Abstract

The ability to perform ab initio electronic structure calculations that scales linearly with the system size is one of the central aims in theoretical chemistry. In this study, the implementation of the divide-and-conquer (DC) algorithm, an algorithm with the potential to aid the achievement of true linear scaling within Hartree-Fock (HF) theory is revisited. Standard HF calculations solve the Roothaan-Hall equations for the whole system; in the DC-HF approach, the diagonalization of the Fock matrix is carried out on smaller subsystems. The DC algorithm for HF calculations was validated on polyglycines, polyalanines and eleven real three-dimensional proteins of up to 608 atoms in this work. We also found that a fragment-based initial guess using molecular fractionation with conjugated caps (MFCC) method significantly reduces the number of SCF cycles and even is capable of achieving convergence for some globular proteins where the simple superposition of atomic densities (SAD) initial guess fails.

Keywords: divide-and-conquer, Hartree-Fock, initial guess, superposition of atomic densities (SAD), molecular fractionation with conjugated caps (MFCC), protein

Introduction

Ab initio quantum mechanical methods have been developed over the past several decades and successfully applied to the study of the chemical properties for small to moderate-sized molecules. The routine application of these full quantum mechanical calculations on macromolecules (molecules containing greater than 500 atoms) continues to pose a great challenge for theoretical chemists. The major limitation of ab initio methods is the scaling problem, since the computational cost of ab initio methods increases considerably as the size of the molecule increases. For instance, Hartree-Fock (HF)1 and Density Functional Theory (DFT)2 scale as O(N4), post-Hartree-Fock MP23 scales as O(N5) and the coupled cluster(CC)4-9 method that includes single and double excitations (CCSD) scales as O(N6). In modern HF calculations, the computational cost for the 2-electron integrals can be reduced from O(N4) to O(N2) using a simple screening technique10. Hence, the dominant step for large molecules becomes the matrix diagonalization, which scales as O(N3). In this study, our goal was to reduce the computational cost of the diagonalization step in HF calculations to linear with system size.

The state-of-the-art linear-scaling algorithms, which make the computational cost scale linearly O(N) with the system size, have attracted the focus of many theorists during the past decade.11-21 Much effort has been devoted to the development of linear-scaling methods in order to compute the total energy of large molecular systems at the Hartree-Fock (HF) or density functional theory (DFT) level.12,15,18,22-26 One of the challenges is to speed up the calculation of long-range Coulomb interactions when assembling the Fock matrix elements. Fast multipole based approaches have successfully reduced the scaling in system size to linear14,16-18,25 and made HF and DFT calculations affordable for larger systems when small to moderate sized basis sets are utilized. The more recently developed Fourier Transform Coulomb method of Fusti and Pulay27,28 reduced the steep O(N4) scaling in basis set size to quadratic and makes the calculations much more affordable with larger basis sets.29 There is also a class of fragment-based methods for quantum calculation of protein systems including the divide and conquer (D&C) method of Yang22, Yang and Lee,23 Dixon and Merz,30 Gogonea et al.,31 Shaw and St-Amant,32 and Nakai and co-workers,33-36 the adjustable density matrix assembler (ADMA) approach method of Exner and Mezey,26,37-39 the fragment molecular orbital (FMO) method of Kitaura and co-workers,13,40,41 and the molecular fractionation with conjugate caps (MFCC) approach developed by Zhang and co-workers.42,43 Most applications of these methods to protein systems have been largely limited to semiempirical, HF and DFT calculations. Among these approaches, FMO has been applied to higher level ab initio calculations such as second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2)44 and coupled cluster theory (CC).45 Nakai and co-workers have recently proposed DC-MP233,36,46 and DC-CCSD47 approaches; however, only systems of linear chains or near-linear chains have been tested so far for the divide-and-conquer algorithm for ab initio calculations.

In the DC algorithm, the total system is divided into small fragments. Atoms within adjustable buffer regions surrounding each fragment are included in the calculations to preserve the chemical environment of the divided subsystem. A set of local Roothaan-Hall equations is then solved for each subsystem and an approximate full density matrix of the entire molecular system is built up from subsystem contributions. By solving the HF self-consistent field (SCF) equation iteratively, the final converged full density matrix is used to obtain the total energy of the entire system. In this manner, linear scaling of the Fock matrix diagonalization step is achieved as a result of the fact that a set of smaller subsystem Fock matrices is diagonalized in the DC-HF approach rather than the global Fock matrix diagonalization for traditional HF calculations. Furthermore, divide-and-conquer calculations may be efficiently parallelized because the individual subsystem calculations are solved separately. In the DC-HF approach, the memory usage will increase linearly as the size of the system increases, which is also an important feature of this approach.

