Abstract

The retina is subject to degenerative diseases that often lead to significant visual impairment. Non-mammalian vertebrates have a remarkable ability to replace neurons lost through damage. Fish, and to a limited extent birds, replace lost neurons by de-differentiation of Müller glia to a progenitor state followed by replication of these neuronal progenitor cells. Over the past five years, studies have investigated whether regeneration can be stimulated in the mouse and rat retina. Several groups have reported that at least some types of neurons can be regenerated in the mammalian retina in vivo or in vitro, and that the regeneration of neurons can be stimulated using growth factors, transcription factors or subtoxic levels of excitatory amino acids. These recent results suggest that some part of the regenerative program that occurs in non-mammalian vertebrates remains in the mammalian retina, and may provide a basis to develop new strategies for retinal repair in patients with retinal degenerations.

Introduction

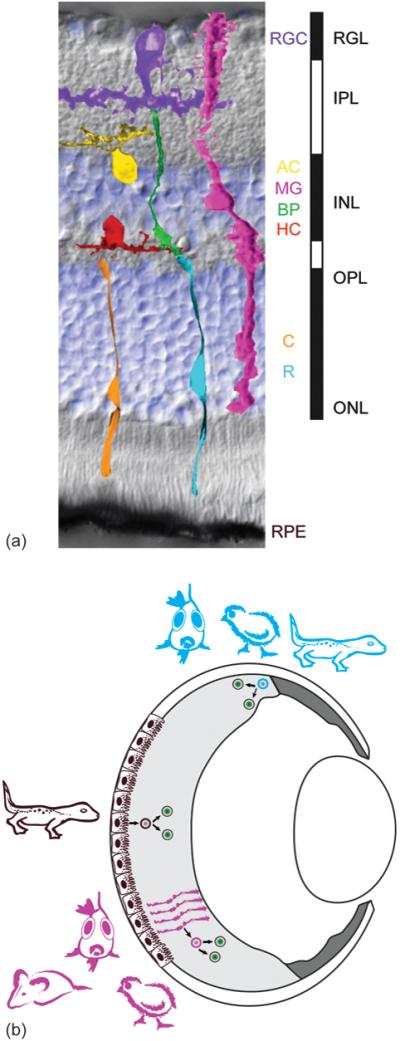

The retina is a complex neural circuit responsible for transducing light into a pattern of electrical impulses that informs the brain about the visual world. The retina has a common architecture across non- and mammalian species with six classes of neurons, including two types of light sensitive cells: cones (daytime color vision) and rods (low light sensors). Photoreceptor signals are processed through three types of interneurons: horizontal cells, bipolar cells and amacrine cells. The cell bodies of these neurons, along with Müller glia (BOX 1) are located in the inner nuclear layer (INL). In the outer plexiform layer (OPL) the synaptic terminals of rods and cones connect with horizontal cells and bipolar cells. These two cell types modify the incoming signals and then relay them to the dendrites of the amacrine and ganglion cells via synapses in the inner plexiform layer (IPL). The amacrine cells further process the incoming signals (eg. motion detection), while the ganglion cells relay the visual information to the brain via their axons in the optic nerve (Figure 1a).

BOX 1.

Müller glia

Glia (meaning “glue” in Greek) are found in all parts of the central nervous system (CNS). Throughout the CNS glia cells have various physiological functions, including ion homeostasis, neuromodulation, adult neurogenesis and contributions to the blood-brain barrier and the immune system. In the mammalian retina, macroglia (Müller glia and astrocytes) and microglia have been identified.

Müller glia are the major retinal glial cell type and are the only one derived from the retinal neuroepithelium. Besides being the source of neuronal regeneration in some animals Müller glia span the retina radially and their processes surround the neurons (a single glia supports more than 15 neurons), and form the inner and outer limiting membranes. Müller Glia maintain the homeostasis of the retinal extracellular milieu and the synthesis, release, signaling and uptake of major mediators of synaptic function; glia derived trophic factors are important for survival of retinal neurons and for neuronal circuit formation [31, 57-60].

Müller glia also play important roles in the response to retinal damage or disease. Pathological conditions, including inherited retinal dystrophies, glaucoma and retinal detachment, lead to changes in Müller glia analogous to the response of astrocytes to injury in other regions of the CNS (see BOX2 on gliosis).

Figure 1.

(a) Vertebrate retinas share a common architecture. 7 major cell types, 5 neuronal and 2 supporting, are regularly spaced across the retina. The background of the figure is an image (Nomarski contrast) of a mouse retinal cross section counterstained with a nuclear dye (DAPI in blue) showing the laminar structure: the inner and outer nuclear layer (INL and ONL) as well as the retinal ganglion cell layer (RGL) contain most of the cells (blue). The inner and outer plexiform layer (IPL and OPL) are made up of the axons and dendrites of the neurons. Light first crosses all layers to be detected by the light sensitive photoreceptor cells, rods (R, low light level sensors) and cones (C, daylight color sensors). If cones detect a change in light intensity they signal through different bipolar cells subtypes (BC) to the retinal ganglion cells (RGC), which send their axons in the optic nerve to the higher visual centers in the brain. Rod signals are relayed via rod bipolars, amacrine (AC) neurons, and/or cone bipolars to the ganglion cells. The rod and cone pathways are modified by inhibitory neurons, at the photoreceptor-bipolar synapse by horizontal cells (HC) and at the bipolar-ganglion synapse by amacrines. The retina also contains 3 major types of support cells: 1. the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), 2. the Müller glia (MG) and 3. The astrocytes (not shown).

(b) Depending on the species retinas may regenerate from two major cell sources, RPE and Müller glia, and may even have an active stem cell zone, the ciliary marginal zone (CMZ), analogous to stem cell zones like the subventricular zone of the brain. Progenitor cells (blue) in amphibian and fish CMZ generate most of the mature retina, but only a small part in birds. The CMZ can persist throughout the animal’s life and respond to injury with increased neurogenesis. In mammals no significant persistent neurogenic CMZ has been found. Upon damage of the central retina in amphibians, the RPE cells (brown) de-differentiate, proliferate and regenerate neurons; in fish and to a limited extent in birds and rodents, retinal damage causes Müller glia (magenta) to de-differentiate, proliferate and regenerate neurons (see Figure 3).

