Abstract

Urban, minority, adolescent mothers are particularly vulnerable to violence exposure, which may increase their children’s developmental risk through maternal depression and negative parenting. The current study tests a conceptual model of the effects of community and contextual violence exposure on the mental health and parenting of young, African American mothers living in Washington DC. A path analysis revealed significant direct effects of witnessed and experienced violence on mothers’ depressive symptoms and general aggression. Experiences of discrimination were also associated with increased depressive symptoms. Moreover, there were significant indirect effects of mothers’ violence exposure on disciplinary practices through depression and aggression. These findings highlight the range of violence young African American mothers are exposed to and how these experiences affect their mental health, particularly depressive symptoms, and thus disciplinary practices.

Keywords: adolescent parenting, community violence, ethnic discrimination, depression, aggression, discipline, mothers, African-American, USA

INTRODUCTION

Exposure to community violence has been consistently associated with emotional distress and antisocial behavior among urban youths (Buka, Stichich, Birdthistle, & Earls, 2001; Howard, Feigelman, Li, Cross, & Rachuba, 2002; Osofsky, 1999; Scarpa, 2003). Adolescent mothers living in low-income, urban neighborhoods are particularly vulnerable to community and interpersonal violence. These young mothers tend to be poor and disproportionately African American or Latina (Ventura, Abma, Mosher, & Henshaw, 2008), which mirrors the profiles of youth for whom violence exposure is most frequent and prevalent (Kennedy, 2006; Margolin & Gordis, 2000; Martinez & Richters, 1993; Scarpa, 2003) and of women who report the highest rates of childhood maltreatment (Browne & Bassuk, 1997; Herrenkohl, Herrenkohl, Egolf, & Russo, 1998) and/or victimization by intimate partners (Covington, Justason, & Wright, 2001; Kenney, Reinholtz, & Angelini, 1997). Indeed, a large portion of girls who become adolescent mothers are victims of physical violence at some point in their lives (Leiderman & Almo, 2001). Because of the potential for transmitting the negative sequelae of violence to their children, who are already at heightened risk for poor developmental outcomes (Borkowski et al., 2007; Coley & Chase-Lansdale, 1998; Koverola et al., 2005; Morrel, Dubowitz, Kerr, & Black, 2003; Pogarsky, Thornberry, & Lizotte, 2006; Thompson, 2007), it is particularly important to consider the psychological and behavioral consequences of violence exposure for adolescents who are also mothers.

The Problem of Violence for Urban, African American Youth

There is increasing evidence that urban, low-income, African American communities face multiple adverse circumstances including high levels of violence (Cohen et al., 1982; Sanders-Phillips, 1996). Violence victimization and perpetration is notably higher for minority youth compared to their European-American peers (Surgeon General, 2000). In a national probability sample of 4,023 adolescents age 12 to 17 years, African Americans and Latinos reported significantly higher rates of witnessing violence at each income level relative to their European American counterparts (Crouch, Hanson, Saunders, Kilpatrick, & Resnick, 2000). School violence (robberies and assaults in high schools), aggravated assaults, and the use of illegal drugs, which is associated with high rates of violence, are also higher in low-income communities of color (Bell, 1987; Freeman, Macros, & Poznanski, 1993; Noguera, 2000; Sheley, McGee, & Wright, 1992). In short, low-income adolescents of color are likely to experience violence as a consistent feature of their daily lives (Bell, 1987; Dubrow & Garbarino, 1989; Freeman et al., 1993; Lorion & Salzam, 1993; Pynoos & Eth, 1984).

There is substantial evidence suggesting that among urban, African American youth, exposure to community violence is related to increased aggressive behavior and psychological distress. Interestingly, despite the overall higher rate of community violence exposure among males, adolescent girls seem even more likely than boys to experience psychological distress (e.g., posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression) as a result of violence exposure (Buka et al., 2001; Cooley-Quille, Boyd, Frantz, & Walsh, 2001; Foster, Kupermine, & Price, 2004).

When comparing groups of high school students from a parochial school in a high-crime, inner city neighborhood, Cooley-Quille and colleagues (2001) found that adolescents who experienced relatively high violence exposure endorsed more fears, had higher trait anxiety, and reported more internalizing problems than those who experienced low violence exposure. This pattern was attributed to the difference in girls’ internalizing problems between violence-exposure groups, whereas no significant differences emerged in boys’ distress related to violence exposure. Ruchkin and colleagues (2007) examined the potential link between violence exposure and mental health in a sample of inner-city students during the transition from middle to high school. They found that post-traumatic stress symptoms mediated the association between both witnessed and directly experienced community violence and youths’ subsequent distress (e.g., depression, anxiety). Also, the association between earlier post-traumatic stress and later depression was stronger for girls than boys, for whom post-traumatic stress was more likely to predict aggression (Ruchkin et al., 2007). Contrary to these findings of gender differences in adolescents, in a study of elementary school-age children living in violent neighborhoods, Guerra and colleagues (2003) reported that, although boys’ were consistently rated higher on aggression, the associations between violence exposure, aggressive cognitions, and behavior were similar for girls and boys. Witnessing community violence contributed to stronger beliefs that aggression is normative, which in turn predicted youths’ aggressive behavior (Guerra, Huesmann, & Spindler, 2003).

