Abstract

Objective

To describe the theoretical principles that guided the establishment of Project Eban’s Community Advisory Boards (CABs), their functions, and composition; the selection and recruitment processes; lessons learned; and recommendations on the use of CABs in multisite HIV clinical trial studies.

Methods

In the first year of Project Eban’s implementation, each of the 4 sites formed a local CAB. Member recruitment took place during the first 6 months of the study. On average, each site’s CAB consisted of 13–19 stakeholders, with a total of 62 members for the multisite study, including leaders of HIV/AIDS-related CBOs, hospital-based HIV/AIDS service providers, HIV/AIDS network leaders in minority communities, CBOs that serve predominantly black communities, and consumers.

Results

Each of the CAB members has expressed a strong commitment to assisting in the conduct of the research. CABs are integral to the success of the study, and their input is highly respected and used to improve the quality of the research.

Conclusions

This article highlights the importance of CABs in the conduct of HIV clinical trials and their roles in making the study culturally congruent to meet the needs of the black community in dealing with the HIV epidemic.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, community advisory boards (CABs) have been increasingly employed in HIV clinical trials, and the composition, structure, and implementation of CABs have been documented in a growing number of biomedical and social behavioral research publications.1-7 “Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research,” also known as the Belmont Report, was created in 1979 by the former US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.8 Since then, it has become an important historical document in the field of medical research because its principles provide the foundation for regulations designed to protect human subjects in clinical trials. CABs have been promoted as an outgrowth of the ethical principles of the Belmont Report. The inclusion of CABs and respect for targeted communities in research have been identified as a necessary step to address the vulnerability of groups of constituencies.9 Weijer and Emanuel10 highlighted that the primary rationale for involving communities is that they have a right to respect and protection based on a true and meaningful partnership with the researchers.

For almost 2 decades, federal grant applications have encouraged and, in some cases, required the inclusion of CABs, especially for all phases of clinical trials in social, behavioral, and biomedical research. In 1987, the National Institute of Mental Health mandated that all AIDS Research Centers should have CABs and a plan to inform the community about developments in research.11 In 1989, the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Division of AIDS first required that a CAB be employed in the conduct of a community-based clinical trial network on treatment for HIV.11 Later, the Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS network also mandated the use of CABs.11 Historically, this mandate underscored the increasingly important role of CAB members as advisors on the design of AIDS clinical trials and supporters in recruitment, participation, and retention. Furthermore, the mandate also reflected compliance with federal regulations, according to which, “a demonstration of community involvement in the decision processes and governance of the offerors is desirable through relevant community membership on governing boards, Institutional Review Boards, or other advisory bodies to the offeror group.”11

Currently, each of the NIAID-sponsored programs is expected to have a local CAB with advisors to review the design of AIDS clinical trials. For example, Valdiserri et al12 used a CAB in a clinical trial to review a variety of experiments conducted with individuals infected with HIV. The CAB consisted of leaders in the gay community, individuals with experience in community health, persons who worked in programs for hemophiliacs and injection drug users, volunteers and health-care workers who cared for infected persons, and families affected by HIV. The findings of this study indicated that the CAB enabled the researchers to maintain excellent relationships with the study population, avoid misunderstandings, and attend to the special needs of the community. Productive experience from this study encouraged and reinforced the use of CABs in other HIV intervention research. In 1991, the CDC issued a request for proposals emphasizing building relationships with community groups and participatory research models. Since then, CABs have been established in large studies, such as the HIV Network for Prevention Trials, created in 1993 to conduct domestic and international phase 1 and 2 clinical trials of HIV vaccines. In the HIV Network for Prevention Trials, CABs were key players in advocating compensation for trial-related injuries and full disclosure of information explaining the benefits and risks associated with trial participation.13 Another large study, the Cost and Services Utilization study at CDC/NIAID Project LinCS (Linking Communities and Scientists), showed that CAB participation facilitated the forging of a true partnership with scientists from the study’s inception.14 In this project, the CAB helped improve the study’s day-to-day operations by reviewing consent forms and any changes in the curricula for the conditions being tested. They also assisted in the development of the brochure and referred potential participants to the study. Their participation was central to the success of the study and to refining the 1-year follow-up retention strategies used to track couples, many of whom had been temporarily lost to follow-up.

