Abstract

The aim of this study was to estimate the acute effects of low dose 12C6+ ions or X-ray radiation on human immune function. The human peripheral blood lymphocytes (HPBL) of seven healthy donors were exposed to 0.05Gy 12C6+ ions or X-ray radiation and cell responses were measured at 24 hours after exposure. The cytotoxic activities of HPBL were determined by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT); the percentages of T and NK cells subsets were detected by flow cytometry; mRNA expression of interleukin (IL)-2, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interferon (IFN)-γ were examined by real time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR); and these cytokines protein levels in supernatant of cultured cells were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). The results showed that the cytotoxic activity of HPBL, mRNA expression of IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF-α in HPBL and their protein levels in supernatant were significantly increased at 24 hours after exposure to 0.05Gy 12C6+ ions radiation and the effects were stronger than observed for X-ray exposure. However, there was no significant change in the percentage of T and NK cells subsets of HPBL. These results suggested that 0.05Gy high linear energy transfer (LET) 12C6+ radiation was a more effective approach to host immune enhancement than that of low LET X-ray. We conclude that cytokines production might be used as sensitive indicators of acute response to LDI.

1. Introduction

Understanding the biological effects of accelerated heavy-ion would enable us to estimate biological influences of the space environment, because this type of radiation can be considered an important component of cosmic rays. Heavy-ion beams are generally characterized by a high linear energy transfer (LET), an energy deposition peak (Bragg peak) at the end of their tracks, and an increased relative biological effectiveness (RBE) within the peak region (Gerlach et al., 2002). However, the biological influence of heavy ions on normal cells is unclear.

Conventional lymphocytes are hypersensitive to irradiation, even in the case of low dose irradiation (Ren et al., 2006). The percentage of subgroups of T and NK cells in human peripheral blood lymphocytes (HPBL) is used as an indicator of function status of human immune system in clinic. Production of cytokines such as IL-2, TNF-α and IFN-γ has been suggested to play an important role in host immune defense against infection and cancer (Smith et al., 1988; Young and Hardy., 1990; Dinarello, 1996; Luster et al., 1999). Therefore, examining the levels of T and NK subgroups of lymphocytes and cytokines can not only be used to design and direct immunotherapy, but can also be used for predicting and evaluating the efficacy of low dose irradiation (LDI).

Radiation hormesis, the notion that chronic low doses of ionizing radiation are beneficial, by stimulating repair mechanisms that protect against disease, has become a hot point of research in radiobiology in recent years (Olivieri et al., 1984; Shadley and Wolff, 1987; Sagan and Cohen, 1990; Wang et al., 1991; Calabrese and Baldwin, 2000; Pollycove and Feinendegen, 2003; Rattan, 2004; Zhou et al., 2004). Experimental studies on animals have indicated a clear stimulatory effect of low dose irradiation (LDI) on the immune system of rodents (Hashimoto et al., 1999) and primates (Keller et al., 1982). For example, Galdiero M et al. reported that LDI could bring about hormesis effects in the immune system through alterations of cytokine release, by activating of IFN-γ and IL-2 (Galdiero et al., 1994). Most of these experimental studies have been performed using X-ray or γ-ray. However, for high linear energy transfer (LET) radiation, experimental data are scarce.

We have previously reported that low-dose 12C6+ irradiation has a stimulatory effect on mouse immunity, especially at a dose of 0.05Gy (Xie et al., 2007). Our own experimental animal study showed that low dose (0.05Gy) 12C6+ ions irradiation could induce adaptive hormetic responses to the harmful effects on the pituitary by subsequent high-dose exposure, and have greater RBE value than low LET radiation (60Co γ-ray) (Zhang et al., 2006). However, there is no human data available. As such, we conducted a study to investigate the relationship between low dose irradiation and human immune function, and to examine the differences of hormesis effects in human immune system induced by low dose irradiation between heavy ion beams and X-ray.

