Abstract

Objectives. We assessed policy and system changes and health outcomes produced by the Allies Against Asthma program, a 5-year collaborative effort by 7 community coalitions to address childhood asthma. We also explored associations between community engagement and outcomes.

Methods. We interviewed a sample of 1477 parents of children with asthma in coalition target areas and comparison areas at baseline and 1 year to assess quality-of-life and symptom changes. An extensive tracking and documentation procedure and a survey of 284 participating individuals and organizations were used to ascertain policy and system changes and community engagement levels.

Results. A total of 89 policy and system changes were achieved, ranging from changes in interinstitutional and intrainstitutional practices to statewide legislation. Allies children experienced fewer daytime (P = .008) and nighttime (P = .004) asthma symptoms than comparison children. In addition, Allies parents felt less helpless, frightened, and angry (P = .01) about their child's asthma. Type of community engagement was associated with number of policy and system changes.

Conclusions. Community coalitions can successfully achieve asthma policy and system changes and improve health outcomes. Increased core and ongoing community stakeholder participation rather than a higher overall number of participants was associated with more change.

Why coalitions? Proponents of the coalition approach to resolving health problems offer at least 3 reasons in answer to this question. One is that in a democratic society, people have the right—and indeed the obligation—to participate in the decisions and actions that affect their health and well-being.1 Another is that the greater the participation in a decision or action, the wider the acceptance of the solution among those affected and the higher the likelihood that the solution will be used and valued.2,3 The third reason is that the collective wisdom and unique experience of the participants in a coalition effort produce richer information and more relevant decisions.4

As the antecedents of health problems have become more fully understood in public health,5–7 there has been an increase in the perception that broad-based partnerships are needed to resolve them. Community coalitions, as opposed to coalitions as generally defined, function from the position that the most desirable solutions to health problems rest with the full range of community stakeholders (e.g., individuals, organizations, systems) and that there is a need for all to be represented in the process of resolution.8,9 A guiding premise of most community coalitions is that without representation that includes community residents and community-based organizations with an intimate understanding of the day-to-day aspects of the health problem, solutions will fall short of the mark.

Management of asthma, for example, is influenced by more than the actions of the asthma sufferer. The family and professionals providing clinical expertise are instrumental to asthma control. Those at work or school can provide assistance or moral support to people with asthma. Colleagues and friends need to be aware of preventive measures and need to know what to do in an emergency. Community awareness, support and action, environmental conditions, and far-reaching policies affect how an individual can manage the disease. Policies, of course, include mechanisms that make needed resources available and affordable for all stakeholders. Community coalitions have the ability to effect policy and system change in all of the circles of influence on disease prevention and management.10

ARE COMMUNITY COALITIONS EFFECTIVE?

Coalitions, community partnerships, and collaboratives are increasingly being viewed as among the most participatory means to create population-wide, macro-level changes.11 But what do we know about how effective coalitions and similar community partnerships are in achieving changes in policy and systems and improvements in health status? When answering this question with respect to community coalitions, it is necessary to separate those involving only some of the stakeholders in a health problem from those that include the community residents, organizations, and facilities most significantly affected by it.12

It is also necessary to exclude coalitions focused on providing services or programs as opposed to those focused on effecting policy and system changes. Whereas the former type of community partnership has a long history in public health practice,13–19 community collaborative efforts focused on policy and system changes20,21 have become increasingly common in recent years.22 To date however, careful assessments of their outcomes have been limited. We examined community coalitions focused on policy and system changes related to asthma management.

A review of the available literature vividly illustrates at least 1 characteristic of coalition work. There have been many more well-conducted and comprehensive studies of the processes of building and maintaining coalitions and other types of community partnerships23–31 than there have been studies of the outcomes of such work.32 In fact, outcome data are scant given the level of effort expended by these collaborations on partnership building, mobilization, and action and the prevalence of coalitions in the United States (e.g., there are more than 200 asthma coalitions in the United States alone33). We were able to locate only 11 rigorous studies documenting the health policy and system changes produced by coalition efforts or the health-related outcomes of such efforts.9,14–16,34–40

Overall, these studies have been limited in geographic scope and have not assessed outcomes over the long term. Only 4 of the studies provided empirical data describing policy and system changes.9,34–36 Seven assessed health outcomes, and 3 of these studies noted improved health status or health care use outcomes.14–16,37–40 Furthermore, available studies have evaluated either policy and system changes or health outcomes resulting from coalition efforts; no studies have evaluated both changes and outcomes. Finally, even when achievements have been laudable, these evaluations have not addressed a fundamental question: What pattern of involvement of collaborators or partners was evident when positive outcomes were achieved? We explored this important question in addition to assessing asthma-related policy, system, and health status changes.

EVALUATION OF ALLIES AGAINST ASTHMA COALITIONS

Over a 7-year period (2000 through 2007), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation supported a national program of coalition development and action—the Allies Against Asthma Program (hereafter Allies)—designed to change policies and practices regarding asthma management in low-income communities of color across the United States. The University of Michigan Center for Managing Chronic Disease served as the national program office.

