Abstract

Background

No studies report if improvements to commercial weight loss programs affect retention and weight loss. Similarly, no studies report if enrolling in a program through work (with a corporate partner) affects retention and weight loss.

Objectives

To determine if: 1) adding evidenced-based improvements to a commercial weight loss program increased retention and weight loss, 2) enrolling in a program through work increased retention and weight loss, and 3) if increased weight loss was due to longer retention.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Data were collected on 60,164 adults who enrolled in Jenny Craig’s Platinum Program over one year in 2001–2002. The program was subsequently renamed the Rewards Program and improved by increasing treatment personalization and including motivational interviewing. Data were then collected on 81,505 Rewards participants who enrolled during 2005 (2,418 of these participants enrolled through their employer, but paid out-of-pocket).

Measurements

Retention (participants were considered active until ≥42 consecutive days were missed) and weight loss (percent of original body weight) from baseline to the last visit (data were evaluated through week 52).

Results

Alpha was set at .001. Mean (95% CI) retention (weeks), was significantly higher among Rewards [19.5 (19.4–19.6)] compared to Platinum [16.3 (16.2–16.4)] participants, and Rewards Corporate [25.9 (25.0–26.8)] compared to Non-corporate [21.9 (21.7–22.1)] participants. Modified intent-to-treat analyses indicated that mean (95% CI) percent weight loss was significantly larger among Rewards [6.36 (6.32–6.40)] compared to Platinum [5.45 (5.41–5.49)] participants, and Rewards Corporate [7.16 (6.92–7.40)] compared to Non-corporate [6.20 (6.16–6.24)] participants, with and without adjustment for baseline participant characteristics. In all cases, greater weight loss was secondary to longer retention.

Limitations

The study was not a randomized controlled trial, rather, a translational effectiveness study.

Conclusions

Improvements to a commercial program and enrolling through a corporate partner are associated with greater weight loss that is due to improved retention.

Keywords: weight loss, commercial programs, obesity, effectiveness, Jenny Craig, diet, retention

Introduction

The prevalence of overweight and obesity has increased significantly over the past four decades, resulting in 66% of the adult population in the United States (U.S.) being classified as overweight or obese (1). Consequently, a large proportion of the population in the U.S. qualifies for weight loss treatment based on the National Institutes of Health (NIH) treatment recommendations (2) and 46% of women and 33% of men are trying to lose weight (3). Many people attempt to lose weight through commercial weight loss programs, yet there are few peer-reviewed scientific articles that report data from commercial programs (4, 5). An article published in 2007, however, reported retention rates and weight loss data for 60,164 participants who enrolled in the Jenny Craig Platinum Program from May 2001 to May 2002 and who were followed for 52 weeks (6). Jenny Craig has since created a more intense and personalized program, the Rewards Program, which includes a number of improvements. Additionally, Jenny Craig has developed partnerships with corporations to deliver weight loss services to company employees. These changes should increase the effectiveness of the weight loss services, and such effectiveness data could help consumers and referring clinicians make informed decisions about commercial weight loss programs.

Based on internal research and empirical findings from clinical trials, Jenny Craig made changes to their program to improve client retention and promote greater weight loss. These improvements include greater personalization of treatment, setting progressive behavior change goals, an increased use of motivational interviewing, and providing discounts based on length of participation. Data were collected before and after Jenny Craig modified the program, providing the opportunity to empirically evaluate if these changes improved weight loss and retention. Such results would provide important real-world effectiveness data that is not attainable during efficacy trials conducted in academic or medical centers.

The purpose of this study was to compare the previously reported retention rates and weight loss from the Platinum Program (6) to the improved Rewards Program. Additionally, retention and weight loss were compared between the Rewards Program and the less intense Gold Program, and between Rewards participants who enrolled through a corporate partner and those who did not. It was hypothesized that retention and weight loss would be significantly greater in the: 1) more intense Rewards Program compared to the Platinum Program, 2) Rewards compared to Gold Program, and 3) Rewards participants who enroll through a corporate partner compared to those who did not. Covariate analyses were also conducted to determine if longer retention or participation accounted for greater weight loss.

Methods

Weight Loss Programs

Detailed information about Jenny Craig’s weight loss services has been published previously (6). In brief, weight management is promoted through behavior change, including healthy eating and physical activity (exercise). Weight management recommendations are developed by registered dietitians and a multidisciplinary Medical Advisory Board. Services are provided through weekly individual meetings between the client and a trained consultant, who personalizes treatment recommendations to promote long-term weight management and lifestyle change. The expected rate of weight loss is 1 to 2 pounds (0.45 to 0.91 kg) per week. Personalized meal plans are developed for each client and typically range from 1200 kcal/day to 2000 kcal/day. Clients purchase approximately $11 to $17 per day of pre-packaged portion-controlled foods per week and the use of these foods is to foster adherence to the meal plan. Physical activity goals are based on the client’s preferences, abilities, and stage of readiness, but the goal is to obtain 30 minutes or more of physical activity five or more days per week, which is consistent with the recommendations of national and governmental organizations (7, 8).

