Abstract

Cluster of differentiation (CD)4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) exert a suppressive activity on atherosclerosis, but the underlying mechanism remains unclear. Here, we investigated whether and how Tregs affect macrophages foam-cell formation. Tregs were isolated by magnetic cell sorting-column and analyzed by flow cytometry. Macrophages were cultured with or without Tregs in the presence of oxidized LDL (oxLDL) for 48 h to transform foam cells. After co-culture with Tregs, macrophages showed a decrease in lipid accumulation, which was accompanied by a significantly downregulated expression of CD36 and SRA but no obvious difference in ABCA1 expression. Tregs can inhibit the proinflammatory properties of macrophages and steer macrophage differentiation toward an anti-inflammatory cytokine producing phenotype. Mechanistic studies reveal that both cell-to-cell contact and soluble factors are required for Treg-mediated suppression on macrophage foam-cell formation. Cytokines, interleukin-10 (IL-10), and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) are the key factors for these suppressive functions.

Keywords: CD4+CD25+ Tregs, macrophage foam cell, atherosclerosis, scavenger receptor

INTRODUCTION

Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease of the arterial wall where both innate and adaptive Th1-driven immunoinflammatory responses contribute to disease development. Th2-related responses have been shown to be either protective or pathogenic (1–3). The role of the immune system in atherosclerosis has received considerable interest in recent years; however, sufficient knowledge to justify the immunomodulatory mechanisms has not yet been obtained.

In recent years, a novel subtype of T cell, called regulatory T cells (Tregs), have been shown to play a critical role in the development of atherosclerosis. Natural Tregs, characterized by the expression of cluster of differentiation (CD)4, CD25, and the forkhead-winged-helix (Foxp3) transcription factor, have the capacity to contribute to the maintenance of immunological tolerance against self and non-self antigens and prevent the development of various immunoinflammatory diseases (4–7). Several preliminary studies have described an important role for this type of regulatory T cell response in atherosclerosis (8–11). In a recent study by Ait-Oufella et al., it was suggested for the first time that naturally arising CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells are powerful inhibitors of atherosclerosis in several mouse models (8). This finding was strongly supported by observations that Treg numbers were reduced and their functional suppressive properties were compromised in experimental atherosclerosis and in patients with atherosclerosis (9–11). Moreover, our recent research has shown that generation of HSP60-specific Tregs could inhibit the formation of plaques in murine atherosclerosis (12), which was consistent with similar findings from Harats et al. that induction of oral tolerance with antigen-specific Tregs could attenuate experimental atherogenesis (13).

Tregs on the adaptive immune system and on CD4+ T cells, in particular, have been well documented (1, 2). But their effects on innate immune cells are less well known. Monocytes and macrophages are essential partners in innate and acquired immunity and as such play a variety of roles in atherosclerotic plaque development and its clinical sequelae (14). The uptake of oxidized lipoproteins via scavenger receptors and the ensuing formation of foam cells are key events in atherogenesis (15). Recent studies have implicated that CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells induce alternative activation of monocytes/macrophages (16). Identification and characterization of Tregs regulating the foam-cell formation, particularly genes involved in lipids accumulation, could be crucial in deciphering the effects and mechanisms of Tregs in atherosclerosis. Here we assessed a previously uncharacterized function of CD4+CD25+ Tregs, namely, their ability to modulate the transition of macrophages into foam cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All C57BL/6 background mice were obtained from Peking University. They were housed in the specific pathogen-free conditions in our animal facility and administered food and water ad libitum. The investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996) and is approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Preparation of LDL and copper-oxidized LDL

Blood for lipoprotein isolation was collected in EDTA (1 mg/ml) from normal lipidemic donors after 12 h of fasting. LDL (density = 1.03 to 1.063 g/l) was isolated from the plasma after density adjustment with KBr, by preparative ultracentrifugation at 5,000 rpm/min for 22 h, using type 50 rotor. They were dialyzed against PBS containing 0.3 mM EDTA, sterilized by filtration through a 0.22-mm filter, and stored under nitrogen gas at 4°C. Protein content was determined by the method of Lowry et al. Copper oxidation of LDL was performed by incubation of postdialyzed LDL (1 mg of protein/ml in EDTA-free PBS) with copper sulfate (10 mM) for 24 h at 37°C. Lipoprotein oxidation was confirmed by analysis of thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (17).

Cell isolation and purification

For cells isolation, groups of 8- to 12-week-old male mice were used for all experiments. Murine peritoneal macrophages were harvested after intraperitoneal injection (5 ml per mouse) of PBS. After centrifugation at 1000 g for 5 min, the cells were resuspended into complete RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS and 100 U/ml of penicillin/streptomycin, then adjusted to the concentration of 1 × 106/ml and used for further experiments.

Splenocytes were prepared from murine spleens by Ficoll density gradient. CD4+ T cells were isolated from total splenocytes by negative selection using LD column (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Purified CD4+ T cells were incubated with anti-mouse CD25 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech) and separated into CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− fractions by positive selection using MS column (Miltenyi Biotech). The positively selected CD25+ cell fractions were separated again over an MS column to achieve higher purities. As assessed by using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Becton-Dickinson, Oxnard, NJ), purities of CD4+CD25− T cells and CD4+CD25+ T cells were > 95% and > 90%, respectively. To further confirm the identity of these Tregs, the primers (5′-ACA CCA CCC ACC ACC GCC ACT-3′ and 5′-TCG GAT GAT GCC ACA GAT GAA GC-3′) were used to measure the expression of Foxp3 mRNA, which were highly expressed in CD4+CD25+ T cells but not in CD4+CD25− T cells in our work.

Co-culture experiments

Murine peritoneal macrophages were seeded in 6-well plates (3–4 × 106/well), nonadherent cells were removed, and the culture medium was changed first after 8 h incubation at 37°C. For co-culture experiment, peritoneal macrophages were cultured without T cells (no T), with CD4+CD25+ T cells (CD25+), or CD4+CD25− T cells (CD25−) for 40 h in the presence of anti-CD3 antibody (50 ng/ml, eBioscience, CA) (16), then the different cultures were stimulated for 48 h with oxLDL (50 μg/ml) to induce foam-cell formation. After the incubation period, floating T cells were aspirated, lipid-loaded macrophages were harvested, and supernatants were collected for further experiments.

Macrophage lipid analysis by oil red O–staining

Immediately following 48 h incubation with oxLDL, the medium containing floating T cells was aspirated, and lipid-loaded cells were fixed in the same 6-well plates used for incubation, with 4% paraformaldehyde in water, for 2–4 min. Cells were stained with 0.3% oil red O in methanol for 15 min. Cells were observed under a phase contrast microscope with 200× magnification and then photographed. The number of foam cells formed under each condition was calculated manually and presented as a percentage foam-cell formation. At least 10 microscopic fields were counted from three different slides for the same treatment for quantification of foam cells.

Quantification of lipid accumulation was achieved by extracting oil red O from stained cells with isopropyl alcohol and measuring the OD of the extracts at 510 nm.