The aim of our current research is to further develop and validate the divide-and-conquer (DC)22,23,30,32,46-48 methodology to aid in the application of ab initio methods to biomacromolecules. In this study, our goal is to validate divide-and-conquer algorithm for Hartree-Fock calculations on globular proteins. Moreover, we propose a fragment-based initial guess using molecular fractionation with conjugated caps (MFCC) method to reduce the number of SCF cycles, and different division schemes are compared.

Computational Approaches

Divide-and-Conquer Approach on the Hartree-Fock calculations

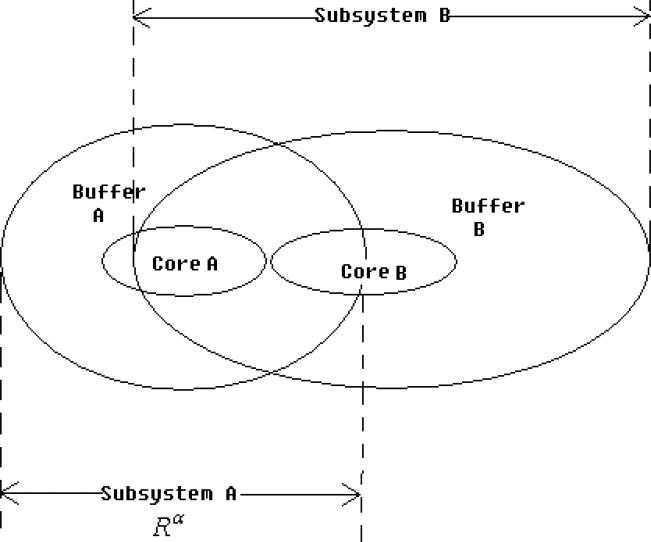

In protein systems, the divide-conquer approach is based on the chemical locality; this assumes that local regions of a protein are only weakly influenced by the atoms that are far away from the region of interest. The whole system is divided into fragments called core regions (Coreα). A buffer region (Bufferα) is assigned for each core region to account for the environmental effects. The combination of every core region and its buffer region constitutes each individual subsystem (Rα) as illustrated in Figure 1. Local MOs of each subsystem are solved by the Roothaan-Hall equation

| (1) |

where Fα and Sα are local Fock matrix and local overlap matrix, respectively.

| (2) |

After the local MO coefficient matrices Cα are obtained, the total density matrix of the whole system is given by

| (3) |

where is the partition matrix,

| (4) |

and is the local density matrix defined by

| (5) |

where is a smooth approximation to the Heaviside step function:

| (6) |

εF is determined through the normalization of the total number of electrons of the whole system.

| (7) |

After the density matrix is converged, the total HF energy is given as

| (8) |

where is the local one-electron core Hamiltonian matrix similar to the definition of local Fock matrix in equation 2.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the subsetting scheme used in divide-and-conquer calculations.

For HF calculations on large systems, the construction of the Coulomb matrix and exchange matrix along with the diagonalization of the Fock matrix constitute the three most time-consuming steps. The Hamiltonian matrix diagonalization intrinsically scales as O(N3). In the divide-and-conquer scheme the diagonalization calculation is performed on each submatrix, which will naturally make the SCF diagonalization step scale linearly with the number of subsystems. However, it is important to realize that the divide-and-conquer algorithm does not help to reduce the scale of computation of the Coulomb matrix and exchange matrix. The continuous fast multipole method (CFMM)14,16-18,25,49-51 and the linear exchange K approach (LinK)52,53 provide ways in which the Coulomb matrix and exchange matrix can be made linear-scaling, respectively.

