Abstract

Magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is a new technique that can be used to visualize and measure the diffusion of water in brain tissue; it is particularly useful for evaluating white matter abnormalities. In this paper, we review research studies that have applied DTI for the purpose of understanding neuropsychiatric disorders. We begin with a discussion of the principles involved in DTI, followed by a historical overview of magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted imaging and DTI and a brief description of several different methods of image acquisition and quantitative analysis. We then review the application of this technique to clinical populations. We include all studies published in English from January 1996 through March 2002 on this topic, located by searching PubMed and Medline on the key words “diffusion tensor imaging” and “MRI.” Finally, we consider potential future uses of DTI, including fiber tracking and surgical planning and follow-up.

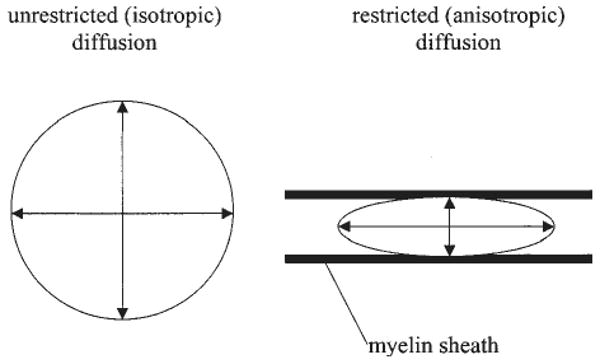

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is an exciting recent technique in neuroimaging that affords a unique opportunity to quantify the diffusion of water in brain tissue. It is based upon the phenomenon of water diffusion known as Brownian motion, named after the English botanist Robert Brown, who in 1827 observed the constant movement of minute particles suspended within grains of pollen.* We now know that molecular motion is affected by the properties of the medium in which it occurs and that diffusion within biological tissues reflects both tissue structure and architecture at the microscopic level. Equal, or isotropic, diffusion occurs when a medium does not restrict molecular motion, as would be the case with cerebrospinal fluid. Skewed, or anisotropic, diffusion, seen in crystals and polymer films, is not equal in all directions. DTI measures diffusion properties and consequently allows spatial description of the medium under study.

Taking advantage of the fact that diffusion is not uniform throughout the brain (differing, for example, between gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid), researchers can employ DTI to evaluate tissue characteristics. The technique is particularly useful in the study of white matter tracts in the brain since the mobility of water is restricted perpendicular to the axons oriented along the fiber tracts (anisotropic diffusion). This is due to the concentric structure of multiple tightly packed myelin membranes wrapped around the axon fibers. Although myelination is not essential for diffusion anisotropy of nerves (see studies on nonmyelinated garfish olfactory nerves1 and on neonate brains prior to the appearance of myelin2,3), myelin is generally assumed to be the major barrier to diffusion in white matter tracts.

DTI evolved from earlier studies using diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique in which a single field gradient pulse is applied during image acquisition, allowing quantitative measurement of water diffusion.4 Displacement of water molecules (diffusion) causes randomization of the nuclear magnetic resonance spin phase, which, in turn, results in signal reduction. The amount of reduction provides a quantitative measure of the diffusion in the gradient direction; thus, only diffusion in the direction of this particular gradient can be detected. Since diffusion is a three-dimensional process, three orthogonal measures are needed to calculate the mean diffusivity for each voxel.

DTI was developed for true multidimensional assessment of diffusion data in vivo.5,6 In contrast to DWI, DTI measures at least six different gradient directions. The diffusion data for each voxel, represented as a 3 × 3 matrix, comprise a diffusion tensor (see Figure 1). In isotropic media, where diffusion along the three main axes is equal, the diffusion tensor is symmetrical in all directions and is visualized as a sphere. In anisotropic media, where the diffusion is different along each axis, the diffusion tensor is visualized as an ellipsoid, with its longest axis indicating the greatest of the so-called principal directions of diffusion. The shape of the tensor ellipsoid depends on the strength of the diffusion along the three principal directions (i.e., its eigenvectors). Within myelinated white matter fiber tracts, the greatest principal direction of diffusion will always indicate the axonal trajectory, since perpendicular diffusion is restricted by myelin sheathing. The shape of the tensor ellipsoid therefore provides qualitative and quantitative measures of white matter tracts within the brain.

FIGURE 1.

Difference between unrestricted (isotropic) and restricted (anisotropic) diffusion within the brain. The shape of the tensor ellipsoid is determined by the strength of the diffusion along three principal directions (its eigenvectors). In nonrestrictive media such as cerebrospinal fluid, where diffusion is equal in all directions, the tensor can be visualized as a sphere. In restrictive media such as white matter, where diffusion is different in all directions, the tensor can be visualized as an ellipsoid.

DWI and its Acquisition in the Brain

DWI was introduced in 1986 by Le Bihan and colleagues.4 From the beginning, however, the widespread application of this technique to clinical studies was greatly impeded by technical constraints, the most important being motion sensitivity, which can cause severe ghosting artifacts or complete signal loss. In attempts to observe molecular displacement in micrometers, it is no surprise that motion of any sort, even unavoidable involuntary head movements or pulsations of blood in the brain tissue, interfere with measurement. The problem is even more serious when scans must be obtained from, for example, a disoriented and confused stroke victim, who may move his or her head excessively. These limitations were a major incentive for the development of faster sequences that are more robust in the face of bulk motion.

The development of diffusion-sensitive pulse sequences followed two basic directions: echo-planar imaging methods,7 which capture a complete image within a single shot, and navigator methods,8 which acquire images in multiple shots, with each shot employing “navigator MR signals” to detect and correct the bulk motion. Although single-shot methods are extremely robust, the elevated sensitivity to magnetic field inhomogeneities inherent in these techniques may lead to image-distortion artifacts, such as susceptibility artifacts, occurring in areas exhibiting large variations in magnetic susceptibility (e.g., interfaces between air, bone, and brain tissue), and chemical shift artifacts, caused by the difference in chemical properties of fat and water. Moreover, spatial resolution is limited, and signal averaging may be necessary. Navigator methods, on the other hand, permit excellent spatial resolution with a minimum of image-distortion artifacts and high signal-to-noise ratio, but they are not as robust and require acquisition times of 10 minutes or more. Furthermore, cardiac gating—that is, synchronization of slice acquisition with heart rate—must be used, which makes the technique less attractive in a routine clinical setting. Recently, researchers have proposed several new techniques (diffusion-weighted radial acquisition of data,9 line-scan diffusion imaging,10 slab-scan diffusion imaging13) that avoid susceptibility and chemical shift artifacts and allow for resolution higher than that obtained with echo-planar imaging.

