Abstract

Although the public health impact of direct-to-consumer (DTC) pharmaceutical advertising remains a subject of great controversy, such promotion is typically understood as a recent phenomenon permitted only by changes in federal regulation of print and broadcast advertising over the past two decades. But today's omnipresent ads are only the most recent chapter in a longer history of DTC pharmaceutical promotion (including the ghostwriting of popular articles, organization of public-relations events, and implicit advertising of products to consumers) stretching back over the twentieth century. We use trade literature and archival materials to examine the continuity of efforts to promote prescription drugs to consumers and to better grapple with the public health significance of contemporary pharmaceutical marketing practices.

DIRECT-TO-CONSUMER (DTC) advertising of prescription drugs has mushroomed from a few isolated and relatively sensational cases in the early 1980s to an omnipresent feature of American consumer society, powered in 2005 by $4.2 billion in promotional dollars.1 This explosive growth—most intense in the past decade—has inverted the role of physician as learned intermediary in the flow of information about prescription drugs and replaced it with what is, in theory, a more egalitarian consumerist model of health information.

Considerable controversy persists, however, about the impact of DTC advertising on American public health and the doctor–patient relationship.2 Whereas some argue that advertising has indeed democratized access to important new medications,3 others decry the coarsening of medical discourse, the diminution of physicians' authority, and the risks of overprescription and inappropriate prescription by the manipulation of consumer awareness and consequent pressure on prescribers.4

The lively debate among scholars and policymakers about consumer-oriented pharmaceutical promotion has, for the most part, focused on the explicit regulation of prescription drug advertisements in print and broadcast media,5 following a series of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidances in 1985, 1997, and 1999. However, as revealed by recent scholarship,6 tort litigation,7 and congressional hearings regarding pharmaceutical promotion to physicians,8 explicitly regulated promotional practices such as advertisements and sales visits have long been flanked by such unregulated, implicit forms of promotion as the ghostwriting of scientific articles and control of the content of continuing medical education.9

We present new historical evidence to demonstrate that such “shadow” marketing has also been employed in the DTC promotion of prescription drugs for over a half century. These proto-DTC campaigns flourished at the boundaries of acceptable self-regulation by the pharmaceutical industry as it negotiated attempts at external regulation by the medical profession and the regulatory state. The vitality and persistence of DTC pharmaceutical promotion in the twentieth century suggest that contemporary DTC advertising is not merely a recent aberration that can be fixed by returning to an earlier and better time, and that attempts to wrestle with the consequences of popular marketing would do best to focus on managing, not eradicating, this longstanding element of public life.

ETHICAL MARKETING AND INSTITUTIONAL ADVERTISING

Federal regulation of pharmaceutical marketing has been central to the definition of legitimate therapeutics and the role of physician as learned intermediary since the first decades of the twentieth century. The regulation of marketing in the modern prescription drug industry, however, preceded federal or state involvement. In the late nineteenth -century, a number of drug and chemical firms in Europe and North America denounced the raucous commercial market for patent medicine producers and restyled themselves as “ethical” houses devoted to professional therapeutics. Whereas patent medicine makers hid the contents of their nostrums and touted expansive therapeutic claims to consumers via popular advertisements in magazines, newspapers, and traveling medicine shows,10 ethical drug firms sold standardized preparations of the materia medica as designated in the United States Pharmacopoeia and marketed their wares only to the medical profession in keeping with the American Medical Association's (AMA) Code of Ethics.11

Aside from the voluntary decision to follow the AMA Code of Ethics, no formal regulation defined the “ethical” drug industry in the nineteenth century. This regulatory void began to close in 1906 with the passage of the Pure Food and Drugs Act. The act created the FDA, which was given the authority to ensure that drug labeling reflected standards of strength, quality, and purity, and, after the Sherley Amendment of 1912, to prohibit fraudulent therapeutic claims on drug labels.

When the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) was created in 1914 to regulate interstate advertising, journal advertising to physicians was exempted in deference to the unique expertise that medical professionals were understood to bring to the interpretation of pharmaceutical promotion. This created a favorable legal framework for what had been a matter of corporate culture. Ethical houses, unlike patent medicine companies, continued to enjoy few restrictions on their marketing as long as it remained restricted to medical journals, direct mail to physicians, and office- and hospital-based “detailing” of physicians by sales representatives. The professional regulation of ethical marketing to physicians was mediated through the Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry of the AMA, whose “Seal of Acceptance” program governed access to the pages of the Journal of the American Medical Association and other reputable journals.

But even as new regulations added substance to the patent–ethical divide, distinctions between professional and popular drug marketing became more complicated in the first half of the twentieth century. Although in principle all drugs could be divided between patent and ethical, many pharmaceutical companies produced both classes of drugs. Smith Kline and French, for example, was a classic ethical firm that continued to sell its proprietary nostrum “Eskay's Neurophosphates” well into the twentieth century.12 Many ethical firms began to diversify their product lines to include “household items” (such as topical disinfectants and milk of magnesia) that would now be lumped into the category of over-the-counter medications.

As they diversified, companies began to explore the possibility of marketing to consumers by promoting the institutional brand of the ethical firm as a whole. Examples of such institutional advertising can be seen in two storied ethical firms, E. R. Squibb & Sons and Parke, Davis & Company. Initially, both companies had restricted all promotion to the medical and pharmaceutical professions. But beginning in the 1920s, as both firms diversified into “household items,” each developed widespread, highly visible institutional advertising campaigns in popular magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post and Ladies Home Journal. These ads mentioned no specific products or therapeutic indications. Instead, they praised the achievements of modern medical science, lauded the heroic figure of the modern physician, and testified to the high standards and quality of modern pharmaceuticals.

