Abstract

Objective

To examine mediators of mifepristone treatment on improvements in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among women with symptomatic fibroids.

Methods

The study sample included women with symptomatic uterine fibroids who were treated with 5 mg or 2.5 mg of mifepristone or placebo. Assessments of uterine size (ultrasound), pain (McGill pain questionnaire), bleeding (diary), anemia (gm/dL), and HRQOL measured using the uterine fibroid symptom quality of life scale were done at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months. The improvements in HRQOL that could be explained by changes in these clinical factors were assessed.

Results

The final sample included 62 women. Treatment with mifepristone was associated with significant improvement in HRQOL, which was explained in part by reduction in pain (28%, P<0.001) and bleeding (18%, P<0.001). Reduction in uterine volume was of marginal significance (P = 0.05) and was associated with a decrease in HRQOL (7%). Much of the impact of treatment on HRQOL (61%) remained unexplained in this model.

Conclusions

Improvements in HRQOL after treatment with mifepristone are partly explained by improvements in pain and bleeding, but not uterine size. However, most of the improvement in HRQOL is not explained by improvements in these clinical parameters.

Keywords: Fibroids, Leiomyoma, Mifepristone, Quality of life

1. Introduction

Treatment with low-dose mifepristone improves health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among women with symptomatic uterine fibroids [1–5]. However, it is not clear to what extent improvements in clinical symptoms (pain and bleeding) and clinical findings (anemia and fibroid size) contribute to improvement in HRQOL. Studies of uterine artery embolization suggest that baseline symptoms of heavy bleeding, but not pain or bulk-related symptoms, largely predict change in HRQOL [6]. Little is known about what accounts for the improvements in HRQOL that are associated with mifepristone treatment. Thus, it is not clear whether improvements in HRQOL are explained by improvements in women's pain, bleeding or anemia, reductions in uterine or fibroid size, or in other pathways.

The primary aim of the present study was to examine whether improvements in HRQOL associated with treatment with low-dose mifepristone were mediated by improvements in clinical factors, such as reductions in uterine size, pain, anemia, and bleeding, or other factors.

2. Materials and methods

Results from two published clinical trials of low-dose mifepristone were analyzed [2,4]. Each study was approved by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board. Briefly, the first trial was a randomized, placebo-controlled trial designed to test the hypothesis that treatment with mifepristone improved fibroid-specific quality of life among women with symptomatic fibroids. Women were eligible for inclusion in the trial if they were 18 years of age or older and premenopausal, reported at least moderately severe fibroid-related symptoms (>39 on the uterine fibroid symptom quality of life [UFS-QOL] scale) [7], and had a total uterine volume by vaginal/abdominal ultrasound of 160 mL or greater and at least one fibroid that was 2.5 cm or larger. After informed consent was obtained, eligible participants (n=42) were randomly assigned to take a daily dose of 5 mg of mifepristone or a placebo of identical appearance for 6 months. Both participants and study personnel were blinded to the group assignment.

Outcomes were assessed using validated measures. The primary outcome was mean change in UFS-QOL [7] scale 1–100; higher scores indicate better quality of life. Examples of questions from this scale include: “During the past month, how distressed were you by heavy bleeding during your menstrual period; feeling tightness or pressure in your pelvic area; or feeling fatigued?” The UFS-QOL includes secondary scales to measure the perceived impact of fibroids on activities of daily living, general concern and worry, energy and mood, sense of self-control, self-consciousness, and sexual functioning. Other measures included global pain (McGill pain questionnaire [MPQ]) [8]. Each of these questionnaires was administered at baseline, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months until the end of the study, except the MPQ which was assessed monthly. Severity of vaginal bleeding was assessed each day by each participant using a previously validated pictorial chart that assigns values 0–4 to each day of no bleeding, spotting, light, moderate and heavy flow, respectively [9,10]. A monthly blood loss index was calculated by summing the results. Monthly assessments of the presence and intensity of probable fibroid symptoms (including pelvic pain, pelvic pressure, bladder pressure, urinary frequency, low back pain, rectal pain, and pain during sexual intercourse) and drug adverse effects (including hot flushes, headache, nausea, vomiting, mood swings, diarrhea, decreased libido, weakness, fatigue, and nervousness) were made using a standardized instrument consisting of 5-point Likert scale items.