Quantitative Representation of Diffusion in DWI

As noted previously, the measurement of water diffusion in tissues is based on probing the movement of water molecules within the tissue environment. In pure liquids, such as water, individual molecules are in constant motion in every direction due to random (Brownian) motion. In tissues, however, various tissue components (larger molecules, intracellular organs, membranes, cell walls, and so on) restrict the Brownian motion. In cerebrospinal fluid and many tissues (liver and cerebral gray matter, for example), when averaged over the macroscopic scale of image voxels, this restriction is identical in every direction—the diffusion is isotropic. In some very structured tissues, however, such as muscle or cerebral white matter, cellular arrangement shows a preferred direction of water diffusion that is largely uniform across the entire voxel—the diffusion is anisotropic. The diffusion coefficient is a measure of this molecular motion, and it can be determined by applying consecutive magnetic field gradient pulses and then measuring the change between the images acquired. Each gradient is typically applied for several tens of milliseconds, during which time the average water molecule in brain tissues may migrate 10 or more micrometers in a random direction. The irregularity of the motion entails a signal loss that can be used to quantify the diffusion constant. This MR measurement, however, fails to differentiate diffusion-related motion from blood flow, perfusion, bulk tissue, or tissue pulsation motions. Thus, the diffusion value obtained with this technique is not an actual diffusion coefficient, but only an apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC).

Diffusion Tensor Imaging

The concept of a diffusion tensor was introduced to the field of MR diffusion imaging by Basser and colleagues in 1994.6 It is a construct adapted from physics and engineering, where it is employed to describe tension forces in solid bodies with an array of three-dimensional vectors.

The particular tensors used to describe diffusion can be further conceptualized and visualized as ellipsoids. The three main axes of the ellipsoid describe an orthogonal coordinate system. The directions of the main axes represent the so-called eigenvectors; their length, the so-called eigenvalues of the tensor. In DTI, a tensor that describes diffusion in all spatial directions is calculated for each voxel. The longest main axis of the diffusion ellipsoid represents the value and the direction of maximum diffusion, whereas the shortest axis represents the value and direction of minimum diffusion. If the three eigenvalues are equal, then the diffusion is said to be isotropic, and the diffusion tensor can be visualized as a sphere. If they are unequal, then the diffusion is said to be anisotropic, and the diffusion tensor can be visualized more as an ellipsoid, as would be the case for myelin sheaths (see Figure 1). To estimate the diffusion tensor, at least six measurements (taken from different gradient directions) are needed, in addition to the baseline image data.

White matter fiber tracts consist of a large number of densely packed myelinated axons. Because the movement of water molecules within this myelinated white matter is substantially restricted perpendicular to the longitudinal axes of the axons, the longest main axis of the diffusion ellipsoid is much larger than the other two and coincides with the direction of the fibers. Following Westin and colleagues' geometric classification of the diffusion tensor using linear, planar, and spherical measures,12 this type of anisotropically restricted diffusion is termed “linear diffusion.” “Planar diffusion” refers to diffusion restricted in one direction only and unrestricted in the other two—for example, between layers of tissue.

The above-mentioned basic ellipsoid model is idealized and does not necessarily reflect the true diffusion behavior encountered in real tissues. For example, at nerve-fiber-tract crossings, the ellipsoid tensor model fails, since each fiber tract registers a principal direction of diffusion. Acquisition protocols that measure diffusion in a large number of directions allow for a better description of the complex directional diffusion behavior at fiber-tract crossings and in other heterogeneously organized tissue structures.

Data from DTI can be analyzed in several ways. The most general approach is to characterize the overall displacement of the molecules (average ellipsoid size) by determining mean diffusivity. To do so, the trace of the diffusion tensor,4 which is calculated as the sum of the eigenvalues of the tensor, is employed. This sum is divided by three to calculate mean diffusivity.

Several measures have been introduced to describe anisotropic diffusion. To be useful, such measures must be independent of the orientation of the diffusion ellipsoid and thus provide information relevant to the specific tissue type. The most commonly used measures, proposed by Basser and Pierpaoli,13 are relative anisotropy (RA), a normalized standard deviation representing the ratio of the anisotropic part of the tensor to its isotropic part; fractional anisotropy (FA), a measure of the fraction of the magnitude of the tensor that can be ascribed to the anisotropic diffusion; and volume ratio, a measure representing the ratio of the ellipsoid volume to the volume as a sphere of radius l. These and other anisotropy indices are summarized in Table 1. Such indices measure the diffusion within each voxel (intravoxel diffusion) separately. A second type of anisotropy measure has been introduced to describe the intervoxel coherence of the tensors in the neighboring voxels. The latter measures, summarized in Table 2, better reflect fiber organization and orientation at the macroscopic level.

TABLE 1. Anisotropy Indices Used in Clinical Studies.

| Index | Study | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Anisotropy minor, anisotropy major | Shimony et al.77 | Measures describing the variation in ellipsoid shape along the major and minor axes |

| Eccentricity | Tievsky et al.41 | Measure describing the ellipsoid nature of the principal and minor axes with reference to a sphere |

| Fractional anisotropy | Basser & Pierpaoli13 | Measure of the fraction of the magnitude of the tensor that can be ascribed to anisotropic diffusion |

| Geometric measures of anisotropy | Westin et al.78 | Measures classifying the ellipsoid's closeness to a line, a plane, or a sphere (linear, planar, or spherical diffusion) |

| Gamma variate anisotropy | Armitage & Bastin79 | A measure formulated in relation to noise (less sensitive to noise than other anisotropy indices) |

| Relative anisotropy | Basser & Pierpaoli13 | Normalized standard deviation representing the ratio of the anisotropic portion of the tensor to its isotropic portion |

| Total anisotropy | Shimony et al.77 | Coefficient of variation determined on the basis of the second moment (variance) of diffusion; similar to relative anisotropy except for a scaling factor of 2½, which places total anisotropy on the absolute anisotropy scale |

| Ultimate anisotropy | Ulug & Van Zihl76 | Ratio of the diffusion ellipsoid's volume to its surface area; does not require tensor diagonalization (as opposed to relative and fractional anisotropy, which do) |

| Volume ratio | Basser & Pierpaoli13 | Measure representing the ratio of the ellipsoid volume to the volume as a sphere with a radius of 1 |

TABLE 2. Intervoxel Diffusion Indices Describing Local Coherence between Tensors.

| Index | Study | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Correlation measure of organization | Basser & Pierpaoli13 | A measure assessed by applying the convolution averaging procedure, weighting the scalar matrix products in neighboring voxels more heavily than those in distant ones |

| Geometric measures of weighted average tensor | Westin et al.12 | Measures obtained by locally averaging the tensors with a low-pass filter and applying Westin's geometric measures |

| Intervoxel coherence | Pfefferbaum et al.50 | A measure obtained by averaging the angle between the eigenvector of the largest eigenvalue of a given voxel and those of its eight neighbors |

| Lattice index of anisotropy | Pierpaoli & Basser16 | A measure that averages diffusion tensors in neighboring voxels, decreasing the bias and variance of estimated diffusion anisotropy |