Like other areas of the nervous system, the retina is subject to many acquired and inherited neuronal degenerative diseases. Since the retina provides the input for all visual sensory information to the brain, the loss of cells results in visual impairment and potentially complete blindness. Many retinal degenerative diseases affect only a subset of the retinal cells, although, frequently in more advanced disease, loss and reorganization of the entire retina can occur [1, 2]. In humans there appears to be little or no recovery of lost cells. By contrast, non-mammalian vertebrates, like amphibians and fish, have robust regenerative responses to injury, which can lead to near complete restoration of the neurons lost through the injury. Studies of the response to injury over many years have led to strategies for potentially stimulating these processes in the mammalian retina.

Here, we review the current status of progress in our understanding of regeneration in non-mammalian vertebrates and how these have impacted recent attempts to promote regeneration in mammals, particularly mice and rats. Further, based on current progress and questions in the field of regenerative medicine, we will discuss new avenues for the application of embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent cells in the development of cell based therapies for retinal diseases.

One area that we will not review, however, is the retinal stem cell zone at the anterior margin of the retina, which is the so-called ciliary margin zone (CMZ) or circumferential germinal zone (CGZ), which exists in fish, amphibians and birds, and allows new retina to be added as the eye grows along with the rest of the animal throughout its entire life (Figure 1b). This region does not really play much of a role in the regeneration of the majority of the retina in any species [3], although it is stimulated to produce retinal neurons by damage of the central or peripheral retina. In addition, the fact that this zone exists in non-mammalian vertebrates has led many to search for it in mammals, including humans, and there have been many claims that retinal stem cells exist and can be propagated in vitro [4]. However, these results are controversial [5] and, as this region is not crucial for most retinal regeneration in vertebrates, we will confine our review to those sources demonstrated to play more essential roles in this process. Nevertheless, there is interesting biology in the CMZ, and the reader is referred to other reviews on this interesting area of the retina [6, 7].

Basic Biology of Retinal Regeneration

In amphibians, particularly urodeles (salamanders), there is an extensive literature extending over 100 years, that new retina can be generated from the adjacent pigmented epithelial layer. If the retina is removed surgically or destroyed by transient interruption of the blood supply, the pigmented epithelial cells respond by re-entering the mitotic cell cycle (Figure 1b), losing their pigmentation, and forming a new layer [8, 9]. The cells of this new inner layer continue to proliferate and ultimately generate a complete new retina, with normal lamination, apparently normal ratios of the various neuronal cell types, and the ability to reconnect with central visual nuclei to restore visual function. The process starts with the de-differentiation of pigmented cells, and has been directly demonstrated using transplantation and in vitro observation [10] where individual pigmented cells could be followed over time. The progeny of the de-differentiated pigmented epithelial cells re-express neural retinal progenitor genes, and recapitulate the sequence of normal histogenesis. A similar process has been well characterized in chick embryos, but this phenomenon is confined to the earliest stages of eye development in these animals [11].

It has been known for many years that fish also have considerable ability to regenerate new retinal cells, not from the pigmented epithelium, but rather from a type of intrinsic progenitor [12]. In contrast to amphibian, the fish retina does not regenerate if all retina tissue but the RPE is removed. It has not been tested yet in fish whether RPE cells are completely restricted or whether a regenerative program can be stimulated by their manipulation, but spontaneous retinal regeneration in the fish stems only from cells within the neural retina. The natural source of the regenerating cells was unclear for many years, but, about five years ago, it became clear that the Müller glia were the primary source (Figure 1b), although rod precursors contribute as well [13-16]. After a variety of different lesion paradigms, including surgical, neurotoxic, genetic or light induced, the Müller glia in the fish retina undergo a robust proliferative response and regenerate all the different classes of neurons in the retina. Many of the Müller glia slowly divide in uninjured postembryonic fish retina and their progeny are thought to be exclusively rod photoreceptors [13]; however, upon damage to the retina, the Müller glia are competent to regenerate all the other types of neurons in the retina, in addition to the rod photoreceptors.

In both fish and amphibians, retinal damage thus generates a new progenitor; in the case of the fish, these progenitors are derived from the Müller glia, and in the amphibian, the new retinal progenitors are derived from the pigmented epithelial cells. It is also important to note that, in both cases, the retina has never really stopped growing. Both the fish and the amphibian retina contain a specialized zone of progenitor cells at the periphery that add new neurons of all types to the most peripheral edge of the retina (see above) (Figure 1b). In addition, the fish also adds new rods in the central retina from the slowly cycling Müller glia (see above); thus, in fish, the Müller cells play dual roles as both glia and progenitors [13]. The continual production of new rods from the Müller glia and the continued insertion of the new rods into the “mature” retinal circuit of the central fish retina, may thus explain the impressive regenerative capability of the Müller glia. In amphibians, where rod precursors are not present, the Müller cells may well lack the capacity for regeneration, and the pigmented epithelium takes over. Although the Müller cell response to retinal injury has not been as well studied in the amphibian, these cells do not appear to spontaneously re-enter the cell cycle after kainic acid retinal damage in the larval anuran retina [17].

Recently, a number of studies have begun to define the molecular requirements for regeneration in the fish retina. Fausett et al [18] found that the protein Achaete-scute homolog 1a (Ascl1a) is specifically upregulated early in the process of regeneration in fish retina, and inhibition of this transcription factor inhibits regeneration from the Müller glia. Blocking Müller cell division with morpholinos against expression of the replication factor proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) also blocks regeneration [19]. Several growth factors have also been shown to be upregulated during retinal regeneration in fish, including midkine-a and -b [20] and ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF). Moreover, CNTF is sufficient to stimulate Müller glial proliferation in the undamaged retina, via STAT3 [21]. Neural progenitor genes, including those encoding Olig2, Ascl1a, Ngn1, Notch1 and Pax6, are upregulated as the cells shift from a Müller glial pattern of gene expression to that of a retinal progenitor [22, 23]. Qin and colleagues [24] reported that the chaperone hspd1 and mps1 were specifically upregulated early in the process, and temperature-sensitive mutants in either gene were used to show that loss of function blocks regeneration. To date, at least four genes have been shown to be necessary for regeneration in the fish retina – encoding Ascl1a, PCNA, hspd1 and mps1 – and it is likely that the microarray analyses will continue to generate new candidates that can give a clearer picture of the factors required for successful regeneration. It is interesting that Müller glia normally express several of the genes required for generating induced pluripotent cells, including Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc. In addition, a recent article demonstrating that Ascl1 is one of four factors that can reprogram fibroblasts directly into neurons, is also consistent with the up-regulation of this factor during retinal regeneration from Müller glia.