Morin et al1 conducted a study to understand how CABs can be used to improve the quality of HIV prevention trials. Qualitative data were collected from 67 CABs and research team members and 6 sites of the HIV Prevention Network. The findings showed that the CABs improved prevention clinical trials by assisting in protocol development, recruitment, and retention and helping to resolve ethical issues. Another successful model was the Chicago HIV Prevention and Adolescent Mental Health Project, a research/community partnership to address elevated rates of HIV/AIDS among adolescents in minority neighborhoods in Chicago,15-18 New York,16,19 and adapted in South Africa and Trinidad.20 Chicago HIV Prevention and Adolescent Mental Health Project was designed and delivered to family units and their adolescent members. In these studies, CABs were partners in all stages of the design and implementation of the research. Findings from the studies showed how CABs played a significant role in all the research stages and influenced the study outcomes.

FUNCTIONS OF THE CAB DEFINED IN THE LITERATURE

The literature has identified several roles for CABs in research. These roles are summarized by Strauss et al6 and others10,21-23 and include (1) acting as a liaison between researchers and the community, (2) expressing community concerns and culture, (3) evaluating information from investigators on risks and benefits of participation in the study and, if applicable, providing recommendations to help potential participants decide whether or not to participate, (4) assisting in the development of study materials, (5) advocating for the rights of minority research study participants, (6) disseminating results to the communities, (7) contributing to sustainability and technology transfer, and (8) ensuring the human protection of research participants, clarifying ethical obligations in participating in research, and providing suggestions on informed consent forms. Moreover, Strauss et al6 and others also underscore the importance of CABs in (1) addressing the growing potential vulnerability of the research participant, (2) protecting against breaches of individual informed consent, and (3) serving to improve research when the CAB provides for ongoing dialogue between the researchers and the community. In addition, CABs can facilitate research by providing advice about the informed consent process and the design and implementation of research protocols, activities that may help stem the number of individual informed consent lapses, and ultimately, benefit study participants and strengthen the scientific integrity of the research in question.6

This article describes the conceptual framework for Project Eban’s CABs, their functions, composition, the process of member selection, interaction, and the communications between CAB members and researchers. In addition, the article will discuss lessons learned and recommendations that can be used in other multisite HIV clinical trials.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR CABS IN PROJECT EBAN

The formulation and functions of the CABs in Project Eban are guided by community-based participatory research (CBPR). We employed CBPR because it offers a paradigm for researchers on how to partner with a community in a way that can improve the quality of the research and help the community to address HIV-related problems.24 The overarching aim of CBPR is to increase knowledge and understanding of a given phenomenon and use the knowledge obtained in interventions and to change policies to improve the health and quality of life of community members.25,26

Seven principles of CBPR guide most CAB formulations and functions. These principles were presented by Israel et al25 based on an extensive literature review. The principles suggest that CBPR (1) recognizes the community as a unit of identity and builds on strengths and resources within that community; (2) facilitates a collaborative, equitable partnership in all phases of the research; (3) engenders involving, empowering, and power-sharing processes that ameliorate social inequality; (4) fosters colearning and capacity building among all partners; (5) integrates a balance between knowledge generation and intervention for mutual benefit for all parties focused on the local relevance of public health problems; (6) involves systems development using a cyclical and interactive process; and (7) disseminates results to all partners and has them involved in the dissemination process. The literature shows that these principles can be considered on a continuum, and the ideal is to attempt to use as many as possible. Thus, the creation, mission, functions, and roles of Eban’s CABs were guided by these 7 principles.