MFCC Initial Guess

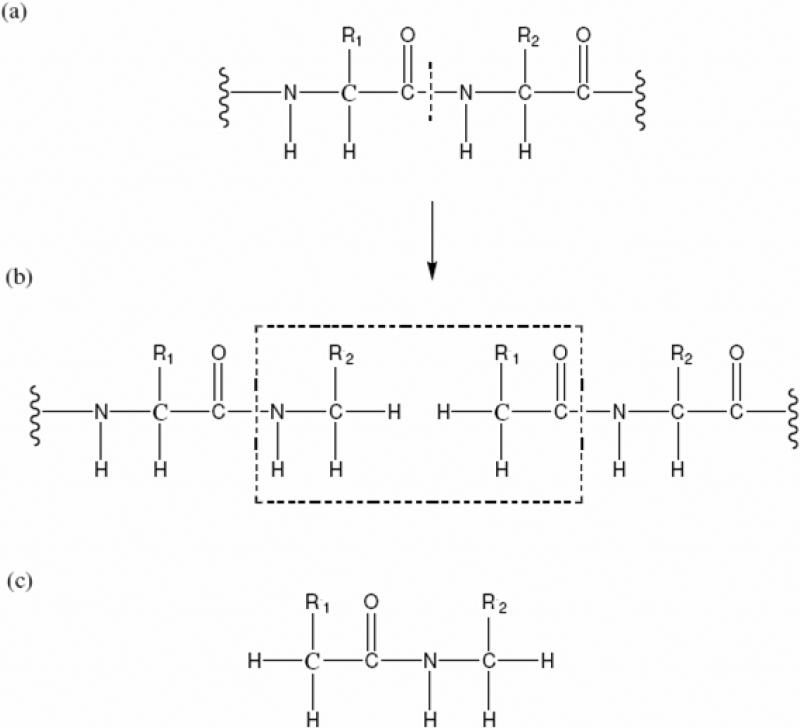

Here we introduce a fragment-based initial guess for ab initio calculations using the molecular fractionation with conjugate caps (MFCC) algorithm as described elsewhere42,54,55. In the spirit of the MFCC approach, the full density matrix of the protein can be assembled by a linear combination of fragment density matrices

| (9) |

where is the density matrix element of the ith protein fragment, is the density matrix element of the jth conjugate cap. Nf and Nc are the total number of the protein fragments and conjugate caps, respectively. The MFCC partition scheme to cut a protein into amino-acid fragments and conjugate caps is shown in Figure 2. First, a series of single point HF calculations on all the fragments and conjugate caps are performed, then the full density matrix of the protein obtained using the converged fragment density matrices based on equation 9 is taken as the initial guess for the subsequent divide-and-conquer HF calculations. All the ab initio calculations were implemented in an in-house developed quantum chemistry package QUICK.56

Figure 2.

The MFCC scheme in which the peptide bond is cut (a) and the fragments are capped with Ccap and its conjugate Ccap* (b). The atomic structure of the concap is shown in (c). The concap is defined as the fused molecular species of Ccap* –Ccap.