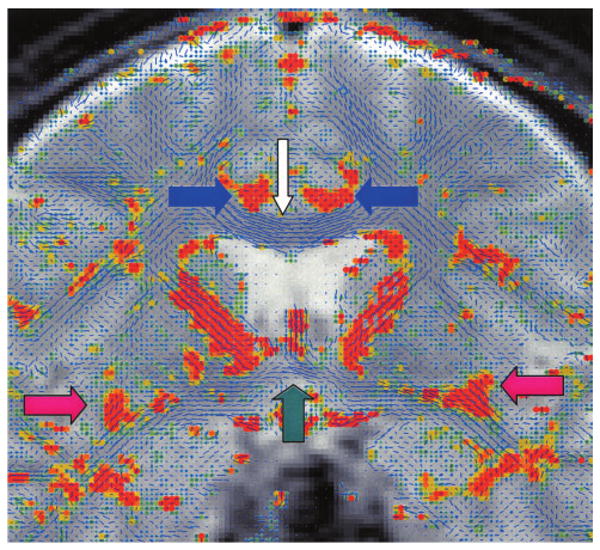

Like quantifying diffusion tensor anisotropy, displaying tensors in three dimensions also poses a problem. Several methods have been proposed for visualizing the three-dimensional information contained in DTI data. These include using the octahedra in each pixel;14 color maps,15 where different intensities of the three colors indicate the size and the ADC in each of the three Cartesian directions;16 and blue lines to represent the in-plane component of the principal diffusion direction, along with a color-coded out-of-plane component17 (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Visualization of diffusion tensors. The blue lines represent the in-plane component of the principal diffusion direction; the other colors show the magnitude of the out-of-plane component, with orange/red indicating maximal diffusion. The white and green arrows point to the corpus callosum and the anterior commissure, respectively, two major fiber tracts with the largest in-plane diffusion component, while the blue and pink arrows indicate the cingulate and uncinate fasciculi, fibers with the biggest out-of-plane diffusion component.

Clinical Applications in Neuropsychiatric Disorders

The phenomenon of restricted diffusion is of particular interest to studies that evaluate the integrity of white matter fiber tracts, as noted above. Based on geometry and the degree of anisotropy loss, white matter tract pathology, such as dislocation, swelling, infiltration, and disruption, can be documented. In addition, the cross-sectional sizes of these pathways yield a quantitative measure of connectivity between different brain regions. For example, disruptions in connectivity—and, in some cases, subsequent reorganization of nerve pathways—resulting from physical trauma or ischemia, brain tumor, multiple sclerosis (MS), infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), schizophrenia, or degenerative or metabolic diseases might be visualized and quantified. A loss of connectivity between brain regions as measured by DTI could indicate developmental pathology, axonal damage, demyelination, and/or disruption of fiber tracts.

Brain ischemia

Evaluation of ischemia is one of the earliest, most important, and most widely used clinical applications of DWI. So far, DWI is the most sensitive in vivo method for detecting acute ischemia.18,19 It also allows for the distinction between old and new strokes19,20 and helps to differentiate early stroke from other focal brain processes mimicking stroke on conventional MRI.21,22 DWI studies23–25 show that diffusion parameters decrease in the acute stage, “pseudonormalize” in the subacute phase, and increase in the chronic stage of the stroke. Unfortunately, because DWI does not reflect the spatial organization of the fiber tracts, it fails to detect long-term white matter changes, either in the close vicinity of the lesion or remote from it.

DTI, on the other hand, is more sensitive to the organization and orientation of the fiber tracts, and research26 already shows better correlation between clinical status and anisotropy indices (e.g., diffusion anisotropy remains decreased in the subacute stage, even after diffusion coefficient normalization [between 1 and 3 weeks.]). DTI data are more sensitive to changes in fiber-tract organization (i.e., axonal loss, degeneration, or incomplete remyelination) following a stroke. Moreover, changes in anisotropy can be detected several months after the stroke—and within the fiber tracts remote from the stroke (e.g., in the corticospinal tract)—presumably marking fiber-tract degeneration (wallerian degeneration).27,28

A recent DTI study29 has also demonstrated that ischemic stroke damage in white matter occurs earlier and is more severe than previously inferred from DWI investigations. Table 3 summarizes all clinical DTI studies published through March 2002 on stroke and other neuropsychiatric conditions.

TABLE 3. Clinical Applications of Diffusion Tensor Imaging.

| Condition | Study | n (patients/controls) | Measure(s) | Findings* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke | Jones et al.80 | 9/10 | Tr, FA | Decrease in anisotropy, increase in diffusivity within the lacunar infarction |

| Sorenson et al.81 | 50/0 | FA, Tr, eigenvalues of the tensor | Reduction of anisotropy within white matter in acute cerebral stroke, attributable to changes in the first and second eigenvalues (aligned with the long axes of the white matter fiber tracts) | |

| Zelaya et al.26 | 6/0 | Tr, FA, LI | Monotonic and significant decrease in anisotropy measures within the ischemic lesion from the acute to the chronic stage | |

| Mukherjee et al.29 | 12/0 | Isotropic diffusion coefficient (similar to Tr), diffusion anisotropy | More-severe reduction in diffusion measures within white matter than within gray matter in acute to early subacute stroke | |

| Werring et al.27 | 5/0 | Tr, FA | Reduced anisotropy 6 mo after cerebral infarction within the corticospinal tract, remote from the lesion | |

| Pierpaoli et al.28 | 7/0 | Tr, FA, LI | Reduced anisotropy within the entire fiber tract affected by the lacunar infarction, due to wallerian degeneration | |

| Brain injury | Werring et al.32 | 1/5 | FA | Decreased anisotropy within the anterior limb of the internal capsule, which correlated with the functional motor deficits revealed by fMRI several months after the internal capsule focal brain injury |

| Wieshmann et al.33 | 1/0 | FA, Tr | Increased diffusivity in the right frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes, as well as reduced anisotropy in the right optic radiation and forceps occipitalis, in a patient with right frontotemporal brain injury suffering from impaired memory | |

| Jones et al.82 | 5/0 | Tr | Reduced diffusivity in the periphery of a cerebral contusion despite a negative MRI | |

| Brain tumor | Bastin et al.83 | 6/0 | Tr | After dexamethasone treatment, decrease in trace within tumor and surrounding edematous tissue |

| Wieshmann et al.34 | 1/20 | FA, Tr | Deviation of fibers in normal-appearing white matter adjacent to the tumor | |

| Mori et al.35 | 2/0 | 3-dimensional fiber tracking | Displacement of the fiber tracts in one patient; infiltration without displacement in another patient | |

| Focal epilepsy | Krakow et al.84 | 1/0 | FA, Tr | Reduced anisotropy, high diffusivity, and displacement of myelinated tracts due to a malformation of cortical development was detected in a patient with focal epilepsy |

| Rugg-Gunn et al.37 | 30/30 | FA, Tr | Increased diffusivity and reduced anisotropy were noted within the white matter of the left temporal lobe in subjects with electroclinical seizure onset localized to the left temporal lobe | |

| Eriksson et al.85 | 22/30 | FA, Tr | In patients with a malformation of cortical development, reduced anisotropy and increased diffusivity were observed beyond the malformed areas | |

| MS | Werring et al.86 | 6/6 | FA, Tr | In MS patients the highest diffusivity was seen in destructive lesions, whereas the greatest change in anisotropy was found in inflammatory lesions |

| Tievsky et al.41 | 12/0 | FA, RA, E | In acute lesions, plaque centers had high ADC with reduced anisotropy compared with rims, normal-appearing white matter, and chronic lesions | |