Violence Exposure in Young Mothers

Despite consistent findings on the relationship between violence exposure and psychological distress in adolescent girls, little research examines these associations among adolescent mothers, an especially vulnerable group (Kennedy, 2006). There is evidence that violence exposure, particularly interpersonal violence, may be remarkably common in young pregnant women (Gazmararian et al., 1995; Gessner & Perham-Hester, 1998; Parker, McFarlane, Soeken, Torres, & Campbell, 1993). Although results are influenced by the method of assessment, between 5 and 38% of all pregnant adolescents experience interpersonal violence either during pregnancy or the year afterwards (Berenson, San Miguel, & Wilkinson, 1992; Covington, Justason, & Wright, 2001; Curry, Perrin, & Wall, 1998; Harrykissoon, Rickert, & Wiemann, 2002; McFarlane, Parker, Soeken, & Bullock, 1992; Renker, 1999). In one study of women four months postpartum, those who gave birth when younger than 18 years old were two to three times more likely to report episodes of interpersonal violence than older mothers (Gessner & Perham-Hester, 1998). Similarly, a study conducted among African American, Latino, and White mothers 12 to 18 years of age at the time of delivery revealed that one in eight had been physically assaulted by the father of her baby during the preceding year, and 40% of these also experienced violence from a family member or other relative (Wiemann, Agurcia, Berenson, Volk, & Rickert, 2000). Other studies have described samples of minority adolescent mothers in which reports of physical and/or sexual abuse histories range from 29% (Quinlivan & Evans, 2001) to 33% (Stevens-Simon & Reichert, 1994) and even 44% (Esparza & Desperat, 1996). One study, addressing the effects of cumulative “victimization experiences” among comparatively high-risk mothers of young children, found that 55.6% had experienced some form of victimization either as children/adolescents (13.8%), adults (15.5%), or both (26.3%; Dubowitz et al., 2001). From the few existing studies on violence exposure that include young mothers, it seems that their violence exposure rates are high and comparable to rates among low-income, urban youth generally (Horrowitz, Weine, & Jekel, 1995; Lipschitz, Rasmusson, Anyan, Cromwell, & Southwick, 2000).

Despite the disconcerting rates of violence exposure experienced by adolescent mothers, there are no known studies focused exclusively on the sequelae of violence within this group. Such research seems especially important given the consistent association found between violence exposure and psychological distress (Buka et al., 2001; Cooley-Quille et al., 2001; Foster et al., 2004; Guerra et al., 2003; Ruchkin et al., 2007), including depression and aggression, which have been linked to harsh parenting in adolescent mothers (Dukewich, Borkowski, & Whitman, 1996; Johnson & Flake, 2007; Marchand & Hock, 1998; Rhule, McMahon, & Spieker, 2004). The theory of intergenerational transmission of trauma purports that parents with a history of trauma “pass on” the negative emotional and behavioral sequelae either through children’s direct exposure to parental distress or through parents’ detached, harsh or even abusive behavior towards the child (Schwerdtfeger & Nelson Goff, 2007). Thus, violence exposure may have significant consequences not only for adolescent mothers, but also for their children. In light of potential implications for multiple generations, this paper aims to address gaps in the literature by empirically testing processes by which violence exposure may affect young, African American mothers’ psychological health and parenting behavior.

A Conceptual Model of Maternal Violence Exposure

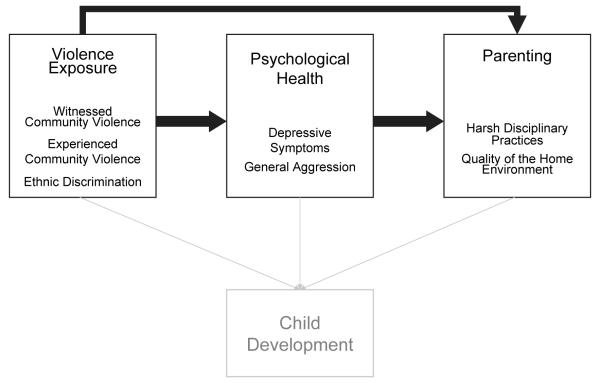

Drawing on the body of research summarized above, we developed and tested the maternal component of our conceptual model that includes direct and indirect effects of multiple levels of violence exposure on the psychological health and parenting behavior of young, African American mothers (Figure 1). Based on the theory of intergenerational transmission of trauma, we hypothesized indirect associations between young mothers’ violence exposure and their parenting behavior, explained in part by their psychological health. In particular, we expected positive associations among young mothers’ violence exposure, general aggression, symptoms of depression and harsh disciplinary practices (Morrel et al., 2003; Thompson, 2007), and negative associations with the quality of stimulation provided to their children at home (Taylor, Roberts, & Jacobson, 1997). This conceptual model includes both directly experienced and witnessed episodes of community violence, which have been shown to uniquely affect adolescent girls’ distress and aggressive behavior (Guerra et al., 2003; Howard et al., 2002).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of maternal violence exposure

An expanded conceptualization of violence exposure

Our model also incorporates an additional, and largely unexplored chronic environmental stressor – ethnic discrimination, which can be considered “contextual violence” as it occurs on many different levels (i.e., institutional, interpersonal; Jones, 2000). Racism and ethnic discrimination remain an intractable and inescapable fact of life for ethnic minorities in the U.S. (Franklin & Boyd-Franklin, 2000; Utsey, Ponterotto, & Reynolds, 2000; Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000). The study of relationships between exposure to discrimination and health is a relatively new field of investigation (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999; Krieger, 2003; Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003). Yet, as a potentially chronic, albeit low-level source of social stress, experiences of ethnic discrimination may negatively influence young, African American mothers’ psychological health (Brody et al., 2006; Simons et al., 2004; Williams et al., 2003; Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000) and parenting (Brody et al., 2008). For example, Brody and colleagues (2008) found that African American mothers’ reports of discrimination were associated with subsequent increases in depressive symptoms, which in turn predicted decreases in competence-promoting parenting. These findings lend support to the Racial Inequality and Social Integration Model (Messner & Golden, 1992; Peterson & Krivo, 1993), which asserts that community violence and ethnic discrimination contribute to minority youths’ perceptions of social inequality and, subsequently, their psychological distress (e.g., depression) and increased risk behavior (e.g., aggression).

