Abstract

A pharmacological dose (2.5–10 μM) of 17α-estradiol (17α-E2) exerted a cytotoxic effect on human leukemias Jurkat T and U937 cells, which was not suppressed by the estrogen receptor (ER) antagonist ICI 182,780. Along with cytotoxicity in Jurkat T cells, several apoptotic events including mitochondrial cytochrome c release, activation of caspase-9, -3, and -8, PARP degradation, and DNA fragmentation were induced. The cytotoxicity of 17α-E2 was not blocked by the anti-Fas neutralizing antibody ZB-4. While undergoing apoptosis, there was a remarkable accumulation of G2/M cells with the upregulation of cdc2 kinase activity, which was reflected in the Thr56 phosphorylation of Bcl-2. Dephosphorylation at Tyr15 and phosphorylation at Thr161 of cdc2, and significant increase in the cyclin B1 level were underlying factors for the cdc2 kinase activation. Whereas the 17α-E2-induced apoptosis was completely abrogated by overexpression of Bcl-2 or by pretreatment with the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk, the accumulation of G2/M cells significantly increased. The caspase-8 inhibitor z-IETD-fmk failed to influence 17α-E2-mediated caspase-9 activation, but it markedly reduced caspase-3 activation and PARP degradation with the suppression of apoptosis, indicating the contribution of caspase-8; not as an upstream event of the mitochondrial cytochrome c release, but to caspase-3 activation. In the presence of hydroxyurea, which blocked the cell cycle progression at the G1/S boundary, 17α-E2 failed to induce the G2/M arrest as well as apoptosis. These results demonstrate that the cytotoxicity of 17α-E2 toward Jurkat T cells is attributable to apoptosis mainly induced in G2/M-arrested cells, in an ER-independent manner, via a mitochondria-dependent caspase pathway regulated by Bcl-2.

Keywords: 17α-Estradiol, G2/M arrest, Apoptosis, Mitochondrial cytochrome c, Caspase cascade, Bcl-2, Leukemia cells

Introduction

Since the hypoestrogenic state associated with menopause may cause multiple defects in estrogen-dependent cells and tissues, estrogen replacement therapy can be used to recover the physiological level of estrogen in postmenopausal women. The amelioration of normal brain functions by attenuating the injury and cell death of brain, under neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer's disease and stroke, is among the important benefits of estrogen replacement therapy (Paganini-Hill and Henderson, 1994; Alonso de Lecinana and Egido, 2006). In the neuroprotective activity of estrogens, three different mechanisms are likely to be implicated; one is the intracellular estrogen receptor (ER)-mediated genomic mechanism, the second is the plasma membrane ER-mediated nongenomic mechanism that is associated with cell signaling pathways, and the third is the ER-independent mechanism (Behl and Holsboer, 1999; Wise, 2003). The ER-mediated genomic action of estrogens is elicited by their binding with specific nuclear receptors, estrogen receptor α (ERα) and β (ERβ) and the subsequent transcriptional regulation of gene expression (Evans, 1988). The plasma membrane ER-mediated action of estrogens rapidly triggers second messenger signaling events, in which activated ERs do not directly alter target gene expressions. The ER-independent action of estrogens is induced at pharmacological concentrations (in the micromolar range), and not blocked by ER antagonists such as ICI 182,780 or tamoxifen (Wise et al., 2001a). The role of estrogens, at pharmacological doses, is known to be a potent antioxidant action by which neurons can be protected from oxidative cell death (Behl et al., 1997; Culmsee et al., 1999). 17β-Estradiol (17β-E2), the predominant and most biologically active estrogen, is an important neuroprotective estrogen, based on its capability at physiological concentrations (in the nanomolar range) to reduce neuronal apoptosis in various in vivo and in vitro neurodegenerative conditions (Behl et al., 1998; Wise et al., 2001b). However, 17β-E2, by the ER-mediated mechanism, possesses proapoptotic effects on bone-resorbing osteoclasts (Kameda et al., 1997) and thymocytes (Okasha et al., 2001). These results suggest that the apoptotic regulatory activity of 17β -E2 may differ depending upon the types of target cells.

On the other hand, 17α-estradiol (17α-E2), which is a stereoisomer of 17β-E2 and fails to interact effectively with ER, has long been considered to be hormonally inactive and thus, little attention has been paid to its roles. Recently, it has been indicated that 17α-E2 is as potent as 17β-E2 in protecting neurons from toxic stress conditions (Dykens et al., 2005). This neuroprotective action of 17α-E2 is mediated by ER-independent nongenomic mechanisms that include the prevention of oxidative stress, stabilization of membrane, and retention of mitochondrial integrity. Thus, the clinical application of 17α-E2, as a neuroprotective therapeutic agent, is expected to be more beneficial than 17β-E2, in that 17α-E2 possesses low genomic effects and equipotent nongenomic effects when compared to 17β-E2, leading to the circumvention of adverse effects of 17β-E2. In relation to the cytoprotection of 17β-E2 toward malignant tumor cells, several studies have indicated that 17β-E2 establishes a survival advantage in an ER-dependent manner, which thus increases the risk of hormone-responsive breast or endometrial cancers (Razandi et al., 2000; Fernando and Wimalasena, 2004). In ER-positive breast cancer cells, a physiological dose of 17β-E2 can suppress apoptosis by a plasma membrane ER-dependent Ras signaling pathway (Fernando and Wimalasena, 2004). In addition, 17β-E2 (50 μM) appears to inhibit the proliferation of breast cancer cells by microtubule disruption, irrespective of the presence of ERs (Aizu-Yokota et al., 1994). Against human leukemia cell lines, 17β-E2 has exhibited various IC50 values ranging between 25 μM and N100 μM (Blagosklonny and Neckers, 1994). After treatment with 17β-E2 (400 μM), Jurkat T cells undergo apoptosis by suppressing the levels of Bcl-2 and cyclin A (Jenkins et al., 2001). These previous data have suggested that 17β-E2 stimulates the survival and proliferation of cancer cells at the physiological dose, via the ER-dependent mechanism, whereas 17β-E2 inhibits cancer cell proliferation at the pharmacological dose by inducing apoptosis or microtubule disruption, independently of the ER. However, little is known about the effect of 17α -E2 on tumor cell proliferation.

In order to investigate how 17α -E2 affects tumor cells through the ER-independent mechanism at pharmacological doses, we have investigated the effect of 17α -E2 (2.5–10 μM) on human leukemias Jurkat T cells and U937 cells, both of which are known not to express ERs (Danel et al., 1985). The results demonstrate that 17α-E2 (5–10 μM), but not 17β-E2, can induce apoptosis in Jurkat T cells, via mitochondrial cytochrome c release and resultant activation of caspase cascade, which is mainly provoked in G2/M-arrested cells.

Materials and Methods

Reagents, antibodies, and cells

17α-E2, 17β-E2, RU486, and hydroxyurea were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, Mo, USA). The broad-range caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). The estrogen receptor antagonist ICI 182,780 (Wakeling et al., 1991) was purchased from Tocris Cookson Ltd (Northpoint Fourth Wasy, Avonmouth, BS11 8TA, UK). An ECLWestern blotting kit was purchased from Amersham (Arlington Heights, IL, USA). The anti-cytochrome c antibody was purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA), and anti-PARP, anti-Bcl-2, anti-Bcl-xL, and anti-β-actin were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti-caspase-8, anti-caspase-9, anti-p-cdc2 (Tyr15), anti-p-cdc2 (Thr161), and anti-p-Bcl-2 (Thr56) were purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA, USA), and monoclonal anti-caspase-3, anti-Fas and anti-FasL antibodies were purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY, USA). The anti-Fas agonistic antibody CH-11 and the anti-Fas neutralizing antibody ZB-4 were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology Inc. (Lake Placid, NY, USA) and MBL international Corp (Watertown, MA, USA), respectively. Human acute leukemia Jurkat T cell clones, transfected with the Bcl-2 gene (JT/Bcl-2) and with the vector (JT/Neo) were supplied by Dr. Dennis Taub (Gerontology Research Center, NIA/NIH, Baltimore, MD, USA). Jurkat T cell clone E6.1 and human monoblastoid cell line U937 were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). Jurkat T cells as well as U937 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) containing 10% FBS (UBI, Lake Placid, NY, USA), 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 5×10−5 M β-mercaptoethanol, and 100 μg/ml gentamycin.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxic effect of 17α-E2 on Jurkat T cells was analyzed by the MTT assay reflecting cell viability. For the MTT assay, Jurkat T cells (5×104) were added to the serial dilution of 17α-E2 in 96-well plates. After incubation for 20 h, 50 μl of the MTT solution (1.1 mg/ml) was added to each well and incubated for an additional 4 h. The colored formazan crystal, produced from the MTT, was dissolved in 150 μl DMSO. The OD values of the solutions were measured at 540 nm using a plate reader.

DNA fragmentation analysis

Apoptotic DNA fragmentation, induced in Jurkat T cells following 17α-E2 treatment, was determined, as previously described (Jun et al., 2003). Briefly, the cells were harvested by centrifugation and then treated with a lysis buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4) for 20 min on ice. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected and treated for 2 h at 50°C with proteinase K and subsequently with RNase for 4 h at 37°C. After extraction with an equal volume of the buffer-saturated phenol, the DNA fragments were precipitated with 2.5 volumes of ethanol in the presence of 0.5 M NaCl and visualized following electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel.

Flow cytometric analysis and nuclear staining with DAPI

The cell cycle progression of Jurkat T cells following 17α-E2 treatmentwas analyzed by flow cytometry. After fixation with 67% ethanol at 4°C, the cells (1×106) were washed with the phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended with 12.5 μg of RNase in 250 μl of 1.12% sodium citrate buffer (pH 8.45). Incubation continued at 37°C for 30 min before the cellular DNA was stained with 250 μl of propidium iodide (PI) (50 μg/ml) for 20 min. The stained cells were analyzed using a FACScan flow cytometer. The extent of necrosis was detected with an Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Kit (Clontech, Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). The cells (1×106) were washed with 1× binding buffer and then incubated with Annexin V-FITC and PI for 15 min before being analyzed by flow cytometry, according to the manufacturer's instructions. For nuclear staining with DAPI, the ethanol-fixed cells were washed with PBS, and stained with 1 μM DAPI solution for 10 min. The nuclear morphology was observed and photographed using a Nikon Microphot Fluorescence Microscope.

