Abstract

In the non-amyloidogenic pathway, amyloid precursor protein (APP) is cleaved by α-secretases to produce α-secretase-cleaved soluble APP (sAPPα) with neuroprotective and neurotrophic properties; therefore, enhancing the non-amyloidogenic pathway has been suggested as a potential pharmacological approach for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Here, we demonstrate the effects of type III secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2-III) on sAPPα secretion. Exposing differentiated neuronal cells (SH-SY5Y cells and primary rat neurons) to sPLA2-III for 24 h increased sAPPα secretion and decreased levels of Aβ1−42 in SH-SY5Y cells, and these changes were accompanied by increased membrane fluidity. We further tested whether sPLA2-III-enhanced sAPPα release is due in part to the production of its hydrolyzed products, including arachidonic acid (AA), palmitic acid (PA), and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC). Addition of AA but neither PA nor LPC mimicked sPLA2-III-induced increases in sAPPα secretion and membrane fluidity. Treatment with sPLA2-III and AA increased accumulation of APP at the cell surface but did not alter total expressions of APP, α-secretases, and β-site APP cleaving enzyme. Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that sPLA2-III enhances sAPPα secretion through its action to increase membrane fluidity and recruitment of APP at the cell surface.

Keywords: arachidonic acid, amyloid-β peptide, Alzheimer's disease

The senile plaque composed of neurotoxic amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) is a pathologic characteristic of Alzheimer's disease (AD) (1–6). In the amyloidogenic pathway, Aβ is derived from a proteolytic process of amyloid precursor protein (APP), in which APP is cleaved sequentially by β- and γ-secretases (7). Alternatively, the non-amyloidogenic pathway is mediated by α-secretase, which cleaves between amino acids 16 and 17 within the Aβ domain. This secretase is a member of the ADAM (a disintegrin and metalloprotease) family and produces a soluble fragment of APP generally regarded as α-secretase-cleaved soluble APP (sAPPα) (8, 9). Due to the neurotrophic and neuroprotective properties of sAPPα (10), increasing the APP processing by α-secretase has been suggested as a new strategy for the treatment of AD (11).

APP is a transmembrane protein, and recent studies show that APP processing can be affected by the local membrane environment. The activity of β-site APP cleaving enzyme (BACE) to produce neurotoxic Aβ is favorable in lipid rafts, which are highly ordered membrane microdomains enriched in cholesterol, sphingolipids, and saturated phospholipids (12–17). On the other hand, cleavage of APP by α-secretases is known to occur mainly in nonraft domains (18). Therefore, APP processing can be altered by manipulating membrane lipid composition, such as cholesterol and sphingolipids removals (19–22).

Phospholipases A2 (PLA2s) are ubiquitous enzymes responsible for maintenance of phospholipid homeostasis in cell membranes. Aberrant PLA2 activity has been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, Parkinson's disease, ischemia, spinal cord trauma, and head injury (23–26). Among many types of secretory PLA2s, secretory phospholipase A2 type III (sPLA2-III) has been found to express in human neuronal cells and contribute to neuronal differentiation (27). sPLA2-III from bee venom is highly homologous to the enzymatic-active central s-domain of human sPLA2-IIIs (28). This protein has been reported to alter cellular membrane properties (29). In this study, we investigate whether sPLA2-III alters sAPPα in differentiated neuronal cells, including SH-SY5Y cells and primary rat neurons, and Aβ secretion. In addition, we also examine the effects of its hydrolyzed products, i.e., arachidonic acid (AA), palmitic acid (PA), and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), on sAPPα secretion, membrane fluidity, recruitment of APP to the cell surface, as well as the expressions of α-secretases and BACE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents

DMEM with high glucose, DMEM/F12 medium (1:1), Ham's F-12 medium, FBS, penicillin, and streptomycin (pen/strep), and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Neurobasal medium, B27, and trypsin-EDTA were obtained from Gibco (Carlsbad, CA). Bee venom sPLA2-III was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). AA, LPC, PA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), DMSO, all-trans retinoic acid, and poly-l-lysine were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Farnesyl-(2-carboxy-2-cyanovinyl)-julolidine (FCVJ) was from Dr. Haidekker's Laboratory (Univerisity of Georgia) (30).

Cell culture

Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (1.0 × 105 cells/well) were seeded into 12-well plates or 1.0 ×106 cells/dish into 60 mm dishes and were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium (1:1) containing 10% FBS. For differentiation, SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to 10 μM all-trans retinoic acid for 6 days with change of fresh culture medium every 2 days.

Primary cortical neurons were prepared from embryonic day 17 Sprague-Dawley rats as described previously (31) with slightly modification. In brief, cortical neurons were enzymatically dissociated (0.05% trypsin with EDTA) and dispersed into a single-cell suspension with pasture pipette and seeded onto glass growth chambers and 6-well dishes coated with 50 mg/l poly-l-lysine. The cells were maintained in neural basal medium with 2% B27, 2 mM glutamine, and 1% pen/strep for 7 days before experiments. All cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

Cell viability by MTT test

Cell viability was determined by MTT reduction. Briefly, differentiated SH-SY5Y cells or primary neurons cultured in 12-well plates were treated with different compounds, e.g., sPLA2-III, AA, LPC, and PA. After treatment, medium was removed and 1 ml of MTT reagent (0.5 mg/ml) in DMEM was added into each well. Cells were incubated for 4 h at 37°C, and after dissolving formazan crystals with DMSO, absorption at 540 nm was measured.

Characterization of membrane fluidity by fluorescence microscopy of FCVJ-labeled cells

A fluorescent molecular rotor, FCVJ was used to measure the relative membrane fluidity in SH-SY5Y cells. FCVJ was designed to be a more membrane-compatible fluorescent molecular rotor (32) with the quantum yield strongly dependent on the local free volume. A higher fluorescent intensity of FCVJ reflects the intramolecular rotational motions being restricted by a smaller local free volume, indicating a more viscous membrane. Previously, we verified the application of FCVJ for measuring membrane viscosity by comparing the results obtained using FCVJ with those from the technique of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (30). In this study, we adapted the protocol from Haidekker et al. (32) to fluorescently label cells with FCVJ. Briefly, after undergoing different treatment protocols, e.g., sPLA2-III, AA, PA, and LPC, SH-SY5Y cells or primary neurons were washed with PBS and incubated in DMEM containing 20% FBS and 1 μM FCVJ for 20 min. Excess FCVJ was removed by washing cells with PBS three times. Fluorescence intensity measurements were performed at room temperature using a Nikon TE-2000 U fluorescence microscope with an oil immersion 60× objective lens. Images were acquired using a CCD camera controlled by a computer running MetaVue imaging software (Universal Imaging, PA). The fluorescence intensities of FCVJ per cell were measured. Background subtraction was done for all images prior to data analysis.

