Abstract

Reading Disability (RD) is a significant impairment in reading accuracy, speed and/or comprehension despite adequate intelligence and educational opportunity. RD affects 5–12% of readers, has a well-established genetic risk, and is of unknown neurobiological cause or causes. In this review we discuss recent findings that revealed neuroanatomic anomalies in RD, studies that identified 3 candidate genes (KIAA0319, DYX1C1, and DCDC2), and compelling evidence that potentially link the function of candidate genes to the neuroanatomic anomalies. A hypothesis has emerged in which impaired neuronal migration is a cellular neurobiological antecedent to RD. We critically evaluate the evidence for this hypothesis, highlight missing evidence, and outline future research efforts that will be required to develop a more complete cellular neurobiology of RD.

INTRODUCTION

Reading Disability (RD) involves significant impairment of reading accuracy, speed and/or comprehension despite adequate intelligence and educational background (Katzir et al., 2006). Dyslexia presents with similar cognitive, neuroanatomical and genetic traits despite additional spelling and writing impairments associated with the disorder, therefore for the purpose of this review dyslexia is considered synonymous to RD. RD,, is a phenotypically complex developmental disorder with a significant genetic component. As the most common learning disability (Lerner JW, 1989), affecting 5–12% of school aged children, RD has far-reaching social and economic consequences. Several cognitive and perceptual changes appear to associate with RD including changes in short-term memory (Kibby MY et al., 2004; Swanson HL et al., 2006), occulomotor skills(Frith C and U Frith, 1996; Rayner K, 1998; Swanson HL et al., 2006), visuo-spatial abilities(Facoetti A et al., 2009); sensory processing(Tallal P, 1980; Tallal P et al., 1993; Tallal P et al., 1980; Wright CM and EG Conlon, 2009), semantic encoding (Booth JR et al., 2007), integration of letter and speech sounds(Blau V et al., 2009), and phonological processing (Habib M, 2000; Ramus F et al., 2003; Shaywitz SE et al., 1998). It remains controversial as to whether all of these features are central to the core RD phenotype, but the behavioral findings do suggest that any underlying cellular neurobiological cause of RD should have the capacity to affect multiple neural systems to varying degrees.

Over the past several years, increased evidence for neuroanatomic changes in RD, identification of candidate genes, and elucidation of the functions of three candidate genes (KIAA0319, DCDC2 and DYX1C1) in neuronal migration have strengthened a hypothesis which states that impaired neuronal migration in development causes a predisposition to RD. We review the evidence for this hypothesis and highlight both the missing pieces and future research efforts that will be needed for a more complete cellular understanding of RD.

NEUROANATOMY OF RD

Neuroanatomical studies have revealed neurostructural correlates of RD. Postmortem studies were the first to support an association between cortical migration anomalies and RD, and animal models have supported a causal connection between cortical migrational anomalies and specific deficits in perception and learning. More recent imaging studies have found evidence of changes in grey and white matter that correlate with RD. Evidence, however, is still lacking from the absence of a large scale anatomical study, and it remains unclear whether the identified neuronal migration anomalies in postmortem studies are directly related to changes in neocortical structure or function that have been revealed in MRI studies.

Ectopia

Postmortem neuroanatomical examination of a relatively small sample of individuals with RD and controls revealed increases in the incidence of a focal neocortical abnormality known as neocortical “ectopia” in RD brains (Galaburda AM, 1988; Galaburda AM and TL Kemper, 1979; Galaburda AM et al., 1985). These layer 1 ectopia are generally too small for detection by MRI, and are present in most control brains studied although at a much lower rate of occurrence than in RD brains. Ectopia occur as a result of disrupted migration caused by either abnormal interactions between migrating neuroblasts and radial glial fibers and/or disruptions in the pia and layer I (Caviness VS, Jr. et al., 1978; McBride MC and TL Kemper, 1982). The discovery of increased ectopia occurrence in RD was the first finding to suggest a connection between neuronal migration in the neocortex and RD.

Periventricular nodular heterotopia

Periventricular nodular heterotopia (PNH) are characterized by clusters of immature neurons partially embedded within the white matter near the surface of the lateral ventricles. This rare condition is most often caused by mutations in the x-linked gene filamin (Barkovich AJ and RI Kuzniecky, 2000; Dubeau F et al., 1995; Raymond AA et al., 1994), and loss of filamin function results in a failure of initial neuronal migration from the precursor population that lines the ventricles in fetal development. Studies combining in vivo imaging and behavioral assessments have shown an association between this cortical malformation and RD (Chang BS et al., 2007; Chang BS et al., 2005). More specifically, PNH patients show processing deficits in real-word and non-word reading tasks (Chang BS et al., 2007). Moreover, the reading deficits in PNH patients were independent of intelligence, and the severity of reading disability amongst this group was found to correlate strongly with the amount of white matter disruption proximal to the PNH malformations (Chang BS et al., 2007). The white matter changes found in studies relating PNH to RD are consistent with a growing body of evidence for changes in white matter tracts reported in several studies comparing RD and control cases with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) (Beaulieu C et al., 2005; Deutsch GK et al., 2005; Klingberg T et al., 2000; Niogi SN and BD McCandliss, 2006; Odegard TN et al., 2009; Steinbrink C et al., 2008).

Malformation models and behavioral disruption

Animal models of the malformations have been used to test whether focal neocortical abnormalities can create behavioral and sensory deficits similar to some non-language based deficits correlated with RD. Ectopias virtually identical to those described in humans have been found in three strains of autoimmune mice (i.e. NZB/BlNJ, BXSB/MPJ and NXSM-D/Ei). Mice with neocortical ectopias are impaired in spatial and non-spatial working memory (Balogh SA et al., 1998; Boehm GW et al., 1996; Denenberg VH et al., 2001; Hoplight BJ et al., 2001; Hyde LA et al., 2002), and in processing rapid auditory stimuli (Clark MG et al., 2000; Frenkel M et al., 2000; Peiffer AM et al., 2001). Similarly, male rats with induced-microgyria in parietal cortex, a disruption in cortical lamination with similarities to and often associated with ectopias, display rapid auditory processing deficits (Clark MG et al., 2000; Fitch RH, SW Threlkeld et al., 2008; Herman AE et al., 1997) and working memory deficits (Fitch RH, H Breslawski et al., 2008). In all, the animal studies indicate importantly that even relatively small malformations in neocortical structure can have very specific effects on sensory and learning tasks without having large scale effects on general learning ability.