Preparation of cell lysate and Western blot analysis

Cell lysates were prepared by suspending 5×106 Jurkat T cells in 300 μl of the lysis buffer (137mMNaCl, 15mMEGTA, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 15 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 25 mM MOPS, 1 mM PMSF, 2.5 μg/ml proteinase inhibitor E-64, pH 7.2). Cells were disrupted by sonication and extracted for 30 min at 4°C. An equivalent amount of protein lysate (20–30 μg) was electrophoresed on a 4–12% SDS gradient polyacrylamide gel with 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid buffer. The proteins were electrotransferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA, USA). The detection of each protein was carried out with an ECL Western blotting kit (Amersham, Heights, IL, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Densitometry was performed by using ImageQuant TL software (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA). Arbitrary densitometric units of the protein of interest were corrected for the densitometric units of β-actin.

Detection of mitochondrial cytochrome c release in cytosolic protein extracts

In order to assess 17α-E2-mediated mitochondrial cytochrome c release in Jurkat T cells, cytosolic extracts were obtained as described previously (Jun et al., 2003). Briefly, ∼5×106 cells were suspended in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (250 mM sucrose, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 2.5 μg/ml E-64, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2) for 30 min at 4°C to swell, and were then homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer with 20 strokes. The homogenates were centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatants were centrifuged at 13,700 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatants were harvested as cytosolic extracts free of mitochondria, and analyzed for mitochondrial cytochrome c release.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis

Ten micrograms of total RNA for the control and each sample was transcribed using Superscript II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and Random Hexamer, following the manufacturer's instructions. PCR amplification was performed with AccuPrime™ Tag DNA polymerase high fidelity (Invitrogen) and the specific primers for each target gene (Table 1). To ensure that the same amount of RNAwas being used, the concentration of the total RNA for each sample was confirmed by spectrophotometry and normalized with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the message of a housekeeping gene. The PCR products were electrophoresed using 1.0–1.9% agarose gels and visualized after ethidium bromide staining under UV. Statistical analysis. Unless otherwise indicated, each result in this paper is representative of at least three separate experiments. The values represent the mean ±standard deviation (SD) of these experiments. Statistical significance was calculated with Student's t-test. p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Table 1. Gene-specific primer sequences used for RT-PCR.

| Gene name | Primer | Primer sequences (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| cdk4 (NM_000075) | Forward | CTAGGATCCATGGCTACCTCTCGA |

| Reverse | GCGAATTCAGCTCCGGATTACCTT | |

| cyclin A, CCNA1 (NM_093914) | Forward | AGATCTATGGAGACCGGCTTTC |

| Reverse | AGATCTGCTTCCATTCAGAAAC | |

| cyclin B, CCNB1 (NM_031966) | Forward | ACGGAATTCATGGCGCTCCGAG |

| Reverse | TCGGATCCTCACCTTTGCCACAGCC | |

| GAPDH | Forward | CGTGGAAGGACTCATGACC |

| Reverse | TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA |

Results

Effect of 17α-E2 and 17β-E2 on Jurkat T cells or U937 cells

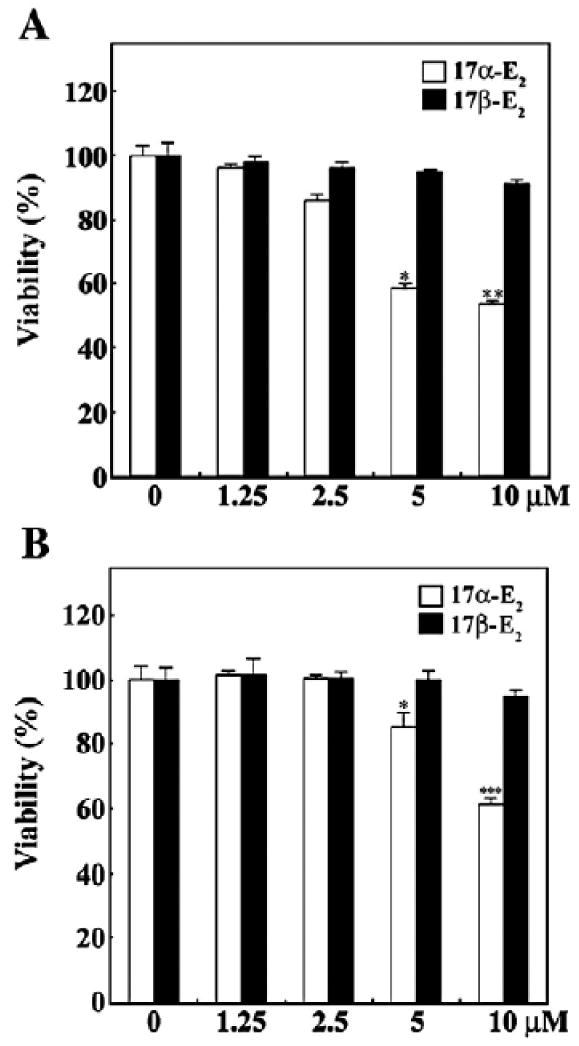

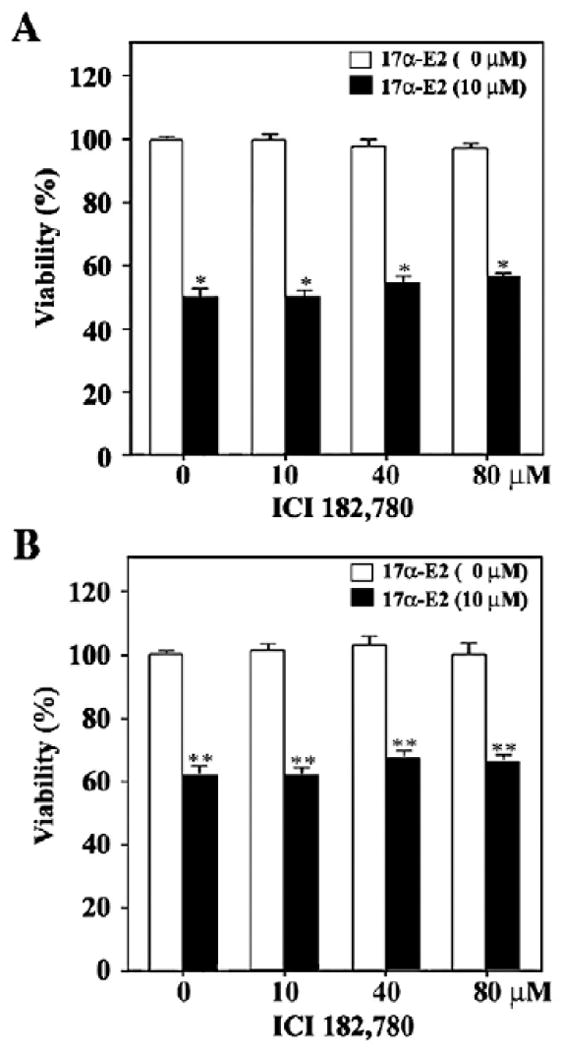

When Jurkat T cells and U937 cells were treated with either 17α-E2 or 17β-E2 at various concentrations ranging from 1.25 to 10 μM for 24 h, the viabilities of both Jurkat and U937 cells were reduced by 17α-E2 in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 1A and B). They, however, were not significantly affected by 17β-E2 in this range. Although the viability of Jurkat T cells in the presence of 1.25–2.5 μM 17α-E2 was sustained to the level of 90%, the viability in the presence of 5 and 10 μM appeared to be 58% and 53%, respectively. Under these conditions, the viability of U937 cells was not affected within the range of 1.25–2.5 μM, and declined to the level of 85% and 63% in the presence of 5 and 10 μM of 17α-E2, respectively, indicating that U937 cells appeared to be slightly more resistant to the cytotoxicity of 17α-E2 as compared to Jurkat T cells. The 17α-E2-mediated cytotoxicity toward Jurkat T cells and U937 cells was not suppressed by the ER antagonist ICI 182,780 up to 80 μM (Figs. 2A and B). These results demonstrate that 17α-E2 has cytotoxic activity toward Jurkat T cells and U937 cells at a dose of 5–10 μM, not via the classical ER pathway that can be blocked by the ER antagonist ICI 182,780.

Fig. 1.

Effect of 17α-E2 or 17β-E2 on cell viability in human acute leukemia Jurkat T cells (A) and human monoblastoid leukemia U937 cells (B). Continuously growing cells (5×104) were incubated with indicated concentrations of either 17α-E2 or 17β-E2 in a 96-well plate for 24 h and the final 4 h was incubated with MTT. The cells were sequentially processed to assess the colored formazan crystal produced from MTT as an index of cell viability. Results are displayed as means±SD of three separate experiments. *pb0.05 versus control; **pb0.01 versus control; ***pb0.005 versus control.

Fig. 2.

Effect of estrogen receptor agonist ICI182,780 on the cytotoxicity of 17α-E2 toward Jurkat T cells (A) and U937 cells (B). After pretreatment with individual concentrations of ICI 182,780 for 2 h, the treated and untreated cells were incubated with 10 μM of 17α-E2 at a density of 5×104/well in a 96-well plate. After 20 h, an MTT assay was performed to determine cell viability. Results are displayed as means±SD of three separate experiments. *pb0.0005 versus control; **pb0.0001 versus control.

