mg wet weight per milliliter. Samples were incubated for 50 min at 4°C, with inversion every 5 min then centrifuged at 30,000 g for 45 min at 4°C. The supernatant containing the solubilized receptors was incubated overnight after addition of the M2 antibody, the M3 antibody or vehicle at 4°C.

To determine total receptor density, the supernatant containing the solubilized receptors bound with [3H]QNB were desalted over Sephadex G-50 minicolumns with 0.1% TEDC to separate the unincorporated ligand from the solubilized receptors. The amount of radioactivity in the eluate was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry. M2 and M3 receptors were precipitated by adding 200 μl pansorbin and incubated at 4°C for 50 min, with inversion every 5 min. The precipitated receptors were pelleted via centrifugation at 15,000 g for 1 min at 4°C, and the pellet was surface washed with 500 μl of 0.1% TEDC. A sample (50 μl) of 72.5 mM deoxycholate/750 mM NaOH was added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of TE buffer and neutralized with 50 μl of 1 M HCl. Radioactive counts were determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry. Protein content was determined by a Coomassie blue dye binding protein assay using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Receptor density (means ± SE) is reported as femtomoles (fmol) receptor per milligram of solubilized protein.

RESULTS

Immunoprecipitation.

The results of the receptor density determinations are shown in Table 1 compared with our previous results in human tissue (4). As in the human tissue, the total and M3 receptor density in the pig sling fibers were statistically significantly greater than the clasp fibers. In contrast to the human data, the M2 receptor density was slightly greater in the pig clasp than the sling fibers, whereas M2 receptor density is greater in human sling than clasp fibers. However, neither of these differences are statistically significant.

Table 1.

Comparison of M2 and M3 muscarinic receptor density in pig and human clasp and sling fibers

| Pig |

Human |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | M2 | M3 | Total | M2 | M3 | |

| Clasp | 797 ± 14 | 512 ± 17 | 20 ± 1.3 | 228 ± 20 | 116 ± 16 | 8 ± 2 |

| Sling | 856 ± 27* | 443 ± 39 | 32 ± 1.5* | 353 ± 7* | 171 ± 6 | 60 ± 14* |

Values are means ± SE. Receptor density is expressed as fmol receptors per mg solubilized protein. Values for human tissues were extracted from our previously published results (4).

Significant difference (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) between clasp and sling fibers.

Concentration-effect relationships.