Several years ago, Fischer and Reh [25] reported that the Müller glia of posthatch chicks respond to neurotoxic damage to the retina by re-entering the mitotic cell cycle. The initial experiments were done with NMDA, which largely targets amacrine cells, but in subsequent experiments, other neurotoxins damaging comparable and other classes of neurons were found to have similar effects. Although in undamaged retina, the Müller glia do not proliferate, after retinal damage, Müller glial proliferation is extensive, and in some regions of the retina nearly every Müller cell appears to incorporate the S-phase label BrdU. The Müller cells progress through M-phase, at the scleral surface of the retina, to generate two daughters; however, unlike the fish, they do not undergo multiple rounds of cell division. Attempts to stimulate the proliferation with injections of growth factors can prolong this process somewhat [26], and possibly recruit additional Müller glia into the cell cycle, but it appears that the Müller glia are limited in the number of new cells that can be generated after damage.

Further analysis of the effects of NMDA and other neurotoxins on Müller glia in birds demonstrated that a limited amount of neuronal regeneration can take place. After retinal damage, some of the proliferating Müller cells express a variety of progenitor genes; they up-regulate the homeobox domain protein Chx10 and the paired box protein Pax6 and they now express Cash1/Ascl1a, FoxN4, Notch1, Dll1, and Hes5 [25-27]. The re-expression of these genes, many of which are also up-regulated in the fish after damage (see above), would seem to indicate that the Müller glia have entered a progenitor state. As noted above, a high percentage of Müller glia re-enter the cell cycle after NMDA damage, but only a subset of these express the markers of progenitors. An even smaller number of these progenitor-like cells differentiate into cells that express neuronal markers. In the weeks following the NMDA treatment, the progeny of the Müller glia can be followed with BrdU labeling; BrdU-positive cells express markers of amacrine cells primarily (calretinin, and the RNA-binding proteins HuC/D), although bipolar cell markers (Islet1) and rare ganglion cell markers (Brn3; neurofilament) are also observed [particularly when the NMDA-treated retina is also treated with fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and insulin; [25, 26]. While some of the BrdU-positive cells express both the markers and morphology of inner retinal neurons, to date there is no evidence that these are functional or re-connect with the host circuits. Most of the newly generated Müller glia actually remain as Müller glia or persist as ‘progenitor-like’ cells, continuing to express a high level of Chx10 and Pax6, but progressing no further towards differentiation. Hayes and colleagues [27] tested whether persistent Notch signaling in these cells might be part of the reason for this intermediate state. Blocking Notch signaling with the gamma-secretase inhibitor DAPT resulted in a higher percentage of cells differentiating into amacrine cells than in the untreated retinas, consistent with this hypothesis, although blocking Notch signaling earlier in the process actually prevented Müller cell proliferation; these results suggest that Notch activation is crucial early in the regeneration process, but prolonged Notch activity can limit the effectiveness of the neuronal replacement.

The limited regenerative response observed in the posthatch chick is clearly different from that of the fish; however, some of the initial steps seem very similar: retinal damage in both chick and fish causes the Müller cells to proliferate and upregulate expression of neural progenitor genes. There are at least two important differences between the fish and the bird in the response of the Müller cells: first, in the chick, the Müller glia go through only a single round of cell division, whereas in fish they appear to go through multiple rounds of division producing progeny that form small neurogenic clusters [18-23, 28]. The second main difference is that only a small percentage of the progeny of the Müller glia differentiate as neurons in the bird, whereas in the fish most seem to do so. One thing both have in common is that there is considerable cell death of the progeny: in zebrafish, where functional retinal regeneration of all types of neurons occurs after damage, only approximately 30% of the original BrdU-positive Müller glia or their progeny remain after two weeks [15]; the same is true in the chick, where a similar decline in BrdU-positive neurons occurs over the weeks following their generation [27]. Many reports of adult neurogenesis/neuronal replacement have noted a similar decline in the newly generated neurons, with between 50 and 80% of them eliminated [29, 30] within a few weeks after they have been generated. It is not clear why this occurs, although it has been speculated that the new cells must make stable synaptic connections to survive; it appears that ‘many are called but few are chosen’.

