Abstract

Context: Pseudotumor cerebri has only been described after successful surgery for Cushing’s disease (CD) in case reports. We sought to establish the incidence and timing of its occurrence, identify predisposing factors, characterize the clinical presentations and their severity, and examine the effects of treatment in patients who underwent surgery for CD.

Setting: This study was conducted at two tertiary care centers: The University of Virginia and the National Institutes of Health.

Patients: We conducted a retrospective review of 941 surgeries for CD (723 adults, 218 children) to identify patients who developed pseudotumor cerebri after surgery for CD and examine the associated clinical features.

Results: Seven children (four males, three females; 3%), but no adults, developed pseudotumor cerebri postoperatively. All underwent resection of an ACTH-secreting adenoma, and postoperative serum cortisol reached a nadir of less than 2 μg/dl. After surgery, all were placed on tapering hydrocortisone replacement therapy. Within 3–52 wk, all seven patients experienced symptoms of pseudotumor cerebri and had ophthalmological examination demonstrating papilledema. One patient had diplopia from a unilateral VIth nerve palsy. Six patients were still on steroid replacement at onset of symptoms. In three patients, a lumbar puncture demonstrated elevated opening pressure. Four patients were treated successfully with a lumbar puncture, steroids, and/or Diamox. Three patients did not receive treatment, and their symptoms resolved over several months. There was no correlation between the degree of hypercortisolism (24-h urinary free cortisol) before surgery and the likelihood of developing pseudotumor cerebri after surgery (P < 0.23).

Conclusions: This series demonstrates a 3% occurrence of pseudotumor cerebri in children after successful surgery for CD, but the absence of the syndrome in adults. Pseudotumor cerebri manifests itself within 1 yr of surgery, often while patients are still undergoing replacement steroid therapy. A patient exhibiting signs of intracranial hypertension after surgery for CD should undergo an evaluation for pseudotumor cerebri. Recognition of the symptoms and treatment should correct and/or prevent ophthalmological sequelae.

Pseudotumor cerebri may occur after surgical remission of Cushing’s disease in children; prompt recognition of the symptoms and treatment should correct and/or prevent ophthalmologic sequelae.

After successful surgery for Cushing’s disease, most patients have profound hypocortisolism because the normal pituitary corticotrophs are suppressed after prolonged exposure to excess concentrations of serum cortisol. Thus, after surgery the patient is assessed closely for symptoms of adrenocortical insufficiency including malaise, lassitude, fatigability, weakness, weight loss, anorexia, nausea, postural dizziness, myalgias, and arthralgias (1). After postoperative serum cortisol levels reach a nadir, the patient is placed on a 2- to 4-wk slowly tapering dose of a glucocorticoid, usually cortisol, to reach a stable daily dose for physiological replacement until their hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis recovers.

Pseudotumor cerebri is manifested by headaches, visual abnormalities, tinnitus, and VIth nerve palsies (2). It has been described after discontinuing or lowering the dose of glucocorticoid therapy (3). It has also been described in isolated case reports (4,5,6,7) after successful surgery for Cushing’s disease. We sought to establish the incidence and timing of its occurrence, identify predisposing factors, characterize the clinical presentation and severity, and examine the treatment effects in a large series of patients who received surgery for Cushing’s disease. We describe seven of 218 children (3%), but none of 723 adults, who developed pseudotumor cerebri after surgery for removal of an ACTH-secreting adenoma.

Patients and Methods

We describe the clinical, laboratory, and ophthalmological findings in a series of pediatric patients who developed pseudotumor cerebri during the first year after resection of an ACTH-secreting adenoma causing Cushing’s disease. All patients were identified retrospectively as part of a single surgeon’s (E.H.O.) experience between 1982 and 2008.

Illustrative case report

A 13-yr-old female presented to medical attention with a 6-yr history of weight gain resulting in obesity (body mass index = 39 kg/m2), precocious puberty with amenorrhea, cessation of vertical growth, multiple kidney stones, hypertension, and severe stigmata of Cushing’s syndrome. The 24-h urinary excretion of cortisol was elevated at 544 μg/24 h (normal, <50 μg/24 h). Plasma ACTH was elevated at 80 pg/ml (normal, 9–52). Inferior petrosal sinus sampling results were consistent with a diagnosis of Cushing’s disease. A magnetic resonance image with gadolinium revealed a heterogeneously enhancing 10- to 12-mm adenoma in the anterior lobe of the pituitary. She underwent surgical resection of a 12-mm macroadenoma lying just beneath the pituitary capsule. After surgery, her serum cortisol levels declined to less than 1 μg/dl within 12 h. She was placed on a tapering dose of hydrocortisone, 40 mg every morning and 20 mg nightly, and then 20 mg every morning and 10 mg nightly at discharge. At discharge, she no longer required antihypertensives or metformin.

