Abstract

Nearly all engineered tissues must eventually be vascularized to survive. To this end, we and others have recently developed methods to synthesize extracellular matrix-based scaffolds that contain open microfluidic networks. These scaffolds serve as templates for the formation of endothelial tubes that can be perfused; whether such microvascular structures are stable and/or functional is largely unknown. Here, we show that compounds that elevate intracellular concentrations of the second messenger cyclic AMP (cAMP) strongly normalize the phenotype of engineered human microvessels in microfluidic type I collagen gels. Cyclic AMP-elevating agents promoted vascular stability and barrier function, and reduced cellular turnover. Under conditions that induced the highest levels of cAMP, the physiology of engineered microvessels in vitro quantitatively mirrored that of native vessels in vivo. Computational analysis indicated that cAMP stabilized vessels partly via its enhancement of barrier function.

Keywords: microvascular tissue engineering, collagen gels, permeability, microfluidic channels, cyclic AMP

1. Introduction

The formation of a functional microcirculation is critical to obtaining clinically relevant volumes of engineered tissue [1–3]. Many approaches to vascularization have been studied, such as the incorporation of angiogenic growth factors [4] or vascular cells in scaffolds [5, 6], the assembly of endothelialized microscale tissues into packed beds [7], and the sprouting of an arteriovenous loop in a confined space [8]. To engineer human blood microvessels in vitro, we and others have proposed to form microfluidic channels in extracellular matrix (ECM)-based gels, and to use these channels as templates to grow endothelial tubes [9, 10] and networks [11, 12]. Although the resulting vascular structures appear stable, little is known about their functionality or how to enhance it. For instance, long-term stability is required to maintain perfusion, but the signals that can promote vascular stability in these scaffolds are largely unknown. Likewise, size- and charge-selective barrier function is desirable in maintaining appropriate levels of transport between the vascular and tissue compartments [13]. Methods to replicate the barrier function of continuous vascular beds would be useful to avoid excessive interstitial flows or water content in engineered tissues.

In this work, we examined the effect of the second messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) on the long-term stability and barrier function of blood microvessels in microfluidic type I collagen gels. We chose to study cAMP in part because a large body of literature has shown that this compound enhances barrier function in vivo [14–16] and in vitro [17–19]. Previously, we showed that cAMP reduced the permeability to bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 10 kDa dextran in engineered lymphatic tubes in vitro [20]; since micro-lymphatics provide a non-selective, leaky wall that helps to drain tissues, cAMP inhibited the barrier “function” of the lymphatic tubes. Given the substantial differences between endothelial cells derived from blood and lymphatic microvessels [21], it was not clear whether cAMP would result in the same or opposite effects in tubes of blood microvascular endothelial cells. In the current study, we examined the effect of cAMP on the size and charge selectivities of engineered blood microvessels. We also determined whether cAMP affected other vascular behaviors—specifically, long-term stability and quiescence—that would be of benefit when engineering functional vessels for perfusion. We then used computational models to understand how the downstream effects of cAMP could be causally linked.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Formation of perfused human microvessels in collagen gels

Endothelial tubes (n = 207) were formed by seeding human dermal microvascular blood endothelial cells (lot # 5F1293 and 6F4144 from Lonza; lot # 7082905.1 from PromoCell) in 120-μm-diameter channels in type I collagen gels (8 mg/ml final concentration; BD Biosciences), essentially as previously described [10, 20]. Tubes were perfused with media that contained 0 μM, 20 μM, or 80 μM dibutyryl cAMP (db-cAMP; Sigma), or 400 μM db-cAMP and 20 μM Ro-20-1724 (Calbiochem), a cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor [22]. The pressure difference across the ends of tubes was ~4.4 cm H2O. All media was supplemented with 3% dextran (70 kDa; Sigma).

2.2 Measurement of permeabilities and leak densities

On day 3 past seeding, permeability assays were performed using methods adapted from previous studies [20, 23, 24]. Fluorescent solutes were introduced through the lumen of a microvessel from an inlet reservoir. Fluorescence images were obtained through a Plan-Neo 10×/0.3 NA objective each minute from the ninth to thirtieth minute of perfusion in an environmental chamber held at 37°C. All images were corrected for non-uniform illumination with Axiovision ver. 4.3 (Zeiss).

Effective permeability coefficients Pe were calculated from , where ΔI was the average intensity of the image at complete filling of the lumen, dI/dt was the linear rate of increase of average intensity after filling, and R was the radius of the lumen. In contrast to previous work [20, 24], here the regions-of-interest for permeability calculations were not chosen to avoid leaky regions. The pairwise solutes used (all from Invitrogen) were Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated bovine serum albumin (50 μg/ml) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated 10 kDa dextran (20 μg/ml), or Texas Red-conjugated 40 kDa dextran (125 μg/ml) and fluorescein-conjugated 40 kDa dextran (35 μg/ml). The 40 kDa dextrans were spun down in a 10 kDa cut-off filter (Millipore) before use to remove free dye.

Leaks within vessels consisted of two types. “Focal” leaks, defined as localized leakage of solutes, were counted manually and presented as number of leaks per frame per millimeter. Smaller leaks (“IgG leaks”) were visualized by perfusion with antibody to type I collagen (mAb COL-1; Sigma). Antibodies were bound to Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated Fab fragments before use (Zenon; Invitrogen). Microvessels were perfused for 1 hour with media that contained 1 μg/ml antibody (i.e., ~2 μg/ml antibody-dye complex), flushed with antibody-free media for 1 hour, and then fixed for 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde by perfusion. Confocal images of IgG leaks were obtained with a Plan-Apo 10×/0.40 NA objective using an Olympus IX81 inverted microscope. Sequential images from each microvessel were taken at 4.3 μm spacing, and stacked with ImageJ ver. 1.41o (NIH). Relative amounts of IgG leaks were quantified by measuring the area stained (within the microvessel but excluding edges) in the stacked images and normalizing to the total image area of the microvessel.

To obtain the effective permeability of a single focal leak, we re-analyzed the fluorescence images from the permeability assay and calculated the permeability in a region-of-interest clearly away from focal leaks. The permeability per focal leak was obtained by subtracting this value from the original permeability (which included leaks), normalized by the number of leaks.

2.3. Lifespan assay

We defined microvessel “death” as the day when endothelial delamination from the gel was first observed and/or when the flow rate decreased to below 50% of the peak flow rate. Delamination near vessel outlets occurred, but did not appear to alter the functionality or stability of regions upstream. Vessels that survived to day 14 were given a lifespan of 14 days, and considered “censored” in the statistical analysis of survival curves. For lifespan measurements, microvessels were supplied with fresh media every 2 days.