Uterine volume, and fibroid size and number were assessed by vaginal and/or abdominal ultrasound (depending on fibroid size) at baseline, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months. The uterus was measured in 3 planes, and the total volume was calculated. The 5 largest fibroids were identified; a volume was calculated for each of the fibroids and the total volume was determined. Baseline uterine volume was subtracted from each subsequently measured uterine volume, and volume changes were analyzed.

The second study involved a 6-month open-label study of the effect of a daily dose of 2.5 mg of mifepristone [4]. Subject eligibility criteria and measures were identical to those of the first study. However, all participants (n=23) received the active drug. For the purposes of assessing predictors of change in HRQOL, we aggregated data from these two studies and included an indicator variable for mifepristone treatment including dose.

We first examined predictors of baseline HRQOL using the UFS-QOL total score. Specifically, we examined the impact of age (years), race (white/black), body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters), educational attainment (years), gravidity (number), uterine volume (mL), bleeding (index), baseline hemoglobin (mg/dL), pain (MPQ total score). Covariates whose P values were less than 0.10 were included in the final regression model.

Next, the predictors of change in HRQOL were examined through a series of sequential models that included these baseline covariates, treatment, and time together with each of the potential mediators (change in hemoglobin, change in bleeding, change in uterine size, and change in pain). We examined whether treatment with mifepristone remained significantly associated with change in HRQOL and the extent to which the effect of mifepristone treatment was attenuated after considering the effect of changes in these potential mediators.

The mediation analysis was implemented in a series of steps to analyze the effects of mifepristone treatment on the HRQOL into presumed direct effects of the drug and indirect effects (through mediating variables) [10]. The analysis was implemented in the following 3 steps with PROC GENMOD in SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

First, the effect of change in baseline variables on change in HRQOL from baseline to each time point was assessed. The predictors/covariates described above were examined. The backward model elimination method was used to select covariates that showed a significant effect on the outcome variable. Covariates whose P values were less than 0.10 (to avoid oversimplified model selection) were included in the final regression model. The generalized estimating equation (GEE) method with autoregressive AR(1) correlation was used to fit the model [11]. GEE is a robust statistical method for studying longitudinal data that accounts for repeated measurements over time. In the GEE method, only the mean and a working correlation structure are needed for the repeated measurements of outcome variable. The variances of the estimators of parameters of interest can be obtained easily from sandwich-type estimators that automatically account for correlations of the same measurements done on the same participant at different time points, which results in greater statistical power to detect effects.

All covariates with P values greater than 0.10 were removed from the model. Treatment group, BMI, race, education, time, time2, baseline HRQOL, and baseline uterine volume were selected in the final model. (The scatter plot of HRQOL versus time showed a nonlinear time trend so the term time2 was used to account for this nonlinearity). The treatment effect in the model was the total effect of treatment on the HRQOL.

Second, the direct effect of drug treatment on the HRQOL was assessed. HRQOL was regressed on variables selected from step 1 and the change in mediators (pain, uterine size, and bleeding) at each time point.

Finally, the effect of medical treatment on the mediators was examined by regression analysis. The response variables were the mediator variables at each time point, and the covariates were variables selected from step 1. The mediated effect of treatment (by each mediator) on the HRQOL was estimated on the basis of the product of corresponding direct and indirect effects. The total mediated effect represents the sum of the individual mediated effects. The direct effect represents the remaining effect of treatment on HRQOL not explained by the sum of these mediators.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 62 patients for whom data were available to be included in this study. The patients were mostly middle aged, African American and obese, and had received nearly 3 years of post high school education; these results are consistent with the epidemiology of symptomatic fibroids [12].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of women included in the study (n=62) a

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 43.6 ± 5.2 |

| Education, y | 14.7 ± 2.3 |

| BMI | 29.6 ± 7.6 |

| Gravidity | 2.5 ± 2.1 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12 ± 1.4 |

| Race (African American) | 55 |

| Nulliparous | 30 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters).