Consistent with an ecological approach (Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993), we assert that ethnic discrimination is a distal contextual force that affects the lives of young African-American mothers and imposes another important source of violence in their daily lives (Sanders-Phillips, 2009). We do not intend to imply that a dramatic and life-threatening experience of physical violence is qualitatively or quantitatively equivalent to the daily experiences related to secondary social status. Rather, as suggested by the conceptual model above, we aim to better understand how this broader continuum of factors relevant to violence exposure influences the psychological functioning and parenting of young, African-American mothers.

In sum, our model guides the following research question: how does violence exposure, on multiple levels, directly affect young, urban, African American mothers’ psychological health and thus indirectly affect their parenting? Our investigation of this model builds on previous research by focusing on a vulnerable population of urban, minority, adolescent mothers and by considering the effects of multiple forms of violence exposure.

METHODS

We tested our conceptual model using data collected between March 2005 and August 2007 as part of a cross-sectional investigation of violence exposure among African American mothers living in Washington, DC. The mothers were adolescents when their children were born, and their children were preschool-age at the time of data collection.

Participants

Eligibility criteria for participation in the study included: mother is 18-24 years old, self-identifies as African American and non-immigrant, and has legal and physical custody of child; child is 3-5 years old and is free of serious, chronic health problems. Participants were recruited from 42 community-based programs serving a general population of mothers and children. It was necessary to screen a large number of women (n ≈ 3,850) to recruit a sample of interested (n=2,349; 61%) and eligible (n=262; 7%) mothers. The majority (97%) of eligible mothers agreed to participate, but 22 (8%) failed to attend their scheduled appointments and did not reschedule.

The final analytic sample consisted of 230 young African American mothers who provided written informed consent and completed a structured, in-person interview. Participants were, on average, 22 years old (SD = 1.50) at the time of data collection, and 13-20 years old at their child’s birth (M = 17.81, SD = 1.58). Most (69%, n=138) had at least a high school education. Approximately one third (n=86) were attending school, and 43% (n=98) were employed. The majority (61%, n=140) of young mothers lived with their own mother and/or grandmother, and 40 (17%) lived alone with their children. Most (76%, n=175) mothers were no longer romantically involved with their target child’s biological father; 19 (8%) were romantically involved but not living with the father; and 30 (13%) were cohabiting with or married to their child’s father. The largest portion of young mothers (34%, n=77) reported annual household incomes in the $0-5,000 range, and only 22% (n=49) reported annual household incomes greater than $30,000. On average, the target children of these young mothers were 50.3 months old (SD = 10.59), and approximately half (49%, n=113) were male.

Procedure

Structured interviews were scheduled at a time and place (usually the participant’s home) convenient to participants and were conducted in English by trained research assistants. Interviewers read aloud the informed consent form and interview instruments to ensure participants’ comprehension regardless of literacy. Interviews typically lasted 1.5-2 hours, and upon completion mothers were given a $50 gift certificate redeemable at a local retail store. The Institutional Review Board at Children’s National Medical Center approved all of the study procedures and measures.

Measures

Mothers completed the Survey of Exposure to Community Violence: Self Report Version which was developed in a low-income, ethnic minority sample (Richters & Martinez, 1990). Participants responded to 27 items asking how frequently they had directly experienced (e.g., hit or slapped, sexually assaulted) or witnessed (e.g., heard gunfire while in home, seen others attacked/stabbed) various types of violence on a 5-point scale from 0 (never) to 4 (many times) in their lifetimes. Subscale composite scores were created by summing responses across items, with higher scores indicating more exposure to violence. Cronbach’s alpha was .74 for experienced violence (10 items) and .86 for witnessed violence (17 items).

The General Ethnic Identity Scale (Landrine, Klonoff, Corral, Fernandez, & Roesch, 2006) was employed to measure the frequency with which participants experienced 17 specific discriminatory events (e.g., “how often have you been treated unfairly by strangers because of your race/ethnic group”, “how often have you been accused or suspected of doing something wrong because of your race/ethnic group”) and the extent to which the events were distressing. Participants responded to items about the frequency of discriminatory events using a 6-point scale from 0 (never) to 5 (almost all the time) and to items about the stressfulness of events on a 6-point Likert-scale from 1 (not at all stressful) to 6 (extremely stressful). An ethnic discrimination composite score was created by summing participants’ responses to the frequency items with higher scores indicating greater exposure to ethnic discrimination. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .87.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Inventory (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) was used to measure mothers’ symptoms of depression (e.g., ‘I could not get “going”) during the past week. This 20-item self-report version was designed to detect major or clinical depression in adolescents and adults and covers a range of depressive symptoms including interpersonal behaviors, withdrawal, and somatization. Participants reported the frequency with which they experienced each symptom on a 4-point scale from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). A total depressive symptoms score was created by summing responses across the 20 items with higher scores indicating more frequent experiences of depressive symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was .86.

The Aggression Questionnaire Short Form (AQ; Buss & Warren, 2000) was used to measure participants’ self-perceived levels of general aggression and anger and their ability to restrain themselves from committing destructive acts. The AQ Short is comprised of 15 items representing six subscales. Participants responded to items using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 5 (completely like me), and subscale composite scores were computed by summing item-responses and converting them to t-scores. Based on the authors’ norming data, which included African American participants, the AQ subscales show adequate reliability: physical aggression (e.g., ‘I may hit someone if he/she provokes me’), α = .80; verbal aggression (e.g., ‘My friends say I argue a lot’), α = .74; anger (e.g., ‘At times I get very angry for no good reason’), α = .63; hostility (e.g., ‘At times I feel I have gotten a raw deal out of life’), α =.72; indirect aggression (e.g., ‘If I’m angry enough, I may mess up someone’s work’), α = .62; and total aggression, α = .90. To reduce the number of variables in the final regression models, only scores for total aggression, which has the highest internal reliability, were included in our analyses.