Retinal Regeneration in Mammals

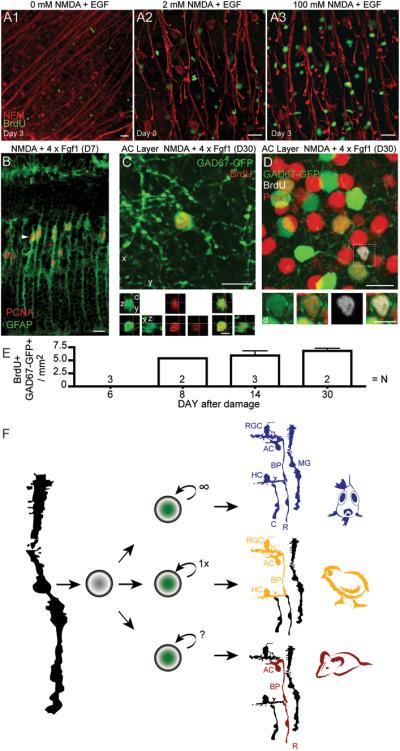

In the mammalian retina, the regenerative response of Müller glia to injury is even more limited than in the bird. In response to injury in mouse or rat retina, the Müller glia become reactive and hypertrophic [31], but few re-enter the mitotic cell cycle. Several groups have studied the response of the rat retina to damage, similar to that which produces the regenerative response in fish and posthatch chicks, and found that at least a sub-population of Müller glia can be induced to re-enter the mitotic cell cycle after retinal damage when treated with specific protein mitogens. For example, Sahel and colleagues [32] reported that NMDA, as well as kainic acid, domoic acid and ouabain, all caused retinal damage and Müller glial proliferation. The proliferative effects could be blocked by ketamine anesthesia, suggesting that these responses were not a result of the damage alone, but instead direct effects of the excitatory amino acids on the glial proliferation. More recently, a number of different markers (both for proliferating cells and for Müller glia and other retinal cell types) have been used to better characterize the proliferating cell populations. Ooto et al [33] made injections of NMDA in six-week-old rats, followed by BrdU and other growth factors. They found that a small number of Müller glia incorporated BrdU after the damage, and approximately 30% of these labelled cells persisted for 28 days. The amount of damage appears to be important for stimulating the Müller glial proliferative response as the more extensive retinal damage caused by methyl-nitrosourea (MNU) resulted in a large number of Müller glia re-entering the cell cycle in adult rats [34, 35]. It also appears that treating the retina with mitogenic growth factors after damage may increase the amount of Müller glial proliferation. Close and colleagues [36] found that EGF injections significantly increased the number of BrdU-positive Müller glia in adult rats after light damage (although Ooto et al. [33] did not find that FGF, insulin or a 10-fold lower dose of EGF stimulated proliferation in NMDA-damaged rat retinas). More recently, Osakada and colleagues [37] found that Wnt3a treatment could significantly increase the number of BrdU-positive Müller glia when coupled with the spontaneous retinal damage that occurs when retinas are maintained in explant culture. However, these studies were carried out in vitro, and so it is difficult to compare the numbers of BrdU-positive Müller cells with those produced in the earlier in vivo studies. The age of the animal at the time of testing also appears to be a crucial determinant of the ability of Müller cells to re-enter the mitotic cell cycle. The response of Müller glia to mitogens shows a large decline in the second postnatal week. Close and colleagues [36] reported that the number of BrdU-positive Müller glia after intraocular EGF injection at postnatal day 14 (P14) is only a tenth of that observed after a similar injection at P10. After P21, only an occasional BrdU-positive Müller glial cell is present after EGF injections. The loss in responsiveness to EGF correlates with the downregulation of the receptor EGFR that occurs over the same time-course.

To complement the rat data, and to take advantage of some excellent genetic resources, several groups have also studied damage-induced Müller glial proliferation in mice. In mice, Müller glial proliferation after injury appears to be even more restricted than in rats. Intraocular injections of ouabain, followed by BrdU, show only occasional BrdU-positive Müller glia [38]. Although the number of BrdU-positive Müller glia increases in explant cultures treated with ouabain, the percentages of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-reactive Müller cells that incorporate BrdU is still only about 5%. Nevertheless, Müller glia in the mouse can be stimulated by growth factors to re-enter the cell cycle. Karl and colleagues [39] reported that mouse Müller glia can be stimulated to proliferate when neurotoxic damage is coupled with growth factor injections. In NMDA-damaged retinas that were injected with EGF, thousands of Müller glia per retina were recruited into the mitotic cell cycle in vivo; by 72 hours after the injury, approximately 1% of the Sox2 labeled Müller glia are BrdU-positive. In addition, Takeda et al [40] found that sub-toxic doses of alpha-aminoadipic acid (alpha-AA) causes mouse Müller glia to re-enter the cell cycle in the absence of overt cell death. These studies then show the feasibility of using mice to further characterize the potential of Müller glia in mammalian retinal regeneration; the thousands of transgenic and knock-out lines of mice already available will enable more rapid progress in understanding the requirements of the regeneration process. Mice are also ideal for developing new strains and combinations of existing lines that allow for the manipulation of signaling pathways and transcription factors in the Müller glia.

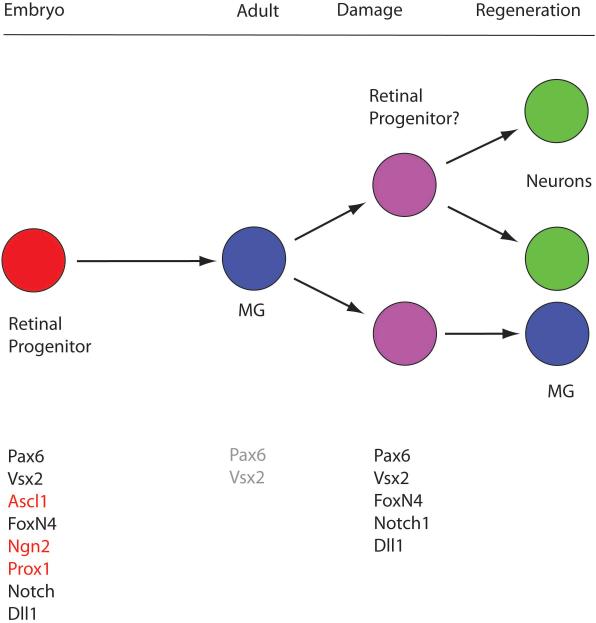

The studies in fish and posthatch chicks have shown retinal damage causes Müller glia to de-differentiate and express many retinal progenitor genes. The ability of Müller glia to adopt a retinal progenitor pattern of gene expression, such as the expression of the progenitor genes Ascl1a, PCNA and components of the Notch pathway (see above), correlates with their ability to regenerate neurons after damage. Therefore, several groups have carried out studies on damaged retina in rats and mice to determine whether aspects of the progenitor developmental program are reinitiated in Müller cells after damage. Several groups have found that markers of progenitor cells are expressed in Müller glia after damage. For example, Karl et al [39] and Osakada et al [37] found that Pax6 is upregulated in the Müller glia after NMDA damage or Wnt3a treatment, respectively, as are components of the Notch pathway, Dll1 and Notch1 [39, 41] and Nestin [35, 36]. Studies in human retina indicate that at least some part of the progenitor gene expression profile can be upregulated (eg. Sox2 and Pax6) in human Müller glia as well [42]. Despite the evidence that many progenitor genes are re-activated in the mammalian Muller glia after damage and mitotic stimulation, many critical progenitor genes do not appear to be re-expressed (Figure 2). This partial de-differentiation in mammalian Muller glia is in contrast to the more complete reversion to the progenitor phenotype observed in non-mammalian vertebrates, and may partly explain the very limited regeneration observed in mammals.

Figure 2.

Progenitor genes are re-expressed in the damaged retina. The Muller glia are generated during embryonic development from the retinal progenitors, the same cells that produce all the other retinal cell types described in Figure 1. In the mature retina of mice, the Muller glia are mitotically quiescent and no longer express most of the progenitor genes; however, some of the progenitor genes are up-regulated after damage and when the cells are induced to re-enter the cell cycle by treating the retina with growth factors/mitogens. This suggests that at least some of the Muller cells in the mature mammalian retina can de-differentiate to a partial progenitor state, and it may explain why the cells are able to regenerate a subset of retinal neurons.