In this experiment, we investigated the acute response of immune cells to irradiation to evaluate potential changes in human immune system as might occur during space travel, including the changes in the percentage of various subsets of T lymphocytes and NK cells, mRNA expression of IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF-α in human peripheral blood lymphocytes (HPBL), protein levels of these cytokines in supernatant, and cytotoxic activity of HPBL.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Isolation of HPBL

After obtaining informed consent, blood samples were drawn from seven healthy volunteers (four male, three female; Age: 29.8±3.56 years), without a reported history of exposure to ionizing radiation or clastogenic chemicals, using vacuum tubes with heparin (Beijing Shuanghe Medicine Co. Ltd, Beijing, China). HPBL were isolated by the previously described method (Bellik et al., 2005). Briefly, HPBL were isolated from peripheral blood using a lymphocyte separation medium (LSM) (Shanghai Sangon Biological Engineering Technology and Service Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China) and density gradient centrifugation. The samples were then washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). All blood draws and HPBL isolation experiments were completed within 1.5 hours. Then HPBL were resuspended in RPMI 1640 (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) medium with HEPES supplemented with 10% fetal bovine medium, 2 mM L-glutamine, 200 IU of penicillin per ml, 150 mg of streptomycin per ml, and 50 mg of gentamycin per ml, resulting in a concentration of 107 cells per ml. HPBL from each donor were divided into three groups of equal number for subsequent irradiation treatment including sham, X-ray and 12C6+ irradiation. The total volume of HPBL before irradiation was 50ml for each group. HPBL were resuspended in Φ40 mm dish.

2.2 Targeting Cell line and culture conditions

The cell line was kept in liquid nitrogen at the Institute of Medical Science of Gansu Province (Lanzhou, China). A HepG2 line (human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line) was used in this study. The cell line was cultured at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere with RPMI 1640 (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine medium, 2 mM L-glutamine, 200 IU of penicillin per ml, 150 mg of streptomycin per ml, and 50 mg of gentamycin per ml.

2.3 Irradiation using heavy ion beams and X-ray

A carbon ion beam of 100 MeV/u was supplied by the Heavy Ion Research Facility in Lanzhou (HIRFL) at the Institute of Modern Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IMP-CAS). Cell exposures were conducted at the therapy terminal of the HIRFL, which has a vertical beam line. Due to the energy degradation by the vacuum window, air gap, Petri dish cover and medium, the energy of the ion beam on cell samples was calculated to be 89.63 MeV/u, corresponding to a LET of 28.3 keV/μm and the dose rate was adjusted to be about 0.5Gy/min. The ion beam was calibrated by absolute ionization chamber. The HPBL was irradiated by plateau of carbon ion LET curve. And the dose of scatter off the walls of the plate has been calculated and incorporated into the total dose. The acquisition of the data (preset numbers converted to absorbed dose of particle radiation) was automatically obtained using a microcomputer during irradiation.

Low-LET irradiations were performed using SIEMENS Primus High Energy Electron Linear Accelerator operated at 6MV and at a source to surface distance of 100 cm. The dose rate was approximately 0.5 Gy/min and the dose used for each irradiation (carbon-ion or X-ray) was 0, 0.05Gy. All irradiations were performed once for each dish of cells at room temperature on the same day.

2.4 Phenotype analysis

24 hours after radiation exposure, cells were obtained from HPBL cultures for phenotype analysis using appropriate monoclonal antibodies, including CD3-TC, CD3-FITC, CD4-FITC, CD8-PE, CD16-TC, CD56-PE (Caltag, Burlingame, CA, USA). T cells were detected by CD3-TC (Clone: S4.1), CD4-FITC (Clone: S3.5) and CD8-PE (Clone: 3B5) antibodies, NK cells by CD3-FITC (Clone: S4.1), CD16-TC (Clone: 3G8), CD56-PE (Clone: MEM-188) antibodies. All these antibodies were purchased from Caltag. One million HPBL were washed once in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and resuspended in 100ul of PBS buffer. The cells were incubated with various conjugated monoclonal antibodies for 20 min at 4° C, washed twice in PBS, and re-suspended in 400ul of PBS. A flow cytometric analysis was performed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (CoulterEPICS XL, USA) that is a three color flow, and the data were analyzed using the SYSTEM□statistical software. Forward and side scatter parameters were used to gate live cells (Han et al., 2005).

