Abstract

Background

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most significant bacterial cause of community-acquired pneumonia among children under five years worldwide. Updated resistance information of S. pneumoniae among children is essential to adjust the recommendations for empirical treatment of community-acquired pneumonia, which will have immense implications for local and global health. This study investigated the prevalence of antibiotic resistance in isolated strains of S. pneumoniae and relationship with antibiotic use and demographic factors of children under five in rural Vietnam in 2007.

Methods

In Bavi district, 847 children 6 to 60 months were selected from 847 households. The main child-caregivers in the households were interviewed weekly using structured questionnaires to collect information of daily illness symptoms and drug use for the selected child over a four-week period (from March through June 2007). In the 3rd week, the children were invited for a clinical examination and to collect nasopharyngeal samples for S. pneumoniae identification. Etest and disk diffusion were used to test antibiotic susceptibility.

Results

Of 818 participating children, 258 (32%) had ongoing respiratory infections, 421 (52%) carried S. pneumoniae, and 477 (58%) had used antibiotics within the previous three weeks. Of the 421 isolates, 95% were resistant to at least one antibiotic (401/421). Resistance to co-trimoxazole, tetracycline, phenoxymethylpenicillin, erythromycin and ciprofloxacin was 78%, 75%, 75%, 70% and 28%, respectively. Low resistance was noted for amoxicillin (4%), benzylpenicillin (4%), and cefotaxime (2%). The intermediate resistance to amoxicillin was 32%. Multidrug-resistance was seen in 60%. The most common pattern was co-resistance to co-trimoxazole, tetracycline and erythromycin. The proportion of children carrying resistant bacteria was higher among the children who had used antibiotics in the previous three weeks.

Conclusions

Resistance to commonly used antibiotics and multidrug-resistance of S. pneumoniae in the area is remarkably high. High-dose amoxicillin is the only investigated oral antibiotic that can possibly be used for treatment of community-acquired pneumococcal infections. Strategies to promote appropriate prescribing and dispensing of effective antibiotics should be immediately implemented for the benefit of local and global health.

Background

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most significant bacterial cause of community-acquired pneumonia among children under five years worldwide [1]. S. pneumoniae often colonizes the nasopharynx of healthy children and can then, in specific situations, spread to the lungs, paranasal tissues and cause mucosal infections, such as pneumonia, or invade the bloodstream and cause meningitis [2]. The infections caused by this pathogen are among those least likely to be resolved without effective antibiotic treatment. However, since 1980s, a dramatic increase in antibiotic resistance among S. pneumoniae has been observed in many parts of the world [3-7]. Treatment failure associated with antibiotic-resistant pneumococci has been reported for patients with pneumonia [7,8]. High level of antibiotic use is probably the main factor driving the emergence of resistance [9].

As in many other countries, a high prevalence of S. pneumoniae resistant to common antibiotics has been seen in studies in Vietnam [10,11]. A study conducted in Bavi district in 1999 showed that 90% of 106 S. pneumoniae isolates in 200 children were resistant to at least one antibiotic, 88% to tetracycline, 32% to trimethoprim/sulphonamide and 25% to chloramphenicol [10]. Updated resistance information, especially the resistance of S. pneumoniae among children, is essential to adjust the recommendations for empirical treatment of community-acquired pneumonia, which will have immense implications for local and global health.

This study is part of a larger project conducted among the population of a rural area in northern Vietnam where data on health care providers and consumers' knowledge as well as their use of antibiotics has been obtained [12,13]. The aim of this paper is to estimate the prevalence of S. pneumoniae carriage, to assess its antibiotic susceptibility, and to investigate possible associations to antibiotic use, demographic factors of children aged 6 to 60 months and households' economic status.

Methods

Study area

The study setting was Bavi district, 60 km west of Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam. The district is divided into lowland, highland and mountains. The population is approximately 262,000 persons, of whom 8% are children under five years of age. The basic public health care system includes a district hospital with 150 beds, 3 regional polyclinics and 32 commune health stations. An Epidemiological Field Laboratory (Filabavi) was established in 1998 [14]. Baseline and re-census surveys have been done every second year. Regular follow-up of vital events is conducted every three months. The surveillance database includes 69 clusters with about 51,000 inhabitants in 12,000 households. A cluster was defined as an administrative unit, usually a village. On average, there are about 600-700 inhabitants in each cluster.

Subject and sample size

A sample of 847 children born from June 2002 to October 2006 was obtained from 847 households with at least one child eligible for the study. The sample size calculation was based on the assumption that antibiotic use in children under five in the community during one month was 70% [10], the expected drop out 30% and the design effect 2.0 due to clustering. Children older than 6 months were included to facilitate taking nasopharyngeal samples. All the households in the largest clusters in each of three geographical areas were selected to give about 280 households in each area. Some clusters were excluded due to uneven economical distribution in quintiles. In each household, one child aged 6-60 months was randomly selected (if more than one such child was present). Participants' characteristics, date of birth, sex, residential areas, parents' education, and households' assets, expenditure, and income were extracted from FilaBavi's re-census survey 2007.

Drug use survey and identification of S. pneumoniae carrier

The main child-caregivers in the households were interviewed weekly using structured questionnaires to collect information of daily illness symptoms and drug use for the selected child over a four-week period (from March through June 2007). The caregivers were also requested to fill a form regarding daily drug use for their child. When available, the drug package or prescription was examined by the interviewers. Drugs use for the participating children were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system [15], with the help of VN-pharmacy software [16]. This study includes antibiotics that are classified as antibacterials for systemic use and aggregated at the level of the active ingredient (level 5 of the ATC class J01) [15].