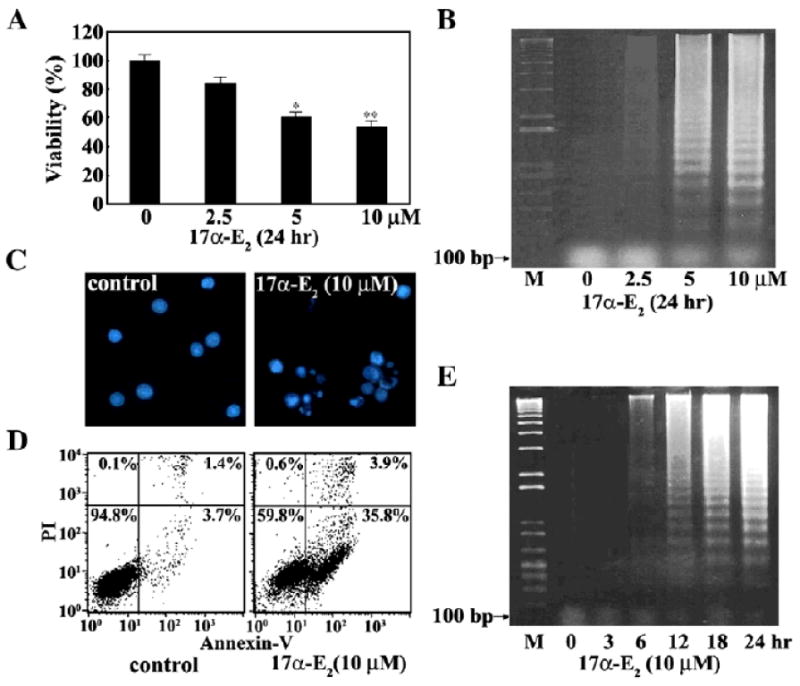

Apoptotic effect of 17α-E2 on Jurkat T cells

To understand the mechanism underlying the cytotoxicity of 17α-E2, we investigated whether 17α-E2 could induce the apoptosis of Jurkat T cells. When Jurkat T cells were treated with 17α-E2 at various concentrations ranging from 2.5 to 10 μM for 24 h, apoptotic DNA fragmentation appeared to increase in a dose-dependent manner, in accordance with the decline in cell viability (Figs. 3A and B). Typical apoptotic bodies were observed in the cells by DAPI staining (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Effect of 17α-E2 on cell viability (A), apoptotic DNA fragmentation (B), and nuclear morphology (C), and apoptotic cell death (D), and kinetic analysis of 17α-E2-induced apoptotic DNA fragmentation (E) in Jurkat T cells. Continuously growing Jurkat T cells (5×104) were incubated with indicated concentrations of 17α-E2 in a 96-well plate for 24 h and the final 4 h was incubated with MTT. Equivalent cultures were prepared and the cells were collected to analyze apoptotic DNA fragmentation by the Triton X-100 lysis method using 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis. To assess nuclear apoptotic change in Jurkat T cells exposed to 10 μM 17α-E2 for 20 h, the cells were fixed with cold ethanol and then stained with DAPI (1 μg/ml). To examine an occurrence of necrosis with 17α-E2-mediated apoptosis, the cells exposed to 10 μM 17α-E2 for 20 h were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry to detect Annexin V-FITC positive and/or PI positive cells. Unaffected, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic cells are present in the lower left, lower right, upper right, and upper left quadrants, respectively. For the time course of 17α-E2-induced apoptotic DNA fragmentation, Jurkat T cells (5×106) were incubated with 10 μM17α-E2 for the indicated times and processed to analyze apoptotic DNA fragmentation. *pb0.05 versus control; **pb0.01 versus control.

At the same time, although early apoptotic cells stained only with Annexin V-FITC and late apoptotic cells stained with both Annexin VFITC and PI increased following 17α-E2 treatment, necrotic cells stained only with PI were barely detected (Fig. 3D). The time course of induced apoptotic DNA fragmentation was also investigated following treatment with 10 μM17α-E2. As shown in Fig. 3E, a detectable level of apoptotic DNA fragmentation began to be induced at 6 h and reached a maximum level at 24 h. These results demonstrate that the cytotoxic effect of 17α-E2 on Jurkat T cells is attributable to induced apoptosis without necrosis.

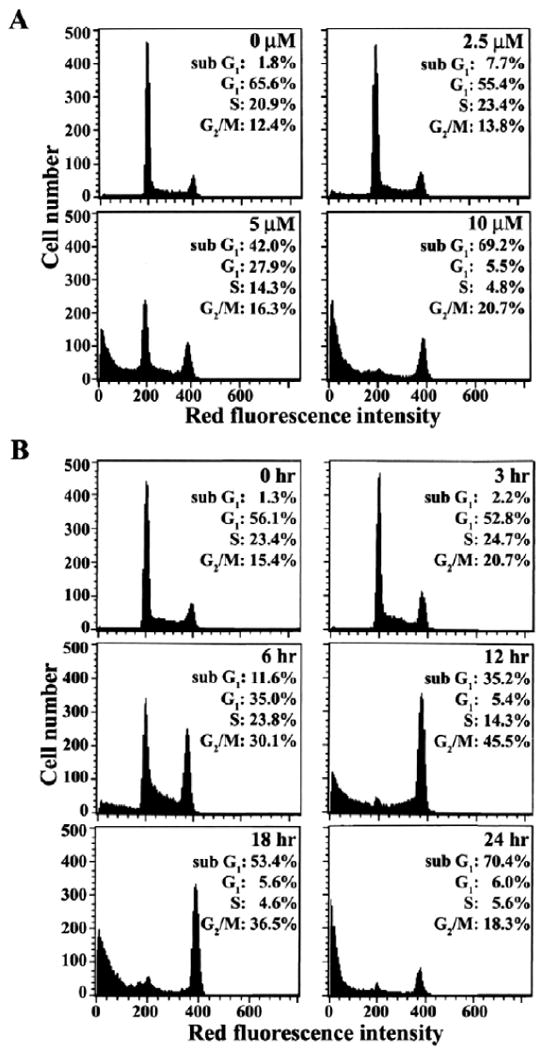

Apoptotic change in the cell cycle distribution of Jurkat T cells, following exposure to 17α-E2, was also analyzed by flow cytometry. When Jurkat T cells were treated for 24 h in the presence of 2.5, 5 or 10 μM 17α-E2, 7.7%, 42.0% or 69.2% of the cells were detected as the sub-G1 phase representing apoptotic cells, respectively (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle distribution in Jurkat T cells after treatment with various concentrations of 17α-E2 for 20 h (A) or with 10 μM17α-E2 for various time periods (B). After cells were treated with indicated concentrations of 17α-E2 for 24 h, or with 10 μM 17α-E2 for indicated time periods, the cells were harvested. The analysis of cell cycle distribution was performed on an equal number of cells (2×104) by flow cytometry after staining of DNA by propidium iodide.

Under these conditions, the level of the G1 and S phase cells was reduced with a slight increase of the G2/M phase cells, as compared to the continuously growing Jurkat T cells. These flow cytometric data confirmed that the apoptosis of Jurkat T cells was induced dose dependently by 17α -E2. When Jurkat T cells were treated with 10 μM 17α-E2 for various time periods, the apoptotic sub-G1 cells were first detected at 6 h after treatment, at the time when apoptotic DNA fragmentation began to be detectable, and then it increased in a time dependent manner (Fig. 4B). Although the level of both G1 and S phase cells declined in accordance with the enhancement of the sub-G1 cells following treatment with 17α-E2, the level of G2/M phase cells gradually increased and reached a maximum level at 12 h, before it started to decrease. These results demonstrate that the 17α-E2-induced apoptosis of Jurkat T cells accompanies the accumulation of cells in the G2/M phase, and suggest the possibility that 17α-E2 may interrupt the completion of the G2/M phase in Jurkat T cells, which could lead to the induction of apoptotic cell death.

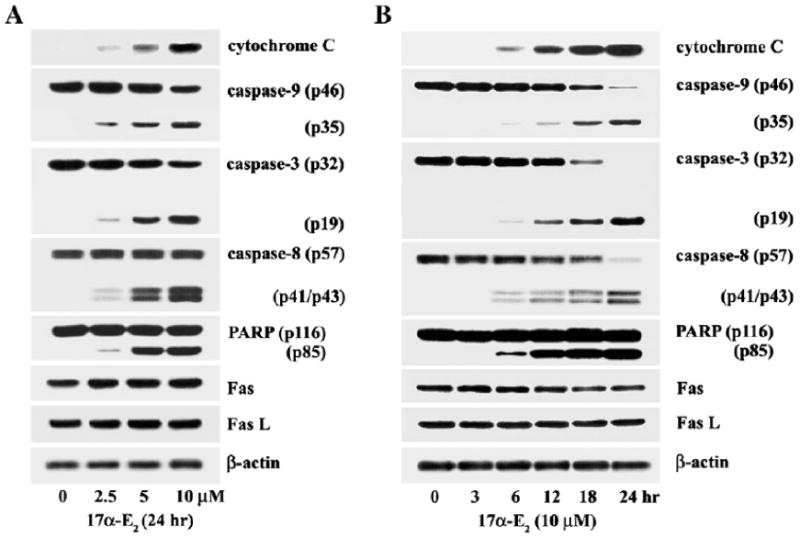

Involvement of mitochondrial cytochrome c-mediated activation of caspase cascade in 17α-E2-induced apoptotic cell death in Jurkat T cells

Since several studies have shown that a chemical-induced apoptotic signaling pathway involves the action of cytochrome c that is released from the mitochondria (Sun et al., 1999), we investigated whether 17α-E2-induced apoptosis accompanies mitochondrial cytochrome c release. As shown in Fig. 5A, although there was a barely detectable cytochrome c in the cytosolic fraction of continuously growing Jurkat T cells, the level of cytosolic cytochrome c increased dose-dependently in the presence of 17α-E2 (2.5–10 μM). Since the released mitochondrial cytochrome c, together with the apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 (Apaf-1), is known to activate caspase-9 in the presence of dATP and the latter then activates an effector caspase, caspase-3, resulting in apoptotic cell death (Li et al., 1997), we examined whether the activation of caspase-9 and -3 occurred along with the 17α-E2-mediated mitochondrial cytochrome c release. The activation of caspase-9, which proceeds through the proteolytic degradation of the inactive pro-enzyme (47 kDa) into the active form (35 kDa), was detected along with the mitochondrial cytochrome c release. The activation of caspase-3, through the proteolytic degradation of the 32 kDa pro-enzyme into the 19 kDa activated form was detected in a dose-dependent manner in the presence of 17α-E2. In addition, the activation of caspase-8 via the proteolytic degradation of the 55 kDa pro-enzyme into the 41/43 kDa activated forms was also detected. As a downstream target of active caspase-3 during the induction of apoptosis, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) has been reported to be cleaved into two fragments (Lazebnik et al., 1994). In Jurkat T cells after exposure to 17α-E2, the cleavage of PARP was detected along with the activation of caspase-3. There was, however, no alteration in the level of Fas and Fas ligand (FasL), excluding the possible involvement of the Fas/FasL system in 17α -E2-mediated death signaling pathway.