The orientation of CBPR, which emphasizes involvement of the community in research, is extremely critical to our work. A CBPR approach is especially useful in studies that involve sensitive issues such as sexual behavior and substance abuse, which are intrinsically intertwined with HIV transmission. Furthermore, a CBPR approach is a constructive tactic to take when researchers are perceived as outsiders and in cases where the community has previously undergone extensive study without benefit. People of color have been asked to participate in countless studies without involving their communities in the research process and without obtaining community input for all aspects of the study. Such individuals often have doubts about researchers and may reject the notion of being the “subject” of a study. Moreover, historical events, such as the Tuskegee Experiment, have led many black communities to distrust all forms of medical and social research. To overcome these issues, CABs and community involvement are extremely valuable to social science and CBPR because they ensure that voices of the targeted communities are reflected in the research and that the study benefits these communities.

Community, in the context of CBPR, is defined as a unit of people who share a sense of identification and emotional connectedness.25 For example, it can be defined as all the people who are affected by the problem, such as consumers, residents of a local area, health practitioners, agencies, and policy makers.27

RECRUITMENT OF CAB MEMBERS

In the first year of Project Eban’s implementation, the 4 sites (in New York City, Philadelphia, Atlanta, and Los Angeles) formed a local CAB and recruited members during the first 6 months of the study. We made an effort to unite different partners with diverse expertise, knowledge, and skills regarding the effects of HIV on the community. We also sought out individuals who were willing to make time in their schedules to engage in the CBPR because they have a strong commitment to addressing the complex issues and problems of HIV in their community.

Several strategies were used to recruit CAB members. We (1) approached several individual consumers who had participated in the initial focus groups or in the pilot study of the intervention; (2) mailed letters or invitations with information about the study to leaders in the HIV field, CBO community, faith-based organizations, HIV medical care providers, and other service agencies to attend an informational meeting about the project; (3) reviewed an existing database of former advocates and CAB members who served on previous projects and mailed them the invitational letter; (4) circulated flyers to pertinent organizations about recruitment of the CAB; and (5) accepted referrals via word of mouth from colleagues and associates.

On an individual’s agreement to participate, a screening assessment was conducted to evaluate whether he or she met the following CAB inclusion criteria: (1) identifies as being black or African American or works in organizations that serve black individuals; (2) is older than 18 years; (3) expresses a strong commitment to sustaining and strengthening black communities and is willing to help reduce the spread of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in these communities; (4) endorses Project Eban research; (5) understands and accepts the roles of the CAB as defined in the Eban CAB protocol; (6) has had some experience in working or volunteering in clinical practice, research, or advocacy in the area of HIV/AIDS; and (7) is willing and available to commit to attending a minimum of 3 meetings per year for at least 2 years and, preferably, a commitment for the duration of the study. No formal consent was used for the CAB. However, each site provided an informal consent on the purpose of the CAB, rules and functions, attendance, and compensation.

The inclusion criteria for Eban’s CAB members specified that we sought individuals who either identified themselves as black or African American or worked in agencies that serve a predominantly black community. We used such criteria to ensure that the members understand the cultural and political contexts and the needs of the specific community from which the study participants are recruited.

Although the attendance rate at CAB meetings has been high overall and turnover among the members is not excessive, we have continued to recruit members to replace those who have left. Some sites lost more than a few members due to closure of several community-based organizations after funding streams changed or decreased.

Bringing in new members who meet the inclusion criteria has also extended our contacts in the community beyond those of the existing members. Additional CAB members were added from churches during the third year of the study because we found that the CAB’s composition lacked sufficient representation from faith-based organizations.

We faced 2 major challenges in recruiting CAB members. First, we lost a few members who met the criteria, but who felt that the resources we offered and the compensation were not sufficient. Second, when we were establishing the CAB during the initial implementation of the study, several members recommended that a peer also be selected to participate on the board. In a few cases, the peer did not meet the protocol inclusion criteria, and this created disappointment among the CAB members who referred them. When the request was not fulfilled, these CAB members became dissatisfied and 1 left the CAB. Several other CAB members expressed displeasure when ineligible couples who they had referred were not enrolled in the study.