On the third Saturday of the survey period, the children were invited to the health commune station for a clinical examination by paediatricians from district or central hospitals. Trained microbiologists collected nasopharyngeal samples. The swabs were immediately placed in a transport tube with charcoal transport medium. Specimens were transported to Clinical Laboratories of National Institute of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Hanoi, within 12 hours after sampling.

S. pneumoniae was isolated and identified using standard laboratory procedures [2,17]. Briefly, presumptive S. pneumoniae isolates were picked based on typical colony morphology, α-hemolysis, and Gram stain morphology. Identification was confirmed by optochin sensitivity with an inhibition zone diameter of ≥ 14 mm. A single colony of each target bacterium was selected and sub-cultured for purity check and further diagnostic measures of S. pneumoniae.

Antibacterial susceptibility testing

For all isolates, minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined for benzylpenicilin and cefotaxime using Etest (AB bioMérieux, Solna, Sweden, formerly AB BIODISK). Inhibitory zone diameters were estimated for erythromycin, co-trimoxazole, tetracycline, and ciprofloxacin using disk diffusion (BIO-RAD Laboratories, Marnes-la-Coquette, France). The tested antibiotics were those commonly used in the empirical treatment of pneumonia in Vietnam or recommended for testing by the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) [18]. Susceptibility testing was done according to the performance standards of CLSI [18] and manufacturers' instructions. S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 were included as a control strain.

Interpretative non-meningitis breakpoints were based on the CLSI standards [18]. The inhibitory zone diameters for isolates to be considered resistant were: tetracycline ≤ 18 mm, co-trimoxazole ≤ 15 mm, erythromycin ≤ 15 mm. For ciprofloxacin, the criteria were: resistant ≤ 15 mm, susceptible ≥ 30 mm [19]. MICs values for cefotaxime in the Etest were: resistant ≥ 4 mg/l, susceptible ≤ 1.0 mg/l.

According to CLSI guidelines, the isolates with MICs ≤ 2.0 mg/l for benzylpenicillin were considered as susceptible at doses of at least 2 million units every four hours [18]. However, the possibility to administer the doses required by CLSI is commonly not feasible in primary health care. In order to translate in vitro resistance for benzylpenicillin to feasible treatment recommended for patients with pneumococcal pneumonia, we modified the current CLSI breakpoints using the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility testing (EUCAST) categorization as: susceptible MICs ≤ 0.5 mg/l, intermediate 1.0 mg/l≤ MICs ≤ 4.0 mg/l, resistant MICs ≥ 8.0 mg/l [18,20]. The pneumococcal infections caused by intermediate isolates may be appropriately treated with a high dose of antibiotics [18,20].

We defined the isolates as susceptible to amoxicillin and ampicillin using the same breakpoints as for benzylpenicillin [18]. Resistance to phenoxymethylpenicillin was derived from benzylpenicillin MICs > 0.06 mg/l [20]. Multidrug resistance was defined as isolates resistant to at least three of six tested antibiotics, i.e benzylpenicilin, cefotaxime, erythromycin, co-trimoxazole, tetracycline, and ciprofloxacin. Benzylpenicillin, ampicillin, amoxicillin were grouped together as a single class. We did not include phenoxylmethylpenicillin in the multidrug-resistant analysis since its susceptibility was derived from benzylpenicillin MIC.

Statistical analysis

Percentages of pathogen carriers and antibiotic-resistance of S. pneumoniae with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated to describe the nasopharyngeal carriage of bacteria among children and resistance among identified bacterium.

A wealth index defined as a combination of the information on household income, expenditure and assets was used to define the households' economic status [21]. The analysis based on this variable was initially done using quintiles. These were then dichotomized into two levels: those identified as living below average conditions and those living at average or above conditions.

Multiple regression models were used to examine the statistical associations between antibiotic resistance and the independent variables: sex (male vs. female), age (24-60 months vs. 6-23 months), household's economic-status (average or above vs. below average), region (highland, mountains vs. lowland), present ARI symptoms including any signs of respiratory infections at the time of the nasopharynx sampling (yes vs. no), and antibiotics use within the three weeks preceding the sample collection (yes vs. no).

Ethical considerations

The ethical review board of Hanoi Medical University approved this study (No 28/HMURB, 2006). Verbal consent of all parents was sought after explanation of the purpose of the study. Confidentiality was assured and participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time without any explanation. Children having a condition in need of medical treatment were treated and counselled by paediatricians from district or central hospitals.

Results

Study population and S. pneumoniae carriage

For the 847 selected children, 823 (97%) caregivers gave consent to participate in the drug use survey. Of these, 818 (99%) also consented for their child to participate in the clinical examination and collection of nasopharyngeal samples. The characteristics and current health situation of the children is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 818 community children aged 6-60 months and estimated prevalence of S. pneumoniae nasopharyngeal carriage.

| Characteristics | Absolute number with percentage in bracket | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Participating children (% among total) |

S. pneumoniae carrier (% within group) |

||

| Sex | Female | 373 (46) | 187 (50) |

| Male | 445 (54) | 234 (53) | |

| Age | 6-23 months | 367 (45) | 203 (55)* |

| 24-60 months | 451 (55) | 218 (48)* | |

| Region | Lowland | 268 (32) | 145 (54) |

| Highland | 275 (34) | 146 (53) | |

| Mountains | 275 (34) | 130 (47) | |

| Households' economic status | Under average | 358 (44) | 196 (55) |

| Average or upper | 460 (56) | 225 (49) | |

| ARI symptoms at the sampling time | No presence | 560 (68) | 265 (47)* |

| Presence | 258 (32) | 156 (61)* | |

| Other observation§ | No presence | 650 (80) | 340 (52) |

| Presence | 168 (20) | 81 (48) | |

| Previous antibiotic use within 3 weeks | No | 341 (42) | 183 (54) |

| Yes | 477 (58) | 238 (50) | |

| Total | 818 (100) | 421 (52) | |

* Significant different between groups using χ2 test (p < 0.05).