Values are given as mean ± SD or percentage.

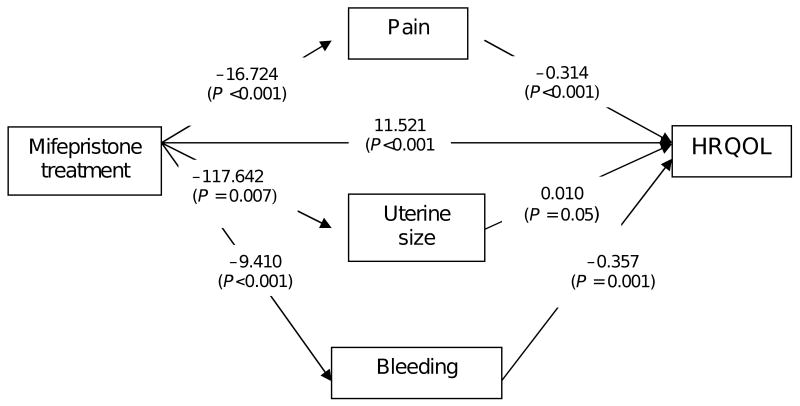

Table 2 shows the changes in HRQOL, pain, uterine size, blood loss over time, and hemoglobin level. Most improvements in clinical symptoms and reduction in uterine size occurred during the first 3 months. Figure 1 shows the results of the regression models from step 1 and step 2. Notably, mifepristone treatment is inversely associated with pain, bleeding, and uterine size, which means that treatment with mifepristone is associated with improvement in each of these clinical factors. In turn, bleeding and pain are inversely associated with HRQOL, which means that reductions in these factors are associated with improvement in HRQOL.

Table 2.

Time trend of variables by group.

| Variable | Time, mo. | Control (n=19) | Treatment (n=43) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean | SD | No. | Mean | SD | ||

| Health-related quality of life (USF-QOL) | 0 (baseline) | 19 | 40.79 | 24.11 | 43 | 39.77 | 20.46 |

| 1 | 19 | 52.42 | 26.62 | 20 | 64.40 | 22.40 | |

| 3 | 17 | 57.00 | 28.79 | 39 | 85.46 | 13.88 | |

| 6 | 17 | 57.47 | 27.99 | 35 | 88.86 | 13.27 | |

| Pain (MPQ Scale) | 0 (baseline) | 19 | 49.34 | 28.15 | 43 | 44.42 | 26.83 |

| 1 | 19 | 45.39 | 25.53 | 20 | 34.13 | 22.76 | |

| 3 | 17 | 51.32 | 26.68 | 39 | 17.69 | 19.73 | |

| 6 | 17 | 42.50 | 24.57 | 35 | 15.71 | 20.83 | |

| Uterine volume (mL by US) | 0 (baseline) | 19 | 450.63 | 242.08 | 43 | 639.99 | 532.48 |

