Abstract

To understand whether the spatial organization of the genome reflects the cell's differentiated state, we examined whether genes assume specific subnuclear positions during Caenorhabditis elegans development. Monitoring the radial position of developmentally controlled promoters in embryos and larval tissues, we found that small integrated arrays bearing three different tissue-specific promoters have no preferential position in nuclei of undifferentiated embryos. However, in differentiated cells, they shifted stably toward the nuclear lumen when activated, or to the nuclear envelope when silent. In contrast, large integrated arrays bearing the same promoters became heterochromatic and nuclear envelope-bound in embryos. Tissue-specific activation of promoters in these large arrays in larvae overrode the perinuclear anchorage. For transgenes that carry both active and inactive promoters, the inward shift of the active promoter was dominant. Finally, induction of master regulator HLH-1 prematurely induced internalization of a muscle-specific promoter array in embryos. Fluorescence in situ hybridization confirmed analogous results for the endogenous endoderm-determining gene pha-4. We propose that, in differentiated cells, subnuclear organization arises from the selective positioning of active and inactive developmentally regulated promoters. We characterize two forces that lead to tissue-specific subnuclear organization of the worm genome: large repeat-induced heterochromatin, which associates with the nuclear envelope like repressed genes in differentiated cells, and tissue-specific promoters that shift inward in a dominant fashion over silent promoters, when they are activated.

Keywords: C. elegans, development, gene regulation, nuclear organization, chromatin

During metazoan development, the generation of differentiated cell types requires the orchestrated expression of thousands of genes. As cells differentiate, they become progressively committed to specific lineages and, concomitantly, their developmental potential becomes restricted (Yamanaka 2009). The reduction of cell fate potential is accompanied by an extinction of lineage-inappropriate expression programs, mediated largely by local and higher-order chromatin modifications (Boyer et al. 2006; Mohn and Schubeler 2009). As the number of repressed genes increases, the expression of genes appropriate for a given differentiation program ensues.

Based on studies in yeast, flies, and mammalian cells, it has been argued that nuclear subcompartments influence both gene repression and activation (for review, see Spector 2003; Taddei et al. 2004; Akhtar and Gasser 2007; Schneider and Grosschedl 2007). Hence, it may be expected that the organization of chromatin in the nucleus is cell type-specific. To date, studies addressing this question focused primarily on differentiation-specific juxtaposition of silent genes to heterochromatin and the clustering of active genes in transcription foci (Kosak and Groudine 2004b; Fraser and Bickmore 2007). Both events are well-characterized in hematopoietic lineages, where the radial organization of tissue-specific genes tends to reflect expression competence (Schneider and Grosschedl 2007). For example, developmental stage-specific repositioning away from the nuclear periphery has been shown for the mouse IgH and IgK loci upon activation and rearrangement of the locus during lymphocyte development (Brown et al. 2001; Kosak et al. 2002). In T cells, large-scale repositioning further correlated with chromosomal contraction (Skok et al. 2007).

Gene relocalization has also been observed during mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell differentiation in vitro. For example, the monoallelically expressed GFAP gene shows differentiation- and activity-dependent repositioning during astrocyte differentiation (Takizawa et al. 2008), as does the MASH1 locus during neural induction in ES cells (Williams et al. 2006). Thus, there are several documented cases in which the repositioning of a gene occurs at a specific stage of hematopoietic differentiation or during ES cell differentiation in vitro. These studies focused on the relationship of activated genes with their chromosomal territory, with another coordinately regulated gene, or relative to centromeric heterochromatin (for review, see Fraser and Bickmore 2007). However, repositioning was not always observed upon gene activation (Hewitt et al. 2004), and it remained unclear why some genes shift position upon activation while others do not.

The question of how genes are positioned within the nucleus is particularly relevant in the context of organismal development. Is nuclear reorganization essential for differentiated gene expression? Is transcription a prerequisite for relocalization (Ragoczy et al. 2006)? Is it sufficient? Does relocalization depend on the type of promoter, or only on transcriptional activity? And finally, are there different degrees of organization in pluripotent versus terminally differentiated cells? To examine these questions, we established a system for the live imaging of genes and promoters in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Worms provide a simple but powerful model for the study of differentiation, because each of the 959 somatic cells can be tracked from embryonic stages through larval and adult development due to invariant patterns of cell commitment (Sulston and Horvitz 1977).

Here we use live imaging of stably integrated reporter constructs and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) of endogenous loci to analyze the position of chromatin elements during C. elegans development. To study the promoter dependence of locus positioning, lacO sites were integrated adjacent to promoter-containing transgenes to enable their visualization through a GFP-LacI fusion (for review, see Belmont 2001). In mammalian cultured cells, the integration of lacO sites in large transgenic arrays allowed one to monitor the events coupled with trans-activator binding, chromatin remodeling, and later steps in gene activation, such as chromatin decondensation, mRNA processing, and mRNA export (Tumbar et al. 1999; Muller et al. 2001; Janicki et al. 2004; Voss et al. 2006). Directed movement of an active promoter was tracked previously for a VP16-induced array, although, in most instances studied, chromatin dynamics conform to a model of “constrained diffusion” (Gasser 2002; Chuang et al. 2006). Here, a similar tagging method allows us to track the position of both small integrated transgenes and larger heterochromatic arrays in developing worms. We monitored the radial positioning of developmentally regulated promoters as they become induced or repressed during normal differentiation in tissues of three germ layers.

Due to the polymer nature of the chromosomal fiber, the spatial position and dynamics of a genomic locus are inevitably influenced by neighboring sequences (Tajbakhsh et al. 2000; Mahy et al. 2002; Gartenberg et al. 2004). To avoid this problem, small transgenes bearing lacO-binding sites and developmentally regulated promoters allowing coincident analysis of expression and promoter position were integrated randomly into the worm genome. We identified the parameters responsible for changes in radial positioning during differentiation-driven gene activation, and confirmed the relevance of our live imaging results by whole-mount FISH for genomic loci. To see if tissue-specific induction of promoters can overcome the perinuclear sequestration of repeat-induced heterochromatin, we also created larger arrays of the same promoters. In all three systems—large arrays, smaller transgenes, and FISH—we find that tissue-specific developmentally regulated promoters are located at the nuclear periphery when the promoters are silent. When activated, however, they shifted to an internal nuclear position that was maintained in a tissue-specific manner into adulthood. The shift did not require mitotic division, and was not a consequence of transcriptional activity alone, since ubiquitously expressed promoters did not shift arrays from the nuclear periphery.

We conclude that developmentally controlled promoters can drive cell type-specific nuclear organization in worms: They bind the nuclear periphery in tissues in which they are silent, and are selectively shifted to nuclear lumen in differentiated cells. We find that early embryonic nuclei have less spatial organization, since silent tissue-specific promoters have no preferential distribution. Large heterochromatic arrays can nonetheless be sequestered at the nuclear periphery in embryos. We conclude that nuclear organization in worms is tissue-specific and developmentally regulated. In differentiated cells, developmentally regulated promoters determine position in a dominant manner, overriding other promoters and repeat-induced heterochromatin.

Results

Creation of lacO-tagged transgenic strains by bombardment

We exploited the well-characterized lacO/GFP-LacI system to score for perinuclear transgene position in living worms (Robinett et al. 1996; Carmi et al. 1998; Kaltenbach et al. 2000; Gonzalez-Serricchio and Sternberg 2006). To create transgenic strains with tagged chromatin in vivo, we used ballistic transformation, in which worms are bombarded with DNA-coated gold beads (Praitis et al. 2001). Rare integration events result in the stable propagation of the exogenous DNA, with anywhere from one to 50 copies of the plasmid at one integration site (see Supplemental Fig. 1A). Transformants were backcrossed to eliminate second site events, and we selected for small, integrated transgenes that were stable through meiotic and mitotic division.

We generated transgenes bearing tissue-specific, developmentally regulated promoters driving fluorescent reporters (myo-3∷mCherry for muscle; pha-4∷mCherry∷his-24 for gut) (Fig. 1A, Murray et al. 2008). Promoter sizes were small (2.5–4.1 kb, respectively), but were shown previously to support tissue-specific expression in living worms (Murray et al. 2008). Cointegrated are lacO sites and the transformation marker unc-119+, which is expressed in most neurons (Maduro and Pilgrim 1995). We also created a line bearing a lacO-tagged unc-119+ marker alone, to score the effect of this neuronal-expressed promoter. By quantitative real-time PCR of the plasmid-borne bla gene, we estimate the total number of integrated plasmid backbones in the strains used here to range from 10 to 54 copies per haploid complement (Supplemental Figs. 1A, 2B, GW304). Genetic cosegregation argues that each strain analyzed has a single locus of integration; consistently, FISH with differentially labeled probes for the bla gene and the tissue-specific promoter tag one overlapping locus (data not shown). Appropriate tissue-specific expression of these transgenes was confirmed by complementation of the unc phenotype by unc-119, and by the muscle-specific and gut-specific expression of myo-3∷mCherry and pha-4∷mCherry∷his-24, respectively (see Supplemental Fig. 1B,C; Murray et al. 2008).

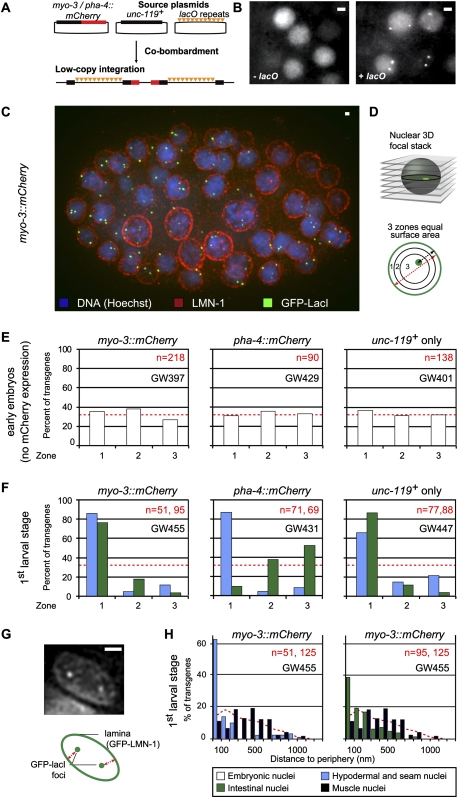

Figure 1.