§ Other observations: Non-ARI symptoms such as digestive disorder, skin rash, toothache, phymosis.

In the clinical examination, ARI symptoms were reported in 258 children (32%). The most common symptoms were mild ARIs such as cough, sore throat, stuffy nose, or runny nose. Seven children had fever > 38°C. Only one child was diagnosed as having pneumonia. Children aged 6-23 months were more likely to present ARI symptoms than children aged 24-60 months (34% vs. 29%). There were no significant differences regarding the presence of ARI symptoms between geographical areas or households' economic conditions. Non-ARI symptoms such as digestive disorder, skin rash, toothache, phymosis were reported for 20% of the children.

Use of antibiotics during the three weeks preceding the nasopharyngeal collection was reported for 58% of the children. The average antibiotic course was 3.54 days (SD: 2.7 days), median 3.0 days indicating that 42% used antibiotics in short courses (one or two days) and a few reported a long treatment time. Penicillins with extended-spectrum (ATC code: J01CA) such as ampicillin, amoxicillin were most commonly used (49%), followed by cephalosporins (J01D) 27%, sulphonamids and trimethoprim (J01E) 11%, macrolids (J01F) 10% and other antibiotics including tetracyclines (J01A) and aminoglycosids (J01G) 3%. Most of the antibiotic courses were used when nothing more than symptoms of mild ARIs were presented. Children living in the mountainous area more often used co-trimoxazole and those in the highland area more often used amoxicillin than other areas.

S. pneumoniae was isolated from 421 (52%) of the children. Children aged 6-23 months were more likely to carry S. pneumoniae than those aged 24-60 months (Table 1). Moreover, children who had ARI symptoms were more likely to carry the bacterium. There was no significant difference in carrier prevalence related to prior use of antibiotics or household's economic condition.

S. pneumoniae antibiotic susceptibility

Table 2 shows the in-vitro activity of nine antibiotics against 421 isolates of S. pneumoniae. Ninety-five percent of isolates (401/421) were resistant to at least one of investigated antibiotics. A high level of resistance was found to co-trimoxazole, tetracycline, phenoxymethylpenicillin and erythromycin (70-78%). Low resistance was noted for benzylpenicillin (or amoxicillin and ampicillin) (4%) and cefotaxime (2%). However, the intermediate resistance to benzylpenicillin (or amoxicillin and ampicillin) was 32%. More than one-quarter of the S. pneumoniae isolates demonstrated resistance to ciprofloxacin. Only one isolate was susceptible to all antibiotics.

Table 2.

Susceptibility of 421 S. pneumoniae isolates to antibiotic agents

| Antibiotic agents | ATC code | Absolute number and percentage in bracket | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistant (R) | Intermediate (I) | Susceptible (S) | ||

| Tetracycline | J01AA07 | 314 (75) | 44 (10) | 63 (15) |

| Benzylpenicillin | J01CE01 | 17 (4) | 136 (32) | 268 (64) |

| Phenoxymethylpenicillin* | J01CE02 | 315 (75) | - | 106 (25) |

| Ampicillin** | J01CA01 | 17 (4) | 136 (32) | 268 (64) |

| Amoxicillin** | J01CA04 | 17 (4) | 136 (32) | 268 (64) |

| Cefotaxime | J01DD01 | 9 (2) | 14 (3) | 398 (95) |

| Co-trimoxazole | J01EE01 | 329 (78) | 47 (11) | 45 (11) |

| Erythromycin | J01FA01 | 294 (70) | 52 (12) | 75 (18) |

| Ciprofloxacin | J01MA02 | 119 (28) | 296 (70) | 6 (2) |

* Susceptibility to phenoxymethylpenicillin is derived from benzylpenicillin MICs according to EUCAST documents.