GENETICS OF RD

The current status of RD genetic association efforts, reviewed more thoroughly elsewhere (Gibson CJ and JR Gruen, 2008; Paracchini S et al., 2007), underscores the complexity of RD genetics. The composite evidence clearly shows a strong genetic risk; however, even the most consistently associated genetic loci and genes have not been significantly associated with RD in all sample populations. Moreover, there is no reported extended pedigree or large multigenerational family showing a specific mutation in the coding region of one of the three most replicated candidate genes. Similarly, RD risk haplotypes in all candidate genes to date are found in a significant percentage of individuals without RD. In spite of these caveats, the identification of three candidate genes (KIAA0319, DYX1C1 and DCDC2) has ushered in a new era of RD research that can begin to focus on molecular and cellular mechanisms.

A brief history of RD genetics

Familial cases of RD was noted as early as 1896 by W.P. Morgan, and since then the overall risk of RD within a family with an affected individual has been estimated at between 34% and 48% (Finucci JM et al., 1976; Gilger JW et al., 1991; Hallgren B, 1950; Klasen, 1968; Zahalkova M et al., 1972). A strong genetic component to this familial association was demonstrated by twin studies. The first twin studies carried out in the 1950s showed a monozygotic concordance for RD of 100% (Hallgren B, 1950; Hermann K, 1956; Hermann K and E Norrie, 1958), however this was revised in later studies (Bakwin H, 1973; Decker SN and SG Vandenberg, 1985; Stevenson J et al., 1987), to a heritability between 29% and 82% (Alarcón M and JC DeFries, 1997; DeFries JC et al., 1987; DeFries JC and JJ Gillis, 1991; Harlaar N et al., 2005; Hawke JL et al., 2006; Hohnen B and J Stevenson, 1999; LaBuda MC and JC DeFries, 1988; Pennington BF and JW Gilger, 1996). The large range of estimated heritability likely indicates that the genetic risk for RD is complex and modifiable by a variety of environmental influences operating within different sample populations.

Genetic linkage disequilibrium analyses have now led to the identification of nine chromosomal loci across the genome that significantly associate with RD risk: DYX1-DYX9. Of these nine loci those located on chromosome 1p34-p36 (DYX8), 2p (DYX3), 6p21.3 (DYX2), and 15q21 (DYX1) have been frequently replicated, while those located at 3p12-q12 (DYX5), 6q13-q16 (DYX4), 11p15 (DYX7), 18p11 (DYX6), and Xq27 (DYX9) have been replicated once or not at all. Candidate susceptibility genes for DYX1 and DYX2, as well as other candidate genes are discussed below (see Table 1 for summary of recent findings).

Table 1.

| Significant association | N | Nationality | No significant association | N | Nationality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DYX1C1 | Taipale et al (2003)* | 109 | FIN | Bellini G et al (2005)* | 57 | IT |

| Wigg et al. (2004)** | 148 | CAN | Meng et al. (2005)** | 150 | US | |

| Brkanac Z et al (2007)** | 191 | US | Scerri et al (2004)** | 264 | UK | |

| Dahdouh F. et al (2009)** | 366 | GDR | Marino et al (2004)** | 158 | IT | |

| KIAA0319 | Francks et al (2004)** | 223 | UK | Brkanac Z et al (2007)** | 191 | US |

| Cope et al. (2004)** | 223 | UK | ||||

| Harold et al (2006)** | 148 | UK | ||||

| DCDC2 | Meng et al (2005)** | 150 | US | Brkanac Z et al (2007)** | 191 | US |

| Schumacher et al (2006)** | 239 | GDR | ||||

| Wilcke et al. (2009)* | 72 | GDR | ||||

| Ludwig et al (2008)** | 396 | GDR | ||||

Case control linkage disequillibrium

Family based transmission disequillibrium test

Candidate gene for DYX1: DYX1C1

DYX1C1 was the first gene to be linked to RD when it was reported in 2000 that a chromosomal translocation involving 15q in two Finnish families with a history of RD caused a breakpoint within the DYX1 locus (Nopola-Hemmi J et al., 2000; Nothen MM et al., 1999; Schulte-Korne G et al., 1998; Smith SD et al., 1983). Closer examination of the breakpoint showed that it disrupted exons of the gene EKN1, which was subsequently renamed Dyslexia Susceptibility 1 Candidate 1 (DYX1C1). Although this initial study showed a significant association in two relatively small Finnish samples (Taipale M et al., 2003), several subsequent studies in populations in the UK, US, and Italy did not find a significant association (Cope NA et al., 2005; Marino C et al., 2005; Meng H, K Hager et al., 2005). More recent studies of a German and US sample, however, have shown that one of the RD-related single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in DYX1C1 does associate with RD (Brkanac Z et al., 2007; Dahdouh F et al., 2009). In addition, a study of the same Italian sample in which a family based association between DYX1C1 risk alleles and RD was not found, did find a significant association with verbal short term memory (Marino C et al., 2007). Thus, DYX1C1 variants can associate with reading impairment in some population samples, and with component features often associated with RD in other samples (Marino C et al., 2007). Finally, the DYX1C1 risk allele associated with RD appears to be functional in that there is a change in the 5′ promoter region that affects DNA interaction with a complex of proteins (TFII-I, PARP1, and SFPQ) that regulate gene expression (Tapia-Paez I et al., 2008).

Candidate genes forDYX2: KIAA0319 and DCDC2

DYX2, on chromosome 6p, is the most replicated of DYX loci, and has been linked with both global and component RD phenotypes, particularly orthographic sub-phenotypes (Cardon LR et al., 1994; Cardon LR et al., 1995; Fisher SE et al., 1999; Grigorenko EL et al., 2003; Grigorenko EL et al., 1997; Kaplan D et al., 2002; Smith SD et al., 1991). Two peaks of genetic association have been identified within DYX2 that include two candidate genes, KIAA0319 and DCDC2 (Kaplan DE et al., 2002; Meng H, K Hager et al., 2005).

In 2002, Kaplan et al. showed a peak of association at a marker in the 5′ untranslated region of KIAA0319 (Kaplan DE et al., 2002). In 2004 a study by Francks et al. showed a peak of association in a 77 kb region containing the first four exons of KIAA0319, and this was replicated by Cope et al. in 2005 using a dense set of SNPs to further identify a risk haplotype in the same region (Cope N et al., 2005). The risk haplotype was later shown to be related to a selective decrease in the expression of KIAA0319 but not other genes in the locus (Harold D et al., 2006). The risk haplotype of KIAA0319 that includes the promoter region has more recently been shown to confer reduced promoter activity and an aberrant binding site for the transcriptional silencer OCT-1 (Dennis MY et al., 2009).