Results and Discussion

Accuracy and Timing Comparisons

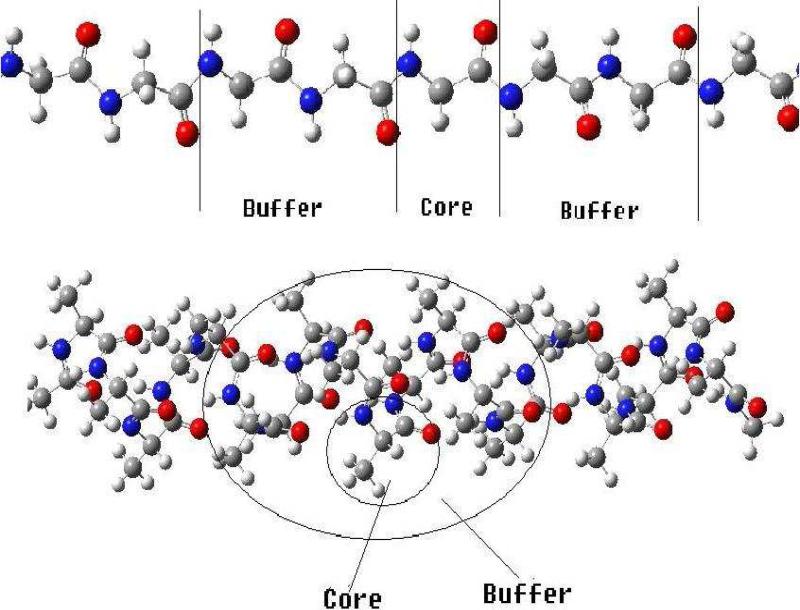

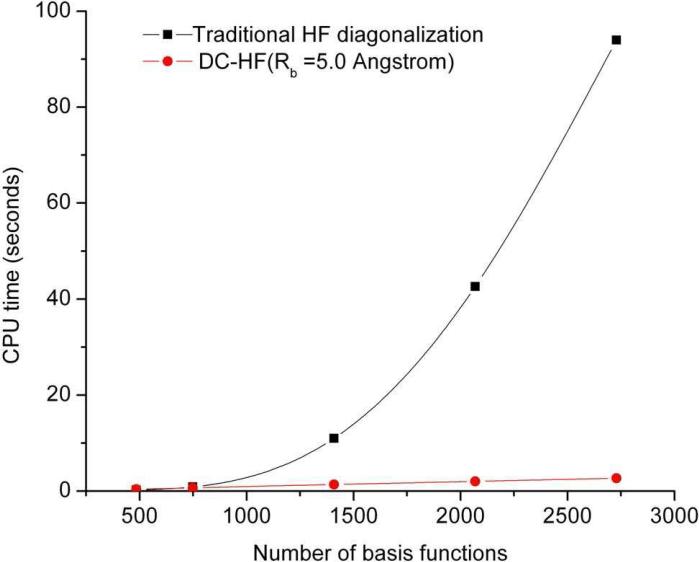

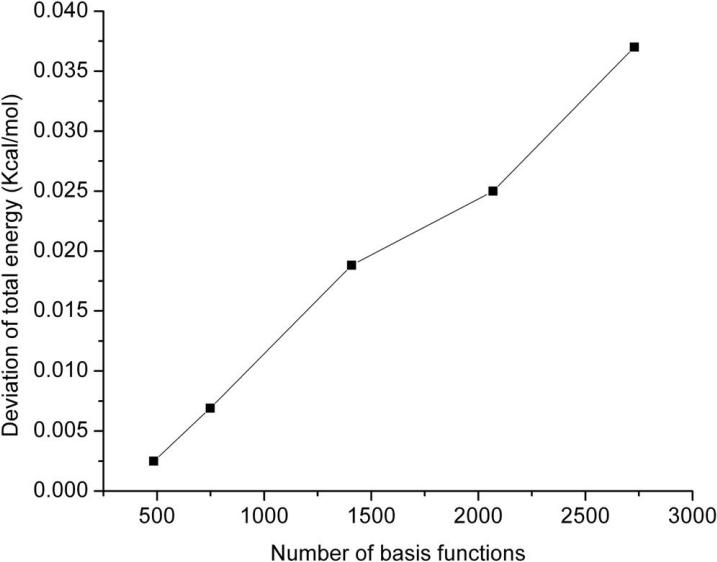

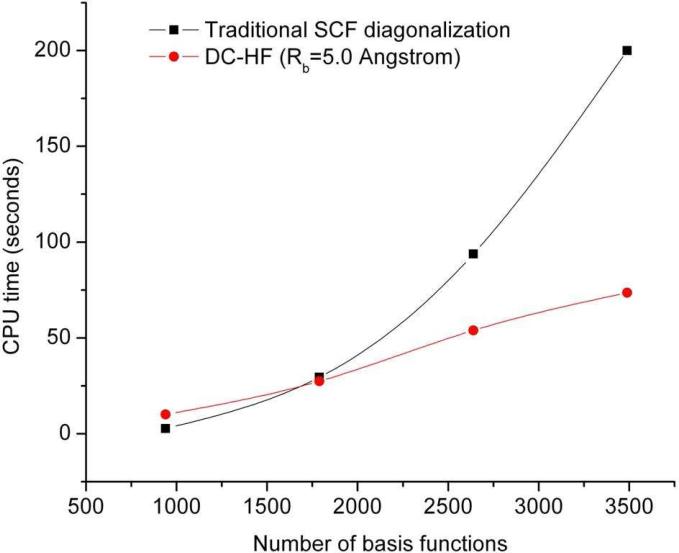

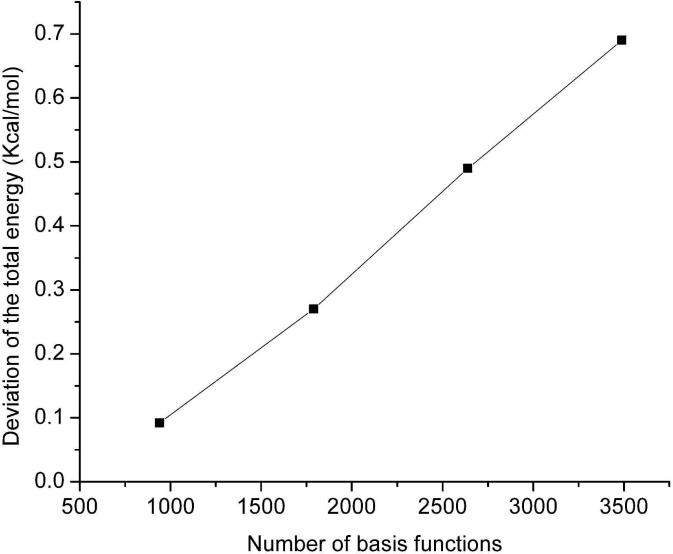

In this section we assess the DC-HF approach performance by performing calculations on two types of simple systems: extended polyglycine (gly)n and an alpha-helix of polyalanine (α – (ala)n see Figure 3). All the calculations discussed here use the 6-31G* basis set. A buffer radius of Rb = 5.0 Å was adopted for all DC-HF calculations. Within this definition we include all the residues that contain any atoms within 5Å from the core region as part of the buffer region. A comparison of the CPU time required to solve the SCF equations on the extended polyglycine (gly)n (n=6~40) using the standard HF and DC-HF approaches is shown in Figure 4. As expected, the computational scale for the DC-HF diagonalization calculation is O(N), in contrast to O(N2.9) for the traditional HF SCF diagonalization on the full Fock matrix of the entire system. Moreover, since the polyglycine is extended, the basis set crossover point is between 485 and 749. Figure 5 shows the deviation of DC-HF energy compared to the full system calculation on extended polyglycine systems. The error becomes larger as the size of the system increases; however, all of the deviations are within 0.04 kcal mol−1. This good accuracy suggests that we can employ the divide-and-conquer scheme to study large, 3-dimensional systems. The computational cost and accuracy of DC-HF for α – (ala)n (n=10~40) systems are illustrated in Figures 6 and 7, respectively. Because of the helix structure, each subsystem contains a larger number of residues than in the extended system using the same buffer size. As illustrated in Figure 6, the crossover point is around 1789, which is over 2-times larger than for the polyglycine example. Each DC-HF diagonalization SCF cycle in this example scales as O(N1.1), in contrast to O(N2.7) for the traditional HF diagonalization cost. Furthermore, the total energy errors for the α -helical polyalanines are slightly larger than those for the extended polyglycine systems (see Figure 7), but theay are still in a good agreement with the full system calculations since the largest error is less than 0.7 kcal mol−1 for α – (ala)40.

Figure 3.

