Abstract

The simian lentivirus strain SIVsmmFGb is a viral swarm population inducing neuropathology in over 90% of infected pigtailed macaques and serves as a reliable model for HIV neuropathogenesis. However, little is understood about the genetic diversity of this virus, how said diversity influences the initial seeding of the central nervous system and lymph nodes, or whether the virus forms distinct genetic compartments between tissues during acute infection. In this study, we establish that our SIVsmmFGb stock virus contains four genetically distinct envelope V1 region groups, three distinct integrase groups, and two Nef groups. We demonstrate that initial central nervous system and lymph node seeding reduces envelope V1 and integrase genetic diversity but has a variable effect on Nef diversity. SIVsmmFGb envelope V1 region genes from the basal ganglia, cerebellum, and hippocampus form distinct genetic compartments from each other, the midfrontal cortex, and the lymph nodes. Basal ganglia, cerebellum, hippocampus, and midfrontal cortex-derived nef genes all form distinct genetic compartments from each other, as well as from the lymph nodes. We also find basal ganglia, hippocampus, and midfrontal cortex-derived integrase sequences forming distinct compartments from both of the lymph nodes and that the hippocampus and midfrontal cortex form separate compartments from the cerebellum, while the axillary and mesenteric lymph nodes compartmentalize separately from each other. Compartmentalization of the envelope V1 genes resulted from positive selection, and compartmentalization of the nef and integrase genes from negative selection. These results indicate restrictions on virus genetic diversity during initial tissue seeding in neuropathogenic SIV infection.

Introduction

Millions of people worldwide are infected with HIV-1 or −2, the lentiviruses that cause AIDS.1–3 While much HIV/AIDS research focuses on the immunologic and lymphocytic pathogenesis aspects of the infection, the central nervous system (CNS) represents another site of viral pathogenesis. The most common neurological syndrome induced by HIV infection is AIDS dementia complex (ADC), caused by direct or indirect mechanisms of the virus.1,4–6 Most prevalent in the later stages of infection,7,8 ADC affects one- to two-thirds of AIDS patients1,5,9 and has a 6-month mortality rate of 67%.7,8 In the early stages of ADC, patients present with minor impairments in memory, concentration, fine motor control, and reflexes,8,10 eventually progressing to severe disturbances in memory, personality, social interaction, and motor coordination.1,4,6,8,10 The development of encephalitis is associated with high viral antigen loads in the brain,6 multinucleate giant cells, neuronal dysfunction, and neuronal death.1,11 Lesions are spread throughout the brain, but occur most commonly in the subcortical white matter, basal ganglia, and hippocampus.12 While highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) can reduce the incidence and symptoms of ADC by up to 50%,5–7,13–17 drug levels in the CNS may be too low to prevent virus replication (reviewed in Refs. 17–19) and studies demonstrate an increased incidence of HIV minor cognitive motor disorder despite the advent of HAART.17,20

The most common system for studying HIV infection is the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) model, particularly the sooty mangabey-derived SIVsmm, which induces a disease in infected macaques similar to human AIDS.2,4,21,22 The SIV infection model has proven applicable to lentiviral neuropathogenesis studies (reviewed in Refs. 23 and 24), with infected macaques developing encephalitis and meningitis11,21 at the onset of immunosuppression25 and brain lesions similar to those in HIV patients.5,11,21 Infected cells are most commonly found in the macaque cerebral and cerebellar cortical gray and white matter, as well as the midfrontal cortex.5,26 SIV RNA is detectable in multiple regions of the CNS,25,27 and virus can be recovered from the brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), within a few days of infection.11,28–31 The SIV infection model allows sampling of the CNS tissues during the early stages of infection, as well as control of the genotype, dose, and route of administration of the virus inoculum.

Replicable neuropathogenesis studies with the SIV–macaque model are difficult, however, as most SIV strains induce neuropathology in only 25–40% of infected animals.4,5 Attempts to improve neuropathogenicity include passaging SIV strains through brain tissue culture or coinfecting animals with neuropathogenic and immunosuppressive SIV strains; the former method typically being less successful than the latter.32–34 Our studies are aided by a reliably neuropathogenic SIV strain, SIVsmmFGb, isolated by our laboratory.4 Most pigtailed macaques infected with SIVsmmFGb developed neurological symptoms, including ataxia, lack of coordination, and behavioral changes in the last month before sacrifice.4 SIV-infected giant cells, as well as infected microglia and macrophages, were detected by in situ hybridization (ISH) in the brain tissues of all infected pigtail macaques.5

Subsequent analyses revealed that SIVsmmFGb is a largely CCR5-tropic quasispecies,6 reflecting the natural state of HIV-1 in vivo.35,36 This similarity allowed us to use SIVsmmFGb as a model for the initial seeding of nonhuman primate brain by a genetically diverse, neuropathogenic lentivirus. Using a variety of sequence analyses and statistical methods, we explored and categorized the genetic diversity of the envelope (env, Env) V1 region, nef (nef, Nef), and integrase (int, Int) genes of our SIVsmmFGb stock virus, and analyzed the effect of seeding of the pigtailed macaque CNS and lymph node tissues on this diversity. In addition, we analyzed whether the SIVsmmFGb env V1 region, nef, and int genes formed distinct genetic compartments in the CNS tissues of infected pigtailed macaques in acute infection.

Materials and Methods

SIVsmmFGb stock virus isolation and PCR amplification

SIVsmmFGb stock virus was produced as described4 and used for animal inoculations. Viral RNA was isolated with a QIAmp viral RNA minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol, serially diluted 10-, 100-, and 1000-fold and, along with undiluted RNA, was used for RT-PCR with a SuperScript III RNase H reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), with random hexamer primers used for the initial RT step. DNA obtained from these reactions was serial diluted 10-, 100-, and 1000-fold, for 16 total DNA templates (RNA diluted 1:10/DNA diluted 1:10, RNA diluted 1:100/DNA diluted 1:10, etc.). Each template was used for nested PCR of env, nef, and int genes, using the primers described in Supplementary Table 1 (see http://www.liebertonline.com/aid).

Animal inoculation and tissue harvesting

Six juvenile pigtailed macaques, from the Yerkes National Primate Research Center colony (Atlanta, GA), were inoculated intravenously (i.v.) with 100 TCID50 of the SIVsmmFGb stock virus. Animals were inoculated and necropsied individually, using a triaging protocol that was designed to reduce variability and ensure tissue collection from matching anatomic sites in each test subject. Two of the macaques were sacrificed 5 days postinfection (d.p.i.) and the remaining four animals were sacrificed 7 d.p.i. Blood and CSF were harvested before sacrifice, to perform viral load analysis and other studies. All animals were extensively perfused with saline before tissue collection to prevent contamination of CNS samples by the blood. Tissue specimens that were collected from each animal for sequence analysis included the axillary lymph node, mesenteric lymph node, basal ganglia, midfrontal cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum; these were quick-frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C. These tissue samples, and those from other anatomical sites, were also harvested for ISH and determination of viral loads. The tissue samples for ISH were submitted to the O'Neil group and the ISH procedure was performed as described.4

DNA extraction and preparation

Using sterile scalpels, and working on dry ice to avoid tissue damage, small tissue segments were excised and placed in cell lysis buffer containing 0.1 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 25 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and double-distilled H2O (ddH2O), and then homogenized with a 1.0-ml syringe plunger. Homogenates were treated with 50 μg of proteinase K and incubated overnight at 55°C, with periodic vortexing. Samples were brought to room temperature and DNA was harvested via a sequential extraction with Tris-saturated phenol, phenol–chloroform–isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1), chloroform, and 100% ethanol. DNA was pelleted by 15,000-rpm centrifugation for 30 min at 4°C, washed three times with 70% ethanol, air dried, and resuspended in ddH2O. DNA concentration was quantified with a UV spectrophotometer and samples were frozen at −20°C.

PCR amplification and cloning of DNA from experimental tissues

The nef, env, and int genes were amplified from proviral DNA by nested PCR, using an Expand High Fidelity PCR system kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), according to the manufacturer's protocol. After some difficulty in performing PCR amplification of viral genes from the CNS tissues of macaques PQo1 and PQq1, the primers in Supplementary Table 1 were analyzed and found to contain hairpins and dimers. Thus, new primers were designed for env, nef, and int as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description and Sequences of Primers Used for PCR Amplification of env, nef, and int Genes from Tissue Proviral DNA

| Primer number | Primer coordinatesa | Primer description | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 952 | 6360 | env outer forward | GAGGCGTGCTCTAATACAT |

| 953 | 9299 | env outer reverse | ATCATCATCATCTACATCATC |

| 954 | 6474 | env inner forward | CCGAAGAAGGCTAAGGCTAATACA |

| 955 | 9210 | env inner reverse | ATTGTCCCTCACTGTATCCCTG |

| 959 | 8806 | nef outer forward | AGACGGTGGAGACAGAGGTGG |

| 960 | 9950 | nef outer reverse | TCAATCTGCCAGCCTCTCCG |

| 961 | 8947 | nef inner forward | CCAACCAGTGTTCCAGAGGC |

| 962 | 9845 | nef inner reverse | CCCGTAACATCCCCTTTGTGG |

| 963 | 4021 | int outer forward | CCTCCCTTAGTCAGATTAGTC |

| 964 | 5433 | int outer reverse | GGGAAGATTACTCTGCTG |

| 965 | 4106 | int inner forward | GGCAATCAAGAGAAGGAAAGGC |

| 966 | 5378 | int inner reverse | CATAACAAGCCTTCTGTAGGTCC |

Primer coordinates based on PGm5.3 genome.4

Cloning strategy

The PCR products were purified on 0.9% (env) or 1.2% (nef, int) agarose gels and were extracted with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. As restriction sites were not added to the primers, the purified PCR products were ligated with a pGEM-T Vector System I (Promega, Madison, WI), in accordance with the manufacturers' protocol. After incubation for 24 hr at 4°C, the ligations were transformed into Invitrogen ElectroMAX DH10B E. coli (recA1, endA1) cells, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Single bacterial colonies were used for preparation of plasmid DNA containing the inserts. Approximately 2 μg of each p-GEM-T vector/gene insert-positive sample was sent to MWG Biotech for sequencing (MWG Sequencing, Huntsville, AL). Sequencing was performed with pGEM-T vector-specific sequencing primers, each yielding approximately 800 to 900 bp of usable sequence: p-GEM-T forward primer 026, 5′-GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT-3′-2961; p-GEM-T reverse primer 025, 5′-TAACAATTTCACACAGG-3′-2827.