Allies coalitions in 7 regions of the United States participated in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation project and undertook efforts to initiate community-wide changes designed to affect thousands of children with asthma. A participatory evaluation of both the process and outcomes of their work was undertaken by local coalition evaluators and the Center for Managing Chronic Disease. The processes characterizing Allies have been assessed elsewhere.11 According to established criteria for coalition assessment,26 these 7 partnerships have operated at a relatively high level in terms of processes, have engaged large numbers of community representatives and residents, and can be considered reasonably successful with respect to internal functioning (e.g., see Butterfoss et al.41).

We examined policy and system changes created through Allies efforts and health status outcomes evident in a sample of targeted and comparison children. The Allies evaluation addressed 3 questions: Did the coalitions generate important policy and system change outcomes? Were improved health-related outcomes also evident in the target audience, that is, low-income and minority children with asthma? What pattern of community engagement, if any, was associated with greater change?

METHODS

Procedures were carefully reviewed by the institutional review boards of the coalitions and the University of Michigan to ensure that participants would be fully informed and that consent was obtained in all instances.

Design and Data Collection

Policy and system change.

Policy and system change efforts aimed at enhancing childhood asthma management were tracked over the 5-year period from 2002 through 2006. Policy change was defined as enactment of new policies and changes in or enforcement of existing policies, whether public or organizational. System change was defined as substantial change in 1 or more elements of a system that altered their relationship to one another and the overall structure of the system. Data sources used to document changes included the online tracking system employed by coalitions to document their activities, published articles by coalition staff and conveners reporting their work,11 annual coalition reports to the national program office and the funder, key informant interviews with stakeholders (n = 97) in the coalitions' communities (conducted by a contract organization), and periodic group interviews with coalition staff, members, and leaders (n = 116).

Documented changes ranged from those related to interinstitutional and intrainstitutional policy and practice to statewide legislation. Outcomes of temporary or 1-time efforts were not included unless they were subsequently institutionalized or shown to create a change in regular practices. Once compiled, the list of policy and system changes was sent to the executive group of each coalition to verify accuracy and to indicate, via a set of definitions and a numerical scale, the degree to which each change could be attributed to the work of the coalition. Each change was assigned a score of 1 (the coalition played a peripheral role in the change), 2 (the coalition was a significant contributing partner in the change effort), or 3 (changes were led by the coalition). Changes with a score of 1 were not included in our analysis.

Health and quality-of-life outcomes.

Given that a controlled randomized trial was deemed inappropriate by some of the participating communities, a comparison group cohort design was used to assess health outcomes among families exposed to coalition activities.42 Of the 7 coalitions, 6 participated in the health outcomes study conducted in years 2 and 3 of the project (1 of the coalitions was unable to complete data collection). Each coalition recruited a convenience sample in a 2:1 ratio (to account for burden of participation) comprising families in areas of the community where coalition activities were focused (Allies group) and areas where coalition activities were limited or did not take place (comparison group).

Participants were parents or guardians of children with asthma aged zero to 17 years. Parents were interviewed at baseline, before the initiation of intensive coalition activities, and 1 year later. Participants were recruited from those attending community clinics or schools or those residing in public-assisted housing. A total of 1477 parents across the 6 communities provided information for our analyses.

The interview questionnaire, which was administered face-to-face by trained interviewers, elicited reports of children's symptoms and items related to the caregivers' quality of life. Given that time of symptom exacerbation can be an indication of degree of asthma severity and control, the questionnaire included assessment measures of daytime and nighttime symptom frequency. The items, drawn from the guidelines of the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP),43 mimicked queries of clinicians in establishing an asthma diagnosis and assessing the need for therapy. Symptoms were reported as number of days and nights with asthma symptoms over the past 14 days and over the past year (to account for seasonality). We and other authors have used these items extensively in previous studies,44–47 and they are widely employed in asthma research.

Asthma symptoms are clearly delineated in the NAEPP43 guidelines, and parameters of control representing extensive clinical experience have been developed by the NAEPP expert panel. Symptoms include wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness. Individuals experiencing symptoms on less than 4 days or nights over a 2-week period are characterized as having well-controlled asthma; individuals with symptoms on more than 14 days or nights during the same period are defined as having poorly controlled asthma; and individuals experiencing between 4 and 14 days or nights of symptoms over a 2-week period are characterized as having asthma that is not well-controlled.

Caregiver quality-of-life items were drawn from the Pediatric Asthma Caregiver Quality of Life Questionnaire.48 A total of 13 separate items assessed how the child's asthma affected various aspects of the caregiver's daily activities (the developers' recommended scoring instructions were used, that is, a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 7, with higher numbers indication higher quality of life). We have used this questionnaire previously,49,50 and it has been widely employed by researchers in the field of asthma. Items have been tested with diverse populations51–53 and have been used to measure change in many studies.51,54

Race/ethnicity.