The subsetting schemes for divide-and-conquer calculations on the extended polyglycine (Gly)n (upper) and polyalanine in an α – helical structure (α – (Ala)n, bottom).

Figure 4.

The average computational time to diagonalize the Fock matrix in each SCF cycle using traditional HF and DC-HF for a series of extended polyglycines at the HF/6-31G* level.

Figure 5.

The accuracy of the total energy calculated by the DC-HF approach on extended polyglycine systems compared to full system calculations.

Figure 6.

Similar to Figure 4, but for the polyalanine systems in an α – helical structure α – (Ala)n.

Figure 7.

Similar to Figure 5, but for the polyalanine systems in an α – helix structure α – (Ala)n.

In the current DC-HF approach, the scale for the computation of the Coulomb matrix is still O(N2) after prescreening the two-electron integrals10. When we apply equation 2 to construct the subsystem Fock matrix, the long-range Coulomb interactions between the local subsystem and distant atoms cannot be circumvented, thus, it should be emphasized that the D&C algorithm itself does not reduce the scale of Coulomb and exchange matrix evaluations and other approaches are necessary to achieve this result (e.g., CFMM)14,16,17,49.

MFCC Initial Guess for Div&Con HF calculations

Next we compare the number of SCF cycles necessary to reach convergence when the SAD (superposition of atomic densities) and MFCC initial guesses are used in the divide and conquer scheme using the 6-31G* basis set (see Table 1). The convergence criterion in all examples was set to 10−6 a.u. on the root-mean-squared change of the density matrix elements and 10−4 a.u. for the maximum change of the density matrix elements. Nakai and co-workers35 and Shaw and St-Amant32 have noted that DIIS causes SCF calculations to oscillate at the final stage of the SCF convergence process due to the slight errors introduced by the DC approximation for assembling the density matrix (see equation 3). In our HF DC calculations, the DIIS technique was turned off when the root-mean-squared change of the density matrix elements reaches 10−4 a.u.. We also found that although DIIS works in the early stages of the SCF procedure, we get the best performance when only two previous Fock matrices were stored in the DIIS calculations. One can see from Table 1 that the HF DC calculations usually requires more SCF cycles than the non-DC runs, however, for the polyglycine and polyalanine systems, the MFCC initial guess helps to reduce the number of SCF cycles in both DC and non-DC cases.

Table 1.