DNA sequence analysis

Sequences were analyzed with EditSeq in the DNASTAR Lasergene v7.1.0 software package (DNASTAR, Madison, WI) and the following sequences were discarded: Poor reads; junk sequence; incomplete nef and int sequences; nef and int sequences with deletions or insertions; and env sequences that did not produce a complete V1 region. The resulting valid sequences were copied into MEGAlign in DNASTAR Lasergene v7.1.0 for translation into Env, Nef, and Int amino acid sequences and all clones with premature stop codons were discarded; at least 20 valid clones were recovered for each gene, from each tissue, from each experimental animal. At least 20 valid clones were also collected for each gene from each of 16 stock virus dilution templates, as described above.

Stock virus sequence grouping

The valid amino acid sequences for Env, Nef, and Int from the SIVsmmFGb stock virus dilutions were pooled in MEGAlign and were aligned by the Clustal W method. A distance-based, neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was produced for all stock virus sequences of each gene, in PAUP* 4.0b10.37 Based on visual inspection of the phylogenetic clade structure of the resulting tree, the stock virus sequences for each gene were divided into subgroups. Sequences in each subgroup were aligned in MEGAlign, via the Clustal W method, and a consensus sequence was generated for each subgroup of each gene. The subgroup consensuses were then aligned in MEGAlign, via the Clustal W method, and a new distance-based, neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was produced in PAUP* 4.0b10. This tree was subjected to bootstrapping analysis, using heuristic search methods, and 1000 bootstrap replicates were produced. Subgroup consensuses for each gene were then grouped based on bootstrap support: Clades of subgroup consensuses with bootstrap support greater than 50% were counted as a unique group, while those subgroup consensuses that did not fall into a clade with greater than 50% bootstrap support were pooled into a separate group.

Tissue-isolated viral gene sequence alignment and grouping

Valid amino acid sequences for Env, Nef, and Int, from each tissue in each experimental animal, were aligned in MEGAlign, via the Clustal W method, with the stock virus subgroup consensuses for that gene. These alignments were exported to PAUP* 4.0b10 and neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees were generated, using both distance- and parsimony-based analysis, with no obvious differences noted between the two methods (data not shown). Visual inspection of the cladistic, phylogenetic distribution of tissue-isolated sequences, in relation to the stock virus subgroup consensuses, was used to sort tissue-isolated sequences into the groups defined by the stock virus analysis. The percentage of sequences in each group was determined for each tissue in each animal and then averaged to determine the mean prevalence of each sequence group in each tissue across all animals. The mean prevalence of each sequence group in each tissue was then compared with the prevalence of that group in the SIVsmmFGb stock virus, using the Mann–Whitney rank-sum test in SigmaStat Demo 2.03 software (Systat, San Jose, CA). The prevalence of each sequence group in all brain tissues and all lymph node tissues were collected into separate pools and then averaged to determine the mean prevalence of each group in the brain and the mean prevalence of each group in the lymph nodes. The mean lymph node prevalence and the mean brain prevalence for each group were compared with each other, and with the group prevalence in the SIVsmmFGb stock virus, using the Mann–Whitney rank-sum test. The Mann–Whitney test was chosen because of the nonnormal distribution of the group prevalences between animals and the unequal variance between the sequence groups from the stock virus and those from tissues. Those Mann–Whitney comparisons with a p value less than, or equal to, 0.05 were considered evidence of statistically significant differences between tissues.

Phylogenetic and phenetic compartmentalization analyses

The phylogenetic compartmentalization of Env V1, Nef and Int amino acid sequences between each of the six tissues was compared using a modified Slatkin–Maddison test, as described elsewhere.38,39 The global mean bootstrap S and global mean random S values for each two-tissue comparison, where S is the least number of evolutionary steps for “tissue of origin,” obtained from this procedure were used to calculate the ratio of bootstrap S to random S values; the standard error of this ratio was then determined using the formulas described elsewhere.40 As described,38,39 if the ratio of global mean bootstrap S to global mean random S is 2 standard errors less than 1, significant compartmentalization between tissues is present.38,41 These procedures were repeated for every possible two-tissue comparison for each of the three viral genes.

The phenetic compartmentalization of env V1, nef, and int between each of the six tissues was compared using Mantel's test, as described elsewhere.38,39,41 Using XLSTAT-Pro (Addinsoft, Paris, France), the Pearson's correlation coefficient, r, was calculated and an estimated p value was generated from 1000 permutations. The null hypothesis, of no compartmentalization between tissues, was rejected for all p values less than, or equal to, 0.05.

Synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution analysis

Analysis of selective pressure in each tissue compartment was performed by analysis of synonymous (dS) and nonsynonymous (dN) substitution rates, as well as the dS/dN ratio. All DNA sequences from the SIVsmmFGb stock virus for env, nef, and int were aligned via the Clustal W method in MEGAlign and consensus sequences were produced for each gene. These consensus sequences were then aligned via the Clustal W method in MEGalign with SIVsmmFGb viral gene sequences obtained from the experimental tissues; the resulting alignments were then exported to MEGA4. For each gene in each tissue in each animal, the pairwise distance between each sequence and the stock virus consensus for that gene was used to calculate the dS and dN values, using the Nei–Gojobori p distance method in MEGA4. For each gene, results from all five (or six) experimental animals were pooled to generate a mean dS and mean dN for each tissue and the Mann–Whitney rank-sum test was used to compare mean dS and mean dN values for each gene within, and between, the tissues. Mean dS and mean dN values were used to generate the dS/dN ratio for each gene in each tissue, across all the experimental animals. The Mann–Whitney rank-sum test was also used to compare the dS/dN ratios between tissues for each gene. Those Mann–Whitney comparisons with a p value ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

SIVsmmFGb stock virus grouping

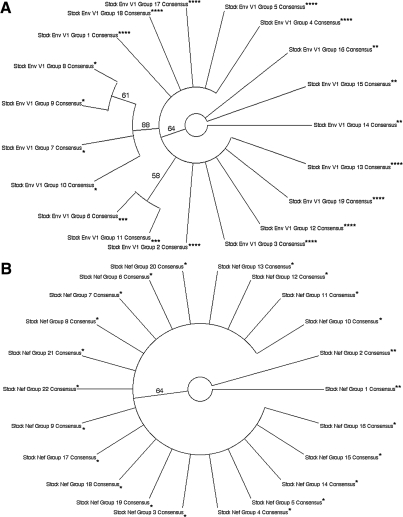

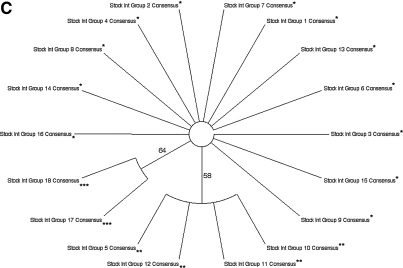

The consensus sequences for Env V1 region amino acid clades were divided into four groups (Fig. 1A): Group 1 consisted of four stock virus Env V1 consensus sequences, representing 50 stock virus sequences (Fig. 2A), with 88% bootstrap support. Group 3 encompassed two stock virus Env V1 consensus sequences, representing 54 stock virus sequences (Fig. 2A), with 58% bootstrap support. Group 4 consisted of 10 stock virus Env V1 consensus sequences, representing 276 stock virus sequences (Fig. 2A), as part of a superclade with 64% bootstrap support. Group 2 consisted of the remaining three consensuses, representing 25 stock virus sequences (Fig. 2A), falling outside any bootstrap-supported clade. For Nef (Fig. 1B), the stock virus consensus sequences were divided into two groups: Group 1 consisted of 20 stock virus Nef consensus sequences, representing 354 stock virus sequences (Fig. 2B), with 64% bootstrap support. The remaining two stock virus Nef consensus sequences, representing 38 stock virus sequences and falling outside the bootstrap-supported clade (Fig. 2B), were collected into group 2. For Int (Fig. 1C), the stock virus consensus sequences were separated into three groups: Group 2 contained four stock virus Int consensus sequences, representing 78 stock virus sequences (Fig. 2C), with 58% bootstrap support. The group 3 clade had 64% bootstrap support and was composed of two stock virus Int consensus sequences (Fig. 2C), representing 31 stock virus sequences. The remaining stock virus Int consensus sequences, falling outside the bootstrap-supported clades and representing 279 stock virus sequences (Fig. 2C), were organized into group 1.

FIG. 1.

