Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine prevalence and correlates of handgun access among adolescents seeking care in an urban Emergency Department (ED) in order to inform future injury prevention strategies.

METHODS

In this observational cross-sectional study performed in the ED of a large urban hospital, 14- to 18-year-old adolescents completed a computerized survey of risk behaviors. Adolescents seeking ED care (for injury or medical complaint) were approached seven days a week over a 22-month period. Validated measures included measures of demographics, sexual activity, substance use, injury, violent behavior, and handgun access. A logistic regression model predicting handgun access was performed.

RESULTS

A total of 3050 adolescents completed the survey (44% male, 58.9% African American), with 417 (12%) refusing to participate. One-third of the sample (n=1003) reported access to a handgun, and of those 54% were males (n=542). Logistic regression results indicated that older age (AOR: 1.58; 95% CI: 1.30–1.94), African American race (AOR: 1.34; 95% CI: 1.11–1.61), male gender (AOR: 1.99; 95% CI: 1.66–2.37), and being employed (AOR: 1.35; 95% CI: 1.11–1.65), as well as seeking ED care for a medical complaint as compared to intentional injury (AOR: 1.69; 95% CI 1.62–2.50) predicted handgun access. Binge drinking (AOR: 1.75; 95% CI: 1.37–2.27),marijuana use (AOR: 1.93; 95% CI: 1.58–2.36), sexual activity (AOR: 1.64; 95% CI: 1.32–2.02), prior injury by a gun (AOR: 1.80; 95% CI: 1.32–2.46), serious physical violence (AOR: 1.37; 95% CI: 1.13–1.66) and group fighting (AOR: 2.07; 95% CI: 1.68–2.56) also predicted access.

CONCLUSIONS

High rates of handgun access were evident among adolescents presenting in an inner city ED, including those seeking care for non injury related reasons. Adolescents with access to handguns were more likely to report risk behaviors and past injury, providing clinicians with an opportunity for injury prevention initiatives.

Keywords: Injury Prevention and Control, Adolescents, Youth Violence, Emergency Department, Handgun Access

Introduction

Homicide is the leading cause of death for African-American adolescents and the second leading cause of death for White adolescents in the US.(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Center for Injury Prevention and Control 2005) Firearms are the most common mechanism of violent death among children under the age of 18, accounting for 61% of all homicides and 41% of all suicides in 2006. In the same year, unintentional firearm injuries resulted in 125 deaths in people under the age of 18.(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Center for Injury Prevention and Control 2005) Researchers have estimated that one American child or adolescent is killed by a firearm every 3 hours, and that for every death there are three nonfatal injuries.(Annest, Mercy et al. 1995; Hardy 2006)

Firearms are known to increase the lethality of violence(Zimring 1972) and increase rates of successful completion of suicide;(Beaman, Annest et al. 2000) firearms also increase the severity of injuries. Among adolescents presenting to urban ED’s with assault injuries, 25–40% involve weapons.(Cheng, Johnson et al. 2006) To date, prevalence estimates for handgun access among adolescents have focused on school-based samples involving high school students.(Swahn, Hammig et al. 2002; Borowsky and Ireland 2004) These samples are helpful in describing access rates for a general population; however, they may miss high-risk individuals that do not to attend school.(Sheley and Brewer 1995; Wilson and Klein 2000; Wright, Wintemute et al. 2008) Researchers(Cheng, Schwarz et al. 2003; Cunningham, Vaidya et al. 2005; Cheng, Wright et al. 2008; Walton, Goldstein et al. 2008) have suggested that the ED may be a logical place to implement adolescent injury prevention programs focused on decreasing adolescent gun injury, as the population of adolescents seeking ED care have elevated rates of other risk behaviors (substance use, violence) versus community or school based samples.(Wilson and Klein 2000)

Several national medical organizations have made policy statements on violence prevention among adolescents, including the American Medical Association,(American Medical Association 1995) the American Academy of Pediatrics,(American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Violence 1999) the American Association of Family Physicians,(American Academy of Family Physicians 2000) and the American College of Emergency Physicians.(American College of Emergency Physicians 2007) These policy statements recommend that physicians incorporate adolescent violence prevention into their practices. Identification of individuals that may have access to handguns is an important component of violence prevention. Understanding the associated risk behaviors of adolescents who present to the ED seeking care and have access to a handgun at home will inform future ED-based adolescent and family violence prevention initiatives.