| Nusbaum et al.87 | 13/12 | Tr | In MS patients, mean whole-brain diffusivity was elevated | |

| Castriota-Scanderbeg et al.43 | 20/11 | D | Diffusivity was greater in lesions of patients with secondary progressive MS than in those of patients with relapsing-remitting MS | |

| Bammer et al.88 | 14/9 | Tr, FA | Diffusivity was slightly but significantly greater in normal-appearing white matter in MS patients than in the white matter of controls | |

| Filippi et al.42 | 78/20 | FA, D | Normal-appearing white matter of MS patients showed higher diffusivity and lower anisotropy than did white matter of controls | |

| Alzheimer's disease | Rose et al.57 | 11/9 | LI | Patients showed lower anisotropy in the association white matter fiber tracts, such as the splenium of the corpus callosum, the superior longitudinal fasciculus, and the cingulum, than did controls |

| Kantarci et al.58 | 19/55 | AI† | ADCs of the hippocampus and the temporal stem, posterior cingulate, occipital, and parietal white matter were higher in patients than in controls | |

| Schizophrenia | Buchsbaum et al.61 | 5/6 | RA | Patients showed lower anisotropy in the white matter of the prefrontal cortex than did controls |

| Lim et al.60 | 10/10 | FA, Tr | Anisotropy was lower in the white matter of patients than in that of controls | |

| Foong et al.62 | 20/25 | FA, Tr | Compared with controls, patients showed higher diffusivity and lower anisotropy in the splenium but not the genu of the corpus callosum | |

| Agartz et al.63 | 20/24 | FA, Tr | Patients showed lower anisotropy in the splenium of the corpus callosum as well as a higher diffusivity throughout the entire volume of white matter compared to controls | |

| Steel et al.89 | 10/10 | FA | No differences in anisotropy in prefrontal white matter were observed between controls and patients | |

| Kubicki et al.64 | 15/18 | FA | Diminished left/right asymmetry in anisotropy in the uncinate fasciculus was seen in patients compared to controls | |

| Other conditions affecting white matter | ||||

| HIV infection | Pomara et al.45 | 6/9 | FA, Tr, PD | Frontal lobe and internal capsule white matter showed decreased anisotropy in patients compared to controls |

| Filippi et al.46 | 10/0 | UA, Tr | Diffusivity decreased in the corpus callosum and increased in the subcortical frontal and parietal regions in patients with elevated viral load; no changes in patients taking antiretroviral drugs | |

| Krabbe's disease | Guo et al.44 | 8/8 | RA | Patients showed lower anisotropy in white matter than did controls; following treament, anisotropy increased but was still lower than in controls |

| Chronic alcohol dependence | Pfefferbaum et al.50 | 15/31 | FA, IC | Patients showed lower anisotropy and coherence in the corpus callosum than did controls; working memory and attention measures correlated positively with anisotropy |

| ALS | Ellis et al.47 | 22/20 | FA, Tr | Anisotropy correlated with disease severity and upper motor neuron involvement; diffusivity correlated with disease duration |

| Ulug et al.49 | 4/0 | UA | No decrease of anisotropy within the corticospinal tract was detectable on MRI | |

| X-linked ALD | Ito et al.90 | 11/0 | ADC, FA | Affected areas of the white matter showed lower anisotropy than did unaffected areas; follow-up studies revealed an increase of the affected area on the FA maps, attributable to loss of myelin-sheath integrity |

| CADASIL | Chabriat et al.48 | 16/10 | VR, Tr | Patients showed increased diffusivity and decreased anisotropy both in lesions and in normal-appearing white matter compared to controls; degree of abnormality correlated with clinical severity |

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; AI, anisotropy index; ALD, adrenoleukodystrophy; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CADASIL, cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy; D, averaged water diffusion coefficient; E, eccentricity; FA, fractional anisotropy; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IC, intervoxel coherence; LI, lattice index of anisotropy; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MS, multiple sclerosis; PD, proton density; RA, relative anisotropy; Tr, diffusion trace; UA, ultimate anisotropy; VR, volume ratio.

A11 findings reported are significant at p < 0.05.

A regional measure of the directionality of diffusion.

Traumatic brain injury

As with stroke, DWI has played a major role in the early detection of brain changes following traumatic injury. The early increase in ADC seen on DWI is usually attributable to vasogenic edema, whereas later decreases in ADC (despite ongoing increase of intracranial pressure) are usually attributable to cytotoxic edema,30 believed to play a major role in posttraumatic brain swelling.31

DTI allows a closer investigation of the specific fiber tracts affected, as well as the ability to monitor the degeneration process following injury. Specifically, DTI performed several months after an internal capsule focal brain injury32 demonstrated full recovery and preservation of the structural integrity and orientation in the posterior capsular limb and disrupted structure in the anterior limb on the injured side, which correlated with the functional motor deficits revealed by the functional MRI. Moreover, in another DTI study33 a patient who had right frontotemporal brain injury and impaired memory revealed increased diffusion traces in right frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes as well as diffusion changes in myelinated structures, including the right optic radiation and the forceps major of the corpus callosum, which corresponded with clinically predictable symptoms. These case studies suggest that DTI is a powerful new technology for investigating functional deficits caused by brain injury, as well as for predicting prognosis.

Brain tumors

DWI has not been particularly useful in brain tumor differentiation, although it is helpful in detecting the cystic components of tumors, early edema around the tumor, and ischemic lesions within the pathological mass. In contrast, DTI can be implemented for modeling fiber-tract disruptions or displacement caused by the tumor34,35 and could be useful for early detection of spine metastases, as well as for detection of corticospinal-tract disruptions or displacement.

Seizure disorders

Compared with its use in the detection and differentiation of early stroke from brain tumor, DWI has so far played only a minor role in routine interictal imaging. In rats, severe, acute focal damage (expressed in animals as cytotoxic edema, which causes a drop in diffusion) after prolonged induced seizures can be detected with DWI, especially within the amygdala and piriform cortex.35 These results have not been replicated in humans, presumably because they show a different mechanism of brain injury (vasogenic edema, which causes an increase in diffusion, coexists with the cytotoxic edema).

A few existing DTI studies already demonstrate higher sensitivity of DTI compared to structural MRI in detecting malformations of cortical development. Such malformations disturb the orientation of the fiber tracts and are a common cause of epilepsy. Rugg-Gunn and colleagues,37 for example, have shown that changes within the white matter of the left temporal lobe can be identified with DTI but not with structural MRI.

Other Conditions Affecting White Matter

DWI has been shown to be superior in detecting white matter abnormalities in MS—abnormalities that are not as readily observed in conventional structural MRI (“normal-appearing white matter”).38–40 It is hoped that DTI will be of even greater value in detecting fiber-tract alterations due to demyelination and axonal loss. DTI studies in patients with MS have shown an increase in mean diffusivity and a decrease in diffusion anisotropy within acute lesions,41 as well as within the normal-appearing white matter,42 most likely attributable to edema. In addition, DTI has been found to be useful in differentiating between two types of MS,43 secondary progressive and relapsing-remitting, which have different clinical courses.