Cellular lipid analysis

After the incubation period, medium containing floating T cells was abandoned, and macrophages were removed from the culture plates and washed three times with PBS. Then intracellular lipids were extracted using isopropanol/hexane. Cellular lipid concentrations were determined by enzymatic colorimetric assays using kits (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA) for total cholesterol (TC) and for free cholesterol (FC). Esterified cholesterol (CE) mass was calculated as the difference between TC and FC. Protein concentration was measured by the method of Lowry (18).

Cholesterol efflux

Macrophages were seeded and incubated in 1640 plus 10% FBS containing 50 μg/ml oxLDL and 2μCi/ml [3H]cholesterol as described previously (19). After a 24-h incubation period, cells were washed and co-cultured with or without Tregs in serum-free medium. Cholesterol efflux was performed for another 24 h in the presence of ApoA-I (10 μg/ml, Sigma). The cholesterol efflux was expressed as the percentage of the radioactivity released from the cells to the medium relative to the total radioactivity in cells plus medium containing anti-CD3 antibody (50 ng/ml). Each experiment was carried out in triplicate and repeated three times.

RNA analysis

Total RNA from macrophages was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instruction. One microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using murine Moloney leukemia virus (M-MLV) (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan), and the resulting cDNA was used as a PCR template. Semi-quantitative PCR was performed using ReverTra Dash kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) with the primers for GAPDH (5′-GAG GGG CCA TCC ACA GTC TTC-3′ and 5′-CAT CAC CAT CTT CCA GGA GCG-3′), CD36 (5′-GTT TTA TCC TTA CAA TGA CA-3′ and 5′-GGA AAT GTG GAA GCG AAA TA-3′), SRA (5′-AAA GGG AGA CAG AGG GCT CAC-3′ and 5′-CTT GAT CCG CCT ACA CT-3′), and ABCA1 (5′-ACA ACC AAA CCT CAC ACT ACT G-3 and 5′-ATA GAT CCC ATT ACA GAC AGC G-3′). The amplified DNA was analyzed on 2% agarose gel and then visualized with ethidium bromide staining. Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out with ABI PRISM 7900 Sequence Detector system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. GAPDH was used as endogenous control. PCR reaction mixture contained the SYBR Green I (Takara Biotechnology), cDNA, and the primers. Relative gene expression level (the amount of target, normalized to endogenous control gene) was calculated using the comparative Ct method formula 2−ΔΔCt. The sequences of primers for real-time PCR were GAPDH (5′- CCA TCA CCA TCT TCC AGG AGC AGC GAG-3′ and 5′- CAC AGT CTT CTG GGT GGC AGT GAT-3′), CD36 (5′- GTA CAG ATT TGT TCTT CCA GCC AAT-3′ and 5′- TCA GTC CAG AAA CAA TGG TTG TC-3′), SRA (5′-AGA ATT TCA GCA TGG CAA CTG-3′ and 5′-ACG GAC TCT GAC ATG CAG TG-3′), and ABCA1 (5′- CGT TTC CGG GAA GTG TCC TA-3, 5′-CTA GAG ATG ACA AGG AGG ATG GA-3′).

Western blot analysis

After incubation with oxLDL, the serum containing floating T cells was discarded. The remnant macrophages were washed with precooled PBS, centrifuged at 4°C 3000 rpm for 5 min, lysed in ice-cold buffer containing 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM sodium EDTA, 0.1 mM sodium EGTA, 1.0 mM DTT, 1.0 mM PMSF, and 1 mg/ml protease inhibitor aprotinin for 30 min and centrifuged at 4°C 2000 rpm for 10 min. The protein concentration in cellular supernatants was determined by the Lowry assay. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were separated on 9% SDS-polyacrylamide (SDS-PAGE) gels and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose (NC) membrane and blocked 2 h (5% “degrease milk powder” in Tween/PBS buffer; vacillating bed; and room temperature) and, after incubation with first and second antibodies, were detected by ECL (Pierce Biotech). Bands were normalized to β-actin and expressed as a percent of control. Primary antibodies were used in different dilutions as follows: anti-SRA (scavenger receptor A) 1:250 (mouse monoclonal; Santa Cruz), anti-CD36 (membrane glycoprotein belonging to the class B scavenger receptor family) 1:300 (mouse monoclonal), anti-ABCA1 (ATP-binding cassette transporter A1) 1:300 (mouse monoclonal), anti-β-actin 1:500 (goat monoclonal).

ELISA assay for cytokines

The peritoneal macrophages were collected and co-culture experiments were performed as described in the previous section. To exclude possible contributions of T cell–derived cytokines in these assays, medium containing floating T cells were aspirated and fresh medium was changed before incubation with oxLDL. Supernatants were collected after 48 h incubation and kept frozen at −80°C until the cytokine levels (TNF-α, MCP-1, MMP-9, IL-10, and TGF-β) were determined by ELISA assays according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each sample was tested for each cytokine in triplicate.

Transwell and neutralization experiments

To assess whether cell-to-cell contact was necessary for Tregs to mediate suppression, polycarbonate 24-well Transwell inserts (Corning, Acton, MA) were used (20). Peritoneal macrophages were collected and incubated as described in the previous section. Transwell experiments were performed by culturing macrophages (3–4 × 106/well) in the lower well and CD4+CD25+ T cells (5 × 105/well) with anti-CD3 mAb in the inserts (with or without macrophages). After 40 h of co-culture, the top compartments (inserts) were removed, and oxLDL (50 μg/ml) was added to induce macrophage differentiation for 48 h. After the incubation period, cells were harvested for lipid measurement for further experiments.

To analyze whether TGF-β and IL-10 are required for Treg-mediated suppression on foam-cell formation, neutralizing IL-10 antibody (5 μg/ml) (R and D Systems) and/or TGF-β antibody (5 μg/ml) or nonblocking IgG anti-mouse control antibody were added at the start of the co-culture system. Cells were cultured for 48 h and tested for cellular esterified cholesterol mass to measure foam-cell formation.