Squibb's advertisements, for example, touted the honor and integrity of the Squibb brand, depicting it (literally) as an edifice of “reliability” supported by pillars of “uniformity,” “purity,” and “efficacy.” Seeking to reassure physicians of the soundness of ethical marketing even as they approached its untested boundaries, Squibb ads explicitly warned against the danger of self-medication and stressed the importance of seeking medical advice from physicians (Figure 1).13 Similar advertisements by Parke, Davis in the 1920s and 1930s (based around themes such as “Fortress of Health,” “Your Doctor and You,” and “See Your Doctor”) similarly portrayed physicians as everyday heroes of twentieth-century America while warning of the evils of self-medication (Figure 2).14

FIGURE 1.

Institutional advertisement for E. R. Squibb & Sons touted the brand's integrity while playing up the importance of seeking medical advice.

Source. Ladies' Home Journal, June 1924, 106.

FIGURE 2.

Parke, Davis's institutional ads portrayed physicians as everyday heroes while warning of the evils of self-medication.

Source. Your Doctor and You: Recent Advertisements in a Series Which Has Been Appearing in Leading Magazines (Detroit: Parke, Davis and Co., 1934).

These DTC advertisements stood in sharp contrast to product-specific pharmaceutical advertisements appearing in the medical journals of the time. But with their “See Your Doctor” message and their decorous -refusal to name specific drugs, they also sought to distinguish themselves from the crass commercialism of the patent medicine market. Institutional advertising, in other words, advertised the concept of ethical pharmaceuticals, and thus—ironically—reinforced rather than undercut the edifice of ethical marketing. This was no accident, according to market observers. “Parke, Davis advertises to public without losing its ethical standing,” the advertising journal Printer's Ink trumpeted:

Parke, Davis has always felt that unless some way could be found whereby the company could advertise ethically, that is without making extravagant claims or encouraging self-medication, advertising would be dangerous rather than helpful… . When the company began to consider its advertising problems it immediately threw out any possible thought of trying to push by name any of the pharmaceutical or biological products which by their nature should be prescribed by physicians. Advertising such products, the company felt, would be obviously not ethical.15

In similar fashion, marketers at Squibb took pains to recruit physicians into the firm's marketing campaigns. As the company reassured readers of the Journal of the American Medical Association in a 1929 full-page advertisement, their DTC campaign was designed to draw closer the bond of confidence between physician and patient by “telling the layman how completely his physician is equipped to guard him from disease.”16 Thus, Squibb maintained, advertisements for their household products would work to strengthen physicians' key role as expert intermediaries in the use of ethical pharmaceuticals.

By the middle of the twentieth century, then, at the height of ethical marketing, DTC advertising by pharmaceutical companies had become standard fare. And yet these campaigns actually worked to strengthen the cultural and regulatory boundaries separating ethical drug marketing from the rest of America's intensifying commercial culture. By promoting ethical firms as producers of high-quality, innovative therapeutics while simultaneously insisting on the priority of the physician in selecting and prescribing pharmaceutical agents, these advertisements reinforced both the scientific legitimacy of the ethical pharmaceutical industry and the role of the physician as learned intermediary in ethical drug use.

PUBLIC RELATIONS AND THE PRESCRIPTION DRUG CONSUMER

The market for prescription drugs grew rapidly in the second half of the twentieth century along with a postwar boom in novel synthetic pharmaceutical products, a general rise in the consumption of health care, and new federal regulations that required a prescription for the sale of ethical pharmaceuticals. As brand-name drugs became increasingly important to physicians' practices and to pharmaceutical company profits, competition between firms heightened.17 The resultant increase in journal advertising budgets created a financial incentive for the AMA, in 1955, to discontinue its Seal of Acceptance Program and open up the pages of the Journal of the American Medical Association to a less-discriminating but higher-volume advertising policy.18 Looking for ways to improve their market position, a growing number of pharmaceutical companies looked beyond “institutional” advertising to a variety of creative means to communicate their own brand names to physicians and to the general public. By the mid-1950s, the popular promotion of brand-name prescription drugs through public relations and new-generation institutional advertisements had become a thriving and unregulated gray area of DTC marketing.

The 1950s were a propitious time for the new pharmaceutical advertisers. The popular promise of “miracle drugs” elicited general admiration of the industry by physicians and the consumer public, which gave companies a margin for error that they had not always had. “Lay publicity has seemed—I want to emphasize ‘seemed’—inconsistent with ethical advertising and promotion,” one industry executive said in 1958, but “the doctor's attitude towards publicity has changed considerably.”19

The 1950s also saw a boom in industrial public relations, as corporations took the lead in selling the “free market system” to the public and the federal government.20 The pharmaceutical industry had traditionally used public relations to attract investors and maintain institutional visibility; now it became their preferred vehicle for new marketing campaigns. In 1953, the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association urged all pharmaceutical firms to develop their own public relations offices and developed a primer in public relations for the industry.21 By 1956, the heads of all major American pharmaceutical companies had pooled together to create an industry-wide public relations office, the Health News Institute, with Chet Shaw, the former executive editor of Newsweek, hired as the first director.22

Formally, public relations was distinguished from advertising in that it promoted the name of the firm or the interest of the industry as a whole instead of a single branded product.23 In the post–World War II era, however, the pharmaceutical industry began to use public relations techniques in new ways that came very close to popular advertising of specific branded products. Parke, Davis's early consumer-oriented advertisements, for example, had initially avoided all mention of the company's products. Beginning in the 1950s, however, new popular advertisements began to promote the company's own innovative drugs, especially in the growing field of prescription antihistamines.