The Parent Practices Interview (Webster-Stratton, 1998), adapted from the Oregon Social Learning Center Discipline Questionnaire and revised to be age-appropriate for preschoolers, was used to measure parents’ self-reported disciplinary actions and views of raising children. Mothers reported how frequently they use various parenting behaviors in response to their child’s misbehavior on a 7-point scale from 1 (never) to 7 (always), and they indicated the likelihood they would utilize various disciplinary strategies if their child were to misbehave in hypothetical ways using a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all likely) to 7 (extremely likely). Subscale scores were computed by averaging responses across items, with higher scores indicating greater use, or likelihood to use, types of discipline. For the present study we focus on harsh discipline, which has been identified as a mediator of the association between maternal violence exposure and child behavior (Morrel et al., 2003). The harsh discipline subscale consists of 14 items (e.g., ‘how often do you slap or hit your child when he/she misbehaves’, ‘how often do you show anger when you discipline your child’), and Cronbach’s alpha was .67.

The Home Observation for Measuring the Environment (HOME) Inventory (Caldwell & Bradley, 1984) was conducted by trained observers and used to measure opportunities for stimulation and support available to children in their home environments. The early childhood version of the HOME was designed for use with children 3-6 years old and is appropriate for use across racial and ethnic groups (Bradley, Corwyn, & Whiteside-Mansell, 1996). It consists of 55 binary items clustered into 8 subscales: learning materials, language stimulation, physical environment, parental responsiveness, learning stimulation, modeling of social maturity, variety in experiences, and acceptance of child. As per the instrument manual (Caldwell & Bradley, 1984), overall composite scores for home quality were computed by replacing missing item values (typically missing because child was unavailable for observation) with the subscale mean and then summing across all items. Cronbach’s alpha for the full scale score was .83.

In our analyses, we control for maternal demographic characteristics that have been linked to psychological health and parenting among adolescent mothers (Luster, 1998; Reis, 1989). Mother’s age in years was computed by subtracting the interview date from the mother’s date of birth and rounding to the nearest year. Mother’s education was measured by asking participants the highest grade or level of school they had completed with response categories ranging from 1 (never attended school) to 4 (some college or Bachelor’s degree). Participants also reported their annual household income from all sources on a 7-point ordinal scale from 1 ($5,000 or less) to 7 ($50,000 or greater).

Analytic Strategy

We examined the associative pathways between violence exposure and young African American mothers’ psychological health and parenting by conducting path analysis using MPlus 5.0 statistical software. To account for commonalities among the endogenous variables representing psychological health and parenting, correlations between depressive symptoms and aggression and between harsh discipline and home quality were estimated in the model. To explore the potential process by which violence exposure affects young mothers’ parenting, we specified all possible indirect effects in the model. Model fit was estimated with maximum likelihood estimation using the sample covariance matrix. According to generally applied heuristics (i.e., 10 cases per variable) there was sufficient statistical power to test the proposed model (Bentler & Chou, 1987; Tanaka, 1987).

RESULTS

Before conducting any multivariate analyses, the distributions of all of the independent, mediating, and dependent variables were examined. Table 1 reveals that young mothers in our study reported low direct exposure to violence (M = 4.70, SD = 4.90), and the distribution of scores was positively skewed. The most prevalent type of directly experienced violence was being slapped or hit (62%, n=143). Additionally, 27% (n=62) of mothers had been sexually assaulted, and 15 (6%) mothers had been shot at. Mothers also reported experiencing ethnic discrimination infrequently (M = 9.93, SD = 10.08), and the distribution of these scores was positively skewed. Log-transforming these variables did not affect the significance of our multivariate results, thus the reported results are based on the original, non-transformed variables for ease of interpretation. While the distribution of depressive symptom scores was also positively skewed, such a pattern is expected in a non-clinical sample, so no transformation of this variable was undertaken.

Table 1.

Variable Descriptive Statistics

| Scale Range | M(SD) | Skew | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal demographics | |||

| Age | 22.00(1.50) | −.51 | |

| Education | 1-4 | 2.97(.80) | −.06 |

| Income (household) | 1-7 | 2.91(1.89) | .71 |

| Violence exposure | |||

| Experienced | 0-40 | 4.70(4.90) | 1.37 |

| Witnessed | 0-68 | 27.89(12.54) | −.03 |

| Ethnic Discrimination | 0-85 | 9.93(10.08) | 1.31 |

| Psychological Status | |||

| Depressive Symptoms | 0-60 | 14.02(9.81) | 1.20 |

| Clinical cut-off (≥16) | 34% | ||

| Aggression | 0-100 | 53.81(9.81) | .03 |

| Clinical cut-off (≥60) | 36% | ||

| Parenting | |||

| Harsh Discipline | 1-7 | 3.07(.74) | .14 |

| HOME Quality | 0-55 | 41.57(5.68) | −.78 |

As expected, Table 2 shows significant correlations between each of the demographic control variables and parenting, particularly harsh discipline, but the direction of these associations is contrary to previous findings (Socolar, Winsor, Hunter, Catellier, & Kotch, 1999). Among this sample of young African American mothers, those who were older and more highly educated endorsed more harsh disciplinary strategies. On the other hand, observers gave higher ratings of home environment quality to mothers who were older, more highly educated, and who had higher household incomes. As anticipated, mothers’ depressive symptoms and aggression were positively correlated with harsh discipline and negatively correlated with the quality of the home environment. However, while experienced violence, witnessed violence, and ethnic discrimination were significantly associated with mothers’ psychological health, there were no significant correlations between violence exposure and parenting. Mothers who had directly experienced or witnessed more violence and perceived more ethnic discrimination reported more depressive symptoms and higher general aggression but not higher levels of harsh discipline or less stimulation in their home than young mothers who were less violence exposed. There were significant associations among all of the violence exposure variables, with stronger positive correlations between experienced and witnessed violence than between ethnic discrimination and either form of violence exposure.