Statistical analyses

Results are shown as mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. The significance of differences was estimated by ANOVA followed by Student–Newmann–Keuls multiple comparison tests. P < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software (version 11.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Effects of Tregs on oxLDL uptake in peritoneal macrophages

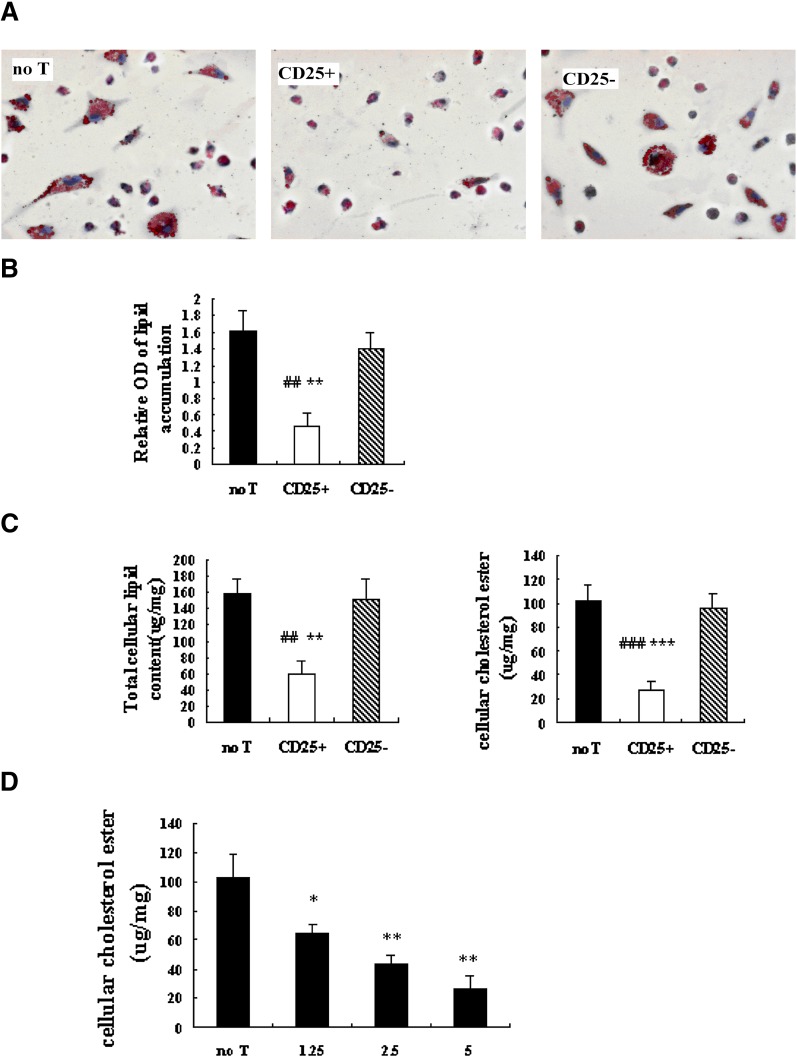

Macrophages are critical in cholesterol metabolism. Alterations in the uptake, metabolism, and efflux of cholesterol in macrophages could affect foam-cell formation, a prerequisite for atherosclerosis development. To determine if Tregs can modulate foam-cell formation, a frequently in vitro foam-cell model system was used: peritoneal macrophages co-cultured with or without T cells (CD4+CD25+ T cells or CD4+CD25− T cells) were treated with oxLDL for 48 h to induce foam-cell formation. Foam-cell formation, as identified by oil red O staining, was readily apparent in cells treated with CD4+CD25− T cells and without T cells (Fig. 1A). After treatment with Tregs, a marked decrease (13.9 ± 5.6%) in foam-cell count was observed, compared with untreated cells (52.9 ± 10.4%; P < 0.001) or CD4+CD25− T-treated cells (53.1 ± 17.2%; P < 0.001). The similar effect of Tregs was obtained when extracted Oil Red O was measured by a spectrophotometer (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effects of Tregs on oxLDL uptake in peritoneal macrophages. Macrophages(3–4 × 106/well) were cultured alone (no T), with Tregs (CD25+, 5 × 105/well), or CD4+CD25− T cells (CD25−, 5 × 105/well) for 40 h in the presence of anti-CD3 antibody (50 ng/ml), after which the different cultures were stimulated for 48 h with oxLDL (50 μg/ml). (A) Staining with oil red O allowed visualization of cytoplasmic lipid accumulation. (200× magnification). (B) Photometric measurement of lipid stained with oil red O from differentiated macrophage foam cells. (# is indicated for CD25+ versus no T; * is indicated for CD25+ versus CD25− [## = P < 0.01; ** = P < 0.01]). (C) Foam-cell formation was quantified by the total cellular cholesterol and cholesterol ester measurement. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of at least three separate experiments. (# is indicated for CD25+ versus no T; * is indicated for CD25+ versus CD25− [## = P < 0.01; ### = P < 0.001; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P < 0.001]). (D) Murine peritoneal macrophages were treated with Tregs at indicated concentrations (1.25 × 105 cells; 2.5 × 105 cells; 5 × 105 cells) in the presence of oxLDL (50 μg/ml) for 48 h. Foam-cell formation was quantified by cholesterol ester measurement. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of at least three separate experiments (* is indicated for versus no T [* = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01]).

Cellular lipid accumulation also used to quantify foam-cell formation. Compared with untreated (no T) and CD4+CD25− T-treated macrophage cells (CD25−), the lipids accumulation in CD4+CD25+ T-treated macrophage foam cells (CD25+) was significantly reduced (Fig. 1C). Total cellular cholesterol and cellular cholesteryl ester was significantly reduced in CD25+ cultures (TC = 57.46 ± 17.92 μg/mg; CE = 26.68 ± 8.88 μg/mg) relative to no T (TC = 159.48 ± 16.38 μg/mg, P < 0.01; CE = 102.54 ± 16.67 μg/mg, P < 0.001) or CD25− cultures (TC = 150.55 ± 25.11 μg/mg, P < 0.01; CE = 96.90 ± 11.95 μg/mg, P < 0.001).

To explore whether there was a threshold effect for Tregs-mediated lipid loading of cells, macrophages (3–4 × 106/well) were cultured without or with various concentration of Tregs (1.25 × 105, 2.5 × 105, 5 × 105/well), then cellular esterified cholesterol accumulation was measured. A dose-dependent effect on cellular esterified cholesterol accumulation was noted in macrophage foam cells after 48 h incubation with oxLDL (Fig. 1C). It seems that there was not a threshold effect on cellular esterified cholesterol accumulation with suggested concentration of Tregs.

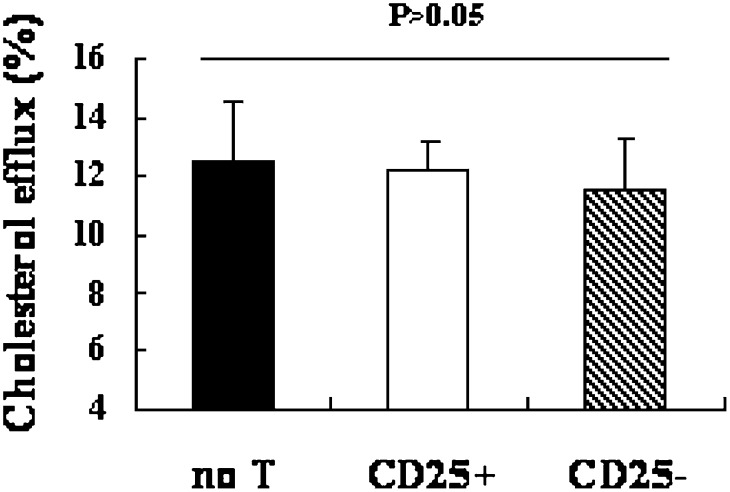

Cholesterol efflux in macrophage-derived foam cells

A decrease in cholesterol accumulation in macrophages could be due to a decrease in cholesterol uptake or an increase in cholesterol efflux. Therefore, the rate of cholesterol efflux from macrophage foam cells was determined. There was no difference detected in the cholesterol-efflux rate in untreated, CD4+CD25+ Treg-treated, and CD4+CD25− T-treated foam cells (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2), indicating that the reduced accumulation of oxLDL in macrophage foam cells was probably due to a decrease in cholesterol uptake.