Meng et al. (2005) identified a deletion and compound short tandem repeat (STR) in intron 2 of DCDC2, a gene located 500 kb from KIAA0319. The STR in DCDC2 showed a significant association with RD in a cohort of 153 American dyslexic families (Meng H, K Hager et al., 2005), and this association was independently confirmed in a German population (Schumacher J et al., 2006). In this same association study in the German sample a haplotype within DCDC2 was identifiedthat showed strength of association directly proportional to the severity of RD (Schumacher J et al., 2006). More recently, the association between DCDC2 and RD has been independently confirmed in an Italian cohort, and the risk haplotype of DCDC2 associated with a decrease in enhancer activity (Meng et al. un published).

Other candidates genes

In addition to the three genes discussed above, candidate genes have also been identified in several other studies (Anthoni H et al., 2007; Hannula-Jouppi K et al., 2005; Poelmans G et al., 2009); however, the genes identified in these studies have not yet been reported to associate with RD in larger populations. In 2005, FISH analysis of a translocation (t(3;8)(p12;q11)) in a Finnish RD individual revealed disruption between exons 1 and 2 of ROBO1 on 3p (Hannula-Jouppi K et al., 2005). This gene lies within DYX5. Further linkage and association analysis of the proband’s extended family revealed a SNP haplotype spanning the gene that showed marginal association with RD. ROBO1 and its ligand SLIT are well known to play roles in axonal targeting and also in cell migration. As such, ROBO1 is a compelling developmental candidate gene that may have direct effects on the development of axonal connections.

FUNCTIONS OF CANDIDATE GENES

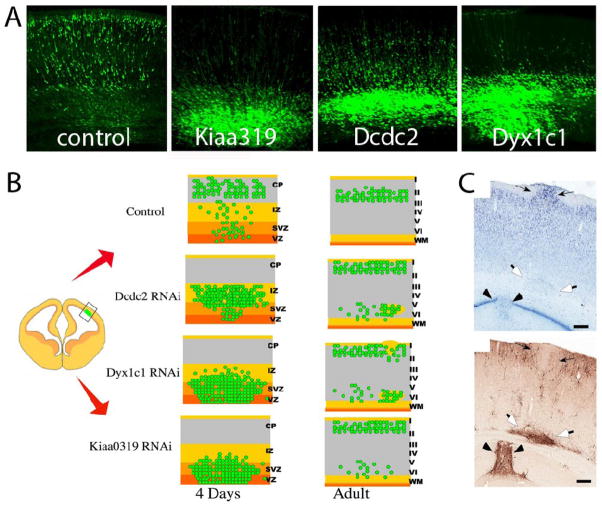

The identification of candidate genes DYX1C1, KIAA0319 and DCDC2, presented a new opportunity to begin to test hypotheses with respect to potential cellular causes of RD. The association of RD with neuronal migration impairment discussed above led to a series of experiments to determine whether these candidate genes play a role in neuronal migration, and if so, to determine the types of malformations created by decreased expression of these genes (Burbridge TJ et al., 2008; Meng H, SD Smith et al., 2005; Paracchini S et al., 2006; Rosen GD et al., 2007; Threlkeld SW et al., 2007; Wang Y et al., 2006). Figure 1 shows a summary of the results from these experiments. In this section we discuss the molecular features of three candidate genes as well as the studies that demonstrated their role in neuronal migration in developing neocortex. One limitation of the neuronal migration studies carried out so far is that they have directly tested for an involvement in migration in neocortex, and were not designed to test for changes in development of other structures or other developmental processes. Mouse knockout experiments are currently underway to test for a more general developmental role of these genes. The current evidence for a role in migration in neocortex should therefore not be viewed as evidence for a single specific function of the candidate genes in neuronal migration.

Figure 1.

Summary of RNAi studies demonstrating a role for Kiaa0319, Dcdc2, and Dyx1c1 in neuronal migration in the developing neocortex. A) Example images of eGFP (green) labeled neurons in a patch of embryonic neocortex 4 days after four different manipulations. “Control” shows the normal dispersion pattern of neurons after they have migrated.” Kiaa0319”, “Dcdc2”, and “Dyx1c1” panels show the effects on cell dispersion and migration following RNAi knockdown of the indicated candidate gene. Note that in each condition the vast majority of cells fail to disperse by migration, and that each RNAi condition creates a somewhat distinct pattern. B) A summary of RNAi results for both short-term and long-term effects of RNAi targeted against candidate genes (Burbridge TJ et al., 2008; Meng H, SD Smith et al., 2005; Paracchini S et al., 2006; Rosen GD et al., 2007; Wang Y et al., 2006). After 4 days of migration cells targeted with RNAi are largely stalled, but when examined in the adult brain the RNAi treatments caused a final phenotype that included normally positioned neurons, a mixture of heterotopia and ectopia, as well as scattered neuronal displacement. C) Example of three types of malformations resulting from Dyx1c1 RNAi and examined in the mature rat brain: ectopia (small arrows), white matter heterotopia (open arrows) and hipocampal dysplasia (arrow points). In the lower panel transfected cells are labeled brown (Rosen GD et al., 2007).

DYX1C1

The protein domains of DYX1C1 include an N-terminal p23 and three C-terminal tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domains. The N-terminal p23 domain of DYX1C1 protein, when overexpressed in cell lines, can interact with Hsp70, Hsp90 and an E-3 ubiquitin ligase, CHIP, suggesting that the protein may be involved in degradation of unfolded proteins (Hatakeyama S et al., 2004). Recently, DYX1C1 has been shown to be involved in the degradation of the estrogen receptor potentially through its interaction with CHIP (Massinen S et al., 2009).

In vivo RNAi studies indicate that Dyx1c1 plays a role in neuronal migration in developing neocortex. Soon after transfection of a cohort of newly produced neurons with plasmids that induce RNAi or knockdown of Dyx1c1 expression, neurons become arrested in their normal migration path through the intermediate zone (Wang Y et al., 2006). Wang et al. 2006, went on to show that the TPR domains of Dyx1c1 were critical to migration in that mutations missing the TPR domains failed to rescue migration while expression of the TPR domains alone was sufficient to restore normal migration. Moreover, a 3 amino acid deletion in the last TPR domain which results from a SNP that was initially shown to associate with RD, but later not replicated in any other population, was found to be dispensable for Dyx1c1 function in neuronal migration in neocortex (Wang Y et al., 2006).