The prevalence of asthma is higher among African American and Puerto Rican children than it is among their Caucasian counterparts, and asthma-related morbidity and mortality levels are increased in this group as well.55,56 As a means of accounting for these disparities, self-reported information about children's race/ethnicity was collected in the caregiver survey and controlled during the analyses.

Engagement of coalition members.

Coalition tracking and periodic surveys11 provided documentation of the participation of coalition members, including the number and type of organizations and individuals involved in the collaboration; examples of participants included community schools, hospitals and clinics, managed care organizations, health care providers, community-based organizations, government agencies, Medicaid, academia, and businesses. In addition, the Coalition Self-Assessment Survey was administered to coalition members from each of the 7 sites to capture quantitative data on level of participation. The survey was administered annually by site-based evaluators at a general membership meeting or by mail to participants who had attended at least 2 coalition meetings in the 12 months before the survey. A total of 284 responses from the year 2 follow-up (i.e., midproject) were available for analysis.

Data Analysis

Policy and system change.

The number of changes documented from all data sources was tallied by 3 independent reviewers and categorized into domains of change. Disagreements on the appropriateness of a given domain were discussed and agreement reached. This process was employed for each coalition and across all sites. Changes identified from the overall and site-specific observations were clustered into similar domains according to the nature of the change achieved.

Health outcomes.

Data from all coalitions were combined to provide the statistical power necessary to detect differences between Allies and comparison groups in the asthma-related outcome measures. One site had a disproportionately large sample size (n = 618) and both characteristics and sampling procedures that differed significantly at baseline from the other 5 sites, so it was excluded from our analysis and will be examined separately to ensure a more balanced picture of the findings. Therefore, in the Allies group, 541 baseline parent responses and 318 follow-up responses were available for analysis; the corresponding figures for the comparison group were 308 and 224, respectively.

The overall attrition rate was 36% (a percentage comparable to those from previous asthma studies with similar populations).57–59 At baseline, there were some differences between the intervention and comparison groups according to race/ethnicity and age group; therefore, these variables were controlled in subsequent analyses, as were gender, site, and baseline score.

Regression analyses were conducted to examine differences between the Allies and comparison groups. Each quality-of-life item prescore and postscore was treated as a separate variable. Symptoms were combined according to daytime or nighttime frequency. To determine change over time, we subtracted the baseline value from the follow-up value to create a change variable and, as noted, baseline values were controlled in the models.60 To account for loss to follow-up, we imputed values for changes in daytime and nighttime symptoms over the preceding 2 weeks and over the preceding year using multiple imputation analysis and all available information for participants with missing data (e.g., baseline value, race/ethnicity, gender, age).

The regression results observed with imputed data were highly similar to those observed with the original data (i.e., the significance and direction of the associations were unchanged).61,62 Thus, we present the results of the original analyses. SAS software63 was used in performing all of the statistical analyses.

Engagement of coalition members.

Data enabled identification of 4 patterns of stakeholder participation from 254 of the 284 individuals responding to the Coalition Self-Assessment Survey; that is, participants were characterized as core partners, ongoing partners, intermittent partners, or peripheral partners. Respondents self-reported their level of involvement on a Likert-type scale. Core partners were defined as those who had been “very involved” in coalition activities in the past year, whereas ongoing partners were defined as those who had been “fairly involved.” Both core and ongoing partners had been involved with the coalition for 1 or more years at the time of data collection. Intermittent partners had been only “a little involved” in coalition activities over the past year, and peripheral partners had been “not at all involved” in coalition activities beyond general membership meetings over the past year.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents numbers and examples of policy and system changes accomplished by the Allies coalitions in different domains over 5 years of work. In total, 89 important changes ranging from changes in interinstitutional and intrainstitutional systems and policies to statewide legislation were realized across the 7 communities. Forty-five were essentially policy changes, and 44 were system changes.

TABLE 1.

Examples and Numbers of Policy and System Changes (N = 89) Achieved by Allies Against Asthma Coalitions in 7 US Locations, 2002–2006

| Improvement Domain | No. of Changes | Examples |

| Clinical practice | 25 (11 policy and 14 systems) | Training for nurses and respiratory therapists providing asthma management education to patients was institutionalized through the creation and continued funding of an asthma coordinator position in the children's hospital (Milwaukee, WI). |

| Asthma is one of the disease focus tracks that health facilities can select from the state-supported agenda of clinical learning collaboratives (Washington State). | ||

| Coordination/standardization | 25 (10 policy and 15 systems) | Community health workers provide asthma care coordination that includes interaction with clinicians, schools, and legal aid and environmental agencies (Long Beach, CA). |

| Telephone-based community-wide care coordination system that assesses individual family needs, provides support, and refers families to clinical and community services was established (Philadelphia, PA). | ||

| Environmental conditions | 18 (10 policy and 8 systems) | City councils in 4 cities enacted ordinances banning smoking in restaurants (Hampton Roads, VA). |

| Legislation was passed that prohibits idling of diesel trucks in neighborhoods (Long Beach, CA). | ||

| Efforts to improve asthma management by families | 4 (1 policy and 3 systems) | “Asthma Days” management education was adopted and continuously offered by a larger number of community clinics/practices (Hampton Roads, VA). |

| “Awesome Asthma School Days” management education was institutionalized with support from the children's hospital (Milwaukee, WI). | ||

| Other improvements | 17 (13 policy and 4 systems) | Legislation was passed that protects a child's right to take asthma medication at school (Puerto Rico). |

| Policy was enacted that allows children with a valid action plan to carry and self-administer life-saving asthma and anaphylaxis medication in school settings (Washington, DC). |