| 1 | 19 | 507.60 | 285.11 | 20 | 673.71 | 633.21 | |

| 3 | 18 | 496.37 | 284.05 | 40 | 539.74 | 528.00 | |

| 6 | 17 | 530.31 | 294.36 | 35 | 527.05 | 597.57 | |

| Blood loss index | 0 (baseline) | 19 | 21.47 | 7.46 | 43 | 25.88 | 12.49 |

| 1 | 19 | 20.21 | 12.80 | 41 | 16.12 | 13.10 | |

| 2 | 19 | 15.74 | 8.15 | 41 | 3.56 | 8.45 | |

| 3 | 17 | 18.65 | 11.43 | 38 | 2.21 | 5.34 | |

| 4 | 17 | 23.47 | 12.95 | 37 | 3.78 | 6.85 | |

| 5 | 17 | 24.29 | 11.79 | 37 | 4.84 | 9.00 | |

| 6 | 17 | 16.12 | 6.37 | 37 | 7.85 | 14.19 | |

| Hemoglobin | 0 (baseline) | 19 | 12.29 | 1.31 | 43 | 11.89 | 1.42 |

| 1 | 19 | 11.94 | 1.51 | 20 | 12.59 | 1.36 | |

| 3 | 18 | 11.95 | 1.67 | 40 | 13.13 | 1.25 | |

| 6 | 17 | 11.60 | 2.17 | 35 | 13.34 | 1.12 | |

Abbreviations: USF-QOL, uterine fibroid symptoms quality of life; MPQ, McGill pain questionnaire; US, ultrasound.

Fig. 1.

Mediation analysis of the effect of mifepristone on health-related quality of life (UFS-QOL).

Table 3 summarizes the estimates for the direct and indirect (mediated) effects of mifepristone treatment on HRQOL; 61% of the total effect of mifepristone on HRQOL was from the direct effect of the drug and 39% is explained by improvement in clinical factors. Specifically, the contributions from improvements in pain, bleeding, and uterine size are shown. Improvement in anemia was not associated with a statistically significant improvement in quality of life.

Table 3.

Mediation analysis of mifepristone on HRQOL (UFS-QOL).

| Effect | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | 11.521 | 61 | |

| Indirect | Pain | (−16.7242) × (−0.3138) = 5.248 | 28 |

| Uterine size | (−117.642) × 0.0106 = −1.247 | −7 | |

| Bleeding | (−9.4097) × (−0.3567) = 3.356 | 18 | |

| Total | 18. 878 | 100.0 |

In summary, treatment with mifepristone showed a highly significant effect on reduction in pain (P <0.001), and the improvement of pain was associated with improvement in HRQOL (P<0.001). Reduction pain is the largest mediator (28%) of mifepristone effects on HRQOL.

Treatment with mifepristone is also associated with a highly significant effect on reduction in bleeding (P<0.001), and the reduction in bleeding is significantly associated with improvement in HRQOL (P = 0.001). Thus, reduction in bleeding is also a significant mediator of the effects of mifepristone (18%). Treatment with mifepristone had a significant effect on reduction in uterine size (P = 0.007), but change in uterine size is only marginally associated with HRQOL (P = 0.05) and the effect is negative (−7%). This finding suggests that reduction in uterine size has little if any relationship with improvement in HRQOL once reduction in pain and bleeding are accounted for.

4. Discussion

In previous studies [2,4], we showed that treatment with low-dose mifepristone is associated with clinically and statistically significant improvements in fibroid-specific HRQOL. In the present analysis, we explored pathways through which treatment with mifepristone improves fibroid-specific HRQOL. The results show that the effects of mifepristone on fibroid-specific quality of life were partly mediated through changes in pain and bleeding, but not by reduction in uterine size. In mediation models that included pain and bleeding, the effect of uterine size was marginally significant; the effect was small and in the opposite direction. These findings suggest that although treatment with mifepristone was associated with a reduction in uterine size, such improvements do not improve women's quality of life, at least not independently of improvements in pain and bleeding. This finding is consistent with data that show that there is little relationship between fibroid size and symptoms [13,14].