In a follow-up study to the initial RNAi study, Rosen and colleagues (Rosen et al. 2007) examined what the final malformation profile would be for brains in which Dyx1c1 was knocked down. Although the embryo knockdown created a nearly uniform arrest in migration (Figure 1A), most neurons restarted their migration and attained position similar to control treated neurons by juvenile postnatal ages (Figure 1B). However disruption of the laminar organization of the cortex was still evident in the Dyx1c1 knockdown condition compared to RNAi control group treated at same developmental stage. In addition, distinct malformation types were found to occur with some variety in different animals. These malformations included heterotopia in white mater, ectopia in layer one of neocortex, and hippocampal heterotopia with dysplasia. Behavioral assays of animals with Dyx1c1 RNAi induced malformations have also shown impairments in auditory processing and maze learning, and the changes in learning were correlated with the presence of the hippocampal heterotopia (Threlkeld SW et al., 2007). Co-occurrence of deep malformations such as white matter heterotopia with superficial malformations such as ectopia and microgyria have also been reported in certain human malformation syndromes (Wieck G et al., 2005). Overall the experiments with Dyx1c1 knockdown have shown a surprising agreement with the neuronal migration hypothesis of RD. In particular the occurrence of diverse malformation types, including importantly ectopia (Figure 1C), and complex behavioral outcomes following a genetic disruption, are reminiscent of the RD phenotype.

KIAA0319

The KIAA0319 gene encodes an integral membrane protein with a large extracellular domain, a single transmembrane domain, and a small intracellular C-terminus. There are several splice variants of KIAA0319 (Velayos-Baeza A et al., 2007), all of which are glycosylated, and one form is secreted (Velayos-Baeza A et al., 2008). The extracellular domain is characterized by a consensus signal peptide, and 5 PKD domains. PKD domains in the polycytsin 1 protein have been shown to be involved in adhesion between kidney cells and so has been suggested as a cell adhesion domain (Silberberg M et al., 2005). To date, there is only one defined protein interactor of KIAA0319 protein, adaptor protein-2 (AP-2), which is part of the endosomal pathway (Levecque C et al., 2009). The structure, membrane localization, and emerging cell biology of KIAA0319 protein are consistent with it being in a relatively unstudied new class of neural cell adhesion molecule.

KIAA0319 expression was targeted with RNAi in migrating neocortical neurons to test for a potential role in migration. Similar to Dyx1c1, RNAi knockdown of Kiaa0319 interrupted migration 4 days after transfection (Figure 1) (Paracchini S et al., 2006). Kiaa0319 knockdown, in contrast to knockdown of Dcdc2 and Kiaa0319, created a distinct cellular phenotype. Namely, disrupted neurons appeared to loose their normal radial association with radial glial fibers and migrating neurons were often found orthogonal to the radial glia scaffold that they typically migrate along (Paracchini S et al., 2006). This phenotype, the emerging cell biology, and molecular structure of Kiaa0319 protein, suggest a possible role in neuron to radial glia adhesion; however, additional direct experimentation will be required to prove this role.

DCDC2

DCDC2 is one of an eleven-member group of proteins distinguished by the presence of dcx or doublecortin domains (Coquelle FM et al., 2006; Reiner O et al., 2006). The first characterized gene of this family, DCX, was identified by the discovery that mutations in DCX cause double cortex syndrome in females and lissencephaly in males (Barkovich AJ and RI Kuzniecky, 2000; Gleeson JG et al., 1999). The dcx domain is critical for binding to and stabilizing microtubules and is regulated by phosphorylation (Gleeson JG et al., 1999). At least two members of this family, Dcx and Dclk, have now been found to interact genetically in mice in terms of growth of axons across the corpus callosum and in neuronal migration in cerebral cortex (Deuel TA et al., 2006; Koizumi H et al., 2006). In a study comparing the biochemical and cellular functions of proteins in the Dcx family it was found that Dcdc2 exhibits the same functional features displayed by Dclk and Dcx protein (Coquelle FM et al., 2006).

Based on the similarity of structure between Dcdc2 and Dcx proteins Meng et al. (2005) hypothesized that DCDC2 may play a role in neuronal migration. Using an RNAi approach targeting Dcdc2 expression in migrating neocortical neurons in the embryonic rat neocortex it was found that knockdown of Dcdc2 interrupted neuronal migration (Meng H, SD Smith et al., 2005) (Figure 1). More recently, Burbridge et al. (2008) has shown that the migration disruptions caused by knockdown of Dcdc2 results in diverse disruptions similar to but not identical to those created by Dyx1c1 knockdown (Burbridge TJ et al., 2008). Knockdown of Dcdc2 creates both scattered heterotopia within the white matter similar to PNH, and also causes a population of neurons to over-migrate to ectopic positions in neocortex, although they do not form ectopia. The over-migration may be a secondary effect of migration delay because unlike the PNH “add back” or rescue experiments in which Dcdc2 is re-expressed resolved the PNH malformations, but did not eliminate the over-migration.

Conclusions

Accumulating evidence is highly suggestive of a connection between neuronal migration disruption and genetic susceptibility to RD. It would be premature however at this point to conclude that RD is a disorder of neuronal migration. The changes in migration may be correlates of another function of these initially defined candidate genes, and the majority of the genetic risk for RD is not carried by KIAA0319, DCDC2, or DYX1C1. In addition, other potential functions of these three genes have not yet been thoroughly tested in genetic knockout experiments. In fact, all three of these candidate genes are expressed in mature neurons after migration, and may therefore have important functions in such processes as synaptic plasticity that would also affect learning. Enhanced genetic techniques and larger genome wide studies will be needed in the future to identify a larger fraction of the genetic risk and to determine more definitively the contribution of KIAA0319, DCDC2, and DYX1C1 risk alleles. Such studies will likely include association of copy number variations (CNV) in RD as has recently been shown successful in identifying candidate genes for autism and schizophrenia (Cantor RM and DH Geschwind, 2008; Glessner JT et al., 2009; Sebat J et al., 2007). If RD does have a common underlying cause of neuronal migration impairment, then genes identified within such expanded searches would be expected to be genes that code for proteins involved in neuronal migration.

Enhanced structural and functional imaging studies are needed to more clearly define the set of anatomical changes that associate most frequently with RD. Future studies should also include correlation between imaging and genetics. In particular it would be important to determine whether the candidate gene alleles correspond to specific morphological alterations. A recent preliminary study indicates a potentially promising beginning to this approach (Meda SA et al., 2008).

Finally, the identification of a common neurodevelopmental disruption would only be the beginning of a mechanistic understanding of RD. Functional neurophysiological studies will be needed to connect any developmental disruption in neuronal positioning to changes in connectivity or function within cortical circuits. Work with animal genetic models will most likely be required to define in detail the specific cellular neurophysiological disruptions following interruption of RD related genes. There are already very effective educational interventions for RD that can greatly improve reading ability. Understanding the cellular basis of RD in detail in animal models could help to define critical periods of intervention, and may identify physiological mechanisms or changes that could be targeted pharmacologically to enhance early education-based remediation of RD.