2.5 Isolation of RNA

Total RNA was extracted with a Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) from cells according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quality of total RNA was determined by Bioanalyzer (Petro, 2005).

2.6 Preparation of cDNA

Five micrograms of total RNA of each sample was reversed transcribed to cDNA using a PrimeScript™ reverse transcriptase kit (TaKaRa, Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.7 Analysis of mRNA expression by Real time quantitative RT-PCR

Real time quantitative RT–PCR analysis was performed using Rotor-Gene RG-3000 Real-Time sequence Detection System(Corbett Research, Australia). Reactions were carried out according to the manufacturer's protocol of the SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ kit (Perfect Real Time) (TaKaRa, Japan). Oligonucleotides were used as primers and predicted sizes of amplified PCR products and are listed in Table1. Using SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM kit (TaKaRa, Japan), the experiment was carried out in a final volume of 10ul of reaction mixture consisting of 5ul of SYBR Premix Ex Taq™, 0.4ul of the primers and 1ul cDNA according to the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was loaded into glass capillary tubes and subjected to an initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 rounds of amplification at 95°C for 10s for denaturation, 53°C for annealing, and 75°C for extension, with a temperature slope of 20°C/s, performed in the Rotor-Gene. The transcript amount for the genes differentially expressed was estimated from the respective standard curves and normalized to the β-actin transcript amount determined in corresponding samples.

Table 1.

Primers used for qRT-PCR

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Size(bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-2 | 5′-AACTCACCAGGATGCTCAC-3′ | 5′-CGTTGATATTGCTGATTAAGTCC-3′ | 168 |

| IFN-γ | 5′-TGGGTTCTCTTGGCTGTTAC-3′ | 5′-TGTCTTCCTTGATGGTCTCC-3′ | 252 |

| TNF-α | 5′-GTGAGGAGGACGAACATC-3′ | 5′-GAGCCAGAAGAGGTTGAG-3′ | 95 |

| β-actin | 5′-TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAA-3′ | 5′-CTAAGTCATAGTCCGCCTAGAAGCA-3′ | 186 |

2.8 Cytokine protein production

Supernatants of HPBL were harvested and assayed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) (ADL Co., USA) to quantify IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF-α according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.9 In vitro cytotoxic activity of HPBL

Cytotoxic activity of HPBL was measured by the MTT method (Mosmann, 1983; Xie, 2007). HepG2 was used as target for HPBL. Briefly, a volume of 50ul of the target (T) cell (HepG2) suspension was added to each of 50ul of the effector (E) cells including unirradiated HPBL, irradiated HPBL by X-ray, or irradiated HPBL by 12C6+ ions at E:T ratios of 10:1 in 96-wells plates. The cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 12h. E and T cells were also incubated separately in the same conditions with a final volume of 100ul. Four hours before the end of the incubation, 20ul of the MTT solution (Sigma, St Louis, Missouri, USA) (5mg/ml in PBS) was added to each well and 10% SDS-0.1 mol/L HCl was added to stop the reaction. The optical density (OD) value of each well was measured using a microculture plate reader with a test wavelength of 570nm. The percentage of NK activity of HPBL was calculated using the following formula:

2.10 Statistical analysis

Each value was presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). An ANOVA analysis of variance was used to test the difference of values between irradiated and unirradiated groups. A p-value of 0.05 was selected as a criterion for a statistically significant test.