Note. Brief descriptions of all 89 changes can be found at http://www.asthma.umich.edu or http://cmcd.sph.umich.edu/allies-against-asthma.html.

Policy and system changes clustered into categories comprising 5 domains: clinical practice, coordination and standardization, environmental conditions, institutionalization of efforts to enhance asthma management by families, and other areas. Changes were most frequent in the areas of clinical practice (n = 25) and coordination and standardization (n = 25).

Health Outcomes

Demographics.

Across the 849 participating families, the great majority of caretakers were mothers; very small numbers of grandparents and fathers were represented. Just over 60% of children were zero to 8 years of age, and 61% were male. More than 90% of children in both the Allies and comparison groups were of minority racial/ethnic backgrounds. Just under one half of the children (48%) were identified by their parent as Black or African American; 20% as Latino/Hispanic; and 22% as multiple race/ethnicity or Asian.

Symptoms.

At baseline, there were no differences between the intervention and comparison groups with respect to asthma control or symptoms after age, gender, race/ethnicity, and site had been taken into account. Slightly more than 57% of the children had well-controlled asthma at the baseline time point according to the NAEPP guidelines43; 21% of the children's asthma was not well-controlled, and about 20% had poorly controlled asthma.

Table 2 compares the adjusted baseline and follow-up symptom days and nights between the Allies and comparison groups. At follow-up, the Allies children had experienced significantly fewer daytime symptoms than did comparison children over the preceding 2 weeks (3.03 versus 3.91; P = .008). Annual differences in daytime symptoms were not evident. Nighttime symptoms over the preceding 2 weeks (2.35 versus 3.41; P = .004) and 1 year (55.17 versus 81.45; P = .003) were significantly less frequent among Allies children than among comparison children (nighttime symptoms are considered a more serious marker of asthma, and improvement in these sleep disruption–related episodes is an important measure of disease control).

TABLE 2.

Mean Numbers of Symptom Days at Baseline and Follow-Up Visits: Allies Against Asthma, 7 US Locations, 2002–2006

| Adjusted Comparison Group Meana | Adjusted Intervention Group Meana | P | |

| During the daytime in the last 14 d, how many days did the child have asthma symptoms? | |||

| Baseline | 4.35 | 4.78 | .292 |

| Follow-upb | 3.91 | 3.03 | .008 |

| During the daytime in the last 12 mo, how many days did the child have asthma symptoms? | |||

| Baseline | 70.28 | 75.08 | .629 |

| Follow-up | 73.85 | 64.98 | .077 |

| During the nighttime in the last 14 d, how many nights did the child have asthma symptoms? | |||

| Baseline | 4.67 | 4.25 | .283 |

| Follow-up | 3.41 | 2.35 | .004 |

| During the nighttime in the last 12 mo, how many nights did the child have asthma symptoms? | |||

| Baseline | 68.93 | 74.73 | .571 |

| Follow-up | 81.45 | 55.17 | .003 |

The sample size for the comparison group was n = 224; for the intervention group, n = 318.

Adjusted for race/ethnicity, gender, site, and age group.

Follow-up symptom days were also controlled for baseline value.

Among Allies children, 29% went from experiencing some symptoms at baseline, either during the day or night, to experiencing no symptoms at follow-up. In the comparison group, 19% of children became symptom free. After adjustment for race/ethnicity, age, gender, and community site, the Allies children had almost 2 times the odds of the comparison group of moving from some symptoms at baseline to none at follow-up (odds ratio [OR] = 1.9; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.17, 2.96).

Caregiver quality of life.

Table 3 shows that 3 aspects of day-to-day management of children's asthma were significantly different between Allies and comparison parents at follow-up. The Allies parents, significantly more so than the comparison group parents, felt less helpless or frightened when confronted by a symptom episode (mean score change: 0.30 versus 0.75; P = .014) and less angry about their child's asthma (mean score change: 0.16 versus 0.57; P = .011). These results suggest a greater sense of emotional control in the face of asthma management among Allies parents. Only one other item related to quality of life was significant. Allies parents exhibited a greater increase in concern than did comparison parents about medications and side effects (mean score change: 1.22 versus 0.79; P = .022). This finding probably reflects a higher awareness among these parents of the need to monitor asthma medicines.

TABLE 3.

