Abstract

Our laboratory studies the effects of in utero opioid exposure on the neonate. In this work we test the effects of chronic in utero exposure to buprenorphine on the neonate. Buprenorphine is a promising candidate for treatment of opioid addiction during pregnancy and it has been suggested to decrease the neonatal abstinence syndrome in human infants. In our guinea pig model, we focused not only on the respiratory effects of in utero exposure on the neonate, but also studied withdrawal signs in the neonate, a major concern of all opioid treatment during pregnancy. Pregnant guinea pigs were treated with daily subcutaneous injections of 0.1 mg/kg buprenorphine during the second half of gestation. We measured weight, locomotor activity and respiratory function in pups of ages 3 to 14 days. Respiratory response was recorded using a two-chamber plethysmograph, while pups were breathing either room air or 5% CO2. Our results show that chronic in utero exposure to buprenorphine induces respiratory effects up to day 14 after birth, while earlier studies have shown that effects of either in utero methadone or morphine only persist in the first week after birth in the guinea pig model. These data provide important information for clinical trials of buprenorphine treatment suggesting that duration and severity of respiratory effects of in utero buprenorphine exposure should be monitored.

Keywords: In utero buprenorphine, respiratory control, neonatal abstinence syndrome, development, opioids, substance abuse

1. Introduction

Currently, the only approved drug treatment in the United States for opioid dependence in pregnant women is methadone maintenance [21,43]. Even though this therapy has proven beneficial for both maternal and fetal outcome, newborns often suffer from neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) as a result [27,39,44]. The NAS symptoms caused by in utero methadone exposure include dysfunctions of the respiratory system, seizures [15], and an increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome [22,23]. Therefore alternate treatment options are sought that could improve maternal and neonatal outcome.

We have recently shown that in an animal model of chronic in utero methadone or morphine exposure, the respiratory effects of methadone on the neonate, though less severe than morphine, are still significant and potentially detrimental [33]. In addition, effects on neonatal weight and excitability, indicators for NAS, are more severe than effects of morphine. In humans these effects are offset somewhat by the socioeconomic factors associated with the treatment program, such as better medical care and nutrition [36].

Buprenorphine is one potential alternative treatment option for pregnant women. It is a long-lasting partial agonist at the mu opioid receptor that has recently been successfully introduced as an alternative treatment for opioid addiction in non-pregnant opioid addicts [4,24,37]. Preliminary studies indicate that pregnant female addicts can safely be transitioned to buprenorphine treatment and that NAS caused by in utero buprenorphine exposure may be less severe than that of methadone [11,12,17,20]. However, all these studies are hampered by confounding factors like multi-substance abuse, continued illicit drug use, insufficient medical care, or maternal neglect during and after the pregnancy. Studies using animal models are needed, as they are free of these confounding factors.

This study used the guinea pig model to evaluate the effects of chronic in utero buprenorphine exposure on the neonate. It was designed to test the hypothesis that the neonatal abstinence syndrome and respiratory depression effects of buprenorphine are less severe when compared with previously reported data on morphine and methadone in utero exposure [16,33].

Pregnant guinea pigs were treated with a once daily dose of buprenorphine during the second half of gestation. Dose selection was based on the survival of the maternal-fetal unit. Respiratory parameters of their litters have been studied in a longitudinal study during the first two weeks after birth using a non-invasive plethysmograph. We show that the respiratory effects of buprenorphine were equally as severe as those of methadone or morphine. Considering respiratory criteria alone, these data suggest that buprenorphine treatment of drug addiction during pregnancy is not more beneficial for the newborn child than methadone or morphine, as the respiratory effects persisted for two weeks after birth.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and treatment groups

All experiments were approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” guidelines. Female Dunkin-Hartley guinea pigs (6 weeks old, 300 to 400 grams) from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) were bred at Oregon Health & Science University. Pregnant guinea pigs were randomly assigned to receive a daily injection of either 1 ml/kg of 0.9% saline solution (vehicle control) or 0.1 mg/kg buprenorphine in saline. Buprenorphine injection volumes were standardized to 1 ml/kg. Subcutaneous injections in the shaved scruff of the neck started at day 35 of pregnancy prior to critical periods of in utero nervous system development in the guinea pig [10,35] and were given once daily in the morning until the day of parturition [33]. Six pups (2 litters, 3 males and 3 females) from two saline treated dams, and eight pups from three buprenorphine treated dams (3 litters, 6 males and 2 females) were included in the study. All pups from a litter were studied, but in order to avoid litter effects, data analysis was performed using the litter as the basic unit.

After parturition, dams and pups were housed together with 12 hr controlled light/dark cycles and ad libitum food and water. The first day pups were observed in the tub was defined as day 1. A longitudinal study of all pups of a litter was carried out on days 3, 7, 10, and 14.

2.2. Locomotor activity

Locomotor activity of pups was measured on study days immediately prior to respiratory measurements. A pup was separated from its mother, weighed, and placed immediately in an isolated Opto-Varimax mini activity monitor (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) for a period of 15 min. The activity monitor counted breaks of the light beams and separately recorded total movements including grooming, digging, and head movements (every beam break is recorded) and ambulatory movements (two consecutive beam breaks are recorded).