Much of the benefit of treatment with mifepristone on HRQOL remains unexplained. This finding raises the possibility that treatment with mifepristone may affect HRQOL through more direct pathways. For example, uterine fibroids are associated with increased cytokine activity, notably transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). Cytokine activity has been linked to reductions in well-being, greater fatigue, and increases in depressive symptoms [15], and depressive symptoms among women with symptomatic fibroids contribute to reduced functional status [16]. It is conceivable that treatment with mifepristone results in a reduction in cytokine activity that mediates improvement in quality of life independently of improvements in clinical symptoms. Alternatively, it is possible that measurement error and/or regression to the mean contributed to the unexplained variance. For example, it is possible that measurement error in clinical factors such as fibroid size, bleeding, and pain minimizes measurement of mediation effects. Measurement of uterine volume by ultrasound is less reliable than by magnetic resonance imaging [17]. The McGill pain questionnaire, although reliable and valid, may be less sensitive to fibroid-related pain. Assessment of bleeding based on the pictorial blood charts has been shown to be valid, but their reliability is uncertain [9,10]. Further study is needed to clarify additional pathways through which treatment with mifepristone improves quality of life among women with symptomatic uterine fibroids.

In conclusion, these findings suggest that improvements in clinical symptoms of pain and bleeding, but not reduction in uterine size, mediate improvements in HRQOL. However, much of the effect of mifepristone remains unexplained.

Acknowledgments

Supported by funding from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (Grant # R01-HD042578-01A1) and Athenium.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Eisinger SH, Meldrum S, Fiscella K, le Roux HD, Guzick DS. Low-dose mifepristone for uterine leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(2):243–50. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiscella K, Eisinger SH, Meldrum S, Feng C, Fisher SG, Guzick DS. Effect of mifepristone for symptomatic leiomyomata on quality of life and uterine size: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(6):1381–7. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000243776.23391.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagaria M, Suneja A, Vaid NB, Guleria K, Mishra K. Low-dose mifepristone in treatment of uterine leiomyoma: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49(1):77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisinger SH, Fiscella J, Bonfiglio T, Meldrum S, Fiscella K. Open-label study of ultra low-dose mifepristone for the treatment of uterine leiomyomata. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146(2):215–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carbonell Esteve JL, Acosta R, Heredia B, Perez Y, Castaneda MC, Hernandez AV. Mifepristone for the treatment of uterine leiomyomas: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):1029–36. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818aa930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spies JB, Myers ER, Worthington-Kirsch R, Mulgund J, Goodwin S, Mauro M, et al. The FIBROID Registry: symptom and quality-of-life status 1 year after therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(6):1309–18. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000188386.53878.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spies JB, Coyne K, Guaou GN, Boyle D, Skyrnarz-Murphy K, Gonzalves SM. The UFS-QOL, a new disease-specific symptom and health-related quality of life questionnaire for leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(2):290–300. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01702-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz J, Melzack R. Measurement of pain. Surg Clin North Am. 1999;79(2):231–52. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssen CA, Scholten PC, Heintz AP. A simple visual assessment technique to discriminate between menorrhagia and normal menstrual blood loss. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(6):977–82. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00062-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higham JM, O'Brien PM, Shaw RW. Assessment of menstrual blood loss using a pictorial chart. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97(8):734–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb16249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Goldman MB, Manson JE, Colditz GA, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(6):967–73. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arleo EK, Masheb RM, Pollak J, McCarthy S, Tal MG. Fibroid volume, location and symptoms in women undergoing uterine artery embolization: does size or position matter? Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2007;52(2–3):111–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torng PL, Chang WC, Hwang JS, Hsu WC, Wang JD, Huang SC, et al. Health-related quality of life after laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy: is uterine weight a major factor? Qual Life Res. 2007;16(2):227–37. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9123-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dantzer R, Kelley KW. Twenty years of research on cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(2):153–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lerner D, Mirza F, Chang H, Renzulli K, Perch K, Chelmow D. Impaired work performance among women with symptomatic uterine fibroids. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(10):1149–57. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181895e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broekmans FJ, Heitbrink MA, Hompes PG, Schoute E, Falke T, Schoemaker J. Quantitative MRI of uterine leiomyomas during triptorelin treatment: reproducibility of volume assessment and predictability of treatment response. Magn Reson Imaging. 1996;14(10):1127–35. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(96)00231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]