Abstract

Motivation: Global expression patterns within cells are used for purposes ranging from the identification of disease biomarkers to basic understanding of cellular processes. Unfortunately, tissue samples used in cancer studies are usually composed of multiple cell types and the non-cancerous portions can significantly affect expression profiles. This severely limits the conclusions that can be made about the specificity of gene expression in the cell-type of interest. However, statistical analysis can be used to identify differentially expressed genes that are related to the biological question being studied.

Results: We propose a statistical approach to expression deconvolution from mixed tissue samples in which the proportion of each component cell type is unknown. Our method estimates the proportion of each component in a mixed tissue sample; this estimate can be used to provide estimates of gene expression from each component. We demonstrate our technique on xenograft samples from breast cancer research and publicly available experimental datasets found in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus repository.

Availability: R code (http://www.r-project.org/) for estimating sample proportions is freely available to non-commercial users and available at http://www.med.miami.edu/medicine/x2691.xml

Contact: jclarke@med.miami.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

In the past decade, gene expression profiling has demonstrated an amazing potential for identifying disease biomarkers and improving our understanding of cellular processes (Pittman et al., 2004; van't Veer et al., 2002; Wheelan et al., 2008). An issue not often discussed is that many biological samples contain mixtures of cell or tissue types (Wang et al., 2006); for example, cancer cells may only constitute part of a biopsy sample. The amount of each mRNA detected in a microarray experiment is influenced by the composition of the sample; observed changes in gene expression may simply reflect a change in the distribution of the cell types in the sample population (Causton et al., 2003). In breast cancer Cleator et al. (2006) noticed that the proportion of benign tissue of biopsy samples can significantly affect expression profiles, and taking into consideration this proportion can improve response prediction. Sample heterogeneity severely limits the conclusions that can be made about specificity of gene expression and may explain in part why the results of numerous gene expression experiments have failed rigorous validation (Michiels et al., 2005).

Given a heterogeneous sample there exist laboratory approaches to separate cells of distinct types. Laser capture microdissection (LCM; Fend and Raffeld, 2000) is a popular technique for isolating regions of a biological sample that are separated by distances of a few cell widths. However, the cell types of interest need to be morphologically distinct. LCM, is very time-consuming and specialized equipment, is required to obtain a sufficient quantity of biological material for profiling. If the sample of interest is in suspension, cell-sorting methods can be used to isolate cells of interest. This requires a suitable biomarker for the cell type of interest. The main drawback of cell sorting with respect to profiling is that the act of separation itself can alter gene expression (Gosink et al., 2007).

We present a method for deconvoluting expression from a heterogeneous sample into components that reflect the contributions to the observed expression attributable to each component cell or tissue type. The key component of this method is the estimation, from a mixed tissue sample, of the proportion of mRNA from a single tissue type. Estimation is based on specific logarithmic data transformations and theory from differential geometry regarding the radius of curvature (Lipschutz, 1969). We demonstrate our method on several datasets from breast cancer xenograft studies, from both proprietary sources and the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; Barrett et al., 2006).

2 APPROACH

Several approaches have been taken to the problem of expression deconvolution and each approach depends on access to different types of information, different statistical assumptions and different objectives.

If there are genes known to be expressed exclusively in one tissue type, then these genes can be used to estimate the proportion of expression coming from that tissue. For example, the program DECONVOLUTE (Lu et al., 2003) uses simulated annealing and genes expressed only during specific cell cycles to identify the proportion of cells in each cycle from an asynchronous cellular sample. These methods depend on known tissue- or cell-specific genes, and technology that can detect their expression with little or no cross-hybridization. If these conditions is not met, widely varying estimates of pA can be obtained by selecting different subsets of tissue-specific genes. Note that low specificity of microarray hybridizations has been suggested to be one of the prime measures affecting discrepancies in gene-expression profiles between different probes targeting the same region of a given transcript or between different microarray platforms (Koltai and Weingarten-Baror, 2008). We do not assume knowledge of cell- or tissue-specific genes in our method, although such knowledge may be available, particularly for samples from xenograft studies (where the tissues of interest are from different species).

Similarly, several researchers have used expression data from purified reference tissue types to determine the expression of each tissue type in heterologous samples (Lahdesmaki et al., 2005; Venet et al., 2001). For example, Wang et al. (2006) use a method similar to that of Lu et al. (2003), mentioned above, to determine the proportions of each cell type in a mixed sample. This method generates estimates by obtaining solutions to linear equations via simulated annealing. These approaches depend on having expression data from a purified reference sample for each cell or tissue type, which may not be available.