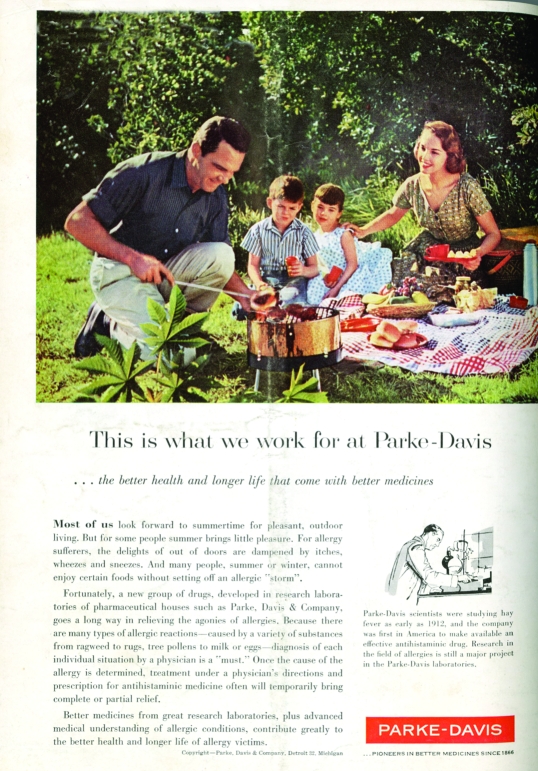

One 1960 advertisement in the popular magazine Today's Health, titled “This Is What We Work For at Parke, Davis,” featured a formerly allergy-ridden family enjoying a campfire together (Figure 3). “Fortunately,” the text ran,

a new group of drugs, developed in research laboratories of pharmaceutical houses such as Parke, Davis & Company, goes a long way in relieving the agonies of allergies.

FIGURE 3.

By 1960, Parke, Davis's institutional ads were implicitly promoting a specific company product, in this case Benadryl (diphenhydramine).

Source. Today's Health, February 1960.

Although the ad was careful to state that “diagnosis of each individual situation by a physician is a ‘must’,” it nonetheless implicitly promoted a specific Parke, Davis product: the company held the patent on Benadryl (diphenhydramine), the first and most widely used oral antihistamine.24

Another creative attempt to indirectly advertise a brand-name prescription drug to the general consumer came to public attention during a 1964 Senate investigation of the pharmaceutical industry. The previous year, Roche Pharmaceuticals had placed advertisements for the tranquilizer Librium in special copies of Time magazine that were mailed to doctors for use in their waiting rooms. Although Roche was censured by Congress and the offending issues of Time disappeared, Parke, Davis continued to advertise the benefits of antihistamines well into the mid-1960s.25

These efforts at what might be called “indirect-to-consumer advertising” were accompanied in the 1950s and 1960s by an energetic exploration of nonadvertising marketing through newsreels, article placements, event planning, and other domains of public relations. For example, J. B. Roerig & Co, a division of Pfizer, released a newsreel in 1957 to help launch Atarax (hydroxyzine), its new minor tranquilizer. The film featured an anxious husband, unable to sleep, who is soothed and educated by his well-informed wife who reads to him about the physiology of tension. After teaching viewers about stress and recommending a few simple relaxation techniques, the film switched setting from a bedroom to a laboratory, and the narrator noted that relaxation techniques did not work for everyone. For the rest, the announcer reassured, there were new medicines that could provide the “mental and physical state of bliss” known as “ataraxia.” These medicines were called “ataraxic” drugs—the camera zoomed in on the label of a medicine bottle hovering magically above the lab's workbench. “Ataraxic” was a clever ploy: there actually was a similar term for tranquilizers circulating at the time, but it was spelled “ataractic.” Through creative respelling and capitalization, the film nudged viewers toward Roerig's brand Atarax.26

Companies also attracted popular media coverage by adding attention-grabbing gimmicks to their medical marketing. Carter Products pursued this strategy with their blockbuster tranquilizer Miltown (meprobamate) in 1958 by commissioning a sculpture from Salvador Dali for their exhibit at that year's AMA meeting.27 Carter also fed stories to gossip columnists about comedian Milton Berle's love of the new pill, which led to popular jokes regarding “Miltown Berle” and the “Miltini.”28 In 1961, Roche Pharmaceuticals followed Carter's lead by using a publicity stunt to launch its own tranquilizer, Librium; reporters were called in to watch company researchers use the drug to calm a wild lynx. Pictures of the lynx filled three pages of Life magazine, and Time reported on the story too, faithfully reiterating Roche's marketing claim that Librium “comes close to producing pure relief from strain without drowsiness or dulling of mental processes.”29

Such publicity stunts were coordinated with longitudinal public relations campaigns run by the Health News Institute and sister public relations outfit the Medical and Pharmaceutical Information Bureau (MPIB), and deployed time-tested tactics for attracting favorable media attention to particular companies and their products. Companies issued press releases based on clinical studies, mailed entire press release packages to newspapers, provided favored science writers early access to clinical materials, and made experts available for interviews or educational programs.30 One favored MPIB strategy was to offer newspapers small boxes of text called “short shorts” to fill small spaces between stories, and to provide radio and television stations with small broadcast news items called “featurettes” for filling dead air time. A longer version of the same technique was on display in the MPIB's “Spotlight on Health” column, which reached over 2500 newspapers across the nation. Like the other “educational” materials, the column saved newspapers money (it was already typeset) while ostensibly helping them to serve the public good by teaching about health topics. Also like the other materials, the Spotlight highlighted brand-name medicines.31 The MPIB employed a similar product placement strategy with radio and TV scripts offered to stations for slow time slots.32