Table 2.

Correlations among violence exposure, psychological status and parenting

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mother age | - | ||||||||

| 2. Mother education | .17 | - | |||||||

| 3. Household income | .05 | .34 *** | - | ||||||

| 4. Experienced violence | .01 | .05 | −.01 | - | |||||

| 5. Witnessed violence | .04 | .03 | .04 | .60 *** | - | ||||

| 6. Ethnic Discrimination | .03 | .05 | .11 | .37 *** | .34 *** | - | |||

| 7. Depression | .01 | −.14 * | −.12 | .37 *** | .28 *** | .27 *** | - | ||

| 8. Aggression | .06 | −.15 * | −.12 | .29 *** | .29 *** | .17 ** | .49 *** | - | |

| 9. Harsh Discipline | .15 * | .15 * | −.01 | .10 | .11 | .00 | .26 *** | .35 *** | - |

| 10. HOME Quality | .15 * | .19 ** | .15 * | −.01 | −.01 | .07 | −.17 ** | −.22 *** | −.23 *** |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Path Analysis

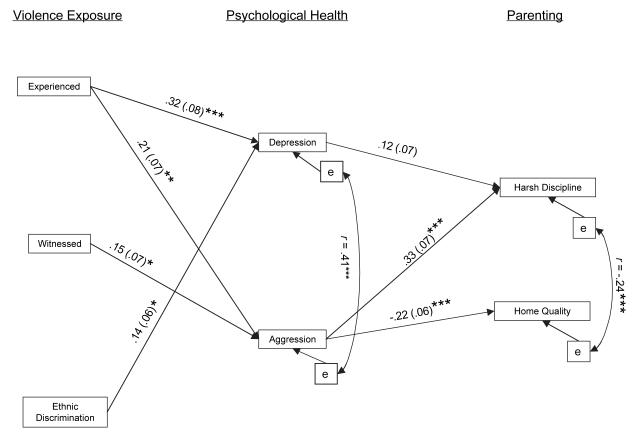

The initial model we tested was nearly saturated, therefore goodness of fit statistics reflected near perfect fit. We thus tested a trimmed model in which only the significant pathways were included (Figure 2), and fit indices for this model (χ2 = 16.98, df = 13, p = .20; RMSEA = .04; CFI = .98; TLI = .96) indicated adequate fit (Byrne, 1998). Structural R2s suggest the model explains moderate proportions of variance in young mothers’ depressive symptoms (R2 = .19, p < .001), aggression (R2 = .15, p < .001), harsh discipline (R2 = .20, p < .001) and home quality (R2 = .11, p < .01).

Figure 2.

Path analysis model of associations between violence exposure, psychological health, and parenting among young mothers. Note. Figure only displays paths for which structural coefficients are significant at p<.05.

There were significant direct paths linking experienced violence and young mothers’ depressive symptoms and aggression. Mothers who directly experienced more violence reported experiencing more depressive symptoms and higher generalized aggression. Additional significant paths between violence exposure and psychological health indicated mothers who witnessed more violence were more aggressive, and those who experienced more ethnic discrimination reported more depressive symptoms. In turn, there were significant associative pathways between psychological health and parenting. Mothers who reported more depressive symptoms used harsh disciplinary tactics more often, and mothers who rated themselves as more aggressive were both harsher and provided less stimulating home environments for their children. Although not depicted in the model for clarity’s sake, there were significant associations between mothers’ age and stimulation in the home (β = .14, SE = .06, p < .05) and between mothers’ education level and depressive symptoms (β = −.13, SE = .06, p < .05), general aggression (β = −.15, SE = .07, p < .05), and harsh discipline (β = .22, SE = .06, p < .001).

Out of the twelve indirect effects tested, three were significant, and they all involved harsh discipline. While there was no direct link between experienced violence and harsh discipline, there were significant indirect effects through both depressive symptoms (β = .05, SE = .02, p < .05) and general aggression (β = .05, SE = .03, p < .05). There was also an indirect effect of witnessed violence on harsh discipline through aggression (β = .05, SE = .03, p < .05).

DISCUSSION

In this study we found that young, African American mothers’ exposure to violence was associated with increased general aggression and depressive symptoms. Similar effects of community violence on urban adolescent girls have been consistently reported (Buka et al., 2001), and our study extends those findings to women who were adolescent mothers. On average, young African American mothers directly experienced approximately five episodes of violence and witnessed more than twenty-seven. While no direct comparisons to other groups can be made in the current study, these descriptive findings suggest that young, urban, African American mothers are exposed to concerning levels of violence, though more often as witnesses than as victims. However, these young mothers did not report many discriminatory experiences, which may be a sign of a changing social climate or possibly an artifact of the segregated nature of daily life in Washington, DC (Varady, 2005). Nonetheless, our findings indicate that even relatively few experiences of discrimination can contribute to symptoms of depression in young, African American mothers.

In support of the theory of intergenerational transmission of trauma, we found indirect associations between violence exposure and parenting through mothers’ psychological health. Young, African American mothers’ direct experiences of violence were associated with more aggression and depressive symptoms, which were in turn associated with more frequent use of harsh discipline. Furthermore, mothers who witnessed more violence tended to be more aggressive and thus harsh in their discipline. Young mothers who have been victimized may exhibit depressive symptoms because they feel unable to control their environment or mitigate the threats in it (Rutter, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2003). Also, they may be more aggressive as a proactive means of coping with their own traumatic experiences or the environmental threat they perceive based on witnessed incidents. These psychological responses to violence exposure may translate into less patience with young children and thus greater reliance on harsh disciplinary tactics (Shay & Knutson, 2008).

