Abstract

Purpose

To provide an overview of and discuss newly authorised medicines with an improved efficacy.

Methods

This analysis focussed on new medicines with an improved efficacy based on the results of randomised active control trials. Information on comparative efficacy was obtained from the European Medicines Agency European Public Assessment Reports.

Results

Between 1999 and 2005 we identified 122 new medicines with a new active substance. Of these, 13 (10%) were shown to be superior to already available medicines in terms a statistically significant difference in primary clinical endpoints.

Conclusions

A proven advantage in efficacy at an early stage of drug development is the exception rather than the rule. The absence of evidence demonstrating differences between medicines does not necessarily mean that there are no actual differences. Optimal pharmacotherapy would benefit from more comparative research in the development of new medicines. The results of comparative trials need to be critically evaluated for their specific value in clinical practice. To this end, prescription data may be helpful.

Keywords: Added therapeutic value, Comparative information, Market authorisation, Randomised active control trials, Superiority trials

Introduction

The ultimate goal of developing new medicines should be an improvement in treatment—namely, the new medicine should provide some additional clinical benefit to patients compared to those currently available [1–4]. This added therapeutic value may lie in one or any of a number of different properties, such as efficacy, safety, applicability, convenience of administration, among others. Of these, efficacy and safety are considered to be the most important: the new medicine should be more efficacious and/or safer.

Demonstrating any improvement is not an explicit condition for being granted marketing authorisation. Data on quality, efficacy and safety are therefore needed in order to demonstrate a favourable benefit/risk ratio when treating a patient for the claimed therapeutic indication. In this context, placebo controlled trials provide robust evidence [5, 6]. However, in the case of new medicines for which good alternatives are available, the regulatory authorities need to be sure that the possibility has been excluded that patients are treated with a product that is less efficacious or less safe [7]. Files submitted to the regulatory authorities can include studies that demonstrate efficacy by confirming the absence of a difference (equivalence trial) or by showing that the new medicine is no worse than an existing medicine (noninferiority trial). Efficacy can also be demonstrated by showing an improved efficacy compared with a medicine already being used in clinical practice for the same claimed therapeutic indication (superiority trial). It goes without saying that the results of these trials are particularly interesting as they provide information on how new medicines, accurately estimated for their efficacy, contribute to an improvement in treatment options for patients. Unfortunately, statistics on the extent of superior medicines as a result of the marketing authorisation process are scarce.

The aim of this study is to provide an overview of and to discuss newly authorised medicines with an improved efficacy.

Methods

This study was an in-depth analysis of data from a previous study on the availability of comparative information on new medicines at the time European market authorisation was granted [8]. We therefore analysed the European Public Assessment Reports (EPARs) of the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) between 1999 and 2005 on new medicines with a new active substance [9]. The analysis focussed on new medicines with an improved efficacy based on randomised active control trials (RaCTs). Data on the RaCTs extracted from the EPARs included therapeutic indication, objective, comparator, design, clinical endpoints, results and the conclusion of the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) on comparative efficacy.

Results

We identified 122 medicines with a new active substance that had been newly authorised between 1999 and 2005; of these, 58 (48%) had been compared with existing medicines. In total, 153 main/pivotal active control trials had been performed. The objective of 15 (10%) of these was to show superiority—but this was not possible in four trials. For bimatoprost, fondaparinux, peginterferon alfa-2a, peginterferon alfa-2b and tipranavir, the objective of demonstrating superiority was realised. A difference in efficacy was also demonstrated in 13 trials with the primary objective to show noninferiority or equivalence. The medicines were considered to be superior when a statistically significant difference in primary clinical endpoints was demonstrated. In total, superiority was demonstrated in 24 trials for 13 (10%) new medicines in the period 1999–2005 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

New medicines (1999–2005) with an improved efficacy

| New medicine | Indication | Comparator |

|---|---|---|

| Bimatoprost | Glaucoma | Timolol |

| Capecitabine | Colorectal cancer | 5-FU/Folonic acid |

| Emtricitabine | HIV-infections (combination) | Stavudine |

| Fondaparinux | Prevention of venous thromboembolic events | Enoxaparine |

| Insulin aspart | Diabetes mellitus type 1 | Insulin regular human |

| Insulin glulisine | Diabetes mellitus type 2 | Insulin regular human |

| Lopinavir | HIV-infections (combination) | Nelfinavir |

| Peginterferon alfa 2a | Chronic hepatitis C | Interferon alfa 2b Interferon alfa 2a |