Eight weeks after surgery, the patient’s cortisol replacement was weaned to 15 mg every morning and 5 mg nightly. She was also started on thyroid replacement at that time. After an interval of headache, nausea, and vomiting, thyroid replacement was discontinued and hydrocortisone was increased to 10 mg every morning and at noon, and 5 mg nightly. Over the next 2 wk, her family began to notice “wandering” of her left eye, progressing to an inability to move her left eye laterally and then to blurred vision. A neuro-ophthalmologist diagnosed an abducens nerve palsy in the left eye and papilledema bilaterally associated with flame hemorrhages. A lumbar puncture was performed with an opening pressure of 21 cm H2O, confirming a diagnosis of pseudotumor cerebri. Her symptoms resolved after the lumbar puncture. She was discharged home on 30 mg hydrocortisone daily with a slow taper. Eight weeks after discharge she began to experience pulsatile tinnitus, and she had papilledema on ophthalmological examination. Two further lumbar punctures were performed over the ensuing weeks, and all demonstrated elevated intracranial pressure (opening pressure as high as 45 mm H2O). She was again placed on supraphysiological doses of hydrocortisone. Her papilledema persisted, and after a final lumbar puncture with an opening pressure of 49 cm H2O, she underwent a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, which induced remission of her papilledema and other symptoms.

Results

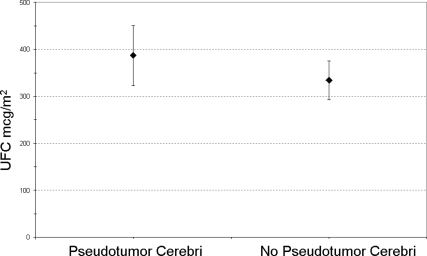

Between 1982 and 2008, one of us (E.H.O.) performed 941 surgeries for Cushing’s disease (879 at the National Institutes of Health, 62 at the University of Virginia), including 218 operations for children (age 21 yr or less) with Cushing’s disease (198 at the National Institutes of Health, 20 at the University of Virginia). Seven children (four males, three females; 3%) who developed pseudotumor cerebri after successful surgery as a delayed complication from glucocorticoid withdrawal are the basis of this report. Average age at the time of surgery was 12 yr. Three patients were morbidly obese, whereas four were within a normal body mass index. Three patients had macroadenomas, and four had microadenomas. The preoperative 24-h cortisol measurement (24-h urinary free cortisol) of the seven patients who developed pseudotumor cerebri was not significantly different than the 211 pediatric patients who did not develop a similar syndrome (P < 0.23) (Fig. 1). The case presentations and treatment courses are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Average urinary free cortisol (UFC) and se (μg/dl, adjusted by body surface area) in pediatric Cushing’s disease.

Table 1.

Clinical features

| Patient no. | Age (yr) | Sex | Weight (kg) | Adenoma type | Symptoms of pseudotumor cerebri | Time from surgery to diagnosis of pseudotumor cerebri | On/off HCT | Treatment of pseudotumor cerebri |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | M | 134 | Macroadenoma | Hypertension | 6 wk | On | Diamox, HD HCT |

| 2 | 15 | M | 168 | Macroadenoma | Headache | 1 yr | Off | LP |

| 3 | 8 | M | 49 | Microadenoma | Vision | 10 months | On | None |

| 4 | 11 | M | 61 | Microadenoma | Headache, vision | 7 months | On | None |

| 5 | 12 | F | 91 | Macroadenoma | Headache, N/V, vision | 3 months | On | LP, HD HCT |

| 6 | 9 | F | 50 | Microadenoma | Headache | 6 wk | On | LP |

| 7 | 18 | F | 70 | Microadenoma | Hypertension | 3 wk | On | None |

M, Male; F, female; HCT, hydrocortisone; HD, high-dose; LP, lumbar puncture; N/V, nausea and vomiting.

After surgery, serum cortisol levels reached a nadir of less than 2 μg/dl in all seven patients. They were then placed on a slowly tapering dose of hydrocortisone replacement to reach a stable dose for physiological replacement of cortisol within 2–4 wk. Within 3–52 wk (median time, 9 wk), all seven patients experienced symptoms of pseudotumor cerebri, including headaches (70%), nausea/vomiting (30%), and/or visual changes (40%). Two patients had clinically significant systemic hypertension. All underwent ophthalmological examination demonstrating papilledema. Although papilledema is not specific for the diagnosis of pseudotumor cerebri, neuroimaging excluded other causes of optic nerve edema. None of the patients had mass lesions or ventriculomegaly on computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scans. One patient had a symptomatic, unilateral VIth nerve palsy. Three patients underwent a lumbar puncture demonstrating elevated opening pressures. Six of the seven patients were still on steroid replacement at the onset of pseudotumor symptoms.