Fig. 2.

Effect of Tregs on rate of cholesterol efflux in macrophage foam cells. Macrophages (3–4 × 106/well) were incubated with oxLDL and [3H] cholesterol, then co-cultured with or without Tregs (5 × 105/well). The efflux of cholesterol was initiated by addition of ApoA-I. The percentage of efflux was expressed as the percentage of the radioactivity released from the cells in the medium relative to the total radioactivity in cells plus medium. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of at least three separate experiments.

Effects of Tregs on expression of genes involved in cholesterol homeostasis in peritoneal macrophages

Previous studies (20) demonstrated that scavenger receptor class A (e.g., SR-AI/II) and class B (e.g., CD36) are the principal receptors responsible for binding and uptake of modified LDL, while the efflux of cholesterol in macrophages mediated by ApoA-I largely depends upon the activated transporter ABCA1 (21, 22).

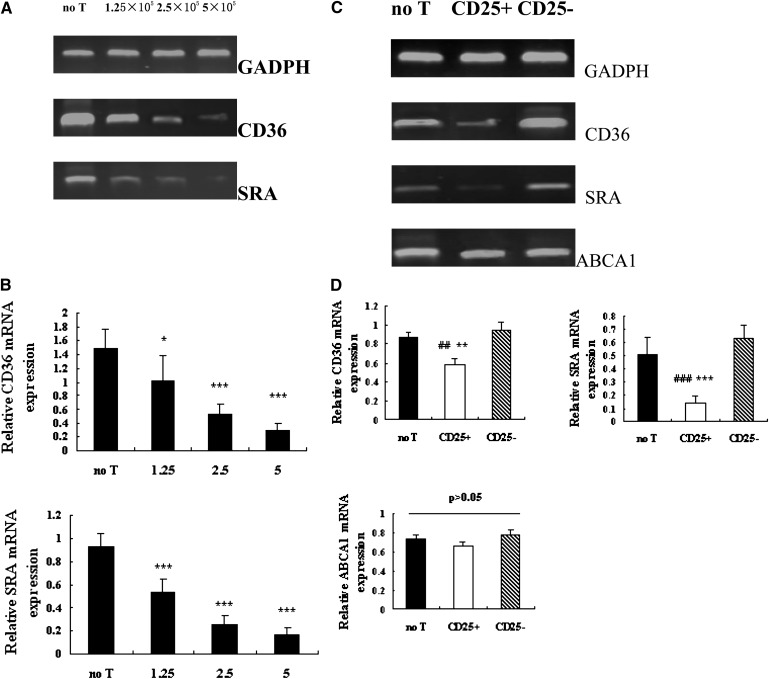

Thus, we further investigated whether the expression of genes involved in cholesterol homeostasis was altered in these macrophage foam cells. Macrophages (3–4 × 106/well) were cultured without or with various concentration of Tregs (1.25 × 105, 2.5 × 105, 5 × 105/well). The mRNA levels of SR-A, CD36, and ABCA1 were determined by semi-quantitative PCR and quantitative real-time PCR analysis.

Fig. 3 shows that Treg-treated macrophage foam cells displayed a strong downregulation of CD36 and SRA mRNA expression. A dose-dependent effect on CD36 and SRA expression was noted in macrophage foam cells after 48 h determined by RT-PCR and quantitative real-time PCR (Fig. 3A, B). Indeed, we found Tregs dose-dependently inhibit oxLDL-induced CD36 and SRA expression relative to untreated cells. At 1.25 × 105 cells, Tregs decreased expression of CD36 by 31% (P < 0.01) and SRA by 42% (P < 0.001) in macrophage foam cells compared with untreated cells (no T). But no significant difference in ABCA1 mRNA expression was detected in cultures incubated with various concentrations of Tregs and untreated cells (P > 0.05) (date not shown).

Fig. 3.

Effects of Tregs on CD36, SRA, and ABCA1 mRNA expression in macrophage foam cells. (A) Murine peritoneal macrophages were treated with CD4+CD25+ Tregs at indicated concentrations (1.25 × 105 cells; 2.5 × 105 cells; 5 × 105 cells) in the presence of oxLDL (50 μg/ml) for 48 h. Total RNA was collected and CD36 and SRA mRNA were analyzed by semi-quantitative PCR. GADPH served as endogenous control. (B) Cells were cultured as described as above. Quantitative realtime PCR analysis of CD36 and SRA mRNA relative to GAPDH was performed with equal loading of samples from indicated cultures. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of triplicate wells and are representative of at least three independent experiments. (* is indicated for versus no T [* = P < 0.05; *** = P < 0.001]). Co-cultures were set up as described in Fig. 1. Total RNA was collected. CD36, SRA, and ABCA1 mRNA were analyzed by semi-quantitative PCR (C) and realtime PCR (D). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of triplicate wells and are representative of at least three independent experiments. (# is indicated for CD25+ versus no T; * is indicated for CD25+ versus CD25− [## = P < 0.01; ### = P < 0.001; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P < 0.001]).

To demonstrate whether the expression of genes involved in cholesterol homeostasis was altered in these macrophage foam cells, peritoneal macrophages were treated without T cells, with 5 × 105 CD4+CD25+ T cells or with 5 × 105 CD4+CD25− T cells in the presence of oxLDL (50 μg/ml). As quantified by real-time PCR, the mRNA expression of CD36 and SR-A were markedly reduced in CD25+ cultures compared with those without T cells (CD36 = P < 0.01; SR-A = P < 0.001) or CD25− cultures (CD36 = P < 0.01; SR-A = P < 0.001). There was no difference in ABCA1 among these three cultures (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3D).