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Effect of low dose X-ray and 12C6+ irradiation on T and NK cells subsets

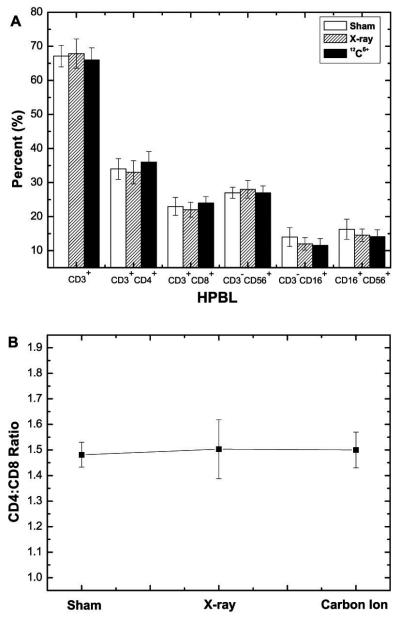

T lymphocytes and NK cells play important roles in host defense from both tumor development and infection by pathogens (Galon et al., 2006; Cristina et al., 2009; Clemente et al., 1996). This study showed that there was no significant change in the percentage of subgroups of T (CD3+-mature T cells, CD3+CD4+-T helper cells/Th cells and CD3+CD8+-T cytotoxic cells/Tc cells) and NK cells (CD3−CD16+, CD3−CD56+, CD16+CD56+) at 24h after exposure to 0.05Gy X-ray and 12C6+ irradiation. In addition, there were no significant differences in CD3+CD4+/ CD3+CD8+ ratio among sham, X-ray and 12C6+ ion groups (Fig 1). These results were similar to a clinical report showed that LDI did not alter the percentage of the various cell populations in peripheral blood of patients with metastatic melanoma at 24h after irradiation with X-ray radiation (Safwat et al., 2003). It is unclear that the unchanged percentage of T and NK cells is due to the unchanged cell count or due to the same amount change in cell count of all cell populations in the same direction. It is possible that NK cells, extrathymic T cells might be radioresistance (Halder et al., 1998; Abo et al., 2000; Gridley et al., 2002). It is also possible that since the analysis was conducted at 24h after irradiation, which might still be in induction period, data at later time points after exposure are needed.

Fig 1. Change in percentage of T and NK cells subsets of HPBL and CD4+:CD8+ T lymphocytes ratio at 24h after irradiation with 0.05Gy X-ray or 12C6+ ions.

(A) Change in T and NK cells subsets of HPBL. (B) CD4+:CD8+ T lymphocytes ratio.

3.2 Cytokine production of HPBL after low dose irradiation

Experimental studies have suggested that the efficacy of low dose total body irradiation (LTBI) using low-LET radiation induces host immune enhancement (Galdiero et al., 1994; Hashimoto et al. 1999; Hashimoto 1997; Liu et al. 1994; Nogami et al., 1993; Shen et al., 1991). For example, animal studies found that LDI with low-LET radiation could alter cytokine release, particular the activation of IFN-γ and IL-2 (Galdiero M et al., 1994; Hashimoto S et al. 1999; Shen et al., 1991). However, there is lack of human data on effects of LDI with high LET irradiation on immune response.

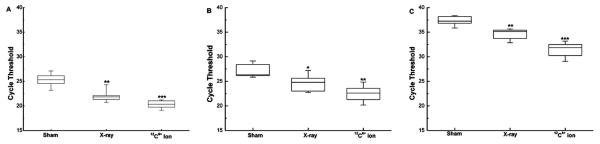

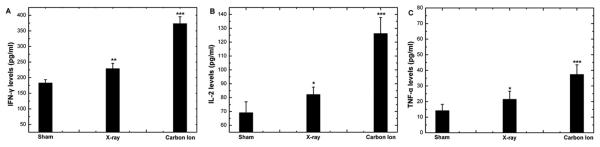

In this study, the mRNA expression levels of IFN-γ, IL-2 and TNF-α in HPBL increased significantly after irradiation. The increase was more pronounced in the group irradiated by 12C6+ ion than in that irradiated by X-ray (Fig 2). The results were further confirmed by ELISA assays assessing in protein levels for IL-2, TNF-α and IFN-γ (Fig 3).