2.3. Ventilatory and metabolic measurements

Ventilatory and metabolic data were collected using the same protocol as in previous studies in our laboratory [16,33]. Pups were placed in a non-invasive, head-out, two-chamber plethysmograph [35] (Buxco Electronics, Sharon, CT) for a 10 min acclimation period. Interchangeable head chambers allowed separate inspiration of the two study gases; “Room Air”, (RA; 21% O2, balance N2) and “5% CO2” (5% CO2, 30% O2, balance N2). Therefore both room air and hypercapnic respiratory response could be measured in unanesthesized, unintubated and only slightly restrained pups [3]. First, room air data were collected with a steady flow of RA (1 L·min−1) for 10 min, after which the head chamber was quickly changed and the 5% CO2 gas mixture (1.7 L·min−1) was administered for 5 min to measure the hypercapnic response. Metabolic parameters were only measured during RA flow by sampling the head chamber over 30 sec periods. Both oxygen consumption (VO2; ml·min−1·100g−1) and CO2 production (VCO2; ml·min−1·100g−1) were measured and VI/VO2 and VI/VCO2 were calculated (Oxymax software version 2.4.2, Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). From the separate body chamber animal breathing movements were recorded and averaged over 1 min periods. Directly measured parameters were breathing frequency (fR; breaths·min−1), inspiratory time (TI; sec), expiratory time (TE; sec), and respiratory air flow (ml·sec−1), which were used to calculate tidal volume (VT; ml·100g−1), inspiratory minute ventilation (VI; ml·min−1·100g−1), and inspiratory effort (VT/TI; ml·sec−1·100g−1) using BioSystem XA software version 2.7.9 (Buxco Electronics, Sharon, CT).

2.4. Data analysis and statistics

Gestational length was defined as the number of days from the first day of vaginal opening to the day pups were observed in the tub. Maternal weight gain was monitored daily and weight recorded on the day before pups were born was reported as maternal weight at parturition. All pups of a litter were studied and averaged to avoid litter effects. Previous studies in the guinea pig in our group as well as clinical observations have shown that respiratory effects of opioids are not sex dependent [5,30,32], therefore both male and female pups were studied and data was collapsed for gender.

Respiratory data of all pups were collected on days 3, 7, 10, and 14 after birth as previously described [33]. In brief, during the 10 min RA breathing period, metabolic parameters were measured for the first 6 min and breathing movements for the remaining 4 min. During the 5 min CO2 challenge, only breathing movements were measured. In order to ensure a steady-state had been reached, the data reported and analyzed are the averages of the last two minutes of each measurement period. All values are reported as the mean ± standard error.

Significant statistical differences for gestational length, maternal weight, and maternal weight gain were determined using the Student’s t-test with treatment as factor (SigmaStat version 3.11, SysStat Software Inc., Richmond, CA). All neonate data were averaged for each litter and were analyzed by two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with factors of age and treatment. An overall P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant and all post-hoc comparisons were performed using the Holm-Sidak method. Weight data for all litters was analyzed using litter size as a covariant (SPSS, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

3. Results

3.1. Effects of chronic in utero buprenorphine treatment on the dam and pup weight

The buprenorphine dose of 0.1 mg/kg used in these experiments was determined in pilot studies as the maximum tolerable dose for the maternal-fetal unit with no fatal outcome seen for either dams or pups. In the pilot study, four dams had been tested with buprenorphine doses of 0.2 (2 dams), 0.5, and 1.0 mg/kg. The treatment with the two highest doses resulted in unacceptable weight loss of the dams and had to be terminated. The 0.2 mg/ml dose resulted in premature still birth on day 49 and 57, respectively. Table 1 shows the maternal weight data recorded during gestation. Treatment groups were not different in the first half of gestation. Buprenorphine treatment during the second half of gestation caused significantly lower weight gain and resulted in lower maternal weight at parturition. All three dams treated with 0.1 mg/kg of buprenorphine gave birth to live, full term litters.

Table 1.

Weight data of dams and pups: Pregnant guinea pigs were treated once daily with vehicle (saline), or buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg) starting at day 35 of gestation. Maternal weight during gestation and pup weight at days of respiratory testing was recorded. Buprenorphine treatment affected both maternal weight gain during the injection period and pup weight during the first two weeks of life, but did not affect the relative weight gain of the pups. Data from vehicle treated dams and pups were not different from previous studies. All values are mean ± SE.

| Vehicle | Buprenorphine | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal weight [g] | Gestation start | 463 ± 59 | 420 ± 16 |

| Parturition | 1046 ± 75 | 795 ± 18* | |

| Weight gain [%] | Day 1 – day 35 | 54 ± 16 | 56 ± 6 |

| Day 35 - parturition | 49 ± 7 | 22 ± 2* | |

| N (dams) | 2 | 3 | |

| Pup weight [g] | Birth (day 1) | 108 ± 15 | 87 ± 5* |

| Day 3 | 103 ± 12 | 83 ± 8* | |

| Day 7 | 130 ± 20 | 102 ± 12* | |

| Day 10 | 155 ± 26 | 125 ± 15* | |

| Day 14 | 193 ± 31 | 157 ± 17* | |

| Weight gain [% of birth weight] | Day 3 | −4 ± 12 | −4 ± 9 |

| Day 7 | 21 ± 18 | 18 ± 15 | |

| Day 10 | 35 ± 6 | 43 ± 17 | |

| Day 14 | 80 ± 29 | 80 ± 19 | |

| N (litter) | 2 | 3 |

p<0.05 vs. vehicle

Pup weight was recorded on the day pups were first observed in the tub (day 1) and on all days respiratory measurements were taken. Weight of in utero buprenorphine exposed pups was significantly lower on all days than the weight of the saline exposed control group. The relative weight gain of pups compared to their birth weight was not different between treatment groups (Table 1).