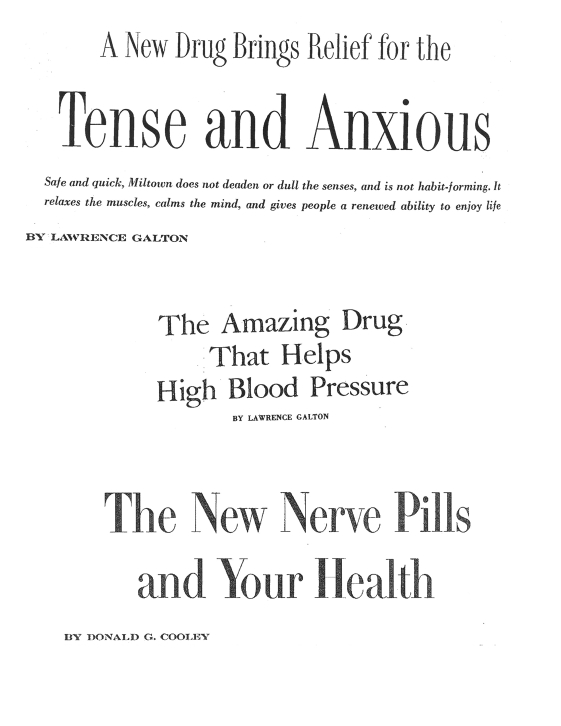

Perhaps the highest form of industry-ghostwritten media coverage was an omnipresent form of reportage called the “backgrounder.” Backgrounders were seemingly legitimate news articles about new pharmaceutical developments that ran in popular magazines. Written by journalists who appeared to be neutral, professional freelancers, they had actually been commissioned by the MPIB working through a stable of regular science writers. When they reported on miracle drugs (which they almost invariably did), they highlighted specific brand-name medicines—but left them uncapitalized so that they looked like chemical or generic names, thus avoiding the appearance of impropriety. Some of them went so far as to “launch” a new class of medicines by listing all the competing brands along with the manufacturer and salient marketing claims.33

Two prominent MPIB writers, Lawrence Galton and Donald Cooley, serve as useful examples of how this worked (Figure 4).34 Each published more than 100 articles, mostly on pharmaceutical issues. Galton regularly placed columns in Family Circle, Cosmopolitan, and Successful Farming with titles like “Aureomycin: It Fights Germs Penicillin Won't,” “Good News for Hay Fever and Asthma Victims,” and “The Amazing Drug That Helps Blood Pressure.” Galton's article on Aureomycin, for example, opened with this salesman's pitch: “Not just a hope for the future but available right now on your doctor's prescription, a powerful new drug promises to play a heroic role in the health of your family.” Galton went on to claim (falsely) that “aureomycin” (left uncapitalized) was “the first drug to knock out ‘virus’ pneumonia.”35 Galton also gushed over the tranquilizer Miltown in Cosmopolitan, praising it for resolving dozens of complaints, including skin problems, “the blues,” heat sensitivity, fatigue, social discomfort, and ill-behaved children. It did all this, moreover, “free of penalty” because the drug was “not habit-forming” (in fact, Miltown was quite addictive).36

FIGURE 4.

“Backgrounders” like these three brought favorable attention to brand-name drugs under the guise of ordinary science journalism.

Source. D. Cooley, “The New Nerve Pills and Your Health,” Cosmopolitan, January 1956, 68–75; L. Galton, “The Amazing Drug That Helps High Blood Pressure,” Pageant, April 1958,: 96–99; L. Galton, “A New Drug Brings Relief for the Tense and Anxious, Cosmopolitan, August 1955, 82–83.

Donald Cooley wrote articles like “Will Wonder Drugs Never Cease!” “New Victories Predicted for Medicine!” and “New Drug That Awakens Energies!” mostly placed in Better Homes and Gardens, Science Digest, Cosmopolitan, and Today's Health. A particularly striking Cooley article in Pageant magazine praised the prescription-only diet pill Levener by deriding the advertising hype of its over-the-counter competitors. “Prescription pills for reducing [weight] are never advertised to the public,” it admonished, with no apparent sense of irony. Cooley also wrote under the pen name Morgan Deming—initials M. D.—in such venues as the pulp magazine True Confessions.37 Like Galton, Cooley also did his share for Miltown in the pages of Cosmopolitan, declaring that—for example—the tranquilizer had put an end to “that tired feeling” and had helped “frigid women who abhorred marital relations [to] respond more readily to their husbands' advances.”38

At the height of the ethical era in American pharmaceuticals, then, an increasingly competitive and increasingly profitable industry vigorously explored a range of shadow marketing techniques designed to work like DTC advertising without technically crossing the Rubicon and abandoning the ethical label. Aided by muckraking exposés of the industry by Congress and investigative journalists in the 1960s and 1970s, these ubiquitous and almost entirely unregulated marketing campaigns subtly altered the “ethical” label, anchoring it more on its new prescription-only status than on its older claim of forgoing popular advertising. But pharmaceutical houses still clung to their anticommercial reputations, unwilling to—or perhaps, given the expansive world of shadow marketing they had created, not needing to—mount a direct challenge to the traditional ban on DTC advertising.

FORMAL DIRECT-TO-CONSUMER ADVERTISING

By the early 1980s, at least some pharmaceutical companies, chafing at the limits of informal and indirect marketing, were ready to test the waters of explicit advertising. This had been a surprisingly gray area marked by a complex interplay of industrial, professional, and regulatory developments since the original Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906. One key development ushered in by the Congressional Food and Drug Act and its amendments in 1938 and 1951 was the establishment of a formal, legal category of drugs that could be used only under the supervision of a licensed physician—that is, prescription-only drugs.39 The new category created ambiguity about which federal agency (the FTC or FDA) was responsible for overseeing pharmaceutical promotion to the general consumer. Not until the Kefauver-Harris Amendments of 1962 did the FDA receive explicit regulatory authority over advertisements for prescription-only drugs, which was subsequently interpreted to encompass broader forms of promotional messages which endorsed a drug product and were sponsored by a manufacturer, such as press releases.40 Subsequent FDA regulations imposed two major criteria on prescription drug advertisements: (1) a “brief summary,” which required a presentation of all side effects, contraindications, warnings, and indications for use, and (2) “fair balance,” which entailed an even presentation of risks and benefits in any given piece of advertising.