** Susceptibility to ampicillin and amoxicillin are derived from benzylpenicillin MICs according to CLSI documents.

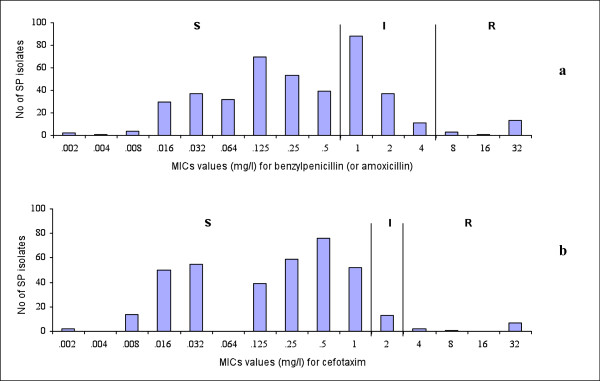

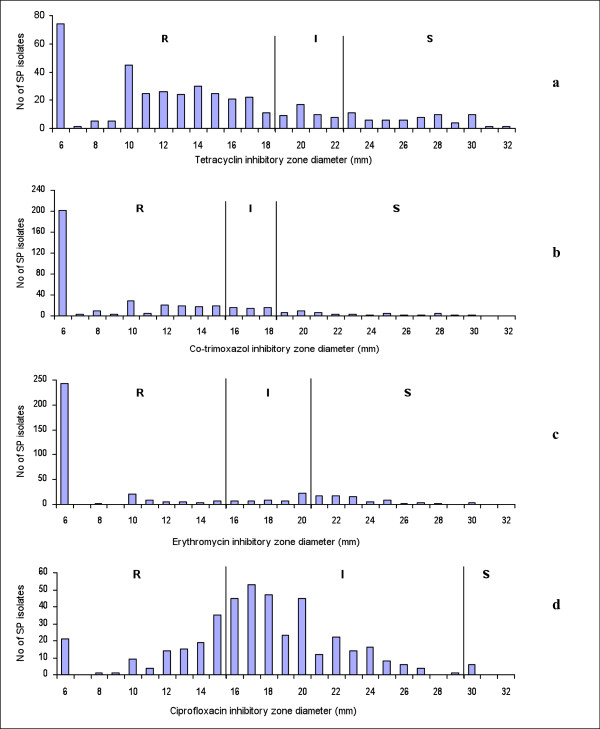

The distribution of benzylpenicillin and cefotaxime MICs in the Etest is shown in Figure 1. The MIC of benzylpenicillin at which 90% of isolates was inhibited (MIC90) was 1.5 mg/l, while cefotaxime MIC90 was 0.75 mg/l. Moreover, we found 12 and 7 isolates for which benzylpenicillin and cefotaxime MICs were higher than 32 mg/l (Figure 1.a, b). Almost all of those isolates were resistant to co-trimoxazole, tetracycline, erythromycin, and intermediate resistant to ciprofloxacin. In the disk diffusion tests, 200/421 and 250/421 strains showed no inhibitory zone (6 mm inhibitory-zone diameter) to co-trimoxazole and erythomycin, i.e. these antibiotics had no effect on most of the isolates (Figure 2.b, c).

Figure 1.

Distribution of estimated minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) by Etest. Figure 1 shows the distribution of estimated minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for penicillin (a) and cefotaxime (b) against 421 S. pneumoniae isolates.

Figure 2.

Distribution of estimated inhibitory zone diameter by disk diffusion. Figure 2 shows the distribution of estimated inhibitory zone diameter by disk diffusion for tetracycline (a), co-trimoxazole (b), erythoromycin (c) and ciprofloxacin (d) against 421 S. pneumoniae isolates.

Table 3 shows the relation between sex, age, economic status, geographic condition, previous antibiotic use and the prevalence of antibiotic resistance. Children living in the mountainous area were more likely to carry erythromycin and cotrimoxazol-resistant isolates than those in other areas. The proportion of children carrying resistant bacteria was higher among the children who had used antibiotics within the three weeks prior to the study for all antibiotics investigated. Prior treatment of co-trimoxazole gave a higher risk of cotrimoxazol resistance of the isolates.

Table 3.

Antibiotic resistance in relation to background characteristics of the 421 S. pneumoniae carriers.

| Characteristics Total number of carrier in bracket |

Percentage of resistant strains among total carriers within each category | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TET† | PEN G† (AMX, AMP) |

PEN V† | CTX† | SXT† | ERY† | CIP† | MDR† | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| - FemaleR (187) | 68* | 5 | 72 | 3 | 78 | 67 | 25 | 56 |

| - Male (234) | 80* (**) | 3 | 77 | 1 | 79 | 72 | 31 | 63 |

| Age | ||||||||

| - 6-23 monthsR (217) | 75 | 4 | 76 | 3 | 78 | 73 | 27 | 61 |

| - 24-60 months (204) | 74 | 2 | 74 | 2 | 78 | 67 | 29 | 59 |

| Region | ||||||||

| - LowlandR (145) | 77 | 2 | 78 | 0* | 74* | 68* | 32 | 55* |

| - Highland (146) | 72 | 6 | 77 | 5* | 74* | 64* | 24 | 56* |

| - Mountains (130) | 75 | 4 | 69 | 2* | 88* (**) | 78* | 29 | 70* (**) |

| Economic status | ||||||||

| - Under averageR (203) | 79 | 5 | 76 | 3 | 80 | 72 | 31 | 61 |

| - Average or upper (218) | 71 | 3 | 74 | 1 | 76 | 68 | 26 | 59 |

| Prior antibiotic use | ||||||||

| - NoR (183) | 73 | 3 | 68* | 0.5* | 73* | 67 | 26 | 56 |

| - Yes (238) | 76 | 5 | 80*(**) | 3* | 82*(**) | 72 | 30 | 63 |

| Total (421) | 75 | 4 | 75 | 2 | 78 | 70 | 28 | 60 |

* p < 0.05: significant different between groups using χ2 test.

** Significant difference between group vs. reference using multiple logistic regression analysis.

R Reference groups in multiple logistic regression analysis

† TET: tetracycline, PEN G: benzylpenicillin, AMX: amoxicillin, AMP: ampicillin, PEN V: phenoxymethylpenicillin, CTX: cefotaxime, SXT: co-trimoxazole, ERY: erythromycin, CIP: ciprofloxacin, MDR: multidrug-resistant.

Multidrug resistance among S. pneumoniae isolates

Most resistant isolates were multidrug resistant (252/401), and they accounted for 60% of all isolates. Isolates that were resistant to three classes of antibiotics were the most prevalent, 45% (190/421), then four antibiotics 14% (58/421). Co-resistance to five antibiotics was presented by 4 isolates.