Acknowledgments

Funding for CJG is from a Yale-Rosenberg Genetics Fellowship. Funding for JRG is provided by NIH R01 NS43530. Funding for JJL is provided by NIH R01HD

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alarcón M, DeFries JC. Reading Performance and General Cognitive Ability in Twins with Reading Difficulties and Control Pairs. Personality and Individual Differences. 1997;22:793–803. [Google Scholar]

- Anthoni H, Zucchelli M, Matsson H, Muller-Myhsok B, Fransson I, Schumacher J, Massinen S, Onkamo P, Warnke A, Griesemann H, Hoffmann P, Nopola-Hemmi J, Lyytinen H, Schulte-Korne G, Kere J, Nothen MM, Peyrard-Janvid M. A locus on 2p12 containing the co-regulated MRPL19 and C2ORF3 genes is associated to dyslexia. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:667–677. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakwin H. Reading disability in twins. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1973;15:184–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1973.tb15158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balogh SA, Sherman GF, Hyde LA, Denenberg VH. Effects of neocortical ectopias upon the acquisition and retention of a non-spatial reference memory task in BXSB mice. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;111:291–293. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkovich AJ, Kuzniecky RI. Gray matter heterotopia. Neurology. 2000;55:1603–1608. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu C, Plewes C, Paulson LA, Roy D, Snook L, Concha L, Phillips L. Imaging brain connectivity in children with diverse reading ability. Neuroimage. 2005;25:1266–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blau V, van Atteveldt N, Ekkebus M, Goebel R, Blomert L. Reduced neural integration of letters and speech sounds links phonological and reading deficits in adult dyslexia. Curr Biol. 2009;19:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm GW, Sherman GF, Rosen GD, Galaburda AM, Denenberg VH. Neocortical ectopias in BXSB mice: effects upon reference and working memory systems. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6:696–700. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.5.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth JR, Bebko G, Burman DD, Bitan T. Children with reading disorder show modality independent brain abnormalities during semantic tasks. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:775–783. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brkanac Z, Chapman NH, Matsushita MM, Chun L, Nielsen K, Cochrane E, Berninger VW, Wijsman EM, Raskind WH. Evaluation of candidate genes for DYX1 and DYX2 in families with dyslexia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:556–560. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbridge TJ, Wang Y, Volz AJ, Peschansky VJ, Lisann L, Galaburda AM, Lo Turco JJ, Rosen GD. Postnatal analysis of the effect of embryonic knockdown and overexpression of candidate dyslexia susceptibility gene homolog Dcdc2 in the rat. Neuroscience. 2008;152:723–733. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor RM, Geschwind DH. Schizophrenia: genome, interrupted. Neuron. 2008;58:165–167. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardon LR, Smith SD, Fulker DW, Kimberling WJ, Pennington BF, DeFries JC. Quantitative trait locus for reading disability on chromosome 6. Science. 1994;266:276–279. doi: 10.1126/science.7939663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardon LR, Smith SD, Fulker DW, Kimberling WJ, Pennington BF, DeFries JC. Quantitative Trait Locus for Reading Disability: Correction. Science. 1995;268:1553. doi: 10.1126/science.7777847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caviness VS, Jr, Evrard P, Lyon G. Radial neuronal assemblies, ectopia and necrosis of developing cortex: a case analysis. Acta Neuropathol. 1978;41:67–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00689559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang BS, Katzir T, Liu T, Corriveau K, Barzillai M, Apse KA, Bodell A, Hackney D, Alsop D, Wong ST, Walsh CA. A structural basis for reading fluency: white matter defects in a genetic brain malformation. Neurology. 2007;69:2146–2154. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000286365.41070.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang BS, Ly J, Appignani B, Bodell A, Apse KA, Ravenscroft RS, Sheen VL, Doherty MJ, Hackney DB, O’Connor M, Galaburda AM, Walsh CA. Reading impairment in the neuronal migration disorder of periventricular nodular heterotopia. Neurology. 2005;64:799–803. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152874.57180.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MG, Rosen GD, Tallal P, Fitch RH. Impaired processing of complex auditory stimuli in rats with induced cerebrocortical microgyria: An animal model of developmental language disabilities. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12:828–839. doi: 10.1162/089892900562435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope N, Harold D, Hill G, Moskvina V, Stevenson J, Holmans P, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC, Williams J. Strong evidence that KIAA0319 on chromosome 6p is a susceptibility gene for developmental dyslexia. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:581–591. doi: 10.1086/429131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope NA, Hill G, van den Bree M, Harold D, Moskvina V, Green EK, Owen MJ, Williams J, O’ MC. No support for association between dyslexia susceptibility 1 candidate 1 and developmental dyslexia. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:237–238. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coquelle FM, Levy T, Bergmann S, Wolf SG, Bar-El D, Sapir T, Brody Y, Orr I, Barkai N, Eichele G, Reiner O. Common and divergent roles for members of the mouse DCX superfamily. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:976–983. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.9.2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahdouh F, Anthoni H, Tapia-Paez I, Peyrard-Janvid M, Schulte-Korne G, Warnke A, Remschmidt H, Ziegler A, Kere J, Muller-Myhsok B, Nothen MM, Schumacher J, Zucchelli M. Further evidence for DYX1C1 as a susceptibility factor for dyslexia. Psychiatr Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32832080e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker SN, Vandenberg SG. Colorado Twin Study of Reading Disability. In: Gray DB, Kavanagh JF, editors. Biobehavioural Measures of Dyslexia. Parkton, MD: York Press; 1985. pp. 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- DeFries JC, Fulker DW, LaBuda MC. Evidence for a genetic aetiology in reading disability of twins. Nature. 1987;329:537–539. doi: 10.1038/329537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFries JC, Gillis JJ. Etiology of Reading Deficits in Learning Disabilities: Quantitative Genetic Analysis. In: Obrzut JE, Hynd GW, editors. Neuropsychologocal Foundations of Learning Disabilities: A Handbook of Issues, Methods and Practice. London: Academic Press, Inc; 1991. pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Denenberg VH, Hoplight B, Sherman GF, Mobraaten LE. Effects of the uterine environment and neocortical ectopias upon behavior of BXSB-Yaa+mice. Dev Psychobiol. 2001;38:154–163. doi: 10.1002/dev.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis MY, Paracchini S, Scerri TS, Prokunina-Olsson L, Knight JC, Wade-Martins R, Coggill P, Beck S, Green ED, Monaco AP. A common variant associated with dyslexia reduces expression of the KIAA0319 gene. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuel TA, Liu JS, Corbo JC, Yoo SY, Rorke-Adams LB, Walsh CA. Genetic interactions between doublecortin and doublecortin-like kinase in neuronal migration and axon outgrowth. Neuron. 