Mean Score Changes on Quality-of-Life Items From Baseline to Follow-Up: Allies Against Asthma, 7 US Locations, 2002–2006

| Mean Score Changea | Pb | |

| How often did you feel helpless or frightened when your child experienced cough, wheeze, or breathlessness? | .014 | |

| Comparison group | 0.30 | |

| Intervention group | 0.75 | |

| How often did you feel angry that your child has asthma? | .011 | |

| Comparison group | 0.16 | |

| Intervention group | 0.57 | |

| How worried or concerned were you about your child's asthma medications and side effects? | .022 | |

| Comparison group | 1.22 | |

| Intervention group | 0.79 |

Note. The sample size for the comparison group was n = 224; for the intervention group, n = 318. Quality-of-life items were scored on a 7-point Likert scale, with higher numbers indicating better quality of life.57

Mean change in item score adjusted for site, gender, age group, race/ethnicity, and baseline value.

For difference between intervention and comparison groups.

Engagement of coalition members.

Overall participation rates across coalitions according to partner type were as follows: community-based groups (e.g., parent or advocacy groups, religious or faith-based groups, community-based organizations, youth organizations), 23%; schools or day-care centers, 7%; managed care or insurance providers, 6%; health care providers, 28%; academic institutions, 10%; businesses (including pharmaceutical companies), 6%; and other groups (e.g., local government, health departments, the media), 8%. The participation of core or ongoing partners within total partner participation categories across sites averaged 29% (range: 17% to 40%). The average participation of community-based individuals and groups as core or ongoing partners was 23% (range: 10% to 50%).

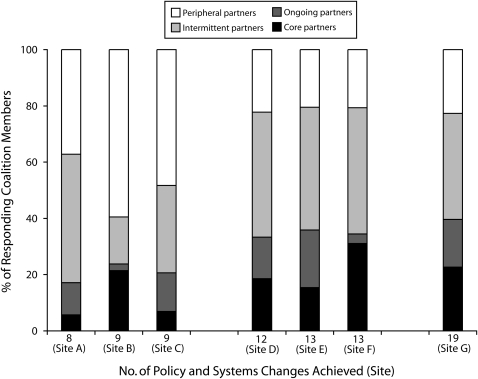

Figure 1 shows the distribution of coalition partners according to the 4 patterns of participation (peripheral, intermittent, ongoing, core) and the number of policy or system changes achieved by a coalition. The highest numbers of changes occurred in the coalitions with the most core or ongoing partners. Coalitions with more intermittent and peripheral members achieved fewer policy and system changes.

FIGURE 1.

Numbers of policy and system changes achieved (n = 254) per site, by type of partners: Allies Against Asthma, 7 US locations, 2002–2006.

When the site with the most changes and the one with the least changes were compared, several engagement differences were evident. At the site with the most changes, 40% of partners were core or ongoing partners, with 19% representing community-based individuals or organizations. At the site with the least changes, only 17% of partners were core and ongoing partners. Of these partners, 50% were community based, representing a greater proportion than that at the site with the most changes. However, the actual number of core and ongoing partners was much lower at the site with the least changes than at the site with the most changes (6 versus 21). At the site with the most changes, 60% of partners were intermittent or peripheral; at the site with the least changes, 82% of partners were intermittent or peripheral.

DISCUSSION

Our data show that coalitions can achieve important policy and system changes that have the potential to affect large numbers of residents with asthma in low-income neighborhoods of color. It may be that some of the changes observed in this study are changes that individual hospitals or health centers could have initiated alone. However, they had not initiated such change prior to the work of the Allies collaborative; the improvements observed were introduced by the Allies coalitions. The implication is that the process of collaboration, the sharing of ideas and expertise as well as access to resources and people beyond the immediate peer group, motivates and enables partners to bring about change.

The outcomes reported here reflect a process in which key stakeholders came together with the purpose of improving management and control of childhood asthma in their communities, using information and existing opportunities particular to each community. The changes achieved in the Allies Against Asthma effort were the result of meetings and exchanges of information among diverse individuals and organizational representatives who often do not work together to solve health problems. Through these interactions, possible solutions were discussed and agreements were made for implementing changes. Changes made in systems and policies were not predetermined but based on analyses of need and assessments of possibilities. Coalition efforts were also associated with positive changes in health-related outcomes for the targeted population, in this case fewer symptoms among children with asthma and a greater sense of control in managing the disease on the part of their parents.

The policy and system changes realized by the Allies sites hold great promise for asthma control. Policy recommendations made by asthma experts63–67 have included the types of changes achieved by Allies coalitions as priorities at the national level as well as local levels. Furthermore, our findings indicate that coalition efforts were successful in reaching the low-income minority children targeted as those most in need of assistance in controlling their health condition.