Table 4 shows the pattern of co-resistance among the S. pneumoniae isolates. The most common pattern was co-resistance to co-trimoxazole, tetracycline, and erythromycin (200/252). Penicillin-resistant pneumococcal isolates are more likely to be concomitantly resistant to cefotaxime, and co-trimoxazole than to other antibiotics. Multi-resistance was not associated with sex, age, or economic status but significantly higher in children living in the mountainous area compared to other areas (Table 3).

Table 4.

Pattern of co-resistance to tested antibiotics among 421 S. pneumoniae isolates

| Individual antibiotic and combination | Absolute number of co-resistance with percentage of total 421 isolates in bracket | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP† | PEN G† | CTX† | CIP-PEN G | CIP- CTX |

PEN G-CTX | CIP- CTX - PEN G | ||

| 119 (28) | 17 (4) | 9 (2) | 1 (0.2)* | 2 (0.5) | 5 (1)* | 0 (0) | ||

| SXT† | 329 (78) | 86 (20) | 17 (4)* | 9 (2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 5 (1) | 0 (0) |

| TET† | 314 (75) | 99 (24)* | 13 (3) | 7 (2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| ERY† | 294 (70) | 66 (16)* | 15 (4) | 6 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | 0 (0) |

| SXT - TET | 254 (60)* | 73 (17) | 13 (3) | 7 (2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| SXT - ERY | 248 (59)* | 51 (12) | 15 (4) | 6 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | 0 (0) |

| TET - ERY | 241 (57)* | 60 (14) | 13 (3) | 5 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| SXT-TET-ERY | 200 (48) | 45 (11) | 13 (3) | 5 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

*Significant different between resistant groups vs. non-resistant groups using χ2 test (p < 0.05).

† TET: tetracycline, PEN G: benzylpenicillin, CTX: cefotaxime, SXT: co-trimoxazole, ERY: erythromycin, CIP: ciprofloxacin.

Discussion

This study shows that almost all of the S. pneumoniae isolates from the children were resistant to at least one of the investigated antibiotics. Most of the children had used antibiotics during the three weeks preceding the sample collection. There was a statistical association between antibiotic use and resistance. All the oral antibiotics investigated showed very low level of susceptibility except for high-dose amoxicillin that can possibly be used for treatment of pneumococcal infections.

S. pneumoniae carriage prevalence estimate was 52%, similar to the results of some other studies in Vietnam [10,11], but higher than reported elsewhere [22,23]. The carriage was lower in the older children, which is in accordance with other studies [24]. Unlike previous reports [25], however, the association between nasopharyngeal carriage of S. pneumoniae and prior antibacterial use was not present and this might be explained by the high levels of resistance discovered. A relationship between pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage to the spread of the pathogen and the development of pneumococcal diseases has been reported [26]. Implementation of conjugate vaccine could protect against pneumococcal carriage and reduce the risk of developing infection [27,28]. However, these vaccines are still expensive and may not help to reduce nasopharyngeal carriage in non-vaccine serotype carriage [27].

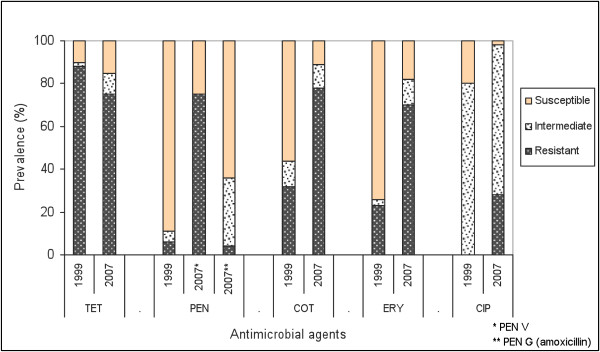

The resistance to all oral commonly used antibiotics investigated among the 421 S. pneumoniae isolates was markedly higher than previous research [3-6]. The resistance prevalences were considerable higher than those reported in 1999 in the same area, except for tetracycline (Figure 3) [10]. A significant increase of drug-resistant pneumococcal isolates from rural area was also noted in Khanh Hoa province, Vietnam [29]. One of the most serious findings is the high multidrug resistance among the isolates (60%). This was distinctively higher than reported from the Netherlands, Russia and Sweden, however still lower than several other Asian countries [30,31]. The finding is particularly worrying, as co-resistance to co-trimoxazole-tetracycline-erythromycin is the most common pattern. The high prevalence of multi-resistant pathogens shows that the practice of combining drugs in empirical treatment in the case of resistance might not be effective in this context. Nevertheless, the national IMCI guidelines recommend five days of antibiotic therapy (anyone of co-trimoxazole, oral amoxicillin, and erythromycin) for treatment of pneumonia among children 2 months up to 5 years in the community [32]. This study shows that, co-trimoxazole and erythromycin can be expected to be virtually useless in this context and the recommendation of these drugs should be seriously considered. The emergence of S. pneumoniae strains showing "very high" resistance to benzylpenicillin and cefotaxime has rarely been reported internationally [33]. To address the characteristics of such isolates requires further study. The phenomenon of high resistance to commonly used antibiotics would imply a challenge for empirical treatment of pneumococcal infections in the area.

Figure 3.

Change of estimated susceptibility prevalence of S. pneumoniae isolates between 2007 and 1999. Figure 3 compares the estimated susceptibility prevalence to five antibiotics between 421 S. pneumoniae isolates in 2007 and 106 isolates in 1999 in Bavi district.