SIVsmmFGb stock virus sequence grouping strategy for (A) Env V1, (B) Nef, and (C) Int. Viral RNA isolated from SIVsmmFGb stock virus was serially diluted and used to produce RT-PCR and PCR templates as described in Materials and Methods. Nested PCR for each gene was performed as described and at least 20 clones were analyzed from each reaction. Amino acid sequences of these clones were aligned via Clustal W and distance-based, neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees were produced. Clade consensus sequences from these first neighbor-joining trees were generated and realigned into a new neighbor-joining tree. Clade consensuses and, by extension, their composite sequences were broken into groups based on bootstrap support (1000 replicates) of clades in this second neighbor-joining tree. Bootstrap consensus of the second neighbor-joining tree for each gene is shown; group breakdown, and clades with greater than 50% bootstrap support, are indicated. Groups are indicated as follows: *group 1; **group 2; ***group 3; ****group 4.

FIG. 2.

SIVsmmFGb stock virus sequence group composition. As described in Fig. 1 and Materials and Methods, 16 SIVsmmFGb stock virus templates, with different RNA and DNA dilutions, were used for nested PCR reactions of the env V1 region, nef, and int. At least 20 clones were sequenced and translated for each gene, yielding approximately 400 total SIVsmmFGb amino acid sequences per gene. These sequences were grouped as described in Fig. 1 and the number and percentage of sequences in each group are shown for (A) the Env V1 region, (B) Nef, and (C) Int.

ISH of SIVsmmFGb in brain and peripheral tissues of infected pigtailed macaques

Of the animals sacrificed 5 d.p.i. (Table 2), PQq1 had high numbers of SIV-infected cells in both the inguinal lymph node and spleen, as well as in all gastrointestinal tissues. Comparable numbers of productively infected cells were detected in the inguinal lymph node of animal PQo1, but few infected cells were noted in the spleen and gastrointestinal tissues. Neither animal sacrificed 5 d.p.i. had SIV RNA-positive cells in the bone marrow or brain tissues. PCR amplification of genes from proviral DNA were successful in the lymph node and CNS tissues of animal PQq1 (data not shown) but we were unable to PCR amplify the following genes from animal PQo1: env from the basal ganglia, midfrontal cortex, and cerebellum; nef from the basal ganglia and midfrontal cortex; and int from the basal ganglia and cerebellum. The remaining four animals were sacrificed 7 d.p.i. and all demonstrated high numbers of SIV-positive cells in the inguinal lymph node and spleen, as well as some degree of productive SIV infection in the bone marrow. Three of these animals had high numbers of infected cells in the gastrointestinal tract, while PKo1 showed moderate levels of virus in these tissues. The presence of viral RNA in the CNS varied between animals, with productive infection in four of five and three of three of the brain tissue samples from animals PGt1 and PFp1, respectively. SIV RNA-positive cells could not be detected in the CNS samples from PKo1 and were only present at low levels in medulla from animal PHs1. The low levels of SIV RNA in the CNS of most animals undoubtedly represent genotypes introduced by early, initial seeding. We successfully PCR amplified env, nef, and int genes from all lymph node and CNS tissue samples taken from PFp1, PGt1, PHs1, and PKo1 (data not shown). Because of the relatively low levels of SIVsmmFGb viral RNA present in some of the CNS samples from these animals, we used proviral DNA as a substrate for PCR amplification to maintain consistency through all tissues.

Table 2.

In Situ Hybridization Results on Short-Fixation Tissue Specimens Harvested at Necropsy from Pigtailed Macaques Infected Intravenously with SIVsmmFGb

| |

|

Animal |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

PQq1 |

PQo1 |

PKo1 |

PFp1 |

PGt1 |

PHs1 |

| Sacrificed (d.p.i.): | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |

| Systemic lymphoid tissues | Spleen | 4a | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5a | 5a |

| Inguinal lymph node | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5a | 5a | |

| Bone marrow | 0 | 0b | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | |

| Gastrointestinal tissues | Stomach, fundus | 3 | 1b | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Stomach, pylorus | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | |

| Duodenum | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | |

| Jejunum | 5 | 0b | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Ileum | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Colon | 5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Rectum | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Brain tissues | Prefrontal cortex | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2c | 2 | 0 |

| Midfrontal cortex | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Basal ganglia | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1 | ND | |

| Hippocampus | 0 | 0 | 0 | ND | 2 | 0 | |

| Cerebellar cortex | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Medulla | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1 | |

Abbreviations and symbols: ND, not done; 0, no infected cells; 1, rare infected cells; 2, small numbers of infected cells; 3, moderate numbers of infected cells; 4, large numbers of infected cells; 5, extremely large numbers of infected cells.

Diffuse hybridization present, indicating dendritic cell trapping of virions.

Quality of short fixation specimen evaluated not satisfactory for proper analysis.

SIV+ cells in parenchyma, as well as meninges.

Diversity of Env V1 region, Nef, and Int amino acid sequences isolated from pigtailed macaque brain and lymph node tissues compared with stock virus