Our study also enabled a close look at community engagement. The data suggest that the greater the proportion of core and ongoing partners, the greater the extent of change achieved by a coalition. It may be that attempting to maintain connections with large numbers of partners whose involvement is intermittent and marginal distracts a coalition's attention to its task and dilutes its resources. A strong core of continuous collaborators may have helped to focus efforts and optimize shared resources. The Allies coalitions drew representatives from across all types of community stakeholders, and achieving the ongoing participation of diverse groups appeared to be related to success. An important observation was that community-based organizations and individuals were a visible component of successful partnerships, accounting for just under one quarter of the core and ongoing members at the most successful site.

These patterns of participation and their relationship to outcomes are important considerations for public health practitioners, community groups, and researchers. It is not uncommon, even as evident at some Allies sites, for community collaborations to focus on the quantity of partners. Recruiting a large number of organizations into a community collaboration requires considerable time, money, and energy. The Allies participation patterns suggest that it is not the number of partners that produces results; rather, it is a preponderance of committed organizations that are persistently and strategically engaged. Collaboration with a strong, ongoing core of partners will generate better outcomes than would a large collaboration of peripheral and intermittent partners.

Limitations

A number of methodological aspects of the Allies evaluation deserve consideration. Controlled and randomized evaluation designs are often deemed unacceptable or unrealistic for assessing community-related change, and, as noted, this was the view of the Allies communities. It is generally accepted that when convenience samples and comparison groups are used, alternative explanations for evaluative findings cannot be excluded. For example, political climate can have a significant effect on policy and system change efforts, and such factors were not incorporated into our analysis. Nonetheless, the consistency of our findings across the diverse Allies communities increases our confidence in these results.

Given the wide range of policies and system changes addressed across the sites over a 5-year period and the timing of the introduction of change, it is not possible to connect a given policy or system improvement or a combination of improvements to the health outcomes documented. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that improvements seen in children's symptom status were simply coincident with change efforts undertaken in the participating communities. Coalitions instituted change, and the health status of children with asthma improved. A connection, though unproven, is evident. Our results might have been even stronger had the health outcomes survey been conducted much later after policy and system changes had more time to take hold.

Finally, the relationship between engagement of coalition members and policy and system change is not definitive. There is no gold standard for measuring engagement of members in a coalition or collaborative, nor is there a widely agreed upon means to measure the effects of such engagement. However, the evidence generated in this study indicates that it is depth of participation that is important. Success was related not to the overall number of organizations and individuals participating in change efforts but, rather, to the continuous and active involvement of a core group of diverse partners.

Conclusions

The work of Allies Against Asthma contributes significantly to the small but growing body of evidence indicating that targeting policy and system changes and focusing on specific health indicators through collaborative community-wide work can bring about needed change. The Allies coalitions were especially resourceful in establishing policies related to improved clinical practices and system coordination and standardization. The single-minded attention to children with a particular health condition resulted in significant symptom improvements.

Coalitions are no more a magic solution than any other form of intervention. They cannot achieve all ends for all types of health problems. However, they appear to achieve change remarkably well while meeting the goals of democratic decision making and reflecting the real-life experiences of people confronting a health problem such as asthma. There is a need for further careful evaluations of coalition work, wherever it occurs around the country and whatever the health focus, to more fully address questions regarding this form of public health intervention. Assessing results with the rigor warranted requires carefully conducted outcome research. The importance of collaborative efforts to public health principles and the limited body of extant evidence on outcomes makes such research a priority.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by multiple grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and additional support was provided by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation.

We gratefully acknowledge the guidance and contributions of Michele Carrick, Elaine Cassidy, Mary desVignes-Kendrick, Susan Downey, Rob Fulwood, Rachel A. Gonzales-Hanson, J. A. Grisso, Sarah Hearn, Barbara Israel, Talmadge King, Floyd Malveaux, Robert Mellins, Steve Page, Guy Parcel, Stephen Redd, Jeanne Taylor, Abe Wandersman, Sandra Wilson, and Albert Yee. We also thank the dedicated members of all of the Allies Against Asthma coalitions.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the University of Michigan Health Sciences institutional review board. Written informed consent was obtained by the sites prior to conducting the interviews.