Until the 1980s, regulatory debates over formal and informal drug promotion focused almost exclusively on promotion to physicians through sales representatives41 and industry-funded continuing medical education programs.42 Federal regulators (and those who watched them) paid relatively little attention to drug marketing aimed at general consumers; the FDA's concern with the provenance of information to consumers at this point was focused on proposals for universal package insert requirements.43 This inattention did not change until 1981, when provocative acts by two drug companies forced the FDA to consider the matter. First, the British firm Boots Pharmaceuticals ran general advertisements touting the price of its (prescription-only) version of ibuprofen, Rufen. Shortly thereafter, Merck ran a prominent advertisement for its new antipneumococcal vaccine, Pneumovax. Faced with a question of regulatory jurisdiction that it had not previously considered, FDA Commissioner Arthur H. J. Hayes asked the industry for a voluntary moratorium while the agency studied the issue.44

Initial studies showed mixed results on consumers' ability to absorb information on benefits and risks from DTC advertising.45 Meanwhile, consumer demand for more information about prescription medicines had grown alongside the importance of those drugs in the therapeutic armamentarium.46 In 1985, the FDA issued a notice in the Federal Register claiming jurisdiction over the DTC advertising of prescription drugs, and indicating that the prior standards of “fair balance” and “brief summary” would provide American consumers with an adequate safeguard from deceptive or misleading claims.

These two requirements effectively limited full product-specific DTC advertising to print media, where fair balance of drug risks could be presented in small type. The cost of purchasing time for description of side effects would be prohibitive in broadcast media. Thus, DTC advertising in the broadcast media tended toward health-seeking campaigns, which emphasized a disease or medical condition but not a specific drug, or reminder campaigns, which promoted a drug name in the explicit absence of any therapeutic claims.47 Over the course of the 1990s, resulting television and radio advertisements took on a surreal, disconnected quality, exemplified by the division of marketing for Schering-Plough's nonsedating antihistamine Claritin (loratidine): one set of advertisements praised promising new developments in antiallergy remedies but did not mention Claritin, while others featured the pill and its logo and promised “blue skies” without explaining what, in therapeutic terms, that might mean.

Concerned that consumers were confused by the choppy nature of broadcast DTC advertising, the FDA convened a 1995 hearing on the putative risks and benefits of easing its regulation. Two years later, in 1997, the FDA issued a draft guidance on DTC advertising, followed by a final guidance in 1999 that redefined “adequate provision” of risks and benefits to include reference to a toll-free number or Web site. This opened the door for federally regulated DTC advertising over broadcast media, and the industry responded quickly. Total DTC advertising in 1989 was estimated at $12 million; it reached $340 million in 1995, tripled to $1.1 billion in 1998, the year after the FDA's draft guidance, and doubled again to $2.24 billion by 1999, the year of the FDA's final regulatory decision on broadcast DTC advertising. It has doubled again in the decade since then.48

Federal regulation of other forms of promotion to consumers, however, has followed a less straightforward path. At the same time that the FDA was wrestling with the Boots Rufen case in the early 1980s, it declared that press releases by pharmaceutical manufacturers would be considered a form of labeling and would thus fall under its jurisdiction. Both instigating cases involved nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with large markets. In a 1982 warning letter to Pfizer regarding its painkiller Feldene (piroxicam), the FDA declared that it considered any press release written “by or on behalf of the manufacturer and disseminated to the press to be labeling for the product.”49 This was followed two weeks later by a letter accusing Eli Lilly of issuing false and misleading materials to the general public in its press kit for the new painkiller Oraflex (benoxaprofen), and demanding redress. In ensuing decisions regarding Upjohn's hair-restorer Rogaine (minoxidil topical) and Ortho Pharmaceuticals' antiacne agent Retin-A (tretinoin topical), the FDA continued to insist that company press releases needed to give fair balance to the benefits and risks of drugs. If they had received financial support from a drug company, even press releases given by third-party investigators were subject to the same regulatory oversight as the drug companies themselves.50

The explicit regulation of press releases, however, has captured only a fraction of the nonadvertising forms of pharmaceutical promotion that have since been aimed at American consumers. Indeed, in an era of intersecting digital media, one might ask who needs press releases when consumers continually encounter celebrity endorsements, “astroturfing” (planned and industry-funded “grassroots” disease awareness programs), friendly (or for-hire) science writers, and the like? Although the Federal Physician Payments Sunshine Act, proposed in 2009 by Senators Charles Grassley (R-IA) and Herb Kohl (D-WI), would increase the transparency of covert pharmaceutical promotion to researchers and physicians, it would do little to expose the covert marketing of pharmaceuticals to the general public. We are left in the same strange situation that has prevailed for much of the twentieth century: explicit forms of advertising are carefully monitored and regulated but widely decried, while informal or indirect promotions still flourish with virtually no oversight.

OVERT AND COVERT DIRECT-TO-CONSUMER MARKETING

We have employed original archival research and a narrative review of clinical, policy, and trade literatures to reveal how recent forms of DTC advertising fit within a longstanding twentieth-century lineage of popular pharmaceutical promotion. This brief review has limitations: it cannot claim to be a complete study of the subject because of the spottiness of archival records, a poorly indexed trade literature, and the general difficulty of documenting a process that has historically sought to obscure itself. Moreover, like most histories, it cannot answer the most pressing (but misleading) question of whether DTC advertising helps or harms the public health. It does, however, definitively document the popular promotion of prescription drugs throughout most of the twentieth century—a history with real significance for current efforts to understand and grapple with current forms of DTC advertising.

There are at least two broad lessons to be gleaned from this history. The first relates to the complexity of the flow of information about medicines. As this article has shown, federal regulatory categories have been inadequate to capture the bewildering profusion of marketing techniques employed by the pharmaceutical industry. “Ethical,” “advertising,” “labeling,” “education,” “public relations”: each of these has meaning, technically, but they are of limited value when companies routinely pursue broader marketing strategies that synergistically combine all of these, often in the same campaign. A historical assessment of the promotion of prescription drugs to consumers helps to provide a more complete taxonomy of these efforts, supplementing named and formal channels of information with prominent, persistent, and well-used informal pathways. Only by knowing this informational landscape—by considering it holistically in terms of the packaging and circulation of ideas, rather than by defining particular kinds of marketing to focus on—can observers hope to evaluate and ultimately regulate its many traffickers.