Fig 2. The change in Real-time PCR cycle threshold values in HPBL at 24h after irradiation with 0.05Gy X-ray or 12C6+ ions.

Expression levels of IFN-γ (A), IL-2 (B) and TNF-α (C) are shown as medians (lines), 25th percentile to the 75th percentile (boxes) and ranges (whiskers) for seven samples. (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs. 0Gy; n=7). The significance among radiated groups was determined by ANOVA.

Fig 3. The change in protein levels of IFN-γ (A), IL-2 (B) and TNF-α (C) in supernatant of HPBL at 24h after irradiation with X-ray or 12C6+ ions.

(**p<0.01,***p<0.001 vs. 0Gy; n=7). The significance among radiated groups was determined by ANOVA.

These results suggested that 0.05Gy 12C6+ high LET radiation could enhance immune response with more effectiveness than that of low-LET radiation (X-ray). The mechanisms underlying this phenomenon might be due to ionic deposition of energy densely along their tracks, with the high local concentration of radiation damage from high-LET radiation could causing greater impact compared to low-LET radiation (Koizumi et al. 2003).

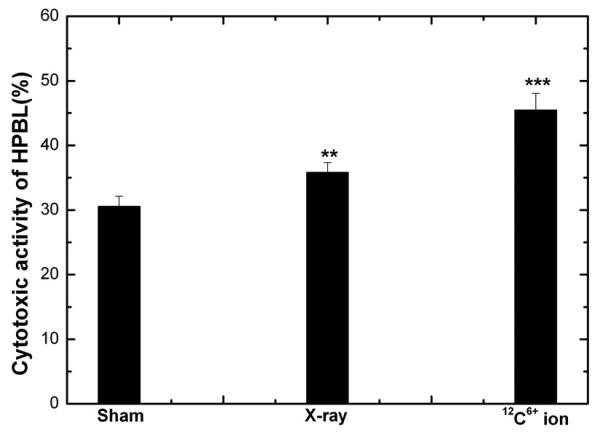

3.3 Effect of low dose X-ray and 12C6+ irradiation on cytotoxic activity of HPBL

Since the cytokine release function of HPBL increased after LDI, we examined the in vitro cytotoxic activity of HPBL. As shown in Fig 4, the cytotoxic activity of HPBL increased significantly after irradiation, especially with 12C6+ radiation, which was in parallel with the increasing pattern of mRNA expression and protein levels of IFN-γ, IL-2 and TNF-α. This suggests that the increasing expression of IFN-γ, IL-2 and TNF-α might be responsible for the enhancement cytotoxic activity of HPBL.

Fig 4. Change in Cytotoxic activity of HPBL at 24h after irradiation with X-ray or 12C6+ ions.

(**p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs. 0Gy; n=5). The significance among radiated groups was determined by ANOVA.

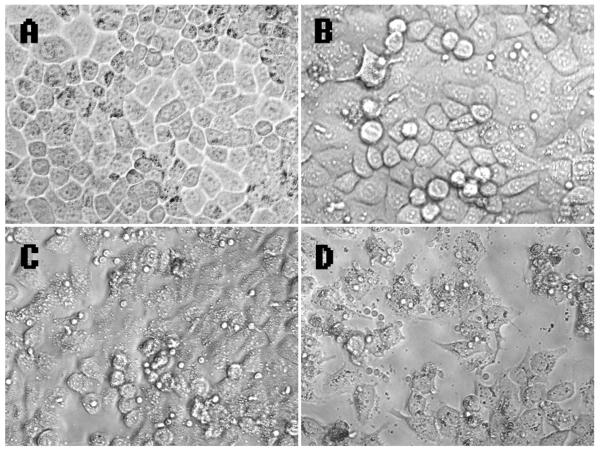

The morphology of HPBL after carbon ion irradiation treatment revealed a decrease in spreading for substrates (Fig 5). The number of HepG2 cells treated by HPBL was less in the 12C6+irradiation group than in that of X-ray group. An explanation for this finding may be that 12C6+ ions result in high LET radiation characterized by a higher RBE compared to low LET radiation (Zhang et al., 2006). In addition, the greater increase in cytokines release induced by 12C6+ ions radiation compared to X-ray might also be responsible for this phenomenon.