COMPOSITION OF THE CABS IN PROJECT EBAN

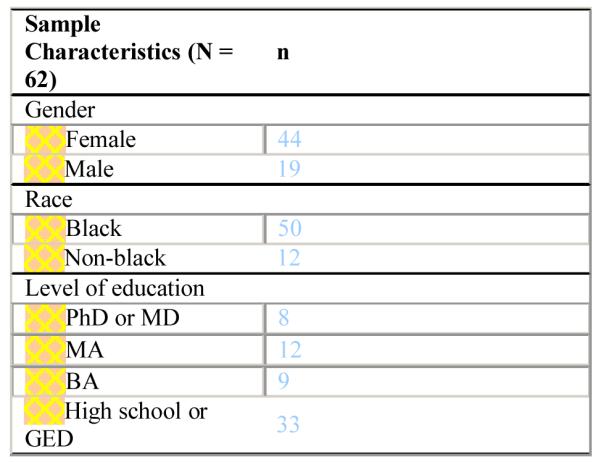

Eban’s CAB members from the 4 sites totaled 62, with each site’s CAB having between 13 and 19 stakeholders. Demographics of the CAB members are described in Table 1. The majority was black and the boards were predominantly female. More than half completed high school or had a GED and 13% had a graduate degree (MD, PhD). CABs were comprised stakeholders and representatives of the community under study, including persons living with HIV (consumers), advocacy groups, spiritual leaders recruited from black churches, political leaders, health-care providers who specialize in providing care for persons living with AIDS, and various CBOs (agencies providing services to persons living with AIDS, social services to black couples and families, and those that provide substance abuse, health, and mental health treatment). On average, there are 3–4 consumers (couples who participated in the pilot Eban study) in each CAB. All members of the CABs understand the needs of the urban black communities that they represent and are committed to finding the best solutions to fight the AIDS epidemic in their midst.

TABLE 1.

Background of Eban Project CAB

|

FORMAT OF THE CAB

CABs meet once a month at the research site or in the agencies or community organizations represented by the CAB members. The meetings are conducted by the project director and research staff. To ensure standardization and consistency, summaries of the meetings and a process measure are used to capture the activities. The process measure, which is completed by the project director who conducts the CAB meetings, includes information on member attendance, the meeting’s agenda, topics discussed, and plans for future actions. After each meeting, the project director shares this form with the site PI. The information is used to evaluate the functions of the CAB in shaping the study’s implementation. PIs from the 4 sites and other researchers participate in regular conference calls. About once a month during these calls, each site’s project director reports on the role of his or her CAB. By sharing experiences across sites, researchers involved in Eban learn from each other about practices within the CABs.

COMPENSATION

CAB members are compensated $50 per meeting for their time. Compensation may play a crucial role in recruitment of the CAB and results in high attendance at the meetings. However, compensation is not the only motivating factor for individuals to commit to assisting in Project Eban’s research process. Members have said that they believed that the project uniquely responds to the needs of their community and serves as a road map on culturally congruent HIV interventions for black couples. The high level of participation and engagement of the members attests to the dedication of the CAB to the success of the project.

MECHANISMS INVOLVED IN HELPING THE CAB TO ACHIEVE ITS PURPOSE

The project director provides the training to members and serves as the key point person to the CAB. At each site, we provide CAB members with training on their roles in all stages of the research study, rules, expectations, terms of serving on the CAB, confidentiality issues, and communication structures (such as how information is presented in the CAB, consensus-building skills, and how conflicts can be resolved).

In order for the CAB members to work efficiently, we also provide infrastructure support such as access to (1) the study’s marketing materials; (2) a desk and phone line at our site offices to expedite their contacts with CBOs for potential recruitment of participants; (3) individual consultations with the project director and the PI, beyond what they receive as a group; and (4) an honorarium to compensate for expenses related to attending the CAB meetings. We also found that rotating the location of meetings in members’ neighborhoods or the agencies where they work has increased the likelihood of participation.

On an ongoing basis, CAB members are recognized for their unique contributions, and for what each one brings to the board. People are treated with respect, and their overall contribution is appraised and acknowledged publicly among the other members. The project director frequently emphasizes that the CABs bring community voices into play at all stages of implementing the research.

CAB ROLES AND FUNCTIONS

Major roles that the CAB members play include advising the researchers and giving feedback on the content of the questionnaires, intervention content, training, and recruitment and retention of couples in the study. Their feedback has proven valuable for the integrity of the research and ensures that the voices of participants are reflected in the study design and implementation.