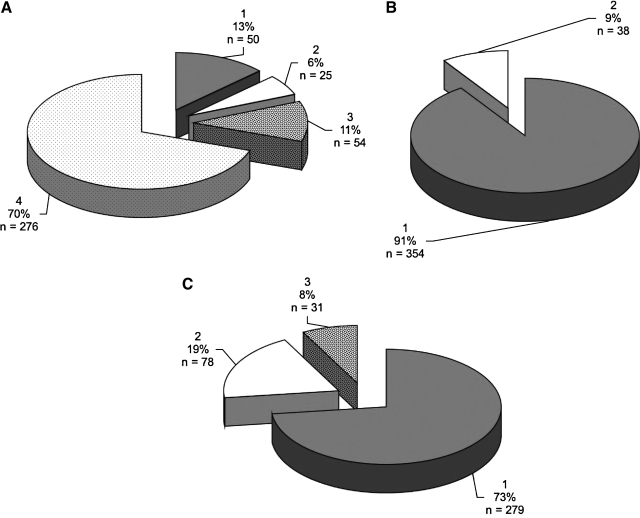

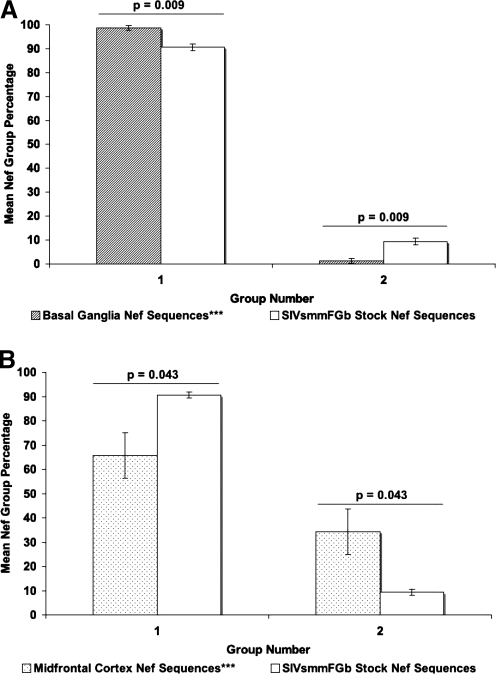

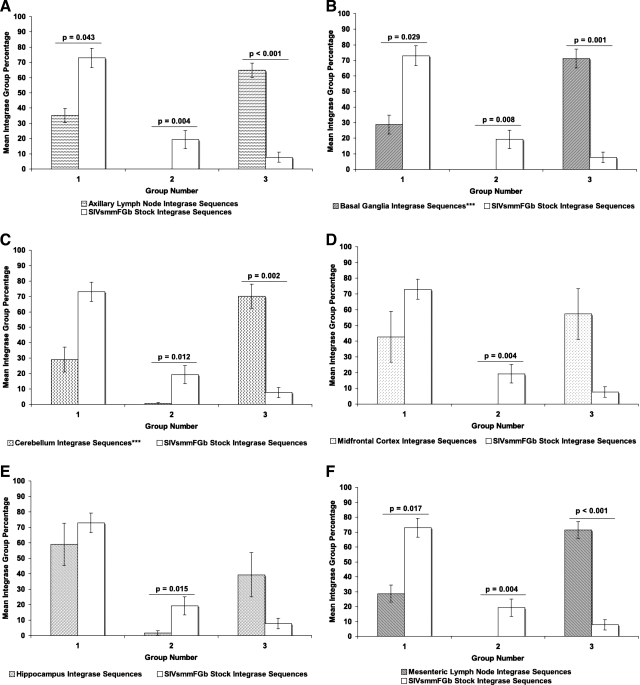

Amino acid sequences for Env V1 region, Nef, and integrase were harvested from the tissues of SIVsmmFGb-infected pigtailed macaques, were screened, and were grouped as described in Materials and Methods. For Env V1 (Fig. 3), the prevalence of group 1 decreased significantly in the axillary lymph node, basal ganglia, hippocampus, and midfrontal cortex. The prevalence of this group did not change significantly in the cerebellum and mesenteric lymph node (Supplementary Fig. 1; see http://www.liebertonline.com/aid). The prevalence of the other three Env V1 groups in any of the tissues was not found to differ significantly from the prevalence of those groups in the SIVsmmFGb stock virus. The prevalence of Nef group 1 increased significantly in the basal ganglia, while group 2 showed a significant decrease (Fig. 4). In contrast, the prevalence of Nef group 1 decreased significantly in the midfrontal cortex, while the prevalence of group 2 increased in this tissue. No significant differences in Nef group prevalence, compared with the stock virus, were noted in the remaining four tissues (Supplementary Fig. 2; see http://www.liebertonline.com/aid). The prevalence of Int group 1 decreased significantly in the basal ganglia and both lymph nodes, relative to the stock virus (Fig. 5). The prevalence of Int group 3, meanwhile, increased significantly in both lymph nodes, the basal ganglia, and the cerebellum. Significant decreases in Int group 2, relative to the stock virus, appeared in all tissues and this group was absent from the basal ganglia, the midfrontal cortex, and both lymph nodes.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of Env V1 region group percentages between tissues harvested from pigtailed macaques 5 or 7 days postinfection and SIVsmmFGb stock virus. Env V1 amino acid sequences obtained from the SIVsmmFGb stock virus were aligned and grouped as shown in Fig. 1. Env V1 amino acid sequences from tissues were grouped as described in Materials and Methods. The percentage of sequences in each group from each tissue was determined for each animal and averaged to yield a mean percentage for each group in each tissue across all animals. The percentage of each group in the SIVsmmFGb stock virus was compared statistically with the mean percentage of each group in the tissues, using the Mann–Whitney rank-sum test. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) are noted. Error bars represent 1 standard error. Results for (A) axillary lymph node, (B) basal ganglia, (C) hippocampus, and (D) midfrontal cortex; cerebellum and mesenteric lymph node results are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Tissues indicated by asterisks (***) lack data from PQo1; results are thus the average of the remaining five animals.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of Nef group percentages between tissues harvested from pigtailed macaques 5 or 7 days postinfection and SIVsmmFGb stock virus. Grouping of stock virus and tissue-derived sequences, as well as statistical comparisons, were performed as described in Figs. 1 and 3 and Materials and Methods. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) are noted. Error bars represent 1 standard error. Results for (A) basal ganglia and (B) midfrontal cortex; axillary lymph node, cerebellum, hippocampus, and mesenteric lymph node results are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Tissues indicated by asterisks (***) lack data from PQo1; results are thus the average of the remaining five animals.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of Int group percentages between tissues harvested from pigtailed macaques 5 or 7 days postinfection and SIVsmmFGb stock virus. Grouping of stock virus and tissue-derived sequences, as well as statistical comparisons, were performed as described in Figs. 1 and 3 and Materials and Methods. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) are noted. Error bars represent 1 standard error. Results are shown for (A) axillary lymph node, (B) basal ganglia, (C) cerebellum, (D) midfrontal cortex, (E) hippocampus, and (F) mesenteric lymph node. Tissues indicated by asterisks (***) lack data from PQo1; results are thus the average of the remaining five animals.

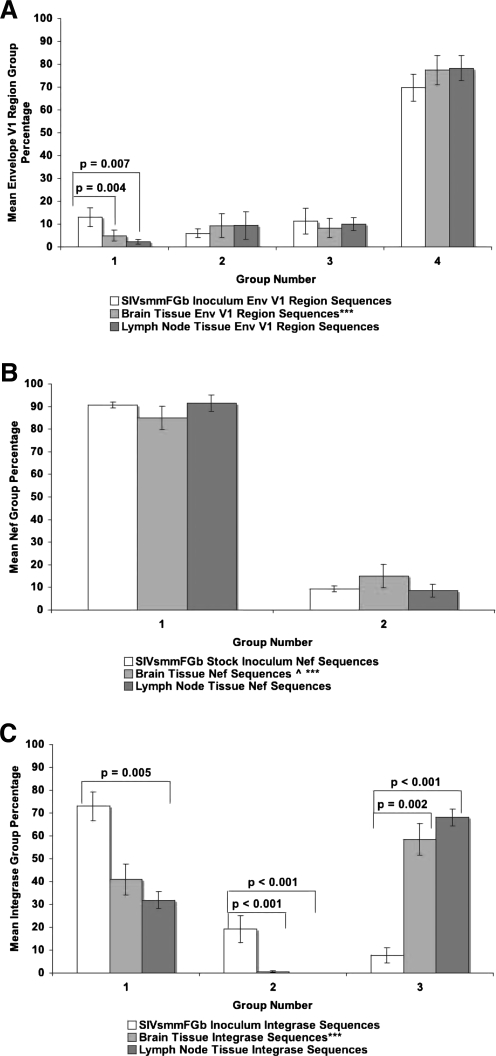

We also compared the mean prevalence of each Env V1, Nef, and Int group across all brain tissues with the mean prevalence of each group in the lymph nodes, as well as the SIVsmmFGb stock virus. The prevalence of Env V1 group 1 in both the CNS and lymph nodes decreased significantly compared with the stock virus, but no significant difference in the prevalence of this group was noted between the CNS and lymph nodes (Fig. 6A). The prevalence of the other Env V1 groups did not differ between the SIVsmmFGb stock virus, the lymph nodes, and the CNS. There was also no significant difference between the stock virus, CNS, and lymph nodes in the prevalence of either group of Nef sequences (Fig. 6B). Int group 1 prevalence decreased significantly in the lymph node compared with the stock virus, but no other significant changes in the prevalence of this Int group were noted (Fig. 6C). The prevalence of Int group 2 decreased significantly in the CNS and the lymph nodes compared with the stock virus, but there was no significant difference between the CNS and the lymph nodes. The prevalence of Int group 3 increased significantly in the CNS and the lymph nodes compared with the SIVsmmFGb stock virus, but there was no difference between the CNS and the lymph nodes.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of sequence group percentages between brain and lymph node harvested from pigtailed macaques 5 or 7 days postinfection and the SIVsmmFGb stock virus. Amino acid sequences for all genes obtained from the SIVsmmFGb stock virus were aligned and grouped as shown in Fig. 1. Amino acid sequences for (A) Env V1 region, (B) Nef, and (C) Int from tissues were grouped as described in Materials and Methods. Statistical analysis, via Mann–Whitney rank-sum test, was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) are noted. Error bars represent 1 standard error. ^Only 19 nef sequences amplified from PQo1 hippocampus; ***data are absent from one or more PQo1 brain tissues; results are average of the remaining five animals.

The prevalence of each Env V1, Nef, and Int sequence group in each tissue was also analyzed in each animal individually. The most prevalent Env V1 region group was group 4, although group 2 predominated in one tissue for three of the six animals and group 3 was the most prevalent in one tissue for two of the six animals (Supplementary Fig. 3; see http://www.liebertonline.com/aid). Group 1 was the most prevalent Nef group in all animals across all tissues, except for in the hippocampus and mesenteric lymph node of PKo1 (Supplementary Fig. 4; see http://www.liebertonline.com/aid). Group 3 was the most prevalent of the Int groups, but all the animals had at least one tissue where the prevalence of group 1 was greater than, or equal to, that of group 3 (Supplementary Fig. 5; see http://www.liebertonline.com/aid).

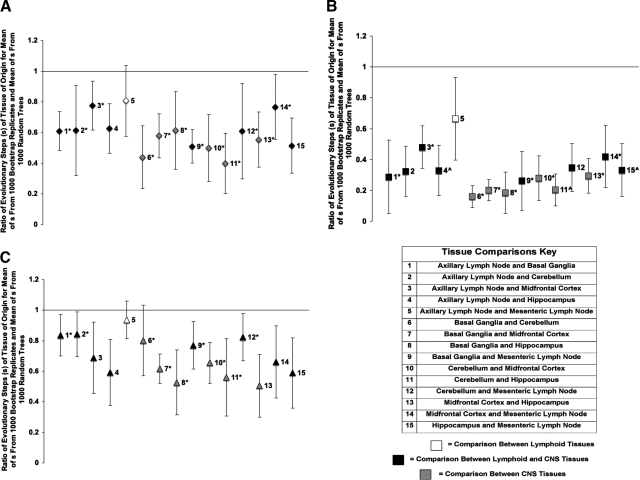

Phylogenetic analysis of compartmentalization of Env V1 region, Nef, and Int amino acid sequences isolated from pigtailed macaque brain and lymph node tissues

To determine whether the SIVsmmFGb Env V1 region, Nef, or Int formed distinct genetic compartments in any CNS or lymph node tissue, a modified Slatkin–Maddison test was used, as described in Materials and Methods. The Env V1 region sequences obtained from all the CNS tissues compartmentalized separately from both of the lymph nodes; the formation of distinct compartments between CNS tissues was also noted (Fig. 7A). However, no significant Env V1 region sequence compartmentalization appeared between the lymph nodes. Similar results were observed for Nef (Fig. 7B), with Nef sequences from each CNS tissue forming distinct compartments from the other CNS tissues and both of the lymph nodes. However, significant compartmentalization of Nef sequences was seen between the axillary and mesenteric lymph nodes. The degree of compartmentalization was greater for Nef than for Env V1 region sequences, with average S ratios of 0.32 (range, ∼0.16 to 0.67) and 0.60 (range, ∼0.40 to 0.81), respectively. The Int sequences obtained from each of the CNS tissues also formed separate compartments from those Int sequences from the other CNS regions and those from the lymph nodes (Fig. 7C). There was no significant Int compartmentalization noted between the basal ganglia and cerebellum or between the axillary and mesenteric lymph nodes. Int sequences had the weakest level of compartmentalization, with an average S ratio of 0.70 (range, ∼0.51 to 0.94).

FIG. 7.

Phylogenetic analysis of SIVsmmFGb compartmentalization between tissues harvested from pigtailed macaques 5 or 7 days postinfection. (A) Env V1 region, (B) Nef, and (C) Int compartmentalization was determined using a modified Slatkin–Maddison test as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars represent 2 standard errors of the determined S ratio; significant compartmentalization between tissues is indicated by ratios more than 2 standard errors less than 1. ^Only 19 nef sequences amplified from PQo1 hippocampus; *data are absent from one or more PQo1 brain tissues; results are the average of the remaining five animals.