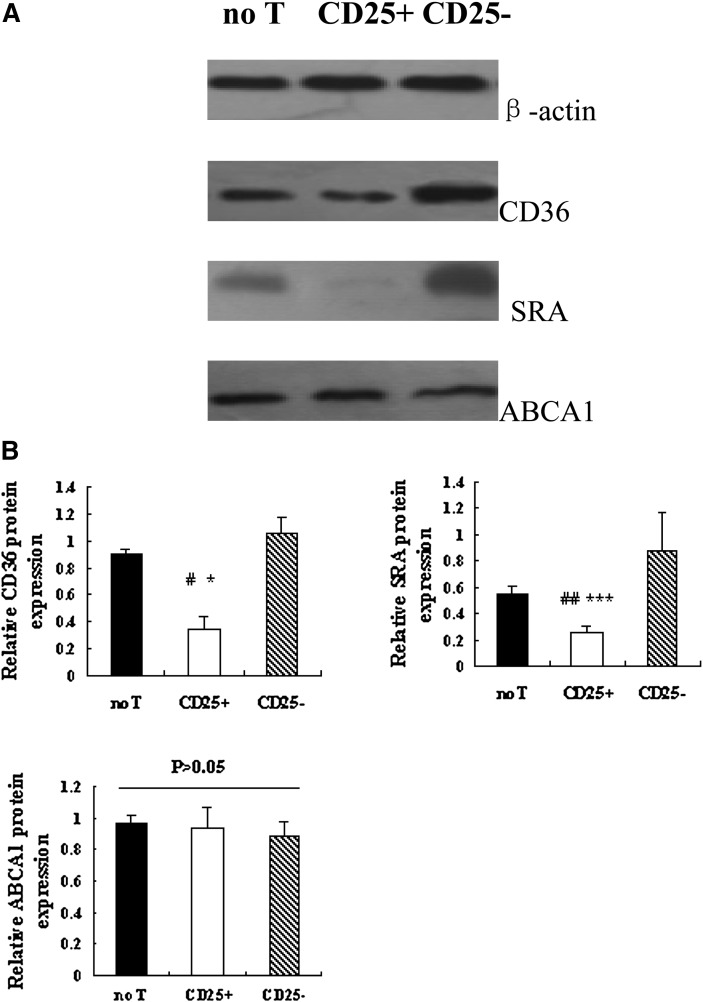

Effects of Tregs on expression of protein involved in cholesterol homeostasis in peritoneal macrophages

The protein levels of SR-A and CD36 of the macrophages were also determined by Western blot analysis. Coincident with the decreased CD36 and SR-A mRNA expression, a significant reduction of CD36 and SR-A protein expression was detected in CD25+ cultures relative to no T (CD36 = P < 0.05; SR-A = P < 0.01) and CD25− (CD36 = P < 0.05; SR-A = P < 0.001) cultures (Fig. 4A, B). Western blotting of these macrophage lysates did not detect any change in protein levels of ABCA1 (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4A, B).

Fig. 4.

Effects of Tregs on CD36, SRA, and ABCA1 protein expression. Co-culture was set up as described in Fig. 1. (A) CD36, SRA, and ABCA1 protein was analyzed by Western blotting. (B)The intensities of CD36, SRA, and ABCA1 protein level were normalized with β-actin. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. (# is indicated for CD25+ versus no T; * is indicated for CD25+ versus CD25− [# = P < 0.05; ## = P < 0.01; * = P < 0.05; *** = P < 0.001]).

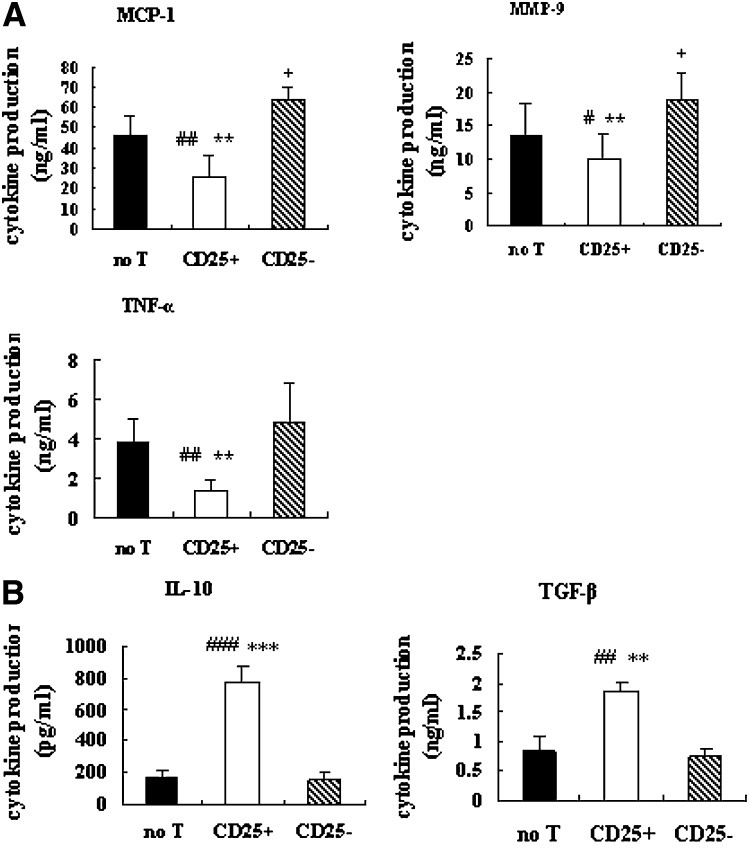

Tregs inhibit the proinflammatory response in oxLDL-induced macrophage foam-cell formation

Next we determined the capacity of inflammatory response in oxLDL-induced macrophage foam-cell formation. Our data show that, after co-culture with Tregs, macrophages displayed a decrease in their capacity to produce proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines (TNF-α, MCP-1, and MMP-9) (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokines TGF-β and IL-10 was enhanced (Fig. 5B) in Treg-treated cultures. As a control, CD4+CD25− T-treated cultures displayed an increased production of proinflammatory and decreased production of anti-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines. Results collectively indicated that rather than inhibiting a proinflammatory response, Tregs could induce an anti-inflammatory response in oxLDL-induced macrophage foam-cell formation.

Fig. 5.

Tregs inhibit the proinflammatory response of macrophages to oxLDL. Macrophages were cultured as described in the Fig. 1. After 48 h of incubation with oxLDL, cytokine/chemokine production was measured by ELISA (TNF-α, MCP-1, MMP-9, IL-10, and TGF-β). The average production of six independent experiments ± SEM of proinflammatory (A) and anti-inflammatory (B) cytokines/chemokines are shown for the three cultures. (# is indicated for CD25+ versus no T; * is indicated for CD25+ versus CD25−; + is indicated for CD25− versus no T [# = P < 0.05; ## = P < 0.01; ### = P < 0.001; * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P < 0.001; + = P < 0.05]).