Western blot analysis of sAPPα released from SH-SY5Y cells and primary neurons

After treating cells with sPLA2-III or lipid metabolites for 24 h, culture medium was collected and the same volume of the cell lysate from each sample was used for Western blot analysis using β-actin as internal standard. The culture medium was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 5 min to remove cell debris, and the same volume of medium from each sample (e.g., 40 μl) was diluted with Laemmli buffer, boiled for 5 min, subjected to electrophoresis in 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk in TBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBST) and incubated overnight at 4°C in 3% (w/v) BSA with 0.02% (w/v) sodium azide in TBST with a 6E10 monoclonal antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Millipore, Billerica, MA) that recognizes residues 1–17 of the Aβ domain of human sAPPα or with a rodent specific polyclonal antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Covance, Dedham, MA). Membranes were washed three times during a 15 min period with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:2,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) in 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk in TBST at room temperature for 1 h. After washing with TBST for three times, the membrane was subjected to SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent detection reagents from Pierce (Rockford, IL) to visualize bands. The protein bands detected on X-ray film were quantified using a computer-driven scanner and Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

Western blot analysis of APP, ADAM9, ADAM10, ADAM17, and BACE1 in SH-SY5Y cells

After treatments, the protein concentration of the cell lysate was determined by BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Equivalent amounts of protein from each sample (e.g., 30 μg) was diluted with Laemmli buffer, boiled for 5 min, subjected to electrophoresis in 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk in TBST and incubated overnight at 4°C in 3% (w/v) BSA with 0.02% (w/v) sodium azide in TBST with 6E10 monoclonal antibody, anti-ADAM9 antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-ADAM10 antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Millipore), anti-ADAM17 antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti-BACE1 antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich). Membranes were washed three times during a 15 min period with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:2,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk in TBST at room temperature for 1 h. After washing with TBST for three times, the membrane was subjected to SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent detection reagents from Pierce to visualize bands. The protein bands detected on X-ray film were quantified using a computer-driven scanner and Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

Immunofluorescent staining and assessment of APP at the cell surface of SH-SY5Y cells

SH-SY5Y cells were plated onto cover slips. After differentiation and treatments, cells were fixed in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde without prior permeablization with detergent. After washing three times with PBS, nonspecific binding of antibodies was blocked by 5% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then incubated overnight at 4°C in 3% goat serum with anti-APP mouse antibody (1:200 dilution; Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI) that recognizes the N terminus of APP. The cover slips were washed with PBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with FITC-labeled goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:400) and washed with PBS. Cover slips were then mounted, and fluorescent intensity measurements were performed at room temperature using the Nikon TE-2000 U fluorescence microscope and oil immersion 60× objective lens. Images were acquired using a CCD camera controlled by a computer running MetaVue imaging software (Universal Imaging). The fluorescent intensities per cell area were measured. Background subtraction was done for all images prior to data analysis.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of APP at cell surface of SH-SY5Y cells

After differentiation and treatments, SH-SY5Y cells were detached with nonenzymatic cell dissociation solution (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA). The cells were fixed in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde without permeablization. After washing three times with PBS, nonspecific binding of antibodies was blocked by 5% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were then incubated for 2 h at room temperature in 3% goat serum with anti-APP mouse antibody (1:200 dilution; Assay Designs) that recognizes the N terminus of APP. After washing with PBS, cells were then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with FITC-labeled goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:400) and washed with PBS. Background fluorescence intensity was assessed in the absence of primary antibody. All measurements were performed on a FACScan flow cytometry system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) equipped with an argon laser. The excitation wavelength was 488 nm and emission intensity was detected with a FITC 525/30 nm filter set. A total of 10,000 cells were analyzed from each sample. Curves were generated with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences), and the median values of intensity were measured for data analysis.

Quantification of secreted Aβ1-42

After treatments, culture medium was collected, supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail, and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 5 min at 4°C to remove cell debris.

An aliquot (100 μl) of supernatant was used for Aβ1-42 quantification using an ELISA kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's recommendation. According to the instruction manual, substances including Aβ1−12, Aβ1−20, Aβ12−28, Aβ22−35, Aβ1−40, Aβ1−43, Aβ42−1, and APP have no cross-reactivity. The minimum detectable dose of Aβ1-42 is <1.0 pg/ml. The level of Aβ1-42 in each sample was measured in duplicates and expressed in pg/ml.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. Comparison between two groups was made with a Student's t-test. Comparisons of more than two groups were made with one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's post hoc tests. Values of P < 0.05 are considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Exogenous sPLA2-III and AA increased sAPPα secretion in neuronal cells

sPLA2-III hydrolyzes sn-2 fatty acids of phospholipids in cell membranes, resulting in release of PUFAs and lysophospholipids. To test whether fatty acids or lysophospholipids are responsible for the increase in sAPPα secretion and alteration of membrane fluidity, we used AA and LPC as representative polyunsaturated fatty acids and lysophospholipids, respectively. For a negative control, PA, a saturated fatty acid and not likely a hydrolyzed product of sPLA2-III, was also applied.

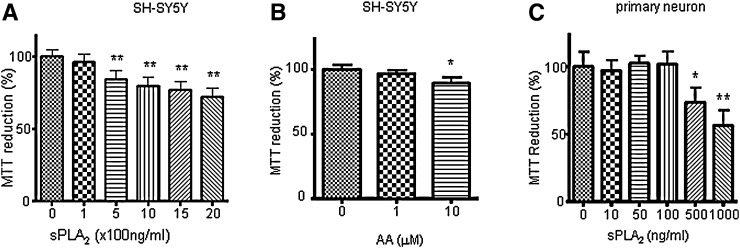

Since sPLA2-III from bee venom is highly homologous to the sPLA2-III in human (28), sPLA2-III from bee venom was used to investigate the effect of sPLA2-III on sAPPα secretion in neuronal cells in relation to membrane fluidity. We first examined the viability of SH-SY5Y cells and primary rat neurons in response to different doses of sPLA2-III using the MTT test. As shown in Fig. 1, there is a dose-dependent decrease in cell viability upon exposing SH-SY5Y cells and primary neurons to sPLA2-III for 24 h. Based on these results, subsequent studies used 100 and 500 ng/ml of sPLA2-III for treating SH-SY5Y cells and 50 and 100 ng for treating primary neurons. Similar approaches were applied to determine the concentrations of AA (Fig. 1B), PA, and LPC (data not shown) for this study. In this study, 1 and 10 μM of AA (Fig. 1B), 10 and 100 μM of PA, and 1 and 10 μM of LPC were used.

Fig. 1.

sPLA2-III and AA on the viability of neuronal cells. MTT test was applied to examine the viability of cells. MTT reduction was determined by absorption at wavelength of 540 nm for differentiated SH-SY5Y cells in medium with 1% FBS treated with sPLA2-III (A) and AA (B) for 24 h and for primary rat neurons treated with sPLA2-III (C) for 24 h. Data are expressed as percentages of control and mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments (* P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