Finally, DTI has demonstrated white matter fiber tract pathology in Krabbe's disease,44 HIV infection,45,46 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,47 cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy,48 leukoencephalopathy,49 and chronic alcohol dependence.50 In such studies, DTI was able to detect and quantify therapeutic responses to treatment that are believed to be the result of decreased edema during the acute phase of inflammation.44,46 The potential of DTI as an exploratory tool is suggested by a study of patients with chronic alcohol dependence50 that revealed a correlation between loss of working memory and attention and a decrease in diffusion anisotropy within the corpus callosum.

Alzheimer's disease

The early to moderate stages of Alzheimer's disease are characterized by impaired cognition with preserved mobility.51 Although the disease is believed mainly to affect gray matter, postmortem studies52,53 have revealed loss of axons and oligodendrocytes within the white matter as well. Of note, a recent DWI study54 has shown reduced diffusion within the splenium and body of the corpus callosum, findings consistent with previous reports of atrophy in the corpus callosum in patients with Alzheimer's disease.55,56 In addition, DTI studies conducted in the early stages of the disease57,58 have revealed significant connectivity disruptions within the association white matter fiber tracts, including the temporal stem (uncinate fasciculus), cingulate fasciculus, corpus callosum, and superior longitudinal fasciculus, as well as the hippocampus. Thus, DTI studies may improve our ability to track progressive changes in Alzheimer's disease and could possibly be used in the future to evaluate changes in response to treatment.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a disorder of unknown etiology. Although many subtle brain abnormalities have been observed in this disorder (see review in reference 59), no brain lesions have been definitively correlated with many of the functional deficits found in these patients. Of note, however, are several DTI reports of decreased diffusion anisotropy in the white matter of persons with schizophrenia. Loss of orientation and organization of fiber tracts has been detected in the whole white matter60 and in frontal white matter,61 but also in particular fiber tracts such as the corpus callosum62,63 and the uncinate fasciculus.64 Further DTI investigation of white matter fiber-tract abnormalities in schizophrenia may change how we view this disorder, particularly in providing access to in vivo developmental studies across time.

Other possible uses in psychiatric disorders

To date, there are no studies using DTI to investigate white matter abnormalities that have been reported in other psychiatric conditions. MRI has revealed white matter hyperintensities in deep and periventricular white matter in patients with affective disorders;65 it has also shown deep white matter lesions to be correlated with poor outcome in bipolar disorder66 and with degree of residual dysfunction following a severe episode of depression.67 MRI studies in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder have revealed nonspecific white matter lesions, as well as some functional deficits that might be attributed to the disconnection of specific cortical regions (i.e., the amygdala, Broca's region, and the cingulate cortex).68 Correlations between psychiatric symptoms and white matter lesions could be further evaluated using DTI. Such testing might be able to determine the specificity of the particular fiber tracts affected, as well as the extent of their involvement.

Developmental Studies

Developmental DTI studies are only just beginning. Investigation of normal and abnormal brain development, however, should lead to a better understanding of brain maturation. DWI has, in fact, already revealed greater water diffusion in neonates than in adults,69,70 and there is evidence to suggest that anisotropic diffusion is higher in full-term neonates than in preterm neonates,3 a difference most likely due to the myelination of white matter fiber tracts. Such findings suggest that diffusion-imaging techniques can detect an increase in myelination during normal development.

In addition, anisotropic diffusion has been observed to decline as a result of age-related degenerative processes involving white matter fibers and myelin sheaths.71 Whether this change is due to normal aging or pathological aging remains to be determined. Table 4 summarizes all neurodevelopmental studies utilizing DTI published through March 2002.

TABLE 4. Neurodevelopmental Studies Utilizing DTI.

| Study | n | Measure(s) | Findings* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hüppi et al.3 | 24 infants: 17 preterm, 7 full-term | Diffusivity, RA | Anisotropy was higher the closer birth was to term |

| Klingberg et al.91 | 7 children, 5 adults | FA, Tr | Anisotropy in frontal white matter was lower in children than in adults |

| Pfefferbaum et al.71 | 31 healthy men, ages 23–76 y | Diffusivity, FA, IC | Anisotropy declined with age in all regions except the splenium of the corpus callosum |

| Nusbaum et al.92 | 20 healthy volunteers, ages 20–91 y | RA, diffusivity histograms | Anisotropy decreased significantly with increasing age in periventricular white matter, frontal white matter, and the genu and splenium of the corpus callosum |

FA, fractional anisotropy; IC, intervoxel coherence; RA, relative anisotropy; Tr, diffusion trace.

All findings reported are significant at p ≤ 0.05.

Diffusion imaging offers the opportunity to evaluate both normal and pathological changes in white matter and brain connectivity over the life span. Such changes may be important for understanding not only normal development but also differences in cognitive abilities over time.

Future Applications

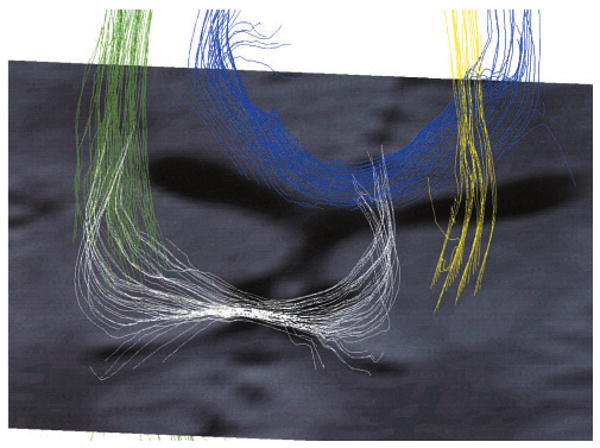

Potential future applications of DTI include visualization of the anatomical connections among different parts of the brain. Diffusion tensor tractography (see Figure 3), proposed by several authors,72–75 uses the principal diffusion direction measured with DTI to compute the pathways of complete nerve fiber tracts. The tracing is performed by first defining regions of interest. Then, starting from points (“seed points”) selected within this region and following the spatially interpolated direction of maximum diffusion in neighboring voxels, the path of fibers within a fiber tract is defined. Such tracking, which is done repetitively with multiple seed points, creates a contiguous path that defines the fiber tract of interest.

FIGURE 3.

Three-dimensional tractography of a normal subject, showing the anterior (white) and posterior (blue) portions of the corpus callosum as well as the left and right (yellow and green) corticospinal tracts. These tracts pass through an axial section of the lateral ventricles.

Visualization is then performed in three dimensions to depict the white matter fiber tract. Progressing from an examination of anisotropy to a more elaborate analysis of the relationship between neighboring diffusion ellipsoids opens the possibility for assessing, in vivo, axonal fiber connectivity and functional links among brain regions.

A slightly different approach to tensor tractography, described by Westin and colleagues,14 attempts to reduce problems encountered when tracing fibers in complex regions (such as where fiber tracts merge, branch, or cross within a voxel) by defining the direction of the trace path in a novel way. Rather than following the direction of the maximum diffusivity (the direction of the major axis of the diffusion ellipsoid), this approach “bends” the trace with a strong bias toward this direction. Another approach regularizes the trace path based on its curvature—that is, fixes the curve according to a predefined parameter.

