Abstract

Forkhead transcription factors play crucial and diverse roles in mesoderm development. In particular, FoxF and FoxC genes are, respectively, involved in the development of visceral/splanchnic mesoderm and non-visceral mesoderm in coelomate animals. Here, we show at single-cell resolution that, in the pseudocoelomate nematode C. elegans, the single FoxF/FoxC transcription factor LET-381 functions in a feed-forward mechanism in the specification and differentiation of the non-muscle mesodermal cells, the coelomocytes (CCs). LET-381/FoxF directly activates the CC specification factor, the Six2 homeodomain protein CEH-34, and functions cooperatively with CEH-34/Six2 to directly activate genes required for CC differentiation. Our results unify a diverse set of studies on the functions of FoxF/FoxC factors and provide a model for how FoxF/FoxC factors function during mesoderm development.

Keywords: FoxF, FoxC, let-381, Forkhead domain, ceh-34, SIX2 homeodomain, eya-1, Eyes absent, Mesoderm, Cell fate specification, M lineage, Coelomocyte, Asymmetry, C. elegans

INTRODUCTION

Proper animal development requires that each cell precisely integrate spatial, temporal and lineal information for its proper specification and differentiation. Dissecting the underlying regulatory networks that govern these processes requires the identification of key transcription factors and their direct target genes. Previous studies in Drosophila and vertebrates have identified a number of transcription factors required for mesoderm development, among them the forkhead domain-containing transcription factors FoxF and FoxC. FoxF1 and FoxF2 are both required for differentiation of the lateral plate mesoderm and proper gut muscle development in mice (Mahlapuu et al., 2001a; Mahlapuu et al., 2001b; Ormestad et al., 2004; Ormestad et al., 2006), whereas the FoxF protein Biniou functions to specify and direct differentiation of visceral mesoderm in Drosophila (Zaffran et al., 2001; Jakobsen et al., 2007; Zinzen et al., 2009), and FoxF in Ciona intestinalis is required for the migration of heart precursors (Beh et al., 2007; Christiaen et al., 2008). In vertebrates, FoxC proteins are expressed in the developing paraxial and intermediate mesoderm, and play important roles in the development of somites, kidneys and the cardiovascular system (Winnier et al., 1999; Kume et al., 2000; Kume et al., 2001; Wilm et al., 2004). Interestingly, Drosophila and vertebrates have at least one homolog each of FoxF and FoxC, whereas the pseudocoelomate nematode C. elegans has a sole FoxF-related factor, LET-381, which is also the closest match for FoxC (Carlsson and Mahlapuu, 2002). In this study, we investigated the role of LET-381/FoxF in the C. elegans postembryonic mesoderm.

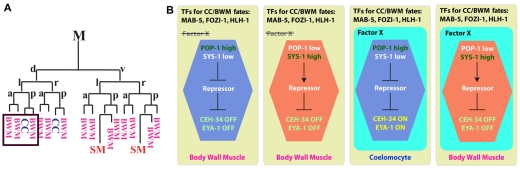

The C. elegans postembryonic non-gonadal mesoderm (the M lineage) is derived from a single pluripotent progenitor cell, the M mesoblast. During postembryonic development, the M mesoblast divides reproducibly and characteristically to produce fourteen striated body wall muscles (BWM), two non-muscle coelomocytes (CCs), and two sex myoblasts (SMs) that are precursors of sixteen non-striated egg-laying muscles (Fig. 1A) (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977). The SMs are descendants of the ventral M lineage, whereas the CCs are dorsally derived. The distinction between the dorsal and ventral M lineage is due to the LIN-12/Notch pathway acting on the ventral lineage, and the Sma/Mab TGFβ pathway being antagonized in the dorsal M lineage by the Schnurri homolog SMA-9 (Greenwald et al., 1983; Foehr et al., 2006; Foehr and Liu, 2008). Within the dorsal M lineage, three M lineage intrinsic factors, HLH-1, FOZI-1 and MAB-5, are required for specifying both the BWMs and the CCs (Harfe et al., 1998a; Harfe et al., 1998b; Liu and Fire, 2000; Amin et al., 2007). The difference between BWMs and CCs is due to the presence of a CC-specifying factor, the Six2 homeodomain protein CEH-34, in the undifferentiated CC cells (Amin et al., 2009). We have previously shown that the proper expression of ceh-34 in the undifferentiated CC cells is due to the combination of differential POP-1 (TCF/LEF) transcriptional activity along the anteroposterior axis and the presence of a CC competence factor(s) (Fig. 1B).

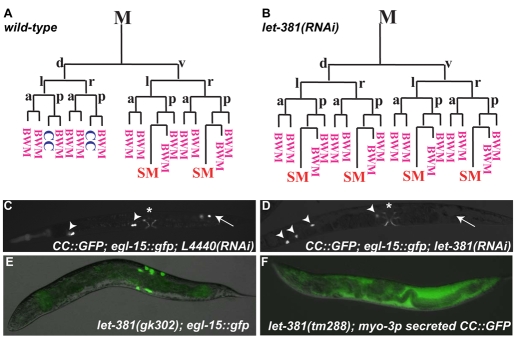

Fig. 1.

CEH-34/Six2 regulates the specification of non-muscle coelomocyte fate in the mesoderm. (A) Schematic of the early M lineage in a wild-type hermaphrodite. M, M mesoblast; d, dorsal; v, ventral; l, left; r, right; a, anterior; p, posterior; CC, coelomocyte; BWM, body wall muscle; SM, sex myoblast. (B) Model for the specification of dorsal M lineage fates (see Amin et al., 2009). CC fates are specified by CEH-34 and EYA-1, which require a number of known upstream factors, and at least one unknown factor, X.

In this study, we show that the sole FoxF/FoxC-related protein in C. elegans, LET-381, is a CC competence factor. LET-381/FoxF directly activates ceh-34 expression, and functions synergistically with CEH-34 to promote M-derived CC fate specification. In addition to its role in specifying the CCs, LET-381/FoxF also directly activates the expression of several genes required for differentiation and function of the CCs. Our studies demonstrate at single-cell resolution that LET-381 functions in a feed-forward mechanism to directly regulate both fate specification and differentiation. These findings unify a diverse set of studies on the functions of FoxF/FoxC factors and provide a model for how FoxF/FoxC factors function during mesoderm development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. elegans strains

Strains were maintained and manipulated using standard conditions (Brenner, 1974). Analyses were performed at 20°C, unless otherwise noted.

The strains LW0683 [rrf-3(pk1426) II; ccIs4438 (intrinsic CC::gfp)III; ayIs2(egl-15::gfp) IV; ayIs6(hlh-8::gfp) X], LW1066 [hlh-8p::mRFP] (Jiang et al., 2008) and LW1734 [jjIs1475(myo-3::rfp) I; rrf-3(pk1426) II; ccIs4438(intrinsic CC::gfp) III; ayIs2(egl-15::gfp) IV; ayIs6(hlh-8::gfp) X] (Amin et al., 2009) were used to visualize M lineage cells in RNAi experiments. Intrinsic CC::gfp is a twist-derived coelomocyte marker, whereas secreted CC::gfp is another coelomocyte marker using a myo-3::secreted GFP that is secreted from the BWMs and taken up by differentiated CCs (Harfe et al., 1998a; Harfe et al., 1998b). Additional M lineage-specific reporters were as described by Kostas and Fire (Kostas and Fire, 2002). Other mutations used were: LG X, sma-9(cc604) (Foehr et al., 2006); LG III, let-381(gk302); let-381(tm288) (gift of Shohei Mitani, Tokyo Women's Medical University, Tokyo, Japan); lin-12(n676n930ts); lin-12(n941) (Greenwald et al., 1983; Sundaram and Greenwald, 1993); LG V, ceh-34 (tm3733) (Amin et al., 2009).

Plasmid constructs and transgenic lines

pNMA90 (3.9 kb ceh-34p::ceh-34 genomic ORF::gfp::unc-54 3′UTR) and pNMA94 (3.9 kb ceh-34p::gfp::ceh-34 ORF::ceh-34 3′UTR) showed identical expression patterns (Amin et al., 2009). pNMA94 was used to generate a series of promoter deletion constructs (Fig. 2A) and constructs carrying mutations in the putative FoxF-binding sites (Fig. 3A).