Developmentally regulated promoters are positioned randomly in undifferentiated embryonic nuclei and relocate upon differentiation depending on expression status. (A) Outline of the plasmids used to create small bombarded transgenes. mCherry is driven by developmentally regulated promoters. An array of 256 lacO sites was cobombarded with the unc-119+ marker. (B) GFP signal in embryonic cells from a strain expressing GFP-LacI without (−lacO; strain GW395) or with bombarded transgenes containing lacO arrays (+lacO; strain GW397); see A. Bar, 2 μm. (C) Partial 3D reconstitution of a 120-cell-stage embryo (strain GW397) carrying a lacO-tagged transgene gwIs28[myo-3∷mCherry; 256xlacO; unc-119+] and expressing GFP-LacI. The embryo is stained for GFP (anti-GFP, green), the nuclear lamina (anti-LMN-1, red), and DNA (Hoechst, blue). Bar, 1 μm. (D) Quantification of radial positioning of GFP-LacI-tagged transgenes. Through-focus stacks of images are acquired at 200-nm intervals. In the plane where the GFP-LacI focus is brightest, the nuclear cross-section is divided in three concentric zones of equal surface area. The ratio of the distance from the spot to the periphery (black line) and the nuclear radius (red line/2) is determined for each spot. Random localization would lead to 33% in each zone. (E) Quantification of small transgene position in early-stage embryos before mCherry is detectable using the method described in D. The strains used are myo-3∷mCherry (strain GW397), pha-4∷mCherry (strain GW429), and unc-119+ only (strain GW401). n = number of foci counted. χ2 versus random: P = 0.1 (GW397), P = 0.9 (GW429), and P = 0.66 (GW401). (F) As E, except for nuclei in L1 larvae of the indicated cell types (intestinal cells: green bars; hypodermal and seam cells: blue bars), all of which have spherical nuclei. The strains used are myo-3∷mCherry (strain GW455), pha-4∷mCherry (strain GW431), and unc-119+ only (strain GW447). These three strains carry the same small transgenes as GW397, GW429, and GW401 scored in E, respectively, but also express a GFP-LMN-1 fusion from another transgene to identify the nuclear periphery. Cells were identified by their position and/or mCherry expression; hypoderm and seam cell results were combined. χ2 versus random: P < 10−4 in all tissues and all strains. χ2 between intestinal and hypodermal distributions: P < 2 × 10−16). (G) To quantify position in ellipsoid nuclei, the shortest radial distance between the GFP-LacI focus and the NE identified by GFP-LMN-1 is measured in the plane of focus. Bar, 2 μm. (H) Quantification of the small transgene array (myo-3∷mCherry) in L1 larvae muscle (black bars), hypoderm and seam cells (combined, blue bars), and intestinal cells (green bars) in strain GW455, using the method described in G. Muscle cells are identified by mCherry expression. Random distribution of distances obtained from a simulation using similar nuclear shapes is shown as a red dotted line (Kolgomorov-Smirnov vs. random: P < 0.002; between muscle and hypoderm: P < 10−11; between muscle and intestine: P < 10−9).

Visualization of a lacO-containing promoter-bearing transgene required the ubiquitous expression of a GFP-LacI fusion at low levels, which was achieved by placing it downstream from the baf-1 promoter. In the absence of lacO target sites, GFP-LacI gives a homogeneous nuclear fluorescence, first visible around the 20-cell embryo stage (Fig. 1B, −lacO). In strains carrying both the gfp-lacI and a lacO-tagged transgene, we detected two small GFP foci in every cell, reflecting a single site of lacO insertion on each chromosomal homolog (Fig. 1B, +lacO).

Transgene position reflects the transcriptional status of developmentally regulated genes

In order to assess whether bombardment-derived transgenes have a characteristic subnuclear localization, we quantified lacO-tagged array position relative to the nuclear envelope (NE). Embryos were stained by immunofluorescence for nuclear lamin (LMN-1) and GFP, and stacks of images were acquired (Fig. 1C). For each nucleus, the optical section with strongest GFP signal was divided into three concentric zones of equal surface, and lacO focus position was determined relative to these zones (Fig. 1D; Hediger et al. 2004). A randomly distributed locus yields 33% in each zone (Fig. 1D). This is a robust method for determining position within spherical nuclei, such as those in worm embryos and yeast (Meister et al. 2010).

We scored localization of the lacO-tagged transgenes bearing different tissue-specific promoters (unc-119, myo-3∷mCherry, and pha-4∷mCherry) in early-stage embryos, where all three promoters are either transcriptionally silent (no mCherry detectable) or known to be expressed in a very low number of cells (unc-119) (Maduro and Pilgrim 1995). In all cases, the integrated transgenes showed a random distribution with respect to the NE of the undifferentiated embryonic nuclei (Fig. 1E; Supplemental Fig. 2).

We next investigated transgene position in four distinct differentiated cell types of the first (L1) larval stage. Subnuclear position was determined relative to the nuclear lamina of muscle, gut, hypodermal, and seam cells. Intestinal, hypodermal, and seam cell nuclei are roughly spherical, and therefore amenable to the three-zone method described above. In contrast to the random distribution scored in embryos, the myo-3∷mCherry transgene was significantly enriched at the NE in all three cell types (hypodermal and seam cell results are pooled, as they derive from a common ectodermal lineage) (Fig. 1F).

Since muscle cell nuclei become elongated and flattened in larvae, an alternative mode of measurement was required. Instead of three-zone measurements, we scored the shortest distance from the nuclear periphery (GFP-lamin) to the center of the GFP-LacI signal in 95 nuclei of various L1 larvae (Fig. 1G). We compared this mode of measurement with a three-dimensional (3D) interpolation method, in which measurements were also made in a plane above and below the plane of focus. Because resolution is poor along the Z-axis, we eliminated spots that fell within 0.4 μm of the nuclear top or bottom. Simulations using these parameters on ellipsoid structures resembling the muscle nucleus yielded a variation of <8% between two-dimensional (2D) and 3D measurements (Supplemental Fig. 3).

In the muscle cells of L1 larvae, where the myo-3 promoter is active, we found the lacO-tagged myo-3∷mCherry transgene strongly enriched in the nuclear center, with a peak at 500–600 nm from the NE (Fig. 1H, muscle nuclei). We rescored intestinal, hypodermal, and seam cells with this distance-from-periphery method, and found that, respectively, 60% and 80% of the myo-3 transgenes were <200 nm from the nuclear lamina, a position correlated with repression of the myo-3∷mCherry construct (Fig. 1H, hypodermal/seam cell and intestinal nuclei). We conclude that, in larval differentiated tissues, a transgene bearing 2.5 kb of the myo-3 promoter assumes a position that reflects its transcriptional activity: The silent promoter was closely associated with the NE, while in muscle cells where myo-3 was active, the transgene shifted to the nuclear core.

We similarly monitored the position in L1 larval-stage worms of the tagged transgene bearing a truncated pha-4 promoter driving mCherry∷his-24 fusion, which is selectively active in intestinal cells (Murray et al. 2008). Again, in gut cells, the tagged construct shifted to an internal location (Fig. 1F, pha-4∷mCherry, intestinal nuclei), while in both hypodermal and seam cells, in which the pha-4 promoter was repressed, the transgene accumulated at the NE (Fig. 1F, pha-4∷mCherry, hypodermal and seam nuclei).

Since all of our constructs also carry the unc-119+ bombardment marker, it was necessary to rule out that this neuron-specific gene somehow determines transgene position. We found that transgenes bearing the lacO-tagged unc-119+ alone were systematically found in the outermost zone of intestine, hypodermal, or seam cell nuclei, in which the gene is silent (Fig. 1F, unc-119+ only; Maduro and Pilgrim 1995). Thus, we conclude that the internal shift of the myo-3 and pha-4 promoters in muscle and intestinal cells, respectively, must be due to the activation of tissue-specific promoters. Since the neuronal-specific unc-119+ gene is integrated alongside the myo-3 or pha-4 promoters, it appears that, when induced, these tissue-specific promoters override the perinuclear position of the silent tissue-specific gene unc-119+. This suggests that internal positioning does not occur passively; e.g., due to loss of a perinuclear anchor.

It is unlikely that the results obtained with this set of pha-4 or myo-3 promoter-containing transgenes could be due to flanking sequences at their sites of insertion, since it would mean that each integration landed in a zone that behaves in a tissue-specific manner, typical for the promoter integrated at that site. Nonetheless, to examine whether flanking sequences can override the behavior described above, we carried out the same analysis with two independently derived strains that bear the same myo-3 and pha-4 promoter-containing transgene constructs. The results were very similar to those in Figure 1 (Supplemental Fig. 2), again suggesting that the conserved shift that we document for active tissue-specific promoters in differentiated tissues does not reflect the transgene context, but the promoter itself.

Together, these results allow us to generalize based on three different tissue-specific constructs in three tissues of distinct lineage: muscle, gut, and ectodermal hypoderm. Tissue-specific promoter transgenes were distributed randomly throughout the nucleoplasm in early embryos, while, by the time the relevant tissues had been formed in L1 larvae, gene position correlated with the transcriptional status of the promoter. Tissue-specific expression was dominant over silent promoters, causing those to shift inward, while inactive transgenes accumulated at the nuclear periphery. Importantly, neither shift in position required the appropriate tissue-specific coding sequence or 3′ untranslated region (UTR), but was triggered by the promoters, which ranged in size from 2.5 to 4.1 kb.