Phenetic analysis of compartmentalization of SIVsmmFGb env V1 region, nef, and int sequences isolated from pigtailed macaque CNS and lymph node tissues

To bolster the results of the phylogenetic compartmentalization analysis, and provide a degree of quantification, a Mantel test was used, as described in Materials and Methods, to analyze the phenetic structure of each two-tissue comparison in each of the experimental animals. Because of the size of the data sets, the full results, including the Pearson's correlation coefficients and p values, for the Mantel's test on the env V1 region, nef, and int proviral DNA sequences can be found in Supplementary Tables 2–4, respectively (see http://www.liebertonline.com/aid).

As summarized in Table 3, the env V1 region sequences compartmentalized separately between most of the CNS tissues and both lymph nodes in the majority of the experimental animals. The only exceptions were the env V1 region sequences obtained from the midfrontal cortex, which did not compartmentalize separately from either lymph node in most animals. The env V1 region sequences also did not form separate compartments between the axillary and mesenteric lymph nodes in most animals. The compartmentalization of env V1 region sequences varied between animals, with the basal ganglia–mesenteric lymph node comparison the only one in which all animals demonstrated significant compartmentalization. For both nef and int, most animals showed independent compartmentalization of sequences between all tissues within the CNS. As with env, nef and int sequences did not form separate compartments between lymph nodes in most animals.

Table 3.

Proportion of SIVsmmFGb-Infected Pigtailed Macaques with Compartmentalization Between Compared Tissues, as Determined by Mantel's Testa

| Tissue comparison | env V1 | nef | int |

|---|---|---|---|

| A × B | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| A × C | 3/5 | 6/6 | 3/5 |

| A × F | 2/5 | 4/5 | 6/6 |

| A × H | 4/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 |

| A × M | 2/6 | 2/6 | 2/6 |

| B × C | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| B × F | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| B × H | 3/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| B × M | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| C × F | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| C × H | 3/5 | 6/6 | 5/5 |

| C × M | 3/5 | 5/6 | 4/5 |

| F × H | 3/5 | 5/5 | 6/6 |

| F × M | 2/5 | 5/5 | 5/6 |

| H × M | 5/6 | 5/6 | 4/6 |

Abbreviations: A, axillary lymph node; B, basal ganglia; C, cerebellum; F, midfrontal cortex; H, hippocampus; M, mesenteric lymph node.

Due to absence of data from certain PQo1 tissues, some proportions represent results from only the remaining five animals.

dS and dN values for SIVsmmFGb env V1 region, nef, and int sequences isolated from pigtailed macaque CNS and lymph node tissues

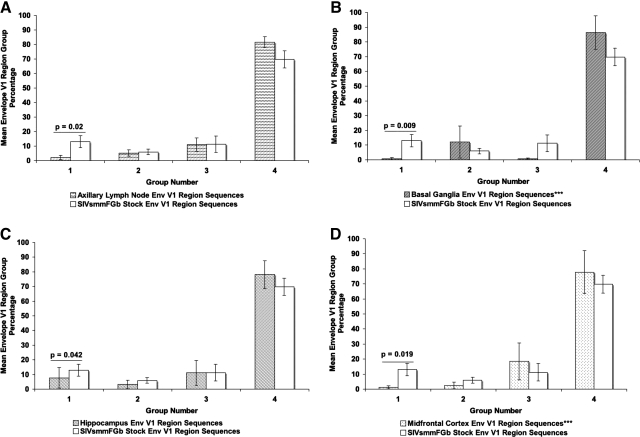

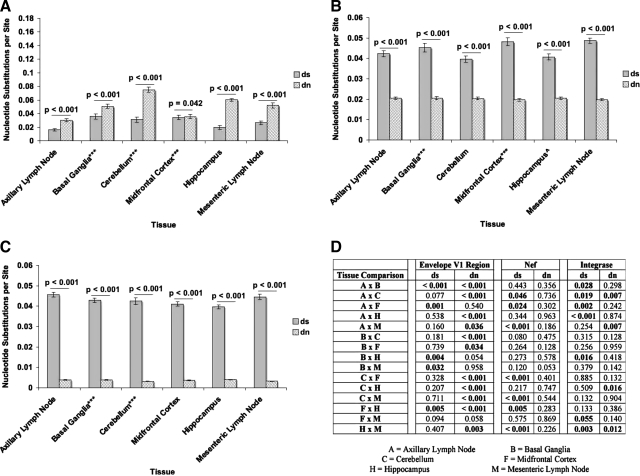

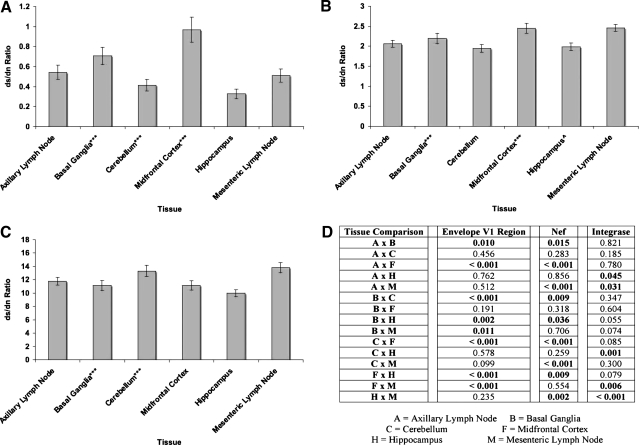

Although the modified Slatkin–Maddison and Mantel's tests suggest compartmentalization of the SIVsmmFGb env V1 region, and nef and int sequences, left undetermined was whether this was due to tissue-specific selection or the replication of limited founder genomes. To test for selective pressure, dS and dN values were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The env V1 region sequences harvested from the experimental animals demonstrated mean dN values significantly higher than the dS values in all six tissues (Fig. 8A). While the dS/dN ratio values for the env V1 region sequences from all six tissues were less than 1 (Fig. 9A), one fell within the standard error range of the mean dS/dN ratio of the env V1 region sequences from the midfrontal cortex (Fig. 9A). The nef and int sequences derived from all six experimental tissues had significantly higher dS values than dN values (Fig. 8B and C), as well as dS/dN ratios greater than 1 (Fig. 9B and C).

FIG. 8.

dS and dN values for (A) env V1 region, (B) nef, and (C) int sequences isolated from tissues of SIVsmmFGb infected pigtailed macaques killed 5 or 7 days postinfection. Average dS and dN for each tissue were determined as described and compared statistically using the Mann–Whitney rank-sum test as described in Materials and Methods. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) are noted. Error bars represent 1 standard error. (D) dS and dN intertissue comparisons, by Mann–Whitney rank-sum test, for all three genes; statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) are noted. ^Only 19 nef sequences amplified from PQo1 hippocampus; ***data are absent from one or more PQo1 brain tissues; results are average of the remaining five animals.

FIG. 9.

Average dS/dN values for (A) env V1 region, (B) nef, and (C) int sequences isolated from tissues of SIVsmmFGb infected pigtailed macaques killed 5 or 7 days postinfection. Mean dS/dN values for each tissue were determined, and statistical comparisons were made, as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars represent 1 standard error. (D) dS/dN ratio intertissue comparisons for env V1 region, nef, and int; statistically significant differences (p < 0.05), by Mann–Whitney rank-sum test, noted. ^Only 19 nef sequences amplified from PQo1 hippocampus; ***data are absent from one or more PQo1 brain tissues; results are average of the remaining five animals.

Comparing the dN, dS, and dS/dN ratio values between tissues can allow for the analysis of differences in selective pressure between tissues. While the mean dS values of the env V1 region sequences obtained from the basal ganglia and midfrontal cortex did not differ from each other (Fig. 8A and D), both had mean dS values significantly higher than the mean dS values of the env V1 region sequences collected from the axillary lymph node and hippocampus. The mean dS value of the env V1 region sequences from the basal ganglia was also found to be significantly higher than those sequences from the mesenteric lymph node. The highest mean dN value was noted in env V1 region sequences from the cerebellum. The mean dN value of midfrontal cortex-derived env V1 region sequences did not differ from the mean dN value of the lymph node-derived sequences, but was significantly lower than the mean dN values of sequences from the other three brain tissues. Cerebellum-derived nef sequences had the lowest mean dS value (Fig. 8B and D), although this was not significantly different from the dS values of nef sequences collected from the basal ganglia and hippocampus. Mesenteric lymph node-derived nef sequences had the highest mean dS value, although this value did not differ significantly from the dS value of nef sequences from the basal ganglia or midfrontal cortex. The highest mean dS value for int was found in sequences obtained from the axillary lymph node (Fig. 8C and D). The next highest mean dS value was for int sequences from the mesenteric lymph node, although this value was only statistically higher than the dS value for nef sequences obtained from the midfrontal cortex and hippocampus. Also, basal ganglia-derived nef sequences were found to have a higher mean dS value than those sequences collected from the hippocampus. The mean dN values of int sequences from the cerebellum and mesenteric lymph node were both significantly lower than the mean dN values of sequences from the axillary lymph node and hippocampus.

The highest mean dS/dN ratio values for env V1 regions were found in sequences derived from the basal ganglia and midfrontal cortex (Fig. 9A and D), while the dS/dN ratios of env V1 region sequences obtained from the other four tissues did not differ from each other significantly. For nef (Fig. 9B and D), sequences from the cerebellum, hippocampus, and axillary lymph node had significantly lower mean dS/dN ratio values than those nef sequences obtained from the basal ganglia, midfrontal cortex, and mesenteric lymph node. The int sequences collected from the hippocampus had a significantly lower mean dS/dN value than those from the cerebellum and lymph nodes, while the midfrontal cortex and axillary lymph node-derived int sequences had lower mean dS/dN values than those sequences obtained from the mesenteric lymph node.