2.4. Proliferation and apoptosis assays

Proliferation rates were determined by measuring incorporation of the thymidine analog 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU), using a commercial kit (Invitrogen) [25]. On day 3 past seeding, vessels were perfused with media that contained 10 μM EdU for 4 hours and then flushed with EdU-free media for at least 1 hour. Microvessels were then fixed by perfusing with 4% paraformaldehyde, and EdU-stained nuclei were labeled with Alexa Fluor 594 with a “click” reaction, according to manufacturer’s instructions. To stain all nuclei, microvessels were perfused with Hoechst 33342 (2 μg/ml; Invitrogen) for 10 min. The number of EdU-positive cells were counted from fluorescence images, and normalized by total number of nuclei; out-of-focus nuclei near vessel walls were not counted. At least 500 nuclei were counted per microvessel.

Pyknotic nuclei were recognized by fragmented or shrunken morphology [26], and their numbers were expressed as a percentage of total number of nuclei.

2.5. Contractility assay

We measured radial strain of microvessels under “dropwise” perfusion [27], in which the pressure head was 0–1 mm H2O, to minimize pressure-induced distention of the channels. Diameters of channels before seeding were measured at two spots and averaged, and likewise for vessels on day 3 past seeding. Strain was calculated as the difference in diameters divided by the initial, unseeded diameter.

2.6 Measurement of physical properties of collagen scaffolds

We performed creep tests on collagen gels using a rheometer (AR2000; TA Instruments) with a cone diameter of 41 mm and tilt angle of 2°. Gels were formed at 24°C for two hours directly on the sample plate. To avoid dehydration of gels, we added droplets of PBS to the edge of the gel after 30 minutes of gelation; since a large fraction of collagen fibrils have formed by this time [28], adding PBS should not alter gel properties substantially. Gels were strained for 5 hr at shear stresses of 25, 50, 75, or 100 Pa.

To measure the hydraulic conductivity of collagen gels, we subjected rectangular collagen gels to a pressure drop and measured the resulting flow of PBS at 37°C [29]. Hydraulic conductivity K was calculated according to , where Q is the measured flow rate, L = 8 mm is the length of the gel, A = 1.25 mm2 is the cross-sectional area of the gel, ΔP = 5.3 cm H2O is the imposed pressure difference, ηPBS = 0.7 cP is the viscosity of PBS at 37°C, and ηmedia = 1.35 cP is the viscosity of perfusate at 37°C.

2.7 Numerical modeling of pressure diffusion in collagen gels

To understand the coupling between focal leaks and vascular stability, we modeled changes in scaffold pressure upon the introduction of one or more focal leaks of various sizes. Following Detournay and Cheng [30] and Mow et al. [31], we treated the fibers and liquid in the gel as incompressible. The diffusion constant for pressure in a porous medium is given by , where G is the shear modulus from rheometry and ν is the Poisson’s ratio under drained condition (assumed to be 0.2 [32]). We implemented the diffusion equation in a finite element model with Comsol Multiphysics ver. 3.5a (Comsol) to obtain pressures within the gel as a function of time after introduction of one or more leaks.

2.9 Statistical analysis

Permeabilities and size and charge selectivities are presented as geometric means ± 95% CI. Densities of focal leaks and IgG leaks, and proliferative and apoptotic fractions are presented as arithmetic means ± SD. Pairwise comparisons used the Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction; correlations used the Spearman’s test. For lifespan assays, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed, and significance in trend and pairwise comparisons were tested with the log-rank test. All tests were performed with Prism ver. 5 (GraphPad).

3. Results

3.1. Formation of microvessels in the absence and presence of cyclic AMP-elevating agents

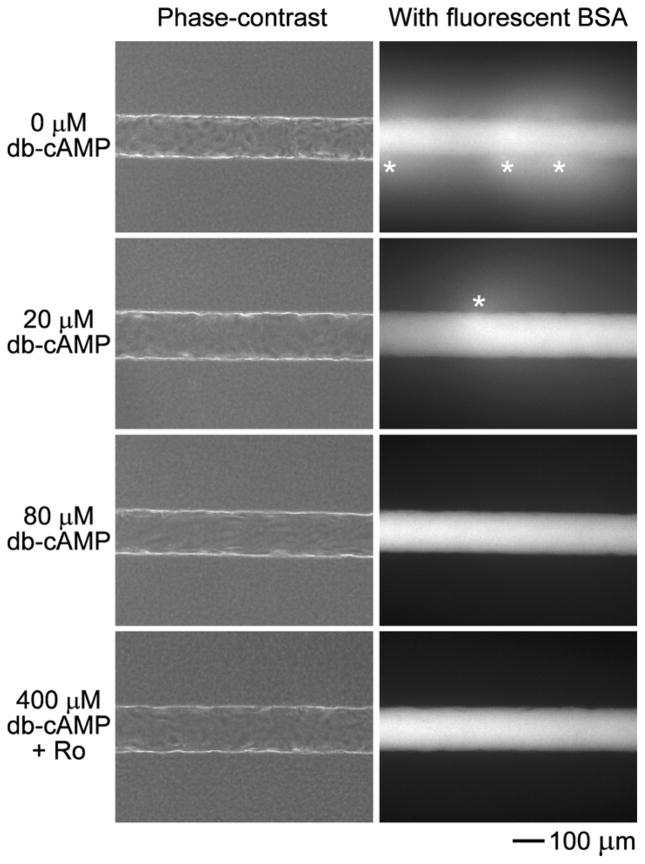

Under all conditions, seeded endothelial cells formed a confluent monolayer within two days after seeding. As noted previously, tubes expanded slightly once confluence was reached [10]. Measured on day 3 past seeding, the lengths of these tubes were 7.8 ± 0.2 mm, the diameters were 139.3 ± 6.3 μm, and the flow rates were 0.9 ± 0.1 mL/hr. Under phase-contrast imaging, vessels with or without cAMP-elevating agents looked very similar at day 3 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Phase-contrast and fluorescence images of vessels perfused with 0 μM db-cAMP, 20 μM db-cAMP, 80 μM db-cAMP, or 400 μM db-cAMP and 20 μM Ro-20-1724, and fluorescently labeled BSA. Asterisks denote focal leaks.