Fig 5. Micrographs of HPBL-HepG2 cells.

(A) Micrographs of HepG2 cells. (B) Micrographs of HPBL-HepG2 cells. (C) Micrographs of HPBL exposure to X-ray-HepG2 cells. (D) Micrographs of HPBL exposure to carbon ion-HepG2 cells.

4. Conclusion

Our study provides the first evidence that exposure to 0.05Gy 12C6+ ions radiation increases in cytotoxic activity of HPBL, mRNA expression of IL-2, TNF-α and IFN-γ in HPBL, or cytokine protein levels in human immune cell lines. Although we did not observe a significant change in the T and NK cell subsets of HPBL at 24 hours following irradiation, future studies of the chronic effects of LDI on human immune functions are needed.

Acknowledgement

We express our thanks to the accelerator crew at HIRFL, National Laboratory of Heavy Ion Accelerator in Lanzhou. This project was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (30770639, 30870364). The project was also partially supported by Fogarty training grants 1D43TW008323-01 and 1D43TW007864-01 from the National Institute of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abo T, Kawamura T, Watanabe H. Physiological responses of extrathymic T cells in the liver. Immunol. Rev. 2000;174:135–149. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.017415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellik L, Ledda F, Parenti A. Morphological and phenotypical characterization of human endothelial progenitor cells in an early stage of differentiation. FEBS Letters. 2005;579:2731–2736. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese EJ, Baldwin LA. Radiation hormesis: the demise of a legitimate hypothesis. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2000;19:76–84. doi: 10.1191/096032700678815611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente C, Mihm MC, Bufalino R, Zurrida S, Collini P, Cascinelli N. Prognostic value of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in the vertical growth phase of primary cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 1996;77:1303–1310. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960401)77:7<1303::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristina M, Scaramuzza S, Parmiani G. TNK cells (NKG2D+CD8+or CD4+T lymphocytes) in the control of human tumors. Cancer Immunology Immunotherapy. 2009;5:801–808. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0635-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87:2095–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdiero M, Cipollaro del' Ero G, Folgore A, et al. Effects of irradiation doses on alterations in cytokine release by monocytes and lymphocytes. J. Med. 1994;25:23–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach R, Roos H, Kellerer AM. Heavy ion RBE and microdosimetric spectra. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2002;99:413–418. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley DS, Pecaut MJ, Dutta-Roy R, Nelson GA. Dose and dose rate effects of whole-body proton irradiation on leukocyte populations and lymphoid organs: Part I. Immunol. Lett. 2002;80:55–66. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(01)00306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder RC, Seki S, Weerasinghe A, Kawamura T, Watanabe H, Abo T. Characterization of NK cells and extrathymic T cells generated in the liver of irradiated mice with a liver shield. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1998;144:434–447. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SB, Moratz C, Huang NN, Kelsall B, Cho H, Shi CS, et al. Rgs1 and Gnai2 regulate the entrance of B lymphocytes into lymph nodes and B cell motility within lymph node follicles. Immunity. 2005;22:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto S. Effects of low-dose total body irradiation on tumour bearing rats. Nippon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi. 1997;57:418–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto S, Shirato H, Hosokawa M, et al. The suppression of metastases and the change in host immune response after low-dose total body irradiation in tumor bearing rats. Radiat. Res. 1999;151:717–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller RH, Calvanico NJ, Stevens HO. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis in nonhuman primates: I. Studies on the relationship of immunoregulation and disease activity. J. Immunol. 1982;128:116–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi H, Taguchi M, Kobayashi Y, Ichikawa T. Crosslinking of polymers in heavy ion tracks. Nuclear Instruments and Method in Physics Research section B: Beam interactions with Materials and Atoms. 