Discussion

Although prior studies have investigated the pathogenesis of SIVsmmFGb, this is the first to comprehensively analyze the genetic characteristics of the virus in the CNS and lymph nodes of pigtailed macaques during initial tissue seeding. Prior research has demonstrated that SIVsmmFGb is a swarm,42 but the genetic makeup of the quasispecies had yet to be determined. We analyzed three SIVsmmFGb genes: int, a highly conserved gene that is resistant to mutations that impact protein function,6,43 and integrates reverse-transcribed viral DNA into the host chromosome44; nef, which has been shown to be involved in HIV and SIV neuropathogenesis13,34,45–47; and env, a rapidly evolving and highly variable gene essential for target cell entry48,49 and with demonstrated functions in neuropathogenesis.50,51

For env, we focused on the V1 variable loop of gp120,52 a major target of neutralizing antibody48,53 and the predominant region of SIV env sequence variation.54 Our results indicate that the Env V1 regions present within our SIVsmmFGb stock virus form four groups, with group 4 being predominant. Meanwhile, the Int sequences in our stock virus separate into three groups and the Nef sequences into two, with group 1 being dominant in both Int and Nef. While we expected Env V1 region sequences to be the most variable, we did not expect a greater diversity of Int sequences over Nef. Using a less stringent method of grouping sequences, such as lowering bootstrap support required for significant clades, or basing groupings on visual inspection of phylogenetic trees, may increase the number of Nef groups, revealing additional diversity of this gene. Another possibility is considering each stock virus consensus sequence for each gene to be a separate group, rather than aligning them to form supergroups. However, the resulting number of groups, over 20 for Nef alone, would have been overly difficult to analyze and represent clearly. Also, because the SIVsmmFGb stock virus was grown in peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) culture, we would not expect any selective pressure to restrict Int diversity or promote Nef diversification.

Given the total number of sequences analyzed, we expect that our results accurately represent the genetic diversity of the SIVsmmFGb stock virus. We obtained at least 20 sequences from each of 16 different dilutions of the RNA and DNA templates used for RT-PCR and PCR, for a balance of statistical significance and feasibility55; few other SIV or HIV studies have analyzed this volume of data. Template dilutions were used to minimize the overamplification of common sequences, the nonamplification of rare sequences and other factors in PCR and RT-PCR, which could introduce bias. While DH10B bacterial subcloning may induce mutations or select against some genomes, the procedure has been used extensively and we would expect this bias to be low. Another potential bias with our protocol is that PCR amplification of proviral DNA presents a “history” of virus infection: Rather than only assessing actively replicating virus, any virus that was capable of reverse transcription and integration will be amplified, regardless of subsequent replicative fitness. Over time, replication-competent viruses with selective advantages should expand more than weak or defective viruses and come to represent the greatest proportion of the proviral DNA population. While defective viruses may be sampled in our procedure, the number of sequences harvested for each tissue should be significant enough to accurately reflect the proviral DNA population, of which defective strains would be a very small part. In addition, we screened all sequences and discarded any clones with in-frame stop codons and frame shift mutations (all three genes) or insertions and deletions (nef and int), which were unlikely to code functional proteins. By not considering these defective sequences in our analysis, we would expect to screen out most integrated, nonreplicating genotypes, reducing this potential bias.

Because of the complexity of the SIVsmmFGb stock virus, some rare genomes may not have been characterized, even with the amount of sequences collected. However, the amount of sequencing required to be certain of having characterized the entire quasispecies would be prohibitively difficult, if not impossible. With the amount of sequences collected for each gene from the stock virus, we expect the possibility of missing a rare, important strain to be low. Using an inoculum composed of a mixture of SIVsmmFGb molecular clones may have eased subsequent analysis, but would introduce bias in choosing which molecular clones to use and what proportion of the inoculum each clone would comprise. In that method, rare constituents of the SIVsmmFGb quasispecies, or sequences that are difficult to clone, could be artificially unrepresented. A less complex inoculum virus could have been used instead, but may not have been as representative of a highly complex quasispecies like HIV-1.41,56

We were interested in determining the effect of the initial seeding of the pigtailed macaque CNS and lymphoid tissues on the genetic profile of our SIVsmmFGb stock virus. We believe the SIVsmmFGb quasispecies is representative of HIV-1 swarms,41,56 and is a strong model of virus seeding that is unique from studies using single, molecularly cloned isolates. An i.v. inoculation was used as this route of infection is known to preserve the diversity of an SIV population better than mucosal infection.57,58 ISH results coincided with our expectations of highly active viral replication in the lymph nodes and gastrointestinal tissues, but limited actively replicating virus in the CNS.42 While the low numbers of SIVsmmFGb RNA-positive cells detected in the CNS may not be strongly convincing of active infection, our previous studies led us to expect productive CNS infection at early time points; even by 5 or 7 d.p.i.4,5,42 In fact, detection of only low levels of SIVsmmFGb RNA in the CNS confirms that we are assessing the very earliest stages of initial CNS colonization, before extensive viral replication and accumulation of mutations, validating our choice of sampling at 5 or 7 d.p.i. As we expect only limited, diffuse replication of SIVsmmFGb in the CNS so early in infection, it is possible the samples used for ISH simply did not contain any productively infected cells or levels of actively replicating virus were below the threshold of detection. The isolation of proviral DNA from brain tissues of most of the experimental animals also confirms SIVsmmFGb replication in the CNS, despite the lack of ISH support. The CNS tissues sampled in this study were chosen from anatomical sites known to be important for neuropathogenic replication in HIV (basal ganglia and hippocampus12,59) and SIV (cerebellum and midfrontal cortex5,26) infections. The mesenteric lymph node was chosen from the gut-associated lymphoid tissues, a major area of SIV replication in early infection,57 while the axillary lymph node was selected to represent nonintestinal lymphoid tissues.

We were unable to amplify some viral genes from three of the CNS tissues harvested from animal PQo1, which was sacrificed 5 d.p.i., when we expected that proviral DNA would be present in the CNS. PQo1 was noted to have unusually low numbers of productively infected cells in the lymph node and gastrointestinal tissues by ISH; similarly reduced levels of active virus replication in the CNS could explain the difficulty harvesting proviral DNA from those tissues. While SIVsmmFGb replicates well in most pigtailed macaques, PQo1 may have been a rare host in which the virus was unable to initiate rapid dissemination. From both the midfrontal cortex and cerebellum of PQo1, we were eventually able to amplify one viral gene but, by the time we were successful, tissue supplies were exhausted and the remaining two genes could not be amplified. Although there was no difficulty in amplifying viral genes from PQq1, which was also sacrificed 5 d.p.i., we chose to sacrificed the remaining four animals at 7 d.p.i., to ensure the virus would have sufficient time to begin colonization of the CNS and reduce the likelihood of difficulty harvesting proviral DNA.

The adaptive immune system is not expected to play a role in host responses to SIVsmmFGb at 5 or 7 d.p.i. The innate immune response, while presenting a challenge to virus replication, would not be expected to specifically target any subset of the quasispecies. Thus, we suspect that any advantage a gene group has at 5 or 7 d.p.i. is due to some intrinsic replicative advantage. Our results suggested that there was selective pressure against Env V1 region group 1 regardless of tissue, but no significant pressure on the other Env V1 region groups. In general, changes in the Env V1 region have been shown to negatively impact SIV replication in macrophages.60 As the Env V1 region is primarily involved in binding CD4,61 it is possible that the Env V1 regions in group 1 possess mutations reducing their capacity to bind CD4. In the CNS, where the target cells for virus infection are primarily macrophage related and express low levels of CD4, a subset of viruses with diminished CD4-binding capacity would be expected to face a disadvantage.62 Unexpectedly, there appeared to be selective pressure against both group 1 and group 2 Int sequences in all tissues, while selection favored Int group 3. It is possible that viruses with Int sequences from groups 1 and 2 may replicate well in the human PBMC tissue culture used to produce the SIVsmmFGb stock virus but not in pigtailed macaques, due to species-specific host factors. Conversely, group 3 Int sequences may have advantageous changes that improve in vivo replication, although this is unlikely given the low mutation rate of int,43 and the general tendency of any mutation to impair protein function. Our results suggested tissue-specific variation in the fitness of the two Nef groups in the CNS, but Nef diversity appears to be largely unaffected by seeding of the pigtailed macaque host. HIV and SIV naturally trigger apoptotic pathways in infected cells63,64 but Nef protects cells, including macrophages, from these deleterious effects.64,65 If a mutation hampering this function was present in one of the Nef groups, this could lead to the death of cells infected with those Nefs and limit the spread of viruses in that group. Similarly, Nef increases virion infectivity,64 and a Nef group with mutations in this function may also see reduction in the spread of the virus.