Two patients were treated by increasing their steroid dose (concomitantly with Diamox in one), which resulted in resolution of symptoms. Three patients underwent lumbar puncture demonstrating elevated opening pressures; in two patients, this was therapeutic and no additional treatment was sought. In one patient, abducens paralysis disappeared after lumbar puncture but papilledema persisted. In three patients, the symptoms resolved over several months without treatment. One patient (patient 5) relapsed three times; her course is depicted in the illustrative case report above.

None of the 723 adults in the series are known to have developed a similar syndrome.

Discussion

Despite having described the condition that is now known as Cushing’s disease, and despite being a pioneer of pituitary surgery, Cushing never operated on the pituitary gland in a patient with Cushing’s disease. However, he did perform a subtemporal decompression on Minnie G. for “polyglandular syndrome,” which we now know is the result of chronic exposure to excess cortisol. His description of her (8) follows:

After her menses stopped at 16 yr old, “her vision began to fail” and she had “episodes of diplopia. Nausea and vomiting has occurred with the more severe headaches.” “The optic nerves are congested, and show a low grade of choked disc with no optic pallor. Acuity: left and right 10/40.” He saw her again 6 months later, on July 28, 1911, and noted that “the visual fields are even more constricted, and the vision was lowered to 15/70 left and 15/100 right.” He performed a right subtemporal decompression and found a “tense and wet brain.” Her “recovery was uncomplicated and an unexpected degree of relief was afforded by the decompression. A month later: no further headaches; subsidence of neuroretinal edema; blood pressure low (130–140); … a loss of 12 pounds of weight.” Her blood pressure had previously been elevated. Cushing summarized, “The case is an instance of the combination of intracranial pressure symptoms with amenorrhea, adiposity, and low physical stature ….”

Pseudotumor cerebri, or idiopathic intracranial hypertension, is a rare disorder that is diagnosed by the presence of headache, papilledema, and elevated cerebrospinal fluid pressure (>200 mm water) in the absence of abnormalities in level of consciousness, findings on neurological examination (except for cranial nerve paresis), neuroimaging, or cerebrospinal fluid analysis (9). In the adult population, pseudotumor cerebri occurs with a prevalence of one case per 100,000 women of normal weight, increasing to 19 cases per 100,000 women who are obese (10). In the pediatric prepubescent population, it occurs in approximately one case per 100,000 individuals and is unrelated to weight (11,12). It occurred in 3% of our children who were recovering from successful surgery for Cushing’s disease but did not occur in adults (despite having 723 adults in the series).

The symptomatology of pseudotumor cerebri arises from intracranial pressure reaching a point at which it causes headaches, nausea/vomiting, and/or papilledema on fundoscopic examination and symptoms of blurry vision (2). If left untreated, the disorder can cause permanent visual loss. Other cranial nerve palsies can coexist because cranial nerve deficits of the third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, and 12th cranial nerves have been described, although abducens paralysis is most common (as high as 60%) (2,13).

Pseudotumor cerebri has been associated with excess exposure to glucocorticoids (3) and with adrenocortical insufficiency during glucocorticoid withdrawal (14). It is unclear from Cushing’s description of Minnie G. whether she had increased intracranial pressure caused by severe hypercortisolism or whether it was associated with steroid withdrawal associated with spontaneous remission of Cushing’s disease. Of the four reported cases of pseudotumor cerebri after resection of an ACTH-secreting adenoma, one occurred in a young adult (7), and the other three were in children (4,5,6). With our large case series of pediatric patients with Cushing’s disease, we have been able to establish the incidence and timing of its occurrence, identify predisposing factors, and further characterize the clinical syndromes of pseudotumor cerebri in patients who underwent surgery for Cushing’s disease. In most of our patients, the manifestation of pseudotumor cerebri during glucocorticoid withdrawal occurred within a few weeks after a reduction of the cortisol replacement dose. In all cases, pseudotumor cerebri manifested itself within 1 yr of surgery, often while the children were still undergoing a tapering dose of replacement cortisol therapy. Six of the seven patients were still on steroid replacement at the onset of pseudotumor symptoms.