Fig. 5.

Western blot analysis of dosage effect of 17α-E2 on mitochondria-dependent caspase cascade (A), and kinetic analysis of 17α-E2-induced apoptotic events (B) in Jurkat T cells. Continuously growing Jurkat T cells (4 × 105/ml) were incubated with indicated concentrations of 17α-E2 for 24 h, or with 10 μM17α-E2 for various time periods, and were prepared for cell lysates.Western blot analysis was performed, as described in Materials and methods, in order to assess mitochondrial cytochrome c release into the cytoplasm, activation of caspase-9 and -3, PARP cleavage, and the level of Fas and FasL in Jurkat T cells treated with 17α-E2.

A kinetic analysis of these apoptotic events following the treatment of 10 μM 17α-E2 also demonstrated that the mitochondrial cytochrome c release, the activation of caspase-9, -3, and -8, and the cleavage of PARP began to be detectable at 6 h and increased by 24 h as did the apoptotic DNA fragmentation (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that 17α-E2-treatment in Jurkat T cells provokes the cytochrome c release from the mitochondria and the subsequent activation of a cytochrome c-dependent caspase cascade, leading to PARP cleavage and apoptotic DNA fragmentation. Since the caspase-8 activation is known to be an upstream event of the mitochondrial cytochrome c release in drug-induced apoptosis (Anto et al., 2002), these results also raise a possible role of the 17α-E2-mediated caspase-8 activation in the mitochondrial cytochrome c release.

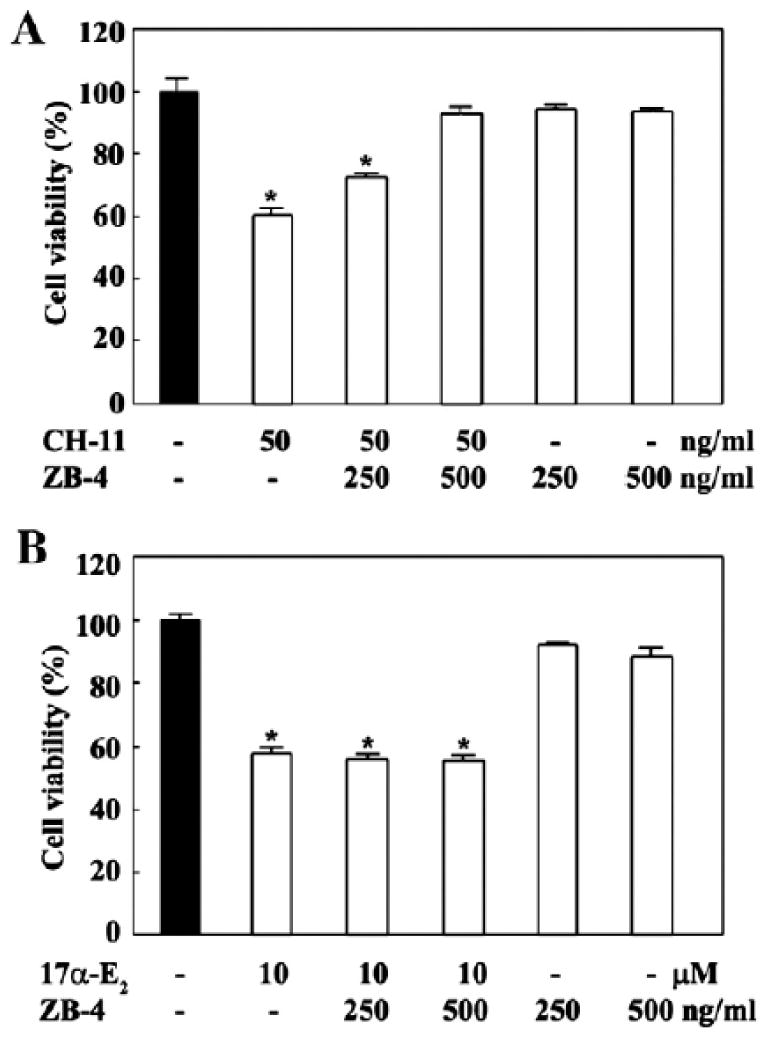

Effect of anti-Fas neutralizing antibody ZB-4 on 17α-E2-mediated apoptosis

Although there was no detectable enhancement in the expression levels of Fas and FasL in Jurkat T cells following treatment with 17α-E2, we examined whether the anti-Fas neutralizing antibody, ZB-4 could block the cytotoxicity of 17α-E2 in order to confirm the involvement of the Fas/FasL system in 17α-E2-induced apoptosis. ZB-4 has been shown to prevent the cytotoxic effect of the Fas agonistic antibody, CH-11 (Hyer et al., 2000; Liu and Fan, 2001). Pretreatment using ZB-4 (500 ng/ml), followed by the cytotoxic anti-Fas antibody CH-11 (50 ng/ml), resulted in an almost complete blockage of CH-11-induced cytotoxicity in Jurkat T cells (Fig. 6A). Under these conditions, the cytotoxic effect of 10 μM 17α-E2 was not reduced by ZB-4 (Fig. 6B). These results confirm that the 17α-E2-induced apoptosis of Jurkat T cells was not provoked by the interaction of Fas with FasL.

Fig. 6.

Effect of anti-Fas neutralizing antibody ZB-4 on anti-Fas agonistic antibody CH-11 (A) or 17α-E2-mediated cytotoxicity (B) in Jurkat T cell clone E6.1. In 96-well plates Jurkat T cells were pretreated for 1 h using 250 ng/ml and 500 ng/ml of ZB-4 in RPMI1640 containing 2% FBS, then challenged with either the anti-Fas agonistic antibody CH-11 (50 ng/ml) or 17α-E2 (7.5 μM). After 16 h, an MTT assay was performed to determine the cell viability. Each value is expressed as mean±SD (n=3). *pb0.05 as compared with the control.