We expected that SIVsmmFGb env, int, and nef sequences harvested from the CNS would compartmentalize separately from those obtained from the lymph nodes due to differences in available target cells. While the lymph nodes provide ample lymphocytes and macrophages for virus infection, virus infecting the CNS is largely restricted to replication in macrophages and related cells.9,27,37,66–68 In addition, while the peripheral lymphoid tissues may be exposed to infectious virus in the blood and plasma, the blood–brain barrier (BBB) minimizes exposure of the brain to cell-free virus, leaving traffic of infected monocytes or direct BBB infection as the primary routes of CNS seeding.28,69,70 While HIV and SIV env genes have been shown to form separate compartments between the CNS and lymph nodes, and even between CNS tissues,38,40,71,72 no similar research could be found for int and nef. We expected nef and int would face the same pressures as env in terms of target cell availability and restricted seeding of the CNS. However, we presumed that the reduced variability of nef and int would limit the compartmentalization of these two genes. We did not expect to see any of the three genes form separate compartments between the axillary and mesenteric lymph nodes due to similarities in seeding and target cell availability between these two tissues. We used two unique statistical analyses to test for compartmentalization, the modified Slatkin–Maddison test and the more stringent Mantel's test,38,39,41 in order to strengthen our findings.55 The results of both statistical tests supported our hypotheses for env V1 region, except that the Mantel's test indicated that env V1 region sequences from the midfrontal cortex did not compartmentalize independently from those obtained from the lymph nodes in most animals. This discrepancy may be due to the different stringencies of the tests; accounting for standard error, the S ratio values for the midfrontal cortex–lymph node comparisons in the modified Slatkin–Maddison test are very close to 1. There may also be similarities between viruses seeding the midfrontal cortex and those seeding the lymph nodes or the midfrontal cortex and lymph nodes may exert similar selective pressures on the env V1 region. We thus concluded that env V1 region sequences from the basal ganglia, cerebellum, and hippocampus formed separate compartments from each other, the midfrontal cortex, and the lymph nodes. The results of both statistical analyses also largely supported our hypotheses for nef. However, nef sequences from the axillary and mesenteric lymph nodes formed separate compartments from each other and, in the modified Slatkin–Maddison test, nef had a greater degree of compartmentalization overall than the env V1 region. The results of the more stringent Mantel's test suggest that nef sequences from the lymph nodes do not compartmentalize separately from each other and, accounting for standard error, the modified Slatkin–Maddison S ratio value for this comparison is close to 1. However, further data will be required to analyze compartmentalization between these two tissues. We thus conclude that nef sequences compartmentalize separately between CNS tissues and between the CNS tissues and the lymph nodes. The results for int met most of our expectations, except that sequences derived from the basal ganglia and cerebellum did not compartmentalize separately from each other in the modified Slatkin–Maddison test, suggesting seeding of virus between these tissues or similar selective pressures on int within these tissues. However, compartmentalization of int between the basal ganglia and cerebellum was detected by Mantel's test in all animals and the modified Slatkin–Maddison S ratio value for this comparison is close to 1, accounting for standard error.

There are two likely causes of intertissue compartmentalization of virus gene sequences38,41: First, while host tissues may all be seeded by the same or similar components of the quasispecies, selective pressures unique to each tissue may have different effects on swarm evolution in each tissue. The second possibility is that tissue seeding represents a genetic bottleneck for the virus, with a limited subset of the quasispecies forming the founder population that infects a given tissue. The latter possibility appeared most likely, given the restricted seeding and diffuse infection of the CNS by SIVsmmFGb during acute phase,4,5 as well as the lack of an adaptive immune response at 5 or 7 d.p.i. Analysis of dS and dN values for env V1, nef, and int sequences from each tissue was performed to analyze for the presence of selective pressure,73 although such analysis does not completely rule out the possibility of a founder effect. While the SIVsmmFGb swarm is primarily CCR5 tropic,42 which should allow efficient infection of macrophage-related cells in the CNS,9,27,37,66–68 a small subset of the quasispecies uses alternate coreceptors. We expected this non-CCR5-tropic subset would face a selective disadvantage in the CNS and positive selection would mutate these env V1 regions to CCR5 tropism. The results of our dS/dN tests suggest that env V1 region sequences in all six experimental tissues compartmentalized due to positive selection, although results from the midfrontal cortex were less convincing. Similar dS/dN ratio values for env V1 sequences from the basal ganglia and midfrontal cortex suggest similar selective pressures on the env V1 region in these tissues,. These results also argue against a founder effect being responsible for env V1 region selection in at least some of the CNS tissues. With a genetic bottleneck in the CNS, we would expect to see stronger selection in these tissues compared with the lymph nodes, but our results indicate the strength of positive selection in the cerebellum and hippocampus is similar to that in the lymph nodes. However, the level of active virus replication is much higher in the lymph nodes than in the CNS, which may result in increased selective pressure comparable to that of a genetic bottleneck in the CNS tissues. Significant differences in the env V1 region mean dS and/or dN values were noted in most comparisons between tissues, suggesting some functional variance in V1 regions between most tissues.

We expected to find negative selection on nef sequences, as the product of this gene has multiple, conserved functional domains.64,74 Results of the dS/dN analysis supported our hypothesis, as nef sequences appeared to undergo negative selection in all six tissues. On the basis of the significant differences in mean dS/dN ratio values, the hippocampus, cerebellum, and axillary lymph node all exert similar selective pressures on the nef gene. The basal ganglia, midfrontal cortex, and mesenteric lymph node also all exert similar selective pressures on nef sequences, but these pressures are distinct from the other trio of tissues. Given that nef sequences from all the CNS tissues experienced a degree of selective pressure similar to one of the lymph nodes, this suggests a founder effect is not responsible for differences in selection between tissues. As nef is not expected to be under the same evolutionary pressure as the env V1 region, increased levels of virus replication in the lymph nodes are less likely to obscure a possible founder effect in the CNS tissues. While we cannot rule out a founder effect causing negative selection on nef sequences in the CNS, tissue-specific selective pressures appear to be a more likely explanation. Significant differences between the mean dS values of nef sequences in some intertissue comparisons suggest there may be functional differences between viruses harvested from these tissues. The mechanism of these functional differences is currently unknown.

We expected, and our results confirmed, negative selection of int sequences in all tissues, as the functional importance of this gene reduces the likelihood of amino acid changes.6,43 As most genotypes with mutations in int would be expected to be replication defective, they should be rapidly outcompeted by those genotypes with a functional version of this gene. Our results indicated that the effect of negative selection on integrase in most of the CNS tissues is similar to that in the lymph nodes, which suggests that a founder effect plays little role in int selection. As int would be expected to face very little selective pressure compared with the env V1 region and nef, increased levels of virus replication in the lymph nodes should not obscure a founder effect in the CNS tissues. However, we cannot rule out a genetic bottleneck on int in the CNS tissues and, indeed, our results suggest this may be an important factor on int selection in the hippocampus. On the basis of differences in the mean dS/dN values of the int sequences, tissue-specific selective pressures on this gene appear to be strongest in the hippocampus, although differences were also present between the two lymph nodes, and between the midfrontal cortex and one lymph node. Most of the intertissue comparisons of int sequences had differences in the mean dS and/or dN value, suggesting some functional differences between genes from each tissue. However, most of the differences were between int sequences from the CNS and the lymph nodes, rather than from one CNS tissue to another.

Our study focused only on the V1 region of env, due to difficulties we encountered in constructing nested, full-length sequencing primers for this gene. Once the primers are refined, we will fully sequence env and determine whether the results for the V1 region represent those for the complete gene. Alternatively, we will sequence and analyze the other env variable loops. We are currently analyzing the replication of SIVsmmFGb viruses, harvested from the experimental tissues from this study, in primary pigtailed macaque macrophage cultures. These experiments may help reveal functional differences in the env V1 region, nef, and int genes of the SIVsmmFGb viruses after 5–7 d.p.i. Experiments are also underway analyzing env V1 region, nef, and int sequences harvested from SIVsmmFGb-infected pigtailed macaques sacrificed 2 months postinfection, during the clinically latent stage of infection. That study will allow analysis of the results of long-term infection on the genetic diversity of SIVsmmFGb genes in various CNS and lymphoid tissues, as well as changes in compartmentalization and selection after onset of the adaptive immune response.

In summary, our study confirms the quasispecies nature of the highly neuropathogenic primate lentivirus SIVsmmFGb and provides valuable characterization of the env V1 region, nef, and int genes. We have demonstrated that during the initial acute phase, virus seeding of the CNS and lymph nodes in the pigtailed macaque host decreases Env V1 region and Int diversity. We have shown that the SIVsmmFGb env V1 region forms separate genetic compartments in the CNS tissues compared with the lymph nodes, partially due to selective pressure. We have also illustrated that nef and int compartmentalize separately in most experimental tissues due to negative selection. These results with a neuropathogenic SIV swarm in a primate host provide insight into the seeding of CNS tissues during the acute stages of lentivirus infection and may serve as a valuable model of a comparable process in HIV neuropathogenesis.