Jenny Craig offers a variety of programs that vary in intensity and duration, and the purpose of this study was to compare retention rates and weight loss among the programs.

Platinum Program

The Platinum Program, described in detail elsewhere (6), was 52 weeks in duration and it included weekly individual consultations that focused on modifying diet and physical activity. One year outcome data for clients who enrolled in the Platinum Program between May 2001 and May 2002 were reported previously(6) and the current analysis compared results of the Platinum Program to the improved Rewards Program.

Rewards Program

The Rewards Program is 52 weeks in duration and is similar to the Platinum Program, though the following enhancements were made to improve weight loss and retention. First, clients complete a YourStyle® questionnaire and the results are used to personalize services to accommodate the client’s lifestyle, eating habits, exercise readiness, and attitudes and preferences towards foods, physical activity, and weight loss. Second, in the first five weeks of treatment, the client learns about the three pillars of the behavior change approach: Food, Body, and Mind. Clients learn to create healthy eating habits that include portion control and being aware of emotional, social, and unconscious eating (the Food pillar). The meal plan incorporates Jenny Craig’s portion-controlled food, but also includes store-bought foods such as fresh fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, unsaturated fats, and whole grains. Hence, a heart-healthy meal plan is established that utilizes strategies to maximize fullness, such as Volumetrics® or consuming a diet low in energy density. Clients also learn to create an active lifestyle and establish realistic goals to increase physical activity that are tailored to the client’s preferences, schedule, and readiness for change (the Body pillar). Finally, clients learn to create balance in their lifestyles, enhancing self-awareness, acceptance, and moderation in weight loss efforts and activity (the Mind pillar). The aim of this approach is to foster motivation and self-efficacy, and to set obtainable incremental diet and physical activity goals, while managing stress and demands on the client’s time. Clients are also provided with ongoing email support to foster and maintain behavior change over the long-term.

The third enhancement is a rewards system, which includes discounts on the cost of pre-packaged foods that are dependent on the length of participation. The fourth enhancement is motivational interviewing. Jenny Craig consultants are provided with training in motivational interviewing and they employ this strategy throughout the course of treatment to foster retention and improve weight loss. Finally, clients that reach their weight loss goal and participate in the maintenance program receive support in the form of monthly consultations, program materials, and evidence-based relapse prevention strategies.

Gold Program

The Gold Program is six-months (26 weeks) in duration. It is designed to provide clients with weight loss services, including individual and personalized counseling, though the program does not include support for weight loss maintenance. Hence, the Gold Program is shorter in duration and less intense than the Rewards Program.

Corporate Program

Recently, Jenny Craig partnered with corporations and health care providers and these partnerships allow employees to enroll in weight management programs through their employer. Participating corporations advertise the partnership through promotional flyers, newsletters, and internal websites, as well as a sponsored web page. In many instances, the partnership with Jenny Craig is part of a broader wellness and health promotion program, and participation is promoted through incentives (e.g., discounts on insurance premiums). These partnerships offer important advantages. Service delivery is more cost-effective and clients who enroll in a program through work receive a discount; therefore, corporate clients might have the ability to purchase more portion-controlled foods or enroll in a more intense program. Additionally, enrolling through a corporate partner conveys to the client that their employer is invested in their health and progress, and the client might perceive greater social support and accountability for behavior change compared to a client who enrolls individually. Corporate clients have the same choices of programs, however, and choose to enroll in the program of their choice. Further, corporate clients pay for these services out-of-pocket and the company does not subsidize their participation in the program.

Participants

Platinum Program

Data from the 2001–2002 Platinum program included 60,164 adult men and women and has been described previously (6).

Rewards and Gold Programs

The study sample included 81,505 Rewards and 3,426 Gold adult participants who enrolled between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2005 and who were followed for a maximum of 52 weeks. Three percent (2,418) of the Rewards participants enrolled through a corporate partner. Participants were excluded if their baseline body weight data were missing (268 participants) or if their weekly weight change was ≥7 kg (1,235 participants), which might represent a data entry error1. The sample was restricted to participants aged 18–75 years or with missing age (3.4% or 2,884 participants). Nineteen percent (16,512 participants) of the sample had missing data on sex. Missing age and sex data were covariates in the analyses.

Outcome Variables

Data were collected in Jenny Craig clinics by trained consultants. Baseline body weight was recorded when the participant registered for a program and all data were entered and tracked on a computer program. Weekly body weight was recorded when participants attended their weekly one-on-one consultations. Weight loss was calculated as the change in weight from baseline to the last visit in kg and in percent of baseline body weight lost. Retention at each week of treatment was calculated as the percent of participants who presented to the clinic and provided a weight at that week of treatment or a subsequent week, assuming they presented to the clinic within 42 consecutive days (i.e., participants were considered inactive if they missed 42 or more consecutive days of the program). This cut-score was selected to allow comparisons between the previously published data (6) and the new data. Additionally, people rarely return to treatment after missing six weeks of treatment, but some do return and we chose to consider them drop-outs in an effort to accurately and conservatively depict the percent of participants who remained active and involved in treatment.