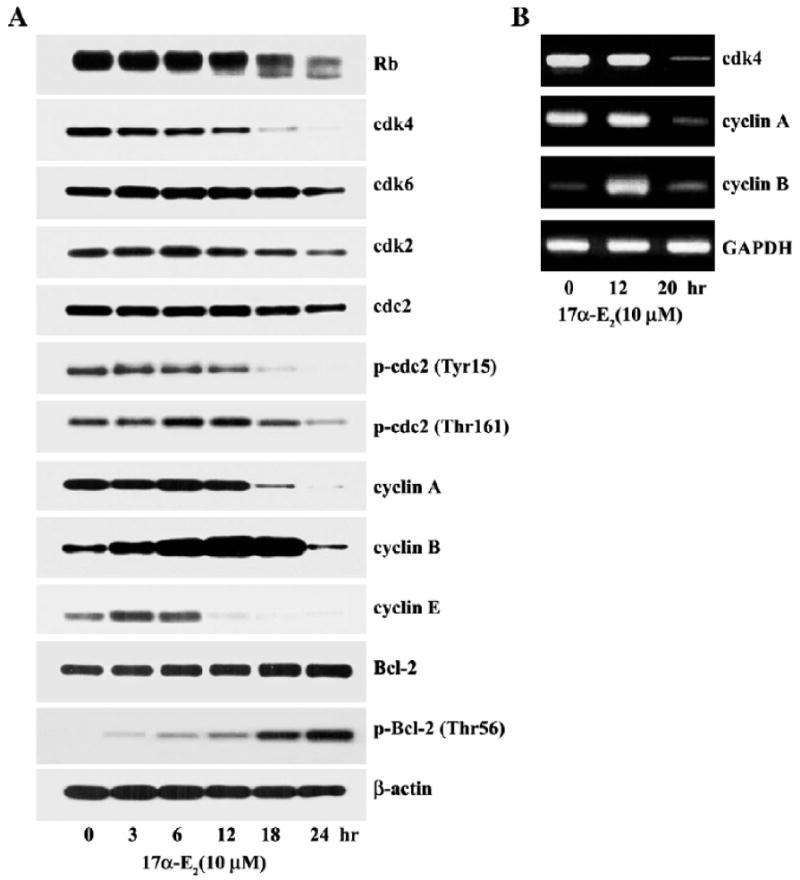

17a-E2-induced alteration in the level of cell cycle regulatory proteins

Since our data showed that 17α-E2-induced apoptosis was accompanied by a remarkable increase in the level of G2/M phase cells, it raised the possibility that Jurkat T cells might be unable to complete the G2/M phase of the cell cycle in the presence of 17α-E2. In order to understand the mechanism underlying the 17a-E2-mediated interruption responsible for the accumulation of Jurkat T cells in the G2/M phase, the effect of 10 μM 17α-E2 on the protein levels of retinoblastoma (Rb), cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks), and cyclins was investigated during the period of 24 h by Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 7A, the proteins specific for Rb, cdk4, cdk6, cdk2, cdc2, cyclin A, cyclin B1, and cyclin E were easily detectable in Jurkat T cells. Among these, the protein levels of cdk6, cdk2, and cdc2 remained relatively constant, whereas the levels of cdk4, cyclin A, and cyclin E began to significantly decrease within 12–18 h after 17α-E2 treatment. Since the roles of cdk4, cyclin A, and cyclin E are known to be confined to the G1/S transition and S phase (Adams, 2001), these results indicate that the G1/S transition and traversing S phase were not disturbed until 12 h after 17α-E2 treatment. The loss of the catalytic activity of the cdks due to the significant down-regulation of cdk4, cyclin A, and cyclin E, in the presence of 17α-E2,was further evidenced by our finding that the level of hyper-phosphorylated Rb started to decline at 12 h after 17α-E2 treatment. Under these conditions, although the level of cdc2, the catalytic subunit of M-phase promoting factor (MPF), was relatively unchanged after 17α-E2 treatment, the phosphorylation of cdc2 at tyrosine 15 residue declined to barely detectable levels at 18 h, and the phosphorylation at threonine 161residue increased 1.8-fold at 6–12 h and then returned to basal levels at 24 h. The level of cyclin B1 that comprises MPF by binding with cdc2 started to increase at 3 h and it reached a maximum level (7.6–8.8-fold upregulation) at 12–18 h. Then, the level of cyclin B1 returned to basal levels at 24 h, when most cells accumulated in the sub-G1 phase as apoptotic cells. These data indicated that the treatment of Jurkat T cells with 17α-E2 could enhance the cdc2 kinase activity that is essential to the onset of the M phase. The enhancement in the cdc2 kinase activity following 17α-E2 treatment was well reflected in an increase in the phosphorylation of Bcl-2 at threonine 56 residue while there was no alteration in the level of Bcl-2, which was previously catalyzed by the cdc2 kinase during the G2/M phase (Furukawa et al., 2000). Consistent with the change in the protein levels of cdk4, cyclin A, and cyclin B1, the levels of individual mRNAs, detected by RT-PCR, were also regulated following 17α-E2 treatment (Fig. 7B). Consequently, these results indicate that 17α-E2-mediated alteration in the phosphorylation status of cdc2 at Tyr15 and Thr161 residues, as well as the 17α-E2-mediated increase in the cyclin B1 level, leading to upregulation of the cdc2 kinase activity, may play critical roles in the accumulation of cells at the G2/M phase, prior to the induction of apoptosis following 17α-E2 treatment.

Fig. 7.

Western blot analysis (A) of the protein levels of Rb, cdk4, cdk6, cdk2, cdc2, p-cdc2 (Tyr15), p-cdc2 (Thr161), cyclin A, cyclin B1, cyclin E, p-Bcl-2 (Thr56), and β-actin and semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis (B) of mRNA specific for of cdk4, cyclin A, and cyclin B1 in Jurkat T cells. Continuously growing Jurkat T cells (4×105/ml) were incubated with 10 μM17α-E2 for indicated time periods and were prepared for cell lysates. Western blot analysis was performed as described in Materials and methods. Total RNA isolated from Jurkat T cells treated with 10 μM17α-E2 for 0 h,12 h or 20 h was used as a template for RT-PCR using gene-specific primers described in Table 1. GAPDH was used as the housekeeping control gene.

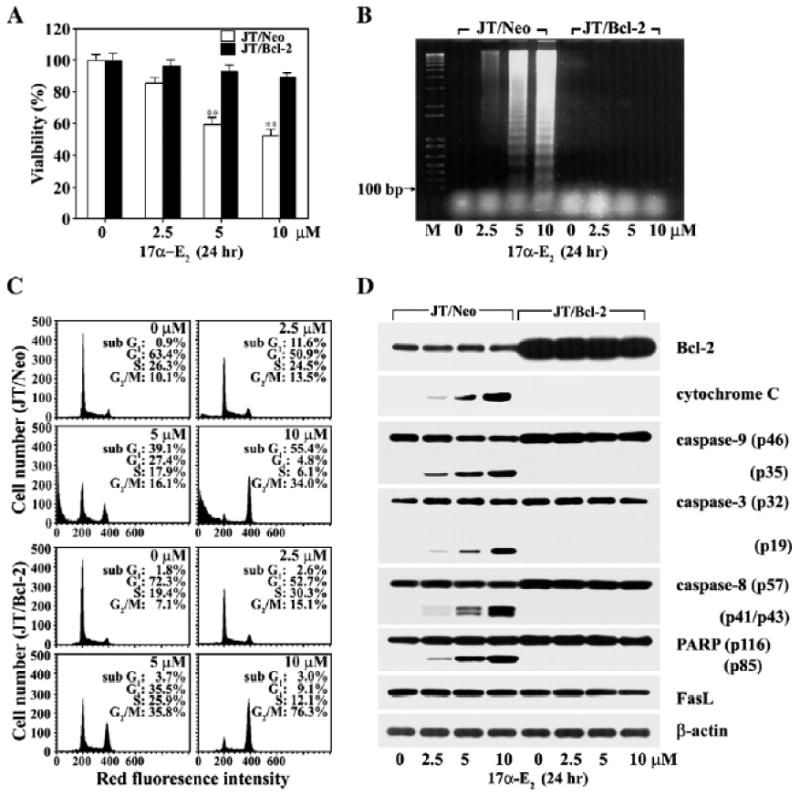

Effect of Bcl-2 on 17α-E2-induced apoptotic cell death in Jurkat T cells. Our results demonstrate that 17α-E2-mediated apoptosis accompanies mitochondrial cytochrome c release, along with the activation of caspase-9, -3, and -8. It, however, remains unclear as to whether these 17α-E2-mediated cellular biochemical events are a prerequisite for apoptotic cell death. We decided to take advantage of this antiapoptotic role of Bcl-2 in order to examine whether mitochondrial cytochrome c release and subsequent activation of the caspase cascade are essential steps for 17α-E2-induced apoptosis. In this regard, we investigated the effect of the overexpression of Bcl-2 on Fig. 4. 17α-E2-induced events including mitochondria-dependent caspase cascade and DNA fragmentation by employing Jurkat T cells transfected with the Bcl-2 gene (JT/Bcl-2) and Jurkat T cells transfected with the vector (JT/Neo). As shown in Fig. 8A, the cytotoxicity of 17α-E2 (2.5–10 μM) to Jurkat T cells was abrogated by the overexpression of Bcl-2. Similarly, 17α-E2-induced apoptotic DNA fragmentation was also prevented, indicating that the protection effect of Bcl-2 on the cytotoxicity of 17α-E2 is mainly due to its inhibition of apoptotic DNA fragmentation (Fig. 8B). Flow cytometric analysis also showed that the level of sub-G1 cells, which was significantly enhanced in JT/Neo cells after 17α-E2 treatment, failed to increase in JT/Bcl-2 cells. Upon the blocking of the 17α-E2-induced apoptosis by the overexpression of Bcl-2, the level of G2/M phase cells increased significantly as compared to the control JT/Neo cells (Fig. 8C). These results indicate that the Bcl-2 could inhibit 17α-E2-induced apoptosis but not G2/M arrest, and that the G2/M arrest occurred prior to the induction of apoptosis. The expression level of the Bcl-2 protein in JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells, which was not affected by treatment with 17α-E2,was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 8D). Under the same conditions, the mitochondrial cytochrome c release, which was inducible in the presence of 17α-E2 (2.5–10 μM), was completely blocked by the overexpressed Bcl-2. In addition, the 17α-E2-mediated activation of capase-9, -3 and -8, and degradation of PARP became undetectable. Consequently, these results indicate that the mitochondrial cytochrome c release with subsequent activation of the caspase cascade, which might mainly be induced in the G2/M-arrested cells following 17α-E2, is negatively regulated by Bcl-2, and is thus required for 17α-E2-induced apoptotic DNA fragmentation.

Fig. 8.

Inhibitory effect of Bcl-2 on cytotoxicity (A), apoptotic DNA fragmentation (B), sub-G1 peak (C), and mitochondrial cytochrome c-dependent caspase cascade (D) induced by 17α-E2. Both JT/Bcl-2 and JT/Neo cells were incubated at a density of 5×104/well with various concentrations of 17α-E2 in a 96-well plate. After incubation for 20 h, MTT was added for an additional 4 h. Equivalent cultures were prepared and the cells were processed to analyze apoptotic DNA fragmentation or to obtain cell lysates. To assess cell cycle distribution, the cells were fixed with cold ethanol and then stained with propidium iodide for flow cytometric analysis. Western blot analysis was performed in order to detect the overexpression of Bcl-2, mitochondrial cytochrome c release, caspase activation, and PARP cleavage induced by 17α-E2, as described in Materials and methods. *pb0.0005 versus control; **pb0.005 versus control.

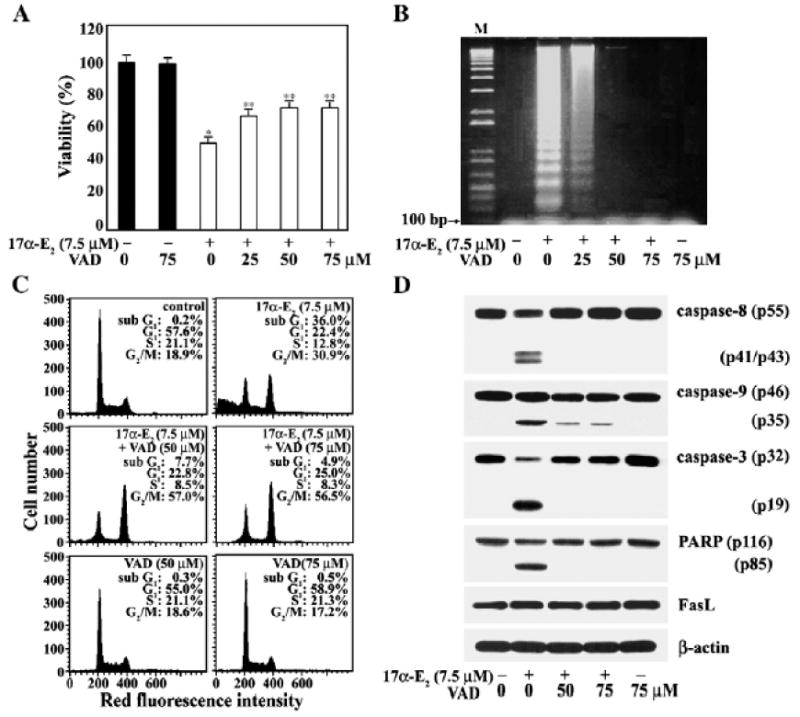

Effect of pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk on 17α-E2-induced apoptosis and G2/M arrest