To our knowledge no prior study has described the rates and correlates of handgun access among a sample of adolescents seeking ED care, regardless of presenting complaint; prior studies have targeted only assault-injured adolescents. (Cheng, Johnson et al. 2006) Weapon related risk factors were selected for this current study based on theoretical models of adolescent violence/weapon access (Jessor 1991; Steinman and Zimmerman 2003; Zimmerman, Morrel-Samuels et al. 2004) and prior research(DuRant, Kahn et al. 1997; Dahlberg 1998; Lowry, Powell et al. 1998; Simon, Richardson et al. 1998; Sege, Stringham et al. 1999; Hayes and Sege 2003; Borowsky, Mozayeny et al. 2004) and include demographics (age, minority status, and gender), prior injury and fighting, chief complaint, and other multiple risk behaviors such as substance abuse and sexual activity. The objectives of this study were to describe the prevalence and correlates of firearm access in an urban ED.

Methods

Study Design

An observational cross-sectional study design was used to obtain a consecutive cohort sample.

Study Setting/Participants

This study took place at the Hurley Medical Center (HMC) Emergency Department in Flint, Michigan, a 540-bed teaching hospital and Level I Trauma Center with an annual ED census of approximately 75,000 patients per year (25,000 pediatric patients). HMC is the only public hospital in the city of Flint, which is comparable in terms of crime and poverty levels to other large urban centers such as Detroit, Hartford, Camden, St Louis, and Oakland.(Federal Bureau of Investigation 2006) The population of Flint is 50% African American.(Michigan Department of Community Health 2002)

Recruitment

Patient’s aged 14 –18 presenting to the ED for either medical illness or injury were eligible for the study and were identified from electronic tracking logs. Recruitment took place during the afternoon and evening shifts (12pm-11pm), seven days per week, from September 2006 to June 2008. Trained Research Assistants (RA) approached potential participants in waiting rooms or treatment spaces. Patients were excluded from the study if they were being treated for sexual assault, acute suicidal ideation, or had abnormal vital signs. Parental consent was obtained for individuals under age 18. Consenting/assenting participants self-administered a ~15-minute computerized survey with audio via headphones and received a token $1.00 gift (e.g., notebook, pens) for their participation in the study. The survey was in English only, however, consistent with the local population no participants were excluded due to language limitations. Research staff remained on hand to assist participants with the survey, pausing the computer when medical intervention was necessary. Confidentiality of responses was maintained by limiting friends or family to areas of the room where responses could not be viewed on the computer screen. In the event that adolescents completed the screen more than once due to repeated ED visits over the recruitment period, the first completed screen was included in the data. Study procedures were approved and conducted in compliance with the guidelines of the University of Michigan and Hurley Medical Center, Institutional Review Boards (IRB) for Human Subjects. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the NIH for this study.

Measures

Demographic Information

Age, race, ethnicity, gender, employment, grades in school, and receipt of public assistance were collected using items from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (ADD Health).(Harris, Florey et al. 2003) Age was used as a categorical (<16, 16+) rather than continuous variable in the analysis.

Handgun Access

A question from Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS)(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1993a) was used to assess if adolescents had access to a handgun. Participants were asked “Could you get a handgun if you wanted to?”

Sexual Activity

Lifetime sexual intercourse was assessed using a question taken from the YRBS(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1993a). The question read “Have you ever had sexual intercourse,” with corresponding ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer options.

Substance Use

Past lifetime frequency and quantity of alcohol use were assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C).(Bush, Kivlahan et al. 1998; Chung, Colby et al. 2002) Binge drinking was also assessed using the AUDIT-C, however, the binge drinking quantity definition was lowered from the original of “6 or more drinks on one occasion” to “5 or more drinks on one occasion.” This was done based upon past recommendations by Chung et al. 2002 for application among adolescents.(Chung, Colby et al. 2002) Past year cigarette(Johnston, O'Malley et al. 2007) and marijuana(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1993a) use were measured with dichotomous measures indicating ‘yes’ or ‘no’ use.

Violent Behavior

Two questions from the ADD Health(Harris, Florey et al. 2003) survey were used to assess violent behavior. Respondents were asked “In the past 12 months, how often have you gotten into a serious physical fight?” and “In the past twelve months, how often did you take part in a fight where a group of your friends was against another group?” These responses were dichotomized to ‘yes’ if the respondent had been in a physical or group fight at any time in the past twelve months and ‘no’ if the respondent had not been in a physical or group fight. These two violence factors were treated as separate variables in the analysis.

Firearm- or Assault-Related Injury

Injury from a gun or physical fight was measured using the Adolescent Injury Checklist.(Jelalian, Alday et al. 2000) Patients were asked if they had been injured in a physical fight or injured by a gun in the past year. Responses were coded as yes – fight or gun related injuries were sustained in the past year, or no — no fight or gun related injuries in the past year.