3.2. Effect of cyclic AMP on barrier function of engineered microvessels

In the absence of cAMP, microvessels exhibited a high permeability and numerous focal leaks (Fig. 1). The permeabilities to BSA, 10 kDa dextran, fluorescein-40 kDa dextran, and Texas Red-40 kDa dextran were , and , respectively. The density of focal leaks was 1.6 ± 2.1 per mm. Focal leaks were often dynamic structures that opened and closed transiently (see Movie in Supplementary Data).

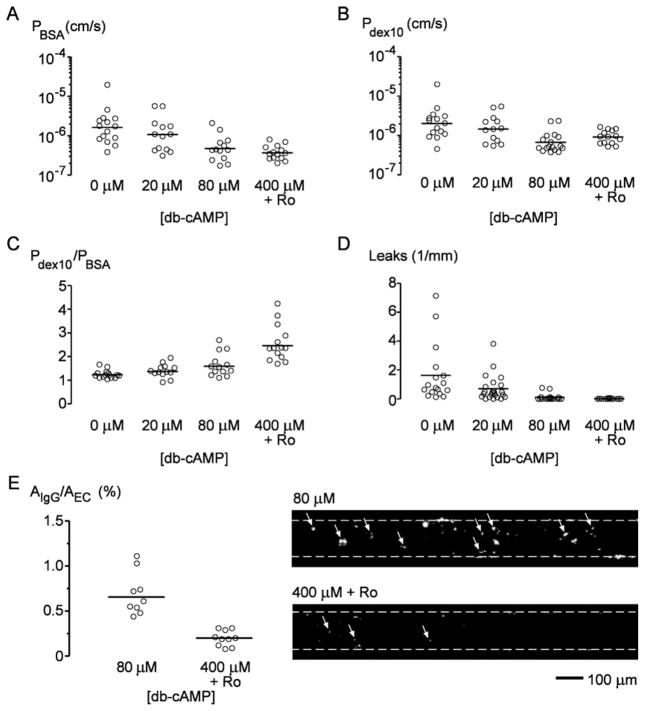

Cyclic AMP-elevating agents play a major role in the regulation of microvascular barrier function in vivo [16, 33], such as during inflammation-induced vascular hyperpermeability and edema [34]. We therefore hypothesized that cAMP would also improve the barrier function of engineered blood microvessels, as we have shown in lymphatic microvessels [20]. We perfused blood microvessels with 20 μM or 80 μM dibutyryl cAMP (db-cAMP), or 400 μM db-cAMP and 20 μM cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor Ro-20-1724; this last condition should lead to saturating amounts of cAMP, as described previously in an in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier [35]. We found that cAMP reduced the permeability to BSA (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2A), 10 kDa dextran (p = 0.001; Fig. 2B), fluorescein-40 kDa dextran (p < 0.0001; Fig. 3A) and Texas Red-40 kDa dextran (p < 0.0001; Fig. 3B). The density of focal leaks greatly decreased to 0.1 ± 0.2 per mm with 80 μM db-cAMP (p < 0.0001), and further to ~0 per mm with 400 μM db-cAMP and Ro-20-1724 (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2D). Perfusion with fluorescently labeled antibodies to collagen type I provided a means to probe for leaks that were smaller than focal leaks (so-called “IgG leaks”), thus distinguishing barriers with the lowest permeabilities. Microvessels cultured with 80 μM db-cAMP showed 3.5 times more stained area than those cultured with 400 μM db-cAMP and Ro-20-1724 (p = 0.0006; Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

Effect of cAMP-elevating agents on barrier function of engineered vessels. (A) Permeability to bovine serum albumin (PBSA). (B) Permeability to 10 kDa dextran (Pdex10). (C) Size selectivity, defined as Pdex10/PBSA. (D) Density of focal leaks. (E) Density of IgG leaks labeled by antibody to type I collagen, expressed as normalized area. Right, fluorescence images of vessels labeled by antibody to collagen, with dotted lines denoting vessel walls and arrows indicating IgG leaks.

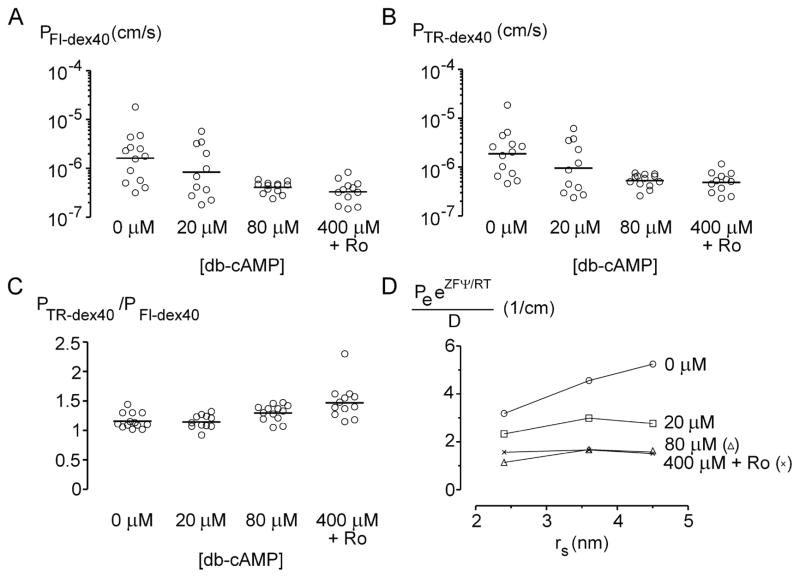

Figure 3.

Effect of cAMP-elevating agents on charge barrier of engineered vessels. (A) Permeability to anionic fluorescein-40 kDa dextran (PFl-dex40). (B) Permeability to neutral Texas Red-40 kDa dextran (PTR-dex40). (C) Charge selectivity, defined as PTR-dex40/PFl-dex40. (D) Plot of normalized permeabilities PeeZFΨ/RT/D versus solute radius. The potential difference Ψ was calculated from the selectivities in (C) using a solute-partitioning model [50] (see text).