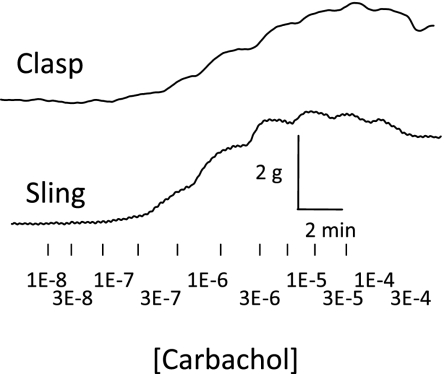

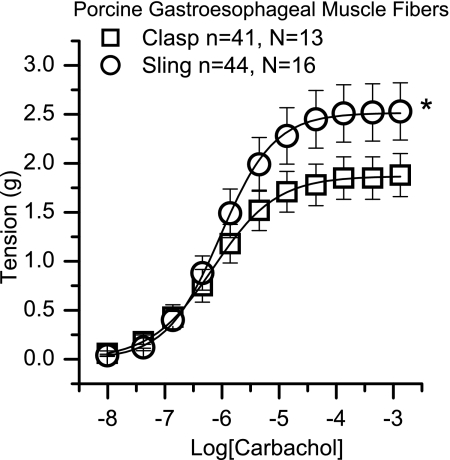

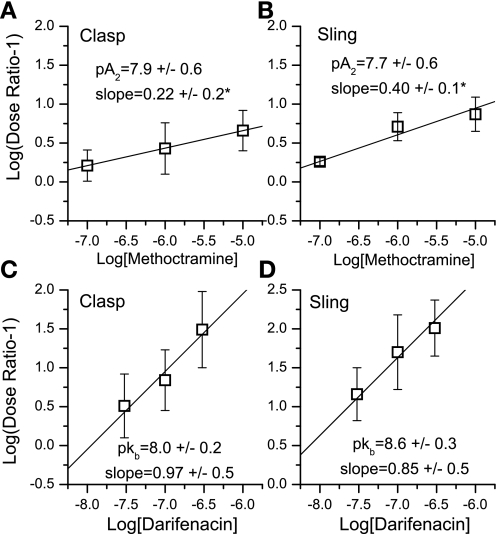

Each muscle section was studied for isometric tension development in response to carbachol, and each demonstrated a dose-related response to this agonist. Representative tracings for both clasp and sling fibers are show in Fig. 1. As seen in Fig. 2, the maximal carbachol-induced contraction of clasp fibers is significantly less than sling fibers (P < 0.05); however, there is no difference in the potency of carbachol to mediate contraction between clasp and sling fibers. Figure 3 shows the graded concentration-effect relationship for carbachol in clasp (Fig. 3, A and C) and sling fibers (Fig. 3, B and D). Also shown in Fig. 3 are the curves for graded doses of this agonist with three different fixed concentrations of darifenacin, a relatively selective M3 competitive antagonist, and three different fixed concentrations of methoctramine, an M2 selective antagonist. Schild plots for determining the potency of the antagonists to inhibit contraction are shown in Fig. 4. In clasp fibers, the intermediate potency of darifenacin (pKb = 8.0) suggests that both M3 and M2 receptors are involved in mediating contraction. Because of the low slope of the methoctramine Schild plot (0.22 ± 0.2, significantly less than 1), the methoctramine pA2 value may be unrelated to the disassociation constant at any one receptor subtype. The low slope does, however, suggest that more than one receptor subtype may be involved in the response. In the sling fibers, the relatively high potency of darifenacin (pKb = 8.6) suggests that M3 receptors mediate contraction. However, the low slope of the methoctramine Schild plot (0.40 ± 0.1, significantly less than 1) may indicate that more than one receptor subtype mediates contraction. These results, especially in the clasp fibers, suggest that the carbachol-induced contraction is mediated by both M2 and M3 receptors. Neither methoctramine nor darifenacin had significant effects on the maximal contraction of the clasp fibers. However, both 0.1 and 10 μM methoctramine induced a significant increase in contractile force in the sling fibers, whereas neither 1 μM methoctramine nor any concentration of darifenacin had any significant effects on the maximal contraction in sling fibers. This augmentation of the contraction of sling fibers by methoctramine suggests the possibility of inhibitory M2 receptors involved in mediating contraction of the sling fibers.

Fig. 1.

Original tracings of carbachol concentration response experiments from pig clasp and sling muscle fibers.

Fig. 2.

Carbachol concentration response curves for porcine clasp and sling fibers. *Denotes statistically significant difference in maximal contraction between clasp and sling fibers (P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U-test), n = number of muscle strips, N = number of pigs.

Fig. 3.

Concentration response curves for carbachol-induced contraction of clasp (A and C) and sling fibers (B and D) in the presence of various concentrations of methoctramine (Meth) (A and B) and darifenacin (DAR) (C and D). Results are shown as percent of the initial contractile response induced by 30 μM carbachol; n = number of muscle strips. All results are pooled from 4 different animals. *Denotes statistically significant difference in maximal contraction from vehicle (P < 0.05, Student's t-test).

Fig. 4.

Schild plots for determination of the potency of methoctramine (A and B) and darifenacin (C and D) for inhibition of carbachol-induced contraction of porcine clasp (A and C) and sling (B and D) fibers. *Denotes that the slope of the Schild plot is significantly less than unity.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study demonstrate that the density of muscarinic receptor subtypes is different in the pig clasp and sling muscle fiber complex than in human clasp and sling muscle fiber complex (Table 1). However, the clasp and sling muscle fibers in both human and porcine, which work together to contract the GEJ and prevent reflux, have a greater density of M2 than of M3 receptors, similar to most other smooth muscles studied.

The carbachol-induced maximal contraction is greater in the pig sling muscle fibers than in the pig clasp muscle fibers. This result is in general agreement with a previous study showing that human sling muscle fibers contract significantly greater to acetylcholine than human clasp muscle fibers (22) and our prior study in human clasp and sling muscle fibers (4).