To elucidate further the involvement of the G2/M arrest and caspase activation in 17α-E2-induced apoptosis in Jurkat T cells, we examined the effect of the caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk, which was known to inhibit broad-range caspases (Slee et al., 1996), toward the apoptogenic activity of 17α-E2. After Jurkat T cells were pretreated with z-VAD-fmk at concentrations of 25 μM, 50 μM, and 75 μM for 2 h, the cells were exposed to 7.5 μM 17α -E2 for 20 h. As shown in Fig. 9A, the cytotoxic effect of 17α-E2, as determined by MTT assay, was markedly reduced in the presence of z-VAD-fmk. The addition of z-VAD-fmk alone up to 75 μM, however, did not significantly affect the viability of Jurkat T cells. Under these conditions, 17α-E2-induced apoptotic DNA fragmentation was also reduced by z-VAD-fmk in a dose dependent manner, and the DNA fragmentation was completely abrogated by 75 μM z-VAD-fmk (Fig. 9B). The effect of z-VAD-fmk on 17α-E2-mediated G2/M arrest was analyzed by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 9C, continuously growing Jurkat T cells showed barely detectable sub-G1 cells, with 57.6% of the cells in the G1, 21.1% in the S, and 18.9% in the G2/M phase. This cell cycle progression pattern was essentially the same as that of Jurkat T cells cultured in the presence of 50 μM or 75 μM z-VAD-fmk alone. Following treatment with 7.5 μM 17α-E2 for 20 h, 36% of Jurkat T cells were in the apoptotic sub-G1, with 22.4% in the G1, 12.8% in the S, and 30.9% of cells in the G2/M phase, whereas Jurkat T cells treated with 7.5 μM 17α-E2 for 20 h in the presence of 50 μM or 75 μM z-VAD-fmk showed a barely detectable level of sub-G1 phase cells with 23–25% of the cells in the G1, 8.3–8.5% in the S, and 56–57% in the G2/M phase. In accordance with the inhibitory effect of z-VAD-fmk on cytotoxicity as well as apoptotic DNA fragmentation exerted by 17α-E2, the activation of caspase-9, -3 and -8, and PARP degradation were also blocked (Fig. 9D). These results demonstrate that the activation of caspase cascade, which can be blocked by z-VAD-fmk, is critical for 17α-E2-mediated apoptosis. In addition, since only the G2/M phase cells increased and reached 56–57% of the total number of cells under the conditions that the 17 α-E2-induced apoptosis was blocked by z-VAD-fmk, these results indicate that the 17 α-E2-mediated G2/M arrest in Jurkat T cells is a caspase-independent event, from which apoptotic cells are mainly derived.

Fig. 9.

Suppressive effect of a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk on cytotoxicity (A), apoptotic DNA fragmentation (B), sub-G1 peak (C), and mitochondrial cytochrome c dependent caspase cascade (D) induced by 17α-E2 in Jurkat T cells. Jurkat T cells were pretreated with a caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk at indicated concentrations for 2 h, and were then incubated at a density of 5×104/well with 7.5 μM17α-E2 in a 96-well plate. After incubation for 16 h, MTTwas added for an additional 4 h. Equivalent cultures were prepared and the cells were processed to analyze apoptotic DNA fragmentation, cell cycle distribution, and caspase activation induced by 17α-E2, as described in Materials and methods. *pb0.001 versus control; **pb0.05 versus control.

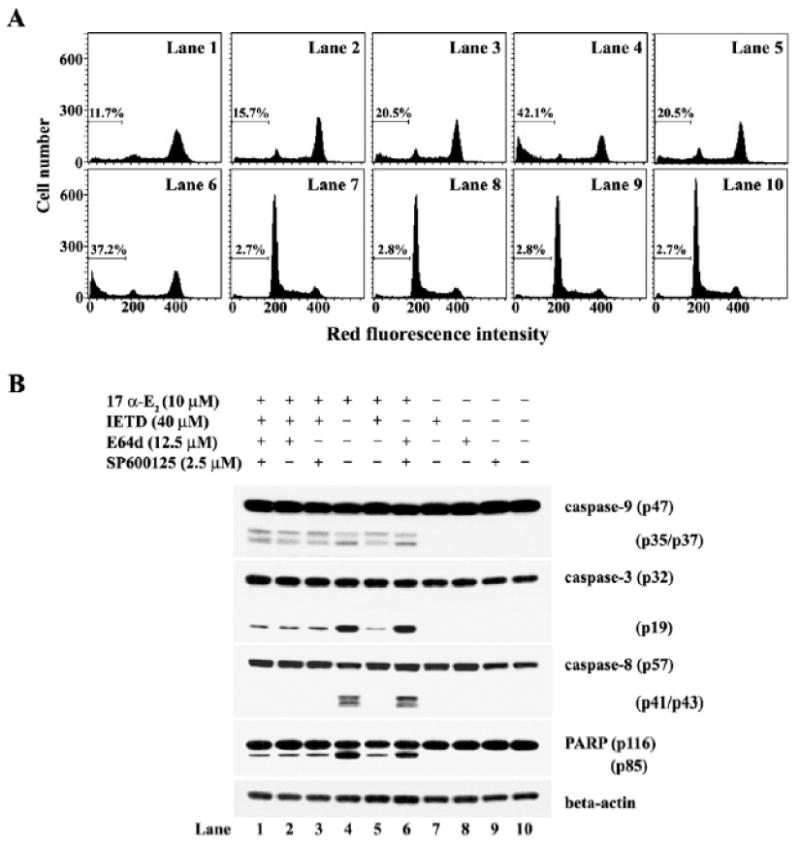

Effect of caspase-8 inhibitor (z-IETD-fmk), m-calpain inhibitor (E64d), or JNK inhibitor (SP600125) on 17α-E2-induced apoptosis

To elucidate further the17α-E2-mediated death signaling pathway, we investigated the effect of the caspase-8 inhibitor (z-IETD-fmk) (Takizawa et al., 1999), m-calpain inhibitor (E64d) (Inomata et al., 1996), or JNK inhibitor (SP600125) (Bennett et al., 2001) on 17α-E2- mediated apoptotic events in Jurkat T cells. After pretreatment with each inhibitor alone or various combinations of inhibitors for 2 h, the cells were exposed to 10 μM 17α-E2 for 15 h. Although continuously growing Jurkat T cells showed a barely detectable apoptotic sub-G1 peak, it increased to the level of 42.1% in the presence of 10 μM17α-E2 for 15 h (Fig. 10A). The 17α-E2-induced sub-G1 peak was reduced to the level of 15.7–20.5% by either pretreatment with z-IETD-fmk alone, pretreatment with z-IETD-fmk and E64d, or pretreatment with z-IETD-fmk and SP600125, whereas it declined to the level of 11.7% by the simultaneous pretreatment of z-IETD-fmk, E64d, and SP600125. The 17α-E2-induced sub-G1 peak, however, was not significantly reduced by the concomitant pretreatment with E64d and SP600125 without z-IETD-fmk. Western blot analysis revealed that the 17α-E2-mediated caspase-9 activation was detected irrespective of the individual or simultaneous presence of z-IETD-fmk, Ed64d, and SP600125 (Fig. 10B). In addition, when 17α-E2-mediated caspase-8 activation was not induced due to the presence of z-IETD-fmk, both the caspase-3 activation and PARP cleavage appeared to decline, as compared to the changes detected when caspase-8 activation was allowed in the absence of z-IETD-fmk. These results indicate that the 17α-E2-mediated activation of caspase-8, which was induced independently of the mitochondrial cytochrome c release and resultant caspase-9 activation, can contribute with caspase-9 regarding the caspase-3 activation required for PARP degradation.

Fig. 10.

Apoptotic change in the cell cycle distribution (A) andWestern blot analysis of activation of caspase-9, -3, and -8, and cleavage of PARP (B) and in Jurkat T cells after treatment with 17α-E2 (10 μM) in the presence of IETD, E64d, or SP600125 (B). Jurkat T cells (4×105/ml) were preincubated in the individual or simultaneous presence of z-IETD-fmk, E64d, or SP600125 for 2 h and then treated with 10 μM 17α-E2 for 15 h. The analysis of cell cycle distribution was performed on an equal number of cells (2×104) by flow cytometry after staining of DNA by propidium iodide. Western analysis was performed as described in Materials and methods.

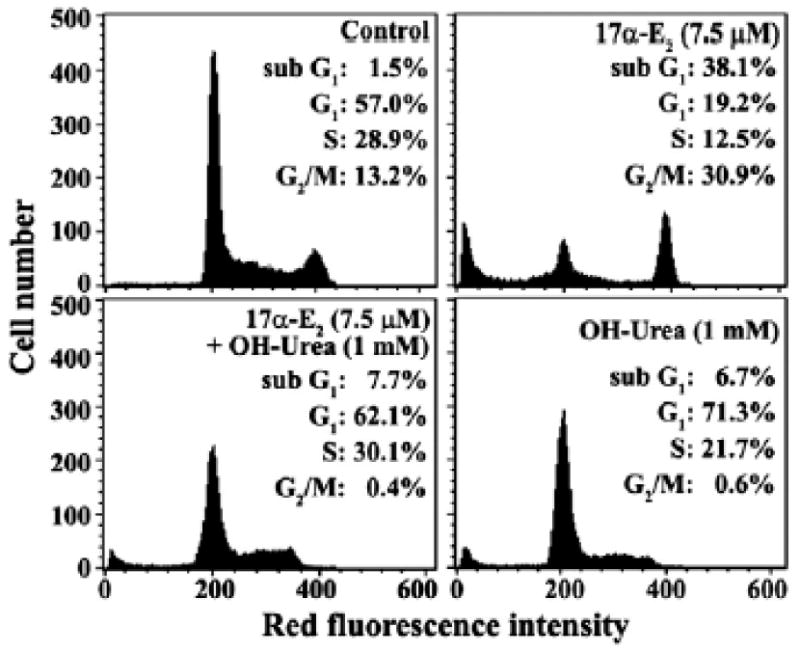

Effect of hydroxyurea on 17α-E2-mediated apoptosis

Since current data raised a possibility that 17α-E2-mediated G2/M arrest might lead to induction of apoptotic cell death, we have investigated whether the cells arrested in the G1/S phase can be protected from 17α-E2-induced apoptosis. In this context, we have employed hydroxyurea, which is known to block the cell cycle progression at the G1/S boundary (Adams and Lindsay, 1967; Kim et al., 1992). Following treatment of Jurkat T cells with 1 mM hydroxyurea for 20 h, 71.3% of the cells were in the G1, 21.7% of the cells were in the S, and only 6.7% of the cells were in the sub-G1 phase representing apoptotic cells, indicating that the majority of cells were arrested at the G1/S boundary (Fig. 11). Whereas the cells treated with 7.5 μM 17α-E2 for 20 h showed 38.1% of the cells in the sub-G1 phase, with 19.2%, 12.5%, and 30.9% of the cells in the G1, S, and G2/M phase, respectively, 17α-E2-induced G2/M arrest as well as apoptosis was almost completely abrogated in the presence of 1 mM hydroxyurea with 62.1% of the cells in the G1, and 30.1% in the S phase, and only 7.7% in the sub-G1 phase. These results confirm that the 17α-E2-induced apoptosis of Jurkat T cells is mainly induced from the G2/M-arrested cells.