To study how cAMP altered the selectivity of the vascular barrier, we measured permeabilities to BSA and 10 kDa dextran, or to anionic fluorescein-40 kDa dextran and neutral Texas Red-40 kDa dextran simultaneously. Higher concentrations of cAMP increased charge selectivity, defined as the ratio of permeabilities to Texas Red over fluoresceinated dextrans (p < 0.0001), with the highest selectivity at cultured with 400 μM db-cAMP and Ro-20-1724 (Fig. 3C). The size selectivity between BSA (Stokes-Einstein radius of 3.6 nm) and 10 kDa dextran (2.4 nm [36]), defined as the ratio of permeabilities to 10 kDa dextran over BSA, also increased with cAMP concentrations (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2C), with the highest selectivity of in tubes cultured with 400 μM db-cAMP and Ro-20-1724. Altogether, these data demonstrate that cAMP reduced solute permeabilities, decreased the occurrence of leaks, and increased selectivities in engineered vessels.

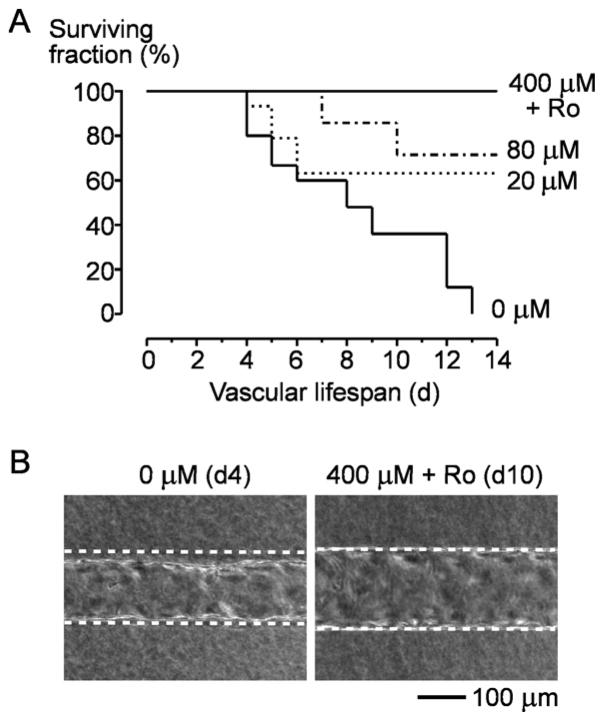

3.3. Effect of cyclic AMP on mechanical stability of engineered microvessels

Survival curves showed that cAMP increased vascular lifespan (p < 0.0001; Fig. 4A). Vessels grown without cAMP invariably failed within 14 days, with most dying within 8–9 days. These vessels typically delaminated throughout the tube, leaving large gaps between the endothelium and collagen gel (Fig. 4B, left). Vessels cultured with 80 μM db-cAMP had a two-week survival rate of 71% (p = 0.0031, compared to 0 μM db-cAMP). Remarkably, all vessels that were perfused with 400 μM db-cAMP and Ro-20-1724 were stable for at least two weeks (p < 0.0001, compared to 0 μM db-cAMP); the longest lifespan we observed was seven weeks. These tubes did not delaminate from the gel (Fig. 4B, right).

Figure 4.

Effect of cAMP-elevating agents on vascular stability. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Vessel “death” was defined as the day when the flow rate decreased to below 50% of its maximum and/or when delamination was observed in the upstream half of the tube. (B) Representative images of vessels under long-term perfusion. Dotted lines indicate walls of the collagen channels.

3.4. Effect of cyclic AMP on cell turnover in engineered microvessels

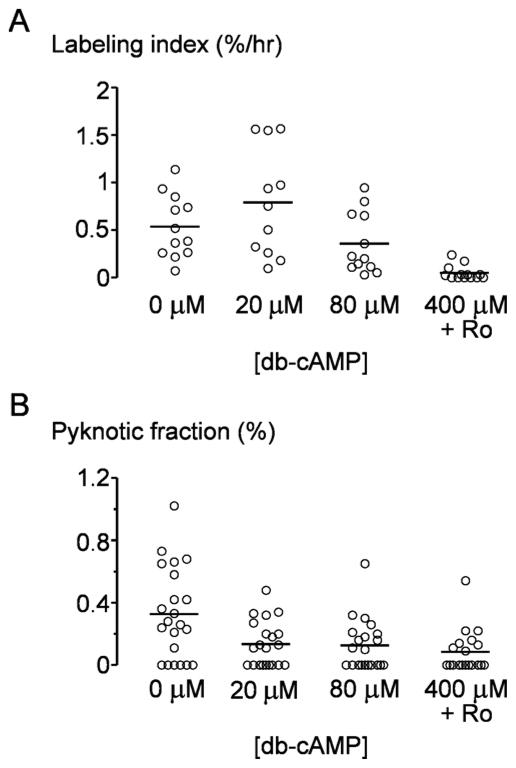

Cyclic AMP also induced cellular quiescence within vessels, as determined by labeling cells in S phase with the thymidine analog EdU and by counting pyknotic nuclei (Fig. 5). Tubes cultured with 400 μM db-cAMP and Ro-20-1724 showed drastically lower EdU labeling at 0.05 ± 0.08% per hour, compared with 0 μM db-cAMP (p < 0.0001), 20 μM db-cAMP (p < 0.0001), and 80 μM db-cAMP (p = 0.0008). Apoptotic fractions, measured as the fraction of cells that exhibited pyknotic nuclei, also decreased with higher cAMP concentrations (p = 0.0009; Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Effect of cAMP-elevating agents on cellular turnover. (A) Proliferation rate, measured from incorporation of EdU. (B) Apoptotic fraction, measured from pyknotic nuclei.