Classic pharmacological analysis of concentration-effect relationships was formulated before the concept of multiple receptor subtypes existed and is based on the assumption that one receptor mediates one effect. Schild analysis of our data yielded conflicting conclusions with respect to which receptor subtype mediates contraction of the gastric clasp and sling muscle fibers. In human sling fibers and both the human and porcine clasp muscle fibers, the M3 selective antagonist darifenacin yielded an inhibitory potency intermediate between that reported for M2 and M3 receptors, thus suggesting that both receptors may mediate the contractile response. In porcine sling fibers, darifenacin potency is high, consistent with M3 receptors mediating contraction. However, the Schild plot for the M2 selective antagonist methoctramine has a slope significantly less than 1, which could indicate that more than one receptor subtype is involved in the contractile response.

The relatively high potency of darifenacin and the low slope of the methoctramine Schild plot in the pig sling fibers are consistent with a major M3 receptor contribution and possibly a minor M2 receptor contribution to mediating contraction in the sling fibers. However, in the clasp fibers, the relatively low potency of darifenacin and the low slope of the methoctramine Schild plot suggest that both M2 and M3 receptors mediate contraction. These results suggest that both M2 and M3 receptors mediate contraction in porcine clasp and sling fibers, albeit likely with differences in the relative contribution of each receptor subtype in each tissue. On the basis of the result that darifenacin is less potent in inhibiting clasp fiber contraction than sling fiber contraction, we conclude that the M2 receptor has a greater contractile role in clasp fibers than in sling fibers. The lower potency of darifenacin to inhibit contraction of the porcine clasp fibers than sling fibers may be related to the lower density of M3 receptors in the clasp fibers than in the sling fibers.

The M2 selective antagonist methoctramine significantly augmented the Emax response to carbachol in sling muscle fibers. This finding suggests the possibility of inhibitory M2 receptors in porcine sling muscle. When these inhibitory receptors are blocked with methoctramine, the contraction is augmented. Another possible explanation is that the signal transduction mechanisms activated by M2 receptors inhibit the signaling from M3 receptors in the muscle. This would result in a subadditive interaction. An increased contractile response could occur as a consequence of blocking the M2 receptor inhibition on M3 signaling by methoctramine.

Because of the lack of completely specific antagonists, the contribution of the individual receptor subtypes cannot be precisely determined in either pig or human tissue. Because it has been established that both M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors contribute to the carbachol-mediated contraction in the gastric sling and clasp muscle fibers, there is interest in determining whether these two receptor subtypes interact. Toward that end we have previously developed the theoretical framework and associated experimental procedure that quantitates that interaction. That methodology, however, requires occupation-effect data for each receptor type when it is the sole receptor producing the effect. That was achieved and the method applied in our earlier publication (5), which utilized knockout (KO) mice. In that study isolated strips from the M2-KO and the M3-KO each gave dose-related effects that allowed prediction of the dose-effect relation accompanying the dual occupancy (the usual, wild-type case). That curve of prediction, when compared with corresponding experimental data, leads to a measure of the interaction. In that mouse experiment, the interaction was simply additive, but the methodology sets the stage for examination of such interactions in the human and porcine preparations discussed here. For these species, however, we lack the needed knockouts, and therefore efforts are under way to employ highly selective M2 competitive antagonists (9) to yield the needed single receptor occupation-effect data. The present results (receptor density and K values) provide a guide for finding the appropriate antagonist doses that might achieve this objective, and the results of that study will need to be the subject of a future communication.

In summary, the receptor density of each smooth muscle group differs according to the muscle location, function, and species. It was found that, similar to human clasp and sling muscle fibers, porcine clasp and sling muscle fiber contraction is mediated by both M2 and M3 receptors.