Diffusion tensor tractography, combined with information from conventional and functional MR imaging, can provide a powerful tool for neurosurgical planning, especially when surgery occurs in the vicinity of vital nerve fiber tracts. Tracing and mapping the passage of functionally relevant fiber tracts along the tumors is as important as mapping cortical functions adjacent to tumors. The information gathered with these complementary techniques helps the neurosurgeon to decide where tumor tissue can be excised without permanent neurological consequences.

In addition, DTI, as mentioned above, can be used to follow up surgical and neurological treatment (by assessing the regeneration and/or remyelination of the affected fiber tracts), as well as to monitor the effects of medication. Finally, in disorders such as schizophrenia, where gross brain abnormalities are not evident, DTI may offer an opportunity to evaluate subtle changes in white matter fiber tracts that are related to neurocognitive abnormalities observed in this disorder. Such information might further our knowledge of brain-connectivity abnormalities and lead to more-targeted pharmacological treatments as well as to a better understanding of brain-behavior links in this devastating disorder.

In summary, DTI has opened up new research possibilities in areas that previously relied largely upon postmortem studies. For the first time, the intricate connective architecture of the most complex human organ can be studied noninvasively. Other potentially important applications for this technique, such as characterization of cardiac muscle tissue architecture, diagnosis of liver disease, mapping of tissue temperature, and diffusion spectroscopy, are beyond the scope of this article. It is clear that DTI could revolutionize what is known in many different domains of medicine and disease. The ability to visualize white matter fiber tracts in the human brain, in vivo, will likely be critical to a new understanding of brain structure and function, both in normal individuals and in those with a neuropsychiatric disorder.

The authors would like to thank Marie Fairbanks for her administrative assistance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (Drs. Kubicki and Frumin), the Grable Foundation (Dr. Kubicki), the National Institutes of Health (K02 MH 01110 and R01 MH 50747 to Dr. Shenton, R01 NS 39335 to Dr. Maier, R01 MH 40799 to Dr. McCarley), and the National Center for Research Resources (R01 RR 11747 to Dr. Kikinis, P41 RR 13218 to Drs. Jolesz and Westin); Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Awards (Drs. Shenton and McCarley); and a VA Psychiatry/Neuroscience Research Fellowship Award (Dr. Frumin).

Footnotes

It was long thought that Brown observed the movement of pollen grains suspended in water. Many now believe that he observed the movement of particles suspended within the grains of pollen. See, for example, BJ Ford, Brownian movement in Clarkia pollen: a reprise of the first observations. The Microscope 1992;40:235–41 (available on the World Wide Web at: http://www.sciences.demon.co.uk/wbbrowna.htm).