At the beginning of the study implementation, the CAB provided feedback on marketing materials for recruitment, the intervention protocol, and the baseline and follow-up questionnaires. They reviewed the language and meaning of the items, intervention content, facilitator training protocols, and human subject issues. The CABs shaped the language used in marketing the study and the wording of questions for the baseline and follow-ups, and ensured that the questions were culturally congruent and nonoffensive. CAB members conducted mock interviews with each other to examine the face validity of the questionnaires and timing. Their feedback was incorporated into the final version of the questionnaires.

The CABS also role-played the exercises and games to confirm that they were entertaining. Their feedback was invaluable, and the role-play process allowed them to “put themselves into” a session or 2 and to have firsthand experience with the quantity and quality of the information that the sessions provided.

The CAB reviewed the IRB protocols and made suggestions regarding the language used in the protocols to avoid stigmatizing the community. For example, the CAB recommended that the IRB protocol should specify that the study is not only about reducing HIV risks but also about improving healthy relationships among black couples and about learning strategies for a healthy lifestyle.

After the CABs reviewed the intervention content for each session including the exercises and homework assignments, they provided useful feedback on some of the language used to make it more culturally congruent. For example, they commented on use of the principles of Nguzo Saba, interpreted what “black values” mean in their lives, and described ways of coping with HIV. In addition, they provided suggestions on how to integrate value issues into HIV prevention strategies. Their comments were also incorporated into the intervention and training protocols. For example, for the intervention’s homework assignments, CAB members suggested role-play scenarios that replicated real-world situations that black heterosexual couples face in HIV risk reduction.

The CABs at each of the sites were instrumental in marketing the study to black communities and helped us in gaining access to organizations for recruitment. For example, at 1 site, several CAB members used their religious affiliations to contact specific churches and convinced them to allow us to market the study to their congregations. CAB members also attended community activities and street fairs to market Project Eban. Across all the sites, CAB members invested in making recruitment and retention very successful.

Once the study is completed, CAB members will be invited to join the researchers as panelists to present the findings at local community-based organizations and in community forums. Representatives from the CAB will also be invited to attend scientific meetings where they will have an opportunity to provide their insights into the findings. The number of scientific meetings that CAB members might attend depends on the availability of venues interested in learning about the findings. Moreover, for papers, particularly those on the recruitment process and retention, CAB members will be invited to review the documents and provide comments on their content.

CHALLENGES FACED IN MANAGING A BOARD

There was an initial lack of consensus among CAB members on a few issues addressed in the meetings that required extensive discussions before agreement could be reached. For example, when the baseline questionnaire was reviewed, there was no consensus on how questions should be asked on race and ethnicity. Several CAB members tried to impose their approaches on others. In a few cases, drifts from the stated roles and functions of a CAB member occurred when an individual attempted to get involved in issues beyond his or her role and challenged the science of the research. In a case, a member was extremely critical of randomization and requested that the 2 arms be a matter of choice. In another, a member wanted to ensure that the couples who she referred were assigned to the HIV risk reduction arm and not to the health promotion arm. Differences of opinion were not managed well at first, which led to conflict and discomfort among a few members. This was rectified by having the principal investigator attend the next meeting and clarify the use of scientific methods for some of the board members and reiterate the mission and purpose of the study.

LESSONS LEARNED AND RECOMMENDATIONS

From our experiences with the CABs in Project Eban, we have learned a few lessons that are important to highlight.

Provide Resources for the CAB to Achieve Their Mission and Increase Retention and Participation

To have an effective CAB, it is crucial to have infrastructure support in place (eg, sufficient study marketing materials, desks and a phone line at our site offices so that the CAB member can place calls to potential recruitment settings, individual consultations with the project director, and an honorarium to compensate for expenses incidental to the CAB meetings). To increase participation and community networking, it is also useful to rotate the meeting’s location in members’ neighborhoods or the agencies where they work. Project Eban is a multisite study in 4 widely dispersed US locations, and as such, we did not plan for a face-to-face group meeting of CAB members from all 4 sites. In the future, we believe that it would be useful to budget for at least 1 such meeting or to arrange to hold at least 1 teleconferencing session for all 4 CABs. For multisite studies, face-to-face meetings or teleconferencing among CABs would lead to a stronger level of commitment and cross-fertilization of ideas.