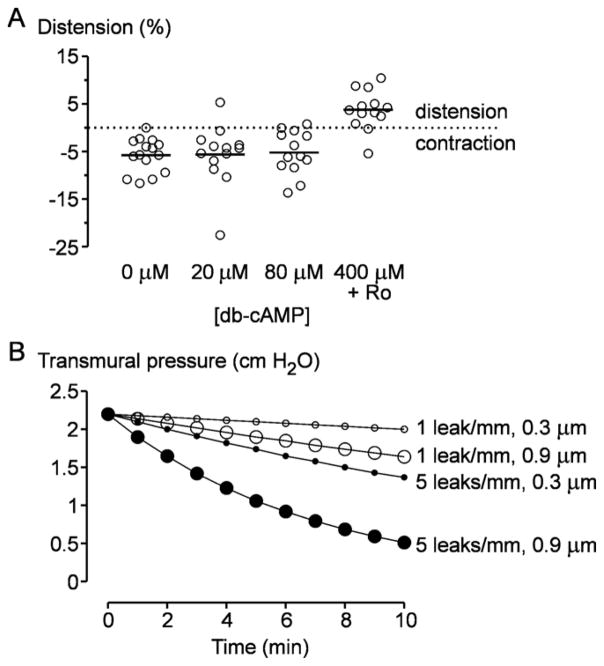

3.5. Roles of decreased contractility and improved barrier function in cAMP-mediated stability

Since cAMP is known to reduce endothelial cell contractility [37, 38], we reasoned that high levels of cAMP might prolong vascular lifespan by preventing endothelial collapse. Surprisingly, we found that only the highest concentrations of cAMP affected contractility (Fig. 6A): 0, 20 and 80 μM db-cAMP resulted in −5% radial strain (i.e., contraction), whereas 400 μM db-cAMP and Ro-20-1724 resulted in +4% strain (i.e. distension) (p < 0.0001, = 0.0002, and < 0.0001 for 400 μM db-cAMP and Ro-20-1724 compared to 0, 20 and 80 μM db-cAMP, respectively). Thus, reduction in contractility may partly explain the enhanced lifespan of microvessels cultured with saturating amounts of cAMP, but it cannot explain why 80 μM db-cAMP also promoted longer survival.

Figure 6.

Mechanisms of cAMP-induced vascular stabilization. (A) Effect of cAMP-elevating agents on contraction of collagen gels. (B) Plots of transmural pressure versus time for various densities and sizes of focal leaks. These plots were compiled from computational models of fluid pressure within the gels upon opening of leak(s). Densities and sizes of leaks were taken from experimental results (Fig. 2D and text).

Vessels that were cultured without cAMP had numerous focal leaks (Fig. 2D) and exhibited poor survival (Fig. 4A). Since focal leaks act to equilibrate pressures between the lumen and the collagen gel, we hypothesized that enhancement of the barrier by cAMP may prevent vessel collapse by maintaining a low pressure in the collagen gel and, thus, a high transmural pressure (lumenal pressure minus gel pressure). As we cannot measure pressures in the gel directly, we used computational models to determine the effects of focal leaks in reducing transmural pressure.

First, we estimated the physical size of focal leaks based on their contribution to permeability. We reasoned that the opening of focal leaks led to fluid flux into the gel, and that this flux enhanced convective transport of fluorescent solutes, leading to an increase in permeability. Flow in collagen gels obeys Darcy’s law v = −K∇P, where v is the velocity vector, K is hydraulic conductivity of gel, and P is the fluid pressure in the gel. Assuming focal leaks can be modeled as circular apertures, the fluid flux from a leak is given by Q = 4KPtr0, where Pt is the transmural pressure and r0 is the radius of the focal leak [39]. Thus, the effective permeability Pleak due to convective flux of solute from leaks is given by , where R is the vascular radius.

We measured the effective permeability per focal leak per mm to be 1.7 ± 2.1×10−6 cm/s (range: 2.6 × 10−7 to 6.4 × 10−6 cm/s), corresponding to an average focal leak radius of 0.23 μm (range: 0.04 to 0.86 μm), using K = 3.1 × 10−8 cm4/dyn·s and R = 75 μm.

Second, we modeled the collagen gel surrounding the microvessel as a thick-walled, linearly elastic cylinder, so that εr = Pt/2G, where εr is the radial strain of vessels at day 3 (~25%), and G is the shear modulus of the gel [40]. Since microvessels reached confluence on day 2 and permeability measurements were performed on day 3, we used the long-term G from creep experiments by extrapolating the linear portion of compliance values to 1 day, obtaining G = 440 ± 60 Pa (n = 4). Average transmural pressure was thus calculated to be 220 Pa.

Finally, we modeled pressure diffusion in collagen gels numerically. Because focal leaks opened and closed on the time-scale of minutes, we used a short-term G of 1500 Pa obtained from creep experiments. The computational models placed various numbers of focal leaks (radii of 0.3 or 0.9 μm) on the tube with an initial transmural pressure of 220 Pa. We then calculated the transmural pressure at a point diametrically opposed to a leak as a function of time after leak opening. These results showed that focal leaks substantially lowered transmural pressure within minutes (Fig. 6B): In 10 min, a leak of 0.9 μm per mm of vessel length decreased transmural pressure by nearly 30%, and five leaks of the same size decreased transmural pressure by over 75%. Our results thus indicate that, in vessels cultured with low levels of cAMP, the resulting focal leaks can destabilize vessels through loss of transmural pressure.

4. Discussion

4.1 Summary of major findings

In tubes formed from blood microvascular endothelial cells within microfluidic collagen gels in vitro, the major effects of cAMP were: 1) reduction of permeability to BSA and dextrans (10 kDa and 40 kDa) and increase in size and charge selectivity, 2) reduction in number of leaks, 3) enhancement in vessel stability, and 4) reduction in cell turnover. Reduction in cell contraction with high cAMP levels was not sufficient in explaining enhanced vessel stability; rather, computational studies showed that the non-leaky phenotype induced by cAMP can contribute to vascular stability by maintaining a large, positive transmural pressure.

4.2 Comparison with in vivo vessels

To what extent does treatment with cAMP normalize vascular phenotype in collagen gels in vitro? Previous results with tubes of lymphatic endothelial cells showed that cAMP increased size selectivity [20], but since micro-lymphatics are normally non-selective structures in vivo [41], cAMP acts against vascular normalization in these tubes. In contrast, continuous blood vessels exhibit strong, selective barrier function in vivo. Moreover, these vessels do not collapse or delaminate (except under pathological conditions), and the substantial enhancement of lifespan by cAMP in vitro is important to obtain in vivo-like stability. Below, we compare the barrier function and turnover rates of blood vessels in vitro (with and without cAMP) and in vivo.

4.2.1 Normalization of barrier function

In vivo, continuous vessels of the skin, muscle, brain, lung, and other organs have strong barrier function [13, 42, 43]. Few, if any, focal leaks are observed under baseline conditions; leaks appear primarily during endothelial activation (e.g., during inflammation) [44]. Permeabilities to BSA typically lie in the range of 1–5 × 10−7 cm/s in venules [13]. Vessels exhibit both size and charge selectivity, and various models have estimated the vessel wall to contain pores of 4–5 nm in radius, which is small enough to restrict the transport of BSA and larger solutes [43]. Solute-partitioning models estimate that the negative fixed charge density is at least 10 meq/L [45, 46].

Using these benchmarks, engineered vessels that are grown without cAMP compare poorly. Without cAMP, tubes contained numerous leaks that were much larger (>0.1 μm) than the size of solutes examined. Thus, these vessels exhibited essentially no selectivity, with all permeability coefficients being nearly identical (~2 × 10−6 cm/s).