2003;208:161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Liu SZ, Hann ZB, Liu WH. Changes in lymphocyte reactivity to modulatory factors following low dose ionising radiation. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 1994;7:130–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luster MI, Simeonova PP, Gallucci R, Matheson J. Tumor necrosis factor and toxicology. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1999;29:491–511. doi: 10.1080/10408449991349258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assay. J. Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogami M, Huang JT, James SJ, et al. Mice chronically exposed to low dose ionising radiation possess splenocytes with elevated levels of HSP70 mRNA, HSC70 and H5P72 and with an increased capacity to proliferate. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1993;63:775–783. doi: 10.1080/09553009314552181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri G, Bodycote J, Wolff S. Adaptive response of human lymphocytes to low concentrations of radioactive thymidine. Science. 1984;223:594–597. doi: 10.1126/science.6695170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petro TM. Disparate expression of IL-12 by SJL/J and B10.S macrophages during Theiler's virus infection is associated with activity of TLR7 and mitogen-activatedprotein kinases. Microbes. Infect. 2005;7:224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollycove M, Feinendegen LE. Radiation-induced versus endogenous DNA damage: possible effect of inducible protective responses in mitigating endogenous damage. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2003;22:290–306. doi: 10.1191/0960327103ht365oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattan SI. Aging intervention, prevention, and therapy through hormesis. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2004;59:705–709. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.7.b705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren HW, Shen JW, Tomiyama-Miyaji C, Watanabe M, Kainuma E, Inoue M, Kuwano Y, et al. Augmentation of innate immunity by low-dose irradiation. Cellular Immunology. 2006;244:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safwat A, Schmidt H, Bastholt L, Fode K, Larsen S, Aggerholm N, et al. The potential palliative role and possible immune modulatory effects of low-dose total body irradiation in relapsed or chemo-resistant non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2005;77:143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Sagan LA, Cohen JJ. Biological effects of low-dose radiation: overview and perspective. Health Phys. 1990;59:11–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadley JD, Wolff S. Very low doses of X-rays can cause human lymphocytes to become less susceptible to ionizing radiation. Mutagenesis. 1987;2:95–96. doi: 10.1093/mutage/2.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen RN, Lu L, Feng GS, et al. Cure with low-dose total body irradiation of the haematological disorder induced in mice with Friend virus: possible mechanism involving interferon-gamma and interleukin-2. Lymphokine Cytokine Res. 1991;10:105–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KA. Interleukin-2: inception, impact, and implications. Science. 1988;240:1169–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.3131876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZQ, Saigusa S, Sasaki MS. Adaptive response to chromosome damage in cultured human lymphocytes primed with low doses of X-rays. Mutat. Res. 1991;246:179–186. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(91)90120-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Zhang H, Wang YL, Zhou QM, Qiu R. Alterations of immune functions induced by 12C6+ ion irradiation in mice. Int. F. Radiat. Biol. 2007;83:577–581. doi: 10.1080/09553000701481774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young HA, Hardy KJ. Interferon-γ producer cells, activation stimuli, and molecular genetic regulation. Pharmacol Ther. 1990;45:137–151. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90012-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Xie Y, Zhou QM, et al. Adaptive hormetic response of pre-exposure of mouse brain with low-dose 12C6+ion or 60Co γ-ray on growth hormone (GH) and body weight induced by subsequent high-dose irradiation. Adv. Space Res. 2006;38:1148–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Randers-Pehrson G, Waldren CA, Hei TK. Radiation induced bystander effect and adaptive response in mammalian cells. Adv. Space Res. 2004;34:1368–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.asr.2003.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]