3.2. Effects of chronic in utero buprenorphine treatment on pup activity

Immediately before respiratory measurements were recorded, pups were removed from their moms and their activity was monitored in an isolated locomotor chamber (Table 2). Buprenorphine exposed pups showed withdrawal related hyperactivity only on day 3 compared to control animals, while older pups had no statistically significant hyperactivity.

Table 2.

Activity data of pups: Pups were removed from their moms on days of respiratory testing for a period of 15 min and their ambulatory as well as grooming and digging movements were monitored. Buprenorphine treated pups show withdrawal related hyperactivity only on day 3. All values are mean ± SE.

| 3 day | 7 day | 10 day | 14 day | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total activity [counts] | Vehicle | 313 ± 9 | 311 ± 3 | 236 ± 20 | 420 ± 113 |

| Buprenorphine | 1696 ± 354***abc | 601 ± 33 | 422 ± 89 | 479 ± 98 | |

| Ambulatory activity [counts] | Vehicle | 146 ± 24 | 168 ± 14 | 81 ± 8 | 214 ± 100 |

| Buprenorphine | 1376 ± 308***abc | 358 ± 30 | 228 ± 93 | 253 ± 68 | |

| Activity ratio [% ambulatory/total] | Vehicle | 43 ± 5 | 50 ± 1 | 35 ± 6 | 48 ± 11 |

| Buprenorphine | 79 ± 2***abc | 59 ± 2 | 47 ± 11 | 51 ± 4 |

p<0.001 vs. vehicle,

p<0.05 vs. 7, 10, and 14 day same treatment, (n = 6 for vehicle, n = 8 for buprenorphine)

3.3. Respiratory measurements

3.3.1. Inspiratory minute ventilation and tidal volume

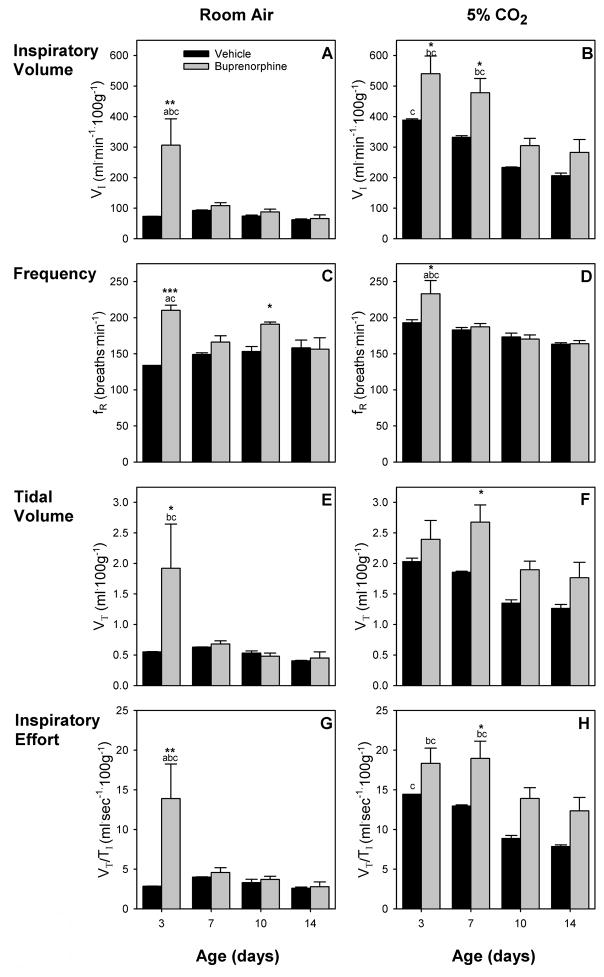

For VI, there was a main effect for age (F (3,9) = 4.03, p < 0.05), and an age-drug interaction (F (3,9) = 3.97, p < 0.05) during RA breathing (Fig. 1A). There were no main effects for VT (Fig 1E). While VI and VT of saline exposed pups did not change with age, both were drastically elevated in 3 day old buprenorphine pups, indicating withdrawal related hyperventilation even under rest conditions. This increase was not seen in older pups. During 5% CO2 challenge, there was a main effect for age (F (3,9) = 22.46, p < 0.001 and F (3,9) = 6.53, p < 0.05, respectively) for both VI and VT (Fig. 1B, F). In contrast to RA breathing VI decreased between week 1 (days 3 and 7) and week 2 (days 10 and 14) for the buprenorphine treatment group. For saline pups VI of the youngest pups (day 3) was greater than VI of the oldest pups (day 14). Similar trends were seen for VT, but these decreases were not statistically significant. In addition, buprenorphine exposed pups had a significantly increased VI up to day 7, while it was slightly increased during week 2. VT of the buprenorphine treated pups was slightly increased on all days and significantly increased on day 7 compared to the control group. This indicates that respiratory related withdrawal symptoms are present longer under hypercapnic conditions.

