Abstract

Background

Many patients with degenerative joint disease of the hip have substantial degeneration of the lumbar spine. These patients may have back and lower extremity pain develop after THA and it may be difficult to determine whether the source of the pain is the hip or spine.

Questions/purposes

We therefore: (1) identified the incidence/prevalence of pain in the lower back in a group of patients with end-stage arthritis of the hip undergoing THA; (2) described the natural history of low back pain in this cohort undergoing THA; and (3) determined factors that were predictive of persistent low back pain after THA.

Methods

We administered a detailed questionnaire and a diagram of the human body on which the patients could draw the site of their pain, to 344 patients preoperatively, at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 1-year after THA. Before the THA, 170 patients (49.4%) reported pain localized to the lower lumbar region, whereas 174 patients did not have low back pain.

Results

Low back pain was variable in location. Postoperatively, the low back pain resolved in 113 (66.4%) of the 170 patients. Thirty-seven of the remaining 57 patients had known spine disorders. Thirty-five of the 174 patients (20%) without prior low back pain had low back pain develop within 1 year postoperatively. The low back pain improved in 17 of these 35 patients; 12 of the remaining 18 patients had preexistent spine disorders. Pain radiating below the knee was associated most closely with preexisting spine disorders.

Conclusions

Hip and spine arthritis often coexist. Most patients who presented with hip arthritis and lower lumbar pain experienced resolution or improvement of their pain after THA.

Level of Evidence

Level II, prognostic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

THA effectively relieves pain and restores function in patients with advanced degenerative arthritis of the hip [7, 14, 20, 22]. Persistent pain after THA, however, is not infrequent and can be a source of patient dissatisfaction [4, 15, 19]. The etiology of persistent pain after THA is multifactorial and may relate to hip-related problems such as infection, component loosening, and periprosthetic fracture [4, 12, 19, 21, 23]. However, there is a group of patients in whom the exact source of presumed “hip” pain (pain in the groin, trochanteric area, thigh and knee) cannot be identified [4, 15, 19]. The presence of a coexistent spine disorder is one possible reason for the continued pain in these locations after THA [1, 2, 5, 9, 10, 18].

Many factors may explain why persistent pain in the hip or lumbar region after THA could relate to degenerative disease of the spine. Hip and spine arthritis in the aged patient population is part of the same degenerative process and often coexist. As a result, it is possible that persistent hip or low back pain in some patients with hip arthritis may relate to underlying spinal abnormalities. Because of the high prevalence of low back pain in the population, reportedly as much as 73% [6], investigation of every patient with symptomatic hip arthritis for possible coexistent spine disorders would be counterproductive and costly. However, such a workup may be appropriate for patients with preoperative symptoms suggesting a spinal cause for their hip pain. Preoperative identification of factors associated with hip pain arising from the lumbar spine would aid the orthopaedic surgeon by identifying the subgroup of patients with hip arthritis whose preoperative hip pain may be, in part, the result of an unrecognized spinal disorder and who might not experience full relief of pain with an arthroplasty.

Our study was designed with three main objectives: (1) to identify the incidence/prevalence of low back pain in a group of patients with end-stage arthritis of the hip undergoing THA; (2) to describe the natural history of low back pain in this consecutive cohort undergoing THA; and (3) to identify potential predictive factors for persistent low back pain after THA.