References

- 1.Beaulieu C, Allen PS. Determinants of anisotropic water diffusion in nerves. Magn Reson Med. 1994;31:394–400. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910310408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wimberger DM, Roberts TP, Barkovich AJ, Prayer LM, Moseley ME, Kucharczyk J. Identification of “premyelination” by diffusion-weighted MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1995;19:28–33. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199501000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hüppi PS, Maier SE, Peled S, Zientara GP, Barnes PD, Jolesz FA, et al. Microstructural development of human newborn cerebral white matter assessed in vivo by diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging. Pediatr Res. 1998;44:584–90. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199810000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, Grenier P, Cabanis E, Laval-Jeantet M. MR imaging of intravoxel incoherent motions: application to diffusion and perfusion in neurologic disorders. Radiology. 1986;161:401–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.161.2.3763909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierpaoli C, Jezzard P, Basser PJ, Barnett A, Di Chiro G. Diffusion tensor MR imaging of the human brain. Radiology. 1996;201:637–48. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basser PJ, Mattiello J, Le Bihan D. MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophys J. 1994;66:259–67. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80775-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner R, Le Bihan D, Maier J, Vavrek R, Hedges LK, Pekar J. Echo-planar imaging of intravoxel incoherent motion. Radiology. 1990;177:407–14. doi: 10.1148/radiology.177.2.2217777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ordidge RJ, Helpern JA, Qing ZX, Knight RA, Nagesh V. Correction of motional artifacts in diffusion-weighted MR images using navigator echoes. Magn Reson Imaging. 1994;12:455–60. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(94)92539-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trouard TP, Theilmann RJ, Altbach MI, Gmitro AF. High-resolution diffusion imaging with DIFRAD-FSE (diffusion-weighted radial acquisition of data with fast spin-echo) MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:11–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199907)42:1<11::aid-mrm3>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maier SE, Gudbjartsson H, Patz S, Hsu L, Lovblad KO, Edelman RR, et al. Line scan diffusion imaging: characterization in healthy subjects and stroke patients. Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:85–93. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.1.9648769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maier SE. Slab scan diffusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:1136–43. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westin CF, Maier SE, Mamata H, Nabavi A, Jolesz FA, Kikinis R. Processing and visualization for diffusion tensor MRI. Med Image Anal. 2002;6:93–108. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(02)00053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basser PJ, Pierpaoli C. Microstructural and physiological features of tissues elucidated by quantitative-diffusion-tensor MRI. J Magn Reson B. 1996;111:209–19. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reese TG, Weisskoff RM, Smith RN, Rosen BR, Dinsmore RE, Wedeen VJ. Imaging myocardial fiber architecture in vivo with magnetic resonance. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:786–91. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makris N, Worth AJ, Sorensen AG, Papadimitriou GM, Wu O, Reese TG, et al. Morphometry of in vivo human white matter association pathways with diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:951–62. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierpaoli C, Basser PJ. Toward a quantitative assessment of diffusion anisotropy. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:893–906. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peled S, Gudbjartsson H, Westin CF, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA. Magnetic resonance imaging shows orientation and asymmetry of white matter fiber tracts. Brain Res. 1998;780:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00635-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moseley ME, Cohen Y, Mintorovitch J, Chileuitt L, Shimizu H, Kucharczyk J, et al. Early detection of regional cerebral ischemia in cats: comparison of diffusion- and T2-weighted MRI and spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 1990;14:330–46. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910140218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warach S, Chien D, Li W, Ronthal M, Edelman RR. Fast magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted imaging of acute human stroke. Neurology. 1992;42:1717–23. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.9.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warach S, Gaa J, Siewert B, Wielopolski P, Edelman RR. Acute human stroke studied by whole brain echo planar diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:231–41. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuruda JS, Chew WM, Moseley ME, Norman D. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the brain: value of differentiating between extraaxial cysts and epidermoid tumors. Am J Roentgenol. 1990;155:1059–65. doi: 10.2214/ajr.155.5.2120936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hajnal JV, Doran M, Hall AS, Collins AG, Oatridge A, Pennock JM, et al. MR imaging of anisotropically restricted diffusion of water in the nervous system: technical, anatomic, and pathologic considerations. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1991;15:1–18. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199101000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chien D, Kwong KK, Gress DR, Buonanno FS, Buxton RB, Rosen BR. MR diffusion imaging of cerebral infarction in humans. Am J Neuroradiol. 1992;13:1097–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warach S, Dashe JF, Edelman RR. Clinical outcome in ischemic stroke predicted by early diffusion-weighted and perfusion magnetic resonance imaging: a preliminary analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:53–9. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rother J, De Crespigny AJ, D'Arceuil H, Iwai K, Moseley ME. Recovery of apparent diffusion coefficient after ischemia-induced spreading depression relates to cerebral perfusion gradient. Stroke. 1996;27:980–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.5.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zelaya F, Flood N, Chalk JB, Wang D, Doddrell DM, Strugnell W, et al. An evaluation of the time dependence of the anisotropy of the water diffusion tensor in acute human ischemia. Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;17:331–48. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(98)00192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Werring DJ, Toosy AT, Clark CA, Parker GJ, Barker GJ, Miller DH, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging can detect and quantify corticospinal tract degeneration after stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:269–72. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierpaoli C, Barnett A, Pajevic S, Chen R, Penix LR, Virta A, et al. Water diffusion changes in wallerian degeneration and their dependence on white matter architecture. Neuroimage. 2001;13:1174–85. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukherjee P, Bahn MM, McKinstry RC, Shimony JS, Cull TS, Akbudak E, et al. Differences between gray matter and white matter water diffusion in stroke: diffusion-tensor MR imaging in 12 patients. Radiology. 2000;215:211–20. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.1.r00ap29211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito J, Marmarou A, Barzo P, Fatouros P, Corwin F. Characterization of edema by diffusion-weighted imaging in experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:97–103. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.1.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barzo P, Marmarou A, Fatouros P, Hayasaki K, Corwin F. Contribution of vasogenic and cellular edema to traumatic brain swelling measured by diffusion-weighted imaging. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:900–7. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.6.0900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Werring DJ, Clark CA, Barker GJ, Miller DH, Parker GJ, Brammer MJ, et al. The structural and functional mechanisms of motor recovery: complementary use of diffusion tensor and functional magnetic resonance imaging in a traumatic injury of the internal capsule. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:863–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.6.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wieshmann UC, Symms MR, Clark CA, Lemieux L, Parker GJ, Barker GJ, et al. Blunt-head trauma associated with widespread water-diffusion changes. Lancet. 1999;353:1242–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)00248-2. Letter. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wieshmann UC, Symms MR, Parker GJ, Clark CA, Lemieux L, Barker GJ, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging demonstrates deviation of fibres in normal appearing white matter adjacent to a brain tumour. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:501–3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.4.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mori S, Frederiksen K, Van Zijl PC, Stieltjes B, Kraut MA, Solaiyappan M, et al. Brain white matter anatomy of tumor patients evaluated with diffusion tensor imaging. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:377–80. doi: 10.1002/ana.10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lynch MW, Rutecki PA, Sutula TP. The effects of seizures on the brain. Curr Opin Neurol. 1996;9:97–102. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199604000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rugg-Gunn FJ, Eriksson SH, Symms MR, Barker GJ, Duncan JS. Diffusion tensor imaging of cryptogenic and acquired partial epilepsies. Brain. 2001;124:627–36. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christiansen P, Gideon P, Thomsen C, Stubgaard M, Henriksen O, Larsson HB. Increased water self-diffusion in chronic plaques and in apparently normal white matter in patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1993;87:195–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1993.tb04100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Droogan AG, Clark CA, Werring DJ, Barker GJ, McDonald WI, Miller DH. Comparison of multiple sclerosis clinical subgroups using navigated spin echo diffusion-weighted imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;17:653–61. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(99)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cercignani M, Iannucci G, Rocca MA, Comi G, Horsfield MA, Filippi M. Pathologic damage in MS assessed by diffusion-weighted and magnetization transfer MRI. Neurology. 2000;54:1139–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.5.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tievsky AL, Ptak T, Farkas J. Investigation of apparent diffusion coefficient and diffusion tensor anisotropy in acute and chronic multiple sclerosis lesions. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:1491–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Filippi M, Cercignani M, Inglese M, Horsfield MA, Comi G. Diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2001;56:304–11. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.3.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castriota-Scanderbeg A, Tomaiuolo F, Sabatini U, Nocentini R, Grasso MG, Caltagirone C. Demyelinating plaques in relapsing-remitting and secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis: assessment with diffusion MR imaging. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:862–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo AC, Petrella JR, Kurtzberg J, Provenzale JM. Evaluation of white matter anisotropy in Krabbe disease with diffusion tensor MR imaging: initial experience. Radiology. 2001;218:809–15. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.3.r01mr14809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pomara N, Crandall DT, Choi SJ, Johnson G, Lim KO. White matter abnormalities in HIV-1 infection: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Psychiatry Res. 2001;106:15–24. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(00)00082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Filippi CG, Ulug AM, Ryan E, Ferrando SJ, Van Gorp W. Diffusion tensor imaging of patients with HIV and normal-appearing white matter on MR images of the brain. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:277–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ellis CM, Simmons A, Jones DK, Bland J, Dawson JM, Horsfield MA, et al. Diffusion tensor MRI assesses corticospinal tract damage in ALS. Neurology. 