Figure 1.

Respiratory effects of in utero buprenorphine treatment (gray bars) were compared to vehicle (black bars) during room air (RA) breathing (left) and during 5% CO2 challenge (right). Major respiratory parameters, inspiratory minute ventilation (VI) (A, B), breathing frequency (fR) (C, D), tidal volume (VT) (E, F), and inspiratory effort (VT/TI) (G, H) are shown. Several differences exist between buprenorphine and saline exposed pups. Differences are greatest in the youngest animals and during CO2 challenge. Vertical bars represent standard error (S.E.). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. vehicle; a p < 0.05 vs. 7-day same treatment; b p < 0.05 vs. 10-day same treatment; c p < 0.05 vs. 14-day same treatment.

3.3.2. Breathing frequency

For fR there was a main effect for drug (F (1,9) = 66.84, p < 0.01) and an age-drug interaction (F (3,9) = 4.96, p < 0.05) during RA breathing (Fig. 1C). There were no changes in fR for control pups with age. On day 3, buprenorphine exposed pups had a greater fR than control pups of the same age and 7 and 14 day old buprenorphine pups. Breathing frequency was also elevated on day 10 compared to older buprenorphine pups and control pups of the same age. During 5% CO2 challenge, there was a main effect for age (F (3,9) = 19.59, p < 0.001) and an age-drug interaction (F (3,9) = 4.20, p < 0.05) (Fig. 1D). No age effect was seen for control pups. In contrast, 3 day old buprenorphine pups had significantly elevated fR compared to control pups and older buprenorphine pups. In older pups, fR was not different from control pups.

3.3.3. Inspiratory effort

During RA breathing (Fig. 1G), three day old buprenorphine treated pups had a drastically increased inspiratory effort compared to control pups as well as compared to older pups of the same treatment. There were no age effects for saline treated pups. During 5% CO2 challenge, there was a main effect for age (F (3,9) = 14.65, p < 0.001). The inspiratory effort of buprenorphine exposed pups was significantly increased on day 7, but elevated compared to control on all four test days (Fig 1H). For both treatment groups, the inspiratory effort was higher in the first week (days 3 and 7) than in the second week (days 10 and 14) for buprenorphine treated pups.

3.3.4. Inspiratory and expiratory time

There was a main effect for drug for both TI and TE (F (1,9) = 63.62, p < 0.01, and F (1,9) = 12.41, p < 0.05, respectively) during RA breathing (Table 3). Both parameters were lower in 3 and 10 day old buprenorphine treated pups compared to vehicle. In addition, TE of 3 day old buprenorphine pups was lower compared to 14 day old pups in the same treatment group. During 5% CO2 challenge, there was a main effect- for age (F (3,9) = 116.18, p < 0.001), and an age- drug interaction for TE (F (3,9) = 29.61, p < 0.001). TI of buprenorphine pups was not different from control pups and showed no changes with age. In contrast, TE of buprenorphine exposed pups increased during the first 10 days, while control pups had no age related effects. Comparison of both treatment groups showed that TE of buprenorphine pups is smaller in 3 day old, identical in 7 day old, and greater than control in 10 and 14 day old pups.

Table 3.

Respiratory measurements of inspiratory and expiratory time of in utero buprenorphine exposed neonatal guinea pigs.

| Age | Room Air | 5% CO2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | Buprenorphine | Vehicle | Buprenorphine | ||||||

| TI [sec] | 3 days | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.01 |

| .20 | .13** | .14 | 0 | .13 | |||||

| 7 days | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| .17 | .16 | .14 | 0 | .14 | |||||

| 10 days | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.01 | |

| .17 | .13* | .15 | 0 | .14 | |||||

| 14 days | 0 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| .16 | .16 | .16 | 1 | .14 | |||||

| TE [sec] | 3 days | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.01* |

| .26 | .18**c | .17 | 0abc | .13*abc | |||||

| 7 days | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.00b | |

| .25 | .23 | .19 | 0 | .19c | |||||

| 10 days | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.01* | |

| .25 | .20* | .20 | 1 | .23 | |||||

| 14 days | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.00* | |

| .25 | .26 | .21 | 0 | .23 | |||||

| TE/TI | 3 days | 1 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0** |

| .3 | .4 | .2 | .0abc | ||||||

| 7 days | 1 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0bc | |

| .5 | .5 | .3 | .4 | ||||||

| 10 days | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1** | |

| .5 | .5 | .3 | .7* | ||||||

| 14 days | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0** | |

| .5 | .6 | .3 | .6* | ||||||

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001 vs. vehicle;

p<0.05 vs. 7,10, or 14 day same treatment.

All values are reported as mean ± S.E.