All these studies have found evidence for expression of progenitor genes in Müller glia after retinal damage, but the evidence that neurons are generated from these cells is not nearly as clear as in fish. Ooto et al [33] reported that while nearly all of the BrdU-positive cells in the INL expressed Müller glial markers two or three days after the NMDA damage, by 14 or 28 days after the toxin, some expressed markers of bipolar cells and photoreceptors: protein kinase C (PKC), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), rhodopsin and the calcium-binding protein recoverin. In contrast, none of the cells expressed markers of ganglion cells, amacrine cells or horizontal cells, suggesting that the progeny of Müller glia were either incapable of differentiating into these types of inner retinal neurons or that newly generated bipolar and photoreceptors were selectively preserved. However, although amacrine cells were not spontaneously generated in their experiments, infecting the proliferating cells with viruses expressing neural differentiation genes, NeuroD1, Math3, and Pax6 in explant cultures promoted the amacrine cell fate, suggesting that the Müller glia retain competence for producing these cells as well. By contrast with the rat studies of Ooto and colleagues, Karl et al [39] found in adult mice that the combination of NMDA and mitogen treatments led to regeneration of new amacrine cells from the Müller glia: one week after NMDA and growth factor treatments, they found BrdU-positive cells that express several markers of amacrine cells, including calretinin, NeuN, Pax6, Prox1 and GAD67-GFP (Figure 3). As these studies were performed in GAD67-GFP-expressing mice, it was possible to discern the morphology of the BrdU-positive cells and many of the BrdU-positive cells had both a laminar position and morphology consistent with an amacrine cell identity. The predominance of amacrine cell regeneration after NMDA treatment might relate to the fact that amacrine cells are one of the major cell types that are destroyed by the toxin. Along these lines, FoxN4, a transcription factor necessary for the generation of amacrine cells during development, is one of the most highly up-regulated genes in both the mouse and chick retina after NMDA-induced damage [27, 39]. The fact that Ooto and colleagues [33] failed to detect amacrine cells in the BrdU-positive population, whereas these were the predominant neuronal population reported by Karl et al [39], might relate to the fact that the latter used mice in their analysis and treated the retinas with FGF/insulin in conjunction with NMDA damage, whereas Ooto et al [33] used rats for their analysis and did not follow the NMDA treatment with growth factors.

Figure 3.

Retinal regeneration in mice. A) In vivo, intraocular application of neurotoxin NMDA leads to loss of retinal ganglion cells (indicated by neurofilament stain; red). Müller glia re-enter cell cycle after neuronal cell loss when treated with a mitogen, like EGF (single application; A2, A3), but not so much with either treatment alone (A1: EGF only, NMDA only not shown but similar to A1). BrdU was applied starting on day 2 after damage (D2) to identify proliferation. B) After NMDA damage GFAP-Cre::RYFP labels Müller glia which upregulate PCNA after daily injections of FGF1 (48 hours after NMDA, D2) for four subsequent days (analyzed on D6). Interestingly, in fish and chick, damage is sufficient to stimulate Müller glia proliferation and multiple cell divisions lead to a larger number of progeny (see summary Fig. 3F). C) After damage and growth factor treatment (FGF1 plus insulin) of mouse retina in vivo, BrdU-positive cells start to express Pax6 (not shown) and GAD67-GFP 8 to 30 days later. GAD67-GFP mice express GFP in immature neurons, a subset of mature RGCs, horizontal and all GABAergic amacrine cells in adult mouse retina. BrdU and GAD67-GFP double-labeled cells are found, like amacrine neurons, in the inner nuclear (BrdU+ Prox1+ GAD67-GFP+) and retinal ganglion cell layer (not shown). D) At D30, some BrdU-positive GAD67-GFP+ labeled cells also express Prox1 (boxed cell) suggesting amacrine cell regeneration. E) Graph shows the number of BrdU-positive /GAD67-GFP-positive cells as a function of days after NMDA damage. F) In comparison with fish and chick, retinal regeneration in mice is limited not only due to a restricted number of Müller glia re-entering the cell cycle and generation of an insufficient number of progeny cells, but most interestingly in the limited number and types of neurons regenerated (colored /labeled cells are regenerated in the respective species; RGC, retinal ganglion cell; AC, amacrine neuron; BP, bipolar neuron; HC, horizontal neuron; R, rod- and C, cone-photoreceptor; MG, Müller glia). Images show z-axis projection of (c) 2 × 1μm and (d) 1 × 1μm. Scale bars: 5 μm in orthogonal and inset views; 10 μm all other views. (Figures A-E from [39]).

Several other groups have used other types of damage to study the potential for Müller glial cell-based regeneration in mice and rats. Wnt3a [37], MNU damage, sonic hedgehog (Shh) [34, 35], and alpha-AA [42] all increase Müller glial proliferation, and, when the BrdU-positive progeny were examined after survival periods of several days to weeks, all these studies reported most of the BrdU-positive cells now labeled for photoreceptor-specific markers, including rhodopsin, recoverin and Crx. The predominance of photoreceptor regeneration in some studies does not relate simply to the type of retinal damage as it is observed after NMDA, explant culture or MNU, each of which is likely to induce a very different type of neuronal degeneration [33-35, 37, 40]. While different signaling factors are known to direct multipotent retinal progenitors to different fates, the fact that diverse signals such as Wnt3a, Shh and alpha-AA result in primarily photoreceptor genesis from Müller glia suggests that the progeny of Müller glia are somehow biased towards the photoreceptor fate, and the activation of FGF and IGF signaling might direct these cells to an alternative amacrine fate.

Future Medical Applications

As noted in the Introduction, retinal cells degenerate in a variety of different diseases; some of the leading causes of retinal degeneration are diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and age-related macular degeneration; however, there are many other inherited and acquired conditions that lead to visual impairment from the loss of retinal cells. What are the prospects that stimulation of regeneration of retinal neurons from Müller glia is likely to be of clinical benefit? From the work outlined in the preceding sections, it is clear that the amount of regeneration in the mammalian retina is still far too small to be of clinical benefit for any of these diseases. Moreover, in some cases, the regeneration appears to be limited to only a few types of retinal cells. We clearly need a much better understanding of the factors that restrict proliferation and de-differentiation of the Müller glia if we hope to re-initiate the kind of regeneration found in non-mammalian vertebrates to the human retina.