Supplementation with high levels of cAMP normalized barrier function in several respects. First, the number of focal leaks was reduced to essentially zero. Second, the selectivity of 10 kDa dextran to BSA increased to 2.5; for comparison, a ratio of 3.6 was found from a study of clearance in canine hindpaw [47]. Third, the selectivity of neutral (Texas Red-labeled) to anionic (fluoresceinated) 40 kDa dextran increased to 1.5.

To better understand the effects of cAMP on transport pathways in these tubes, we used pore theory and solute-partitioning models to explain the observed data. For solutes of same size but different charge, these models yield a charge selectivity of e−ΔZFΨ/RT,, where ΔZ is the difference in solute charges, Ψ is the membrane potential, F is Faraday’s constant, R is the gas constant and T is temperature. The charge of fluoresceinated dextran 40 kDa was −10, considering the charge of fluorescein at pH 7.4 [48] and the stoichiometry of labeling, according to the manufacturer; Texas Red-conjugated dextran is neutral. The measured selectivity of 1.5 is thus equivalent to a membrane potential of −1.0 mV. A negative potential indicates a negatively charged membrane; using a Donnan potential analysis [49, 50], we found this potential to be equivalent to a negative fixed charge density of 10.4 meq/L.

Normalizing permeabilities to the charge selectivity and to the solute diffusion coefficient D yielded a picture of the transport pathways (Fig. 3D). If solute transport was purely diffusional, then the normalized permeability PeeZFΨ/RT/D would be a decreasing function of solute radius [51]. If solute transport was purely convective, then the normalized permeability would be an increasing function of solute radius [51, 52]. Figure 3D thus shows that convection dominates in the absence of cAMP, presumably via the focal leaks. In contrast, transport becomes more balanced between diffusion and convection as cAMP levels increase.

Although cAMP greatly suppresses the hyper-leaky phenotype in engineered microvessels, it does not completely normalize the barrier function. Plots of Pe/D versus solute radius for in vivo data decrease rapidly beyond a threshold of ~3 nm [13], whereas our in vitro data did not exhibit this sharp drop. Even with high levels of cAMP, the size selectivity of vessels in vitro did not match that in vivo, and methods to enhance the formation of additional size-selective structures (e.g., glycocalyx [53]) may be required for complete normalization.

4.2.2 Normalization of cell turnover

Endothelial turnover is extremely low in vivo [54, 55], except in pathological conditions such as wound healing or tumor angiogenesis [55, 56]. Normal turnover rates are on the order of 0.1% per day, as measured by labeling with radioactive thymidine [54]. Without cAMP, engineered vessels exhibited a hyperproliferative phenotype, with ~2% of cells incorporating EdU during a four-hour pulse. This phenotype is consistent with the rich content of growth factors in the perfusate. Only at the highest levels of cAMP did proliferative rates decrease; surprisingly, these rates reached values comparable with those in vivo, with most tubes devoid of labeled cells. Although addition of cAMP did reduce the number of pyknotic nuclei, we consistently observed such nuclei even at the highest concentrations; these dying cells may be residual artifacts from the seeding procedure.

4.3 Mechanisms of vascular normalization

How does cAMP exert its pleotropic benefits? We noticed that the dose-response curves to cAMP differed among the various vascular functions: Some outputs (e.g., leaks) were sensitive to small amounts of cAMP, whereas others (e.g., proliferation) required saturating amounts. These characteristic dose-responses allowed the downstream effects to be grouped, and provided hints of the underlying mechanisms of normalization.

Changes to lifespan and density of focal leaks reached saturating effects by 80 μM db-cAMP; thus, we expected these two outputs to be related. Indeed, computational models indicated that leaks would increase the pressure within the gel, leading to a loss of transmural pressure and favoring collapse. To the best of our knowledge, our results are the first to suggest a causal link between barrier dysfunction (specifically, the presence of focal leaks) and eventual collapse in engineered vessels. If the same link exists when vascularizing other types of scaffolds, then a strong barrier function will be required (but not necessarily sufficient) to obtain patent vessels for long-term perfusion.

In contrast, cAMP-mediated reduction in contractility did not appear to correlate with either lifespan or focal leaks. Instead, lowered contractility was observed only with 400 μM db-cAMP and Ro-20-1724, a dose-response that mirrored that for proliferation. Thus, we suspect that contractility and proliferation are coupled in these tubes, which is consistent with the proliferative effect of contraction-mediated signaling observed in cultured cells [57].

4.4 Applications in tissue engineering

It is natural to ask how one might use cAMP to normalize microvessels in tissue engineering applications that involve other cell types. Cyclic AMP is a ubiquitous second messenger whose effects are hardly confined to endothelial cells [58]. Thus, one would expect that flooding an engineered tissue with cAMP—although it may lead to functional vessels for perfusion—may exert undesirable effects on surrounding non-vascular cells. Moreover, cAMP also tightens the barrier of lymphatic tubes [20], which may lead to loss of drainage capacity. We believe that, for our results to find eventual application, cAMP must be delivered locally via liposomes or some other targeting agent. For instance, cellular uptake of cAMP can be an order of magnitude higher if cAMP is loaded in phospholipid vesicles rather than in free solution [59, 60]; these studies suggest that a working concentration of cAMP could be significantly lowered with controlled release from encapsulating agents in the perfusate that selectively deliver cAMP locally to the endothelium.

Assuming cAMP can be sequestered and locally delivered, our work indicates a remarkably simple way to obtain in vivo-like barrier function and vascular stability. In vivo, failure to maintain a proper barrier is usually associated with pathological conditions, such as edema [61] and compartment syndrome [62]. When engineering tissues, barrier function in engineered microvessels could be tuned to create an optimal tissue microenvironment. For example, cardiac cells are sensitive to interstitial shear stress [63], and the incorporation of functional vessels within engineered cardiac constructs may be one way to shield these cells from excessive convective flow. We note that the large numbers of vascular leaks observed without cAMP would likely lead to interstitial flows of several micrometers per second, which is roughly an order of magnitude higher than normal [64].