The ratio of expiratory to inspiratory time (TE/TI) was different between treatment groups only under 5% CO2 challenge (Table 3). There were main effects for age (F (3,9) = 30.53, p < 0.001) and drug (F (1,9) = 15.18, p < 0.05), and an age-drug interaction (F (3,9) = 21.13, p < 0.001). Like the TE of buprenorphine pups during 5% CO2 challenge, the ratio of TE/TI was smaller for 3 day old pups and identical on day 7, while it was higher in these pups compared to control in the second week of testing.

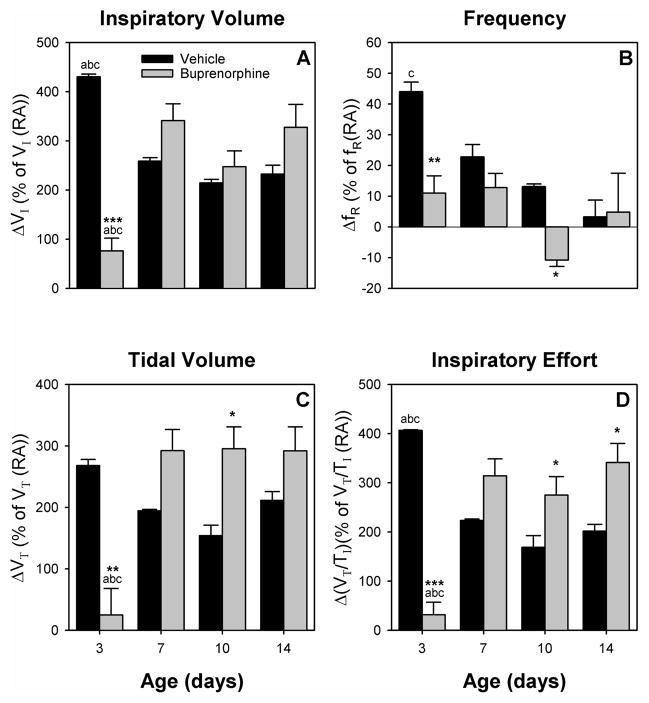

3.3.5. Comparison of room air breathing and CO2 challenge

Fig. 2 shows the delta response from room air breathing to 5% CO2 challenge. For ΔVI, ΔVT and ΔVT/TI (Fig 2A, C, D), there was an age-drug interaction (F (3,9) = 19.88, p < 0.001, F (3,9) = 9.88, p < 0.01, and F (3,9) = 27.19, p < 0.001, respectively). For ΔfR (Fig 2B), there was a main effect of age (F (3,9) = 6.85, p < 0.05). The delta response for all four parameters was drastically decreased for buprenorphine exposed animals on day 3, due to the increase of all parameters during normal RA breathing (see above). In contrast, ΔVT had a tendency to be increased on day 7 (p = 0.08) and was increased on day 10; plus ΔVT/TI was increased on day 10 and 14 compared to control animals. In addition, ΔVI showed a tendency to be increased on day 7 (p = 0.1) and 14 (p = 0.06). Also, ΔfR on day 10 was different from control due to a negative ΔfR response on this day for all test animals, while ΔfR was not different from control on days 7 and 14.

Figure 2.

Delta response for buprenorphine (gray bars) and vehicle (black bars) treated pups was calculated as the percent change from RA breathing to CO2 challenge compared to the mean for all litters of the same age and treatment group during RA breathing. ΔVI (A), ΔfR (B), ΔVT (C), and ΔVT/TI (D) are graphed. The delta response is vastly decreased for all parameters in the youngest animals, while it is increased in older animals (ΔVT, and ΔVT/TI). Vertical bars represent standard error (S.E.). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. vehicle; a p < 0.05 vs. 7-day same treatment; b p < 0.05 vs. 10-day same treatment; c p < 0.05 vs. 14-day same treatment.

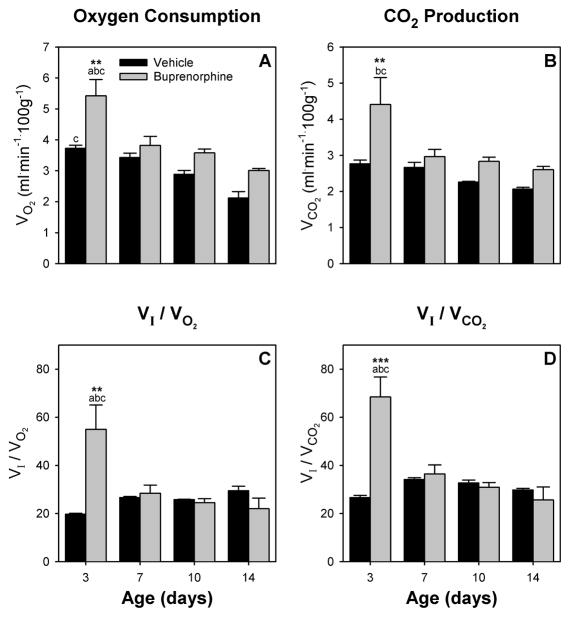

3.4. Metabolic measurements

3.4.1. Oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2)

There were main effects of age (F (3,9) = 14.83, p < 0.001 and F (3,9) = 4.25, p < 0.05, respectively) and drug (F (1,9) = 29.29, p < 0.05 and F (1,9) = 12.05, p < 0.05) for both VO2 and VCO2 (Fig 3). VO2 for control animals decreased during the two weeks of testing and was different between day 3 and day 14, while for buprenorphine treated pups VO2 was strongly increased on day 3 and lowest on day 14 (Fig 3A). Buprenorphine treatment significantly increased oxygen consumption on day 3 compared to control. Similarly, on day 3, buprenorphine pups had a strongly increased CO2 production compared to control pups as well as older buprenorphine exposed pups (Fig 3B). In contrast to VO2 though, there were no age related effects for control pups for VCO2.