Creation of large gene arrays tagged by GFP-LacI

In many species, heterochromatin is found at the NE, although it is excluded from nuclear pores (for review, see Akhtar and Gasser 2007). Thus, the perinuclear positioning of inactive tissue-specific transgenes in worms could reflect either the heterochromatic state of the silenced promoter or their active recruitment to pores. To monitor the behavior of worm heterochromatin, we sought to generate arrays that form heterochromatin in early embryos. It has been described previously that larger gene arrays created by gonad injection become transcriptionally repressed by various mechanisms, including HP1-mediated heterochromatization (Hsieh and Fire 2000; Bessler et al. 2010). Thus, we injected a myo-3:rfp reporter on a plasmid backbone, which forms a megabase-sized concatemer that can be integrated by X-ray irradiation. Transformants were screened for a stable, single-site integration. They were backcrossed extensively to allow us to monitor a megabase stretch of chromosome-borne heterochromatin (Fig. 2A).

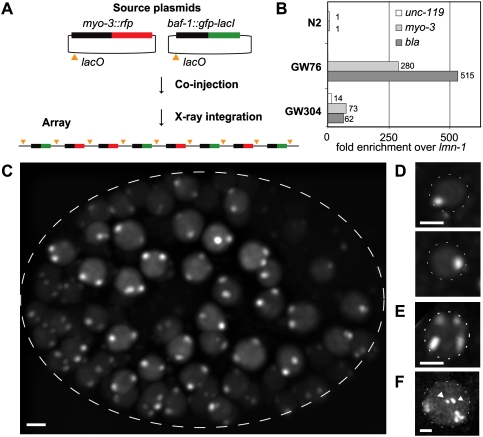

Figure 2.

Integrated plasmids in the worm genome can be detected by GFP-LacI. (A) Outline of the plasmids used to create the integrated [baf-1∷gfp-lacI; myo-3∷rfp] array. The baf-1 promoter drives GFP-LacI expression in all cells. The cytoplasmic RFP marker under the control of the myo-3 promoter is specifically active in muscle cells. (B) Quantification by qPCR of copy number for plasmids present in the arrays shown in Figures 1C and 2C. Numbers are normalized to the endogenous single-copy gene (lmn-1). AmpR = bla. (C) GFP signal in an embryo homozygous for an integrated [baf-1∷gfp-lacI; myo-3∷rfp] array (strain GW76). In each nucleus, two spots can be observed. Bar, 2 μm. (D) GFP signal in two nuclei from an embryo heterozygous for the [baf-1∷gfp-lacI; myo-3∷rfp] array (F1 from strain GW76 crossed to wild-type N2). Bar, 2 μm. (E) GFP signal in one nucleus from an embryo homozygous for two arrays: the [baf-1∷gfp-lacI; myo-3∷rfp] array and an unrelated array, pxIs6[pha-4∷gfp∷h2b] (strain GW81). Bar, 2 μm. (F) GFP signal in a nucleus from a strain GW318 carrying both a large array (gwIs4[baf-1∷gfp-lacI; myo-3∷rfp]) and a small transgene (gwIs28[myo-3∷mCherry; 256xlacO; unc-119+]). Arrowheads indicate small transgenic arrays. Bar, 2 μm.

To visualize the large integrated array, a baf-1∷gfp-lacI plasmid was coinjected with the myo-3:rfp plasmid. Each cointegrated plasmid of the concatemer had a single lacO site, allowing the array-expressed GFP-LacI protein to fluorescently tag its own locus. Indeed, we observed two bright foci of GFP fluorescence in each nucleus of the transformed organism, from the 20-cell-stage embryo to the adult worm (Fig. 2C, GW76). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) for the ampicillin resistance gene (bla) and the myo-3 promoter showed the presence of ∼280 copies of the myo-3 marker and, as expected, of ∼515 plasmid backbones, since both baf-1∷gfp-lacI and myo-3∷rfp plasmids carry bla (values were normalized to the single-copy worm locus lmn-1) (Fig. 2B). In agreement with their higher plasmid copy number, these large arrays occupy a bigger volume in the nucleus than the above-described low-copy integrants (Fig. 2F).

To prove that the focus truly represents the GFP-LacI binding to the integrated array, we generated a strain that was heterozygous for the large inserted array by crossing to a nontransgenic strain. All cells in the resulting offspring now had one focus per nucleus (Fig. 2D), while, after crossing to another transgenic line that carries a second integrated array, all offspring had four spots per nucleus (Fig. 2E). Thus, our system is genetically robust and allows us to monitor the subnuclear position of large integrated gene arrays bearing tissue-specific promoters.

Large arrays serve as a model of heterochromatin

To examine the chromatin status of these large integrated gene arrays, we immunostained embryos for characteristic heterochromatin modifications; namely, histone H3K9 and H3K27 trimethylation (H3K9/27me3). In embryos carrying large arrays, H3K9me3 colocalized precisely with the GFP-LacI signal (Fig. 3A). In the absence of the array, H3K9me3 was present at low levels in the embryo in an uneven, punctate distribution, with no particular enrichment at the NE (data not shown). The H3K27me3 mark is bound and deposited by Polycomb Repressor Complexes 1 and 2 in flies and mammals (for review, see Schuettengruber et al. 2007), and generally coincides with repressed promoters in differentiated tissues. However, H3K27me3 is also present at uncommitted promoters in pluripotent mouse ES cells (for review, see Boyer et al. 2006). Consistently, in the transgenic worm embryos, large integrated arrays showed a strong enrichment of H3K27 tri- and dimethylation marks (Fig. 3B; data not shown), although its staining was less restricted than that of H3K9me3 (Fig. 3A). Finally, we note that the chromatin modification typical for active promoters (H3K4me3) was excluded from the large arrays (Fig. 3C). Large arrays are therefore reminiscent of repetitive heterochromatin, being enriched for repressive histone methylation marks. Nonetheless, we know that some of the array-borne baf-1 promoters are active, as we detect baf-1-driven GFP-LacI in every cell. It appears that large “heterochromatin-like” arrays at the NE are permissive for at least low-level transcription from ubiquitously expressed promoters.

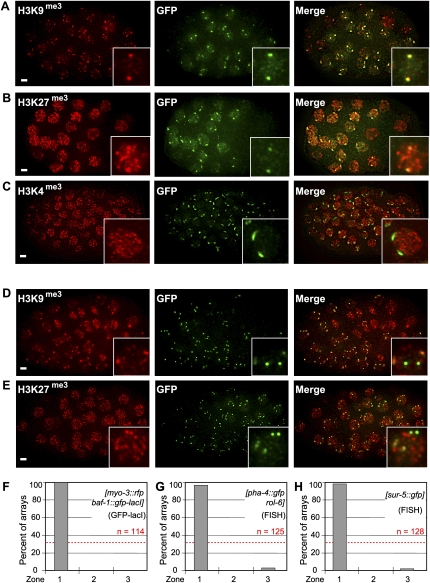

Figure 3.

Large arrays carrying silent chromatin modifications are at the nuclear periphery. (A) Immunostaining of H3K9me3 and GFP, and their colocalization in embryos of the strain GW76 carrying the [baf-1∷gfp-lacI; myo-3∷rfp] array. A projection of multiple planes of a deconvolved Deltavision wide-field image is shown. Bar, 3 μm. (B) As A, for H3K27me3 and GFP, with colocalization in GW76 embryos. Bar, 3 μm. (C) As A, for H3K4me3 and GFP in GW76 embryos. Bar, 3 μm. (D) As A, for H3K9me3 and GFP, in embryos of GW318, which bears both a large array that expresses GFP-LacI ([baf-1∷gfp-lacI; myo-3∷rfp]) and a small bombarded transgene expressing mCherry under transcriptional control of the myo-3 promoter. The large arrays, but not the brighter small transgenes, colocalize with H3K9me3 staining. Bar, 3 μm. (E) As D, for H3K27me3 and GFP, in embryos of GW318. Bar, 3 μm. (F) Quantification of the subnuclear position in embryonic nuclei of the [baf-1∷gfp-lacI; myo-3∷rfp] array from strain GW76 using the three-zone method (Fig. 1D). (G) As F, for an unrelated pxIs6[pha-4∷gfp∷h2b] array in early embryos of strain SM469. (H) As F, for localization of highly active constitutively expressed promoter [sur-5∷gfp] in a large integrated array (strain GW427) in embryos probed by FISH.

We also monitored histone modifications on the smaller bombarded transgenes whose positions were scored in Figure 1. In this case, neither the H3K9me3 nor the H3K27me3 mark coincided with the GFP signal that represents the small integrated transgene (Fig. 3D,E). Similar results were obtained with small transgenes bearing the pha-4 promoter (see below). Thus, in embryonic nuclei, large arrays, but not small transgenes, bear the characteristic histone marks of repressed heterochromatin.