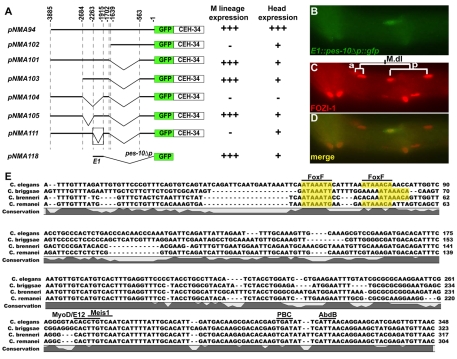

Fig. 2.

The ceh-34 promoter contains a 348-bp enhancer element necessary and sufficient for M lineage expression. (A) Schematic of deletion constructs of the ceh-34 promoter, with the wild-type reference (pNMA94) at the top. Nucleotide positions relative to the ATG of the ceh-34 ORF are indicated above the constructs. The expression of each gfp::ceh-34 transgene is indicated to the right: +++, wild-type expression; +, expression in fewer cells than in wild-type; −, no expression. (B-D) A representative lateral image of a wild-type animal expressing E1::pes-10Δp::gfp (B), labeled with anti-FOZI-1 antibodies (C). (D) Merged image of B and C. (E) Alignment of the C. elegans 348-bp E1 element shown in A with corresponding sequences from C. briggsae, C. remanei and C. brenneri. Putative transcription factor (TF) binding sites are designated by black bars above each of the sites. FoxF sites are highlighted in yellow.

Fig. 3.

LET-381/FoxF directly regulates ceh-34 expression to regulate CC fate specification. (A) Plasmids and oligonucleotides used for mutagenesis of the ceh-34 promoter. Wild-type and mutant sequences from –2210 bp to –2170 bp of the ceh-34 promoter are shown. M lineage expression of the gfp::ceh-34 reporter is indicated to the right of each oligonucleotide sequence. We observed rare cases in which mutating FoxF site 1 resulted in the transient ectopic expression of gfp::ceh-34 in the posterior sister cells of M-derived CCs (asterisks; 3.7%, n=109). (B) ceh-34(tm3733) L1 larvae lack functional CCs, as a myo-3p::secreted CC::GFP reporter is diffused throughout the pseudocoelom. (C,D) Transgenic ceh-34(tm3733) adults expressing pNMA94(C) or pNMA116(D). pNMA94 restores the presence of M-derived CCs and the functionality of the embryonic CCs (C), whereas pNMA116 rescues neither (D). (E-G) let-381(RNAi) results in the loss of gfp::ceh-34 expression in the M lineage (E). (F) M lineage cells labeled by anti-FOZI-1. (G) Corresponding merged image of E and F. (H) EMSA using end-labeled NMA-269/270, purified LET-381 protein, LET-381 antibody and unlabeled NMA-269/270 competitor oligonucleotides. Lanes 5 and 6 have competitors in 200- and 2000–fold excess, respectively. (I) Gel-shift using end-labeled mutant oligonucleotides as indicated above each lane. (J) Gel shift using end-labeled NMA-269/270 and different unlabeled competitior oligonucleotides. An excess of competitors relative to the labeled oligos was used: 500-fold (lanes 3, 8), 1000-fold (lanes 4, 9), 2000-fold (lanes 5, 10), 5000-fold (lanes 6, 11) and 10,000-fold (lanes 7, 12-15). Asterisks (**) in H-J denote binding by degraded LET-381 proteins.

A 348-bp fragment of the ceh-34 promoter (–2260 to –1912) excised from pNMA94 was cloned into L3135 of the Fire Lab Vector Kit (http://www.addgene.org) to generate pNMA118 (E1::pes-10Δp::gfp::lacZ::unc-54 3′UTR). Corresponding E1 fragments with the putative FoxF-binding sites mutated were excised from the plasmids pNMA116, 124 and 127 to generate plasmids pNMA132, 136 and 137, respectively.

Plasmid for let-381(RNAi) was obtained from the Ahringer RNAi library (Kamath et al., 2003) provided by Geneservice and was confirmed by sequencing. Fragments spanning 5 kb of the let-381 promoter or the entire coding region were PCR amplified from N2 genomic DNA using iProof High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Bio-Rad). These PCR fragments were used to generate the let-381 reporter construct pNMA99: let-381p::let-381 genomic ORF::gfp::unc-54 3′UTR. A let-381 cDNA clone, yk679a12, which spans the entire ORF and the 3′UTR of let-381, was used to make the forced expression constructs pNMA85 (hsp-16p::let-381 cDNA::let-381 3′ UTR) and pNMA86 (hlh-8p::gfp::let-381 cDNA::let-381 3′UTR).

Plasmids pJF95 (twist-derived intrinsic CC::gfp) (Harfe et al., 1998b; Kostas and Fire, 2002), pHD43 (unc-122p::gfp) (Loria et al., 2004), pHD53 (cup-4p::gfp) and pHD195(lgc-26p::gfp) (Patton et al., 2005) were used for site-directed mutagenesis to generate plasmids depicted in Fig. 6F-I.

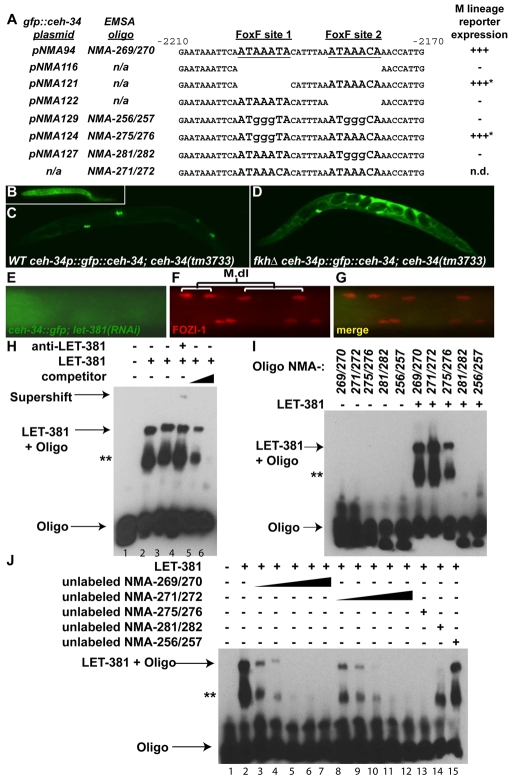

Fig. 6.

LET-381 and CEH-34 might directly regulate CC specification and differentiation. (A-C) Animals with three (A) and six (B,C) M-derived CCs. (C) Magnification of five CCs from the animal in B. (D) Forced expression of ceh-34 and eya-1 using the hlh-8 promoter leads to an increase in the number of M-derived CCs in two independent lines. (E) Heat-shock-induced expression of let-381 in the same transgenic lines containing hlh-8p::ceh-34+hlh-8p::eya-1 leads to higher efficiency and even more M-derived CCs. (F-I) Schematic of CC-specific gene promoters with putative FoxF-, in blue, and Six2-, in red (Noyes et al., 2008) and purple (Hu et al., 2008), binding sites indicated in capital letters. Mutated nucleotides are in lower case letters. Expression in embryonic and M-derived CCs is indicated on the right of each construct: +++, high level of GFP expression; ++, 4-fold reduction in GFP expression; +, 6-fold reduction in GFP expression, –, no GFP expression. (J-M) Representative images of adults listed in G. (J) A wild-type cup-4p::gfp showing six CCs labeled with GFP; (K) FoxF-mutated (mFoxF) cup-4p::gfp (pNMA143) with no GFP expression in the M-derived CCs; (L) Six2-mutated (mSix2) cup-4p::gfp (pNMA146) with six CCs labeled and (M) mFoxF + mSix2 cup-4p::gfp (pNMA150) with no GFP expression in any CC. (N) EMSA using end-labeled wild-type and mutant oligonucleotides as indicated above each lane. Competitor indicates presence of 600-fold excess of unlabeled oligonucleotides, identical to the oligonucleotides used for the gel shift. (O) Gel shift using end-labeled NMA-325/326 and different unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides (U-NMA-). An excess of competitors relative to the labeled oligonucleotides was used: 60-fold (lanes 3, 8), 330-fold (lanes 4, 9, 13), 600-fold (lanes 5, 10, 14), 1000-fold (lanes 6, 11, 15) and 1500-fold (lanes 7, 12).