Chief Complaint

Current ED visit was abstracted from the medical chart and classified as medical illness (e.g., abdominal pain, asthma) or injury [unintentional (E800–E869, E880–E929) or intentional (E950–E969)] by research assistants who were trained based on the supplementary classification of external cause of injury, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.(National Center for Health Statistics & U.S. Health Care Financing Administration 2000) Chart reviews were audited regularly to maintain reliability in keeping with the criteria described by Gilbert and Lowenstein.(Gilbert, Lowenstein et al. 1996) Regular meetings were held with RA staff to review coding rules and chart data.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were computed for demographics, behavioral characteristics, and past-year handgun access. The chi-square test of independence was used to perform bivariate analyses. In order to assess the relationship between demographic and behavioral risk factors and gun access, unadjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Variables based on prior research(Jessor 1991; Steinman and Zimmerman 2003; Zimmerman, Morrel-Samuels et al. 2004) and theoretical causation were retained in the logistic regression model predicting handgun access. In order to control for demographic factors, these variables were retained in the multivariate logistic regression model. Variables measuring substance use (i.e., alcohol use, binge drinking, cigarette use, and marijuana use) were highly correlated; thus, any alcohol use and cigarette use were not included in the logistic regression model. There was no evidence of multicollinearity among the variables retained in the final regression model.