Number of SCF cycles needed to reach convergence for the SAD and MFCC initial guess at the HF/6-31G* level.

| Div&Con | Non-Div&Cona) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| System | SAD initial guess | MFCC initial guess | SAD initial guess | MFCC initial guess |

| Gly6 | 18 | 10 | 12 | 7 |

| Gly10 | 18 | 11 | 12 | 7 |

| Gly20 | 18 | 10 | 12 | 6 |

| Gly30 | 18 | 10 | 12 | 6 |

| Gly40 | 18 | 8 | 12 | 7 |

| α-(Ala)10 | 18 | 15 | 12 | 9 |

| α-(Ala)20 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 9 |

| α-(Ala)30 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 8 |

| α-(Ala)40 | 15 | 12 | 12 | 8 |

In the SCF procedure of non-Div&Con case, every 10 previous Fock matrices were stored in the DIIS calculations; while for the Div&Con case, every 2 previous Fock matrices were stored in the DIIS calculations until the root-mean-squared change of the density matrix elements reaches 10−4 a.u., after that, the DIIS technique was turned off.

Residue-centric Core Region versus Atom-centric Core Region

Previously, all the calculations used a residue based definition for the core region. We have also examined an atom based subsetting strategy for the core region in polyglycines and polyalanines. One can see from Table 2, the converged total energies using atom-centric core region were almost identical to those using a residue-based cutoff. Indeed, the overall mean unsigned deviation is as low as 0.054 kcal mol−1. This is an attractive aspect of the divide and conquer approach since it allows for parallelization at the atom level rather than at the much larger reside based cutoff scheme.

Table 2.

The converged total energies (a.u.) (at the HF/6-31G* level) using two different subsetting schemes: residue-based with buffer of 5Å and atom-based with a buffer of 7Å. (MUD: mean unsigned deviation)

| System | Residue-centric Core Region | Atom-centric Core Region | Deviation (kcal mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gly10 | −2314.783296 | −2314.783272 | −0.015 |