All plasmids were verified by sequencing. Transgenic lines were generated using the plasmids pRF4 (Mello et al., 1991) or mec-7::rfp (Amin et al., 2009) as markers.

Heat-shock experiments

LW2500 and LW2502 [jjIs2500 and jjIs2502 (hlh-8p::ceh-34+hlh-8p::eya-1+hsp16p::let-381+pRF4); jjIs1475(myo-3::rfp) I; ccIs4438(intrinsic CC::gfp) III; ayIs2(egl-15::gfp) IV; ayIs6(hlh-8::gfp) X] L1 larvae at the 1-M and 2-M stages were heat-shocked in three consecutive cycles at 37°C for one hour followed by recovery at 20°C for three hours until the majority of animals reached the 18-M stage. Non-heat-shocked animals were used as controls. Animals were scored during subsequent larval development for the number and type of M lineage-derived cells.

Antibody production and immunofluorescence staining

Plasmid pNMA70 was used to generate GST-LET-381 (amino acids 179-320) fusion proteins in BL21(DE3) cells. GST-LET-381 fusion proteins were bound to glutathione sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Biosciences) and cleaved from GST by GST-3CPro precision protease (Amersham Biosciences). Soluble LET-381 was extracted and further purified by SDS-PAGE. Gel slices containing purified LET-381 protein were used to immunize rats (Cocalico Biologicals, PA, USA). Resulting antisera CUMC-R27 and CUMC-R28 were used for affinity purification against GST-LET-381 bound to a nitrocellulose membrane (Olmsted, 1981; Smith and Fisher, 1984).

Animal fixation, immunostaining, microscopy and image analysis were performed as described previously (Amin et al., 2007). Guinea pig anti-FOZI-1 (Amin et al., 2007) (1:200), goat anti-GFP (Rockland Immunochemicals; 1:5000), rat anti-LET-381 (1:50) and rabbit anti-HLH-1 (Harfe et al., 1998a) (1:200) antibodies were used.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

A let-381 cDNA fragment containing amino acids 1 to 320 was cloned into the pQE expression system (Qiagen) to generate pNMA76. pNMA76 was transformed into M15[pREP4] cells for subsequent purification of 6×His::LET-381 fusion proteins under denaturing conditions (Qiagen). Proteins were then re-natured in 1 M Tris pH 8.0 at 4°C. Both the full length and a truncated form of the fusion protein were detected after SDS-PAGE by Coomassie staining and western blot analysis. NMA81 contains the full-length ceh-34 cDNA (Amin et al., 2009) in the pGEX expression system (Amersham). GST-CEH-34 fusion proteins were purified and cleaved using the same method as GST-LET-381 (see above). Soluble CEH-34 protein was used for gel shift reactions. Probe DNA oligos were 3′-end labeled with biotin (Biotin 3′ End DNA Labeling Kit, Pierce). Gel-shift reactions and detection were performed using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Pierce).

RESULTS

A 348-bp enhancer element is necessary and sufficient for ceh-34 expression in M lineage-derived CCs

The Six2 homolog ceh-34 is transiently expressed in the undifferentiated M lineage-derived CCs and is required for their proper specification (Amin et al., 2009) (Fig. 1B). Using two ceh-34 reporter constructs, pNMA90 and pNMA94 (see Materials and methods), we have previously shown that the 3.9-kb ceh-34 promoter contains all of the cis-elements required for ceh-34 expression in the M lineage (Amin et al., 2009). To identify the minimal sequences within this 3.9-kb fragment, we generated a series of promoter deletion constructs using pNMA94 (Fig. 2A) and tested the expression of reporter genes in the M lineage. As shown in Fig. 2A, deleting a 348-bp element (–2260 to –1912) located approximately 2 kb upstream of the ceh-34 open reading frame (ORF) abolished the M lineage expression of the reporter, suggesting that the sequences located within this 348-bp element are necessary for M lineage expression of the gfp::ceh-34 cDNA (Fig. 2A). When placed upstream of a basal promoter (referred to as E1::pes-10Δp::gfp), this 348-bp element (E1) is sufficient to drive reporter expression in the M lineage in a pattern identical to that of the functional gfp::ceh-34 translational fusions (Fig. 2A-D). Thus, the E1 element is both necessary and sufficient for ceh-34 expression in the M lineage.

Two putative FoxF-binding sites in the ceh-34 M lineage enhancer are required for the proper expression of ceh-34 in the M lineage

To identify potential trans-acting factors that might regulate ceh-34 expression via the 348-bp E1 enhancer, we compared the sequence of this enhancer with its corresponding sequences in three closely related Caenorhabditis species, C. briggsae, C. brenneri and C. remanei, and searched for putative transcription factor-binding sites using the TESS software (Schug, 2008). There was a high degree of conservation in the second part of the E1 enhancer, which contains putative binding sites for MyoD, Hox, PBC and Meis transcription factors (Fig. 2E). C. elegans homologs for each of these factors, hlh-1 (MyoD), mab-5 (Hox), ceh-20 (PBC) and unc-62 (Meis) have been shown to function in M-derived CC specification (Harfe et al., 1998a; Liu and Fire, 2000; Jiang et al., 2009). Furthermore, hlh-1 and mab-5 are known to function upstream of ceh-34 in the M lineage (Amin et al., 2009).

In addition to these sites, the E1 enhancer also contains two adjacent, conserved putative FoxF (ATAAA(C/T)A) binding sites, which we named as FoxF sites 1 and 2 (Fig. 3A) (Peterson et al., 1997). These sites are intriguing as we have also identified a forkhead transcription factor, let-381, in an RNAi screen for transcription factors important for M lineage development (Amin et al., 2009) (see below). Deleting a 21-nucleotide region containing both sites 1 and 2 in the context of the intact ceh-34 promoter [pNMA116 (fkhΔceh-34p::gfp::ceh-34::ceh-34 3′UTR)] led to the loss of reporter expression in the M-derived CCs without affecting reporter expression in other cell types, such as those in the head (Fig. 3A). Deleting both sites in the E1 enhancer also resulted in the loss of M lineage expression of the E1::pes-10Δp::gfp reporter (data not shown). To directly test the importance of each of the two putative FoxF-binding sites, we made both deletions and clustered mutations in site 1, site 2, or both sites 1 and 2 in the context of the intact ceh-34 promoter and in the E1 enhancer. Mutations in site 2, but not site 1, completely abolished reporter expression in the M lineage (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, at a very low frequency (3.7%, n=109), mutations in site 1 led to transient ectopic expression of the reporter in the posterior sister cells of M-derived CCs [M.d(l/r)pp; data not shown]. These results demonstrated that the two putative FoxF sites, primarily site 2, are crucial for proper ceh-34 expression in the M lineage.

To further determine the functional significance of these two putative FoxF sites, we deleted them in the ceh-34 promoter and assayed the ability of the ceh-34 transgene driven by the mutant promoter to rescue ceh-34 mutant defects. ceh-34(tm3733) mutant animals are 100% lethal at the L1 stage. As seen in ceh-34(RNAi) animals (Amin et al., 2009), these arrested larvae do not have any functional CCs and exhibit a phenotype similar to CC-uptake mutants, in which a GFP secreted from the BWMs (myo-3p::secreted GFP) diffuses throughout the pseudocoelom instead of being taken up by the CCs (Fig. 3B). A translational gfp::ceh-34 fusion driven by the wild-type ceh-34 promoter (pNMA94) rescued both the lethality and the CC uptake defects of ceh-34(tm3733) mutants (Fig. 3C). However, gfp::ceh-34 driven by a mutant ceh-34 promoter with the two FoxF sites deleted (pNMA116) could only rescue the L1 lethality of ceh-34(tm3733) mutants. All of the surviving animals lacked M-derived CCs (n>200), while their embryonic CCs were unable to take up the secreted GFP (Fig. 3D) and showed reduced expression of an intrinsic CC-specific GFP reporter, as compared with wild-type animals (data not shown). Thus, the putative FoxF-binding sites are essential for the proper expression and function of ceh-34 in both M-derived and embryonically derived CCs.