| Peginterferon alfa 2b | Chronic hepatitis C | Interferon alfa 2b |

| Tipranavir | HIV-infections (combination) | Protease inhibitors |

| Travoprost | Glaucoma | Timolol |

| Voriconazole | Invasive aspergillosis | Amfotericin B (conv) |

| Zoledronic acid | Hypercalcaemia (tumour-induced) | Pamidronate |

HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus

Discussion

Ideally, claims regarding an added value of a new medicine should be based on the results of comparative trials [3, 10]. However, in a previous study we found that nearly one out of two new medicines had been studied in a randomised active control trial [8]. Further analysis of the data on comparative efficacy revealed that an improvement was demonstrated for only one out of ten new medicines. Despite this small number, the conclusion cannot simply be drawn that advances in pharmacotherapy are restricted to these new medicines. Nevertheless, our results suggest that there is sufficient reason to adopt a critical attitude towards the claims of pharmaceutical companies regarding the added value of their new products.

A number of observations can be made regarding this result. First, our analysis excluded new medicines for which no alternative was available and for which, inevitably, a comparative trial was lacking. However, as such medicines were developed as the first medicinal therapy for life-threatening or serious diseases, such as orphan drugs, they can rightfully be considered to be an improvement in the treatment of patients. Secondly, we only focussed on differences in efficacy and not on properties such as safety, applicability or convenience of administration. The reason for this approach is that main/pivotal trials are particularly used for demonstrating efficacy. Nevertheless, new medicines whose efficacy is equivalent or noninferior may still have advantages in terms of safety. An example of this is tenecteplase, which is used in the treatment of suspected myocardial infarction; based on a study of 17,005 patients, it shows an equivalence comparable to alteplase, but a better safety profile [11].

Another reason for the small number of innovations is that in terms of being granted market authorisation, the demonstration of advantages is not an objective in itself. Consequently, there is no need or requirement to conduct a trial with such an objective. Moreover, pharmaceutical companies would be taking a substantial risk to do so, as failure to demonstrate superiority over a less expensive existing drug could be a financial disaster. The alternative—that a positive result could be expected to lead to substitution of the comparator—appears to carry less weight.

We should note that whether the 13 medicines in our analysis are really a therapeutic improvement depends on a sound review of all relevant properties, the clinical relevance of the differences and the appropriateness of the comparator. It is always important to meticulously add up all of the advantages and disadvantages. This also applies to the medicines in our study, as least as far as it is possible to assess these medicines using the data in the EPAR. For most studies, the EPAR does not provide the basic details of trial design and results in a uniform fashion.

According the EPAR, the efficacy of bimatoprost and travoprost is superior to that of timolol in the treatment of glaucoma, but the safety profiles of the former are inferior due to a higher frequency of ocular side effects. The trial on tipranavir demonstrated a superior antiviral activity, but also a higher frequency of hepatic events and lipodystrophy. Comparative efficacy is always linked to a specific comparator, therapeutic indication and type of patients. In naive human immunodeficient virus (HIV)-infected patients, emtricitabine was more efficacious than stavudine but less efficacious than lamivudine; in experienced patients, lamivudine and stavudine had equal efficacy. In terms of the appropriateness of the comparator, we can conclude that in this study the choice of the comparator in the trials that demonstrated superiority was in line with recommendations on standard treatment [12].

Another issue in critical evaluations of demonstrated superiority is the choice of the primary clinical endpoint. A composite endpoint was used for fondaparinux; an analysis of all the endpoint events reveals that the incidence of symptomatic venous thromboembolic events, including pulmonary embolism, was not significantly different between treatment groups [13, 14].

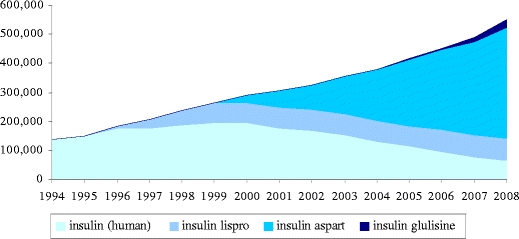

It should also be realised that drawing a conclusion of superiority based on a statistically significant difference says nothing about the practical significance of the medicine. The absolute differences in the change in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels that were demonstrated for insulin aspart and insulin glulisine compared to regular insulin were, at best, of limited clinical relevance. Moreover, there was no relevant difference in terms of the incidence of hypoglycaemic events. In this context, it is interesting to follow developments in the prescription of fast-acting insulin in the treatment of diabetes, as the results of clinical studies may not always be reflected in practice [15, 16]. For prescription data, we used the GIP database of the Health Care Insurance Board of the Netherlands. This database contains data on prescriptions for extramural medicines. This information was obtained from health insurance organisations and is based on a sample of more than 12 million people. Graph 1 shows the trends in the usage of human insulin and fast-acting insulins before and after the introduction of insulin aspart. The degree to which insulin aspart is used cannot be solely explained by the results of the premarketing trials. The more rapid onset and shorter duration of action of the insulin analogue is thought to facilitate a more flexible life style in comparison with the use of soluble human insulins [17]. However, this prescription practice should also apply to insulin lispro, which can be regarded as being comparable to insulin aspart [18].