Large heterochromatic arrays are associated with the NE in embryos

Careful observation of the large [myo-3∷rfp baf-1∷gfp-lacI] arrays in embryonic nuclei suggested a perinuclear localization (Fig. 2C). Quantitative scoring of the position of the large [myo-3∷rfp baf-1∷gfp-lacI] array in embryonic nuclei confirmed that the integrated array is indeed highly enriched at the NE in embryos (Fig. 3F). We also investigated a similar large array containing [pha-4∷gfp∷h2b; rol-6] but without the second plasmid expressing GFP-LacI. This integrated array showed a similar perinuclear localization in embryos when scored by FISH (Fig. 3G), allowing us to conclude that it is not the presence of the LacI–lacO interaction that causes peripheral association. To confirm that high-level housekeeping gene expression was compatible with peripheral positioning, we monitored a third array that expresses GFP from the strong constitutively expressed promoter of acetyl-CoA synthetase [sur-5∷gfp] (Kim et al. 2005). This constitutively expressed large array was also sequestered efficiently at the NE (zone 1), like the arrays bearing silent tissue-specific promoters (Fig. 3F–H). This is in contrast to the random localization scored in embryos for the bombardment-derived transgene carrying the same myo-3 or pha-4 promoter (Fig. 1E). We conclude that the large integrated arrays assume a heterochromatic state that coincides with perinuclear attachment. A strong constitutively expressed promoter like sur-5 was unable to overcome NE attachment; thus, transcription, per se, does not promote or require internal localization in embryos.

Differentiation-induced promoters overcome array anchoring

Given our observation that tissue-specific promoter activation correlated with accumulation of small transgene arrays in the nuclear lumen (Fig. 1F,H), it was logical to ask whether tissue-specific induction of the myo-3 promoter in the context of this large heterochromatic array could override its sequestration at the NE. To examine this, we quantified the radial position of the array in RFP-positive muscle cells and in a variety of nonmuscle tissues (pharynx, seam cells, hypoderm, and nerve) from the same animals (Fig. 4A).

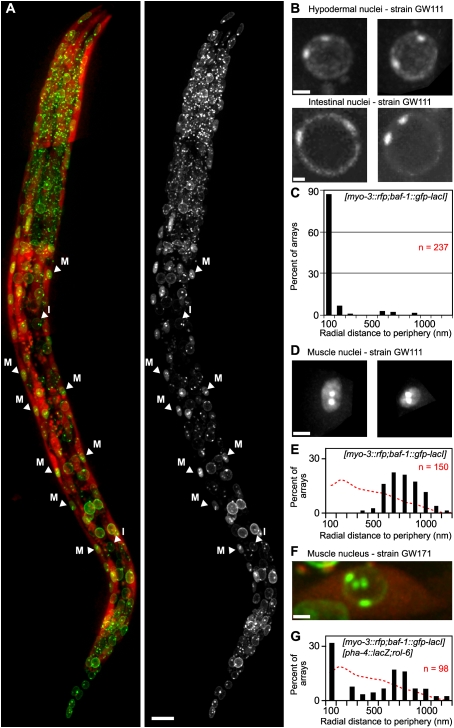

Figure 4.

Relocation of differentiation-induced arrays to the nuclear interior. (A) An L1-stage larva of strain GW111 carrying the [baf-1∷gfp-lacI; myo-3∷rfp] array and expressing GFP-LMN-1 to highlight the nuclear periphery. The four lines of muscle nuclei can be observed due to RFP expression (labeled M), while internal intestine nuclei are labeled I. Bar, 10 μm. (B) GFP signal in two examples of hypodermal nuclei (top) and intestinal nuclei (bottom) from the L1 larva of strain GW111 shown in A. Bar, 2 μm. (C) Quantification of the radial distance (in nanometers) of the [baf-1∷gfp-lacI; myo-3∷rfp] array to the periphery in nonmuscle cells in strain GW111, as in Figure 1G. (D) GFP signal in two examples of muscle nuclei from the L1 larva of strain GW111 shown in A. Bar, 2 μm. (E) Quantification of the radial distance (in nanometers) of the [baf-1∷gfp-lacI; myo-3∷rfp] array to the periphery in muscle cells in strain GW111, calculated on the focal plane as described in Figure 1G. Random distribution in similarly shaped nuclei is shown as a red dotted line. Kolgomorov-Smirnov versus random distributions: P < 10−15. (F) GFP and RFP signal in a muscle nucleus from an L1 larva of strain GW171 carrying both an active array ([baf-1∷gfp-lacI; myo-3∷rfp]) and an inactive array {caIs[pha-4∷lacZ rol-6(su1006)]}. Bar, 2 μm. (G) Quantification of the radial distance (in nanometers) of active array [baf-1∷gfp-lacI; myo-3∷rfp] and inactive array caIs[pha-4∷lacZ rol-6(su1006)] in muscle cells of the strain GW171, as described in Figure 1G. Random distribution in similarly shaped nuclei is shown as a red dotted line. Kolgomorov-Smirnov versus random distributions: P < 0.001.

Using the distance measurement techniques described above, we first measured the radial distance of the [myo-3∷rfp baf-1∷gfp-lacI] array from the NE in differentiated, nonmuscle nuclei; namely, those of hypodermal and intestinal cells. We found that the silent large array remains positioned <200 nm from the NE in >90% of nonmuscle cells (Fig. 4B,C). In contrast, in muscle where the myo-3 promoter is active, we detected a systematic shift to the nuclear core (Fig. 4D,E). The distances between the myo-3 array and NE in muscle were distributed around 600 nm, roughly the length of the semiminor axis of the ellipsoid nucleus (Fig. 4E). This distribution is clearly distinct from a random distribution, which was generated in silico Fig. 4E, red dotted line, Kolgomorov-Smirnov test: P < 0.01).

Intriguingly, the internal-shifted myo-3 arrays were brighter in muscle cells, apparently due to high levels of expression from the baf-1∷gfp-lacI construct, yet the array appeared quite compact. To ensure that this internal, compact array was being expressed, we scored for nascent mRNA by RT–PCR across the exon–intron junction of the RFP transgene. Nascent RNA was readily detected in synchronized 1-d-old L1 larvae (Supplemental Fig. 4A), arguing that the internally positioned, compacted array was indeed transcriptionally active in differentiated L1-stage muscle. We conclude that large myo-3 arrays (spanning >3.5 Mb) relocate from the NE in embryos to the nuclear lumen in muscle cells. The shift coincides with activation of the muscle-specific promoter, without need for a muscle-specific gene, since the myo-3 promoter drives RFP.

To monitor the position of a repressed tissue-specific promoter in muscle, we coupled the myo-3 array with a second integrated array carrying the pha-4 promoter, which is silent in muscle and selectively active in gut lineage cells of embryos, as well as larval and adult intestine ([pha-4∷lacZ rol-6(su1006)]) (Azzaria et al. 1996). In muscle cells carrying both myo-3 and pha-4 arrays, we scored two foci in the nuclear lumen and two at the nuclear periphery, each pair having a slightly different intensity (Fig. 4F). Quantification of distances to the periphery of all foci showed a bimodal distribution: Half were located <100 nm from the periphery, and half were between 0.5 and 1 μm from the NE (Fig. 4G). This distribution is statistically different from a random simulated distribution in nuclei with the same shape (Fig. 4G, red dotted line, P-values for Kolgomorov-Smirnov test are in legend), and is unlike myo-3∷rfp alone, which is exclusively internal. Thus, in a differentiated tissue, the inward shift of the myo-3 array does not occur for an intestine-specific promoter, and thus correlates with activity.

Transcriptional activation precedes array decondensation and repositioning

We then examined the [pha-4∷lacZ rol-6(su1006)] array in developing gut, to examine the kinetics of array decompaction. The decondensation of gene arrays due to targeted transcription factors has been monitored in mammalian cells carrying artificial constructs, which can be induced either by binding the VP16 transactivator or by the CMV promoter (Tumbar et al. 1999; Nye et al. 2002; Dietzel et al. 2004). Here, the size of our large heterochromatic arrays allowed us to examine whether endogenous levels of transcription factors induce a detectable decondensation of tandemly amplified tissue-specific promoters.

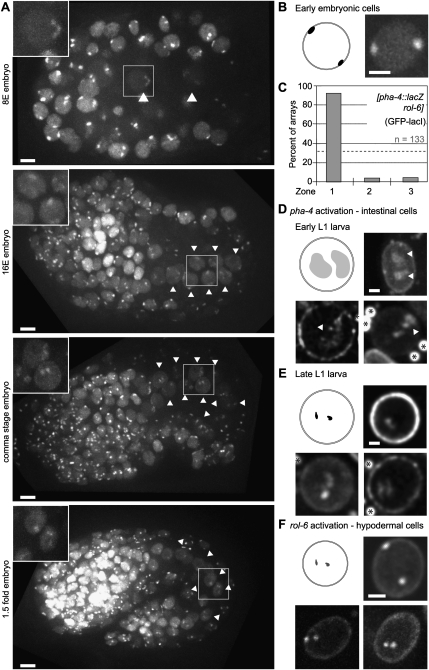

We first scored the position of the [pha-4∷lacZ rol-6(su1006)] array in early and late embryonic development. The pha-4 promoter on this array became active at the so-called 8E cell stage when intestinal precursor cells (E cells) (see Fig. 5A, arrowheads) are clearly visible (intestinal precursor cells) (see Fig. 5A, arrowheads; Azzaria et al. 1996). In early embryos and in non-E cells of the 8E embryos, we observed two foci, both of which were at the NE (Fig. 5B,C). In later embryos, no clear expansion of the arrays could be observed in the E cells until the 1.5-fold stage (Fig. 5A, bottom panel). At this point, embryos start moving, so the next stage that could be scored was the early L1 larvae, shortly after hatching. At this stage, the pha-4 promoter is strongly active, as confirmed by β-gal staining (Supplemental Fig. 5), and we could identify in these nuclei two large, internally located fluorescent structures (Fig. 5D). These internal, decondensed “clouds” of chromatin detected by GFP-LacI extended from the nuclear periphery and protruded into the nuclear lumen (Fig. 5D, arrows). Within a given worm, all gut cells presented similar fluorescence patterns, and in no worm could we observe peripheral foci. Intriguingly, in older L1 or L2 larvae, which we score by body size, the pha-4 arrays recompacted yet remained internal (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5.