Results

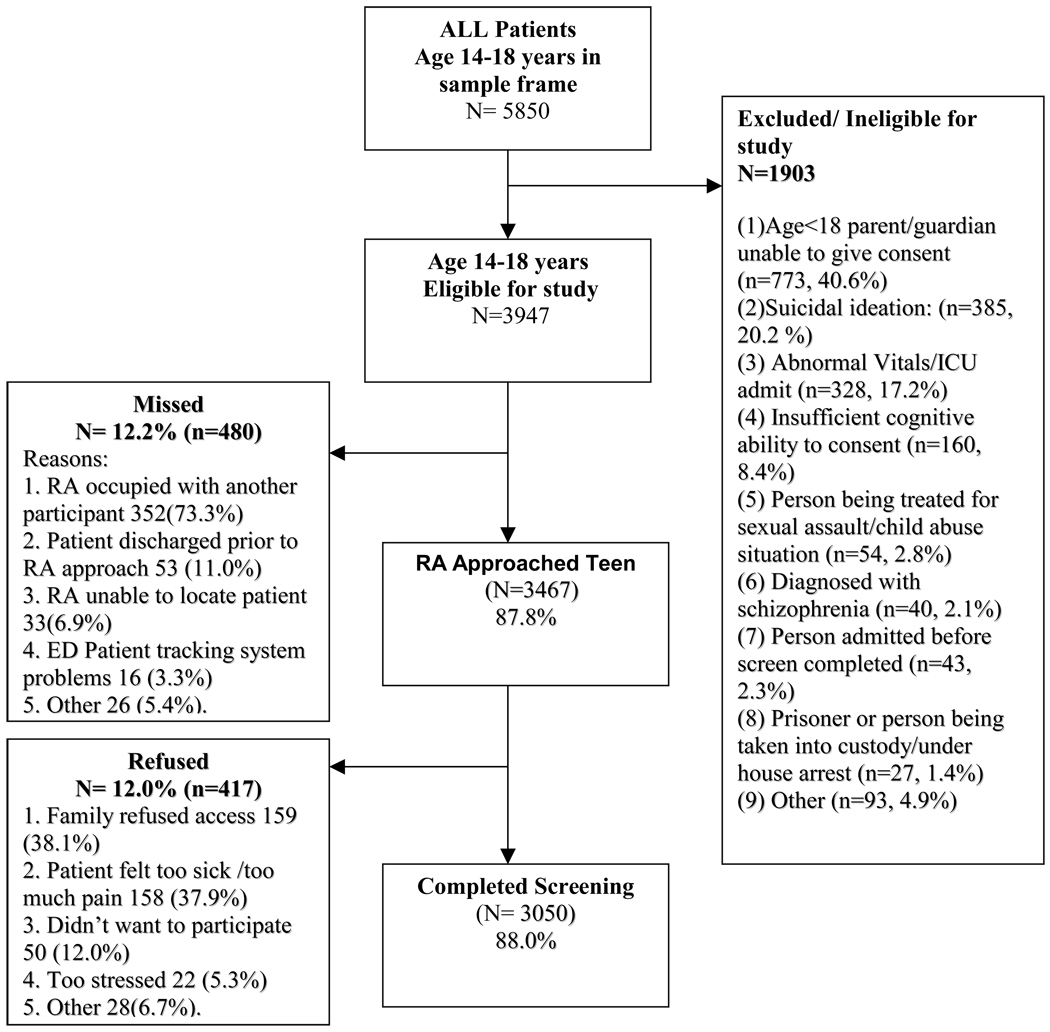

A total of 3947 eligible patients presented to the ED during the recruitment period. Of these, 87.8% (n=3467) were approached and 12.2% (n=480) were not approached. Common reasons for missing participants were: the RA was occupied with another patient (n=352, 73.3%), the patient was discharged before the RA was able to approach him/her (n=53, 11.0%), or the RA was unable to locate the patient (n=33, 6.9%). Among eligible patients who were approached, 88% (n=3050) completed the screen and 12.0% (n=417) refused to participate. Participants who refused to participate were similar to those who did with regard to gender, race, and reason for ED visit. Among the participants, 56.0% were female, 58.9% were African American, and 61.0% were age 16 or older (Table 1). A majority of the sample (n=1818, 59.6%) presented to the ED for a medical compliant; 34.5% (n=1051) presented for an unintentional injury and 5.9% (n=181) presented for an intentional injury (Table 1). The distribution of chief compliant is consistent with national ED trends.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample and handgun access rates (n=3050)

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age (16 and older) | 1862 | 61.0% |

| Race (African American) | 1794 | 58.9% |

| Gender (Male) | 1343 | 44.0% |

| Failing Grades in School | 1005 | 33.0% |

| Employed | 701 | 23.0% |

| Public assistance | 1672 | 54.8% |

| Past- Year Substance use | ||

| Any alcohol use | 850 | 27.9% |

| Binge drinking | 433 | 14.2% |

| Cigarette use | 775 | 25.4% |

| Marijuana use | 862 | 28.3% |

| Past-year Injury | ||

| Injured in a physical fight | 496 | 16.3% |

| Injured by a gun | 233 | 7.6% |

| Aggression | ||

| Serious physical fight | 1135 | 37.2% |

| Group fighting | 643 | 21.1% |

| Sexual activity | 1811 | 59.4% |

| Reason for visit | ||

| Medical | 1818 | 59.6% |

| Unintentional Injury | 1051 | 34.5% |

| Intentional Injury | 181 | 5.9% |

| Handgun Access | 1003 | 32.9% |

Rates of handgun access

One third (n=1003, 32.9%) of the sample reported that they had access to a handgun. Of these, 61.9% (n=621) were in the ED for a medical complaint, 31.7% (n=318) for an unintentional injury, and 6.4% (n=64) for intentional injury.

Bivariate analysis

In the bivariate analysis, participants who reported access to a handgun differed significantly on all variables except family receipt of public assistance (Table 1). Males were more likely (OR: 1.83; 95% CI:1.57–2.13 ) than females to report past-year access to a handgun, and African Americans were more likely than other races to report access (OR: 1.36; 95% CI:1.17–1.59). The strongest associations were for marijuana use (OR: 3.72; 95% CI: 3.15–4.39), binge drinking (OR: 3.62; 95% CI: 2.94–4.47), alcohol use (OR: 3.38; 95% CI: 2.86–3.98) and group fighting (OR: 3.24; 95% CI: 2.70–3.87).

Multivariate analysis

Regarding demographic factors, results of the logistic regression model predicting handgun access showed that male gender, older age, African-American race, and being employed were associated with access to handguns. Poverty, as measured by family receipt of public assistance, was associated with access. Teens seeking care for medical complaints were more likely then those seeking care for intentional injury to have access (AOR: 1.69; 95% CI 1.62–2.50). Regarding other risk variables, group fighting (AOR: 2.07; 95% CI: 1.68–2.56), binge drinking (AOR: 1.75; 95% CI: 1.37–2.27), marijuana use (AOR: 1.93; 95% CI: 1.58–2.36), sexual activity (AOR: 1.64; 95% CI: 1.32–2.02), and prior injury by gun (AOR: 1.80; 95% CI: 1.32–2.46) were associated with handgun access (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate analyses & Multivariate logistic regression predicting handgun access

| Handgun access (n=3050) |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Bivariate analyses OR (95% CI) |