It would seem then that the first problem of retinal repair by endogenous stem cells (ie. the Müller glia) can be stated as: How can we stimulate sufficient proliferation of the Müller glia to restore the lost cell numbers? While these may seem straightforward goals, there are significant issues with current approaches to address these questions that may limit clinical application. For example, Müller glia can proliferate in the human retina in some conditions, such as after retinal re-attachment surgery, leading to a pathology known as proliferative vitreoretinopathy [43, 44] (BOX 2). In addition, several of the factors used to stimulate the regeneration process, like growth factor injections, could lead to significant side-effects. For example, treatments that include FGF that promote regeneration of inner retinal neurons, might also stimulate blood vessel growth in the retina, which could have deleterious consequences. Lastly, retinoblastoma, a childhood tumor of the retina, is a potential result from uncontrolled proliferation of cells that are not unlike retinal progenitors in many respects [45]. The fish retinal Müller glia respond to damage by proliferating in a well controlled manner; we will need to know a great deal more about the mechanisms that precisely orchestrate this proliferative response if we are to duplicate it in the human retina without the complications described above.

BOX 2.

Reactive gliosis

Gliosis is a non-stereotypical response of glia associated with a pathological state that serves as an umbrella term describing various phenotypic changes. Gliosis can include cell hypertrophy, changes in gene expression and morphology, migration, and less often cell proliferation. The up-regulation of intermediate filament proteins like GFAP is recognized as a hallmark of gliosis. Throughout the CNS, glial cells become “reactive” by neuronal damage and environmental perturbations. Gliosis may vary depending on tissue, species, glia cell type and the type of insult.

Ithe mammalian retina, the typical response to damage is the reactive gliosis of the Müller glia. Gliosis in some species is accompanied by proliferation, as well as hypertrophy of the glia and GFAP expression. In rabbits, for example, rapid neuronal degeneration leads to proliferative gliosis, whereas slow degeneration causes gliosis without proliferation [61-63]. In human retina, penetration injury, retinal detachment due to blunt eye trauma or other retinal diseases may induce Müller cell proliferation, but the more common response is hypertrophy. In inherited retinal degenerations, which are by nature slow, a non-proliferative gliosis is more typical. However, proliferative vitreoretinopathy is the most common complication in retinal reattachment surgery and proliferating Müller glia cells are one of two major cell types involved. Moreover, mitotic Müller glia are commonly found in epiretinal membranes and subretinal fibrosis of diverse pathological origins. The migration and proliferation of Müller glia in the subretinal space interferes with the photoreceptors and the subretinal transport of nutrition and metabolites.

Gliosis is essentially a response of the glia that provides rapid repair of the retina, and underlies what some have termed the “glial scar,” a potential barrier to regeneration. One of the key factors in triggering gliosis is the growth factor CNTF, a well established neuroprotective factor. The expression of CNTF is increased after neuronal damage [64, 65] and gliosis occurs in mice that over-express CNTF or by the application of CNTF, even in the absence of retinal injury [66-68]. In damaged chick retina, CNTF application inhibits Müller glia-derived regeneration and instead stimulates gliosis (as assessed by GFAP expression) [69, 70]. While this result suggests that gliosis and regeneration may be alternate glial responses to damage, they are not exclusive alternatives: damaged fish retina regenerates completely, while at the same time many Müller glia hypertrophy and express GFAP [21].

The second part of the regenerative process in non-mammalian vertebrates is potentially even more challenging to recapitulate in a clinical setting. How can one induce the de-differentiation of the Müller glia into retinal progenitors, capable of generating all the retinal neurons again? The recent demonstrations that fibroblasts can be reprogrammed to ES cells in mouse and human suggests that less drastic feats of reprogramming, like that of Müller cells to retinal progenitors, should not be impossible, particularly given the similarity in gene expression between retinal progenitors and Müller glia [46]. Indeed, attempts have been made to directly reprogram astrocytes to generate neurons in the central nervous system, but the efficiency of this process is very low (eg. [47, 48]). Expression of proneural transcription factors into spinal cord astrocytes, for example, leads to only a small number of new neurons [48]. Moreover, no study has yet reported that Müller glia can be re-programmed to iPSCs using the combination of factors used for fibroblasts and other differentiated cells, despite the fact that they already express several of them (eg. Sox2, c-Myc, Klf4). Nevertheless, it may soon be possible to use combinations of transcription factors and small molecules to reprogram the cells in vitro, using methods similar to those for iPSCs, but it is difficult to see how this could be carried out in vivo, unless the reprogramming methods become much more efficient [49] and viral mis-expression more tightly controllable.

Are there alternatives to retinal regeneration from endogenous stem cells to repair the human retina after the loss of photoreceptors and inner retinal neurons? There has recently been progress in a somewhat different approach to cell-based therapy in the retina: transplantation of new retinal cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Several groups have successfully generated retinal cells, including rod and cone photoreceptors, from mouse, monkey, and human ES and iPS cells [49-55]. The retinal cells derived from either human ES or human iPS cells can be transplanted to adult mouse retina and incorporate into the host retina and differentiate into rod photoreceptors [51, 52, 56]. In at least one animal model of a congenital blindness, the ES derived retinal cells can even restore light responses to the animal [49]. The recent progress using similar cells in animal models of other neural degenerations and their approval for clinical trial in traumatic spinal injuries provides a clear path for a taking a similar approach in the treatment of retinal diseases.

Concluding remarks

In summary, there is now increasing evidence that the mammalian retina has a limited capacity for neuronal regeneration. Although there are still several key questions that need to be addressed, particularly those concerning the functional integration of the new cells, at least some of the components of the Müller response to injury are remarkably similar in teleosts, posthatch chicks, and rodents: in all cases, some of the Müller glial cells re-enter the mitotic cell cycle, express key components of the neurogenic program of retinal progenitors and produce at least some types of neurons. In fish, the new neurons are of all types and are functionally integrated into the existing circuitry, and gene array analyses are beginning to yield some interesting candidates that will help to understand and potentially control this phenomenon. Regeneration is considerably more limited in birds and rodents, both in quantity and types of neurons generated. Although this may represent a vestigial regenerative response in homeothermic vertebrates when compared with their cold-blooded relatives, Müller glia, the cellular source for regeneration, are present in all vertebrate retinas, and so a better understanding of the limits in their regenerative potential provides some hope for those who suffer from retinal degenerations.

BOX 3.

Outstanding questions for the future

At least some of the regenerative phenomena displayed in the fish and chick retina can be stimulated in the mouse retina, but there are several key questions that need to be addressed:

Why is the proliferation so limited in mice? Although studies have shown growth factors can stimulate this process, even in the best cases, only a fraction of the glia re-enter the cell cycle in vivo in mice and this population does not expand to form neurogenic cluster like in fish.

Are the Müller glia the source of the new neurons in mammals? Although the evidence is growing, to date there is no publication that has used a lineage tracer, as has been done in the fish to definitively demonstrate Müller glia are the source of the BrdU-positive neurons in mammals.