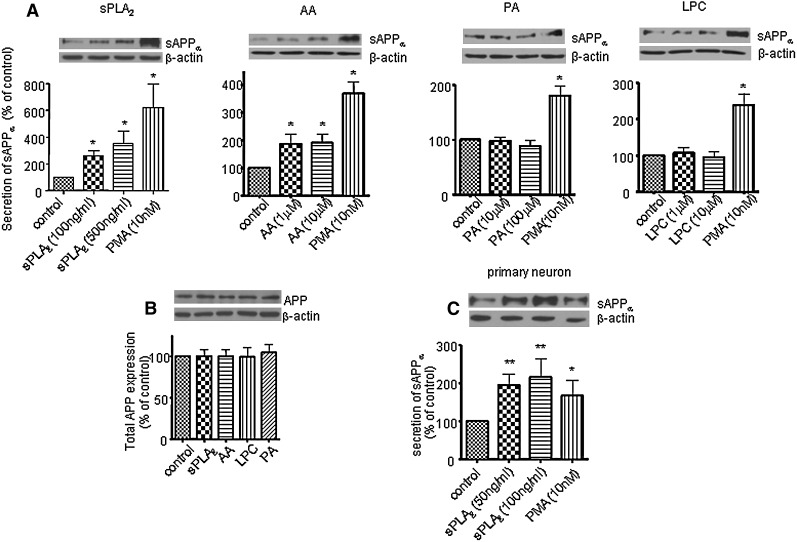

Western blot analysis showed that sPLA2-III and AA increased sAPPα secretion in SH-SY5Y cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Since it has been reported that PMA, a protein kinase C agonist, increases sAPPα secretion (33–35), treatment with PMA (10 nM) was used as a positive control. However, PA and LPC did not alter sAPPα secretion (Fig. 2A). The increase in sAPPα secretion induced by sPLA2-III and AA was not due to the change of APP content in cells as shown in Fig. 2B; exposing cells to sPLA2-III, AA, LPC, and PA for 24 h did not alter total APP expression in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the results from SH-SY5Y cells, sPLA2-III also increased sAPPα secretion in primary rat neurons (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

sPLA2-III, AA, PA, and LPC on sAPPα secretion and total APP expression in neuronal cells. A: Western blot analysis of sAPPα shows that sPLA2-III and AA increased sAPPα secretion to medium from SH-SY5Y cells, but PA and LPC did not. PMA treatment known to increase sAPPα secretion in cells was used as a positive control. B: Western blot analysis of total APP shows that sPLA2-III, AA, LPC, and PA did not alter the total APP expressions in SH-SY5Y cells. C: sPLA2-III increased sAPPα secretion to medium from primary neurons. Data are expressed as percentages of control and mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments (* P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

sPLA2-III and AA increased membrane fluidity

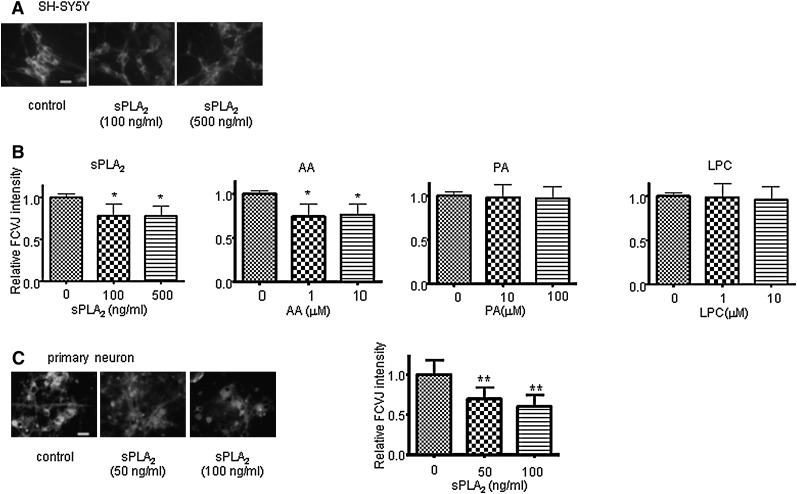

To study the effects of sPLA2-III and its hydrolyzed products on membrane fluidity, we applied a fluorescent molecular rotor, FCVJ. As explained in Materials and Methods, FCVJ integrated into a highly fluidized membrane exhibits lower quantum yield, as reflected by a lower fluorescent intensity. To validate the application of this technique for the measurement of membrane fluidity in neuronal cells, we exposed cells to ethanol, a compound known to increase membrane fluidity, and measured the fluorescent intensity of FCVJ integrated in cell membranes. Consistent with the notion that ethanol makes phospholipid bilayer membranes become more fluidized, ethanol caused a decrease in fluorescent intensity of FCVJ in SH-SY5Y cell and primary rat neuron membranes (data not shown). After treatment with sPLA2-III and AA, cells exhibited a lower fluorescent intensity of FCVJ compared with control (Fig. 3A, B), indicating that sPLA2-III and AA increased membrane fluidity in SH-SY5Y cells. These results are in agreement with the ability for sPLA2-III to increase membrane fluidity. However, PA and LPC were not capable of increasing membrane fluidity (Fig. 3B). Consistent with the results from SH-SY5Y cells, sPLA2-III was capable of increasing membrane fluidity in primary rat neurons. Together with the results for sAPPα secretion, these data suggest that sPLA2-III and AA increased sAPPα through their actions to increase membrane fluidity.

Fig. 3.

Effects of sPLA2-III, AA, PA, and LPC on neuronal cell membrane fluidity. A: Representative images of SH-SY5Y cells fluorescently labeled with FCVJ. Bar = 20 μm. B: sPLA2-III and AA increased membrane fluidity in SH-SY5Y cells, as indicated by a decreased in the fluorescent intensity of FCVJ-labeled cells. Treatments with PA and LPC did not affect membrane fluidity of cells. C, Left: Representative images of primary neurons fluorescently labeled with FCVJ. Bar = 20 μm. C, Right: sPLA2-III increased membrane fluidity in primary neurons, as indicated by a decreased in the fluorescent intensity of FCVJ-labeled cells. Data are expressed as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01).