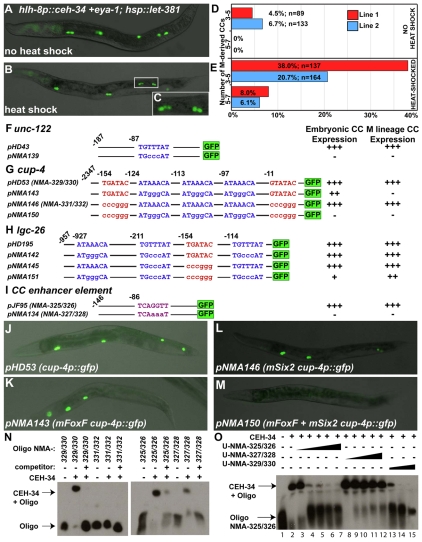

LET-381/FoxF is required for CC fates and ceh-34 expression in the M lineage

C. elegans has a single factor encoded by let-381 that is closely related to FoxF and FoxC in other animals (Carlsson and Mahlapuu, 2002). As let-381 mutations lead to embryonic and larval lethality, we used feeding RNAi to investigate the role of let-381 during postembryonic development. Similar to ceh-34(RNAi), let-381(RNAi) resulted in a loss of M-derived CCs (Fig. 4A-D). By following the M lineage in let-381(RNAi) animals using hlh-8::gfp and anti-FOZI-1 immunostaining (Amin et al., 2007), we found that instead of becoming two CCs, M.dlpa and M.drpa in let-381(RNAi) animals adopted the fate of their ventral counterparts (M.vlpa and M.vrpa), each giving rise to a SM and a BWM (Fig. 4B). The ectopic SMs migrated to the vulva and divided to produce extra sex muscles (as visualized by egl-15::gfp; Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

LET-381 is required for dorsal M lineage CC fates. (A,B) Early M lineage in wild-type (A) and let-381(RNAi) (B) animals. (C,D) L4440-RNAi treated control (C) and let-381(RNAi) (D) adults. CCs are visualized using intrinsic CC::gfp, with embryonic CCs labeled by arrowheads and M-derived CCs by arrows. Type I vulval muscles are visualized using egl-15::gfp, denoted by asterisks. M-derived CCs are missing and extra vulval muscles are present in let-381(RNAi) animals (D). (E,F) Sterile let-381 deletion mutants, gk302 (E) and tm288 (F). let-381 mutants have extra type I vulval muscles (E) and lack functional CCs, as the myo-3p secreted CC::GFP is diffused throughout the pseudocoelom (F).

Two deletion alleles of let-381, gk302 and tm288, also displayed M lineage phenotypes similar to let-381(RNAi) animals. Although the majority of gk302 and tm288 homozygous mutants are embryonic lethal without any functional embryonic CCs, some survive to become sterile adults. These sterile animals lack functional embryonic and M-derived CCs (visualized by a myo-3p::secreted GFP CC marker) and have extra egl-15::gfp-positive sex muscles (Fig. 4E,F). Thus, like ceh-34, let-381 is required for the specification of M-derived CCs.

LET-381/FoxF expression in the M lineage precedes ceh-34 expression

To determine the expression pattern of let-381, we first generated and affinity-purified anti-LET-381 antibodies and immunostained larvae and embryos. We also generated transgenic lines that expressed a functional let-381::gfp fusion (pNMA99) that rescued the lethality and M lineage defects of let-381(tm288) animals (Fig. 5A; data not shown). Both let-381::gfp and anti-LET-381 immunostaining showed similar let-381 expression patterns, which begin during embryogenesis and persist in a small number of cells throughout larval development (Fig. 5B-D). As expected of a transcription factor, LET-381 localizes to the nucleus (Fig. 5B-N). Double-labeling experiments using the let-381::gfp fusion or anti-LET-381 with anti-FOZI-1 staining (to label M lineage cells) (Amin et al., 2007) showed that LET-381 is transiently expressed in the M lineage and is first detected in M.dlp and M.drp as they begin to divide (Fig. 5E-H). Expression continued in both daughters of these divisions [M.d(l/r)pa and M.d(l/r)pp] until the cells differentiated (Fig. 5I-O). Meanwhile, ceh-34 is expressed only transiently in M.d(l/r)pa (Amin et al., 2009). Thus LET-381 precedes the expression of ceh-34 in M-derived CCs prior to differentiation.

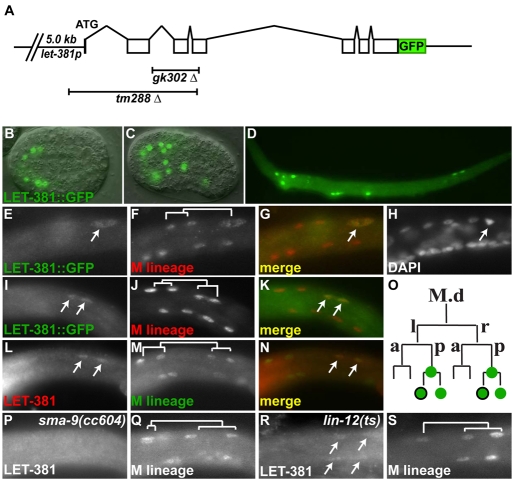

Fig. 5.

The expression of LET-381 in the M lineage precedes that of CEH-34. Images are lateral views with anterior to the left and dorsal up. (A) Schematic of the let-381 translational reporter. Regions deleted in gk302 and tm288 are shown and drawn to scale. (B-D) Representative images of live embryos (B,C) and fixed late L1 larva (D) expressing let-381::gfp. (E-N) The left side of three L1 larvae double-labeled with LET-381::GFP (E,I), anti-FOZI-1 antibody (F,J) and DAPI (H) at the 14-M (E-H) and 16-M stage (I-K). (G,K) Merged images of E and F and of I and J, respectively. (L-N) An L1 larva double-labeled with anti-LET-381 (L) and anti-FOZI-1 antibodies (M) at the 16-M stage. (N) A merged image of L and M. (O) Summary of LET-381 expression in the M lineage, with LET-381-positive cells in green circles and CEH-34-positive cells outlined in black. (P-S) sma-9(cc604) (P,Q) and lin-12(n676n930ts) (R,S) animals double-labeled with anti-LET-381 (P,R) and anti-FOZI-1(P,S) antibodies at the 16-M stage. LET-381 is not expressed in the M lineage of cc604 mutants (P,Q) but is ectopically expressed in ventral M lineage cells of n676n930ts animals (R,S).

The exclusive dorsal localization of LET-381 in the M lineage appears to be under the control of both the LIN-12/Notch and the TGFβ–SMA-9 dorsoventral asymmetry pathways (Greenwald et al., 1983; Foehr et al., 2006; Foehr and Liu, 2008). LET-381 M lineage expression was lost in sma-9(cc604) mutant animals, which have a dorsal-to-ventral fate transformation in the M lineage (Fig. 5P,Q). Meanwhile, ectopic expression of LET-381 in M.v(l/r)pa and M.v(l/r)pp was detected in lin-12(n676n930ts) animals that have a ventral-to-dorsal fate transformation in the M lineage at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 5R,S). let-381(RNAi) in a lin-12(n941) null mutant resulted in an absence of M-derived CCs (data not shown). Thus, like ceh-34, let-381 expression in the M lineage is dependent on the LIN-12/Notch and TGFβ–SMA-9 dorsoventral asymmetry pathways. Similarly, let-381 expression also depends on the mesoderm intrinsic factors FOZI-1, HLH-1 and MAB-5 (data not shown).

LET-381/FoxF directly regulates ceh-34 expression in the M lineage

Because let-381 expression precedes that of ceh-34 in the M lineage and the FoxF sites in the ceh-34 promoter are necessary for ceh-34 expression in the M lineage, we investigated whether LET-381 can directly regulate the expression of ceh-34. First, we performed let-381(RNAi) in ceh-34::gfp animals and found that ceh-34::gfp was lost specifically within the M lineage in let-381(RNAi) animals (Fig. 3E-G). ceh-34(RNAi), conversely, had no effect on let-381 expression in the M lineage (data not shown).