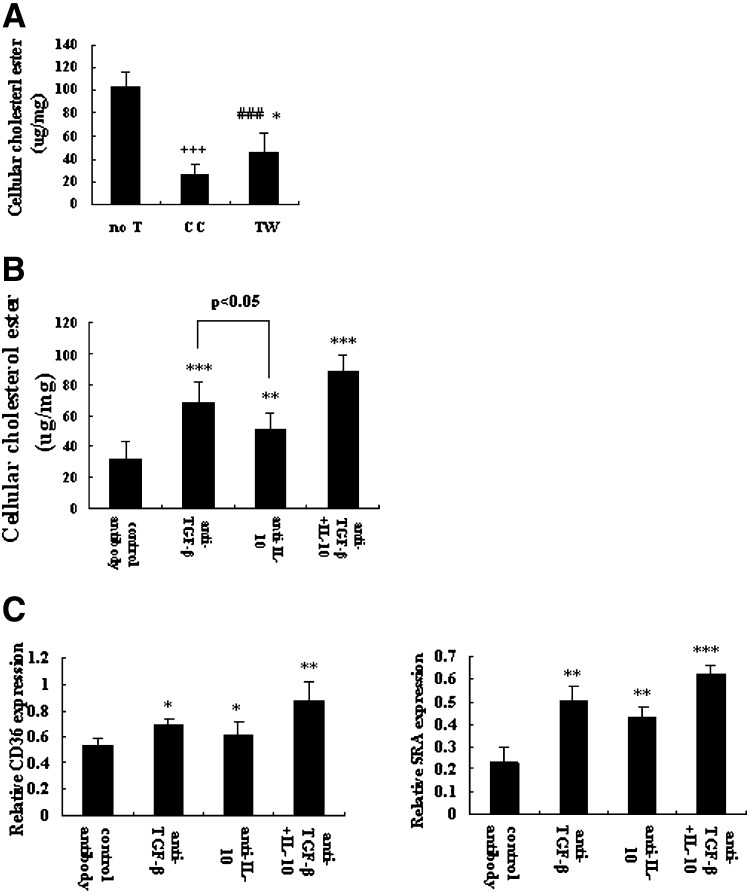

Treg-mediated suppression on macrophage foam-cell formation requires cell contact as well as soluble factors

To investigate whether suppression of macrophage foam-cell differentiation depended on cell contact or soluble factors, we cultured macrophages with or without Tregs in the presence of oxLDL in either a co-culture (CC) or a transwell system (TW). By disrupting physical contact between macrophages and Tregs (TW), the suppression of cellular esterified cholesterol (45.30 ± 17.18 μg/mg) was reversed compared with the CC system (26.68 ± 8.88 μg/mg; P < 0.05)(Fig. 6A), suggesting that cell-to-cell contact was required in Treg-mediated suppression on cellular esterified cholesterol accumulation. However, in the absence of cell-to-cell contact, cellular esterified cholesterol levels (45.30 ± 17.18 μg/mg) were still markedly reduced compared with macrophages alone (102.54 ± 16.67 μg/mg; P < 0.001) (Fig. 6A), indicating that cell-to-cell contact was only partly necessary and soluble factors may play a major role in Treg-mediated suppression on cellular esterified cholesterol accumulation.

Fig. 6.

Inhibitory mechanisms of Tregs on macrophage foam-cell formation. Macrophages (3–4 × 106/well) were cultured with or without Tregs (CD25+, 5 × 105/well) as described in Fig. 1. In some experiments, Transwell inserts were used to separate macrophages from Tregs. Neutralizing IL-10 antibody and/or TGF-β antibody or nonblocking IgG anti-mouse control antibody were added at the start of co-culture system. (A) Cellular cholesterol ester measured from macrophages cultured alone (no T), in Transwell insert (TW) or in the co-culture system (CC). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. (# is indicated for TW versus no T; * is indicated for TW versus CC; + is indicated for CC versus no T [* = P < 0.05; ### = P < 0.001; *** = P < 0.001]). (B) Cellular cholesterol ester was measured in the presence of nonblocking IgG anti-mouse antibody, neutralizing anti-IL-10, and/or anti-TGF-β antibody in the co-culture. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. (* is indicated for versus control antibody [* = P < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001]). (C) Quantitative real-time PCR was performed to measure the expression of CD36 and SRA mRNA in neutralizing experiment. GADPH served as endogenous control. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. (* is indicated for versus control antibody [* = P < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001]).

To explore the mechanism of Treg-mediated suppression on foam-cell formation, a neutralizing experiment was performed. Although it has been shown that Tregs are able to produce TGF-β and IL-10 upon stimulation (41, 42), we need to confirm that these cytokines were indeed present in our cultures. ELISA assays showed that after stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody for 40 h, CD4+CD25+ Tregs were strongly positive in the production of TGF-β and IL-10 (data not shown), which was a fundamental study for the further neutralizing experiment. For the neutralizing experiment, neutralizing IL-10 antibody and/or TGF-β antibody or nonblocking IgG anti-mouse control antibody were added to CC system. Our data show that suppression of cellular esterified cholesterol accumulation was reversed to a large degree with antibodies against IL-10 or anti-TGF-β antibody (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6B). Further, after treatment with neutralizing anti-TGF-β antibody, suppression was more readily restored relative to the addition of anti–IL-10 antibody (TGF-β antibody = 68.69 ± 12.93 μg/mg; IL-10 antibody = 50.58 ± 10.37 μg/mg; P < 0.05) (Fig. 6B). Moreover, Treg-mediated suppression of cellular esterified cholesterol accumulation was markedly abrogated when both neutralizing anti–IL-10 and neutralizing anti–TGF-β were added (IL-10/TGF-β antibody = 88.04 ± 10.95 μg/mg; control antibody = 31.85 ± 11.54 μg/mg; P < 0.001) (Fig. 6B).

In a further step, the effects of neutralizing the IL-10 antibody or TGF-β on mRNA and protein expression of CD36 and SRA were also investigated. Our data show that the downregulation of CD36 and SRA mRNA in Treg-treated macrophage foam cells was apparently reversed by adding antibodies against IL-10 or anti–TGF-β antibody, blocking of both IL-10 and TGF-β was necessary to completely abrogate suppression (Fig. 6C). A similar reversal of CD36 and SR-A protein expression was also detected when neutralizing anti–IL-10 and/or neutralizing anti–TGF-β were added (data not shown). Collectively, these data suggest that Treg-mediated suppression of macrophage foam-cell formation requires cell contact as well as soluble factors, and that soluble factors, mainly IL-10 and TGF-β, contribute largely to this suppression.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we provide evidence for a previously uncharacterized role of Tregs, namely their ability to modulate the transition of macrophages into foam cells in murine macrophages. Monocytes/macrophages play a critical role in both innate and adaptive immunity through their ability to recognize pathogens and/or “danger signals” via toll-like receptors (TLRs) and other pattern-recognition receptors. Understanding the mechanisms behind the homeostatic control of monocyte/macrophage function is, therefore, of fundamental importance. Previously, indirect evidence for Treg-mediated suppressive effects on monocytes/macrophages was provided after adoptive transfer of Tregs in a colitis model (23). Recent work by Taams (24) and others (25) demonstrated that in humans, CD4+CD25+ Tregs have direct inhibitory effects on the antigen-presenting function of monocytes/macrophages, as shown by their reduced capacity to stimulate antigen or allo-specific T-cell responses. By oil-red staining and cellular cholesterol measurement, we examined the immune effects of Tregs on macrophage differentiation into foam cells. Our data clearly showed that treatment with Tregs can significantly decrease cholesterol accumulation in macrophage foam cells by reducing oxLDL uptake in these cells. In contrast, there was no distinction in lipid accumulation between macrophage foam cells alone and macrophage foam cells treated with CD4+CD25− T cells. These results suggest that Tregs exert a suppressive effect on macrophage foam-cell formation.