Sequence Data

The nucleotide sequences referenced in this study are available in the GenBank database under the accession numbers FJ397088–FJ398271 and FJ399865–FJ4022403.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the assistance of the primate care technicians, vet techs, veterinarians, and Research Resources personnel at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center for their assistance in the completion of this project. We also wish to thank Genevieve Niedziela, Ashley St. John, and Chen Chen for their assistance in the early stages of the project. We would also like to thank Anne Piantadosi and Julie Overbaugh for their advice concerning sequencing analysis and appropriate software, as well as Tianwei Yu for advice on statistical analysis. This work was supported by NIH grants MH067769 (to F.J.N.) and RR00165 to the Yerkes National Primate Research Center.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors disclose they have no institutional or commercial affiliations that may pose a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Glenn AA. Novembre FJ. A single amino acid change in gp41 is linked to the macrophage-only replication phenotype of a molecular clone of simian immunodeficiency virus derived from the brain of a macaque with neuropathogenic infection. Virology. 2004;325:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hahn BH. Shaw GM. deCock KM. Sharp PM. AIDS as a zoonosis: Scientific and public health implications. Science. 2000;287:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luo W. Peterlin BM. Activation of the T-cell receptor signalling pathway by Nef from an aggressive strain of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1997;71:9531–9537. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9531-9537.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novembre FJ. De Rosayro J. O'Neil SP. Anderson DC. Klumpp SA. McClure HM. Isolation and characterization of a neuropathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus derived from a sooty mangabey. J Virol. 1998;72:8841–8851. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8841-8851.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Neil SP. Suwyn C. Anderson DC. Niedziela G. Bradley J. Novembre FJ. Herndon JG. McClure HM. Correlation of acute humoral response with brain virus burden and survival time in pigtailed macaques infected with the neurovirulent simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsmmFGb. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1157–1172. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63204-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skinner LM. Lamers SL. Sanders JC. Eyster ME. Goodenow MM. Klatzman M. Analysis of a large collection of natural HIV-1 integrase sequences, including those from long-term nonprogressors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;19:99–110. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199810010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luciano CA. Pardo CA. McArthur JC. Recent developments in the HIV neuropathies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:403–409. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000073943.19076.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price RW. AIDS dementia complex. HIV InSite Knowledge Base Chapter. 1998. http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page = kb-04-01-03. [2009]. http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page = kb-04-01-03

- 9.Sharpless N. Gilbert D. Vandercam B. Zhou JM. Verdin E. Ronnett G. Friedman E. Dubois-Dalcq M. The restricted nature of HIV-1 tropism for cultured neural cells. Virology. 1992;191:813–825. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90257-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghafouri M. Amini S. Khalili K. Sawaya BE. HIV-1 associated dementia: Symptoms and causes. Retrovirology. 2006;3:28–38. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whetter LE. Ojukwu IC. Novembre FJ. Dewhurst S. Pathogenesis of simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1557–1568. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-7-1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiley CA. Soontonniyomkij V. Radhakrishnan L. Masliah E. Mellors J. Hermann SA. Dailey P. Achim CL. Distribution of brain HIV load in AIDS. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:277–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acheampong EA. Parveen Z. Muthoga LW. Kalayeh M. Mukhtar M. Pomerantz RJ. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef potently induces apoptosis in primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells via the activation of caspases. J Virol. 2005;79:4257–4269. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4257-4269.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dore GJ. McDonald A. Li Y. Kaldor JM. Brew BJ. Marked improvement in survival following AIDS dementia complex in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2003;17:1539–1545. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200307040-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enting RH. Prins JM. Jurriaans S. Brinkman K. Portegies P. Lange JMA. Concentrations of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA in cerebrospinal fluid after antiretroviral treatment initiated during primary HIV-1 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1095–1099. doi: 10.1086/319602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gisolf EH. Enting RH. Jurriaans S. de Wolf F. van der Ende ME. Hoetelmans RMW. Portegies P. Danner SA. Cerebrospinal fluid HIV-1 RNA during treatment with ritonavir/saquinavir or ritonavir/saquinavir/stavudine. AIDS. 2000;14:1583–1589. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200007280-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sacktor N. The epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurological disease in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Neurovirol. 2002;8:115–121. doi: 10.1080/13550280290101094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groothius DR. Levy RM. The entry of antiviral and antiretroviral drugs into the central nervous system. J Neurovirol. 1997;3:387–400. doi: 10.3109/13550289709031185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nath A. Sacktor N. Influence of highly active antiretroviral therapy on persistence of HIV in the central nervous system. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006;19:358–361. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000236614.51592.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McArthur JC. Haughey N. Gartner S. Conant K. Pardo C. Nath A. Sacktor N. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia: An evolving disease. J Neurovirol. 2003;9:205–221. doi: 10.1080/13550280390194109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desrosiers RC. The simian immunodeficiency viruses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:557–578. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClure HM. Anderson DC. Fultz PN. Ansari AA. Lockwood E. Brodie A. Spectrum of disease in macaque monkeys chronically infected with SIV/SMM. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1989;21:13–24. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(89)90126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rausch DM. Murray EA. Eiden LE. The SIV-infected rhesus monkey model for HIV-associated dementia and implication for neurological disease. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:466–474. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sopper S. Koutsilieri E. Scheller C. Czub S. Riederer P. ter Meulen V. Macaque animal model for HIV-induced neurological disease. J Neural Transm. 2002;109:747–766. doi: 10.1007/s007020200062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clemens JE. Babas T. Mankowski JL. Suryanarayana K. Piatak M., Jr Tarwater PM. Lifson JD. Zink MC. The central nervous system as a reservoir for simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV): Steady state levels of SIV DNA in brain from acute through asymptomatic infection. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:905–913. doi: 10.1086/343768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lackner AA. Smith MO. Munn RJ. Martfeld DJ. Gardner MB. Marx PA. Dandekar S. Localization of simian immunodeficiency virus in the central nervous system of rhesus macaques. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:609–621. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams KC. Corey S. Westmoreland SV. Pauley D. Knight H. deBakker C. Alvarez X. Lackner AA. Perivascular macrophages are the primary cell type productively infected by simian immunodeficiency virus in the brains of macaques: Implications for the neuropathogenesis of AIDS. J Exp Med. 2001;193:905–915. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.8.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chakrabarti L. Hurtrel M. Maire M. Vazeux R. Dormont D. Montagnier L. Hurtrel B. Early viral replication in the brain of SIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:1273–1280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis LE. Hjelle BL. Miller VE. Palmer DL. Llewellyn AL. Merlin TL. Young SA. Mills RG. Wachsman W. Wiley CA. Early viral brain invasion in iatrogenic human immunodeficiency virus infection. Neurology. 1992;42:1736–1739. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.9.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gouldsmit J. deWolf F. Paul DA. Epstein LG. Lange AJM. Krone WJA. Speelman H. Wolters EC. Van der Noordaa J. Oleske JM. Van der Helm HJ. Coutinho RA. Expression of human immunodeficiency virus antigen (HIV-Ag) in serum and cerebrospinal fluid during acute and chronic infection. Lancet. 1986;2:177–180. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92485-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho DD. Rota TR. Schooley RT. Kaplan JC. Allan JD. Groopman JE. Resnick L. Felsenstein D. Andrews CA. Hirsch MS. Isolation of HTLV-III from cerebrospinal fluid and neural tissues of patients with neurologic syndromes related to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1493–1497. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198512123132401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zink MC. Amedee AM. Mankowski JL. Craig L. Didier P. Carter DL. Munoz A. Murphey-Corb M. Clements JE. Pathogenesis of SIV encephalitis. selection and replication of neurovirulent SIV. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:793–803. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flaherty MT. Hauer DA. Mankowski JL. Zink MC. Clements JE. Molecular and biological characterization of a neurovirulent molecular clone of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1997;71:5790–5798. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5790-5798.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mankowski JL. Flaherty MT. Spelman JP. Hauer DA. Didier PJ. Amedee AM. Murphey-Corb M. Kirstein LM. Munoz A. Clements JE. Zink MC. Pathogenesis of simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis: Viral determinants of neurovirulence. J Virol. 1997;71:6055–6060. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6055-6060.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cichutek K. Merget H. Norley S. Linde R. Kruez W. Gahr M. Kurth R. Development of a quasispecies of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7365–7369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wain-Hobson S. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 quasispecies in vivo and ex vivo. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;176:181–193. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77011-1_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strizki JM. Albright AV. Sheng H. O'Connor M. Perrin L. Gonzalez-Scarano F. Infection of primary human microglia and monocyte-derived macrophages with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates: Evidence of differential tropism. J Virol. 1996;70:7654–7662. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7654-7662.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen MF. Westmoreland S. Ryzhova EV. Martin-Garcia J. Soldan SS. Lackner A. Gonzalez-Scarano F. Simian immunodeficiency virus envelope compartmentalizes in brains regions independent of neuropathology. J Neurovirol. 2006;12:73–89. doi: 10.1080/13550280600654565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poss M. Rodrigo AG. Gosink JJ. Learn GH. Panteleeff DDV. Martin HL., Jr Bwayo J. Kreiss JK. Overbaugh J. Evolution of envelope sequences from the genital tract and peripheral blood of women infected with clade A human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:8240–8251. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8240-8251.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ritola K. Robertson K. Fiscus SA. Hall C. Swanstrom R. Increased human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) env compartmentalization in the presence of HIV-1–associated dementia. J Virol. 2005;79:10830–10834. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10830-10834.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins KR. Quinones-Mateu ME. Wu M. Luzze H. Johnson JL. Hirsch C. Toossi Z. Arts EJ. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 quasispecies at the sites of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection contribute to systemic HIV-1 heterogeneity. J Virol. 2002;76:1697–1706. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1697-1706.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith MS. Niu Y. Buch S. Li Z. Adany I. Pinson DM. Potula R. Novembre FJ. Narayan O. Active simian immunodeficiency virus (strain smmPGm) infection in macaque central nervous system correlates with neurological disease. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:518–530. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000156395.65562.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reinke R. Steffen NR. Robinson WE. Natural selection results in conservation of HIV-1 integrase activity despite sequence variability. AIDS. 2001;15:823–830. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200105040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiu TK. Davies DR. Structure and function of HIV-1 integrase. Curr Top Med Chem. 2004;4:965–977. doi: 10.2174/1568026043388547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gorry PR. Howard JL. Churchill MJ. Anderson JL. Cunningham A. Adrian D. McPhee DA. Purcell DFJ. Diminished production of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in astrocytes results from inefficient translation of gag, env and nef mRNAs despite efficient expression of Tat and Rev. J Virol. 1999;73:352–361. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.352-361.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Overholser ED. Coleman GD. Bennett JL. Casaday RJ. Zink MC. Barber SA. Clements JE. Expression of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) Nef in astrocytes during acute and terminal infection and requirement of Nef for optimal replication of neurovirulent SIV in vitro. J Virol. 2003;77:6855–6866. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6855-6866.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]