Patients and Methods

We prospectively recruited subjects from a consecutive group of patients undergoing THA between 2004 and 2005 at our institution. Of 390 eligible patients, 344 patients agreed to participate in the study. Forty-eight patients declined to participate because they did not want to spend time filling out the questionnaire. The mean age of the patients was 64.5 years (range, 32.8–87.1 years). There were 165 men and 179 women in the cohort with a mean body mass index of 28.1 Kg/m2 (range, 17–45.24 Kg/m2). All patients reported pain in the hip area and had a radiographically confirmed diagnosis of arthritis. The site of the pain was the groin in 301 patients (87.6%), buttock in 115 patients (56.1%), anterior thigh in 67 patients (19.5%), and lateral hip (trochanteric region) in 34 patients (9.9%). Two hundred eighty-six patients (83.1%) had pain in more than one region. The underlying diagnosis for THA was osteoarthritis in 326 patients (94.7%), displaced femoral neck fracture in nine patients (2.6%), avascular necrosis in seven patients (2.1%), and developmental dysplasia of the hip in two patients (0.6%). The demographic factors between patients with low back pain and those without low back pain were similar for age (p = 0.67), gender (p = 0.09), and body mass index (p = 0.27) (Table 1). The preoperative limb-length discrepancy at 6.1 mm for patients without low back pain was similar to the discrepancy of 6.8 mm for patients with low back pain (p = 0.54). The Harris hip scores also were similar preoperatively (Table 2). We obtained Institutional Review Board approval before initiation of the study.

Table 1.

Details of the patients

| Parameter | Patients without back pain before and after THA (n = 139) | Patients with back pain before or after THA (n = 205) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 67.3 | 62.7 |

| Gender (male/female) | 78/61 | 87/118 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.65 | 28.4 |

| Site of pain | ||

| Groin | 120 (86.3%) | 181 (88.3%) |

| Lateral hip | 12 (8.6%) | 22 (10.7%) |

| Thigh | 17 (12.3%) | 50 (24.4%) |

| Lumbar region | 0 | 167 (81.5%) |

| Pain radiation below knee | 2 (1.5%) | 32 (15.6%) |

| Contralateral buttock | 18* (12.9%) | 38† (18.5%) |

| Spine disorder | ||

| Recognized preoperatively | N/A | 119 |

| Identified postoperatively | N/A | 49 |

* Known contralateral hip disorder; †13 patients with known moderate to severe contralateral hip disorders; N/A = Not applicable.

Table 2.

Comparative data for measured preoperative outcome parameters

| Parameter | Patients without back pain before and after THA (n = 174) | Patients with back pain before or after THA (n = 170) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LASA (energy level) | 5.1 | 4.2 | > 0.05 |

| LASA (daily activity) | 5.2 | 3.9 | |

| LASA (quality of life) | 5.8 | 5.3 | |

| Harris hip score | 50.2 | 47.6 | |

| SF-36 (physical health) | 42.8 | 39.9 | |

| SF-36 (mental health) | 58.5 | 51.2 |

LASA = Linear Analogue Scale Assessment.

We collected data at four times: preoperatively, at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year after THA. No patients were lost to followup. At each visit various functional instruments were completed which included a SF-36 [24], Harris hip score [11], the Linear Analogue Self Assessment (LASA) [17], and a specific questionnaire asking about the presence of low back pain and details of such pain, if present. We asked the patients with low back pain to indicate on a diagram of the human body, the location of the pain (ie, low back versus buttock versus thigh versus below-knee pain), and to grade the intensity of the pain using the visual analog scale [17]. The findings of additional examinations after THA were recorded in detail. We assessed the limb length using the AP standing radiographs of the pelvis preoperatively and postoperatively.

We used Student’s t-test to determine differences in preoperative and postoperative functional scores (Harris hip score, SF-36, and LASA scores) in patients without and with postoperative low back/hip pain. We used the chi square test to compare differences in pain radiating below the knee in patients with and without postoperative low back/hip pain). The results were statistically analyzed using the SPSS (Version 13; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Before THA, 170 patients (49%) reported pain localized to the lower lumbar region whereas 174 patients did not have low back pain.