Macrophage internalization of modified lipoproteins is thought to play a critical role in the initiation of atherogenesis. Two scavenger receptors, scavenger receptor A (SRA) and CD36, have been centrally implicated in this lipid uptake process. To further investigate whether CD36 and SRA were required in the suppression of macrophage foam-cell formation, we hypothesized that the mechanism of decreased foam-cell formation mediated by Tregs could be a result of Tregs regulation of one or both receptors. We then compared the scavenger receptor expression in oxLDL-induced macrophage foam cells co-cultured with or without Tregs. The effect of Tregs on scavenger receptor expression has been evaluated in a previous section. Tregs inhibited expression of both SRA and CD36. In contrast to the suppressive effects of Tregs on scavenger receptors, CD4+CD25− T cells do not alter expression of SRA and CD36. To understand to what extent Tregs modulated expression of scavenger receptors, various concentrations of Tregs were used to treat macrophages. Our data show that Tregs decreased oxLDL-induced CD36 and SRA expression in a dose-dependent manner. But a particularly intriguing finding was that the responses of SRA and CD36 were not quantitatively the same. SRA was more responsive to Tregs than CD36, especially at the protein level. Previous studies showed that mice with deletion of either of the above receptors exhibited marked reduction in atherosclerosis (26–28). These observations have led to the current dogma concerning scavenger receptors and cholesterol-laden macrophage foam cells, which is that they are proatherogenic molecules. However, recent studies have clearly revealed that the effects of scavenger receptors and macrophage foam cells on atherogenesis may be more complex, and each heterogeneity of immune-associated cells has both atherogenic and atheroprotective roles (29, 30). Although the uptake of modified lipoproteins by SRA is thought to be central to foam-cell formation, it is also widely believed to represent one of the major activation events stimulating the proinflammatory phenotype of lesional macrophages. Recently, a possible IFNγ-responsive element was identified in the human SRA gene, which apparently mediates increased mRNA expression of SRA in blood monocytes and undifferentiated THP-1 cells, a human monocyte cell line, whereas it inhibits SR-A expression in mature macrophages and differentiated THP-1 cells (31). We think that macrophage heterogeneity with respect to scavenger receptor expression and function may partly explain our results. A better picture of heterogeneity in scavenger receptor expression and function will require the development of better antibodies for use in histochemistry and more detailed phenotyping of receptor knockout mice.

Normal cellular cholesterol homeostasis, however, involves not only specific trafficking of lipid storage vesicles but also processing of excess intracellular cholesterol such that it is mediated by ABCA1, a transporter, and facilitated by ApoA-I, which transfers cholesterols to HDL, which then transports cholesterol back to the liver, a process termed reverse cholesterol transport (21, 22).

To further confirm the possible mechanism for decreased lipid accumulation in macrophage foam cells, ABCA1 expression and cholesterol efflux rate in macrophages foam cells was determined. Interestingly, our data showed no significant difference in cholesterol efflux rate, which was coincident with the unaltered ABCA1 expression in these three cultures. Collectively, these findings suggest that the suppression of Tregs on cholesterol accumulation in macrophage foam cells was attributed to a decrease in the expression of scavenge receptors SRA and CD36, rather than an increase in cholesterol efflux.

Monocyte and macrophage phenotypic diversity is important in atherogenesis. LPS, IL-1β, and Th1 cytokines, such as IFN-γ, induce a “classically” activating profile (M1), in contrast to Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-13, which lead to an “alternatively” activating profile (M2) (32–35). Activated M1 macrophages, which produce proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12, can switch to alternative M2 macrophages, which dampen the inflammatory state by producing anti-inflammatory properties, including IL-10, IL-1 receptor antagonist, and TGF-β (36). Our data showed that with oxLDL challenge, Tregs can inhibit the proinflammatory properties of macrophages and steer macrophage differentiation toward an anti-inflammatory cytokine producing phenotype compared with untreated macrophages, indicating that rather than inducing a general cytokine downregulation in macrophages, Tregs shift the balance from a proinflammatory toward an anti-inflammatory cytokine profile.

Cytokines, particularly IL-10 and TGF-β, play major roles in the generation and functions of Tregs (37–39), although their individual contributions to differentiation of Treg subsets and suppressor functions are still debated. In the initial studies, using in vitro assay systems, it was shown that strong suppressive activity exerted by CD4+CD25+ Treg requires cell-to-cell contact, and it was thus considered likely that suppression was dependent on ligand-receptor interactions at the cell surface (40–42). However, more recent research suggests that some subsets of Tregs produce cytokines IL-10 and/or TGF-β (37–39). We showed that Treg-treated cultures produced IL-10 and TGF-β and that neutralizing antibodies to these cytokines completely restored cellular cholesterol ester accumulation. The fact that cellular esterified cholesterol levels in the absence of cell-to-cell contact were still markedly reduced compared with macrophages alone combined with the completely abrogated suppression of neutralizing antibodies to IL-10 and TGF-β1, indicating that soluble factors play a central role in immune suppression mediated by Tregs. Interestingly, however, our data also show that by disrupting physical contact between macrophages and Tregs (TW), the suppression of cellular esterified cholesterol was only partly reversed compared with the CC system, suggesting that cell-to-cell contact was required for Treg-mediated suppression of foam-cell formation. Thus, it is possible that, although cell-to-cell contact contributes to suppression, it is dependent on Treg-derived cytokines, which regulate/induce mechanisms directly responsible for blocking of macrophage cell functions. Our data suggest that mechanisms involving cytokines and also requiring cell-to-cell contact contribute to suppression mediated by Tregs.

CONCLUSION

Our study shows that CD4+CD25+ Tregs may suppress macrophage foam-cell formation in part though inhibiting the uptake of oxLDL, which is likely due to decreased scavenger receptor SRA and CD36 expression rather than an increase in cholesterol efflux. Moreover, Tregs can inhibit the proinflammatory properties of macrophages and steer macrophage differentiation toward an anti-inflammatory cytokine producing phenotype. Both cell-to-cell contact and soluble factors were required for Treg-mediated suppression of macrophage foam-cell formation; IL-10 and TGF-β were the key factors for these suppressive functions. This newly discovered ability of Tregs may help us to understand the mechanisms of Tregs in atherosclerosis processes and may also provide a novel tool to manipulate atherosclerosis development.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- CD