2006;49:41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch GK, Dougherty RF, Bammer R, Siok WT, Gabrieli JD, Wandell B. Children’s reading performance is correlated with white matter structure measured by diffusion tensor imaging. Cortex. 2005;41:354–363. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubeau F, Tampieri D, Lee N, Andermann E, Carpenter S, Leblanc R, Olivier A, Radtke R, Villemure JG, Andermann F. Periventricular and subcortical nodular heterotopia. A study of 33 patients. Brain. 1995;118 ( Pt 5):1273–1287. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.5.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facoetti A, Trussardi AN, Ruffino M, Lorusso ML, Cattaneo C, Galli R, Molteni M, Zorzi M. Multisensory Spatial Attention Deficits Are Predictive of Phonological Decoding Skills in Developmental Dyslexia. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009 doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucci JM, Guthrie JT, Childs AL, Abbey H, Childs B. The genetics of specific reading disability. Ann Hum Genet. 1976;40:1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1976.tb00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher SE, Marlow AJ, Lamb J, Maestrini E, Williams DF, Richardson AJ, Weeks DE, Stein JF, Monaco AP. A quantitative-trait locus on chromosome 6p influences different aspects of developmental dyslexia. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:146–156. doi: 10.1086/302190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch RH, Breslawski H, Rosen GD, Chrobak JJ. Persistent spatial working memory deficits in rats with bilateral cortical microgyria. Behav Brain Funct. 2008;4:45. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-4-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch RH, Threlkeld SW, McClure MM, Peiffer AM. Use of a modified prepulse inhibition paradigm to assess complex auditory discrimination in rodents. Brain Res Bull. 2008;76:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel M, Sherman GF, Bashan KA, Galaburda AM, LoTurco JJ. Neocortical ectopias are associated with attenuated neurophysiological responses to rapidly changing auditory stimuli. Neuroreport. 2000;11:575–579. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200002280-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith C, Frith U. A biological marker for dyslexia. Nature. 1996;382:19–20. doi: 10.1038/382019a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaburda AM. The pathogenesis of childhood dyslexia. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1988;66:127–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaburda AM, Kemper TL. Cytoarchitectonic abnormalities in developmental dyslexia: a case study. Ann Neurol. 1979;6:94–100. doi: 10.1002/ana.410060203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaburda AM, Sherman GF, Rosen GD, Aboitiz F, Geschwind N. Developmental dyslexia: four consecutive patients with cortical anomalies. Ann Neurol. 1985;18:222–233. doi: 10.1002/ana.410180210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CJ, Gruen JR. The human lexinome: genes of language and reading. J Commun Disord. 2008;41:409–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilger JW, Pennington BF, DeFries JC. Risk for Reading Disability as a Function of Parental History in Three Family Studies. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 1991;3:205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson JG, Lin PT, Flanagan LA, Walsh CA. Doublecortin is a microtubule-associated protein and is expressed widely by migrating neurons. Neuron. 1999;23:257–271. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80778-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glessner JT, Wang K, Cai G, Korvatska O, Kim CE, Wood S, Zhang H, Estes A, Brune CW, Bradfield JP, Imielinski M, Frackelton EC, Reichert J, Crawford EL, Munson J, Sleiman PM, Chiavacci R, Annaiah K, Thomas K, Hou C, Glaberson W, Flory J, Otieno F, Garris M, Soorya L, Klei L, Piven J, Meyer KJ, Anagnostou E, Sakurai T, Game RM, Rudd DS, Zurawiecki D, McDougle CJ, Davis LK, Miller J, Posey DJ, Michaels S, Kolevzon A, Silverman JM, Bernier R, Levy SE, Schultz RT, Dawson G, Owley T, McMahon WM, Wassink TH, Sweeney JA, Nurnberger JI, Coon H, Sutcliffe JS, Minshew NJ, Grant SF, Bucan M, Cook EH, Buxbaum JD, Devlin B, Schellenberg GD, Hakonarson H. Autism genome-wide copy number variation reveals ubiquitin and neuronal genes. Nature. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nature07953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorenko EL, Wood FB, Golovyan L, Meyer M, Romano C, Pauls D. Continuing the Search for Dysleixa Genes on 6p. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B (Neuropsychiatric Genetics) 2003;118B:89–98. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.10032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorenko EL, Wood FB, Meyer MS, Hart LA, Speed WC, Shuster A, Pauls DL. Susceptibility loci for distinct components of developmental dyslexia on chromosomes 6 and 15. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1997;60:27–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib M. The neurological basis of developmental dyslexia: an overview and working hypothesis. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 12):2373–2399. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.12.2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren B. Specific Dyslexia (Congenital Word Blindness). A Clinical and Genetic Study. Acta Psychiatrica et Neurologica Supplementum. 1950;65:1–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannula-Jouppi K, Kaminen-Ahola N, Taipale M, Eklund R, Nopola-Hemmi J, Kaariainen H, Kere J. The axon guidance receptor gene ROBO1 Is a candidate gene for developmental dyslexia. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e50. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlaar N, Spinath F, Dale P, Plomin R. Genetic influences on early word recognition abilites and diabilites: a study of 7-year-old twins. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:373–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold D, Paracchini S, Scerri T, Dennis M, Cope N, Hill G, Moskvina V, Walter J, Richardson AJ, Owen MJ, Stein JF, Green ED, O’Donovan MC, Williams J, Monaco AP. Further evidence that the KIAA0319 gene confers susceptibility to developmental dyslexia. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:1085–1091. 1061. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama S, Matsumoto M, Yada M, Nakayama KI. Interaction of U-box-type ubiquitin-protein ligases (E3s) with molecular chaperones. Genes Cells. 2004;9:533–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawke JL, Wadsworth SJ, DeFries JC. Genetic Influences on Reading Difficulties in Boys and Girls: The Colorado Twin Study. Dyslexia. 2006;12:21–29. doi: 10.1002/dys.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman AE, Galaburda AM, Fitch RH, Carter AR, Rosen GD. Cerebral microgyria, thalamic cell size and auditory temporal processing in male and female rats. Cereb Cortex. 1997;7:453–464. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann K. Congenital Word Blindness. Acta Psychiatrica et Neurologica Scandinavica. 1956;108:177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann K, Norrie E. Is Congenital Word Blindness a Hereditary Type of Gerstmann’s Syndrome? Psychiatria et Neurologia. 1958;136:59–73. doi: 10.1159/000139549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohnen B, Stevenson J. The structure of genetic influences on general cognitive, language, phonological, and reading abilities. Dev Psychol. 