| Gly20 | −4382.595749 | −4382.595726 | −0.014 |

| Gly30 | −6450.407962 | −6450.407938 | −0.015 |

| Gly40 | −8518.221662 | −8518.221679 | 0.011 |

| α-(Ala)20 | −5164.086850 | −5164.086911 | 0.038 |

| α-(Ala)30 | −7622.660188 | −7622.660373 | 0.116 |

| α-(Ala)40 | −10081.238571 | −10081.238839 | 0.168 |

| MUD | 0.054 | ||

Validation on Three-dimensional Protein Systems

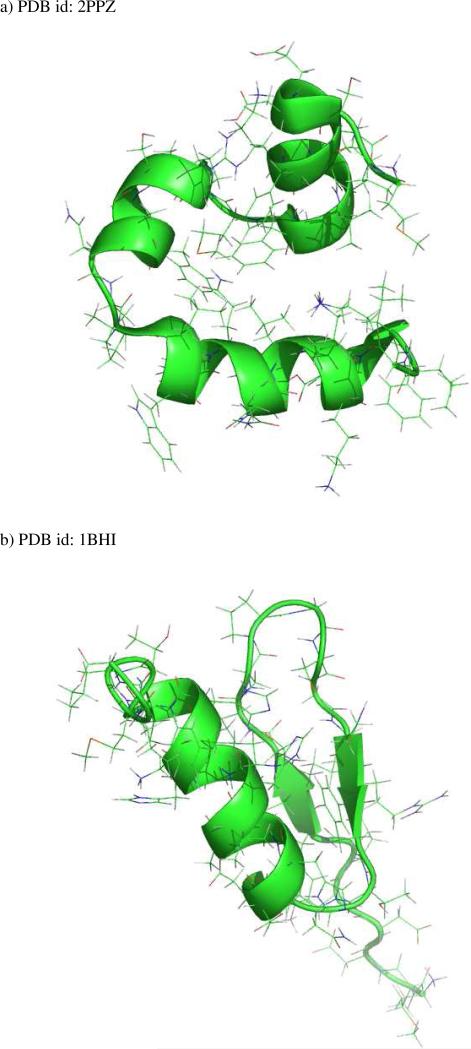

No previous studies have utilized the divide-and-conquer HF approach on three-dimensional globular proteins. In order to address this point, we have validated the accuracy of divide-and-conquer HF/6-31G* calculations on eleven real proteins. The systems ranged from 304 atoms to 608 atoms and are listed in Table 3. The proteins consisted of α – helical structures (see Figure 8a) or are mixed α – β – structures (see Figure 8b). As shown in Table 3, the largest deviation is 2.25 kcal mol−1 and the overall mean unsigned deviation is only 0.97 kcal mol−1 compared to standard full system calculations. Importantly, the observed error is large than what was observed for the 0ne-dimensional examples, but is still within acceptable limits. This study sets the stage for the wide application of divide-and-conquer calculations on real protein systems. Furthermore, we have found that for five proteins, the divide-and-conquer HF calculations are not able to reach convergence using the simple SAD initial guess, while all the cases converged using the MFCC initial guess. Therefore, we conclude that the quality of initial guess plays an important role in insuring the convergence of divide-and-conquer calculations. Fragment-based electron density provides a much better quality initial guess with linear-scaling computational cost and, ultimately, much less computational time when compared to full system calculations.

Table 3.

The total energies (a.u.) of three-dimensional globular proteins obtained using standard full system HF/6-31G* calculations and divide-and-conquer HF/6-31G* calculations using the MFCC initial guess. (MUD: mean unsigned deviation)

| System | Number of atoms | Number of basis functions | Standard full system calculation | Div&Con using MFCC initial guess | Deviation (kcal mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trp-cage | 304 | 2610 | −7439.721780 | −7439.722124 | −0.22 |

| 1VTP | 396 | 3418 | −10014.756053 | −10014.755741* | 0.20 |

| 1BBA | 582 | 5033 | −15103.299186 | −15103.302595 | −2.14 |

| 1AML | 598 | 5178 | −15140.895905 | −15140.897305* | −0.88 |

| 1BHI | 591 | 5124 | −15989.697592 | −15989.696544 | 0.66 |

| 1BZG | 573 | 4851 | −13680.602670 | −13680.602916* | −0.15 |

| 2JPK | 589 | 5000 | −13854.809422 | −13854.810188* | −0.48 |

| 2KCF | 576 | 4991 | −14599.178617 | −14599.180118 | −0.94 |

| 2PPZ | 608 | 5111 | −14957.602116 | −14957.605696 | −2.25 |

| 2RLK | 588 | 5089 | −14589.701015 | −14589.702771* | −1.10 |

| 2YSC | 578 | 5108 | −14634.254517 | −14634.257181 | −1.67 |

| MUD | 0.97 | ||||

Did not converge using the SAD initial guess.

Figure 8.

Two representative three-dimensional protein structures studied in this work. a) PDB id: 2PPZ

Conclusions

In this study, the divide-and-conquer HF theory was revisited in order to examine its potential to study three-dimensional constructs and a new and effective initial guess scheme was introduced. We first validated the accuracy of the divide-and-conquer HF/6-31G* calculations on eleven three-dimensional globular proteins. The overall mean unsigned error was within 1 kcal mol−1 when compared to standard full system calculations. Furthermore, we found that the fragment-based initial guess using the MFCC approach reduces the number of SCF cycles for polyglycine and polyalanine systems. Moreover, the MFCC initial guess facilitated SCF convergence for several of the globular proteins, where the SAD initial guess was unable to yield a converged wavefunction.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH (GM GM044974) for financial support of this research. Computing support from the University of Florida High Performance Computing Center is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Szabo A, Ostlund NS. Modern quantum chemistry : introduction to advanced electronic structure theory. 1st. ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parr RG, Yang WT. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. Vol. 46. 1995. p. 701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Møller C, Plesset MS. Physical Review. Vol. 46. 1934. p. 0618. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartlett RJ, Musial M. Reviews of Modern Physics. 2007;79:291. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Čížek J. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1966;45:4256. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford TD, Schaefer HF. Reviews in Computational Chemistry, Vol 14. 2000;14:33. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kállay M, Gauss J. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2005;123:214105. doi: 10.1063/1.2121589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kállay M, Surján PR. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2001;115:2945. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bomble YJ, Stanton JF, Kállay M, Gauss J. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2005;123:054101. doi: 10.1063/1.1950567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strout DL, Scuseria GE. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1995;102:8448. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwegler E, Challacombe M. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1996;105:2726. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goedecker S. Reviews of Modern Physics. 1999;71:1085. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fedorov DG, Kitaura K. Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 2007;111:6904. doi: 10.1021/jp0716740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Challacombe M, Schwegler E. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1997;106:5526. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friesner RA, Murphy RB, Beachy MD, Ringnalda MN, Pollard WT, Dunietz BD, Cao YX. Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 1999;103:1913. [Google Scholar]