Another approach uses proportions of each sample or cell type, assessed by pathologists, to establish either tissue-specific expression or differential expression between mixed and control samples. In Stuart et al. (2004) linear regression models, regressing expression on fractional content of tumor (or stroma), were used to estimate the expected cell-type expression as the regression coefficient. A more sophisticated statistical approach was used by Ghosh (2004) to determine differential expression in the presence of mixed cell populations. In his approach, a pathologist's assessments of the proportions of each cell type were used in a hierarchical mixture model to model the data. A combination of methods of moments procedures and the expectation–minimization (EM) algorithm provided estimates of the model parameters. Although not shown in the publication, this method could be adapted to provide expression estimates specific to each cell type, as opposed to estimates of differential expression. Unfortunately, the assessment of a pathologist only provides the proportion of each cell or tissue type in the sample, and not an assessment of the amount of mRNA or protein attributable to each. It is well known that the total amount of mRNA generated by tumor cells, for example, is much higher than the amount generated by normal cells. As a result estimates of expression based on pathological assessments of tissue proportions may not be accurate.

Finally, an approach exists to use expression data from a single cell type to determine the proportion of each cell type in a heterogeneous sample (Gosink et al., 2007). This method depends on the estimation of the minimum of a proportion, a minimum that provides a good estimate in noiseless or simulated data. However, this minimum is much more difficult to estimate in noisy data, and microarray data is inherently noisy. Our research builds upon this work by providing a method for estimating this minimum that has reasonable accuracy and can be applied in situations where one or multiple heterologous samples are available.

3 METHODS

First, we will discuss the idea of estimating the proportion of a single cell or tissue type in a two-type mixed sample. We will then describe the role of data transformation in this estimation and the interest in finding the point of minimum radius of curvature. Finally, we will describe the use of the bootstrap (Efron, 1979) for obtaining a standard error for our estimate.

3.1 Proportion of tumor as a minimum ratio

The idea of estimating the proportion of one type in a two-type mixed sample comes from Gosink et al. (2007). As they describe, let A be a purified sample of one type and AB be a mixed sample, composed of tissue or cell types A and B. Let Ei(AB)(Ei(A)) be expression of gene i in Sample AB(A) for i=1,…, m. Let E(AB)={E1(AB),…, Em(AB)}. We want to estimate pA, the proportion of expression in the mixed sample (Sample AB) due to tissue type A. For a given gene i we can express Ei(AB) as

Let Ri=Rimix/pure = Ei(AB)/Ei(A). In the noiseless case,

Note that for a fixed pA this ratio is at its minimum when Ei(B) = 0, since expression is assumed to be non-negative. Hence, if Ei(A)>0,

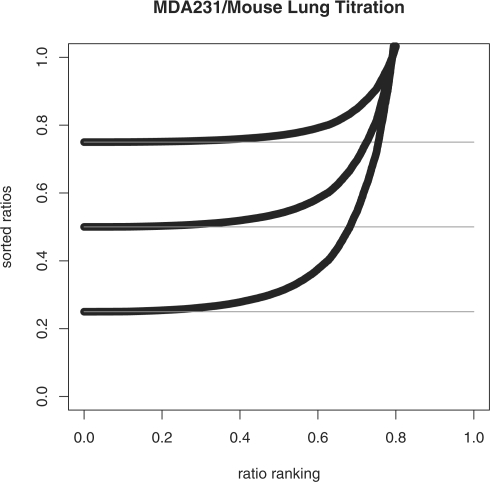

Thus, under the assumption that Ei(B)→0 for some sequence of i's, miniRi=pA. This can be seen in Figure 1 where rank-sorted ratios Ri have been plotted from ‘electronic’ simulated data at a range of proportion values pA. The ‘electronic data’ was generated by computationally combining expression values from purified samples of each composite type in these specific proportions, e.g. for pA = 0.25 the electronic data is 0.25*E(A) + 0.75*E(B) where E(A) are expression values from a purified sample of breast cancer cell mRNA and E(B) the expression values from a purified sample of normal mouse lung mRNA. Note that the values of Ri are sorted from lowest to highest.

Fig. 1.