Does a subpopulation of dormant stem cells exist or do all glia in fish and chick, and RPE cells in amphibian, have the potential to spontaneously reactivate a regenerative program upon damage. If so, what are the mechanisms?

Entail regenerative programs molecular mechanism comparable to the reprogramming in the generation iPSCs? Currently we do not know whether it is possible to reprogram cells directly into another specific cell fate without the longer route of generating iPSC first and subsequent complex differentiation steps.

Are the progeny of the Müller glia after damage stable and connected to the retinal circuitry? At this writing, none of the studies in mice or rats has shown that the cells are functionally integrated with the pre-existing retinal circuit, as they are in the fish.

Why is the process of de-differentiation of Müller glia so limited in chicks and mice? While several studies have shown improvement in the numbers of Müller glia recruited into the cell cycle after various treatments, the numbers of neurons that differentiate from their progeny is still very small. The factors that limit the potency of the glia to become progenitors in mammals need to be better understood, and a recent report that demonstrate only three transcription factors can reprogram fibroblasts to neurons [71] suggests a way in which this barrier might be overcome.

Why do studies vary so much in the types of neurons that are generated after damage or growth factor treatment? While several studies show cells with both BrdU and photoreceptor markers after damage, only one study has used mice expressing GFP in specific cell types, and, in that study, no photoreceptors were regenerated. Future studies using mice with GFP expressed in photoreceptor lineages will be crucial to confirm photoreceptor regeneration.

Why do so many of the Müller glia progeny die over the weeks after the damage? Are most of the new neurons really not differentiating properly, or is it hard to squeeze into the mature circuitry?

By studying retinal regeneration can we learn new ways to prevent retinal \ degenerations, glean new strategies for cell replacement therapy or even make regeneration work in people to treat retinal disease? The plasticity required for the replacement of neurons in regenerating retina involves considerable rearrangement of connections between the neurons and encouraging these properties in the neurons may help preserve function even as their number decline in degenerative disease.

Are the gliotic response and the regenerative response antagonistic, are different responses due to heterogeneous glia subpopulations, or is gliosis part of a restricted regenerative program in mammals? Ultimately, retinal repair strategies could target and involve transplantation of glia cells – either preventing and maybe even reversing gliotic scarring for transplantation therapy and /or utilization of glia for endogenous neuronal regeneration. The retina seems to be a strong model to tease apart and identify novel molecular and signaling mechanisms of glia during gliotic scarring and the limitations in regeneration.