References

- 1.International Conference on Primary Health Care Declaration of Alma-Ata. WHO Chron 1978;32(11):428–430 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMillan B, Florin P, Stevenson J, Kerman B, Mitchell RE. Empowerment praxis in community coalitions. Am J Community Psychol 1995;23(5):699–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Ansari W, Phillips CJ, Zwi AB. Public health nurses' perspectives on collaborative partnerships in South Africa. Public Health Nurs 2004;21(3):277–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cashman SB, Adeky S, Allen AJ, et al. The power and the promise: working with communities to analyze data, interpret findings, and get to outcomes. Am J Public Health 2008;98(8):1407–1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hemingway A. Determinants of coronary heart disease risk for women on a low income: literature review. J Adv Nurs 2007;60(4):359–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brand A, Brand H. Schulte in den Baumen T. The impact of genetics and genomics on public health. Eur J Hum Genet 2008;16(1):5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaikh BT. Understanding social determinants of health seeking behaviours, providing a rational framework for health policy and systems development. J Pak Med Assoc 2008;58(1):33–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackwell AG, Colmenar R. Community-building: from local wisdom to public policy. Public Health Rep 2000;115(2–3):161–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fawcett SB, Lewis RK, Paine-Andrews A, et al. Evaluating community coalitions for prevention of substance abuse: the case of Project Freedom. Health Educ Behav 1997;24(6):812–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolff T. Community coalition building—contemporary practice and research: introduction. Am J Community Psychol 2001;29(2):165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark NM, Malveaux F, Friedman AR, eds Community coalitions and control of chronic disease: the Allies Against Asthma approach. Health Promot Pract 2006;7(suppl 2):5S–166S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander JA, Weiner BJ, Metzger ME, et al. Sustainability of collaborative capacity in community health partnerships. Med Care Res Rev 2003;60(suppl 4):130S–160S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meister JS, Guernsey de Zapien J. Bringing health policy issues front and center in the community: expanding the role of community health coalitions. Prev Chronic Dis 2005;2(1):A16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brownson RC, Smith CA, Pratt M, et al. Preventing cardiovascular disease through community-based risk reduction: the Bootheel Heart Health Project. Am J Public Health 1996;86(2):206–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooker S, Cirill L. Evaluation of community coalitions ability to create safe, effective exercise classes for older adults. Eval Program Plann 2006;29(3):242–250 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher EB, Strunk RC, Sussman LK, Sykes RK, Walker MS. Community organization to reduce the need for acute care for asthma among African American children in low-income neighborhoods: the Neighborhood Asthma Coalition. Pediatrics 2004;114(1):116–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fries JF, Bloch DA, Harrington H, Richardson N, Beck R. Two-year results of a randomized controlled trial of a health promotion program in a retiree population: the Bank of America Study. Am J Med 1993;94(5):455–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gale BJ. Faculty practice as partnership with a community coalition. J Prof Nurs 1998;14(5):267–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minkler M. Community organizing among the elderly poor in the United States: a case study. Int J Health Serv 1992;22(2):303–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gagnon F, Turgeon J, Dallaire C. Healthy public policy: a conceptual cognitive framework. Health Policy 2007;81(1):42–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman AR, Butterfoss FD, Krieger JW, et al. Allies community health workers: bridging the gap. Health Promot Pract 2006;7(suppl 2):96S–107S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wynn TA, Johnson RE, Fouad M, et al. Addressing disparities through coalition building: Alabama REACH 2010 lessons learned. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2006;17(suppl 2):55–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bigby J, Ko LK, Johnson N, David MM, Ferrer B, Boston REACH. 2010 Breast and Cervical Cancer Coalition: a community approach to addressing excess breast and cervical cancer mortality among women of African descent in Boston. Public Health Rep 2003;118(4):338–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolda EJ, Saucier P, Maddox GL, Wetle T, Lowe JI. Governance and management structures for community partnerships: experiences from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's community partnerships for older adults program. Gerontologist 2006;46(3):391–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butterfoss FD, Morrow AL, Webster JD, Crews RC. The Coalition Training Institute: training for the long haul. J Public Health Manag Pract 2003;9(6):522–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butterfoss FD. The coalition technical assistance and training framework: helping community coalitions help themselves. Health Promot Pract 2004;5(2):118–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feinberg ME, Greenberg MT, Osgood DW. Readiness, functioning, and perceived effectiveness in community prevention coalitions: a study of communities that care. Am J Community Psychol 2004;33(3–4):163–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giachello AL, Arrom JO, Davis M, et al. Reducing diabetes health disparities through community-based participatory action research: the Chicago Southeast Diabetes Community Action Coalition. Public Health Rep 2003;118(4):309–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metzger ME, Alexander JA, Weiner BJ. The effects of leadership and governance processes on member participation in community health coalitions. Health Educ Behav 2005;32(4):455–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenthal MP, Butterfoss FD, Doctor LJ, et al. The coalition process at work: building care coordination models to control chronic disease. Health Promot Pract 2006;7(suppl 2):117S–126S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kramer JS, Philliber S, Brindis CD, et al. Coalition models: lessons learned from the CDC's community coalition partnership programs for the prevention of teen pregnancy. J Adolesc Health 2005;37(suppl 3):S20–S30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fawcett SB, Francisco VT, Paine-Andrews A, Schultz JA. A model memorandum of collaboration: a proposal. Public Health Rep 2000;115(2–3):174–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allies Against Asthma List of asthma coalitions in the United States. Available at: http://cmcd.sph.umich.edu/allies-against-asthma.html. Accessed February 4, 2010