Statistical Analyses

Data were managed with SAS 9.0 software and statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 10.0 software.

Independent samples t-tests were used to test for differences in baseline participant characteristics between the Platinum and Rewards Program, Rewards and Gold Program, and Corporate and Non-corporate Rewards participants. Logistic regression analysis was used to test if the probability that a participant remained in the program was significantly different between programs at each week of participation (e.g., week 2 to 52).

Comparisons between the Platinum and Rewards Programs

Two series of analyses were used to test for weight loss differences between the Platinum and Rewards Programs. First, unadjusted percent weight loss was calculated for participants who provided a weight at baseline and weeks 13, 26, or 52. This “completers analysis” tested for differences between the two programs with an ordinary least squared model and controlled for participant characteristics (baseline body weight, age, and sex, including controls for missing age and sex data; weight loss goal, and an indicator of whether the weight loss goal was achieved within 2.3 kg) and adjusted for potential correlation in outcomes among participants from the same clinics. An analysis was also conducted that did not control for participant characteristics. Lastly, an analysis of weight loss was conducted controlling for length of program participation.

In the second series of analyses, unadjusted percent weight loss was calculated from baseline to the last visit (through week 52). This was consistent with a modified intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis; where all participants’ data were included in the analysis assuming they were weighed at baseline and at least one subsequent point within 42 days. The term modified ITT analysis is used since baseline values were not carried forward for the small percent of participants who failed to return to the clinic and provide a weight within 42 days after baseline. In this analysis, the last observation was carried forward (LOFC) for participants who prematurely dropped out of treatment; hence, missing data were not replaced with imputed values. This method was used to calculate weight loss for all other comparisons among programs (i.e., only one completers analysis was conducted and this analysis is described in the previous paragraph). Data were analyzed using a series of analyses similar to those described in the previous paragraph. In brief, an ordinary least squared model was performed controlling for participant characteristics and adjusting for correlation in outcomes among participants from the same clinics (an analysis was also conducted that did not control for participant characteristics). Lastly, an analysis of weight loss was conducted controlling for length of program participation.

Comparisons between the Rewards and Gold Programs

Methods similar to those described above were used for the comparison between Rewards and Gold members but they relied on data from 2005 only. Because the Gold program is only 6 months in duration, both retention and weight loss data were restricted to week 26. As noted previously, the analyses followed a modified ITT and LOCF approach.

Comparisons between Corporate and Non-corporate Rewards Participants

Comparison of the corporate and non-corporate participants also relied on the 2005 data. Both retention rates and weight loss were assessed through week 52 using similar methods as described above. The analyses followed a modified ITT and LOCF approach.

All weight loss analyses were repeated with weight loss in kg as the outcome variable. These analyses did not differ markedly from the analyses of percent weight loss; therefore, only the percent weight loss analyses are reported. In consideration of the number of participants, alpha level was set at .001.

Ethics

Data reported herein were collected in fee-for-service centers as part of ongoing clinical practice and service delivery. Data were anonymous; the research team had no access to identifiable data of any participant. Data were analyzed by an independent research company (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Results

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample

The demographic characteristics of participants in the Platinum, Rewards, and Gold Programs are reported in Table 1. The majority of participants were female and the mean age was approximately 43 years. Compared to the Rewards participants, Platinum and Gold participants were statistically significantly younger, but the age difference was small in magnitude. Rewards participants also weighed more at baseline than Platinum and Gold participants.

Table 1.

Baseline descriptive characteristics of participants in the Platinum, Rewards, and Gold Programs. All values are mean (95% CI), with the exception of the last row that depicts the percent of females in each sample.

| Platinum (n = 60 164) |

Rewards (n = 81 505) |

Gold (n = 3426) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||||

| Mean | Lower | Upper | Mean | Lower | Upper | Mean | Lower | Upper | |

| Age (years) | 43.2* | (43.1 | 43.3) | 43.7 | (43.6 | 43.8) | 42.5* | (42.1 | 42.9) |

| Baseline Weight (kg) | 89.9* | (89.7 | 90.1) | 92.2 | (92.1 | 92.3) | 85.9* | (85.3 | 86.5) |

| Weight loss goal (% of original body weight) | 24.3* | (24.2 | 24.4) | 25.1 | (25.0 | 25.2) | 22.3* | (22.0 | 22.6) |

| Average Length of Participation (weeks) | 16.3* | (16.2 | 16.4) | 19.5 | (19.4 | 19.6) | 9.2* | (9.0 | 9.4) |

| Female (%) | 92.0* | (91.8 | 92.2) | 89.7 | (89.5 | 90.0) | 93.0* | (92.1 | 93.9) |

| Rewards | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-corporate (n = 79 087) |