1999;35:590–603. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.2.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoplight BJ, Sherman GF, Hyde LA, Denenberg VH. Effects of neocortical ectopias and environmental enrichment on Hebb-Williams maze learning in BXSB mice. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2001;76:33–45. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2000.3980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde LA, Stavnezer AJ, Bimonte HA, Sherman GF, Denenberg VH. Spatial and nonspatial Morris maze learning: impaired behavioral flexibility in mice with ectopias located in the prefrontal cortex. Behav Brain Res. 2002;133:247–259. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan D, Gayán J, Ahn J, Won T-W, Pauls D, Olson R, DeFries J, Wood F, Pennington B, Page G, Smith S, Gruen J. Evidence for linkage and association with reading disability on 6p21.3–22. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2002;70:1287–1298. doi: 10.1086/340449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DE, Gayán J, Ahn J, Won T-W, Pauls D, Olson RK, DeFries JC, Wood F, Pennington BF, Page GP, Smith SD, Gruen JR. Evidence for Linkage and Association with Reading Disability, on 6p21.3–22. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2002;70:1287–1298. doi: 10.1086/340449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibby MY, Marks W, Morgan S, Long CJ. Specific impairment in developmental reading disabilities: a working memory approach. J Learn Disabil. 2004;37:349–363. doi: 10.1177/00222194040370040601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasen . Legasthenia. Bern; Huber: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Klingberg T, Hedehus M, Temple E, Salz T, Gabrieli JD, Moseley ME, Poldrack RA. Microstructure of temporo-parietal white matter as a basis for reading ability: evidence from diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging. Neuron. 2000;25:493–500. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80911-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi H, Tanaka T, Gleeson JG. Doublecortin-like kinase functions with doublecortin to mediate fiber tract decussation and neuronal migration. Neuron. 2006;49:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBuda MC, DeFries JC. Genetic and Environmental Etiologies of Reading Disability: A Twin Study. Annals of Dyslexia. 1988;38:131–138. doi: 10.1007/BF02648252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner JW. Educational interventions in learning disabilities. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28:326–331. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levecque C, Velayos-Baeza A, Holloway ZG, Monaco AP. The dyslexia-associated protein KIAA0319 interacts with Adaptor Protein 2 and follows the classical clathrin-mediated endocytosis pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00630.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino C, Citterio A, Giorda R, Facoetti A, Menozzi G, Vanzin L, Lorusso ML, Nobile M, Molteni M. Association of short-term memory with a variant within DYX1C1 in developmental dyslexia. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:640–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino C, Giorda R, Lorusso ML, Vanzin L, Salandi N, Nobile M, Citterio A, Beri S, Crespi V, Battaglia M, Molteni M. A Family-Based Association Study Does Not Support DYX1C1 on 15q21.3 as a Candidate Gene in Developmental Dyslexia. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2005:1–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massinen S, Tammimies K, Tapia-Paez I, Matsson H, Hokkanen ME, Soderberg O, Landegren U, Castren E, Gustafsson JA, Treuter E, Kere J. Functional interaction of DYX1C1 with estrogen receptors suggests involvement of hormonal pathways in dyslexia. Hum Mol Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride MC, Kemper TL. Pathogenesis of four-layered microgyric cortex in man. Acta Neuropathol. 1982;57:93–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00685375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda SA, Gelernter J, Gruen JR, Calhoun VD, Meng H, Cope NA, Pearlson GD. Polymorphism of DCDC2 Reveals Differences in Cortical Morphology of Healthy Individuals-A Preliminary Voxel Based Morphometry Study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2008;2:21–26. doi: 10.1007/s11682-007-9012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng H, Hager K, Held M, Page GP, Olson RK, Pennington BF, DeFries JC, Smith SD, Gruen JR. TDT-association analysis of EKN1 and dyslexia in a Colorado twin cohort. Hum Genet. 2005;118:87–90. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng H, Smith SD, Hager K, Held M, Liu J, Olson RK, Pennington BF, DeFries JC, Gelernter J, O’Reilly-Pol T, Somlo S, Skudlarski P, Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA, Marchione K, Wang Y, Paramasivam M, LoTurco JJ, Page GP, Gruen JR. DCDC2 is associated with reading disability and modulates neuronal development in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17053–17058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508591102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niogi SN, McCandliss BD. Left lateralized white matter microstructure accounts for individual differences in reading ability and disability. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:2178–2188. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nopola-Hemmi J, Taipale M, Haltia T, Lehesjoki AE, Voutilainen A, Kere J. Two translocations of chromosome 15q associated with dyslexia. J Med Genet. 2000;37:771–775. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.10.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothen MM, Schulte-Korne G, Grimm T, Cichon S, Vogt IR, Muller-Myhsok B, Propping P, Remschmidt H. Genetic linkage analysis with dyslexia: evidence for linkage of spelling disability to chromosome 15. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;8:56–59. doi: 10.1007/pl00010696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odegard TN, Farris EA, Ring J, McColl R, Black J. Brain connectivity in non-reading impaired children and children diagnosed with developmental dyslexia. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:1972–1977. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paracchini S, Scerri T, Monaco AP. The genetic lexicon of dyslexia. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2007;8:57–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.8.080706.092312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paracchini S, Thomas A, Castro S, Lai C, Paramasivam M, Wang Y, Keating BJ, Taylor JM, Hacking DF, Scerri T, Francks C, Richardson AJ, Wade-Martins R, Stein JF, Knight JC, Copp AJ, Loturco J, Monaco AP. The chromosome 6p22 haplotype associated with dyslexia reduces the expression of KIAA0319, a novel gene involved in neuronal migration. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1659–1666. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiffer AM, Dunleavy CK, Frenkel M, Gabel LA, LoTurco JJ, Rosen GD, Fitch RH. Impaired detection of variable duration embedded tones in ectopic NZB/BINJ mice. Neuroreport. 2001;12:2875–2879. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200109170-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington BF, Gilger JW. How is Dyslexia Transmitted? In: Developmental Dyslexia. In: Chase CH, Rosen GD, Sherman GF, editors. Neural, Cognitive and Genetic Mechanisms. Baltimore, Maryland: York Press; 1996. pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Poelmans G, Engelen JJ, Van Lent-Albrechts J, Smeets HJ, Schoenmakers E, Franke B, Buitelaar JK, Wuisman-Frerker M, Erens W, Steyaert J, Schrander-Stumpel C. Identification of novel dyslexia candidate genes through the analysis of a chromosomal deletion. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B:140–147. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramus F, Rosen S, Dakin SC, Day BL, Castellote JM, White S, Frith U. Theories of developmental dyslexia: insights from a multiple case study of dyslexic adults. Brain. 2003;126:841–865. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond AA, Fish DR, Stevens JM, Sisodiya SM, Alsanjari N, Shorvon SD. Subependymal heterotopia: a distinct neuronal migration disorder associated with epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:1195–1202. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.10.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K. Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychol Bull. 1998;124:372–422. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner O, Coquelle FM, Peter B, Levy T, Kaplan A, Sapir T, Orr I, Barkai N, Eichele G, Bergmann S. The evolving doublecortin (DCX) superfamily. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:188. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen GD, Bai J, Wang Y, Fiondella CG, Threlkeld SW, LoTurco JJ, Galaburda AM. Disruption of neuronal migration by RNAi of Dyx1c1 results in neocortical and hippocampal malformations. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:2562–2572. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Korne G, Grimm T, Nothen MM, Muller-Myhsok B, Cichon S, Vogt IR, Propping P, Remschmidt H. Evidence for linkage of spelling disability to chromosome 15. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:279–282. doi: 10.1086/301919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher J, Anthoni H, Dahdouh F, Konig IR, Hillmer AM, Kluck N, Manthey M, Plume E, Warnke A, Remschmidt H, Hulsmann J, Cichon S, Lindgren CM, Propping P, Zucchelli M, Ziegler A, Peyrard-Janvid M, Schulte-Korne G, Nothen MM, Kere J. Strong genetic evidence of DCDC2 as a susceptibility gene for dyslexia. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:52–62. doi: 10.1086/498992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Malhotra D, Troge J, Lese-Martin C, Walsh T, Yamrom B, Yoon S, Krasnitz A, Kendall J, Leotta A, Pai D, Zhang R, Lee YH, Hicks J, Spence SJ, Lee AT, Puura K, Lehtimaki T, Ledbetter D, Gregersen PK, Bregman J, Sutcliffe JS, Jobanputra V, Chung W, Warburton D, King MC, Skuse D, Geschwind DH, Gilliam TC, Ye K, Wigler M. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with autism. Science. 2007;316:445–449. doi: 10.1126/science.1138659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA, Pugh KR, Fulbright RK, Constable RT, Mencl WE, Shankweiler DP, Liberman AM, Skudlarski P, Fletcher JM, Katz L, Marchione KE, Lacadie C, Gatenby C, Gore JC. Functional disruption in the organization of the brain for reading in dyslexia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2636–2641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg M, Charron AJ, Bacallao R, Wandinger-Ness A. Mispolarization of desmosomal proteins and altered intercellular adhesion in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F1153–1163. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00008.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SD, Kimberling WJ, Pennington BF. Screening for Multiple Genes Influencing Dyslexia. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 1991;3:285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SD, Kimberling WJ, Pennington BF, Lubs HA. Specific reading disability: identification of an inherited form through linkage analysis. Science. 1983;219:1345–1347. doi: 10.1126/science.6828864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrink C, Vogt K, Kastrup A, Muller HP, Juengling FD, Kassubek J, Riecker A. The contribution of white and gray matter differences to developmental dyslexia: insights from DTI and VBM at 3.0 T. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:3170–3178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson J, Graham P, Fredman G, McLoughlin V. A Twin Study of Genetic Influences on Reading and Spelling Ability and Disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1987;28:229–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1987.tb00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson HL, Howard CB, Saez L. Do different components of working memory underlie different subgroups of reading disabilities? J Learn Disabil. 2006;39:252–269. doi: 10.1177/00222194060390030501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taipale M, Kaminen N, Nopola-Hemmi J, Haltia T, Myllyluoma B, Lyytinen H, Muller K, Kaaranen M, Lindsberg PJ, Hannula-Jouppi K, Kere J. A candidate gene for developmental dyslexia encodes a nuclear tetratricopeptide repeat domain protein dynamically regulated in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11553–11558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1833911100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallal P. Auditory temporal perception, phonics, and reading disabilities in children. Brain Lang. 1980;9:182–198. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(80)90139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallal P, Miller S, Fitch RH. Neurobiological basis of speech: a case for the preeminence of temporal processing. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;682:27–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb22957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallal P, Stark RE, Kallman C, Mellits D. Developmental dysphasia: relation between acoustic processing deficits and verbal processing. Neuropsychologia. 1980;18:273–284. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(80)90123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia-Paez I, Tammimies K, Massinen S, Roy AL, Kere J. The complex of TFII-I, PARP1, and SFPQ proteins regulates the DYX1C1 gene implicated in neuronal migration and dyslexia. Faseb J. 2008;22:3001–3009. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-104455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlkeld SW, McClure MM, Bai J, Wang Y, LoTurco JJ, Rosen GD, Fitch RH. Developmental disruptions and behavioral impairments in rats following in utero RNAi of Dyx1c1. Brain Res Bull. 2007;71:508–514. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velayos-Baeza A, Toma C, da Roza S, Paracchini S, Monaco AP. Alternative splicing in the dyslexia-associated gene KIAA0319. Mamm Genome. 2007;18:627–634. doi: 10.1007/s00335-007-9051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velayos-Baeza A, Toma C, Paracchini S, Monaco AP. The dyslexia-associated gene KIAA0319 encodes highly N- and O-glycosylated plasma membrane and secreted isoforms. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:859–871. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Paramasivam M, Thomas A, Bai J, Kaminen-Ahola N, Kere J, Voskuil J, Rosen GD, Galaburda AM, Loturco JJ. DYX1C1 functions in neuronal migration in developing neocortex. Neuroscience. 2006;143:515–522. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieck G, Leventer RJ, Squier WM, Jansen A, Andermann E, Dubeau F, Ramazzotti A, Guerrini R, Dobyns WB. Periventricular nodular heterotopia with overlying polymicrogyria. Brain. 2005;128:2811–2821. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CM, Conlon EG. Auditory and visual processing in children with dyslexia. Dev Neuropsychol. 2009;34:330–355. doi: 10.1080/87565640902801882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahalkova M, Vrzal V, Kloboukova E. Genetical investigations in dyslexia. J Med Genet. 1972;9:48–52. doi: 10.1136/jmg.9.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]