There is limited information on the pathogenesis of pseudotumor cerebri after glucocorticoid withdrawal in the absence of a clear underlying cause. Both acute and chronic steroid administration is known to cause a decrease in cerebrospinal fluid production (14). In addition, it has been shown in canine studies that the abrupt cessation of steroids can cause a substantial reduction in cerebrospinal fluid absorption and a subsequent increase in resistance to cerebrospinal fluid flow (15,16). Thus, abnormalities in cerebrospinal fluid dynamics during the glucocorticoid withdrawal may lead to high intracranial pressures.

Treatment of pseudotumor cerebri in our patients was varied, although all cases resolved, illustrating that this is a reversible phenomenon, given enough time to recover from the steroid withdrawal syndrome that follows successful surgery. Treatment is similar to the treatment of sporadic pseudotumor cerebri, with the expectation that it will remit with the resolution of the steroid withdrawal syndrome: 1) lumbar puncture to monitor intracranial pressure and to reduce it; 2) acetazolamide to reduce cerebrospinal fluid production; and/or 3) steroids to counteract the patient’s relative hypocortisolemia compared with the previous hypercortisolism.

Conclusions

Pseudotumor cerebri can be a sequelae of successful surgery for Cushing’s disease that occurs as cortisol exposure declines. Headache, visual changes, or other symptoms of intracranial hypertension in a child who recently underwent successful surgery for Cushing’s disease should prompt an evaluation for pseudotumor cerebri. Rapid diagnosis, including an ophthalmological examination and diagnostic lumbar puncture and treatment, beginning by increasing the steroid dose, and, with acetazolamide and lumbar puncture as needed, can correct the pathophysiology and prevent ophthalmological sequelae.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the following physicians who cared for the patient in the illustrated case report: Dr. Leland Albright, pediatric neurosurgery, and Dr. David Allen, pediatric endocrinology, University of Wisconsin, Madison; Dr. James Findling, endocrinology, Medical College of Wisconsin; and Dr. Michael Thorner, endocrinology, University of Virginia.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), intramural National Institutes of Health (NIH) project Z01-HD-000642-04.

E.N.K. will be awarded the Louise Eisenhardt Resident Award for Women in Neurosurgery for this abstract at the American Association of Neurological Surgeons meeting to be held in May 2010 in Philadelphia.

Disclosure Summary: All authors have no conflict of interest to report.

First Published Online February 17, 2010

Abbreviation: CD, Cushing’s disease; ACTH, adrenocorticotropin hormone.

References

- Stewart PM 2008 The adrenal cortex. In: Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, eds. Williams textbook of endocrinology. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 480 [Google Scholar]

- Klein S, Romjin JA 2008 Obesity. In: Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, eds. Williams textbook of endocrinology. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1572 [Google Scholar]

- Rickels MR, Nichols CW 2004 Pseudotumor cerebri in patients with Cushing’s disease. Endocr Pract 10:492–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt VJ, Dearlove JC, Savage D, Griffith HB, Hartog M 1994 Benign intracranial hypertension after pituitary surgery for Cushing’s disease. Postgrad Med J 70:115–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer EG, Anast CS 1982 Pseudotumor cerebri following removal of an adrenocorticotropic hormone-secreting pituitary adenoma. Neurosurgery 10:297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MN, Page LK, Bejar RL 1983 Cushing’s disease in childhood: benign intracranial hypertension after transsphenoidal adenomectomy; case report. Neurosurgery 13:195–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin NA, Linfoot J, Wilson CB 1981 Development of pseudotumor cerebri after the removal of an adrenocorticotropic hormone-secreting pituitary adenoma: case report. Neurosurgery 8:699–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushing H 1912 Case XLV. The pituitary body and its disorders. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 217–221 [Google Scholar]

- Fishman RA 2005 Brain edema and disorders of intracranial pressure. In: Rowland LP, ed. Merrit’s neurology. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 360–364 [Google Scholar]

- Wall M 1991 Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurol Clin 9:73–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon K 1997 Pediatric pseudotumor cerebri: descriptive epidemiology. Can J Neurol Sci 24:219–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babikian P, Corbett J, Bell W 1994 Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in children: the Iowa experience. J Child Neurol 9:144–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinciripini GS, Donahue S, Borchert MS 1999 Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in prepubertal pediatric patients: characteristics, treatment and outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol 127: 178–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato O, Hara M, Asai T, Tsugane R, Kageyama N 1973 The effect of dexamethasone phosphate on the production rate of cerebrospinal fluid in the spinal subarachnoid space of dogs. J Neurosurg 39:480–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston I, Gilday DL, Hendrick EB 1975 Experimental effects of steroids and steroid withdrawal on cerebrospinal fluid absorption. J Neurosurg 42:690–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston I 1973 Reduced C.S.F. absorption syndrome: reappraisal of benign intracranial hypertension and related conditions. Lancet 2:418–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]