Although the evidence regarding effects of harsh discipline on African American children are mixed (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997), the preponderance of research suggests that the negative sequelae we found to be associated with young mothers’ violence exposure – depression, aggression, and harsh discipline – are also risk factors for child behavior problems and poor academic achievement (Black et al., 2002; Johnson & Flake, 2007; Joussemet et al., 2008). Other studies of older mothers’ violence exposure have reported significant effects on child outcomes. Morrel and colleagues (2003) found that the association between low-income, inner-city, African American mothers’ history of victimization and their reports of their preschool-aged children’s behavior problems was mediated by maternal depression and verbally aggressive disciplinary practices. Thompson (2007) also found that low-income mothers’ history of childhood victimization was linked to their 4 year-old children’s behavior problems through mothers’ psychological aggression toward their children. The current study provides preliminary evidence that African American women who were adolescent mothers are similarly affected by violence exposure in negative ways that may be transmitted to their children, and that witnessed violence may have some of the same consequences as directly experienced violence.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although our study makes important contributions to research on violence exposure among a vulnerable population, there are several limitations of this research. First, there may be noteworthy differences between the young mothers’ who self-selected into this study and those who did not participate, which influence the generalizability of these findings. However, the socio-demographic characteristics of our sample (e.g., low educational attainment, unemployment, single-parent or intergenerational households) resemble the larger population of African American adolescent mothers (Eshbaugh & Luze, 2007; Forste & Tienda, 1992). Also, the data reported here were predominantly self-report, which is subject to problems of shared variance that may have exaggerated the associations between variables, such as general aggression and harsh discipline. However, the discrete pattern of associations these variables had with violence exposure variables suggests there was adequate unique variance to validate the distinction between these two constructs.

There are also limitations of the violence exposure measure, such as the inherent issue of recall bias in retrospective measures, although follow-up questions (e.g., ‘where did this happen?’) should have increased accurate reporting. Also, a limitation common to community violence questionnaires is the comparable weight given to each violent event regardless of perpetrator (e.g., family member vs. stranger) or severity (e.g., use of lethal weapon vs. slap/hit). It may be that parenting is affected by direct exposure to more severe and traumatic violence. Furthermore, the wording of the parenting measure items may explain the unexpected positive correlations between maternal age, education and harsh discipline if younger and less educated mothers had trouble conceptualizing their disciplinary responses to the hypothetical situations proposed. There were also unforeseen problems with the observational measure of the home environment, which may explain the lack of significant results for this aspect of parenting. Because almost half of the children were not present at the interview and thus many of the warmth and acceptance items were imputed with mean-substitution (according to the HOME manual), this measure may not have accurately captured all aspects of the typical parenting behavior displayed by young mothers in our sample.

Finally, while the retrospective measure of violence exposure was intended to capture prior experience, this study was cross-sectional and thus cannot adequately address the direction of relationships between young mothers’ violence exposure, psychological health, and parenting. Future longitudinal research employing mixed methods of data collection and including child outcomes would be helpful for extending the current study of young African American mothers. Additionally, research on violence exposure within other vulnerable populations, such as Latino adolescent mothers, is needed.

Conclusion

In sum, the current study’s findings suggest that young African American mothers who are exposed to violence are more likely to suffer from increased aggression and depressive symptoms which, in turn, make them more likely to use harsh discipline with their preschool aged children. While further research is needed, these results provide preliminary evidence of intergenerational transmission of the negative sequelae of community violence exposure to children of adolescent mothers. These findings also suggest that, while ethnic discrimination may contribute to maternal depression, discriminatory experiences do not seem to influence parenting behavior, at least while children are young. Based on these results, service providers working with young mothers who may have been exposed to violence should screen for depression and increased aggression. Further, violence exposed young mothers who are in fact suffering from increased depression or aggression would be good candidates for parenting interventions that teach and support alternatives to harsh disciplinary practices.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by 5R01MH072577 from the National Institute of Mental Health awarded to Drs. Joseph, Lewin, Horn, and Sanders-Phillips. Support for this project was also received through grant M01RR020359 from the National Center for Research resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH); its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or NIH. Dr. Horn is also supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (K23 MH071374). We would like to thank Andrew Rasmussen, PhD for his thoughtful comments regarding the conceptualization of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Amy Lewin, Children’s National Medical Center.

Ivor B Horn, Children’s National Medical Center.

Dawn Valentine, Children’s National Medical Center.

Kathy Sanders-Phillips, Howard University School of Medicine.

Jill G Joseph, Children’s National Medical Center.

REFERENCES

- Bell C. Preventive strategies for dealing with violence among Blacks. Community Mental Health Journal. 1987;23:217–228. doi: 10.1007/BF00754433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Chou CP. Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research. 1987;16:78–117. [Google Scholar]