Corporate (n = 2418) |

|||||

| 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||

| Mean | Lower | Upper | Mean | Lower | Upper | |

| Age (years) | 43.6* | (43.5 | 43.7) | 44.9 | (44.4 | 45.4) |

| Baseline Weight (kg) | 92.1* | (92.0 | 92.2) | 93.4 | (92.6 | 94.2) |

| Weight loss goal (% of original body weight) | 25.0* | (24.9 | 25.1) | 26.0 | (25.6 | 26.4) |

| Average Length of Participation (weeks) | 21.9* | (21.7 | 22.1) | 25.9 | (25.0 | 26.8) |

| Female (%) | 89.6* | (89.4 | 89.8) | 92.8 | (91.8 | 93.8) |

Note.indicates statistically significant difference between the Rewards Program participants and the Platinum and Gold participants, and the Rewards Corporate and Non-corporate participants (p < .001).

Comparisons between the Platinum and Rewards Programs

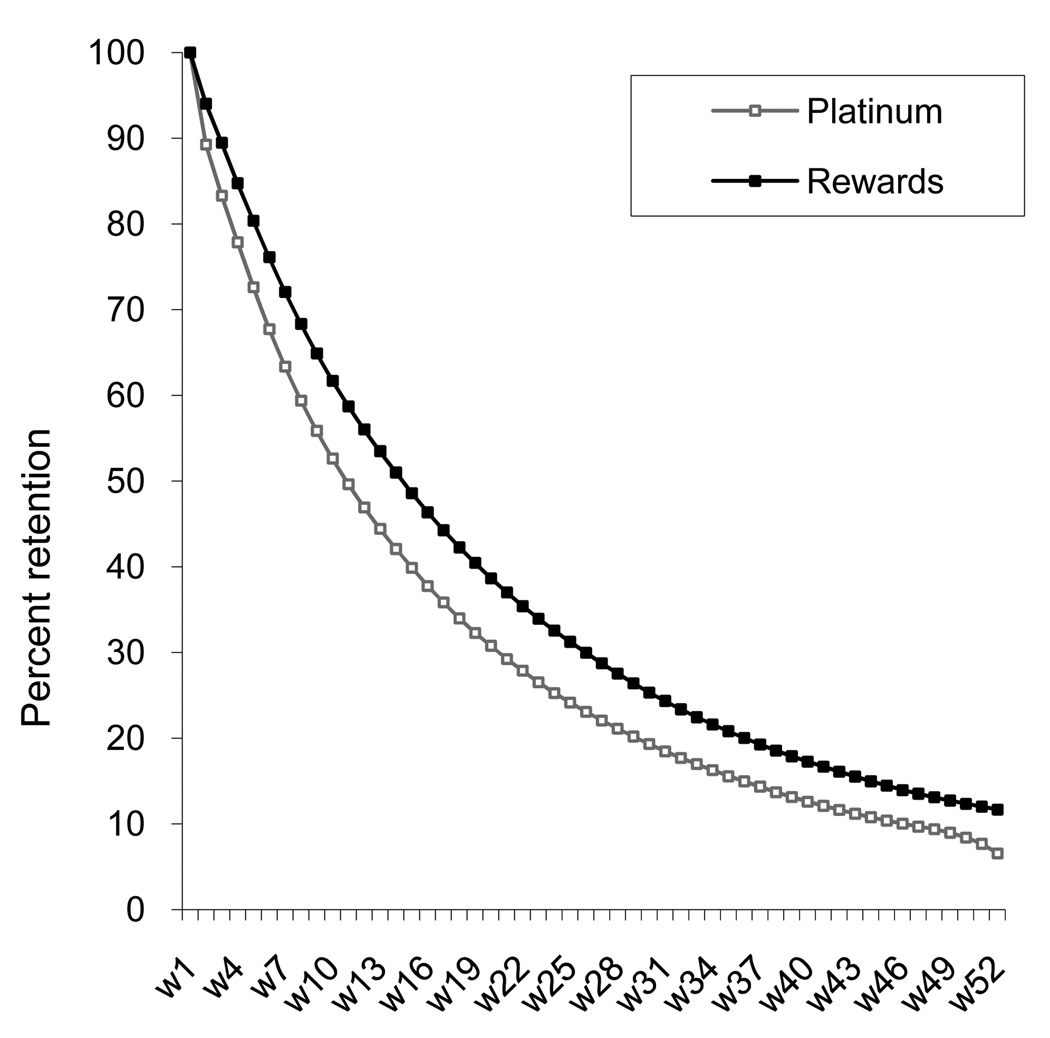

Compared to Platinum members, Rewards members had significantly (p-values < .001) higher retention rates on average (Table 1) and at every week during weeks 2 through 52 (Figure 1). Weight loss was significantly (p-values < .001) greater among Rewards compared to Platinum members at weeks 13, 26, and 52 (Figure 2) with or without adjustment for baseline participant characteristics.