Those “many traffickers” constitute a second, related point: the great diversity of invested parties involved in marketing campaigns. Pharmaceutical promotion does not only involve manufacturers, advertisers, and consumers. Rather, the social networks involved in pharmaceutical promotion are broad and employ artists, journalists, gossip columnists, science writers, editors, filmmakers, physicians, public relations firms, researchers, medical educators, and many others in popular and professional spheres. In many cases it has benefited all parties in these networks to obscure or even deny that marketing is taking place. Taking careful stock of this hidden economy of pharmaceutical promoters gives a more complete picture of how the system works and which actors need to be considered in any political or regulatory efforts.

Both of these taxonomic points are important because of a third, most central historical fact: the surprising continuity of drug marketing over time. It is hardly surprising that the form and content of pharmaceutical promotion has changed over the twentieth century, with particularly salient expansion of the array of promotional media available to pharmaceutical marketers in the past 20 years. Beneath this evolution, however, one finds a surprising consistency in the range of techniques by which companies delivered information about their products to the general public. True, popular advertisements have evolved from institutional, “See Your Doctor” types of campaigns to more aggressive “Ask Your Doctor” campaigns centered explicitly around brand-name medicines. But throughout, ordinary Americans still encountered paid advertising touting the importance, effectiveness, and scientific credentials of ethical and prescription-only drugs. Informal or indirect marketing may have changed even less, as newsreels, paid science journalism, gossip columns, and other tactics blended seamlessly with open celebrity endorsements and sponsored public educational campaigns. One way or another, informal, industry-sponsored information about drugs has been flowing through multiple channels for most of the past century.

The popular promotion of pharmaceuticals, in short, needs to be understood as a longstanding—if often covert—dimension of prescription drug marketing, not merely as a recent aberration. This should come as little surprise given the industry's location within a resolutely commercial—and consumerist—medical system. In such a system, there will always be ways for information about products to flow to people who may want to use them. Even at the height of the “ethical” marketing ideal, when pharmaceutical houses identified themselves not as “prescription only” so much as “noncommercial,” consumer-oriented drug marketing flourished. There is no golden age to return to by stamping out promotion. Instead, history suggests that reasonable goals would be to make the system transparent and efficiently regulated so that risks as well as benefits are communicated to consumers,51 and to manage the system so that it has the ability to aggressively respond to unreliable information.

As anyone involved with consumer advocacy knows, this is no easy task. Its difficulty is compounded by the disproportionate size of the DTC marketing budget for the pharmaceutical industry, which is nearly twice the budget for the entire FDA, let alone the office in charge of the regulation of DTC advertising.52 Moreover, pharmaceuticals represent an extreme case of a common situation, where consumers' choices are constrained by “learned intermediaries” in a market defined by vast and seemingly inescapable imbalances of knowledge and power. Nonetheless, for good and for ill, durable forms of popular pharmaceutical promotion—and a focus on the provision of drug-related information to consumers—have been a persistent part of the pharmaceutical marketplace for most of the twentieth century. By acknowledging this reality, and by adding informal and nonadvertising forms of drug promotion to a strengthened regulatory portfolio, we could at least take a step closer to the democratic world of medical information that drug advertisers claim to be helping to create.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Toby Sommer, Jerry Avorn, and the three anonymous reviewers from the American Journal of Public Health who reviewed the article.

Endnotes

- 1. J. M. Donohue, M. Cevasco, and M. B. Rosenthal, “A Decade of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising of Prescription Drugs,” New England Journal of Medicine 357, no. 7 (2007): 673–681. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. J. M. Donohue, “Direct to Consumer Advertising of Prescription Drugs: Does It Add to the Overuse and Inappropriate Use of Prescription Drugs or Alleviate Underuse?” International Journal of Pharmaceutical Medicine 20, no. 1 (2006): 17–24. DTC advertising of prescription drugs is, for the most part, a unique feature of American public health policy; although the European Union is currently debating a motion that would allow drug manufacturers to provide pamphlets of “nonpromotional” materials directly to consumers, apart from New Zealand, the United States remains the only country that explicitly permits the DTC promotion of pharmaceuticals. “Public Consultation (MLX 358): The European Commission Proposals on Information to Patients for Prescription Medicines,” available at http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Publications/Consultations/Medicinesconsultations/MLXs/CON046657 (accessed July 26, 2009)

- 3. A. F. Holmer, “Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Advertising Builds Bridges Between Patients and Physicians,” Journal of the American Medical Association 281, no. 4 (1999): 380–382. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4. B. Mintzes, M. L. Barer, R. L. Kravitz, et al., “Influence of Direct to Consumer Pharmaceutical Advertising and Patients' Requests on Prescribing Decisions: Two Site Cross Sectional Survey,” British Medical Journal 324 (2002): 278–279; D. A. Kessler and D. A. Levy, “Direct to Consumer Drug Advertising: Is It Too Late to Manage the Risks?” Annals of Family Medicine 5, no. 1 (2007): 4–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. W. L. Pines, “A History and Perspective on Direct-to-Consumer Advertising,” Food and Drug Law Journal 54 (1999): 489–518; M. S. Wilkes, R. A. Bell, and R. L. Kravitz, “Direct to Consumer Prescription Drug Advertising: Trends, Impact, and Implications,” Health Affairs 19 (2000): 110–128; F. B. Palumbo and C. D. Mullins, “The Development of Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Advertising Regulation,” Food and Drug Law Journal 57, no. 3 (2002): 423–443; J. Donohue, “A History of Drug Advertising: The Evolving Roles of Consumers and Consumer Protection,” Milbank Quarterly 84, no. 4 (2006): 659–699.