Various forms of inherited, acquired and age-related retinal degenerative diseases might need different therapeutic approaches and even combinations thereof. Early diagnosis would be advantageous (unfortunately still limited by the techniques available to the ophthalmologist) to apply therapies – which do not exist yet – to prevent disease progression. If loss of vision has occurred existing neurons might be manipulated to compensate, or lost neurons may need to be replaced either by cell transplantation or induction of endogenous regeneration. Many therapeutic approaches are currently studied and others still need to be discovered, because none have been sufficient to restore lost neurons effectively, yet.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge many helpful discussions with the members of the Rehlab, and particularly Team Regenerate. We also thank Dr. Joe Brzezinski for helpful criticisms of the manuscript and Dr. Olivia Bermingham-McDonogh for her constant, constructive criticisms.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jones BW, et al. Retinal remodeling triggered by photoreceptor degenerations. J Comp Neurol. 2003;464:1–16. doi: 10.1002/cne.10703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fariss RN, et al. Abnormalities in rod photoreceptors, amacrine cells, and horizontal cells in human retinas with retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:215–223. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moshiri A, et al. Retinal stem cells and regeneration. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:1003–1014. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041870am. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tropepe V, et al. Retinal stem cells in the adult mammalian eye. Science. 2000;287:2032–2036. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cicero SA, et al. Cells previously identified as retinal stem cells are pigmented ciliary epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6685–6690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901596106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reh TA, Fischer AJ. Retinal stem cells. Methods Enzymol. 2006;419:52–73. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)19003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perron M, et al. The genetic sequence of retinal development in the ciliary margin of the Xenopus eye. Dev Biol. 1998;199:185–200. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Araki M. Regeneration of the amphibian retina: role of tissue interaction and related signaling molecules on RPE transdifferentiation. Dev Growth Differ. 2007;49:109–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2007.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reh TA, et al. Common mechanisms of retinal regeneration in the larval frog and embryonic chick. Ciba Found Symp. 1991;160:192–204. doi: 10.1002/9780470514122.ch10. discussion 204-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reh TA, et al. Retinal pigmented epithelial cells induced to transdifferentiate to neurons by laminin. Nature. 1987;330:68–71. doi: 10.1038/330068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakami S, et al. Activin signaling limits the competence for retinal regeneration from the pigmented epithelium. Mech Dev. 2008;125:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raymond PA, Hitchcock PF. How the neural retina regenerates. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2000;31:197–218. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-46826-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernardos RL, et al. Late-stage neuronal progenitors in the retina are radial Muller glia that function as retinal stem cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7028–7040. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1624-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braisted JE, et al. Selective regeneration of photoreceptors in goldfish retina. Development. 1994;120:2409–2419. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fausett BV, Goldman D. A role for alpha1 tubulin-expressing Muller glia in regeneration of the injured zebrafish retina. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6303–6313. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0332-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris AC, et al. Genetic dissection reveals two separate pathways for rod and cone regeneration in the teleost retina. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:605–619. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reh TA. Cell-specific regulation of neuronal production in the larval frog retina. J Neurosci. 1987;7:3317–3324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-10-03317.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fausett BV, et al. The proneural basic helix-loop-helix gene ascl1a is required for retina regeneration. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1109–1117. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4853-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thummel R, et al. Inhibition of Muller glial cell division blocks regeneration of the light-damaged zebrafish retina. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:392–408. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calinescu AA, et al. Midkine expression is regulated by the circadian clock in the retina of the zebrafish. Vis Neurosci. 2009:1–7. doi: 10.1017/S0952523809990204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kassen SC, et al. CNTF induces photoreceptor neuroprotection and Muller glial cell proliferation through two different signaling pathways in the adult zebrafish retina. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:1051–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kassen SC, et al. Time course analysis of gene expression during light-induced photoreceptor cell death and regeneration in albino zebrafish. Dev Neurobiol. 2007;67:1009–1031. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yurco P, Cameron DA. Cellular correlates of proneural and Notch-delta gene expression in the regenerating zebrafish retina. Vis Neurosci. 2007;24:437–443. doi: 10.1017/S0952523807070496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qin Z, et al. Genetic evidence for shared mechanisms of epimorphic regeneration in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9310–9315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811186106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischer AJ, Reh TA. Muller glia are a potential source of neural regeneration in the postnatal chicken retina. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:247–252. doi: 10.1038/85090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer AJ, Reh TA. Exogenous growth factors stimulate the regeneration of ganglion cells in the chicken retina. Dev Biol. 2002;251:367–379. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayes S, et al. Notch signaling regulates regeneration in the avian retina. Dev Biol. 2007;312:300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raymond PA, et al. Molecular characterization of retinal stem cells and their niches in adult zebrafish. BMC Dev Biol. 2006;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petreanu L, Alvarez-Buylla A. Maturation and death of adult-born olfactory bulb granule neurons: role of olfaction. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6106–6113. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-06106.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cameron HA, McKay RD. Adult neurogenesis produces a large pool of new granule cells in the dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435:406–417. doi: 10.1002/cne.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bringmann A, et al. Cellular signaling and factors involved in Muller cell gliosis: neuroprotective and detrimental effects. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:423–451. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sahel JA, et al. Mitogenic effects of excitatory amino acids in the adult rat retina. Exp Eye Res. 1991;53:657–664. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ooto S, et al. Potential for neural regeneration after neurotoxic injury in the adult mammalian retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13654–13659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402129101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wan J, et al. Preferential regeneration of photoreceptor from Muller glia after retinal degeneration in adult rat. Vision Res. 2008;48:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wan J, et al. Sonic hedgehog promotes stem-cell potential of Muller glia in the mammalian retina. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;363:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Close JL, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression regulates proliferation in the postnatal rat retina. Glia. 2006;54:94–104. doi: 10.1002/glia.20361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osakada F, et al. Wnt signaling promotes regeneration in the retina of adult mammals. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4210–4219. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4193-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dyer MA, Cepko CL. Control of Muller glial cell proliferation and activation following retinal injury. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:873–880. doi: 10.1038/78774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karl MO, et al. Stimulation of neural regeneration in the mouse retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19508–19513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807453105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takeda M, et al. alpha-Aminoadipate induces progenitor cell properties of Muller glia in adult mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:1142–1150. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Das AV, et al. Neural stem cell properties of Muller glia in the mammalian retina: regulation by Notch and Wnt signaling. Dev Biol. 2006;299:283–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhatia B, et al. Distribution of Muller stem cells within the neural retina: evidence for the existence of a ciliary margin-like zone in the adult human eye. Exp Eye Res. 2009;89:373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewis GP, et al. Muller cell reactivity and photoreceptor cell death are reduced after experimental retinal detachment using an inhibitor of the Akt/mTOR pathway. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:4429–4435. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryan SJ. The pathophysiology of proliferative vitreoretinopathy in its management. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;100:188–193. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dyer MA, Bremner R. The search for the retinoblastoma cell of origin. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:91–101. doi: 10.1038/nrc1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jadhav AP, et al. Development and neurogenic potential of Muller glial cells in the vertebrate retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heins N, et al. Glial cells generate neurons: the role of the transcription factor Pax6. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:308–315. doi: 10.1038/nn828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohori Y, et al. Growth factor treatment and genetic manipulation stimulate neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis by endogenous neural progenitors in the injured adult spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11948–11960. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3127-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lamba DA, et al. Transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived photoreceptors restores some visual function in Crx-deficient mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ikeda H, et al. Generation of Rx+/Pax6+ neural retinal precursors from embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11331–11336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500010102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lamba DA, et al. Efficient generation of retinal progenitor cells from human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12769–12774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601990103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lamba DA, et al. Generation, purification and transplantation of photoreceptors derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meyer JS, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived neural progenitors incorporate into degenerating retina and enhance survival of host photoreceptors. Stem Cells. 2006;24:274–283. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Osakada F, et al. Toward the generation of rod and cone photoreceptors from mouse, monkey and human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:215–224. doi: 10.1038/nbt1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Osakada F, et al. In vitro differentiation of retinal cells from human pluripotent stem cells by small-molecule induction. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3169–3179. doi: 10.1242/jcs.050393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lamba DA, et al. Strategies for retinal repair: cell replacement and regeneration. Prog Brain Res. 2009;175:23–31. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17502-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Newman E, Reichenbach A. The Muller cell: a functional element of the retina. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:307–312. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bringmann A, Reichenbach A. Role of Muller cells in retinal degenerations. Front Biosci. 2001;6:E72–92. doi: 10.2741/bringman. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bringmann A, et al. Muller cells in the healthy and diseased retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2006;25:397–424. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Franze K, et al. Muller cells are living optical fibers in the vertebrate retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8287–8292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611180104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bringmann A, et al. Role of glial K(+) channels in ontogeny and gliosis: a hypothesis based upon studies on Muller cells. Glia. 2000;29:35–44. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(20000101)29:1<35::aid-glia4>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iandiev I, et al. Atypical gliosis in Muller cells of the slowly degenerating rds mutant mouse retina. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Inman DM, Horner PJ. Reactive nonproliferative gliosis predominates in a chronic mouse model of glaucoma. Glia. 2007;55:942–953. doi: 10.1002/glia.20516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peterson WM, et al. Ciliary neurotrophic factor and stress stimuli activate the Jak-STAT pathway in retinal neurons and glia. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4081–4090. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04081.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wen R, et al. Injury-induced upregulation of bFGF and CNTF mRNAS in the rat retina. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7377–7385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07377.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fisher SK, et al. Cellular remodeling in mammalian retina: results from studies of experimental retinal detachment. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2005;24:395–431. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kuzmanovic M, et al. GFAP promoter drives Muller cell-specific expression in transgenic mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3606–3613. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Winter CG, et al. A role for ciliary neurotrophic factor as an inducer of reactive gliosis, the glial response to central nervous system injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5865–5869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fischer AJ, et al. Different aspects of gliosis in retinal Muller glia can be induced by CNTF, insulin, and FGF2 in the absence of damage. Mol Vis. 2004;10:973–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fischer AJ, et al. BMP4 and CNTF are neuroprotective and suppress damage-induced proliferation of Muller glia in the retina. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27:531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vierbuchen T, et al. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nature08797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]