Figure 3.

Effects on oxygen metabolism of in utero buprenorphine treatment (gray bars) were compared to vehicle (black bars). Oxygen consumption VO2 (A), CO2 production VCO2 (B), VI/VO2 (C), and VI/VCO2 (D) are graphed for all test days. Differences between treatment groups are greatest in 3 day old pups, indicating withdrawal related hyperventilation in buprenorphine exposed pups. Vertical bars represent standard error (S.E). ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. vehicle; a p < 0.05 vs. 7-day same treatment; b p < 0.05 vs. 10-day same treatment; c p < 0.05 vs. 14-day same treatment.

3.4.2. VI/VO2 and VI/VCO2

For both parameters, VI/VO2 and VI/VCO2 there was an age-drug interaction (F (3,9) = 7.38, p < 0.01 and F (3,9) = 11.64, p < 0.01, respectively). In addition, there was a main effect for age for VI/VCO2 (F (3,9) = 7.24, p < 0.01). Both parameters indicate a strong hyperventilation of buprenorphine treated pups on day 3 (Fig 3C, D) compared to control pups. This was not seen in 7 day or older pups of both treatment groups.

4. Discussion

Over the years we have reported on the effects of in utero exposure to different drugs of abuse or drugs used to treat drug abuse during gestation [16,28,33,35]. The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of chronic in utero buprenorphine exposure on the neonatal guinea pig. Buprenorphine was studied in an animal model free of confounding factors because it is a promising candidate drug for substitution of the current standard methadone maintenance treatment program during pregnancy [11,12,17,20]. The present study focuses on respiratory effects associated with buprenorphine, but it also presents data on parameters associated with neonatal abstinence syndrome. To our knowledge, this is the first in utero buprenorphine study in the guinea pig.

In order to determine the dose for in utero buprenorphine exposure, we preformed preliminary studies based on previous literature on buprenorphine in the adult guinea pig model [6,14]. Similar to previous in utero studies for different opioids in both the rat and the guinea pig [33,42], we chose to study the highest tolerable dose for the maternal-fetal unit. The treatment schedule was based on our previous studies with methadone [33], as well as on clinical treatment programs for buprenorphine where buprenorphine is given once a day or every other day [4]. Data presented here show that in utero buprenorphine exposure affects both maternal weight gain and pup weight at birth and during the first two weeks of life. These results are similar to a study of in utero buprenorphine exposure in rats that showed reduction in pup weight that was comparable to that of methadone treated pups [38]. In addition, we used withdrawal induced hyperactivity in pups as a measure of NAS. We found extreme hyperactivity in 3 day old pups when removed from the moms, but not in older animals, suggesting that immediate withdrawal symptoms are only present in the youngest animals. This increase is comparable to the one we have seen in a previous study with methadone, while both are greater than for morphine [33]. In human infants, the score for NAS for infants born to mothers in buprenorphine treatment is better [20] or equal [26] in most cases compared to methadone maintained infants, while both are less severe than for morphine exposed infants [29].

Respiratory effects of in utero buprenorphine are seen during the immediate withdrawal period on day 3 and continue for the first two weeks of life. In the youngest pups, we have seen a substantial increase in inspiratory effort for buprenorphine treated pups, both under normcapnic and hypercapnic conditions. This is accompanied by extreme hyperventilation in these animals, due to increased inspiratory minute ventilation that is above and beyond any increase in oxygen consumption or carbon dioxide production. On the following study days, there is a continued increase in the delta effect of the inspiratory effort in response to CO2 inhalation. Furthermore, expiratory time and the ratio of expiratory to inspiratory time is altered in buprenorphine pups up to the last study day. This suggests an abnormal neuro-control of breathing during the acute withdrawal period in buprenorphine exposed pups. Furthermore, buprenorphine causes a prolonged and exaggerated response to hypercapnia beyond this initial withdrawal period, which implies an abnormal control of breathing in the central nervous system [25,40].

Previous studies have shown that there is an increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) associated with the respiratory effects caused by in utero methadone [22,23], morphine [34], or buprenorphine [19]. The data reported here suggest that the risk of SIDS for the neonate exposed to buprenorphine treatment during pregnancy may be as likely or frequent as for methadone maintained or morphine abusing moms. Furthermore, the increased risk factors might be manifested for a long time after birth. Reasons for these prolonged effects are unclear. Moms were not given any drug after parturition in this study. We did not measure drug levels in the mom or the pup during our studies. Previous studies though have shown that the placental transfer of buprenorphine to the fetal circuit is low [31], but have also indicated that due to the high lipophilicity of buprenorphine [13] it may be retained longer [38]. Furthermore, buprenorphine exhibits slower pharmacokinetics and metabolism in infants compared to adults [1]. Prenatal buprenorphine exposure in the rat also down-regulates mu opioid binding in the brain [2] and potentially affects respiratory control this way. Independent of the mechanism through which buprenorphine causes these prolonged effects in the neonate, our results indicate a need for longer and careful supervision of offspring of buprenorphine treated moms.