- Berenson A, San Miguel V, Wilkinson GS. Violence and its relationship to substance use in adolescent pregnancy. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1992;13:470–474. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Papas MA, Hussey JM, Dubowitz H, Kotch JB, Starr RH., Jr. Behavior problems among preschool children born to adolescent mothers: Effects of maternal depression and perceptions of partner relationships. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31(1):16–26. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3101_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkowski JG, Farris JR, Whitman TL, Carothers SS, Weed K, Keogh DA. Risk and resilience: Adolescent mothers and their children grow up. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R, Corwyn R, Whiteside-Mansell L. Life at home: Same time, different places -An examination of the HOME Inventory in different cultures. Early Development & Parenting. 1996;6:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y, Kogan SM, Murry VM, Logan P, Luo Z. Linking perceived discrimination to longitudinal changes in African American mothers’ parenting practices. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2008;70(2):319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y, Murry VM, Simons RL, Xiaojia G, Gibbons FX, et al. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne A, Bassuk SS. Intimate violence in the lives of homeless and poor housed women: Prevalence and patterns in an ethnically diverse sample. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67:261–278. doi: 10.1037/h0080230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buka SL, Stichich TL, Birdthistle I, Earls FJ. Youth exposure to violence: Prevalence, risks, and consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71:298–310. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Warren WL. Aggression Questionnaire: Manual. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell BM, Bradley RH. Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment. University of Arkansas Press; Little Rock, AK: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Lynch M. Toward an ecological/transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: Consequences for children’s development. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 1993;56:96–118. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54:805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Struening E, Muhlin G, Genevie L, Kaplan S, Peck H. Community stressors, mediating conditions and well-being in urban neighborhoods. Journal of Community Psychology. 1982;10:377–391. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(198210)10:4<377::aid-jcop2290100408>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley RL, Chase-Lansdale PL. Adolescent pregnancy and parenthood: Recent evidence and future directions. American Psychologist. 1998;53:152–166. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley-Quille M, Boyd RC, Frantz E, Walsh J. Emotional and behavioral impact of exposure to community violence in inner-city adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:199–206. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3002_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington D, Justason B, Wright L. Severity, manifestations, and consequences of violence among pregnant adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28(1):55–61. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch JL, Hanson RF, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS. Income, race/ethnicity, and exposure to violence in youth: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(6):625–641. [Google Scholar]

- Curry MA, Perrin N, Wall E. Effects of abuse on maternal complications and birth weight in adult and adolescent women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;92:530–534. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8(3):161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, Black MM, Kerr MA, Hussey JM, Morrel TM, Everson MD, et al. Type and timing of mothers’ victimization: Effects on mothers and children. Pediatrics. 2001;107(4):728–735. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubrow N, Garbarino J. Living in the war zone: Mothers and young children in a public housing development. Child Welfare. 1989;68:3–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukewich TL, Borkowski JG, Whitman TL. Adolescent mothers and child abuse potential: An evaluation of risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20(11):1031–1047. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshbaugh EM, Luze GJ. Adolescent and adult low-income mothers: How do needs and resources differ? Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;35(8):1037–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Esparza DV, Desperat MC. The effects of childhood sexual abuse on minority adolescent mothers. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecological, and Neonatal Nursing. 1996;25(4):321–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1996.tb02578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forste R, Tienda M. Race and ethnic variation in the schooling consequences of female adolescent sexual activity. Social Science Quarterly. 1992;73(1):12–30. [Google Scholar]

- Foster JD, Kupermine GP, Price AW. Gender differences in posttraumatic stress and related symptoms among inner-city minority youth exposed to community violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33(1):59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin AJ, Boyd-Franklin N. Invisibility syndrome: A clinical model of the effects of racism on African-American males. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;1:33–41. doi: 10.1037/h0087691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman LN, Macros H, Poznanski E. Violent events reported by normal urban school-aged children: Characteristics and depression correlates. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:419–423. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199303000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazmararian JA, Adams MM, Saltzman LE, Johnson CH, Bruce FC, Marks JS, et al. The relationship between pregnancy intendedness and physical violence in mothers of newborns. The PRAMS Working Group. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;85(6):1031–1038. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessner BD, Perham-Hester KA. Experience of violence among teenage mothers in Alaska. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1998;22(5):383–388. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, Huesmann R, Spindler A. Community violence exposure, social cognition, and aggression among urban elementary school children. Child Development. 2003;74(5):1561–1576. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrykissoon SD, Rickert VI, Wiemann CM. Prevalence and patterns of intimate partner violence among adolescent mothers during the postpartum period. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156(4):325–330. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl EC, Herrenkohl RC, Egolf BP, Russo MJ. The relationship between early maltreatment and teenage parenthood. Journal of Adolescence. 1998;21:291–303. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrowitz K, Weine S, Jekel J. PTSD symptoms in urban adolescent girls: Compounded community trauma. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:1353–1361. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199510000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DE, Feigelman S, Li X, Cross S, Rachuba L. The relationship among violence victimization, witnessing violence, and youth distress. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:455–462. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PL, Flake EM. Maternal depression and child outcomes. Psychiatric Annals. 2007;37(6):404–410. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-20070401-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CP. Levels of racism: A theoretical framework and a gardener’s tale. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–1215. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joussemet M, Vitaro F, Barker ED, Cote S, Nagin DS, Zoccolillo M, et al. Controlling parenting and physical aggression during elementary school. Child Development. 2008;79(2):411–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy AC. Urban adolescent mothers exposed to community, family, and partner violence: Prevalence, outcomes, and welfare policy implications. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(1):44–54. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney JW, Reinholtz C, Angelini PJ. Ethnic differences in childhood and adolescent sexual abuse and teenage pregnancy. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1997;21:3–10. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koverola C, Papas MA, Pitts S, Murtaugh C, Black MM, Dubowitz H. Longitudinal investigation of the relationship among maternal victimization, depressive symptoms, social support, and children’s behavior and development. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20(12):1523–1546. doi: 10.1177/0886260505280339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Does racism harm health? Did child abuse exist before 1962? On explicit questions, critical science, and current controversies: An ecosocial perspective. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:194–199. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA, Corral I, Fernandez S, Roesch S. Conceptualizing and measuring ethnic discrimination in health research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29(1):79–94. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiderman S, Almo C. Interpersonal violence and adolescent pregnancy: Prevalence and implications for practice and policy. Healthy Teen Network; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lipschitz DS, Rasmusson AM, Anyan W, Cromwell P, Southwick SM. Clinical and functional correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder in urban adolescent girls at a primary care clinic. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1104–1111. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200009000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorion RP, Salzam W. Children’s exposure to community violence: Following a path from concern to research to action. Psychiatry. 1993;56:55–65. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luster T. Individual differences in the caregiving behavior of teenage mothers: An ecological perspective. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;3(3):341–360. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand JF, Hock E. The relation of behavior problems in preschool children to depressive symptoms in mothers and fathers. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1998;159(3):353–366. doi: 10.1080/00221329809596157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB. The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51:445–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez P, Richters JE. The NIMH Community Violence Project: II. Children’s distress symptoms associated with violence exposure. Psychiatry. 1993;56:22–35. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K, Bullock L. Assessing for abuse during pregnancy: Severity and frequency of injuries and associated entry into prenatal care. JAMA. 1992;267:3176–3178. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.23.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messner SF, Golden RM. Racial inequality and racially disaggregated homicide rates: An assessment of alternative theoretical explanations. American Society of Criminology. 1992;30(3):421–447. [Google Scholar]