Differentiation-induced relocation of large arrays is accompanied by decondensation and is observed in multiple tissues. (A) GFP signal in embryos during early development from strain GW583 carrying the caIs[pha-4∷lacZ rol-6(su1006)] array. (Arrowheads) Intestinal precursor cells (E lineage). Bar, 2 μm. (B) GFP signal in early embryonic cells from strain GW583. Bar, 2 μm. (C) Quantification of the subnuclear position of the caIs[pha-4∷lacZ rol-6(su1006)] array using the three-zone method (Fig. 1D) in embryonic nuclei from strain GW583. (D) GFP signal in intestine cell nuclei from GW583 early L1 larvae. The arrays, active in intestinal cells, are seen detached from the nuclear lamina (arrows). Bar, 2 μm. Autofluorescence from the gut is marked as stars. (E) GFP signal in intestine cell nuclei from late L1 larvae of strain GW583. Bar, 2 μm. Autofluorescence from the gut is marked as stars. (F) GFP signal in hypodermal cell nuclei from L1 larvae of strain GW583. Bar, 2 μm.

The truncated pha-4 promoter used here to transcribe lacZ is activated at the 8E cell stage (eight intestinal cells among ∼100 cells in total) (see Azzaria et al. 1996). The timing of transcription, decompaction, and relocation scored by live imaging of developmental stages argued for a clear order of events: Transcription appears to initiate first (in the 8E cells of 100-cell embryos), and chromatin then decondenses and persists partially unfolded at the earliest L1 larval stage. The relocalization of the activated array to the nuclear lumen occurs in this window. Finally, the chromatin of the array recompacts as the larval intestine matures, retaining LacZ expression (Supplemental Fig. 5).

rol-6 arrays shift inward in hypodermal cells

The pha-4∷lacZ gene array also carries the rol-6(su1006) gene under control of its endogenous promoter. Although the mechanism of its activation is poorly characterized, rol-6 is known to be expressed specifically in the epithelial hypoderm cells, and not in the neighboring seam cells (Sassi et al. 2005). Hypodermal cells are of ectoderm origin and can be identified by their position close to the cuticle of the worm (Sulston and Horvitz 1977). In strains carrying the [pha-4∷lacZ rol-6(su1006)] insertion, the array is seen as a compact pair of spots in hypodermal cells, but at least one and sometimes both foci were shifted away from the periphery of hypodermal nuclei (Fig. 5F). This may indicate that either only one copy of the array is activated for rol-6, or the repressed pha-4 promoter dominates and retains one copy of the array at the NE. Nonetheless, since the array is not peripheral as in muscle (Fig. 4F,G), we conclude that activation of the hypodermal-specific promoter also leads to relocalization away from the NE, as observed in muscle and gut.

To determine whether the rol-6 copies on the compact but internal arrays are actively expressed, we exploited the fact that the array-borne rol-6 allele contains the su1006 mutation, which differs by 1 nucleotide from the endogenous copy. This creates a restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) that can be monitored by appropriate primer-based PCR. Using selective amplification of the wild-type and mutated rol-6 RNAs, we show that the gene on the array is at least 100 times more highly transcribed in hypodermal cells than the genomic allele, suggesting that a large fraction of the gene copies on the array are expressed (Supplemental Fig. 4B). However, unlike the unfolding observed in E cells, we were unable to capture a transient decompaction of the array during early hypodermal differentiation.

Ectopic muscle differentiation can induce myo-3 array relocalization

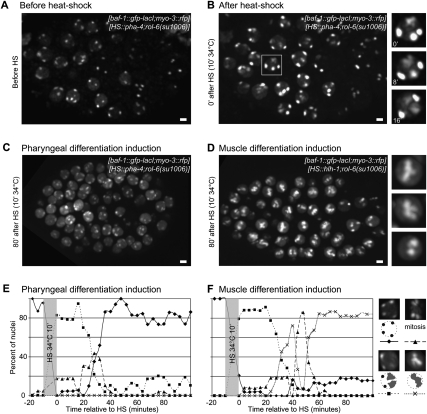

Does the relocation of an activated tissue-specific promoter depend on stage-specific nuclear “maturation,” or can it simply be driven by turning on the master regulator of the tissue-specific promoter? It has been shown previously that a heat-shock (HS)-induced expression of the C. elegans MyoD homolog HLH-1 in early embryos results in the induction of a muscle-specific transcriptional program and premature differentiation of muscle-like cells (Fukushige and Krause 2005). This pathway includes expression of the myo-3 promoter, which is a target of HLH-1 (Fukushige et al. 2006). We therefore asked whether the premature induction of muscle differentiation in embryos, by ectopic induction of hlh-1, would be sufficient to decondense and/or relocate the myo-3 array. As a control, we used ectopic expression of pha-4 driven by the same promoter as hlh-1, whose expression induces premature differentiation into another fate; i.e., pharyngeal cells (Kalb et al. 1998).

In strains homozygous for both the myo-3∷rfp array and either the hsp-16.2∷pha-4 or the hsp-16.2∷hlh-1 array, four compact spots are visible at the nuclear periphery before heat shock, as seen previously for all other integrated arrays (Fig. 6AE,F [diamonds]). When the embryos are observed after 10 min at 34°C, only two spots are still compact at the nuclear periphery, while the two others are either decondensed or become decondensed during the subsequent 20 min (Fig. 6B [0 min after HS and time lapse of boxed nucleus], E,F [squares in the scoring of nuclei]). HS-induced transcriptional activation and the subsequent decondensation resemble that of the pha-4 array in developing gut cells. HS-induced decondensation persisted for 30–40 min after embryos were returned to 23°C, but was systematically lost as nuclei underwent mitotic division (Fig. 6C,E [triangles and squares]).

Figure 6.

Ectopic expression of HLH-1 induces decondensation and relocation of myo-3 promoter arrays A and B. GFP signal in an embryo of strain GW110 containing two independent arrays: gwIs4[baf-1∷gfp-lacI;myo-3∷rfp] and cgc3595Is[hsp-16.2∷pha-4;rol-6(su1006)]. The embryo is shown before (A) and immediately after (B) 10 min of HS at 34°C. The boxed nucleus is shown as a time course after HS on the right side. Similar features are observed before and immediately after HS for strain GW105, containing arrays gwIs4[baf-1∷gfp-lacI;myo-3∷rfp] and gvIs[hsp-16.2∷hlh-1;rol-6(su1006)]. Bar, 2 μm. (C) Terminal differentiation state after ectopic induction of pharyngeal fate in strain GW110 (see above). Bar, 2 μm. (D) As C, after ectopic induction of muscle fate in GW105 (see above). Bar, 2 μm. (E) Scoring of nuclear localization and shape of arrays upon HS-induced pharyngeal differentiation in strain GW110. The key is shown to the right. (F) As E, after HS-induced muscle differentiation in strain GW105. The key is shown to the right. Note that the localization of the myo-3 array in the center is heritable through mitosis.

We then compared the position and appearance of the myo-3 array in embryos induced to differentiate into either pharynx or muscle (Fig. 6C–F). After induction of pharyngeal differentiation, myo-3 promoter arrays stay compact and peripheral, as does the hsp-16.2∷pha-4 array after embryos are returned to 23°C (Fig. 6C,E). This is reminiscent of the compacted status and peripheral position of the myo-3 array in pharyngeal cells (Fig. 4; Supplemental Fig. 5). Upon HLH-1 expression, we could no longer detect compact peripheral arrays in embryonic nuclei, and instead amorphous clouds of GFP-LacI-bound chromatin were detected in the nuclear lumen (Fig. 6D). This suggests that the heterochromatic, peripheral myo-3 arrays decondensed and moved inward shortly after HS. A kinetic analysis of pattern changes after HS confirmed that the relocation of the myo-3 array occurred after the expansion of the HS arrays, yet prior to passage through mitosis (Fig. 6F, crosses). By scoring HS array dynamics in the control strain in which pha-4 is under control of the same hsp-16.2 promoter, HS-induced decompaction could be shown to be finished by 40 min, which is precisely when myo-3 array expansion occurs following HLH-1 expression (Fig. 6F). Since HS alone does not have the same effect, our results argue that induction of a master regulator like HLH-1 is sufficient to provoke major nuclear reorganization and an internal shift of the myo-3 array, at a stage of development when the myo-3 promoter is normally silent and its array is peripheral. Indeed, HLH-1 activates the myo-3 promoter leading to transcription initiation and changes in chromatin structure (Fukushige et al. 2006).

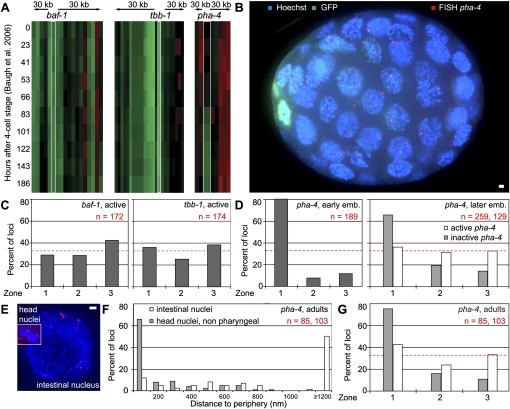

Small transgenes and large arrays mimic endogenous locus positioning

To evaluate whether our observations of arrays and transgenes are valid for endogenous loci, we performed FISH in whole C. elegans embryos. It should be noted that FISH probes encompass 15–30 kb, and that 30 kb of an endogenous 30-nm chromatin spans ∼250 nm. Therefore, “gene-specific” FISH also labels the flanking chromatin, making it difficult to discriminate what determines the spatial position of a locus. Taking this into account, we chose three regions in the genome with distinct average expression levels over a 30-kb segment (based on published whole-embryo expression data) (Baugh et al. 2005). The first two regions encompass baf-1 and tbb-1, both ubiquitously active housekeeping genes that are transcribed throughout early embryonic development, and both found in active regions of the genome (Fig. 7A, baf-1 and tbb-1 regions). The third region contains the developmentally regulated gene pha-4, which is silent in early embryos (20- to 50-cell stage) and activated in pharyngeal precursor cells (Fig. 7A, pha-4 region). Importantly, we note that the genes around the endogenous pha-4 locus are also largely silent in embryos (Baugh et al. 2005).