Provide Compensation for CAB

We are aware that compensation played a crucial role in recruitment of the CAB and increased high attendance at the meetings. Although financial compensation was not the only benefit that individual CAB members derived from their commitment to assisting in this research, we found that it served as a form of recognition of their contribution. Most CAB members had full-time jobs, and the honorarium acknowledged that their attendance and work on behalf of Project Eban was outside of their job responsibilities. At one of the sites, a pharmaceutical company offered to pay for catering a hot lunch for members at each CAB meeting. This benefit was greatly appreciated by the CAB members.

Develop a Dialogue and Lines of Communication

We opened both formal and informal lines of communication between the CABs and the project director. An example of communication was that the project director sent the CAB member or his or her organization a thank-you note when they referred a couple; this occurred even if the couple did not meet the study criteria. The CAB member and organization appreciated the update and the acknowledgment that the couple had been contacted.

The importance of building and sustaining an ongoing dialogue and training CAB members on how to deal with differences is critical to getting the most out of a CAB’s efforts. The skill of the project director in handling conflicts in groups such as the CAB is pivotal. Ongoing respectful discussion provides a forum for finding common ground and constructing a collective vision. It is important to acknowledge and accept differences and provide training on effective communication skills.

Ensure That Expectations, Roles, and Functions of the CAB Are Clear in the Study’s Initial Stages and on an Ongoing Basis

The project director must make sure that CAB members understand expectations, roles, and mechanisms of communication. These topics may need to be revisited over time.

Evaluate the CAB Partnership Process on an Ongoing Basis

In Project Eban, we used a single process measure to evaluate the content, issues, and progress of the CAB meetings. Collecting qualitative data on an ongoing basis through a process measure captures what takes place in the CAB and can be used systematically to improve the functions and roles. It can also be used to standardize roles across sites in multisite studies. Quantitative methods on CAB functions, roles, and progress were not used in Eban; however, we suggest that in future multisite research, quantitative data should also be collected on an ongoing basis by both CAB members and researchers to better understand CABs’ functions and their contribution to the study outcomes.

Be Specific About the Population and the Communities That the Study Targets

Researchers must inform the CAB members that the inclusion criteria for participation must be strictly followed and adhered to in all phases of the research. By being clear about the inclusion criteria, researchers avoid a situation where CAB members may become displeased when ineligible couples who they had referred are not enrolled in the study.

Give the CAB a Clear Understanding of the Research Purpose, Mission, Meaning of a Clinical Trial, and Randomization Used in the Study

Our experience with CAB members who became frustrated after couples who they had referred were determined ineligible is a lesson learned and an issue that was revisited numerous times at all sites. The CAB member may have been aware that the couple was engaging in unprotected sex or other high-risk behaviors, but the couple may not have disclosed this in the screening process. Even when asked specifically, some couples were reluctant to admit that they were not using condoms. Consequently, the CAB member felt that the research team was rejecting people who really needed the intervention. CAB members also referred couples who were a few months short of being together for 6 months. When we recontacted the couple at the point that they did meet the 6 months criteria, several couples were no longer interested. Finding a couple ineligible often impacted on the CAB member who referred them. The CAB member wanted his or her judgment to outweigh the study criteria. It is important to make sure that all CAB members understand the meaning of randomization and the purpose of efficacy trials. This would have avoided the extensive discussion at several Eban CAB meetings in which a few members were dissatisfied with couples being found ineligible or assigned to different intervention arms than they thought appropriate.