GRANTS

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1DK059500.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Elan S. Miller, Gabrielle N. Soussan, and Imran Hamid in carrying out the contractility studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aggestrup S, Uddman R, Jensen SL, Hakanson R, Sundler F, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell O, Emson P. Regulatory peptides in lower esophageal sphincter of pig and man. Dig Dis Sci 31: 1370–1375, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brasseur JG, Ulerich R, Dai Q, Patel DK, Soliman AMS, Miller LS. Pharmacological dissection of the human gastro-oesophageal segment into three sphincteric components. J Physiol 580: 961–975, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braverman AS, Lebed B, Linder M, Ruggieri MR. M2 mediated contractions of human bladder from organ donors is associated with an increase in urothelial muscarinic receptors. Neurourol Urodyn 26: 63–70, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braverman AS, Miller LS, Vegesna AK, Tiwana MI, Tallarida RJ, Ruggieri MR., Sr Quantitation of the contractile response mediated by two receptors: M2 and M3 muscarinic receptor mediated contractions of human gastroesophageal smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 329: 218–224, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braverman AS, Tallarida RJ, Ruggieri MR., Sr The use of occupation isoboles for analysis of a response mediated by two receptors: M2 and M3 muscarinic receptor subtype-induced mouse stomach contractions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 325: 954–960, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown DR, Timmermans JP. Lessons from the porcine enteric nervous system. Neurogastroenterol Motil 16, Suppl 1: 50–54, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burleigh DE. The effects of drugs and electrical field stimulation on the human lower oesophageal sphincter. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther 240: 169–176, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camilleri M, Dubois D, Coulie B, Jones M, Kahrilas PJ, Rentz AM, Sonnenberg A, Stanghellini V, Stewart WF, Tack J, Talley NJ, Whitehead W, Revicki DA, Camilleri M, Dubois D, Coulie B, Jones M, Kahrilas PJ, Rentz AM, Sonnenberg A, Stanghellini V, Stewart WF, Tack J, Talley NJ, Whitehead W, Revicki DA. Prevalence and socioeconomic impact of upper gastrointestinal disorders in the United States: results of the US Upper Gastrointestinal Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 3: 543–552, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carsi JM, Valentine HH, Potter LT. m2-Toxin: a selective ligand for M2 muscarinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol 56: 933–937, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caulfield MP. Muscarinic receptors—characterization, coupling and function. Pharmacol Ther 58: 319–379, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caulfield MP, Birdsall NJ. International Union of Pharmacology. XVII. Classification of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Pharmacol Rev 50: 279–290, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Code CF, Fyke FE, Jr, Schlegel JF. The gastroesophageal sphincter in healthy human beings. Gastroenterologia 86: 135–150, 1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans T, Hepler JR, Masters SB, Brown JH, Harden TK. Guanine nucleotide regulation of agonist binding to muscarinic cholinergic receptors. Relation to efficacy of agonists for stimulation of phosphoinositide breakdown and Ca2+ mobilization. Biochem J 232: 751–757, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaddum J. The Quantitative effects of antagonistic drugs. J Physiol 89: 7P–9P, 1937 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korn O, Stein HJ, Richter TH, Liebermann-Meffert D. Gastroesophageal sphincter: a model. Dis Esophagus 10: 105–109, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lerche W. The Esophagus and Pharynx in Action. A Study of Structure in Relation to Function Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1950 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liebermann-Meffert D, Allgower M, Schmid P, Blum AL. Muscular equivalent of the lower esophageal sphincter. Gastroenterology 76: 31–38, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCray WH, Jr, Chung C, Parkman HP, Miller LS. Use of simultaneous high-resolution endoluminal sonography (HRES) and manometry to characterize high pressure zone of distal esophagus. Dig Dis Sci 45: 1660–1666, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKinney M, Miller JH, Gibson VA, Nickelson L, Aksoy S. Interactions of agonists with M2 and M4 muscarinic receptor subtypes mediating cyclic AMP inhibition. Mol Pharmacol 40: 1014–1022, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller LS, Dai Q, Vegesna A, Korimilli A, Ulerich R, Schiffner B, Brasseur JG. A missing sphincteric component of the gastro-esophageal junction in patients with GERD. Neurogastroenterol Motil 21: 813–e52, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schopf BW, Blair G, Dong S, Troger K. A porcine model of gastroesophageal reflux. J Invest Surg 10: 105–114, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian ZQ, Liu JF, Wang GY, Li BQ, Wang FS, Wang QZ, Cao FM, Zhang YF. Responses of human clasp and sling fibers to neuromimetics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 19: 440–447, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vicente Y, Da Rocha C, Yu J, Hernandez-Peredo G, Martinez L, Perez-Mies B, Tovar JA. Architecture and function of the gastroesophageal barrier in the piglet. Dig Dis Sci 46: 1899–1908, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]