Figure 7.

Localization of endogenous genes by FISH relative to the NE. (A) Heat maps of the transcription of the genomic regions encompassing 60 kb around the baf-1, tbb-1, and pha-4 genes, respectively. (Green) High RNA levels; (red) no or very little RNA, based on Baugh et al. (2005). (B) Partial 3D projection of an immunofluorescence/FISH experiment in strain SM469 expressing gfp-h2b under transcriptional control of the pha-4 promoter from an array (pxIs6[pha-4∷gfp∷h2b]) with a probe recognizing the genomic pha-4 locus. (Green) Anti-GFP; (red) pha-4 FISH; (blue) DAPI. Bar, 1 μm. (C) Quantification of FISH signal position for the baf-1 and tbb-1 active housekeeping gene regions in 20- to 50-cell-stage wild-type embryos. Nuclear localization was scored as described in Figure 1D. (D) Quantification of FISH signal position for the pha-4 locus for early embryos (left panel, χ2 test vs. random: P < 10−16) and in later embryos (right panel) with active pha-4 promoter (pha-4, active), as judged by the presence of the GFP-H2B signal, or with silent pha-4 (pha-4, inactive, no GFP signal). GFP-H2B is under control of the full-length pha-4 promoter in an array in strain SM469. χ2 versus random: P = 0.6 (active pha-4), P < 10−16 (inactive pha-4). (E) Partial 3D projection of a FISH experiment in intestinal cells and head nuclei (to scale) in wild-type N2 adult worms with a probe recognizing the genomic pha-4 locus. Several spots are observed in intestinal cells, as this tissue is polyploid. (Red) pha-4 FISH; (blue) Hoechst. Bar, 1 μm. (F) Quantification of FISH signal in intestinal nuclei (white bars) and head nuclei excluding those inside the pharynx (gray bars) of wild-type adult worms, using the method described in Figure 1G. Kolgomorov-Smirnov between head and intestinal distributions: P < 10−16. (G) Same data as in F, quantified using the zoning method described in Figure 1D. χ2 versus random: P < 10−16 (head nuclei), P < 0.07 (intestine nuclei).

We performed FISH for baf-1 and tbb-1 regions in embryos, and quantified their positions relative to the NE (Fig. 7B). Both were distributed randomly, which agrees with the random distribution of small transgenes in early embryos (cf. Figs. 1E and 7C). When we scored for the endogenous pha-4 region in very early embryonic cells where it is inactive, the locus was enriched at the nuclear periphery (zone 1 in >80% of cells) (Fig. 7D). The pha-4 promoter-bearing transgene was not excluded from the NE in early embryos, but rather showed a random distribution (Fig. 1E). Thus, it is likely that the more peripheral position of the genomic region containing pha-4 reflects a chromosomal context rich in repressed genes.

Relocalization of the pha-4 locus in pharyngeal precursor cells

We could nonetheless examine by FISH whether the endogenous pha-4 domain changes position in response to developmentally induced expression. Genomic FISH is fairly efficient in embryos, allowing us to examine the position of the endogenous pha-4 gene in two states of activity in late embryos (Mango et al. 1994). To identify the cells that express pha-4, we made use of a strain expressing GFP-histone from the complete pha-4 promoter (Fig. 7B, green nuclei; Horner et al. 1998). In this strain, we performed FISH using a probe specific for the endogenous pha-4 locus that does not detect the transgenic pha-4 promoter driving gfp-h2b. Quantification of the radial distribution of the FISH signal showed that the locus was distributed randomly with respect to the NE in cells that expressed pha-4 (Fig. 7D, pha-4, later embryos, white bars). In embryonic cells in which pha-4 was inactive, the locus was significantly peripheral (64% in zone 1) (Fig. 7D, later embryos, gray bars).

To explore whether the activity-correlated localization of endogenous pha-4 was maintained throughout worm development, we performed FISH in dissected adult intestine and head. Figure 7E shows representative pictures of nuclei from these two tissues. We note that adult intestinal cells become polyploid, resulting in more than two signals per nucleus (Hedgecock and White 1985). As observed for differentiating embryos, in adult nonpharyngeal head cells in which pha-4 is inactive, this genome segment is highly enriched at the NE (Fig. 7E–G, head nuclei, nonpharyngeal). In contrast, in gut cell nuclei ,the pha-4 genomic region shifted to an internal site (>40% are >1200 nm from the NE) (Fig. 7F). These results are fully consistent with our conclusions based on developmentally regulated transgenes: The transgene behavior allows us to propose that developmentally regulated promoters themselves are sufficient to promote a shift to the nuclear interior upon gene activation. Tissue-specific inactivation of such a locus may also account for its peripheral sequestration, while the NE-association of a heterochromatic large array is a default state that can be overcome by activation of a tissue-specific promoter. We summarize our conclusions in Figure 8.

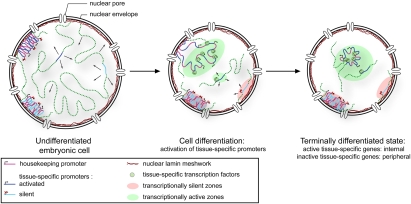

Figure 8.

Model summarizing gene positioning during differentiation Two major forces drive tissue-specific subnuclear organization of the worm genome: repeat-induced heterochromatin, which associates with the NE, and tissue-specific promoters that shift inward in a dominant fashion when they are activated. Tissue-specific promoters shift in a nondominant manner to the NE in cells in which they are inactive.

Discussion

We developed a system to analyze the subnuclear position of genes and genome segments during the development of C. elegans. We find that tissue-specific promoters are able to determine gene localization by shifting the relevant DNA to either an internal position when active or the nuclear periphery when silenced (Figs 1F,H, 4E). This phenomenon is confirmed for three different promoters in differentiated tissues derived from three different germ layers of the same organism. The subnuclear positions scored cannot simply reflect the site of transgene integration, since each construct behaves in a tissue-specific manner. In contrast, there is little detectable nuclear compartmentalization for small transgenic arrays in early embryos, although the embryonic NE has the potential to sequester an endogenous silent domain (pha-4) and artificial heterochromatic domains (large arrays). This latter phenomenon is array size-dependent and can be correlated with the deposition of histone marks typical for both constitutive and facultative heterochromatin (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3) (Figs. 2F, 3). Importantly, our study allows us to determine a hierarchy of subnuclear localization signals: Heterochromatic anchorage can be overcome by the activation of a developmentally regulated promoter, even though transcription, per se (e.g., of housekeeping promoters sur-5 and baf-1) (Fig. 3F,H), is not sufficient to trigger the release of a heterochromatic locus from the NE. This latter phenomenon is reminiscent of situations in both yeast and human cells, in which the artificial tethering of integrated sequences to the NE was found to reduce expression of only some promoters (Towbin et al. 2009) .

That subnuclear positioning can enhance both heritable repression and transcriptional induction of specific genes has been demonstrated most clearly in budding yeast (for review, see Spector 2003; Taddei et al. 2004; Akhtar and Gasser 2007). Yet to date it is unclear what renders a promoter sensitive or insensitive to modulation by subnuclear positioning. Here, by using small transgene arrays carrying developmentally regulated promoters and large heterochromatic arrays, we were able to identify some of the features that influence gene positioning during development. It is important to examine nuclear organization in the context of the whole organism, since genetic programming is not established by transcription factors alone, but in concert with cytoskeletal signals that stem from the tissue environment (Zhang et al. 2001; Mislow et al. 2002).

High gene copy number arrays as a model for heterochromatin–NE interaction

We show that integrated transgenic arrays accumulate repressive histone marks (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3) and become peripherally sequestered in a size-dependent manner. Up to 50 promoter copies do not become “heterochromatic,” while an integrated array of 500 copies does. Its association with the NE is consistent with data showing a peripheral enrichment of gene-poor and underacetylated genomic domains in cultured mammalian cells, flies, and yeast (O'Keefe et al. 1992; Akhtar and Gasser 2007), yet it does not answer the question of whether heterochromatin-linked modifications cause the anchorage. The dispersed distribution of H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 in early embryonic cells makes it unlikely that either modification alone is sufficient to mediate binding to the NE in embryonic cells. For the same reason, it is unlikely that the H3K9me3 ligand HPL-2 (one of two worm HP1 homologs) can mediate the interaction (F Palladino, P Meister, and SM Gasser, pers. comm.). Nonetheless, histone methylation events and the packaging of the sequence within large repetitive arrays distinguish large from small arrays.

Preliminary RNAi assays against single genes of the Suv3–9 SET domain family (SET-6/11/13/15/20/21/23) (Andersen and Horvitz 2007) did not abolish the peripheral sequestration of large arrays in C. elegans (BD Towbin, unpubl.), although H3K9me3 levels were reduced to 10% of wild-type levels in embryos lacking met-2, the SetDB1 methyltransferase homolog (Andersen and Horvitz 2007). The mutation of mes-2, an Ezh2 methyltransferase homolog that deposits H3K27me3, also had no effect on either array positioning in embryos or the degree of compaction of large arrays (Capowski et al. 1991; Supplemental Fig. 7). This result is in contrast to a previous study (Yuzyuk et al. 2009) that reported an effect on extrachromosomal DNA array structure. This discrepancy may be attributed to the nature of the arrays used in the two studies. Our integrated arrays are of low sequence complexity, containing only C. elegans promoters, genes encoding fluorescent proteins, and a small amount of plasmid, while the previous study diluted plasmids ∼1/10 with herring sperm DNA during injection. Moreover, we monitor mitotically stable integrated arrays, while Yuzyuk et al. (2009) examined extrachromosomal arrays.