To determine whether the two putative FoxF-binding sites in the ceh-34 M lineage enhancer are sites for LET-381 binding, we tested their ability to bind to purified recombinant LET-381 protein in vitro by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). LET-381 bound to oligonucleotides containing the two wild-type FoxF sites, resulting in a gel mobility shift (Fig. 3H). Addition of anti-LET-381 antibodies to this reaction resulted in a supershift of the LET-381–DNA complex (Fig. 3I), whereas mutating both FoxF sites 1 and 2 abolished the shift (Fig. 3J). The gel mobility shift was also abolished by excess unlabeled wild-type competitor oligonucleotides, but not by mutated binding site competitors (Fig. 3J). Thus, LET-381 might directly regulate ceh-34 expression in the M lineage by directly binding to these FoxF sites. Interestingly, mutation of FoxF site 2 alone completely abolished the gel shift but mutation of FoxF site 1 only slightly reduced the amount of gel shift (Fig. 3I). Furthermore, site 1 mutant oligonucleotides were better competitors than site 2 mutant oligonucleotides in the EMSA assay (Fig. 3J). These data suggest LET-381 has a higher affinity for the second FoxF-binding site, which is consistent with the in vivo data showing that site 2 is crucial for ceh-34 expression in the M lineage (Fig. 3A).

LET-381/FoxF functions together with CEH-34/Six2 in the generation of M lineage-derived CCs

We have previously shown that forced expression of CEH-34 and its cofactor EYA-1 in the M lineage using the hlh-8 promoter leads to the ectopic production of one to two extra M-derived CCs (Amin et al., 2009). We have subsequently shown that these ectopic CCs are derived from the dorsal M lineage and are not the result of increased proliferation (data not shown). A possible explanation for this finding is that other CC-promoting cofactor(s) might exist in the dorsal M lineage to allow ceh-34 and eya-1 to function in specifying M.d(l/r)pa to become CCs (Fig. 1). As LET-381 is transiently localized in M.d(l/r)pp and M.d(l/r)pa, we tested whether LET-381 might be one of these cofactors. We forced the expression of let-381 using the hlh-8 promoter (throughout the M lineage) and the heat-shock-inducible hsp-16 promoter. Forced expression of let-381 alone, using either approach, did not affect M lineage development, nor did it affect the expression pattern of ceh-34 within the M lineage (data not shown), suggesting that other factors are required with LET-381 to activate ceh-34 expression in the M lineage. Interestingly, forced expression of let-381, in conjunction with ceh-34 and eya-1 during M lineage development, led to: (1) the production of up to seven M-derived CCs (Fig. 6A-E); and (2) an overall increase in the efficiency of ectopic CC production compared with forced expression of ceh-34 and eya-1 alone (Fig. 6D,E). By following M lineage development in these animals, we found that most, if not all, BWMs derived from M.d can be transformed into CCs upon ectopic expression of let-381, ceh-34 and eya-1 (data not shown). These results suggest that LET-381 functions together with CEH-34 and EYA-1 to induce CC fate.

To further test if let-381 is required for specifying M-derived CC fates in addition to regulating ceh-34 expression, we performed let-381(RNAi) in transgenic animals expressing hlh-8p::ceh-34 and hlh-8p::eya-1. Whereas control RNAi-treated animals produced two to four M-derived CCs (91.0%, n=145), let-381(RNAi) led to a complete loss of all M-derived CCs, including both normal and ectopic CCs generated in the transgenic line (93.5%, n=123). Thus let-381 is not only required for the expression of ceh-34, but is also required for the specification of CCs in the presence of ceh-34.

LET-381/FoxF directly regulates the differentiation of M-derived CCs

Because LET-381 and CEH-34 together are potent in specifying M-derived CCs, we next tested whether these factors have a direct role in proper differentiation of the CCs. Three genes, unc-122, cup-4 and lgc-26, have been shown to be expressed in all six differentiated CCs throughout development (Loria et al., 2004; Patton et al., 2005). Moreover, cup-4 and lgc-26 are required for the proper function of the CCs (Patton et al., 2005). In addition, a CC-specific enhancer element is located close to the hlh-8 promoter (Harfe et al., 1998b). This 146-bp enhancer is not required for the expression of hlh-8, but when placed upstream of a basal promoter, can drive GFP expression exclusively in all six CCs. We searched for putative LET-381/FoxF [ATAAACA (Peterson et al., 1997)] and CEH-34/Six2 [TCAGGTT (Hu et al., 2008) or TGATAC, (Noyes et al., 2008)] binding sites in these promoters and found that unc-122, cup-4 and lgc-26 all possess at least one putative LET-381/FoxF site within 1 kb upstream of the coding sequence and that cup-4, lgc-26 and hlh-8 also contain putative CEH-34/Six2 sites (see below; Fig. 6F-I)

The 108-bp sequence immediately upstream of the unc-122 coding region is sufficient to drive reporter expression exclusively within all six CCs (Loria et al., 2004). We identified one putative FoxF-binding site in this region and tested reporter expression from both the wild-type and mutant forms of this sequence. As shown in Fig. 6F, mutating this putative FoxF site in the unc-122 promoter led to a loss of GFP expression in both embryonic and M-derived CCs.

The 2.3-kb cup-4 promoter has three putative FoxF-binding sites and two putative Six2-binding sites (Fig. 6G). Mutating all three FoxF sites led to a loss of GFP expression in the M-derived CCs and fainter GFP expression in the embryonic CCs (Fig. 6G,J,K). Although mutating both Six2-binding sites did not affect GFP expression in the CCs (Fig. 6G,L), mutating both Six2 sites and all three FoxF sites together led to a complete loss of GFP in both M- and embryonically derived CCs (Fig. 6G,M).

The 957-bp lgc-26 promoter contains three putative FoxF sites and one putative Six2 site (Fig. 6H). Mutating all three FoxF sites or the Six2 site separately did not affect GFP expression in M- or embryonically derived CCs. However, mutating all four sites together led to reduced GFP expression in all six CCs (Fig. 6H).

The 146-bp enhancer element upstream of hlh-8 does not contain any putative FoxF site, but does have a single putative Six2 site. Mutating this putative Six2 site led to the loss of GFP expression in all CCs of wild-type animals (Fig. 6I).

The putative CEH-34/Six2-binding sites in the above CC enhancers are of two distinct types: TCAGGTT (Hu et al., 2008) in the cup-4 and lgc-26 promoters; or TGATAC (Noyes et al., 2008) in the hlh-8 enhancer (Fig. 6G-I). We tested in vitro the ability of CEH-34 to bind to each type of Six2 site. As shown in Fig. 6N, CEH-34 protein resulted in the mobility shift of oligonucleotides centered around both types of Six2-binding site (NMA-329/330 and NMA-325/326). This mobility shift was abolished when the Six2 site in the cup-4 promoter was mutated (NMA-331/332), and was significantly reduced when the Six2 site in the hlh-8 enhancer was mutated (NMA-327/328), suggesting that CEH-34 can bind to both sites. Competition assays further showed that the wild-type oligonucleotide NMA-325/326 was a more potent competitor than the mutant oligonucleotide NMA-327/328 (Fig. 6O). Furthermore, NMA329/330 was a more potent competitor than NMA-325/326 (Fig. 6O), suggesting that CEH-34 has a higher affinity to TCAGGTT than to TGATAC. Thus, CEH-34 can bind to two distinct sets of sequences, albeit at different affinities.

We performed an in silico search for putative FoxF- and Six2-binding sites in the 5′ regions of 14 additional genes that are expressed in and required for the function of differentiated CCs (Nonet et al., 1999; Fares and Greenwald, 2001b; Grant et al., 2001; Hwang and Horvitz, 2002; Xue et al., 2003; Dang et al., 2004; Roudier et al., 2005; Sato et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2006; Gengyo-Ando et al., 2007; Chun et al., 2008; Sato et al., 2008; Amin et al., 2009; Schwartz et al., 2010). Since the FoxF- and Six2-binding sites for cup-4 and lgc-26 are all clustered immediately upstream of the translation initiation codon (Fig. 6), we focused our search on the 1.5-kb sequences upstream of the ATG. Consistent with our hypothesis that CEH-34 and LET-381 directly regulate the expression of CC differentiation factors, nine out of the 14 genes (mtm-9, rab-10, vps-45, rme-1, rme-6, vps-27, unc-11, sqv-1, hmt-1) had FoxF- or Six2-binding sites in their 5′ regions. Conversely, of 13 randomly selected differentiation genes in the gut (McGhee et al., 2009), where ceh-34 and let-381 are not expressed, only three contained a putative FoxF- or Six2-binding site (data not shown). Taken together, our results suggest that LET-381 and CEH-34 differentially, but probably directly, regulate CC-specific factors for proper CC differentiation and function.