- 6. J. Greene, Prescribing by Numbers: Drugs and the Definition of Disease (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007)

- 7. A. S. Kesselheim and J. Avorn, “The Role of Litigation in Defining Drug Risks,” Journal of the American Medical Association 297, no. 3 (2007): 308–311. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8. C. S. Landefeld and M. A. Steinman, “The Neurontin Legacy: Marketing Through Misinformation and Manipulation,” New England Journal of Medicine 360, no. 2 (2009): 103–106. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9. D. Healy, “Shaping the Intimate: Influences on the Experience of Everyday Nerves,” Social Studies of Science 34 (2004): 219–245; C. Elliott, “Pharma Goes to the Laundry: Public Relations and the Business of Medical Education,” Hastings Center Report 34 (2004): 18–23; B. Moffatt and C. Elliott, “Ghost Marketing: Pharmaceutical Companies and Ghostwritten Journal Articles,” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 50 (2007): 18–31; S. Podolsky and J. Greene, “Pharmaceutical Promotion and Physician Education in Historical Perspective,” Journal of the American Medical Association 300, no. 7 (2008): 831–833; D. Herzberg, Happy Pills in America: From Miltown to Prozac (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009)

- 10. J. H. Young, The Toadstool Millionaires: A Social History of Patent Medicines in the United States Before Federal Regulation (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1961); N. Tomes, “The Great American Medicine Show Revisited,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 79, no. 4 (2005): 627–663. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11. J. Liebenau, Medical Science and Medical Industry: The Formation of the American Pharmaceutical Industry (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987)

- 12. N. Rasmussen, On Speed: The Many Lives of Amphetamines (New York: New York University Press, 2008)

- 13. R. Weicker, “Fights Self-Medication,” Printer's Ink, October 11, 1934, 12.

- 14. B. Hansen, Picturing Medical Progress From Pasteur to Polio: A History of Mass Media Images and Popular Attitudes in America (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2009); J. Metzl and J. Howell, “Great Moments: Authenticity, Ideology, and the Telling of Medical ‘History’,” Literary History 25, no. 2 (2006): 502–521. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15. C. B. Larrabee, “How Parke, Davis, Advertises Without Losing Its Ethical Standing,” Printer's Ink, August 9, 1928: 105–113, quote on 105–106.

- 16. As quoted in R. Marchand, Creating the Corporate Soul (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 177.

- 17. J. A. Greene, “Pharmaceutical Marketing Research and the Prescribing Physician,” Annals of Internal Medicine 146, no. 10 (2007): 742–748. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18. J. A. Greene and S. H. Podolsky, “Keeping Modern in Medicine: Pharmaceutical Promotion and Physician Education in Postwar America,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 83, no. 2 (2009): 331–377. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19. W. E. Jenkins, “Public Relations,” in Pharmaceutical Marketing Orientation Seminar, ed. R. G. Kedersha, 145–148, quote on 146 (New York: Pharmaceutical Advertising Club of New York, 1959)

- 20. Dominique Tobbell, “Allied Against Reform: Pharmaceutical Industry-Academic Physician Relations in the United States, 1945–1970,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 82, no. 4 (2008): 878–912; E. A. Fones-Wolf, Selling Free Enterprise: The Business Assault on Labor and Liberalism (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1994) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21. Public Relations Primer for the Drug Industry (Washington, DC: American Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association, 1953)

- 22. M. Woodward, “The Facts Behind the Story: Pharmaceutical Public Relations,” Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 46, no. 1 (1958): 53–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23. The Health News Institute (HNI) defined public relations as “the management function which evaluates public attitudes, identifies the policies and procedures of an individual or an organization with the public interest and executes a program of action to earn public understanding and acceptance.” In M. Woodward, “The Facts Behind the Story: Pharmaceutical Public Relations,” Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 46, no. 1 (1958): 53–59. The assistant executive director of the HNI described his job as being to “present a friendly and true picture” of a “high type industry and a high type profession” (p. 55). When faced with someone “a little hot under the collar about a problem,” he said, his firm “transpose[s] that problem so that it doesn't sound quite as bad or look quite as bad … by the time it gets to the other party or parties concerned, it isn't a problem anymore” (p. 56). “The press,” he noted, “is becoming more and more cooperative with us all the time” (p. 58). This activity served multiple audiences: in addition to addressing the special concerns of physicians and pharmacists, and of consumers of prescription and nonprescription pharmacy products, it also served as an arena for the industry to lobby against perceived political threats. As Mickey Smith explained in his 1968 textbook of pharmaceutical marketing, public relations occupied a distinct sphere from product promotion, “much involved with ‘image’ creation and in the drug industry, it must be admitted, most of these activities have been defensive in nature—aimed at combating bad publicity or answering the charges of a Congressional Investigation.” See M. C. Smith, Pharmaceutical Marketing (Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger, 1968), 315.

- 24. Diphenhydramine was synthesized in 1943 by George Rieveschl, a lecturer at the University of Cincinnati and a researcher with Parke, Davis & Company who would eventually become vice president for commercial development at Parke, Davis; the drug was launched under the brand name Benadryl in 1946 as the first popular oral antihistamine and remained under patent until 1964. See also W. Sneader, Drug Prototypes and Their Exploitation (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1996), 654.

- 25. Time magazine, March 15, 1963, cited in US Senate, Committee on Government Operations, Subcommittee on Reorganization and International Organizations, Interagency Coordination in Drug Research and Regulation (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1964), 1275–1279.

- 26. The Relaxed Wife, 1957, film sponsored by Roerig (J. B.) & Co, a division of Charles Pfizer & Co Inc, available at http://www.archive.org/details/RelaxedW1957 (accessed August 18, 2009)

- 27. “Tranquil Pills Stir Up Doctors,” Business Week, June 18, 1958, 28–30. See also D. Herzberg, Happy Pills; Andrea Tone, Age of Anxiety: A History of America's Turbulent Affair With Tranquilizers (New York: Basic Books, 2008)

- 28. T. Whiteside, “Getting There First With Tranquility; Don't-Give-a-Damn Pills,” Time, February 27, 1956, 98; “Pills vs Worry—How Goes the Frantic Quest for Calm in Frantic Lives?” Newsweek,May 21, 1956, 68–70; “Happiness by Prescription,” Time, March 11, 1957, 59. See also Herzberg, Happy Pills; Tone, Age of Anxiety.