sPLA2-III and AA increased APP at the cell surface of SH-SY5Y cells

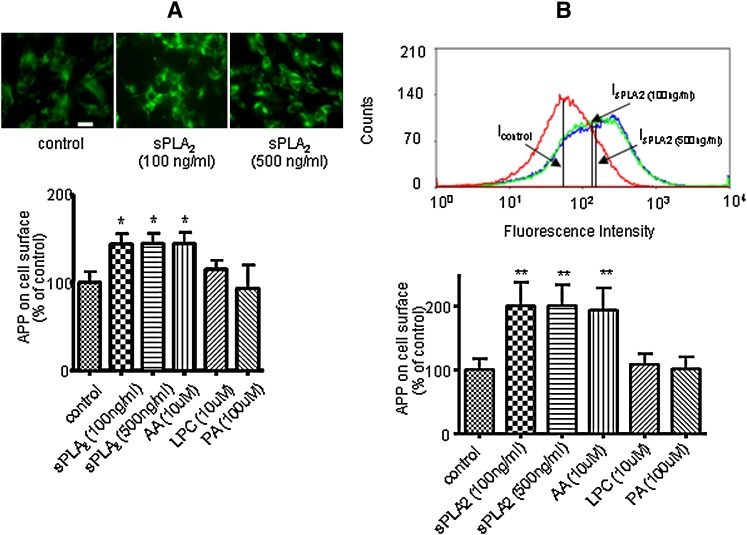

There is strong evidence suggesting that the amyloidogenic pathway to generate Aβ occurs preferentially in the intracellular compartments, whereas the non-amyloidogenic pathway for production of sAPPα preferentially occurs at the plasma membranes (22, 36–42). Based on results of our studies, it is reasonable to hypothesize that sPLA2-III and AA alter APP metabolism, resulting in an increase of APP at the cell surface of SH-SY5Y cells. To test this hypothesis, we fluorescently labeled the extracellular domain of APP without invoking the procedure for membrane permeabilization. Immunofluorescence microscopy of APP at the cell surface showed that sPLA2-III enhanced the labeling of APP at the cell surface (Fig. 4A). Quantitative measurement of the fluorescent intensity indicated that both sPLA2-III and AA increased APP at the membrane surface by ∼50%, whereas LPC and PA did not cause any significant changes compared with control (Fig. 4A). Consistent results were also obtained using the technique of fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Effects of sPLA2-III, AA, PA, and LPC on APP accumulation at the cell surface of SH-SY5Y cells. Immunofluorescence microscopy of APP at the cell surface of SH-SY5Y cells was applied. Cells treated with sPLA2-III, AA, LPC, and PA for 24 h were labeled with anti-APP antibody and FITC-conjugated secondary antibody without the cell permeabilization procedure. Representative images of fluorescently labeled SH-SY5Y cells without treatment (A, top left) and with sPLA2-III treatment (A, top, middle, and right). Bar = 20 μm. sPLA2-III and AA increased the APP accumulation at the cell surface, but LPC and PA did not (A, bottom). Representative curves of fluorescence-activated cell sorting after sPLA2-III treatment (B, top). The median values of curves were used to perform data analysis. sPLA2-III and AA increased the APP accumulation at the cell surface, but LPC and PA did not (B, bottom). Data are expressed as percentages of control and mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments (* P < 0.05).

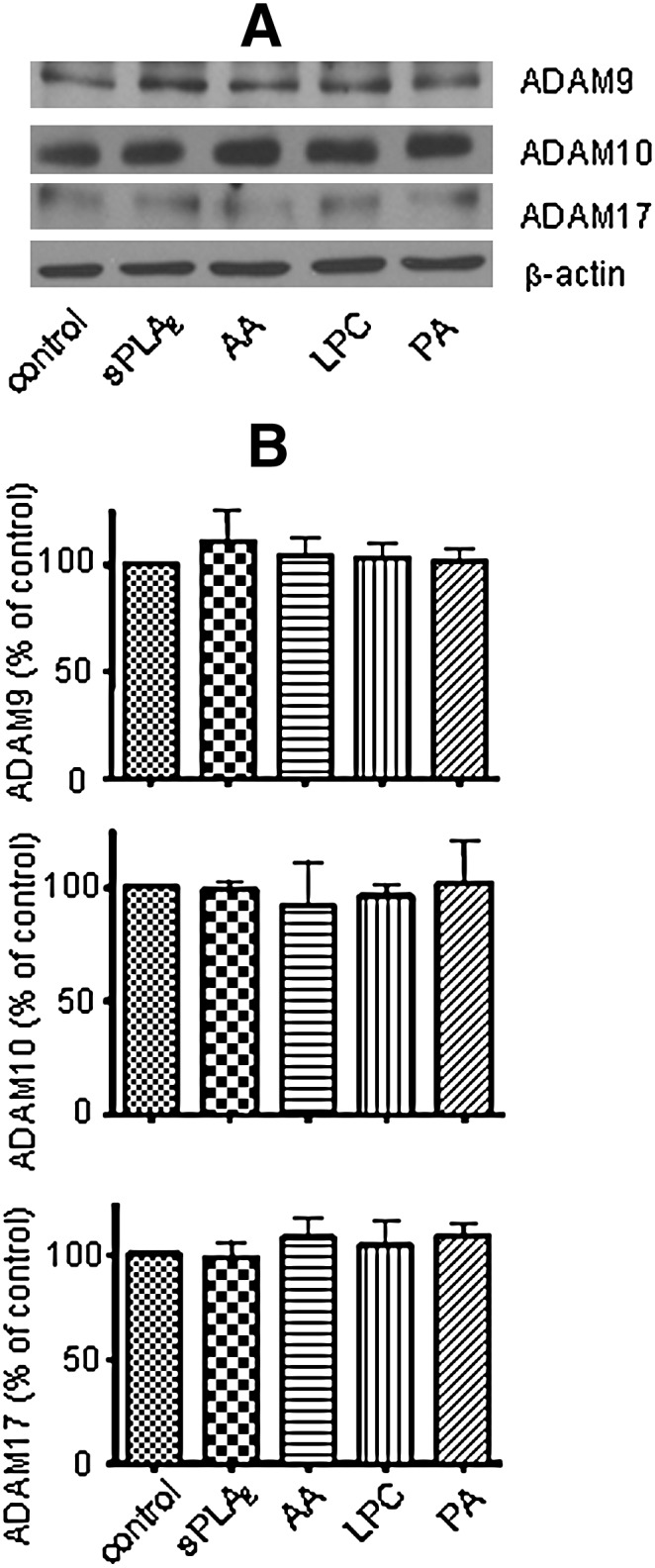

sPLA2-III, AA, PA, and LPC did not alter expressions of total α-secretases in SH-SY5Y cells

Incubation of sPLA2-III and its hydrolytic products for 24 h may change α-secretase expression for release of sAPPα. Western blot analysis showed that exposure of sPLA2-III and its hydrolytic products to SH-SY5Y cells for 24 h did not alter the expressions of different isoforms of α-secretases, including ADAM9, ADAM10, and ADAM17 (Fig. 5). These results show that APP (Fig. 2B) and α-secretases expressions were not factors in the increase in sAPPα secretion in SH-SY5Y cells induced by sPLA2-III and AA.

Fig. 5.

Effects of sPLA2-III, AA, PA, and LPC on the expressions of α-secretases in SH-SY5Y cells. Western blot analysis (A) of α-secretases shows that sPLA2-III, AA, PA, and LPC did not alter the expressions of different isoforms of α-secretases, including ADAM9 (B, top), ADAM10 (B, middle), and ADAM17 (B, bottom). Data are expressed as percentages of control and mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments.