Multivariate logistic regression** AOR (95% CI) |

|

| Demographics | ||

| Age (16 and older) | 2.19 (1.86–2.58) | 1.58 (1.30–1.94) |

| Race (African American) | 1.36 (1.17–1.59) | 1.34 (1.11–1.61) |

| Gender (Male) | 1.83 (1.57–2.13) | 1.99 (1.66–2.37) |

| Grades in school (D–F) | 1.72 (1.47–2.02) | 0.86 (0.72–1.03) |

| Employed | 1.56 (1.31–1.85) | 1.35 (1.11–1.65) |

| Public assistance | 1.03 (0.88–1.20) | 0.88 (0.73–1.04) |

| Substance use | ||

| Any alcohol use | 3.38 (2.86–3.98) | |

| Binge drinking | 3.62 (2.94–4.47) | 1.75 (1.37–2.27) |

| Cigarette use | 2.71 (2.29–3.20) | |

| Marijuana use | 3.72 (3.15–4.39) | 1.93 (1.58–2.36) |

| Past-year injury | ||

| Injured in a physical fight | 1.83 (1.50–2.22) | 1.09 (0.86–1.37) |

| Injured by a gun | 2.77 (2.13–3.63) | 1.80 (1.32–2.46) |

| Aggression | ||

| Serious physical fight | 2.23 (1.91–2.60) | 1.37 (1.13–1.66) |

| Group fighting | 3.24 (2.70–3.87) | 2.07 (1.68–2.56) |

| Sexual activity | 3.10 (2.62–3.68) | 1.64 (1.32–2.02) |

| Reason for ED visit* | ||

| Unintentional Injury | 0.85 (0.71–0.99) | 0.92 (0.76–1.11) |

| Intentional Injury | 1.05 (0.77–1.45) | 0.59 (0.40–0.86) |

Reference category is medical visit

The multivariate regression is an all-inclusive model

Discussion

This study presents novel data regarding the rates of handgun access among adolescent seeking care in an urban ED (regardless of chief presenting complaint) and the concomitant demographic and behavioral risk factors associated with handgun access. The inner city ED visit provides an opportunity to access inner city adolescents, who often lack a primary care physician and may not attend school regularly, in order to deliver injury prevention efforts. In this sample, one-third of all teens and 40% of male teens noted they ‘could get a handgun if they wanted to.’ This access rate is higher than national school-based samples of high school students in which less than one-quarter of students reported access to a gun,(Swahn, Hammig et al. 2002; Borowsky and Ireland 2004) but is consistent with rates reported by teens living in poor inner city neighborhoods.(Callahan and Rivara 1992; Sheley and Wright 1993; Bergstein, Hemenway et al. 1996) This prevalence of handgun access is less than the 38.6% found among adolescents seeking ED care for assault-related injury only. (Cheng, Schwarz et al. 2003)

The finding that teens seeking care for a medical complaint were even more likely than those seeking care for intentional injury has implications for future prevention strategies. It should be emphasized that both groups had high rates of access to a handgun. This finding may be explained by noting that those teens seeking care today for medical complaints may have had a recent injury such as gun related injury in the past and therefore rendering chief complaint on an isolated visit not as strongly relevant as personal history and risk factors.

ED-based violent injury prevention programs often focus on patients that present with a fight-based injury, and the results of this data suggest that a substantial proportion of patients (in fact, the majority) who could potentially benefit from such interventions would not be included. For example, with the present sample, ~6% (who had an intentional injury) would be included in a prevention approach with such restrictive criteria. Teens that had been injured by a gun within the past year were 2.8 times more likely to report access to a handgun. Due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, causality cannot be determined; therefore, it is unclear if teens position themselves to have access to a handgun because of prior gun related injury for “self defense”, or if they had access to a gun or were carrying one and it therefore played a role in the prior gun related injury. These ED-based findings closely parallel findings from a school-based study showing the association between risk behaviors (fighting, drug use) and availability of handguns,(Callahan and Rivara 1992) and should be considered when clinicians treat teens in the ED who are victims of past gun-related violence.

Further, analyses revealed several other important factors associated with handgun access. For example, males were twice as likely to report handgun access as females, and individuals over the age of 16 were 2.2 times more likely to report access when compared to those under 16. These results are consistent with studies on school-based samples,(Callahan and Rivara 1992; Swahn, Hammig et al. 2002) and are generally consistent with findings that males are more likely to possess and carry handguns than females.(Sheley and Brewer 1995; Brown 2004) Similar correlates of increased access have been found when comparing older adolescents to younger ones,(Swahn, Hammig et al. 2002) and may indicate the need for ED-based interventions to focus limited resources on the older subset of the adolescent population. Employment as a correlate of access is potentially due to the fact that a job puts adolescents in contact with older friends or relatives, who are often the source of a handgun.(Grossman, Reay et al. 1999) Our results, in contrast to school-based studies,(Callahan and Rivara 1992; Swahn, Hammig et al. 2002) did not indicate receipt of public assistance or grades to be associated with access. This is possibly due to the large portion of the sample receiving public assistance. It is important to note that 41.2% of the sample had failing grades and may not be present for school based surveys or interventions. Finally, as noted, substance use, sexual activity, group fighting and prior injury by a gun were all related to adolescent handgun access; these findings are consistent with prior research on risk behavior clustering and youth delinquency.(Jessor and Jessor 1977; Irwin 1987; Jessor 1991; Gabriel, Hopson et al. 1996; Zucker, Chermack et al. 2000; Swahn, Simon et al. 2008)