In view of the wide variety of natural and synthetic biomaterials used as scaffolds, it would be useful to know whether cAMP can normalize blood microvessels in scaffolds other than type I collagen gels. Due to the rich documentation of cAMP in enhancing endothelial function, we expect that most normalization effects would still hold in non-collagenous microfluidic scaffolds.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates how the second messenger cAMP can control the phenotype of engineered blood microvessels in vitro. We found that increasing cAMP provides a simple method to normalize the function of vessels in microfluidic collagen gels in vitro. Vessels that were treated with the highest levels of cAMP-elevating agents resembled in vivo tissues in their quantitative physiology, albeit not completely. Methods to further increase size selectivity are a natural next step. More broadly, our work suggests that functional vascularization of other microfluidic scaffolds [65, 66] may benefit from supplementation with cAMP-elevating agents.

Supplementary Material

Fluorescence time-lapse of an endothelial tube that was perfused with Texas Red-40kDa dextran in the absence of db-cAMP. The time between frames is one minute.

Acknowledgments

We thank Celeste Nelson and Gavrielle Price for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering under award EB005792. Part of this work was performed during sabbatical leave (J.T.) in the Nelson Group in the Department of Chemical Engineering at Princeton University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lovett M, Lee K, Edwards A, Kaplan DL. Vascularization strategies for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng B. 2009;15:353–70. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2009.0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lokmic Z, Mitchell GM. Engineering the microcirculation. Tissue Eng B. 2008;14:87–103. doi: 10.1089/teb.2007.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouwkema J, Rivron NC, van Blitterswijk CA. Vascularization in tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:434–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee KY, Peters MC, Anderson KW, Mooney DJ. Controlled growth factor release from synthetic extracellular matrices. Nature. 2000;408:998–1000. doi: 10.1038/35050141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schechner JS, Nath AK, Zheng L, Kluger MS, Hughes CC, Sierra-Honigmann MR, et al. In vivo formation of complex microvessels lined by human endothelial cells in an immunodeficient mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9191–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150242297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tremblay P-L, Hudon V, Berthod F, Germain L, Auger FA. Inosculation of tissue-engineered capillaries with the host s vasculature in a reconstructed skin transplanted on mice. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1002–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGuigan AP, Sefton MV. Vascularized organoid engineered by modular assembly enables blood perfusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11461–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602740103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lokmic Z, Stillaert F, Morrison WA, Thompson EW, Mitchell GM. An arteriovenous loop in a protected space generates a permanent, highly vascular, tissue-engineered construct. FASEB J. 2007;21:511–22. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6614com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vernon RB, Gooden MD, Lara SL, Wight TN. Native fibrillar collagen membranes of micron-scale and submicron thicknesses for cell support and perfusion. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1109–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chrobak KM, Potter DR, Tien J. Formation of perfused, functional microvascular tubes in vitro. Microvasc Res. 2006;71:185–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golden AP, Tien J. Fabrication of microfluidic hydrogels using molded gelatin as a sacrificial element. Lab Chip. 2007;7:720–5. doi: 10.1039/b618409j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price GM, Chu KK, Truslow JG, Tang-Schomer MD, Golden AP, Mertz J, et al. Bonding of macromolecular hydrogels using perturbants. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6664–5. doi: 10.1021/ja711340d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michel CC, Curry FE. Microvascular permeability. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:703–61. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adkins WK, Barnard JW, May S, Seibert AF, Haynes J, Taylor AE. Compounds that increase cAMP prevent ischemia-reperfusion pulmonary capillary injury. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:492–7. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.2.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adamson RH, Liu B, Fry GN, Rubin LL, Curry FE. Microvascular permeability and number of tight junctions are modulated by cAMP. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H1885–H94. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.6.H1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He P, Zeng M, Curry FE. Dominant role of cAMP in regulation of microvessel permeability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1124–H33. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casnocha SA, Eskin SG, Hall ER, McIntire LV. Permeability of human endothelial monolayers: effect of vasoactive agonists and cAMP. J Appl Physiol. 1989;67:1997–2005. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.5.1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stelzner TJ, Weil JV, O’Brien RF. Role of cyclic adenosine monophosphate in the induction of endothelial barrier properties. J Cell Physiol. 1989;139:157–66. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041390122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patterson CE, Davis HW, Schaphorst KL, Garcia JGN. Mechanisms of cholera toxin prevention of thrombin- and PMA-induced endothelial cell barrier dysfunction. Microvasc Res. 1994;48:212–35. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1994.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Price GM, Chrobak KM, Tien J. Effect of cyclic AMP on barrier function of human lymphatic microvascular tubes. Microvasc Res. 2008;76:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amatschek S, Kriehuber E, Bauer W, Reininger B, Meraner P, Wolpl A, et al. Blood and lymphatic endothelial cell-specific differentiation programs are stringently controlled by the tissue environment. Blood. 2007;109:4777–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-053280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergstrand H, Kristoffersson J, Lundquist B, Schurmann A. Effects of antiallergic agents, compound 48/80, and some reference inhibitors on the activity of partially purified human lung tissue adenosine cyclic 3′,5′-monophosphate and guanosine cyclic 3′,5′-monophosphate phosphodiesterases. Mol Pharmacol. 1977;13:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huxley VH, Curry FE, Adamson RH. Quantitative fluorescence microscopy on single capillaries: α-lactalbumin transport. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:H188–H97. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.252.1.H188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Price GM, Tien J. Methods for forming human microvascular tubes in vitro and measuring their macromolecular permeability. In: Khademhosseini A, Suh K-Y, Zourob M, editors. Biological Microarrays (Methods in Molecular Biology series) Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salic A, Mitchison TJ. A chemical method for fast and sensitive detection of DNA synthesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2415–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712168105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willingham MC. Cytochemical methods for the detection of apoptosis. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47:1101–10. doi: 10.1177/002215549904700901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price GM, Tien J. Subtractive methods for forming microfluidic gels of extracellular matrix proteins. In: Bhatia SN, Nahmias Y, editors. Microdevices in Biology and Engineering. Boston, MA: Artech House; 2009. pp. 235–48. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wood GC, Keech MK. The formation of fibrils from collagen solutions. 1. The effect of experimental conditions: kinetic and electron-microscope studies. Biochem J. 1960;75:588–98. doi: 10.1042/bj0750588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Truslow JG, Price GM, Tien J. Computational design of drainage systems for vascularized scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4435–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Detournay E, Cheng AH-D. Fundamentals of poroelasticity. In: Fairhurst C, editor. Comprehensive Rock Engineering: Principles, Practice and Projects; Vol II: Analysis and Design Method. New York, NY: Pergamon Press; 1993. pp. 113–71. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mow VC, Kuei SC, Lai WM, Armstrong CG. Biphasic creep and stress relaxation of articular cartilage in compression: theory and experiments. J Biomech Eng. 1980;102:73–84. doi: 10.1115/1.3138202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barocas VH, Moon AG, Tranquillo RT. The fibroblast-populated collagen microsphere assay of cell traction force--Part 2: Measurement of the cell traction parameter. J Biomech Eng. 1995;117:161–70. doi: 10.1115/1.2795998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan SY. Protein kinase signaling in the modulation of microvascular permeability. Vascul Pharmacol. 2003;39:213–23. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(03)00010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seibert AF, Thompson WJ, Taylor A, Wilborn WH, Barnard J, Haynes J. Reversal of increased microvascular permeability associated with ischemia-reperfusion: role of cAMP. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:389–95. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.1.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubin LL, Hall DE, Porter S, Barbu K, Cannon C, Horner HC, et al. A cell culture model of the blood-brain barrier. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1725–35. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.6.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venturoli D, Rippe B. Ficoll and dextran vs. globular proteins as probes for testing glomerular permselectivity: effects of molecular size, shape, charge, and deformability. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F605–F13. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00171.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morel NML, Dodge AB, Patton WF, Herman IM, Hechtman HB, Shepro D. Pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell contractility on silicone rubber substrate. J Cell Physiol. 1989;141:653–9. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041410325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goeckeler ZM, Wysolmerski RB. Myosin phosphatase and cofilin mediate cAMP/cAMP-dependent protein kinase-induced decline in endothelial cell isometric tension and myosin II regulatory light chain phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33083–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503173200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hobson EW. The Theory of Spherical and Ellipsoidal Harmonics. New York, NY: Chelsea Publishing Company; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eringen AC. Mechanics of Continua. New York, NY: Wiley; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ikomi F, Hunt J, Hanna G, Schmid-Schönbein GW. Interstitial fluid, plasma protein, colloid, and leukocyte uptake into initial lymphatics. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:2060–7. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.5.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor AE, Granger DN. Exchange of macromolecules across the microcirculation. In: Renkin EM, Michel CC, editors. Handbook of Physiology; Section 2: The Cardiovascular System. Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society; 1984. pp. 467–520. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rippe B, Haraldsson B. Transport of macromolecules across microvascular walls: the two-pore theory. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:163–219. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Svensjö E, Arfors K-E, Raymond RM, Grega GJ. Morphological and physiological correlation of bradykinin-induced macromolecular efflux. Am J Physiol. 1979;236:H600–H6. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.4.H600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adamson RH, Huxley VH, Curry FE. Single capillary permeability to proteins having similar size but different charge. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:H304–H12. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.2.H304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Curry FE, Rutledge JC, Lenz JF. Modulation of microvessel wall charge by plasma glycoprotein orosomucoid. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:H1354–H9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.5.H1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garlick DG, Renkin EM. Transport of large molecules from plasma to interstitial fluid and lymph in dogs. Am J Physiol. 1970;219:1595–605. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.219.6.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sjöback R, Nygren J, Kubista M. Absorption and fluorescence properties of fluorescein. Spectrochim Acta A. 1995;51:L7–L21. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curry FE. Mechanics and thermodynamics of transcapillary exchange. In: Renkin EM, Michel CC, editors. Handbook of Physiology; Section 2: The Cardiovascular System. Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society; 1984. pp. 309–74. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohlson M, Sörensson J, Haraldsson B. A gel-membrane model of glomerular charge and size selectivity in series. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F396–F405. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.3.F396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schaeffer RC, Jr, Gong F, Bitrick MS, Jr, Smith TL. Thrombin and bradykinin initiate discrete endothelial solute permeability mechanisms. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:H1798–H809. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.6.H1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katz MA, Schaeffer RC., Jr Convection of macromolecules is the dominant mode of transport across horizontal 0.4- and 3-μm filters in diffusion chambers: significance for biologic monolayer permeability assessment. Microvasc Res. 1991;41:149–63. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(91)90017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Curry FE, Michel CC. A fiber matrix model of capillary permeability. Microvasc Res. 1980;20:96–9. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(80)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Engerman RL, Pfaffenbach D, Davis MD. Cell turnover of capillaries. Lab Invest. 1967;17:738–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hobson B, Denekamp J. Endothelial proliferation in tumours and normal tissues: continuous labelling studies. Br J Cancer. 1984;49:405–13. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1984.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cliff WJ. Kinetics of wound healing in rabbit ear chambers, a time lapse cinemicroscopic study. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci. 1965;50:79–89. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1965.sp001772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang S, Chen CS, Ingber DE. Control of cyclin D1, p27Kip1 and cell cycle progression in human capillary endothelial cells by cell shape and cytoskeletal tension. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:3179–93. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.11.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krebs EG. Role of the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in signal transduction. JAMA. 1989;262:1815–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.13.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Papahadjopoulos D, Poste G, Mayhew E. Cellular uptake of cyclic AMP captured within phospholipid vesicles and effect on cell-growth behaviour. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;363:404–18. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(74)90079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Papahadjopoulos D, Mayhew E, Poste G, Smith S, Vail WJ. Incorporation of lipid vesicles by mammalian cells provides a potential method for modifying cell behaviour. Nature. 1974;252:163–6. doi: 10.1038/252163a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Staub NC. Pulmonary edema due to increased microvascular permeability. Annu Rev Med. 1981;32:291–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.32.020181.001451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hargens AR, Akeson WH, Mubarak SJ, Owen CA, Gershuni DH, Garfin SR, et al. Tissue fluid pressures: from basic research tools to clinical applications. J Orthop Res. 1989;7:902–9. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100070617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Radisic M, Yang L, Boublik J, Cohen RJ, Langer R, Freed LE, et al. Medium perfusion enables engineering of compact and contractile cardiac tissue. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H507–H16. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00171.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chary SR, Jain RK. Direct measurement of interstitial convection and diffusion of albumin in normal and neoplastic tissues by fluorescence photobleaching. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5385–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cabodi M, Choi NW, Gleghorn JP, Lee CS, Bonassar LJ, Stroock AD. A microfluidic biomaterial. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13788–9. doi: 10.1021/ja054820t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kloxin AM, Kasko AM, Salinas CN, Anseth KS. Photodegradable hydrogels for dynamic tuning of physical and chemical properties. Science. 2009;324:59–63. doi: 10.1126/science.1169494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fluorescence time-lapse of an endothelial tube that was perfused with Texas Red-40kDa dextran in the absence of db-cAMP. The time between frames is one minute.