Fig. 11.

Effect of hydroxyurea on 17α-E2-induced G2/M arrest and apoptosis in Jurkat T cells. After Jurkat T cells were treated with 7.5 μM 17α-E2, 7.5 μM 17α-E2 plus 1 mM hydroxyurea, or 1 mM hydroxyurea for 20 h, the cells were harvested. The analysis of cell cycle distribution was performed on an equal number of cells (2×104) by flow cytometry after staining of DNA by propidium iodide.

Discussion

In this study, we have investigated whether a pharmacological dose (2.5–10 μM) of 17α-E2, which possesses cytotoxicity against human leukemias Jurkat T and U937 cells, could disturb the cell cycle and induce apoptotic cell death. When Jurkat T and U937 cells were treated with 17α-E2, cell viabilities decreased in a time- and dose dependent manner. Conversely, 17β-E2, a stereoisomer of 17α-E2, did not show remarkable cytotoxic effect on these leukemia cells at the same dose. At concentrations higher than 20 μM, 17β-E2 could exert cytotoxic effect on these leukemia cells (data not shown), which was essentially consistent with a previous report where the IC50 values of 17β-E2 measured against Jurkat T cells and U937 cells for 72 h were 30 μM and 25 μM, respectively (Blagosklonny and Neckers, 1994).

Furthermore, the cytotoxic effect of 17α-E2 was not suppressed by the ER antagonist ICI 182,780. In addition, a possible involvement of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in the cytotoxic effect of 17α-E2 could be excluded because the cytotoxicity was not prevented in the presence of a GR antagonist RU486 (data not shown). Since it has been reported that Jurkat T cells and U937 cells do not express ERs (Danel et al., 1985), these previous and current data confirm that the cytotoxicity of 17α-E2 is not mediated via the classical ER pathway by which 17β-E2 delivers the estrogenic effect.

In agreement with the 17α-E2-mediated cytotoxicity, apoptotic DNA fragmentation and sub-G1 peak increased in Jurkat T cells after 17α -E2 treatment, demonstrating that the cytotoxicity was attributable to induced apoptosis. No involvement of necrosis in the cytotoxicity of 17α-E2 was evidenced by a flow cytometric analysis of the cells stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI.

Previously, it was reported that chemical agent-induced apoptotic signaling pathway, converging to the activation of caspase cascade, could be triggered either by cytochrome c released from mitochondria (Li et al., 1997) or by the death receptor-mediated signal (Muzio et al., 1998). In Jurkat T cells exposed to 17α-E2, mitochondrial cytochrome c release and activation of caspase-9, -3, and -8 were detected, whereas there was no detectable increase in the levels of Fas and FasL. The cytotoxic effect of 17a-E2 was not reduced by the anti-Fas neutralizing antibody ZB-4. This indicated that the 17α-E2-induced apoptosis was triggered by the mitochondria-dependent caspase activation pathway rather than by the Fas/FasL-mediated death signaling pathway. However, a possibility that 17α-E2 activated an extrinsic apoptotic pathway by causing Fas oligomerization, which was previously not blocked by the antibody ZB-4 (Huang et al., 1999), still remains to be elucidated. Under these conditions, there was a remarkable enhancement of G2/M cells prior to the induction of sub-G1 cells, suggesting that the 17α-E2-mediated accumulation of G2/M cells might be an upstream event that leads to apoptosis in Jurkat T cells. In relation to the disturbance of the cell cycle, although the protein levels of cdk6, cdk2, and cdc2 were relatively unchanged, those of cdk4, cyclin A, and cyclin E, which play critical roles in the G1/S transition and S phase (Adams, 2001), were significantly down-regulated after 17α-E2 treatment. A significant upregulation of cyclin B1, as well as a decrease in the Tyr15 phosphorylation and an increase in the Thr161 phosphorylation of cdc2, both of which were previously a prerequisite for the activation of cdc2 kinase at the G2/M phase (Fesquet et al., 1993; Watanabe et al., 1995), were detected along with the increase of G2/M cells. Therewas, however, no detectable increase in the level of negative cell cycle regulatory proteins such as p53, p16INK4a, p21Cip1, and p27Kip1 (data not shown). A semi-quantitative RT-PCR assay revealed that the 17α-E2-mediated down-regulation of cdk4 and cyclin A, and upregulation of cyclin B1 were induced at the mRNA level. Since the cyclin B/cdc2 kinase, which plays a critical role as MPF in the G2/M transition, should be inactivated through the degradation of cyclin B1 by anaphase promoting complex (APC) in order to exit from the M phase (Holloway et al., 1993), these results indicated that the upregulation of cyclin B1 and the alteration in the phosphorylation status of cdc2 could render the cdc2/cyclin B1 kinase active and thus, prevent the cells from completing the M phase after being treated with 17α-E2. The upregulation of cdc2 kinase activity following 17α-E2 treatment was evidenced by the enhancement of Thr56 phosphorylation of Bcl-2. This is because Bcl-2 could be phosphorylated at threonine 56 residue by cdc2 kinase at the G2/M phase (Furukawa et al., 2000). These results also suggest that the 17α-E2-mediated down-regulation of the protein levels of cdk4, cyclin A, and cyclin E, which led to a decrease in the level of hyperphosphorylated Rb, might result from the accumulation of cells at the M phase.

To confirm that the mitochondrial cytochrome c release and subsequent activation of caspase cascade were critical for the 17α-E2-mediated apoptosis, we have employed two experimental approaches; one was to take advantage of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 which can suppress mitochondrial cytochrome c release (Yang et al., 1997) as well as endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated activation of caspase-8 (Jimbo et al., 2003; Jun et al., 2007), and the other was to use caspase inhibitors, such as z-VAD-fmk, the broad range caspase inhibitor (Slee et al., 1996), and z-IETD-fmk, the caspase-8 inhibitor (Takizawa et al., 1999). 17α-E2-mediated apoptosis was completely abrogated by the overexpression of Bcl-2, whereas the accumulation of G2/M cells was significantly enhanced. Along with the G2/M arrest, a significant increase in the number of metaphase cells and/or early anaphase cells was observed, by DAPI staining, in Jurkat T cells overexpressing Bcl-2 after treatment with 17α-E2 (data not shown). These results demonstrated that the mitochondrial cytochrome c-dependent activation of caspase cascade and subsequent PARP cleavage, which was negatively regulated by Bcl-2, were critical steps in executing 17α-E2-induced apoptosis, and that the apoptosis was mainly induced in the cells that accumulated at the G2/M phase. Requirement of the mitochondria-dependent activation of caspase cascade for 17α-E2-mediated apoptosis was further investigated using z-VAD-fmk, by which 17α-E2-mediated cytotoxicity, apoptotic DNA fragmentation, and death signaling events including the activation of caspase-9, -3, and -8, and PARP cleavage were significantly reduced or blocked. Again, there was a remarkable enhancement in the level of G2/M cells, upon the blocking of 17α-E2-mediated apoptosis by z-VAD-fmk, confirming that the apoptosis was mainly induced in the G2/M cells via the caspase activation. Although the endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated activation of caspase-8 was previously upstream of mitochondrial cytochrome c release in the chemical agent-induced apoptosis of tumor cells (Jimbo et al., 2003; Jun et al., 2007), it was not the case for the 17a-E2-mediated activation of caspase-8. This is because the caspase-9 activation was induced by 17α-E2, regardless of the individual or simultaneous presence of caspase-8 inhibitor (z-IETD-fmk), m-calpain inhibitor (E64d), and JNK inhibitor (SP600125), and both the caspase-3 activation and PARP cleavage were reduced, but not completely, by the presence of z-IETDfmk. The endoplasmic reticulum stress was known to activate three pro-apoptotic regulators such as caspase-8, caspase-12, and JNK, and the caspase-12 activation could be mediated by m-calpain activation (Rao et al., 2001; Aoki et al., 2002). These previous and current results indicated that the 17α-E2-mediated activation of caspase-8, which was induced independently of the endoplasmic reticulum stress, was not upstream of the mitochondrial cytochrome c release, but it could contribute to the activation of effector caspase-3.

Since 17α-E2-induced apoptosis appeared to occur subsequent to accumulation of cells in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle, it was likely that forced arrest at the G1/S boundary might protect Jurkat T cells from 17α-E2-induced apoptosis. To examine this prediction, we have decided to employ hydroxyurea, a cell cycle blocking agent at the G1/S boundary prior to entering S phase. The mode of action of hydroxyurea is to inhibit ribonucleotide reductase, which converts ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides required for DNA synthesis, and thus hydroxyurea can inhibit entering S phase in a variety of cells (Adams and Lindsay, 1967; Kim et al., 1992; Koc et al., 2004). The presence of 1 mM hydroxyurea significantly reduced both 17α-E2-induced G2/M arrest and apoptotic cell death. This indicated that the cells arrested at the G1/S boundary by hydroxyurea were refractory to the apoptotic activity of 17α-E2, confirming that the G2/M arrest was the upstream and causal event of 17α-E2-induced apoptosis.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that the cytotoxicity of 17α-E2 toward Jurkat T cells is attributable to the G2/M arrest of the cell cycle and subsequent induction of apoptosis via mitochondria dependent activation of caspase-9 and -independent activation of caspase-8, both of which converge to caspase-3 activation. These findings demonstrate the apoptogenic activity of 17α -E2 against Jurkat T cells, which is exerted by the ER-independent mechanism at the pharmacological doses, and may expand our understanding of the benefits of the clinical application of 17α-E2 with regard to estrogen replacement therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Korean Research Foundation (KRF-2003-J00103) and a grant from the Korean Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (HTDP 202060-03), and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, USA.