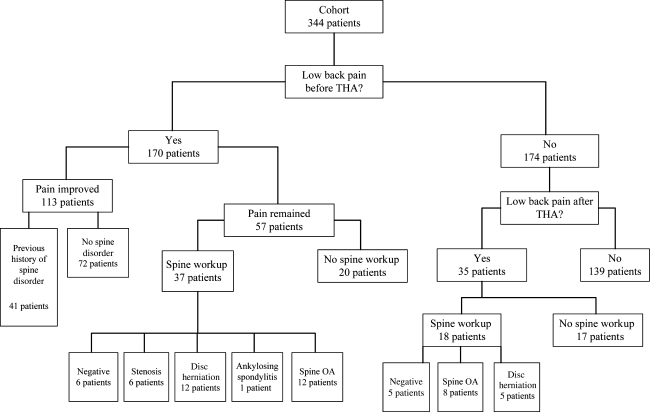

Of the 170 patients (83%) with low back pain before THA, 113 (66%) experienced complete resolution of the low back pain despite the fact that 41 of these 113 patients had undergone a preoperative spine workup, which revealed lumbar degenerative disease in 26 (without substantial spinal stenosis), disc herniation in 12, and ankylosing spondylitis in three (Fig. 1). Another 34 patients who had a negative preoperative spine workup also experienced complete resolution of their preoperative low back pain.

Fig. 1.

A flow chart shows the progress and natural history of low back pain in the cohort. The actual number of patients in each category is shown.

Low back pain persisted in 57 of 170 patients (34%). Thirty-seven of these 57 patients had a known (14 patients) or suspected (23 patients) diagnosis of a spine disorder for which they were to undergo examination by a spine specialist after the THA. The results of the spine workups in the 37 patients were negative for six and revealed lumbar degeneration in 12, disc herniation in 12, spinal stenosis in six, and ankylosing spondylitis in one. Of the other 20 patients, who either refused to receive additional workup or considered their pain tolerable, pain improved in 15 and persisted in five. At 1 year followup, low back pain remained the same in 26 of the 37 patients and became worse in the remaining five. Low back pain developed after THA in 35 patients. The low back pain resolved in 17 of these 35 patients without any intervention. The remaining 18 patients underwent a spine workup that was negative for five and revealed lumbar disc degeneration in eight and a herniated disc in five.

We observed improvement in the mean Harris hip score [11], SF-36 [24], and the LASA [17]. The patients who did not have low back pain after THA (139 patients) had higher mean Harris hip scores (85.6 versus 76.4; p = 0.01) and SF-36 physical (79.6 versus 68; p = 0.02) and mental (84.5 versus 75.9; p = 0.01) scores than patients who experienced low back pain after THA. Postoperative LASA scores also were higher for the patients without postoperative low back pain (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparative data for measured postoperative outcome parameters

| Parameter | Patients without back pain before and after THA (n = 139) | Patients with back pain either before or after THA (n = 205) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LASA (energy level) | 7.8 | 6.6 | 0.01 |

| LASA (daily activity) | 8.5 | 7.7 | > 0.05 |

| LASA (quality of life) | 8.3 | 7.6 | > 0.05 |

| Harris hip score | 85.6 | 76.4 | 0.01 |

| SF-36 (physical health) | 79.6 | 68 | 0.02 |

| SF-36 (mental health) | 84.5 | 75.9 | 0.01 |

LASA= Linear Analogue Scale Assessment.

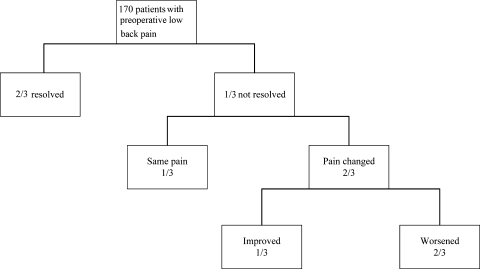

Low back pain was present in half the patients undergoing THA. Half of those with low back pain had known spine disorders. Low back pain improved in two-thirds of patients, including many with known spine disorders. Of the one-third with persistent pain, a spine disorder may be implicated for pain in two-thirds of them. One-tenth of patients without prior low back pain may have low back pain develop after the THA. Half of these patients will have persistent pain that can be attributed to a previously unrecognized spine disorder (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The prevalence of low back/hip pain in the study population is shown in the flow chart. Low back pain improved in two-thirds of patients, including many with known spine disorders. One-tenth of patients without previous low back pain may have low back pain develop after the THA that can be attributed to a previously unrecognized spine disorder.