Figure 1.

Logistic regression analysis indicated that retention rates were significantly (p-values < .001) higher in the Rewards compared to the Platinum Program from week 2 to 52. Abbreviation: W=week.

Figure 2.

Based on a completers analysis, the Rewards Program had significantly (p < .001) larger weight loss than the Platinum group at weeks 13, 26, and 52 with and without adjustment for baseline participant characteristics. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Weight loss from baseline to the last week of attendance was significantly greater (p < .001) among Rewards compared to the Platinum members (Figure 3) with or without adjustment for baseline participant characteristics. After also controlling for length of program participation, weight loss no longer significantly differed between the two groups (p = .88), indicating that the longer retention of participants in the Rewards Program accounted for the superior weight loss of this program compared to the Platinum Program.

Figure 3.

Compared to the Platinum Program, the Rewards Program had significantly (p < .001) larger weight loss, with or without adjustment for participant characteristics. This difference was no longer significant after also adjusting for length of program participation (p = .88). All analyses were modified ITT analysis with LOCF. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

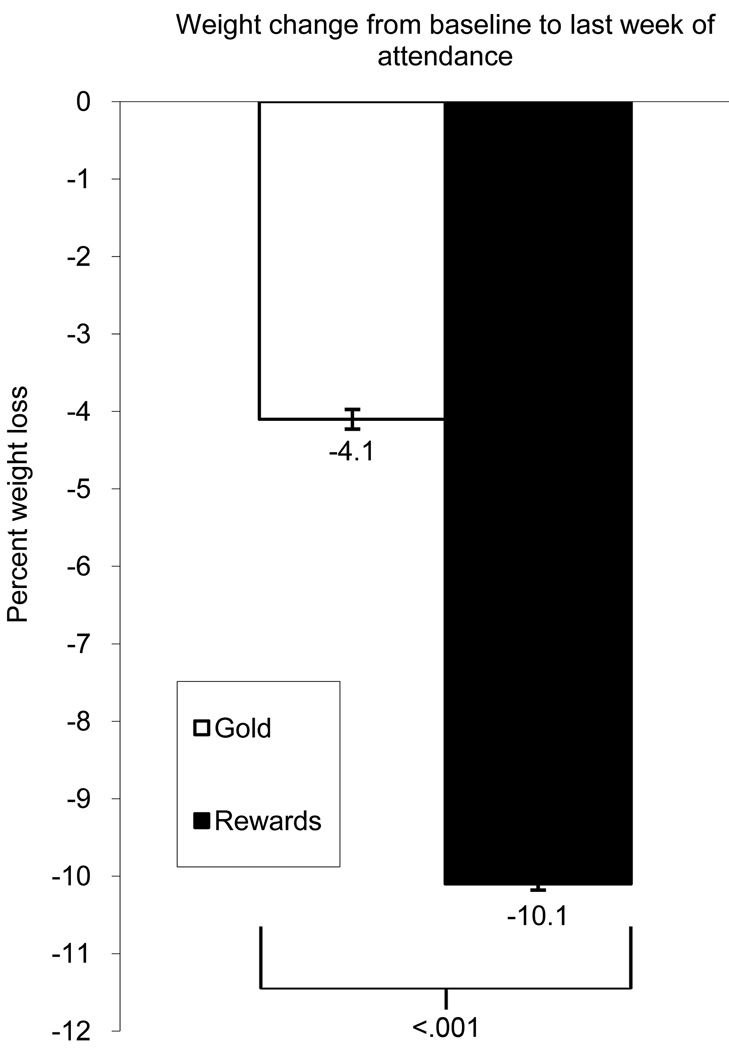

Comparisons between the Rewards and Gold Programs

Rewards participants had significantly higher (p < .001) retention from week 2 to 26 compared to Gold participants (Figure 4). Rewards participants had significantly (p < .001) higher weight loss with or without adjustment for participant characteristics (Figure 5). After controlling for participant characteristics and length of retention, weight loss did not differ significantly between the groups (p > .01).

Figure 4.

Rewards participants had significantly higher (p < .001) retention from weeks 2 to 26. Abbreviation: W=week.

Figure 5.