Rank-sorted ratios (Ri) from ‘electronic’ data across values of pA

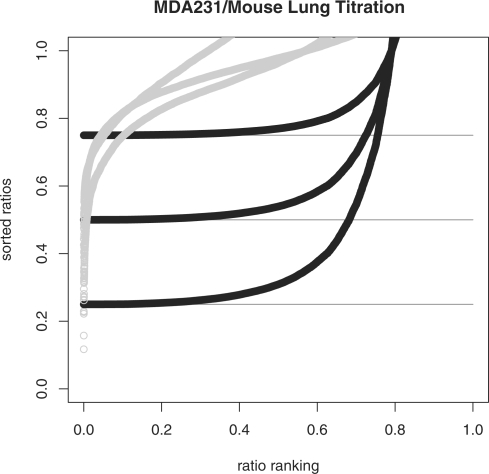

Unfortunately, the minimum ratio is an underestimate of the true proportion value pA for simulated noisy data and for observed data [as Gosink et al. (2007) establish]. For example, Figure 2 shows observed data from a titration series (pA=0.25, 0.5 and 0.75) of breast cancer cell mRNA (MDA231) and normal mouse lung mRNA. By a titration series, we mean a set of mixed samples (breast cancer and normal lung) in which each sample has a fixed proportion of each tissue/cell type. What we observe is expression data from each mixed sample in this series, so a total of three samples with proportions of breast cancer mRNA to normal mouse lung mRNA of {(0.25, 0.75),(0.5,0.5) and (0.75,0.25)}. Hence for pA = 0.25 the observed data is expression from a mixed sample (AB) composed as 0.25*A+0.75*B. The ‘electronic data’ is the same data as shown in Figure 1. The values of miniRi are very accurate estimates of pA for the ‘electronic’ data but are poor estimates of pA for the observed data. Clearly, the ability of miniRi to estimate pA is greatly affected by the noise in the data; understanding and incorporating the noise and its effect on miniRi in the estimation process is the key to finding an accurate estimate of pA.

Fig. 2.

Rank-sorted ratios (Ri) from ‘electronic’ titration data (dark) and observed titration data (light) for proportion values pA = 0.25, 0.5 and 0.75. Note the qualitatively different curves caused by noise in the observed data.

3.2 Data transformation

The noise in the observed expression data from mixed samples causes the minimum ratio to be an underestimate of the true proportion value. A transformation that increases small ratio values while shrinking larger ratio values may improve the accuracy of this estimate. To explore this proposition, we considered transforming both E(AB) and E(A) with a transformation of the form

for some α > 0 and for all i. The untransformed values of Ri have a skewed distribution with a long tail of large values (data not shown). As such the mean of the Ris is larger than the median. The above transformation, by decreasing large values and increasing small values, brings the mean and the median closer together.

We discovered that across several datasets a value for α does exist for which minitRi=minitEi(AB)/tEi(A) is an accurate estimate of pA. Unfortunately, this value for α varies with each dataset and with the value of pA, i.e. within each dataset and across datasets the value of α that provides an accurate estimate of pA is different for each value of pA. For any given dataset and value of pA we could successfully model α as a function of pA, using a function of the form −log(θ*pAγ+1)/(pA−1) for some θ, γ > 0. However, this function depends on pA, the value we are trying to estimate.

We acknowledge that the minimum value of tRi is sensitive to the noise in the data, particularly in relation to the mean or the median. Hence we decided to explore the possibility of using information from a summary statistic of tRi (e.g. mean or median) as a function of α to determine the correct value of α, and hence the value of our estimate mintRi. The mean of  as a function of α is defined as

as a function of α is defined as

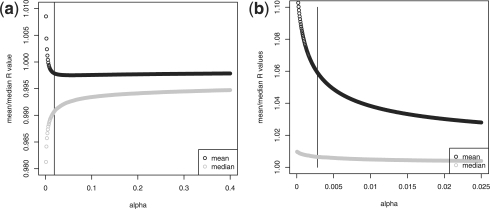

where m is the number of expression values (i.e. number of genes). The median is analogously defined. We decided to plot the mean and median of tRi for a fixed pA across a range of values of α. Example plots for two different titration series [MDA231/mouse lung at pA = 0.5 and data from MicroArray Quality Control (MAQC) project 2006 (GEO accession 5350) at pA=0.75] are shown in Figure 3. The value of α that provides the most accurate estimate of pA is marked by a vertical black line.

Fig. 3.

Values of  and md(tR(α)) as functions of α for (a) MDA231/mouse titration data at pA=0.5 and (b) MAQC human titration data at pA=0.75. The vertical line indicates the correct value of α.

and md(tR(α)) as functions of α for (a) MDA231/mouse titration data at pA=0.5 and (b) MAQC human titration data at pA=0.75. The vertical line indicates the correct value of α.

The value of α that provides the most accurate estimate of pA, in these plots and many others, is located at what one may refer to as the ‘knee’ or ‘elbow’ of the curve. This point may be familiar from principal components analysis as the point on a scree plot that indicates the number of significant principal components (Jolliffe, 2002). To calculate this point, we need a mathematical definition for the ‘elbow’ of a curve.