Among the cohort of patients with low back pain either before and/or after the THA, 32 of 205 reported low back pain radiating below the ipsilateral knee. This was higher (p = 0.0001) than among the cohort without low back pain (below the ipsilateral knee in two of 139 patients) (Table 1).

Discussion

Low back pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal conditions with an incidence of 73% in the general population [6]. Hip arthritis is a much less common condition by comparison, afflicting only 3.2% of the population older than 55 years, which is disabling enough to warrant joint arthroplasty in some patients [8]. A small number of patients undergoing THA do have persistent pain leading to patient dissatisfaction. One potential source of postoperative hip pain is degenerative disease of the lumbar spine, which poses a challenge to the treating orthopaedic surgeons in determining the relative contribution of each condition to hip pain. However, the literature does not clearly give an indication regarding the frequency of relief of pain in the lower back after THA. We therefore established three main objectives: (1) to identify the incidence/prevalence of low back pain in a group of patients with end-stage arthritis of the hip undergoing THA; (2) to describe the natural history of low back pain in this consecutive cohort undergoing THA; and (3) to identify potential predictive factors for persistent low back pain after THA.

This study has some limitations. First, some patients who had low back pain before and/or after THA did not undergo full evaluation. Had they been evaluated we might have identified the nature of the disorder causing low back pain. Second, we could not evaluate the potential role of limb-length discrepancy, if any, on persistent low back pain, as full-length radiographs of the lower limb were not obtained in these patients. Finally, we outlined the natural history of low back pain after THA at a relatively short term and it is possible that with longer-term followup the findings may differ.

One study of 97 patients attempted to determine which signs and symptoms best predict the primary source of pain in patients with hip and spine disorders [3]. The presence of a limp, groin pain, or limited internal rotation of the hip implicated hip arthritis as the primary cause of pain. However, it is unclear what characteristics of back pain, if any, may be a predictor of poor outcome after THA. Offierski and MacNab described hip spine syndrome in 1983 [16]. They categorized this syndrome into four groups. The simple hip spine syndrome was defined along with pathologic changes in the hip and spine with a clear source of pain and disability. If the spine symptoms were aggravated by the hip deformity, it was called secondary hip spine syndrome. If the spine and hip were symptomatic and there was no clear source for the pain and disability, it was called complex hip spine syndrome. The fourth category was misdiagnosed syndrome in which the source of pain was not diagnosed correctly. They considered postural changes in the low back in the form of hyperlordosis, sacral inclination, and secondary foraminal stenosis at L4–L5 as possible causes of aggravated symptoms.

One of the objectives of our study was to determine the group of patients who may have persistent pain after THA (Fig. 2). We found that three groups of patients may have persistent pain after THA. One group, which in the current study constituted the majority of patients with persistent low back pain, was those with previous low back pain who continued to report disabling back pain after THA. The second group was patients without low back pain who have low back pain develop after THA. Often, these individuals had underlying spinal disorders, which may have been mildly symptomatic but the patients were overwhelmed by the pain from their degenerative hip arthritis. Nevertheless, these patients often are dissatisfied with the outcome of THA and may feel anger toward the treating orthopaedic surgeons for missing the cause of pain in the first instance. The final group of patients with persistent hip pain after THA includes those with hip pain secondary to a hip problem such as fractures, lack of osseointegration, or infection.

Various factors may explain why patients can have back pain develop after THA. The use of regional anesthesia, which greater than 95% of the patients in this cohort received, is associated with exacerbation of low back pain. Positioning of the patient during administration of the regional anesthesia and injection of a volume of anesthetic agents into a spinal canal that often is stenotic may contribute to this problem. In addition, alteration of a patient’s gait pattern after THA and improved ability to ambulate with preexisting spine degeneration could cause previously asymptomatic lumbar stenosis to produce claudication symptoms. However, low back pain is likely to resolve in the majority of these patients with implementation of nonoperative modalities.