- 29. “New Way to Calm a Cat,” Life, April 18, 1960, 93–95; “Tranquil but Alert,” Time, March 7, 1960, 47. See also Herzberg, Happy Pills.

- 30. “Techniques Used by MPIB for non-Paid-Advertising Promotion of Drug Products in the Press and on Radio and Television,” Senate Anti-Trust and Monopoly, Drugs (hereafter cited as SATMD), Accession 71A 5170, Box 6, Record Group 46, National Archives Building, Washington, DC. For examples from the National Archives, see Tranquilizer Drugs—An Identification (New York: Health News Institute, January 15, 1960), SATMD Box 6; radio interview with William Apple, the executive secretary of the American Pharmaceutical Association, and Francis Brown, president of Schering Corporation, on American Forum of the Air, Westinghouse Broadcasting Company, February 1, 1960, SATMD Box 19.

- 31.“Techniques Used by MPIB.”

- 32. Ibid.

- 33. D. Cooley, “The New Nerve Pills and Your Health,” Cosmopolitan, January 1956, 72. See also, for example, “Pills for the Mind,” Time, June 1, 1956, 54; D. Cooley, “The New Drugs That Make You Feel Better,” Cosmopolitan, September 1956, 24–27.

- 34. “Thumbnail Sketches of Writers and Others Whom MPIB Paid for Preparing Backgrounders, Brochures, Technical Memoranda, etc.,” SATMD box 5. See also Herzberg, Happy Pills. This paragraph and the one that follows have been adapted from D. Herzberg, “Will Wonder Drugs Never Cease!”: A Prehistory of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising,” Pharmacy in History 51, no. 2 (2009): 51. [PubMed]

- 35. L. Galton, “Aureomycin: It Fights Germs Penicillin Won't,” Better Homes and Gardens, April 1949, 10–12, 307; L. Galton, “Good News for Hay Fever and Asthma Victims,” Better Homes and Gardens, July 1957, 26; L. Galton, “The Amazing Drug That Helps High Blood Pressure,” Pageant, April 1958, 96–99.

- 36. L. Galton, “A New Drug Brings Relief for the Tense and Anxious,” Cosmopolitan, August 1955, 82–83.

- 37.D. Cooley, “Will Wonder Drugs Never Cease!” Better Homes and Gardens, March 1955, 34, 37–38, 222; D. Cooley, “New Victories Predicted for Medicine!” Better Homes and Gardens, September 1955, 18; D. Cooley, “New Drug That Awakens Energies!” Better Homes and Gardens, October 1957, 18; “Thumbnail Sketches of Writers and Others.”

- 38. D. Cooley, “The New Nerve Pills and Your Health,” Cosmopolitan, January 1956, 68–75.

- 39. Public Law 82-215, 65 stat 648, as quoted in J. Donohue, “A History of Drug Advertising,” 667; H. Marks, “Revisiting ‘The Origins of Compulsory Drug Prescriptions,’ ” American Journal of Public Health 85, no.1 (1995): 109–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40. Palumbo and Mullins, “Development of Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Advertising Regulation,” 428. [PubMed]

- 41.“The Detail Man and the Law: Oral Presentations to MDs Can Make Company Liable Under FDA Res; Sterling Lawyer Spells Do's and Don'ts to the Bar,” F-D-C Reports (February 8, 1965): 20–21; see also Podolsky and Greene, “Pharmaceutical Promotion and Physician Education.”

- 42. Monopoly. Competitive Problems in the Drug Industry, Part 125 (Washington, DC: US Senate Select Committee on Small Business, 1976)

- 43. E. S. Watkins, “ ‘Doctor, Are You Trying To Kill Me?’: Ambivalence About the Patient Package Insert for Estrogen,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 76, no. 1 (2002): 84–104. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Pines, “History and Perspective on Direct-to-Consumer Advertising.”

- 45. L. A. Morris and L. G. Millstein, “Drug Advertising to Consumers: Effects of Formats for Magazine and Television Advertisements,” Food and Drug Law Journal 497 (1984): 497–503.

- 46. L. A. Morris, D. Brinberg, R. Klimberg, C. Rivers, and L. G. Millstein, “The Attitudes of Consumers Toward Direct Advertising of Prescription Drugs,” Public Health Reports 101 (1986): 82–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47. L. R. Bradley and J. M. Zito, “Direct to Consumer Prescription Drug Advertising,” Medical Care 35, no. 1 (1997): 86–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48. Palumbo and Mullins, “Development of Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Advertising Regulation,” 423. [PubMed]

- 49. K. R. Feather to J. P Aterno, Pfizer Inc, July 13, 1982, as cited in Pines, “History and Perspective on Direct-to-Consumer Advertising,” 495.

- 50. Ibid, 495.

- 51. For example, see L. M. Schwartz, S. Woloshin, and H. G. Welch, “Communicating Drug Benefits and Harms With a Drug Facts Box: Two Randomized Trials,” Annals of Internal Medicine 150, no. 8 (2009): 563–564; J. Avorn and W. H. Shrank, “Communicating Drug Benefits and Risks Effectively: There Must Be a Better Way,” Annals of Internal Medicine 150, no. 8 (2009): 563–564.

- 52. The FDA budget for fiscal year 2007 was $1.95 billion. Food and Drug Administration, “Performance Budget Overview 2007, FDA FY 2005-1007,” available at http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/ReportsManualsForms/Reports/BudgetReports/2007FDABudgetSummary/ucm121045.htm (accessed October 28, 2009)