DISCUSSION

LET-381/FoxF directly regulates the CC specification gene CEH-34/Six2 and downstream target genes

Our data demonstrate that LET-381/FoxF directly regulates the expression of another highly conserved transcription factor, CEH-34/Six2, during C. elegans postembryonic mesoderm development: (1) let-381 and ceh-34 are both required for CC fates; (2) let-381 expression precedes, and is required for, ceh-34 expression in the M lineage; (3) the two putative FoxF-binding sites in the ceh-34 promoter are essential for ceh-34 expression in the M lineage; and (4) recombinant LET-381 protein binds to these sites in vitro. Interestingly, FoxF site 2 (Fig. 3A) is absolutely required for ceh-34 expression, whereas mutations in FoxF site 1 lead to a low level of ectopic expression of ceh-34 in the M lineage. Site 1 might represent a binding site for another transcription factor that helps to prevent ceh-34 expression in the posterior sisters of M-derived CCs, such as the factor that has been hypothesized to function downstream of the TCF/LEF homolog POP-1 (Amin et al., 2009).

We have previously shown that forced expression of ceh-34 and its cofactor eya-1 in the M lineage results in a modest increase in the number of M-derived CCs (Amin et al., 2009). let-381(RNAi) in these animals leads to a complete loss of both endogenous and ectopic M-derived CCs, suggesting that let-381 is not only required for ceh-34 expression, but also for CC specification in the presence of ceh-34. Interestingly, forced expression of let-381, ceh-34 and eya-1 throughout the M lineage results in the transformation of all presumptive BWMs in the dorsal M lineage to CCs (Fig. 6; data not shown), suggesting that LET-381 functions together with CEH-34 and EYA-1 to induce CC fate. It is intriguing that only dorsal M lineage descendants are affected in animals with forced expression of let-381, ceh-34 and eya-1. Dorsoventral patterning of the M lineage is under the control of two independent signaling pathways; the LIN-12/Notch pathway is required for ventral M lineage fates, whereas inhibition of the Sma/Mab TGFβ pathway by SMA-9 is required for dorsal M lineage fates (Foehr et al., 2006; Foehr and Liu, 2008). The expression of both let-381 and ceh-34 in the M lineage is under the control of both signaling pathways (Amin et al., 2009) (Fig. 5P-S). It is possible that additional targets of these two pathways are required for CC fate specification. These targets could include a pan-dorsal factor that makes dorsal cells competent to respond to the transcriptional activity of LET-381 and CEH-34, and/or a pan-ventral factor that inhibits the function of let-381 and ceh-34. This is not an unreasonable notion as previous studies have found pan-dorsal or pan-ventral BWM localization of the TGFβ-like molecule UNC-129 and the forkhead transcription factor UNC-130, respectively (Colavita et al., 1998; Nash et al., 2000). Consistent with this idea, we found that forced expression of let-381, ceh-34 and eya-1 in a lin-12 loss-of-function mutant led to the ectopic production of M-derived CCs both dorsally and ventrally (data not shown).

The conclusion that LET-381 functions in parallel to CEH-34 in regulating CC specification is supported by our findings that genes specifically expressed and required for CC function require intact FoxF- and Six2-binding sites in their promoters for proper expression. As shown in Fig. 6, mutating the putative FoxF- and Six2-binding sites in the promoters of unc-122, cup-4 and lgc-26, as well as in a CC-specific enhancer found in the hlh-8 promoter, resulted in either a complete loss of, or reduced, reporter gene expression in the CCs. Moreover, putative FoxF- and/or Six2-binding sites are found in the upstream regions of a number of genes expressed in CCs with a reported role in endocytosis. These findings, coupled with the observation that ceh-34(tm3733) and let-381(tm288 or gk302) null mutant animals have no functional CCs, suggest that LET-381/FoxF and CEH-34/Six2 function combinatorially to directly regulate the differentiation of all six CCs in the worm. Interestingly, FoxF- and/or Six2-binding site mutations in each of the promoters tested resulted in distinct alterations of reporter gene expression, affecting either only M-derived CC expression or expression in both embryonic and M-derived CCs (Fig. 6). It is possible that the local sequence contexts where the putative FoxF- and Six2-binding sites reside help to distinguish between gene expression in the embryonically derived and the M-derived CCs. The observed diversity is consistent with previous findings by Brown et al. (Brown et al., 2007) and Zinzen et al. (Zinzen et al., 2009), and argues against a stringent transcription factor binding code in the cis-regulatory modules regulating CC-specific gene expression.

A model for the specification of non-muscle CCs in postembryonic mesoderm

Our findings are consistent with a model in which LET-381 is the key component in a feed-forward gene network that regulates CC specification within the M lineage (Fig. 7). The proper pattern of LET-381 expression is due to the combinatorial actions of: (1) the presence of the M lineage intrinsic transcription factors HLH-1, FOZI-1 and MAB-5; (2) the lack of LIN-12/Notch signaling; and (3) presence of SMA-9, which antagonizes the Sma/Mab pathway. POP-1/SYS-1 asymmetry along the anteroposterior axis affects ceh-34 expression (Amin et al., 2009). However, the let-381 expression pattern was not altered in sys-1(RNAi) and pop-1(RNAi) animals (data not shown). We have previously reported that SYS-1 and POP-1 are asymmetrically localized at both the 8-M and 16-M stages, and that the earliest M lineage defects we observed in sys-1(RNAi), pop-1(RNAi), sys-1(q544), pop-1(q645) and pop-1(q624) animals are all at the 16-M stage (Amin et al., 2009). Because both pop-1 and sys-1 are required for worm viability, we cannot rule out the possibility that POP-1/SYS-1 asymmetry might also be required for the asymmetric distribution of LET-381 in the M lineage.

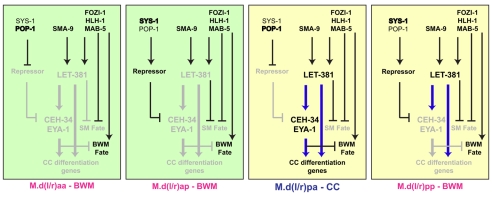

Fig. 7.

LET-381 and CEH-34 function in a feed-forward manner to regulate mesoderm fates. Gene regulatory networks for cell fate specification in the dorsal M lineage are shown for each left/right pair that will adopt either a CC or BWM fate. LET-381 directly regulates the expression of the CC specification factor CEH-34, and both genes function in a feed-forward manner to regulate a number of CC differentiation genes and to suppress the BWM fate. The expression of ceh-34 in M.d(l/r)pa requires both LET-381 and additional factors, either activators in M.d(l/r)pa and M.d(l/r)pp (shaded in yellow) or repressors in M.d(l/r)aa and M.d(l/r)ap (shaded in green). LET-381 also acts to inhibit the specification of SM-specific genes in the dorsal M lineage. let-381 is regulated by dorsoventral signaling mechanisms (SMA-9–Sma/Mab) and mesoderm intrinsic factors (HLH-1, FOZI-1 and MAB-5), which might also regulate ceh-34 expression independently of LET-381. Thick blue lines represent likely direct regulatory relationships, whereas black lines represent relationships based solely on genetic data, and do not distinguish between direct and indirect. Gray lines and text indicate a lack of expression in the indicated cell.

Once properly localized, LET-381 directly activates CEH-34 expression, and functions together with CEH-34 and its cofactor EYA-1 to promote CC fate specification and differentiation by directly regulating the expression of CC-specific factors (Fig. 7). LET-381 also plays a role in suppressing the ventral SM fate, as let-381(RNAi) results in a CC to SM fate transformation (Fig. 4B). However, the inability of LET-381, CEH-34 and EYA-1 to transform ventral M lineage cells to CCs suggests that other pan-dorsal or pan-ventral factor(s) must also be under the control of the dorsoventral asymmetry pathways. Additionally, the inability of forced expression of LET-381 on its own to induce ceh-34 expression or ectopic CC fates suggests that additional factor(s) are required to restrict ceh-34 expression in the M lineage (Fig. 7). These additional factors might also be targets of SMA-9 and/or FOZI-1, as forced expression of let-381, ceh-34 and eya-1 did not rescue the lack of M-derived CC phenotype of sma-9(cc604) and fozi-1(cc609) mutants (data not shown).