The Rewards Program had significantly (p < .001) higher weight loss compared to the Gold Program with and without adjustment for baseline participant characteristics. After controlling for length of retention, however, this difference was not significant (p > .01). All analyses were modified ITT analysis with LOCF. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

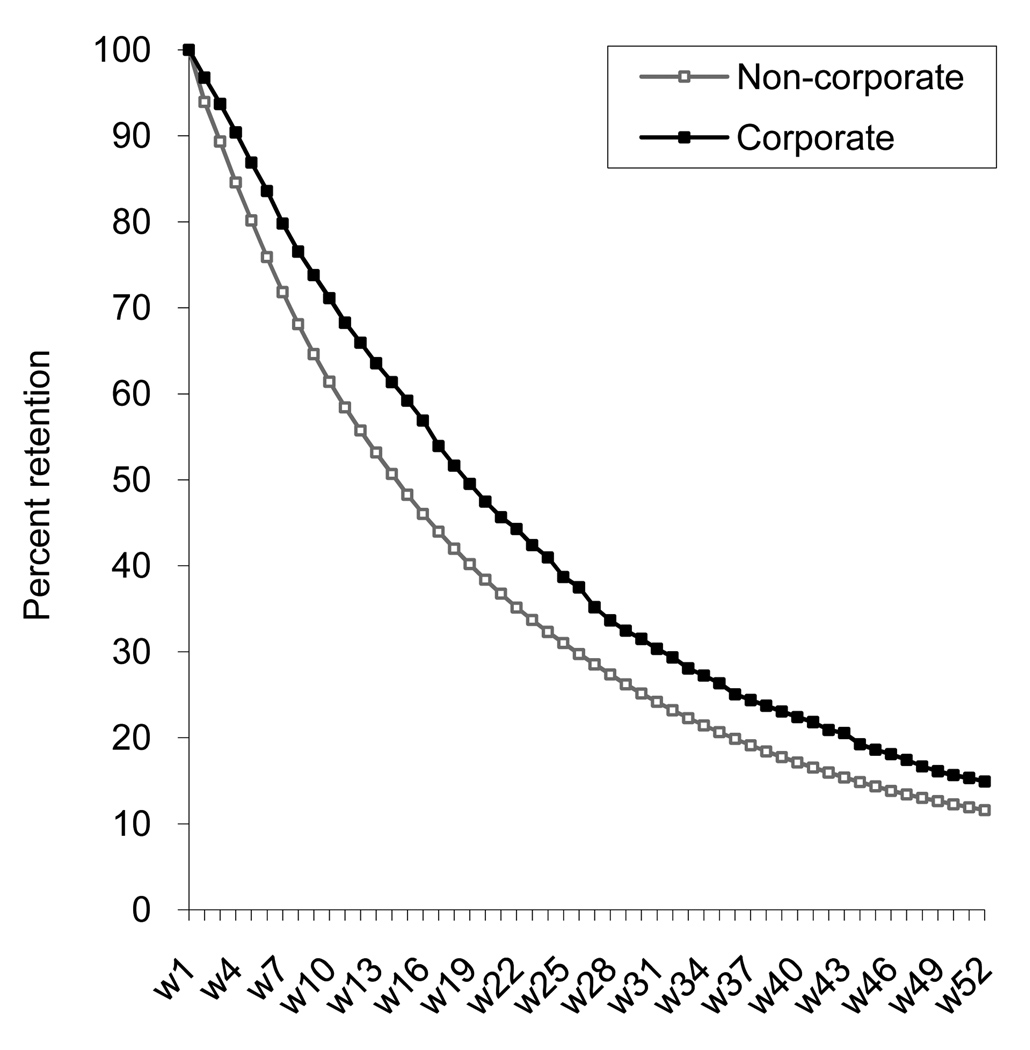

Comparisons between Corporate and Non-corporate Rewards Participants

Three percent of Rewards participants enrolled through a corporate partner. A larger proportion of Corporate Rewards participants were women compared to Non-corporate participants, and Corporate participants were significantly older and had a higher weight loss goal (Table 1). Compared to Non-corporate Rewards participants, Corporate participants had significantly higher retention rates on average (Table 1) and from week 2 to 52 (Figure 6), and significantly greater weight loss with and without controlling for baseline participant characteristics (p-values < .001; Figure 7). After controlling for length of participation, weight loss did not differ between Rewards Corporate and Non-corporate participants (p = .18).

Figure 6.

Compared to Non-corporate Rewards participants, Corporate Rewards participants had significantly higher retention rates from week 2 to 52 (p < .001). Abbreviation: W=week.

Figure 7.

Compared to Non-corporate participants, Corporate participants had significantly greater weight loss with or without controlling for baseline participant characteristics (p < .001). After also controlling for length of participation, weight loss did not differ between Rewards Corporate and Non-corporate participants (p = .18). All analyses were modified ITT analysis with LOCF. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Discussion

The results of the present study indicate that improvements to the Jenny Craig program were associated with longer participant retention and greater weight loss. Importantly, greater weight loss was secondary to improved retention. The findings from this effectiveness study are consistent with efficacy studies demonstrating that weight loss is associated with continued client-counselor contact (9–11), and that motivational interviewing promotes better adherence to weight-loss programs (12) and greater weight loss (13). The data reported herein from fee-for-service weight loss clinics is a significant strength of the study and demonstrates the translation of findings from efficacy (clinical) trials to “real-world” settings where the majority of people who seek weight loss treatment receive services.