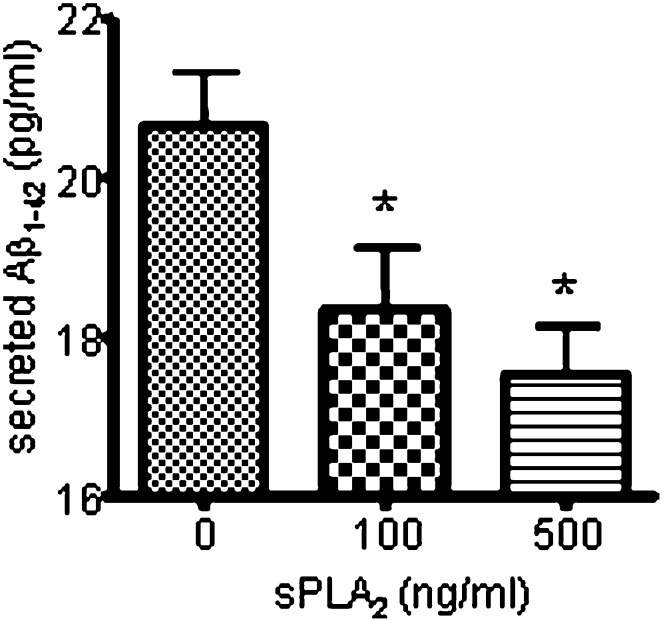

sPLA2-III decreased secretion of Aβ1-42 in SH-SY5Y cells

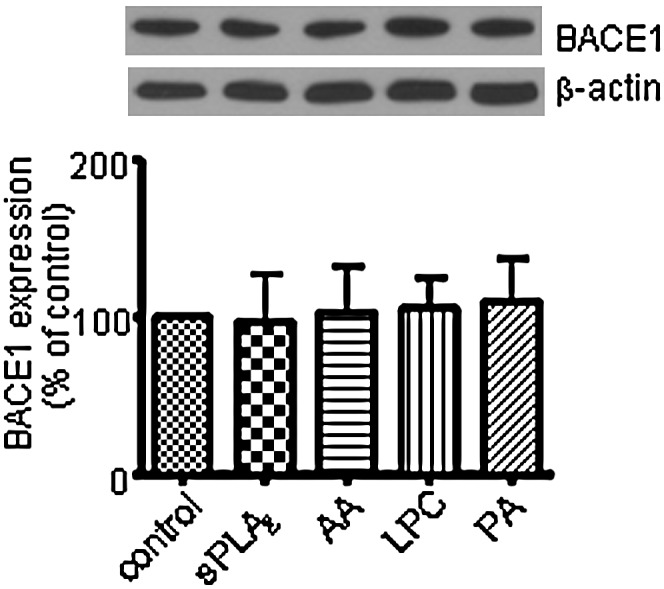

Since sPLA2-III and AA increase the secretion of sAPPα, they may decrease the secretion of Aβ1-42 in SH-SY5Y cells and primary rat neurons. Figure 6 shows that ELISA measurement of Aβ1-42 secreted from SH-SY5Y cells was decreased upon treatment of sPLA2-III for 24 h. Consistent results were obtained from primary rat neurons (data not shown). On the other hand, AA, LPC, and PA did not induce a significant change in Aβ1-42 (data not shown). The decreased in secretion of Aβ1-42 was not due to the change in BACE since sPLA2-III and its hydrolyzed products did not alter the expression of BACE1 in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

sPLA2-III decreases Aβ1-42 release from SH-SY5Y cells. Release of Aβ1-42 from SH-SY5Y cells was decreased with an increasing dose of sPLA2-III. Data are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (* P < 0.05).

Fig. 7.

Effects of sPLA2-III, AA, PA, and LPC on the expressions of BACE1 in SH-SY5Y cells. Western blot analysis shows that sPLA2-III, AA, PA, and LPC did not alter the expressions of BACE1 in SH-SY5Y cells. Data are expressed as percentages of control and mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated for the first time the ability of exogenous sPLA2-III to cause the increase in sAPPα release from differentiated SH-SY5Y cells and primary neurons. This study further unveiled a special sensitivity of low concentration of AA in mediating the non-amyloidogenic pathway of APP processing and attributed its effect to an increase in membrane fluidity but not protein synthesis.

There is strong evidence that PLA2, including the group IV cPLA2 and group IIA sPLA2, participate in the pathogenesis of AD. Previous studies demonstrated an increase in mRNA expression and immunoreactivity of cPLA2 (43–45) and sPLA2-IIA (26) in AD brains. We have also reported that both cPLA2 and calcium-independent PLA2 are key enzymes mediating Aβ-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in primary rat astrocytes (46). The role of cPLA2 in ameliorating cognitive deficits in an AD mouse model was recently demonstrated using cPLA2 deficient mice cross with APP transgenic mice (47). Most recently, sPLA2-III has been reported to express in neuronal cells such as peripheral neuronal fibers, spinal dorsal root ganglia neurons, and cerebellar Pukinje cells, and the expression of sPLA2-III in these cells has been suggested to contribute to neuronal differentiation and neuronal outgrowth (27). Human sPLA2-III comprises unique N- and C-terminal domains and a central domain, the S domain. The mature form of human sPLA2-III contains only the S domain, which is sufficient for enzymatic function (28, 48, 49). Bee venom sPLA2-III has high homology with the S domain of human sPLA2-III (28). In fact, neurotoxicity of sPLA2-III has been attributed to its binding to N-type receptors (50). In earlier studies, sPLA2-III was shown to induce cell death in primary neuronal cultures through the ability for AA to modulate N-methyl d-aspartate receptors and /or calcium channels and subsequently potentiate glutamate-induced calcium influx (51–54).

APP processing to generate Aβ is known to depend on cholesterol-enriched lipid rafts (12, 16). A model of membrane compartmentation has been suggested for APP present in two cellular pools, one associated with the cholesterol-enriched lipid rafts where Aβ is generated and another outside of rafts (i.e., non-raft domains) where α-cleavage occurs (16). Nevertheless, lowering cholesterol by treatment with statins, compounds that inhibit cholesterol synthesis pathway, was found to reduce (16, 20, 55) or enhance Aβ generation, depending on the condition of the study (56). An epidemiological study indicated that lowering cholesterol is associated with reduced risk for AD (57, 58). One possible explanation for the controversial results is that moderate reduction in cholesterol is associated with a disorganization of detergent-resistant membranes or lipid rafts and allowing more BACE to contact APP, resulting in increased Aβ generation, whereas a strong reduction of cholesterol inhibits the activities of BACE and γ-secretase, resulting in a decrease in Aβ generation (12). Consistent with the membrane compartmentation model, treatment with either methyl-β-cyclodextrin or lovastatin to reduce cellular cholesterol resulted in increase in membrane fluidity and an increase in nonamyloidogenic cleavage by α-secretase to produce sAPPα (21). Interestingly, substitution of cholesterol by the steroid 4-cholesten-3-one induces minor change in membrane fluidity and reduces sAPPα secretion, whereas substitution of cholesterol by lanosterol increases membrane fluidity and sAPPα secretion (21). These results suggest reversible effects of cholesterol on the α-secretase activity depending on membrane fluidity (21). These results also suggest that other pharmacological agents capable of altering membrane fluidity can modulate sAPPα secretion. In this study, we demonstrated that sPLA2-III and its hydrolyzed product AA increased sAPPα secretion and membrane fluidity in SH-SY5Y cells. Our data are consistent with those from others that sPLA2-III increased fluidity of hepatic membranes (59) and that AA resulted in increased fluidity of membranes in cultured human umbilical vein, cerebral endothelial cells (60, 61), and hippocampal neurons in vivo (62). Another hydrolyzed product of PLA2, docosahexaenoic acid, has also been demonstrated to increase membrane fluidity and sAPPα secretion in HEK cells and in neuronal SH-SY5Y-overexpressing APP cells (63). In addition, it has been reported that nonspecific PLA2 inhibitor partially suppressed muscarinic receptor-stimulated increase in sAPPα secretion in SH-SY5Y (64).