Evolutionarily conserved roles of FoxF and FoxC transcription factors during mesoderm development

FoxF transcription factors are important for the development of lateral plate mesoderm, specifically visceral/splanchnic mesoderm, in many organisms, including Drosophila (Biniou), Ciona intestinalis (FoxF), Xenopus (FoxF1) and mouse (FoxF1 and FoxF2). In Drosophila, Biniou is a master regulator of the visceral mesoderm, and functions together with other mesoderm-specific factors to directly regulate multiple genes involved in the specification of the visceral mesoderm and the differentiation of gut muscles (Zaffran et al., 2001; Jakobsen et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2009). Similarly, mice lacking FoxF1 and FoxF2 have improper differentiation of the lateral plate mesoderm and its derivatives, and Xenopus FoxF1 is required for intestinal smooth muscle development (Mahlapuu et al., 2001a; Mahlapuu et al., 2001b; Ormestad et al., 2004; Tseng et al., 2004; Ormestad et al., 2006). In addition, FoxF is required for heart precursor migration by directly activating the effector gene RhoDF in Ciona intestinalis (Beh et al., 2007; Christiaen et al., 2008). Unlike FoxF, FoxC proteins are present in multiple non-visceral mesoderm tissues, including the developing paraxial and intermediate mesoderm, and play important roles in the development of somites, kidneys and the cardiovascular system (Winnier et al., 1999; Kume et al., 2000; Kume et al., 2001; Wilm et al., 2004).

Interestingly, Drosophila and vertebrates have a coelom and have at least one homolog each of FoxF and FoxC. C. elegans is a pseudocoelomate and LET-381 is the only FoxF homolog in C. elegans and also the closest match for FoxC (Carlsson and Mahlapuu, 2002). We have described the roles of LET-381 in the specification and differentiation of CCs in the C. elegans mesoderm. Clearly, CCs are non-muscle cells and they reside in the pseudocoelom of the worm. Although CCs are non-essential to the worm under standard laboratory conditions (Fares and Greenwald, 2001a), they have been recently shown to be important in heavy metal detoxification (Schwartz et al., 2010), a function performed by vertebrate kidneys. Intriguingly, the specification of CC fate requires CEH-34, a Six2 transcription factor whose mammalian homolog is the master regulator of kidney development in the intermediate mesoderm (Self et al., 2006; Kobayashi et al., 2008; Kutejova et al., 2008).

The duplication and evolution of an ancient FoxF/FoxC gene to generate distinct FoxF and FoxC factors appears to correlate with the evolution of the coelom and the further elaboration of distinct mesodermal lineages in coelomate animals, where FoxF regulates lateral plate mesoderm development and FoxC plays a role in the other mesodermal lineages, including the intermediate mesoderm. As Six2 plays a crucial role in the development of the intermediate mesoderm in vertebrates, in light of our findings, it will be interesting to see whether the role of FoxC in kidney development is achieved through the regulation of Six2.

In summary, our results unify a diverse set of studies on the functions of FoxF/FoxC factors and provide a model for how FoxF/FoxC factors function during mesoderm development to regulate cell fate specification and differentiation. They further highlight that the C. elegans postembryonic mesoderm is an excellent system in which to dissect at single-cell resolution the intricate gene regulatory networks underlying mesoderm development.