- 16.White CA, Johnson BG, Gill PMW, Head-Gordon M. Chemical Physics Letters. 1994;230:8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.White CA, Johnson BG, Gill PMW, Head-Gordon M. Chemical Physics Letters. 1996;253:268. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scuseria GE. Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 1999;103:4782. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korchowiec J, Lewandowski J, Makowski M, Gu FL, Aoki Y. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2009;30:2515. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang N, Ma J, Jiang YS. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2006;124:114112. doi: 10.1063/1.2178796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daniels AD, Scuseria GE. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1999;110:1321. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang WT. Physical Review Letters. 1991;66:1438. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.66.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang WT, Lee TS. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1995;103:5674. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohn W. Physical Review Letters. 1996;76:3168. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.3168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strain MC, Scuseria GE, Frisch MJ. Science. 1996;271:51. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Exner TE, Mezey PG. Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 2002;106:11791. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fusti-Molnar L. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2003;119:11080. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fusti-Molnar L, Pulay P. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2002;117:7827. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shao Y, Molnar LF, Jung Y, Kussmann J, Ochsenfeld C, Brown ST, Gilbert ATB, Slipchenko LV, Levchenko SV, O'Neill DP, DiStasio RA, Lochan RC, Wang T, Beran GJO, Besley NA, Herbert JM, Lin CY, Van Voorhis T, Chien SH, Sodt A, Steele RP, Rassolov VA, Maslen PE, Korambath PP, Adamson RD, Austin B, Baker J, Byrd EFC, Dachsel H, Doerksen RJ, Dreuw A, Dunietz BD, Dutoi AD, Furlani TR, Gwaltney SR, Heyden A, Hirata S, Hsu CP, Kedziora G, Khalliulin RZ, Klunzinger P, Lee AM, Lee MS, Liang W, Lotan I, Nair N, Peters B, Proynov EI, Pieniazek PA, Rhee YM, Ritchie J, Rosta E, Sherrill CD, Simmonett AC, Subotnik JE, Woodcock HL, Zhang W, Bell AT, Chakraborty AK, Chipman DM, Keil FJ, Warshel A, Hehre WJ, Schaefer HF, Kong J, Krylov AI, Gill PMW, Head-Gordon M. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2006;8:3172. doi: 10.1039/b517914a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dixon SL, Merz KM. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1996;104:6643. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gogonea V, Westerhoff LM, Merz KM. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2000;113:5604. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw DM, St-Amant A. Journal of Theoretical & Computational Chemistry. 2004;3:419. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kobayashi M, Nakai H. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry. 2009;109:2227. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akama T, Fujii A, Kobayashi M, Nakai H. Molecular Physics. 2007;105:2799. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akama T, Kobayashi M, Nakai H. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2007;28:2003. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobayashi M, Akama T, Nakai H. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2006;125:204106. doi: 10.1063/1.2388261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Exner TE, Mezey PG. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2003;24:1980. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Exner TE, Mezey PG. Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 2004;108:4301. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Exner TE, Mezey PG. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2005;7:4061. doi: 10.1039/b509557c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakano T, Kaminuma T, Sato T, Fukuzawa K, Akiyama Y, Uebayasi M, Kitaura K. Chemical Physics Letters. 2002;351:475. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fedorov DG, Kitaura K. Chemical Physics Letters. 2006;433:182. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang DW, Zhang JZH. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2003;119:3599. [Google Scholar]

- 43.He X, Zhang JZH. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2005;122:031103. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fedorov DG, Ishimura K, Ishida T, Kitaura K, Pulay P, Nagase S. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2007;28:1476. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fedorov DG, Kitaura K. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2005;123:134103. doi: 10.1063/1.2007588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kobayashi M, Imamura Y, Nakai H. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2007;127:074103. doi: 10.1063/1.2761878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kobayashi M, Nakai H. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2008;129:044103. doi: 10.1063/1.2956490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dixon SL, Merz KM. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1997;107:879. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwegler E, Challacombe M. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1999;111:6223. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burant JC, Strain MC, Scuseria GE, Frisch MJ. Chemical Physics Letters. 1996;248:43. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shao YH, White CA, Head-Gordon M. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2001;114:6572. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ochsenfeld C. Chemical Physics Letters. 2000;327:216. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ochsenfeld C, White CA, Head-Gordon M. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1998;109:1663. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen XH, Zhang JZH. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2006;125:044903. doi: 10.1063/1.2218341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen XH, Zhang YK, Zhang JZH. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2005;122:184105. doi: 10.1063/1.1897382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He X, Ayers K, Brothers E, Merz KM. QUICK. University of Florida; Gainesville; FL: 2008. [Google Scholar]