Which factors could have led to the very high level of S. pneumoniae antibiotic resistance and multidrug-resistance in this region? One important factor is probably the frequent and irrational use of antibiotics that constitutes a constant selective pressure. In this study area, many children frequently use antibiotics [10,34]; antibiotic use was also higher among children with pneumococcal resistant strains. The higher level of co-trimoxazole and multidrug resistance in the mountainous area may mainly be due to higher use of co-trimoxazole in this area and leading to differential selective pressure in different areas. Some resistant clones of S. pneumoniae spreading with different degrees of success may also be responsible for the geographical difference of resistance [35]. The easy transmission of the pathogen between individuals could facilitate the spread of multidrug resistant strains through a small number of resistant mutants [30,36]. Previous studies found two pandemic clones Taiwan 19F and Spanish 23F to be important among pneumococcal isolates in Vietnam [3,11,28,29,37]. The global spread of the pandemic multidrug-resistant serotypes possibly partly contributes to the increase in resistance in this region [37,38]. Further, the genetic determinants for resistant clones usually exist in a stable form, so once resistance is established, it is not easily lost [36]. Although the use of tetracycline in the region recently is very low compared to three decades ago, the persistence of high resistance to this antibiotic indicates the stability of the resistant clones [34]. High resistance to ciprofloxacin among the strains of children could be due to the spread of already resistant strains from adults [3,39]. The frequent inappropriate practices of prescribers and drug sellers regarding antibiotic use for treatment of acute respiratory infections may be one explanation for the high level of antibiotic use and resistance in the area [13]. Other explanation might involve patients' misperceptions and self-medication with antibiotics [12].

What antibiotics can possibly be used for empirical treatment of pneumococcal infections considering the high levels of antibiotic resistance? Clinicians may find it safe to choose susceptible antibiotics in empirical practice. On the other hand, if the effective antibiotics are more commonly used, this will promote the emergence of even more multidrug-resistant bacteria. Cefotaxime has the highest susceptibility among the investigated antibiotics. This drug is a broad-spectrum antibiotic and if used widely and indiscriminately, resistance to this antibiotic in S. pneumoniae may become a problem in the near future [28,40]. Hence, the still effective antibiotics need to be reserved for the severe cases in tertiary hospitals and in selected cases with troublesome resistance patterns. Benzylpenicillin has a low level of resistance (4%), but this antibiotic is administrated by injections every 4-6 hours. Therefore, it is not feasible to use benzylpenicillin as the first-line for treatment. The use of narrow spectrum penicillins such as phenoxymethylpenicillin is higher among northern Europe countries where there is also generally a low rate of antibiotic resistance [9,41]. However, high resistance to phenoxymethylpenicillin in this study (75%) may lead to a poor clinical outcome if used as empirical treatment [8]. Amoxicillin is thus the only oral antibiotic that can possibly be used for treatment of pneumococcal pneumonia among children in the study area. Being low cost, easily accessible and efficacious, amoxicillin has been strongly recommended as the initial antibiotic for treatment of non-severe pneumonia especially where co-trimoxazole resistance is common [42]. According to pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic principles, the appropriate dose of amoxicillin is the one that maximizes the time when the plasma concentration persists above the MICs of the etiological agent (t > MIC) [43]. For that reason, the aim is to increase the t > MIC by increasing the number of daily doses to achieve bactericidal activity against isolates with MIC ≥ 2 mg/l [18,20,44]. To assure the therapeutic effect for at least 95% of pneumococcal infections in the context, the recommended dose of amoxicillin at 25 mg/kg × 3 times daily thus appears to be too low [32,42,44]. The guidance to increase the dose needs to be further demonstrated by clinical research.

The study has several strengths. It is a community study since the children were studied in their households and not in hospitals or clinics. The latter is a common approach but the selection process will mean that the studies only represent those seeking health care. The results are internally valid for those clusters actually investigated. The generalization of the result, the external validity, must be based on theoretical propositions suggesting that clusters or district are quite similar in respects of the phenomenon under study, the antibiotic resistance. Nothing indicates that similar rural areas should be very different. The clusters selected were the largest clusters for logistic reasons. As far as it can be investigated, nothing suggests a tendency to higher carriage or resistance in the larger clusters. The participation percentage is high. The study had been carefully piloted and field-tested. The training and supervising of the interviewers and lab workers had been conducted both in the field and in the laboratory to control the quality of collected data. By using both CLSI and EUCAST guidelines to define the interpretative breakpoints for benzylpenicillin, the resistance data is considered to be more useful for developing countries' conditions.

The major limitation of the study was that due to the limited resources, we only performed Etest for benzylpenicillin and cefotaxime. The susceptibility test for ciprofloxacin is not recommended by CLSI, but the test for S. pneumoniae is considered as an appropriate marker for monitoring fluoroquiniolone resistance [19,20,45].

Conclusions

Resistance to commonly used antibiotics and multidrug-resistance of S. pneumoniae in the investigated area are remarkably high. Of all oral antibiotics investigated, only high-dose amoxicillin can possibly be used as the first-line of choice for empirical treatment of pneumococcal infections among children in the area. The antibiotic use within the three weeks prior to the study was higher among the children with resistant pneumococci. In patients who truly warrant therapy, consideration must be given to use the most effective antibiotic class to achieve a favourable therapeutic outcome and prevent the emergence of antibiotic resistance. Strategies to promote appropriate prescribing and dispensing of effective antibiotics should be immediately implemented for the benefit of local and global health.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

NQH, NVT, ML, BE, HDP, NTKC, CSL participated in the conception and design of the study, and revising paper critically for substantial intellectual content. NQH supervised the data collection, performed data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. NVT was responsible for laboratory testing. NVT, ML, BE, NTKC, CSL supported in the data collection and helped to draft manuscript. BE, HDP contributed to statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Nguyen Quynh Hoa, Email: quynhhoa29@gmail.com.