Future initiatives in the ED setting may focus on reducing gun related mortality and morbidity among adolescents. There are a growing number of ED- and hospital-based injury prevention programs in place in various stages of evaluation, attempting to close the gap in violence assessment among high risk adolescents. Many of these interventions focus on identification of at-risk adolescents and improved linkage to community resources,(Datner, Fein et al. 1999; Fein, Shofer et al. 2001; Marcelle and Melzer-Lange 2001; Mitka 2002; Zun, Downey et al. 2003; Becker, Hall et al. 2004; Cunningham, Vaidya et al. 2005; Dicker 2005; Cooper, Eslinger et al. 2006) or brief intervention and referral strategies during the ED or trauma stay in an effort to target factors associated with violence (e.g., substance abuse, psychiatric problems).(Cunningham, Walton et al. 2007) Alternatively, studies show that the majority of firearms that cause injuries among adolescents are obtained in the home,(Brent, Perper et al. 1991; Grossman, Reay et al. 1999; Shah, Hoffman et al. 2000) and households with adolescents are more likely than households with younger children to store firearms unsafely.(Johnson, Miller et al. 2006) Thus, ED based injury prevention efforts could focus on parents of high-risk youth and the protective benefit that properly storing firearms and thus restricting access can have.(Grossman, Mueller et al. 2005) (Sidman, Grossman et al. 2005)

Limitations

This study was conducted in one inner city ED, and the results may not be generalizable to different community settings and types of ED’s. Although the survey was a self-report, recent reviews of studies among adolescents and young adults have concluded that reliability and validity of self-reported risk behaviors such as alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use is high,(Gray and Wish 1998; Thornberry and Krohn 2000; Buchan, M et al. 2002; Dennis, Titus et al. 2002; Brener, Billy et al. 2003) and adolescents and young adults are more likely to report sensitive information such as drug use through computerized surveys and when privacy/confidentiality is assured.(Turner, Ku et al. 1998; Wright, Aquilino et al. 1998; Webb, Zimet et al. 1999; Brener, Billy et al. 2003; Harrison, Martin et al. 2007) This study is limited by the cross-sectional nature of data collection, which does not allow for causal attributions about gun access to be made. Our exclusion of adolescents presenting with acute suicidal attempt or ideation means the rates presented may be an underestimate of rates of true weapons related behaviors. In addition, adolescents presenting during the overnight shift were not included in the study sample, and therefore were not accounted for in the data. Finally, several relevant variables were not able to be assessed in our study (e.g., location of handgun access, handgun use, etc.) and should be included in future studies.

Conclusions

This study adds to the current literature by illustrating high rates of handgun access among a large ( ~3000) systematic sample of adolescents seeking care in an inner city ED, including those seeking care for non-injury related presenting complaint, and by demonstrating associations between handgun access and several demographic and behavioral risk factors. One-third of all adolescents, and 40% of the male adolescents, seeking care in an inner city ED reported access to a handgun. ED clinicians and injury prevention initiatives should consider that older males with a history of substance use, past-year gun injury, and past year fighting were more likely to have with access to a handgun to inform future ED-based injury prevention strategies.

Figure 1.

Recruitment Flowchart: September 2006 – June 2008

Acknowledgements

Kevin Loh has full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This project was supported by a grant (#014889) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). We would like to thank project staff Bianca Burch, Yvonne Madden, Tiffany Phelps, Carrie Smolenski, and Annette Solomon for their work on the project; also, we would like to thank Pat Bergeron for administrative assistance and Linping Duan for statistical support. Finally, special thanks are owed to the patients and medical staff at Hurley Medical Center for their support of this project.

This manuscript was awarded a "Best Student Paper Award" from the Injury Control and Emergency Health Services Section of the American Public Health Association, 2009. The award was sponsored, in part, by the Liberty Mutual Research Institute for Safety. Contents of this effort are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the American Public Health Association or the Liberty Mutual Research Institute for Safety.