APP is a transmembrane protein and its internalization from the plasma membrane is regulated by key regulators of endocytosis, such as Rab5, and this process has been found to enhance APP cleavage by β-secretase leading to increased Aβ levels (65). Many studies support the notion that Aβ production occurs in endosomes (22, 38–42). APP lacking its cytoplasmic internalization motif can accumulate at the plasma membrane and undergo cleavage by α-secretase (36, 37). Alternatively, APP internalization can be reduced by lowering cholesterol, which leads to increase in membrane fluidity, APP accumulation at the cell surface, and increased sAPPα secretion (21). Increased sAPPα secretion by benzyl alcohol (C6H5OH) has also been shown to be associated with increased membrane fluidity, reduced CTF C99, and elevated CTF C83 levels, indicating enhanced α-secretase cleavage of APP, while decreased sAPPα secretion by Pluronic F68 is associated with decreased membrane fluidity, elevated CTF C99, and reduced CTF C83 levels, indicating enhanced β-secretase cleavage of APP (66). Similar to these studies, our studies show that sPLA2-III and AA increase in membrane fluidity, APP recruitment to the cell surface, and sAPPα secretion. Taken together, our data and those from Kojro et al. (21) and Peters et al. (66) support the notion that increasing membrane fluidity, in general, leads to increased APP recruitment to the cell surface and favoring process by α-secretase leading to sAPPα secretion (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of the effects of sPLA2-III, AA, PA, LPC, MβCD, benzyl alcohol (C6H5OH), and Pluronic F68 (PF68) on membrane fluidity, accumulation of APP at the cell surface, and secretion of sAPPα and Aβ

Numerous studies have been reported to provide evidence that sAPPα possesses both neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects. For example, sAPPα was shown to induce neurite outgrowth in cultured fibroblasts (67, 68), PC cells (69), human neuroblastoma cells (70), and cortical and hippocampal neurons (71–73). Neuroprotective effects of sAPPα have been shown to increase cortical synaptogenesis (74) and counteract oxidative impairment (75) and hypoglycemia-induced cytotoxicity (76). In addition to the neurotrophic and neuroprotective of sAPPα, there is evidence that α-secretase cleavage of APP competes and precludes the BACE cleavage, the primary step for production of neurotoxic Aβ (36, 37). We also found that ∼3- to 4-fold enhanced sAPPα secretion in SH-SY5Y cells induced by sPLA2-III led to a decrease in Aβ1-42 generation (Fig. 6). However, ∼2-fold enhanced sAPPα secretion induced by AA did not lead to an observable decrease in Aβ production. In fact, other in vitro studies also showed that reduced secretion of sAPPα did not result in corresponding increase in Aβ production, and decreased Aβ production did not result in corresponding increase in secretion of sAPPα (77). Certainly, more systematic studies will be required to further understand this discrepancy.

Increasing production of sAPPα has been suggested as a potential therapeutic strategy for AD treatment. In this study, we provide evidence that sPLA2-III and its hydrolyzed product, AA, increase sAPPα secretion through their effects on membrane fluidity in SH-SY5Y cells. More studies are needed to examine if sAPPα plays a role in sPLA2-III-promoted neuronal outgrowth and differentiation.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- AA