1999;53:1051–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.5.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chabriat H, Pappata S, Poupon C, Clark CA, Vahedi K, Poupon F, et al. Clinical severity in CADASIL related to ultrastructural damage in white matter: in vivo study with diffusion tensor MRI. Stroke. 1999;30:2637–43. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.12.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ulug AM, Moore DF, Bojko AS, Zimmerman RD. Clinical use of diffusion-tensor imaging for diseases causing neuronal and axonal damage. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:1044–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV, Hedehus M, Adalsteinsson E, Lim KO, Moseley M. In vivo detection and functional correlates of white matter microstructural disruption in chronic alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1214–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldman WP, Baty JD, Buckles VD, Sahrmann S, Morris JC. Motor dysfunction in mildly demented AD individuals without extrapyramidal signs. Neurology. 1999;53:956–62. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.5.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brun A, Englund E. A white matter disorder in dementia of the Alzheimer type: a pathoanatomical study. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:253–62. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Englund E. Neuropathology of white matter changes in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1998;9(suppl 1):6–12. doi: 10.1159/000051183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hanyu H, Asano T, Sakurai H, Imon Y, Iwamoto T, Takasaki M, et al. Diffusion-weighted and magnetization transfer imaging of the corpus callosum in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Sci. 1999;167:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weis S, Jellinger K, Wenger E. Morphometry of the corpus callosum in normal aging and Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1991;33:35–8. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9135-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Janowsky JS, Kaye JA, Carper RA. Atrophy of the corpus callosum in Alzheimer's disease versus healthy aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:798–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb03736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rose SE, Chen F, Chalk JB, Zelaya FO, Strugnell WE, Benson M, et al. Loss of connectivity in Alzheimer's disease: an evaluation of white matter tract integrity with colour coded MR diffusion tensor imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:528–30. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.4.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kantarci K, Jack CR, Jr, Xu YC, Campeau NG, O'Brien PC, Smith GE, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease: regional diffusivity of water. Radiology. 2001;219:101–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.1.r01ap14101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shenton ME, Dickey CC, Frumin M, McCarley RW. A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;49:1–52. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lim KO, Hedehus M, Moseley M, De Crespigny A, Sullivan EV, Pfefferbaum A. Compromised white matter tract integrity in schizophrenia inferred from diffusion tensor imaging. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:367–74. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Buchsbaum MS, Tang CY, Peled S, Gudbjartsson H, Lu D, Hazlett EA, et al. MRI white matter diffusion anisotropy and PET metabolic rate in schizophrenia. Neuroreport. 1998;9:425–30. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199802160-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Foong J, Maier M, Clark CA, Barker GJ, Miller DH, Ron MA. Neuropathological abnormalities of the corpus callosum in schizophrenia: a diffusion tensor imaging study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:242–4. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.2.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Agartz I, Andersson JL, Skare S. Abnormal brain white matter in schizophrenia: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neuroreport. 2001;12:2251–4. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200107200-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kubicki M, Westin CF, Maier S, Frumin M, Nestor PG, Salisbury DF, et al. Uncinate fasciculus findings in schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:813–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Altshuler LL, Curran JG, Hauser P, Mintz J, Denicoff K, Post R. T2 hyperintensities in bipolar disorder: magnetic resonance imaging comparison and literature meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1139–44. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.8.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moore PB, Shepherd DJ, Eccleston D, Macmillan IC, Goswami U, McAllister VL, et al. Cerebral white matter lesions in bipolar affective disorder: relationship to outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:172–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hickie I, Scott E, Wilhelm K, Brodaty H. Subcortical hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging in patients with severe depression—a longitudinal evaluation. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;42:367–74. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00363-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pitman RK, Shin LM, Rauch SL. Investigating the pathogenesis of posttraumatic stress disorder with neuroimaging. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 17):47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sakuma H, Nomura Y, Takeda K, Tagami T, Nakagawa T, Tamagawa Y, et al. Adult and neonatal human brain: diffusional anisotropy and myelination with diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Radiology. 1991;180:229–33. doi: 10.1148/radiology.180.1.2052700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neil JJ, Shiran SI, McKinstry RC, Schefft GL, Snyder AZ, Almli CR, et al. Normal brain in human newborns: apparent diffusion coefficient and diffusion anisotropy measured by using diffusion tensor MR imaging. Radiology. 1998;209:57–66. doi: 10.1148/radiology.209.1.9769812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV, Hedehus M, Lim KO, Adalsteinsson E, Moseley M. Age-related decline in brain white matter anisotropy measured with spatially corrected echo-planar diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:259–68. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200008)44:2<259::aid-mrm13>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Poupon C, Clark CA, Frouin V, Régis J, Bloch I, Le Bihan D, et al. Regularization of diffusion-based direction maps for the tracking of brain white matter fascicles. Neuroimage. 2000;12:184–95. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Poupon C, Mangin J, Clark CA, Frouin V, Régis J, Le Bihan D, et al. Towards inference of human brain connectivity from MR diffusion tensor data. Med Image Anal. 2001;5:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(00)00030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wiegell MR, Larsson HB, Wedeen VJ. Fiber crossing in human brain depicted with diffusion tensor MR imaging. Radiology. 2000;217:897–903. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.3.r00nv43897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Basser PJ, Pajevic S, Pierpaoli C, Duda J, Aldroubi A. In vivo fiber tractography using DT-MRI data. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:625–32. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200010)44:4<625::aid-mrm17>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ulug AM, Van Zihl PC. Orientation-independent diffusion imaging without tensor diagonalization: anisotropy definitions based on physical attributes of the diffusion ellipsoid. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;9:804–13. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199906)9:6<804::aid-jmri7>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shimony JS, McKinstry RC, Akbudak E, Aronovitz JA, Snyder AZ, Lori NF, et al. Quantitative diffusion-tensor anisotropy brain MR imaging: normative human data and anatomic analysis. Radiology. 1999;212:770–84. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.3.r99au51770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Westin CF, Peled S, Gudbjartsson H, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA. Geometrical diffusion measures from tensor basis analysis. Proceedings of the Fifth Scientific Meeting of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; Vancouver, British Columbia. April 1997; p. 1742. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Armitage PA, Bastin ME. Selecting an appropriate anisotropy index for displaying diffusion tensor imaging data with improved contrast and sensitivity. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:117–21. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200007)44:1<117::aid-mrm17>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jones DK, Lythgoe D, Horsfield MA, Simmons A, Williams SC, Markus HS. Characterization of white matter damage in ischemic leukoaraiosis with diffusion tensor MRI. Stroke. 1999;30:393–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.2.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sorensen AG, Wu O, Copen WA, Davis TL, Gonzalez RG, Koroshetz WJ, et al. Human acute cerebral ischemia: detection of changes in water diffusion anisotropy by using MR imaging. Radiology. 1999;212:785–92. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.3.r99se24785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jones DK, Dardis R, Ervine M, Horsfield MA, Jeffree M, Simmons A, et al. Cluster analysis of diffusion tensor magnetic resonance images in human head injury. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:306–13. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200008000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bastin ME, Delgado M, Whittle IR, Cannon J, Wardlaw JM. The use of diffusion tensor imaging in quantifying the effect of dexamethasone on brain tumours. Neuroreport. 1999;10:1385–91. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199905140-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Krakow K, Wieshmann UC, Woermann FG, Symms MR, McLean MA, Lemieux L, et al. Multimodal MR imaging: functional, diffusion tensor, and chemical shift imaging in a patient with localization-related epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1999;40:1459–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb02021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eriksson SH, Rugg-Gunn FJ, Symms MR, Barker GJ, Duncan JS. Diffusion tensor imaging in patients with epilepsy and malformations of cortical development. Brain. 2001;124:617–26. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.3.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Werring DJ, Clark CA, Barker GJ, Thompson AJ, Miller DH. Diffusion tensor imaging of lesions and normal-appearing white matter in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1999;52:1626–32. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.8.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nusbaum AO, Tang CY, Wei T, Buchsbaum MS, Atlas SW. Whole-brain diffusion MR histograms differ between MS subtypes. Neurology. 2000;54:1421–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.7.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bammer R, Augustin M, Strasser-Fuchs S, Seifert T, Kapeller P, Stollberger R, et al. Magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging for characterizing diffuse and focal white matter abnormalities in multiple sclerosis. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:583–91. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200010)44:4<583::aid-mrm12>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Steel RM, Bastin ME, McConnell S, Marshall I, Cunningham-Owens DG, Lawrie SM, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) in schizophrenic subjects and normal controls. Psychiatry Res. 2001;106:161–70. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(01)00080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ito R, Melhem ER, Mori S, Eichler FS, Raymond GV, Moser HW. Diffusion tensor brain MR imaging in X-linked cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy. Neurology. 2001;56:544–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Klingberg T, Vaidya CJ, Gabrieli JD, Moseley ME, Hedehus M. Myelination and organization of the frontal white matter in children: a diffusion tensor MRI study. Neuroreport. 1999;10:2817–21. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199909090-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nusbaum AO, Tang CY, Buchsbaum MS, Wei TC, Atlas SW. Regional and global changes in cerebral diffusion with normal aging. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:136–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]