Acknowledgements

We thank the C. elegans Genetics Center, Hanna Fares, Andy Fire, Yuji Kohara and Shohei Mitani for strains and plasmids; and Ken Kemphues, Mike Krause, Diane Morton and members of the Liu lab for helpful discussions and critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH R01 GM066953 (to J.L.). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Amin N. M., Hu K., Pruyne D., Terzic D., Bretscher A., Liu J. (2007). A Zn-finger/FH2-domain containing protein, FOZI-1, acts redundantly with CeMyoD to specify striated body wall muscle fates in the Caenorhabditis elegans postembryonic mesoderm. Development 134, 19-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin N. M., Lim S. E., Shi H., Chan T. L., Liu J. (2009). A conserved Six-Eya cassette acts downstream of Wnt signaling to direct non-myogenic versus myogenic fates in the C. elegans postembryonic mesoderm. Dev. Biol. 331, 350-360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beh J., Shi W., Levine M., Davidson B., Christiaen L. (2007). FoxF is essential for FGF-induced migration of heart progenitor cells in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Development 134, 3297-3305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. (1974). The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71-94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. D., Johnson D. S., Sidow A. (2007). Functional architecture and evolution of transcriptional elements that drive gene coexpression. Science 317, 1557-1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson P., Mahlapuu M. (2002). Forkhead transcription factors: key players in development and metabolism. Dev. Biol. 250, 1-23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. C., Schweinsberg P. J., Vashist S., Mareiniss D. P., Lambie E. J., Grant B. D. (2006). RAB-10 is required for endocytic recycling in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 1286-1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiaen L., Davidson B., Kawashima T., Powell W., Nolla H., Vranizan K., Levine M. (2008). The transcription/migration interface in heart precursors of Ciona intestinalis. Science 320, 1349-1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun D. K., McEwen J. M., Burbea M., Kaplan J. M. (2008). UNC-108/Rab2 regulates postendocytic trafficking in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2682-2695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colavita A., Krishna S., Zheng H., Padgett R. W., Culotti J. G. (1998). Pioneer axon guidance by UNC-129, a C. elegans TGF-beta. Science 281, 706-709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang H., Li Z., Skolnik E. Y., Fares H. (2004). Disease-related myotubularins function in endocytic traffic in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 189-196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares H., Greenwald I. (2001a). Genetic analysis of endocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans: coelomocyte uptake defective mutants. Genetics 159, 133-145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares H., Greenwald I. (2001b). Regulation of endocytosis by CUP-5, the Caenorhabditis elegans mucolipin-1 homolog. Nat. Genet. 28, 64-68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foehr M. L., Liu J. (2008). Dorsoventral patterning of the C. elegans postembryonic mesoderm requires both LIN-12/Notch and TGFbeta signaling. Dev. Biol. 313, 256-266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foehr M. L., Lindy A. S., Fairbank R. C., Amin N. M., Xu M., Yanowitz J., Fire A. Z., Liu J. (2006). An antagonistic role for the C. elegans Schnurri homolog SMA-9 in modulating TGFbeta signaling during mesodermal patterning. Development 133, 2887-2896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gengyo-Ando K., Kuroyanagi H., Kobayashi T., Murate M., Fujimoto K., Okabe S., Mitani S. (2007). The SM protein VPS-45 is required for RAB-5-dependent endocytic transport in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO Rep. 8, 152-157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B., Zhang Y., Paupard M. C., Lin S. X., Hall D. H., Hirsh D. (2001). Evidence that RME-1, a conserved C. elegans EH-domain protein, functions in endocytic recycling. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 573-579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald I. S., Sternberg P. W., Horvitz H. R. (1983). The lin-12 locus specifies cell fates in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell 34, 435-444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe B. D., Branda C. S., Krause M., Stern M. J., Fire A. (1998a). MyoD and the specification of muscle and non-muscle fates during postembryonic development of the C. elegans mesoderm. Development 125, 2479-2488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe B. D., Vaz Gomes A., Kenyon C., Liu J., Krause M., Fire A. (1998b). Analysis of a Caenorhabditis elegans Twist homolog identifies conserved and divergent aspects of mesodermal patterning. Genes Dev. 12, 2623-2635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S., Mamedova A., Hegde R. S. (2008). DNA-binding and regulation mechanisms of the SIX family of retinal determination proteins. Biochemistry 47, 3586-3594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang H. Y., Horvitz H. R. (2002). The SQV-1 UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase and the SQV-7 nucleotide-sugar transporter may act in the Golgi apparatus to affect Caenorhabditis elegans vulval morphogenesis and embryonic development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14218-14223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen J. S., Braun M., Astorga J., Gustafson E. H., Sandmann T., Karzynski M., Carlsson P., Furlong E. E. (2007). Temporal ChIP-on-chip reveals Biniou as a universal regulator of the visceral muscle transcriptional network. Genes Dev. 21, 2448-2460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Shi H., Amin N. M., Sultan I., Liu J. (2008). Mesodermal expression of the C. elegans HMX homolog mls-2 requires the PBC homolog CEH-20. Mech. Dev. 125, 451-461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Shi H., Liu J. (2009). Two Hox cofactors, the Meis/Hth homolog UNC-62 and the Pbx/Exd homolog CEH-20, function together during C. elegans postembryonic mesodermal development. Dev. Biol. 334, 535-546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath R. S., Fraser A. G., Dong Y., Poulin G., Durbin R., Gotta M., Kanapin A., Le Bot N., Moreno S., Sohrmann M., et al. (2003). Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421, 231-237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A., Valerius M. T., Mugford J. W., Carroll T. J., Self M., Oliver G., McMahon A. P. (2008). Six2 defines and regulates a multipotent self-renewing nephron progenitor population throughout mammalian kidney development. Cell. Stem Cell. 3, 169-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostas S. A., Fire A. (2002). The T-box factor MLS-1 acts as a molecular switch during specification of nonstriated muscle in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 16, 257-269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kume T., Deng K., Hogan B. L. (2000). Murine forkhead/winged helix genes Foxc1 (Mf1) and Foxc2 (Mfh1) are required for the early organogenesis of the kidney and urinary tract. Development 127, 1387-1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kume T., Jiang H., Topczewska J. M., Hogan B. L. (2001). The murine winged helix transcription factors, Foxc1 and Foxc2, are both required for cardiovascular development and somitogenesis. Genes Dev. 15, 2470-2482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutejova E., Engist B., Self M., Oliver G., Kirilenko P., Bobola N. (2008). Six2 functions redundantly immediately downstream of Hoxa2. Development 135, 1463-1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Fire A. (2000). Overlapping roles of two Hox genes and the exd ortholog ceh-20 in diversification of the C. elegans postembryonic mesoderm. Development 127, 5179-5190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. H., Jakobsen J. S., Valentin G., Amarantos I., Gilmour D. T., Furlong E. E. (2009). A systematic analysis of Tinman function reveals Eya and JAK-STAT signaling as essential regulators of muscle development. Dev. Cell. 16, 280-291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loria P. M., Hodgkin J., Hobert O. (2004). A conserved postsynaptic transmembrane protein affecting neuromuscular signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 24, 2191-2201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahlapuu M., Enerback S., Carlsson P. (2001a). Haploinsufficiency of the forkhead gene Foxf1, a target for sonic hedgehog signaling, causes lung and foregut malformations. Development 128, 2397-2406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahlapuu M., Ormestad M., Enerback S., Carlsson P. (2001b). The forkhead transcription factor Foxf1 is required for differentiation of extra-embryonic and lateral plate mesoderm. Development 128, 155-166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGhee J. D., Fukushige T., Krause M. W., Minnema S. E., Goszczynski B., Gaudet J., Kohara Y., Bossinger O., Zhao Y., Khattra J., et al. (2009). ELT-2 is the predominant transcription factor controlling differentiation and function of the C. elegans intestine, from embryo to adult. Dev. Biol. 327, 551-565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C. C., Kramer J. M., Stinchcomb D., Ambros V. (1991). Efficient gene transfer in C.elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 10, 3959-3970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash B., Colavita A., Zheng H., Roy P. J., Culotti J. G. (2000). The forkhead transcription factor UNC-130 is required for the graded spatial expression of the UNC-129 TGF-beta guidance factor in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 14, 2486-2500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonet M. L., Holgado A. M., Brewer F., Serpe C. J., Norbeck B. A., Holleran J., Wei L., Hartwieg E., Jorgensen E. M., Alfonso A. (1999). UNC-11, a Caenorhabditis elegans AP180 homologue, regulates the size and protein composition of synaptic vesicles. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 2343-2360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes M. B., Christensen R. G., Wakabayashi A., Stormo G. D., Brodsky M. H., Wolfe S. A. (2008). Analysis of homeodomain specificities allows the family-wide prediction of preferred recognition sites. Cell 133, 1277-1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted J. B. (1981). Affinity purification of antibodies from diazotized paper blots of heterogeneous protein samples. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 11955-11957 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormestad M., Astorga J., Carlsson P. (2004). Differences in the embryonic expression patterns of mouse Foxf1 and -2 match their distinct mutant phenotypes. Dev. Dyn. 229, 328-333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormestad M., Astorga J., Landgren H., Wang T., Johansson B. R., Miura N., Carlsson P. (2006). Foxf1 and Foxf2 control murine gut development by limiting mesenchymal Wnt signaling and promoting extracellular matrix production. Development 133, 833-843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton A., Knuth S., Schaheen B., Dang H., Greenwald I., Fares H. (2005). Endocytosis function of a ligand-gated ion channel homolog in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 15, 1045-1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson R. S., Lim L., Ye H., Zhou H., Overdier D. G., Costa R. H. (1997). The winged helix transcriptional activator HFH-8 is expressed in the mesoderm of the primitive streak stage of mouse embryos and its cellular derivatives. Mech. Dev. 69, 53-69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudier N., Lefebvre C., Legouis R. (2005). CeVPS-27 is an endosomal protein required for the molting and the endocytic trafficking of the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Traffic 6, 695-705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M., Sato K., Fonarev P., Huang C. J., Liou W., Grant B. D. (2005). Caenorhabditis elegans RME-6 is a novel regulator of RAB-5 at the clathrin-coated pit. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 559-569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M., Sato K., Liou W., Pant S., Harada A., Grant B. D. (2008). Regulation of endocytic recycling by C. elegans Rab35 and its regulator RME-4, a coated-pit protein. EMBO J. 27, 1183-1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schug J. (2008). Using TESS to predict transcription factor binding sites in DNA sequence. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics Chapter 2, Unit 2.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M. S., Benci J. L., Selote D. S., Sharma A. K., Chen A. G. Y., Dang H., Fares H., Vatamaniuk O. K. (2010). Detoxification of multiple heavy metals by a half-molecule ABC transporter, HMT-1, and coelomocytes of Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One 5, e9564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self M., Lagutin O. V., Bowling B., Hendrix J., Cai Y., Dressler G. R., Oliver G. (2006). Six2 is required for suppression of nephrogenesis and progenitor renewal in the developing kidney. EMBO J. 25, 5214-5228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. E., Fisher P. A. (1984). Identification, developmental regulation, and response to heat shock of two antigenically related forms of a major nuclear envelope protein in Drosophila embryos: application of an improved method for affinity purification of antibodies using polypeptides immobilized on nitrocellulose blots. J. Cell Biol. 99, 20-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J. E., Horvitz H. R. (1977). Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 56, 110-156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram M., Greenwald I. (1993). Genetic and phenotypic studies of hypomorphic lin-12 mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 135, 755-763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng H. T., Shah R., Jamrich M. (2004). Function and regulation of FoxF1 during Xenopus gut development. Development 131, 3637-3647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilm B., James R. G., Schultheiss T. M., Hogan B. L. (2004). The forkhead genes, Foxc1 and Foxc2, regulate paraxial versus intermediate mesoderm cell fate. Dev. Biol. 271, 176-189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnier G. E., Kume T., Deng K., Rogers R., Bundy J., Raines C., Walter M. A., Hogan B. L., Conway S. J. (1999). Roles for the winged helix transcription factors MF1 and MFH1 in cardiovascular development revealed by nonallelic noncomplementation of null alleles. Dev. Biol. 213, 418-431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y., Fares H., Grant B., Li Z., Rose A. M., Clark S. G., Skolnik E. Y. (2003). Genetic analysis of the myotubularin family of phosphatases in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 34380-34386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaffran S., Kuchler A., Lee H. H., Frasch M. (2001). biniou (FoxF), a central component in a regulatory network controlling visceral mesoderm development and midgut morphogenesis in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 15, 2900-2915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzen R. P., Girardot C., Gagneur J., Braun M., Furlong E. E. (2009). Combinatorial binding predicts spatio-temporal cis-regulatory activity. Nature 462, 65-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]