We saw no reduction in the level of respiratory effects for buprenorphine in the neonate when comparing our studies side by side with our recent study on methadone and morphine [33]. In contrast, the comparison shows that buprenorphine induced respiratory effects tend to be more severe in the immediate withdrawal phase as they are more apparent under normcapnia and are still apparent and measurable for several parameters during a hypercapnic challenge during the second week of life. Both of which was not seen for methadone in our earlier study, and only seen for morphine during normcapnia in the youngest animals [33]. Several studies have shown that, because buprenorphine is a partial agonist, respiratory effects of increasing doses exhibit a ceiling effect; while analgesic effects do not [8,9]. Therefore, we expected to see less respiratory effects with buprenorphine treatment, but this has not been seen when we compare equally effective in utero opioid drug doses. This could be due to the relative low dose of buprenorphine used; however, the dose of buprenorphine used had similar effects on the pregnant dam as the doses of methadone and morphine that we are comparing it to, and was the maximal dose tolerated by the maternal-fetal unit.

Currently, buprenorphine is only approved for treatment of opioid addiction in non-pregnant populations [7,41]. Nevertheless, it is increasingly prescribed to pregnant patients, even though studies examining the safety and risks of prenatal exposure to buprenorphine are currently in progress and still incomplete [18,20]. Therefore, it is more and more important to gather data on the effects of in utero buprenorphine on the newborn infant. The importance of the data reported here is that there may be considerable risks involved with transferring pregnant females from methadone to buprenorphine maintenance treatment, especially with regard to the consequences for the respiratory control of the newborn. Overall the switch from methadone to buprenorphine might be beneficial for both the mom and the child due to the socioeconomic factors of the treatment change [36], but our data clearly demonstrate that the risks involved with buprenorphine maintenance treatment are significant and need to be monitored carefully.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Daniel A. N. Silverman for careful review of the manuscript and Katherine B. Spencer for help with the statistical analysis. Chinmayee V. Subban was awarded a Murdock Charitable Trust Fellowship. This research was funded by The National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant 07912, G.D.O). The National Institute on Drug Abuse also provided the buprenorphine used in this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors and author’s institution have no financial or other relationships with other people or organizations that would constitute a conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barrett DA, Simpson J, Rutter N, Kurihara-Bergstrom T, Shaw PN, Davis SS. The pharmacokinetics and physiological effects of buprenorphine infusion in premature neonates. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;36:215–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb04220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belcheva MM, Bohn LM, Ho MT, Johnson FE, Yanai J, Barron S, Coscia CJ. Brain opioid receptor adaptation and expression after prenatal exposure to buprenorphine. Developmental Brain Research. 1998;111:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blake CI, Banchero N. Ventilation and oxygen consumption in the guinea pig. Respir Physiol. 1985;61:347–355. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(85)90077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boothby LA, Doering PL. Buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid dependence. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:266–272. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cepeda MS, Farrar JT, Baumgarten M, Boston R, Carr DB, Strom BL. Side effects of opioids during short-term administration: effect of age, gender, and race. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74:102–112. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cichewicz DL, Welch SP, Smith FL. Enhancement of transdermal fentanyl and buprenorphine antinociception by transdermal delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;525:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins GB, McAllister MS. Buprenorphine maintenance: a new treatment for opioid dependence. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74:514–520. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.74.7.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahan A, Yassen A, Bijl H, Romberg R, Sarton E, Teppema L, Olofsen E, Danhof M. Comparison of the respiratory effects of intravenous buprenorphine and fentanyl in humans and rats. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:825–834. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahan A, Yassen A, Romberg R, Sarton E, Teppema L, Olofsen E, Danhof M. Buprenorphine induces ceiling in respiratory depression but not in analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:627–632. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawes GS. The Establishment of Pulmonary Respiration. In: Dawes GS, editor. Foetal And Neonatal Physiology: A comparative Study of the Changes at Birth. Year Book Medical Publishers, Inc; Chicago, IL: 1968. pp. 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebner N, Rohrmeister K, Winklbaur B, Baewert A, Jagsch R, Peternell A, Thau K, Fischer G. Management of neonatal abstinence syndrome in neonates born to opioid maintained women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer G, Ortner R, Rohrmeister K, Jagsch R, Baewert A, Langer M, Aschauer H. Methadone versus buprenorphine in pregnant addicts: a double-blind, double-dummy comparison study. Addiction. 2006;101:275–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hambrook JM, Rance MJ. The interaction of buprenorphine with the opiate receptor: lipophilicity as a determining factor in drug-receptor kinetics. In: Kosterlitz HW, editor. Opiates and Endogenous Opioid Peptides. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1976. pp. 295–301. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanson CE, Ruble GR, Essiet I, Hartman AB. Effects of buprenorphine on immunogenicity and protective efficacy in the guinea pig keratoconjunctivitis model (Sereny test) Comp Med. 2001;51:224–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huestis MA, Choo RE. Drug abuse’ smallest victims: in utero drug exposure. Forensic Sci Int. 2002;128:20–30. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(02)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter MA, Vangelisti GR, Olsen GD. Chronic intermittent in utero exposure to morphine: effects on respiratory control in the neonatal guinea pig. Biol Neonate. 