We note that the failure to see release from the NE after down-regulation of a single methyltransferase does not argue that histone marks have no role in either the positioning or compaction of chromatin. Rather, it may indicate that redundant pathways are involved in array localization, consistent with the presence of multiple types of histone methylation on the transgenes we scored. If this were true, then double or even triple mutations in histone methyltransferases may be required to see changes in heterochromatin anchoring. Similarly, we tested single mutants defective for key enzymes of the RNAi machinery (rde-1, rde-3, and mut-7), and found that they had no obvious effect on large array localization or compaction (BD Towbin, unpubl.). This is somewhat surprising, since part of the RNAi machinery has been implicated in large transgene array silencing in the germline (Grishok et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2005). Again, this may simply reflect the redundancy of mechanisms that lead to a peripheral gene position.

Tissue-specific promoter relocation correlates with cell differentiation

A major insight arising from our study is that tissue-specific promoters are a major force in defining developmental stage-specific nuclear organization. They not only drive the internal positioning of developmentally regulated promoters, but override the peripheral tethering of large arrays (Figs. 3F, 4E). Housekeeping gene promoters are not able to do this. Taken at face value, this implies that factors bound to developmentally controlled promoters are able to mediate gene repositioning. Similar conclusions were based on a FISH study that followed the β-globin locus during fetal liver differentiation (Ragoczy et al. 2006). In this study, the initially peripheral silent locus moved toward the nuclear lumen upon activation in a manner dependent on its locus control region. The association of active RNA polymerase II (PolII) and evidence of active transcription were both observed prior to relocation, suggesting that transcription precedes and perhaps promotes the subnuclear repositioning. In our system as well, array expansion and the complete internal shift of pha-4 promoter arrays occurred significantly after the initiation of transcription (Fig. 5D; Azzaria et al. 1996).

Once cell type differentiation was completed in L1 larvae, large arrays bearing the activated developmentally regulated promoter remained internal and compact, whether in hypodermal, intestine, or muscle cells (Figs. 4D, 5D,F). We show that these compact but internalized arrays are still actively transcribed (Supplemental Figs. 4, 5). Moreover, the endogenous pha-4 locus was also shown to remain internal in adult gut cells (Fig. 7E–G). A compact yet active gene configuration was also reported for transcriptional induction by a targeted estrogen receptor (ER) (Nye et al. 2002). In this study, the tethering of ER to an array of genes could promote chromatin decondensation, while estradiol-mediated activation of the ER promoted a partial refolding of the array (Nye et al. 2002; Carpenter et al. 2004). Nye et al. (2002) interpret these results as showing a reduction of transcriptional activation. In view of our results, which document continued transcription of the compacted array, the refolding of an internalized array could reflect establishment of a stabilized active state. Whereas decondensation may reflect chromatin opening to allow increased transcription factor binding, a stabilized compact state of the locus may reflect a state of equilibration in which the promoter assumes a constitutively active conformation. Intriguingly, the mouse IgK locus also appeared to contract during programmed differentiation of T cells (Skok et al. 2007). Stable localization to the nuclear lumen may be equivalent to the organization of activated genes in “transcription factories” (Fraser and Bickmore 2007).

Unfulfilled potential for gene positioning in early embryonic nuclei

Intriguingly, there is little or no positioning of silent transgenes in early embryonic nuclei, while in differentiated tissues, the same constructs shift to the nuclear periphery when inactive. Nonetheless, large heterochromatic arrays show that the machinery necessary for perinuclear tethering is present in early embryos. An earlier report showed that there are distinct lamin-associated domains on chromosomes in early fly embryos (Pickersgill et al. 2006), and that lamin interaction at some of these sites is lost during differentiation. This study used DNA methylation by a lamin–DNA methylase fusion (Dam-ID), which scores both transient and stable DNA–lamin interactions, whereas quantitative imaging approaches monitor steady-state situations. Indeed, imaging data from the same tissue in flies did not completely agree with the Dam-ID results (Pickersgill et al. 2006). Thus, based on data published to date, it is unclear whether early embryos in other organisms also have reduced levels of nuclear organization.

Nonetheless, in worms, we clearly document a progressive establishment of gene positioning during cell-type commitment and differentiation. Analysis of small transgenes carrying the pha-4 promoter shows that, as early as the 100-cell stage (8E), there is specific enrichment of the transgene in the nuclear interior in cells within which the promoter is active, or at the periphery in cells where it is off, while, up to this point, the pha-4 transgene was distributed randomly. This transition has not been addressed in studies of fly or mammalian differentiation. For example, the FACS-sorted fetal liver cells used in the Ragoczy study (Ragoczy et al. 2006) had already gone through differentiation (being 90% erythroid) (Trimborn et al. 1999), and studies using ES cells showed perinuclear enrichment of the silent β-globin and IgH loci prior to induced differentiation.

Active gene positioning dominates over repressed gene sequestration

A key question on gene positioning is how flanking sequences influence the position of a given locus. This aspect renders the interpretation of FISH data, which generally probe large domains, rather complicated. Using a 0.55-Mb region, Zink et al. (2004) studied localization of three adjacent genes with different transcriptional status, and found that each gene behaved independently of the others with respect to positioning in a transcription-dependent manner. However, it was not asked whether active or inactive loci were dominant for positioning. Here we examined the effect of having two differentially expressed promoters adjacent within a transgene array. In differentiated tissues, we find that position is determined in a dominant fashion by the active promoter: The active tissue-specific promoter shifts the silent one away from the nuclear periphery (e.g., unc-119). Given that a small transgene containing only the unc-119 promoter is NE-associated in the differentiated cells where it is not expressed, we propose that peripheral sequestration is a default position for chromatin lacking activated promoters, but only once cell fate decisions have been made. This was also proposed for inactive erythroid-specific genes in precursor cells (for review, see Kosak and Groudine 2004a; Schneider and Grosschedl 2007).

Based on our results, we propose a model (Fig. 8) in which developmentally controlled promoters are first rendered accessible to the transcriptional machinery by a master regulator that opens the promoter for transcription. An ensuing high-level transcription leads to the unfolding of the chromatin domain, and, finally, depending on the constellation of factors bound to the promoter, an active tissue-specific gene may shift away from the periphery in the appropriate cell. The gene is then retained in the nuclear lumen, possibly by interaction with the transcriptional machinery or other intranuclear components. Importantly, this can be induced by ectopic induction of a master regulator like HLH-1, although transcription driven from a housekeeping promoter does not produce the same effect. Given that we see a similar shift of genes in all tissues, even though the master regulators for each differentiation event are unique, we propose that promoter-bound remodeling factors recruited to establish tissue-specific expression may drive cell type-specific nuclear organization.

Our system provides a powerful genetic model in which to study differentiation-regulated aspects of nuclear organization. It allows RNAi screens to be coupled with nonlethal mutations to dissect the machinery responsible for the establishment of nuclear organization driven by developmentally regulated genes.

Materials and methods

Molecular biology and transgenic strains

The GFP-LacI expression plasmid was created by fusing the gfp coding sequence from plasmid pPD117 (Fire vector library) to lacI under transcriptional control of the baf-1 promoter, followed by the let-858 terminator. qPCR to determine copy number was performed as described in the Supplemental Material.

Two types of large arrays were created for expression of the GFP-LacI construct. The first one has a vit-5∷gfp marker and does not contain any lacO-binding site. The second one has a myo-3∷rfp marker (2.5-kb promoter region) and a single lacO site on both plasmids used to create the array, which was integrated by X-ray irradiation. Following integration, the strains were backcrossed four to eight times to wild-type N2. Other transgenic strains contain gfp∷lmn-1 (Liu et al. 2000) as a low-copy integrant obtained by microparticle bombardment, and two classical integrated arrays; namely, a [pha-4∷lacZ; rol-6] array [a 9-kb fragment of the pha-4 promoter and a 4-kb fragment of rol-6(su1006), comprising 2 kb of promoter and 2 kb of coding sequence] (Azzaria et al. 1996) and a pha-4∷GFP∷h2b array (Horner et al. 1998).

For small bombarded transgenes, the unc-119(ed3) III strain (DP38) or its derivate expressing GFP-LacI was cobombarded with a lacO repeat construct (pSR1) (Rohner et al. 2008), the unc-119 rescuing construct, and plasmids driving expression of mCherry from either a myo-3 (2.5-kb promoter region) or a small pha-4 promoter (Murray et al. 2008). Strains were backcrossed to unc-119(ed3)III parents following integration.

Microscopy

Live microscopy was carried out on 2% agarose pads supplemented with 0.1% azide when needed. For microscopy of embryos and worms, either a spinning disk confocal microscope (Visitron, Puchheim) (Figs. 2C–E, 4–6), a wide-field monochromator deconvolution microscope (TillVision,; Gräfelfing) (Figs. 1B, 2F), or a Deltavision wide-field deconvolution microscope (Deltavision, Applied Precision) (Figs. 1C–H, 3, 7) was used. For each picture, a stack with a z-spacing of 0.2 μm was taken. Stacks were aligned and merged using the software Qu (written in Matlab; available on request). 3D reconstructions used Imaris software (Bitplane). For quantitative analysis of arrays, transgenes, and locus position, measurements were made with ImageJ using PointPicker (http://bigwww.epfl.ch/thevenaz/pointpicker).