The weight loss results from this effectiveness study are consistent with tightly controlled randomized efficacy trials. In a review of lifestyle interventions for weight loss, Wadden et al. (14) report that intensive lifestyle modification results in weight loss of approximately 10% after 26 weeks, and we found a 10.1% weight loss in the Rewards program at week 26 (Figure 5). Importantly, our analyses used a modified ITT analysis with LOCF, which is very similar to the types of data analyses used in randomized efficacy trials. Wadden et al. note that we are limited in what we know about weight loss because our knowledge is based on randomized controlled trials with motivated patients that receive services from experts located at medical or academic centers. The results reported herein, however, are based on real-world effectiveness data from community-based clinics, where most people receive weight loss services (4, 5, 14).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to empirically evaluate if retention and weight loss vary as a function of enrolling in a weight loss program via a corporate partner. The results demonstrate that retention and weight loss are superior when participants enroll through a corporate partner, and the greater weight loss is secondary to improved retention. These analyses evaluated participants who were in the same program (the Rewards Program); therefore, the only difference was corporate partnership, which provides services at a lower cost. It is possible that the lower cost allowed Corporate participants to purchase more portion-controlled foods, which could potentially promote greater weight loss. Additionally, Corporate participants might differ from other participants on other unobservable characteristics. For example, they might have perceived greater accountability due to the corporate partnership, assigned a greater value and legitimacy to the program, or perceived greater social support for behavior change. Although these conclusions are speculative, the results warrant further study of the positive role that corporate partnership can play in promoting health behavior among their employees.

The addition of evidence-based techniques to Jenny Craig’s weight loss program resulted in statistically significant improvements in retention and weight loss, yet the magnitude of the improvements could be considered relatively small. Mean retention and weight loss increased by 3.2 weeks and 0.9%, respectively. In the context of an efficacy study with a small sample size, the clinical significance of such differences might be in question. In the context of a large sample size (e.g., > 140,000) or a population-based study, however, such differences can be meaningful and have significant public health implications. As discussed in Wing et al. (15), seemingly small reductions in body weight or BMI can have a significant impact on the proportion of the population categorized as overweight or obese. Further, small amounts of weight loss can have a significant impact on health, as demonstrated in the Diabetes Prevention Program, which found that 1 kg of weight loss is associated with a reduction in risk of diabetes of 16% (16). Our results show a modest improvement in weight loss, though this modest effect can have a significant impact on health since it was demonstrated in a commercial program that serves over 500,000 people per year.

The data reported in this paper are also critical for empirically evaluating programs and the effects of programmatic changes on outcomes. The improvements to the Rewards program paid dividends by increasing retention and weight loss, and these incremental improvements represent important steps in the evolution of commercial weight loss programs. Additional improvements to the program can further improve retention and weight loss, increasing the effectiveness of the program over time. A cost-effectiveness analysis was beyond the scope of this paper, but it is noted that the primary initial costs involved personnel training. Theoretically, the cost and time associated with seeing each participant remained stable, but the counselors were able to use intervention techniques that were more effective in that time. Lastly, some of our comparisons illustrated large differences in retention and weight loss between programs, e.g., between the Gold and Rewards programs (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Although participants self-selected programs, these data can be used to identify programs that require modification and serve as a benchmark for empirical program evaluation following programmatic changes.

The retention data from this translational effectiveness study indicate high attrition in fee-for-service weight loss programs over one year, though these results are consistent with published reports from other fee-for-service programs. We found that 56% of Rewards program participants remained active after 12 weeks of treatment, which is comparable to the 12-week retention rate of 53.9% from a similar low-calorie diet program (17). As expected, the retention rates from real-world fee-for-service programs are lower than those observed in controlled efficacy trials. In their review of controlled efficacy trials, Wadden et al. (14) concluded that ~80% of participants complete 16 to 26 week interventions, while we found retention rates in the Rewards program of 46.4% and 30.0% at weeks 16 and 26, respectively. Several factors may be driving these differences between controlled efficacy trials and fee-for-service programs. First, participants in controlled efficacy trials frequently receive free services and remuneration for completion of assessments, while participants in fee-for-service clinics pay out-of-pocket for the services that they receive. Second, efficacy trials are typically conducted in controlled settings in a limited number of medical or academic centers rather than widely dispersed clinics located throughout the community.

The present study has a number of strengths, including the collection of effectiveness data, which has been missing from the scientific literature (4, 5, 14), on a large sample of people who voluntarily enrolled in fee-for-service weight loss programs. Furthermore, the observed weight loss data from this study are similar to the data reported from tightly controlled randomized trials (14), providing important evidence that the results from efficacy studies can be translated to fee-for-service clinics in the community. Lastly, these data provide important information on the effectiveness of commercial weight loss programs for clinicians and consumers, and these data clearly demonstrate that improved retention results in greater weight loss. The results suggest that weight loss treatments be refined to promote retention over the long-term.