- arachidonic acid

- Aβ

- amyloid-β peptide

- AD

- Alzheimer's disease

- ADAM

- a disintegrin and metalloprotease

- APP

- amyloid precursor protein

- BACE

- β-site APP cleaving enzyme

- BCA

- bicinchoninic acid

- cPLA2

- cytosolic phospholipsae A2

- DHA

- docosahexaenoic acid

- DRM

- detergent-resistant membrane

- FACS

- fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- FCVJ

- farnesyl-(2-carboxy-2-cyanovinyl)-julolidine

- FRAP

- fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

- iPLA2

- calcium-independent phospholipsae A2

- LPC

- lysophosphatidylcholine

- MβCD

- methyl-β-cyclodextrin

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NMDA

- N-methyl D-aspartate

- PA

- palmitic acid

- PLA2

- phospholipase A2

- RA

- all-trans retinoic acid

- sAPPα

- α-secretase-cleaved soluble APP

- sPLA2-III

- secretory phospholipase A2 type III

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants 1P01 AG18357 and 1R21 NS052385. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other granting agencies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dickson D. W. 1999. Microglia in Alzheimer's disease and transgenic models. How close the fit? Am. J. Pathol. 154: 1627–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frautschy S. A., Yang F., Irrizarry M., Hyman B., Saido T. C., Hsiao K., Cole G. M. 1998. Microglial response to amyloid plaques in APPsw transgenic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 152: 307–317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGeer P. L., Itagaki S., Tago H., McGeer E. G. 1987. Reactive microglia in patients with senile dementia of the Alzheimer type are positive for the histocompatibility glycoprotein HLA-DR. Neurosci. Lett. 79: 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perlmutter L. S., Barron E., Chui H. C. 1990. Morphologic association between microglia and senile plaque amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci. Lett. 119: 32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selkoe D. J. 2000. The origins of Alzheimer disease: A is for amyloid. JAMA. 283: 1615–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stalder M., Phinney A., Probst A., Sommer B., Staufenbiel M., Jucker M. 1999. Association of microglia with amyloid plaques in brains of APP23 transgenic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 154: 1673–1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vassar R. 2004. BACE1: the beta-secretase enzyme in Alzheimer's disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 23: 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allinson T. M., Parkin E. T., Turner A. J., Hooper N. M. 2003. ADAMs family members as amyloid precursor protein alpha-secretases. J. Neurosci. Res. 74: 342–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esch F. S., Keim P. S., Beattie E. C., Blacher R. W., Culwell A. R., Oltersdorf T., McClure D., Ward P. J. 1990. Cleavage of amyloid beta peptide during constitutive processing of its precursor. Science. 248: 1122–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thornton E., Vink R., Blumbergs P. C., Van Den Heuvel C. 2006. Soluble amyloid precursor protein alpha reduces neuronal injury and improves functional outcome following diffuse traumatic brain injury in rats. Brain Res. 1094: 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng H., Vetrivel K. S., Gong P., Meckler X., Parent A., Thinakaran G. 2007. Mechanisms of disease: new therapeutic strategies for Alzheimer's disease–targeting APP processing in lipid rafts. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 3: 374–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaether C., Haass C. 2004. A lipid boundary separates APP and secretases and limits amyloid beta-peptide generation. J. Cell Biol. 167: 809–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vetrivel K. S., Cheng H., Lin W., Sakurai T., Li T., Nukina N., Wong P. C., Xu H., Thinakaran G. 2004. Association of gamma-secretase with lipid rafts in post-Golgi and endosome membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 44945–44954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cordy J. M., Hussain I., Dingwall C., Hooper N. M., Turner A. J. 2003. Exclusively targeting beta-secretase to lipid rafts by GPI-anchor addition up-regulates beta-site processing of the amyloid precursor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100: 11735–11740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marlow L., Cain M., Pappolla M. A., Sambamurti K. 2003. Beta-secretase processing of the Alzheimer's amyloid protein precursor (APP). J. Mol. Neurosci. 20: 233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ehehalt R., Keller P., Haass C., Thiele C., Simons K. 2003. Amyloidogenic processing of the Alzheimer beta-amyloid precursor protein depends on lipid rafts. J. Cell Biol. 160: 113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tun H., Marlow L., Pinnix I., Kinsey R., Sambamurti K. 2002. Lipid rafts play an important role in A beta biogenesis by regulating the beta-secretase pathway. J. Mol. Neurosci. 19: 31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reid P. C., Urano Y., Kodama T., Hamakubo T. 2007. Alzheimer's disease: cholesterol, membrane rafts, isoprenoids and statins. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 11: 383–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawamura N., Ko M., Yu W., Zou K., Hanada K., Suzuki T., Gong J. S., Yanagisawa K., Michikawa M. 2004. Modulation of amyloid precursor protein cleavage by cellular sphingolipids. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 11984–11991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simons M., Keller P., De Strooper B., Beyreuther K., Dotti C. G., Simons K. 1998. Cholesterol depletion inhibits the generation of beta-amyloid in hippocampal neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95: 6460–6464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kojro E., Gimpl G., Lammich S., Marz W., Fahrenholz F. 2001. Low cholesterol stimulates the nonamyloidogenic pathway by its effect on the alpha-secretase ADAM 10. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98: 5815–5820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Arnim C. A., von Einem B., Weber P., Wagner M., Schwanzar D., Spoelgen R., Strauss W. L., Schneckenburger H. 2008. Impact of cholesterol level upon APP and BACE proximity and APP cleavage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 370: 207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farooqui A. A., Horrocks L. A. 2006. Phospholipase A2-generated lipid mediators in the brain: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Neuroscientist. 12: 245–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun G. Y., Xu J., Jensen M. D., Simonyi A. 2004. Phospholipase A2 in the central nervous system: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J. Lipid Res. 45: 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muralikrishna Adibhatla R., Hatcher J. F. 2006. Phospholipase A2, reactive oxygen species, and lipid peroxidation in cerebral ischemia. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 40: 376–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moses G. S., Jensen M. D., Lue L. F., Walker D. G., Sun A. Y., Simonyi A., Sun G. Y. 2006. Secretory PLA2-IIA: a new inflammatory factor for Alzheimer's disease. J. Neuroinflammation. 3: 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masuda S., Yamamoto K., Hirabayashi T., Ishikawa Y., Ishii T., Kudo I., Murakami M. 2008. Human group III secreted phospholipase A2 promotes neuronal outgrowth and survival. Biochem. J. 409: 429–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valentin E., Ghomashchi F., Gelb M. H., Lazdunski M., Lambeau G. 2000. Novel human secreted phospholipase A(2) with homology to the group III bee venom enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 7492–7496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Best K. B., Ohran A. J., Hawes A. C., Hazlett T. L., Gratton E., Judd A. M., Bell J. D. 2002. Relationship between erythrocyte membrane phase properties and susceptibility to secretory phospholipase A2. Biochemistry. 41: 13982–13988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nipper M. E., Majd S., Mayer M., Lee J. C., Theodorakis E. A., Haidekker M. A. 2008. Characterization of changes in the viscosity of lipid membranes with the molecular rotor FCVJ. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1778: 1148–1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satoh T., Kosaka K., Itoh K., Kobayashi A., Yamamoto M., Shimojo Y., Kitajima C., Cui J., Kamins J., Okamoto S., et al. 2008. Carnosic acid, a catechol-type electrophilic compound, protects neurons both in vitro and in vivo through activation of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway via S-alkylation of targeted cysteines on Keap1. J. Neurochem. 104: 1116–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haidekker M. A., Ling T., Anglo M., Stevens H. Y., Frangos J. A., Theodorakis E. A. 2001. New fluorescent probes for the measurement of cell membrane viscosity. Chem. Biol. 8: 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caporaso G. L., Gandy S. E., Buxbaum J. D., Ramabhadran T. V., Greengard P. 1992. Protein phosphorylation regulates secretion of Alzheimer beta/A4 amyloid precursor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89: 3055–3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slack B. E., Nitsch R. M., Livneh E., Kunz G. M., Jr., Eldar H., Wurtman R. J. 1993. Regulation of amyloid precursor protein release by protein kinase C in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 695: 128–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Camden J. M., Schrader A. M., Camden R. E., Gonzalez F. A., Erb L., Seye C. I., Weisman G. A. 2005. P2Y2 nucleotide receptors enhance alpha-secretase-dependent amyloid precursor protein processing. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 18696–18702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haass C., Hung A. Y., Schlossmacher M. G., Teplow D. B., Selkoe D. J. 1993. beta-Amyloid peptide and a 3-kDa fragment are derived by distinct cellular mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 268: 3021–3024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koo E. H., Squazzo S. L. 1994. Evidence that production and release of amyloid beta-protein involves the endocytic pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 17386–17389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cirrito J. R., Kang J. E., Lee J., Stewart F. R., Verges D. K., Silverio L. M., Bu G., Mennerick S., Holtzman D. M. 2008. Endocytosis is required for synaptic activity-dependent release of amyloid-beta in vivo. Neuron. 