Nguyen V Trung, Email: nvutrung@fpt.vn.

Mattias Larsson, Email: mattias.larsson@ki.se.

Bo Eriksson, Email: bo.eriksson@nhv.se.

Ho D Phuc, Email: hodang54@yahoo.com.

Nguyen TK Chuc, Email: ntkchuc020254@gmail.com.

Cecilia Stalsby Lundborg, Email: cecilia.stalsby.lundborg@ki.se.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the households from Bavi district, the field surveyors, supervisors and officials of Filabavi for their cooperation in the field. We acknowledge the staffs of the Laboratories, National Institute of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Vietnam; the pediatricians of National Children's Hospital, Bavi District Hospital; the clinical pharmacists of Hanoi University of Pharmacy; Christian G. Giske, clinical bacteriologist at Clinical Microbiology, Karolinska University Hospital for their consultation and assistance to the study. We are grateful to AB bioMérieux's Etest plant, Solna, Sweden (formerly AB BIODISK) for the Etest donation. The study was funded by a grant from Sida/SAREC, Sweden through Ministry of Science and Technology, Vietnam.

References

- Michelow IC, Olsen K, Lozano J, Rollins NK, Duffy LB, Ziegler T, Kauppila J, Leinonen M, McCracken GH Jr. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):701–707. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PR, Rosenthal KS, Pfaller MA. Medical Microbiology. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Song JH, Jung SI, Ko KS, Kim NY, Son JS, Chang HH, Ki HK, Oh WS, Suh JY, Peck KR. High prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among clinical Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in Asia (an ANSORP study) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(6):2101–2107. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.6.2101-2107.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam D. Global antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;50(Suppl):1–5. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MR, Felmingham D, Appelbaum PC, Gruneberg RN. The Alexander Project 1998-2000: susceptibility of pathogens isolated from community-acquired respiratory tract infection to commonly used antimicrobial agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52(2):229–246. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel S, Beekmann SE, Heilmann KP, Richter SS, Garcia-de-Lomas J, Ferech M, Goosens H, Doern GV. Antimicrobial use in Europe and antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26(7):485–490. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feikin DR, Schuchat A, Kolczak M, Barrett NL, Harrison LH, Lefkowitz L, McGeer A, Farley MM, Vugia DJ, Lexau C. Mortality from invasive pneumococcal pneumonia in the era of antibiotic resistance, 1995-1997. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(2):223–229. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tleyjeh IM, Tlaygeh HM, Hejal R, Montori VM, Baddour LM. The impact of penicillin resistance on short-term mortality in hospitalized adults with pneumococcal pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(6):788–797. doi: 10.1086/500140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens H, Ferech M, Stichele RV, Elseviers M. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet. 2005;365(9459):579–587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17907-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson M, Kronvall G, Chuc NT, Karlsson I, Lager F, Hanh HD, Tomson G, Falkenberg T. Antibiotic medication and bacterial resistance to antibiotics: a survey of children in a Vietnamese community. Trop Med Int Health. 2000;5(10):711–721. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry CM, Diep TS, Wain J, Hoa NT, Gainsborough M, Nga D, Davies C, Phu NH, Hien TT, White NJ. Nasal carriage in Vietnamese children of Streptococcus pneumoniae resistant to multiple antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(3):484–488. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.3.484-488.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoa NQ, Ohman A, Lundborg CS, Chuc NT. Drug use and health-seeking behavior for childhood illness in Vietnam--a qualitative study. Health Policy. 2007;82(3):320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoa NQ, Larson M, Kim Chuc NT, Eriksson B, Trung NV, Stalsby CL. Antibiotics and paediatric acute respiratory infections in rural Vietnam: health-care providers' knowledge, practical competence and reported practice. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14(5):546–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuc NT, Diwan V. FilaBavi, a demographic surveillance site, an epidemiological field laboratory in Vietnam. Scand J Public Health Suppl. 2003;62:3–7. doi: 10.1080/14034950310015031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification index with Defined Daily Doses (DDDs) 2009. Oslo: WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hanoi University of Pharmacy. VN Pharmacy, the Vietnamese software for Anatomical Therapeutical Chemical Classification System with Defined Daily Dose (ATC/DDD) Hanoi: Hanoi University of Pharmacy; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Michelow IC, Lozano J, Olsen K, Goto C, Rollins NK, Ghaffar F, Rodriguez-Cerrato V, Leinonen M, McCracken GH Jr. Diagnosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae lower respiratory infection in hospitalized children by culture, polymerase chain reaction, serological testing, and urinary antigen detection. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(1):E1–11. doi: 10.1086/324358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Nineteenth Informational Supplement. M100-S19. Vol. 29. Wayne, USA; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zone breakpoints from SRGA & SRGA-M. http://www.srga.org/

- EUCAST clinical MIC Breakpoints. http://www.srga.org/eucastwt/MICTAB/MICpenicillins.html