Explain the Notion of “Being Blinded” in a Clinical Trial

The Project Director explained to CAB members in the initial meeting that the study outcomes would not be analyzed and shared until the completion of the research. Nevertheless, several members requested information about the study’s outcomes during the course of the trial. This issue has arisen multiple times at several sites. Because of the great need for a culturally congruent intervention such as Eban, some CAB members expressed a desire to have the intervention disseminated to the black community after the first year. The notions of being blinded to the findings before completion of the study and not sharing findings prematurely had been explained to the CAB; however, CAB members needed to be reminded on an ongoing basis that everyone, including the researchers and staff, are blinded to the findings at present and that the results will be shared at the completion of the study.

Provide Training to the Project Directors on How to Conduct the CAB

We learned that training researchers and, in particular, training the project director on the CBPR conceptual model helps to guide the CAB formulation and functions. Training the project directors on how to conduct CAB meetings must be an integral part of the study protocol. This may include formal training and ensuring that the researchers have read the literature on CABs and their functions. It is crucial that the project director, who conducts the CAB meetings, has had experience in leading groups to know how to engage the CAB members and resolve conflicts.

CONCLUSIONS

Consistent with the literature, the recruitment, functions, and roles of Eban’s CABs are guided by the principles of CBPR. CBPR principles emphasize and recognize the need to involve the community in the research in a meaningful way to ensure that the research fits the needs of black communities and that the assessment, intervention, facilitation, and study recruitment protocols are culturally congruent. CBPR principles also ensure that the study participants’ human protection is addressed adequately in all stages of the research.

There are several challenges and lessons learned in Project Eban that need to be underscored. These lessons are related to the CABs recruitment, functions, and roles. Lessons learned emphasize that to have a successful CAB, researchers must (1) provide the CAB with sufficient resources to achieve its mission and increase retention and participation; (2) provide compensation for CAB members; (3) develop a dialogue and increase the consensus-building skills of CAB members; (4) clearly delineate expectations, roles, and functions of the CAB in the initial stage and clarify on an ongoing basis; (5) evaluate the partnership process between the CAB and the research team on an ongoing basis; (6) be specific about the population and the communities that the study targets; (7) make certain that the CAB has a clear understanding of the research purpose and mission, the meaning of a clinical trial, and randomization used in the study; (8) ensure that the CAB understands the notion of being blinded during the research process in a clinical trial; and (9) train and support the project director in how to conduct a successful CAB. Paying attention to all these issues will help ensure a successful and highly productive CAB in future HIV clinical trials.

CABs have made significant contributions to all stages of the Project Eban study. Their feedback has helped improve the quality and cultural competence of the research protocols, including the recruitment, assessment, and intervention materials. The CABs have also played an important role in establishing the study’s visibility in black communities. Members were able to communicate the risks and benefits of participating in Project Eban in a convincing and credible manner. The high participation and retention rates and positive engagement of the CABs attest to the level of the members’ commitment to Eban and its significance to the black communities involved in the study.

CAB members have stated that they believe that Eban fits the needs of black communities and pays attention to black cultural, social, and political contexts (eg, black community values, history of oppression, poverty, discrimination, stigma, history of trauma) and how these contexts are related to HIV risk behaviors and the lifestyles of black people. CAB members appreciate that the Eban recruiters, assessors, and facilitators were black and that they exhibited a remarkable commitment to making a difference in their community. The cultural context of the assessment and intervention and all study protocols are discussed in earlier chapters in this special issue. After the completion of the study, the CABs will remain active and influential in interpreting the findings. Several CAB members will be involved in presenting the findings at community meetings and conferences. Moreover, if the Eban intervention is found to be efficacious, the CAB will be involved in future research on the adoption and dissemination of Eban in the black community. CAB members have emphasized the need to bring the findings back to the community and have said that understanding how the community adopts the intervention should be studied as well. CAB members have also acknowledged that their participation provides them with an opportunity to help their community, which is seriously affected by HIV, and learn about the process of conducting research and clinical trials. Belonging to the board also has given them an opportunity to network and collaborate with other key members to better serve and advocate for their communities. From comments expressed by members of Eban’s CAB at several of the sites, participating in a CAB gave these individuals a great deal of inside information about clinical trials, and they believe that their experience can be generalized to other studies. As a result, they are eager to participate in other trials. We believe that this is the highest form of praise—CAB members have enjoyed and learned from the CAB process and intend to apply their new knowledge by volunteering to be on a board for future clinical trials.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morin S, Maiorana A, Koester K, et al. Community consultation in HIV prevention research: a study of community advisory boards at 6 research sites. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:513–520. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox L. Community advisory boards: HIV infected peer mentors and partners in planning care. Disch Plann Update. 1994;14:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox L, Rouff J, Svendsen K, et al. Community advisory boards: their role in AIDS clinical trials. Health Soc Work. 1998;23:290–297. doi: 10.1093/hsw/23.4.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madison S, McKay M, Paikoff R, et al. Basic research and community collaboration: necessary ingredients for the development of a family-based HIV prevention program. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12:281–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosnow R, Borus M Rotheram, Ceci S, et al. The institutional review board as mirror of scientific and ethical standards. Am Psychol. 1993;48:821–826. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strauss R, Sengupta S, Quinn S, et al. The role of community advisory boards: involving communities in the informed consent process. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1938–1943. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winn R. Obstacles to the accrual of patients to clinical trials in the community setting. Semin Oncol. 1994;(suppl 7):112–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. OPPR Reports: NIH PHS RHS. 1979. pp. 1–18. [PubMed]