Graph 1.

Trend in the number of prescriptions for fast-acting insulins. After the introduction of insulin aspart in 1999, there was a decrease in the number of prescriptions for soluble human insulin; however, use of the latter had been decreasing since the introduction of insulin lispro in 1996. Since 2004, insulin aspart is the most prescribed fast-acting insulin. The introduction of insulin glulisine in 2005 has had little impact on the number of prescriptions for the other insulins

The significant advantages and disadvantages of new medicines may only become evident during the course of time, on the basis of further study and experience. This means that assessing the added value of a new medicine is not a one-off incident but a continuous process that is supported by monitoring usage by means of prescription data.

This study shows and discusses how proven superiority, as shown through well-demonstrated advantages in efficacy at an early stage of drug development, is the exception rather than the rule. The absence of evidence for differences between medicines does not necessarily mean that there are no differences. Insight into differences and similarities between medicines, however small they may be, is important in order to be able to make the right choice for the right patient in clinical practice. Therefore, optimal pharmacotherapy would benefit from more comparative research in the development of new medicines. This study also shows that the results of comparative trials should be critically evaluated in terms of their specific value to clinical practice. To this end, prescription data may be helpful.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors have no support or funding to report

Competing interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Dent TH, Hawke S. Too soon to market. Br Med J. 1997;315:1248–1249. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7118.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gale EA, Clark A. A drug on the market. Lancet. 2000;355:61–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)07304-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry D, Hill S. Comparing treatments. Br Med J. 1995;310:1279. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6990.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Society of Drug Bulletins (2001) ISDB declaration on therapeutic advance in the use of medicines. International Society of Drug Bulletins, Paris

- 5.Lewis JA, Jonsson B, Kreutz G, Sampaio C, van Zwieten-Boot B. Placebo-controlled trials and the Declaration of Helsinki. Lancet. 2002;359:1337–1340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (2000) Note for guidance on choice of control group in clinical trials (CPMP/ICH/364/96). EMEA, London

- 7.Koopmans PP, de Graeff PA, Zwieten-Boot BJ, Lekkerkerker JF, Broekmans AW. Clinical evaluation of efficacy and adverse effects in the (European) registration of drugs: what does it mean for the doctor and the patient? (in Dutch) Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2000;144:756–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Luijn JCF, Gribnau FW, Leufkens HG. Availability of comparative trials for the assessment of new medicines in the European Union at the moment of market authorization. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:159–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02812.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (2009) European Public Assessment Reports. Available at: http://www.emea.europa.eu/htms/human/epar/eparintro.htm. Accessed Oct 2009

- 10.Kaplan W (2004) Comparative effectiveness of medicines and use of head-to-head comparative trials In: Kaplan W (2004) Priority medicines for Europe and the world. Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, The Hague

- 11.Van De Werf F, Adgey J, Ardissino D, et al. Single-bolus tenecteplase compared with front-loaded alteplase in acute myocardial infarction: the ASSENT-2 double-blind randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354:716–722. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)07403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Luijn JCF, van Loenen AC, Gribnau FWJ, Leufkens HGM. Choice of comparator in active control trials of new drugs. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:1605–1612. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heit JA. The potential role of fondaparinux as venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip or knee replacement or hip fracture surgery. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1806–1808. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turpie AGG, Bauer KA, Eriksson BI, Lassen MR. Fondaparinux vs enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in major orthopedic surgery: a meta-analysis of 4 randomized double-blind studies. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1833–1840. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heerdink ER, Urquhart J, Leufkens HG. Changes in prescribed drug doses after market introduction. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11:447–453. doi: 10.1002/pds.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wathen B, Dean T. An evaluation of the impact of NICE guidance on GP prescribing. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:103–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raskin P, Guthrie RA, Leiter L, Riis A, Jovanovic L. Use of insulin aspart, a fast-acting insulin analog, as the mealtime insulin in the management of patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:583–588. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plank J, Wutte A, Brunner G, et al. A direct comparison of insulin aspart and insulin lispro in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2053–2057. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.11.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]