- Trinh OT, Nguyen ND, Dibley MJ, Phongsavan P, Bauman AE. The prevalence and correlates of physical inactivity among adults in Ho Chi Minh City. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:204. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson P, Laurell MH. Carriage of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae by children in day-care centers during an intervention program in Malmo, Sweden. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20(12):1144–1149. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200112000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Yao K, Shen X, Zhang W, Liu X, Yang Y. Serogroup distribution and antimicrobial resistance of nasopharyngeal isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae among Beijing children with upper respiratory infections (2000-2005) Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27(8):649–655. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0481-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchisio P, Esposito S, Schito GC, Marchese A, Cavagna R, Principi N. Nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in healthy children: implications for the use of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(5):479–484. doi: 10.3201/eid0805.010235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks SL, Palacio R, Ruvinsky R, Kertesz DA, Hortal M, Rossi A, Spika JS, Di Fabio JL. Risk factors and course of illness among children with invasive penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. The Streptococcus pneumoniae Working Group. Pediatrics. 1999;103(2):409–413. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.2.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques-Normark B, Blomberg C, Dagerhamn J, Battig P, Normark S. The rise and fall of bacterial clones: Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6(11):827–837. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinleyici EC, Yargic ZA. Pneumococcal conjugated vaccines: impact of PCV-7 and new achievements in the postvaccine era. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7(9):1367–1394. doi: 10.1586/14760584.7.9.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogaert D, Ha NT, Sluijter M, Lemmens N, De Groot R, Hermans PW. Molecular epidemiology of pneumococcal carriage among children with upper respiratory tract infections in Hanoi, Vietnam. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(11):3903–3908. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.11.3903-3908.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultsz C, Vien le M, Campbell JI, Chau NV, Diep TS, Hoang NV, Nga TT, Savelkoul P, Stepnieuwska K, Parry C. Changes in the nasal carriage of drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in urban and rural Vietnamese schoolchildren. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101(5):484–492. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert RR. Resistance phenotypes and multi-drug resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae (PROTEKT years 1-3 [1999-2001]) J Chemother. 2004;16(Suppl 6):35–48. doi: 10.1080/1120009x.2004.11782401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Chen Y, Black S, Hao CL, Ding YF, Zhang T, Zhao GM. Antibiotic Resistance Patterns and Serotype Distribution in Streptococcus pneumoniae from Hospitalized Pediatric Patients with Respiratory Infections in Suzhou, China. J Trop Pediatr. 2009. in press . [DOI] [PubMed]

- MOH. Handbook of integrated management for common childhood illness. Hanoi: Ministry of Health (MOH)- Vietnam; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano F, Cafini F, Aguilar L, Tarrago D, Alou L, Gimenez MJ, Gracia M, Ponte MC, Leu D, Pana M. Breakthrough in penicillin resistance? Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates with penicillin/cefotaxime MICs of 16 mg/L and their genotypic and geographical relatedness. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62(6):1234–1240. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoan LT, Chuc NT, Ottosson E, Allebeck P. Drug use among children under 5 with respiratory illness and/or diarrhoea in a rural district of Vietnam. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(6):448–453. doi: 10.1002/pds.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick AW, Whitney CG, Farley MM, Lynfield R, Harrison LH, Bennett NM, Schaffner W, Reingold A, Hadler J, Cieslak P. Geographic diversity and temporal trends of antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States. Nat Med. 2003;9(4):424–430. doi: 10.1038/nm839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenover FC. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. Am J Med. 2006;119(6 Suppl 1):S3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry CM, Duong NM, Zhou J, Mai NT, Diep TS, Thinh le Q, Wain J, Van Vinh Chau N, Griffiths D, Day NP. Emergence in Vietnam of Streptococcus pneumoniae resistant to multiple antimicrobial agents as a result of dissemination of the multiresistant Spain(23F)-1 clone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(11):3512–3517. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.11.3512-3517.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares J, Ardanuy C, Pallares R, Fenoll A. Changes in antimicrobial resistance, serotypes, and genotypes in Streptococcus pneumoniae over a thirty-year period. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010. in press . [DOI] [PubMed]

- Adam HJ, Hoban DJ, Gin AS, Zhanel GG. Association between fluoroquinolone usage and a dramatic rise in ciprofloxacin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Canada, 1997-2006. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34(1):82–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila-Corcoles A, Bejarano-Romero F, Salsench E, Ochoa-Gondar O, de Diego C, Gomez-Bertomeu F, Raga-Luria X, Cliville-Guasch X, Arija V. Drug-resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates among Spanish middle aged and older adults with community-acquired pneumonia. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens H, Ferech M, Coenen S, Stephens P. Comparison of outpatient systemic antibacterial use in 2004 in the United States and 27 European countries. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(8):1091–1095. doi: 10.1086/512810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant GB, Campbell H, Dowell SF, Graham SM, Klugman KP, Mulholland EK, Steinhoff M, Weber MW, Qazi S. Recommendations for treatment of childhood non-severe pneumonia. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(3):185–196. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70044-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg CM, McCracken GH Jr, Thomas ML, Clahsen J. Comparative pharmacokinetics of amoxicillin and ampicillin in infants and children. Pediatrics. 1979;64(5):627–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevillano D, Aguilar L, Alou L, Gimenez MJ, Gonzalez N, Echeverria O, Torrico M, Valdes L, Coronel P, Prieto J. Beta-lactam activity against penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains exhibiting higher amoxicillin versus penicillin minimum inhibitory concentration values: an in vitro pharmacodynamic simulation. Chemotherapy. 2008;54(2):84–90. doi: 10.1159/000118659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurek KN, Adam HJ, Hoban DJ, Zhanel GG. Call for the international adoption of microbiological breakpoints for fluoroquinolones and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;28(3):266–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]