58: 42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kinoshita A., Fukumoto H., Shah T., Whelan C. M., Irizarry M. C., Hyman B. T. 2003. Demonstration by FRET of BACE interaction with the amyloid precursor protein at the cell surface and in early endosomes. J. Cell Sci. 116: 3339–3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajendran L., Schneider A., Schlechtingen G., Weidlich S., Ries J., Braxmeier T., Schwille P., Schulz J. B., Schroeder C., Simons M., et al. 2008. Efficient inhibition of the Alzheimer's disease {beta}-secretase by membrane targeting. Science. 320: 520–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schobel S., Neumann S., Hertweck M., Dislich B., Kuhn P. H., Kremmer E., Seed B., Baumeister R., Haass C., Lichtenthaler S. F. 2008. A novel sorting nexin modulates endocytic trafficking and alpha-secretase cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 14257–14268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Small S. A., Gandy S. 2006. Sorting through the cell biology of Alzheimer's disease: intracellular pathways to pathogenesis. Neuron. 52: 15–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colangelo V., Schurr J., Ball M. J., Pelaez R. P., Bazan N. G., Lukiw W. J. 2002. Gene expression profiling of 12633 genes in Alzheimer hippocampal CA1: transcription and neurotrophic factor down-regulation and up-regulation of apoptotic and pro-inflammatory signaling. J. Neurosci. Res. 70: 462–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stephenson D., Rash K., Smalstig B., Roberts E., Johnstone E., Sharp J., Panetta J., Little S., Kramer R., Clemens J. 1999. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 is induced in reactive glia following different forms of neurodegeneration. Glia. 27: 110–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stephenson D. T., Lemere C. A., Selkoe D. J., Clemens J. A. 1996. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) immunoreactivity is elevated in Alzheimer's disease brain. Neurobiol. Dis. 3: 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu D., Lai Y., Shelat P. B., Hu C., Sun G. Y., Lee J. C. 2006. Phospholipases A2 mediate amyloid-beta peptide-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. J. Neurosci. 26: 11111–11119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanchez-Mejia R. O., Newman J. W., Toh S., Yu G.-Q., Zhou Y., Halabisky B., Cisse M., Scearce-Levie K., Cheng I. H., Gan L., Palop J. J., Bonventre J. V., Mucke L. 2008. Phospholipase A2 reduction ameliorates cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Neurosci. 11: 1311–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murakami M., Masuda S., Shimbara S., Bezzine S., Lazdunski M., Lambeau G., Gelb M. H., Matsukura S., Kokubu F., Adachi M., et al. 2003. Cellular arachidonate-releasing function of novel classes of secretory phospholipase A2s (groups III and XII). J. Biol. Chem. 278: 10657–10667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murakami M., Masuda S., Shimbara S., Ishikawa Y., Ishii T., Kudo I. 2005. Cellular distribution, post-translational modification, and tumorigenic potential of human group III secreted phospholipase A(2). J. Biol. Chem. 280: 24987–24998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nicolas J. P., Lin Y., Lambeau G., Ghomashchi F., Lazdunski M., Gelb M. H. 1997. Localization of structural elements of bee venom phospholipase A2 involved in N-type receptor binding and neurotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 7173–7181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DeCoster M. A. 2003. Group III secreted phospholipase A2 causes apoptosis in rat primary cortical neuronal cultures. Brain Res. 988: 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeCoster M. A., Lambeau G., Lazdunski M., Bazan N. G. 2002. Secreted phospholipase A2 potentiates glutamate-induced calcium increase and cell death in primary neuronal cultures. J. Neurosci. Res. 67: 634–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kolko M., DeCoster M. A., de Turco E. B., Bazan N. G. 1996. Synergy by secretory phospholipase A2 and glutamate on inducing cell death and sustained arachidonic acid metabolic changes in primary cortical neuronal cultures. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 32722–32728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodriguez De Turco E. B., Jackson F. R., DeCoster M. A., Kolko M., Bazan N. G. 2002. Glutamate signalling and secretory phospholipase A2 modulate the release of arachidonic acid from neuronal membranes. J. Neurosci. Res. 68: 558–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fassbender K., Simons M., Bergmann C., Stroick M., Lutjohann D., Keller P., Runz H., Kuhl S., Bertsch T., von Bergmann K., et al. 2001. Simvastatin strongly reduces levels of Alzheimer's disease beta -amyloid peptides Abeta 42 and Abeta 40 in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98: 5856–5861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abad-Rodriguez J., Ledesma M. D., Craessaerts K., Perga S., Medina M., Delacourte A., Dingwall C., De Strooper B., Dotti C. G. 2004. Neuronal membrane cholesterol loss enhances amyloid peptide generation. J. Cell Biol. 167: 953–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simons M., Schwarzler F., Lutjohann D., von Bergmann K., Beyreuther K., Dichgans J., Wormstall H., Hartmann T., Schulz J. B. 2002. Treatment with simvastatin in normocholesterolemic patients with Alzheimer's disease: a 26-week randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Ann. Neurol. 52: 346–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wolozin B., Kellman W., Ruosseau P., Celesia G. G., Siegel G. 2000. Decreased prevalence of Alzheimer disease associated with 3-hydroxy-3-methyglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Arch. Neurol. 57: 1439–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kameyama Y., Kudo S., Ohki K., Nozawa Y. 1982. Differential inhibitory effects by phospholipase A2 on guanylate and adenylate cyclases of Tetrahymena plasma membranes. Jpn. J. Exp. Med. 52: 183–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beck R., Bertolino S., Abbot S. E., Aaronson P. I., Smirnov S. V. 1998. Modulation of arachidonic acid release and membrane fluidity by albumin in vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells. Circ. Res. 83: 923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Villacara A., Spatz M., Dodson R. F., Corn C., Bembry J. 1989. Effect of arachidonic acid on cultured cerebromicrovascular endothelium: permeability, lipid peroxidation and membrane “fluidity”. Acta Neuropathol. 78: 310–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fukaya T., Gondaira T., Kashiyae Y., Kotani S., Ishikura Y., Fujikawa S., Kiso Y., Sakakibara M. 2007. Arachidonic acid preserves hippocampal neuron membrane fluidity in senescent rats. Neurobiol. Aging. 28: 1179–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kogel D., Copanaki E., Hartig U., Bottner S., Peters I., Muller W. E., Eckert G. 2008. Modulation of membrane fluidity by omega 3 fatty acids: enhanced generation of sAPPalpha is required for the neuroprotective effects of DHA. Poster presentation. The 38th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cho H. W., Kim J. H., Choi S., Kim H. J. 2006. Phospholipase A2 is involved in muscarinic receptor-mediated sAPPalpha release independently of cyclooxygenase or lypoxygenase activity in SH-SY5Y cells. Neurosci. Lett. 397: 214–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grbovic O. M., Mathews P. M., Jiang Y., Schmidt S. D., Dinakar R., Summers-Terio N. B., Ceresa B. P., Nixon R. A., Cataldo A. M. 2003. Rab5-stimulated up-regulation of the endocytic pathway increases intracellular beta-cleaved amyloid precursor protein carboxyl-terminal fragment levels and Abeta production. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 31261–31268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peters I., Igbavboa U., Schutt T., Haidari S., Hartig U., Rosello X., Bottner S., Copanaki E., Deller T., Kogel D., et al. 2009. The interaction of beta-amyloid protein with cellular membranes stimulates its own production. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1788: 964–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bhasin R., Van Nostrand W. E., Saitoh T., Donets M. A., Barnes E. A., Quitschke W. W., Goldgaber D. 1991. Expression of active secreted forms of human amyloid beta-protein precursor by recombinant baculovirus-infected insect cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 88: 10307–10311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saitoh T., Sundsmo M., Roch J. M., Kimura N., Cole G., Schubert D., Oltersdorf T., Schenk D. B. 1989. Secreted form of amyloid beta protein precursor is involved in the growth regulation of fibroblasts. Cell. 58: 615–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Milward E. A., Papadopoulos R., Fuller S. J., Moir R. D., Small D., Beyreuther K., Masters C. L. 1992. The amyloid protein precursor of Alzheimer's disease is a mediator of the effects of nerve growth factor on neurite outgrowth. Neuron. 9: 129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang R., Zhang J. Y., Yang F., Ji Z. J., Chakraborty G., Sheng S. L. 2004. A novel neurotrophic peptide: APP63–73. Neuroreport. 15: 2677–2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Araki W., Kitaguchi N., Tokushima Y., Ishii K., Aratake H., Shimohama S., Nakamura S., Kimura J. 1991. Trophic effect of beta-amyloid precursor protein on cerebral cortical neurons in culture. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 181: 265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ohsawa I., Takamura C., Kohsaka S. 1997. The amino-terminal region of amyloid precursor protein is responsible for neurite outgrowth in rat neocortical explant culture. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 236: 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Qiu W. Q., Ferreira A., Miller C., Koo E. H., Selkoe D. J. 1995. Cell-surface beta-amyloid precursor protein stimulates neurite outgrowth of hippocampal neurons in an isoform-dependent manner. J. Neurosci. 15: 2157–2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bell K. F., Zheng L., Fahrenholz F., Cuello A. C. 2008. ADAM-10 over-expression increases cortical synaptogenesis. Neurobiol. Aging. 29: 554–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mattson M. P., Guo Z. H., Geiger J. D. 1999. Secreted form of amyloid precursor protein enhances basal glucose and glutamate transport and protects against oxidative impairment of glucose and glutamate transport in synaptosomes by a cyclic GMP-mediated mechanism. J. Neurochem. 73: 532–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mattson M. P., Cheng B., Culwell A. R., Esch F. S., Lieberburg I., Rydel R. E. 1993. Evidence for excitoprotective and intraneuronal calcium-regulating roles for secreted forms of the beta- amyloid precursor protein. Neuron. 10: 243–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim M. L., Zhang B., Mills I. P., Milla M. E., Brunden K. R., Lee V. M. 2008. Effects of TNFalpha-converting enzyme inhibition on amyloid beta production and APP processing in vitro and in vivo. J. Neurosci. 28: 12052–12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]