References

- Adams PD. Regulation of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein by cyclin/cdks. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1471:M123–M133. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(01)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RL, Lindsay JG. Hydroxyurea: reversal of inhibition and use as a cellsynchronizing agent. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:1314–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizu-Yokota E, Ichinoseki K, Sato Y. Microtubule disruption induced by estradiol in estrogen receptor-positive and -negative human breast cancer cell lines. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:1875–1879. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.9.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso de Lecinana M, Egido JA. Estrogens as neuroprotectants against ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;21(Suppl 2):48–53. doi: 10.1159/000091703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anto Rj, Mukhopadhyay A, Denning K, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) induces apoptosis through activation of caspase-8, BID cleavage and cytochrome c release: its suppression by ectopic expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:143–150. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki H, Kang PM, Hampe J, Yoshimura K, Noma T, Matsuzaki M, Izumo S. Direct activation of mitochondrial apoptosis machinery by c-Jun N-terminal kinase in adult cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10244–10250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112355200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behl C, Holsboer F. The female sex hormone oestrogen as a neuroprotectant. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:441–444. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01392-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behl C, Skutella T, Lezoualc'h F, Post A, Widmann M, Newton CJ, Holsboer F. Neuroprotection against oxidative stress by estrogens: structure–activity relationship. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:535–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behl C, Widmann M, Trapp T, Holsboer F. 17-Beta estradiol protects neurons from oxidative stress-induced cell death in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;216:473–482. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, O'Leary EC, Sakata ST, Xu W, Leisten JC, Motiwala A, Pierce S, Satoh Y, Bhagwat SS, Manning AM, Anderson DW. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13681–13686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonny MV, Neckers LM. Cytostatic and cytotoxic activity of sex steroids against human leukemia cell lines. Cancer Lett. 1994;76:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(94)90381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culmsee C, Vedder H, Ravati A, Junker V, Otto D, Ahlemeyer B, Krieg JC, Krieglstein J. Neuroprotection by estrogens in a mouse model of focal cerebral ischemia and in cultured neurons: evidence for a receptor-independent antioxidative mechanism. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:1263–1269. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199911000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danel L, Menouni M, Cohen JH, Magaud JP, Lenoir G, Revillard JP, Saez S. Distribution of androgen and estrogen receptors among lymphoid and haemopoietic cell lines. Leuk Res. 1985;9:1373–1378. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(85)90125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens JA, Moos WH, Howell N, Dykens JA, Moos WH, Howell N. Development of 17alpha-estradiol as a neuroprotective therapeutic agent: rationale and results from a phase I clinical study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1052:116–135. doi: 10.1196/annals.1347.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RM. The steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1988;240:889–895. doi: 10.1126/science.3283939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando RI, Wimalasena J. Estradiol abrogates apoptosis in breast cancer cells through inactivation of BAD: Ras-dependent nongenomic pathways requiring signaling through ERK and Akt. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3266–3284. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fesquet D, Labbe JC, Derancourt J, Capony JP, Galas S, Girard F, Lorca T, Shuttleworth J, Doree M, Cavadore JC. The MO15 gene encodes the catalytic subunit of a protein kinase that activates cdc2 and other cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) through phosphorylation of Thr161 and its homologues. EMBO J. 1993;12:3111–3121. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa Y, Iwase S, Kikuchi J, Terui Y, Nakamura M, Yamada H, Kano Y, Matsuda M. Phosphorylation of Bcl-2 protein by CDC2 kinase during G2/M phases and its role in cell cycle regulation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21661–21667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M906893199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway SL, Glotzer M, King RW, Murray AW. Anaphase is initiated by proteolysis rather than by the inactivation of maturation-promoting factor. Cell. 1993;73:1393–1402. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90364-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang DCS, Hahne M, Schroeter M, Frei K, Fontana A, Villunger A, Newton K. Activation of Fas by FasL induces apoptosis by a mechanism that cannot be blocked by Bcl-2 or Bcl-x(L) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14871–14876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyer ML, Voelkel-Johnson C, Rubinchik S, Dong J, Norris JS. Intracellular Fas ligand expression causes Fas-mediated apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells resistant to monoclonal antibody-induced apoptosis. Mol Ther. 2000;2:348–358. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inomata M, Hayashi M, Ohno-Iwashita Y, Tsubuki S, Saido TC, Kawashima S. Involvement of calpain in integrin-mediated signal transduction. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;328:129–134. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JK, Suwannaroj S, Elbourne KB, Ndebele K, McMurray RW. 17-Betaestradiol alters Jurkat lymphocyte cell cycling and induces apoptosis through suppression of Bcl-2 and cyclin A. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:1897–1911. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimbo A, Fujita E, Kouroku Y, Ohnishi J, Inohara N, Kuida K, Sakamaki K, Yonehara S, Momoi T. ER stress induces caspase-8 activation, stimulating cytochrome c release and caspase-9 activation. Exp Cell Res. 2003;283:156–166. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun DY, Rue SW, Han KH, Taub D, Lee YS, Bae YS, Kim YH. Mechanism underlying cytotoxicity of lysine analog, thialysine, toward human acute leukemia Jurkat T cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:2291–2300. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun DY, Kim JS, Park HS, Han CR, Fang Z, Woo MH, Rhee IK, Kim YH. Apoptogenic activity of auraptene of Zanthoxylum schinifolium toward human acute leukemia Jurkat T cells is associated with ER stress-mediated caspase-8 activation that stimulates mitochondria-dependent or -independent caspase cascade. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1303–1313. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameda T, Mano H, Yuasa T, Mori Y, Miyazawa K, Shiokawa M, Nakamaru Y, Hiroi E, Hiura K, Kameda A, Yang NN, Hakeda Y, Kumegawa M. Estrogen inhibits bone resorption by directly inducing apoptosis of the boneresorbing osteoclasts. J Exp Med. 1997;186:489–495. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.4.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH, Proust JJ, Buchholz MJ, Chrest FJ, Nordin AA. Expression of the murine homologue of the cell cycle control protein p34cdc2 in T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1992;149:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koc A, Wheeler LJ, Mathews CK, Merrill GF. Hydroxyurea arrestsDNAreplication by a mechanism that preserves basal dNTP pools. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:223–230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303952200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazebnik YA, Kaufmann SH, Desnoyers S, Poirer GG, Earnshaw WC. Cleavage of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase by a proteinase with properties like ICE. Nature. 1994;371:346–347. doi: 10.1038/371346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Nijhawan D, Budihardjo I, Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Alnemri ES, Wang X. Cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of Apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell. 1997;91:479–489. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Fan Z. The monoclonal antibody 225 activates caspase-8 and induces apoptosis through a tumor necrosis factor receptor family-independent pathway. Oncogene. 2001;20:3726–3734. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzio M, Stockwell BR, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS, Dixit VM. An induced proximity model for caspase-8 activation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2926–2930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okasha SA, Ryu S, Do Y, McKallip RJ, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS. Evidence for estradiol-induced apoptosis and dysregulated T cell maturation in the thymus. Toxicology. 2001;163:49–62. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00374-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paganini-Hill A, Henderson VW. Estrogen deficiency and risk of Alzheimer's disease in women. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:256–261. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao RV, Hermel E, Castro-Obregon S, del Rio G, Ellerby LM, Ellerby HM, Bredesen DE. Coupling endoplasmic reticulum stress to the cell death program; mechanism of caspase activation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33869–33874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razandi M, Pedram A, Levin ER. Plasma membrane estrogen receptors signal to antiapoptosis in breast cancer. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1434–1447. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.9.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slee EA, Zhu H, Chow SC, MacFarlane M, Nicholson DW, Cohen GM. Benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp (OMe) fluoromethylketone (z-VAD-fmk) inhibits apoptosis by blocking the processing CPP32. Biochem J. 1996;315:21–24. doi: 10.1042/bj3150021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XM, MacFarlane M, Zhuang J, Wolf BB, Green DR, Cohen GM. Distinct caspase cascades are initiated in receptor-mediated and chemical-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5053–5060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.5053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa T, Tatematsu C, Ohashi K, Nakanishi Y. Recruitment of apoptotic cysteine proteases (caspases) in influenza virus-induced cell death. Microbiol Immunol. 1999;43:245–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1999.tb02400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeling AE, Dukes M, Bowler J. A potent specific pure antiestrogen with clinical potential. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3867–3873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Broome M, Hunter T. Regulation of the human WEE1Hu CDK tyrosine 15-kinase during the cell cycle. EMBO J. 1995;14:1878–1891. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07180.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise PM. Estrogens: protective or risk factors in brain function? Prog Neurobiology. 2003;69:181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise PM, Dubal DB, Wilson ME, Rau SW, Bottner M. Minireview: neuroprotective effects of estrogen—new insights into mechanisms of action. Endocrinology. 2001a;142:969–973. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.3.8033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise PM, Dubal DB, Wilson ME, Rau SW, Bottner M, Rosewell KL. Estradiol is a protective factor in the adult and aging brain: understanding of mechanism derived from in vivo and in vitro studies. Brain Res Rev. 2001b;37:313–319. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Liu X, Bhalla K, Kim CN, Ibrado AM, Cai J, Peng TI, Jones DP, Wang X. Prevention of apoptosis by Bcl-2: release of cytochrome c from mitochondria blocked. Science. 1997;275:1129–113. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]