- 9.Weijer C. Protecting communities in research: philosophical and pragmatic challenges. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 1999;8:501–513. doi: 10.1017/s0963180199004120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weijer C, Emanuel E. Protecting communities in biomedical research. Science. 2000;289:1142–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services US Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS (Request for Proposal No.1, NIH NIAID AIDSP 89 11, January 17, 1989) 1989

- 12.Valdiserri R, Tama G, Ho M. The role of community advisory committees in clinical trials of anti-HIV agents. IRB Ethics Hum Res. 1988;10:5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.HIV Network for Prevention Trials [Accessed October 30, 2007];What is HIVNET? Available at: http://www.scharp.org/ceg/whatis.html.

- 14.Blanchard L. Community assessment and perceptions: preparation for HIV vaccine efficacy trials. In: King N, Henderson G, Stein J, editors. Beyond Regulations: Ethics in Human Subjects Research. University of North Carolina Press; Chapel Hill, NC: 1999. pp. 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCormick A, McKay M, Wilson M, et al. Involving families in an urban HIV preventive intervention: how community collaboration addresses barriers to participation. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12:299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baptiste D, Paikoff R, McKay M, et al. Collaborating with an urban community to develop an HIV and AIDS prevention program for black youth and families. Behav Modif. 2005;29:370–416. doi: 10.1177/0145445504272602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McBride C, Baptiste D, Paikoff R, et al. Family-based HIV preventive intervention: child level results from the CHAMP family program. Soc Work Ment Health. 2007;5:203–220. doi: 10.1300/J200v05n01_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baptiste D, Blachman D, Cappella E, et al. Transferring a university-led HIV/AIDS prevention initiative to a community agency. Soc Work Ment Health. 2007;5:269–293. [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeVoe ER, Dean K, Joyce E, et al. A multiple-family group HIV prevention program for drug-involved mothers and their young children. J HIV/AIDS Soc Serv. 2004;3:27–46. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baptiste DR, Bhana A, Petersen I, et al. Community collaborative youth-focused HIV/AIDS prevention in South Africa and Trinidad: preliminary findings. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:905–916. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King N. Medical research: using a new paradigm where the old might do. In: King N, Henderson G, Stein J, editors. Beyond Regulations: Ethics in Human Subjects Research. University of North Carolina Press; Chapel Hill, NC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galea S, Factor S, Bonner S, et al. Collaboration among community members, local health service providers, and researchers in an urban research center in Harlem, New York. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:530–539. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.6.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quinn S. Protecting human subjects: the role of community advisory boards. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:918–922. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;82(suppl 2):ii3–ii12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Israel BA. Commentary: model of community health governance: applicability to community-based participatory research partnerships. J Urban Health. 2003;80:1099–3460. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green L. Can public health researchers and agencies reconcile the push from funding bodies and the pull from communities? Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1926–1929. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]