3.3 Minimum radius of curvature

We want to find the value of α at the ‘elbow’ of the curve defined by  as a function of α. The ‘elbow’ of a curve is the point at which the tradeoff between pulling low values up and pulling high values down (values of Ri(α)) is optimal. Here, we formalize this by choosing that point at which the radius of curvature is at its minimum. The radius of curvature ρ(s) is defined as the inverse of the vector norm of the second derivative of the curve, expressed as a function of arc length s, i.e.

as a function of α. The ‘elbow’ of a curve is the point at which the tradeoff between pulling low values up and pulling high values down (values of Ri(α)) is optimal. Here, we formalize this by choosing that point at which the radius of curvature is at its minimum. The radius of curvature ρ(s) is defined as the inverse of the vector norm of the second derivative of the curve, expressed as a function of arc length s, i.e.

| (1) |

where C is the curve of interest originally parameterized in terms of x (Lipschutz, 1969). Thus, to find the value of α of interest several steps are required. First, we need to represent the function  as a curve in the plane. Second, we must reparameterize this curve in terms of the arc length s. Third, we use the reparameterized curve to determine the value of arc length s* that minimizes the radius of curvature ρ(s). Finally, we determine the value of α that corresponds to s*.

as a curve in the plane. Second, we must reparameterize this curve in terms of the arc length s. Third, we use the reparameterized curve to determine the value of arc length s* that minimizes the radius of curvature ρ(s). Finally, we determine the value of α that corresponds to s*.

3.3.1 Radius of curvature in terms of arc length

Recall that a parameterized curve in the plane is of the form

| (2) |

where x1, x2 are the coordinate functions, e1 = (1, 0) and e2 = (0, 1) the natural basis and α the parameter of the curve. To define the radius of curvature of x(α) at a point x, we first reparameterize in terms of arc length s. The arc length parameterization is defined to be the parameterization with unit speed along the curve. This eliminates the possibility of an unnaturally high or low radius of curvature simply due to the local speed of transversal of the curve.

The arc length s of a curve is defined as

| (3) |

where ‖·‖ is the Euclidean norm. Now consider a function f(α) and observe that its graph (α, f(α)) is a geometric curve in the plane. Thus, as in Equation (2), we can write

Hence

So the arc length parameter [Equation (3)] is given in terms of α by

Since the parameterization is in terms of unit speed, it is invertible, so we can write α=α(s) as well. Thus, s′=s(α′) and s′′=s(α′′). The radius of curvature of a geometric curve C as stated in Equation (1) can now be defined as

for the curve  . We will argue that choosing α to minimize ρ(s) leads to a good estimate of pA over [α′, α′′].

. We will argue that choosing α to minimize ρ(s) leads to a good estimate of pA over [α′, α′′].

3.3.2 Implementation

Given the definitions in the last subsection, it remains to obtain the arc length parameterization for the curve  and find the value of α that corresponds to s*. Replacing f(α) with

and find the value of α that corresponds to s*. Replacing f(α) with  we have the following:

we have the following:

Partition the interval [α′, α′′] uniformly by setting

Then,

where we approximate  as

as

This will yield a one-to-one relationship between α and s, hence a one-to-one relationship between s and  . Once we have this we can find the value of s that minimizes the radius of curvature ρ(α(s)), i.e. maximizes ‖f′′(x(α(s)))‖ over s∈[s′, s′′].

. Once we have this we can find the value of s that minimizes the radius of curvature ρ(α(s)), i.e. maximizes ‖f′′(x(α(s)))‖ over s∈[s′, s′′].

3.3.3 Determining s* and α

To find the maximum of

we find the value of s, s*, which maximizes the absolute value of the second derivative with respect to s using centered difference approximations (Ames, 1977). Approximate  by

by

Using this approximation, we calculate  over a range of values [s′, s′′] and determine the value s* that minimizes

over a range of values [s′, s′′] and determine the value s* that minimizes  .

.

Note that this method for finding s* (and subsequently α) only works if the two axes of the plot for  , are similarly scaled. If the two scales are not equal, they must be equalized prior to calculating s* by rescaling one axis to be the same length as the other. For example, to rescale the axis for

, are similarly scaled. If the two scales are not equal, they must be equalized prior to calculating s* by rescaling one axis to be the same length as the other. For example, to rescale the axis for  we would use values of the following in place of

we would use values of the following in place of

That is, the range of the function  is the same as the range of the parameter α. This ‘scaling’, like the arc length parameterization, seems necessary to prevent arbitrary choices from dominating the solution.

is the same as the range of the parameter α. This ‘scaling’, like the arc length parameterization, seems necessary to prevent arbitrary choices from dominating the solution.