Abbreviations

- ED

Emergency Department

- CI

Confidence Interval

- RA

Research Assistant

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Academy of Family Physicians. [Retrieved April 8, 2008];Violence [position paper] 2000 from http://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/policy/policies/v/violencepositionpaper.html.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Violence. The role of the pediatrician in youth violence prevention in clinical practice and at the community level. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1):173–181. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Practice resources - Violence. [Retrieved April 8, 2008];2007 from http://www.acep.org/practres.aspx?id=29848.

- American Medical Association. AMA violence-related reports and policies. [Retrieved April 8, 2008];1995 2008, from http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/3247.html.

- Annest JL, Mercy JA, et al. National estimates of nonfatal firearm-related injuries. Beyond the tip of the iceberg. JAMA. 1995;273(22):1749–1754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaman V, Annest JL, et al. Lethality of firearm-related injuries in the United States population. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(3):258–266. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(00)70077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MG, Hall JS, et al. Caught in the crossfire: the effects of a peer-based intervention program for violently injured youth. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34(3):177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstein JM, Hemenway D, et al. Guns in young hands: a survey of urban teenagers' attitudes and behaviors related to handgun violence. J Trauma. 1996;41(5):794–798. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199611000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky IW, Ireland M. Predictors of future fight-related injury among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):530–536. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky IW, Mozayeny S, et al. Effects of a primary care-based intervention on violent behavior and injury in children. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):e392–e399. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Billy JO, et al. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: evidence from the scientific literature. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(6):436–457. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Perper JA, et al. The presence and accessibility of firearms in the homes of adolescent suicides. A case-control study. JAMA. 1991;266(21):2989–2995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B. Juveniles and Weapons: Recent Research, Conceptual Considerations, and Programmatic Interventions. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2004;2(2):161–184. [Google Scholar]

- Buchan BJ, L. D. M, et al. Cannabis use: consistency and validity of self-report, onsite urine testing and laboratory testing. Addiction. 2002;97 Suppl 1:98–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CM, Rivara FP. Urban high school youth and handguns. A school-based survey. JAMA. 1992;267(22):3038–3042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Atlanta, GA: Division of Adolescent and School Health (DASH); 1993a. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. [Retrieved March 28, 2008];Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]. Ten leading causes of death. United States 2005. 2005 2005 from www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars.

- Cheng TL, Johnson S, et al. Assault-injured adolescents presenting to the emergency department: causes and circumstances. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(6):610–616. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TL, Schwarz D, et al. Adolescent assault injury: risk and protective factors and locations of contact for intervention. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):931–938. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TL, Wright JL, et al. Randomized trial of a case management program for assault-injured youth. Ped Emerg Care. 2008;24(3):130–136. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181666f72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Colby SM, et al. Alcohol use disorders identification test: factor structure in an adolescent emergency department sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(2):223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Eslinger DM, et al. Hospital-based violence intervention programs work. J Trauma. 2006;61(3):534–540. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000236576.81860.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham R, Walton MA, et al. SafERTeens: Computerized screening and brief intervention for teens at-risk for youth violence. [abstract #264]. 2007 Annual Meeting Society for Academic Emergency Medicine; Chicago, IL. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham RM, Vaidya RS, et al. Training emergency medicine nurses and physicians in youth violence prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(5 Suppl 2):220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg LL. Youth violence in the United States. Major trends, risk factors, and prevention approaches. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):259–272. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datner E, Fein J, et al. Violence intervention project: Linking healthcare facilities with community-based resources. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:511. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Titus JC, et al. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) experiment: rationale, study design and analysis plans. Addiction. 2002;97 Suppl 1:16–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicker R. Violence prevention for trauma centers: A feasible start [Poster 2901] Injury and Violence In America: Denver, CO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DuRant RH, Kahn J, et al. The association of weapon carrying and fighting on school property and other health risk and problem behaviors among high school students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(4):360–366. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170410034004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States 2006: Uniform Crime Report 2006. 2006 from http://www.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2006/index.html.

- Fein JA, Shofer FS, et al. Telephone follow-up for victims of youth violence: is it possible. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(5):459. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel RM, Hopson T, et al. Building relationships and resilience in the prevention of youth violence. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12(5 Suppl):48–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert EH, Lowenstein SR, et al. Chart reviews in emergency medicine research: Where are the methods? Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27(3):305–308. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray TA, Wish ED. Substance Abuse Need for Treatment among Arrestees (SANTA) in Maryland. College Park, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Research; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman DC, Mueller BA, et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA. 2005;293(6):707–714. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.6.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman DC, Reay DT, et al. Self-inflicted and unintentional firearm injuries among children and adolescents: the source of the firearm. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(8):875–878. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.8.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy MS. Keeping children safe around guns: Pitfalls and promises. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11(4):352–366. [Google Scholar]