- cluster of differentiation

- CD36

- membrane glycoprotein belonging to the class B scavenger receptor family

- CE

- esterified cholesterol

- FC

- free cholesterol

- oxLDL

- oxidized low density lipoprotein

- SRA

- scavenger receptor A

- TC

- total cholesterol

- Treg

- regulatory T cell

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation Grant No. 30670855 (L.D.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Hansson G. K. 2005. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 352: 1685–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libby P. 2002. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 420: 868–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binder C. J., Chang M. K., Shaw P. X., Miller Y. I., Hartvigsen K., Dewan A., Witztum J. L. 2002. Innate and acquired immunity in atherogenesis. Nat. Med. 8: 1218–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakaguchi S. 2005. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat. Immunol. 6: 345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindley S., Davan C. S., Bishop A., Roep B. O., Peakman M., Tree T. I. 2005. Defective suppressor function in CD4+CD25+ T-cells from patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 54: 92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao D., Malmstrom V., Baecher-Allan C., Hafler D., Klareskog L., Trollmo C. 2003. Isolation and functional characterization of regulatory CD25brightCD4+ T cells from the target organ of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur. J. Immunol. 33: 215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viglietta V., Baecher-Allan C., Weiner H. L., Hafler D. A. 2004. Loss of functional suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Exp. Med. 199: 971–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ait-Oufella H., Salomon B. L., Potteaux S., Robertson A. K., Gourdy P., Zoll J., Merval R., Esposito B., Cohen J. L., Fisson S., et al. 2006. Natural regulatory T cells control the development of atherosclerosis in mice. Nat. Med. 12: 178–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu Z., Li D., Hu Y., Yang K. 2007. Changes of CD4+CD25+ T cells in patients with acute coronary syndrome and the effects of atorvastatin. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technolog. Med. Sci. 5: 524–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mor A., Luboshits G., Planer D., Keren G., Geoge J. 2006. Altered status of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 27: 2530–2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mor A., Planer D., Luboshits G., Afek A., Metzger S., Chajek-Shaul T., Keren G., Geoge J. 2007. Role of naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in experimental atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27: 893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang K., Li D., Luo M., Hu Y. 2006. Generation of HSP60-specific regulatory T cell and effect on atherosclerosis. Cell. Immunol. 243: 90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harats D., Yacov N., Gilburd B., Shoenfeld Y., George J. 2002. Oral tolerance with heat shock protein 65 attenuates Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced and high-fat-diet-driven atherosclerotic lesions. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 40: 1333–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross R. 1993. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 362: 801–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Villiers W. J., Smart E. J. 1999. Macrophage scavenger receptors and foam cell formation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 66: 740–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiemessen M. M., Jagger A. L., Evans H. G., van Herwijnen M. J. C., John S., Taams L. S. 2007. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce alternative activation of human monocytes/macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104: 19446–19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holven K. B., Aukrust P., Holm T., Ose L., Nenseter M. S. 2002. Folic acid treatment reduces chemokine release from peripheral blood mononuclear cells in hyperhomocysteinemic subjects. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22: 699–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcil M., Yu L., Krimbou L., Boucher B., Oram J. F., Cohn J. S., Genest J. J. 1999. Cellular cholesterol transport and efflux in fibroblasts are abnormal in subjects with familial HDL deficiency. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19: 159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larigauderie G., Furman C., Jaye M., Lasselin C., Copin C., Fruchart J. C., Castro G., Rouis M. 2004. Adipophilin enhances lipid accumulation and prevents lipid efflux from THP-1 macrophages: potential role in atherogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24: 504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunjathoor V. V., Febbraio M., Podrez E. A., Moore K. J., Andersson L., Koehn S., Rhee J. S., Silverstein R., Hoff H. F., Freeman M. W. 2002. Scavenger receptors class A-I/II and CD36 are the principal receptors responsible for the uptake of modified low density lipoprotein leading to lipid loading in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 49982–49988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oram J. F., Lawn R. M. 2001. ABCA1: the gatekeeper for eliminating excess tissue cholesterol. J. Lipid Res. 42: 1173–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bortnick A. E., Rothblat G. H., Stoudt G., Hoppe K. L., Royer J., McNeish L. J. 2000. The correlation of ATP-binding cassette 1 mRNA levels with cholesterol efflux from various cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 28634–28640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maloy K. J., Salaun L., Cahill R., Dougan G., Saunders N. J., Powrie F. 2003. CD4+CD25+ Tr cells suppress innate immune pathology through cytokine-dependent mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 197: 111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taams L. S., van Amelsfort J. M., Tiemessen M. M., Jacobs K. M., de Jong E. C., Akbar A. N., Bijlsma J. W., Lafeber F. P. 2005. Modulation of monocyte/macrophage function by human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Hum. Immunol. 66: 222–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kryczek I., Wei S., Zou L., Zhu G., Mottram P., Xu H., Chen L., Zou W. 2006. Suppressive mode for regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 177: 40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nozaki S., Kashiwagi H., Yamashita S., Nakagawa T., Kostner B., Tomiyama Y., Nakata A., Ishigami M., Miyagawa J., Kameda-Takemura K., et al. 1995. Reduced uptake of oxidized low density lipoproteins in monocyte-derived macrophages from CD36-deficient subjects. J. Clin. Invest. 96: 1859–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Febbraio M., Podrez E. A., Smith J. D. 2000. Targeted disruption of the class B scavenger receptor CD36 protects against atherosclerotic lesion development in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 105: 1049–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki H., Kurihara Y., Takeya M., Kamada N., Kataoka M., Jishage K., Ueda O., Sakaguchi H., Higashi T., Suzuki T., et al. 1997. A role for macrophage scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis and susceptibility to infection. Nature. 386: 292–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson J. L., Newby A. C. 2009. Macrophage heterogeneity in atherosclerotic plaques. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 20: 370–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore K. J., Freeman M. W. 2006. Scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis: beyond lipid uptake. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26: 1702–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grewal T., Priceputu E., Davignon J., Bernier L. 2001. Identification of a g-interferonresponsive element in the promoter of the human macrophage scavenger receptor A gene. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 21: 825–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auffray C., Sieweke M. H., Geissmann F. 2009. Blood monocytes: development, heterogeneity, and relationship with dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27: 669–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosser D. M., Edwards J. P. 2008. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8: 958–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Libby P., Nahrendorf M., Pittet M. J., Swirski F. K. 2008. Diversity of denizens of the atherosclerotic plaque: not all monocytes are created equal. Circulation. 117: 3168–3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gordon S. 2007. Macrophage heterogeneity and tissue lipids. J. Clin. Invest. 117: 89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mantovani A., Sica A., Sozzani S., Allavena P., Vecchi A., Locati M. 2004. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 25: 677–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu H., Hu B., Xu D., Liew F. Y. 2003. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells cure murine colitis: the role of IL-10,TGF-β, and CTLA4. J. Immunol. 171: 5012–5017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shevach E. M. 2002. CD4+ CD25+ suppressor T cells: more questions than answers. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2: 389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura K., Kitani A., Fuss I. 2004. TGF-β1 plays an important role in the mechanism of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell activity in both humans and mice. J. Immunol. 172: 834–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakamura K., Kitani A., Strober W. 2001. Cell contact-dependent immunosuppression by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells is mediated by cell surface-bound transforming growth factor beta. J. Exp. Med. 194: 629–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levings M. K., Sangregorio R., Roncarolo M. G. 2001. Human cd25(+)cd4(+) t regulatory cells suppress naive and memory T cell proliferation and can be expanded in vitro without loss of function. J. Exp. Med. 193: 1295–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dieckmann D., Plottner H., Berchtold S., Berger T., Schuler G. 2001. Ex vivo isolation and characterization of CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells with regulatory properties from human blood. J. Exp. Med. 193: 1303–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]