One key task is choosing k large enough so that the approximation of the second derivative with respect to second differences is accurate over the range [α0, αj]. We found that k of several thousand worked well in the examples in Section 4.

3.4 Bootstrap estimates of standard error

We used a simple bootstrap resampling procedure (Efron, 1979) to generate standard errors for our estimate of pA. For a given dataset of n observations and m genes, we draw T bootstrap samples; each sample contains expression values of m′ genes drawn at random with replacement where m′ ≈ 0.6*m (so a total of nm′ values). From each sample j, j = 1,…, T, we calculate the mean of  across values of α in a given range. We then determine the value of α that corresponds to the minimum radius of curvature (s*) of

across values of α in a given range. We then determine the value of α that corresponds to the minimum radius of curvature (s*) of  , plotted as a function of α (as described in Section 3.3). This value of α is used to generate tRi for the genes in sample j and determine its minimum, i.e. our estimate of pA. The result of our bootstrap procedure is T estimates of pA,

, plotted as a function of α (as described in Section 3.3). This value of α is used to generate tRi for the genes in sample j and determine its minimum, i.e. our estimate of pA. The result of our bootstrap procedure is T estimates of pA,  , one for each sample. The SD of these estimates is taken as the standard error of our estimate of pA, and a (1 − τ) confidence interval for our estimate is calculated as

, one for each sample. The SD of these estimates is taken as the standard error of our estimate of pA, and a (1 − τ) confidence interval for our estimate is calculated as  where

where  and

and  are the (τ/2)th and (1−(τ/2))th percentiles of our 100 estimates of pA.Stated as psuedo-code for clarity, our procedure is as follows:

are the (τ/2)th and (1−(τ/2))th percentiles of our 100 estimates of pA.Stated as psuedo-code for clarity, our procedure is as follows:

Generate T bootstrap samples where each sample contains nm′ expression values, i.e. expression values for m′ genes from each sample. The m′ genes, m′≈0.6*m, are selected at random and with replacement.

For each sample, calculate the values of tRi, i=1,…, m′, for a range of values of α.

For each sample, calculate the values on the curve

for a range of values of α, using the result of step 2.

for a range of values of α, using the result of step 2.For each sample, use the curve calculated in Step 3 to determine the value of α that corresponds to the minimum radius of curvature s* (as described in Section 3.3). Label this value as αj for each sample j, j=1,…, T.

For each sample j, use the values of tRi that correspond to αj (as calculated in Step 2) and determine its minimum, i.e. our estimate of pA. This yields

.

.Calculate the standard error of our estimate (as the SD of

) and a (1 − τ) confidence interval (as

) and a (1 − τ) confidence interval (as  where

where  and

and  are the (τ/2)th and (1−(τ/2))th percentiles of our 100 estimates of pA).

are the (τ/2)th and (1−(τ/2))th percentiles of our 100 estimates of pA).

As a sort of stability analysis, we chose a range of values for T in our computations below to see whether there was any obvious relationship between the size of T and the likelihood that a bootstrapped confidence interval contained the true value. The results in Table 2 suggest that the size of T and the accuracy of the bootstrap intervals is slight at most.

Table 2.

Bootstrap estimates of pA

| Source | Norm | nb | Prop | Est | SE | 90% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UM-MDA231 | Qspline | 39 | 0.75 | 0.788 | 0.023 | (0.746, 0.819) |

| 37 | 0.50 | 0.529 | 0.065 | (0.396, 0.604) | ||

| 10 | 0.25 | 0.304 | 0.108 | (0.180, 0.437) | ||

| UM-MCF7 | Quantile | 100 | 0.75 | 0.722 | 0.086 | (0.596, 0.863) |

| 0.50 | 0.448 | 0.057 | (0.375, 0.553) | |||

| 0.25 | 0.286 | 0.031 | (0.265, 0.336) | |||

| MAQC-ILM | Cubic | 40 | 0.75 | 0.776 | 0.041 | (0.710, 0.842) |

| 55 | 0.25 | 0.303 | 0.021 | (0.275, 0.335) | ||

| MAQC-AFFX | MAS5 | 14 | 0.75 | 0.763 | 0.040 | (0.688, 0.805) |

| 68 | 0.25 | 0.270 | 0.027 | (0.232, 0.317) | ||

| BIIB500 | MAS5 | 100 | 0.80 | 0.761 | 0.031 | (0.697, 0.800) |

| 0.60 | 0.576 | 0.048 | (0.508, 0.659) | |||

| 0.40 | 0.493 | 0.053 | (0.388, 0.567) | |||

| 0.20 | 0.208 | 0.101 | (0.092, 0.381) | |||

| BIIB100 | MAS5 | 100 | 0.80 | 0.752 | 0.021 | (0.722, 0.789) |

| 0.60 | 0.518 | 0.050 | (0.437, 0.593) | |||

| 0.40 | 0.443 | 0.050 | (0.365, 0.527) | |||

| 0.20 | 0.190 | 0.093 | (0.067, 0.347) |

Source, data source; Norm, normalization; nb, number of bootstrap samples; Prop, true value of pA; Est, bootstrap point estimate, SE, bootstrap standard error; 90% CI , 90% bootstrap confidence interval. Bold values denotes cases where the true pA is not in the interval.