- Harris K, Florey F, et al. The national longitudinal study of adolescent health: Research design [WWW document] [Retrieved 2008, May 21];2003 from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- Harrison LD, Martin SS, et al. Comparing drug testing and self-report of drug use among youths and young adults in the general population. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes DN, Sege R. FiGHTS: a preliminary screening tool for adolescent firearms-carrying. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(6):798–807. doi: 10.1016/S0196064403007224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin CE. Adolescent Social Behavior and Health: New Directions for Child Development. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Jelalian E, Alday S, et al. Adolescent motor vehicle crashes: the relationship between behavioral factors and self-reported injury. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27(2):84–93. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12(8):597–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem Behavior and Psychological Development: A Longitudinal Study of Youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RM, Miller M, et al. Are household firearms stored less safely in homes with adolescents?: Analysis of a national random sample of parents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(8):788–792. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.8.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, et al. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse: 699; Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2006. Volume 1: Secondary school students. 2007

- Lowry R, Powell KE, et al. Weapon-carrying, physical fighting, and fight-related injury among U.S. adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(2):122–129. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(97)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcelle DR, Melzer-Lange MD. Project UJIMA: working together to make things right. WMJ. 2001;100(2):22–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michigan Department of Community Health. Census 2000. 2002 10/31/2002 from http://www.mdch.state.mi.us/pha/osr/CHI/POP/Fcensus2.ASP, 10/31/2002.

- Mitka M. Hospital study offers hope of changing lives prone to violence. Jama. 2002;287(5):576–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics & U.S. Health Care Financing Administration. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification: ICD-9-CM. Washington, D.C: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sege R, Stringham P, et al. Ten years after: examination of adolescent screening questions that predict future violence-related injury. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24(6):395–402. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S, Hoffman RE, et al. Adolescent suicide and household access to firearms in Colorado: results of a case-control study. J Adolesc Health. 2000;26(3):157–163. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheley JF, Brewer VE. Possession and carrying of firearms among suburban youth. Public Health Rep. 1995;110(1):18–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheley JF, Wright JD. Gun Acquisition and Possession in Selected Juvenile Samples. N. I. o. Justice. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquent Prevention; 1993. p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Sidman EA, Grossman DC, et al. Evaluation of a community-based handgun safe-storage campaign. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):e654–e661. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon TR, Richardson JL, et al. Prospective psychosocial, interpersonal, and behavioral predictors of handgun carrying among adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(6):960–963. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.6.960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman KJ, Zimmerman MA. Episodic and persistent gun-carrying among urban African-American adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32(5):356–364. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn MH, Hammig BJ, et al. Prevalence of youth access to alcohol or a gun in the home. Inj Prev. 2002;8(3):227–230. doi: 10.1136/ip.8.3.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn MH, Simon TR, et al. Linking dating violence, peer violence, and suicidal behaviors among high-risk youth. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(1):30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Krohn MD. The self-report method of measuring delinquency and crime. In: Duffee D, editor. Measurement and Analysis of Crime and Justice: Criminal Justice 2000. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 2000. pp. 33–83. [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, et al. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280(5365):867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton M, Goldstein AL, et al. Brief Alcohol Intervention in the Emergency Department: Moderators of Effectiveness. J Stud Alcohol. 2008;69(4):550–560. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb PM, Zimet GD, et al. Comparability of a computer-assisted versus written method for collecting health behavior information from adolescent patients. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24(6):383–388. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KM, Klein JD. Adolescents who use the emergency department as their usual source of care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(4):361–365. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright DL, Aquilino WS, et al. A Comparison of Computer-Assisted and Paper-and-Pencil Self-Administered Questionnaires in a Survey on Smoking, Alcohol, and Drug Use. Public Opin Q. 1998;62(3):331–353. [Google Scholar]

- Wright MA, Wintemute GJ, et al. Gun suicide by young people in California: descriptive epidemiology and gun ownership. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(6):619–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA, Morrel-Samuels S, et al. Guns, Gangs, and Gossip: An Analysis of Student Essays on Youth Violence. J Early Adolescence. 2004;24(4):385–411. [Google Scholar]

- Zimring FE. The Medium Is the Message: Firearm Caliber as a Determinant of Death from Assault. The Journal of Legal Studies. 1972;1(1):97. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Chermack ST, et al. Alcoholism: A lifespan perspective on etiology and course. In: Sameroff AJ, Lewis M, Miller R, editors. Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology. New York: Plenum; 2000. pp. 569–587. [Google Scholar]

- Zun LS, Downey LV, et al. Violence prevention in the ED: linkage of the ED to a social service agency. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21(6):454–457. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(03)00102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]