- 34.Hill A, De Zapien JG, Staten LK, et al. From program to policy: expanding the role of community coalitions. Prev Chronic Dis 2007;4(4):A103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saewyc EM, Solsvig W, Edinburgh L. The Hmong Youth Task Force: evaluation of a coalition to address the sexual exploitation of young runaways. Public Health Nurs 2008;25(1):69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vasquez VB, Minkler M, Shepard P. Promoting environmental health policy through community based participatory research: a case study from Harlem, New York. J Urban Health 2006;83(1):101–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bencivenga M, DeRubis S, Leach P, Lotito L, Shoemaker C, Lengerich EJ. Community partnerships, food pantries, and an evidence-based intervention to increase mammography among rural women. J Rural Health 2008;24(1):91–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collins D, Johnson K, Becker BJ. A meta-analysis of direct and mediating effects of community coalitions that implemented science-based substance abuse prevention interventions. Subst Use Misuse 2007;42(6):985–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis RK, Paine-Andrews A, Fawcett SB, et al. Evaluating the effects of a community coalition's efforts to reduce illegal sales of alcohol and tobacco products to minors. J Community Health 1996;21(6):429–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Splett PL, Erickson CD, Belseth SB, Jensen C. Evaluation and sustainability of the Healthy Learners Asthma Initiative. J Sch Health 2006;76(6):276–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Butterfoss FD, Gilmore LA, Krieger JW, et al. From formation to action: how Allies Against Asthma coalitions are getting the job done. Health Promot Pract 2006;7(suppl 2):34S–43S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lachance LL, Houle CR, Cassidy EF, et al. Collaborative design and implementation of a multisite community coalition evaluation. Health Promot Pract 2006;7(suppl 2):44S–55S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma—full report 2007. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma. Accessed February 4, 2010

- 44.Evans R, Gergen PJ, Mitchell H, et al. A randomized clinical trial to reduce asthma morbidity among inner-city children: results of the National Cooperative Inner-City Asthma Study. J Pediatr 1999;135(3):332–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark NM, Gong ZM, Wang SJ, Lin X, Bria WF, Johnson TR. A randomized trial of a self-regulation intervention for women with asthma. Chest 2007;132(1):88–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cabana MD, Slish KK, Nan B, Lin X, Clark NM. Asking the correct questions to assess asthma symptoms. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2005;44(4):319–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joseph CL, Havstad S, Anderson EW, Brown R, Johnson CC, Clark NM. Effect of asthma intervention on children with undiagnosed asthma. J Pediatr 2005;146(1):96–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Ferrie PJ, Griffith LE, Townsend M. Measuring quality of life in the parents of children with asthma. Qual Life Res 1996;5(1):27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clark NM, Gong M, Brown RW, et al. Influences on childhood asthma in low-income communities in China and the United States. J Asthma 2005;42(6):493–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clark NM, Gong M, Kaciroti N, et al. A trial of asthma self-management in Beijing schools. Chronic Illn 2005;1(1):31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osman LM, Baxter-Jones AD, Helms PJ. Parents' quality of life and respiratory symptoms in young children with mild wheeze. Eur Respir J 2001;17(2):254–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reichenberg K, Broberg AG. The Paediatric Asthma Caregiver's Quality of Life Questionnaire in Swedish parents. Acta Paediatr 2001;90(1):45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valerio MA, Gong ZM, Wang S, Bria WF, Johnson TR, Clark NM. Overweight women and management of asthma. Womens Health Issues 2009;19(5)300–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Halterman JS, Yoos HL, Conn KM, et al. The impact of childhood asthma on parental quality of life. J Asthma 2004;41(6):645–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodriguez MA, Winkleby MA, Ahn D, Sundquist J, Kraemer HC. Identification of population subgroups of children and adolescents with high asthma prevalence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156(3):269–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lara M, Morgenstern H, Duan N, Brook RH. Elevated asthma morbidity in Puerto Rican children: a review of possible risk and prognostic factors. West J Med 1999;170(2):75–84 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brown R, Bratton SL, Cabana MD, Kaciroti N, Clark NM. Physician asthma education program improves outcomes for children of low-income families. Chest 2004;126(2):369–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson SR, Yamada EG, Sudhakar R, et al. A controlled trial of an environmental tobacco smoke reduction intervention in low-income children with asthma. Chest 2001;120(5):1709–1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clark NM, Gong M, Schork MA, et al. Long-term effects of asthma education for physicians on patient satisfaction and use of health services. Eur Respir J 2000;16(1):15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Senn S, Stevens L, Chaturvedi N. Repeated measures in clinical trials: simple strategies for analysis using summary measures. Stat Med 2000;19(6):861–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data 2nd ed New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yuan YC. Multiple Imputation for Missing Data: Concepts and New Developments Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 63.SAS [computer program]. Version 9.1 Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lara M, Rosenbaum S, Rachelefsky G, et al. Improving childhood asthma outcomes in the United States: a blueprint for policy action. Pediatrics 2002;109(5):919–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Galbreath AD, Smith B, Wood PR, et al. Assessing the value of disease management: impact of 2 disease management strategies in an underserved asthma population. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008;101(6):599–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bender B, Zhang L. Negative affect, medication adherence, and asthma control in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;122(3):490–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Diette GB, Patino CM, Merriman B, et al. Patient factors that physicians use to assign asthma treatment. Arch Intern Med 2007;167(13):1360–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]