4 RESULTS

We implemented our procedure for estimating pA in several gene expression datasets, both proprietary and public, in which expression data was generated from samples composed of two tissue/cell types. Some of the samples consist of different cell types from the same organism, while other samples are a mix of cell types from different organisms. The proportion of each component type is known, as the data come from titration series; we use these values to assess the accuracy of our estimates.

4.1 Data

Our data consists of six datasets obtained either from the University of Miami School of Medicine (UMiami) or the NCBI GEO (Barrett et al., 2006). The UMiami datasets were created as a titration series of RNA from breast cancer cells (either MDA231 or MCF7) and normal mouse lung cells. The expression platform is Illumina Human WG-6 version 2 (MCF7) or version 3 (MDA231) (Illumina Inc., 2009); chips were processed at two different laboratories. The data from GEO includes titration series of Universal Human Reference RNA and Human Brain RNA from the MAQC study (MAQC Consortium, 2006). We selected data processed at two different laboratories and on two different platforms, either Human-6 BeadChip 48K version 1 (Illumina Inc., 2009) or HG-U133 Plus 2.0 GeneChip (Affymetrix Inc., 2009). Two other datasets from GEO were also included in our studies; these data include two titration series of mouse T and B cells (Shearstone et al., 2006). These sets were processed on the Mouse 430A version 2 GeneChip platform (Affymetrix Inc., 2009). The details of each dataset are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Available datasets

| Source | Type | Platform | Proportion | n | Norm | GEO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UMiami | MDA231 | ILM | 0:100:25 | 3 | None | |

| Mouse lung | cubic | |||||

| qspline | ||||||

| UMiami | MCF7 | ILM | 0:100:25 | 1 | None | |

| Mouse lung | quantile | |||||

| qspline | ||||||

| MAQC Site 3 | Univ human | ILM | 100/75/25/0 | 5 | Cubic | GSE5350 |

| brain | ||||||

| MAQC Site 1 | Univ human | AFFX | 100/75/25/0 | 5 | MAS5 | GSE5350 |

| brain | ||||||

| BIIB 500 | Mouse T cells | AFFX | 0:100:20 | 3 | MAS5 | GSE5130 |

| Mouse B cells | ||||||

| BIIB 100 | Mouse T cells | AFFX | 0:100:20 | 1 | MAS5 | GSE5130 |

| Mouse B cells |

Source, data source; type, tissue/cell types; platform, expression platform; proportion, pA; n = number of samples at each proportion; Norm, normalization; GEO, GEO accession number. See text for further details.

The method of normalization of gene expression data can impact substantially which probes are identified as detected and which probes are identified as differentially expressed between conditions (Dunning et al., 2008b; Johnstone et al., 2008). For this reason, we implemented several normalization methods on our proprietary datasets, while using the available normalized data for the publicly available datasets. The normalization methods for the Illumina data include quantile normalization and qspline normalization as implemented in the R package beadarray (Dunning et al., 2008a; R Development Core Team, 2009) and cubic normalization as implemented in the Illumina BeadStudio software (Illumina Inc., 2009). After normalization, only those genes with a detection P-value <0.01 in all samples (Illumina Inc., 2009) or considered present in all samples according to the Affymetrix MAS5 algorithm (Affymetrix Inc., 2009) were included in further analyses (i.e. bootstrap estimation of pA by the procedure described in Section 3.4).

4.2 Accuracy of estimation

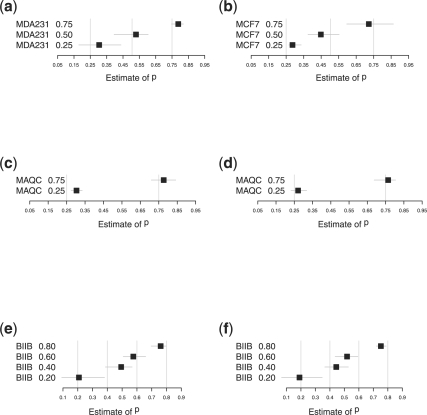

Select results of our bootstrap estimation procedure for each dataset are shown in Figure 4. For the UMiami datasets, we chose to display results for only one normalization method for brevity.