This prospective study of a relatively large patient population may serve as a reference point for discussions between patients with end-stage arthritis of the hip and their treating orthopaedic surgeons. Results of this study also suggest it may be helpful for the patient to map out the site of pain on a human body diagram. The use of pain charts to map out the site of pain is useful [13] because there is considerable variation among patients in their definition of anatomic sites. Back pain and hip pain often have different meanings to different patients. It also should spur the treating physician to seek out an unrecognized spine disorder in patients undergoing THA who have preoperative low back, buttock, and/or lower leg pain. Hopefully, this will result in patients with concomitant spine conditions who are better-informed before undergoing THA. Our data suggest the coexistence of a spinal disorder is not a contraindication to performing THA: all the patients, including those with a known spinal disorder, benefited from THA and experienced relief of their preoperative low back pain.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors (JP, RHR) are consultants to Stryker Orthopaedics and their institution has received funding from Stryker Orthopaedics. The received funding was not related to this project.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved the reporting of these cases, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participating in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at the Rothman Institute of Orthopedics at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

References

- 1.Ben-Galim P, Ben-Galim T, Rand N, Haim A, Hipp J, Dekel S, Floman Y. Hip-spine syndrome: the effect of total hip replacement surgery on low back pain in severe osteoarthritis of the hip. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:2099–2102. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318145a3c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blasingame JP, Resnick D, Coutts RD, Danzig LA. Extensive spinal osteophytosis as a risk factor for heterotopic bone formation after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;161:191–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown MD, Gomez-Marin O, Brookfield KF, Li PS. Differential diagnosis of hip disease versus spine disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;419:280–284. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200402000-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown TE, Larson B, Shen F, Moskal JT. Thigh pain after cementless total hip arthroplasty: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:385–392. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200211000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buttaro M, Gonzalez Della Valle A, Piccaluga F. Psoas abscess associated with infected total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:230–234. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.28734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Cote P. The Saskatchewan health and back pain survey: the prevalence of low back pain and related disability in Saskatchewan adults. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:1860–1866. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199809010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charnley J. Arthroplasty of the hip: a new operation. Lancet. 1961;1:1129–1132. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(61)92063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fear J, Hillman M, Chamberlain MA, Tennant A. Prevalence of hip problems in the population aged 55 years and over: access to specialist care and future demand for hip arthroplasty. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36:74–76. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fogel GR, Esses SI. Hip spine syndrome: management of coexisting radiculopathy and arthritis of the lower extremity. Spine J. 2003;3:238–241. doi: 10.1016/S1529-9430(02)00453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilgil E, Tuncer T, Arman M. Cauda equina syndrome or a complication of total hip arthroplasty? J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SR, Bostrom MP. Periprosthetic fractures of the femur after total hip arthroplasty. Instr Course Lect. 2004;53:111–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mann NH, 3rd, Brown MD, Hertz DB, Enger I, Tompkins J. Initial-impression diagnosis using low-back pain patient pain drawings. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1993;18:41–53. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCoy TH, Salvati EA, Ranawat CS, Wilson PD., Jr A fifteen-year follow-up study of one hundred Charnley low-friction arthroplasties. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19:467–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikolajsen L, Brandsborg B, Lucht U, Jensen TS, Kehlet H. Chronic pain following total hip arthroplasty: a nationwide questionnaire study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:495–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Offierski CM, MacNab I. Hip-spine syndrome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1983;8:316–321. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198304000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Priestman TJ, Baum M. Evaluation of quality of life in patients receiving treatment for advanced breast cancer. Lancet. 1976;1:899–900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(76)92112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pritchett JW. Lumbar decompression to treat foot drop after hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;303:173–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robbins GM, Masri BA, Garbuz DS, Duncan CP. Evaluation of pain in patients with apparently solidly fixed total hip arthroplasty components. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:86–94. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salvati EA, Ranawat CS, Wilson PD, Jr, McCoy TH. A long term study of Charnley total hip replacements. Arch Putti Chir Organi Mov. 1989;37:37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmalzried TP. The infected hip: telltale signs and treatment options. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Surin VV, Sundholm K. Survival of patients and prostheses after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;177:148–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flandern GJ. Periprosthetic fractures in total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2005;28(9 suppl):S1089–S1095. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20050902-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]