- Morrel TM, Dubowitz H, Kerr MA, Black MM. The effect of maternal victimization on children: A cross-informant study. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18(1):29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Noguera P. The public assault on America’s children: Poverty, violence, and juvenile injustice. Teachers College, Columbia University; New York: 2000. How student perspectives on violence can be used to create safer schools; pp. 130–153. [Google Scholar]

- Osofsky JD. The impact of violence on children. The Future of Children. 1999;9(3):33–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker B, McFarlane J, Soeken K, Torres S, Campbell D. Physical and emotional abuse in pregnancy: A comparison of adult and teenage women. Nursing Research. 1993;42:173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson R, Krivo L. Residential segregation and black urban homicide. Social Forces. 1993;71:1001–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Pogarsky G, Thornberry TP, Lizotte AJ. Developmental outcomes for children of young mothers. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2006;68:332–344. [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos R, Eth S. Developmental perspectives on psychic trauma in childhood. Brunner/Mazel; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlivan JA, Evans SF. A prospective cohort study of the impact of domestic violence on young teenage pregnancy outcomes. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2001;14(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/s1083-3188(00)00078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reis J. A comparison of young teenage, older teenage, and adult mothers on determinants of parenting. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied. 1989;123(2):141–151. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1989.10542970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renker PR. Physical abuse, social support, self-care, and pregnancy outcomes of older adolescents. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecological, and Neonatal Nursing. 1999;28(4):377–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1999.tb02006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhule DM, McMahon RJ, Spieker SJ. Relation of adolescent mothers’ history of antisocial behavior to child conduct problems and social competence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(3):524–535. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richters JE, Martinez P. Things I have seen and heard: An interview for children and adolescents about exposure to violence. 1990. Retrieved. from.

- Ruchkin V, Chenrich CC, Jones SM, Vermeiren R, Schwab-Stone M. Violence exposure and psychopathology in urban youth: The mediating role of posstraumatic stress. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:578–593. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Using sex differences in psychopathology to study causal mechanisms: Unifying issues and research strategies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44(8):1092–1115. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders-Phillips K. The ecology of urban violence: Its relationship to health promotion behaviors in Black and Latino communities. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1996;10:88–97. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders-Phillips K. Racial discrimination: A continuum of violence exposure for children of color. Journal of Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2009;12(2) doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A. Community violence exposure to young adults. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2003;4(3):210–227. doi: 10.1177/1524838003004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwerdtfeger KL, Nelson Goff BS. Intergenerational transmission of trauma: Exploring mother-infant prenatal attachment. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20(1):39–51. doi: 10.1002/jts.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay NL, Knutson JF. Maternal depression and trait anger as risk factors for escalated physical discipline. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13(1):39–49. doi: 10.1177/1077559507310611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheley J, McGee Z, Wright J. Gun-related violence in and around inner city schools. American Journal of Diseases of Childhood. 1992;146:677–682. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160180035012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Murry V, McLoyd V, Lin K, Cutrona C, Conger RD. Discrimination, crime, ethnic identity, and parenting as correlates of depressive symptoms among African American children: A multilevel analysis. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;14:371–393. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402002109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socolar RRS, Winsor J, Hunter WM, Catellier D, Kotch JB. Maternal disciplinary practices in an at-risk population. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153:927–934. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.9.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens-Simon C, Reichert S. Sexual abuse, adolescent pregnancy, and child abuse: A developmental approach to an intergenerational cycle. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 1994;148:23–27. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170010025005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka JS. “How big is enough?”: Sample size and goodness of fit in structural equation models with latent variables. Child Development. 1987;58:134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RD, Roberts D, Jacobson L. Stressful life events, psychological well being, and parenting in African American mothers. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:436–446. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. Mothers’ violence victimization and child behavior problems: Examining the link. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(2):306–315. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, Ponterotto JG, Reynolds AL. Racial discrimination, coping, life satisfaction, and self-esteem among African Americans. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2000;78(1):72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Varady DP. Desegregating the City: Ghettos, Enclaves, and Inequality. SUNY Press; Albany, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura SJ, Abma JC, Mosher WD, Henshaw SK. Estimated pregnancy rates by outcome for the United States, 1990–2004. National Center for Healthcare Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. Preventing conduct problems in Head Start children: Strengthening parenting competencies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(5):715–730. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiemann CM, Agurcia CA, Berenson AB, Volk RJ, Rickert VI. Pregnant adolescents: Experiences and behaviors associated with physical assault by an intimate partner. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2000;4(2):287–310. doi: 10.1023/a:1009518220331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Williams-Morris R. Racism and mental health: The African American experience. Ethnicity and Health. 2000;5:243–268. doi: 10.1080/713667453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youth Violence: A report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]