Fig. 4.

Bootstrap estimates of pA with 90% confidence intervals. Boxes indicate the point estimates of pA; light grey vertical lines indicate the true values of pA. (a) MDA231 qspline-normalized data; (b) MCF7 quantile-normalized data; (c) MAQC ILM cubic spline-normalized data; (d) MAQC Affymetrix MAS5 data; (e) BIIB 500 Affymetrix MAS5 data; and (f) BIIB 100 Affymetrix MAS5 data.

In ∼90% of cases, our point estimate is within 5% of the true proportion; in ∼80% of cases, the 90% bootstrap confidence interval for our estimate contains the true value of pA. We note that our method found the BIIB 100 dataset to be the most challenging. This is no surprise as this titration series was designed with very low levels of mRNA, as a challenge to the procedure used for RNA amplification prior to running the expression assay (Shearstone et al., 2006). In other words, this data was generated from a very small amount of biological material so the estimation of the proportion of the biological components is very challenging.

There is evidence in Figure 4 of an interaction between the normalization procedure and the accuracy of our estimation method. For example, we tend to overestimate pA when the data is qspline normalized, as with the UMiami MDA231 data, but we tend to underestimate pA when the data is quantile normalized. We note that this relationship could also be a consequence of other experimental variables, such as the expression platform or the specific laboratory in which the data were generated. Further, datasets and analysis are required to determine which factors (e.g. normalization, platform and laboratory) have significant effects on the accuracy of our procedure.

In addition, the stated confidence level of the confidence intervals (90%) is predicated on the validity of the underlying model (Leeb, 2009; Shen et al., 2004). Because our underlying model has some level of uncertainty, the stated level of confidence is an overestimate of the actual level of confidence. In other words, model uncertainty tells us that a true 90% confidence interval is larger than the stated 90% confidence interval. In light of this the accuracy of our method is most likely better than the results in Table 2 would suggest.

An accurate estimate of pA can be used to generate estimates of expression specific to each tissue/cell type. Given expression from a mixed sample AB and an estimate of pA we can estimate E(A) and E(B) as

As we observe E(A), we can compare  with the observed E(A) to assess the quality of our estimate. Whether the error in using

with the observed E(A) to assess the quality of our estimate. Whether the error in using  as an estimate of E(A) can be used to improve our estimate of pA is a topic for future research.

as an estimate of E(A) can be used to improve our estimate of pA is a topic for future research.

5 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated a statistical method for estimating the proportions of each sample (Samples A and B) in a two-sample mixture (AB). This method requires expression data generated from the mixed sample AB and expression data generated from a purified sample of one type A. Given this information, the method approximates the proportion pA as the minimum of the ratios of expression in the mixed and purified samples, where the minimum is taken over genes. For this estimate to be accurate, it is required that the data be transformed; the value of the parameter of the transformation is determined by a geometric argument involving the minimum radius of curvature of a function, parameterized as a curve in the plane. Our results show that our method provides a reasonably accurate estimate of pA on both proprietary and publicly available datasets.

As demonstrated in Cleator et al. (2006) a large value of pA (say, over 0.5) can have a substantial effect on the results of tests for differential expression and confound tumor classification. However, whether a large pA should be cause for concern depends on the specific study. We would argue that pA should be assessed in all samples, but the action of the investigator in response to a large value of pA may vary from no action to discarding the sample from further consideration. In the case where pA is very large, our method will still give a reasonable estimate of  but the variability in this estimate could be large. Whether a large pA necessitates a renormalization of the data is unknown; we conjecture that if

but the variability in this estimate could be large. Whether a large pA necessitates a renormalization of the data is unknown; we conjecture that if  and E(A) are comparable then renormalization is unnecessary.

and E(A) are comparable then renormalization is unnecessary.

The results presented are preliminary and as such further research is required to optimize and validate our method. Our bootstrap point estimates and confidence intervals could be substantially improved by increasing the number of bootstrap samples T and running diagnostics to ensure that the number of samples and size of samples are adequate for generating valid bootstrap quantities of interest (Canty et al., 2002). In addition, we would like to explore the relationship between the method of normalization and our estimation technique. By altering the noise distribution, normalization alters the relationship between the noise and the values of Ri, thereby influencing the accuracy of minRi as an estimate of pA. The extent of this influence is unknown, but further research may help determine which normalization method yields the most accurate estimate of pA. Finally, the calculation of the radius of curvature depends on the estimation of the second derivative of the curve; we approximate the second derivative by the second difference equation [Equation (4)]. This approximation is accurate if the curve is smooth and is well sampled, i.e. the distance between sk and sk+1 is small. Using a well-sampled curve in our method can be computationally expensive if the range of value of α (i.e. values of s) is large. We would like to design a variation of our method which starts with a sparsely sampled curve over a large range of values of α and iteratively narrows the range of interest and increases the sampling density as information about the probable location of s* is obtained. This should yield a better estimate of pA at lower computational expense. We hope to implement this variation and provide our approach to the statistics community as an R package (R Development Core Team, 2009).