1997;72:293–304. doi: 10.1159/000244496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones HE, Johnson RE, Jasinski DR, O’rady KE, Chisholm CA, Choo RE, Crocetti M, Dudas R, Harrow C, Huestis MA, Jansson LM, Lantz M, Lester BM, Milio L. Buprenorphine versus methadone in the treatment of pregnant opioid-dependent patients: effects on the neonatal abstinence syndrome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones HE, Martin PR, Heil SH, Kaltenbach K, Selby P, Coyle MG, Stine SM, O’rady KE, Arria AM, Fischer G. Treatment of opioid-dependent pregnant women: Clinical and research issues. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35:245–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahila H, Saisto T, Kivitie-Kallio S, Haukkamaa M, Halmesmaki E. A prospective study on buprenorphine use during pregnancy: effects on maternal and neonatal outcome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:185–190. doi: 10.1080/00016340601110770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kakko J, Heilig M, Sarman I. Buprenorphine and methadone treatment of opiate dependence during pregnancy: Comparison of fetal growth and neonatal outcomes in two consecutive case series. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaltenbach K, Berghella V, Finnegan L. Opioid dependence during pregnancy. Effects and management. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1998;25:139–151. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(05)70362-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kandall SR, Gaines J. Maternal substance use and subsequent sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) in offspring. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1991;13:235–240. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(91)90016-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandall SR, Gaines J, Habel L, Davidson G, Jessop D. Relationship of maternal substance abuse to subsequent sudden infant death syndrome in offspring. J Pediatr. 1993;123:120–126. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81554-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleber HD. Pharmacologic treatments for heroin and cocaine dependence. Am J Addict. 2003;12(Suppl 2):S5–S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lalley PM. Opioidergic and dopaminergic modulation of respiration. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;164:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lejeune C, Simmat-Durand L, Gourarier L, Aubisson S. Prospective multicenter observational study of 260 infants born to 259 opiate-dependent mothers on methadone or high-dose buprenorphine substitution. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lesser-Katz M. Some effects of maternal drug addiction on the neonate. Int J Addict. 1982;17:887–896. doi: 10.3109/10826088209056335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuda AY, Olsen GD. Chronic in utero morphine exposure alters mu-agonist-stimulated [35S]-GTPgammaS binding in neonatal and juvenile guinea pig brainstem regions associated with breathing control. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2001;23:413–419. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(01)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minozzi S, Amato L, Vecchi S, Davoli M. Maintenance agonist treatments for opiate dependent pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD006318. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006318.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphey LJ, Olsen GD. Morphine-6-beta-D-glucuronide respiratory pharmacodynamics in the neonatal guinea pig. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;268:110–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nanovskaya T, Deshmukh S, Brooks M, Ahmed MS. Transplacental transfer and metabolism of buprenorphine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:26–33. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nettleton RT, Ransom TA, Abraham SL, Nelson CS, Olsen GD. Methadone-induced respiratory depression in the neonatal guinea pig. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:1134–1143. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nettleton RT, Wallisch M, Olsen GD. Respiratory effects of chronic in utero methadone or morphine exposure in the neonatal guinea pig. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2008;30:448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2008.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olsen GD, Murphey LJ. Effects of morphine and cocaine on breathing control in neonatal animals: a minireview. NIDA Res Monogr. 1995;158:22–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsen GD, Weil JA. In utero cocaine exposure: effect on neonatal breathing in guinea pigs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;261:420–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pritham UA, Troese M, Stetson A. Methadone & Buprenorphine Treatment During Pregnancy: What are the Effects on Infants? Nurs Womens Health. 2007;11:558–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-486X.2007.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson SE. Buprenorphine: an analgesic with an expanding role in the treatment of opioid addiction. CNS Drug Rev. 2002;8:377–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2002.tb00235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robinson SE, Wallace MJ. Effect of perinatal buprenorphine exposure on development in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:797–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serane VT, Kurian O. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 2008;75:911–914. doi: 10.1007/s12098-008-0107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shook JE, Watkins WD, Camporesi EM. Differential roles of opioid receptors in respiration, respiratory disease, and opiate-induced respiratory depression. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:895–909. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.4.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stock C, Shum JH. Buprenorphine:a new pharmacotherapy for opioid addictions treatment. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2004;18:35–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tiong GK, Olley JE. Effects of exposure in utero to methadone and buprenorphine on enkephalin levels in the developing rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1988;93:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang EC. Methadone treatment during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1999;28:615–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1999.tb02170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ziegler M, Poustka F, von Loewenich V, Englert E. Postpartum risk factors in the development of children born to opiate-addicted mothers; comparison between mothers with and without methadone substitution. Nervenarzt. 2000;71:730–736. doi: 10.1007/s001150050657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]