FISH

For large array FISH, an 800-base-pair (bp) fragment of bacterial bla was obtained by PCR. Probes were labeled using nick translation with Alexa-546-modified dUTP (Roche Nick translation kit using Invitrogen Alexa-546 dUTP). FISH was performed as follows: Embryos from bleached worms were fixed for 2 min in 2% paraformaldehyde (PAF) and spread on poly-L-lysine-coated slides. They were freeze-cracked on dry ice before a 2-min fixation in −20°C methanol. Following fixation, samples were rehydrated progressively in 2-min baths of 90%, 70%, 50%, and 25% ethanol. FISH was carried out in a Ventana slide processor using the standard protocol from the manufacturer. Briefly, DNA was denatured with HCl and heat before probe addition. Probe and samples were incubated for 1 h to overnight at 37°C before stringent washes in SSC buffers. Samples were DAPI-stained quickly prior to mounting in ProLong Gold anti-fade (Invitrogen).

For single-gene FISH, cosmids F38A6 (cut with NotI/KpnI), B0464, and W09D10 (Sanger Center) covering pha-4, baf-1, and tbb-1 genes, respectively, were labeled with Alexa-546 using the FISHTag kit (Invitrogen). Staining procedure was carried out as in Csankovszki et al. (2004) except that slides were post-fixed directly after freeze-cracking to preserve nuclear integrity. Image acquisition was carried out on a Deltavision RT wide-field microscope, and position scoring relative to nuclear periphery was done with ImageJ software.

Immunofluorescence staining

For FISH/immunofluorescence analysis of GFP expression, embryos were first immunostained with monoclonal anti-GFP (Roche) and Alexa-488 goat anti-mouse. Stained embryos were post-fixed for 10 min in 4% PAF before the FISH. For histone modification mark staining, embryos from bleached worms were freeze-cracked on dry ice, fixed in methanol for 30 sec, and post-fixed in 1% PAF for 2 min. For lamin/GFP staining, embryos were fixed for 5 min in 2% PAF before freeze-cracking, followed by post-fixation/dehydration in 70%/80%/95%/100% ethanol. For both, after three washes in PBS 0.25% Triton X-100 (PBS-T), slides were blocked in PBS 0.5% BSA before overnight incubation with primary antibody (anti-H3K9me3, H3K27me3 [gifts of T. Jenuwein]; anti-LMN-1 [gift of Y. Gruenbaum]; H3K4me3 [Upstate Biotechnologies 07-473]; anti-GFP [Roche 11814460001]) at 4°C. After three washes with PBS-T, samples were incubated for 30 min with secondary antibodies (Alexa-488 anti-mouse, Alexa546 anti-rabbit; Invitrogen) at room temperature before final washes and DNA staining with Hoechst 33258.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Gruenbaum for the baf-1 promoter, worm strains, and helpful discussions; T. Jenuwein for antibodies; and J.D. McGhee and the CGC for strains. We are grateful to M. Thomas for excellent technical assistance; the FMI C. elegans laboratories for guidance; and J. Alcedo, R. Ciosk, D. Schubeler, A. Peters, and R. Terranova for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the EU NOE “Epigenome,” the SNSF NCCR “Frontiers in Genetics,” the Novartis Research Foundation, and a fellowship from the Human Frontiers Science Program to B.L.P.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.559610.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

References

- Akhtar A, Gasser SM 2007. The nuclear envelope and transcriptional control. Nat Rev Genet 8: 507–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen EC, Horvitz HR 2007. Two C. elegans histone methyltransferases repress lin-3 EGF transcription to inhibit vulval development. Development 134: 2991–2999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzaria M, Goszczynski B, Chung MA, Kalb JM, McGhee JD 1996. A fork head/HNF-3 homolog expressed in the pharynx and intestine of the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Dev Biol 178: 289–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh LR, Hill AA, Claggett JM, Hill-Harfe K, Wen JC, Slonim DK, Brown EL, Hunter CP 2005. The homeodomain protein PAL-1 specifies a lineage-specific regulatory network in the C. elegans embryo. Development 132: 1843–1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmont AS 2001. Visualizing chromosome dynamics with GFP. Trends Cell Biol 11: 250–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessler JB, Andersen EC, Villeneuve AM 2010. Differential localization and independent acquisition of the H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 chromatin modifications in the Caenorhabditis elegans adult germ line. PLoS Genet 6: e1000830 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer LA, Mathur D, Jaenisch R 2006. Molecular control of pluripotency. Curr Opin Genet Dev 16: 455–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KE, Amoils S, Horn JM, Buckle VJ, Higgs DR, Merkenschlager M, Fisher AG 2001. Expression of α- and β-globin genes occurs within different nuclear domains in haemopoietic cells. Nat Cell Biol 3: 602–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capowski EE, Martin P, Garvin C, Strome S 1991. Identification of grandchildless loci whose products are required for normal germ-line development in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 129: 1061–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmi I, Kopczynski JB, Meyer BJ 1998. The nuclear hormone receptor SEX-1 is an X-chromosome signal that determines nematode sex. Nature 396: 168–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter AE, Ashouri A, Belmont AS 2004. Automated microscopy identifies estrogen receptor subdomains with large-scale chromatin structure unfolding activity. Cytometry A 58: 157–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang CH, Carpenter AE, Fuchsova B, Johnson T, de Lanerolle P, Belmont AS 2006. Long-range directional movement of an interphase chromosome site. Curr Biol 16: 825–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csankovszki G, McDonel P, Meyer BJ 2004. Recruitment and spreading of the C. elegans dosage compensation complex along X chromosomes. Science 303: 1182–1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzel S, Zolghadr K, Hepperger C, Belmont AS 2004. Differential large-scale chromatin compaction and intranuclear positioning of transcribed versus non-transcribed transgene arrays containing β-globin regulatory sequences. J Cell Sci 117: 4603–4614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser P, Bickmore W 2007. Nuclear organization of the genome and the potential for gene regulation. Nature 447: 413–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushige T, Krause M 2005. The myogenic potency of HLH-1 reveals wide-spread developmental plasticity in early C. elegans embryos. Development 132: 1795–1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushige T, Brodigan TM, Schriefer LA, Waterston RH, Krause M 2006. Defining the transcriptional redundancy of early bodywall muscle development in C. elegans: Evidence for a unified theory of animal muscle development. Genes & Dev 20: 3395–3406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartenberg MR, Neumann FR, Laroche T, Blaszczyk M, Gasser SM 2004. Sir-mediated repression can occur independently of chromosomal and subnuclear contexts. Cell 119: 955–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser SM 2002. Visualizing chromatin dynamics in interphase nuclei. Science 296: 1412–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Serricchio AS, Sternberg PW 2006. Visualization of C. elegans transgenic arrays by GFP. BMC Genet 7: 36 doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-7-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishok A, Sinskey JL, Sharp PA 2005. Transcriptional silencing of a transgene by RNAi in the soma of C. elegans. Genes & Dev 19: 683–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock EM, White JG 1985. Polyploid tissues in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol 107: 128–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hediger F, Taddei A, Neumann FR, Gasser SM 2004. Methods for visualizing chromatin dynamics in living yeast. Methods Enzymol 375: 345–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt SL, High FA, Reiner SL, Fisher AG, Merkenschlager M 2004. Nuclear repositioning marks the selective exclusion of lineage-inappropriate transcription factor loci during T helper cell differentiation. Eur J Immunol 34: 3604–3613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner MA, Quintin S, Domeier ME, Kimble J, Labouesse M, Mango SE 1998. pha-4, an HNF-3 homolog, specifies pharyngeal organ identity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes & Dev 12: 1947–1952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh J, Fire A 2000. Recognition and silencing of repeated DNA. Annu Rev Genet 34: 187–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicki SM, Tsukamoto T, Salghetti SE, Tansey WP, Sachidanandam R, Prasanth KV, Ried T, Shav-Tal Y, Bertrand E, Singer RH, et al. 2004. From silencing to gene expression: Real-time analysis in single cells. Cell 116: 683–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalb JM, Lau KK, Goszczynski B, Fukushige T, Moons D, Okkema PG, McGhee JD 1998. pha-4 is Ce-fkh-1, a fork head/HNF-3α,β,γ homolog that functions in organogenesis of the C. elegans pharynx. Development 125: 2171–2180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach L, Horner MA, Rothman JH, Mango SE 2000. The TBP-like factor CeTLF is required to activate RNA polymerase II transcription during C. elegans embryogenesis. Mol Cell 6: 705–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JK, Gabel HW, Kamath RS, Tewari M, Pasquinelli A, Rual JF, Kennedy S, Dybbs M, Bertin N, Kaplan JM, et al. 2005. Functional genomic analysis of RNA interference in C. elegans. Science 308: 1164–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosak ST, Groudine M 2004a. Form follows function: The genomic organization of cellular differentiation. Genes & Dev 18: 1371–1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosak ST, Groudine M 2004b. Gene order and dynamic domains. Science 306: 644–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosak ST, Skok JA, Medina KL, Riblet R, Le Beau MM, Fisher AG, Singh H 2002. Subnuclear compartmentalization of immunoglobulin loci during lymphocyte development. Science 296: 158–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Rolef Ben-Shahar T, Riemer D, Treinin M, Spann P, Weber K, Fire A, Gruenbaum Y 2000. Essential roles for Caenorhabditis elegans lamin gene in nuclear organization, cell cycle progression, and spatial organization of nuclear pore complexes. Mol Biol Cell 11: 3937–3947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maduro M, Pilgrim D 1995. Identification and cloning of unc-119, a gene expressed in the Caenorhabditis elegans nervous system. Genetics 141: 977–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahy NL, Perry PE, Bickmore WA 2002. Gene density and transcription influence the localization of chromatin outside of chromosome territories detectable by FISH. J Cell Biol 159: 753–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]