Our definition of the ‘elbow’ of a curve as the point of minimum radius of curvature is applicable to other problems in statistics, such as the choice of the number of principal components in a principal components analysis (Jolliffe, 2002). One existing way to make this choice is to identify the ‘elbow’ of the curve from a scree plot and choose the number of components closest to the ‘elbow’. Our procedure for finding the minimum radius of curvature, coupled with a curve-fitting method, may be directly applicable to this problem. This would provide a formalization, in the spirit of Zhu and Ghodsi Zhu and Ghosdi (2006), of what is currently an ad hoc approach.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the Center for Computational Science and the lab of Marc E. Lippman, MD, for their suggestions and input.

Funding: National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K25 CA111636 to J.C.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Affymetrix Inc. Affymetrix Expression Console Software Version 1.0 — User Guide. Santa Clara, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ames W. Numerical Methods for Partial Differential Equations. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett T, et al. NCBI GEO: mining tens of millions of expression profiles—database and tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;35:D760–D765. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canty A, et al. Bootstrap diagnostics and remedies. Can. J. Stat. 2002;34:5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Causton H, et al. Microarray gene expression data analysis: A beginner's guide. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cleator S, et al. The effect of the stromal component of breast tumours on prediction of clinical outcome using gene expression microarray analysis. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:R32. doi: 10.1186/bcr1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning M, et al. beadarray: R classes and methods for illumina bead-based data. Bioinformatics. 2008a;23:2183–2184. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning M, et al. Statistical issues in the analysis of illumina data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008b;9:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Bootstrap methods: Another look at the jackknife. Ann. Stat. 1979;7:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fend F, Raffeld M. Laser capture microdissection in pathology. J. Clin. Pathol. 2000;53:666–672. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.9.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D. Mixture models for assessing differential expression in complex tissues using microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1663–1669. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosink M, et al. Electronically subtracting expression patterns from a mixed cell population. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:3328–3334. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illumina Inc. BeadStudio Gene Expression Module v3.4 User Guide (11317265 Rev A). San Diego, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone D, et al. Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Genome Informatics (GIW 2008) Poster; 2008. Effects of different normalisation and analysis procedures on illumina gene expression microarray data. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe I. Principal components analysis. 2nd. Berlin: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Koltai H, Weingarten-Baror C. Specificity of DNA microarray hybridization: characterization, effectors, and approaches for data correction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2395–2405. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahdesmaki H, et al. In silico microdissection of microarray data from heterogeneous cell populations. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeb H. Conditional predictive inference post model selection. Ann. Stat. 2009;37:2838–2876. [Google Scholar]

- Lipschutz M. Schaum's outline of theory and problems of differential geometry. New York: McGraw Hill; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Lu P, et al. Expression deconvolution: A reinterpretation of DNA microarray data reveals dynamic changes in cell populations. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:10370–10375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832361100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAQC Consortium. The microarray quality control (MAQC) project shows inter- and intraplatform reproducibility of gene expression measurements. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1151–1161. doi: 10.1038/nbt1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michiels S, et al. Prediction of cancer outcome with microarrays: a multiple random validation strategy. Lancet. 2005;365:488–492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17866-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman J, et al. Clinico-genomic models for personalized prediction of disease outcomes. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8431–8436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401736101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2009. ISBN 3-900051-07-0. [Google Scholar]

- Shearstone J, et al. Accurate and precise transcriptional profiles from 50 pg of total RNA or 100 flow-sorted primary lymphocytes. Genomics. 2006;88:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, et al. Inference after model selection. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2004;99:751–761. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart R, et al. In silico dissection of cell-type-associated patterns of gene expression in prostate cancer. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:615–620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536479100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van't Veer L, et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415:530–536. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venet D, et al. Separation of samples into their constituents using gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:S279–S287. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.suppl_1.s279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, et al. Computational expresssion deconvolution in a complex mammalian organ. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:328. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheelan S, et al. The incredible shrinking world of DNA microarrays. Mol. Biosyst. 2008;4:726–732. doi: 10.1039/b706237k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Ghosdi A. Automatic dimensionality selection from the scree plot via the use of profile likelihood. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2006;51:918–930. [Google Scholar]