The results of the study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. First, participants were not randomly assigned to the programs and there was no control group. Random assignment, particularly to a control group, is not feasible in fee-for-service programs. Nevertheless, testing the intervention with successive enrollees in fee-for-service programs is a significant study strength. Second, data from the Platinum and Rewards programs were collected at different points in time; hence, differences between the groups could be due to factors unrelated to changes to the intervention. This was a necessary aspect of the study design since the program was changed systematically following collection of the Platinum data and it was unfeasible to make improvements to only a subsample of the Jenny Craig centers. Participant characteristics were also covaried in the analyses to control for differences in participant characteristics between the two samples. Third, participants were followed for one year, though no additional follow-up data were collected, and retention was low after one year of treatment. Fourth, the sample was predominantly female, yet the sample was representative of people who seek commercial weight loss treatment, which is a significant strength. Lastly, the sample was large and statistical power high; hence, alpha levels were adjusted and the results were discussed in terms of population-based studies and studies with large sample sizes.

Summary

Improvements to the Jenny Craig program, including greater personalization of treatment, motivational interviewing, setting progressive behavior change goals, corporate partnership, and providing discounts based on length of participation, were associated with longer participant retention and greater weight loss. Improved weight loss was secondary to longer retention, and the weight loss observed in this effectiveness study was similar to weight loss from tightly controlled randomized efficacy trails (14). In the context of studies with large sample sizes or population-based studies, the improvement in weight loss observed in this study has meaningful implications for health risk reduction. This study provides important translational and effectiveness data, which has been missing from the scientific literature despite its importance (4, 5, 14). Further, the results provide referring clinicians and consumers with data on the effectiveness of a readily available fee-for-service commercial weight loss program. Future research is warranted to identify individual characteristics that affect retention and weight loss in an effort to empirically guide program enhancement and improve effectiveness.

Acknowledgements

C. Martin receives funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants K23 DK068052 and R03 DK083533, and NIH and National Science Foundation grant R21 AG032231.

Footnotes

The analyses reported herein were conducted with and without the 1,235 (~2%) participants who were excluded due to weight change ≥; 7 kg. Inclusion of these participants did not affect the results and mean weight loss did not change.

Conflicts of Interest

In addition to the NIH grants listed in the Acknowledgements Section, C. Martin receives honoraria for lectures from scientific, educational, and lay groups, and he received partial reimbursement for travel expenses in the form of research funds totaling less than $725 from Jenny Craig Inc. A. Hymel is also funded by NIH grants. L. Talamini and A. Johnson are employed by Jenny Craig Inc. O. Khavjou is employed by an independent research company.

References

- 1.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States--gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHLBI. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bish CL, Blanck HM, Serdula MK, Marcus M, Kohl HWI, Khan LK. Diet and physical activity behaviors among Americans trying to lose weight: 2000 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;13:596–607. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamilton M, Greenway F. Evaluating commercial weight loss programmes: an evolution in outcomes research. Obes Rev. 2004;5:217–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai AG, Wadden TA. Systematic review: an evaluation of major commercial weight loss programs in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:56–66. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-1-200501040-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finley CE, Barlow CE, Greenway FL, Rock CL, Rolls BJ, Blair SN. Retention rates and weight loss in a commercial weight loss program. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:292–298. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, Haskell WL, Macera CA, Bouchard C, et al. Physical activity and public health. A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273:402–407. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. U.S Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Atlanta, GA: 1996. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perri MG, McAdoo WG, McAllister DA, Lauer JB, Yancey DZ. Enhancing the efficacy of behavior therapy for obesity: effects of aerobic exercise and a multicomponent maintenance program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:670–675. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.5.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perri MG, McAllister DA, Gange JJ, Jordan RC, McAdoo G, Nezu AM. Effects of four maintenance programs on the long-term management of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:529–534. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perri MG, Nezu AM, McKelvey WF, Shermer RL, Renjilian DA, Viegener BJ. Relapse prevention training and problem-solving therapy in the long-term management of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:722–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith DE, Heckemeyer CM, Kratt PP, Mason DA. Motivational interviewing to improve adherence to a behavioral weight-control program for older obese women with NIDDM. A pilot study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:52–54. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.West DS, DiLillo V, Bursac Z, Gore SA, Greene PG. Motivational interviewing improves weight loss in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1081–1087. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Byrne KJ. Efficacy of lifestyle modification for long-term weight control. Obes Res. 2004;12(Suppl):151S–162S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wing RR, Pinto AM, Crane MM, Kumar R, Weinberg BM, Gorin AA. A statewide intervention reduces BMI in adults: Shape Up Rhode Island results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:991–995. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamman RF, Wing RR, Edelstein SL, Lachin JM, Bray GA, Delahanty L, et al. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2102–2107. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin CK, O'Neil PM, Pawlow L. Changes in food cravings during low-calorie and very-low-calorie diets. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:115–121. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]